Abstract.

Japanese spotted fever (JSF) is a zoonosis transmitted by ticks carrying the pathogen Rickettsia japonica. The classic triad of JSF symptoms is high fever, erythema, and tick bite eschar. About 200 people in Japan develop the disease every year. Japanese spotted fever is also a potentially fatal disease. At Minami-Ise Municipal Hospital in Japan, 55 patients were diagnosed with JSF from 2007 to 2015, which was equivalent to 4.3% of the total JSF cases in Japan. In this retrospective study, we examined the medical records of these 55 JSF cases. Fever, erythema, eschar, and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) are characteristic clinical features of the disease. We confirmed four of these in the reviewed cases; however, eschar was not present in occasional cases. We confirmed that eosinopenia appeared in nearly all cases. Using fever, erythema, elevated CRP, and eosinopenia in diagnostic screening, our positivity rate was 90.9%. In our clinical practice, including eosinopenia improves the initial diagnosis of JSF.

INTRODUCTION

Japanese spotted fever (JSF) was first described by Mahara et al.1 in 1984. Japanese spotted fever emerges mainly during warm seasons, from April to November.2,3 The disease occurs mainly in warm areas along the Pacific side of southwest and central Japan2,4–6; there have also been reports of cases along the Sea of Japan coast and Korea.7–9 In Mie Prefecture, JSF has been reported on the south side of the Miya River,10 an area that includes the town of Minami-Ise. Over a nearly 8-year period from May 2007 to January 2015, there were 1,276 cases of JSF reported in Japan, with 277 cases in Mie Prefecture (21.7% of the total for Japan) and 55 cases at Minami-Ise Municipal Hospital (4.3% of the total for Japan).

Japanese spotted fever is caused by Rickettsia japonica. The disease develops in humans approximately 2–8 days after being bitten by a tick carrying the pathogen.2 The main characteristic clinical features of JSF are high fever, erythema with no pain or itching, and tick bite eschar.1,2 Erythema also appears on the extremities and trunk, as well as on the palms and soles of the feet.2 The main laboratory findings among JSF cases include leukocytosis or leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), and elevated liver enzymes.2,3

Treatment is generally with tetracycline, which is remarkably effective for JSF.3 Treatment with steroids is also effective.11 In previous reports, complications include disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), multiple organ failure, meningoencephalitis, central nervous disorders, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, among others.3,12 And, there have been reports of severe or fatal cases.2,3,13,14

The classic triad of JSF symptoms is high fever, erythema, and tick bite eschar. The purpose of our study is to elucidate new clinical findings, which are useful for early diagnosis and treatment of JSF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We included 55 patients diagnosed with JSF at Minami-Ise Municipal Hospital from May 2007 to January 2015. All patients were residents of Minami-Ise. We therefore investigated symptoms, signs, and laboratory results from the time of first contact to the end of treatment among JSF cases, by a review of medical records retrospectively.

The definitive diagnosis of JSF is based on laboratory data alone; detection of R. japonica antibody titers and/or R. japonica DNA from patient blood and/or eschar samples is by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Measurement of antibody titers is carried out manually by serologic testing, with indirect immunofluorescence assay using R. japonica (YH strain). The PCR method is based on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases and Medical Care for Infectious Patients Act of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. Conventional PCR is performed using primers targeting R. japonica DNA on a G-storm GS4 (Somerton Biotechnology Center, Somerset, United Kingdom); there are two types of primers. One contains primers R1 (5′-TCAATTCACAACTTGCCATT-3′) and R2 (5′-TTTACAAAATTCTAAAAACC-3′) which detect spotted fever group Rickettsia and typhus group Rickettsia. The other contains primers Rj5 (5′-CGCCATTCTACGTTACTACC-3′) and Rj10 (5′-ATTCTAAAAACCATATACTG-3′) which specifically amplify only R. japonica. Measurement of antibody titers and PCR method are not carried out at our hospital; therefore, we send all patient samples for testing to an external laboratory, the Mie Prefecture Health and Environment Research Institute.

This study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Mie University Graduate School of Medicine (No. 1476).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median patient age was 77 (24–92) years. A total 81.8% of patients were hospitalized and managed. And 80.0% had their first contact with our hospital within 5 days from symptom onset. Signs and symptoms are listed in Table 2. From the onset to the first contact, 52 patients had a symptom of fever. The average value of fever at the first contact was 38.3°C for males and 38.0°C for females. And, only one patient did not have fever or erythema. Among the 45 patients who were hospitalized and treated with antipyretics, 64.4% (29 of them) had fever of a remittent type; nearly all peaks of fever were between the evening and the next morning. The degrees and duration of fever, and the duration of fever after starting antipyretic therapy are presented in Table 3. Three cases had no fever at any time during the clinical course. (38 of 45) 84.4% of patients with fever were started on defervesce within 5 days of antipyretic therapy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence by age* | ||

| < 65 years | 0.20 | – |

| ≥ 65 years | 0.91 | – |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 27 | 49.1 |

| Female | 28 | 50.9 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 22 | 40.0 |

| Dyslipidemia | 12 | 21.8 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 | 5.5 |

| Alzheimer-type dementia | 1 | 1.8 |

| Bronchial asthma | 1 | 1.8 |

| Gastric cancer | 1 | 1.8 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 | 1.8 |

| Chronic heart failure | 1 | 1.8 |

| Old myocardial infarction | 1 | 1.8 |

| Duration from symptom onset to initial diagnosis (days)† | ||

| 1 | 3 | 5.5 |

| 2 | 7 | 12.7 |

| 3 | 15 | 27.3 |

| 4 | 10 | 18.2 |

| 5 | 9 | 16.4 |

| 6 or more | 5 | 9.1 |

| Unknown | 6 | 10.9 |

Per 1,000 population.

Average from onset to initial diagnosis was 2.7 days.

Table 2.

Clinical features at the first contact

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Fever from the onset to the first contact | 52 | 94.5 |

| Malaise | 22 | 40.0 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms* | 21 | 38.2 |

| Headache | 9 | 16.4 |

| Arthralgia | 7 | 12.7 |

| Sore throat and cough | 6 | 10.9 |

| Myalgia | 3 | 5.5 |

| Aware of tick bite† | 6 | 10.9 |

| Signs | ||

| SBP ≤ 90 mm of Hg | 1‡ | 2.0 |

| Impaired consciousness§ | 3‖ | 5.6 |

| Erythema | 51 | 92.7 |

| Eschar | 34 | 61.8 |

SBP = systolic blood pressure. Note: patient total = 55.

Gastrointestinal symptoms include anorexia, abdominal pain, vomiting, and nausea.

Patients were aware that they had been bitten by a tick.

N = 50.

One case could not be diagnosed because the patient had dementia.

N = 54.

Table 3.

Degree and duration of fever, and duration required for defervescence

| Fever* | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| From the onset to the first contact | ||

| ≥ 39°C | 21 | 38.2 |

| ≥ 38°C | 50 | 90.9 |

| ≥ 37.5°C | 52 | 94.5 |

| Fever duration from initiation of treatment to defervescence† | ||

| Within 3 days | 17 | 37.8 |

| Within 4 days | 32 | 71.1 |

| Within 5 days | 38 | 84.4 |

Total patients = 55.

Total patients = 45.

Most patients arrived at our hospital in a state of clear consciousness. Three patients had mildly impaired consciousness and one had dementia. Hypotension was observed in one case; however, this patient did not have impaired consciousness or oliguria, and therefore did not meet the criteria for shock.

At the first contact, erythema was observed in most patients. And, in 80.0% (44 of 55) of patients, erythema appeared in the extremities. One patient had no erythema at any time during the clinical course. In another patient, erythema had changed to pigmentation. Eschar was present among most of the patients. The positivity rate for eschar PCR results was 88.2% (30 of 34 patients), whereas at the same time, the positivity rate for blood PCR was 45.3% (24 of 53 patients). Only six patients realized that they had been bitten by a tick; most patients did not notice the bite.

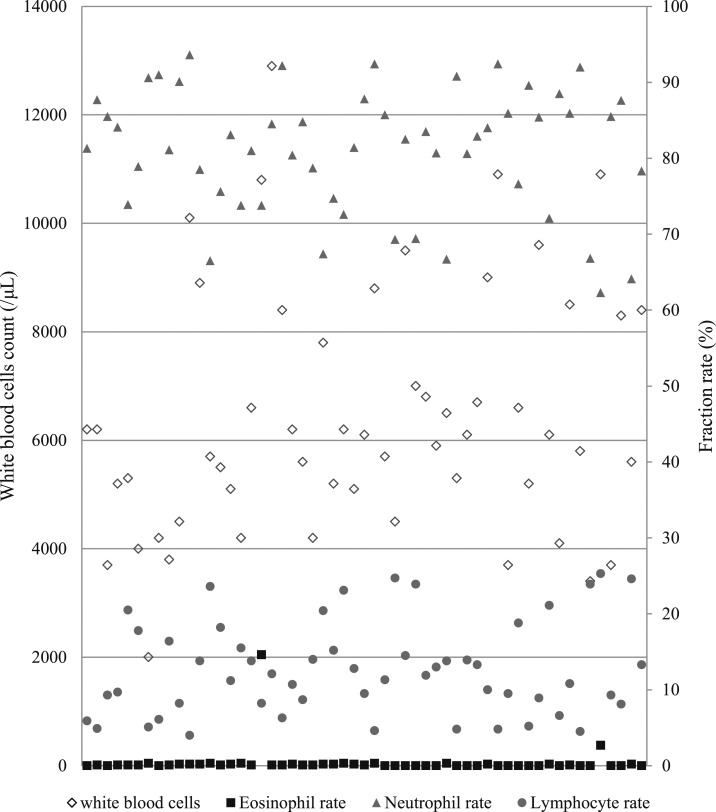

Laboratory examination results are shown in Table 4. C-reactive protein was at high levels in all cases tested. A total of 81.8% of patients had elevated liver enzymes and 52.7% had thrombocytopenia. All cases had eosinopenia, except for those with an allergic reaction. The eosinophil rate are shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Rapid laboratory test data at the first contact

| Reference interval* | Mean | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 0.2–1.3 | 0.73 | 0.3–1.8 |

| AST (IU/L) | 10–35 | 60.7 | 15–226 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 10–35 | 38.3 | 7–195 |

| LDH (IU/L) | 110–225 | 310.1 | 170–643 |

| CK (IU/L) | 20–200 | 289.1 | 46–3,086 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 9.0–22.0 | 18.1 | 7.4–52 |

| SCr (mg/dL) | 0.50–1.10 | 0.878 | 0.41–2.53 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | ≥ 60 | 63.84 | 20.4–127.8 |

| CRP† (mg/dL) | ≤ 0.3 | 7.745 | 0.6–21.97 |

| WBC (/μL) | 4,000–9,000 | 6,405 | 2,000–12,900 |

| Neutrophil count (/μL) | 1,800–6,390 | 5,194.1 | 1,812–10,900.5 |

| Neutrophil rate (%) | 45–71 | 81.0 | 62.3–93.6 |

| Lymphocyte count (/μL) | 1,000–4,050 | 803.2 | 102.0–2,757.7 |

| Lymphocyte rate (%) | 25–45 | 12.7 | 4.0–25.3 |

| Monocyte count (/μL) | 40–450 | 343.5 | 54–1,228.5 |

| Monocyte rate (%) | 1–5 | 5.5 | 1.0–18.9 |

| Eosinophil count (/μL) | 40–450 | 40.00 | 0–1,576.8 |

| Eosinophil rate (%) | 1.0–5.0 | 0.4 | 0–14.6 |

| Basophil count (/μL) | 0–40 | 24.6 | 0–259.2 |

| Basophil rate (%) | 0–1 | 0.4 | 0–2.4 |

| PLT (/μL) | 130,000–140,000 | 133,000 | 42,000–239,000 |

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; BUN = blood urea nitrogen; CK = creatine kinase; CRP = C-reactive protein; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; PLT = platelets; SCr = serum creatinine; T-Bil = total bilirubin; WBC = white blood cells. Note: patient total = 55.

N = 54.

Reference intervals refer to those of Minami-Ise Municipal Hospital.

Figure 1.

Distribution of white blood cells count and fraction rate.

In our study, there were two severe cases of JSF. One case was DIC. Another patient had takotsubo cardiomyopathy; this patient died.

DISCUSSION

Japanese spotted fever was described for the first time in 1984 in Tokushima Prefecture of Japan. As of 2017, JSF had appeared in 28 Japanese prefectures.15 In Mie Prefecture, JSF has been reported since 2005. Mie Prefecture is a predilection site for JSF, and the town of Minami-Ise has the highest incidence of disease in the area. The occurrence area of JSF and other tick-borne diseases has been expanding, especially in warm regions of Japan.1,13,15 Therefore, we consider that it is important to inform physicians and medical institutions about the disease, even in regions where no JSF has been observed.

The classic triad of JSF symptoms is fever, erythema, and eschar. In our study, almost all patients had fever. As described earlier, remittent fever was common,2 and most patients defervesced within 5 days of treatment. Japanese spotted fever and scrub typhus are very similar diseases, as has been previously reported; patients with scrub typhus defervesce within 24 hours of the treatment.16 Of the classic triad of symptoms, eschar was found infrequently, in only about 60% of our patients. However, the positivity rate of PCR for definitive diagnosis of JSF was higher for eschar samples than for whole blood.

Regarding laboratory results, CRP was nearly always elevated in our cases. This is considered to reflect the status of the infection. Eosinopenia was observed in all patients except two, who were diagnosed with allergic disorders based on other test results. Eosinopenia is considered a good marker of bacteremia and is suspected of increasing mortality.17 Elevated liver enzymes and thrombocytopenia were also observed among our patients, as well as high or low leukocyte blood counts.

Based on these results, we consider fever, erythema, elevated CRP, and eosinopenia to be good markers of JSF, even when there is no eschar present. In our study, the positivity rate of diagnosis based on these four features was 90% or more for each item, and 90.9% of patients had all four features. There were no patients with JSF who did not present with all four symptoms. With respect to these features in a primary care setting, a comprehensive early diagnosis should be made in conjunction with other clinical symptoms and laboratory findings; it is important to initiate early treatment. In the past, Funato et al.18 have described about the relationship between JSF and eosinopenia in their English abstract; the text is only in Japanese and is a nonnumerical report about eosinopenia. In our study, we were able to deal with larger numbers of subjects than the previous study and did quantify eosinopenia in English.

To our knowledge, the JSF fatality rate has not yet been described in any peer-reviewed journals published in English. Rocky Mountains spotted fever (RMSF), which occurs in the United States, is a similar disease to JSF. The RMSF fatality rate has been described as less than 1%.19 In our study, one patient died. We consider that treatment and management of JSF are possible, even at smaller medical facilities such as our small hospital which was responsible for community medicine, if an initial diagnosis can be accurately made and prompt treatment initiated.

The limitation of this study is that we could not generalize the results to larger or other populations because this research was performed retrospectively at one rural hospital in Japan. No available analysis of specificity is another limitation in this study.

In conclusion, in addition to fever, erythema, and elevated CRP, eosinopenia is an effective and useful tool that can be used for early diagnosis of JSF, even when there is no eschar present.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the patients and their families for participating in our study, the physicians and staff of Minami-Ise Municipal Hospital for their efforts in disease control and prevention as well as their support, and Shigehiro Akachi (Mie Prefecture Health and Environment Research Institute) for his technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahara F, et al. 1985. The first report of the rickettsial infections of spotted fever group in Japan: three clinical cases [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 59: 1165–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahara F, 1997. Japanese spotted fever: report of 31 cases and review of the literature. Emerg Infect Dis 3: 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodama K, Senba T, Yamauchi H, Nomura T, Chikahira Y, 2003. Clinical study of Japanese spotted fever and its aggravating factors. J Infect Chemother 9: 83–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiho I, Tokieda M, Ohtawara M, Uchiyama T, Uchida T, 1988. Occurrence of rickettsiosis of spotted fever group in Chiba Prefecture of Japan. J Med Sci Biol 41: 69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiya S, Takahashi N, Yasuoka T, Komatsu T, Suzuki H, 2000. Japanese spotted fever cases in Kochi prefecture. Jpn J Infect Dis 53: 27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takao S, Kawada Y, Ogawa M, Fukuda S, Shimazu Y, Noda M, Tokumoto S, 2000. The first reported case of Japanese spotted fever in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 53: 216–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itagaki A, Matsuda Y, Hoshina K, 2000. Japanese spotted fever in Shimane Prefecture–outbreak and place of infection. Jpn J Infect Dis 53: 73–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noji Y, et al. 2005. The first reported case of spotted fever in Fukui Prefecture, the northern part of central Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 58: 112–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang WJ, Kim JH, Choi YJ, Jung KD, Kim YG, Lee SH, Choi MS, Kim IS, Walker DH, Park KH, 2004. First serologic evidence of human spotted fever group rickettsiosis in Korea. J Clin Microbiol 42: 2310–2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo M, Nishii M, Gabazza EC, Kurokawa I, Akachi S, 2010. Nine cases of Japan spotted fever diagnosed at our hospital in 2008. Int J Dermatol 49: 430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara F, Hibi S, Imashuku S, 1993. Hypercytokinemia in hemophagocytic syndrome. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 15: 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakata R, Motomura M, Tokuda M, Nakajima H, Masuda T, Fukuda T, Tsujino A, Yoshimura T, Kawakami A, 2012. A case of Japanese spotted fever complicated with central nervous system involvement and multiple organ failure. Intern Med 51: 783–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seki M, et al. 2006. Severe Japanese spotted fever successfully treated with fluoroquinolone. Intern Med 45: 1323–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura T, Fujimoto T, Ebisutani C, Horiguchi H, Ando S, 2007. The first fatal case of Japanese spotted fever confirmed by serological and microbiological tests in Awaji Island, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis 60: 241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan , 2017. For Notification by Physicians and Veterinarians Based on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases and Medical Care for Infectious Patients Act of Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan Available at: http://www.kenkou.pref.mie.jp/weekly/kuni/pdf/2017/kuninew.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2018 [in Japanese].

- 16.Albisser M, Ritschard T, 1990. Imported tsutsugamushi fever [in German]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 120: 1109–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terradas R, Grau S, Blanch J, Riu M, Saballs P, Castells X, Horcajada JP, Knobel H, 2012. Eosinophil count and neutrophil-lymphocyte count ratio as prognostic markers in patients with bacteremia: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 7: e42860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funato T, Kitamura Y, Kawamura A, Uchida T, 1988. Rickettsiosis of spotted fever group encountered in Muroto area of Shikoku, Japan–clinical and epidemiological features of 23 cases [in Japanese]. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 62: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) , 2017. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) Statistics and Epidemiology Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/stats/index.html. Accessed February 19, 2018.