Abstract

Background

The association between corticosteroid use and intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired weakness remains unclear. We evaluated the relationship between corticosteroid use and ICU-acquired weakness in critically ill adult patients.

Methods

The PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature databases were searched from database inception until October 10, 2017. Two authors independently screened the titles/abstracts and reviewed full-text articles. Randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies evaluating the association between corticosteroids and ICU-acquired weakness in adult ICU patients were selected. Data extraction from the included studies was accomplished by two independent reviewers. Meta-analysis was performed using Stata version 12.0. The results were analyzed using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Data were pooled using a random effects model, and heterogeneity was evaluated using the χ2 and I2 statistics. Publication bias was qualitatively analyzed with funnel plots, and quantitatively analyzed with Begg’s test and Egger’s test.

Results

One randomized controlled trial and 17 prospective cohort studies were included in this review. After a meta-analysis, the effect sizes of the included studies indicated a statistically significant association between corticosteroid use and ICU-acquired weakness (OR 1.84; 95% CI 1.26–2.67; I2 = 67.2%). Subgroup analyses suggested a significant association between corticosteroid use and studies limited to patients with clinical weakness (OR 2.06; 95% CI 1.27–3.33; I2 = 60.6%), patients with mechanical ventilation (OR 2.00; 95% CI 1.23–3.27; I2 = 66.0%), and a large sample size (OR 1.61; 95% CI 1.02–2.53; I2 = 74.9%), and not studies limited to patients with abnormal electrophysiology (OR 1.65; 95% CI 0.92–2.95; I2 = 70.6%) or patients with sepsis (OR 1.96; 95% CI 0.61–6.30; I2 = 80.8%); however, statistical heterogeneity was obvious. No significant publication biases were found in the review. The overall quality of the evidence was high for the randomized controlled trial and very low for the included prospective cohort studies.

Conclusions

The review suggested a significant association between corticosteroid use and ICU-acquired weakness. Thus, exposure to corticosteroids should be limited, or the administration time should be shortened in clinical practice to reduce the risk of ICU-acquired weakness.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13054-018-2111-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Intensive care unit, ICU-acquired weakness, Corticosteroids, Corticosteroid use, Corticosteroid therapy, Systematic review

Background

Intensive care unit-acquired weakness (ICUAW) is a common neuromuscular complication of critical illness. ICUAW is associated with delayed weaning, longer intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stays, increased healthcare-related costs, and higher ICU-related and hospitalization-related mortality [1–3]. Corticosteroid therapy is still the key treatment and recommendation for specific critically ill patients [4, 5] because of its strong anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects. Corticosteroid therapy results in a shorter duration of mechanical ventilation, a faster resolution of shock [6], more vasopressor-free and organ-failure-free days [7], and lower mortality [7–9] in patients with refractory septic shock. For patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), corticosteroid therapy may also improve hypoxemia [10] and reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation [11, 12] and the ICU hospitalization period [13]. ICUAW occurs commonly in critically ill patients, but the role of corticosteroid therapy in ICUAW remains controversial. Researchers and authors have raised significant concerns regarding the side effects of corticosteroids in terms of ICUAW development and have attempted to examine the relationship. Some clinical studies have indicated that corticosteroids may contribute to developing ICUAW, yet others have demonstrated decreasing odds of developing ICUAW. However, other studies could not identify the effect of corticosteroids on ICUAW. In this review, we provide a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective cohort studies to assess the association between corticosteroid use and ICUAW development.

No universal recommendation or consensus on the definition or classification of the disease exists; after consulting the literature [14], the relatively broad term “intensive care unit-acquired weakness (ICUAW)” was selected for use in this review. Although there was no diagnostic gold standard for ICUAW, three diagnostic methods were recommended to identify ICUAW [14, 15]: manual muscle testing (Medical Research Council (MRC) weakness scale), electrophysiological studies, and the histopathology of muscle or nerve tissue. However, muscle or nerve tissue biopsy was rarely used in the studies. This review explores the adverse effect of corticosteroids on ICUAW development, from patients with clinical weakness to patients with clinically undetectable neuromuscular dysfunction.

Methods

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement [16].

Search strategy

A systematic literature review of all of the pertinent English language studies was undertaken in the following databases from inception through October 10, 2017: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature. The search terms were used for PubMed (Additional file 1) and the other databases. In addition, a manual search of references cited by the selected articles and relevant review articles was performed to identify other eligible studies.

Selection criteria

All studies satisfying the following criteria were included: age > 18; RCTs and prospective cohort studies; diagnoses of ICUAW confirmed using manual muscle testing (MRC weakness scale) or diagnostic tests (electrophysiological studies, histopathology of muscle or nerve tissue); and studies that evaluated the use of corticosteroids and incidence of ICUAW. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with primary myopathies (e.g., idiopathic inflammatory myopathies) or polyneuropathies (e.g., myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barré syndrome); and studies with insufficient data reported.

Study selection and data abstraction

Two reviewers (TY and ZqL) independently reviewed and selected studies based on the inclusion criteria. Data were extracted independently by each reviewer using a standardized data collection form. The following data were collected from each study: author information, publication year, study design, study location, inclusion and exclusion criteria, tools of neuromuscular evaluation, number of participants, ICUAW incidence, and number of ICUAW patients who were given and not given corticosteroids. Disagreements in study selection or data extraction were resolved by either consensus or a third-party decision. Authors of the included studies were contacted when data required clarification.

Study quality assessment

Two reviewers (TY and ZqL) independently assessed the methodological quality of each study using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale [17] for prospective studies and the Cochrane Collaboration tool [17] for RCTs.

Data analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), and the results were analyzed using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Data were pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed using the χ2 statistic with P ≤ 0.1 considered statistically significant. The impact of statistical heterogeneity on the study results was estimated by calculating the I2 statistic. Values of the I2 statistic above 50% were regarded as a cutoff point for considerable heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses examined: RCT and prospective cohort studies; studies using clinical muscle testing and electrophysiology as a diagnostic method; studies using mechanical and nonmechanical ventilation as inclusion criteria; studies using sepsis and nonsepsis as inclusion criteria; and studies with relatively large (n ≥ 100) and small (n < 100) sample sizes. Publication bias was examined using funnel plots for qualitative assessment, using Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger’s linear regression test for quantitative assessment.

Summary of findings

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) assessment method was employed to determine the quality of evidence in our review associated with the main outcome (incidence of ICUAW). Two reviewers (TY and ZqL) independently graded the evidence prior to agreement and created the ‘Summary of findings’ table using GRADE software [17]. We considered risk of bias, directness of evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect, and risk of publication bias as the factors influencing assessment of the review.

Results

Study search and selection

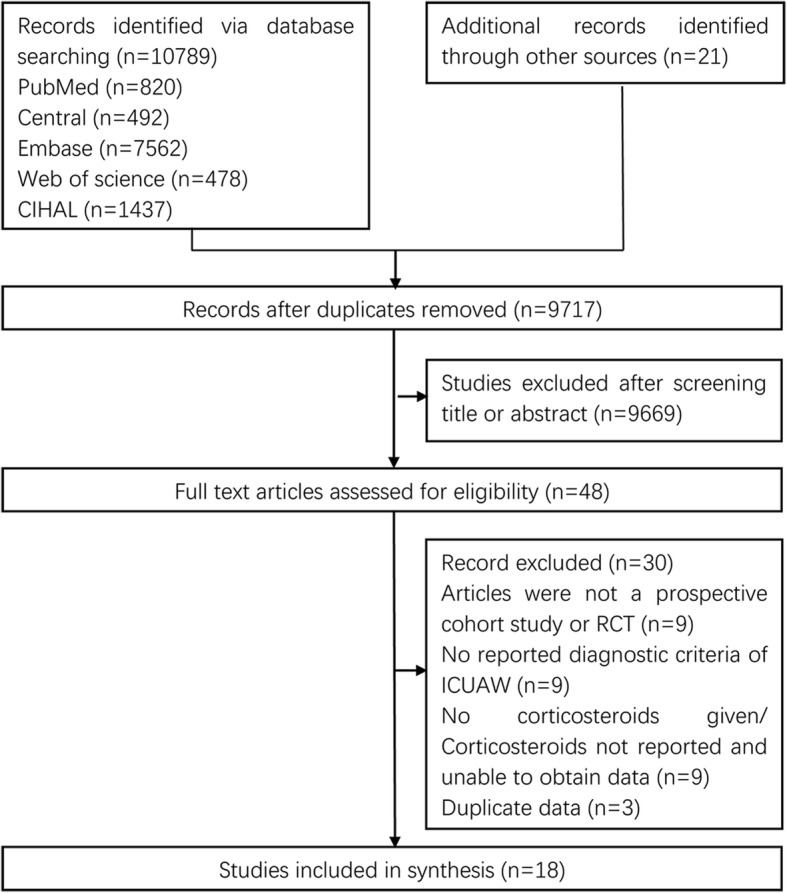

The electronic search yielded a total of 10,789 citations (Fig. 1). Twenty-one additional articles were identified through other sources. After screening the titles and abstracts, 48 articles were selected for full-text review. Thirty articles did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded, and therefore 18 studies were included in this review.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process. CIHAL Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature, ICUAW intensive care unit-acquired weakness, RCT randomized controlled trial

Study characteristics and quality

The characteristics of the included studies in this systematic review are presented in Table 1. They included one RCT [18] and 17 prospective cohort studies [1, 19–34]. The number of participants in each study ranged from 20 to 412. The studies were carried out in the United States [21, 27], India [19], Vietnam [1], Belgium [28], the Netherlands [20, 33], Germany [18, 25], Switzerland [24], France [23, 29, 31], Spain [32], Greece [22, 26], Canada [30], and England [34]. Diagnosis of ICUAW was accomplished in eight studies [18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 31] using the MRC scale and in 10 studies [1, 19, 22, 25, 28–30, 32–34] using electrophysiological evaluation. Participant inclusion criteria included mechanical ventilation in 12 studies [20, 21, 23–25, 27–29, 31–34], systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis in five studies [18, 19, 24, 30, 32], and length of ICU stay in four studies [1, 22, 26, 34]. ICU mortality differed across the studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the selected studies

| Study | Study design | Country | Setting | Population | n | Examination | ICUAW | Use of CS a | ICU mortality (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keh et al., 2016 [18] | RCT | Germany | MSICU | Severe sepsis | 375 | Clinical | 82 | 46 vs 140 | NR |

| Gupta and Mishra, 2016 [19] | Prospective cohort | India | MICU | Sepsis | 100 | EMG | 37 | 26 vs 12 | NR |

| Nguyen The and Nguyen Huu, 2015 [1] | Prospective cohort | Vietnam | MSICU | ICU LOS ≥ 10 days | 133 | EMG | 73 | 29 vs 18 | 49% vs 30% |

| Patel et al., 2014 [21] | Prospective cohort | America | MICU | MV ≥ 24 h | 104 | Clinical | 41 | 35 vs 44 | NR |

| Wieske et al., 2014 [20] | Prospective cohort | Netherlands | MSICU | MV ≥ 2 days | 212 | Clinical | 103 | 81 vs 63 | 34% vs 9% |

| Anastasopoulos et al., 2011 [22] | Prospective cohort | Greece | MSICU | ICU LOS ≥ 7 days | 190 | EMG | 40 | 28 vs 102 | 32.5% vs NR |

| Sharshar et al., 2010 [23] | Prospective cohort | France | MICU, SICU | MV > 7 days | 86 | Clinical | 39 | 29 vs 22 | NR |

| Brunello et al., 2010 [24] | Prospective cohort | Switzerland | MSICU | MV > 48 h and SIRS | 39 | Clinical | 13 | 4 vs 0 | 62% vs 23% |

| Weber-Carstens et al., 2009 [25] | Prospective cohort | Germany | SICU | MV and SAPS II ≥ 20 | 56 | EMG | 34 | 21 vs 5 | NR |

| Nanas et al., 2008 [26] | Prospective cohort | Greece | MSICU | LOS > 10 days | 185 | Clinical | 44 | 7 vs 31 | 36% vs 20% |

| Ali et al., 2008 [27] | Prospective cohort | America | MICU, NICU | MV > 5days | 136 | Clinical | 35 | 16 vs 42 | 31.4% vs 6% |

| Hermans et al., 2007 [28] | Prospective cohort | Belgium | MICU | MV > 7 days | 412 | EMG | 188 | 123 vs 156 | NR |

| Khan et al., 2006 [30] | Prospective cohort | Canada | MSICU | Sepsis | 20 | EMG | 10 | 4 vs 4 | 55% vs 0% |

| Lefaucheur et al., 2006 [29] | Prospective cohort | France | MICU | MV > 7 days, diffuse weakness | 30 | EMG | 26 | 15 vs 1 | NR |

| De Jonghe et al., 2002 [31] | Prospective cohort | France | MICU, SICU | MV > 7 days and awake | 95 | Clinical | 24 | 13 vs 13 | 17% vs 6% |

| de Letter et al., 2001 [33] | Prospective cohort | Netherlands | MSICU | MV ≥ 4 days | 97 | EMG | 34 | 9 vs 18 | NR |

| Garnacho-Montero et al., 2001 [32] | Prospective cohort | Spain | MSICU | MV > 10 days and sepsis with MOF | 73 | EMG | 50 | 7 vs 4 | 66% vs 52% |

| Coakley et al., 1998 [34] | Prospective cohort | England | MSICU | MV and ICU LOS > 7 days | 44 | EMG | 37 | 11 vs 2 | NR |

ICUAW intensive care unit-acquired weakness, CS corticosteroids, ICU intensive care unit, RCT randomized controlled trial, MICU medical ICU, MSICU medical–surgical ICU, SICU surgical ICU, NR not reported, EMG electromyography, LOS length of stay, MV mechanical ventilation, SIRS systemic inflammatory response syndrome, SAPS Simplified Acute Physiology Score, MOF multiple organ failure

aComparison between ICUAW and no ICUAW

The methodological quality assessment of the included reports is presented in Table 2. The risk of bias of the randomized trial was low, and the overall risk of bias of the prospective studies was acceptable in general. Three of the 17 observational studies made statistical comparisons with multivariable regression analysis for corticosteroids, and therefore the other 14 studies received no scores for comparability. Four studies did not report whether the assessments were independently blinded for clinicians or physical therapists.

Table 2.

Methodology and reporting assessment

| Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias | |||||||||

| Study | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other potential threats to validity | Risk of bias | ||

| Keh et al., 2016 [18] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Low | ||

| Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale for cohort studies | |||||||||

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Score | |||||

| Exposed representative? | Nonexposed representative? | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome of interest not present at start | Assessment of outcome | Adequate duration of follow-up | Completeness of follow-up | |||

| Gupta and Mishra, 2016 [19] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Nguyen The and Nguyen Huu, 2015 [1] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Wieskeet al., 2014 [20] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Patel et al., 2014 [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Anastasopoulos et al., 2011 [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Brunello et al., 2010 [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | N | Y | N | 7 |

| Sharshar et al., 2010 [23] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Weber-Carstens et al., 2009 [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Nanas et al., 2008 [26] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Ali et al., 2008 [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Hermans et al., 2007 [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Khan et al., 2006 [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | N | 6 |

| Lefaucheur et al., 2006 [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| De Jonghe et al., 2002 [31] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y, Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| de Letter et al., 2001 [33] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Garnacho-Montero et al., 2001 [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Coakley et al., 1998 [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N, N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

Y criteria satisfied, N criteria not satisfied

Corticosteroids and ICUAW

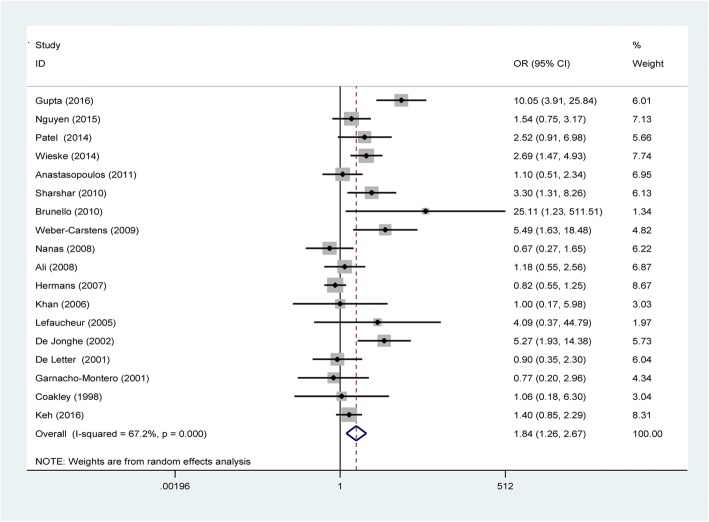

When the 18 studies were pooled together (Fig. 2), the effect size analysis (OR 1.84; 95% CI 1.26–2.67; P = 0.002) indicated that the use of corticosteroids was significantly associated with increased odds of developing ICUAW. Data were pooled using a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.38; χ2 = 51.87, df = 17 (P < 0.001); I2 = 67.2%). The overall incidence of ICUAW was 43% in the corticosteroid group versus 34% in the control group.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of associations between corticosteroid use and ICUAW. CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio

Subgroup analyses

RCTs versus prospective cohort studies

The subgroup analyses are presented in Table 3. One RCT revealed no significant association between corticosteroids and ICUAW (OR 1.40; 95% CI 0.85–2.29; P = 0.184), and the GRADE quality of evidence was high for this trial (Additional file 2). The meta-analysis of 17 prospective cohort studies (OR 1.90; 95% CI 1.25–2.89; P = 0.003) showed a significant association with a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.46; χ2 = 51.66, df = 16 (P < 0.001); I2 = 69.0%). The incidence of ICUAW was 46% in the corticosteroid group versus 36% in the control group; however, the GRADE quality of evidence was very low (Additional file 2). There was no significantly statistical heterogeneity found between the subgroups based on a test of interaction (P = 0.35).

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses

| Analysis | Study | n | I2 (%) | Ph | OR | 95% CI | Pe | Pi | Incidence corticosteroid (%) | Incidence control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study type | ||||||||||

| RCT | [18] | 375 | 1.40 | 0.85–2.29 | 0.184 | 25 | 19 | |||

| Prospective cohort studies | [1, 19–34] | 2012 | 69.0 | < 0.001 | 1.90 | 1.25–2.89 | 0.003 | 0.35 | 46 | 36 |

| Diagnostic method | ||||||||||

| Clinical assessment | [18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 31] | 1232 | 60.6 | 0.013 | 2.06 | 1.27–3.33 | 0.003 | 39 | 23 | |

| Electrophysiology | [1, 19, 22, 25, 28–30, 32–34] | 1155 | 70.6 | < 0.001 | 1.65 | 0.92–2.95 | 0.093 | 0.56 | 46 | 46 |

| Inclusion criterion | ||||||||||

| Sepsis | [18, 19, 30, 32] | 568 | 80.8 | 0.001 | 1.96 | 0.61–6.30 | 0.260 | 34 | 30 | |

| Nonsepsis | [1, 20–29, 31, 33, 34] | 1819 | 63.0 | 0.001 | 1.77 | 1.18–2.64 | 0.006 | 0.87 | 45 | 35 |

| MV | [20, 21, 23–25, 27–29, 31–34] | 1384 | 66.0 | 0.001 | 2.00 | 1.23–3.27 | 0.006 | 50 | 40 | |

| Non-MV | [1, 18, 19, 22, 26, 30] | 1003 | 74.4 | 0.002 | 1.61 | 0.83–3.13 | 0.161 | 0.61 | 31 | 26 |

| Sample size | ||||||||||

| n ≥ 100 | [1, 18–22, 26–28] | 1847 | 74.9 | < 0.001 | 1.62 | 1.02–2.53 | 0.042 | 39 | 30 | |

| n < 100 | [23–25, 29–34] | 540 | 49.3 | 0.046 | 2.32 | 1.21–4.42 | 0.011 | 0.36 | 62 | 43 |

I2 I-squared statistic test for heterogeneity, Ph P value for test of heterogeneity, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, Pe P value for the effect estimate for each subgroup, Pi P value for interaction tests of heterogeneity between subgroups, RCT randomized controlled trial, MV mechanical ventilation

Clinical assessment versus electrophysiology

Eight studies [18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 31] examined the association between the use of corticosteroids and patients with clinical weakness and demonstrated an incidence of 39% in the corticosteroid group and 23% in the control group. The overall effect size (OR 2.06; 95% CI 1.27–3.33; P = 0.003) demonstrated a significant association with a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.27; χ2 = 17.78, df = 7 (P = 0.013); I2 = 60.6%). Ten observational studies [1, 19, 22, 25, 28–30, 32–34] reported an association between the use of corticosteroids and patients with abnormal electrophysiology and showed an event rate of 46% in the corticosteroid group and 46% in the control group. The pooled effect size (OR 1.65; 95% CI 0.92–2.95; P = 0.093) revealed no significant association. Data were pooled using a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.53; χ2 = 30.63, df = 9 (P < 0.001); I2 = 70.6%). No statistically significant heterogeneity between the subgroups was found based on a test of the interaction (P = 0.56).

Sepsis versus nonsepsis

Four trials [18, 19, 30, 32] with sepsis as the inclusion criterion reported an association between the use of corticosteroids and ICUAW, and demonstrated an incidence of 34% in the corticosteroid group and 30% in the control group. The pooled effect size (OR 1.96; 95% CI 0.61–6.30; P = 0.260) revealed no significant association. Data were pooled using a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 1.08; χ2 = 15.65, df = 3 (P = 0.001); I2 = 80.8%). The remaining 14 studies [1, 20–29, 31, 33, 34] without sepsis as an inclusion criterion showed an unadjusted event rate in the corticosteroid group of 45% versus 35% in the control group. The pooled effect size (OR 1.77; 95% CI 1.18–2.64; P = 0.006) demonstrated a significant association with a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.32; χ2 = 35.18, df = 13 (P = 0.001); I2 = 63.0%). No statistically significant heterogeneity between the subgroups was found based on a test of the interaction (P = 0.87).

Mechanical ventilation versus nonmechanical ventilation

Twelve observational studies [20, 21, 23–25, 27–29, 31–34] using mechanical ventilation as an inclusion criterion examined the association between the use of corticosteroids and ICUAW, and showed an event rate of 50% in the corticosteroid group and 40% in the control group. The overall effect size (OR 2.00; 95% CI 1.23–3.27; P = 0.006) demonstrated a significant association with a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.42; χ2 = 32.32, df = 11 (P = 0.001); I2 = 66.0%). The remaining six studies [1, 18, 19, 22, 26, 30] without mechanical ventilation as an inclusion criterion showed an unadjusted event rate in the corticosteroid group of 31% versus 26% in the control group. The pooled effect size (OR 1.61; 95% CI 0.83–3.13; P = 0.161) revealed no significant association with a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.48; χ2 = 19.54, df = 5 (P = 0.002); I2 = 74.4%). No statistically significant heterogeneity between the subgroups was found based on a test of the interaction (P = 0.61).

Sample sizes (n ≥ 100 versus n < 100)

After the results of the nine studies [1, 18–22, 26–28] with sample sizes greater than 100 were incorporated, the pooled effect size (OR 1.62; 95% CI 1.02–2.53; P = 0.042) still demonstrated a significant association between corticosteroid use and ICUAW with a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.35; χ2 = 31.92, df = 8 (P < 0.001); I2 = 74.9%), with an event rate of 39% in the corticosteroid group and 30% in the control group. The remaining nine studies [23–25, 29–34] with relatively small sample sizes (n < 100) showed an unadjusted event rate in the corticosteroid group of 62% versus 43% in the control group. The pooled effect size (OR 2.32; 95% CI 1.21–4.42; P = 0.011) demonstrated a significant association with a random effects model considering the observed heterogeneity (τ2 = 0.44; χ2 = 15.77, df = 8 (P = 0.046); I2 = 49.3%). No statistically significant heterogeneity between the subgroups was found based on a test of the interaction (P = 0.36).

Heterogeneity

Methodological heterogeneity

Methodological heterogeneity was found among the included studies. Two study design types were utilized among the included studies, and two diagnostic methods were used in the included studies. Sample sizes differed across the included studies; small and large studies were delineated by a cutoff value of 100 subjects. This methodological heterogeneity led to three comparisons in the review: RCTs versus prospective cohort studies, clinical assessment versus electrophysiology, and sample size analysis (n ≥ 100 versus n < 100).

Clinical heterogeneity

Clinical heterogeneity was also observed in the included studies. The study cohorts were differed due to different inclusion criteria among the included studies, which led to two comparisons in the review: sepsis versus nonsepsis, and mechanical ventilation versus nonmechanical ventilation.

Statistical heterogeneity

There were high levels of statistical heterogeneity in the review, and statistical heterogeneity remained substantial within each of the five comparisons described (presented in Table 3).

Assessment of publication biases

Funnel plots were used to estimate the publication bias. As depicted in Fig. 3a, b, there was no significant asymmetry found in the funnel plots. Begg’s test (z = 1.06, P = 0.289) and Egger’s test (t = 1.77, P = 0.095) were adopted to detect publication bias in the meta-analysis, and no significant biases were found.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plots. a Begg’s funnel plots of included studies. b Egger’s funnel plots of included studies. s.e. standard error

Discussion

This review synthesized data on the relationship between corticosteroids and ICUAW. We identified 18 studies with a total of 2387 enrolled patients. When the studies were pooled together, the effect size analysis showed that corticosteroid use was a significant risk for developing ICUAW.

Corticosteroid therapy was still an essential treatment option in selected critically ill patients, such as those with refractory septic shock and ARDS. Similar muscle changes to those of animals as a result of corticosteroid therapy had been found in ICU patients [35]. Corticosteroid therapy was found to cause changes in specific gene expression to indicate the inhibition of protein synthesis resulting in promoting muscle wasting [36, 37]. Evaluating the effect of corticosteroid therapy on ICUAW development is critical. Thus, this systematic review synthesized data on the relationship between the use of corticosteroids and ICUAW in ICU patients. In addition, the effect of corticosteroid therapy on ICUAW is complex and may also depend on the duration and cumulative dosage of the corticosteroids. Of the included studies, duration of the corticosteroids was not found to be an independent risk factor for ICUAW [28, 31], but the cumulative doses of corticosteroids were significantly higher in patients with ICUAW than in those without ICUAW in two studies [23, 25] based on univariate analysis. Thus, exposure to corticosteroids should be limited or the dose lowered in clinical practice to reduce the risk of ICUAW.

Our subgroup analyses revealed a stronger association in patients with clinical weakness but not in patients with abnormal electrophysiology. The use of corticosteroids was found to be significantly associated with muscle weakness in the review. However, within the electrophysiology subgroup, the incidences of ICUAW in the corticosteroid and control groups were higher than those found in the clinical assessment subgroup. ICUAW is essentially a clinically detectable weakness, and clinical examinations are easier, timelier, and more convenient to perform than electrophysiology examinations. However, clinical examinations usually cannot be conducted in the early disease course due to suboptimal levels of consciousness or attentiveness. Electrophysiologic studies may have been more sensitive for detecting subclinical ICUAW in both the corticosteroid and control groups, thus resulting in a nonsignificant effect of corticosteroid use on ICUAW in this subgroup. These considerations may represent an alternative explanation for the different outcome.

Our subgroup analyses showed that there was no significant association between the use of corticosteroids and ICUAW in patients with sepsis. Corticosteroids are a critical treatment for patients with sepsis, and the incidence of this condition’s adverse event, ICUAW, was not significantly different in this review. A therapeutic benefit of early low-dose corticosteroid therapy for decreasing mortality was found in septic shock patients with the highest severity of illness [9]. Low-dose and short-term corticosteroid therapy could improve the prognosis of specific critically ill populations without increasing the risk of ICUAW. Our subgroup analyses demonstrated that studies limited to patients with mechanical ventilation still revealed the significant association between corticosteroids and ICUAW. ICUAW significantly increases the duration of mechanical ventilation [2, 38, 39], and thus the benefits of corticosteroids should be weighed against the adverse effect in ICUAW. Our subgroup analyses revealed that studies limited to relatively large sample sizes still demonstrated a significant association between corticosteroid use and ICUAW, and this result partly demonstrates the stability of the overall effect size.

Studies were excluded for the following common reasons: the study design was not a RCT or prospective cohort, insufficient data were reported, and clear diagnostic criteria were lacking. Only RCTs and prospective cohort studies were included in the review. However, only three studies controlled for other additional factors based on multivariate analysis. We demonstrated a modest association between the use of corticosteroids and ICUAW, without adjustment for potential confounders.

There are limitations to our review. The included studies were not population-based cohort studies. Temporal trends were not examined in the included studies. Baseline exposure to corticosteroids was not reported in the included studies and thus could not be examined via meta-regression. Because different risk factors existed across the included studies and because few studies were designed to adjust for other independent risk factors, primary analysis was performed using a univariate approach without adjustment for potential confounders. High levels of heterogeneity were identified for all of the outcomes. We analyzed the outcomes in subgroups classified by study design, diagnostic methods, sample sizes, and study participants in an effort to reduce methodological and clinical heterogeneity; however, substantial statistical heterogeneity remained despite these attempts. Therefore, a random effects model rather than a fixed effects model was selected to address the observed heterogeneity. Additionally, none of the included prospective cohort studies reported the degree of missing data and how missing data were processed, and thus only a form of per-protocol analysis was performed.

Conclusion

First, our review demonstrates a statistically significant association between corticosteroid use and ICUAW. Clinicians should limit exposure to corticosteroids or shorten the administration time to decrease the incidence of ICUAW. Second, we did not find a significant association between the use of corticosteroids and ICUAW in patients with sepsis. Third, our review suggests a significant association between corticosteroid use and ICUAW in patients with mechanical ventilation. For specific critically ill patients, clinicians should target low-dose and short-term corticosteroid therapy in clinical practice to limit the adverse effects of the drugs. Future research should focus on RCTs or prospective cohort studies by performing multivariable adjustment for confounders to identify the associations between the use, duration, and total doses of corticosteroids and ICUAW.

Additional files

PubMed search strategy. (DOCX 15 kb)

Summary of findings for the main comparison. (DOCX 14 kb)

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CI

Confidence interval

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- ICUAW

Intensive care unit-acquired weakness

- MRC

Medical Research Council

- OR

Odds ratio

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- SIRS

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Authors’ contributions

TY and ZqL contributed equally to the study design, study selection, data extraction, quality assessment, data analysis, and writing or revising the manuscript for important intellectual content, gave approval of the final manuscript, and served as principal authors. XmX and LJ contributed to the study conception, design, and data interpretation, revised the manuscript for critical intellectual content, and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Tao Yang, Email: librayt@163.com.

Zhiqiang Li, Email: lzq671@sina.com.

Li Jiang, Email: jiangli2937@sina.com.

Xiuming Xi, Email: xixiuming2937@163.com.

References

- 1.Nguyen The L, Nguyen Huu C. Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy in a rural area in Vietnam. J Neurol Sci. 2015;357(1–2):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hermans G, Van Mechelen H, Clerckx B, Vanhullebusch T, Mesotten D, Wilmer A, Casaer MP, Meersseman P, Debaveye Y, Van Cromphaut S, et al. Acute outcomes and 1-year mortality of intensive care unit-acquired weakness. A cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(4):410–420. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2257OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penuelas O, Muriel A, Frutos-Vivar F, Fan E, Raymondos K, Rios F, Nin N, Thille AW, Gonzalez M, Villagomez AJ, et al. Prediction and outcome of intensive care unit-acquired paresis. J Intensive Care Med. 2018;33(1):16–28. doi: 10.1177/0885066616643529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho YJ, Moon JY, Shin ES, Kim JH, Jung H, Park SY, Kim HC, Sim YS, Rhee CK, Lim J, et al. Clinical practice guideline of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Tuberc Res Dis. 2016;79(4):214–233. doi: 10.4046/trd.2016.79.4.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, Kumar A, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Nunnally ME, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkatesh B, Finfer S, Cohen J, Rajbhandari D, Arabi Y, Bellomo R, Billot L. Adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):797–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annane D, Renault A, Brun-Buisson C, Megarbane B, Quenot JP, Siami S, Cariou A, Forceville X, Schwebel C, Martin C, et al. Hydrocortisone plus fludrocortisone for adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):809–818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annane D, Bellissant E, Bollaert PE, Briegel J, Keh D, Kupfer Y. Corticosteroids for treating sepsis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12:CD002243. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002243.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funk D, Doucette S, Pisipati A, Dodek P, Marshall JC, Kumar A. Low-dose corticosteroid treatment in septic shock: a propensity-matching study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(11):2333–2341. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Confalonieri M, Urbino R, Potena A, Piattella M, Parigi P, Puccio G, Della Porta R, Giorgio C, Blasi F, Umberger R, et al. Hydrocortisone infusion for severe community-acquired pneumonia: a preliminary randomized study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(3):242–248. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-808OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberg KP, Hudson LD, Goodman RB, Hough CL, Lanken PN, Hyzy R, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(16):1671–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Annane D, Sebille V, Bellissant E. Effect of low doses of corticosteroids in septic shock patients with or without early acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):22–30. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000194723.78632.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meduri GU, Golden E, Freire AX, Taylor E, Zaman M, Carson SJ, Gibson M, Umberger R. Methylprednisolone infusion in early severe ARDS: results of a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2007;131(4):954–963. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens RD, Marshall SA, Cornblath DR, Hoke A, Needham DM, de Jonghe B, Ali NA, Sharshar T. A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10 Suppl):S299–S308. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6ef67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan E, Cheek F, Chlan L, Gosselink R, Hart N, Herridge MS, Hopkins RO, Hough CL, Kress JP, Latronico N, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis of intensive care unit-acquired weakness in adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(12):1437–1446. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201411-2011ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 London, UK. Available at: http://handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 15 July 2015.

- 18.Keh D, Trips E, Marx G, Wirtz SP, Abduljawwad E, Bercker S, Bogatsch H, Briegel J, Engel C, Gerlach H, et al. Effect of hydrocortisone on development of shock among patients with severe sepsis: the HYPRESS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1775–1785. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta S, Mishra M. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score of ≥15: a risk factor for sepsis-induced critical illness polyneuropathy. Neurol India. 2016;64(4):640–645. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.185356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wieske L, Witteveen E, Verhamme C, Dettling-Ihnenfeldt DS, van der Schaaf M, Schultz MJ, van Schaik IN, Horn J. Early prediction of intensive care unit-acquired weakness using easily available parameters: a prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel BK, Pohlman AS, Hall JB, Kress JP. Impact of early mobilization on glycemic control and ICU-acquired weakness in critically ill patients who are mechanically ventilated. Chest. 2014;146(3):583–589. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anastasopoulos D, Kefaliakos A, Michalopoulos A. Is plasma calcium concentration implicated in the development of critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy? Crit Care. 2011;15(5):R247. doi: 10.1186/cc10505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharshar T, Bastuji-Garin S, De Jonghe B, Stevens RD, Polito A, Maxime V, Rodriguez P, Cerf C, Outin H, Touraine P, et al. Hormonal status and ICU-acquired paresis in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(8):1318–1326. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1840-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunello AG, Haenggi M, Wigger O, Porta F, Takala J, Jakob SM. Usefulness of a clinical diagnosis of ICU-acquired paresis to predict outcome in patients with SIRS and acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(1):66–74. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber-Carstens S, Koch S, Spuler S, Spies CD, Bubser F, Wernecke KD, Deja M. Nonexcitable muscle membrane predicts intensive care unit-acquired paresis in mechanically ventilated, sedated patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2632–2637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a92f28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanas S, Kritikos K, Angelopoulos E, Siafaka A, Tsikriki S, Poriazi M, Kanaloupiti D, Kontogeorgi M, Pratikaki M, Zervakis D, et al. Predisposing factors for critical illness polyneuromyopathy in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118(3):175–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali NA, O'Brien JM, Jr, Hoffmann SP, Phillips G, Garland A, Finley JC, Almoosa K, Hejal R, Wolf KM, Lemeshow S, et al. Acquired weakness, handgrip strength, and mortality in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):261–268. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1829OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hermans G, Wilmer A, Meersseman W, Milants I, Wouters PJ, Bobbaers H, Bruyninckx F, Van den Berghe G. Impact of intensive insulin therapy on neuromuscular complications and ventilator dependency in the medical intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(5):480–489. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-665OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lefaucheur JP, Nordine T, Rodriguez P, Brochard L. Origin of ICU acquired paresis determined by direct muscle stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(4):500–506. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.070813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan J, Harrison TB, Rich MM, Moss M. Early development of critical illness myopathy and neuropathy in patients with severe sepsis. Neurology. 2006;67(8):1421–1425. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000239826.63523.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, Authier FJ, Durand-Zaleski I, Boussarsar M, Cerf C, Renaud E, Mesrati F, Carlet J, et al. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2859–2867. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garnacho-Montero J, Madrazo-Osuna J, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Ortiz-Leyba C, Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Barrero-Almodovar A, Garnacho-Montero MC, Moyano-Del-Estad MR. Critical illness polyneuropathy: risk factors and clinical consequences. A cohort study in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(8):1288–1296. doi: 10.1007/s001340101009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Letter MA, Schmitz PI, Visser LH, Verheul FA, Schellens RL, Op de Coul DA, van der Meche FG. Risk factors for the development of polyneuropathy and myopathy in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(12):2281–2286. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coakley JH, Nagendran K, Yarwood GD, Honavar M, Hinds CJ. Patterns of neurophysiological abnormality in prolonged critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(8):801–807. doi: 10.1007/s001340050669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massa R, Carpenter S, Holland P, Karpati G. Loss and renewal of thick myofilaments in glucocorticoid-treated rat soleus after denervation and reinnervation. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15(11):1290–1298. doi: 10.1002/mus.880151112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Giovanni S, Molon A, Broccolini A, Melcon G, Mirabella M, Hoffman EP, Servidei S. Constitutive activation of MAPK cascade in acute quadriplegic myopathy. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(2):195–206. doi: 10.1002/ana.10811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aare S, Radell P, Eriksson LI, Akkad H, Chen YW, Hoffman EP, Larsson L. Effects of corticosteroids in the development of limb muscle weakness in a porcine intensive care unit model. Physiol Genomics. 2013;45(8):312–320. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00123.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Jonghe B, Bastuji-Garin S, Sharshar T, Outin H, Brochard L. Does ICU-acquired paresis lengthen weaning from mechanical ventilation? Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(6):1117–1121. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garnacho-Montero J, Amaya-Villar R, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Madrazo-Osuna J, Ortiz-Leyba C. Effect of critical illness polyneuropathy on the withdrawal from mechanical ventilation and the length of stay in septic patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(2):349–354. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000153521.41848.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PubMed search strategy. (DOCX 15 kb)

Summary of findings for the main comparison. (DOCX 14 kb)