Abstract

The pathological processes of Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus have been demonstrated to be linked together. Both PDE9 inhibitors and PPARγ agonists such as rosiglitazone exhibited remarkable preclinical and clinical treatment effects for these two diseases. In this study, a series of PDE9 inhibitors combining the pharmacophore of rosiglitazone were discovered. All the compounds possessed remarkable affinities towards PDE9 and four of them have the IC50 values <5 nmol/L. In addition, these four compounds showed low cell toxicity in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Compound 11a, the most effective one, gave the IC50 of 1.1 nmol/L towards PDE9, which is significantly better than the reference compounds PF-04447943 and BAY 73-6691. The analysis of putative binding patterns and binding free energy of the designed compounds with PDE9 may explain the structure—activity relationships and provide evidence for further structural modifications.

KEY WORDS: PDE9 inhibitors, Alzheimer's disease, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Rosiglitazone, Molecular docking, Dynamics simulation

Graphical abstract

Both PDE9 inhibitors and PPARγ agonists such as rosiglitazone exhibited remarkable preclinical and clinical treatment effects for Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. A series of PDE9 inhibitors combining the pharmacophore of rosiglitazone were discovered. Four of them exhibited excellent inhibitory activity against PDE9A and low cell toxicity. The most effective compound 11a gave the IC50 of 1.0 nmol/L towards PDE9, which was significantly better than the reference compounds PF-04447943 and BAY 73-6691.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are two common and frequently occurring diseases of the elderly. Alzheimer's disease is characterized by neurodegenerative disorders, such as progressive memory loss, decline in language skills and cognitive dysfunction1. About 46.8 million people worldwide are currently suffering from AD and one out of three dead seniors has been diagnosed with AD2. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a polygenic disease of metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and loss of β-cell function3, which is expected to affect about 370 million people worldwide by 20304. Recent clinical studies demonstrated that some pathological processes of AD and T2DM are linked to each other5, 6, 7. The neuron damage in the brain of AD patients may be caused by hyperglycemia. A great number of patients with T2DM suffer a significant decline in cognitive function, and about 70% of them eventually develop to AD patients. Furthermore, patients with T2DM have a 1.5—2.5 times higher risk of AD than the general population.

Although the pathological links between AD and T2DM are still unclear, the nitric oxide (NO)/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)/cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) signaling pathway has been identified to be important in the process of both AD and T2DM. For the AD patients, the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway is involved in the signal transduction and synaptic plasticity in the brain, which can activate the transcription factor cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein (CREB) to enhance synaptic plasticity, neuronal growth, and then increase the activities of neurotrophic factors including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), etc.8. In diabetes, the phosphorylation of vasodilator stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP), which plays a key role in the inhibition of platelet activation, can be induced by the activation of NO/cGMP/PKG pathway, resulting in the increased concentration of intracellular Ca2+ and attenuating vascular inflammation and insulin resistance9.

Phosphodiesterases (PDEs) are one super enzyme families in charge of hydrolyzing cAMP and cGMP. Among the 11 subfamilies of PDEs, PDE5, PDE6, and PDE9 specially hydrolyze cGMP, the inhibition of which can increase the level of cGMP and active the NO/cGMP/PKG signaling pathway efficiently10. Numerous preclinical and clinical studies were performed to investigate the effect and underlying mechanisms of PDE5 and PDE9 inhibition for the treatment of AD or T2DM (The PDE6 enzyme is difficult to be obtained and no PDE6 inhibitor has been reported yet), demonstrating that PDEs worked as potential targets for AD or T2DM11, 12.

Compared with PDE5 and other PDEs families, PDE9 has the highest affinity of cGMP, indicating that the inhibition of PDE9 might have better results than others to increase the level of cGMP13. Several PDE9 inhibitors were patented for the potential treatment of AD or T2DM14, 15, 16. For example, PDE9 inhibitor 3r reported by our group can inhibit the mRNA expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) and glucose 6-phosphatase (G-6-Pase), working as a hypoglycemic agent potentially17. PDE9 inhibitor BAY 73-6691 can enhance the ability of acquisition, consolidation, and retention of long-term memory (LTP), improving scopolamine-induced passive avoidance deficit and MK-801-induced short-term memory deficits in the social and object recognition tasks of rodents18. Furthermore, PDE9 inhibitors PF-04447943 and BI-409306 have already been completed several Phase II clinical trials of AD currently19. Despite of the unique advantages of PDE9 inhibitors and good therapeutic effects obtained in preclinical and clinical studies, researches on PDE9 inhibitors are relatively limited compared with other PDE families, such as PDE5 and PDE4, which have already have several marketed drugs. In order to accelerate the application of PDE9 inhibitors, discovery of novel and effective PDE9 inhibitors is in high demand.

Rosiglitazone is a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) agonist approved for the treatment of T2DM. It can increase insulin sensitivity, leading to the channeling of fatty acids into adipose tissue and reducing their concentration in the plasma, and thus alleviating insulin resistance and improving plasma glucose levels effectively20, 21. Recent studies demonstrated that rosiglitazone reduced Aβ-induced oxidative stress, toxicity and the tau phosphorylation, exerting neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects22. Currently, rosiglitazone is under a Phase III clinical trial in AD patients.

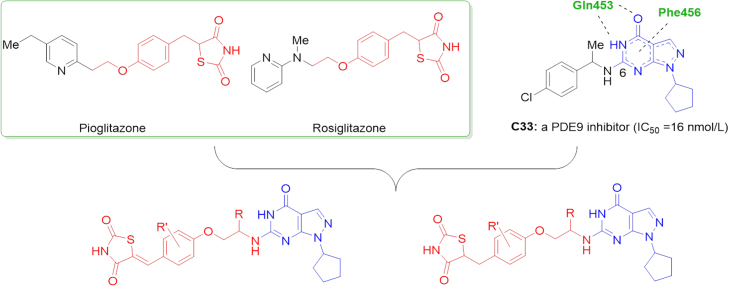

In order to discover novel PDE9 inhibitors starting from a previously studied hit C3323 (IC50 = 16 nmol/L, Fig. 1), a series of pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidinone derivatives containing the pharmacophore of rosiglitazone, were designed, synthesized, and bioassayed in this study. As a result, four of them have the IC50 less than 5 nmol/L. Compound 11a, has the best IC50 of 1.1 nmol/L against PDE9, which is significantly better than the reference compounds PF-04447943 (IC50 = 8 nmol/L)19 and BAY 73–6691 (IC50 = 48 nmol/L). The putative binding patterns and binding free energy analysis of these compounds with PDE9 by molecular modelling approaches may explain the structure—activity relationships and provide evidence for further structural modifications.

Figure 1.

Structure-based design of novel PDE9 inhibitors.

2. Result and discussion

2.1. Structure-based design of novel PDE9 inhibitors

Gln453 and Phe456 are two conservative amino acid residues in the binding site pocket of PDE9, the interactions with which are regarded to be important for the high-affinity PDE9 inhibitors. Most current PDE9 inhibitors contain a pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidinone scaffold to establish interactions with these residues via hydrogen bonds and π—π interactions23, 24, 25. Thus, in our newly designed compounds, the pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidinone scaffold was retained. Besides, a narrow and long pocket consisting of Leu420, Leu421, Tyr424, Phe441, Ala452, and Gln453 existed at the 6-position of this pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidinone ring, providing suitable space for introducing a fragment. Notably, the pharmacophore of rosiglitazone was attached on this position by using a 2-aminoethanol side chain to occupy the pocket (Fig. 1).

2.2. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation studies on the PDE9-designed compounds complexes

In order to decide which designed molecules should be synthesized and bioassayed, the putative binding modes and binding free energies of target compounds with PDE9 were predicted by using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation methods.

2.2.1. Validation of the molecular docking method

In order to validate the reliability of our molecular docking approach surflex-dock embedded in Tripos Sybyl X 2.0.26, the bound ligand 28s was extracted from the X-ray structure of PDE9 (PDB ID: 4GH6) and was redocked back into the same receptor with several docking conditions and scoring parameters. The RMSD value between the crystal pose and the top 15 poses for 28s was below 1.5 Å, indicating that the docking method and its parameters adopted were approximate and suitable for PDE9. Subsequently, all the designed compounds were docked into the same active site pocket of PDE9 with the same procedures used above to generate initial putative binding models for subsequent MD simulations.

2.2.2. Binding patterns of the designed compounds with PDE9 after MD simulations

After 8 ns MD simulations, all the PDE9-inhibitor complexes achieved stable MD trajectories. Based on the stable MD binding pattern (Fig. 2), compound 11a formed two hydrogen bonds with the residue Gln453 and π—π stacking interaction with Phe456 as expected. Besides, the fluorine atom possibly formed a hydrogen bond with Phe45627, which also enabled 2-fluoro phenyl ring to form the edge-face π—π interaction with Phe456. In addition to the π—π interactions and hydrogen-bonding interactions, hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions between residues Leu420, Tyr424, Phe441, Val417, Ala452, Phe459, Val460, Ile403, Met365, and Ala366 were also observed in the PDE9-11a complex.

Figure 2.

Putative binding pattern of the PDE9-11a complex after MD simulations.

Both compounds 11c and 11d adopted similar binding modes to compound 11a, forming two hydrogen bonds with Gln453 and strong π–π stacking interaction with Phe456. However, compound 11d lacking the fluoro group, did not form an additional hydrogen bond with Phe456, whereas 11c kept the hydrogen bond (Fig. 3A). For the compounds 14d and 15 with different R1 group on the side chain, both of them formed two hydrogen bonds with Gln453. The π–π stacking interactions against Phe456 were also observed. The main difference in the binding modes was that the 2,4-thiazolidinedione substituted phenyl ring stretched in different directions (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Superposition of binding patterns of compounds 11a, 11c, and 11d with PDE9. 11a in cyan color, 11c in yellow color, and 11d in blue color. (B) Superposition of binding patterns of compounds 14d and 15 with PDE9. 14d in pink color, 15 in yellow color.

The binding mode of rosiglitazone with PDE9A was also predicted (Supplementary Information Fig. S1). The 2,4-thiazolidinedione of Rosiglitazone formed three hydrogen bonds with Gln453, Glu406 and Ile403 in the binding pocket of PDE9A protein.

2.2.3. Binding free energy calculations of the designed compounds with PDE9

The predicted binding free energies ΔGbind,pred of designed compounds, hit compound C33 and Rosiglitazone were calculated by the molecular mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) method (Table 1). Almost all the designed compounds gave higher binding free energies than C33 and Rosiglitazone. Among these compounds, PDE9-5a, PDE9-5b, and PDE9-5c complexes possessed relatively high ΔGbind,pred values of −21.91, −20.75, and −22.60, respectively. In the series of compounds 11, 14 and 15 with 2,4-thiazolidinedione group substituted, the PDE9-11a complex gave the most negative ΔGbind,pred value whereas the PDE9-15 complex exhibited the most positive counterpart (PDE9-11a:−36.26 kcal/mol, PDE9-15: −24.67 kcal/mol, respectively). The ΔGbind,pred values of the PDE9-ligand complexes, such as 11a, 14a and 14c were more negative than these of the others, which implied that these compounds are supposed to be more potent than others. As a result, 12 compounds were retained and subjected to be synthesized and bioassayed.

Table 1.

Predicted binding free energies for the designed compounds with PDE9 by the MM-PBSA Method.

|

- not applicable.

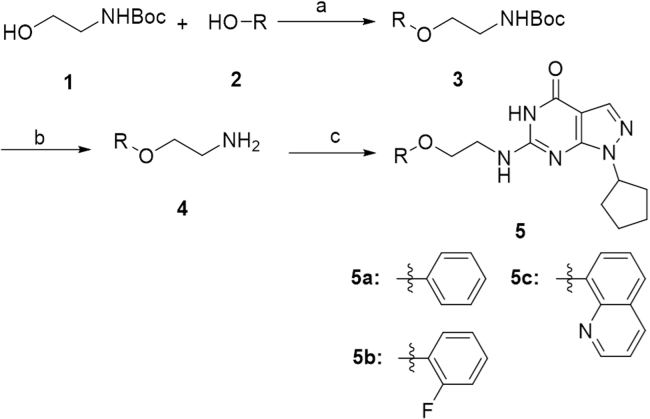

2.3. Synthesis of the designed compounds

The synthesis of the designed compounds 5a–5c is shown in Scheme 128. Firstly, the Boc-protected 2-aminoethanol (1) reacted with substituted phenol (2a–2c) under Mitsunobu-type reaction condition to afford compounds 3a–3c. The Boc groups of 3a–3c were deprotected with trifluoroacetic acid, providing the corresponding amine 4a–4c in quantitate yields, which were then reacted with 6-chloro-1-cyclopentyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-one to afford compounds 5a–5c23.

Scheme 1.

The synthesis of the designed compounds 5a–5c. Reagents and conditions: (a) PPh3, DIAD, THF, 0 °C to r.t., overnight; (b) TFA-DCM, 1:3, r.t., 0.5 h; (c) TEA, i-PrOH, reflux, overnight.

Scheme 2 shows the synthesis of 11a–d, 14a–d and 15. The Mitsunobu-type reaction between 2-substituted 4-hydroxylbenzaldehyde 7a–e and Boc-protected 2-aminoethanol 6a–6b afforded intermediate 8. A following Knoevenagel condensation of thiazolidine-2,4-dione with 8 gave the benzylidene 9. The intermediate 9 went into the same procedure as 3 to remove the Boc group and subsequently reacted with 6-chloro-1-cyclopentyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d] pyrimidin-4(5H)-one, providing compounds 11a–d in moderated yield. The configuration of the exocyclic C=C bond in compounds 11a–d were assigned to be “Z” on the basis of 1H NMR spectroscopy, in which the methine proton were detected at 7.70–7.79 ppm in 1H NMR spectra29, 30, 31, 32. On the other hand, the benzylidene carbon—carbon double bond of 9 was chemoselectively reduced with Mg to afford intermediates 12. After the removal of the Boc group of 12 in the presence of TFA, the resulting intermediate 13 reacted with 6-chloro-1-cyclopentyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-one to furnish the final products 14a–d and 15.

Scheme 2.

The synthesis of 11a–d, 14a–d and 15. Reagents and conditions: (a) PPh3, DIAD, THF, 0 °C to r.t., overnight; (b) thiazolidine-2,4-dione, piperidine, EtOH, reflux, overnight; (c) TFA-DCM (1:3), r.t., 0.5 h; (d) Mg, MeOH, r.t., 8 h; (e) TEA, i-PrOH, reflux, overnight.

2.4. Bioassay validations of the synthesized compounds towards PDE9 in vitro

2.4.1. Structure–activity relationship of these target compounds

Bioassay validations for the synthesized compounds were performed against PDE9 using the same procedure as we previously reported17. BAY 73-6691 serves as the reference compound for the bioassay with IC50 of 48 nmol/L, which is close to its literature value of 55 nmol/L. The results for the synthesized compounds were summarized in Table 2. Most of the designed compounds show more potent IC50 values than the starting hit C33 (16 nmol/L, Fig. 1). Rosiglitazone gave no inhibition against PDE9A even at the concentration of 5 mmol/L.

Table 2.

The IC50 values of compounds 5a–5c, 11a–11d, 14a–14d, and 15 against PDE9a.

|

aThe IC50 value of the reference compound Bay-73-6691 was 48 nmol/L in the current study.

bIC50 values are given as the mean of three independent determinations.

cIC50 values reported in our previous literature23.

dThe inhibition ratio of rosiglitazone against PDE9A at the concentration of 5 mmol/L.

- not applicable.

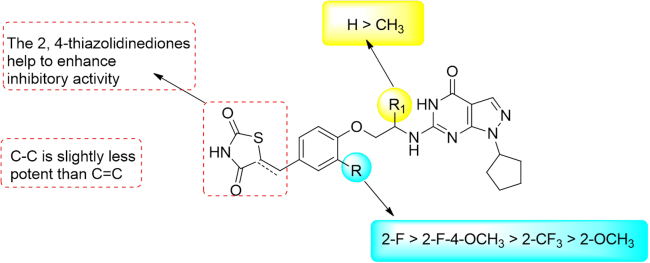

As is mentioned before, the pocket next to the 6-position of pyrimidinone scaffold is narrow and long23, 24, 25. Although a flexible ethyl amino side chain with small volume was used to attach the pharmacophore of rosiglitazone on the pyrimidinone scaffold, the volume of tail at this chain may affect compounds to suit this pocket significantly. Thus, compounds 5a—5c were designed and synthesized at the beginning in order to identify the capacity of this pocket. To our delighted, all of them gave remarkable inhibitory activities against PDE9 including compound 5c with quinoline as the tail. The IC50 values of compounds 5b and 5c were even higher than that of 5a, indicating that the substitution at the 2-position of phenyl ring might form additional interactions with residues in the pocket of PDE9.

Summary of the structure—activity relationships (SARs) for these compounds is depicted in Fig. 4. Compounds 11a–d and 14a–d were synthesized with the 2,4-thiazolidinediones attached on the phenyl ring with double or single carbon—carbon bond in the following modification. In the series of compounds 11a–d, the IC50 values ranged from 1.1 to 76 nmol/L. Compound 11a with 2-fluoro on the phenyl ring gave the best IC50 of 1.1 nmol/L, which is 8- and 48-fold potent than those of PF-04447943 and BAY 73-6691, respectively. Compared with compound 5b, the IC50 of 11a increased 20 fold, indicating that the 2,4-thiazolidinediones enhanced the affinity of compounds with PDE9. Furthermore, in order to identify our speculation that the substitution at the 2-position of phenyl ring might form additional interactions with PDE9A, 11b with 2-trifluoromethyl, 11c with 2-fluoro-6-methoxy, and 11d with 2-methoxy groups substituted on the phenyl ring were synthesized and evaluated. All of them gave better inhibitory potencies than compound 5a–5c except 11d. Since the volume of 2,4-thiazolidinedione-phenyl ring in 11c is larger than that of 11d, we concluded that the interactions formed by fluorine atom with PDE9, instead of steric hindrance, should be the main reason for the enhanced inhibitory activities of these compounds. The alternation of carbon–carbon double bonds of compounds 11a–c to form compounds 14a–c with carbon—carbon single bonds, caused slight decrease in inhibitory activities (11 vs 14), the IC50 of which ranged from 3.5 to 8.8 nmol/L.

Figure 4.

Summary of the structure—activity relationships of PDE9 inhibitors.

Compound 15 with a methyl group at the R1 position was also synthesized and evaluated to explore the effect of linkers with different volumes. Compared with 14d, the IC50 of compound 15 dropped to 98 nmol/L. Combining the results of compounds 5a–5c, we speculated that the substitutions on the R position affect the spatial orientation of the side chain, so that the side chain cannot fit the pocket well.

2.4.2. The experimental measurements for the IC50 values are consistent with ΔGbind,pred as expected

Among these targeted compounds, 11a exhibited the best potency with the IC50 value of 1.1 nmol/L, which also showed the most negative predicted binding free energy ΔGbind,pred (−36.26 kcal/mol). The |ΔGbind,pred| values of the PDE9-11a, PDE9-11c, PDE9-14a, and PDE9-14c complexes were higher than those of the others, while the IC50 of these compounds against PDE9 were better than others (below 5 nmol/L). As we expected, the biological affinities of the PDE9-ligand complexes correlate well with their ΔGbind,pred values.

The ΔGbind,pred values were −36.26 and −24.67 kcal/mol for the PDE9-11a and PDE9-15 complexes, respectively, which may account for their differences in the IC50 values (1.1 and 98 nmol/L). Compared with compound 11a, the inhibitory activity of compound 11c almost remained unchanged while 11d dropped with the IC50 of 76 nmol/L. The predicated binding mode of the PDE9A-11c complex validated our speculation that the steric hindrance of the substitution is not the main reason for the dropped affinity with PDE9 (Fig. 3A). Both compounds 11c and 11d adopted similar binding modes to 11a. Two hydrogen bonds with Gln453 and π—π stacking with Phe456 are formed by all of them; however, compound 11d lacking the fluoro group, did not form additional hydrogen bond with Phe456. This is coincided with the decreasing affinity of 11d with PDE9.

2.4.3. A significantly linear relationship was achieved between ΔGbind,exp and ΔGbind,pred

A significantly linear correlation is achieved (Fig. 5) with a conventional regression coefficient (R2 = 0.8379) based on ΔGbind,pred and ΔGbind,exp, which are approximately estimated from the in vitro IC50 values (via ΔGbind,exp ≈ RTlnIC50) for nine PDE9 inhibitor complexes with similar functional groups. This statistically significant relationship suggests that the ΔGbind,pred values for the PDE9 inhibitor complexes via binding free energy prediction after MD simulations can be used to prognosticate the experimental inhibitory potencies for newly designed PDE9 inhibitors with a similar scaffold. Since the entropic contribution to the binding free energy was ignored due to huge computational consumption, the ΔGbind,pred values were more negative than those (ΔGbind,exp) approximately estimated from the experimental IC50 values (Table 2). However, it is still meaningful to compare their relative magnitudes, which is common in the literature33, 34, 35.

Figure 5.

The correlation between predicted binding free energies and experimental binding free energies for nine compounds with 2, 4-thiazolidinedione (11a–11d, 14a–14d and 15).

2.4.4. Binding free energy decomposition

Table 3 lists the ΔGbind,pred values predicted by MM-PBSA and the decomposition of energy terms to the PDE9-11a and PDE9-15 complexes, which were calculated by averaging over 100 snapshots for the finial 1.0 ns (every 10 ps) MD simulations. Obviously, the ΔGele, ΔGvdw, and ΔGele,solc components make the major contributions to the total binding free energy. The energy terms for van der Waals interactions (ΔGvdw) and polar contribution to solvation (ΔGele,sol) of the PDE9-11a complex are 4.1 and 5.4 kcal/mol lower than those for the PDE9-15 complex. We speculated that the van der Waals interactions might play an important role for the enhanced inhibition activity as well as the polar contribution.

Table 3.

Components of the predicted binding free energies from their trajectories for binding of 11a or 15 to PDE9 by the MM-PBSA method.

| Energy terms (kcal/mol) | 11a | 15 |

|---|---|---|

| ΔGelea | −23.54±3.47 | −21.87±4.21 |

| ΔGvdwb | −53.89±3.90 | −49.84±3.09 |

| ΔGnonpol,solc | −7.05±0.18 | −6.58±0.25 |

| ΔGele,sold | 48.22±5.84 | 53.63±5.98 |

| ΔGbind,prede | −36.26±5.49 | −24.67±4.99 |

Electrostatic interactions calculated by using the MM force field.

van der Waals' contributions from MM.

Nonpolar contribution to solvation.

Polar contribution to solvation.

ΔGbind,pred = ΔGele + ΔGvdw + ΔGnonpol,sol + ΔGele,sol, predicted binding free energies in the absence of entropic contribution.

To further evaluate the effects of energy on the contributions of each residue in the binding-site pocket, residue-based energy decomposition for the binding free energies between the ligands and PDE9A was conducted by use of the MM-PBSA method. Fig. 6 shows the energy decomposition for key residues in the two complexes (11a-PDE9A and 15-PDE9A).

Figure 6.

Decomposition of the key residue contributions to the binding free energies for the complexes of PDE9 with 11a and 15.

Generally, if the interaction energy between a ligand and a residue is lower than −1 kcal/mol, the residue is viewed to be important in the molecular recognition of ligands. Our results suggested that the following residues might be important for inhibitory activities of 11a and 15 on PDE9: Phe456 (−5.2 and −4.5 kcal/mol), Gln453 (−4.4 and −4.3 kcal/mol), Leu420 (−2.4 and −2.2 kcal/mol), Ile403 (−1.9 and −2.0 kcal/mol), Tyr424 (−1.8 and −1.4 kcal/mol), Met365 (−1.3 and −1.0 kcal/mol), Val460 (−1.3 and −0.3 kcal/mol), Phe441 (−1.2 and −2.4 kcal/mol) and Phe459 (−1.1 and −0.2 kcal/mol). Among these residues, Phe456 and Gln453 contributed most to the total binding free energies, in consistence with the binding patterns that all the ligands formed π–π stacking with Phe456 and hydrogen bonds with Gln453. Phe456, Phe459 and Val460 in the hydrophobic pocket made the major difference in energy contribution. Phe456, Phe459 and Val460 contribute to the PDE9-11a complex with the binding free energies of 0.7, 0.9 and 1.0 kcal/mol lower than those of PDE9-15, which is consistent with the binging modes that the 2,4-thiazolidinedione substituted phenyl ring stretched in different position (Supplementary Information Fig. S2). Additionally, 11a involves hydrophobic interactions with the adjacent residues Leu420, Ile403, Tyr424, Met365, Val460, Phe441, and Phe459, which achieves more than 1 kcal/mol enhancement of the energy favorable to the total binding free energy. And all of these involve van der Waals contacts with 11a. This might be the reason why the ΔGvdw term for 11a is −53.89 kcal/mol.

2.5. Effects of synthesized compounds on the cell viability

Compounds 11a, 11c, 14a, and 14c with IC50 against PDE9 below 5 nmol/L were subjected to MTT assay by using the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y to examine the cytotoxic effects36. The cell viabilities of compound 11a (PDE9 IC50: 1.1 nmol/L) at the concentration of 100 and 40 μmol/L were 34% and 55%, respectively. The cell viabilities of compound 11c (PDE9 IC50: 3.3 nmol/L) at the concentration of 100 and 40 μmol/L were 57% and 84%, respectively. The cell viabilities of compound 14a (PDE9 IC50: 3.5 nmol/L) at the concentration of 100 and 40 μmol/L were 52% and 82%, respectively. The cell viabilities of compound 14c (PDE9 IC50: 4.2 nmol/L) at the concentration of 100 and 40 μmol/L were 62% and 93%, respectively. These results (Fig. 7) indicated that all these compounds were almost nontoxic and suitable for further in vivo exploration.

Figure 7.

Cell viability of compounds 11a, 11c, 14a, and 14c by using human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y.

3. Conclusions

In summary, a series of novel PDE9 inhibitors have been rationally designed, synthesized, and evaluated. Four of the designed compounds have the IC50 below 5 nmol/L, which also showed low toxicity to SH-SY5Y cells. Compound 11a had the best potency to inhibit PDE9 with the IC50 of 1.1 nmol/L, which is 8- and 48-fold more potent than the candidates PF-04447943 and BAY 73-6691, respectively. The bioassay results were in accordance with binding free energy analysis results as expected, providing evidences for further structural modification.

4. Experimental section

All the starting materials and reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used directly without further purification. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel (200–300 mesh) purchased from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd. Thin-layer chromatography was performed on precoated silica gel F-254 plates (0.25 mm, Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd.) and was visualized with UV light. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a BrukerBioSpin GmbH spectrometer at 400.1 and 100.6 MHz, respectively. Coupling constants are given in Hz. MS spectra were obtained on an Agilent LC–MS 6120 instrument. The purity of tested compounds was determined by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. HPLC instrument: SHIMADZU LC-20AT (column: Hypersil BDS C18, 5.0 μm, 150 mm × 4.6 mm (Elite); Detector: SPD-20A UV/VIS detector, UV detection at 254 nm; Elution, MeOH in water (70%, v/v); T = 25 °C; and flow rate = 1.0 mL/min. High-resolution mass spectra (HR-MS) were obtained on a LT-TOF.

4.1. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 3a–3c28

tert-Butyl(2-hydroxyethyl)carbamate 1 (0.65 g, 4.0 mmol), substituted 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde 2a–2c (4.0 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (1.6 g, 6.0 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous THF (40 mL). The mixture was cool to 0 °C. DIAD (1.2 mL, 6.0 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. After the reaction was finished, the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate three times and washed with saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution. The organic layer was collected, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, concentrated under vacuum and purified by silica column chromatography to afford 3a–3c as colorless oil.

4.1.1. tert-Butyl(2-phenoxyethyl)carbamate (3a)

Colorless oil, Yield 67%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ 7.27 (m, 3H), 6.97 (m, 1H), 6.87 (m, 2H), 4.02 (t, 2H, J= 9.3 Hz), 3.52 (m, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H).

4.1.2. tert-Butyl(2-(2-fluorophenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (3b)

Colorless oil, Yield 64%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ 7.05 (m, 3H), 6.91 (m, 1H), 6.21 (s, 1H), 4.24 (m, 2H), 3.92 (m, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

4.1.3. tert-Butyl(2-(quinolin-8-yloxy)ethyl)carbamate (3c)

Colorless oil, Yield 78%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.88 (dd, J = 4.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (m, 3H), 7.08 (m, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 4.26 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (dd, J = 10.1, 5.1 Hz, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

4.2. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 5a–5c24, 28

Compounds 3a–3c (0.30 mmol) was dissolved in 25% TFA in dichloromethane (2.0 mL). The mixture was then stirred at ambient temperature for 0.5 h. The solvent was removed by evaporation and the residue was washed with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (2:1, v/v), and evaporated again. The resulting product 4a–4c was directly used for the next reaction step without further purification. To a sealed tube were added isopropanol (2.5 mL), 6-chloro-1-cyclopentyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-one (0.25 mmol), 4a–4c (0.30 mmol), and triethylamine (76 mg, 0.75 mmol). The reaction mixture was reflux overnight. The solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by silica column chromatography to provide the final product 5a–5c as white solids.

4.2.1. 1-Cyclopentyl-6-((2-phenoxyethyl)amino)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-one (5a)

White solid, Yield: 46%; Purity: 98%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.96 (s, 1H), 7.79 (s, 1H), 7.14 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 6.82 (m, 3H), 6.60 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.93 (p, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (dd, J = 10.6, 5.2 Hz, 2H), 2.01 (m, 4H), 1.87 (m, 2H), 1.63 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.60, 158.48, 154.37, 152.93, 134.31, 129.48, 121.14, 114.64, 99.91, 66.24, 57.41, 40.51, 32.06, 24.83. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C18H21N5O2 340.1768, Found 340.1763.

4.2.2. 1-Cyclopentyl-6-((2-(2-fluorophenoxy)ethyl)amino)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-one (5b)

White solid, Yield: 51%; Purity: 97%;1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.23 (s, 1H), 7.88 (s, 1H), 7.05 (m, 3H), 6.91 (m, 1H), 6.21 (s, 1H), 5.01 (dt, J = 15.2, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 4.26 (m, 2H), 3.90 (m, 2H), 2.08 (m, 4H), 1.95 (m, 2H), 1.72 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.71, 154.26, 152.82, 134.36, 124.32, 124.29, 121.92, 121.85, 116.50, 116.32, 115.79, 99.97, 68.05, 57.39, 40.49, 32.02, 24.80. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C18H20N5O2F 358.1674, Found 358.1657.

4.2.3. 1-Cyclopentyl-6-((2-(quinolin-8-yloxy)ethyl)amino)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-one (5c)

White solid, Yield: 58%; Purity: 97%;1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.97 (s, 1H), 8.76 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (m, 2H), 7.36 (m, 3H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (m, 1H), 4.34 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 4.01 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 2H), 2.07 (m, 4H), 1.93 (m, 2H), 1.70 (m, 2H).13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.57, 154.23, 153.95, 152.84, 148.63, 139.49, 136.51, 134.37, 129.46, 126.82, 121.73, 120.04, 109.15, 99.92, 67.28, 57.19, 40.14, 32.03, 24.82. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C21H22N6O2 391.1877, Found 391.1833.

4.3. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 8a—8f

tert-Butyl(2-hydroxyethyl)carbamate 6a–6b (4.0 mmol), substituted 4-hydroxy-2-formylbenzaldehyde 7a–7d (4.0 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (1.6 g, 6.0 mmol) were dissolved in anhydrous THF (40 mL). The mixture was cool to 0 °C. DIAD (1.2 mL, 6.0 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred overnight at ambient temperature. After the reaction was finished, the mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate three times and washed with saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution. The organic layer was collected, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, concentrated under vacuum and purified by silica column chromatography to afford 8a–8f as colorless oil.

4.3.1. tert-Butyl(2-(2-fluoro-4-formylphenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (8a)

Colorless oil, Yield 63%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.87 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (m, 2H), 7.09 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 5.09 (s, 1H), 4.19 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H), 3.61 (dd, J = 10.9, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 1.47 (s, 9H).

4.3.2. tert-Butyl(2-(4-formyl-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (8b)

Colorless oil, Yield 60%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.93 (s, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (s, 1H), 4.22 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.61 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H).

4.3.3. tert-Butyl(2-(2-fluoro-4-formyl-6-methoxyphenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (8c)

Colorless oil, Yield 55%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.86 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (m, 2H), 5.36 (s, 1H), 4.23 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.97 (s, 3H), 3.48 (dd, J = 10.3, 5.2 Hz, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

4.3.4. tert-Butyl(2-(4-formyl-2-methoxyphenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (8d)

Colorless oil, Yield 68%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.61 (s, 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.3, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.10 (s, 1H), 3.98 (s, 3H), 4.10 (m, 2H), 3.54 (m, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

4.3.5. tert-Butyl(2-(4-formylphenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (8e)

Colorless oil, Yield 63%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.89 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (m, 2 H), 7.01 (m, 3H), 4.12 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 3.58 (s, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

4.3.6. tert-Butyl(1-(4-formylphenoxy)propan-2-yl)carbamate (8f)

Colorless oil, Yield 51%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.90 (s, 1H), 7.87–7.85 (m, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.06–7.03 (m, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.77 (s, 1H), 4.05 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 1.47 (s, 9H), 1.32 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H).

4.4. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 9a–9f

To a solution of 8a–8f (1.5 mmol) and 2,4-thiazolidinedione (0.19 g, 1.6 mmol) in anhydrous ethanol (6.0 mL) were added piperidine (45 μL, 0.45 mmol). The reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 12 h. The mixture was concentrated under vacuum and purified by silica column chromatography to yield 9a–9f as a white solid.

4.4.1. (Z)-tert-Butyl(2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)methyl)-2-fluorophenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (9a)

White solid, Yield 68%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.57 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.49 (dd, J = 12.5, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (m, 2H), 7.01 (s, 1H), 4.13 (m, 2H), 3.33 (m, 2H), 1.38 (s, 9H).

4.4.2. (Z)-tert-Butyl(2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)methyl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (9b)

Yellow solid, Yield 66%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.64 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.19 (m, 2H), 3.60 (m, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H).

4.4.3. (Z)-tert-Butyl(2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)methyl)-2-fluoro-6-methoxyphenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (9c)

White solid, Yield 49%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.64 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.10 (dd, J = 15.5, 4.3Hz, 2H), 6.82 (s, 1H), 4.04 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.23 (dd, J = 11.7, 5.9 Hz, 2H), 1.37 (s, 9H).

4.4.4. (Z)-tert-Butyl(2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)methyl)-2-methoxyphenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (9d)

Yellow solid, Yield 70%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.82 (s, 1H), 7.09 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.10 (s, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.88 (m, 2H), 3.43 (m, 2H), 1.40 (s, 9H).

4.4.5. (Z)-tert-Butyl (2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)methyl)phenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (9e)

White solid, Yield 47%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.09 (m, 2H), 4.10 (m, 2H), 3.47 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

4.4.6. (Z)-tert-Butyl(1-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-ylidene)methyl)phenoxy)propan-2-yl)carbamate (9f)

White solid, Yield 72%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.23 (s, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 4.01 (s, 2H), 1.71 (s, 1H), 1.49 (s, 9H), 1.32 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H).

4.5. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 11a–11d

Compound 9a–d (0.30 mmol) was dissolved in 25% TFA in dichloromethane (2.0 mL). The mixture was then stirred at ambient temperature for 0.5 h. The solvent was removed by evaporation and the residue was washed with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (2:1, v/v), and evaporated again. The resulting product 10a–10d was directly used for the next reaction step without further purification. To a 10 mL of sealed vial were added isopropanol (2.5 mL), 6-chloro-1-cyclopentyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-one (0.25 mmol), 10a–10d (0.30 mmol), and triethylamine (76 mg, 0.75 mmol). The reaction mixture was reflux overnight. The solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by silica column chromatography to provide the final product 11a–11d as white solids.

4.5.1. (Z)-5-(4-(2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)amino)ethoxy)-3-fluorobenzylidene)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (11a)

White solid, Yield 33%; Purity: 98%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.58 (s, 1H), 10.53 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (m, 2H), 6.74 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.88 (m, 1H), 4.33 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (dd, J = 10.8, 5.3 Hz, 2H), 1.99 (m, 2H), 1.91 (m, 2H), 1.83 (m, 2H), 1.62 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.26, 167.96, 158.24, 153.87, 153.75, 148.42, 148.31, 134.35, 130.98, 127.37, 126.82, 122.82, 118.27, 118.07, 115.77, 100.25, 67.83, 56.98, 32.18, 24.78. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C22H21N6O4FS 485.1402, Found 485.1383.

4.5.2. (Z)-5-(4-(2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-ylamino)ethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzylidene)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (11b)

White solid, Yield 40%; Purity: 93%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.64 (s, 1H), 10.67 (s, 1H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.83 (m, 2 H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (dd, J = 14.5, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (dd, J = 10.9, 5.2 Hz, 2H), 1.95 (m, 2H), 1.88 (m, 2H), 1.81 (m, 2H), 1.59 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, Acetone) δ 168.11, 166.81, 157.83, 153.72, 153.30, 135.15, 133.72, 130.31, 129.29, 129.24, 129.19, 126.02, 123.01, 122.98, 114.39, 100.30, 67.67, 57.08, 39.92, 31.79, 24.52. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C23H21N6O4F3S 531.1370, Found 531.1355.

4.5.3. (Z)-5-(4-(2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)amino)ethoxy)-3-fluoro-5-methoxybenzylidene)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (11c)

White solid, Yield 31%; Purity: 95%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.63 (s, 1H), 10.58 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 2H), 7.11 (m, 1 H), 6.63 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.84 (dd, J = 14.3, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 3.64 (dd, J = 11.0, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 1.97 (m, 2H), 1.90 (m, 2H), 1.82 (m, 2H), 1.60 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.16, 166.19, 158.26, 154.44, 154.41, 154.30, 153.88, 153.73, 153.71, 134.33, 131.02, 111.48, 110.86, 100.23, 72.24, 57.01, 56.88, 32.15, 24.79. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C23H23N6O5FS 515.1507, Found 515.1496.

4.5.4. (Z)-5-(4-(2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)amino)ethoxy)-3-methoxybenzylidene)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (11d)

Yellow solid, Yield 25%; Purity: 95%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.61 (s, 1H), 9.95 (s, 1H), 7.79 (s, 1H), 7.68 (s, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 4.86 (m, 1H), 3.88 (m, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 3.63 (dd, J = 10.1, 5.5 Hz, 2H), 1.94 (m, 2H), 1.85 (m, 2H), 1.78 (m, 2H), 1.58 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 168.10, 166.42, 158.35, 153.96, 153.92, 151.94, 150.09, 148.47, 134.21, 133.82, 124.81, 124.71, 117.51, 116.71, 114.68, 100.16, 56.89, 56.14, 32.16, 24.70. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C23H24N6O5S 497.1602, Found 497.1585.

4.6. General procedure for the synthesis of compound 12a–12c, 12e and 12f

Magnesium (0.48 g, 20 mmol) was added to a solution of 9a–c, 9e and 9f (0.36 g, 1.0 mmol) in anhydrous methanol (10 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 8 h. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was quenched by adding saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layers and extracts were combined, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated in vacuo to afford 12a–12c, 12e and 12f as white solids.

4.6.1. tert-Butyl(2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-yl)methyl)-2-fluorophenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (12a)

White solid, Yield 95%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.07 (m, 2H), 6.97 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 4.57 (dd, J = 9.4, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.01 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 3.33 (m, 3H), 2.90 (dd, J = 14.2, 9.5 Hz, 1H), 1.39 (s, 9H).

4.6.2. tert-Butyl(2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-yl)methyl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (12b)

White solid, Yield 84%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.51 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.10 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.56 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.47 (dd, J = 14.3, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.15 (dd, J = 14.3, 9.2 Hz, 1H), 1.44 (s, 9H).

4.6.3. tert-Butyl(2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-yl)methyl)-2-fluoro-6-methoxyphenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (12c)

Light yellow solid, Yield 78%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.61 (m, 3H), 4.48 (dd, J = 9.5, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 4.09 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.41 (m, 3H), 3.08 (dd, J = 13.9, 9.8 Hz, 1H), 1.45 (s, 9H).

4.6.4. tert-Butyl(2-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-yl)methyl)phenoxy)ethyl)carbamate (12e)

White solid, Yield 76%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.85 (s, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.03 (s, 1H), 4.49 (dd, J = 9.4, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.53 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 3.45 (dd, J = 14.2, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 14.2, 9.5 Hz, 1H), 1.45 (s, 9H).

4.6.5. tert-Butyl(1-(4-((2,4-dioxothiazolidin-5-yl)methyl)phenoxy)propan-2-yl)carbamate(12f)

White solid, Yield 65%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.14 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.85 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.47 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (s, 2H), 3.44 (dd, J = 14.2, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.11 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1H), 1.45 (s, 9H), 1.28 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H).

4.7. General procedure for the synthesis of compound 14a—14d, 15

Compounds 12a–12f (0.30 mmol) was dissolved in 25% TFA in dichloromethane (2.0 mL). The mixture was then stirred at ambient temperature for 0.5 h. The solvent was removed by evaporation and the residue was washed with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (2:1, v/v), and evaporated again. The resulting product 13a–13f was directly used for the next reaction step without further purification. To a 10 mL of sealed vial were added isopropanol (2.5 mL), 6-chloro-1-cyclopentyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4(5H)-one (0.25 mmol), 13a–13f (0.30 mmol), and triethylamine (76 mg, 0.75 mmol). The reaction mixture was reflux overnight. The solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by silica column chromatography to provide the final product 14a–14d and 15.

4.7.1. 5-(4-(2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)amino)ethoxy)-3-fluorobenzyl)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (14a)

Light yellow solid, Yield 38%; Purity: 96%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.01 (s, 1H), 10.50 (s, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.18 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (dd, J = 12.5, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.91 (m, 2H), 4.21 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.72 (dd, J = 11.2, 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.34 (m, 1H), 3.09 (m, 1H), 2.00 (m, 2H), 1.92 (m, 2H), 1.83 (m, 2H), 1.63 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.13, 172.10, 158.21, 153.90, 153.74, 150.43, 145.65, 145.54, 134.37, 130.55, 126.02, 117.47, 115.26, 100.25, 67.53, 57.02, 53.05, 36.49, 32.20, 24.80. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C22H23N6O4FS 487.1558, Found 487.1541.

4.7.2. 5-(4-(2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)amino)ethoxy)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (14b)

White solid, Yield 35%; Purity: 98%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.04 (s, 1H), 10.64 (s, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (m, 1H), 4.93 (m, 2H), 4.27 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.73 (dd, J = 10.6, 5.1 Hz, 2H), 3.39 (m, 1H), 3.20 (m, 1H), 1.99 (m, 2H), 1.91 (m, 2H), 1.82 (m 2H), 1.62 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.10, 171.99, 158.29, 155.68, 153.90, 153.79, 135.52, 134.30, 129.28, 128.21, 128.16, 117.23, 114.18, 100.26, 67.51, 57.07, 52.94, 36.13, 32.15, 24.78. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C23H23N6O4F3S 537.1526, Found 537.1528.

4.7.3. 5-(4-(2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)amino)ethoxy)-3-fluoro-5-methoxybenzyl)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (14c)

Light yellow solid, Yield 35%; Purity: 96%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.06 (s, 1H), 10.59 (s, 1H), 7.74 (s, 1H), 6.82 (s, 1H), 6.77 (dd, J = 11.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (m, 2H), 4.11 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.61 (dd, J = 11.0, 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.37 (m, 1H), 3.04 (m, 1H), 1.99 (m, 2H), 1.90 (m, 2H), 1.82 (m, 2H), 1.63 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.31, 172.23, 158.27, 157.06, 156.86, 154.36, 153.93, 153.88, 153.73, 134.33, 115.27, 109.98, 109.46, 100.22, 72.07, 57.03, 56.67, 52.92, 37.58, 32.16, 24.79. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C23H25N6O5FS 517.1664, Found 517.1652.

4.7.4. 5-(4-(2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)amino)ethoxy)benzyl)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (14d)

White solid, Yield 64%; Purity: 95%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 5.04 (m, 1H), 4.66 (dd, J = 8.8, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.81 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H), 3.37 (dd, J = 14.2, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 3.09 (dd, J = 14.2, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.06 (m, 4H), 1.94 (dd, J = 9.1, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 1.72 (m, 2H).13C NMR (101 MHz, Acetone) δ 205.32, 205.26, 158.05, 153.32, 133.75, 130.55, 129.68, 129.06, 114.51, 100.23, 66.17, 57.03, 53.30, 40.27, 36.95, 31.82, 31.75, 26.89, 24.53, 22.45, 13.48. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C22H24N6O4S 469.1653, Found 469.1652.

4.7.5. 5-(4-((S)-2-((1-Cyclopentyl-4-oxo-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)amino)propoxy)benzyl)thiazolidine-2,4-dione (15)

White solid, Yield 71%; Purity: 95%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.37 (s, 1H), 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.79 (s, 1H), 4.97–4.87 (m, 1H), 4.79 (dd, J = 9.0, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 4.39–4.29 (m, 1H), 4.10 (dd, J = 9.8, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (dd, J = 9.7, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 3.03 (dd, J = 14.1, 9.1 Hz, 1H), 1.97 (ddd, J = 17.5, 9.5, 5.3 Hz, 4H), 1.88–1.80 (m, 2H), 1.69–1.61 (m, 2H), 1.29 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 158.11, 157.83, 153.94, 153.19, 134.33, 130.81, 129.74, 114.91, 100.25, 70.47, 57.16, 54.15, 45.91, 37.02, 32.20, 32.15, 24.81, 17.62. HR-MS (ESI-TOF) m/z [M + H]+ Calcd. for C23H26N6O4S 483.1809, Found 483.1807.

4.8. In vitro bioassay test for the inhibition of PDE9

The PDE9A2 protein was purified by the protocols according to our previous reports24, 33. 3H-cGMP was the substrate for the biological test against PDE9A2. 3H-cGMP was diluted with the assay buffer, which contained 20−50 mmol/L Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1 mmol/L DTT to 20,000–30,000 cpm per assay. The reaction was performed at 25 °C for 15 min and was terminated by the addition of 0.2 mol/L ZnSO4. After the addition of 0.1 mol/L Ba(OH)2, a precipitate was formed, and the unreacted 3H-cGMP was left in the supernatant. The radioactivity in the supernatant was measured in 2.5 mL of Ultima Gold liquid scintillation cocktail (PerkinElmer) using a PerkinElmer 2910 liquid scintillation counter. For the measurement of IC50 of inhibitors, eight different concentrations were used, and each measurement was repeated three times. The IC50 values against PDE9 were calculated by nonlinear regression. The mean values of the measurements were considered as the final IC50 values with the SD values of the measurements.

4.9. In vitro assay for inhibition of the lead compounds on PDE1B, PDE4D, PDE7A and PDE8A

The catalytic domains of PDE1B (10-487), PDE2A (580-919), PDE4D (86-413), PDE7A (130-482) and PDE8A (480-820) were purified with the published protocol37, 38, 39, 40, 41. The enzymatic activities of PDE1B and PDE8A were assayed by using 3H-cGMP and 3H-cAMP as the substrates respectively, following the same procedure for PDE9A.

4.10. In vitro cell viability assay

SH-SY5Y cells were used for the cytotoxicity test by using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) method42. The SH-SY5Y cells (5 × 103) were inoculated into a 96-well plate. After 24 h, compoundsat concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 μmol/L, were added. After incubation for 48 h, MTT solution was added to each cell well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. After the purpleformazan dye was dissolved, 100 μL of DMSO was added to the cells. The absorbance of each cell well was measured at 570 nm using FlexStation 3 (Molecular Devices).

4.11. Molecular docking and MD simulations for PDE9A

The X-ray crystal structure of 28s-PDE9A complex (PDB ID: 4GH6) reported in our previous studies25 was selected for molecular modeling, and Surflex-dock26 embedded in the software Tripos Sybyl 2.0 was used. Two metal ions crucial for the PDE's catalytic activity in the catalytic domain and water molecules coordinate these two metal ions were retained. Hydrogen atoms were added, and the ionizable residues were protonated at the neutral pH. The protomol, was generated using the parameters by default. The parameters of proto_thresh and proto_bloat were assigned 0.5 and 0, respectively. After the protomol was the prepared, molecular docking was performed for test molecules.

After molecular docking completed, similar MD simulation procedures as previous studies33 were used to equilibrate the whole system. Here 8 ns MD simulations were carried out in the NPT ensemble with a constant pressure of 1 atm and a constant temperature of 300 K. The periodic boundary conditions were adopted, along with an 8 Å cutoff for long-range electrostatic interactions with the partial mesh Ewald (PME) method43, 44. The SHAKE algorithm45, 46 was utilized to deal with all bonds involving hydrogen atoms, and hence the time step was set to 2 fs. An Intel Xeon E5620 CPU and an NVIDIA Tesla C2050 GPU, which are available in performing floating-point calculations, were applied to accelerate the process of MD simulations for each system. Subsequently, the 100 snapshots were isolated from the final 1.0 ns period of the MD simulation trajectories, and then used for binding-free-energy calculations by the MM-PBSA approach34, 35, 36, 47. For the electrostatic contribution to the solvation-free energy, the PBSA program in the Amber 1648 suite was used, which could numerically solves the Poissone Boltzmann Eqs.

In light of the MM-PBSA method, the binding free energy (ΔGbind) can be calculated by the following Eq. (1), where Gcomplex, Grec and Glig represent the free energies of complex, receptor and ligand, respectively.

| (1) |

Each free energy was evaluated as the sum of the MM energy EMM, the solvation free energy Gsolv, and the entropy contribution S, respectively, leading to Eq. (2).

| (2) |

ΔEMM is the gas phase interaction energy, which can be decomposed into EMM,comp, EMM,rec and EMM,lig. Solvation free energy is evaluated by the sum of the electrostatic solvation free energy (ΔGPB) and nonpolar solvation free energy (ΔGnp), leading to Eq. (3).

| (3) |

ΔGPB was calculated by the Poisson Boltzmann (PB) Eq, whereas ΔGnp was determined by use of Eq. (4). The default parameters were adopted, with γ = 0.0072 kcal/(Å2) and b = 0 kcal/mol.

| (4) |

In order to get the compromise between efficiency and accuracy, entropy contribution term (−TΔS) was omitted for ΔGbind in Eq. (2), since the calculations of the entropy contribution is extremely time-consuming for large protein-ligand systems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFB0202600), Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81522041, 81373258, 21572279, 81602955, and 21402243), Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Nos. 2014A020210009, 2016A030310144), The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Sun Yat-Sen University, No. 17ykjc03 and 17ykpy20), Guangdong Province Higher Vocational Colleges & Schools Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2016). We thank Special Program for Applied Research on Super Computation of the NSFC-Guangdong Joint Fund (the second phase) under Grant No. U1501501 for providing the supercomputing service. We cordially thank Prof. Hengming Ke from Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, for his help with molecular cloning, expression, purification, crystal structure, and bioassay of PDEs.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2017.12.007.

Contributor Information

Yinuo Wu, Email: wyinuo3@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Hai-Bin Luo, Email: luohb77@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Stopschinski B.E., Diamond M.I. The prion model for progression and diversity of neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:323–332. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2015. Available from: 〈http://news.medlive.cn/uploadfile/20150902/14411602338388.pdf〉.

- 3.Tahrani A.A., Bailey C.J., Del Prato S., Barnett A.H. Management of type 2 diabetes: new and future developments in treatment. Lancet. 2011;378:182–197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wild S., Roglic G., Green A., Sicree R., King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Exalto L.G., Whitmer R.A., Kappele L.J., Biessels G.J. An update on type 2 diabetes, vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:858–864. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X.H., Song D.L., Leng S.X. Link between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease: from epidemiology to mechanism and treatment. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:549–560. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S74042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L., Höelscher C. Common pathological processes in Alzheimer disease and type 2 diabetes: a review. Brain Res Rev. 2007;56:384–402. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domek-Łopacińska K.U., Strosznajder J.B. Cyclic GMP and nitric oxide synthase in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41:129–137. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eigenthaler M., Nolte C., Halbrügge M., Walter U. Concentration and regulation of cyclic nucleotides, cyclic-nucleotide-dependent protein kinases and one of their major substrates in human platelets. Estimating the rate of camp-regulated and cGMP-regulated protein phosphorylation in intact cells. Eur J Biochem. 1992;205:471–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maurice D.H., Ke H., Ahmad F., Wang Y., Chung J., Manganiello V.C. Advances in targeting cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:290–314. doi: 10.1038/nrd4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aversa A., Vitale C., Volterrani M., Fabbri A., Spera G., Fini M. Chronic administration of sildenafil improves markers of endothelial function in men with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-Osta A., Cuadrado-Tejedor M., García-Barroso C., Oyarzábal J., Franco R. Phosphodiesterases as therapeutic targets for Alzheimer's disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:832–844. doi: 10.1021/cn3000907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conti M., Beavo J. Biochemistry and physiology of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: essential components in cyclic nucleotide signaling. Ann Rev Biochem. 2007;76:481–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.150444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fryburg DA, Gibbs EM. Treatment of insulin resistance syndrome and type 2 diabetes with PDE9 inhibitors. United States patent US 6967204. 2005.

- 15.Svenstrup N, Simonsen KB, Rasmussen LK, Juhl K, Langgard M, Wen K, et al. Substituted imidazo [1,5-a]pyrazines as PDE9 inhibitors. United States patent US 9643970. 2017.

- 16.Fryburg DA, Gibbs EM. Treatment of insulin resistance syndrome and type 2 diabetes with PDE9 inhibitors. European patent EP 1444009. 2004.

- 17.Shao Y.X., Huang M., Cuo W., Feng L.J., Wu Y., Cai Y. Discovery of a phosphodiesterase 9A inhibitor as a potential hypoglycemic agent. J Med Chem. 2014;57:10304–10313. doi: 10.1021/jm500836h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Der Staay F.J., Rutten K., Bärfacker L., DeVry J., Erb C., Heckroth H. The novel selective PDE9 inhibitor BAY 73-6691 improves learning and memory in rodents. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:908–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutson P.H., Finger E.N., Magliaro B.C., Smith S.M., Converso A., Sanderson P.E. The selective phosphodiesterase 9 (PDE9) inhibitor PF-04447943 (6-[(3S,4S)-4-methyl-1-(pyrimidin-2-ylmethyl)pyrrolidin-3-yl]-1-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)-1,5-dihydro-4H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-one) enhances synaptic plasticity and cognitive function in rodents. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Home P.D., Pocock S.J., Beck-Nielsen H., Curtis P.S., Gomis R., Hanefeld M. Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes in oral agent combination therapy for type 2 diabetes (record): a multicentre, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet. 2009;373:2125–2135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60953-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye J.P. Challenges in drug discovery for thiazolidinedione substitute. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2011;1:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon S.Y., Park J.S., Choi J.E., Choi J.M., Lee W.J., Kim S.W. Rosiglitazone reduces tau phosphorylation via JNK inhibition in the hippocampus of rats with type 2 diabetes and tau transfected SH-SY5Y cells. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang M., Shao Y., Hou J., Cui W., Liang B., Huang Y. Structural asymmetry of phosphodiesterase-9A and a unique pocket for selective binding of a potent enantiomeric inhibitor. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;88:836–845. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.099747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claffey M.M., Helal C.J., Verhoest P.R., Kang Z., Fors K.S., Jung S. Application of structure-based drug design and parallel chemistry to identify selective, brain penetrant, in vivo active phosphodiesterase 9A inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2012;55:9055–9068. doi: 10.1021/jm3009635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng F., Hou J., Shao Y.X., Wu P.Y., Huang M., Zhu X. Structure-based discovery of highly selective phosphodiesterase-9A inhibitors and implications for inhibitor design. J Med Chem. 2012;55:8549–8558. doi: 10.1021/jm301189c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain A.N. Surflex: fully automatic flexible molecular docking using a molecular similarity-based search engine. J Med Chem. 2003;46:499–511. doi: 10.1021/jm020406h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider H.J. Hydrogen bonds with fluorine. Studies in solution, in gas phase and by computations, conflicting conclusions from crystallographic analyses. Chem Sci. 2012;3:1381–1394. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung K.Y., Samadani R., Chauhan J., Nevels K., Yap J.L., Zhang J. Structural modifications of (Z)-3-(2-aminoethyl)-5-(4-ethoxybenzylidene)thiazolidine-2,4-dione that improve selectivity for inhibiting the proliferation of melanoma cells containing active ERK signaling. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:3706–3732. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40199e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Momose Y., Meguro K., Ikeda H., Hatanaka C., Oi S., Sohda T. Studies on antidiabetic agents. X. Synthesis and biological activities of pioglitazone and related compounds. Chem Pharm Bull. 1991;39:1440–1445. doi: 10.1248/cpb.39.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruno G., Costantino L., Curinga C., Maccari R., Monforte F., Nicoló F. Synthesis and aldose reductase inhibitory activity of 5-arylidene-2,4-thiazolidinediones. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:1077–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ottanà R., Maccari R., Barreca M.L., Bruno G., Rotondo A., Rossi A. 5-Arylidene-2-imino-4-thiazolidinones: design and synthesis of novel anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:4243–4252. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ottanà R., Maccari R., Mortier J., Caselli A., Amuso S., Camici G. Synthesis, biological activity and structure-activity relationships of new benzoic acid-based protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors endowed with insulinomimetic effects in mouse C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;71:112–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z., Lu X., Feng L.J., Gu Y., Li X., Wu Y. Molecular dynamics-based discovery of novel phosphodiesterase-9A inhibitors with non-pyrazolopyrimidinone scaffolds. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:115–125. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00389f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou T., Wang J., Li Y., Wang W. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 1. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:69–82. doi: 10.1021/ci100275a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu L., Sun H., Li Y., Wang J., Hou T. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods. 3. The impact of force fields and ligand charge models. J Phys Chem B. 2013;117:8408–8421. doi: 10.1021/jp404160y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang J., Wu P., Yang R., Gao L., Li C., Wang D. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by two genistein derivatives: kinetic analysis, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2014;4:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H., Yan Z., Yang S., Cai J., Robinson H., Ke H. Kinetic and structural studies of phosphodiesterase-8A and implication on the inhibitor selectivity. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12760–12768. doi: 10.1021/bi801487x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juilfs D.M., Fülle H.J., Zhao A.Z., Houslay M.D., Garbers D.L., Beavo J.A. A subset of olfactory neurons that selectively express cGMP-stimulated phosphodiesterase (PDE2) and guanylyl cyclase-D define a unique olfactory signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3388–3395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huai Q., Wang H., Sun Y., Kim H.Y., Liu Y., Ke H. Three-dimensional structures of PDE4D in complex with roliprams and implication on inhibitor selectivity. Structure. 2003;11:865–873. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H., Liu Y., Chen Y., Robinson H., Ke H. Multiple elements jointly determine inhibitor selectivity of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases 4 and 7. J Biol Chem. 2007;280:30949–30955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reed T.M., Browning J.E., Blough R.I., Vorhees C.V., Repaske D.R. Genomic structure and chromosome location of the murine PDE1B phosphodiesterase gene. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:571–576. doi: 10.1007/s003359900820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denizot F., Lang R. Rapid colorimetric assay for cell growth and survival: modifications to the tetrazolium dye procedure giving improved sensitivity and reliability. J Immunol Methods. 1986;89:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M.L., Darden T., Lee H., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyamoto S., Kollman P.A. Settle: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J Comput Chem. 1992;13:952–962. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Massova I., Kollman P.A. Combined molecular mechanical and continuum solvent approach (MM-PBSA/GBSA) to predict ligand binding. Perspect Drug Discov Des. 2000;18:113–135. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Case D.A., Mermelstein D., Walker R.C., Li P., Cheatham T.E., III, Onufriev A. University of California; San Francisco: 2014. AMBER 16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material