Abstract

Background:

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Recent studies have shown that dietary factors play an important role in the development of UC. Index of Nutritional Quality (INQ) is a suitable method that analyzes quantitatively and qualitatively single foods, meals, and diets. The aim of this study was to determine the association between INQ and UC.

Materials and Methods:

Overall, 62 newly diagnosed cases with UC and 124 healthy age- and sex-matched controls were studied in a referral hospital in Tabriz, Iran. INQ scores were calculated based on information on the usual diet that was measured by a valid and reliable Food Frequency Questionnaire consisting of 168 food items. Logistic regression analysis adjusting for age, gender, body mass index, education, smoking, Helicobacter pylori, family history of UC, appendectomy, alcohol, and total energy intake was used to estimate multivariable odds ratios (ORs).

Results:

After controlling for several covariates, we found inverse associations between UC risk and INQs of Vitamin C (OR = 0.34 [0.16–0.73]) and folate (OR = 0.11 [0.01–0.99]). In crude model of analysis, cases had a higher intake of total energy, protein, carbohydrate, total fat, saturated fatty acid, monounsaturated fatty acid, polyunsaturated fatty acid, niacin, Vitamin B6, Vitamin B12, magnesium, zinc, copper, selenium, and iron compared to controls, whereas controls had higher intakes of Vitamin C, Vitamin D, folate, and biotin compared to cases.

Conclusion:

Our results indicate that enough consumption of Vitamin C and folate was associated with lower risk of UC.

Keywords: Folate, Index of Nutritional Quality, inflammatory bowel disease, nutritional assessment, ulcerative colitis, Vitamin C

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease with multifactorial etiologies of genetics immunity and environmental factors. Potentially, environmental factors influence on disease incidence and include breastfeeding, use of antibiotic in infancy, stress in life, diet, and lifestyle.[1] Epidemiological studies showed that environmental factors, especially dietary factors, play an important role in the incidence and development of UC.[2,3,4,5,6] It has been shown that diet and dietary factors influence the intestinal microbiome, epithelial function, and mucosal immune system.[7] There are several methods for analyzing dietary data, one of them is assessing the nutritional quality of the diet which has an important role for health situations, and it summarizes diet in a broader manner than any single nutrient or food.[8] Assessing of dietary quality should be simple and practical,[9] so the Index of Nutritional Quality (INQ) is a suitable method which plays an important role in the assessment of clinical nutritional problem. This method analyzes quantitatively and qualitatively single foods, meals, and diets. The INQ is a ratio of the nutrient-to-calorie content of foods, which it can be shown as bar graphs and tabular data.[10,11]

We conducted this study to determine the relationship between INQ scores and nutrients intake and risk of UC in a case–control study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Details of the study have been reported previously.[12] Overall, 62 new cases of UC and 124 healthy controls were included in the study. The study protocol was approved by our local Ethics Committee. The study protocol has published elsewhere.[12] Dietary intakes of the participants over the past year were assessed using a valid and reliable Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).[13] The study protocol was approved at the Ethics Committee of National Nutrition and Food Technology Institute, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran, with Ethics number of NNFTRI-523.

Assessment of Index of Nutritional Quality

The INQ is a ratio of the nutrient-to-calorie content of foods.[14] The number of nutrients and the nutrient standards used for analysis are flexible parameters, which may be varied for each clinical situation. Illustrative examples include INQ analysis of simple foods, an institutional house diet, the diabetic exchange list, and the diagnostic evaluation of the dietary intake of a hospitalized patient.[15]

We calculated the INQ of each nutrient, using the following formulae: INQ = consumed amount of a nutrient per 1000 kcal/recommended dietary adequate or adequate intake of that nutrient per 1000 kcal. FFQ-derived dietary data were used to calculate INQ scores for all the participants. Nutrients’ intake was calculated using USDA food composition table. Major food items that were used in the calculation of INQ were as follows: protein, Vitamins A, D, K, E, iron, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, folate, biotin, pantothenic acid, Vitamins B6 and B12, magnesium, copper, selenium, and manganese.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used for the comparison of categorical variables between groups. Before choosing the statistical test, the normality of their distribution for each variable was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Then, the independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U-tests were used for the comparison of the continuous variables with normal and nonnormal distribution between groups, respectively. Age-adjusted and multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of having UC in relation to each nutrient's INQ. Adjustments were done for age, gender, body mass index, education, smoking, Helicobacter pylori infection, family history of UC, appendectomy, alcohol consumption, and total energy intake in the adjusted models.

RESULTS

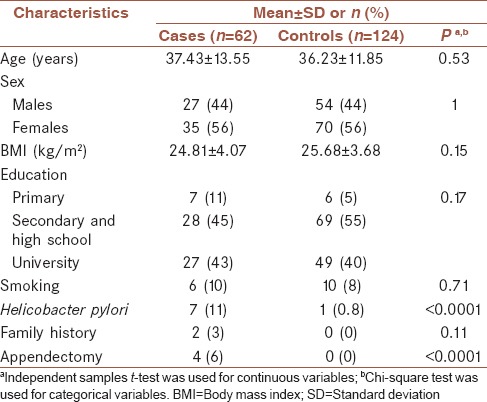

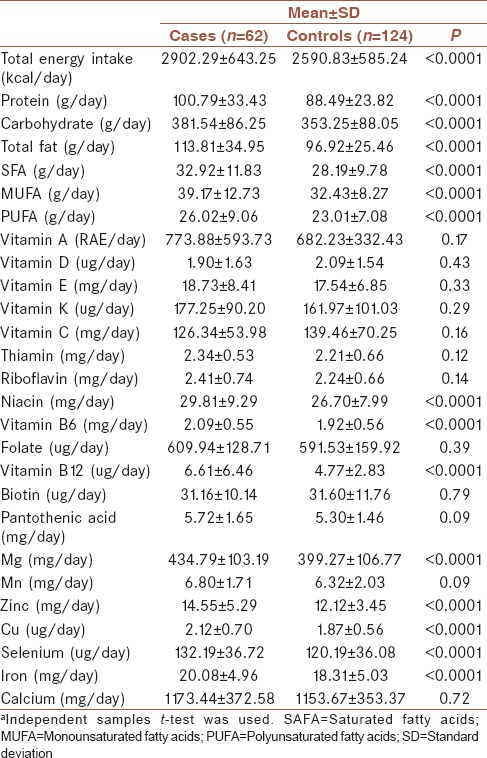

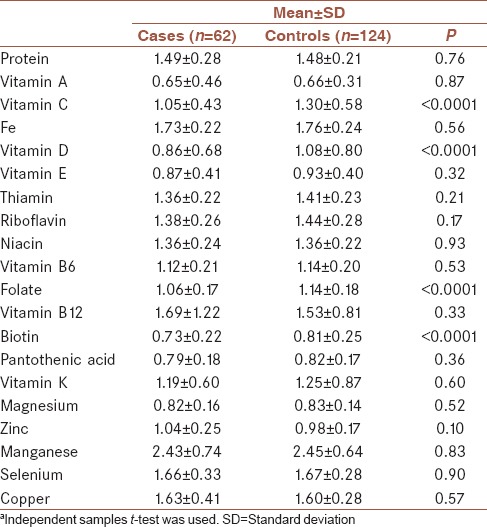

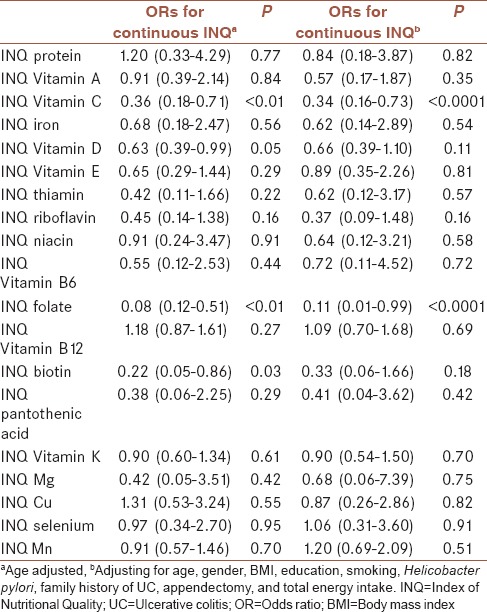

The distribution of demographic characteristics across cases (n = 62) and controls (n = 124) is shown in Table 1. Quantitative and qualitative variables are shown as mean ± standard deviation and number (%), respectively. Cases had a more history of appendectomy and H. pylori infection compared to controls. Table 2 shows the distribution of dietary intakes of macro-micronutrients across cases and controls. As presented in this table, cases had higher intake of total energy (2902.29 ± 643.25 vs. 2590.83 ± 585.24), protein (100.79 ± 33.43 vs. 88.49 ± 23.82), carbohydrate (381.54 ± 86.25 vs. 353.25 ± 88.05), total fat (113.81 ± 34.95 vs. 96.92 ± 25.46), saturated fatty acid (SFA, 32.92 ± 11.83 vs. 28.19 ± 9.78), monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA, 39.17 ± 12.73 vs. 32.43 ± 8.27), polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA, 26.02 ± 9.06 vs. 23.01 ± 7.08), niacin (29.81 ± 9.29 vs. 26.70 ± 7.99), Vitamin B6 (2.09 ± 0.55 vs. 1.92 ± 0.56), Vitamin B12 (6.61 ± 6.46 vs. 4.77 ± 2.83), magnesium (434.79 ± 103.19 vs. 399.27 ± 106.77), zinc (14.55 ± 5.29 vs. 12.12 ± 3.45), copper (2.12 ± 0.70 vs. 1.87 ± 0.56), selenium (132.19 ± 36.72 vs. 120.19 ± 36.08), and iron (20.08 ± 4.96 vs. 18.31 ± 5.03) compared to controls. There was no significant difference between groups in terms of Vitamins A, D, E, K, and C, thiamin, riboflavin, folate, biotin, pantothenic acid, and manganese and calcium intake. Comparison of the INQ of the subjects is shown in Table 3. According to this table, the INQ of Vitamin C (1.30 ± 0.58 vs. 1.05 ± 0.43), Vitamin D (1.08 ± 0.80 vs. 0.86 ± 0.68), folate (1.14 ± 0.18 vs. 1.06 ± 0.17), and Biotin (0.81 ± 0.25 vs. 0.73 ± 0.22) are higher in controls compared to cases. Table 4 shows ORs and 95% CI for the association between INQ and UC. After controlling for several covariates, inverse associations were observed between UC risk and INQs of Vitamin C (OR = 0.34 [0.16–0.73]) and folate (OR = 0.11 [0.01–0.99]).

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic characteristics across cases and controlsa

Table 2.

Distribution of dietary intakes of macro-micronutrients across cases and controlsa

Table 3.

Comparison of the Index of Nutritional Quality of the subjectsa

Table 4.

Odds ratios and confidence intervals for the association between Index of Nutritional Quality and ulcerative colitis

DISCUSSION

This study is the first one to examine the association between INQ and UC risk. Our results showed inverse associations between UC risk and INQs of Vitamin C and folate. In addition, this case–control study showed that UC patients had a higher intake of total energy, protein, carbohydrate, total fat, SFA, MUFA, and PUFA compared to controls. These results were in agreement with studies, in which associations were observed between high total protein intake with a significantly increased risk of UC.[16] However, some studies have found no association between energy, protein and carbohydrate intake, and UC risk.[17] In addition, similar previous studies have shown that there is a positive association between UC risk and intakes of total fat, SFA, PUFA, and MUFA.[12] In contrast, in the Nurses’ Health Study, intakes of total fat, SFA, and PUFA were not associated with risk of UC.[18] Furthermore, a meta-analysis study suggested a lack of association between fat intake and UC risk.[19]

We found that UC patients’ intake of Vitamin B6 and B12, magnesium, zinc, selenium, and iron were significantly higher compared to controls. In contrast, other studies reported that there is inverse association between UC risk and intakes of Vitamins B12 and B6,[20] zinc,[21] selenium,[22] iron,[23] and magnesium,[24] which this conflict could be due to a host of different reasons such as difference in methodology and residual confounding.

Different tools were used to analyze diet quality to evaluate the daily nutrition and the food intake status of patients. INQ is one of these methods for assessing dietary data; the nutritional quality of the diet, which plays an important role in assessing the clinical nutritional problem. In the present study, when we use the INQ instead of absolute intakes, there were fewer differences between groups in dietary intakes. In addition, this method summarized diet in a broader manner than any single nutrient or food. Micronutrients such as Vitamin C and folate play an important role in the prevention of UC.[25] These vitamins alter the bowel flora and have an immune-modulatory effect through several mechanisms.[26] Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other indices such as nitrogen species generated by inflammatory cells in damaged tissues.[27] An imbalance in the production of ROS and antioxidant components may play an important role in the pathogenesis of UC.[28] The presence of Vitamin C as an antioxidant component prevents oxidative injury in the inflamed mucosa and increases antioxidant defense that may be decreased susceptible to oxidative tissue damage in UC pathogenesis.[29] Epigenetic regulation, through DNA methylation, has an important role in the protection from diseases such as UC.[30] However, there is little information about the role of nutrition in the epigenetic regulation of UC;[7] folate has an essential role in the synthesis, methylation, and repair of DNA that prevents from the alternation of gene expression and increased DNA damage and UC development.[31]

This study has several strengths; the present study is the first one to report the association between INQ and UC risk. In addition, assessment of dietary quality by the INQ is simple and accurate in comparison to other methods because it adjusts the effects of energy intake. Another strength of this study is the use of a valid and reliable FFQ[24] for assessing food and nutrient intakes. Finally, the selection of controls was carefully and they had not situation related to diet or other major risk factors associated with UC.

This study had some limitations. Since we used an FFQ, measurement errors were inevitable. Other limitations include relatively low sample size and recall bias due to its case–control design. In addition, use of INQ is one of the limitations. We calculated INQ based on Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) and since there is not DRI for all nutrients or food items, so INQ cannot be calculated for all of them. Therefore, it is possible that the potential effects of these nutrients or food items on UC have been ignored in the present study.

CONCLUSION

Our findings suggest that enough intake of Vitamin C and folate was associated with lower risk of UC. Therefore, public health advice should emphasize the importance of increasing intake of these nutrients from a nutrient-rich diet for prevention of UC. These findings need to be confirmed in other populations with high methodological quality.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants in this study without whom this study was not possible.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:205–17. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hekmatdoost A, Feizabadi MM, Djazayery A, Mirshafiey A, Eshraghian MR, Yeganeh SM, et al. The effect of dietary oils on cecal microflora in experimental colitis in mice. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2008;27:186–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hekmatdoost A, Mirshafiey A, Feizabadi MM, Djazayeri A. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, microflora and colitis. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;55:325. doi: 10.1159/000248990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hekmatdoost A, Wu X, Morampudi V, Innis SM, Jacobson K. Dietary oils modify the host immune response and colonic tissue damage following Citrobacter rodentium infection in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G917–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00292.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samsamikor M, Daryani NE, Asl PR, Hekmatdoost A. Resveratrol supplementation and oxidative/Anti-oxidative status in patients with ulcerative colitis: A Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Arch Med Res. 2016;47:304–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samsami-Kor M, Daryani NE, Asl PR, Hekmatdoost A. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol in patients with ulcerative colitis: A Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Arch Med Res. 2015;46:280–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vahid F, Zand H, Nosrat-Mirshekarlou E, Najafi R, Hekmatdoost A. The role dietary of bioactive compounds on the regulation of histone acetylases and deacetylases: A review. Gene. 2015;562:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slattery ML. Defining dietary consumption: Is the sum greater than its parts? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:14–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coulston AM. The search continues for a tool to evaluate dietary quality. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:417. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vahid F, Hatami M, Sadeghi M, Ameri F, Faghfoori Z, Davoodi SH, et al. The association between the Index of nutritional quality (INQ) and breast cancer and the evaluation of nutrient intake of breast cancer patients: A case-control study. Nutrition. 2018;45:11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vahid F, Rahmani G, Naeini AF, Falahnejad H, Davoodi SH. The association between index of nutritional quality (inq) and gastric cancer and evaluation of nutrient intakes of gastric cancer patients: A case-control study. Int J Cancer Manag. 2018;11:e9747. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2018.1412469. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rashvand S, Somi MH, Rashidkhani B, Hekmatdoost A. Dietary fatty acid intakes are related to the risk of ulcerative colitis: A case-control study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1255–60. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esfahani FH, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Reproducibility and relative validity of food group intake in a food frequency questionnaire developed for the Tehran lipid and glucose study. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:150–8. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorenson AW, Wyse BW, Wittwer AJ, Hansen RG. An index of nutritional quality for a balanced diet. New help for an old problem. J Am Diet Assoc. 1976;68:236–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shayanfar M, Vahid F, Faghfoori Z, Davoodi SH, Goodarzi R. The association between index of nutritional quality (inq) and glioma and evaluation of nutrient intakes of these patients: A case-control study. Nutr Cancer. 2018;70:213–220. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2018.1412469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rashvand S, Somi MH, Rashidkhani B, Hekmatdoost A. Dietary protein intakes and risk of ulcerative colitis. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29:253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang F, Feng J, Gao Q, Ma M, Lin X, Liu J, et al. Carbohydrate and protein intake and risk of ulcerative colitis: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:1259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Konijeti GG, Higuchi LM, de Silva P, Fuchs CS, et al. Long-term intake of dietary fat and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Gut. 2014;63:776–84. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang F, Lin X, Zhao Q, Li J. Fat intake and risk of ulcerative colitis: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:19–27. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vagianos K, Bernstein CN. Homocysteinemia and B Vitamin status among adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A one-year prospective follow-up study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:718–24. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh J, O’Morain CA. Review article: Nutrition and adult inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:307–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudva AK, Shay AE, Prabhu KS. Selenium and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G71–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00379.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vagianos K, Bector S, McConnell J, Bernstein CN. Nutrition assessment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2007;31:311–9. doi: 10.1177/0148607107031004311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galland L. Magnesium and inflammatory bowel disease. Magnesium. 1988;7:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisshof R, Chermesh I. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2015;18:576–81. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alkhouri RH, Hashmi H, Baker RD, Gelfond D, Baker SS. Vitamin and mineral status in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:89–92. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826a105d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buffinton GD, Doe WF. Depleted mucosal antioxidant defences in inflammatory bowel disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:911–8. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)94362-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lih-Brody L, Powell SR, Collier KP, Reddy GM, Cerchia R, Kahn E, et al. Increased oxidative stress and decreased antioxidant defenses in mucosa of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2078–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02093613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buffinton GD, Doe WF. Altered ascorbic acid status in the mucosa from inflammatory bowel disease patients. Free Radic Res. 1995;22:131–43. doi: 10.3109/10715769509147535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnett M, Bermingham E, McNabb W, Bassett S, Armstrong K, Rounce J, et al. Investigating micronutrients and epigenetic mechanisms in relation to inflammatory bowel disease. Mutat Res. 2010;690:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hekmatdoost A, Vahid F, Yari Z, Sadeghi M, Eini-Zinab H, Lakpour N, et al. Methyltetrahydrofolate vs. folic acid supplementation in idiopathic recurrent miscarriage with respect to methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T and A1298C polymorphisms: A Randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]