Abstract

Purpose

After modern acetabular osteotomies were introduced, hip shelf operations have become much less commonly used. The aims of this study were to assess the short-term and long-term outcome of a modified Spitzy shelf procedure and to compare the results with those of periacetabular osteotomy (PAO).

Methods

In all, 44 patients (55 hips) with developmental dysplasia of the hip and residual dysplasia had a modified Spitzy shelf operation. Mean age at surgery was 13.2 years (8 to 22). Indication for surgery was a centre-edge angle < 20° with or without hip pain. Outcome was evaluated using duration of painless period and survival analysis with conversion to total hip arthroplasty (THA) as endpoints.

Results

Preoperative hip pain was present in 46% of the hips and was more common in patients ≥ 12 years at surgery (p < 0.001). One year postoperatively, 93% of the hips were painless. Analysis of pain in hips with more than ten years follow-up showed a mean postoperative painless period of 20.0 years (0 to 49). In all, 44 hips (80%) had undergone THA at a mean patient age of 50.5 years (37 to 63). Mean survival of the shelf procedure (time from operation to THA) was 39.3 years (21 to 55).

Conclusions

The Spitzy operation had good short and long-term effects on hip pain and a 30-year survival (no THA) of 72% of the hips. These results compare favourably with those of PAO and indicate that there is still a place for the shelf procedure in older children and young adults.

Keywords: developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), hip shelf operation, Spitzy procedure, long-term outcome

Introduction

Developmental dislocation and dysplasia of the hip (DDH) often develops into secondary osteoarthritis (OA) if appropriate measures are not undertaken.1,2 The shelf operation is a procedure aimed at correcting residual acetabular dysplasia and subluxation. The intention is, by extending the dysplastic acetabular roof, to improve hip stability and postpone the occurrence of OA. Another intention is to eliminate or reduce hip pain. Multiple surgical techniques of the shelf operation have been described. In our hospital a modification of the technique described by Spitzy3 was the preferred method for joint-preserving surgery for several decades. We recently published the long-term outcome of the Spitzy procedure,4 but the results according to age groups were not specified.

During the last decades more demanding and technically complicated procedures like periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) have gained popularity for joint-preserving purposes5 and the long-term results with up to 30 years follow-up have recently been published.6,7 Whether the survival rates with total hip arthroplasty (THA) as the endpoint after pelvic osteotomies are superior to those of the shelf procedure have so far not been analyzed. In the present study the long-term results of patients older than 12 years at the time of Spitzy shelf procedure were used for comparison with those having undergone PAO.

The aims of this study were to assess the short- and long-term outcomes of the modified Spitzy shelf procedure and to evaluate whether there is still a place for the shelf operation in residual hip dysplasia in older children and young adults.

Patients and methods

The patients for this retrospective study were recruited from a search of surgical procedures at Sophies Minde Orthopaedic Hospital (now Orthopaedic Department, Oslo University Hospital) for the period between 1954 and 1976. A modified Spitzy shelf operation had been performed in 56 patients. Since there is an increased risk of graft resorption in young children,8 12 children under eight years were omitted from this study. Thus, 44 patients (55 hips) were included. There were 39 female (49 hips) and five male (6 hips) patients. The mean age at operation was 13.2 years (8 to 22). In all, 11 patients had bilateral procedures, usually a few weeks apart. Indications for surgery included a diagnosis of DDH and residual hip dysplasia or subluxation, with or without hip pain. Preoperatively, all patients had acetabular dysplasia, defined as a centre-edge (CE) angle1 < 20°.

Surgical technique

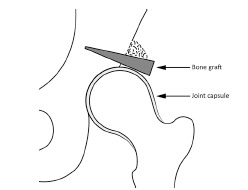

A technique modified from Spitzy’s was employed.3 A Smith-Petersen anterior skin incision was used. The outer surface of the iliac bone was exposed subperiosteally down to the lateral joint capsule and the reflected head of the rectus femoris tendon was divided. The lateral capsule was usually thick and was made somewhat thinner by partial resection. A broad osteotome was used to make a slot for the shelf in the iliac bone, just proximal to the acetabular labrum and in a medial and slightly proximal direction (Fig. 1). A trapezoid cortico-cancellous bone graft was obtained from the anterolateral iliac crest. The bone graft (approximately 4 cm and 2 cm long, 4 cm deep and 3 mm to 5 mm thick) was impacted into the slot with the slightly concave cortical side downwards. The aim was to place the graft as near the joint capsule as possible. Cancellous bone chips from the iliac wing were packed into the triangular space between the shelf and lateral iliac surface. The postoperative regime was skin traction for ten weeks followed by partial weight-bearing with crutches for four weeks. Full weight-bearing walking was allowed approximately three months postoperatively.

Fig. 1.

Schematic drawing of the hip joint, showing the solid bone graft inserted in the slot just above the lateral joint capsule and cancellous bone chips between the solid graft and the lateral iliac surface.

Follow-up evaluation

Information on pre- and postoperative pain was obtained from the case records. This information was missing in eight patients (nine hips) because their case records were not available. Most patients were followed by routine clinical and radiographic examinations for many years. However, some patients had only a few years follow-up because they had no complaints about their hips.

Preoperative radiographs were missing in 18 patients (21 hips). For the remaining 34 hips with available radiographs, avascular necrosis of the femoral head (AVN) was assessed according to the classification of Kalamchi and MacEwen9 but only Groups II to IV were regarded as true AVN. Femoral head coverage pre- and postoperatively was assessed by the CE angle.

Long-term follow-up included information on THA, provided from The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register which started registration of THA in Norway in 1988. The data included whether or not the 55 hips had undergone THA and the year and patient age at the time of THA.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software, version 23 (IBM, Armonk, New York) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables were analyzed with the t-test for independent samples and categorical variables were assessed by Pearson’s chi-squared test. Potential factors associated with a painless period postoperatively were first assessed by univariable analysis. Variables with p-value < 0.05 were tested by multivariable linear regression. The Kaplan-Meier product-limit method was used to estimate the survival of the Spitzy procedure, with recurrence of hip pain and conversion to THA as endpoints. All tests were two-sided. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Since it was relevant to compare patients ≥ 12 years with younger patients, the associations between the age groups and preoperative parameters were assessed. The mean age at surgery was 10.0 years in the younger and 16.1 years in the older group. Preoperative hip pain was present in 46% of the hips. The older group had a higher frequency of preoperative pain (75%) than the group < 12 years (14%) (p < 0.001), whereas there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of gender, AVN or preoperative CE angle. The mean duration of preoperative pain was 2.4 years (1 to 8). One year postoperatively all except three hips were painless (93%). The three painful hips belonged to the older age group; they had had preoperative pain and were also painful during further follow-up.

The mean preoperative CE angle was 4.6° (-20° to 17°). One year postoperatively the mean CE angle was 31.4° (4° to 51°), 28.9° in younger patients and 35.6° in older. The difference between the age groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.116). The shelf had been totally or partially resorbed in three hips (age at surgery eight to 11 years). Postoperative wound infection occurred in four hips (three in the older age group and one in the younger), leading to early OA in three patients, whereas one patient recovered after treatment with antibiotics and had a good long-term outcome. One patient experienced peroneal paresis postoperatively, but the paresis was transitory with almost full recovery.

Long-term results

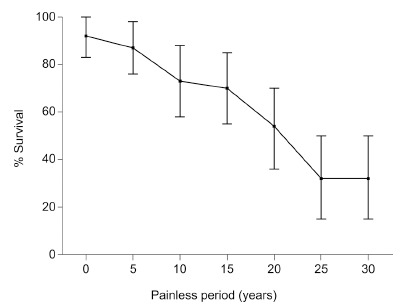

Eight patients (nine hips) had a follow-up of less than ten years. They had no hip pain, but were excluded from the long-term analysis of pain. Long-term pain analysis was performed in the remaining hips. The mean painless period (time from operation to start of pain) was 20.0 years (0 to 49). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with duration of painless period as ‘survival’, is shown in Figure 2. The survival curve showed a steadily decreasing survival from 93% one year postoperatively to 73% at ten years, 54% at 20 years and 32% at 30 years.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot with 95% confidence intervals, with duration of painless period postoperatively as endpoint in 37 hips with follow-up more than ten years.

Association between duration of postoperative painless period and preoperative variables are shown in Table 1. In univariable analysis painless period was significantly longer in hips with a preoperative CE angle ≥ 10° than in those with CE angle < 10° and longer in hips with no AVN at the time of shelf operation. There were no significant associations between painless period and age at surgery or preoperative hip pain. When the variables with a p-value < 0.05 were analyzed with multivariable linear regression, there were no independently significant predictors for longer painless period.

Table 1.

Association between painless period postoperatively and preoperative variables in hips with follow-up ten or more years

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable linear regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Painless period (yrs) | |||||

| Mean | sd | p-value* | p-value | ||

| Age at Spitzy | < 12 yrs | 19.9 | 11.9 | 0.947 | |

| ≥ 12 yrs | 20.2 | 14.9 | |||

| Preoperative centre-edge angle | < 10° | 14.3 | 7.3 | 0.033 | 0.069 |

| 10° to 17° | 24.3 | 16.8 | |||

| Preoperative hip pain | No pain | 22.1 | 12.0 | 0.311 | |

| Hip pain | 17.6 | 14.9 | |||

| Avascular necrosis (AVN) | No AVN | 21.9 | 13.5 | 0.032 | 0.139 |

| AVN | 11.3 | 7.4 | |||

univariable analysis was performed with Independent samples t-test

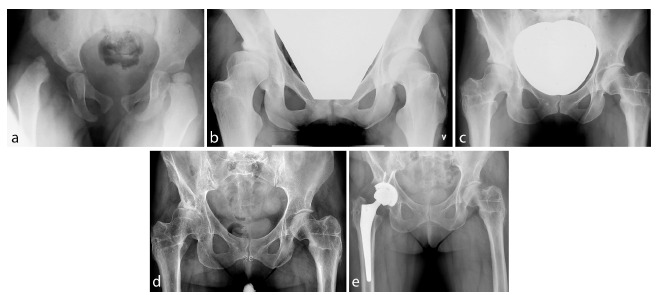

During the follow-up period, 44 of the 55 hips (80%) had undergone THA (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference in the proportion with THA between the age groups (p = 0.224). The mean patient age at THA was 50.5 years (37 to 63). Mean age at THA was 49.3 years in patients under 12 years at Spitzy and 51.4 years in those ≥ 12 years (p = 0.357).

Fig. 3.

Radiographs of a girl with residual dysplasia and Spitzy operation: (a) primary radiograph at an age of 1.8 years shows dislocation of the right hip; (b) radiograph at the age of 16.6 years showing residual dysplasia and subluxation of the right hip. Spitzy operation was performed one year later; (c) radiograph at the age of 33 years, 16 years after Spitzy procedure, showing good femoral head coverage and no osteoarthritis. Bilateral varus and derotating femoral osteotomies had been performed one year prior to Spitzy procedure; (d) radiograph at an age of 58 years, 40 years after Spitzy procedure, showing osteoarthritis of the right hip; (e) radiograph at an age of 58 years, three months after total hip arthroplasty.

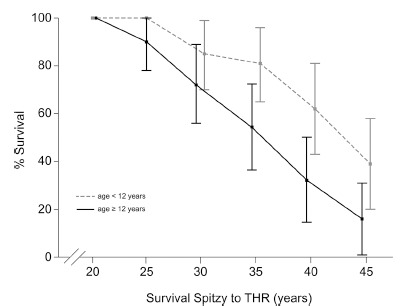

The mean survival of the Spitzy procedure (time from operation to THA) was 39.3 years (21 to 55). Age at surgery < 12 years was the only significant predictor for a longer survival (Table 2). Mean survival was 42.2 years in children < 12 years and 36.7 years in older patients (p = 0.015). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with conversion to THA as endpoint for both age groups are shown in Table 3 and Figure 4. Survival was 100% for both groups up to 20 years postoperatively. Thereafter, survival was better in patients < 12 years. In those ≥ 12 years, survival decreased from 100% at 20 years to 72% at 30 years and 32% at 40 years postoperatively.

Table 2.

Association between survival of Spitzy operation (time from surgery to total hip arthroplasty) and preoperative variables

| Variables | Survival (yrs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | sd | p-value* | ||

| Age at Spitzy | < 12 yrs | 42.2 | 8.0 | 0.015 |

| ≥ 12 yrs | 36.7 | 8.3 | ||

| Preoperative centre-edge angle | < 10° | 38.3 | 9.7 | 0.111 |

| 10° to 17° | 43.3 | 7.6 | ||

| Preoperative hip pain | No pain | 40.9 | 9.0 | 0.087 |

| Hip pain | 36.1 | 8.7 | ||

| Avascular necrosis (AVN) | No AVN | 40.3 | 8.9 | 0.442 |

| AVN | 38.0 | 9.7 | ||

| Side | Unilateral | 38.7 | 8.5 | 0.536 |

| Bilateral | 40.1 | 8.7 | ||

data were analyzed with Independent samples t-test

Table 3.

Survival of Spitzy shelf operation with conversion to total hip arthroplasty as endpoint according to age groups < 12 years and ≥ 12 years

| Follow-up time (yrs) | Hip survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 12 yrs at surgery | ≥ 12 yrs at surgery | |||

| % | 95% confidence interval | % | 95% confidence interval | |

| 20 | 100 | 100 | ||

| 25 | 100 | 90 | 79 to 100 | |

| 30 | 85 | 71 to 99 | 72 | 55 to 89 |

| 35 | 81 | 66 to 96 | 55 | 37 to 73 |

| 40 | 62 | 43 to 81 | 32 | 14 to 50 |

| 45 | 39 | 20 to 58 | 16 | 1 to 31 |

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival plots with 95% confidence intervals, with conversion to total hip arthroplasty (THA) as the endpoint, in children < 12 years and children ≥ 12 years at Spitzy operation.

The mean time from start of hip pain postoperatively to THA was 18.5 years (2 to 44) in patients with more than ten years follow-up. There was no statistically significant difference between children < 12 years and older patients (mean interval 21.6 years versus 15.9 years; p = 0.194).

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that the Spitzy operation had a good short- and long-term effect on hip pain, and that the procedure had a 30-year survival with conversion to THA as the endpoint, in 72% of the hips in patients aged ≥ 12 years at surgery. Whether the long-term results are better or worse than those of alternative surgical procedures has not previously been evaluated.

The study had several limitations. First, it was retrospective and there was no control group. Second, the number of patients was limited and preoperative radiographs were not available in several patients. Moreover, information about hip pain based on old patient records could imply questionable reliability and long-term data on hip pain was lacking in some of the patients. The strengths of the study were the long follow-up time and that no patients were lost to follow-up regarding the frequency of THA.

One of the main intentions of the shelf procedure is to eliminate or reduce hip pain and avoid pain problems as far as possible during the postoperative years. Preoperative hip pain was present in 46% of the hips and there was a clear trend to increasing pain rate with age at surgery, with 75% painful hips at age ≥ 12 years. This is consistent with previous studies in children and young adults, where approximately 70% of the hips had preoperative pain.10,11 In a study on adults with residual dysplasia, all hips were painful preoperatively.12 Six months after the Spitzy procedure, pain had improved in 90% of the hips, which is consistent with the present finding of 93% painless hips one year postoperatively. With a follow-up of 17 years, Summers et al11 reported pain relief for a mean period of 12 years in hips that had been painful preoperatively. With longer follow-up the mean painless period was 20 years in the present hips. Nishimatsu et al8 published the longest previous follow-up (24 years) after modified Spitzy procedures in children and adults. Using Kaplan-Meier survivorship in patients younger than 25 years at surgery, with poor clinical result as an endpoint, they predicted a survival rate for the shelf operation of 80% at 15 years follow-up, which is in keeping with our study’s 70% painless hips at 15 years of follow-up. However, the studies should not be directly compared because of different outcome measures; hip pain was used in the present study and the Japanese Orthopaedic Association rating scale, where pain represents 40 out of 100 points, was used in the study of Nishumatsu et al.8 It seems clear that the older the patient, the greater the risk of having preoperative hip pain and that pain is relieved in the great majority of hips. Although the pain will eventually recur in most patients, the period of painlessness usually lasts many years. The present patients had pain almost 20 years before they underwent THA, indicating that pain was probably mild or moderate for a long period. If the hips had not undergone the Spitzy procedure, the painful hips would hardly have become better spontaneously and THA might have been necessary earlier.

Preoperative CE angle < 10° was a significant risk factor for shorter painless period postoperatively, whereas there was no significant difference in painless period between patients < 12 years compared with older patients. Summers et al,11 with a mean age at surgery of 14 years, found better pain relief in patients < 20 years than in older patients. This indicates that the Spitzy procedure in hips with residual dysplasia should not be postponed, because the CE angle will usually become lower with time and hip pain is more common in older patients. In patients with especially low CE angle (< 0°), alternative procedures like PAO should be considered.

Besides pain relief, the intention of the shelf procedure is to avoid or postpone the occurrence of OA and the need for THA. To prove this, a control group with residual dysplasia but without a pelvic operation would be necessary, but no such study exists. However, this question could be evaluated in the light of patients who were relatively young at the time of THA. Drobniewski et al13 reported that, in DDH patients under 50 years at THA, the mean age at THA was 38 years, whereas the mean age at THA in our corresponding age group was 44 years. This indicates that the shelf procedure could postpone the age for THA by some years.

In the discussion as to whether or not there is still a place for shelf procedures, long-term studies and comparison with alternative procedures like PAO are required. Only patients ≥ 12 years at surgery should be included, since this is usually the lower age limit for PAO. OA has been reported to be a risk factor for poor survival rate after both shelf procedures and PAO;6,7,12, thus, comparisons should be made according to preoperative OA, as was done in Table 4.6,7,14 This shows Kaplan-Meier survival analyses with conversion to THA in recent long-term studies. With a considerably higher mean age at shelf acetabuloplasty in the study of Hirose et al14 than that of the older group in the present study (34 years versus 16 years), the survival rates in hips with no preoperative OA were remarkably similar, with 100% survival at ten years follow-up, more than 90% at 20 years and about 70% at 30 years. Survival after PAO in hips with no preoperative OA were similar at 18 years follow-up (89% survival),7 and slightly lower after 30 years (60% survival).6 The survival rates after PAO were markedly lower in hips with preoperative OA, with 37% survival after 18 years7 and only 14% at 30 years.6 This shows that correction of residual acetabular dysplasia in patients with DDH should be performed without unnecessary delay, i.e. before OA occurs.

Table 4.

Hip survival in the present study (age at surgery ≥ 12 years) and in other recent studies, assessed as percentage of hips that have not undergone total hip arthroplasty according to duration of follow-up

| Study | Treatment | Age (yrs), mean (range) | OA | Follow-up (yrs) | Hip survival (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hirose et al 201114 | Shelf acetabuloplasty | 34 (17 to 54) | No | 10 | 100 |

| Present study | Spitzy shelf | 16 (12 to 22) | No | 10 | 100 |

| Hirose et al 201114 | Shelf acetabuloplasty | 34 | No | 20 | 93 |

| Present study | Spitzy shelf | 16 | No | 20 | 100 |

| Wells et al 20177 | PAO | 27 (10 to 45) | No | 18 | 89 |

| Wells et al 20177 | PAO | 27 | OA | 18 | 37 |

| Hirose et al 201114 | Shelf acetabuloplasty | 34 | No | 32 | 71 |

| Present study | Spitzy shelf | 16 | No | 30 | 72 |

| Lerch et al 20176 | PAO | 29 (13 to 56) | No | 30 | 60 |

| Lerch et al 20176 | PAO | 29 | OA | 30 | 14 |

Age, age at surgery; OA, preoperative osteoarthritis; No, no osteoarthritis; PAO, periacetabular osteotomy

Based on the results of the present study, it seems fair to conclude that there is still a place for hip shelf operation in patients with residual hip dysplasia, which is in accordance with several previous studies.8,10–12 The operation should rarely be done in patients younger than eight years because of increased risk of graft resorption. Furthermore, the procedure should probably be restricted to patients without severe degrees of OA, which worsens the prognosis.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the photographer Øystein H. Horgmo for help with the illustrations.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding statement

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

OA Licence Text

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the hospital’s privacy and data protection officer (no. 2014/9274).

Informed Consent: Not required for this type of work.

ICMJE Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflict of interest or funding to disclose.

References

- 1.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint. Acta Chir Scand 1939;83:1–135. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;213:20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spitzy H. Künstliche Pfannendachbildung. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 1924;43:284–94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm AG, Reikerås O, Terjesen T. Long-term results of a modified Spitzy shelf operation for residual hip dysplasia and subluxation. A fifty year follow-up study of fifty six children and young adults. Int Orthop 2017;41:415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;232:26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lerch TD, Steppacher SD, Liechti EF, Tannast M, Siebenrock KA. One-third of hips after periacetabular osteotomy survive 30 years with good clinical results, no progression of arthritis, or conversion to THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017;475:1154–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells J, Millis M, Kim YJ, et al. . Survivorship of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy: what factors are associated with long-term failure? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017;475:396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishimatsu H, Iida H, Kawanabe K, Tamura J, Nakamura T. The modified Spitzy shelf operation for patients with dysplasia of the hip. A 24-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2002;84-B:647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalamchi A, MacEwen GD. Avascular necrosis following treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1980;62-A:876–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Love BR, Stevens PM, Williams PF. A long-term review of shelf arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1980;62-B:321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Summers BN, Turner A, Wynn-Jones CH. The shelf operation in the management of late presentation of congenital hip dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1988;70-B:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fawzy E, Mandellos G, De Steiger R, et al. . Is there a place for shelf acetabuloplasty in the management of adult acetabular dysplasia? A survivorship study. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2005;87-B:1197–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drobniewski M, Synder M, Kozłowski P, Grzegorzewski A, Głowacka A. Long-term results of uncemented hip arthroplasty for dysplastic coxarthrosis. Wiad Lek 2005;58:4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirose S, Otsuka H, Morishima T, Sato K. Long-term outcomes of shelf acetabuloplasty for developmental dysplasia of the hip in adults: a minimum 20-year follow-up study. J Orthop Sci 2011;16:698–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]