Abstract

Objective

Patient and clinician goal alignment, central to effective patient-centered care, has been linked to improved patient experience and outcomes, but has not been explored in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). This study aimed to explore goal conceptualization among RA patients and clinicians.

Methods

Seven focus groups and one semi-structured interview were conducted with RA patients and clinicians recruited from four rheumatology clinics. An interview guide was developed to explore goal concordance related to RA treatment. Researchers utilized a concurrent deductive-inductive data analysis approach.

Results

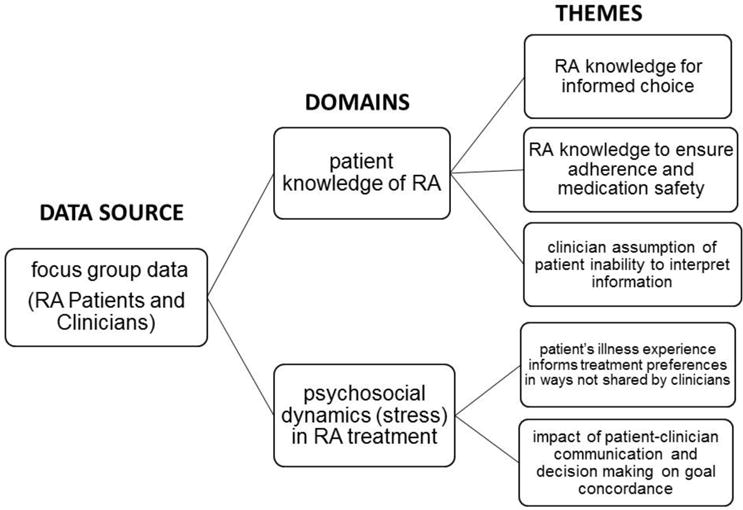

19 patients (mean age 55; 74% female; 32% nonwhite; 26% Spanish speakers) and 18 clinicians (44% trainees; 44% female; 28% nonwhite) participated. Across clinician and patient focus groups, two domains were identified: 1) patient knowledge of RA and 2) psychosocial dynamics (stress) in RA treatment. Within the knowledge domain, three themes emerged: 1) RA knowledge for informed choice; 2) RA knowledge to ensure adherence and medication safety; and 3) clinician assumption of patient inability to interpret information. Within the second domain of RA and stress, two themes emerged: 1) patient’s illness experience informs treatment context in ways not shared by clinicians; and 2) impact of patient-clinician communication and decision making on goal concordance.

Conclusion

Knowledge is a shared goal, but RA patients and clinicians hold divergent attitudes towards this goal. While knowledge is integral to self-management and effective shared decision making, mismatch in attitudes may lead to suboptimal communication. Tools to support patient goal-directed RA care may promote high quality patient-centered care and result in reduced disparities.

BACKGROUND

Elicitation of patient goals for health and alignment with clinician goals has gained prominence in many areas of medicine, including oncology, end of life care, and among patients with multi-morbidity [1, 2]. The concept of goal concordance, or agreement, between patients and clinicians has been studied most commonly in diabetes [3, 4]. Patients and clinicians may inherently approach goal setting differently based on diverse knowledge bases and competing priorities, and thus may have very different goals. Goals may reflect patients’ desire to reach activity targets, whereas clinician goals may focus on clinical targets. Studies have demonstrated that goal concordance leads to better outcomes such as higher patient diabetes care self-efficacy and self-management [3, 4], however goal concordance has yet to be examined in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Clinical goals for RA treatment have been outlined in European and American rheumatology society guidelines [5–7], which underscore the importance of shared decision-making in treating to a target of remission or low disease activity. RA patient goals are broad, focused on quality of life, maintaining wellness, and social connectedness [8]. Despite clinically-oriented treat-to-target guidelines focused on biological outcomes, disparities persist, specifically for racial/ethnic minorities, immigrants and non-English speakers [9, 10]. Given the complex self-management and patient-reported outcomes necessary to measure RA disease activity, clear communication is essential to high quality care. However, suboptimal communication around shared decision-making has been documented among diverse RA populations [11].

Establishing patient and clinician perspectives on RA therapy goals is paramount given the need for patient engagement and shared decision making to provide patient-centered care. While patients and clinicians may share treatment goals, such as pain reduction and increased function, understanding what goals mean and how goals can be achieved may differ based on knowledge of disease, health literacy, individual perspective or prior experience. Explicit conversations with patients about their goals may lead to more focused treatment discussions, care aligned with preferences and values, reduce harm, and avoid waste. Therefore, the study objective was to explore and compare the conceptualization of shared goals among rheumatologists and a diverse group of RA patients.

METHODS

Recruitment

Eligible patients and clinicians were recruited from four rheumatology clinics: a university-based arthritis clinic and county hospital RA clinic in San Francisco, California, and a university-based arthritis clinic and Veterans Affairs-based clinic (VA) in Portland, Oregon. Eligible patient participants were 18 or older, spoke English or Spanish, and had a physician diagnosis of RA. Eligible clinicians included rheumatology fellows or attending rheumatologists at two academic medical centers. Research assistants recruited potential participants to attend one of eight possible focus groups. Focus groups were chosen as an established method of qualitative data collection widely used within health services research for the elicitation of perspectives shared within a group with a common characteristic [12]. Due to potential power differentials that might inhibit candid discussion about RA goals, patients and clinicians participated in separate focus groups. Veterans were invited to participate in a separate focus group to capture any unique aspects of the VA healthcare system. In addition, Spanish speakers were invited to participate in separate focus groups.

Procedure

Experienced researchers with qualitative training facilitated English and Spanish language focus group discussions per the interview guide developed by study team members (CJK, JB, SO). A standardized interview guide used across groups covered five main areas: self-introductions; hopes, expectations or goals for RA treatment; communication of hopes/expectations in clinical visits; feasibility and acceptability of technology to facilitate goal elicitation. The bilingual Spanish group moderator translated the English version into Spanish prior to the focus group. The clinician interview guide mirrored the patient guide, but directed clinicians to consider their perceptions of and experiences with patient goals. All focus groups were audio-recorded. At each session, a trained observer recorded field notes that contained both descriptive and reflexive information about the setting, non-verbal behaviors, and who was speaking in the discussion.

Data Analysis

Audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service or a member of the research team. The Spanish-language groups were simultaneously translated and transcribed. Personal identifiers were removed during the transcription process to protect privacy and confidentiality. The transcript documents were uploaded into the software Atlas.ti (GmbH 2002-1017) for data management and analysis.

Researchers (EH, AS, JB) used a concurrent deductive-inductive approach to data analysis. Codes identifying goal concordance or discordance constituted the deductive portion of the analysis. Transcripts were also open coded using principles of applied thematic analysis [13] to identify inductive themes and codes then iteratively developed and consolidated based on data across focus group discussions. These emergent themes were considered in relation to findings on goal concordance or discordance, resulting in two domains and the analysis. Researchers first identified a shared goal among patients and clinicians using a deductive approach in line with the primary study objective and then employed an inductive approach to explore how conceptualization of the shared goal differed across patient and clinician groups. This approach allowed for flexibility in the observation of relevant patterns in the data and emergent themes, while keeping the analytic process aligned with study objectives.

The research protocol was approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research and the joint Institutional Review Board of Oregon Health & Science University and the VA Portland Health Care System.

RESULTS

A total of 19 patients (mean age 55; 74% women; 32% non-white; 26% Spanish-speaking) and 18 clinicians (44% trainees; 44% women; 28% non-white) participated in seven focus groups and one semi-structured interview. Three focus groups were with clinicians and four with patients (Appendix 1). One planned focus group became a semi-structured interview because only one participant attended the session (Spanish-speaking patient).

As a result of the inductive analytic approach described above, two domains were identified that were relevant across clinician and patient focus groups: 1) patient knowledge of RA and 2) psychosocial dynamics (stress) in RA treatment. Within the first domain, knowledge of RA emerged as important for making informed choice and for ensuring adherence and medication safety; with clinicians’ assumption of patient inability to interpret information influencing their expectations of patient knowledge (see Figure 1). Within the second domain of RA and stress, patient’s illness experiences informed treatment preferences in ways not shared by clinicians; and impacted patient-clinician communication and decision making in ways that influenced goal concordance. We describe these qualitative findings in detail below.

Figure 1.

legend. Domains and sub-themes identified in focus groups of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and clinicians in rheumatology clinics.

Patient Knowledge of RA

RA knowledge for informed choice

In discussions of treatment goals, patients stated they desired more RA knowledge, including information on: disease process, research developments, how medications work, and side effects. Patients described a process of knowledge seeking upon learning of their diagnosis to understand the “how and why” of their illness.

When I first was diagnosed, I just like ate up everything I could about it to try and understand… It was like, oh okay, so they’re treating with anti-inflammatories. Well, that is way down the list in terms of this cascade of activity that’s happening in my body. I want to back up a few steps and get to the root. [Patient 11]

Building upon the “how and why” of RA, patients described researching information about medications and other aspects of treatment on the Internet and other sources to educate themselves and inform questions to ask clinicians.

… when I’m prescribed a medication, I’ll go and look it up on the Internet; what the side effects are, how is it going to benefit my body, what’s going to hurt my body. And based on that, I think, “Okay, if it’s going to have this effect on me, then I need to ask my doctor. Maybe next time she should monitor my liver,” for example, because it’s going to affect my liver. [Patient 2]

In other instances, self-education on RA was a way for patients to fill a gap they attribute to clinicians.

I didn’t use to read all the information that comes with the medicines where the side effects are described. Now, I pay more attention to that information, but that’s something the doctor has never given me. [Patient 17]

A subset of clinicians connected patient receipt of RA knowledge to patient choice and shared decision making.

I think it’s important to discuss with the patient what are the consequences of potential ongoing inflammation and that there may be damage. But if the patient, ultimately, understands this and is taking this risk [to forgo treatment], I think that’s their choice. But to me, what’s most important is they truly do understand it. [Clinician 9]

Patients highlighted the importance of RA knowledge to understanding what was happening to them physically and the impact of medication on their bodies, and their need to seek information outside of the clinical visit. Some clinicians acknowledged that patients make choices that may or may not align with clinician recommendations.

RA knowledge to ensure adherence and medication safety

While some clinicians addressed educating patients about RA to maximize patients’ decision making ability, many clinicians connected RA education to risk of non-adherence and medication safety.

I explained to her that this is the risk. It can happen to anyone. But if you don’t take treatment, you see pretty much what the consequences are. So, it might be more like how things will be like in the next few months. And so, she recognized that and got back on treatment. [Clinician 1]

…making sure that their [patient’s] goal is always safety and making sure there are no medication side effects. So, that’s one of my goal[s]. [Clinician 4]

Clinicians reported other aspects of medication counseling that included educating patients on risks of side effects, possible interactions, abstaining from or minimizing alcohol consumption, and administration of biologic therapies. In addition, clinicians expressed using patient education as a way to obtain patient “buy-in” to support clinician treatment plans.

I like to quote studies saying that we know if our best chance of you having a mild or premature arthritis is to get your inflammation under control, that’s why I prefer to go to the medical literature. And I just try to get them to buy into that. Get their inflammation under control, rather than saying “do you want me to try to get your inflammation under control?” [Clinician 13]

For most clinicians, the primary purpose of patient education was to make patients aware of consequences of disease progression without treatment and risks associated with medications. Patients spoke of medication safety in relation to RA knowledge seeking for the purposes of increasing their awareness of the disease process and to support treatment decision making. Patients did not discuss their adherence to clinician treatment recommendations, though patients expressed dissatisfaction with clinicians who they believed dismissed their medication concerns.

Clinician assumption of patient inability to interpret information

Many clinicians expressed frustration when patients engaged in self-education activities, such as looking up information on the Internet about medications or complementary therapies for RA.

There are many who still refuse to take therapy. There’s some beliefs or concerns or because they read a lot on the Internet and get the wrong ideas. [Clinician 10]

…the Internet, that’s the primary source I think people read about rheumatoid arthritis. And oftentimes, what they have read and what they have gained from this reading is not always correct. [Clinician 11]

In addition to clinician frustration associated with patient self-education efforts, clinicians highlighted the differences in perspectives surrounding complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments.

We have a very different perspective on CAM [complementary and alternative medicine] than our patients have and that’s based on clinical trials and the lack of evidence of data. [Clinician 8]

Patients seemed aware of some clinicians’ dismissal of other information sources and described occasions when clinicians diminished the importance of information patients introduced.

In Mexico, for example, people believe that if you have arthritis you should stay off red meat. I have asked about that to three doctors here and they have all laughed at me. [Patient 17]

Several clinicians voiced perceived paradoxes in current expectations of their professional role as an expert who also defers to patient preferences. Many clinicians voiced frustration with patients seeking knowledge from what they considered unreliable sources, which prompted varying levels of comfort among clinicians with some adopting a more paternalistic stance. Fellows in training were less likely to articulate such attitudes.

We want to be patient focused, patient-centered. And they get the final say. But we know best. And unless we can really educate them to the point where they could be making informed decisions, there’s always going to be that dilemma in the room. [Clinician 2]

Patients’ choices are based on what they read and what they think is the best thing for them. And those choices are severely biased, I mean usually. And it sounds pompous to say that we know better, but we do know better in how to treat rheumatoid arthritis than the patients know how to treat rheumatoid arthritis. They may or may not take it. [Clinician 13]

Sometimes in the end, you still do feel like you’re trying to convince them to take something. It’s sort of uncomfortable, you know. [Clinician 15]

Psychosocial Dynamics in RA Treatment

Patients and clinicians discussed how psychosocial dynamics, or stress of the RA illness experience impacted treatment and social life. Patients expressed desire for consideration of their treatment goals in the context of their entire lives, while clinicians pointed to their own inability to address broader patient concerns. Both patients and clinicians acknowledged communication challenges associated with a mismatch in treatment priorities.

Illness experience informs treatment context

Patients described feelings of sadness surrounding the loss of ability to fully engage in everyday activities because of pain or fatigue. This translated into treatment goals involving pain reduction and increased energy, while minimizing side effects.

To have a little more energy or something so I feel more motivated to do my things. [Patient 8]

Like Enbrel, for example; it has a lot of side effects, right? So, I thought it over a lot before making the decision to get the Enbrel injections. But at the same time, I was thinking, “Okay, well, if I have only one year to live and I’m going to be in pain the whole time, then I better inject the medication and live well and pain free for a year” you know what I mean? [Patient 2]

In contrast, clinicians talked about using objective clinical markers to identify treatment goals. While clinicians acknowledged that patients experience significant psychosocial stress, they pointed to their own inability to address these concerns given time constraints and resources available.

I think most rheumatologists care about their patients and want to hear how they’re doing and that sort of thing and that, in and of itself, can be somewhat therapeutic. But in terms of really addressing, in a sense attacking the mental health issue with referrals and medications and therapy and all sorts of – I think sometimes it’s just sort of out of our domain and so I think people just, because of that issue, perhaps don’t feel comfortable. [Clinician 16]

…there are patients where all the psychosocial stuff fills the room and takes a lot of space in the visit. So, that ironically gets in the way of being able to start to systematically address a lot of the goals. [Clinician 12]

Both patients and clinicians noted a lack of societal recognition of how RA affects patient lives and exacerbates the psychosocial impact of RA.

I wish there was compassion…understanding about me in this body that has RA. Because from family, friends, healthcare professionals, it’s just sometimes there is this aloneness. [Patient 11]

And you get automatic empathy ‘cause you have cancer and now you’re going to be a cancer survivor, right? But you tell somebody you have rheumatoid arthritis, I mean, what do you get? You don’t get a ribbon. You don’t get the NFL wearing pink all October. [Clinician 8]

Lastly, both patients and clinicians frequently acknowledged the role that fear plays in the RA illness experience. Patients related fear to the initial diagnosis and learning to cope with RA, which was either exacerbated or attenuated by information seeking behaviors. Clinicians discussed fear as an aspect that disrupted effective communication and complicated patient willingness to follow treatment recommendations.

She said to me ‘all I hear is there’s a one-in-10,000 chance that I could die if I take this drug.’ Well, if I don’t tell her that, I’m culpable. But by telling her that, you know, that’s what resonated with her. And now getting her to take a medication that I strongly believe is in her best interest is nearly impossible. [Clinician 2]

If I or my family have a history, will I risk to get it again by taking the medicine they are giving me when the doctor hasn’t even told me about those risks or asked me if I’m willing to take those risks? They just give it to you and that’s it. They don’t even know if you’re willing to take the risk of dealing with the side effects the medicines can have. [Patient 14]

Matching Priorities: Impact on communication and decision making

Both patients and clinicians described the process of communication surrounding treatment goals as involving a matching of priorities. For example, one clinician described having to convince patients, concerned about pain, to prioritize addressing underlying damage, which may or may not result in changes in pain:

So, you put them on a medication and they improve. But they still have active inflammation. But they feel so much better compared to where they were. You start a conversation with them, you know, I think we need to try something else or increase the dose of this. And we still have a ways to go. And they’re saying, I can still hunt. I can still go to work. I feel fine. I don’t think I need anything. Those are tough patients because we know there’s probably ongoing damage, even though they’re symptomatically improved. [Clinician 13]

Several patients described a negotiation process in which they had to determine what is both possible and practical given the context of their lives when discussing goals with their clinicians.

I think it’s a realistic combination of my goals and, you know, history saying that this will happen…my goals would be never to have any pain and to take no medicine, but, you know, we meet in the middle somewhere…the pain will be there, but we want to stop the crippling effect, and not damage any internal organs. [Patient 3]

Both patient and clinician participants reported communication difficulties when mismatches in treatment strategies arose.

It’s hard to emphasize the points that I think are important when the doctor just misses it… in particular, I think that my rheumatoid has been advancing in these two fingers…in these two joints. And he will say, well, you can take the Prednisone. Well, Prednisone doesn’t do very much. I mean, it also messes up your sleep. [Patient 18]

…the patient was not willing to take anything. So most of the time, we didn’t even talk about the treatment. We were just trying to talk about how he has chronic disease. [Clinician 1]

Patients indicated that clinician goals focused on objective clinical markers and helping patients achieve remission; however, patients expressed a desire for clinicians to look beyond clinical markers and consider patients’ quality of life goals as well as being open to multiple treatment possibilities.

DISCUSSION

This novel qualitative study of RA patients and clinicians who treat RA identified two overarching domains that enhance our understanding of how treatment goals are defined and set. These findings highlight the tension between having an explicit shared goal between clinicians and patients, and experiencing inherently different – and at times opposing – conceptualization of how one formulates or achieves said goal. Improving patient knowledge of RA was identified as a shared goal, however, clinicians may utilize transfer of knowledge efforts to impose clinician- or guideline-oriented goals (e.g. reduce inflammation, stall disease progression) without broader consideration of patient preferences. Patients’ desire for information on a range of RA topics is important, but the value attached to that knowledge is where patients and clinicians diverge.

These results are consistent with prior studies of RA patient goals [8] which identified the importance of the bodily experience (less pain, better function), achieving normalcy and maintaining wellness, social support and interpersonal interactions, such as clear communication with clinicians. In addition to confirming prior studies, this study adds to a growing literature which supports patient goal-directed care [1] in multimorbidity (approximately two-thirds of RA patients are multimorbid) [14], and underscores the need to provide truly “person-centered” care [15]. This approach focuses on treating patients “as persons” [16], delivering care according to what matters most to them, and requires clinician training to elicit and confirm patient goals when discussing options.

Goal concordance has been associated with improved outcomes in diabetes and end of life care, [3, 17]. This current study builds upon prior literature by identifying goals important to both patients and clinicians but also exposes the complexity of how experience and context shape goals and highlights areas for improved communication. Clinicians expressed frustration and identified constraints on time and resources as barriers to exploring patients’ goals. This response points to a need for system change (e.g., reduce burden of documentation, increase capacity of team care) as well as enhanced communication skills training to facilitate conversation around goals.

Despite numerous strengths, there are limitations to this study. Due to the qualitative study design, there is limited generalizability of results to wider RA patient and clinician populations; however, themes were consistent across patient groups and clinical sites. Separate patient groups (Veterans, non-English speakers) were purposefully conducted to examine goals and goal conceptualization, however no distinct differences across patient groups were identified. In addition, the ambiguities that are inherently part of human language may contribute to inconsistencies among researchers’ interpretations during the analytic process. We attempted to mitigate this issue by having multiple coders (EH, JB, AS) review the data and resolve coding discrepancies through in-depth discussion. Future research should address ways in which goal elicitation and sharing can be incorporated into routine clinical care.

While information gathering is integral to self-management and shared decision making, the mismatch in attitudes towards the goal of knowledge between patients and clinicians may lead to suboptimal communication and lack of trust. Given that both groups viewed the RA illness experience as stressful and clinicians identified the negative impact of stress on communication, tools and time to facilitate conversation around goals may lead to greater goal concordance. This in turn may promote more high value rheumatologic care in which patient-identified health goals are achieved within the capacity and workload of individual patients [18, 19]. With tools and training to support patient goal-directed care in rheumatology, improved outcomes and reduced disparities may be achieved.

Significance and Innovations.

Patient and clinician goal alignment has been shown to improve chronic disease outcomes, but has yet to be explored in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

This qualitative study of RA patients and clinicians underscores the tension between having an explicit, shared goal and experiencing inherently different conceptualizations of how one achieves that goal.

Psychosocial stress influences patient’s illness experience which in turn informs treatment preferences in ways not shared by clinicians. Stress also impacts patient-clinician communication and decision making on goal concordance.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients and clinicians who generously participated in this study.

Funding information: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Barton’s work was supported by the NIH (grant K23-AR-064372).

Appendix 1 Focus group participant data tables

Table 1.

Patient focus group participant characteristics (language, gender)

N=19 patients

| Patient Participant | Language | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spanish | Female |

| 2 | Spanish | Female |

| 3 | English | Male |

| 4 | Spanish | Male |

| 5 | English | Female |

| 6 | English | Male |

| 7 | English | Female |

| 8 | Spanish | Female |

| 9 | English | Male |

| 10 | English | Female |

| 11 | English | Female |

| 12 | English | Female |

| 13 | English | Male |

| 14 | English | Female |

| 15 | English | Female |

| 16 | English | Female |

| 17 | Spanish | Female |

| 18 | English | Female |

| 19 | English | Female |

Table 2.

Clinician focus group participant data (career stage)

N=18 clinicians

| Clinician Participant | Career Stage |

|---|---|

| 1 | Attending |

| 2 | Attending |

| 3 | Fellow |

| 4 | Fellow |

| 5 | Attending |

| 6 | Attending |

| 7 | Fellow |

| 8 | Fellow |

| 9 | Attending |

| 10 | Attending |

| 11 | Attending |

| 12 | Fellow |

| 13 | Attending |

| 14 | Attending |

| 15 | Fellow |

| 16 | Fellow |

| 17 | Attending |

| 18 | Fellow |

Table 3.

Focus group type and number of participants per group

| Focus Group Type | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Attending Group 1 | 10 |

| Fellow Group 1 | 4 |

| Fellow Group 2 | 4 |

| English-speaking Patient Group 1 | 3 |

| English-speaking Patient Group 2 | 8 |

| Spanish-speaking Patient Group | 4 |

| Veteran Group | 4 |

| Spanish-speaker Patient semi-structured interview | 1 |

References

- 1.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dodson JA. Moving From Disease-Centered to Patient Goals-Directed Care for Patients With Multiple Chronic Conditions: Patient Value-Based Care. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(1):9–10. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuluski K, et al. A qualitative descriptive study on the alignment of care goals between older persons with multi-morbidities, their family physicians and informal caregivers. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heisler M, et al. When do patients and their physicians agree on diabetes treatment goals and strategies, and what difference does it make? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(11):893–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lafata JE, et al. Patient-reported use of collaborative goal setting and glycemic control among patients with diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):94–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen JS, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):3–15. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smolen JS, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(3):492–509. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh JA, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1–26. doi: 10.1002/art.39480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulen E, et al. Patient goals in rheumatoid arthritis care: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2016 doi: 10.1002/msc.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barton JL, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in disease activity and function among persons with rheumatoid arthritis from university-affiliated clinics. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(9):1238–46. doi: 10.1002/acr.20525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg JD, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 2013;126(12):1089–98. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton JL, et al. English language proficiency, health literacy, and trust in physician are associated with shared decision making in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(7):1290–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DL M. The Focus Group Guidebook. Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guest GMK, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radner H. Multimorbidity in rheumatic conditions. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2016;128(21–22):786–790. doi: 10.1007/s00508-016-1090-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekman I, et al. Person-centered care–ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(4):248–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Entwistle VA, Watt IS. Treating patients as persons: a capabilities approach to support delivery of person-centered care. Am J Bioeth. 2013;13(8):29–39. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.802060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson LC, et al. Effect of the Goals of Care Intervention for Advanced Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):24–31. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohlen K, et al. Overwhelmed patients: a videographic analysis of how patients with type 2 diabetes and clinicians articulate and address treatment burden during clinical encounters. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):47–9. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.May CR, et al. Rethinking the patient: using Burden of Treatment Theory to understand the changing dynamics of illness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:281. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]