Abstract

Bone fractures are a worldwide public health concern. Previous studies have demonstrated that bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP7) gene transfer or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) transplantation may be a promising novel therapeutic approach. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to observe the effect of bone BMP7 transfer to MSCs on fracture healing. Bone marrow-derived MSCs (BMSCs) from New Zealand white rabbits were isolated and identified using flow cytometry. A recombinant BMP7 overexpressing adenovirus vector (Adv) was constructed and transfected into BMSCs. The expression of BMP7 was detected by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, immunofluorescence and western blotting. The present study additionally investigated the effect of BMP7 on the differentiation capacity of BMSCs. Finally, tissue-engineered bone was created with support material to verify the effect of BMP7-BMSCs on fracture healing. The results demonstrated that the expression of BMP7 was increased at the mRNA and protein levels in BMSCs following transfection with BMP7 overexpressing Adv. The results additionally demonstrated that the expression of BMP7 enhanced the differentiation capacity of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and had a promotional effect on fracture healing. Overall, these data suggest that Adv-BMP7 is useful for introducing foreign genes into BMSCs and will be a powerful gene therapy tool for bone regeneration and other tissue engineering applications in the future.

Keywords: BMSCs, BMP7, fracture healing, bone defects

Introduction

Bone defects are a common problem in the field of orthopedic medicine, and are usually the result of causes such as trauma, infection, congenital pseudarthrosis or cancer (1,2). If the lesion is small in size, a bone defect can repair and heal itself, but otherwise healing is difficult. So far autogenous bone remains the ideal bone grafting material for different kinds of bone graft surgery, but this is hindered by the shortage of donor tissue. The effect of other bone grafting methods, such as the use of decalcified bone grafts or allografts, are all worse than autogenous bone grafts, and are associated with problems including exudation, infection, immunological rejection, infection, bone graft non-fusion and other complications (3,4). Currently in clinical practice it is possible to inject growth factors into the lesion to enhance the ability to form new bone, but these are expensive, unpopular and have other shortcomings.

Consequently it is important to find a minimally-invasive, rapid and easy clinical technique for the promotion of bone healing. Tissue-engineered bone has self-renewal and reconstruction ability, as well as good biomechanical properties, so it is expected to be an ideal bone substitute (5–7). Cartilage seed cells and bone scaffold are core components of tissue-engineered bone, and study has shown that different components of tissue-engineered bone have different properties. To date however, a method of creating perfect and mature tissue-engineered bone has not been perfected. Currently bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) are the most widely-used cartilage seed cells in bone tissue engineering, with a series of advantages such as convenience, minimal damage to the donor, and good adhesion performance with a biological scaffold (8,9). There are a variety of different methods of transforming BMSCs into osteoblasts, but most of these center on use of cell growth factors in vitro or in vivo, or gene transfection.

Our study objectives are focusing on growth factors, including members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family, which contains the most important bone growth factors that play important roles in promoting formation, growth and repair of osseous tissue. Meanwhile the BMP family is also closely related to heterotopic ossification and plays an improtant role in tissue-engineered bone. In this study, we constructed a BMP7-overexpressing adenovirus vector and transfected it into BMSCs to enhance their differentiation capacity. We then used these to study the therapeutic effect of BMP7-overexpressiong BMSCs on healing of rabbit bone defects.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by Ethics Committee of 455th hospital of PLA (20121220). Six week-old, male and female New Zealand white rabbits were divided into three groups: A simple infusion of nano-HAp/Collagen (NHAC) group, an NHAC composite BMSC group and an NHAC composite highly-expressing MSC group. Each rabbit was depilated on both forelegs and weighed, then injected with 3% pentobarbital sodium 30 mg/kg, and a 3 cm skin incision was made along the radius. After the radius was exposed and the periosteum was peeled off, a 2 cm long cut was made in the bone in the middle of the radius using an electric saw, and the defect was implanted with NHAC/BMSCs or NHAC/BMP7-MSCc according to the groups. The control group was implanted with NHAC scaffold alone. The bone defect area was covered with muscle, the skin was sutured and the rabbits were returned to their cages to feed. Three-dimensional computed tomography (3D CT; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) was used for regular observation of bone integration.

Preparation and culture of bone marrow-derived MSCs

Six-week-old male New Zealand white rabbits were used for this experiment. Rabbits were anesthetized intravenously with 30 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (3%). After sterilizing the site, the greater trochanter of the femur was punctured under aseptic conditions with a no. 12 puncture needle wetted with 100 U/ml heparin. This was connected to a 10 ml injector which contained 0.2 ml 600 U/ml heparin. After mixing the cells thoroughly with the heparin solution, the mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at a speed of 800 r/min, the supernatant was discarded, and the cells were resuspended in L-DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and dispersed to create a single cell suspension. This was then layered onto the liquid surface of an isopyknic lymphocyte separation medium with density of 1.077, centrifuged for 20 min at a speed of 2,000 × g, and the cloudy mononuclear cell layer at the interface was removed to a new tube. The isolated mononuclear cells were washed twice in D-Hanks solution, resuspended in L-DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum, cell vitality was determined through trypan blue exclusion and the number of karyocytes was counted. Aliquots containing 1×105 cells/cm2 were inoculated into 25 cm2 culture bottles (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA), and cultured in a CO2 incubator under conditions of 37°C, 5% CO2 and saturated humidity. After 48 h the medium was changed to remove any suspended cells, and an inverted phase contrast microscope was used to examine the cell cultures. The purified BMSCs were further cultured with daily observation, and culture medium was replaced every 3 to 4 days. When the cells reached 70–80% confluence, cultures were digested with 0.25% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 2–5 h at 37°C, then passaged at a ratio of 1:2.

MTT assay

MSCs infected with Ad-BMP7-green fluorescent protein (GFP) or Ad-GFP were inoculated into 24-well microtiter plates, 5 replicates per group, and cultured for 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 or 12 days. Four hours before the end of the culture period, 50 µl of 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (5 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was added to each well and incubated for the final 4 h. The supernatant was discarded, the wells were shaken for 10 min after the addition of DMSO to each well, and the optical density (OD) value was read at 490 nm.

Determination of ALP activity

Following 72 h exposure to medium conditioned by Ad-BMP7-infected cells, BMSCs were rinsed twice with PBS then fixed for 10 min in 95% ethanol at room temperature. Staining was performed with an alkaline phosphatase kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Uninfected MSCs were used as the control group.

Growth curve analysis

Monolayer mesenchymal stem cells were resuspended in complete medium [DMEM + 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,)], then the cells (approximately 1×104/ml) were inoculated into 96-well microtiter plates at 200 µl/well. Cells were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C with saturated humidity, and a growth curve was drawn from the results of the MTT colorimetric assay, with time plotted against average absorbance in each phase.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Two hundred microliters of cell suspension was added to 1 ml of TRIzol reagent and shaken for 15 sec before centrifuging at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The colorless supernatant was then transferred into a new centrifuge tube with the same volume of isopropanol and allowed to stand for 10 min at room temperature, after which the cells were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, washed with 1 ml precooled 75% ethanol and centrifuged again at 7,500 × g. The supernatant was discarded and the RNA precipitate was dried at room temp. then dissolved in DEPC-treated H2O at 65°C for 10 min. The concentration of RNA was determined, and cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan), and analyzed by qPCR.

Construction of human BMP7 adenovirus plasmids and preparation of recombinant adenovirus

BMP7 amplification primers were designed and synthesized according to the gene sequence in GenBank. The primer sequences were as follows: BMP7 upstream primer was: 5′-gc aga tct atg cac gtg cgc tca ectg cg-3′, and a BglII restriction site was introduced, while the downstream primer was: 5′-gc gtc gac tta gtg gca gcc aca ggc cc-3′, and a SalI restriction site was introduced. Then the PCR products were cloned into the sequencing vector pGEM-T-Easy. The BMP7 gene fragment was successfully constructed and cloned into the site between BglII and SalI on the adenovirus shuttle vector Ad-Track-CMV. A DNA fragment between site XhoI and XbaI was separated from the IRES sequence in the pIRES vector, then cloned into plasmid pAdTrack-CMV, establishing the recombinant shuttle plasmid pAdTrack-CMV-BMP7 through the IRES sequence. AdEasier-1 cells and E. coli DH5α electroporation competent cells were prepared in 10% sterile glycerol (in an ice-bath), the recombinant plasmid pAdTrack-CMV-BMP7 was extracted and linearized by PmeI, and 1 µg of the fragment was obtained by electrophoresis. The isolated fragment was mixed with 20 µl adenovirus skeleton plasmid-competent AdEasier-1 cells, co-transformed into competent bacteria by electroporation, then screened in kanamycin LB medium, and the clones were picked out and plasmids extracted. Plasmids which were similar to pAdEasy-1 by agarose gel electrophoresis were selected and transferred into competent bacteria by electro-transformation. Recombinant adenovirus plasmids were named pAd-BMP7 after large scale isolation and Pad enzyme digestion. Then, 293 cells (2×106/well) were inoculated into culture dishes 24 h before transfection. When the cells reached 60–80% confluence, pAd-BMP7 plasmids were constructed and identified by PacI (NEB) restriction enzyme digestion, and 4 µg of the linearized plasmids were used for transfection of 293 cells. Transfection was performed using lipofectamine® 2000 according to the manual supplied with the kit, medium was replaced with fresh bovine serum after culture for 24 h, and the expression product of the GFP gene was observed by fluorescence microscopy 3 days later. Seven days later, 293 cells were collected and lysed by repeated freezing and thawing between liquid nitrogen and a 37°C water bath four times. The 293 cells were then re-transfected by viral supernatant and amplified, and 5 days later the cells were collected, then the precipitate was collected by centrifugation (1,500 × g, 7 min) and resuspended in 2 ml PBS per culture dish. After repeated freezing and thawing another four times, the infection and collection procedures were repeated, and the PBS-resuspended viral supernatant was collected and purified by cesium chloride (CsCl) gradient centrifugation. The 293 cells were inoculated into 6-well culture plates at 5×105 cells/well, and cultured until they reached 60–80% confluence. Next day, the cells were infected by doubling dilution with viral supernatant, and the expression product of the GFP gene was observed by fluorescence microscopy and the titer was determined (efu/l) 72 h later.

Determination of protein expression by western blotting

Fourteen days after viral transfection, two groups of BMSCs were collected and total protein was extracted using protein SDS PAGE loading buffer (Takara Bio, Inc.). The total protein was blotted onto a nitrocellulose filter after 10% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. The nitrocellulose filter was blocked in 5% skimmed milk powder for 1 h, then a goat anti-human hBMP7 antibody, (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) diluted 1:200, was added and incubated overnight at 4°C. The filter was washed and a rabbit anti-goat IgG secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), diluted 1:800, was added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After washing the filter, the expression of hBMP7 protein in the cells of the two groups was determined by the chemiluminescence detection method using a SuperSignal western blotting chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Determination of MSC surface markers by flow cytometry

MSCs were digested with pancreatin-containing EDTA, dead cells were removed with 7-AAD, FcR sealing was performed with FcR sealant and cells were centrifuged for 10 min (1,500 × g), then the supernatant was discarded and 20 µl of antibody labeled with a corresponding fluorophore were obtained. After separately adding monoclonal antibodies against CD29, CD44, CD34, and CD45 (BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA), the tubes were incubated in the dark in a 4°C refrigerator for 30 min then PBS was added before centrifugation and washing twice, after which they were resuspended in 300 µl PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). A control was set at the same time. In addition, all the cells and antibodies were stained with PI (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) after 30 min incubation. The quantity of dead cells was observed to assess whether or not it was significantly increased.

Examination of the MSC-scaffold composite by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The NHAC scaffold was kindly provided by Dr. Ly, Fudan University. The NHAC scaffold was soaked in culture medium, placed into a 24-well culture plate, and 0.2 ml of a suspension of osteoblasts at 2×105 cells/ml obtained from marrow were dropped into the carrier in each well. After 3 h when the cells had begun to adhere, residual culture medium was removed. Cells were co-cultured with carrier for 10 days, with the culture medium changed every 2–3 days, and the growth of the cells was measured under an inverted phase contrast microscope. At 3, 6 and 10 days, cocultured complexes were digested for 2–5 min with 0.25% trypsin at 37°C then the digestion was terminated with culture medium, the detached cells were pipetted to generate a uniform cell suspension, then the cells were counted using a blood cell counting method and the proliferation rates were calculated. Cell proliferation in the wells without scaffold was used as the control group. Complexes cocultured for 10 d were washed in D-Hank's solution, and stored under 2.5% glutaraldehyde fixed with 3% pentodialdehyde, then dehydrated through gradient ethanol, and gold-coated specimens were observed by scanning electron microscopy to assess cell growth in the scaffold with a JsM-5900 SEM (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

SPSS 20.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SE. The F-test was used to compare differences between groups (repeated measurement data). The χ2-test was used to compare the incidence of bone non-union between the different groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Morphology of rabbit MSCs

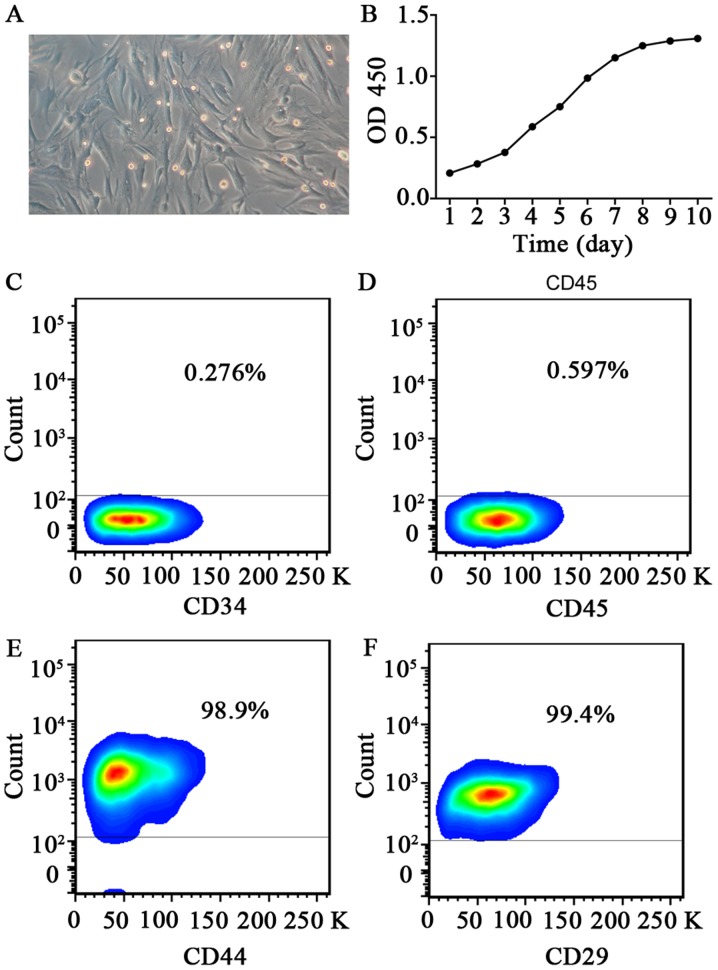

At 24 h after inoculation, cell adhesion was detected from bone marrow cell suspension. After approximately 10 days, colonies of adherent cells started to appear. After passaging, the cells exhibited a long spindle-like appearance, with clones distributed as radial clusters (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Characterization of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow. (A) Images of passage 3 rabbit mesenchymal stem cells showing their typical cobblestone-like morphology. (B) Growth curve of rabbit BMSCs. Flow cytometric analysis of BMSC surface markers (C) CD34, (D) CD45, (E) CD44 and (F) CD29. The results presented are typical of those obtained from three separate experiments. BMSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; OD, optical density.

Growth curve

Cells in primary culture showed a long period of latency, generally lasting about 7 to 8 days, entered the logarithmic growth phase after 10 days, and then reached the growth plateau after 12 days. Analysis of the growth curve suggests that the passaged cells have a quickened rate of cell growth and a shortened incubation period, with an average doubling time of 70 h (Fig. 1B). With the increase in the number of generations, the cell proliferation rate levelled off, and the proliferative capacity declined.

Detection of MSC surface markers

Cells of passage 6 were used for flow cytometric analysis to detect molecular markers on the cell surface. Results show that CD29 and CD44 were expressed on the cell surface, while there was only a very weak expression of CD34 of CD34 or CD45 (Fig. 1C-F). Flow cytometry results also showed that cultured cells were of uniform size, with consistent expression of antigen molecules on the cell surface.

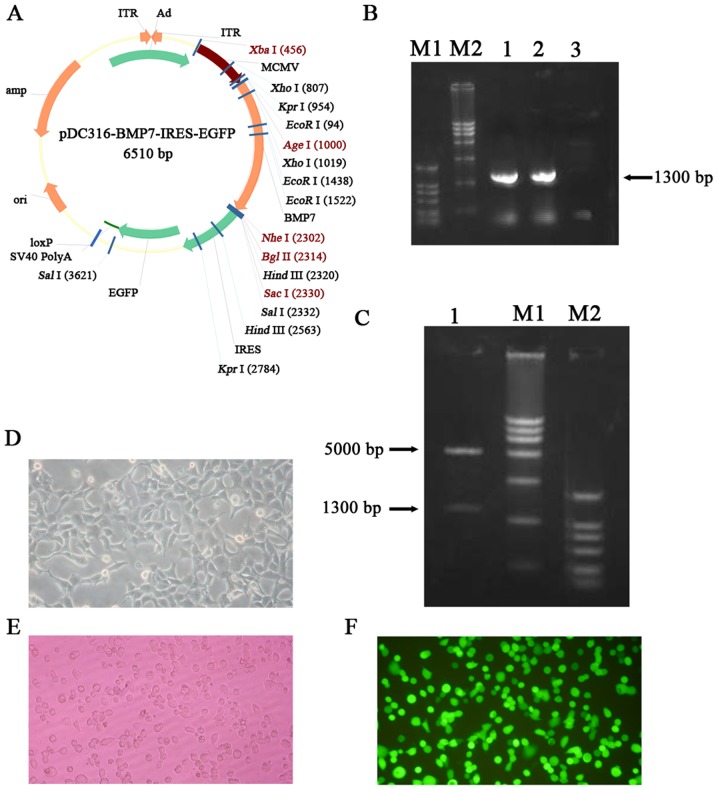

Construction of a recombinant adenovirus vector carrying BMP7

The plasmid structure of pDC316-BMP7-IRES-enhanced GFP (EGFP) is shown in Fig. 2A. According to the results of electrophoresis against DNA markers, the recombinant plasmid had the expected band at the desired size (Fig. 2B). After colony PCR, 3 ml of microbial liquid was used to extract the plasmid which was then cleaved with appropriate restriction enzymes. After digestion, the product was loaded onto a 1% agarose gel for gel electrophoresis to detect a clear band, and the size was consistent with the size of the BMP 7 gene (Fig. 2C). The recombinant plasmid was transformed into 293 cells to generate the recombinant adenovirus. After 8 days, botryoid cells were found and obvious plaques subsequently appeared which can be regarded as indicative of successfully-recombined adenovirus. After 11 days, most of the lesions had formed and cells began to detach from the bottom. Meanwhile, green fluorescence was observed under the fluorescence microscope (Fig. 2D-F). Detection of GFP indicates that virus particles with infection ability have been successfully packaged. The results of MTT assay showed that virus transfection has no obvious effects at MOI=100 on the proliferation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (P>0.05) (Table I).

Figure 2.

Construction of the BMP7 overexpressing adenovirus vector. (A) The plasmid profile of pDC316-BMP7-IRES-EGFP. (B) Gel electrophoresis results show the constructed vectors with the BMP7 gene. 1 and 2: BMP7 PCR amplification using pDC316-BMP7-IRES-EGFP as template. 3: Negative control. M1: DL2000, M2: DL15000. (C) Electrophoretogram of recombinant plasmid containing the BMP7 gene after digestion. 1: AgeI+NheI double digestion of pDC316-BMP7-IRES-EGFP plasmid. M1: DL15000, M2: DL2000. (D) Phase-contrast photography of 293 cells. The images show polymorphic cells with polygonal shapes growing as monolayers. (E) Image of virus-infected 293 cells under a fluorescence microscope. GFP expression can be observed in 293 cells. (F) Image of virus-infected MSCs under a fluorescence microscope. GFP expression can be observed in MSCs. BMP7, bone morphogenetic protein-7; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein.

Table I.

Ad-BMP7-MSCs viability was measured by MTT assay (MOI=100).

| OD450 value (mean ± SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 day | 4 day | 6 day | 8 day | 10 day | 12 day | P-value | |

| Control | 0.360±0.002 | 0.540±0.004 | 0.540±0.003 | 0.620±0.003 | 0.640±0.004 | 0.630±0.002 | |

| Ad-BMP7-MSCs | 0.360±0.003 | 0.550±0.003 | 0.560±0.002 | 0.590±0.002 | 0.640±0.002 | 0.620±0.004 | P>0.05 |

BMP7, bone morphogenetic protein-7; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; SD, standard deviation; OD, optical density.

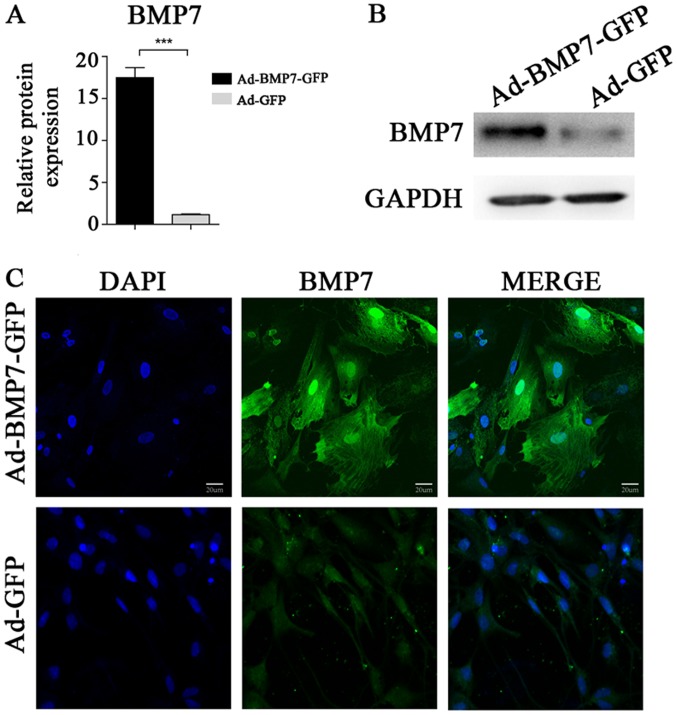

After transfection with Ad-BMP7, BMSCs have high expression of BMP7

RT-PCR was performed to compare the difference in BMP7 gene expression between the Ad-BMP7-GFP-transfected group (experimental group) and the Ad-GFP group (control group). The results showed that the gene expression level of BMP7 in the Ad-BMP7-BMP7-GFP-transfected group was significantly higher than the expression level of the corresponding parental cells (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the results of the immunofluorescence assay showed that in the positive cells of the experimental group, parts of cells with BMP7 expression were green after labelling with the GFP tag, as observed under an inverted fluorescence microscope (Fig. 3C), while no green fluorescence could be seen in the control group. Western blot results showed a positive band of the desired size which is consistent with hBMP7, while the control group did not have any positive bands (Fig. 3B). After transfection, ALP activity was increased because of the expression of BMP7, and induced differentiation of BMSCs in the osteoblastic direction (Table II).

Figure 3.

The expression of BMP7 in BMSCs was detected after transfection with recombinant plasmid. (A) The relative mRNA expression of BMP7 in rabbit BMSCs was analyzed by RT-qPCR after transfection with the BMP7 overexpressing vector or control plasmid. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. ***P<0.001 vs. Ad-GFP group. (B) The expression of BMP7 was analyzed by western blotting. (C) Immunofluorescence shows the expression and distribution of BMP7 in rabbit BMSCs. BMP7, bone morphogenetic protein-7; BMSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Table II.

Alkaline phosphatase activity of Ad-BMP7-MSCs at different time.

| Alkaline phosphatase activity (mean ± SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 day | 4 day | 6 day | 8 day | 10 day | 12 day | P-value | |

| Control | 11.26±0.77 | 12.46±0.55 | 14.61±0.35 | 16.32±0.90 | 19.35±0.42 | 20.92±0.49 | P<0.05 |

| Ad-BMP7-MSCs | 12.27±0.58 | 14.37±0.65 | 22.44±0.64 | 27.05±0.42 | 30.62±0.47 | 34.01±0.32 | |

BMP7, bone morphogenetic protein-7; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; SD, standard deviation.

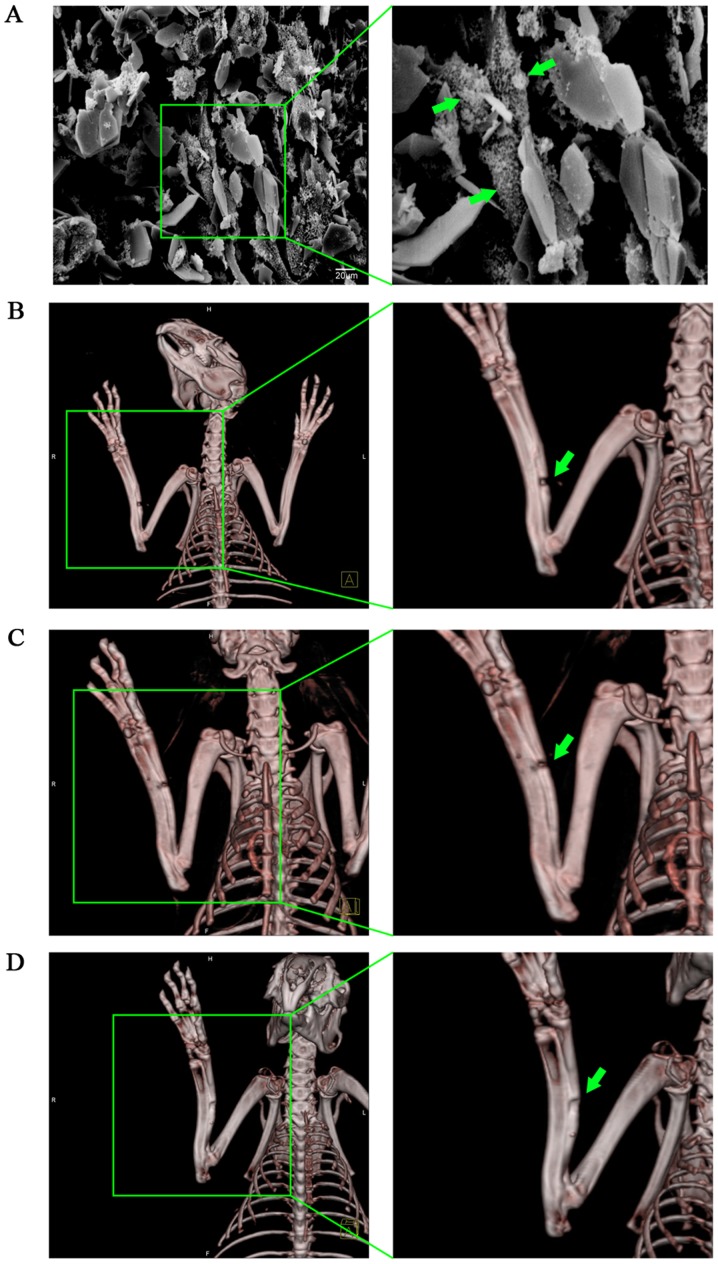

MSCs with high expression of BMP7 combined with an NHAC scaffold can effectively repair a rabbit radius defect

Cells were co-cultured with scaffold materials and after 10 h, cells were observed under SEM (Fig. 4A). The surface of the scaffold material appeared rough, with an average porosity of 70%, tiny holes attached to the microporous wall, and with interpenetrated microspores inside. MSCs on the scaffolds extended pseudopodia, creeping over the pore surface of the material, then the pseudopodia appeared to bulge and touch each other, surrounded by a large amount of extracellular matrix, forming a woven mesh. Most cells were fusiform, triangular or polygonal, with pseudopodia of different lengths.

Figure 4.

The therapeutic effect of BMP7 overexpressing BMSCs on a rabbit model of radius injury. (A) SEM image of NHAC combined with rabbit BMSCs. Green arrows show bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attached to the scaffold. (B) Representative image of the repair of the rabbit radius in the NHAC group. Obvious bone nonunion can be seen, indicated by the green arrows. (C) Representative image of the repair of the rabbit radius in the NHAC plus BMSC group. Bone nonunion can be seen, indicated by the green arrows. (D) Representative image of repair of the rabbit radius in the NHAC plus Ad-BMP7-BMSC group. Porosis can be seen, indicated by the green arrows. BMP7, bone morphogenetic protein-7; BMSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; SEM, scanning electron microscope; NHAC, nano-HAp/Collagen.

Three months later, repair of rabbit radius defects was determined with 3D-CT. The results showed that the speed of repair of the control group which was filled with NHAC alone was slow, with 80% of all subjects having no bone union (Fig. 4B). In the BMSC-loaded NHAC group, although the defect was narrowed, obvious bone nonunion could still be seen, with only 40% of all defects healing completely, although we did not find any cases of bone nonunion (Fig. 4C). In the group filled with BMSCs with high expression of BMP7 combined with NHAC, callus formation could be seen clearly (Fig. 4D). Only one case was still not completely healed, but the bone defect was well repaired. Compared with the other two treatments, NHAC plus Ad-BMP7-BMSCs was more effective in repairing bone defects (P<0.05) (Table III). This suggests that using a BMSC-composite scaffold material transfected with BMP7 for bone defect repair can effectively promote MSC growth and differentiation, and improve bone repair.

Table III.

Incidence of bone defect in different groups.

| Group | Bone defect incidence | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| NHAC | 8/10 | P=0.003 |

| NHAC plus Ad-BMP7-BMSCs | 1/10 | |

| NHAC plus BMSCs | 6/10 | P=0.029 |

| NHAC plus Ad-BMP7-BMSCs | 1/10 |

P-value represents the probality from χ2 for the incidence of bone defect between different groups. BMP7, bone morphogenetic protein-7; BMSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; NHAC, nano-HAp/Collagen.

Discussion

Bone defects and fracture non-union are common problems, affecting many patients every year, and are difficult to heal using current therapies (10–13). For a long time, the accepted treatment for a tissue defect has been tissue transplantation such as autografts or allografts (14–16). Orthopedists often face problems such as a shortage of donor tissue, immune rejection and so on. Such treatment can only be used in a small range of tissue defects and the problem of large tissue defects remains a challenge in the medical field. Here we have devised a strategy to treat such defects using ex vivo gene therapy. Unlike regular in vivo gene therapy, this strategy is MSC-based and has a number of advantages including continuous BMP7 protein secretion but also enables precise implantation into target sites, and easy preparation of numbers of transduced cells.

Using different inducers and methods such as dexamethasone, vitamin C, vitamin D, BMPs, TGF-β, FGF, or insulin, can induce MSCs to differentiate into different lineages such as osteoblasts, chondrocytes, fibroblasts, myoblasts and so on (9,17–22). The direction has been set but differentiated cells can reverse the differentiation induced under certain conditions. Cultured BMSCs retain their normal phenotype and telomerase activity up to passage 12 and still maintain their potential for osteogenic differentiation up to passage 15, and therefore are considered to be the ideal seed cells (23–25). Preliminary studies of their biological characteristics have been performed, which provide the experimental basis for further research into BMSCs (26–28). In view of the above advantages, BMSCs have gradually been replacing osteoblasts as the seed cells in subsequent research. We combined the density gradient separation and sidewall separation methods, using the growth characteristics of MSCs and the differences of digestion time from other cells in the process of passage, to purify the cells gradually. In this experiment, like other cells in vitro, the cultured bone marrow stromal cells also experienced three stages of growth, the lag phase, logarithmic phase and growth plateau. BMSCs have strong proliferative ability in vitro, with an average doubling time of approximately 70 h. However, cell proliferation ability decreased with the increasing number of passages.

As another element in tissue engineering, growth factors are peptides that transmit information between cells and play an important role in controlling cell growth. However, due to the factors' intrinsic characteristics, they are easily affected by external conditions, such as temperature, pH and organic reagents, and vulnerable to hemodilution, enzymatic hydrolysis, release time and concentration, making it difficult to control their use in defects (29–31). In recent years, the development of genetic engineering has led to developments in bone tissue engineering, since genetic engineering provides a good alternative method for solving the above problems. It can be used to achieve sustained or slow-release of gene product and multiple genes can be transduced and regulated. An endogenously-synthesized factor may have much stronger biological activities than an exogenous recombinant factor. This combination of genetic engineering technology and tissue engineering is known as ‘gene-enhanced tissue engineering’.

Currently, growth factors such as BMP, PDGF, FGF and IGF, which can promote tissue differentiation, are used for tissue engineering (32–34). Results of animal experiments and clinical studies have shown that BMP family proteins can obviously promote the growth and healing of bone tissue (35–37). Among the BMP family members, BMP-2 has the strongest bone induction activity, and it can induce mesenchymal cells to irreversibly differentiate into bone and cartilage (38). However, BMP-2 only induces bone formation, and has no further effect on promoting proliferation for the differentiation of osteoblasts (39). BMP7 has a strong ability to induce bone as well as maintaining the phenotype of cartilage cells and promoting cell proliferation and extracellular matrix proteoglycan and collagen type II synthesis (40). The main biological function of BMP7 is to induce mesenchymal cells to differentiate into osteoblasts (41,42). Recombinant human BMP7 shows efficient bone induction activity both in vitro and in vivo, promoting cartilage proteoglycan expression and articular cartilage defect repair (43). Consequently expression of the BMP7 gene will be more conducive to cell differentiation from BMSCs to osteoblasts and to cell proliferation.

Using gene transfection technology to strengthen or transform the function of seed cells is a hot topic in tissue engineering. It is considered that using the method of gene transfection, rather than direct use of recombinant proteins, has more advantages. This is because it can achieve a more ‘natural’ kind of action with long-term, high efficiency and localized effects, and avoid the excessive reaction and systemic side effects which may occur with the direct application of growth factors. Using this strategy, we were able to not only obtain seed cells with strong physiological functions, but also make the seed cells express the target protein needed for tissue construction. Currently, in genetic engineering, carriers can be divided into plasmids, bacteria, phagocytosed particles, artificial chromosomes, viruses and so on, according to the basic elements of the different sources. Adenovirus vectors (Adv) are one of the most promising and widely-used carriers in genetically-engineered tissue engineering (44–46). Compared with other gene carriers, they have many advantages, such as the wide range of transfected cell types and their ability to efficiently infect cells both at dividing and non-dividing stages. Our data show that MSCs can be easily transduced with Adv-hBMP7. In our study, the transduction efficiency of our generated Adv-hBMP7 can reach 90–100%. It cannot replicate in the host, has good security, no carcinogenicity or viral genome drifts outside the host genome, and no risk of insertion mutation. Gene transfection can generally maintain expression in the body for more than 6 weeks.

Our data suggest that MSCs may perform a role as delivery vehicles as well as having osteogenic potential themselves. Based on our previous experiment, which provided preliminary data and defined the best conditions and the influence of adenovirus-transfected BMSCS, we used the application package to harvest the recombinant adenovirus from BMSCs transfected with Adv-hBMP7 in vitro. Using RT-PCR to detect the expression of hBMP7, we found that the transfection group expressed significantly higher mRNA levels. The results of immunofluorescence staining and western blotting showed that the protein is expressed successfully. Therefore, by using BMSCs with enhanced BMP7 expression combined with a suitable scaffold, we achieved very good repair of a rabbit radial defect, demonstrating the feasibility of the application of this method to repair bone defects in the clinic. Our work lays the foundation for clinical application in the future.

References

- 1.Vander Have KL, Hensinger RN, Caird M, Johnston C, Farley FA. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:228–236. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCollum GA, Myerson MS, Jonck J. Managing the cystic osteochondral defect: Allograft or autograft. Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18:113–133. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chahal J, Gross AE, Gross C, Mall N, Dwyer T, Chahal A, Whelan DB, Cole BJ. Outcomes of osteochondral allograft transplantation in the knee. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:575–588. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espana EM, Shah S, Santhiago MR, Singh AD. Graft versus host disease: Clinical evaluation, diagnosis and management. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:1257–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2301-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tate Knothe ML. Top down and bottom up engineering of bone. J Biomech. 2011;44:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marolt D, Knezevic M, Novakovic GV. Bone tissue engineering with human stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;1:10. doi: 10.1186/scrt10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fröhlich M, Grayson WL, Wan LQ, Marolt D, Drobnic M, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Tissue engineered bone grafts: Biological requirements, tissue culture and clinical relevance. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2008;3:254–264. doi: 10.2174/157488808786733962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu H, Yang F, Tang B, Li XM, Chu YN, Liu YL, Wang SG, Wu DC, Zhang Y. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuated PLGA-induced inflammatory responses by inhibiting host DC maturation and function. Biomaterials. 2015;53:688–698. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun H, Yang HL. Calcium phosphate scaffolds combined with bone morphogenetic proteins or mesenchymal stem cells in bone tissue engineering. Chin Med J (Engl) 2015;128:1121–1127. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.155121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqui NA, Owen JM. Clinical advances in bone regeneration. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;8:192–200. doi: 10.2174/1574888X11308030003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher DM, Wong JM, Crowley C, Khan WS. Preclinical and clinical studies on the use of growth factors for bone repair: A systematic review. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;8:260–268. doi: 10.2174/1574888X11308030011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mills LA, Simpson AH. In vivo models of bone repair. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:865–874. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B7.27370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shekkeris AS, Jaiswal PK, Khan WS. Clinical applications of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of fracture non-union and bone defects. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;7:127–133. doi: 10.2174/157488812799218956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papakostidis C, Bhandari M, Giannoudis PV. Distraction osteogenesis in the treatment of long bone defects of the lower limbs: Effectiveness, complications and clinical results; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:1673–1680. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B12.32385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berner A, Reichert JC, Müller MB, Zellner J, Pfeifer C, Dienstknecht T, Nerlich M, Sommerville S, Dickinson IC, Schütz MA, Füchtmeier B. Treatment of long bone defects and non-unions: From research to clinical practice. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:501–519. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boos AM, Arkudas A, Kneser U, Horch RE, Beier JP. Bone tissue engineering for bone defect therapy. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2010;42:360–368. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1261964. (In German) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Contador D, Ezquer F, Espinosa M, Arango-Rodriguez M, Puebla C, Sobrevia L, Conget P. Dexamethasone and rosiglitazone are sufficient and necessary for producing functional adipocytes from mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2015;240:1235–1246. doi: 10.1177/1535370214566565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castro FO, Torres A, Cabezas J, Rodríguez-Alvarez L. Combined use of platelet rich plasma and vitamin C positively affects differentiation in vitro to mesodermal lineage of adult adipose equine mesenchymal stem cells. Res Vet Sci. 2014;96:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang HT, Zha ZG, Cao JH, Liang ZJ, Wu H, He MT, Zang X, Yao P, Zhang JQ. Apigenin accelerates lipopolysaccharide induced apoptosis in mesenchymal stem cells through suppressing vitamin D receptor expression. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124:3537–3545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Y, Peng Y, Gao D, Feng C, Yuan X, Li H, Wang Y, Yang L, Huang S, Fu X. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress fibroblast proliferation and reduce skin fibrosis through a TGF-β3-dependent activation. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:50–62. doi: 10.1177/1534734614568373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagmann S, Moradi B, Frank S, Dreher T, Kämmerer PW, Richter W, Gotterbarm T. FGF-2 addition during expansion of human bone marrow-derived stromal cells alters MSC surface marker distribution and chondrogenic differentiation potential. Cell Prolif. 2013;46:396–407. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thakkar UG, Trivedi HL, Vanikar AV, Dave SD. Insulin-secreting adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells with bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells from autologous and allogenic sources for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.03.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng YH, Xiong W, Su K, Kuang SJ, Zhang ZG. Multilineage differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Exp Ther Med. 2013;5:1576–1580. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbas Mashhadi F, Fallahi Sichani H, Khoshzaban A, Mahdavi N, Bagheri SS. Expression of odontogenic genes in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cell J. 2013;15:136–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song K, Huang M, Shi Q, Du T, Cao Y. Cultivation and identification of rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:755–760. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, Zhu L, Li F, Wang J, Wan H, Pan Y. Bone marrow stromal cells as a therapeutic treatment for ischemic stroke. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30:524–534. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1431-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hang HL, Xia Q. Role of BMSCs in liver regeneration and metastasis after hepatectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:126–132. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Liu X, Cao Y. Progress of methods of inducing bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into chondrocytes in vitro. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011;25:618–623. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishero BA, Kohli N, Das A, Christophel JJ, Cui Q. Current concepts of bone tissue engineering for craniofacial bone defect repair. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2015;8:23–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma AK, Cheng EY. Growth factor and small molecule influence on urological tissue regeneration utilizing cell seeded scaffolds. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;82–83:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gothard D, Smith EL, Kanczler JM, Rashidi H, Qutachi O, Henstock J, Rotherham M, El Haj A, Shakesheff KM, Oreffo RO. Tissue engineered bone using select growth factors: A comprehensive review of animal studies and clinical translation studies in man. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;28:166–208. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v028a13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto M, Hokugo A, Takahashi Y, Nakano T, Hiraoka M, Tabata Y. Combination of BMP-2-releasing gelatin/β-TCP sponges with autologous bone marrow for bone regeneration of X-ray-irradiated rabbit ulnar defects. Biomaterials. 2015;56:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khoshkam V, Chan HL, Lin GH, Mailoa J, Giannobile WV, Wang HL, Oh TJ. Outcomes of regenerative treatment with rhPDGF-BB and rhFGF-2 for periodontal intra-bony defects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:272–280. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullen LM, Best SM, Ghose S, Wardale J, Rushton N, Cameron RE. Bioactive IGF-1 release from collagen-GAG scaffold to enhance cartilage repair in vitro. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2015;26:5325. doi: 10.1007/s10856-014-5325-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Li Y, Han R, He C, Wang G, Wang J, Zheng J, Pei M, Wei L. Demineralized bone matrix combined bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, bone morphogenetic protein-2 and transforming growth factor-β3 gene promoted pig cartilage defect repair. PLoS One. 2014;9:e116061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang DH, Lee DW, Kwon YD, Kim HJ, Chun HJ, Jang JW, Khang G. Surface modification of titanium with hydroxyapatite-heparin-BMP-2 enhances the efficacy of bone formation and osseointegration in vitro and in vivo. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2015;9:1067–1077. doi: 10.1002/term.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noh SS, Bhang SH, La WG, Lee S, Shin JY, Ma YJ, Jang HK, Kang S, Jin M, Park J, Kim BS. A dual delivery of substance P and bone morphogenetic protein-2 for mesenchymal stem cell recruitment and bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:1275–1287. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo P, Shi ZL, Liu A, Lin T, Bi F, Shi M, Yan SG. Effects of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein on bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Orthop Surg. 2014;6:280–287. doi: 10.1111/os.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y, Roohani-Esfahani SI, Lu Z, Zreiqat H, Dunstan CR. Zirconium ions up-regulate the BMP/SMAD signaling pathway and promote the proliferation and differentiation of human osteoblasts. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0113426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abula K, Muneta T, Miyatake K, Yamada J, Matsukura Y, Inoue M, Sekiya I, Graf D, Economides AN, Rosen V, Tsuji K. Elimination of BMP7 from the developing limb mesenchyme leads to articular cartilage degeneration and synovial inflammation with increased age. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1240–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos A, Bakker AD, Willems HM, Bravenboer N, Bronckers AL, Klein-Nulend J. Mechanical loading stimulates BMP7, but not BMP2, production by osteocytes. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89:318–326. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9521-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ren Y, Han C, Jia Y, Yin H, Li S. Expression of human bone morphogenetic protein 7 gene in adipose-derived stem cells and its effects on osteogenic phenotype. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011;25:848–853. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stöve J, Schneider-Wald B, Scharf HP, Schwarz ML. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 (bmp-7) stimulates proteoglycan synthesis in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes in vitro. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:639–643. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, Godbey WT. Viral vectors for gene delivery in tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:515–534. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Partridge KA, Oreffo RO. Gene delivery in bone tissue engineering: Progress and prospects using viral and nonviral strategies. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:295–307. doi: 10.1089/107632704322791934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warnock JN, Daigre C, Al-Rubeai M. Introduction to viral vectors. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;737:1–25. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-095-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]