Abstract

Cancer, and particularly colon cancer, is associated with an increasing number of cases resistant to chemotherapy. One approach to overcome this, and to improve the prognosis and outcome of patients, is the use of adjuvant therapy alongside the standard chemotherapy regiment. In the present study, the effect of deuterium-depleted water (DDW) as a potential modulator of adjuvant therapy on DLD-1 colorectal cancer models was assessed. A number of functionality assays were performed, including MTT, apoptosis and autophagy, and mitochondrial activity and senescence assays, in addition to assessing the capacity to modify the pattern of released miRNA via microarray technology. No significant effect on cell viability was identified, but an increase in mitochondrial activity and a weak pro-apoptotic effect were observed in the treated DLD-1 cells cultured in DDW-prepared medium compared with those grown in standard conditions (SC). Furthermore, the findings revealed the capacity of DDW medium to promote senescence to a higher degree compared with SC. The exosome-released miRNA pattern was significantly modified for the cells maintained in DDW compared with those maintained in SC. These findings suggest that DDW may serve as an adjuvant treatment; however, a better understanding of the underlying molecular mechanism of action will be useful for developing novel and efficient therapeutic strategies, in which the transcriptomic pattern serves an important role.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, adjuvant therapy, cell death, senescence, exosomal miRNAs pattern

Introduction

Cancer represents the second greatest cause of mortality in developing countries, for which the chemotherapy is the most effective treatment. However, its efficiency is limited by the ability of cancer cells to acquire resistance to the treatment regiment, which accounts for ~90% of failures (1,2). Drug resistance is currently considered the most notable challenge in cancer therapy. This resistance may be determined by genetic and epigenetic mechanisms as a response to different biochemical processes, and also by changes in drug levels during the course of treatment (3). One potential approach to overcome this, while improving the prognostic and outcome of patients, is the use of adjuvant therapy in addition to the standard chemotherapy regimen.

Deuterium is a natural and stable isotope of hydrogen, which is found in the Earth's atmosphere at a concentration of 144-155 ppm (4). An increase in deuterium concentration leads to the formation of heavy water, which has different physical and chemical proprieties compared with normal water (5). This heavy water has detrimental effects on living organisms; ingestion can cause sterility, while high concentrations of deuterium can result in mortality via modification of the mitotic cycle and cell membrane function (6). Therefore it is presumable that deuterium-depleted water (DDW) may have beneficial effects by interfering cell metabolism and the overall function of living cells (7,8).

A number of previous studies have explored the effects of deuterium-depletion on cell proliferation, on both in vitro and in vivo cancer models. A study on the A549 lung carcinoma cell line demonstrated that deuterium-depleted water leads to a reduction in cell proliferation between 10 and 72 h of exposure, with a peak of cellular structural changes occurring at 72 h of exposure (9). This effect of tumor inhibition has also been confirmed on orthotopic models of BALB/c mice (9) and human patients with lung cancer (10). This tumor regression may be correlated with a reduction in the expression levels of several oncogenes, such as KRAS, B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) or c-Myc, as previously reported (10), suggesting apoptosis as the potential mechanism of tumor inhibition by DDW in cell lines that overexpress Bcl2, a process also observed in pancreatic cell lines (11). Besides the pro-apoptotic effect, DDW seems to have an inhibitory effect on migration and invasion by downregulating proliferating cell nuclear antigen and matrix metalloproteinase 9 previous in nasopharyngeal cell carcinoma (12). Additionally, this study indicated an induction of NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 expression, which is a protein that regulates different cell cycle factors, such as cyclin D1, p21 and c-Myc.

Free or exosome-released microRNA (miRNA or miR) patterns may be used as valuable biomarkers for defining physiological and pathological processes of cell subpopulation (13–16). Previous studies have emphasized the important role of the manipulation of miRNA profiles (17,18), which is considered as a novel approach for colon cancer prevention, chemotherapy and avoidance of drug resistance related mechanisms (19,20). Therefore, in the present study the impact of DDW on the capacity to alter released miRNA patterns was evaluated in colorectal cancer cells, along with a set of preliminary functionality tests in order to evaluate the utility of DDW as an adjuvant in colorectal cancer therapy.

Materials and methods

Materials and cell lines

Powdered RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with glutamine, liquid RPMI-1640, fetal bovine serum (FBS), PBS, penicillin-streptomycin 100X and trypsin-EDTA solutions were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and MTT were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). DLD-1 (colorectal carcinoma) cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Oxaliplatin was obtained from Fresenius Kabi Asia-Pacific, Ltd. (Wanchai, Hong Kong) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was obtained from Ebewe Pharma GmbH (Unterach, Austria). DDW was provided by Qlarivia; Mecro System SRL (Bucharest, Romania) with 25±5 ppm D/(D+H), obtained by vacuum distillation.

MTT cell viability assay

For assessing the cytotoxicity of selected chemotherapeutic agents, DLD-1 cell line was maintained for 64 passages in standard conditions (SC) and for 66 passages in medium with low concentration of deuterium (DDW). A total of 10,000 DLD-1 colorectal cancer cells/well were plated in 96-well plates in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine and 1X penicillin-streptomycin for SC cell culture, and 10,000 DLD-1 colorectal cancer cells/well were plated in 96-well plates in filter-sterilized RMPI-1640 medium powder (supplemented with glutamine) prepared with DDW supplemented with 10% FBS and 1X penicillin-streptomycin for DDW cell culture. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h and the cytostatic agents were subsequently applied separately in triplicate at concentrations of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10 and 12 µM for 5-FU, and 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 20 µM for oxaliplatin. At 24, 48 and 72 h following treatment, the medium was discarded, and the adherent cells were treated with 150 µl MTT solution (1 mg/ml). Following 1 h incubation at 37°C, the formazan crystals were solubilized with 100 µl DMSO and the viability of the cells was assessed at 492 nm wavelength using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Computation of inhibition constant 50 (IC50)

The response curves to cytostatic drugs were generated from the MTT data and computed using MasterPlex Readerfit software (trial version 2.0.0.73; MiraiBio Group of Hitachi Solutions America, Ltd., San Francisco, CA, USA), and IC50 values were determined based on the response curves.

Total RNA extraction from exosome-released medium

The exosomes released from cells cultured in SC and DDW cell culture medium without 5-FU or oxaliplatin were precipitated from 4 ml cell culture media using Total Exosome Isolation Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently the precipitated exosomal fraction was used for extraction of total RNA using a Plasma/Serum Circulating and Exosomal RNA Purification kit (Slurry Format; Norgen Biotek Corp., Thorold, ON, Canada) for the cells maintained in SC and those maintained in DDW-prepared medium.

Microarray evaluation, data analysis and identification of differentially expressed miRNAs released in cell culture medium

The microarray experiment was conducted using the Human miRNA Microarray Kit (release 21.0; format, 8×60K slides; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The miRNA Labeling and Hybridization kit was used according to the manufacturer's protocol, together with the Complete Labeling and Hybridization kit (both Agilent Technologies, Inc.) using 100 ng total RNA from 2 samples of cells grown in SC and 2 samples cultivated in DDW-prepared medium, labeled with pCp-Cy3 and purified with MicroBioSpin 6 Columns (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Slides were hybridized for 20 h at 54°C, washed with Agilent washing solution 1 and 2, and scanned using the Agilent Microarray Scanner G2565BA (Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Samples were grouped according to duplicates, and preliminary data analysis was performed using Feature Extraction Software (version 10.7; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Differential analysis of miRNA expression was performed using GeneSpring GX version 12.6.1 software (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), using P≤0.05 and −1.5≤ fold change (FC) ≥1.5. For the integration of the altered miRNA patterns as an effect of DDW exposure in biological mechanisms, the NCBI Database was used (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA®; Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) is a valuable bioinformatics tool that was used for the identification of the most relevant altered pathways based on the identified altered transcriptomic profile in the cells cultured in DDW conditions compared with those in SC conditions. It contains a database with >302 metabolic networks and 360 signaling pathways used for the altered miRNA signature, the miRNAs were scored on the significance of their overlap with these networks and pathways.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data analysis for colorectal cancer

The extent to which the expression of microRNAs is prone to modification as a result of treatment was subsequently evaluated. TCGA was used and differential analysis was performed using the miRNA expression data for patients with colorectal cancer, which was downloaded from the University of California Santa Cruz genome browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu). The data for colon adenocarcinoma, which consisted of 433 tumor samples and 8 normal samples, was combined with expression data for rectum adenocarcinoma, which consisted of 162 tumor tissues and 3 normal tissues, to obtain the colorectal cancer cohort. Using GeneSpring GX software (version 14.9; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), differential expression analysis was performed, and by applying filters of using P≤0.05 and −1.5≤FC≥1.5, a list containing the most upregulated and downregulated microRNAs between tumors and normal tissues was generated, as described previously (21–23).

Generation of Venn diagram

Using the obtained TCGA miRNA data the Venn diagram was generated using the online tool Venny version 2.1 (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/) and indicated the commonly or inversely regulated transcripts in DDW-treated cells.

Assessing apoptosis via fluorescence microscopy tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester (TMRE)/Hoechst double staining. Evaluation of apoptosis was performed using a Multi-Parameter Apoptosis kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells from the SC and DDW groups were analyzed at UV wavelength (560/595 nm) for Hoechst and TMRE staining using a Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay kit (cat no. 701310; Cayman Chemical Company) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and Olympus IX71 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at a magnification of ×20. Hoechst is a cell permeable dye for the nuclei, independent of the cell membrane status, whereas TMRE dye allows the evaluation of mitochondrial function by assessing the membrane potential, which is lost in cells entering apoptosis (24–26). Cell apoptosis was evaluated at 48 h of exposure to 5-FU and oxaliplatin at the IC50 concentration.

Evaluation of senescence

For senescence evaluation of cells cultured in SC and DDW conditions, the Senescence Detection kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. The kit detects β-galactosidase, which is overexpressed in senescent cells (27). Cells were visualized in both cases using an Olympus IX71 microscope (magnification, ×20).

Results

Evaluation of the altered miRNA expression profiles

Differential miRNA expression profiles in the case of colorectal cells maintained in DDW vs. those maintained in SC were evaluated using miRNA labeling and hybridization, and microarray evaluation. During data analysis using the specialized GeneSpring GX software, a cut-off value of −1.5≤FC≥1.5 and P<0.05 were considered, and were able to identify several transcripts with altered expression levels. In total, 105 transcripts with modified expression levels were identified, from which 46 were upregulated and 59 downregulated (Table I).

Table I.

The altered miRNA pattern for the case of deuterium-depleted water-maintained cells vs. those maintained in standard conditions.

| Systematic name | Fold change | Corrected P-value |

|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-4261 | −22.7086 | 2.16E-04 |

| hsa-miR-3912-5p | −22.0231 | 2.16E-04 |

| hsa-miR-4711-3p | −18.467 | 2.16E-04 |

| hsa-miR-362-5p | −16.8774 | 0.001651 |

| hsa-miR-3923 | −16.6997 | 0.001231 |

| hsa-miR-664a-3p | −16.3672 | 0.001651 |

| hsa-miR-34b-5p | −16.0323 | 0.008314 |

| hsa-miR-136-5p | −14.7967 | 0.002438 |

| hsa-miR-5007-5p | −13.0422 | 2.16E-04 |

| hsa-miR-4317 | −13.0337 | 6.44E-04 |

| hsa-miR-193b-5p | −12.6629 | 6.44E-04 |

| hsa-miR-4700-5p | −12.6546 | 0.021906 |

| hsa-miR-125a-5p | −12.1643 | 0.001253 |

| hsa-miR-936 | −11.01 | 0.014825 |

| hsa-miR-6516-5p | −10.4295 | 0.012692 |

| hsa-miR-4488 | −10.3318 | 0.012692 |

| hsa-miR-545-3p | −9.28502 | 0.013747 |

| hsa-miR-4715-5p | −9.23226 | 0.008749 |

| hsa-miR-4468 | −7.60702 | 3.74E-04 |

| hsa-miR-32-5p | −5.34052 | 0.011851 |

| hsa-miR-6872-3p | −4.00105 | 0.017607 |

| hsa-miR-4291 | −2.81713 | 0.03264 |

| hsa-miR-1260b | −2.52161 | 0.006656 |

| hsa-miR-1233-5p | −2.2066 | 0.022847 |

| hsa-miR-5684 | −2.15719 | 0.013747 |

| hsa-miR-3976 | −2.12003 | 0.042139 |

| hsa-miR-182-5p | −2.11261 | 0.010321 |

| hsa-miR-5100 | −2.11064 | 0.014468 |

| hsa-miR-1260a | −2.08488 | 0.00429 |

| hsa-miR-660-3p | −2.06228 | 0.03624 |

| hsa-miR-3064-5p | −2.03183 | 0.021906 |

| hsa-miR-6717-5p | −2.0278 | 0.017607 |

| hsa-miR-6788-5p | −1.96362 | 0.009607 |

| hsa-miR-7114-5p | −1.95488 | 0.014468 |

| hsa-miR-18b-5p | −1.9179 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-324-5p | −1.8771 | 0.034038 |

| hsa-miR-1273g-3p | −1.87346 | 0.033338 |

| hsa-miR-6131 | −1.8712 | 0.019085 |

| hsa-miR-921 | −1.87005 | 0.037554 |

| hsa-miR-6826-5p | −1.85113 | 0.014468 |

| hsa-miR-7159-5p | −1.83784 | 0.03967 |

| hsa-miR-4753-5p | −1.80366 | 0.014468 |

| hsa-miR-320b | −1.74454 | 0.019579 |

| hsa-miR-126-3p | −1.73136 | 0.045633 |

| hsa-miR-5196-5p | −1.72965 | 0.033735 |

| hsa-miR-6872-5p | −1.65159 | 0.024325 |

| hsa-miR-211-3p | −1.61236 | 0.021906 |

| hsa-miR-6875-5p | −1.60393 | 0.014468 |

| hsa-miR-320e | −1.57832 | 0.012692 |

| hsa-miR-146a-5p | −1.57515 | 0.033735 |

| hsa-miR-23a-3p | −1.57461 | 0.034732 |

| hsa-let-7d-5p | −1.57108 | 0.037564 |

| hsa-miR-6085 | −1.57099 | 0.012896 |

| hsa-miR-23b-3p | −1.55252 | 0.034038 |

| hsa-miR-3907 | −1.53592 | 0.012692 |

| hsa-miR-3650 | −1.52958 | 0.013747 |

| hsa-miR-3689b-3p | −1.52255 | 0.033715 |

| hsa-miR-4286 | −1.52084 | 0.034127 |

| hsa-miR-539-5p | −1.51706 | 0.026802 |

| hsa-miR-6777-3p | 12.35759 | 0.001651 |

| hsa-miR-1247-5p | 10.66176 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-5008-3p | 10.36788 | 0.017607 |

| hsa-miR-6870-3p | 10.21028 | 0.010321 |

| hsa-miR-4508 | 10.0584 | 0.014468 |

| hsa-miR-373-5p | 8.170245 | 0.04109 |

| hsa-miR-6812-3p | 7.939796 | 0.042139 |

| hsa-let-7b-3p | 7.565567 | 0.034732 |

| hsa-miR-326 | 7.435405 | 0.027191 |

| hsa-miR-375 | 3.686158 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-6726-5p | 3.444442 | 0.001231 |

| hsa-miR-3934-5p | 3.160403 | 0.009522 |

| hsa-miR-1236-5p | 2.984447 | 0.001231 |

| hsa-miR-887-3p | 2.868279 | 0.033735 |

| hsa-miR-135a-3p | 2.717766 | 0.03624 |

| hsa-miR-4634 | 2.264031 | 0.039541 |

| hsa-miR-718 | 2.204079 | 0.011618 |

| hsa-miR-422a | 2.180337 | 0.033338 |

| hsa-miR-5585-3p | 2.140601 | 0.024133 |

| hsa-miR-8089 | 2.08933 | 0.008314 |

| hsa-miR-6760-3p | 2.02642 | 0.014468 |

| hsa-miR-615-3p | 2.022371 | 0.033735 |

| hsa-miR-1181 | 1.971624 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-4476 | 1.904539 | 0.026744 |

| hsa-miR-197-5p | 1.886881 | 0.033715 |

| hsa-miR-6133 | 1.845085 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-7846-3p | 1.83585 | 0.017607 |

| hsa-miR-5787 | 1.829065 | 0.017607 |

| hsa-miR-6858-3p | 1.826295 | 0.028224 |

| hsa-miR-4646-5p | 1.779853 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-630 | 1.766601 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-3646 | 1.748758 | 0.011618 |

| hsa-miR-583 | 1.748449 | 0.017607 |

| hsa-miR-3679-5p | 1.736775 | 0.033735 |

| hsa-miR-3622b-5p | 1.725858 | 0.014468 |

| hsa-miR-1185-2-3p | 1.654606 | 0.013747 |

| hsa-miR-4769-5p | 1.653051 | 0.027191 |

| hsa-miR-6125 | 1.63833 | 0.013747 |

| hsa-miR-125a-3p | 1.638016 | 0.033735 |

| hsa-miR-6068 | 1.636307 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-4530 | 1.627722 | 0.029275 |

| hsa-miR-7107-5p | 1.625659 | 0.033735 |

| hsa-miR-601 | 1.610057 | 0.012687 |

| hsa-miR-5703 | 1.598128 | 0.012692 |

| hsa-miR-3960 | 1.593793 | 0.021971 |

| hsa-miR-2861 | 1.537284 | 0.026802 |

miRNA/miR, microRNA; has, human.

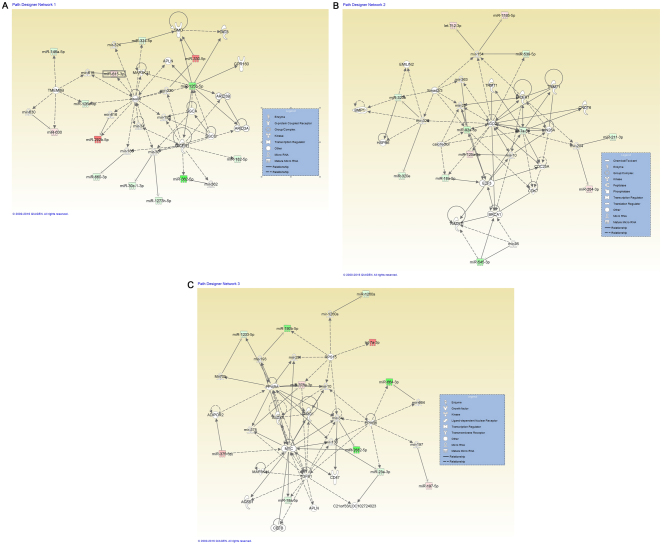

IPA® Network analysis

One of the aims of the present study was to evaluate the potential significance of altered miRNAs at the cellular and molecular level, mediated by DDW. IPA® analysis was performed for all miRNAs with an altered expression level for the assessment of the potential consequences by evaluating the networks; the principle of the gene network interactions were discussed in a previous study (28). Fig. 1 presents the integration of the altered miRNAs transcripts in with the highest significance score, including organismal injury and abnormalities, reproductive system disease, cancer (Fig. 1A), inflammatory diseases, the inflammatory response, organismal injury and abnormalities (Fig. 1B), and hematological diseases and hereditary disorders (Fig. 1C). The IPA® analysis also classified the altered miRNAs transcripts in terms of the most relevant diseases and biological function (Table II) or molecular functions (Table III) associated with DDW exposure.

Figure 1.

miRNA-miRNA gene network interactions generated using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), for miRNAs altered in deuterium-depleted water-maintained DLD-1 cells vs. those maintained in standard conditions. (A) A representative network for organismal injury and abnormalities, reproductive system disease and cancer, containing 13 miRNAs with Dicer1 as a central molecule. (B) Network representative for inflammatory diseases, inflammatory response, and organismal injury and abnormalities, containing 12 miRNAs with Dicer1, Ago2 and E2F3 as key molecules. (C) Network representative for cancer containing 12 miRNAs, hematological diseases and hereditary disorders, with Myc and TGFβ1 as central molecules. miRNAs expression changes are depicted in red (upregulation) and green (downregulation), and the direct target genes that interact with altered miRNAs are grey. miRNA/miR, microRNA; Ago2, Argonaute 2; E2F3, transcription factor E2F3; TGF, transforming growth factor.

Table II.

Most significant diseases and functions altered in cells cultured in deuterium-depleted water vs. those maintained in standard conditions.

| Disease/function | P-value | Molecules (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory disease | 1.90E-02-3.95E-12 | 13 |

| Inflammatory response | 3.22E-02-3.95E-12 | 13 |

| Organismal injury and abnormalities | 4.99E-02-3.95E-12 | 29 |

| Cancer | 4.86E-02-3.59E-11 | 18 |

Table III.

Most significant molecular functions from the miRNA pattern of cell cultured in deuterium-depleted water vs. those maintained in standard conditions.

| Name | P-value | Molecules (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | 4.26E-03-8.72E-05 | 3 |

| Cellular function and maintenance | 3.77E-02-8.72E-05 | 3 |

| Cell cycle | 3.91E-02-1.00E-03 | 3 |

| Cellular movement | 3.98E-02-1.62E-03 | 5 |

| Cell morphology | 2.53E-02-2.84E-03 | 1 |

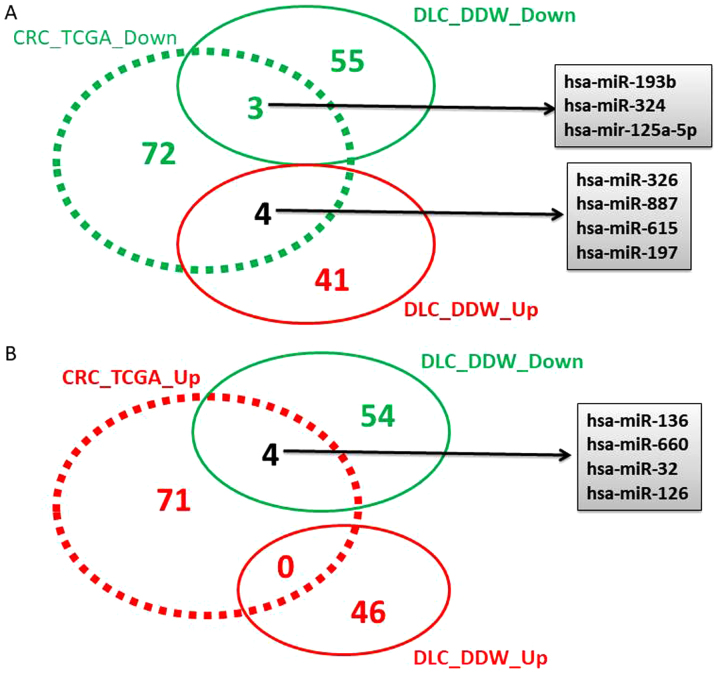

Overlapping the altered miRNA pattern in DDW cells with TGCA data

Following TCGA data analysis, 163 miRNAs with altered expression levels were identified, 82 downregulated and 81 overexpressed (data not shown), considering a cut-off value of −1.5≤FC≥1.5 and P<0.05. A Venn diagram was constructed to identify the overlap of differentially regulated miRNAs obtained from the TCGA analysis for colorectal cancer, and the altered miRNA pattern obtained in the case of DLD-1 cells maintained in DDW vs. SC (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of (A and B) overexpressed (red) and downregulated (green) has-miRs from The Cancer Genome Atlas data overlapped with the cell culture data. hsa-miR, human microRNA; DOWN, downregulated; UP, upregulated; CRC_TCGA, altered miRNA pattern in the colorectal The Cancer Genome Atlas patient cohort; DLC_DDW, altered miRNA pattern for cells cultured in deuterium-depleted water vs. those maintained in standard conditions.

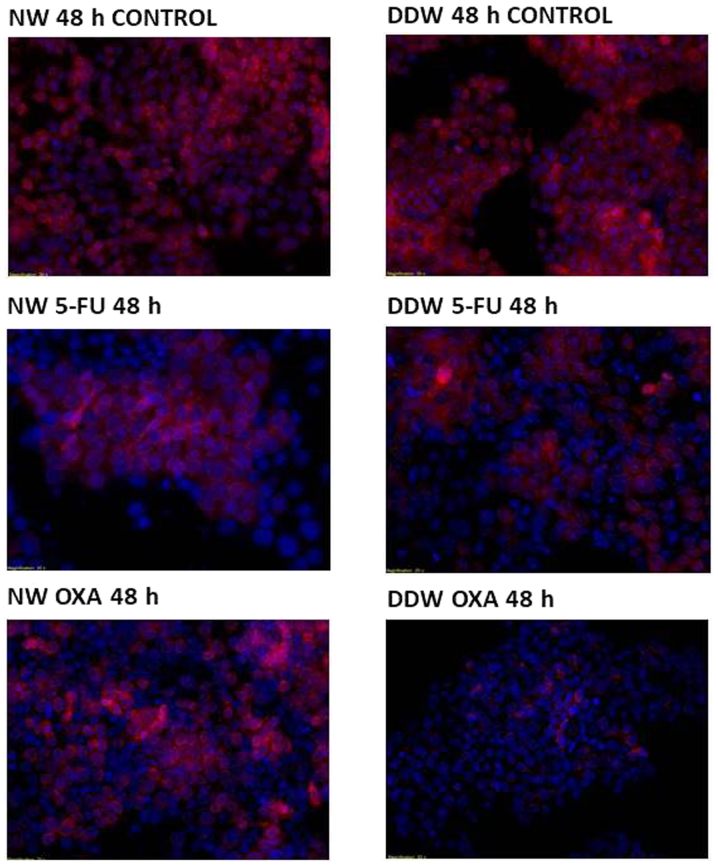

DDW augmentation exhibits a weak pro-apoptotic effect in 5-FU and oxaliplatin treated DLD-1 cells

In order to determine whether DDW exhibits an adjuvant effect with 5-FU and oxaliplatin treatment on DLD-1 cells, cell viability was assessed via fluorescent microscopy using TMRE/Hoechst double staining. A common hallmark of apoptosis is the fragmentation and condensation of the nucleus.

In SC, no modifications of the nuclei were observed, however 5-FU treatment appears to be complemented by a decreased concentration of deuterium, with nuclei displaying slight structural modifications at 48 h following 5-FU exposure in the presence of DDW. The mitochondrial membrane potential remains unaffected (Fig. 3), with cells retaining their viability independent of deuterium concentrations (Table IV). By constrast, oxaliplatin treatment dissipates the mitochondrial membrane potential, with cells preserving the nucleic integrity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Apoptosis evaluation in DLD-1 treated colorectal cell line. The hallmarks of apoptosis were assesed using Hoechst/tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester double-staining. Nuclei are visualized as blue, mitochondiral membranes are visualized as red (magnification, ×20). Cells were cultivated in RPMI-1640 medium in standard conditions for 64 passages and in RPMI-1640 medium with a low deuterium concentration for 66 passages. Cells were exposed for 48 h to 5-FU and OXA, and evaluated for apotosis by fluorescence at 560/595 nm. DDW, deuterium-depleted water; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; OXA, oxaliplatin.

Table IV.

IC50 concentrations for 5-FU and oxaliplatin obtained in DLD-1 cells.

| RPMI medium | Cytostatic agent | IC50 24 h (µM) | IC50 48 h (µM) | IC50 72 h (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | 5-FU | 7.64 | 4.64 | – |

| Oxaliplatin | 4.57 | 4.60 | 4.63 | |

| DDW | 5-FU | 4.42 | 3.74 | 7.30 |

| Oxaliplatin | 21.04 | 4.92 | 6.09 |

IC50, concentration of an inhibitor where the response is reduced by half; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; SC, standard conditions; DDW, deuterium-depleted water.

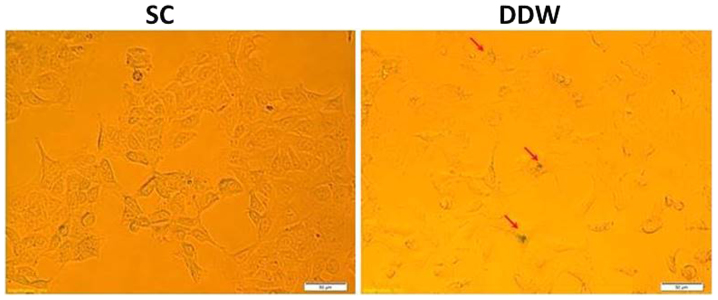

Senescence in the cancer cell line DLD-1 is activated by DDW

It was investigated whether maintaining the cells in DDW was able to induce senescence in the DLD-1 cell line, and therefore offer a novel platform for cancer therapeutics. DLD-1 cells were cultivated for 13 passages in SC or medium prepared with DDW, and were assessed for senescence via detection of β-galactosidase expression. The results indicated a low induction of senescence in cells cultivated in DDW medium compared with those maintained in SC (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of senescence in DLD-1 colorectal cell line exposed to a low concentration of deuterium. Cells were cultivated for 13 passages in RPMI-1640 medium in SC or low deuterium, and assessed for expression of β-galactosidase (red arrows), which is present in senescent cells only. A slight activation of senescence was observed in cells cultivated in DDW growth medium. DDW, deuterium-depleted water.

Discussion

Supplementation of cancer therapy with different adjuvant systems have been reported to induce notable benefits in a number cancer types, including colorectal cancer (29). The most well-known combination is that of oxaliplatin and 5-FU (30,31). These systems were developed to counteract the activated mechanisms that sustain tumor development, and particularly to avoid chemoresistance (32). Therefore, there is an urgent demand for evaluating novel adjuvant systems that may be implemented in clinical practice (29,32).

Chemoresistance has been associated with altered enzyme functions that are associated with microRNA maturation and primarily Dicer protein activity (19). Taking into account that chemoresistance is the main obstacle to the success of cancer treatment (1,2), the modulation of miRNA patterns may be used to avoid activation of drug resistance mechanism and to increase the therapeutic efficacy of classical chemotherapy (17,33).

In previous studies, deuterium depletion has been suggested to exhibit antiproliferative effects in cells exposed to low concentrations of this natural isotope of hydrogen (9,10) and to alter gene expression patterns in cancer cells (10). However, to the best of our knowledge, whether deuterium depletion influences the response of cancer cells to standard chemotherapy has not yet been investigated. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate if deuterium concentration in the extracellular environment was able to modulate the response of DLD-1 colorectal cancer cells to the standard chemotherapeutic regimen. Oxaliplatin and 5-FU were selected as chemotherapeutic agents following National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for colorectal cancer disease (34). In the present study, the effects of deuterium depletion in DLD-1 cancer cells subjected to 5-FU and Oxaliplatin treatment were assessed via microarray analysis to observe the differences in the molecular profile of miRNAs and, implicitly, of senescence and apoptosis genes modulated by these miRNAs.

Senescence represents a growth-arrest aging process that has been associated with degenerative pathologies in cells subjected to stress stimuli, leading to loss of function (35,36). Senescence has also been recognized as a potent antiproliferative mechanism for suppressing tumor growth and progression, and has been exploited as a potential anti-cancer target (37,38).

The capacity to regulate the miRNA pattern in normal, physiological conditions may have implications on cell fate. The modulation of released miRNA patterns may be considered as a promising strategy for increased therapeutic efficacy and particularly for avoiding the activation of drug resistance mechanisms. The modulation of miRNA-processing enzymes, Dicer1 and miRNAs may be important for senescence-related processes (39,40). The network presented in Fig. 1A, presents the key transcript Dicer1, which promotes senescence and cell differentiation (39,40). IPA® networks revealed that Dicer1 is targeted by several miRNAs, including miR-362-5p, miR-182-5p and miR-125-5p. The second network (Fig. 1B) is centered on Dicer1, Argonaute 2 and transcription factor E2F3, which are associated with selective autophagy (41), and are able to target cell cycle regulators, cell proliferation and apoptosis (42–44). Defective autophagy has been demonstrated to accelerate senescence (45), whereas the stimulation of autophagy may be an effective, novel therapeutic strategy, which may be used to increase the response to classical chemotherapy. The miRNA profiling data revealed two downregulated miRNAs (miR-23b and miR-193b) and one overexpressed transcript (let-7b) that are known to regulate autophagy, which was confirmed only partially by apoptosis and senescence evaluation with a microscope.

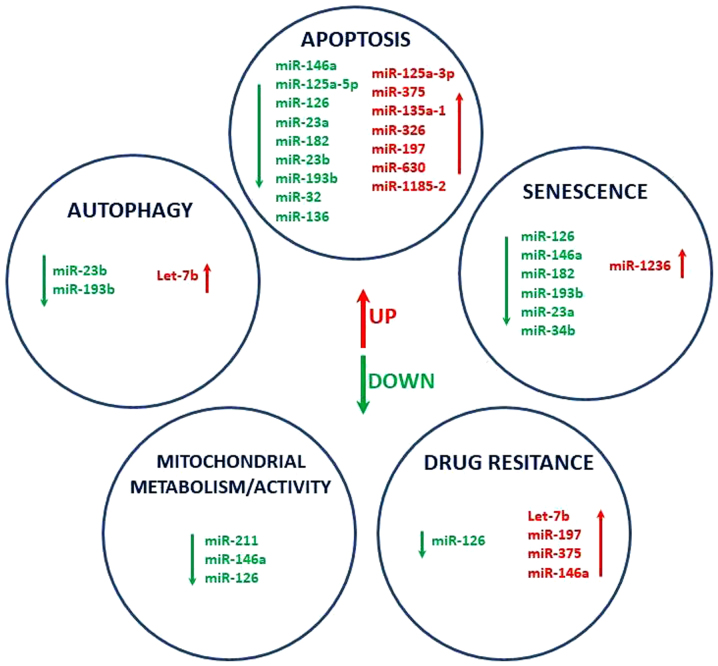

A previous study has demonstrated that transforming growth factor (TGF)β- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-signaling are associated with oxidative stress and DNA damage, and share a phenotype of drug-induced paracrine ‘bystander senescence’ (46). Therefore, miRNAs targeting TGFβ pathways may collaborate to induce and/or maintain this bystander senescence (46). The present miRNA profiling data reveals that DDW may contribute to phenotypic alterations of senescent cells, autophagy, redox homeostasis and mitochondrial metabolism by modulating the expression of key regulatory transcripts (Fig. 5). Further investigation on the effect of miRNA release patterns may elucidate the complex roles of miRNAs in the response to therapy.

Figure 5.

miRNAs as key modulators of apoptosis, autophagy, mitochondrial activity drug resistance and senescence. miRNA/miR, microRNA.

In conclusion, the establishment of adjuvant therapy to allow premature senescence of tumor cells may be expressed by the modulation of apoptosis, autophagy, senescent drug resistance or mitochondrial activity miRNA transcripts, thus leading to the activation of specific target genes with important roles in cell fate. Exosomal-released miRNAs represent an effective method to monitor the response to DDW as a possible adjuvant therapy, and to identify novel activated mechanisms associated with drug resistance. Furthermore, DDW may be an adjuvant treatment in colorectal cancer, but a better comprehension of the associated molecular mechanisms will be necessary for developing novel efficient therapeutic strategies, where the transcriptomic pattern serves an important role.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mecro System SRL (Bucharest, Romania) for providing Qlarivia deuterium-depleted water as part of the GenCanD project.

Funding

The present study is part of the research grant ‘New strategies for improving life quality and survival in cancer patients: Molecular and clinical studies of the tumor genome in deuterium-depleted water treatment augmentation-GenCanD’. The research grant was supplied by Iuliu-Hatieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy (Cluj-Napoca, Romania; grant no. 128/2014; PN-II-PT-PCCA-2013-4-2166).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

SC, VP and AJ performed the cell culture experiments. LR and LP performed the evaluations using the microscope and were responsible for the RNA extraction and quality control. CB performed the microarray study. RCP performed the bioinformatics analysis. CI and IBN were responsible for the study design, and supervising and revising of the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Chabner BA, Roberts TG., Jr Timeline: Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibalová L, Sereš M, Rusnák A, Ditte P, Labudová M, Uhrík B, Pastorek J, Sedlák J, Breier A, Sulová Z. P-glycoprotein depresses cisplatin sensitivity in L1210 cells by inhibiting cisplatin-induced caspase-3 activation. Toxicol In Vitro. 2012;26:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahon KL, Henshall SM, Sutherland RL, Horvath LG. Pathways of chemotherapy resistance in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18:R103–R123. doi: 10.1530/ERC-10-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qu B, Aho KS, Li C, Kang S, Sillanpää M, Yan F, Raymond PA. Greenhouse gases emissions in rivers of the Tibetan Plateau. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16573. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16552-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goncharuk VV, Kavitskaya AA, Romanyukina IY, Loboda OA. Revealing water's secrets: Deuterium depleted water. Chem Cent J. 2013;7:103. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-7-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kushner DJ, Baker A, Dunstall TG. Pharmacological uses and perspectives of heavy water and deuterated compounds. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999;77:79–88. doi: 10.1139/y99-005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basov AA, Bykov IM, Baryshev MG, Dzhimak SS, Bykov MI. Determination of deuterium concentration in foods and influence of water with modified isotopic composition on oxidation parameters and heavy hydrogen isotopes content in experimental animals. Vopr Pitan. 2014;83:43–50. (In Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehakova R, Klimentova J, Cebova M, Barta A, Matuskova Z, Labas P, Pechanova O. Effect of deuterium-depleted water on selected cardiometabolic parameters in fructose-treated rats. Physiol Res. 2016;65(Supplementum 3):S401–S407. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cong FS, Zhang YR, Sheng HC, Ao ZH, Zhang SY, Wang JY. Deuterium-depleted water inhibits human lung carcinoma cell growth by apoptosis. Exp Ther Med. 2010;1:277–283. doi: 10.3892/etm_00000043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gyöngyi Z, Budán F, Szabó I, Ember I, Kiss I, Krempels K, Somlyai I, Somlyai G. Deuterium depleted water effects on survival of lung cancer patients and expression of Kras, Bcl2, and Myc genes in mouse lung. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65:240–246. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2013.756533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann J, Bader Y, Horvath Z, Saiko P, Grusch M, Illmer C, Madlener S, Fritzer-Szekeres M, Heller N, Alken RG, Szekeres T. Effects of heavy water (D2O) on human pancreatic tumor cells. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3407–3411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Zhu B, He Z, Fu H, Dai Z, Huang G, Li B, Qin D, Zhang X, Tian L, et al. Deuterium-depleted water (DDW) inhibits the proliferation and migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells in vitro. Biomed Pharmacother. 2013;67:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bu H, Wedel S, Cavinato M, Jansen-Dürr P. MicroRNA regulation of oxidative stress-induced cellular senescence. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:2398696. doi: 10.1155/2017/2398696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braicu C, Cojocneanu-Petric R, Chira S, Truta A, Floares A, Petrut B, Achimas-Cadariu P, Berindan-Neagoe I. Clinical and pathological implications of miRNA in bladder cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:791–800. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S72904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irimie AI, Sonea L, Jurj A, Mehterov N, Zimta AA, Budisan L, Braicu C, Berindan-Neagoe I. Future trends and emerging issues for nanodelivery systems in oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:4593–4606. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S133219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braicu C, Tomuleasa C, Monroig P, Cucuianu A, Berindan-Neagoe I, Calin GA. Exosomes as divine messengers: Are they the Hermes of modern molecular oncology? Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:34–45. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ling H, Pickard K, Ivan C, Isella C, Ikuo M, Mitter R, Spizzo R, Bullock M, Braicu C, Pileczki V, et al. The clinical and biological significance of MIR-224 expression in colorectal cancer metastasis. Gut. 2016;65:977–989. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braicu C, Calin GA, Berindan-Neagoe I. MicroRNAs and cancer therapy-from bystanders to major players. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:3561–3573. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320290002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geretto M, Pulliero A, Rosano C, Zhabayeva D, Bersimbaev R, Izzotti A. Resistance to cancer chemotherapeutic drugs is determined by pivotal microRNA regulators. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:1350–1371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramalingam S, Subramaniam D, Anant S. Manipulating miRNA expression: A novel approach for colon cancer prevention and chemotherapy. Curr Pharmacol Rep. 2015;1:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s40495-015-0020-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taranu I, Braicu C, Marin DE, Pistol GC, Motiu M, Balacescu L, Beridan Neagoe I, Burlacu R. Exposure to zearalenone mycotoxin alters in vitro porcine intestinal epithelial cells by differential gene expression. Toxicol Lett. 2015;232:310–325. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braicu C, Cojocneanu-Petric R, Jurj A, Gulei D, Taranu I, Gras AM, Marin DE, Berindan-Neagoe I. Microarray based gene expression analysis of Sus Scrofa duodenum exposed to zearalenone: Significance to human health. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:646. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2984-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pistol GC, Braicu C, Motiu M, Gras MA, Marin DE, Stancu M, Calin L, Israel-Roming F, Berindan-Neagoe I, Taranu I. Zearalenone mycotoxin affects immune mediators, MAPK signalling molecules, nuclear receptors and genome-wide gene expression in pig spleen. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irimie AI, Braicu C, Pileczki V, Petrushev B, Soritau O, Campian RS, Berindan-Neagoe I. Knocking down of p53 triggers apoptosis and autophagy, concomitantly with inhibition of migration on SSC-4 oral squamous carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;419:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2751-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braicu C, Pileczki V, Irimie A, Berindan-Neagoe I. p53siRNA therapy reduces cell proliferation, migration and induces apoptosis in triple negative breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;381:61–68. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pileczki V, Braicu C, Gherman CD, Berindan-Neagoe I. TNF-α gene knockout in triple negative breast cancer cell line induces apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;14:411–420. doi: 10.3390/ijms14010411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piechota M, Sunderland P, Wysocka A, Nalberczak M, Sliwinska MA, Radwanska K, Sikora E. Is senescence-associated β-galactosidase a marker of neuronal senescence? Oncotarget. 2016;7:81099–81109. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krämer A, Green J, Pollard J, Jr, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in ingenuity pathway analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:523–530. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrato A. Adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2008;2(4 Suppl):S42–S46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berindan-Neagoe I, Braicu C, Pileczki V, Cojocneanu Petric R, Miron N, Balacescu O, Iancu D, Ciuleanu T. 5-Fluorouracil potentiates the anti-cancer effect of oxaliplatin on Colo320 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2013;22:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshikawa R, Kusunoki M, Yanagi H, Noda M, Furuyama JI, Yamamura T, Hashimoto-Tamaoki T. Dual antitumor effects of 5-fluorouracil on the cell cycle in colorectal carcinoma cells: A novel target mechanism concept for pharmacokinetic modulating chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1029–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braicu C, Tudoran O, Balacescu L, Catana C, Neagoe E, Berindan-Neagoe I, Ionescu C. The significance of PDGF expression in serum of colorectal carcinoma patients-correlation with Duke's classification. Can PDGF become a potential biomarker? Chirurgia (Bucur) 2013;108:849–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braicu C, Catana C, Calin GA, Berindan-Neagoe I. NCRNA combined therapy as future treatment option for cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:6565–6574. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140826153529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benson AB III, Venook AP, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, Chen YJ, Cooper HS, Engstrom PF, Enzinger PC, Fenton MJ, Fuchs CS, et al. Colon cancer, version 3.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:1028–1059. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campisi J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:685–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cerella C, Grandjenette C, Dicato M, Diederich M. Roles of apoptosis and cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17:405–415. doi: 10.2174/1389450116666150202155915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roninson IB. Tumor cell senescence in cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2705–2715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ewald JA, Desotelle JA, Wilding G, Jarrard DF. Therapy-induced senescence in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1536–1546. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y, Wu D, Fei C, Guo J, Gu S, Zhu Y, Xu F, Zhang Z, Wu L, Li X, Chang C. Down-regulation of Dicer1 promotes cellular senescence and decreases the differentiation and stem cell-supporting capacities of mesenchymal stromal cells in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica. 2015;100:194–204. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.109769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorospe M, Abdelmohsen K. MicroRegulators come of age in senescence. Trends Genet. 2011;27:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibbings D, Mostowy S, Jay F, Schwab Y, Cossart P, Voinnet O. Selective autophagy degrades DICER and AGO2 and regulates miRNA activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1314–1321. doi: 10.1038/ncb2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bian XJ, Zhang GM, Gu CY, Cai Y, Wang CF, Shen YJ, Zhu Y, Zhang HL, Dai B, Ye DW. Down-regulation of Dicer and Ago2 is associated with cell proliferation and apoptosis in prostate cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:11571–11578. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prodromaki E, Korpetinou A, Giannopoulou E, Vlotinou E, Chatziathanasiadou Μ, Papachristou NI, Scopa CD, Papadaki H, Kalofonos HP, Papachristou DJ. Expression of the microRNA regulators Drosha, Dicer and Ago2 in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2015;38:307–317. doi: 10.1007/s13402-015-0231-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibbings D, Mostowy S, Voinnet O. Autophagy selectively regulates miRNA homeostasis. Autophagy. 2013;9:781–783. doi: 10.4161/auto.23694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grootaert MO, da Costa Martins PA, Bitsch N, Pintelon I, De Meyer GR, Martinet W, Schrijvers DM. Defective autophagy in vascular smooth muscle cells accelerates senescence and promotes neointima formation and atherogenesis. Autophagy. 2015;11:2014–2032. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1096485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hubackova S, Krejcikova K, Bartek J, Hodny Z. IL1- and TGFβ-Nox4 signaling, oxidative stress and DNA damage response are shared features of replicative, oncogene-induced, and drug-induced paracrine ‘bystander senescence’. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:932–951. doi: 10.18632/aging.100520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.