Abstract

This study is to investigate the characteristic features of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) that differentiating it from herpetic epithelial keratitis (HEK) using anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT). Medical records of three eyes of each AK and herpetic keratitis who had AS-OCT examination were reviewed in this study. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy and AS-OCT was performed on the initial visit and on every follow-up visits in all patients. In all three AK cases, reflective bands in the corneal stroma that correspond to the area of radial keratoneuritis were observed. The depth of the reflective bands varied in each case. After AK treatment, slit-lamp biomicroscopy confirmed that radial keratoneuritis had resolved and AS-OCT confirmed that reflective bands in the corneal stroma had also disappeared in all patients. Unlike the AS-OCT results found in AK, highly reflective HEK lesions were observed only in the subepithelial area, not in the stroma. AS-OCT seems to be helpful analyzing the specific depth of the lesion which enables to distinguish AK from HEK.

Keywords: acanthamoeba, optical coherence tomography, herpes, herpetic keratitis

INTRODUCTION

Although acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is relatively uncommon, when its diagnosis is delayed or incorrect, it can cause severe ocular damage. Recently, it was found that the main cause of AK is the improper use of contact lenses, including soft contact, hard contact, and orthokeratology lenses[1]–[2]. The clinical manifestations of AK include severe pain, corneal epithelial defect, corneal haze, and the most characteristic manifestation, radial keratoneuritis[3]. Although AK presents with characteristic signs, it is known to mimic herpetic epithelial keratitis (HEK)[4]. A definitive AK diagnosis is made by confirming its cytopathology using specific staining or culturing, a time-intensive process[4].

High-resolution anterior-segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) allows the non-contact measurement and non-invasive imaging of microscopic structures, including the epithelium, Bowman layer, stroma, Descemet membrane, and endothelium[5]–[11]. Yamazaki et al[3] reported that AS-OCT provides novel and detailed visual information about radial keratoneuritis in patients with early-stage AK.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the characteristic features of AK that differentiating it from HEK using AS-OCT.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This study adheres to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The medical records of three patients with AK and three with herpetic keratitis were reviewed in this study, such that each group was composed of three eyes. All patients were examined using AS-OCT (Spectralis; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) with an anterior segment module that uses raster and single-scan with high-resolution acquisition at a speed of 40 000 A-scans per second, an axial resolution of 3.9 to 7 µm, and a transverse resolution of 14 µm. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy and AS-OCT was performed on all patients during the initial and every subsequent follow-up visit.

RESULTS

Acanthamoeba Keratitis Patients

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics, clinical ocular histories, and treatments for all AK patients. The use of soft contact lenses was the cause of AK for all the patients. A definitive diagnosis of AK was confirmed by plate culturing tissue obtained by corneal scraping. The corneal tissue was placed onto the center of a 1.5% non-nutrient agar plate covered with a lawn of Escherichia coli. Plates were sealed with parafilm, incubated at 30°C, and screened by inverted phase contrast microscopy. In all cases, patients were initially treated with 100 mg of oral itraconazole, topical 0.02% polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) and 0.02% chlorhexidine. Clinical outcomes were fair with visual recovery in all AK cases.

Table 1. Characteristics, clinical ocular histories and treatments of AK patients.

| Case | Sex/age | Laterality | Risk factor | Slit lamp exam | Culture | Treatment | Outcome |

| 1 | F/15 | OS | SCL | Pseudodenrites, radial keratoneuritis, subepithelial infiltration, conjuctival injection | Cyst trophozoite | Epithelial debridement, topical 0.02% hexamedine, topical 0.02% PHMB, oral itraconazole | Good |

| 2 | F/18 | OD | Cosmetic SCL | Pseudodenrites, radial keratoneuritis, subepithelial infiltration, conjuctival injection | Cyst | Epithelial debridement, topical 0.02% hexamedine, topical 0.02% PHMB, oral itraconazole | Good |

| 3 | F/18 | OS | SCL | Pseudodenrites, radial keratoneuritis, subepithelial infiltration, conjuctival injection | Cyst | Epithelial debridement, topical 0.02% hexamedine, topical 0.02% PHMB, oral itraconazole | Good |

SCL: Soft contact lenses; PHMB: Polyhexamethylene biguanide.

In all three AK cases, we observed reflective bands in the corneal stroma that corresponded to the area of radial keratoneuritis (case 1: Figure 1A; case 2: Figure 2A; case 3: Figure 3A). The depth of the reflective bands varied in each case. After AK treatment, slit-lamp biomicroscopy confirmed that radial keratoneuritis had resolved and AS-OCT confirmed that reflective bands in the corneal stroma had also disappeared in all patients (case 1: Figure 1B; case 2: Figure 2B; case 3: Figure 3B).

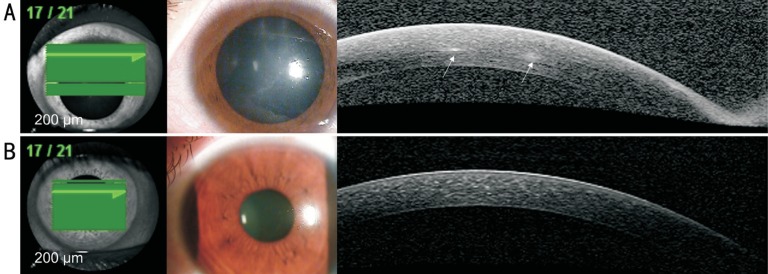

Figure 1. AK case 1.

A: Radial keratoneuritis observed by slit-lamp biomicroscopy. AS-OCT exhibits reflective bands in the corneal stroma that correspond to the area of radial keratoneuritis (white arrows); B: After AK treatment, radial keratoneuritis disappeared in slit-lamp biomicroscopy, and reflective bands in the corneal stroma disappeared in AS-OCT.

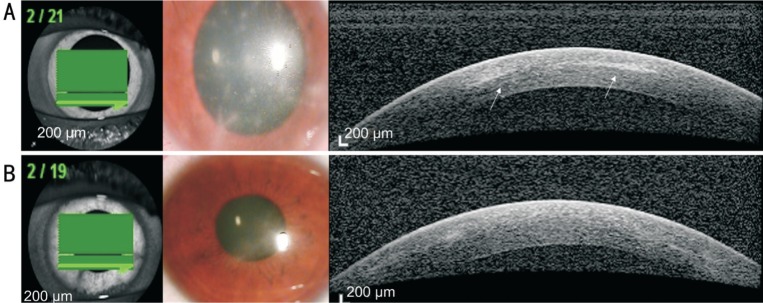

Figure 2. AK case 2.

A: Radial keratoneuritis observed by slit-lamp biomicroscopy. AS-OCT exhibits reflective bands in the corneal stroma that correspond to the area of radial keratoneuritis (white arrows); B: After AK treatment, radial keratoneuritis disappeared in slit-lamp biomicroscopy, and reflective bands in the corneal stroma disappeared in AS-OCT.

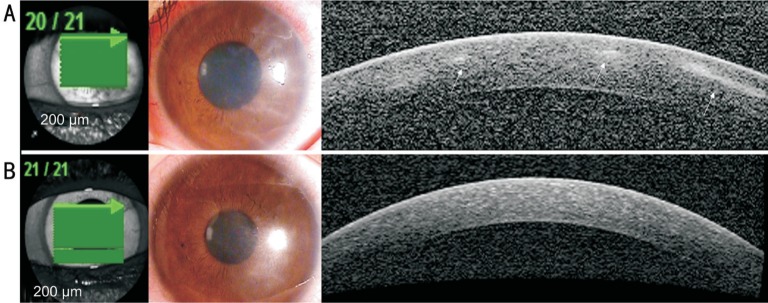

Figure 3. AK case 3.

A: Radial keratoneuritis observed by slit-lamp biomicroscopy. AS-OCT exhibits reflective bands in the corneal stroma that correspond to the area of radial keratoneuritis (white arrows); B: After AK treatment, radial keratoneuritis disappeared in slit-lamp biomicroscopy, and reflective bands in the corneal stroma disappeared in AS-OCT.

Herpetic Epithelial Keratitis Patients

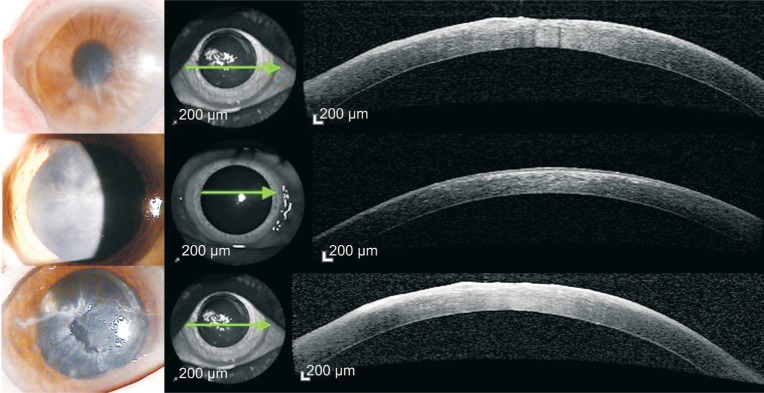

Unlike the AS-OCT results found in AK, highly reflective HEK lesions were observed only in the subepithelial area, not in the stroma (Figure 4). In some patients, we observed corneal epithelial irregularity using slit-lamp biomicroscopy and AS-OCT. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics, treatment process and results of the HEK patients.

Figure 4. HEK cases.

Highly reflective lesion of HEK were observed only at subepithelial area but not at stroma. In some patients, corneal epithelial irregularity was also observed in both slit-lamp biomicroscopy and AS-OCT.

Table 2. Characteristics, clinical ocular histories and treatments of HEK patients.

| Case | Sex/age | Laterality | Risk factor | Slit lamp exam | Treatment | Outcome |

| 1 | M/42 | OD | Ankylosing spondylitis oral steroid treatment | Dendritic ulcer, subepithelial infiltration, conjunctival injection | Topical acyclovir ointment | Good |

| 2 | M/83 | OD | Old age DM HTN |

Dendritic ulcer, subepithelial infiltration with surface irregularity, conjunctival injection | Topical acyclovir ointment | Subepithelial opacity |

| 3 | M/70 | OD | HTN | Geographic ulcer, subepithelial infiltration with surface irregularity, conjunctival injection | Topical acyclovir ointment, artificial tear | Subepithelial opacity with surface irregularity |

DM: Diabetes mellitus; HTN: Hypertension; HEK: Herpetic epithelial keratitis.

DISCUSSION

Solely using slit-lamp biomicroscopy examination to clinically diagnose AK is limited, especially at the early phase of the disease. Among other anterior segment features, radial keratoneuritis is considered a characteristic sign of early stage AK and it can easily be confused with the dendritic lesions or subepithelial infiltration seen in HEK. AK is known to resemble HEK and is often misdiagnosed and treated as HEK[4]. More than 50% of AK cases are misdiagnosed as HEK at initial diagnosis[5], rendering it impossible to properly treat AK early. Although an AK diagnosis can be confirmed by staining, corneal biopsy, or tissue culture[4], these procedure require a lot of time and resources. Additionally, if AK is misdiagnosed as and treated for herpetic keratitis, the toxicity of HEK viral treatments can cause the disease to progress faster than normal while awaiting the test results. For this reason, it is important to distinguish AK from HEK early in the disease onset.

The recent development of AS-OCT enables the visualization of microscopic corneal structures. Yamazaki et al[3] reported that AS-OCT provides novel and detailed visual information of radial keratoneuritis in patients with early-stage AK[3]. However, to date, there have been no reports comparing AS-OCT findings in AK and HEK patients.

Consistent with the findings from the study by Yamazaki et al[3], we observed highly reflective bands in the corneal stroma that corresponded to the area of radial keratoneuritis and these bands disappeared as the radial keratoneuritis resolved after proper AK treatment in all of our patients. Corneal nerve bundles are known to enter the cornea at the periphery and move towards the center, below the anterior third of the stroma[12]. In our study, reflective bands in the corneal stroma also appeared at the anterior third of the stroma, which is consistent with the corneal nerve passage[12]. However, in the current study, it was impossible to identify AK cysts or trophozoites using AS-OCT because of the limited power resolution of the device, meaning that currently, AS-OCT cannot replace tissue culture. In addition, in-vivo confocal microscopy enables to identify AK cysts or trophozoites by its higher resolution compared to the AS-OCT, but AS-OCT has its strength by allowing an overall analysis of the ocular surface due to larger visualization windows[13]–[14]. We believe that if the AS-OCT resolution increases enough to distinguish AK cysts and trophozoites, then tissue culturing could be replaced by AS-OCT. Until then, additional in-vivo confocal microscopy examination along with AS-OCT may be a way to improve the diagnosis rate besides tissue culture.

Unlike AK cases, highly reflective lesions were only observed in the subepithelial area in HEK patients and these lesions remained after the treatment. Although some cases report that HEK initially presents as keratoneuritis, most herpetic keratitis involves the corneal epithelium in the early stage of the disease (e.g. corneal vesicles and dendritic ulcers)[15]–[17]. To differentiate AK from HEK early in the disease, it is important to confirm if the corneal lesion involves the corneal epithelium or stroma. AS-OCT is known to be able to identify disease boundaries in more detail than slit-lamp biomicroscopy even in the presence of corneal opacity, as in this study[18]. Similarly in our study, AS-OCT appears to be more helpful in analyzing detailed lesion depth than slit lamp biomicroscopy in diseases such as AK or HEK that accompanies corneal opacity.

Reflective bands in the corneal stroma that present with radial keratoneuritis, which can be seen using AS-OCT, can be useful to distinguish AK from herpetic keratitis. However, because keratoneuritis is also a characteristic of other diseases than AK, further information, such as a detailed medical history about contact lens use, severe ocular pain, and other symptoms of AK, are necessary for an AK diagnosis. Because this study only included a small number of patients, future studies with a larger number of AK patients are necessary.

Acknowledgments

Authors' contributions: Kim SJ and Park YM were responsible for obtaining consent, acquiring the data and drafting the manuscript. Yoo JM, Park JM, Seo SW and Chung IY participated in patient care and helped establish the final clinical diagnosis. Lee JS and Kim SJ critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Foundation: Supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (No.NRF-2015R1C1A1A02037702).

Conflicts of Interest: Park YM, None; Lee JS, None; Yoo JM, None; Park JM, None; Seo SW, None; Chung IY, None; Kim SJ, None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown AC, Ross J, Jones DB, Collier SA, Ayers TL, Hoekstra RM, Backensen B, Roy SL, Beach MJ, Yoder JS, Acanthamoeba Keratitis Investigation Team Risk factors for acanthamoeba keratitis-a multistate case-control study, 2008-2011. Eye Contact Lens. 2017 doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee MH, Abell RG, Mitra B, Ferdinands M, Vajpayee RB. Risk factors, demographics and clinical profile of acanthamoeba keratitis in Melbourne: an 18-year retrospective study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;102(5):687–691. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamazaki N, Kobayashi A, Yokogawa H, Ishibashi Y, Oikawa Y, Tokoro M, Sugiyama K. In vivo imaging of radial keratoneuritis in patients with Acanthamoeba keratitis by anterior-segment optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2153–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johns KJ, O'Day DM, Head WS, Neff RJ, Elliott JH. Herpes simplex masquerade syndrome: acanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6(1):207–212. doi: 10.3109/02713688709020092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werkmeister RM, Sapeta S, Schmidl D, Garhöfer G, Schmidinger G, Aranha Dos Santos V, Aschinger GC, Baumgartner I, Pircher N, Schwarzhans F, Pantalon A, Dua H, Schmetterer L. Ultrahigh-resolution OCT imaging of the human cornea. Biomed Opt Express. 2017;8(2):1221–1239. doi: 10.1364/BOE.8.001221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izatt JA, Hee MR, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Huang D, Schuman JS, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG. Micrometer-scale resolution imaging of the anterior eye in vivo with optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112(12):1584–1589. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090240090031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li P, An L, Reif R, Shen TT, Johnstone M, Wang RK. In vivo microstructural and microvascular imaging of the human corneo-scleral limbus using optical coherence tomography. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2(11):3109–3118. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.003109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuno Y, Madjarova VD, Makita S, Akiba M, Morosawa A, Chong C, Sakai T, Chan KP, Itoh M, Yatagai T. Three-dimensional and high-speed swept-source optical coherence tomography for in vivo investigation of human anterior eye segments. Opt Express. 2005;13(26):10652–10664. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.010652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gora M, Karnowski K, Szkulmowski M, Kaluzny BJ, Huber R, Kowalczyk A, Wojtkowski M. Ultra high-speed swept source OCT imaging of the anterior segment of human eye at 200 kHz with adjustable imaging range. Opt Express. 2009;17(17):14880–14894. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.014880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grulkowski I, Liu JJ, Baumann B, Potsaid B, Lu C, Fujimoto JG. Imaging limbal and scleral vasculature using Swept Source Optical Coherence Tomography. Photonics Lett Pol. 2011;3(4):132–134. doi: 10.4302/plp.2011.4.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruggeri M, Uhlhorn SR, De Freitas C, Ho A, Manns F, Parel JM. Imaging and full-length biometry of the eye during accommodation using spectral domain OCT with an optical switch. Biomed Opt Express. 2012;3(7):1506–1520. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.001506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller LJ, Marfurt CF, Kruse F, Tervo TM. Corneal nerves: structure, contents and function. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76(5):521–522. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tahiri Joutei Hassani R, Liang H, El Sanharawi M, Brasnu E, Kallel S, Labbé A, Baudouin C. En-face optical coherence tomography as a novel tool for exploring the ocular surface: a pilot comparative study to conventional B-scans and in vivo confocal microscopy. Ocul Surf. 2014;12(4):285–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrovic A, Hashemi K, Blaser F, Wild W, Kymionis G. Characteristics of linear interstitial keratitis by in vivo confocal microscopy and anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Cornea. 2018;37(6):785–788. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darougar S, Wishart MS, Viswalingam ND. Epidemiological and clinical features of primary herpes simplex virus ocular infection. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69(1):2–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.69.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin A, Lietman T, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Update on the management of infectious keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1678–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azher TN, Yin XT, Tajfirouz D, Huang AJ, Stuart PM. Herpes simplex keratitis: challenges in diagnosis and clinical management. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:185–191. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S80475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirano K, Ito Y, Suzuki T, Kojima T, Kachi S, Miyake Y. Optical coherence tomography for the noninvasive evaluation of the cornea. Cornea. 2001;20(3):281–289. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]