Abstract

Background

Comparisons of the technical acceptability of spirometry and impulse oscillometry (IOS) and clinical correlations of the measurements have not been well studied in young children. There are no large studies focused on African American and Hispanic children.

Objectives

We sought to (1) compare the acceptability of spirometry and IOS in 3–5 year old children and (2) examine the relationship of maternal smoking during pregnancy to later lung function.

Methods

Spirometry and IOS were attempted at 4 sites from the URECA birth cohort at ages 3, 4 and 5 years (472, 471 and 479 children respectively). We measured forced expiratory flow in 0.5 sec (FEV0.5) with spirometry and area of reactance (AX), resistance and reactance at 5 Hz (R5 and X5 respectively) using IOS.

Results

Children were more likely to achieve acceptable maneuvers with spirometry than with IOS at age 3 (60% vs 46%, p< 0.001) and 5 years (89% vs 84%, p=0.02). Performance was consistent among the 4 study sites. In children without recurrent wheeze, there were strong trends for higher FEV0.5 and lower R5 and AX over time. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with higher AXat ages 4 and 5 years (p<0.01 for both years). There was no significant difference in FEV0.5 between children with and without in utero exposure to smoking.

Conclusion

There is a higher rate of acceptable maneuvers with spirometry compared to IOS, but IOS may be a better indicator of peripheral airway function in preschool children.

Keywords: forced oscillation technique, pediatric pulmonary function testing, wheezing, epidemiology, African American, Hispanic

INTRODUCTION

Assessment of lung function is an essential component for understanding lung development and disease progression in early childhood and can serve as an outcome in clinical trials. Measurement of pulmonary function in preschool children is challenging. Spirometry is used in older children and adults and requires a maximal forced expiratory maneuver. Studies from single sites indicate that more than half of children between the ages of 3 and 5 years can perform spirometry successfully.8–13 The forced oscillation technique (FOT) has been used increasingly to assess respiratory mechanics. Impulse oscillometry (IOS) is a widely used application of FOT. IOS superimposes external pressure oscillations on the respiratory system during spontaneous breathing. One potential advantage of this technique is that it requires only tidal breathing and no forced expiratory maneuvers. Being less effort dependent, IOS may be more suitable for measuring lung function in younger children. IOS measures the impedance of the respiratory system (Zrs) which is not directly measured with spirometry. The components of Zrs are respiratory system resistance (Rrs) and reactance (Xrs). Rrs is the part of Zrs associated with frictional losses in the airways and lung parenchyma and Xrs is determined jointly by the elastic properties dominant at low oscillation frequencies and the inertive properties at higher oscillation frequencies. The majority of studies with IOS involve older children. There are fewer studies in children between 3 and 5 years of age.14–19 Most studies with spirometry and IOS have a limited number of subjects at the lower end of this age range and include predominantly non-Hispanic white children.

Direct comparisons of the rate of acceptable tests for spirometry and IOS in young children are lacking. We sought to compare the acceptability of the two procedures in a large sample of preschool children of predominantly African American and Hispanic heritage enrolled in the Urban Environmental and Childhood Asthma Study (URECA).1 The second aim of this study was to determine the ability of the two tests to detect abnormalities of lung function. The results of studies using IOS and spirometry in preschool children to detect abnormalities or changes in lung function have been inconsistent.2 Pulmonary function measurements are known to be decreased in infants of mothers who smoked during pregnancy as measured by thoracoabdominal compression techniques, passive respiratory system compliance and IOS.3–5 There has been no assessment of the effect of this exposure on pulmonary function in preschool children. Therefore, we examined the relationship of maternal smoking during pregnancy to lung function in the preschool years as assessed by spirometry and IOS.

METHODS

Study design

URECA is a longitudinal multicenter (Baltimore, Boston, New York, St. Louis) birth cohort designed to study the development of asthma and allergies in an inner-city population. Women in their third trimester were recruited between February 2005 and March 2007. Inclusion criteria included a child’s gestational age of at least 34 weeks and residence in an area where at least 20% of the population had an annual income below the poverty line. Maternal human immunodeficiency virus, significant congenital anomalies or infections, intubation or ≥ 4 hours of supplemental oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure for 4 or more days excluded the infant from the study. Overall, 2,090 families were screened, 846 were eligible and consented, and 609 were enrolled; 560 newborns at increased risk for development of asthma because of parental history of asthma or allergic disease and a smaller group of 49 babies whose parents had no history of these diseases were enrolled. Written informed consent was obtained from the women enrolled, and, after birth, from the parent or legal guardian of the child. The detailed study design has been published previously.1

Study assessments

After a practice session at age 33 months, spirometry and IOS were performed at ages 3, 4 and 5 years of age using the Jaeger MasterScreen IOS system (CareFusion, Germany; JLab version 4.65) at all four centers. Volume and flow calibrations were completed each day of use, and cleaning was done at scheduled intervals. Operators at each site were trained and certified for measurements of spirometry and IOS according to standardized procedures.6 All measurements were over-read centrally to ensure quality and consistency.

Both spirometry and IOS maneuvers were performed in the sitting position. IOS was done first followed by spirometry. Participants were asked to hold use of bronchodilator medications (including short-acting beta agonists [4 hours], and anticholinergics, eukotriene modifiers, and long-acting beta agonists [24 hours]) prior to the spirometry and IOS measurement sessions. For IOS, children were instructed to support their cheeks with their hands, and to breathe normally while maintaining a good lip seal on the mouthpiece with the tongue placed under the mouthpiece and with nose clips in place. The goal for the IOS session was to obtain 3 acceptable tests in a maximum of 8 attempts. An acceptable test had a segment of at least 15 seconds of normal tidal breathing, containing at least 4 breaths, within a 30 second test period. The acceptable tests had a concordance of resistance at 10 Hz (R10) ≥ 0.80 (coherence), and were clustered within 20% of the highest R10. The primary IOS variables used for analyses were respiratory system resistance and reactance at 5 Hz (R5 and X5, respectively), and the area of reactance (AX). Spirometry was conducted in accord with the ATS/ERS Statement on Pulmonary Function Testing in Preschool Children (a rapid rise, a smooth descent free from artifacts, and a full return to the baseline at no greater than ten percent of the peak flow).7 Due to the age of the subjects, we used forced expiratory volume in 0.5 seconds (FEV0.5) in place of forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) as the primary spirometric variable for evaluating acceptability and repeatability. The best maneuver was selected by the effort with the largest sum of forced vital capacity and FEV0.5 in subjects producing with at least 2 acceptable curves. Values were recorded if there was only a single acceptable maneuver. A maximum of 8 attempts were allowed.

To provide normative longitudinal data in this population we included children who had acceptable measures for each of the tests at all 3 years without a history of early recurrent wheeze defined a priori as at least 2 wheezing episodes with at least one episode occurring in the current year.

Umbilical cord blood was collected as described previously and cotinine was measured by gas chromatography as a marker for in utero smoke exposure. 1,8

Statistical methods

There were 281, 368, and 427 spirometry and 216, 352, and 402 IOS tests considered for analysis of performance at ages 3, 4, and 5, respectively. Only those maneuvers considered acceptable by the central overreaders were included in further analyses. Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests were performed to compare potential differences in the proportions of participants who attempted and completed acceptable lung function tests with respect to IOS and spirometry. Cochran-Armitage trend tests were examined to determine if trends of increasing proportion of successful maneuvers across time were present, for both spirometry and IOS. Linear trends from a mixed model, adjusted for child’s race/ethnicity, gender, height, and recurrent wheezing, were tested in order to determine whether the mean values of FEV0.5 and IOS measures increased or decreased across time. Only participants with acceptable data at all three years were included in this model.

Linear regression was used to examine relationships between height, maternal smoking during pregnancy as measured by cord blood cotinine, and both spirometry (FEV0.5) and IOS (R5, X5, AX) lung function tests at ages 3, 4 and 5 years of age. Cord blood cotinine was considered as a binary exposure due to a high proportion of data below the limit of detection: above (> 2 ng/ml) versus at or below the limit of detection (≤ 2 ng/ml). All cotinine models were adjusted for child’s race/ethnicity, gender, and height at time of test. Detectable cotinine was considered the independent predictor, and lung function measurement was modeled as the outcome. Models examining an association with height among non-recurrent wheezers are unadjusted.

RESULTS

Study population

Of the 609 participants enrolled initially in the birth cohort study, 503 attended at least one of the three clinic visits of interest. Seventy-one percent were African American, 52% were male and 68% had an annual household income of less than $15,000 (Table 1). There were only differences for site (p=0.04) and race (p=0.04) when comparing the 485 children who attempted one or more lung function tests and those who attended a clinic visit but did not attempt a maneuver (n=18, data not shown). 472, 471 and 479 children attended a clinic visit at ages 3, 4 and 5 years, respectively.

Table 1.

Population Characteristics for those who attended a clinic visit and those who attempted a lung function test.

| Children who attended ≥ 1 clinic visit N=503 |

Children who attempted ≥ 1 pulmonary test N=485 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Study site | ||

| Baltimore | 148 (29%) | 137 (28%) |

| Boston | 115 (23%) | 112 (23%) |

| New York | 96 (19%) | 95 (20%) |

| St. Louis | 144 (29%) | 141 (29%) |

| Mother reported smoked during pregnancy | 89/502 (18%) | 88/484 (18%) |

| Number of smokers in the home | ||

| 0 | 254/497 (51%) | 243/483 (50%) |

| 1 – 2 | 218/497 (44%) | 211/483 (44%) |

| 3+ | 29/497 (6%) | 29/483 (6%) |

| Detectable cord blood cotinine | 65/372 (18%) | 65/372 (18%) |

| Child’s race/ethnicity | ||

| African American | 359 (71%) | 346 (71%) |

| Hispanic | 102 (20%) | 100 (21%) |

| Other | 42 (9%) | 39 (8%) |

| Mother has high school education | 300/497 (60%) | 288/484 (60%) |

| Mother is married | 71/502 (14%) | 69/484 (14%) |

| Annual household income <$15,000 | 344 (68%) | 334 (69%) |

| Child’s gender: male | 260 (52%) | 251 (52%) |

| Caesarean delivery | 153 (30%) | 148 (31%) |

| Child’s birth weight (grams) | 3251 ± 501 | 3254 ± 497 |

| Mother has ever had asthma | 228/501 (46%) | 220/483 (46%) |

| Gestational age of child at delivery (weeks) | 38.8 ± 1.5 | 38.8 ± 1.5 |

| Age of mother at time of birth (years) | 24.4 ± 6.0 | 24.4 ± 6.0 |

Values are counts (percentages) or means ± standard deviations.

Thirty-four percent of the evaluable children had recurrent wheeze at 3 years according to the study a priori definition. Clinical characteristics of the children at ages 3 and 5 are included in Table E1 of the data supplement.,

Successful completion of lung function testing

Overall rates of successfully completed lung function tests increased over time for both spirometry and IOS (trend test p<0.001 for both). At ages 3, 4 and 5 years, 78%, 90% and 93% respectively were willing to perform spirometry and 79%, 89%, and 90% respectively were willing to perform IOS (Figure 1). A higher proportion of children attending clinic visits had acceptable spirometry sessions compared to IOS sessions (Figure 1). At 3 years, 60% of children who attended a clinic visit had an acceptable test with spirometry compared to 46% with IOS maneuver (p<0.001); at 4 years 78% had acceptable spirometry versus 75% with IOS (p=0.22), and at 5 years 89% had acceptable spirometry versus 84% with IOS (p=0.02). Of those children who attempted the tests, 76% had acceptable spirometry and 58% had acceptable IOS at 3 years (p<0.001); 86% had acceptable spirometry and 84% had acceptable IOS at 4 years (p=0.37), and 96% had acceptable spirometry and 93% had acceptable IOS at 5 years (p=0.06). There were no differences in rates of acceptable tests between males and females (data not shown).

Figure 1.

The number of children who attended a clinic visit (darkest shade of blue), attempted to perform a pulmonary function test (middle shade of blue) and had an acceptable pulmonary function test (lightest shade of blue) at ages 3, 4 and 5 years. The number of participants attending, attempting, and completing an acceptable test are shown on top of each stacked bar. Percentages of acceptable spirometry maneuvers were higher than percentages of acceptable IOS measurements at ages 3 and 5 (p<0.001 and p=0.02, respectively). Acceptable test percentages for both IOS and spirometry showed significant improvement over time in a test for trend (p<0.001).

For spirometry at ages 3, 4 and 5 years, 65%, 78% and 92% respectively had 3 acceptable and 2 reproducible efforts. Each of the 4 sites had a high proportion of children who were able to complete at least one acceptable spirometry or IOS test during the 3 years (Table E2 in the data supplement). Reasons for unacceptable spirometry results were provided for 90% (147/163) of unacceptable spirometry sessions and for 98% (247/252) of unacceptable IOS sessions. Specific reasons for unacceptability are shown in Tables 2a and 2b.

Table 2a.

Reasons for unacceptable IOS tests

| Age 3 N=151 |

Age 4 N=66 |

Age 5 N=30 |

Total N=247 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not have minimum of 4 breaths per 15 seconds of data | 71% (107) | 68% (45) | 50% (15) | 68% (167) |

| Tidal breathing was unsatisfactory* | 74% (111) | 82% (54) | 80% (24) | 77% (189) |

| X5 values were positive | 52% (79) | 55% (36) | 30% (9) | 50% (124) |

| Failed to meet coherence criteria | 84% (128) | 88% (58) | 87% (26) | 85% (212) |

| Fewer than 3 acceptable maneuvers | 96% (146) | 95% (63) | 97% (29) | 96% (238) |

| R10 not reproducible | 81% (123) | 89% (59) | 93% (28) | 85% (210) |

Uninterrupted and regular breathing without leak or hyperventilation was required to be considered satisfactory.

Note: Overreaders were able to select all applicable reasons for a session to be considered “unacceptable.” Reasons were provided for 247 of the 252 total unacceptable IOS sessions; 248 answered questions regarding coherence, acceptable number of maneuvers, and reproducibility.

Table 2b.

Reasons for unacceptable spirometry tests

| Age 3 N=81 |

Age 4 N=49 |

Age 5 N=17 |

Total N=147 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effort was submaximal | 37% (30) | 57% (28) | 71% (12) | 48% (70) |

| Glottic closure | 14% (11) | 8% (4) | 12% (2) | 12% (17) |

| Exhale < 0.5 seconds | 17% (14) | 12% (6) | 6% (1) | 14% (21) |

| Equipment malfunction | 2% (2) | 2% (1) | 0% (0) | 2% (3) |

| Other reasons* | 22% (18) | 14% (7) | 0% (0) | 17% (25) |

| 2+ reasons | 7% (6) | 6% (3) | 12% (2) | 7% (11) |

Note: Overreaders answered in free text and most often provided the primary reason that the session was unacceptable; occasionally, two or more reasons were provided. Reasons were provided for 147 of the 163 total unacceptable spirometry sessions.

Other reasons include the following: Participant not cooperating, technician error, inspiratory volumes greater than expiratory, inconsistent expiratory flow, etc.

There were significant correlations between FEV0.5 and the IOS measures at every year (p < 0.001 for all). These correlations ranged from −0.39 to −0.53 for FEV0.5 versus R5, 0.35 to 0.43 for X5, and −0.38 to −0.46 for AX (See Figure E1 in the Online Repository).

Lung function at 3, 4 and 5 years

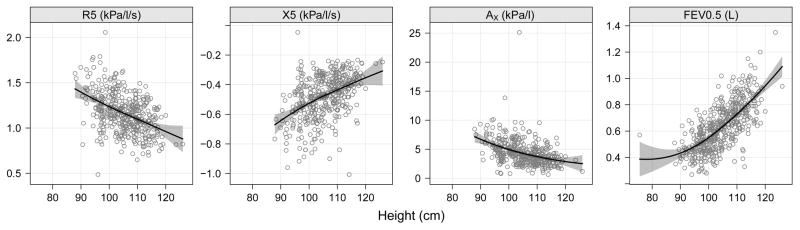

We performed a descriptive analysis of lung function at 3, 4 and 5 years to provide reference data in primarily African American and Hispanic children by examining the relationships between height and FEV0.5, R5, X5 and AX (Figure 2) in children without recurrent wheeze. This analysis excluded children by each year of age who had recurrent wheeze defined as at least 2 wheezing episodes with at least one episode occurring in the current year. The relationship between height and lung function values did not differ by sex, but there were small differences by race/ethnicity (Figure E2 in the Online Repository).

Figure 2.

R5 (kPa/l/s), X5 (kPa/l/s), and AX (kPa/l) and FEV0.5 (L) plotted by height (cm) in URECA children without recurrent wheeze. Each point indicates a raw pulmonary measurement for an associated height. Regression line is plotted from an unadjusted linear model. Spirometry and Impulse Oscillometry in Preschool Children:

Of the non-wheezing children, there were 131 children who performed successful spirometry at all 3 years and 97 children who had acceptable IOS at all 3 years. AX and R5 decreased significantly across time in a linear fashion, while FEV0.5 and X5 significantly increased over time (p<0.001 for all comparisons, Table E3 and Figure E3 in the Online Repository).

Prenatal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and lung function

Table 3 shows the lung function at ages 3 to 5 years as measured by spirometry and IOS in subjects with in utero exposure to smoking compared to those who were not exposed. The median and interquartile range for cord blood cotinine level for the cohort was at the level of detection; 2 ng/ml (2 ng/ml, 2 ng/ml). Cord blood cotinine above the level of detection was only found in 18% of the analysis population, and was associated with significantly higher AX at ages 4 and 5 years (age 4: 5.44 kPa/l versus 4.63 kPa/l, p=0006; age 5: 4.46 kPa/l versus 3.82 kPa/l, p=0.009). There was no association of the cotinine level with FEV0.5 at any age.

Table 3.

Adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals for IOS and spirometry values at ages 3, 4, and 5 by detectable cotinine level at birth.

| Detectable Cotinine | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (≤ 2 ng/ml) N=307 |

Yes (> 2 ng/ml) N=65 |

||

| Age 3 | |||

| FEV0.5 (L/s) | 0.50 (0.49, 0.51) | 0.47 (0.44, 0.50) | 0.09 |

| R5 (kPa/l/s) | 1.31 (1.27, 1.34) | 1.30 (1.23, 1.37) | 0.83 |

| X5 (kPa/l/s) | −0.56 (−0.58, −0.53) | −0.51 (−0.56, −0.45) | 0.10 |

| AX (kPa/l) | 5.49 (5.17, 5.81) | 5.46 (4.80, 6.12) | 0.91 |

| Age 4 | |||

| FEV0.5 (L/s) | 0.62 (0.61, 0.63) | 0.59 (0.56, 0.62) | 0.19 |

| R5 (kPa/l/s) | 1.19 (1.17, 1.22) | 1.25 (1.19, 1.30) | 0.12 |

| X5 (kPa/l/s) | −0.51 (−0.53, −0.49) | −0.54 (−0.59, −0.50) | 0.30 |

| AX (kPa/l) | 4.63 (4.40, 4.85) | 5.44 (4.97, 5.92) | 0.006 |

| Age 5 | |||

| FEV0.5 (L/s) | 0.77 (0.75, 0.78) | 0.76 (0.73, 0.79) | 0.89 |

| R5 (kPa/l/s) | 1.10 (1.07, 1.12) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.18) | 0.15 |

| X5 (kPa/l/s) | −0.44 (−0.45, −0.42) | −0.47 (−0.51, −0.44) | 0.08 |

| AX (kPa/l) | 3.82 (3.62, 4.01) | 4.46 (4.04, 4.87) | 0.009 |

Values are adjusted mean estimates (95% confidence intervals) and p-values from a linear regression model adjusted for race/ethnicity, gender, and height of participant at time the pulmonary measurement was taken.

DISCUSSION

This study compared the performance of 3–5 yearold predominantly African American and Hispanic children in spirometry and IOS. IOS is generally believed to be easier than spirometry for young children in that it requires less active effort. The results of this study do not support this assumption. The data show that more than half of 3 yearold children can perform acceptable spirometry and slightly less than half can perform acceptable IOS maneuvers. The data confirm that pulmonary function testing can be performed with a high degree of success in 4 and 5 yearold children, although the success rate remained higher with spirometry. This is in line with our clinical observation that it is easier to get young children to blow hard than it is to have them sit still and breathe quietly on a mouthpiece for 30 seconds.

A longitudinal study by Guilbert et al compared spirometry and IOS in 4 and 5 yearold children.21 They found no differences between the two tests in the percent of acceptable tests. However, the percent of acceptable tests for both spirometry and IOS were much lower than in our study. At 4 years of age, 84% of children who attempted IOS had acceptable tests compared to 21% in the Guilbert study and 86% who attempted spirometry had acceptable tests compared to 24%. At 5 years of age, 93% of children who attempted IOS had acceptable tests compared to 58% in that study and 96% who attempted spirometry had acceptable tests compared to 57%.21

We used FEV0.5 as our primary spirometric measure because children in this age group typically have short forced expiratory time, and empty their lungs in less than one second. Using FEV0.5 in studies of young children helped achieve a greater frequency of acceptable maneuvers as similarly reported in other studies.9,22,23 Our success rates with spirometry for each age group between the ages of 3 and 5 years are consistent with other studies reporting FEV0.5 with smaller numbers of children.9,12,22

The study demonstrated that both spirometry and IOS can be performed reliably and consistently in a multicenter study. This was achieved by having centralized training and overreading with feedback to those performing the tests. The longitudinal study design of URECA is a factor that may have contributed to the high success rates in performing the tests. A practice session to familiarize the children with the equipment and procedures was held at 33 months and the first attempt at performing the tests was at 3 years. By ages 4 and 5, the children were experienced. Prior experience can improve performance on pulmonary function testing.24,25

Strict quality control procedures were in place for this study. Research assistants were trained to accept studies without physical artifacts and all the studies were overread centrally. We required at least 3 acceptable maneuvers with reproducibility within 20% at R10 for IOS. One criterion used for acceptability of an IOS maneuver was coherence value of ≥ 0.80 at 10 Hz similar to one used in the Childhood Asthma and Research Education network studies.26 As noted in the ATS/ERS statement on pulmonary function testing, there is no systematic study of cutoff values for coherence in preschool children.7 There were no instances where coherence was the only criterion for exclusion in our study.

Several factors must be taken into consideration in making comparisons of our values for spirometry and IOS in preschool children without recurrent wheeze to those published in other studies of healthy children. The study population was representative of Black and predominantly Puerto Rican and Dominican Hispanic preschool children in whom there are limited published data. In addition, prior studies were cross-sectional and had smaller sample sizes particularly at the lower end of the age range.27–30 The FEV0.5 in our study is comparable to the healthy children in this age group reported by Nystad et al.9 Our data are also in the range of those reported by Kampschmidt et al whose subjects included Hispanics.11 However, 26% of children in that study had a previous diagnosis of asthma. Comparisons to other spirometry studies are limited by small sample sizes in the 3 year-old age group and inclusion of children with a history of wheezing or asthma. Our values for R5 are in the range of the comparative data of several studies reported by Malmberg et al.30 and for AX published by Calogero et al.15 The measures of R5 and X5 at 4 years are similar to a study of 45 predominantly Hispanic and African American 4 year-old children without asthma.18

Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with deficits in lung function at birth and infancy.3,4,31 Most studies in offspring of mothers who smoked during pregnancy assessed pulmonary function in infancy or after age 5 but there is limited data between 3 and 5 years of age. Using IOS, Gray et al demonstrated that 6–10 week old healthy African infants whose mothers smoked during pregnancy had lower compliance than infants not exposed to tobacco smoke during pregnancy.5 In a longitudinal study, Turner et al reported that lung function was diminished between 1 month and 12 months with the thoracoabdominal compression technique and again at 6 years with spirometry, but no measurements were made between 12 months and 6 years. Our study found that cotinine was associated with greater area of reactance but not lower FEV0.5. This suggests that IOS may be better than spirometry in detecting the deficits in lung function in this age group associated with in utero exposure to maternal smoking. Experimental studies in animal models indicate that in utero nicotine exposure increases collagen and decreases elastin in the lung. Our findings are in line with the fact that IOS measures mechanical properties of the respiratory system that include resistive and elastic properties.32 In addition to effects of smoking on mechanical properties, central airway shunting or peripheral inhomogeneities may affect the AX results. Although one cannot extrapolate our findings regarding the ability of IOS to distinguish physiologic differences in other diseases better than spirometry, our results are consistent with a study in 4 year-old children demonstrating that IOS was better than spirometry at discriminating asthma on the basis of their bronchodilator response.18 In contrast, spirometry was better able to detect lung disease in preschoolers with cystic fibrosis.28

Interestingly, cord blood cotinine was more closely associated with reduced lung function at ages 4 and 5 years than at 3 years. This could be due to ascertainment bias (older children were more likely to successfully complete the test) or progressive changes in lung function. Additional follow-up of these children may help resolve this question.

There are unique aspects to this study. This is one of the largest studies to compare IOS and spirometry in preschool children followed prospectively, and unlike other studies, has a large number of children at 3 years. Results from URECA children without a history of recurrent wheeze provide reference data since there are limited data on spirometry and IOS in African American and Hispanic children in this age group. Of note is that the Hispanic children in this cohort were predominantly Caribbean. Furthermore, similar rates of success with lung function testing were obtained at multiple medical centers, providing evidence that these results are generalizable. It is important to consider that the high rates of success at ages 4 and 5 years might be partially due to experience gained by the children during the visits at age 3 years and practice is also likely to be helpful in the clinical setting. Finally, we present longitudinal data that allowed us to examine the ability of the two methods to detect deficits in lung function between 3 and 5 years associated with exposure to smoking during pregnancy.

There are limitations to this study that should be noted. The number of children that did not attempt a pulmonary function test may have been affected by fatigue because testing was part of a visit that included questionnaires. The results may not be generalizable to different racial/ethnic or higher socioeconomic populations. One limitation of using cord blood cotinine as a marker of transplacental passage of nicotine and its metabolites is that it reflects exposure in late gestation but not chronic exposure.

In summary, both spirometry and IOS can be used successfully in studies of lung function in preschool children in a low-socioeconomic population. Despite the theoretical advantages of IOS over spirometry on performance of pulmonary function, there was a higher rate of acceptable spirometry in younger children. Although the two tests are correlated, IOS may be able to detect changes in respiratory system properties and reflect peripheral airway obstruction not seen with usual spirometric measures.

Supplementary Material

HIGHTLIGHTS.

What is already known about this topic? Measuring pulmonary function in preschool children is challenging. IOS does not require active exhalation so it is believed to be easier for children to perform than spirometry.

What does this article add to our knowledge? This direct comparison of performance of spirometry and IOS indicates that more preschool children can perform acceptable spirometry tests than acceptable IOS tests and provides longitudinal data in an African American and Hispanic population.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? This study challenges the assumption that IOS is easier for preschool children to perform than spirometry but the ability of IOS to detect the effects of cigarette smoke exposure on lung function may be better.

Acknowledgments

The Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma Study is a collaboration of the following institutions and investigators (principal investigators are indicated by an asterisk; protocol chair is indicated by double asterisks): Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD – R Wood*, E Matsui, H Lederman, F Witter, J Logan, S Leimenstoll, D Scott, L Daniels, L. Miles, D. Sellers, A Swift; Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA – G O’Connor*, W Cruikshank, M Sandel, A Lee-Parritz, C Jordan, E Gjerasi, P. Price-Johnson, B. Caldwell, M Tuzova; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA – D Gold, R Wright; Columbia University, New York, NY – M Kattan*, C Lamm, N Whitney, P Yaniv, C Sanabia, A Valones; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY – H Sampson, R Sperling, N Rivers; Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO – G Bloomberg*, L Bacharier, Y Sadovsky, E Tesson, C Koerkenmeier, R Sharp, K Ray, J Durrange, I Bauer; Statistical and Clinical Coordinating Center - Rho, Inc, Chapel Hill, NC – H Mitchell*, P Zook, C Visness, M Walter, R Bailey, K. Jaffee, W Taylor, R Budrevich; Scientific Coordination and Administrative Center – University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI – W Busse*, J Gern**, P Heinritz, C Sorkness, M Burger, K Grindle, A Dresen; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD – P Gergen, A Togias, E Smartt.

Funding:

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, under Contract numbers NO1-AI- 25496, NO1-AI-25482, HHSN272200900052C, and HHSN272201000052I. Additional support was provided by the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, under grants RR00052, M01RR00533, 1UL1RR025771, M01RR00071, 1UL1RR024156, UL1TR000040, and 5UL1RR024992-02.

Abbreviations

- ATS

American Thoracic Society

- Ax

Area of Reactance

- ERS

European Respiratory Society

- FEV

Forced Expiratory Volume

- FOT

Forced Oscillation Technique

- IOS

Impulse Oscillometry

- kPa

Kilopascal

- R5

Resistance at 5 Hz

- R10

Resistance at 10 Hz

- Rrs

Respiratory System Resistance

- URECA

Urban Environmental and Childhood Asthma Study

- X5

Reactance at 5 Hz

- Xrs

Respiratory System Reactance

- Zrs

Impedance of the Respiratory System

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

M. Kattan reports personal fees from Novartis Pharma. L. B. Bacharier has consultant arrangements with Aerocrine, GlasoSmithKline, Genentech/Novartis, Cephalon, Teva, and Boehringer Ingelheim; has received personal fees from Merck, DBV Technologies, AstraZeneca, WebMD/Medscape, Sanofi, Vectura, and Circassia. G. T. O’Connor has received a grant from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and has consultant arrangements with AstraZeneca. R. Cohen and R. Sorkness have nothing to disclose. W. Morgan reports grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; personal fees from Genentech, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, American College of Chest Physicians, and American Thoracic Society. J. Gergen, K. F. Jaffee, and C. M. Visness have nothing to disclose. R. A. Wood has received grants from the NIH, DBV, Aimmune, Astellas, and HAL-Allergy; has consultant arrangements with Stallergenes; and receives royalties from UpToDate. G. R. Bloomberg and S. Doyle have nothing to disclose. R. Burton has consultancy arrangements with eResearch Technologies (ERT). J. E. Gern has received personal fees from Janssen, Regeneron, and PReP Biosciences; and has received travel support from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gern JE, Visness CM, Gergen PJ, Wood RA, Bloomberg GR, O’Connor GT, et al. The Urban Environment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) birth cohort study: design, methods, and study population. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2009;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenfeld M, Allen J, Arets BH, Aurora P, Beydon N, Calogero C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: optimal lung function tests for monitoring cystic fibrosis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and recurrent wheezing in children less than 6 years of age. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2013;10:S1–S11. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201301-017ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner S, Fielding S, Mullane D, Cox DW, Goldblatt J, Landau L, et al. A longitudinal study of lung function from 1 month to 18 years of age. Thorax. 2014;69:1015–20. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McEvoy CT, Schilling D, Clay N, Jackson K, Go MD, Spitale P, et al. Vitamin C supplementation for pregnant smoking women and pulmonary function in their newborn infants: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2014;311:2074–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray D, Czovek D, Smith E, Willemse L, Alberts A, Gingl Z, et al. Respiratory impedance in healthy unsedated South African infants: effects of maternal smoking. Respirology. 2015;20:467–73. doi: 10.1111/resp.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. The European respiratory journal. 2005;26:319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beydon N, Davis SD, Lombardi E, Allen JL, Arets HG, Aurora P, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: pulmonary function testing in preschool children. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;175:1304–45. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-642ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eigen H, Bieler H, Grant D, Christoph K, Terrill D, Heilman DK, et al. Spirometric pulmonary function in healthy preschool children. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2001;163:619–23. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2002054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nystad W, Samuelsen SO, Nafstad P, Edvardsen E, Stensrud T, Jaakkola JJ. Feasibility of measuring lung function in preschool children. Thorax. 2002;57:1021–7. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.12.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zapletal A, Chalupova J. Forced expiratory parameters in healthy preschool children (3–6 years of age) Pediatric pulmonology. 2003;35:200–7. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kampschmidt JC, Brooks EG, Cherry DC, Guajardo JR, Wood PR. Feasibility of spirometry testing in preschool children. Pediatric pulmonology. 2016;51:258–66. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pesant C, Santschi M, Praud JP, Geoffroy M, Niyonsenga T, Vlachos-Mayer H. Spirometric pulmonary function in 3- to 5-year-old children. Pediatric pulmonology. 2007;42:263–71. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilozni D, Barak A, Efrati O, Augarten A, Springer C, Yahav Y, et al. The role of computer games in measuring spirometry in healthy and “asthmatic” preschool children. Chest. 2005;128:1146–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisgaard H, Klug B. Lung function measurement in awake young children. The European respiratory journal. 1995;8:2067–75. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08122067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calogero C, Parri N, Baccini A, Cuomo B, Palumbo M, Novembre E, et al. Respiratory impedance and bronchodilator response in healthy Italian preschool children. Pediatric pulmonology. 2010;45:1086–94. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall GL, Sly PD, Fukushima T, Kusel MM, Franklin PJ, Horak F, Jr, et al. Respiratory function in healthy young children using forced oscillations. Thorax. 2007;62:521–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.067835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klug B, Bisgaard H. Measurement of lung function in awake 2–4-year-old asthmatic children during methacholine challenge and acute asthma: a comparison of the impulse oscillation technique, the interrupter technique, and transcutaneous measurement of oxygen versus whole-body plethysmography. Pediatric pulmonology. 1996;21:290–300. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199605)21:5<290::AID-PPUL4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marotta A, Klinnert MD, Price MR, Larsen GL, Liu AH. Impulse oscillometry provides an effective measure of lung dysfunction in 4-year-old children at risk for persistent asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2003;112:317–22. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen KG, Bisgaard H. Lung function response to cold air challenge in asthmatic and healthy children of 2–5 years of age. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2000;161:1805–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9905098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis RA. The determination of nicotine and cotinine in plasma. Journal of chromatographic science. 1986;24:134–41. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/24.4.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guilbert TW, Singh AM, Danov Z, Evans MD, Jackson DJ, Burton R, et al. Decreased lung function after preschool wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in children at risk to develop asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011;128:532–8. e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aurora P, Stocks J, Oliver C, Saunders C, Castle R, Chaziparasidis G, et al. Quality control for spirometry in preschool children with and without lung disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2004;169:1152–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200310-1453OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vilozni D, Bentur L, Efrati O, Minuskin T, Barak A, Szeinberg A, et al. Spirometry in early childhood in cystic fibrosis patients. Chest. 2007;131:356–61. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crenesse D, Berlioz M, Bourrier T, Albertini M. Spirometry in children aged 3 to 5 years: reliability of forced expiratory maneuvers. Pediatric pulmonology. 2001;32:56–61. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanengiser S, Dozor AJ. Forced expiratory maneuvers in children aged 3 to 5 years. Pediatric pulmonology. 1994;18:144–9. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950180305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen GL, Morgan W, Heldt GP, Mauger DT, Boehmer SJ, Chinchilli VM, et al. Impulse oscillometry versus spirometry in a long-term study of controller therapy for pediatric asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2009;123:861–7e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hellinckx J, De Boeck K, Bande-Knops J, van der Poel M, Demedts M. Bronchodilator response in 3–6. 5 years old healthy and stable asthmatic children. The European respiratory journal. 1998;12:438–43. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerby GS, Rosenfeld M, Ren CL, Mayer OH, Brumback L, Castile R, et al. Lung function distinguishes preschool children with CF from healthy controls in a multi-center setting. Pediatric pulmonology. 2012;47:597–605. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klug B, Bisgaard H. Specific airway resistance, interrupter resistance, and respiratory impedance in healthy children aged 2–7 years. Pediatric pulmonology. 1998;25:322–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199805)25:5<322::aid-ppul6>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malmberg LP, Pelkonen A, Poussa T, Pohianpalo A, Haahtela T, Turpeinen M. Determinants of respiratory system input impedance and bronchodilator response in healthy Finnish preschool children. Clinical physiology and functional imaging. 2002;22:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tager IB, Ngo L, Hanrahan JP. Maternal smoking during pregnancy. Effects on lung function during the first 18 months of life. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1995;152:977–83. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekhon HS, Keller JA, Proskocil BJ, Martin EL, Spindel ER. Maternal nicotine exposure upregulates collagen gene expression in fetal monkey lung. Association with alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2002;26:31–41. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.1.4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.