Highlights

-

•

Giant pheochromocytomas are rare.

-

•

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion.

-

•

Commonly present with a triad of headache, palpitations and hypertension.

-

•

The surgical and anaesthetic team must be prepared to manage hypertensive crisis.

Keywords: Giant pheochromocytoma, Catecholamine, Metanephrines, Alpha and beta-blockade, Adrenalectomy, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Pheochromocytomas are catecholamine producing tumours which arise from chromaffin cells within the adrenal medulla. Patients with these tumours commonly present with a triad of headache, palpitations and hypertension.

Case presentation

We present a case of a 37-year-old male patient who presented with dull left sided abdominal pain and discomfort for 6 weeks. A preoperative Computed tomography (CT) scan showed a huge left suprarenal tumour but urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) were negative. The patient underwent an open surgical resection via an extraperitoneal approach without untoward intraoperative and postoperative events. Histopathological evaluation of the specimen showed a pheochromocytoma with a PASS score of 9. The successful management of the patient highlights the good results of team work despite the limitations of preoperative diagnosis.

Discussion

Giant pheochromocytomas by definition are tumours more than 7 cm in size and are rare. They rarely secrete catecholamines and commonly present with vague abdominal symptoms. A computerized tomogram helps suggest the diagnosis whilst the biochemical workup for pheochromocytoma may be diagnostic. If the tumours are biochemically active, preoperative alpha-blockade is necessary and care must be taken at operation in handling the tumour. The surgical and anaesthetic team must be prepared to manage hypertensive crisis should it occur.

Conclusion

This case brings to the attention of clinicians the need to have a high index of suspicion of a giant pheochromocytoma in a patient presenting with vague abdominal symptoms whose CT scan shows a large retroperitoneal tumour, even in the absence of clinical symptoms and negative or absent biochemical workup.

1. Introduction

This work is reported in line with the Surgical Case Report Guidelines (SCARE) criteria [1]. Pheochromocytomas are catecholamine producing tumours arising from chromaffin cells within the adrenal medulla with a reported incidence of 0.1% in the general population [2,3]. The majority of pheochromocytomas are benign. Similar tumours arising from the sympathetic and parasympathetic chain are called paragangliomas and the majority of these tumours are non-secreting [4]. Pheochromocytoma commonly present with a triad of headache, palpitations and hypertension [5] due to the production of adrenaline, noradrenaline, dopamine and their metabolites. Pheochromocytoma can arise sporadically or as part of hereditary syndromes. Sporadic cases usually occur in the fourth and fifth decade of life and has equal gender distribution [6]. Hereditary pheochromocytoma occur in association with von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN-2A/2B), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), and hereditary pheochromocytoma-paraganglioma (due to mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase gene mutations) [2,7,8].

Giant pheochromocytoma are by definition tumours more than 7 cm and are rare [[9], [10], [11]]. The majority of giant pheochromocytomas do not secrete catecholamines and hence do not present with classical symptoms of pheochromocytoma [11]. They present with vague abdominal symptoms. Computed tomography (CT) scan is the gold standard in the diagnosis of giant pheochromocytoma [10]. However there maybe diagnostic uncertainties in the determination of the organ of origin of these tumours. On CT scan they appear as large retroperitoneal tumours [9]. Biochemical evidence of elevated plasma free metanephrines and normetanephrines provides high sensitivity in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma [12]. Alpha blockade is not necessary as these tumours are biochemically inert. A multidisciplinary approach is advocated for, for successful management of phaeochromocytoma. Care must be taken when handling pheochromocytoma intraoperatively as release of catecholamines can trigger a hypertensive crisis. Early isolation of the venous drainage of the tumour reduces the risk of hypertensive crises [9].

The majority of pheochromocytomas including the giant category are benign. Histopathological morphological features will not distinguish benign tumours from malignant ones. This diagnosis of a malignant one is only confidently made by presence of metastases. The pheochromocytoma of adrenal origin scaled score (PASS) is used to try to predict malignant behavior [13]. Biologically aggressive tumours have been found to generally have a PASS score ≥4 [15]. However, this is not definitive, and is only suggestive of malignancy. Histopathological diagnosis of malignant pheochromocytoma is made if ectopic chromaffin cells are detected in the extra-adrenal sites [15].

2. Case report

A previously well 37-year-old male patient, presented to the general surgery outpatient department at a public and teaching hospital, complaining of dull left lumbar pain and abdominal discomfort which was intermittent for six weeks. He was referred to the outpatient clinic because of worsening discomfort and early satiety. He had no co-morbid conditions and there was no family history of malignancy. He did not smoke nor drink alcohol.

On examination he was well-looking, apyrexial, normotensive and not in any distress. On abdominal examination, there was left flank fullness on inspection and on palpation a mass approximately 14 cm was palpable in the left upper quadrant. The mass was non-tender, non-pulsatile and not expansile. Examination of other systems was normal.

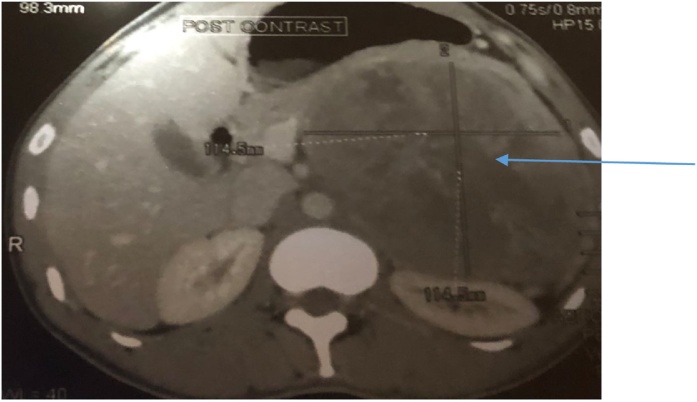

A preoperative CT scan showed a large retroperitoneal tumour 14.3 cm by 12.3 cm arising from the left adrenal gland. The tumour was pushing the diaphragm superiorly, the stomach medially and the left kidney posteriorly as shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2. A diagnosis of a giant adrenal mass, possibly pheochromocytoma was made and the patient was admitted for biochemical and haematological workup as well as blood pressure monitoring. Wide consultation was made and this included Endocrinologists, Physicians, Radiologists, Pathologists, Laboratory scientists and Surgeons.

Fig. 1.

Tumour (arrow) in transverse section.

Fig. 2.

Tumour (arrow) in sagittal section.

The biochemical and haematological results were normal as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biochemical and Haematological results.

| TEST | RESULT |

|---|---|

| Sodium | 143mmol/l |

| Potassium | 3.8 mmol/l |

| Urea | 3.3 mmol/l |

| Creatinine | 82 umol/l |

| White cell count | 7.2 × 10^9/l |

| Haemoglobin | 12 g/dl |

| Platelets | 151 × 10^9/l |

High performance liquid chromatography(HPLC) to measure serum metanephrines was not available at our institution at the time, so 24-hour urine collection for vanillylmandelic acid(VMA), homovanillic acid (HVA) and metanephrines was commenced. The following are the results on Table 2.

Table 2.

24-h urinary results for VMA, HVA, Creatinine and Metanephrines.

| TEST | RESULT | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Urine PH | 1.0 | |

| Urine volume | 3740 mls | |

| Urine creatinine | 11.9 mmol/24 h | 7.10–17.70 |

| 24 h VMA excretion | 22.4 umol/24 h | <33 |

| VMA: Creatinine excretion | 1,89 | <4.7 |

| 24 h HVA excretion | 48 | <48 |

| HVA: Creatinine ratio | 4.10 | <6.0 |

| Metanephrine | 60 ug/ 24 h | 42–290 |

| Normetanephrine | 102 ug/24 h | 82–500 |

The patient did not need a preoperative alpha- blockade and his blood pressure remained normal throughout the preoperative period.

We opted for open approach but initially had difficulty in deciding the best incision (transperitoneal vs extraperitoneal) which would give best access and also minimizing tumour seeding as we had no knowledge of the malignant potential of the tumour. We opted for an open approach best on probabilities. Even having decided on what we thought was the best incision access and tumour mobilization were great challenges. The incision had to be extended there by compromising the final cosmetic appearance.

Tumour excision was carried out via an extra-peritoneal approach. It was done by two senior surgeons. This approach was employed in order to get easy access and reduce risks of damage or hemorrhage of intra-abdominal structures. Early isolation of venous drainage of the left adrenal gland was achieved first, followed by adrenalectomy. Extreme care was taken during manipulation and handling of the tumour.

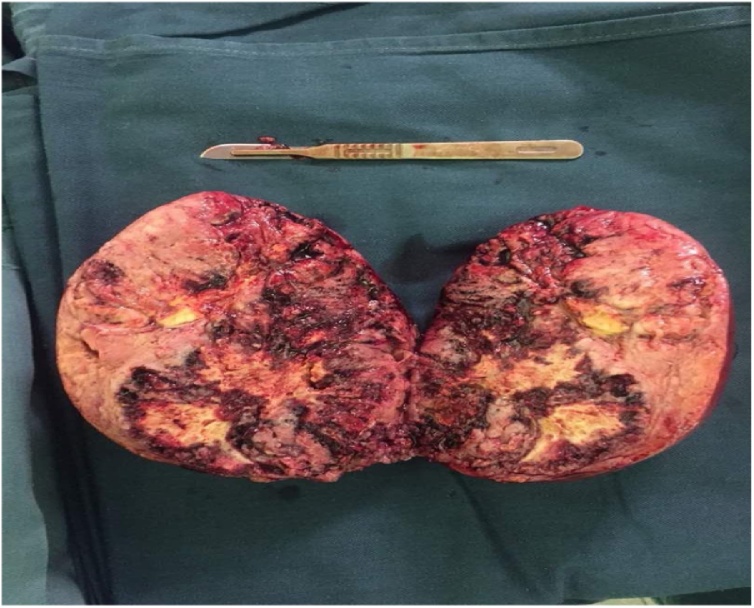

Intraoperative images of the tumour are shown in Fig. 3, Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

A) Tumour being mobilize 3B) Tumour fully mobilised and ready for final excision from remaining attachments.

Fig. 4.

Tumour size as measured by a surgical scalpel and blade. The tumour measured 15 cm × 14.8 cm × 12.2 cm and weighed 1019.57 g. The cut surface was tan with extensive haemorrhagic, and focal necrotic areas.

The microscopic examination showed a cellular lesion with large polygonal cell. The cells were arranged in a vaguely nested pattern with a delicate vascular stroma surrounding the nests to produce the typical “Zellballen” pattern (Fig. 5A H & E. ×100). The nests are cellular and cells have hyperchromatic nuclei that are crowded together (Fig. 5B H and E ×200). Large polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and tumour giant cells (Fig. 5C. H&E x 400). The tumour PASS score was 9 (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Microscopy The cells were arranged in a vaguely nested pattern with a delicate vascular stroma surrounding the nests to produce the typical “Zellballen” pattern (Fig. 5A H & E. × 100). The nests are cellular and cells have hyperchromatic nuclei that are crowded together (Fig. 5B H and E x 200). Large polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and tumour giant cells (Fig. 5C. H&E x 400).

Table 3.

PASS score.

| Parameter | Score |

|---|---|

| Greater than 2 mitosis per 10HPF | 2 |

| Atypical mitosis | 2 |

| Necrosis | 2 |

| Marked nuclear pleomorphism | 2 |

| Capsular invasion | 0 |

| Vascular invasion | 0 |

| Hyperchromasia | 1 |

| TOTAL SCORE | 9 |

The patient is on long term outpatient follow up. He was well and completely asymptomatic at last review three months after surgery.

3. Discussion

Giant pheochromocytoma by definition are tumours more than 7 cm in size [[9], [10], [11]]. They are rare and thus making the formulation of treatment guidelines difficult. Literature search has shown that to date only 30 cases have been reported, making our case the thirty first. The majority of these tumours are benign and do not secrete catecholamines [11]. They therefore lack the classical triad of headache, palpitations and hypertension typical of catecholamine secreting pheochromocytoma [5]. They tend to present with vague abdominal symptoms [11]. Our case was a sporadic case [6] and presented with vague abdominal symptoms. Postulations given for failure to produce catecholamines are tumour necrosis, abundant interstitial tissue compared to chromaffin cells and encapsulation of tumour by connective tissue resulting in paucity of release of catecholamines [11]. Paucity of symptoms made diagnosis difficulty (giant pheochromocytoma non-secreting). Team work and a high index of suspicion was required. Biochemical work -up did not contribute to making a diagnosis (as the tumours are biochemically inert).

A CT scan remains the cornerstone for the diagnosis of giant pheochromocytoma [9]. However, a CT scan is not readily available and accessible at our institution. There is one CT scanner for a 400- bed institution. Even when the patient was finally booked, he could not afford the cost. We had to do a lot of patient advocacy. Computer Tomography scan can only suggest the diagnosis. In the case of our patient the diagnosis was not clear on CT scan even to the radiologist (no diagnostic criteria for giant phaeochromocytoma). Though these tumours are non-secreting once the CT scan suggests the diagnosis then a complete biochemical workup needs to be done to prevent intraoperative and post-operative hypertensive crises which can be catastrophic.

Biochemical evidence of elevated plasma free metanephrines and normetanephrines provides high sensitivity in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma [12]. Serum metanephrines can be assayed using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [17]. The HPLC method of determination of serum metanephrines has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 94% [17]. However, these biochemical test with high sensitivity and specificity were not available so we ended up settling for inferior tests combined with imaging and team work. In the absence of HPLC as in our case twenty-four hour urinary measurements of vanillylmandelic acid (VMA), homovanillic acid (HVA) and metanephrines help in making a diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma. Urinary metanephrines have a sensitivity of 98%, whilst VMA has a sensitivity of 72% [18]. However, in our case, all these levels were normal, creating a diagnostic challenge of a “silent” pheochromocytoma.

Teamwork results in good outcomes. Our case is a good example. Relevant specialists need to be consulted for effective patient management. Our case did not need alpha-blockade, as it was biochemically inactive. To get the patient done was a great challenge because of the long elective surgical backlog. Patient advocacy made it possible for the patient to be operated. Intensive Care Unit bed availability delayed the much needed operation. We waited for bed availability. Factors that forced us to manage this case in a resource limited deficit were 1) increasing severity of patient symptoms, 2.) fear of malignant disease and 3.) the patient had no other option because of financial incapacity.

Though more and more cases of pheochromocytoma are being operated on laparoscopically, because of advantages of less blood loss, shorter hospital stay and earlier oral intake, our case was done open via an extra-peritoneal approach because of the tumour size [19,20]. The open extraperitoneal approach provided good access and potentially prevented any intraperitoneal seeding of tumour. There is a paucity of information in the literature on laparoscopy experience with giant pheochromocytomas.

The majority of pheochromocytomas are benign. The PASS score is used to assess the malignant potential of a pheochromocytoma [[13], [14], [15]]. A Pheochromocytoma with a PASS score of 4 or more has a malignant potential [15]. Our case had a PASS score of 9 as shown in Table 3. Our patient had a high PASS score but with no extra adrenal lesions to prove malignancy was also another challenge. Patient surveillance through clinical and imaging examination was done. Lack of data and chemotherapeutic drugs for the management of malignant pheochromocytoma warranted continued patient surveillance. Poor prognosis with 50% survival at five years has been reported [16] for malignant pheochromocytoma with the only hope being complete surgical excision [16]. Periodic clinical and imaging surveillance is recommended to detect recurrences in patients with a high PASS score [7].

4. Conclusion

This case brings to the attention of clinicians the need to have a high index of suspicion of a giant pheochromocytoma in a patient presenting with vague abdominal symptoms whose CT scan shows a large retroperitoneal tumour, even in the absence of clinical symptoms and negative or absent biochemical workup. Our case further illustrates that teamwork with the correct surgical approach results in a good outcome.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Funding

There is no funding for the case report.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been exempted by our institution.

Consent

A written consent was obtained and is available on request.

Author contribution

David Muchuweti – case report design, subject research, consent and writing.

Edwin G Muguti – case report design, subject research and writing.

Bothwel A Mbuwayesango – case report design, subject research and writing.

Simbarashe G Mungazi – case report design and writing.

Rudo Makunike Mutasa – case report design, subject research and writing.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable. This is a case report with no recruitment of patients.

Guarantor

D. Muchuweti.

E.G. Muguti.

Contributor Information

David Muchuweti, Email: drdmuchuweti@gmail.com.

Edwin G. Muguti, Email: egmuguti@yahoo.com.

Bothwell A. Mbuwayesango, Email: bambuwa@yoafrica.com.

Simbarashe Gift Mungazi, Email: sgmungazi@gmail.com.

Rudo Makunike-Mutasa, Email: rmutasa@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta, Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consesus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;6(September (34)):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler J.T., Meyer-Rochow G.Y., Chen H. Pheochromocytoma: current approaches and future directions. Oncologist. 2008;13:779–793. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahia P.L. Evolving concepts in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2006;18:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000198017.45982.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delerris R.A., Lloyd R.V., Heitz P.U., Eng C. IARC; 2004. Pathology and and Genetics of Tumours of Endocrine Origin: Who Health Organisation Classification of Tumuors. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Därr R., Lenders J.W., Hofbauer L.C. Pheochromocytoma: update on disease management. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;3:11–26. doi: 10.1177/2042018812437356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reisch N., Peczkowska M., Januszewicz A. Pheochromocytoma: presentation, diagnosis and treatment. J. Hypertens. 2006;24:2331–2339. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000251887.01885.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low G., Sahi K. Clinical and imaging overview of functional adrenal neoplasms. Int. J. Urol. 2012;19:697–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan Z., Repertinger S., Deng C. A giant cystic pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland. Endocr. Pathol. 2008;19:133–138. doi: 10.1007/s12022-008-9016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H.L., Sun B.Z., Xu Z.J. Undiagnosed giant cystic pheochromocytoma: a case report. Oncol. Lett. 2015;10(3):1444–1446. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambati D., Jana K., Domes T. Largest pheochromocytoma reported in Canada: a case study and literature review. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2014;8(5–6):E374–E377. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li C., Chen Y., Wang W. A case of clinically silent giant right pheochromocytoma and review of literature. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2012;6(6) doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11195. E267–E26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen-Martin M.A., Hammer G.D. Phaeochromocytoma, update on risk groups, diagnosis and management. Hosp. Physician. 2006;2(2):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson L.D. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2002;26(5):551–566. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenhofer G., Bornstein S.R., Brouwers F.M. Malignant pheochromocytoma: current status and initiatives for future progress. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2004;11(3):423–436. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glodny B., Winde G., Herwig R. Clinical differences between benign and malignant pheochromocytomas. Endocr. J. 2001;48(2):151–159. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.48.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenhofer G., Bornstein S.R., Brouwers F.M. Malignant pheochromocytoma: current status and initiatives for future progress. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2004;11(3):423–436. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marini M., Fathi M., Vallotton M. Determination of serum metanephrines in the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Ann. Endocrinol. (Paris) 1994;54(5):337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James G., Boyle D., Fraser Davidson Colin G., Perry John M.C. Connell of diagnostic accuracy of urinary free metanephrines, vanillyl mandelic acid, and catecholamines and plasma catecholamines for diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92(December (12)):4602–4608. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H.S., Li C.C., Chou Y.H. Comparison of laparoscopic adrenalectomy with open surgery for adrenal tumors. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2009;25(8):438–444. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70539-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tiberio G.A., Baiocchi G.L., Arru L. Prospective randomized comparison of laparoscopic versus open adrenalectomy for sporadic pheochromocytoma. Surg. Endosc. 2008;22(6):1435–1439. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9904-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]