Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Rapid repeat pregnancy within 12 months of a live birth is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. We evaluated the risk for rapid repeat pregnancy among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities, with whom sharing of information about pregnancy planning and contraception may be inadequate.

METHODS:

We accessed population-based health administrative data for all women with an index live birth in Ontario, Canada, for the period 2002–2013. We used modified Poisson regression to compare relative risks (RRs) for a rapid repeat pregnancy within 12 months of the index live birth in women with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities, first adjusting for demographic factors and then additionally adjusting for social, health and health care disparities.

RESULTS:

We compared 2855 women with intellectual and developmental disabilities and 923 367 women without such disabilities. At the index live birth, women with intellectual and developmental disabilities were more likely to be younger than 25 years of age (46.8% v. 18.2%) and to be disadvantaged on each measure of social, health and health care disparities. These women had a higher rate of rapid repeat pregnancy than those without such disabilities (7.6% v. 3.9%; adjusted RR 1.34, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.18–1.54, after controlling for demographic factors). This risk was attenuated upon further adjustment for social, health and health care disparities (adjusted RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.87–1.14).

INTERPRETATION:

Rapid repeat pregnancy, which was more common among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities, may be explained by social, health and health care disparities. To optimize reproductive health, multifactorial approaches to address the marginalization experienced by this population are likely needed.

Rapid repeat pregnancy within 12 months of a live birth is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, with previous meta-analyses showing increased risks for stillbirth (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–1.71), fetal growth restriction (adjusted OR 1.26, 95% CI 1.18–1.33), preterm birth (adjusted OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.24–2.58) and early neonatal mortality (adjusted OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.02–1.64).1,2 There is debate about whether these risks are due to inadequate recovery from the prior pregnancy, including depleted maternal nutrient stores, or confounding by other factors such as socioeconomic status.2 Nevertheless, high rates of rapid repeat pregnancy in North America, as well as research showing that as many as 55% of such pregnancies are unintended,3 make prevention of rapid repeat pregnancy a public health priority. Adolescents and women with low education or income have been shown to be at high risk for rapid repeat pregnancy4–6 and have been the focus of public health efforts.3 Women with intellectual and developmental disabilities, who exhibit some of the same risk factors for rapid repeat pregnancy, such as suboptimal access to contraception and other family planning services,7 have yet to be studied.

Intellectual and developmental disabilities affect 1 in every 100 adults8 and are characterized by cognitive limitations and difficulties with conceptual, social and practical skills.9 Examples of such disabilities include autism, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and trisomy 21, but most are nonspecific diagnoses associated with mild intellectual impairment.9 Sterilization and long-term admission to an institution have historically limited child-bearing in this population.10 However, these practices are now uncommon,11 such that young women with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities have similar fertility rates.12,13 Given stigma and other barriers to education and employment, as well as the financial burden associated with disability, women with intellectual and developmental disabilities are more likely than their peers to live in poverty. Poverty, combined with inadequate access to health care and poor social support, has further downstream effects in this population, including elevated rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidities.14–17 According to these markers of disadvantage, it is plausible that women with intellectual and developmental disabilities may be at increased risk for rapid repeat pregnancy. We compared the risk of rapid repeat pregnancy among women with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Methods

Study design and setting

We undertook a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada, where health care is provided at no direct cost to residents. The cohort comprised women who had a live birth between Apr. 1, 2002, and Mar. 31, 2013, who were followed for 12 months to ascertain the primary outcome.

Data sources

We accessed and analyzed multiple databases at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. Using a unique encoded identifier, person-level sociodemographic and health data were linked deterministically; social services data were linked probabilistically with these data, on the basis of name, birth date, sex and postal code.18 We extracted data from the Registered Persons Database (birth date, postal code, date of death), the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database (physician billing data), the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (data on emergency department visits), the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (medical and psychiatric hospital admission data), the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (psychiatric hospital admission data), the Ontario Drug Benefits database (publicly funded drug benefit data) and the Ontario Ministry of Community and Social Services, now the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (Ontario Disability Support Program data).18 These databases are valid for sociodemographic data, primary diagnoses and physician billing claims.19

Exposure

We derived our sample from a cohort of Ontarian adults with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities who were 18 to 64 years of age as of Apr. 1, 2009.20 We classified individuals as having intellectual and developmental disabilities if they had a relevant diagnosis recorded for at least 1 hospital admission or emergency department visit or at least 2 outpatient physician visits, recorded since database inception or listed as the reason for receipt of Ontario Disability Support Program payments. This definition was based on Ontario legislation21 and clinical practice8 and includes intellectual disability, genetic conditions resulting in intellectual disability (e.g., trisomy 21) and developmental disabilities (e.g., autism).18 The resulting prevalence of intellectual and developmental disabilities in Ontarian adults (0.8%)20 is consistent with international meta-analyses.8 From this cohort, we identified women with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities aged 18 to 49 years who had a live birth at gestational age of at least 20 weeks between Apr. 1, 2002, and Mar. 31, 2013. The first live birth in the study period was identified using MOMBABY, a linked maternal–newborn data set, derived from the Discharge Abstract Database, which identifies more than 98.0% of Ontario births.22

Outcome

Rapid repeat pregnancy is variously defined in the literature as a “birth to conception” or “birth to birth” interval of less than 12, 18 or 24 months.1–6 In our study, gestational age and therefore conception date, calculated by subtracting gestational age from the delivery date, was not available for pregnancy losses (miscarriages at < 20 wk and stillbirths at ≥ 20 wk gestation) or induced abortions. As such, we could not identify pregnancies conceived but not ending in the follow-up period. We therefore defined rapid repeat pregnancy as a live birth, pregnancy loss or induced abortion occurring within 12 months of the index live birth, as recorded in MOMBABY (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170932/-/DC1). Ascertainment of live births, stillbirths and induced abortions is complete and accurate,22,23 but some early miscarriages may have been missed. To avoid misclassification of complications from the index live birth as a rapid repeat pregnancy, such as misclassifying dilatation and curettage for retained products of conception as a subsequent induced abortion, we started counting rapid repeat pregnancies at 3 months after the index live birth. In additional analyses, we tested less specific definitions of rapid repeat pregnancy within 18 and 24 months of the index live birth.

Covariables

We measured the following covariables as of the date of the index live birth: age, parity, rural residence, neighbourhood income quintile, social assistance, chronic medical conditions, mental illness and continuity of primary care. We measured rural residence and neighbourhood income quintile by linking maternal residential postal code with census information; rural communities were those with fewer than 10 000 residents.24 We measured social assistance using Ontario Drug Benefit eligibility as a proxy, because most individuals younger than 65 years of age with these benefits also receive social assistance.25 We measured chronic medical conditions using collapsed ambulatory diagnostic groups from the Johns Hopkins Clinical Groups System.26 Mental illness comprised psychotic27 and nonpsychotic mental illness and substance use disorders. We measured continuity of primary care using the Usual Provider Continuity Index, which is calculated as the proportion of visits made to the usual primary care provider, for example, the family physician, divided by the total number of visits to all primary care providers in the 2 years before the index live birth.28

Statistical analysis

We described baseline characteristics using frequencies and percentages, and we used standardized differences to compare women with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities.29 We used modified Poisson regression to directly estimate the relative risk (RR) and 95% CI of rapid repeat pregnancy by 12 months.30 We produced 2 adjusted models: model 1 was adjusted for the demographic characteristics of age, parity and rurality. Model 2 also had adjustment for the following social, health and health care disparities that might explain the impact of disability status on rapid repeat pregnancy risk: neighbourhood income quintile, social assistance, chronic medical conditions, mental illness and continuity of primary care.14–17 We described the rate of rapid repeat pregnancy in each month of follow-up using cumulative incidence. Finally, we described frequencies and percentages of rapid repeat pregnancies ending in live birth, pregnancy loss or induced abortion.

We conducted several additional analyses. First, to model 2, we added interaction terms between disability status and factors expected to directly affect rapid repeat pregnancy risk:4–6 age (< 25 yr v. ≥ 25 yr), neighbourhood income (quintiles 1–2 v. 3–5), social assistance (receiving v. not receiving), mental illness (any mental illness or substance use disorder v. none) and continuity of primary care (infrequent use or low continuity v. moderate or high continuity). We then stratified model 2 on these variables. Second, because the risk of unintended pregnancy in high-risk groups increases with the number of prior pregnancies,1 we re-ran analyses in primiparas. Finally, we re-ran analyses defining rapid repeat pregnancy as occurring within 18 and 24 months of the index live birth.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board.

Results

We identified 2855 women with intellectual and developmental disabilities and 923 367 women without such disabilities who had an index live birth in the period 2002–2013. Women with intellectual and developmental disabilities were more likely than those without to be younger than 25 years of age (46.8% v. 18.2%); to live in rural areas (14.0% v. 9.5%) or neighbourhoods in the 2 lowest income quintiles (60.6% v. 41.1%); to receive social assistance (39.4% v. 3.7%); to have stable (36.4% v. 27.3%) and unstable (21.1% v. 13.2%) chronic medical conditions, psychotic (3.8% v. 0.2%) and nonpsychotic (50.0% v. 27.4%) mental illness, and substance use disorders (8.5% v. 2.1%); and to have low continuity of primary care (27.8% v. 21.1%) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of women with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities in a study of rapid repeat pregnancy

| Characteristic | Study group; no. (%) of women* | Standardized difference† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With disabilities n = 2855 |

Without disabilities n = 923 367 |

||

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 26.3 ± 6.4 | 29.7 ± 5.5 | |

| ≤ 19 | 413 (14.5) | 32 704 (3.5) | 0.39 |

| 20–24 | 923 (32.3) | 135 541 (14.7) | 0.42 |

| 25–29 | 665 (23.3) | 277 101 (30.0) | −0.15 |

| 30–34 | 489 (17.1) | 298 993 (32.4) | −0.36 |

| 35–39 | 283 (9.9) | 146 022 (15.8) | −0.18 |

| ≥ 40 | 82 (2.9) | 33 006 (3.6) | −0.04 |

| Multiparous at the index live birth | 811 (28.4) | 223 163 (24.2) | 0.10 |

| Urban residence‡ | 2453 (86.0) | 834 993 (90.5) | −0.14 |

| Neighbourhood income quintile§ | |||

| Q1 (lowest) | 1105 (39.0) | 195 423 (21.3) | 0.39 |

| Q2 | 612 (21.6) | 181 885 (19.8) | 0.04 |

| Q3 | 452 (15.9) | 187 364 (20.4) | −0.12 |

| Q4 | 361 (12.7) | 193 269 (21.0) | −0.22 |

| Q5 (highest) | 306 (10.8) | 161 906 (17.6) | −0.20 |

| Receipt of social assistance | 1124 (39.4) | 34 135 (3.7) | 0.96 |

| Stable chronic medical condition | 1039 (36.4) | 251 995 (27.3) | 0.20 |

| Unstable chronic medical condition | 601 (21.1) | 121 993 (13.2) | 0.21 |

| Psychotic mental illness | 108 (3.8) | 1457 (0.2) | 0.26 |

| Nonpsychotic mental illness | 1428 (50.0) | 253 420 (27.4) | 0.47 |

| Substance use disorder | 242 (8.5) | 19 173 (2.1) | 0.29 |

| Continuity of primary care ≤ 2 yr before the index live birth | |||

| Infrequent use (< 3 primary care visits in 2 yr) | 119 (4.2) | 46 205 (5.0) | −0.04 |

| Low (< 50% visits to same provider) | 795 (27.8) | 195 270 (21.2) | 0.16 |

| Moderate (50%–79% visits to same provider) | 1025 (35.9) | 332 006 (36.0) | 0.00 |

| High (≥ 80% visits to same provider) | 916 (32.1) | 349 886 (37.9) | −0.12 |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Except where indicated otherwise.

Standardized differences > 0.10 are considered to be clinically meaningful.29

n = 215 (0.02%) observations had missing data; among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities, the number with missing data was too small to allow missing data to be reported separately by group.

n = 3539 (0.4%) observations had missing data, consisting of 19 (0.7%) among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities and 3520 (0.4%) among women without such disabilities.

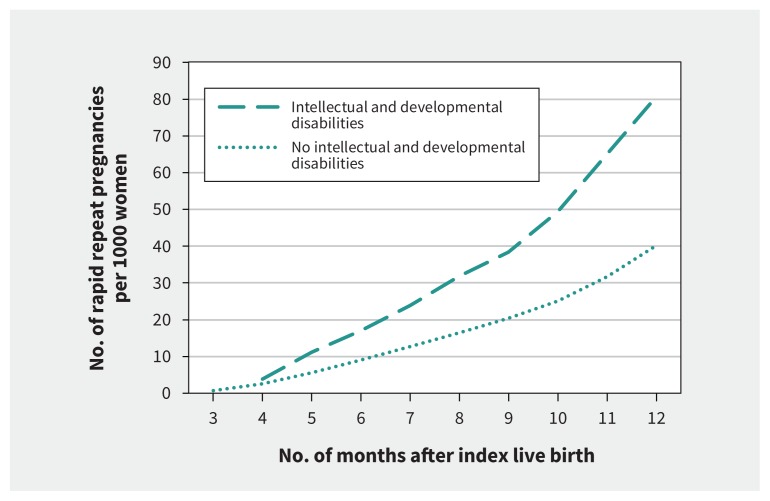

Rapid repeat pregnancy within 12 months of the index live birth occurred in 216 (7.6%) of the 2855 women with intellectual and developmental disabilities and 35 948 (3.9%) of the 923 367 women without such disabilities. This risk remained elevated after adjustment for demographic factors (adjusted RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.18–1.54) but was attenuated after further adjustment for social, health and health care disparities (adjusted RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.87–1.14). Cumulative incidence curves showed that rapid repeat pregnancies tended to occur slightly closer to the index live birth for women with intellectual and developmental disabilities than for women without such disabilities (Figure 1). Among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities, rapid repeat pregnancy most often ended in induced abortion (106 [49.1%]), followed by live birth (72 [33.3%]) and pregnancy loss (38 [17.6%]), whereas among women without such disabilities, pregnancies most often ended in induced abortion (21 245 [59.1%]), followed by pregnancy loss (7765 [21.6%]) and live birth (6938 [19.3%]) (p < 0.001).

Figure 1:

Cumulative incidence of rapid repeat pregnancy occurring within 12 months of a prior live birth, among women with (thick dashed line) and without (dotted line) intellectual and developmental disabilities. To avoid misclassification of complications from the index live birth as a rapid repeat pregnancy, rapid repeat pregnancies were counted starting at 3 months after the index live birth. Because of the small number of events among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities, the data for 3 and 4 months are combined, to protect individuals’ privacy.

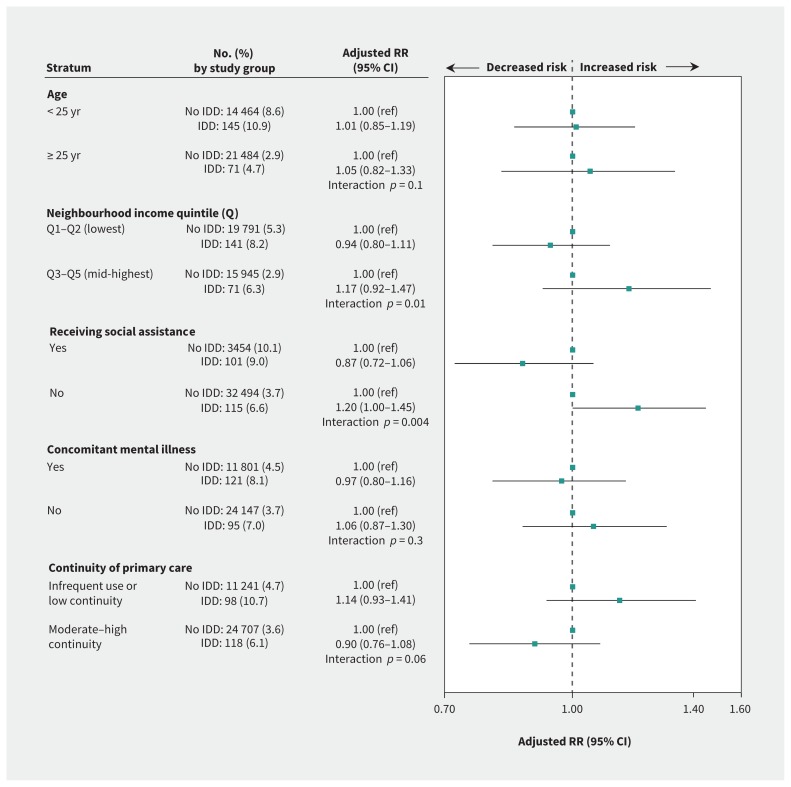

Interaction terms between disability status and neighbourhood income (p = 0.01) and receipt of social assistance (p = 0.004) were statistically significant. Stratified analyses suggested that the impact of disability status was weakest for women living in lower-income neighbourhoods and those receiving social assistance. All other interaction terms were nonsignificant (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Adjusted risk of rapid repeat pregnancy occurring within 12 months of a prior live birth among women with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs), stratified by factors expected to directly affect the risk of rapid repeat pregnancy. Data are presented as number (%) of rapid repeat pregnancies among women with and without IDDs, adjusted relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations, and p values for interaction terms between disability status and effect modifiers. Adjusted stratified models controlled for all variables except that used for stratification, from among age, parity, urban residence, neighbourhood income quintile, social assistance, stable and unstable chronic medical conditions, mental illness and continuity of primary care. Note: ref = reference.

Primiparas with intellectual and developmental disabilities, relative to those without such disabilities, were at increased risk for rapid repeat pregnancy after adjustment for demographic characteristics (adjusted RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.09–1.50), but not after additional adjustment for social, health and health care disparities (adjusted RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.84–1.16) (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170932/-/DC1).

When the outcome window was extended to 18 or 24 months, women with intellectual and developmental disabilities, relative to those without such disabilities, were at increased risk for rapid repeat pregnancy after adjustment for demographic characteristics (18 mo, adjusted RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.22–1.45; 24 mo, adjusted RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.08–1.24) (Appendices 3 and 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170932/-/DC1). After further adjustment for social, health and health care disparities, the risk at 18 months remained statistically significant (adjusted RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.01–1.20), whereas the risk at 24 months did not (adjusted RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.99–1.14).

Other variables independently associated with rapid repeat pregnancy were age younger than 25 years (adjusted RR 2.75, 95% CI 2.69–2.82), multiparity (adjusted RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.19–1.26), urban residence (adjusted RR 1.35, 95% CI 1.30–1.40), low neighbourhood income (adjusted RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.43–1.49), receipt of social assistance (adjusted RR 1.71, 95% CI 1.65–1.77), mental illness or substance use disorder (adjusted RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.11–1.16), and infrequent use or low continuity of primary care (adjusted RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.14–1.19) (Table 2). Appendix 5 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170932/-/DC1) shows the individual impacts of covariables on the unadjusted association between disability status and rapid repeat pregnancy. In all models, receipt of social assistance had the greatest impact, followed by age younger than 25 years and low neighbourhood income.

Table 2:

Unadjusted and adjusted relative risks for rapid repeat pregnancy occurring within 12 months of a prior live birth among women with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities

| Measure | No. (%) with rapid repeat pregnancy | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Model 1* adjusted RR (95% CI) | Model 2† adjusted RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intellectual and developmental disabilities | ||||

| Absent (n = 923 367) | 35 948 (3.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Present (n = 2855) | 216 (7.6) | 1.94 (1.70–2.22) | 1.34 (1.18–1.54) | 1.00 (0.87–1.14) |

| Age, yr | ||||

| ≥ 25 | 21 555 (2.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| < 25 | 14 609 (8.6) | 3.02 (2.96–3.09) | 3.20 (3.13–3.27) | 2.75 (2.69–2.82) |

| Parity at the index live birth | ||||

| Primiparous | 27 211 (3.9) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Multiparous | 8953 (4.0) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 1.28 (1.25–1.31) | 1.22 (1.19–1.26) |

| Region of residence | ||||

| Rural | 3028 (3.4) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Urban | 33 121 (4.0) | 1.15 (1.11–1.20) | 1.39 (1.34–1.44) | 1.35 (1.30–1.40) |

| Neighbourhood income quintile | ||||

| Q3–Q5 (mid to highest) | 16 016 (3.0) | 1.00 (ref) | NA | 1.00 (ref) |

| Q1–Q2 (lowest) | 19 932 (5.3) | 1.79 (1.75–1.82) | NA | 1.46 (1.43–1.49) |

| Social assistance | ||||

| Not receiving | 32 609 (3.7) | 1.00 (ref) | NA | 1.00 (ref) |

| Receiving | 3555 (10.1) | 2.75 (2.66–2.85) | NA | 1.71 (1.65–1.77) |

| Stable chronic medical condition | ||||

| Absent | 26 887 (4.0) | 1.00 (ref) | NA | 1.00 (ref) |

| Present | 9277 (3.7) | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) | NA | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) |

| Unstable chronic medical condition | ||||

| Absent | 31 610 (3.9) | 1.00 (ref) | NA | 1.00 (ref) |

| Present | 4554 (3.7) | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) | NA | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) |

| Mental illness or substance use disorder | ||||

| Absent | 24 242 (3.7) | 1.00 (ref) | NA | 1.00 (ref) |

| Present | 11 922 (4.5) | 1.23 (1.21–1.26) | NA | 1.13 (1.11–1.16) |

| Continuity of primary care | ||||

| Moderate to high continuity | 24 825 (3.6) | 1.00 (ref) | NA | 1.00 (ref) |

| Infrequent use or low continuity | 11 339 (4.7) | 1.29 (1.26–1.32) | NA | 1.16 (1.14–1.19) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, NA = not applicable, ref = reference, RR = relative risk.

Model 1 was adjusted for the following demographic factors: age, parity and rurality of residence.

Model 2 was additionally adjusted for the following social, health and health care factors that might explain the impact of disability status on risk of rapid repeat pregnancy: neighbourhood income quintile, social assistance, chronic medical conditions, mental illness and continuity of primary care.

Interpretation

Women with intellectual and developmental disabilities, relative to those without such disabilities, were at increased risk for rapid repeat pregnancy within 12 months of a live birth before we accounted for the reasons for this increased risk. However, this risk was clearly attenuated after adjustment for social, health and health care disparities. Attenuation of the impact of disability on rapid repeat pregnancy risk was also greatest in high-risk groups defined by lower income and receipt of social assistance. The results were similar among primiparas and when broader definitions of rapid repeat pregnancy were used.

We hypothesized that women with intellectual and developmental disabilities would have higher rates of rapid repeat pregnancy than those without such disabilities because of, in part, their social, health and health care disparities.14–17 Compared with women with better resources, those who have low income, for example, tend to be less well equipped to advocate with their respective partners for consistent use of contraception and appropriate interpregnancy intervals; they may also have poorer access to effective family planning services.4–6 Given that women with intellectual and developmental disabilities are more likely than their peers to experience marginalization in the form of poverty, isolation, and medical or mental illness,14–17 it is not surprising that their risk for rapid repeat pregnancy was elevated in the unadjusted analyses. Notably, the importance of low income and social assistance in the adjusted and stratified analyses supports the idea that social vulnerability — whether at an individual or system level — explains the impact of disability status on risk of rapid repeat pregnancy.

Our findings build on the only related study, a nested case–control study using the US National Longitudinal Survey of Youth,31 which found that low cognitive ability was related to rapid repeat pregnancy within 24 months among 18-year-old women. However, that study focused on adolescents and measured cognitive ability in terms of limitations in language and arithmetic skills, which may not reflect intellectual and developmental disabilities per se. Furthermore, the authors controlled only for age at first sexual encounter, sexual health education, education level and poverty, which left open the possibility that the impact of cognitive ability could be explained by other markers of marginalization. The results of our current study add to the literature by suggesting that the rate of rapid repeat pregnancy is higher among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities specifically and that a combination of social, health and health care disparities could explain this risk.

Rapid repeat pregnancy frequently reflects vulnerability in a woman’s ability to make informed reproductive decisions32 and lack of access to family planning services.2,33 Our data signal the need to address systemic vulnerabilities in marginalized groups to improve reproductive outcomes. Given that women are more connected to the health care system around the time of delivery, the perinatal period may be an ideal time to intervene.34,35

Limitations

Some women with intellectual and developmental disabilities may have been misclassified if they did not have a health care encounter in which their disability was recorded and were not recipients of assistance through the Ontario Disability Support Program. The disability definition included conditions with variability in functioning.9 Although there could be heterogeneity in risk associated with these characteristics, we retained a definition with policy21 and clinical9 relevance. Furthermore, because our cohort was restricted to women with a prior live birth, captured disabilities were likely fairly homogeneous, with mild to moderate severity.36

Our outcome also had limitations. Because we had no data on conception date for pregnancy losses or induced abortions, we were unable to measure rapid repeat pregnancy as such.1 Instead, we measured pregnancies that ended within 12 months of the index live birth, with additional analyses exploring broader definitions. We also could not capture deliveries outside of health care facilities,22 including home births and early pregnancy losses, or induced abortions performed outside Ontario.23 We could not determine pregnancy intendedness; however, most rapid repeat pregnancies are unintended.3 Finally, we had no data on living situation, marital status, sexual abuse,37 reproductive knowledge,38,39 breastfeeding and other factors that could affect fertility, or apprehension of the first infant by child protective services.40 The roles of these factors should be examined in future research.

Conclusion

High unadjusted rates of rapid repeat pregnancy among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities suggest that such women frequently experience reproductive vulnerability. The ability of social, health and health care disparities to explain the increased risk suggests that marginalization should be addressed in multipronged approaches directed at these disparities, if improvements in reproductive health are to be achieved.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Hilary Brown had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Hilary Brown and Simone Vigod contributed to the study concept; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; and drafting and revision of the manuscript. Joel Ray, Ning Liu and Yona Lunsky contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data and to critical revision of the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors gratefully acknowledge the Province of Ontario for its support of this study through its research grants program. This study is part of the Health Care Access Research and Developmental Disabilities (H-CARDD) Program and was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from all funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI.

References

- 1.Wendt A, Gibbs CM, Peters S, et al. Impact of increasing inter-pregnancy interval on maternal and infant health. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26(Suppl 1):239–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermúdez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2006;295:1809–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gemmill A, Lindberg LD. Short interpregnancy intervals in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boardman LA, Allsworth J, Phipps MG, et al. Risk factors for unintended versus intended rapid repeat pregnancies among adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2006;39:597.e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appareddy S, Pryor J, Bailey B. Inter-pregnancy interval and adverse outcomes: evidence for an additional risk in health disparate populations. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017;30:2640–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett IM, Culhane JF, McCollum KF, et al. Unintended rapid repeat pregnancy and low education status: Any role for depression and contraceptive use? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:749–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenwood NW, Wilkinson J. Sexual and reproductive health care for women with intellectual disabilities: a primary care perspective. Int J Family Med 2013;2013:642472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maulik PK, Mascarenhas MN, Mathers CD, et al. Prevalence of intellectual disability: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res Dev Disabil 2011;32:419–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Intellectual disability: definition, classification, and systems of supports. 11th ed Washington: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kempton W, Kahn E. Sexuality and people with intellectual disabilities: a historical perspective. Sex Disabil 1991;9:93–111. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aunos M, Feldman MA. Attitudes towards sexuality, sterilization and parenting rights of persons with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2002;15:285–96. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Position paper 11a: Maternity care for women with disabilities. London (UK): Royal College of Midwives; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown HK, Lunsky Y, Wilton AS, et al. Pregnancy in women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2016;38:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emerson E. Poverty and people with intellectual disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2007;13:107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walter-Brice A, Cox R, Priest H, et al. What do women with learning disabilities say about their experiences of domestic abuse within the context of their intimate partner relationships? Disabil Soc 2012;27:503–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Havercamp SM, Scott HM. National health surveillance of adults with disabilities, adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and adults with no disabilities. Disabil Health J 2015;8:165–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper SA, Smiley E, Morrison J, et al. Mental ill-health in adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence and associated factors. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin E, Balogh R, Isaacs B, et al. Strengths and limitations of health and disability support administrative databases for population-based health research in intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Policy Pract Intell Disabil 2015;11:235–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JI, Young WA. A summary of studies on the quality of health care administrative databases in Canada. In: Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, et al., editors. Patterns of health care in Ontario: the ICES practice atlas. 2nd ed. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 1996:339–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin E, Balogh R, Cobigo V, et al. Using administrative health data to identify individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a comparison of algorithms. J Intellect Disabil Res 2013;57:462–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Services and Supports to Promote the Social Inclusion of Persons with Developmental Disabilities Act, 2008, S.O. 2008, c. 14 Available: www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/08s14?search=e+laws (accessed 2018 Feb. 13).

- 22.CANSIM Table 102-4516: live births and fetal deaths (stillbirths) by place of birth (hospital and non-hospital), Canada, provinces and territories: annual, 2006. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2006. Available: www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1024516 (accessed 2018 Feb. 13). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Important notes regarding coverage. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2014. Available: www.cihi.ca/en/ta_11_alldatatables20130221_en.pdf (accessed 2018 Feb. 13). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urquia ML, Frank JW, Glazier RH, et al. Birth outcomes by neighbourhood income and recent immigration in Toronto. Health Rep 2007;18:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muldoon L, Rayner J, Dahrouge S. Patient poverty and workload in primary care: study of prescription drug benefit recipients in community health centres. Can Fam Physician 2013;59:384–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Johns Hopkins ACG® System: excerpts from technical reference guide version 9.0. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurdyak P, Lin E, Green D, et al. Validation of a population-based algorithm to detect chronic psychotic illness. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60:362–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jee SH, Cabana MD. Indices for continuity of care: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 2006;63:158–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput 2009;38:1228–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shearer DL, Mulvihill BA, Klerman LV, et al. Association of early childbearing and low cognitive ability. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2002;34:236–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cha S, Chapman DA, Wan W, et al. Discordant pregnancy intentions in couples and rapid repeat pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:494.e1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masinter LM, Dina B, Kjerulff K, et al. Short interpregnancy intervals: results from the first baby study. Womens Health Issues 2017;27:426–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: Do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:481.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engin-Ustün Y, Ustün Y, Cetin F. Effect of postpartum counseling on postpartum contraceptive use. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007;275:429–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llewellyn G, Traustadottir R, McConnell D, et al., editors. Parents with intellectual disabilities: past, present, and futures. Malden (MA): John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGuire BE, Bayley AA. Relationships, sexuality, and decision-making capacity in people with an intellectual disability. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2011;24:398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grieve A, McLaren S, Lindsay WR. An evaluation of research and training resources for the sex education of people with moderate to severe learning disabilities. Br J Learn Disabil 2007;35:30–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isler A, Beytut TD, Conk Z. Sexuality in adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Sex Disabil 2009;27:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Booth T, Booth W, McConnell D. The prevalence and outcomes of care proceedings involving parents with learning disabilities in the family courts. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2005;18:7–17. [Google Scholar]