Abstract

Aims

The aims of this systematic review were to: (1) critically appraise, synthesize and present the available evidence on the views and experiences of stakeholders on pharmacist prescribing and; (2) present the perceived facilitators and barriers for its global implementation.

Methods

Medline, CINAHL, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, PsychArticles and Google Scholar databases were searched. Study selection, quality assessment and data extraction were conducted independently by two reviewers. A narrative approach to data synthesis was undertaken due to heterogeneity, the nature of study types and outcome measures.

Results

Sixty‐five studies were identified, mostly from the UK (n = 34), followed by Australia (n = 13), Canada (n = 6) and USA (n = 5). Twenty‐seven studies reported pharmacists' perspectives, with fewer studies focusing on patients' (n = 12), doctors' (n = 6), the general public's (n = 4), nurses' (n = 1), policymakers' (n = 1) and multiple stakeholders' (n = 14) perspectives. Most reported positive experiences and views, regardless of stage of implementation. The main benefits described were: ease of patient access to healthcare services, improved patient outcomes, better use of pharmacists' skills and knowledge, improved pharmacist job satisfaction, and reduced physician workload. Any lack of support for pharmacist prescribing was largely in relation to: accountability for prescribing, limited pharmacist diagnosis skills, lack of access to patient clinical records, and issues concerning organizational and financial support.

Conclusion

There is an accumulation of global evidence of the positive views and experiences of diverse stakeholder groups and their perceptions of facilitators and barriers to pharmacist prescribing. There are, however, organizational issues to be tackled which may otherwise impede the implementation and sustainability of pharmacist prescribing.

Keywords: clinical pharmacy, prescribing, systematic review

What is Already Known about the Subject

Many countries around the world are implementing legislation, policies and practices relating to pharmacist prescribing.

Systematic reviews have documented some evidence of effectiveness and safety of nonmedical prescribing.

What this Study Adds

Synthesis of data from a large number of studies in many countries from the perspectives of diverse groups of stakeholders provides further evidence of the positive views and experiences around pharmacist prescribing.

There are organizational issues of role recognition, access to patient clinical information and financial support that could impede the implementation and sustainability of pharmacist prescribing.

Introduction

While prescribing has traditionally been restricted to medical practitioners (doctors and dentists), the rapid advancements in healthcare policies and practices have led to the introduction of models of nonmedical prescribing in several countries, with others exploring its potential 1, 2. Nonmedical prescribing is most developed in the UK, with legislative changes enabling the implementation of supplementary prescribing (SP) in 2003 and independent prescribing (IP) in 2006, as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Supplementary prescribing | Independent prescribing | |

|---|---|---|

| Year of introduction in the UK | 2003 | 2006 |

| Definition | “A voluntary partnership between an independent prescriber (doctor or dentist) and a supplementary prescriber to implement an agreed patient‐specific CMP with the patient's agreement” 5 | “The prescribing by a practitioner (e.g. doctor, dentist, nurse, pharmacist) responsible and accountable for the assessment of patients with undiagnosed or diagnosed conditions and for decisions about the clinical management required, including prescribing” 6 |

| Eligible health professionals | Dieticians, nurses, optometrists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, podiatrists, radiographers | Nurses, optometrists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, podiatrists, therapeutic radiographers |

| Clinical conditions managed | Any, within their clinical competence | Any, within their clinical competence |

| Diagnosis responsibilities | A doctor (or dentist) must diagnose the condition before prescribing can commence | The independent prescriber can assess and manage patients with diagnosed or undiagnosed conditions |

| Need for a CMP | A written or electronic patient‐specific CMP must be in place before prescribing can commence | No need for a CMP |

| Need for formal agreement | The CMP must be agreed with the doctor (or dentist) and patient before prescribing can commence | No need for any formal agreement |

| Drugs prescribed | Any, within their clinical competence | Any licensed medicines within their clinical competence. Nurse‐ and pharmacist‐independent prescribers in particular can prescribe unlicensed medicines and controlled drugs |

CMP, clinical management plan

Implementation is most advanced in Scotland, and particularly for pharmacists, where approximately 40% of pharmacists in 2017 were either prescribers registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council or undertaking an approved training programme 7. Developments in Scotland are supported by the policy driven approach of the Scottish Government, articulated in 2013 with the publication of Prescription for Excellence: a vision and action plan for the right pharmaceutical care through integrated partnerships and innovation 8. This outlined the goal that “all patients, regardless of their age and setting of care, receive high quality pharmaceutical care from clinical pharmacist independent prescribers” 8. The aspiration is that all patient‐facing pharmacists will be clinical pharmacist independent prescribers by 2023. This commitment to developing the clinical prescribing role of pharmacists in all practice settings was reaffirmed in 2017 with publication by the government of Achieving Excellence in Pharmaceutical Care 7. Details of other models of pharmacist prescribing which have been implemented in the USA, Canada and New Zealand are given in Table 2, highlighting the diverse scope of prescribing rights.

Table 2.

Summary of pharmacist prescribing models globally

| Country | Prescribing model | Description |

|---|---|---|

| USA | CDTM |

Defined by the American College of Clinical Pharmacy as “a collaborative practice agreement between one or more physicians and pharmacists wherein qualified pharmacists working within the context of a defined protocol are permitted to assume professional responsibility for performing patient assessments; ordering drug therapy‐related laboratory tests; administering drugs; and selecting, initiating, monitoring, continuing, and adjusting drug regimens” 9, 10. According to the Centers for Disease Control, in 2012, the majority of states allow CDTM for health conditions as specified in a written provider protocol in any setting (Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming), some limit it to certain health settings (New Hampshire, New York, Nevada, North Dakota, Texas, West Virginia) while others authorize extremely limited collaborative practice for pharmacists under protocol such as immunizations and emergency contraception regardless of setting (Delaware, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Wisconsin) 10. |

| Canada | The types and scope of pharmacist prescribing practice is variable according to province |

Legislations in Canada now allow pharmacists to prescribe within their area of competence and with sufficient clinical knowledge of the patient. The prescribing practice differ from one province to another. Pharmacists with additional training are able to prescribe any schedule 1 drug (except drugs under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act) or alter another prescriber's original prescription independently only in Alberta and under a collaborative agreement in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Moreover, they can change a drug's dosage, formulation or regimen across the country, except in Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut. Furthermore, in Alberta, Manitoba, Quebec and Nova Scotia, pharmacists are allowed to order and interpret laboratory tests 11. |

| New Zealand | Pharmacist Prescriber (Collaborative Prescribing) |

According to Pharmacy Council of New Zealand 12, “pharmacist prescribers work in a collaborative health team environment with other healthcare professionals and are not the primary diagnostician. They can write a prescription for a patient in their care to initiate or modify therapy (including discontinuation or maintenance of therapy originally initiated by another prescriber). They can also provide a wide range of assessment and treatment interventions which includes, but is not limited to: • ordering and interpreting investigation (including laboratory and related tests) • assessing and monitoring a patient's response to therapy • providing education and advice to a patient on their medicine therapy” |

CDTM, collaborative drug therapy management

There is increasing evidence of the effectiveness and safety of pharmacist prescribing. A recently published Cochrane review of 46 studies (37 337 participants) of prescribing by pharmacists (20 studies) and nurses (26 studies) compared to medical prescribing for a range of acute and chronic conditions included meta‐analyses of surrogate clinical markers 13. The review concluded that nonmedical prescribers, practising with varying but high levels of prescribing autonomy, in a range of settings, were as effective as usual care medical prescribers. Nonmedical prescribers recorded comparable outcomes for systolic blood pressure, glycated haemoglobin, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, medication adherence and health‐related quality of life. There is also emerging evidence of safety with pharmacist prescribers in Scotland performing well in pilot studies of the UK Prescribing Safety Assessment 14.

This evidence of effectiveness has the potential to support pharmacist prescribing developments across the world. In addition, feedback from key stakeholder groups in terms of their views and experiences about pharmacists prescribing is vital to determine the possible factors influencing its implementation and thus inform the development and realization of such initiatives in other countries. Such stakeholders, are defined in the context of health and associated research by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 15 as, “persons or groups that have a vested interest in a clinical decision and the evidence that supports that decision”. Examples of health stakeholders include patients, clinicians, advocacy groups, and policymakers, all of whom have roles in developing, implementing, delivering, experiencing or evaluating nonmedical prescribing interventions.

The aim of this systematic review was to critically appraise, synthesize and present the available evidence on the views and experiences of stakeholders on pharmacist prescribing, including potential facilitators and barriers, regardless of implementation status.

Methods

A systematic review protocol was developed, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Protocol (PRISMA‐P) standards, and registered on International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) at the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination in the UK (CRD42016048072) 16.

Inclusion criteria

Studies reporting views and/or experiences of any stakeholder group (e.g. patients, general public, physicians, nurses, pharmacists) pertaining to pharmacist prescribing, irrespective of the stage of implementation (pre or post), model of prescribing (e.g. supplementary, independent or collaborative), with no date or language limit up to November 2017, were included in this systematic review. All peer‐reviewed, primary research studies were included, while literature reviews, narrative reports and editorials were excluded. The inclusion process was performed by T.J. and reviewed by D.S.

Search strategy

The search string applied to Medline is given in Box 1; and adapted for Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA), PsychArticles and Google Scholar. The reference lists of all identified articles in the full text screening were searched manually for potentially eligible studies meeting the review criteria.

Box 1 Search string applied to Medline (title, abstract, keywords, subject heading).

((view* OR perspective* OR perception* OR opinion* OR attitude* OR belief* OR thought* OR feel* OR impress* OR stance* OR viewpoint* OR standpoint* OR position* OR support* OR concern* OR confiden* OR expect*)

OR

(experience* OR satisf* OR reflect* OR react* OR content* OR understand* OR encounter* OR evaluat* OR feedback))

AND

“pharmacist* prescrib*”

Assessment of methodological quality

Quality assessment was undertaken by two independent reviewers using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) 17, which permits the appraisal of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies. Consensus was reached through discussion or by a consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers, with a third included if any disagreement occurs. Data items extracted were: stated aim/objective, phase of implementation (pre vs. post), country of focus, model of prescribing, stakeholder group, study design and key findings.

Data synthesis

Due to heterogeneity of phase of implementation, models of prescribing, study designs, and variability of data collection tools, a meta‐analysis approach of quantitative findings was not possible. Hence, a narrative approach to data synthesis was applied. Pooling of qualitative research findings involved the aggregation or synthesis of findings to generate a set of statements that represented that aggregation, through assembling and categorizing findings based on similarity in meaning.

Results

The electronic search yielded 331 studies. Removal of duplicates resulted in 273 articles, 226 of which were excluded based on title, abstract, or full‐text review. An additional 18 studies were identified from other sources (e.g. reference lists) resulting in 65 eligible studies for quality assessment and data extraction. The PRISMA flow diagram is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study selection process (PRISMA flow diagram). PP: pharmacist prescribing

Quality of included studies

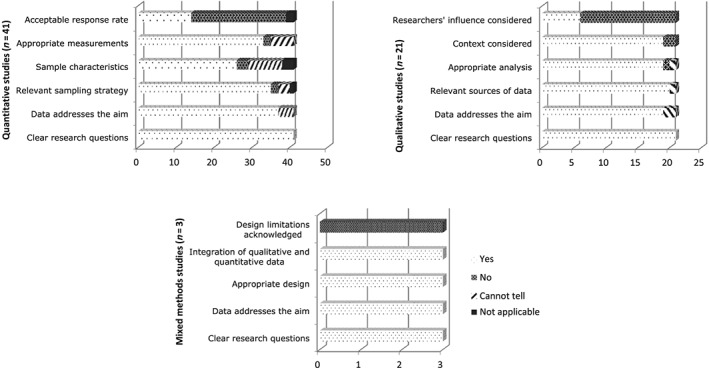

Most studies employed quantitative designs, largely questionnaire‐based survey methodology (n = 41) 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, with fewer qualitative designs (n = 21) 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79. The remaining three studies were sequential explanatory mixed methods studies all with survey followed by either focus group discussions 80, 81 or interviews 82. Quality assessments given in Figure 2 highlight the largely robust and rigorous nature of the studies reviewed.

Figure 2.

Cumulative quality assessment of the 65 studies, grouped according to study design

The key limitations of the survey studies were the lack of details around sampling strategies and the stages of questionnaire development, review and piloting. Only 14 studies had achieved the MMAT target response rate of 60% 19, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 29, 32, 36, 39, 40, 52, 54, 57. Qualitative studies lacked details of approaches to ensuring data trustworthiness and the mixed methods studies provided limited information on integrating quantitative and qualitative data. However, all 65 studies had sufficient robustness and rigour to be included in the stages of data extraction and synthesis.

Characteristics and key findings of included studies

The extracted data are summarized in Tables 3, 4 and 5 for the quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies respectively.

Table 3.

Characteristics and key findings of included quantitative studies (n = 41)

| Author (Year of publication) | Aim(s)/objective(s) | Definition and model of PP discussed | Country of focus | Stakeholder population studied (sample size) | Study design and methods | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation of pharmacist prescribing | ||||||

| Pennock et al. (1988) 38 | Explore to what extent will pharmacist prescribing be accepted by consumers | No standardized definition provided | USA | Consumers (n = 400, RR 53%) | Questionnaire | Consumers' relationships with pharmacists is important in determining acceptance of prescribing role. |

| Segal and Grines (1988) 39 | Identify attitudes of organized pharmacy, organized medicine and pharmaceutical industry about prescribing authority for pharmacists | Models of PP in each US state presented | USA | Different pharmacy and medical associations and boards, PMA, manufacturers and non‐PMA‐member generic manufacturers (n = 307, RR 63%) | Questionnaire | Hospital pharmacy associations/boards to a lesser extent in support; non‐PMA‐member generic manufacturers/US state pharmacy associations relatively neutral. Medical associations/PMA‐member companies in opposition. |

| Spencer and Edwards (1992) 40 | Ascertain GPs' attitudes to an extended role for community pharmacists | No standardized definition provided | UK | Doctors (n = 1087, RR 68.4%) | Questionnaire | Pharmacists are too influenced by commercial pressures, should stick to dispensing and not supervise repeat prescriptions. However, GPs supported pharmacists prescribing nicotine chewing gum. |

| Child et al. (1998) 41 | Identify the attitudes of hospital‐based healthcare professionals involved in drug therapy towards prescription writing and initiation of drug treatment (prescribing) by the pharmacist, explore the perceived barriers to PP, and to examine the potential future role of the pharmacist in drug therapy management | No standardized definition provided | UK | Doctors (n = 195, RR 48.7%), nurses (n = 200, RR 57.5%), pharmacists (n = 87, 77%) | Questionnaire | Postgraduate education/training and attachment to clinical area are important requirements for PP. Barriers are pharmacists' willingness to accept this role, education/training and accountability. |

| Child and Cantrill (1999) 42 | Examine the reasons behind hospital doctors' perceived barriers to PP in the UK | No standardized definition provided | UK | Hospital doctors (n = 193, RR 49%) | Questionnaire | Awareness of clinical and patient details, communication, doctor writing initial prescription, clinical responsibility and review of treatment were reported. |

| Child (2001) 43 | Examine hospital nurses' perceptions of PP in the UK | No standardized definition provided | UK | Nurses at five NHS teaching hospitals (n = 200, RR 57.5%) | Questionnaire | Pharmacists' knowledge, review of treatment, pharmacists' workload, communication and accountability issues were discussed. |

| George et al. (2006) 44 | Investigate community pharmacists' awareness, views and attitudes relating to IP by community pharmacists and their perceptions of competence and training needs for the management of some common conditions | Provided definition of UK models | UK | Community pharmacists (n = 500, RR 43.4%) | Questionnaire | Confidence in abilities to IP, training, consultation skills and communication were highlighted. Facilitators include practising more hours/week as a pharmacist, training, and involvement in Scottish Executive pharmaceutical care model schemes. |

| Kay et al. (2006) 45 | Identify Australian pharmacists' awareness of their international colleagues' prescribing practices and explore their views about the feasibility and utility of PP privileges within the scope of their current practice | Provided definition of dependent prescribing | Australia | Pharmacists (n = 4158, RR 6.4%) | Questionnaire | 74% and 52% supported dependent and independent prescribing respectively. 86% believed they could justify their prescribing while 73% believed they would benefit from prescribing authority. |

| Nguyen and Bajorek (2008) 46 | Explore the clinical utility and capacity of pharmacists to undertake prescribing functions in anticoagulation management in the hospital setting (pilot study) | No standardized definition provided | Australia | Pharmacists (n = 16), graduates (n = 2) and final year pharmacy students (n = 6) | Questionnaire | Inpatient PP can be useful but outpatient and dependent models were more appropriate. 58% of prescribing was clinically inappropriate. Barriers include training, experience and doctors' opposition. |

| Weeks and Marriott (2008) 47 | Explore the views of Society of Hospital Pharmacy Australia pharmacist members on collaborative prescribing and the extent of de facto prescribing at their institution | Provided definition for collaborative and de facto prescribing | Australia | Pharmacists (n = 1367, RR 40%) | Questionnaire | 95% thought collaborative prescribing could circumvent hospital delays with timely service delivery. If a framework existed, 75% would consider PP. |

| Hoti et al. (2010) 48 | Evaluate the views of Australian pharmacists on expanded PP roles and identify important drivers and barriers to its implementation | Current practice of Australian pharmacists presented | Australia | Pharmacists (n = 2592, RR 40.4%) | Questionnaire | 83.9% supported PP and 97.1% needed training. Inadequate training in patient assessment, diagnosis and monitoring were barriers to PP. |

| Hoti, Hughes and Sunderland (2011) 18 | Examine the views of regular pharmacy clients on PP and employ agency theory in considering the relationship between the stakeholders involved | Current practice of Australian pharmacists presented | Australia | Patients (n = 1153, RR 34.7%) | Interview (quantitative approach) | 71% trusted PP, while 66% supported doctor diagnosing first. Pharmacist diagnosing and prescribing was limited to pain management and antibiotics. 64% highlighted improved access to prescription medicines with PP. |

| Perepelkin (2011) 49 | Better understand public perceptions of pharmacists, and the acceptance of possible expanded roles for pharmacists, including prescribing authority | No standardized definition provided | Canada | General public (n = 1283, RR 31.4%) | Questionnaire | Emergency situations, renewal of long‐term medications and changing medications' frequency or strength were the most accepted scenarios for PP. |

| Erhun, Osigbesan and Awogbemi (2013) 50 | Determine the views of pharmacists and physicians on PP, appropriateness and the possible contribution to the healthcare system if pharmacists prescribe | No standardized definition provided | Nigeria | Pharmacists (n = 300, RR 61%) and physicians (n = 400, RR 40%) | Questionnaire | 77.5% of pharmacists supported while 74.4% of physicians opposed PP. However, if there was no doctor, some physicians supported PP. Reasons for opposition were legal provision and professional incompetence. |

| Hoti, Hughes and Sunderland (2013) 51 | Compare the attitudes of hospital and community pharmacists regarding an expanded prescribing role | An overview of international models presented | Australia | Pharmacists (n = 2592, RR 40.4%) | Questionnaire | Community pharmacists supported IP and emergency prescribing. Hospital pharmacists supported SP for heart failure and anticoagulant therapies; and IP for anticoagulant therapies. |

| Auta et al. (2014) 52 | Explore the views of patients of community pharmacists on their consultation experiences, and the possible extension of prescribing rights to pharmacists in Nigeria | No standardized definition provided | Nigeria | Patients (n = 432, RR 86.6%) | Questionnaire | 92.5% supported PP. 79.7% favoured restricted formulary prescribing, and 71.9% prefer to see a doctor if their conditions get worse. |

| Moore, Kennedy and McCarthy (2014) 53 | Explore GP–pharmacist relationship, gain insight into communication between the professions and evaluate opinion on extension of the role of the community pharmacist | No standardized definition provided | Ireland | Doctors (n = 500, RR 52%) and community pharmacists (n = 335, RR 62%) | Questionnaire | Compared to doctors, pharmacists were more supportive of PP. 82% of GPs and 96% of pharmacists favoured pharmacists dealing with minor ailments. |

| Hale et al. (2016) 54 | Assess whether patient satisfaction with the pharmacist as a prescriber and patient experiences in two settings of collaborative doctor–pharmacist prescribing may be barriers to implementation of PP | No standardized definition provided | Australia | Patients in preadmission (n = 200, RR 91%) and sexual health (n = 17, RR 85%) clinics | Questionnaire | Almost all patients (98% in preadmission and 97% in sexual health clinic) were satisfied with the consultation. |

| Ung et al. (2016) 55 | Explore how pharmacists can prescribe oral antibiotics to treat a limited range of infections whilst focusing on their confidence and appropriateness of prescribing | Current practice of Australian pharmacists presented | Australia | Pharmacists (n = 240, RR 34.2%) | Questionnaire | High levels of appropriate antibiotic prescribing were shown for uncomplicated urinary tract infections (97.2%), cellulitis (98.2%) and adolescent acne (100%). |

| Auta et al. (2017) 56 | Explore the views of pharmacists in Nigeria on the extension of prescribing authority to them, determine their willingness to be prescribers and identify the potential facilitators and barriers to introducing PP in Nigeria | Provided definition of UK models | Nigeria | Pharmacists (n = 775, RR 40.6%) | Questionnaire | 97.1% supported PP. Facilitators for PP were increasing patients' access to care and better utilization of pharmacists' skills. Barriers were medical resistance and pharmacists' inadequate diagnosis skills. |

| Khan et al. (2017) 57 | Assess the attitudes of rural population towards PP and their interest in using expanded PP services | No standardized definition provided | India | General public (n = 480, RR 85.4%) | Questionnaire | 81.5% supported PP. Participants with low income and tertiary education showed more interest towards PP (P < 0.05). |

| Postimplementation of pharmacist prescribing | ||||||

| Eng et al. (1990) 19 | Examine the attitudes and self‐reported prescribing activities of a sample of Florida pharmacists interviewed 6 months and 12 months after enactment of the Florida Pharmacist Self‐Care Consultant Law | No standardized definition provided | USA | Pharmacists (prescribers and nonprescribers; n = 200, RR 97% for Phase 1; n = 131, RR 66% for Phase 2) | Interview (quantitative approach) | Prescribers perceive that the law positively affected their relationships with patients. Both prescribers and nonprescribers believed that the law has not affected their relationships with physicians. |

| White‐Means and Okunade (1992) 20 | Assess the current status of IP by Florida pharmacists two years after the law was enacted, examine correlates of the choice to prescribe, and discuss policy implications of the findings | Provided a description of the Self‐Care Consultant Law | USA | Pharmacists (prescribers and nonprescribers; n = 1800, RR 32.3%) | Questionnaire | Prescribers are more likely to perceive they have enough training to prescribe and to view their skills as comparable to those of physicians, but less likely to think a PharmD is needed. |

| Erwin et al. (1996) 21 | Explore GPs' views on various drugs being dispensed by community pharmacists without a prescription to determine whether these views have changed since 1990 | No standardized definition provided | UK | Doctors (not exposed to PP; n = 250, RR 69% for fundholding, n = 600, RR 57% for nonfundholding practices) | Questionnaire | GPs overall level of approval for PP had increased. GPs from fundholding practices agreed to a slightly wider range of drugs being made available over‐the‐counter than those from nonfundholding practices. |

| George et al. (2006a) 22 | Explore SP pharmacists' early experiences of prescribing and their perceptions of the prescribing course | Provided definition of UK models | Great Britain | SP pharmacist (n = 518, RR 82.2%) | Questionnaire | Better patient management and funding issues were the main benefit and barrier respectively. Predictors of SP included time since SP registration; confidence and practicing in a setting other than community pharmacy. |

| Hobson and Sewell (2006) 23 | Study the implementation of SP by pharmacists within primary care trusts (PCTs) and secondary care trusts (SCTs) in England | Provided definition of UK models | UK | Pharmacists (not exposed to PP; n = 143, RR 68% for SCT; n = 271, RR 68% for PCT) | Questionnaire | Additional training required around the clinical area of practice for SCT and the completion of continuing professional development for PCT respondents. |

| Hobson and Sewell (2006b) 24 | Provide data on the views of chief pharmacists and PCT pharmacists on the risks and concerns surrounding SP | An overview of global experiences presented | UK | Chief pharmacists and PCT pharmacists (not exposed to PP; n = 143, RR 68% for SCT; n = 271, RR 68% for PCT) | Questionnaire | There was a positive attitude about implementing SP, but concerns rose over training and professional competency/responsibility. |

| Smalley (2006) 25 | Evaluate patients' experience of our established pharmacist‐led SP hypertension clinic | No standardized definition provided | UK | Patients who experienced SP (n = 127, RR 87%) | Questionnaire | 91% continued to attend. 57% found the care they received was better than previous care. 86% understood their condition more, were more involved in decision‐making and could easily schedule appointment. |

| George et al. (2007) 26 | Investigate the challenges experienced by pharmacists in delivering SP services, explore their perceptions of benefits of SP and obtain feedback on both SP training and implementation | Provided definition of UK SP model | Great Britain | SP pharmacists (n = 488, RR 82.2%) | Questionnaire | Better patient management was the main benefit. Barriers include lack of organizational recognition of SP and funding. Greater emphasis on clinical skills development should be part of the SP course. |

| Stewart et al. (2008) 27 | Explore patients' perspectives and experiences of pharmacist SP in Scotland | Provided definition of UK SP model | UK | Patients who experienced SP (sample size not clear, RR 57.2%) | Questionnaire | 89.3% were satisfied with the consultation, 78.7% thought it was comprehensive and most would recommend PP to others. However, 65% would prefer to consult a doctor. |

| Stewart et al. (2009) 28 | Determine the awareness of, views on, and attitudes of members of the Scottish general public toward nonmedical prescribing, with an emphasis on PP | Provided definition of UK models | UK | General public (exposed and nonexposed to PP; n = 500, RR 37.1%) | Questionnaire | 56.6% were aware of nonmedical prescribing. More than half supported PP. Concerns rose about privacy despite acknowledging its enhanced convenience. |

| McCann et al. (2011) 29 | Capture information on PP in Northern Ireland | Provided definition of UK models | UK | Pharmacists who were identified as qualified prescribers (n = 105, RR 76%) | Questionnaire | Benefits for patient care and pharmacist were reported. IP was viewed as the way forward, but concerns were raised about prescribing without a diagnosis or beyond the team setting. |

| McIntosh et al. (2011) 30 | Investigate newly registered pharmacists' awareness of PP and views on potential future roles as prescribers | No standardized definition provided | Great Britain | Newly registered pharmacists (not exposed to PP; n = 1658, RR 25.2%) | Questionnaire | 86.4% were interested in prescribing. Training is needed in clinical examination, patient monitoring and medico‐legal aspects of prescribing. 66.3% thought the current requirement for SP was appropriate. |

| Stewart et al. (2011) 31 | Evaluate the views of patients across primary care settings in Great Britain who had experienced PP | No standardized definition provided | Great Britain | Patients who experienced PP (n = 1622, RR 29.7%) | Questionnaire | The vast majority were satisfied with their consultation, believed their pharmacist prescribed as safely as their GP and considered them approachable and thorough. |

| Hutchison et al. (2012) 32 | Determine reasons for the slow adoption of prescribing authority by hospital pharmacists in the Canadian province of Alberta | An overview of PP in Canada presented | Canada | Pharmacists (not exposed to PP; n = 500, RR 62.8%) | Questionnaire | The value of PP motivates pharmacists to apply for PP. Barriers include the lengthy application process, increased liability and documentation requirements. |

| MacLure et al. (2013) 33 | Explore the views of the Scottish general public on nonmedical prescribing | Provided definition of UK models | UK | General community in Scotland (exposed and nonexposed to PP; n = 500, RR 37.1%) | Questionnaire | There was lack of awareness of NMP knowledge and training but support for a limited range of prescribing. Barriers included lack of access to medical records and issues with privacy and confidentiality. |

| Tinelli et al. (2013) 34 | Obtain feedback from primary care patients on the impact of prescribing by nurse independent prescribers and pharmacist independent prescribers on experiences of the consultation, the patient–professional relationship, access to medicines, quality of care, choice, knowledge, patient‐reported adherence and control of their condition | Provided definition of UK models | UK | Patients who experienced PP (n = 975, RR 30%) | Questionnaire | Satisfaction and confidence with pharmacist independent prescribers were high. When comparing nurse independent prescriber to doctor prescribing, most reported no difference in their experience of care. |

| Hill et al. (2014) 35 |

Not explicitly stated: Explore the acceptability of PP in addiction services in NHS Lanarkshire amongst the stakeholders and service users |

Provided definition of UK models | UK | Patients (n = 110, RR 78.2%), PP (n = 5, 100%), medical prescribers (n = 12, RR 50%) | Questionnaire | PP is seen as effective and preferred by patients. Although doctors have more reservations, the majority believed it was beneficial. All thought IP would be more beneficial. |

| Mansell et al. (2015) 36 | Determine whether patients prescribed treatment for minor ailments by a pharmacist symptomatically improve within a set time frame | No standardized definition provided | Canada | Patients who experienced PP (all population was included) | Questionnaire | Condition significantly/completely improved in 80.8% with only 4% experiencing bothersome side effects. Trust in pharmacists and convenience were the common reasons for choosing a pharmacist over a physician. |

| Bourne et al. (2016) 37 | Determine the current and proposed future IP practice of UK clinical pharmacists working in adult critical care | No standardized IP definition provided | UK | UK Clinical Pharmacy Association members (prescribers and nonprescribers; n = 404, RR 33%) | Questionnaire | Over a third were IP, and 70% intended to be prescribers within the next 3 years. Experience and working in a team facilitated IP. Pharmacists reported significant positives in patient care and job satisfaction. |

| Isenor et al. (2017) 58 | To identify the relationship between barriers and facilitators to pharmacist prescribing and self‐reported prescribing activity using the Theoretical Domains Framework version 2 | An overview of PP in Nova Scotia (Canada) presented | Canada | Pharmacists (prescribers and nonprescribers; n = 1100, RR 8%) | Questionnaire | The three domains most positively associated with prescribing were Knowledge (84%), Reinforcement (81%) and Intentions (78%). The largest effect on prescribing activity was the Skills domain. |

NMP: nonmedical prescribing; IP: independent prescribing; SP: supplementary prescribing; PP: pharmacist prescribing; RR, response rate; PMA, Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association; GP, general practitioner

Table 4.

Characteristics and key findings of included qualitative studies (n = 21)

| Author (year of publication) | Aim(s)/objective(s) | Definition and model of PP discussed | Country of focus | Stakeholder population studied (number of participants) | Study design and methods | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation of pharmacist prescribing | ||||||

| Weeks et al. (2010) 74 | Pilot a UK NMP course for Australian hospital pharmacists and elicit participants' views on NMP and experiences of the training | Provided definition of UK models | Australia | Hospital pharmacists (n = 15) | Focus group | Confidence, competency, legislative constraints, acceptance by other health providers, assessment requirements and university documentation were highlighted. |

| Hatah et al. (2013) 75 | Evaluate GPs' perceptions of pharmacists' contributions to services traditionally undertaken by GPs | Provided definition of IP | New Zealand | Doctors (n = 18) | Interview | GPs were more accepting of pharmacists' medication reviews than of PP unless appropriate controls, close collaboration and co‐location of services took place. |

| Pojskic et al. (2014) 76 | Ascertain the initial perceptions of the Ontario government and health professional stakeholder groups regarding the prospect of prescriptive authority for pharmacists | An overview of the models present internationally and in Ontario presented | Canada | Key informants from the Ontario government and provincial pharmacy and medical regulatory colleges and professional associations (n = 17) | Qualitative study using policy documents and semi‐structured interviews | Pharmacy organizations and Ontario government representatives supported while medical organizations opposed PP. |

| Bajorek et al. (2015) 77 | Explore the perspectives of GP super clinic staff on current and potential (future) pharmacist‐led services provided in this setting | No standardized definition provided | Australia | Doctors (n = 3), pharmacist (n = 1), nurse (n = 1), business manager (n = 1) and reception staff (n = 3) | Interview | Positive working relationships, satisfaction with pharmacist's current role and support for potential future roles were reported. Although GPs had differing views about PP, they saw several benefits for it. |

| Auta et al. (2016) 78 | Investigate stakeholders' views on granting prescribing authority to pharmacists in Nigeria | No standardized definition provided | Nigeria | Policymakers, pharmacists, doctors and patient group representative (n = 43) | Interview | Nonmedical stakeholders supported PP while doctors were reluctant to do so. Benefits (access to medicines) and barriers (pharmacists' diagnosis skills) were stated. |

| Le et al. (2017) 79 | Explore the potential impact of a collaborative prescribing model for opioid substitution treatment on patients, pharmacists and health provider relationships from the perspective of pharmacists and patients | No standardized definition provided | Australia | Opioid substitution treatment patients (n = 14) and community pharmacists (n = 18) | Interviews with patients and focus groups with pharmacists | Benefits included improved continuity of care and convenience. Changes to healthcare relationships and ensuring adequate support of PP were highlighted. |

| Postimplementation of pharmacist prescribing | ||||||

| Lloyd and Hughes (2007) 59 | Explore the views and professional context of pharmacists and physicians (who acted as their training mentors), prior to the start of SP training | Provided definition of UK SP model | UK | Pharmacists prescribers (n = 47) and their mentors (n = 35) | Focus groups with pharmacists and face‐to‐face semi‐structured interviews with the mentors | SP was anticipated to improve patient care and interprofessional relationships. Loss of diversity, deskilling of junior doctors, safety and professional encroachment were reported. |

| Tully et al. (2007) 60 | Investigate the views and experiences of pharmacists in England before and after they registered as SP | Provided definition of UK SP model | UK | Pharmacists (before and after registering as SPs; n = 8) | Interview | Pharmacists thought training would legitimize their current informal prescribing. Pharmacists already involved with prescribing were more likely to work as prescribers. |

| Blenkinsopp et al. (2008) 61 | Explore GPs perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of pharmacist SP and the future introduction of IP | Provided definition of UK models | UK | Doctors who had experienced SP (n = 13) | Focus group | Not all referred patients to the PP. Those GPs who referred patients described benefits with some ambivalence. |

| Stewart et al. (2009) 62 | Explore the perspectives of pharmacist SP, their linked independent prescribers and patients, across a range of settings, in Scotland, towards PP | Provided definition of UK models | UK | SP pharmacists (n = 9), their mentors (n = 8) and patients (n = 18) | Interview | All were supportive of SP identifying benefits for patients and the wider healthcare. Pharmacists were keen on IP but not doctors citing inadequate examination skills. |

| Weiss and Sutton (2009) 63 | Investigate the potential threat to medical dominance posed by the addition of pharmacists as prescribers in the UK and explore the role of prescribing as an indicator of professional power, the legitimacy and status of new PP and the forces influencing professional jurisdictional claims over the task of prescribing | Provided definition of UK models | UK | SP pharmacists (n = 23) | Interview | Facilitators include blurred definitions of prescribing, competence and a team approach to patient management. |

| Hobson et al. (2010) 64 | Explore the opinions of patients on the development of NMP | Provided definition of UK models | UK | Patients (exposed and not exposed to PP; n = 18) | Interview | Concerns rose about clinical governance, privacy and space. Participants acknowledged pharmacists' knowledge and accessibility. |

| Lloyd et al. (2010) 65 | Explore the context and experiences, in relation to the practice of SP, of pharmacists and physicians (who acted as their training mentors) at least 12 months after pharmacists had qualified as SP | Provided definition for UK IP model | UK | SP pharmacists (n = 40) and their mentors (n = 31) | Focus groups with pharmacists and face‐to‐face semistructured interviews with the mentors | PP was perceived to reduce doctors' workload and improved continuity of care. IP was seen as contentious by mentors due to the diagnostic element. |

| Tonna et al. (2010) 66 | Explore pharmacists' perceptions of the feasibility and value of PP of antimicrobials in secondary care in Scotland | Provided definition of UK models | UK | Senior hospital pharmacists (prescribers and nonprescribers; n = 37) | Focus group | Perceived benefits included quicker access to medicines, reduced risk of resistance and better application of evidence‐based medicine. |

| Dawoud et al. (2011) 67 | Investigate pharmacist prescribers' views and experiences of the early stages of SP implementation | Provided definition for independent, dependent and collaborative prescribing models | UK | SP pharmacists (n = 16) | Interview | Benefits reported on patient care and pharmacists' job satisfaction. SP limited pharmacists' freedom in decision making. Hence, IP was supported. |

| McCann et al. (2012a) 68 | Explore patients' perspectives of pharmacists as prescribers | Provided definition of UK models | UK | Patients who experienced PP (n = 34) | Focus group | Patients supported PP especially in a team setting. However, there was a lack of awareness of PP role. |

| McCann et al. (2012b) 69 | Provide an in‐depth understanding of PP from the perspective of pharmacists, medical colleagues and other key stakeholders in Northern Ireland | Provided definition of UK SP model | UK | PP (n = 11), medical colleagues (n = 11) and other key stakeholders (n = 13) | Interview | PP resulted in a more holistic approach to care. Challenges include working within areas of competency, complex conditions and resistance by older doctors. |

| Makowsky et al. (2013) 70 | Understand what factors influence pharmacists' adoption of prescribing using a model for the diffusion of innovations in healthcare services | An overview of prescribing authority in Alberta presented | Canada | Pharmacists (prescribers and nonprescribers; n = 38) | Interview | PP was dependent on the innovation itself, adopter, system readiness, practice setting, communication and influence. |

| Deslandes et al. (2015) 71 | Explore the views and experiences of patients with mental illness on being managed by a pharmacist SP in a secondary care outpatient setting | Provided definition of UK SP model | UK | Patients with mental illness who experienced SP (n = 11) | Exploratory study using semi‐structured interviews and self‐completion diaries | Patients supported PP and felt they were involved in decisions concerning their healthcare. |

| Feehan et al. (2016) 72 | Investigate the perceived demand for and barriers to PP in the community pharmacy setting | An overview of prescribing authority in USA presented | USA | Consumers (n = 19), community pharmacists (n = 20) and re‐imbursement decision‐makers (n = 8; not exposed to PP) | Interview | Consumers opposed. Pharmacists supported PP for limited conditions. Reimbursement decision‐makers were most receptive. Barriers included awareness of PP, pharmacist training, conflicts of interest and liability issues. |

| McIntosh and Stewart (2016) 73 | Explore the views and reflections on PP of UK preregistration pharmacy graduates | No standardized definition provided | UK | Preregistration pharmacy graduates (n = 12) | Interview | Support was related to professional development. Barriers included lack of organizational strategy, confidence and workload. |

NMP: nonmedical prescribing; IP: independent prescribing; SP: supplementary prescribing; PP: pharmacist prescribing; GP, general practitioner

Table 5.

Characteristics and key findings of included mixed‐methods studies (n = 3)

| Author (year of publication) | Aim(s)/objective(s) | Definition and model of PP discussed | Country of focus | Stakeholder population studied (sample size) | Study design and methods | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation of PP | ||||||

| Hanes and Bajorek (2005) 81 | Explore the views of a sample of Australian hospital pharmacists on prescribing privileges | Provided a definition for dependent prescribing | Australia | Hospital pharmacists (n = 10) and teacher practitioners (n = 5; 15 completed the questionnaire, 8 participated in the focus groups) | Questionnaire and focus group | Benefits include more efficient/improved pharmaceutical care and reduced healthcare costs. Physician opposition was a barrier. Training and accreditation beyond registration was deemed necessary. |

| Vracar and Bajorek (2008) 82 | Explore Australian GPs' views on extending prescribing rights to pharmacists, the appropriateness of PP models, and the influence of GPs' characteristics on their preference for a particular PP model | An overview of international models presented | Australia | Doctors (150 approached, 22 filled the questionnaire and 10 participated in the interview) | Questionnaire and semistructured interview | Repeat prescribing and prescribing by referral were the most favoured. Safety issues, lack of awareness of pharmacist training and capabilities, clinical responsibility, GP–patient relationship and remuneration were raised. |

| Postimplementation of PP | ||||||

| Baqir (2010) 80 | Evaluate the extent of PP and identify some of the barriers to maintaining and developing such services | No standardized definition provided | UK | Pharmacists who undertook a prescribing course (179 were invited to participate, 98 filled the questionnaire but not clear how many were involved in the focus groups) |

Multiple methods: questionnaire, focus groups, documents review and interviews |

In secondary care, easy access to medical records and prescription pads as well as close working relationships with doctors were facilitators. The major barrier was lack of a clear strategy at organizational level. |

PP: pharmacist prescribing; GP, general practitioner

Of the 65 studies, 29 (45%) were conducted prior to the implementation of pharmacist prescribing in the country of study 18, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 81, 82, while the remaining 35 (54%) were conducted postimplementation 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 58, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 80. Only one study explored views and experiences pre‐ and postregistration 60.

Most of the included studies were conducted in the UK (n = 34, 52%) 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 37, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 71, 73, 80, followed by Australia (n = 13, 20%) 18, 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 54, 55, 74, 77, 79, 81, 82, Canada (n = 6, 9%) 32, 36, 49, 58, 70, 76, USA (n = 5, 8%) 19, 20, 38, 39, 72, Nigeria (n = 4, 6%) 50, 52, 56, 78, and one each for Ireland 53, India 57 and New Zealand 75.

The main stakeholder group studied was pharmacists (n = 27, 42%), including those registered as prescribers 22, 26, 29, 63, 67, 80, nonprescribers 23, 24, 30, 32, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 55, 56, 73, 74, or mixed prescribers and nonprescribers 19, 20, 37, 58, 60, 66, 70. Fewer studies investigated the perceptions of patients (n = 12, 19%) 18, 25, 27, 31, 34, 36, 38, 52, 54, 64, 68, 71, doctors (n = 6, 9%) 21, 40, 42, 61, 75, 82, the general public (n = 4, 6%) 28, 33, 49, 57, nurses (n = 1, 2%) 43 or policymakers (n = 1, 2%) 76. Fourteen studies reported multiple stakeholder perspectives 35, 39, 41, 50, 53, 59, 62, 65, 69, 72, 77, 78, 79, 81.

While most studies (n = 41, 63%) provided a standardized or legislative definition of pharmacist prescribing, 24 (37%) did not 19, 21, 25, 30, 31, 36, 37, 38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 46, 49, 50, 52, 53, 54, 57, 73, 77, 78, 79, 80.

For quantitative studies, the sample size ranged from 105 to 4158, with response rates of 6.4% to 87%. By contrast, qualitative studies included between eight and 82 participants. For mixed methods studies, the sample size in the quantitative element ranged from 15 to 179, with response rates of 15–100%, while the number of participants in the qualitative element ranged from eight to 10.

Stakeholders' views and experiences of pharmacist prescribing

The majority of both pre‐ and postimplementation studies included reported support for prescribing pharmacists.

Preimplementation studies

-

a.

General public: Two studies investigated the public's perceptions of granting pharmacists the authority to prescribe in Canada and India. Respondents were generally supportive of prescribing by pharmacists who received training in specific situations, which included: the physician having made the diagnosis, prescribing from a limited range, in emergency situations, prescribing alternative medicines for the same medical condition, renewing prescriptions, or modifying the strength or frequency of medicines prescribed by a physician 49, 57.

-

b.

Patients: Studies of patients and patient group representatives reported support for pharmacist prescribing 18, 38, 52, 54, 78, 79, which was perceived as likely to improve access to healthcare generally and consultation with a trained health professional making better use of pharmacists' skills 18, 52, 54, 79. Respondents in several studies noted the need for the pharmacist prescribers to have undertaken additional training, after a physician's diagnosis, and that prescribing should be from a restricted list of medicines 18, 52, 79.

-

c.

Pharmacists: Pharmacists themselves were generally supportive of a prescribing role, which they perceived as a logical development given their expertise in medicines, their existing over‐the‐counter prescribing‐related activities, and their increasingly evolving clinical roles as part of the multidisciplinary team in secondary care. Moreover, they anticipated that outcomes would include quicker and easier patient access to medicines, promoting better use of their skills with resultant enhanced status, as well as increased job satisfaction 41, 46, 47, 48, 50, 51, 53, 74, 78, 79, 81. There was agreement that they required additional training prior to assuming a prescribing role 41, 45, 46, 55, 56, 79.

There were diverse views on the models and scope of prescribing which ranged from prescribing within an agreed clinical management plan (CMP), repeat prescribing for stabilized chronic conditions, and modifying treatment based on the results of laboratory tests ordered by themselves 56, 74, 81. Many respondents also viewed IP as appropriate for pharmacists, noting that it will be safe and effective and improve patient access to medicines. They generally held the view that physicians would be in favour of pharmacist prescribing 51, 55.

-

d.

Doctors: Studies conducted preimplementation of pharmacist prescribing reported a range of views from doctors (n = 9). In one study conducted in the UK, the majority of respondents were supportive, provided that additional postgraduate education/training was undertaken 41. In other studies, physicians were more cautious in their support, but acknowledged that a model of pharmacist prescribing for limited conditions, such as minor ailments, was a logical development 40, 50, 53, 75, 78.

Other studies reported physicians' concern over: pharmacists' lack of clinical assessment and diagnosis skills, lack of access to individual patient medical records, legal considerations such as division of clinical responsibility of care, a potential negative effect on the physician–patient relationship, and issues concerning communication between the pharmacist prescriber and other members of the multidisciplinary team 42, 53, 82.

-

e.

Nurses: Two UK studies reported the perspectives of nurses with respondents considering pharmacist prescribing for existing or new therapy very useful due to their knowledge in pharmacology and a belief that it will be clearer and safer 41, 43.

-

f.

Policymakers: Government and pharmacy policymakers from the USA, Canada, and Nigeria anticipated benefit to pharmacist prescribing in terms of improved continuity of care, better patient outcomes, reduced prescribing costs, and reduced physician workload 39, 76, 78. Concerns were, however, expressed by medical policymakers in relation to the need for additional training and access to individual patient medical records, without which there could be fragmented care 76.

Postimplementation studies

-

a.

General public: Two studies reported the perspectives of samples of the public, both exposed to pharmacist prescribing and not exposed to it, in the UK. Findings highlighted general support, particularly for the management of minor ailments and issuing repeat prescriptions. There were some concerns over pharmacists' training in diagnosis, lack of access to patients' medical records, and potential lack of privacy and confidentiality within a community pharmacy setting 28, 33.

-

b.

Patients: Nine studies assessed the experience of patients who were exposed to pharmacist prescribing, while Hobson et al. included exposed and unexposed patients in the UK 64 and Feehan et al. had US patients who had never been exposed to pharmacist prescribing 72.

The majority of those patients who had consulted with a pharmacist prescriber were highly satisfied with the consultation overall, particularly the pharmacist's competence and capability, considering their prescribing to be as effective and safe as their physician. They also gave positive feedback relating to the pharmacist's personality, knowledge and communication skills as well as the consistency, accessibility, length and outcome of the care received 25, 27, 31, 34, 35, 36, 62, 64, 68, 71.

In a recent study of prescribing by community pharmacists in the USA, patients who had yet to experience pharmacist prescribing were of the view that pharmacists should only dispense and provide medicines information other than a possible role in prescribing for minor conditions 72.

-

c.

Pharmacists: Twenty‐four studies researched the perspectives of pharmacists postimplementation of prescribing rights mainly in the UK (n = 18], US 3, and Canada 3. The pharmacists sample in these studies included either prescribers 22, 26, 29, 35, 59, 62, 63, 65, 67, 69, 80, nonprescribers 23, 24, 30, 32, 72, 73 or both 19, 20, 37, 58, 60, 66, 70. Pharmacists positively perceived this expanded professional role and reported that drivers to undertake pharmacist prescribing include developing a clinical role, better patient management, personal development, enhancing job and patient satisfaction, improving self‐confidence as well as reducing cost of therapy 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 29, 30, 32, 35, 37, 58, 59, 60, 62, 63, 65, 66, 67, 69, 70, 73, 80.

Studies also concluded that implementing pharmacist prescribing was easier in secondary care compared to primary or community care due to logistics related to access to medical records and networking environment 29, 59, 65, 70, 80.

Negative attitudes towards prescribing pharmacists were mainly related to increased liability, lack of time to engage in prescribing and lack of experience in diagnosis, in addition to medical resistance and difficulties in developing a CMP for every patient 19, 29, 30, 59, 60, 65, 66, 70.

Due to liability and diagnosis‐related issues, pharmacists preferred SP or prescribing for minor and chronic conditions 63, 66, 72. However, other studies reported that SP was not believed to significantly save physicians' time or improve patient care due to the limited list of drugs they can prescribe under the CMP. Thus, IP will have a better impact 24, 29, 35, 62, 63, 65, 67.

-

d.

Doctors: Seven studies explored doctors' perceptions of this new role for pharmacists, all of which were conducted in the UK. Of those, six studies reported the perspectives of doctors who had worked alongside pharmacist prescribers. The majority supported pharmacist prescribing across the studies with some benefits highlighted including more holistic and continuous patient care, better use of pharmacists' skills, effects of enhancing physicians' medicines knowledge, and drug cost saving 59, 61, 62, 65, 69. While physicians reported reduced direct‐patient workload, the need to develop individual patient CMPs for SP was burdensome hence the impending implementation of IP was welcomed 35.

The only study that investigated doctors who were not exposed to prescribing pharmacists reported that, with time, doctors are more likely to accept this new role 21.

-

e.

Policymakers: Only one study from the USA explored the perceptions of policymakers involved in medical services coverage or formulary policies after the realisation of pharmacist prescribing. The main findings were that these decision‐makers responded positively to pharmacist prescribing due to pharmacists' knowledge about drugs and their mechanisms of action 72.

Facilitators of and barriers to pharmacist prescribing implementation

Many studies (n = 27, 42%) reported facilitators and barriers to the implementation of pharmacist prescribers as perceived by the different stakeholder groups 22, 23, 24, 26, 29, 37, 45, 46, 48, 50, 51, 56, 58, 59, 60, 62, 64, 65, 67, 69, 70, 72, 73, 77, 78, 80, 81, which are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Facilitators and barriers to pharmacist prescribing

| Facilitators |

• Pharmacists' personal qualities (communication skills, training, experience and enthusiasm) • Practice setting (secondary vs. primary vs. community) • Organizational, managerial and medical colleagues' support • Resources (workforce, space, access to medical records) |

| Barriers |

• Pharmacists' skills (clinical examination and diagnostic skills) • Resources (workforce, access to medical records, space, time) • Physicians and organizational support • Funding • Legal aspects (accountability, conflict of interest) • Pharmacy practice recognition |

The major facilitators to this role include pharmacist personal qualities (enthusiasm, communication skills, experience and training), practice setting (working in an interprofessional team), organizational, managerial and medical colleagues' support, as well as infrastructure and resources (number of pharmacist available, space and access to medical records) 22, 23, 58, 59, 67, 69, 70.

The main barriers reported are pharmacists' poor clinical skills if not prescribing collaboratively and issues relating to resources (access to medical records, shortage in pharmacy workforce, funding, time), support (doctors’ opposition), logistics (accountability, conflict of interest, referral process) and poor recognition of pharmacy profession 22, 24, 26, 29, 45, 46, 48, 50, 51, 56, 58, 59, 60, 62, 64, 65, 69, 72, 73, 77, 78, 80, 81.

Discussion

This systematic review summarizes the evidence around the views and experiences surrounding pharmacist prescribing from the perspectives of a diverse range of stakeholders in a range of countries and settings.

The majority of studies pre‐ and postimplementation reported positive views and experiences with main benefits described as: increased access to healthcare services, perceptions of enhanced patient outcomes, better use of pharmacists' skills and knowledge, improved job satisfaction, and reduced physician workload. However, concerns were noted over issues of: liability, limited pharmacist diagnosis skills, access to medical records, and lack of organizational and financial support. While review findings are derived from many studies of generally high methodological quality, there is a lack of mixed‐methods approaches. These are being used increasingly within healthcare and allow both quantification of findings and in‐depth exploration of key issues 83.

Healthcare policies in countries such as the UK support the expansion of pharmacist prescribing and indeed there is a move to increase the number of pharmacists practicing within primary care practices 84. The positive findings of this systematic review, together with previous reviews of effectiveness and safety 13, 85, 86, 87, 88, provide evidence to support such developments. Furthermore, such review findings are important in those countries and settings starting to explore and develop models of pharmacist prescribing 2. Interpretation and extrapolation of findings from studies conducted preimplementation are limited in that participants may not be fully aware of the aim, nature and scope of the intervention and may be influenced by experiences of similar or diverse interventions. This is apparent in terms of concerns over independent prescribing models in the UK and pharmacists' limited training in diagnosis. While this does allow assessment and prescribing of undiagnosed conditions, this must be within the prescribers' competence and indeed most pharmacist independent prescribers practise with patients in whom diagnosis has already been established by the doctor 6. Concerns such as liability and skills that were voiced preimplementation were less common postimplementation as such studies allow participants to reflect on their real‐life experiences. For example, doctors who had worked alongside pharmacist prescribers and patients managed by the pharmacists were very supportive of their professionalism and skills.

While lack of access to medical records is an issue, most notably within community pharmacy settings, this is being addressed within the UK with pharmacists having access to specific limited sections of the electronic medical record 89. Many of the barriers and indeed facilitators can be explained by theories of implementation. It is therefore notable that only three of the 65 studies incorporated any mention of theory within the study design, conduct, and reporting 18, 58, 70. There is a need for implementation studies to focus on theory to allow more systematic and comprehensive investigation of facilitators and barriers. Similarly, those planning implementation should include key theoretical elements at the outset to heighten the facilitators and lessen the barriers such as inadequate funding, access to resources, etc. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is an integrative framework derived from many different theories. It is described in five domains: intervention characteristics; outer setting; inner setting; characteristics of the individuals involved; and the process of implementation 90. All barriers identified postimplementation of pharmacist prescribing (e.g. funding, access issues etc.) would be eliminated in advance by using CFIR since it can serve as a guide for implementing an innovation. However, it is likely that these barriers reflected the stage of implementation and are likely to have been resolved over time.

Previous reviews have been limited in nature and rigour (thematic and scoping reviews], focused on preimplementation, lacked quality assessment of included studies, and focused on limited ranges of stakeholders in specific countries (UK and Canada) 88, 91, 92. This systematic review was conducted according to best practices and is reported in accordance with the PRISMA Statement standards 93. Furthermore, it was not limited to a specific country, setting, stakeholder group or implementation stage. However, the generalizability or transferability of findings to other countries or cultures may be limited, given that almost all studies were conducted postimplementation in the western world and mainly focused on pharmacists' perspectives. Moreover, several of these studies were conducted several years ago hence may no longer accurately reflect the current situation in those countries. While many implementation studies have been reported, it is still necessary to conduct such investigations in any country or setting planning to establish pharmacist prescribing to learn from the evidence‐base. Future developments and studies should pay attention to theories of implementation and adopt mixed methods approaches with an inclusive range of stakeholders.

Conclusion

Many studies have reported stakeholders' views and experiences of pharmacist prescribing, pre‐ and postimplementation. While studies were from a limited number of countries, the overwhelming finding was positive, particularly in relation to increased access to healthcare services, perceptions of enhanced patients' outcomes, better use of pharmacists' skills and knowledge, improved job satisfaction, and reduced physicians' workload. Concerns were largely identified preimplementation and were related to organizational issues and perceived lack of pharmacists' diagnosis skills.

Competing Interest

There are no competing interests to declare. All authors have read and approved the final draft.

This review is part of a self-funded PhD project.

Jebara, T. , Cunningham, S. , MacLure, K. , Awaisu, A. , Pallivalapila, A. , and Stewart, D. (2018) Stakeholders' views and experiences of pharmacist prescribing: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 1883–1905. 10.1111/bcp.13624.

References

- 1. Cope L, Abuzour A, Tully M. Nonmedical prescribing: where are we now? Ther Adv Drug Saf 2016; 7: 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stewart D, Jebara T, Cunningham S, Awaisu A, Pallivalapila A, MacLure K. Future perspectives on nonmedical prescribing. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2017; 8: 183–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stewart D, MacLure K, George J. Educating non medical prescribers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 74: 662–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Royal Pharmaceutical Society . A competency framework for all prescribers. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society [online]. Available at http://www.rpharms.com/support-pdfs/prescribing-competency-framework.pdf (last accessed 15 November 2016).

- 5. Department of Health . Supplementary prescribing by nurses and pharmacists within the NHS in England. A guide for implementation London: UK Department of Health [online], 2003. Available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4009717 (last accessed 3 August 2016).

- 6. Department of Health . Improving patients' access to medicines: A guide to implementing nurse and pharmacist independent prescribing within the NHS in England. [online]. London: UK Department of Health; 2006. Available at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/PublicationsandStatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyandGuidance/DH_4133743 (last accessed 3 August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scottish Government . Achieving Excellence in Pharmaceutical Care: A Strategy for Scotland. [online]. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government; 2017. Available at http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0052/00523589.pdf (last accessed 13 November 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scottish Government . Prescription for Excellence. [online]. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government; 2013. Available at http://www.gov.scot/resource/0043/00434053.pdf (last accessed 13 December 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hammond RW, Schwartz AH, Campbell MJ, Remington TL, Chuck S, Blair MM, et al Collaborative drug therapy management by pharmacists. Pharmacotherapy 2003; 23: 1210–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Collaborative Practice Agreements and Pharmacists' Patient Care Services: A Resource for Pharmacists. [online]. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/Translational_Tools_Pharmacists.pdf (last accessed 13 November 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Canadian Pharmacists Association . Pharmacists' expanded scope of practice. [online]. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2016. Available at https://www.pharmacists.ca/pharmacy-in-canada/scope-of-practice-canada/ (last accessed 19 February 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pharmacy Council of New Zealand . Pharmacist prescribers. [online]. New Zealand: Pharmacy Council of New Zealand; 2010. Available at http://www.pharmacycouncil.org.nz/prescriber (last accessed 19 February 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weeks G, George J, MacLure K, Stewart D. Non‐medical prescribing versus medical prescribing for acute and chronic disease management in primary and secondary care (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [online], 2016. Available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011227.pub2/abstract;jsessionid=F67CA2107869A3661BD1BE0D80C10B1C.f02t04 (last accessed 14 February 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. Reid F, Power A, Stewart D, Watson A, Zlotos L, Campbell D, et al Piloting the United Kingdom 'Prescribing Safety Assessment' with pharmacist prescribers in Scotland. Res Social Adm Pharm 2018; 14: 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Chapter 3: Getting involved in the research process [online]. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/stakeholderguide/chapter3.html (last accessed 22 August 2016).

- 16. Jebara T, Stewart D, Cunningham S, MacLure K, Awaisu A, Pallivalapila A. Stakeholders' views and experiences of pharmacist prescribing: a systematic review protocol [online]. York: PROSPERO; 2016. Available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO_REBRANDING/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016048072 (last accessed 6 December 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, et al Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews [online]. Montreal: McGill University; 2011. Available at http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/84371689/MMAT%202011%20criteria%20and%20tutorial%202011-06-29updated2014.08.21.pdf (last accessed 10 January 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoti K, Hughes J, Sunderland B. Pharmacy clients' attitudes to expanded pharmacist prescribing and the role of agency theory on involved stakeholders. Int J Pharm Pract 2011; 19: 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eng HJ, McCormick WC, Kimberlin CL. First year's experience with the Florida pharmacist self‐care consultant law: pharmacist perspective. J Pharm Mark Manage (USA). 1990; 4: 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20. White‐Means S, Okunade AA. Current status of prescribing pharmacists in Florida: implications from the 1989 Florida Prescriber Pharmacists Practice Survey (FPPPS). J Pharm Mark Manage (USA). 1992; 7: 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Erwin J, Britten N, Jones R. General practitioners' views on over the counter sales by community pharmacists. Br Med J (England) 1996; 312: 617–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. George J, McCaig DJ, Bond CM, Cunningham ITS, Diack HL, Watson AM, et al Supplementary prescribing: early experiences of pharmacists in Great Britain. Ann Pharmacother 2006; 40: 1843–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hobson RJ, Sewell GJ. Supplementary prescribing by pharmacists in England. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2006; 63: 244–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hobson RJ, Sewell GJ. Risks and concerns about supplementary prescribing: survey of primary and secondary care pharmacists. Pharm World Sci 2006; 28: 76–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smalley L. Patients' experience of pharmacist‐led supplementary prescribing in primary care. Pharm J (England) 2006; 276: 567–569. [Google Scholar]

- 26. George J, McCaig DJ, Bond CM, Cunningham ITS, Diack HL, Stewart D. Benefits and challenges of prescribing training and implementation: perceptions and early experiences of RPSGB prescribers. Int J Pharm Pract 2007; 15: 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stewart D, George J, Bond CM, Cunningham ITS, Diack HL, McCaig DJ. Exploring patients' perspectives of pharmacist supplementary prescribing in Scotland. Pharm World Sci 2008; 30: 892–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stewart D, George J, Diack HL, Bond CM, McCaig DJ, Cunningham IS, et al Cross sectional survey of the Scottish general public's awareness of, views on, and attitudes toward nonmedical prescribing. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43: 1115–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCann L, Haughey S, Parsons C, Lloyd F, Crealey G, Gormley GJ, et al Pharmacist prescribing in Northern Ireland: a quantitative assessment. Int J Clin Pharm 2011; 33: 824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McIntosh T, Munro K, McLay J, Stewart D. A cross sectional survey of the views of newly registered pharmacists in Great Britain on their potential prescribing role: a cautious approach. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011; 73: 656–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stewart D, MacLure K, Bond CM, Cunningham S, Diack L, George J, et al Pharmacist prescribing in primary care: the views of patients across Great Britain who had experienced the service. Int J Pharm Pract 2011; 19: 328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hutchison J, Lindblad A, Guirguis L, Cooney D, Rodway M. Survey of Alberta hospital pharmacists' perspectives on additional prescribing authorization. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2012; 69: 1983–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacLure K, George J, Diack L, Bond C, Cunningham S, Stewart D. Views of the Scottish general public on non‐medical prescribing. Int J Clin Pharm 2013; 35: 704–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tinelli M, Blenkinsopp A, Latter S, Smith A, Chapman S. Survey of patients' experiences and perceptions of care provided by nurse and pharmacist independent prescribers in primary care. Health Expect 2013; 18: 1241–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hill DR, Conroy S, Brown RC, Burt GA, Campbell D. Stakeholder views on pharmacist prescribing in addiction services in NHS Lanarkshire. J Subst Use 2014; 19: 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mansell K, Bootsman N, Kuntz A, Taylor J. Evaluating pharmacist prescribing for minor ailments. Int J Pharm Pract 2015; 23: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bourne RS, Whiting P, Brown LS, Borthwick M. Pharmacist independent prescribing in critical care: results of a national questionnaire to establish the 2014 UK position. Int J Pharm Pract 2016; 24: 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pennock AS, McCormick WC, Angorn RA, Eng HE. Consumer acceptance of pharmacist prescribing. J Pharm Mark Manage (USA) 1988; 3: 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Segal R, Grines LL. Prescribing authority for pharmacists as viewed by organized pharmacy, organized medicine and the pharmaceutical industry. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 1988; 22: 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spencer JA, Edwards C. Pharmacy beyond the dispensary: general practitioners' views. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1992; 304: 1670–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Child D, Hirsch C, Berry M. Health care professionals' views on hospital pharmacist prescribing in the United Kingdom. Int J Pharm Pract (England). 1998; 6: 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Child D, Cantrill JA. Hospital doctors' perceived barriers to pharmacist prescribing. Int J Pharm Pract (England). 1999; 7: 230–237. [Google Scholar]