Abstract

Microemulsions are promising drug delivery systems for the oral administration of poorly water-soluble drugs. However, the evolution of microemulsions in the gastrointestinal tract is still poorly characterized, especially the structural change of microemulsions under the effect of lipase and mucus. To better understand the fate of microemulsions in the gastrointestinal tract, we applied small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to monitor the structural change of microemulsions under the effect of lipolysis and mucus. First, the effect of lipolysis on microemulsions was studied by SAXS, which found the generation of liquid crystalline phases. Meanwhile, FRET spectra indicated micelles with smaller particle sizes were generated during lipolysis, which could be affected by CaCl2, bile salts and lecithin. Then, the effect of mucus on the structural change of lipolysed microemulsions was studied. The results of SAXS and FRET indicated that the liquid crystalline phases disappeared, and more micelles were generated. In summary, we studied the structural change of microemulsions in simulated gastrointestinal conditions by SAXS and FRET, and successfully monitored the appearance and disappearance of the liquid crystalline phases and micelles.

KEY WORDS: Microemulsions, SAXS, FRET, Lipolysis, Mucus, Liquid crystalline phase

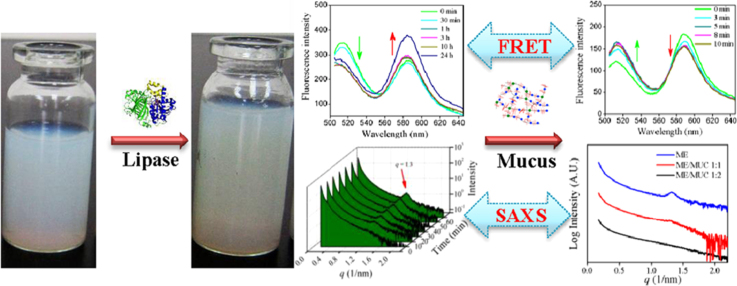

Graphical abstract

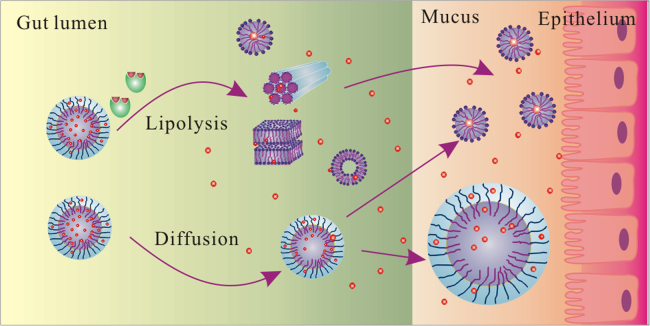

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) methods were applied to monitor the structural change of microemulsions under the effect of lipolysis and mucus in this work. We found that liquid crystalline phases and micelles were appeared under lipolysis, and liquid crystalline phases were disappeared in mucus.

1. Introduction

In the past several decades, many new formulations have been developed to improve the oral bioavailability of drugs1. Among those formulations, microemulsions and self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems (SMEDDS) have been proven to be promising drug delivery systems for the oral administration of poorly water-soluble drugs2, 3. Microemulsions are single optically isotropic and thermodynamically stable liquid solutions composed of water, oil, surfactants and co-surfactants. SMEDDS is a preconcentrate of microemulsions that forms stable microemulsions in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract under gentle digestive motility4. Microemulsions and SMEDDS can significantly promote the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs by improving the solubility and the dissolution rate, increasing the intestinal epithelial permeability, inhibiting the P-glycoprotein drug efflux and promoting lymphatic transport5, 6. Several products have been successfully commercialized in the last two decades, including Neoral® (cyclosporine A), Norvir® (ritonavir), Fortovase® (saquinavir), and Agenerase® (amprenavir)7.

Despite the benefits, the development of microemulsion formulations still encounters some problems, e.g., the toxicity of surfactant and drug precipitation8. The primary problem is the poor correlation between the microemulsion characteristics in vitro and the drug bioavailability in vivo9, 10. Microemulsion characteristics such as particle size, chain length of triglyceride as well as surfactant/oil ratio are considered the main factors of influencing the bioavailability of drugs. However, the effect of those characteristics was always controversial as reported by previous research11, 12, 13. Hence predicting the drug bioavailability of microemulsions in vivo is extremely difficult. The main reason is microemulsions undergo various structural changes in the GI tract, which is quite difficult to monitor; therefore, leading the fate of microemulsions in the GI tract is still poorly characterized14. Before being absorbed by the intestine epithelium, microemulsions encounter the lipolysis of lipase and the hindrance of the mucus barrier, where complicated structural changes occur.

Lipase is considered one of the main barriers affecting the fate of microemulsions in the GI tract. As the oil phases are digested by lipases (especially the pancreatic lipase), microemulsions suffer complicated structural changes in the GI tract15. The study of microemulsion digestion is commonly carried out by the in vitro lipolysis model16. Fatouros et al. reported the formation of the unilamellar spherical vesicle, the bilamellar vesicle and micelles during SMEDDS digestion observed by the cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM)17. Interestingly, Tran et al.18 also found multivesicular and unilamellar vesicles in the human intestinal contents with cryo-TEM. Moreover, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) have been applied to monitor the structure of digested microemulsions, founding the formation of micelles, lamellar liquid crystalline and hexagonal liquid crystalline phases19, 20, 21, 22. The physicochemical properties (including the particle sizes, particle geometry, zeta potentials, and solubilizing capabilities) of the generated intermediate phases (micelles, vesicles as well as liquid crystals) are obviously different from that of microemulsions. Theoretically, the performance of the intermediate phases in the GI tract should be varied from microemulsions; therefore, the loaded drugs might suffer different fates in the GI tract. It has been reported that the generation of the intermediate phases is highly associated with the lipolysis of the microemulsions. The type and amount of each intermediate phase is highly associated with the types of surfactant and oil, the surfactant/oil ratio, as well as the physicochemical properties of microemulsions during digestion23. In our previous work, we found the dissolution rate of drug from microemulsions was affected by lipolysis, which was related to the extent of the digested oil phase24.

The mucus layer, a selective viscoelastic hydrogel on the surface of epithelial cells, is considered another barrier affecting the fate of drugs in the GI tract25. The mucus layer retards the diffusion of drugs and carriers, not only by the size exclusion effect of the hydrogel but also by the interactions between mucin and drugs (or carriers). Mucoadhesive nanoparticles and mucus-penetrating nanoparticles have been designed to overcome the mucus barrier26. Microemulsions coated with a dense PEG shell significantly avoid the hindrance of mucus, and several mucus-penetrating microemulsions have been reported27, 28, 29. Moreover, some reports demonstrated that partially intact lipid-based nanoparticles diffuse through the mucus layer, including the intestinal epithelium30, 31. However, it worth noting that the intermediate phases will be inevitably affected by the mucus layer when passing through mucus, and the performance should be dependent on their physicochemical properties. Up to now, some research has reported the diffusion of microemulsions through the mucus layer; however, the fate of digested microemulsions in mucus has never been reported.

Hence, to accurately predict the drug bioavailability of microemulsions in vivo, it is necessary to demonstrate the structural change pathway of microemulsions in the GI tract, especially the effect of lipase and mucus. In this work, we monitored the structural change of microemulsions on lipolysis as well as the further structural change of digested microemulsions in the mucus layer by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

MCT (medium chain triglyceride) was provided by Qiandao Fine Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). Cremophor RH40 was purchased from Puruixing Fine Chemicals Co., Ltd. (Shenyang, China). Ethyl oleate (EO) and tributyrin were obtained from Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 1,2-Propanediol and castor oil were purchased from Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China). Taurocholic acid sodium salt (NaTC) was purchased from Bio Basic Inc. (Markham, Ontario, Canada). Lecithin (PC) was purchased from Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Porcine pancreatin (8×USP specifications activity) and mucin from porcine stomach (type II) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). 4-Bromophenylboronic acid (4-BPB) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Tianjin, China). HPLC grade Methanol was supplied by J&K Chemical Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

2.2. Preparation of SMEDDS and the characterization of microemulsions

SMEDDS formulations were prepared following the method in our previous report24. Briefly, MCT, ethyl oleate and castor oil were selected as the oil phase, while Cremophor RH40 and 1,2-propanediol were selected as the surfactant and co-surfactant. Each component was accurately weighed according to the ratios shown in Table 1. They were added into sealed glass vials and stirred on a magnetic stirrer overnight to obtain the SMEDDS formulations. Microemulsions were obtained by adding moderate amount of deionized water to 1 g SMEDDS formulation and stirred 1 h on a magnetic stirrer.

Table 1.

Compositions of four SMEDDS formulations.

| Compositions (w/w) | SMEDDS formulations |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SME-1 | SME-2 | SME-3 | SME-4 | |

| MCT | 60% | 40% | ||

| Ethyl oleate | 40% | |||

| Castor oil | 40% | |||

| Cremophor RH40 | 27% | 40% | 40% | 40% |

| 1,2-Propanediol | 13% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

The particle size, polydispersity index and zeta potential of SME 1–4 microemulsions with 100-fold dilution were measured by Malvern ZS90 zetasizer (Malvern Instruments Corp, Malvern, UK). Briefly, microemulsions were diluted 100 times by deionized water, and 1 mL of microemulsions were put into the cell to measure the particle size, polydispersity index and zeta potential. For each group, three parallel samples were measured.

2.3. Influence of lipolysis on the structure of microemulsions

2.3.1. In vitro lipolysis study

One gram of SMEDDS formulation was separately mixed with 18 mL Sorensen׳s phosphate buffer solution (0.067 mmol/L, pH 7.0) to form microemulsions in a sealed glass vial, and kept at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, 1 mL pancreatin extract was added to begin the lipolysis experiment. After 6 h, 100 μL 4-BPB solution (a lipolysis inhibitor, 0.5 mol/L) was added into the mixture to stop further lipolysis. Finally, 1 mL the mixture was taken for particle size distribution analysis, while the remaining mixture was placed for 2 h for further observation.

Pancreatin extract was prepared by adding 1 g porcine pancreatin (containing pancreatic lipase and co-lipase) to 5 mL digestion buffer (50 mmol/L Trizma maleate, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L CaCl2·2H2O, pH 7.5) containing 5 mmol/L NaTC and 1.25 mmol/L PC. The mixture was stirred for 15 min followed by centrifugation at 1600×g and 5 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and stored on ice. Pancreatin extracts were freshly prepared for each experiment. The lipase activity of pancreatin extract was measured according to the previously reported method32, 33. Briefly, 6 mL tributyrin was added into 10 mL digestion buffer at pH 7.5 and 37 °C. Then, 1 mL pancreatin extract was added to start the measurement. The pH-Stat automatic titration unit (848 Titrino plus, Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland) was used to maintain the pH at 7.50 ± 0.05 by titrating with 0.1 mol/L NaOH to neutralize the generated fatty acids. The lipase activity of pancreatin extract was expressed in terms of tributyrin units (TBU), where 1 TBU is the amount of enzyme that can liberate 1 μmol of titratable fatty acids from tributyrin per min. In this work, the lipase activity of 1 mL pancreatin extract was measured to be 2803 TBU.

2.3.2. SAXS monitoring the structural change of microemulsions during lipolysis

First, 1 g SMEDDS formulation was weighed and dissolved in 18 mL simulated fasted intestinal fluid (50 mmol/L Trizma maleate, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L CaCl2·2H2O, 5 mmol/L NaTC, 1.25 mmol/L PC, pH 7.5). The pH was then adjusted to 7.5 with 0.1 mol/L NaOH. Then, 1 mL pancreatin extract was added to the mixture to initiate the lipolysis experiment at 37 °C. Meanwhile, a pH-Stat automatic titration unit (848 Titrino plus, Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland) was used to maintain the pH at 7.50 ± 0.05 by titrating with 0.1 mol/L NaOH. At the lipolysis time of 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 min, 0.5 mL sample was withdrawn and added into the sample cell through a syringe for SAXS analysis. The front and back of the sample cell was covered by two pieces of polyamide membrane.

SAXS measurements were performed in a beamline (BL16B1) of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) with an X-ray energy of 10 keV (corresponding to a wavelength (λ) of 1.24 Å). The sample-to-detector distance was 1.87 m, and the exposure time was set to 300 s. After the data acquisition, the obtained 2D images were integrated into 1D scattering curves (I(q) vs q) by means of the Fit2D software, according to Eq. (1).

| (1) |

where q is the scattering vector, λ = 1.24 Å is the X-ray wavelength and 2θ is the scatting angle.

2.3.3. FRET monitoring the structural change of microemulsions during lipolysis

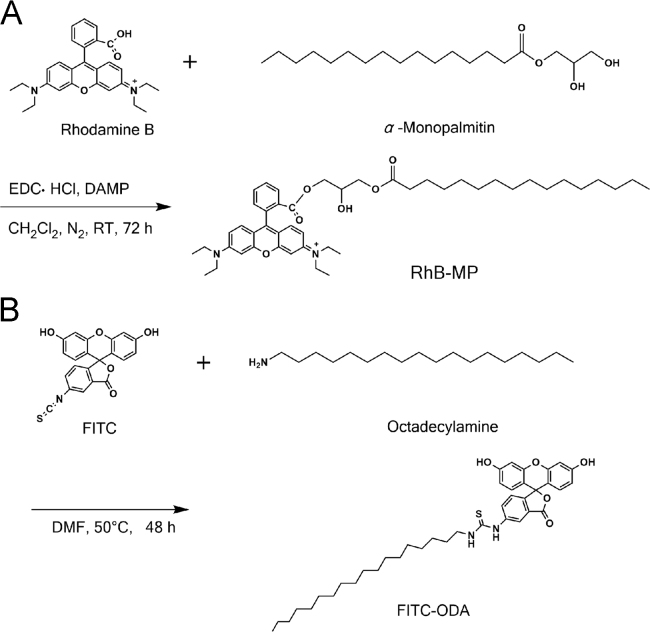

The fluorescent probes RhB-MP and FITC-ODA were synthesized as a FRET pair according to our previously reported method34. RhB-MP was synthesized by forming an ester between the carboxyl group of rhodamine B (RhB) and the hydroxyl group of α-monopalmitin (MP). The FITC-ODA was synthesized by the reaction between the isothiocyanate group of FITC and the amino group of octadecylamine (ODA) (see Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of fluorescent probes RhB-MP (A) and FITC-ODA (B).

The FRET experiment was carried out using a Perkin-Elmer LS 55 luminescence spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer Ltd, Beaconsfield, England). Briefly, SMEDDS containing RhB-MP (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 15 mg/g) and FITC-ODA (5 mg/g) were prepared in the dark and diluted 20 times with deionized water. One millilitre of the formed microemulsions was put into a quartz cell and measured by the luminescence spectrometer. The excitation wavelength was set to 491 nm and the emission wavelength ranged from 500 to 650 nm. The slit widths of the excitation and emission were both 10 nm and the emission filter was set to 1% T attenuator. Similarly, RhB-MP and FITC-ODA in aqueous solution with different concentration ratios were prepared by maintaining the concentration of FITC-ODA constant and altering the amount of RhB-MP. The fluorescence spectra were recorded by the PerkinElmer LS55 luminescence spectrometer with the same conditions.

To monitor the structural change of microemulsions during lipolysis, 1 g SME-3 SMEDDS formulation containing 5 mg RhB-MP and 5 mg FITC-ODA was dissolved into 18 mL Sorensen׳s phosphate buffer solution (containing 5 mmol/L CaCl2 or 5 mmol/L NaTDC/1.25 mmol/L PC). Then, 1 mL pancreatin extract was added to the mixture to initiate the lipolysis experiment. At different lipolysis times, the emission spectra of the lipolysed microemulsions were recorded ranging from 500 to 650 nm. Moreover, the ratios of fluorescence intensity at 580 nm/520 nm were calculated and compared, at different lipolysis times.

2.4. Influence of mucus on the structure of microemulsions

2.4.1. Preparation of mucin solution

Mucin solution with the concentration of 5% (w/v) was prepared as simulated mucus. Briefly, porcine gastric mucin was added into a sealed glass vial containing the desired amount of Sorensen׳s phosphate buffer solution. Then, the mixtures were gently stirred for 2 h on ice to obtain the mucin solution. For all experiments, the mucin solution was freshly prepared and equilibrated to room temperature before use.

2.4.2. Diffusion in of microemulsions in mucus

The diffusion of microemulsions in mucus was measured by multiple particle tracking (MPT), according to previously reported method35, 36. Briefly, FITC-ODA labeled SME 1–4 were added to simulated mucus (0.2%, w/w) or water, with the concentration of 20 μg/mL. The samples were equilibrated for 30 min at 37 °C, and then transferred to microwells. The Brownian movement was observed by an inverted epifluorescence microscope equipped with a 100× oil-immersion objective and a CCD camera. Movies was captured for 20 s and analyzed with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software to extract the x and y positions of microemulsions centroids over time. For each trajectory, the time-averaged mean squared displacement (MSD) was calculated as a function of time scale. The ensemble-averaged MSD (<MSD>) for all microemulsions in mucus was calculated by taking the geometric mean of the individual microemulsions׳ time-averaged MSD.

2.4.3. SAXS monitoring the structural change of lipolysed microemulsions in mucus

After the lipolysis study mentioned in Section 2.3.1, the lipolysed microemulsions were obtained by adding 100 μL 4-BPB solution to stop the lipolysis reaction, at the lipolysis time of 60 min. The lipolysed microemulsions were then mixed with simulated mucus at the volume ratios of 1:1, 1:2 and 2:1. After stirring for 30 min, the mixtures (0.5 mL) were added into the sample cell through a syringe for SAXS analysis.

2.4.4. FRET monitoring the structural change of lipolysed microemulsions in mucus

SME-3 SMEDDS formulation containing RhB-MP (5 mg/g) and FITC-ODA (5 mg/g) was prepared and lipolysed following the method mentioned in Section 2.3.1. After 6 h, the lipolysed microemulsions were obtained by adding 100 μL 4-BPB solution. The lipolysed microemulsions were mixed with simulated mucus at the volume ratio of 1:1, and gently stirred on a magnetic stirrer in dark. At predetermined time intervals, the emission spectrum of the mixture was recorded.

Furthermore, Cremophor RH40, 1,2-propanediol, ethyl oleate and oleic acid were mixed with the ratio of 40:20:24:16 (w/w), to simulate the lipolysed SME-3 microemulsions (40% oil phase lipolysed). In the FRET study, the simulated lipolysed microemulsions containing RhB-MP (5 mg/g) and FITC-ODA (5 mg/g) was also mixed with simulated mucus and the emission spectra at predetermined time intervals were recorded.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Influence of lipolysis on the structure of microemulsions

3.1.1. Characteristics of microemulsions before and after lipolysis

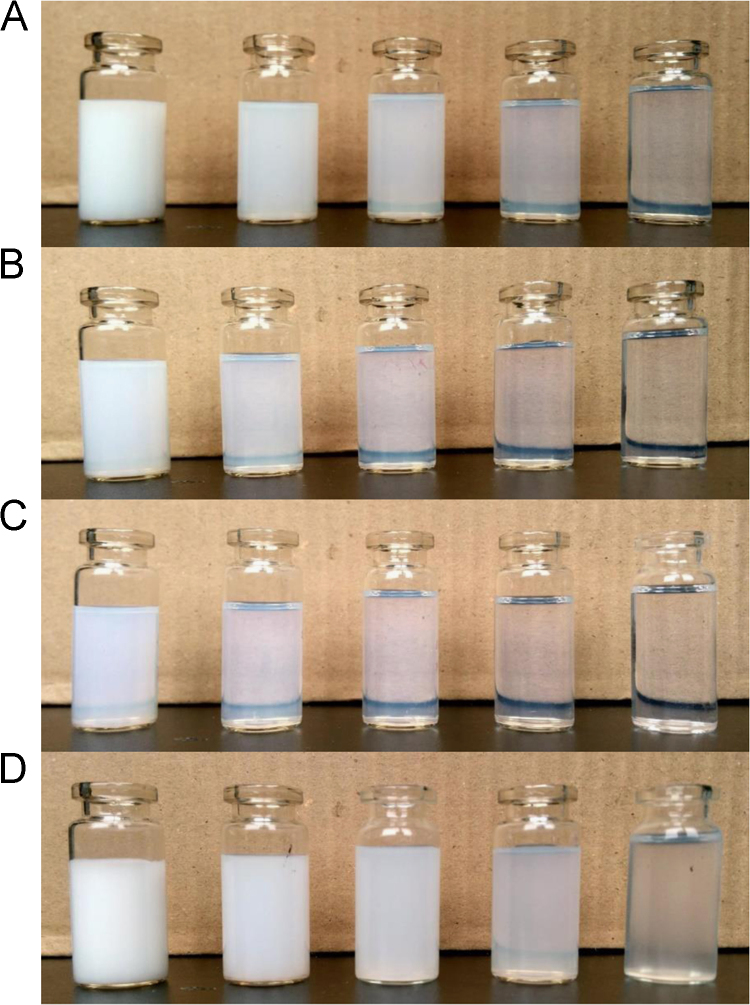

As listed in Table 1, four SMEDDS formulations (SME 1-4) have been previously prepared, with Cremophor RH40/1,2-propanediol (2:1, w/w) serving as the surfactant/co-surfactant and different lipids (MCT, ethyl oleate and castor oil) serving as the oil phase 24. Fig. 1 shows the visual appearance of SME 1-4 microemulsions diluted 20-fold, 100-fold, 200-fold, 500-fold and 1000-fold with deionized water. Table 2 listed the particle size, polydispersity index and zeta potential of microemulsions with 100-fold dilution. We found the appearance of microemulsions was closely related to the dilution times. They could form homogenous microemulsions with light blue opalescence, after being diluted more than 100 times. SME-2 and SME-3 had similar particle sizes of 66.7±1.2 nm and 63.5±0.5 nm, and they seemed more clear and transparent. SME-1 and SME-4 appeared to be opaque milky emulsion at low dilution rates; however, their particle sizes (153.5±4.6 nm and 205.8±10.8) were still in the range of microemulsions at 100-fold dilution.

Figure 1.

Visual appearance of SME-1 (A), SME-2 (B), SME-3 (C) and SME-4 (D) with different dilution times. From left to right, the microemulsions were diluted 20-fold, 100-fold, 200-fold, 500-fold and 1000-fold.

Table 2.

Mean particle size, polydispersity index and zeta potential of diluted microemulsions (Mean ± SD, n = 3).

| Mean particle size (nm) | Polydispersity index | Zeta potential (mV) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SME-1 | 153.5 ± 4.6 | 0.513 ± 0.011 | −9.70 ± 0.83 |

| SME-2 | 66.7 ± 1.2 | 0.213 ± 0.005 | −7.18 ± 0.71 |

| SME-3 | 63.5 ± 0.5 | 0.183 ± 0.008 | −8.22 ± 1.54 |

| SME-4 | 205.8 ± 10.8 | 0.536 ± 0.049 | −9.24 ± 0.61 |

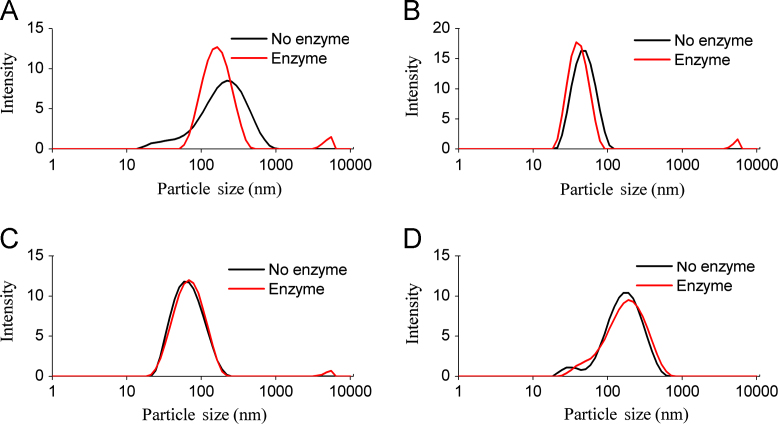

It is worth noting that, the increased or decreased particle sizes of digested microemulsions were partly dependent on their compositions. Joseph Chamieh et al.37 applied a Taylor dispersion analysis to study the particle sizes of SEDDS during lipolysis. They found the particle sizes of a Labrasol®-based formulation exponentially decreased, and that of a Gelucire® 44/14-based formulation sigmoïdally increased. In this work, the four microemulsions were lipolysed for 6 h under the present of pancreatin extract. The visual appearance and particle size distribution of microemulsions before and after lipolysis were recorded (Figs. 2 and 3). As seen in Fig. 2, lipase had completely destroyed the structure of SME-1 microemulsions, leading to the disappearance of the milk white colour. SME-1 microemulsions were composed of MCT/Cremophor RH40/1,2-propanediol (60:27:13, w/w), and MCT was digested into caprylic/capric acids, diglycerides and 2-monoglycerides. In our previous study, we found up to 100% of MCT was digested for SME-1 in 1 h lipolysis24. The generated products were excessive and formed unstable structures, which finally separated from the aqueous phase. As seen in Fig. 3A, the particle sizes of SME-1 microemulsions were also obviously altered under the effect of lipolysis. The micron-sized structures were appeared in the lipolysed SME-1 microemulsions, which should be the unstable structures formed by the lipolysis products. Apart from the micron-sized structures, the particle sizes of digested SME-1 microemulsions were even smaller than undigested microemulsions. This could be attributed to the loss of MCT leading microemulsions shrinking. Compared to SME-1 microemulsions, SME 2–4 microemulsions contained higher amounts of surfactant and co-surfactant (60%, w/w), which stayed at the interface and could inhibit lipase hydrolysing the oil phase. Moreover, ethyl oleate and castor oil were more stable than MCT under digestion, which led the degree of lipid digested to be much lower than for the SME-1 microemulsions12. In our previous work, the degrees of digested oil phases were found to be less than 40% for SME-2 microemulsions and less than 8.5% for SME 3–4 microemulsions24. As shown in Fig. 2 and 3B–D, the lipolysed SME 2–4 microemulsions were still homogeneous in appearance, and the change of particle size distributions was negligible.

Figure 2.

The visual appearance of microemulsions before (left) and after (right) lipolysis.

Figure 3.

The particle size distribution of microemulsions before and after lipolysis. (A) SME-1, (B) SME-2, (C) SME-3, (D) SME-4.

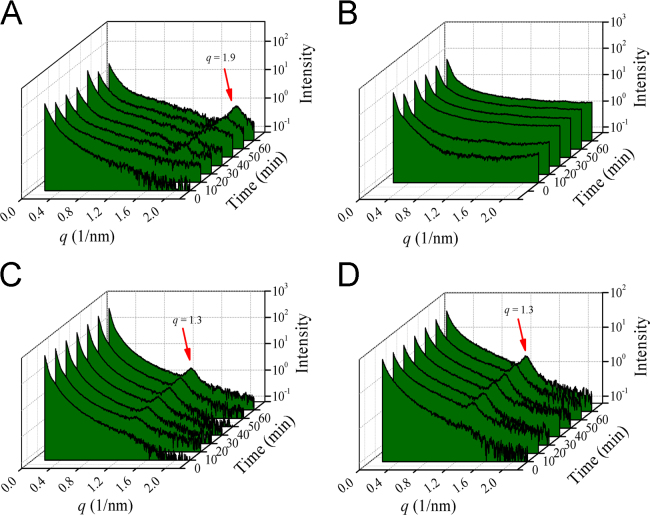

3.1.2. SAXS monitoring the structural change of microemulsions during lipolysis

In SAXS experiments, the elastic scattering of X-rays by samples (with different electron density) was recorded at very low angles (typically 0.1–10°). This angular range contains information about the shape and size of macromolecules, characteristic distances of partially ordered materials, pore sizes, and other data. Hence, SAXS is commonly used to determine the priorities of biological materials, polymers, colloids, chemicals, nanocomposites, metals, minerals, food and pharmaceuticals38, 39. Researchers have studied the intermediate phases of digested microemulsions using SAXS, and they identified the structure of unilamellar vesicles, bilamellar vesicles, micelles, lamellar and hexagonal liquid crystals17, 20. Moreover, they found the formation of the intermediate phases was highly related to the digestion time and the compositions20. To identify the structure of the intermediate phases during the digestion of the four formulations, we applied SAXS to monitor the microemulsions with different digestion times. As seen in Fig. 4, the SAXS data recoded the curve of intensity versus the wave vector (q). No Bragg peak was found in the SAXS spectra of four microemulsions before digestion. However, the Bragg peaks appeared in SME-1 (q = 1.9 nm−1), SME-3 (q = 1.3 nm−1) and SME-4 (q = 1.3 nm−1) microemulsions after the lipolysis started, and the intensity of the Bragg peak gradually increased with lipolysis time. The appearance of the Bragg peaks means some liquid crystalline phases formed40, 41. The higher Bragg peak intensity indicated more liquid crystalline intermediate phases were generated.

Figure 4.

SAXS spectra recorded for the four microemulsion formulations during digestion at 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 60 min. The intensity is plotted versus the wave vector. (A) SME-1, (B) SME-2, (C) SME-3, (D) SME-4.

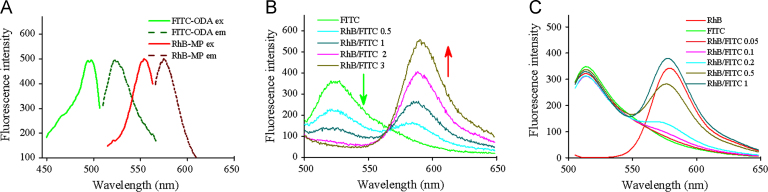

3.1.3. FRET monitoring the structural change of microemulsions during lipolysis

FRET was also applied to monitor the structural change of microemulsions during digestion in this study. FRET is commonly used to determine molecular interaction in a myriad of biological processes, as well as the stability of nanoparticles42, 43. FRET is distance-dependent and occurs only when the distance between the donor and acceptor less than 10 nm44. Pan et al.45 previously applied FRET to analyse the dynamics of emulsion interfaces during digestion, and they found changes in the donor/acceptor ratio in FRET reflect the release of fatty acids. In this study, we applied the synthesized fluorescent probes FITC-ODA and RhB-MP as the FRET donor/acceptor pair (see Scheme 1). Both FITC-ODA and RhB-MP were hydrophobic due to the introduction of octadecylamine and α-monopalmitin, which ensured they were embedded in the core of microemulsions. There was an overlap between the emission spectrum of FITC-ODA and the excitation spectrum of RhB-MP (see Fig. 5A), indicating the possibility of energy transfer from FITC-ODA to RhB-MP. Then, RhB-MP and FITC-ODA were co-loaded in microemulsions, where the concentration of FITC-ODA was held constant and the amount of RhB-MP was altered. As seen in Fig. 5B, the fluorescence intensity of FITC-ODA gradually decreased with the increase of RhB-MP, despite the unchanged concentration of FITC-ODA. This demonstrated that the energy transfer occurred from FITC-ODA to RhB-MP, after they were co-loaded in microemulsions. Furthermore, we measured the fluorescence spectra of RhB-MP/FITC-ODA in aqueous solution, under the same condition. The results showed that the increase of RhB-MP slightly decreased the intensity of FITC-ODA (see Fig. 5C). The decrease of FITC-ODA intensity in aqueous solution was negligible compared to that of microemulsions, at the RhB-MP/FITC-ODA ratio of 1:1. Hence, the FRET was negligible in aqueous solution, where FITC-ODA and RhB-MP were homogeneously distributed, and the distance was generally more than 10 nm. However, when FITC-ODA and RhB-MP were co-loaded in microemulsions with particle sizes smaller than 200 nm, plenty of FRET pair had a distance less than 10 nm, meaning that FRET obviously occurred inside of the microemulsions.

Figure 5.

(A) The excitation spectra (ex) and emission spectra (em) of FITC-ODA and RhB-MP. (B) The fluorescence emission spectra of FRET probes loaded microemulsions with different RhB-MP/FITC-ODA ratios. (C) The fluorescence emission spectra of FRET probes in aqueous solution with different RhB-MP/FITC-ODA ratios.

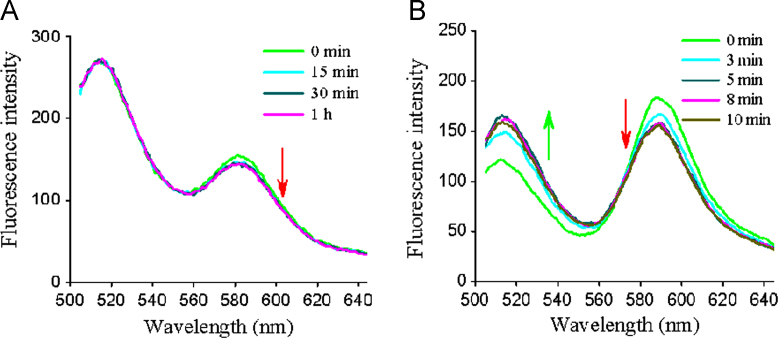

Based on the FRET microemulsions, we studied the fluorescence emission spectra of microemulsions during lipolysis. In this work, we fixed the RhB-MP/FITC-ODA ratio at 1:1 (w/w), and the structural change of microemulsions could be reflected by the change of the fluorescence spectra. Generally, the FRET efficiency (or the acceptor/donor ratio) is dependent on the distance of the FRET pair, where the closer distance results in higher FRET efficiency. Hence, we considered that the formation of intermediate phases with larger particle sizes separates the FRET pair farther and the FRET efficiency decreases. Similarly, the formation of smaller intermediate phases will lead to the FRET efficiency increasing. SME-3 microemulsions were selected as the model, which generated oleic acid and ethanol after lipolysis. As seen in Fig. 6, the fluorescence spectra of FRET microemulsions were changed at different digestion times, with the intensity of FITC-ODA at 520 nm gradually decreased. Similarly, the decrease of fluorescence intensity at 520 nm was observed in microemulsions containing CaCl2 or NaTDC/PC. The fluorescence intensity of RhB-MP at 580 nm was also altered at different digestion times. To further compare difference of the fluorescence spectra, we calculated the intensity ratios of RhB-MP at 580 nm (I580) and FITC-ODA at 520 nm (I520) and normalized the I580/I520 ratio to the microemulsions before digestion. The normalized I580/I520 ratio reflects the extent of energy transferred from FITC-ODA to RhB-MP. From Fig. 6D, we found the ratio of I580/I520 gradually increased with the digestion time, and the presence of CaCl2 and NaTDC/PC accelerates the increase of I580/I520 ratio. The results indicated that more energy was transferred from FITC-ODA to RhB-MP during the lipolysis of microemulsions, meaning that intermediate phases with smaller particle sizes were generated. We inferred that the smaller intermediate phases should be the mixed micelles. Because various studies have demonstrated that the mixed micelles, with small particle sizes of approximately 10 nm, were one of the main intermediate phases of digested lipid based formulations17. In the GI tract they were formed in the present of fatty acids, monoglycerides, bile salts and lecithin. It was reported that the generated fatty acids could inhibit the binding of lipase to the oil phase by staying at the interface of microemulsions. However, CaCl2 and NaTDC/PC could remove fatty acids from the interface by forming calcium soaps and mixed micelles15, 46. Hence, the addition of CaCl2 or NaTDC/PC accelerates the formation of micelles. Interestingly, the liquid crystalline phases observed by SAXS have much larger particle sizes and should decrease the I580/I520 values decreased. This seemed contradictory to the FRET results. In fact, the liquid crystalline phases and micelles are always coexisted in the digested lipid based drug delivery systems, as reported by many researchers 17, 20, 21, 38. In this experiment, the number of micelles should be far greater than the liquid crystalline phases, increasing the I580/I520 values increased. In the work of Pan at al.45, the acceptor/donor ratio was also increased during lipid-based formulation digestion in the present of bile salts.

Figure 6.

The fluorescence emission spectra of FRET microemulsions during lipolysis, (A) microemulsions in PBS, (B) microemulsions in PBS with 5 mmol/L CaCl2, (C) microemulsions in PBS with 5 mmol/L NaTDC/1.25 mmol/L PC. (D) The normalized intensity ratios of I580/I520 of microemulsions during digestion.

3.2. Influence of mucus on the structure of microemulsions

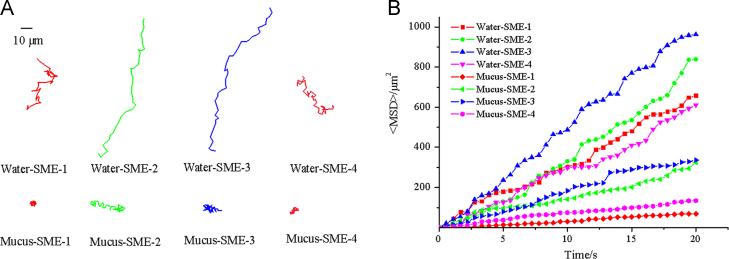

3.2.1. Diffusion in of microemulsions in mucus

We compared the diffusion in of microemulsions in mucus and water by multiple particle tracking (MPT). As seen in Fig. 7A, the representative trajectories of microemulsions in water and mucus showed that the movement distance of microemulsions in mucus was much lower than that in water. Furthermore, the ensemble-averaged MSD (<MSD>) for microemulsions in mucus and water was calculated and shown in Fig. 7B. The result showed that <MSD> of microemulsions in water was much higher than that in mucus. It was obvious that the diffusion of microemulsions was severely hindered by mucus, which might be caused by the interactions between mucin and microemulsions, as well as the mesh of mucus. Hence, it is essential to study the fate of microemulsions in mucus and find the solution to overcome the mucus barrier. It worth noting that, SME-2 and SME-3 with smaller particle sizes exhibited much higher <MSD> than SME-1 and SME-4 (see Fig. 7B), meaning the particle sizes played an important role on the diffusion of microemulsions in mucus.

Figure 7.

Transport of SME 1–4 in water and mucus. (A) Representative trajectories of SME 1–4 in water and mucus during 20 s movies. (B) Ensemble-averaged geometric mean square displacement (<MSD>) of SME 1–4 in water and mucus.

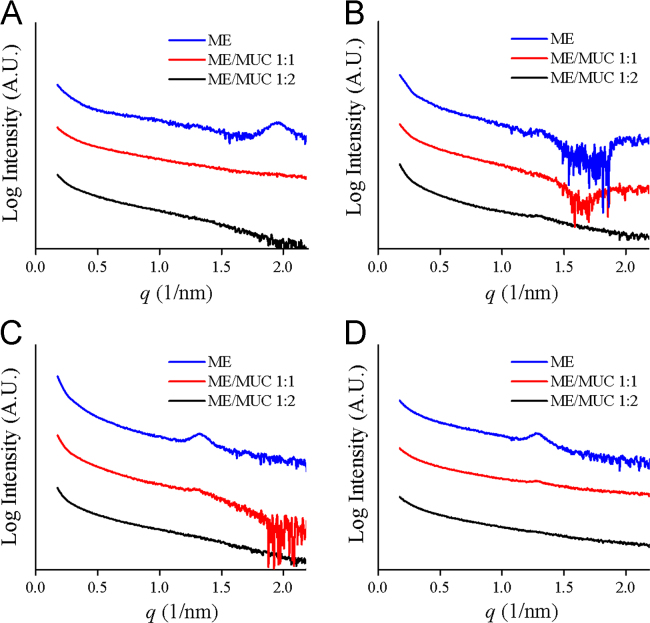

3.2.2. SAXS monitoring the structural change of lipolysed microemulsions in mucus

After being digested by lipase, microemulsions as well as the intermediate phases must diffuse through the mucus layer before reaching the epithelial cells. In mucus, mucin or lipids might interact with the microemulsions and the intermediate phases, resulting in further structural change. In our previous report, we found part of the microemulsions aggregated into larger emulsions in mucus34. Here we applied SAXS and FRET to monitor the further structural change of lipolysed microemulsions in mucus. The lipolysed microemulsions were mixed with mucus for 30 min. As seen in Fig. 8, the Bragg peaks disappeared in the SAXS spectra of SME-1, SME-3 and SME-4, at the microemulsions/mucus ratios of 1:1 and 1:2. This indicated the liquid crystalline phases were damaged in mucus. In the structure of mucin proteins, there are many naked hydrophobic cysteine-rich domains, which could absorb significant lipids by forming numerous low-affinity bonds47. The damage to the liquid crystalline phases might be attributed to the hydrophobic interaction and the hydrogen bonds, between mucin and liquid crystals.

Figure 8.

SAXS spectra recorded for the lipolysed microemulsions in mucus. The intensity is plotted versus the wave vector. (A) SME-1, (B) SME-2, (C) SME-3, (D) SME-4.

3.2.3. FRET monitoring the structural change of lipolysed microemulsions in mucus

In the FRET study, we used FRET probes to label the lipolyzed SME-3 microemulsions and mixed the microemulsions with mucus for different times. From Fig. 9A, we found the fluorescence intensity of RhB-MP at 580 nm was slightly decreased after mixed for more than 15 min, despite the change was not obvious. As previously reported, the percentage of lipolysed SME-3 microemulsions was less than 8.5%, we thought that higher degree of lipolysis might make the change to the SAXS data more obvious. Therefore, we prepared the formulation containing oleic acid (16%, w/w) to simulate the lipolysed microemulsions with 40% of oil phase digested. After the simulated lipolysed SME-3 microemulsions were mixed with mucus, the fluorescence spectra were significantly changed; the fluorescence intensity decreased at 520 nm and increased at 580 nm (Fig. 9B). These results demonstrated that more energy was transferred from the donor to the acceptor, meaning the particle sizes of the lipolysed microemulsions decreased and the distance between the probes shortened. Here, we inferred that the liquid crystalline phases transformed into smaller micelles in mucus, as they could interact with mucin or lipids. In fact, the lyotropic liquid crystals generated from lipolysed microemulsions were unstable and transformed into other structures depending on the concentrations and components. Lyotropic liquid crystals applied for drug carriers have been widely studied. Especially, cubic and hexagonal mesophases are good candidates for mucosal drug delivery systems due to their mucoadhesive properties. The interaction of liquid crystalline phases with mucin would inevitably inhibit their diffusion through the mucus layer. However, they transformed into smaller micelles in mucus. We thought that this might be beneficial for lipolysed microemulsions to rapidly diffuse through the mucus layer.

Figure 9.

The fluorescence emission spectra of lipolysed SME-3 microemulsions (A) and the simulated lipolysed SME-3 microemulsions (B).

Based on the results above, we found the microemulsions suffered complicated structural changes under the effect of lipase and mucus (see Fig. 9). Microemulsions were first digested by lipase to form several intermediate phases. SAXS identified the formation of liquid crystalline phases during digestion. FRET found that the intermediate phases with smaller particle sizes were formed, which was mainly micelles. In mucus, the structure of the intermediate phases was further altered, with the Bragg peaks of liquid crystalline phases disappearing in the SAXS spectra. FRET results indicated that the liquid crystals transformed into smaller micelles in mucus. In addition, some microemulsions were aggregated into larger emulsions in mucus due to the microemulsion-mucin interaction. In this work, part of the structural change of microemulsions under the effect of lipase and mucus was revealed. However, there are still many questions to be solved, such as the mechanism of those structures absorbed by the intestinal epithelium, how to control the formation of the intermediate phases, which kind of structure can make drug to reach the highest bioavailability, how to monitor the structural change in vivo. Hence, far more work should be carried out to resolve those questions. Apart from FRET and SAXS, other techniques have been used or might be used to study the fate of nanoparticles in the GI tract, such as cryo-TEM, near-infrared fluorescent dye, the water-quenching environment-responsive fluorescent probes, quantum dot and aggregation-induced emission (AIE)18, 31 (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

Schematic illustrations showing the possible structural change of microemulsions under the effect of lipase and mucus.

4. Conclusion

To demonstrate the fate of microemulsions in the GI tract, we applied SAXS and FRET to monitor the structural change of four microemulsions (SME 1-4) in simulated gastrointestinal conditions, especially the effect of lipase and mucus. During the lipolysis of microemulsions, the liquid crystalline phases were observed by SAXS. Meanwhile, FRET spectra indicated micelles with smaller particle sizes were generated during lipolysis, and the presence of CaCl2, bile salts and lecithin accelerated the formation of micelles. We further investigated the structural change of digested microemulsions in the mucus layer. The SAXS spectra showed that the peaks from the liquid crystals disappeared, and the FRET spectra showed that structures with smaller particles sizes appeared. These results indicated that the liquid crystalline phases were transformed into micelles due to their interaction with mucus. The structural change of microemulsions in the GI tract would inevitably affect the delivery of drugs, including drug release, drug adsorption and drug distribution. This work helps researchers to better understand the fate of microemulsions in the GI tract and the drug performance in vivo. In this work, part of the structural change of microemulsions was revealed. However, there are still many questions to be solved and far more work should be carried out. In future work, the combination of SAXS and FRET with some other methods can provide deeper insight into the whole pathway of microemulsions in the GI tract, such as cryo-TEM.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81703606), the Educational Committee Foundation of Liaoning Province (Grant No. L2016026), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant no. wd01185). The authors thank the staff at the beamline BL16B1 of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for SAXS tests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Shekhawat P.B., Pokharkar V.B. Understanding peroral absorption: regulatory aspects and contemporary approaches to tackling solubility and permeability hurdles. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2017;7:260–280. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He C.X., He Z.G., Gao J.Q. Microemulsions as drug delivery systems to improve the solubility and the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;7:445–460. doi: 10.1517/17425241003596337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv X., Liu T., Ma H., Tian Y., Li L., Li Z. Preparation of essential oil-based microemulsions for improving the solubility, pH stability, photostability, and skin permeation of quercetin. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18:3097–3104. doi: 10.1208/s12249-017-0798-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li F., Hu R., Wang B., Gui Y., Cheng G., Gao S. Self-microemulsifying drug delivery system for improving the bioavailability of huperzine A by lymphatic uptake. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2017;7:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martins S., Sarmento B., Ferreira D.C., Souto E.B. Lipid-based colloidal carriers for peptide and protein delivery – liposomes versus lipid nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed. 2007;2:595–607. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trevaskis N.L., Charman W.N., Porter C.J.H. Lipid-based delivery systems and intestinal lymphatic drug transport: a mechanistic update. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:702–716. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter C.J., Pouton C.W., Cuine J.F., Charman W.N. Enhancing intestinal drug solubilisation using lipid-based delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:673–691. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dokania S., Joshi A.K. Self-microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS) - challenges and road ahead. Drug Deliv. 2015;22:675–690. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.896058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han S.F., Yao T.T., Zhang X.X., Gan L., Zhu C.L., Yu H.Z. Lipid-based formulations to enhance oral bioavailability of the poorly water-soluble drug anethol trithione: effects of lipid composition and formulation. Int J Pharm. 2009;379:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narang A.S., Delmarre D., Gao D. Stable drug encapsulation in micelles and microemulsions. Int J Pharm. 2007;345:9–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter C.J.H., Kaukonen A.M., Boyd B.J., Edwards G.A., Charman W.N. Susceptibility to lipase-mediated digestion reduces the oral bioavailability of danazol after administration as a medium-chain lipid-based microemulsion formulation. Pharm Res. 2004;21:1405–1412. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000036914.22132.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahan A., Hoffman A. Use of a dynamic in vitro lipolysis model to rationalize oral formulation development for poor water soluble drugs: correlation with in vivo data and the relationship to intra-enterocyte processes in rats. Pharm Res. 2006;23:2165–2174. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahan A., Hoffman A. The effect of different lipid based formulations on the oral absorption of lipophilic drugs: the ability of in vitro lipolysis and consecutive ex vivo intestinal permeability data to predict in vivo bioavailability in rats. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;67:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Driscoll C.M. Lipid-based formulations for intestinal lymphatic delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2002;15:405–415. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(02)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golding M., Wooster T.J. The influence of emulsion structure and stability on lipid digestion. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;15:90–101. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter C.J., Trevaskis N.L., Charman W.N. Lipids and lipid-based formulations: optimizing the oral delivery of lipophilic drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:231–248. doi: 10.1038/nrd2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fatouros D.G., Bergenstahl B., Mullertz A. Morphological observations on a lipid-based drug delivery system during in vitro digestion. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2007;31:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran T., Fatouros D.G., Vertzoni M., Reppas C., Mullertz A. Mapping the intermediate digestion phases of human healthy intestinal contents from distal ileum and caecum at fasted and fed state conditions. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;69:265–273. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salentinig S., Sagalowicz L., Leser M.E., Tedeschi C., Glatter O. Transitions in the internal structure of lipid droplets during fat digestion. Soft Matter. 2011;7:650–661. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fatouros D.G., Deen G.R., Arleth L., Bergenstahl B., Nielsen F.S., Pedersen J.S. Structural development of self nano emulsifying drug delivery systems (SNEDDS) during in vitro lipid digestion monitored by small-angle X-ray scattering. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1844–1853. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren D.B., Anby M.U., Hawley A., Boyd B.J. Real time evolution of liquid crystalline nanostructure during the digestion of formulation lipids using synchrotron small-angle X-ray scattering. Langmuir. 2011;27:9528–9534. doi: 10.1021/la2011937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezhdo O., Di Maio S., Le P., Littrell K.C., Carrier R.L., Chen S.H. Characterization of colloidal structures during intestinal lipolysis using small-angle neutron scattering. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;499:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.03.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas N., Mullertz A., Graf A., Rades T. Influence of lipid composition and drug load on the in vitro performance of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems. J Pharm Sci. 2012;101:1721–1731. doi: 10.1002/jps.23054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J.B., Lv Y., Zhao S., Wang B., Tan M.Q., Xie H.G. Effect of lipolysis on drug release from self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems (SMEDDS) with different core/shell drug location. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014;15:731–740. doi: 10.1208/s12249-014-0096-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boegh M., Nielsen H.M. Mucus as a barrier to drug delivery – understanding and mimicking the barrier properties. Basic Clin Pharm Toxicol. 2015;116:179–186. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ci L., Huang Z., Liu Y., Liu Z., Wei G., Lu W. Amino-functionalized poloxamer 407 with both mucoadhesive and thermosensitive properties: preparation, characterization and application in a vaginal drug delivery system. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2017;7:593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karamanidou T., Karidi K., Bourganis V., Kontonikola K., Kammona O., Kiparissides C. Effective incorporation of insulin in mucus permeating self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;97:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X., Chen D., Le C., Zhu C., Gan Y., Hovgaard L. Novel mucus-penetrating liposomes as a potential oral drug delivery system: preparation, in vitro characterization, and enhanced cellular uptake. Int J Nanomed. 2011;6:3151–3162. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S25741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griesser J., Burtscher S., Kollner S., Nardin I., Prufert F., Bernkop-Schnurch A. Zeta potential changing self-emulsifying drug delivery systems containing phosphorylated polysaccharides. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2017;119:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2017.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roger E., Gimel J.-C., Bensley C., Klymchenko A.S., Benoit J.-P. Lipid nanocapsules maintain full integrity after crossing a human intestinal epithelium model. J Control Release. 2017;253:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia F., Fan W., Jiang S., Ma Y., Lu Y., Qi J. Size-dependent translocation of nanoemulsions via oral delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:21660–21672. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b04916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sek L., Porter C.J., Kaukonen A.M., Charman W.N. Evaluation of the in-vitro digestion profiles of long and medium chain glycerides and the phase behaviour of their lipolytic products. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2002;54:29–41. doi: 10.1211/0022357021771896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sek L., Porter C.J., Charman W.N. Characterisation and quantification of medium chain and long chain triglycerides and their in vitro digestion products, by HPTLC coupled with in situ densitometric analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2001;25:651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(00)00528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J.B., Lv Y., Wang B., Zhao S., Tan M.Q., Lv G.J. Influence of microemulsion–mucin interaction on the fate of microemulsions diffusing through pig gastric mucin solutions. Mol Pharm. 2015;12:695–705. doi: 10.1021/mp500475y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shan W., Zhu X., Liu M., Li L., Zhong J., Sun W. Overcoming the diffusion barrier of mucus and absorption barrier of epithelium by self-assembled nanoparticles for oral delivery of insulin. ACS Nano. 2015;9:2345–2356. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuster B.S., Suk J.S., Woodworth G.F., Hanes J. Nanoparticle diffusion in respiratory mucus from humans without lung disease. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3439–3446. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chamieh J., Merdassi H., Rossi J.-C., Jannin V., Demarne F., Cottet H. Size characterization of lipid-based self-emulsifying pharmaceutical excipients during lipolysis using Taylor dispersion analysis with fluorescence detection. Int J Pharm. 2018;537:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinke S.K., Roth S.V., Santoro G., Vieira J., Heinrich S., Palzer S. Tracking structural changes in lipid-based multicomponent food materials due to oil migration by microfocus small-angle X-ray scattering. Acs Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:9929–9936. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b02092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mouri A., Diat O., El Ghzaoui A., Bauer C., Maurel J.C., Devoisselle J.-M. Phase behavior of reverse microemulsions based on Peceol (R) J Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;416:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan J., Hawley A., Rades T., Boyd B. In situ lipolysis and synchrotron Small-Angle X-ray Scattering for the direct determination of the precipitation and solid-state form of a poorly water-soluble drug during digestion of a lipid-based formulation. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105:2631–2639. doi: 10.1002/jps.24634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phan S., Salentinig S., Gilbert E., Darwish T.A., Hawley A., Nixon-Luke R. Disposition and crystallization of saturated fatty acid in mixed micelles of relevance to lipid digestion. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;449:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi J.Y., Tian F., Lyu J., Yang M. Nanoparticle based fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) for biosensing applications. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3:6989–7005. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00885a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J., Owen S.C., Shoichet M.S. Stability of self-assembled polymeric micelles in serum. Macromolecules. 2011;44:6002–6008. doi: 10.1021/ma200675w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ray P.C., Fan Z., Crouch R.A., Sinha S.S., Pramanik A. Nanoscopic optical rulers beyond the FRET distance limit: fundamentals and applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:6370–6404. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60476d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pan Y., Nitin N. Real-time measurements to characterize dynamics of emulsion interface during simulated intestinal digestion. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2016;141:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chakraborty S., Shukla D., Mishra B., Singh S. Lipid – an emerging platform for oral delivery of drugs with poor bioavailability. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;73:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cone R.A. Barrier properties of mucus. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]