Abstract

Aims

The aim of this study is to evaluate how critical patient involvement is in pharmacist‐led clinical medication reviews and in identifying the most significant clinical drug‐related problems (DRPs).

Methods

Pharmacist‐led clinical medication reviews were conducted with 161 consenting patients aged ≥75 years with at least seven prescribed medicines, living independently at home in Finland. A pharmacist, a nurse and a physician evaluated the clinical significance of the DRPs identified during the patient interview at an interprofessional case conference. It was evaluated whether the most significant clinical DRPs could also have been identified through reviewing the medication list only or the medication list and certain patient details.

Results

Altogether, the 111 most significant clinical DRPs were evaluated. Only 6% could have been identified through reviewing the medication list only, and 16% through reviewing the medication list and certain patient details. Hence, 84% of the most significant clinical DRPs could only have been identified with patient involvement. The most common DRPs were: poor therapy control (25%); nonoptimal drug (22%); intentional nonadherence (12%); and additional drug needed (11%). patient involvement was critical when identifying DRPs related to additional drug needed, unintentional nonadherence, use of over‐the‐counter medicines or dietary supplements, or contradictions in counselling.

Conclusion

Patient involvement is essential when identifying clinical DRPs. Indeed, poor therapy control, nonoptimal drug use, intentional or unintentional nonadherence might otherwise be missed.

Keywords: drug‐related problems, medication review, patient interviews, patient involvement, pharmacotherapy

What is Already Known about this Subject

Drug‐related problems are common in elderly patients who have many chronic diseases and use several drugs.

Drug‐related problems can be identified through patient interviews completed by pharmacists or other health care professionals.

Patient involvement in medication reviews may be time consuming and has been questioned.

What this Study Adds

This study shows that the majority of the most significant drug‐related problems identified through patient interviews in clinical medication reviews cannot be identified through reviewing the health centre medication lists only or through reviewing the health centre medication lists and certain patient details.

Patient involvement and patient interviews are essential in identifying DRPs.

Introduction

A substantial proportion (27–73%) of drug‐related problems (DRPs) identified in medication reviews is discovered by interviewing the patient 1. Furthermore, a high proportion of these DRPs has also been found to be clinically significant 1, 2, 3. However, there is little research evaluating how important patient involvement is in identifying most significant clinical DRPs in clinical medication reviews (CMRs).

Inappropriate drug use and prescribing have been shown to be associated with mortality, morbidity, hospitalisation and healthcare costs 4, 5, 6, 7. Collaborative pharmacist‐led medication review procedures have been developed in many countries to improve the quality, safety and appropriate use of medicines through detecting DRPs and recommending interventions 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. While it has not been shown that CMRs would prevent death and hospital admissions 14, 15, 16, they might reduce emergency department visits in hospitalised patients 14. There is also evidence that the number of DRPs per patient can be decreased and medication knowledge and adherence of patients can be improved through CMRs, and hence it is possible to improve the quality of pharmacotherapy especially in older people 2, 3, 8, 15, 17, 18, 19.

CMRs should always include access to patient information, such as clinical conditions and laboratory test results, and patient involvement (e.g. home‐based interview) 11, 20, 21. However, patient interviews are time consuming and they increase the costs of the medication review process 1, 2, 3. Consequently, the involvement of patients in CMRs has been questioned 1. Is there a need to interview the patient, or can medication reviews be conducted reliably without patient involvement? The aim of this study was to examine how critical patient involvement is in pharmacist‐led CMRs and in identifying the most significant clinical DRPs.

Methods

Context of the study and study design

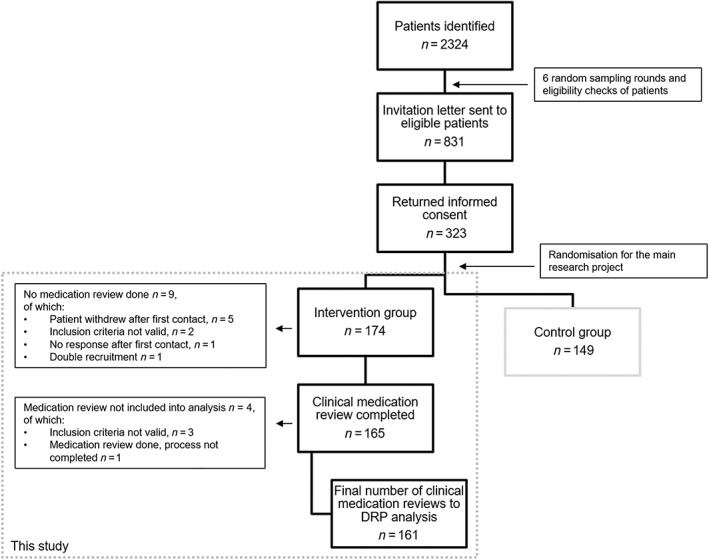

This study was a part of a longitudinal randomised controlled trial (Care Plan 2100 research project) in primary care setting in Tornio, Finland, with 22 000 inhabitants. Consenting patients were enrolled to the study between October 2014 and May 2016. The research project was conducted in collaboration with Tornio Health Centre (GPs, nurses and a pharmacist; setting and intervention providers), Alatornio Community Pharmacy (a pharmacist; intervention provider) and Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Helsinki (three pharmacists; intervention providers and researchers). The study reported here focusses on the baseline of the Care Plan 2100 research project (Figure 1). The study protocol was approved by the regional North Ostrobothnia Hospital District ethics committee (32/2014).

Figure 1.

Patient flow and the clinical medication reviews included in the analysis

Identifying and recruiting patients

All outpatients aged ≥75 years were identified with the help of the Tornio health centre patient data management system databases (Pegasos, CGI) and listed to Microsoft Excel (2013; Figure 2, Phase 1). Patients were approached and recruited in random in several rounds. The number of patients needed for each recruitment round was determined and candidates for recruitment were selected in random using Microsoft Excel. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥75 years; home‐dwelling; and at least seven prescribed medicines, dietary supplements or lotions/creams. Exclusion criteria were: living in a care home; having been admitted to a hospital ward; having been appointed a guardian of interests; not a resident of Finland (Tornio is on the border between Finland and Sweden); not a resident in Tornio; or a geriatrician had completed a clinical medication review in the last 2 years. If the patients met the inclusion criteria at the time of the recruitment, they were eligible to participate. The process was repeated until the number of patients needed for the randomized‐control trial (n = 300) was completed. Participants for the Care Plan 2100 research project were aged and multimorbid (seven or more drugs presumed to indicate multimorbidity) yet home‐dwelling so that the effects of supporting their health could potentially lead to differences between intervention and control groups (n = 150 in both), for example, in the use of health care services.

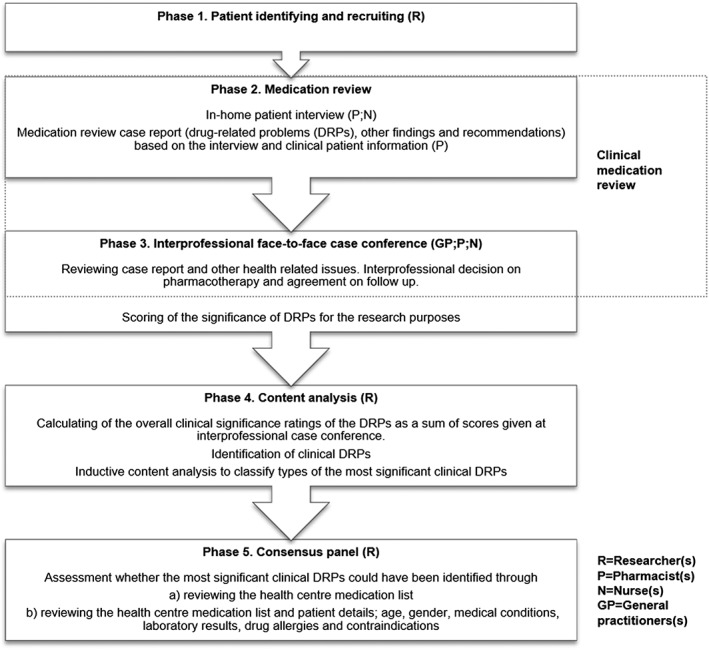

Figure 2.

The study process

Patient recruitment information included a cover letter, information on the study, informed consent form and a prepaid self‐addressed return envelope. Patients who returned the signed consent form were divided in random into two groups by an envelope method, in which the uppermost remaining envelope including the designation of the group was picked from a box, opened and the patient was placed in either the intervention or control group.

Medication review process (intervention)

Medication reviews were completed following the national collaborative CMR procedure 11. The intervention comprised a pharmacist‐led clinical medication review with at‐home patient interview and an interprofessional (a GP, a pharmacist and a nurse) case conference meeting (Figure 2, Phases 2 and 3). The CMRs were performed by four pharmacists (two with BSc, one with MSc, one with PhD) all accredited to complete medication reviews.

A structured interview form was used to lead the informal interview and data collection 11. At the beginning of the interview the pharmacist compared the health centre medication list to the patient's actual use of prescription and over‐the‐counter (OTC) drugs and dietary supplements. The interview covered themes of background details (e.g. dosing, and drug allergies), therapy control, experienced DRPs, potential adverse drug reactions and health history (e.g. smoking, alcohol use, exercise and nutrition). Furthermore, the pharmacists were to recognise any drug administration problems such as inappropriate timing of administration, poor storage conditions and expired medications, and also discuss the patient's experiences and alleviate any concerns with drugs they might have had. During the interviews, patients were encouraged to mention any health‐ and medicine‐related issues that were important to them and any health‐related goals towards which they wanted to work. The pharmacist documented the interview using the form and wrote notes about any other drug‐related issues and possible DRPs that were discussed in addition to the topics in interview form. Depending on their preference, the pharmacists could use the health centre medication lists and clinical records before or during the patient interview. However, after the interview, the interviewing or another pharmacist performed the actual CMR (based on the evaluation of the interview notes, laboratory results, medication lists and other clinical records). The reviewing pharmacist wrote a CMR report that included patient characteristics, DRPs, other findings and recommendations to be presented at an interprofessional case conference.

Additionally, a nurse visited and interviewed the patients about health‐related issues. At the start, there were two separate visits, but to save time and resources, at most patient interviews, both a pharmacist and the nurse were present at the same time. The nurse composed a health report based on the interview and the primary care clinical records to also be presented at the interprofessional case conference. At the interprofessional case conference, a GP, the nurse and a pharmacist reviewed the CMR report and the health report, discussed the DRPs and health‐related issues, made decisions based on the pharmacist's and nurse's recommendations and created a care plan for each patient.

Outcomes measures

At the end of each interprofessional case conference the pharmacist, the nurse and the GP evaluated individually the clinical significance of the identified DRPs (Figure 2, Phase 3). A five‐point Likert scale was used (1 = no significance, 2 = slightly significant, 3 = moderately significant, 4 = significant, 5 = very significant), and the most significant clinical DRPs were identified by calculating the sum of the clinical significance ratings for each DRP (Figure 2, Phase 4). DRPs with a significance rating sum between 12 and 15 were viewed as highly significant since the mean value of those was four (significant) or more. These problems were then classified as unrelated to medicines/technical problems or clinical DRPs, the latter of which were grouped into two categories: identified through patient interview; and identified through patient details in patient data system. The clinical DRPs were included in the analysis.

The clinical DRPs were first classified using the PCNE Classification v 7.0 (Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe 2016) 22. However, the classification criteria were modified so that DRPs identified during patient interview could be classified in detail. The researcher (H. Kari) performed inductive content analysis of the CMR case reports and classified the DRPs 23.

Two researchers (H. Kari, H. Kortejärvi) evaluated independently if the most significant clinical DRPs identified during the patient interview could also have been identified by reviewing the health centre medication list only, or by reviewing the medication list and certain patient details (age, sex, medical conditions, laboratory results, drug allergies and contraindications; Figure 2, Phase 5). After the independent review, the researchers had a consensus discussion.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the participants (age, sex, glomerular filtration rate, smoking, diseases, medications) are shown as frequencies for categorical variables and means with standard deviations and ranges for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 23.0) and Microsoft Excel (2016). The quality of the data entries was checked before starting the analyses.

Results

Patient flow and characteristics

A total of 2324 patients were identified in the patient data management system and 831 recruitment letters were sent to eligible patients who met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of these, 323 patients (38.9%) returned the recruitment letter, and of these, 174 patients were randomized to the intervention group. Eventually, 161 patients' clinical medication reviews were included into this study. Two patients had fewer than seven prescribed drugs in the patient data management system when the updated medication list for the interview was printed. However, these two had had seven prescribed drugs at the time of the recruitment and, thus, were included in this study.

The mean age of the patients (n = 161) was 81 years and 62% were women (Table 1). The prevalence of cardiovascular system diseases was 91% and endocrine system diseases 39%. One fifth of the patients had or had had a malignant disease. According to the patient data system patients used on average 12 prescribed drugs/dietary supplements/lotions, of which 10 were prescribed to be taken regularly and two taken as required. However, during the interviews, patients reported that medication lists were not up to date and there were on average three drugs that patients did not use and one regular drug that was not listed. In addition, there was also on average one drug that patients used with deviating dosages compared with those on medication lists.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in this study derived from health centre patient registers (n = 161)

| Variable | All | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 62 (38.5) | 99 (61.5) | |

| Age (years), Mean ± SD (range) | 81.0 ± 4.5 (75–98) | 81.2 ± 4.4 (75–96) | 80.9 ± 4.5 (75–98) |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml min –1 ) a , Mean ± SD (range) n = 156 | 66.4 ± 14.5 (29–98) | 66.8 ± 14.3 (31–85) n = 61 | 66.1 ± 14.6 (29–98) n = 95 |

| Active smokers a , b , n (%) n = 141 | 10 (7.1) | 6 (11.3) n = 53 | 4 (4.5) n = 88 |

| Most common diagnosed diseases, n (%) | |||

| Cardiovascular system (hypertension, heart failure, coronary heart disease, arrhythmia, hypercholesterolaemia) | 146 (90.7) | 58 (93.5) | 88 (88.9) |

| Endocrine system (diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose, hypothyroidism) | 63 (39.1) | 24 (38.7) | 39 (39.4) |

| Malignant disease | 32 (19.9) | 17 (27.4) | 15 (15.2) |

| Respiratory system (asthma, COPD) | 29 (18.0) | 8 (12.9) | 21 (21.2) |

| Central nervous system (Alzheimer disease, diagnosed memory problems, depression) | 14 (8.7) | 7 (11.3) | 7 (7.1) |

| Number of medicines on the medication list , Mean ± SD (range) | |||

| Number of drugs/dietary supplements/lotions | 12.1 ± 4.9 (6–29) | 11.9 ± 5.0 (6–28) | 12.2 ± 4.8 (6–29) |

| Regular drugs | 9.7 ± 3.8 (3–24) | 9.7 ± 3.9 (4–24) | 9.7 ± 3.8 (3–24) |

| Drugs taken as required | 2.4 ± 2.4 (0–12) | 2.2 ± 2.5 (0–12) | 2.5 ± 2.4 (0–11) |

| Dietary supplements | 0.1 ± 0.3 (0–1) | 0.1 ± 0.3 (0–1) | 0.1 ± 0.3 (0–1) |

| Lotions or creams (nonmedical) | 0.2 ± 0.5 (0–3) | 0.2 ± 0.5 (0–3) | 0.2 ± 0.5 (0–3) |

| Same drug listed two or more times | 0.8 ± 1.1 (0–6) | 0.7 ± 0.9 (0–4) | 0.9 ± 1.2 (0–6) |

| Number of discrepancies b , Mean ± SD (range) | |||

| Drugs not in use b | 3.0 ± 2.5 (0–12) | 2.9 ± 2.7 (0–12) | 3.0 ± 2.5 (0–11) |

| Drugs used with different dosage b | 0.8 ± 1.0 (0–5) | 0.7 ± 0.9 (0–3) | 0.9 ± 1.1 (0–5) |

| Regular drugs not listed b | 0.8 ± 1.1 (0–6) | 0.8 ± 1.1 (0–5) | 0.8 ± 1.1 (0–6) |

Information not available for all patients.

Information through patient interview.

SD, standard deviation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

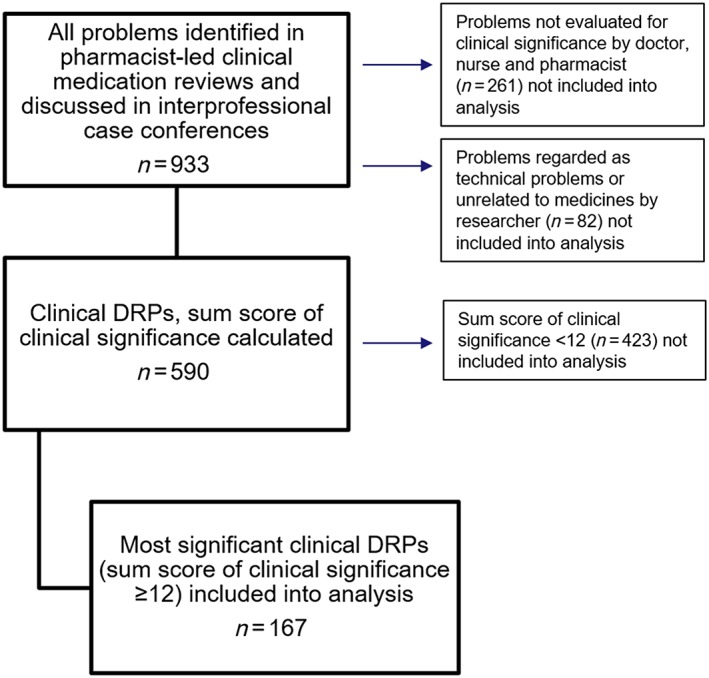

Types of the most significant clinical DRPs

Altogether, 167 (28.3%) of 590 clinical DRPs received a significance rating sum ≥12 that was significant or highly significant (Figure 3) for the 161 patients. Two‐thirds (66.5%, n = 111) of the most significant clinical DRPs were identified through the patient interviews, and 33.5% (n = 56) were identified through patient information in patient data system. Eleven main types of DRPs were identified using the inductive content analysis. The most frequently identified types of the most significant clinical DRPs through the patient interviews were (Table 2, n = 111): poor therapy control (28/111, 25%); nonoptimal drug (24/111, 22%); intentional nonadherence (13/111, 12%); additional drug needed (12/111, 11%); unintentional nonadherence (9/111, 8%); and use of OTC medicines or dietary supplements (7/111, 6%). The most significant clinical DRPs identified through patient information in the patient data system were: nonoptimal drug (20/56, 36%); need for monitoring (13/56, 23%); indication for use of medication is unclear (10/56, 18%); additional drug needed (9/56, 16%); poor therapy control (3/56, 5%); and intentional nonadherence (1/56, 2%). DRPs identified during the patient interviews were included in the further analysis.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of all drug‐related problems (DRPs; n = 933) identified by the pharmacists, the clinical DRPs with the clinical significance rating (n = 590) and the most significant clinical DRPs with the clinical significance rating sum ≥12 (n = 167)

Table 2.

The most significant clinical drug‐related problems (DRPs) identified through patient interview (n = 111) divided into 11 groups

| Eleven main types of DRP | DRPs N | DRP could be identified through reviewing medication list only, n/N | DRP could be identified through reviewing medication list and patient detailsa , b, n/N | DRP could be identified only through patient interview, n/N | Specification of DRPs that could be identified only through patient interview (n = 93) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor therapy control | 28 | 0 | 4/28 | 24/28 | Blood pressure not controlled (n = 12), pain not controlled (n = 4), arrhythmia (n = 3), asthma not controlled (n = 2), chest pain (n = 2), epilepsy not controlled (n = 1) |

| Nonoptimal drug | 24 | 7/24 | 7/24 | 17/24 | (Possible) Adverse drug reaction (n = 8): Bleeding (warfarin, clopidogrel + ASA, systemic ketoprofen, n = 3), dizziness (felodipine, losartan + spironolactone + nebivolol, n = 2), drowsiness (amitriptyline, oxycodone/naloxone, n = 2), arrhythmia (denosumab, n = 1) |

| (Possible) Lack of effect of pharmacotherapy (n = 3): fesoterodine, oxybutynin, mirabegron | |||||

| Not recommendable for older people for regular use (n = 6): zopiclone (n = 4), nitrazepam (n = 1), ibuprofen (n = 1) | |||||

| Intentional nonadherence | 13 | 0 | 3/13 | 10/13 | Patient does not follow the instructions given (n = 8): Statin (n = 3), heart and blood pressure medicine (metoprolol, losartan, amlodipin + enalapril + hydrochlorothiazide, n = 3), metformin (n = 1), calcium + vitamin D (n = 1) |

| Patient does not take the prescribed drug (n = 2): statin (n = 2) | |||||

| Additional drug needed | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12/12 | Need for additional drug (n = 12): vitamin D (n = 4), sleeping medicine (n = 2), pain medicine (n = 2), medical cream (n = 2), laxative (n = 1), urinary tract medicine (n = 1) |

| Unintentional nonadherence | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9/9 | Drug used for wrong purpose (n = 4): ibuprofen for COPD symptoms, Pantoprazole for oral candidiasis, ASA (100 mg dose) for trigeminal neuralgia, ASA (100 mg dose) for acute pain |

| Inappropriate timing of administration (n = 2): furosemide administered in the late afternoon/evening (n = 2) | |||||

| Patient administers the drug in a wrong way (n = 2): improper asthma inhaler device use (n = 2) | |||||

| Patient has misunderstood the instructions (n = 1): patient did not know that budesonide–formoterol turbuhaler should be used regularly | |||||

| Use of over‐the‐counter medicines or dietary supplements | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7/7 | Inappropriate use of dietary supplements (n = 3): consumption of high doses of selenium, consumption of high doses of vitamin D, patient with stomach problems uses shark cartilage and green‐lipped mussel product |

| Use of several systemic NSAIDs (n = 2): ASA + ibuprofen, naproxen + ibuprofen | |||||

| Interaction with warfarin (n = 2): ASA (300 mg) + warfarin, omega‐3 fatty acid + warfarin | |||||

| Contradictions in counselling | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4/4 | Unclear dosing instructions (n = 2): statin (n = 2) |

| drug indication unclear to the patient (n = 1): continuing use of chloramphenicol eye ointment | |||||

| Need for use unclear to the patient (n = 1): galantamine | |||||

| Medication costs | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4/4 | High medication costs and no basic/special reimbursement by The Social Insurance Institution (n = 4): asthma medicine (n = 2), laxative (n = 1), pain medicine (n = 1) |

| Indication for use of medication is unclear | 3 | 0 | 1/3 | 2/3 | Indication for use of medication is unclear (n = 2): buprenorphine for restless legs syndrome, calcium/vitamin D for hypoparathyroidism. |

| Need for monitoring | 3 | 0 | 2/3 | 1/3 | Need for monitoring (n = 1): patient asks for blood sugar monitoring |

| Others | 4 | 0 | 1/4 | 3/4 | Due to decreased health condition patient cannot drive a car anymore and has difficulties to go to INR monitoring tests (n = 1) |

| Patient and his wife need pharmacist counselling on timing of administration and dosing intervals (n = 1) | |||||

| Patient has complex health problems that are related to drugs and other health issues (n = 1) | |||||

| All, n/N | 111 | 7/111 | 18/111 | 93/111 | |

| % | 6 | 16 | 84 |

Patient details; age, sex, medical conditions, laboratory results, drug allergies and contraindications.

Includes DRPs that have been identified through reviewing medication list only.

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; INR, international normalized ratio

Patient involvement in identifying the most significant clinical DRPs

After the independent evaluation of the 111 DRPs identified during the patient interviews, the two researchers had reached agreement on the 98 DRPs whether they could or could not have been identified without the interview. The researchers discussed the remaining 13 DRPs and reached consensus. They agreed that only 6% (n = 7) of the most significant clinical DRPs identified during the patient interview (n = 111) could also have been identified by using the medication list only and 16% (n = 18) could also have been identified by using the medication list and certain patient details (Table 2). Hence, 84% (n = 93) of the most significant clinical DRPs identified in patient interview could be identified through patient involvement only.

Patient involvement was critical when identifying most significant clinical DRPs related to additional drug needed, unintentional nonadherence, use of OTC medicines or dietary supplements, contradictions in counselling, and medication costs. Only some nonoptimal drug DRPs (7/24) could have been identified by using the medication list only. By combining the information on the medication lists and the patient details, few poor therapy control (4/28), intentional nonadherence (3/13), need for monitoring (2/3), indication for use of medication is unclear (1/3), and other (1/4) DRPs could have been identified without patient involvement.

Patients showed concern or even fear related to medicines use in 13 out of 111 DRPs (12%) identified through patient interviews. This was related to poor therapy control (n = 7), intentional nonadherence (n = 3), nonoptimal drug (n = 1), medication costs (n = 1) and others (n = 1).

Discussion

Main findings

The results of this study endorse that patient involvement is an integral part of clinical medication reviews. Many clinical DRPs are identified through patient interviews, which is comparable to findings of previous studies 1, 2, 3. Kwint et al. also found that DRPs assigned a high priority were more likely to be identified during patient interviews than from medication and clinical records in primary care 3. Furthermore, our study showed that there are types of DRPs that cannot be identified through reviewing medication list, or medication list and patient details. Patient interviews are essential when identifying DRPs, for example, related to poorly controlled therapy, possible adverse drug reaction, unintentional use of the drug for wrong purpose, inappropriate use of OTC medicines or dietary supplements, or contradictions in counselling. Additionally, medication lists and patient details cannot generally be used to discover if the patient intentionally does not take the prescribed medicine or does not follow the instructions given.

Role of the health care professionals

The majority of the most significant clinical DRPs that could be identified only through patient interviews were related to poorly controlled therapy. Evidently, drug therapies are started, but effectiveness of the therapies, possible adverse drug reactions, proper drug use and patients' compliance to drugs are not routinely controlled or not even discussed with the patients. For example, our findings related to nonadherence of use of cholesterol medicines are similar to recent results of Silvennoinen et al., which showed that most of the nonpersistent statin users had discontinued the medication without discussing it with a physician 24, and to findings of Kwint et al. 3 and Krska et al. 19 that compliance issues and adverse effects were frequently identified through patient interviews. Along with patient involvement, it is important to clarify health care professionals' roles and responsibilities in monitoring and controlling drug use to ensure effective drug therapy and to avoid, reveal and solve DRPs in primary care settings. Interprofessional team work, pharmacist‐led clinical medication reviews and patient‐centred care‐coordination including patient participation should be used to gain information about relevant DRPs and to improve drug therapy control. This could result in better drug therapy outcomes, fewer DRPs and better quality of life of the patient. However, it is also important to study cost‐effectiveness of this kind of care as resources in health care are scarce and must be allocated efficiently.

In Finland, prescriptions can be (since 1 January 2017) valid for 2 years, after which they can be renewed, which should result in community pharmacists playing even more integral role in identifying and solving DRPs. Partnerships with patients might increase at community pharmacies. Indeed, a great proportion of the most significant clinical DRPs identified through patient interviews as a part of CMRs in our study, could have also been identified at community pharmacies by medication counselling and interviewing the patient, or, obviously, during GP appointments. These DRPs include, for example, poor therapy control and nonoptimal drugs for the patient that were the most common clinical DRPs identified through patient interviews in our study.

Patients' concerns or even fear related to medicines use was present in 12% of the DRPs identified through patient involvement. Face‐to‐face contact with patients and open discussions are essential in developing a trusting relationship with health care professionals, which is the basis for counselling and revealing possible concerns and fears 11. Furthermore, all health care professionals should attend to giving clear and nonconflicting drug information to patient throughout the health care system.

Patient involvement and empowerment

Our study showed that CMR including patient interview is a tool for revealing DRPs, for example related to poor therapy control and nonoptimal drugs. Moreover, patient interview and involvement could also be a great opportunity for pharmacists to empower patients in appropriate drug use and self‐management, and furthermore to identify possible drug‐related concerns or fears. It has been widely suggested that the focus on chronic and multimorbid patients' care should progress from monitoring and supporting medication‐taking and health‐related behaviour (adherence) to concordance and further to patient empowerment 25, 26, 27, 28. In health promotion, empowerment is a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health 29. There is, for example, evidence that pharmacists' support and reinforcement based on empowerment contribute to the patients' sustained motivation to diabetes care 30.

Medication nonadherence among patients with chronic medical conditions is common 31, 32, 33. However, those DRPs classified, for example, to intentional or unintentional nonadherence, patients receiving conflicting counselling, or use of OTC medicines or dietary supplements in our study could also be consequence of limited health literacy skills that are common in older people 34, 35, 36. Health literacy represents cognitive and psychosocial skills, such as memory, reasoning, verbal ability, reading, numeracy, critical thinking and self‐efficacy, which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health 29, 37. Patients with low health literacy skills could be those who especially benefit of the pharmacists' home visits and CMRs. Active listening, asking appropriate questions, tailored patient information, and use of several channels of information should be used to support these patients' medication adherence and health empowerment. Nevertheless, it must be noticed that not all people and different disease groups of patients need same medicines information and want to be that much involved in health‐related decision making 38. To conclude, patients should be viewed as individuals when providing medicines‐ and health‐related information and empowerment. To improve patient‐centredness and identifying of DPRs, clinical interviewing techniques of pharmacists, GPs and other health care professionals, and patient empowerment skills should be improved, and they should be encouraged to identify patients with limited health literacy skills 39, 40. Patients might also benefit having their own trusted personal GP, nurse and pharmacist who know their history and manage their health care.

Future opportunities

This study evaluated if the most significant clinical DRPs identified in patient interviews could have been identified through reviewing the health centre medication list only or through reviewing the health centre medication list and certain patient details. Clinical reports, which could have provided some extra information for us, were excluded. In the future, the use of electronic decision support tools will grow exponentially in health care, which can, together with patient involvement and patient‐centred care, improve patient safety and make medication review processes more straightforward. However, to be able to make appropriate decisions based on these findings, it is essential that the information in the patient data systems is correct, up‐to‐date, documented in a structured way and accessible to all health care professionals who participate in patient care. Combining the use of modern information technologies, electronic decision support, data analysing tools and individual patient involvement should be considered to identify clinically significant DRPs. Furthermore, it is important to study cost‐effectiveness and benefits of the CMRs and patient care models from the perspective of patients, health care professionals and systems. Eventually, rational use of medicines will yield benefits to both patients and society.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths are: the study was performed with real patients; it was conducted by pharmacists accredited to complete medication reviews; and it included interprofessional case conferences and evaluation of the significance of the DRPs. The limitations are: the inclusion criteria were strictly restricted to a selected patient group in one town for the research purposes, which may decrease the generalisability of the results. Since the patients in this project were ≥75‐year‐old outpatients and voluntary participants, these findings can be generalised only to aged home‐dwelling patients. However, since we assume that the participating patients might have an interest in their health and medications, there could be even more DRPs among the nonparticipants.

Conclusion and future studies

Patient involvement is essential in identifying the most significant clinical DRPs in CMRs. Indeed, poor therapy control, nonoptimal drug use, intentional or unintentional nonadherence might otherwise be missed. Along with identifying DRPs, CMR should be taken as an opportunity to support individual health‐related patient empowerment. Future research should focus on analysing procedures that strengthen patient involvement in their own care and partnership with the health care professionals. Furthermore, future research should evaluate the combination of use of electronic tools and patient interviewing techniques in finding and solving significant DRPs.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare

The study was conducted in collaboration with Tornio Health Centre, Alatornio Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy University of Helsinki and Duodecim Medical Publications Ltd, and it was supported by funding from The Association of Finnish Pharmacies (AFP) and The Foundation of Vappu and Oskari Yli‐Perttula. The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

The authors would like to thank Jukka Ronkainen MD, PhD for his expertise and support, Timo Kilpijärvi RN, Arja Salmela BSc (Pharm) and Virpi Rahko BSc (Pharm) for their contribution in the patient interviews, and the GPs for their contribution in the interprofessional case conferences.

Kari, H. , Kortejärvi, H. , Airaksinen, M. , and Laaksonen, R. (2018) Patient involvement is essential in identifying drug‐related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 2048–2058. 10.1111/bcp.13640.

References

- 1. Willeboordse F, Hugtenburg JG, Schellevis FG, Elders PJ. Patient participation in medication reviews is desirable but not evidence‐based: a systematic literature review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 78: 1201–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Interview of patients by pharmacists contributes significantly to the identification of drug‐related problems (DRPs). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006; 15: 667–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kwint HF, Faber A, Gussekloo J, Bouvy ML. The contribution of patient interviews to the identification of drug‐related problems in home medication review. J Clin Pharm Ther 2012; 37: 674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ebbesen J, Buajordet I, Erikssen J, Brors O, Hilberg T, Svaar H, et al Drug‐related deaths in a department of internal medicine. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 2317–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bakken MS, Ranhoff AH, Engeland A, Ruths S. Inappropriate prescribing for older people admitted to an intermediate‐care nursing home unit and hospital wards. Scand J Prim Health Care 2012; 30: 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jano E, Aparasu RR. Healthcare outcomes associated with Beers' criteria: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 2007; 41: 438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saastamoinen LK, Verho J. Register‐based indicators for potentially inappropriate medication in high‐cost patients with excessive polypharmacy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015; 24: 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blenkinsopp A, Bond C, Raynor DK. Medication reviews. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 74: 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bulajeva A, Labberton L, Leikola S, Pohjanoksa‐Mäntylä M, Geurts MME, de Gier JJ, et al Medication review practices in European countries. Res Social Adm Pharm 2014; 10: 731–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jokanovic N, Tan EC, van den Bosch D, Kirkpatrick CM, Dooley MJ, Bell JS. Clinical medication review in Australia: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm 2016; 12: 384–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leikola S, Tuomainen L, Peura S, Laurikainen A, Lyles A, Savela E, et al Comprehensive medication review: development of a collaborative procedure. Int J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 34: 510–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leikola S, Virolainen J, Tuomainen L, Tuominen R, Airaksinen M. Comprehensive medication reviews for elderly patients: findings and recommendations to physicians. J Am Pharm Assoc 2012; 52: 630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe . PCNE working group on medication review 2016. Available at http://www.pcne.org/working-groups/1/medication-review (last accessed 31 January 2018).

- 14. Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 2: CD008986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holland R, Desborough J, Goodyer L, Hall S, Wright D, Loke YK. Does pharmacist‐led medication review help to reduce hospital admissions and deaths in older people? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 65: 303–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Royal S, Smeaton L, Avery AJ, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A. Interventions in primary care to reduce medication related adverse events and hospital admissions: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Qual Saf Health Care 2006; 15: 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vinks T, Egberts T, de Lange T, de Koning F. Pharmacist‐based medication review reduces potential drug‐related problems in the elderly: the SMOG controlled trial. Drugs Aging 2009; 26: 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Milos V, Rekman E, Bondesson Å, Eriksson T, Jakobsson U, Westerlund T, et al Improving the quality of pharmacotherapy in elderly primary care patients through medication reviews: a randomised controlled study. Drugs Aging 2013; 30: 235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, Jamieson D, Hansford D, Duffus PR, et al Pharmacist‐led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing 2001; 30: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clyne W, Blenkinsopp A, Seal R. A guide to medication review 2008. NHS, national prescribing Centre. 2008.

- 21. Jyrkkä A, Kaitala S, Aarnio H, Airaksinen M, Toivo T. Clinical interview as part of medication reviews and support for medication self‐management (summary in English). Dosis 2017; 33: 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe , The PCNE classification V 7.0, 2016.

- 23. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silvennoinen R, Turunen JH, Kovanen PT, Syvänne M, Tikkanen MJ. Attitudes and actions: a survey to assess statin use among Finnish patients with increased risk for cardiovascular events. J Clin Lipidol 2017; 11: 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grunbach K. Patient self‐management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA 2002; 288: 2469–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bell JS, Airaksinen MS, Lyles A, Chen TF, Aslani P. Concordance is not synonymous with compliance or adherence. Br J Pharmacol 2007; 64: 710–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Routasalo P, Airaksinen M, Mäntyranta T, Pitkälä K. Potilaan omahoidon tukeminen (in Finnish). Duodecim 2009; 125: 2351–2359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pulvirenti M, McMillan J, Lawn S. Empowerment, patient centred care and self‐management. Health Expect 2011; 17: 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot Int 1998; 13: 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parkkamäki S. The empowerment based support of type 2 diabetes self‐management at the community pharmacy. Doctoral thesis (Abstract in English), University of Helsinki, Helsinki, 2013.

- 31. Briesacher B, Andrade S, Fouayzi H, Arnold Chan K. Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy 2008; 28: 437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kekäle M, Talvensaari K, Koskenvesa P, Porkka K, Airaksinen M. Chronic myeloid leukemia patients' adherence to peroral tyrosine kinase inhibitors compared with adherence as estimated by their physicians. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014; 8: 1619–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta‐analysis on 376 162 patients. Am J Med 2012; 125: 882–887. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Health literacy in Canada: a healthy understanding 2008 (Ottawa: 2008).

- 35. Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of America's adults: results from the 2003 National Assessment of adult literacy (NCES 2006–483) Washington, DC: National Center for education statistics, 2006.

- 36. Sorensen K, Pelikan JM, Röthlin F, Ganahl K, Slonska Z, Doyle G, et al HLS‐EU consortium. Health literacy in Europe: comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS‐EU). Eur J Public Health 2015; 25: 1053–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wolf M, Wilson E, Rapp D, Waite K, Bocchini M, Davis T, et al Literacy and learning in healthcare. Pediatrics 2009; S275–S281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duggan C, Bates I. Medicine information needs of patients: the relationships between information needs, diagnosis and disease. Qual Saf Health Care 2008; 17: 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maatouk‐Bürmann B, Ringel N, Spang J, Weiss C, Möltner A, Riemann U, et al Improving patient‐centered communication: results of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2016; 99: 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wallace L, Rogers E, Roskos S, Holiday D, Weiss B. BRIEF REPORT: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21: 874–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]