Abstract

Background

To identify aggression and its association with suicidality in migraine patients.

Methods

We enrolled 144 migraine patients who made their first visit to our headache clinic. We collected data regarding their clinical characteristics and the patients completes the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ) and other questionnaires. We also interviewed patients with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview—Plus Version 5.0.0 (MINI) to identify their suicidality. The degree of aggression in migraine patients was compared to the degree of aggression in healthy controls. Major determinants for aggression and its association with suicidality were also examined.

Results

The overall AQ score and anger and hostility subscale scores were higher in migraine patients than controls. For migraine chronicity, patients with chronic migraine (CM) had a higher overall AQ score and physical aggression, anger, and hostility subscale scores than controls. On the other hand, all AQ scores in patients with episodic migraine were not different from the scores of the controls. Although several factors were associated with the overall AQ score, major determinants were anxiety (ß = 0.395, p < 0.001), headache intensity (ß = 0.180, p = 0.016), and CM (ß = − 0.165, p = 0.037). Patients who had suicidality based on the MINI showed a higher overall AQ score than patients without suicidality (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Aggression is likely to be a common feature in CM. Comorbid aggression may help to identify suicidality in migraine patients.

Keywords: Aggression, Migraine, Suicidality, Determinant, Anxiety, Headache intensity

Background

Migraine is a disabling neurological disorder due to recurrent attacks of headache and accompanying psychosomatic symptoms such as depression, anxiety, sleep problems, and fatigue [1–3]. These symptoms restrict daily activities, heighten mortality, impair quality of life and increase the social burden [1, 3, 4]. Migraine was a main cause of burden for the Korean public in a review study on global burden of disease in 2013 [5]. For these reasons, migraine patients should be managed appropriately to lessen those problems.

Aggression is a psychobehavioral symptom defined as overt, often harmful, social interaction that is intended to inflict damage or other unpleasantness on another people [6]. It places substantial burden and costs on human society [7]. Aggression takes a variety of forms including aggression-related feelings, such as anger or hostility, and aggression-related behaviors such as physical or verbal aggression [8]. Data from human and animal studies suggested that the amygdala and associated limbic structures, the frontal lobes, the periaqueductal gray, and the hypothalamus were responsible for the manifestation of aggression [9]. Aggressive behaviors have been commonly reported in psychiatric disorders, such as intermittent explosive disorder, psychosis, and substance abuse, and in neurological disorders, such as epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease [10].

Migraine patients have been reported to exhibit aggressive behavior as a specific personality traits, along with neuroticism and borderline personality disorder (BPD) [11]. Migraine patients showing neuroticism were more likely to experience depression, anxiety, fear, anger, frustration, and envy than ordinary people [12]. Moreover, patients with a high level of neuroticism were at risk for the development of psychiatric disorders [11]. The hallmark features of BPD are fluctuating instability in self-image, interpersonal relationships, and emotions [13]. Intense mood swings, impulsive behaviors, and extreme reactions can make it difficult for people with BPD to complete schooling, maintain stable jobs and have long-lasting, healthy relationships. Approximately, 10% of people affected by BPD kill themselves [13]. Due to these reasons, the existence of aggression is likely to be an important issue in migraine patients. However, the nature of aggression in migraine patients has been underrecognized and has not been examined systematically.

Aggression occurs in relation to physical pain. In the General Aggression Model, physical pain as a situational factor influences cognitions, feelings, and arousal, which in turn affects appraisal and decision processes, which in turn influence aggressive or nonaggressive behavioral outcomes [14]. Migraine patients suffer from recurrent severe headache as physical pain. In this context, it is important to understand the appearance of aggression in relation to the appearance of a headache. Aggression is a facilitator for aggravating suicidality levels up to highly lethal suicidal attempts in the atmosphere of unbearable mental pain including depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and distress [15]. Migraine has been known to be associated with depression, anxiety, and suicidality [2, 16]. Therefore, it is also important to acknowledge aggression in relation to suicidality in migraine patients because lethal suicidal attempts are associated with mortality. Therefore, the aim of our study is to investigate the clinical significance of aggression and its association with suicidality in migraine patients.

Methods

Subjects

New patients with migraine who consecutively visited our headache clinic were enrolled from January 2017 to September 2017. Patients aged between 20 and 70 were included. Patients were diagnosed by the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition, beta version [17]. Patients who had illiteracy, mental retardation, serious medical, neurological, or psychiatric disorders, and history of alcohol or drug abuse that prevented them from cooperating with us during the study were excluded. Patients who refused to complete questionnaires and whose diagnosis was a probable migraine were also excluded. Initially, 163 new patients visited our clinic. Of them, 19 patients were excluded due to a probable migraine diagnosis (n = 8), refusal to enter the study (n = 7), younger age (n = 3), and illiteracy (n = 1). In the end, 144 patients were eligible for the study. The same number of age-, gender-, and education-matched healthy controls were also invited to participate. They were university students, office workers, teachers, or hospital employees.

Study design

This is a case-control study. The Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University Hospital approved the study. All participants gave written informed consent. SP Park interviewed each patient and collected demographic and clinical information. We collected data on their employment and household income, height and weight, age at onset of migraine, duration of migraine, type of migraine, migraine chronicity, family history of migraine, medication overuse headache (MOH), headache intensity, and associated symptoms including nausea and/or vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, and allodynia. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight. Headache intensity was measured by a visual analog scale (VAS). Patients were asked to describe the highest intensity of headache in the preceding 4 weeks. Photophobia, phonophobia, and osmophobia during migraine attacks were defined as hypersensitivity to light, sound, and certain odors, respectively. Allodynia was measured by the 12-item Allodynia Symptom Checklist (ASC-12) with a cut-off score of > 2 to define allodynic patients [18].

Eligible subjects completed several self-reported questionnaires, including the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ) [19], the Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS) [20], the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [21], the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) [22], the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [23], and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [24]. A trained neuropsychologist assessed the suicidality of patients with the suicidality module of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview—Plus Version 5.0.0 (MINI) [25].

Questionnaires

Aggression questionnaire (AQ)

The AQ was developed by Buss and Perry; it measures aggressive behavior and consists of 29 items in four subscales: Physical Aggression (9 items), Verbal Aggression (5 items), Anger (7 items) and Hostility (8 items) [26]. Responses to all items are given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ (1) to ‘always’ (5); subscale scores can be summed to obtain an overall score. Higher scores indicate greater aggression. A validated Korean version of the AQ has been produced [19]. During the validation process, a decision was taken to omit two of the original items from the anger subscale (‘Some of my friends think I’m a hothead’ and ‘Sometimes I fly off the handle for no good reason’) because they related more to verbal aggression and hostility than anger. For this study, 27 items were used for the evaluation of aggression. Cronbach’s a coefficient for the Korean version of the AQ was 0.86.

Migraine disability assessment scale (MIDAS)

The Korean version of the MIDAS includes a 5-item questionnaire to evaluate disability during the past three months [20]. Scores were used to measure the overall level of disability. Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale was 0.75.

Patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The Korean version of the PHQ-9 has been validated in patients with migraine [21]. It includes nine items pertaining to DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD). The overall score ranges from 0 to 27, with a higher score indicating a higher degree of depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale was 0.894.

Generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

The Korean version of the GAD-7 has been validated in patients with migraine [22]. It consists of seven items pertaining to DSM-IV criteria for GAD. The overall score ranges from 0 to 21, with a higher score meaning a higher degree of anxiety symptoms. Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale was 0.915.

Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS)

The Korean version of the ESS has been validated in patients with obstructive sleep apnea [23]. ESS is composed of eight questions, each of them asking about the subject’s likelihood of dozing off or falling asleep in a particular situation that is common in daily life. A higher score indicates a higher subjective sleepiness. Cronbach’s α coefficient of ESS was 0.917.

Insomnia severity index (ISI)

The Korean version of the ISI has been validated in patients with sleep disorders [24]. The ISI is a seven-item questionnaire that measures patient’s perception of insomnia severity. Its total score ranges from 0 to 28, with a higher score indicating a greater insomnia severity. Cronbach’s α coefficient of ISI was 0.92.

Interview

MINI international neuropsychiatric interview—Plus version 5.0.0 (MINI)

The MINI is a brief, structured interview based on DSM-IV criteria [25]. For identifying suicidality, a neuropsychologist (JH Lee) conducted the suicidality module of the MINI. It is composed of six questions that are weighted differently, and include five questions asking about current suicidality (which includes suicidal ideation or an attempt in the preceding month; the questions were about a wish for death [weight 1], a wish for self-harm [weight 2], suicidal thoughts [weight 6], a suicide plan [weight 10], and a suicide attempt [weight 10], and one question asking about lifetime suicide attempts [weight 4]). If respondents said “yes” for at least one of the six questions, they were thought to have suicidality. The degree of current suicidality was estimated from the sum of the weighted score of the six questions, with low (1–5), moderate (6–9), and high (≥10) levels of suicide risk.

Statistical analyses

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 22.0) was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics are presented as counts, percentages, means, and standard deviations. Student’s t-test or chi-squared test was applied to compare two groups. To determine the relationship between various independent variables and the overall AQ score, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was determined. Dummy variables are used for categorial variables. Variables having significant correlation with the overall AQ score were then included in multiple linear regression analyses with stepwise selection using entry and exit probabilities of 0.05 and 0.1, respectively. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic, socioeconomic, clinical, and psychosomatic characteristics in migraine patients compared with healthy controls are listed in Table 1. Demographic and socioeconomic states and BMI in migraine patients were not different from those of healthy controls. Of 144 migraine patients, 56 patients (38.8%) had chronic migraine (CM) and 35 patients (24.3%) had suicidality.

Table 1.

Characteristics of migraine patients and healthy controls

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD (range) or number (%) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migraine patients | Healthy controls | ||

| (n = 144) | (n = 144) | ||

| Age, years | 37.5 ± 13.2 (20–64) | 38.2 ± 12.0 (20–64) | 0.642 |

| Gender, female | 117 (81.3) | 115 (79.9) | 0.882 |

| Education, years | 13.8 ± 2.5 (6–18) | 14.1 ± 2.3 (6–18) | 0.242 |

| Employment, yes | 63 (43.8) | 74 (51.4) | 0.238 |

| Household income, | 108 (75.0) | 114 (79.2) | 0.483 |

| ≥3 million KRW/month | |||

| BMI | 22.4 ± 3.4 (15–35) | 22.5 ± 3.1 (15–33) | 0.698 |

| Age at onset, years | 27.5 ± 11.2 (10–58) | ||

| Disease duration, years | 10.0 ± 8.5 (0.3–42) | ||

| Type of migraine | |||

| Migraine with aura | 15 (10.4) | ||

| Migraine without aura | 129 (89.6) | ||

| Migraine chronicity | |||

| EM | 88 (61.1) | ||

| CM | 56 (38.9) | ||

| Family history of migraine | 89 (61.8) | ||

| MOH | 11 (7.6) | ||

| VAS | 7.5 ± 2.3 (0–10) | ||

| Associated symptoms | |||

| Nausea/vomiting | 121 (84.0) | ||

| Photophobia | 69 (47.9) | ||

| Phonophobia | 82 (56.9) | ||

| Osmophobia | 73 (50.7) | ||

| Allodynia | 29 (20.1) | ||

| MIDAS, days | 23.4 ± 26.3 (0–120) | ||

| PHQ-9 | 6.0 ± 4.9 (0–24) | ||

| GAD-7 | 4.6 ± 4.5 (0–21) | ||

| ESS | 5.6 ± 4.0 (0–20) | ||

| ISI | 8.1 ± 6.0 (0–26) | ||

| MINI, suicidality | 35 (24.3) | ||

KRW Korean Won, BMI Body Mass Index, EM episodic migraine, CM chronic migraine, MOH medication overuse headache, VAS visual analog scale, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment Scale, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, ESS Epworth Sleepiness Scale, ISI Insomnia Severity Index, MINI Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview—Plus Version 5.0.0

*Student’s t-test or chi-squared test was applied

The degree of aggression in migraine patients compared with healthy controls is documented in Table 2. Mean scores of the overall AQ, anger, and hostility were significantly higher in migraine patients than the score of the controls (p < 0.05 for the overall AQ score, p < 0.01 for anger and hostility). In CM patients, mean scores of the overall AQ, physical aggression, anger, and hostility were significantly higher than the scores of the controls (p < 0.05 for physical aggression, p < 0.01 for the overall AQ score, anger and hostility). On the other hand, all scores of the AQ in episodic migraine (EM) patients were not different from the scores of the controls.

Table 2.

Aggression in migraine patients compared with healthy controls

| Mean ± SD (range) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migraine patients | EM | CM | Healthy controls | |

| (n = 144) | (n = 88) | (n = 56) | (n = 144) | |

| Overall AQ | 48.9 ± 12.6 (31–105)a | 45.3 ± 10.3 (31–76) | 54.6 ± 13.8 (33–105)b | 45.8 ± 8.5 (27–71) |

| Physical aggression | 13.6 ± 4.2 (9–33) | 12.7 ± 3.2 (9–26) | 15.2 ± 5.0 (9–33)a | 13.6 ± 3.6 (9–25) |

| Verbal aggression | 9.9 ± 3.2 (5–20) | 9.6 ± 3.2 (5–19) | 10.3 ± 3.1 (5–20) | 9.9 ± 2.7 (5–20) |

| Anger | 11.6 ± 4.0 (5–24)b | 10.3 ± 3.3 (5–22) | 13.6 ± 4.3 (6–24)b | 10.2 ± 2.6 (5–16) |

| Hostility | 13.7 ± 5.2 (8–35)b | 12.7 ± 4.3 (8–30) | 15.4 ± 6.0 (8–35)b | 12.2 ± 2.7 (8–22) |

EM episodic migraine, CM chronic migraine, AQ Aggression questionnaire

Student’s t-test was conducted for the comparison between migraine patients and controls, aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01

Factors associated with the overall AQ score by univariate analyses in migraine patients are described in Table 3. Patients with CM, a higher headache intensity, and a higher score on the PHQ-9, the GAD-7, the ESS, and the ISI were associated with higher overall AQ scores. Major determinants for the overall AQ score by multivariate analyses in migraine patients are shown in Table 4. The strongest determinants was anxiety (ß = 0.395, p < 0.001), followed by headache intensity (ß = 0.180, p = 0.016) and CM (ß = − 0.165, p = 0.037).

Table 3.

Factors associated with the overall AQ score by univariate analyses in migraine patients

| Variable | P value (r)* |

|---|---|

| Migraine chronicity | < 0.001 (− 0.363) |

| VAS | < 0.001 (0.303) |

| PHQ-9 | < 0.001 (0.432) |

| GAD-7 | < 0.001 (0.490) |

| ESS | 0.001 (0.267) |

| ISI | < 0.001 (0.294) |

AQ Aggression Questionnaire, BMI Body Mass Index, MOH medication overuse headache, VAS visual analog scale, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment Scale, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, ESS Epworth Sleepiness Scale, ISI Insomnia Severity Index

*Pearson’s correlation was applied

Table 4.

Major determinants for the overall AQ score by multivariate analyses in migraine patients

| Variable | Standardized | P value | Collinearity | Adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| coefficients (ß) | (VIF) | R 2 | ||

| Constant | < 0.001 | 0.293 | ||

| GAD-7 | 0.395 | < 0.001 | 1.168 | |

| VAS | 0.180 | 0.016 | 1.103 | |

| Migraine chronicity | −0.165 | 0.037 | 1.231 |

AQ Aggression Questionnaire, GAD-7 Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7, VAS visual analog scale

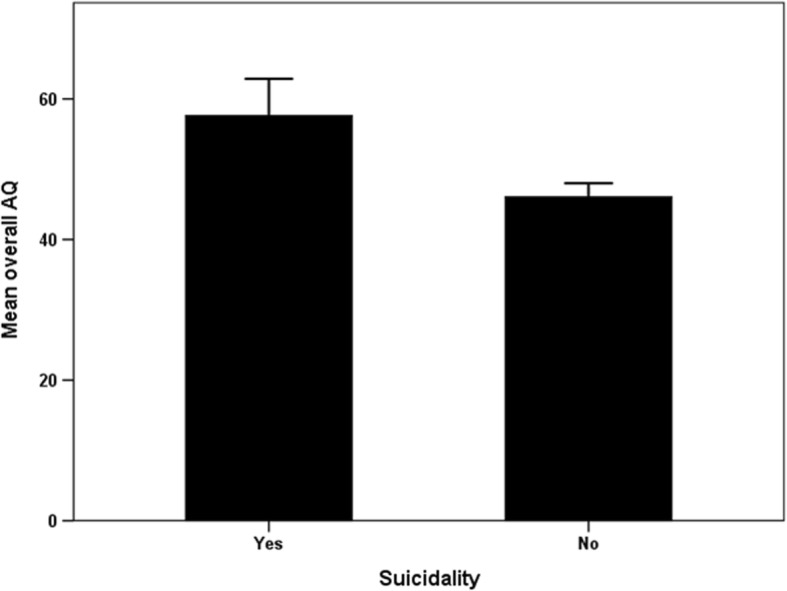

Of patients showing suicidality (n = 35), 23 patients (68.6%) had a low level of suicide risk, 7 patients (20.0%) had a moderate level of suicide risk, and 4 patients (11.4%) had a high level of suicide risk. A lifetime suicide attempt was noted in 16 patients (45.7%). Regarding to migraine chronicity, the frequency of suicidality in CM patients (24 of 56 patients, 42.9%) was significantly higher than the frequency of suicidality in EM patients (11 of 88 patients, 12.5%) (p < 0.001). Mean scores of the overall AQ with respect to the existence of suicidality are illustrated in Fig. 1. Mean score of the overall AQ was significantly higher in patients having suicidality than patients with no suicidality (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the overall AQ score between patients having suicidality (n = 35) and those having no suicidality (n = 109). Mean score of the overall AQ was significantly higher in patients having suicidality than the mean score of patients having no suicidality (p < 0.001). Suicidality was determined by the MINI. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. AQ: Aggression Questionnaire, MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview—Plus Version 5.0.0

Discussion

Although migraine seems to be associated with aggression, there are a few studies to examine the clinical significance of aggression in migraine patients. In a hospital-based study, migraine patients and tension-type headache (TTH) patients had a higher degree of hostility than healthy controls [27]. Migraine patients and TTH patients showed a significantly higher level of angry temperament and angry reaction [28]. Difficulty in anger management with a tendency to hypercontrol was shown in migraine patients compared with healthy controls [29]. In a multicenter study, self-aggression in migraine patients compared to healthy controls showed a trend towards higher scores due to a small sample size [30]. It was correlated with the level of headache-related disability. For CM patients, the frequency of passive-aggressive personality disorder was higher than the frequency of this disorder in healthy controls, and personality disorders were correlated with the MIDAS scores [31]. Taken together, these results seem to suggest that migraine patients are more likely to have aggression and to experience disability than healthy controls. Although we reported a higher level of aggression in migraine patients than controls, this appearance was confined to CM patients. Moreover, the degree of aggression was not correlated with the MIDAS score. Therefore, we suggest aggression may be a specific feature for CM regardless of headache-related disability.

We found CM, headache intensity, depression, anxiety, daytime somnolence, and insomnia as associated factors for aggression. However, major determinants for aggression were anxiety, headache intensity, and CM. That means depression and sleep problems are not critical for aggression after controlling for anxiety, headache intensity, and CM. It is well known that CM patients are more likely to have depression and sleep problems than EM patients [4, 32], and severe headache can elicit depression and sleep problems [33]. The reason why anxiety was the strongest factor for aggression may be attributed to a common pathology underlying anxiety and aggression. Amygdala function is known to play an important role in anxiety [34] and is also associated with emotional control processes and aggression [9]. Therefore, it is possible to suppose that anxious persons can also be aggressive. The contribution of headache intensity to aggression can be explained by the General Aggression Model [14]. We presume that recurrent severe headache as a situational factor is likely to induce aggression in migraine patients.

We do not consider anxiety and headache intensity as migraine-specific factors for aggression. These factors can be associated with aggression in other types of headache. For example, patients with cluster headaches and accompanying severe pain have been reported to have aggression [30]. On the other hand, migraine chronicity is likely to be a specific situation for provoking aggression in migraine patients. Recently, a high-resolution functional MRI study demonstrated that the hypothalamus played a crucial role in the pathophysiology of migraine chronification [35]. Because the hypothalamus is also an important pathogenic substrate for aggression, we presume aggression is likely to be a phenomenon of migraine chronicity. Further neuroimaging studies are needed to clarify the relationship between aggression and CM.

Migraine has been known to be associated with suicidality. In a systemic review of the literature, a modest positive association between migraine and suicidal ideation was found [16]. We also observed through psychiatric interviews, a high proportion (24.3%) of migraine patients had suicidal ideation or attempt. Because suicidality is closely related to mortality in mental disorders, it is important to identify risk factors for suicidality to lessen mortality. We found the overall AQ score was higher in patients with suicidality than those without suicidality. That means aggression may reflect suicidal ideation or attempt in migraine patients. Actually, in a genetic study of women with CM, those with affective temperaments including irritability were more likely to exhibit suicidal behavior [36]. Therefore, asking about aggressive feelings or behaviors in migraine patients will be another option for identifying suicidality, especially if clinicians feel uncomfortable asking them about suicidal ideation or attempts directly.

Our study has some limitations. First, subjects in a single tertiary hospital were investigated. Therefore, our results cannot be generalized. Second, this was a cross-sectional study. Causal relationships between variables could not be confirmed. We already presumed aggression was likely to be a phenomenon related to migraine chronicity due to sharing of pathologic substrates. However, it is also possible that aggression affected by recurrent migraine attack may induce functional changes of the brain and subsequently elicit CM. A longitudinal study is recommended to verify the causal relationship. Third, the suicidality module in the MINI includes questions about suicidal ideation and harming oneself. These do not always reflect actually committing suicide and increasing mortality. However, because aggression is a facilitator for aggravating suicidality levels to highly lethal suicidal attempts [15], further studies should be conducted to elucidate a role of aggression in the mortality of migraine patients.

Conclusions

We found that the overall AQ score was higher in migraine patients than controls. Patients with CM had a higher overall AQ score and physical aggression, anger, and hostility subscale scores than controls. On the other hand, all AQ scores in patients with EM were not different from those of controls. Aggression is likely to be a common feature in CM. Major determinants for the overall AQ score were anxiety, headache intensity, and CM. Patients who had suicidality showed a higher overall AQ score than those without suicidality. Therefore, the recognition and proper management of aggression will be helpful for reducing mortality in CM patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ju-Hui Lee, a neuropsychologist, for her help with the completion of self-report questionnaires and the psychiatric interview.

Availability of data and materials

Part of the dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available on request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AQ

Aggression Questionnaire

- ASC-12

12-item Allodynia Symptom Checklist

- BMI

body mass index

- BPD

borderline personality disorder

- CM

chronic migraine

- EM

episodic migraine

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- GAD

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- ISI

insomnia severity index

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- MIDAS

Migraine Disability Assessment Scale

- MINI

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

- MOH

medication overuse headache

- PHQ

Patient Health Questionnaire

- TTH

tension-type headache

- VAS

Visual Analog Scale

Authors’ contributions

SPP took part in the design of the study and contributed to data collection. SPP participated in the writing of the manuscript. JGS contributed to data analysis. All authors agreed to accept equal responsibility for the accuracy of the content of the paper. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University Hospital approved the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sung-Pa Park, Email: sppark@mail.knu.ac.kr.

Jong-Geun Seo, Email: jonggeun.seo@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American migraine study II. Headache. 2001;41:646–657. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minen MT, Begasse De Dhaem O, Powers S, Schwedt TJ, Lipton R, Silbersweig D. Migraine and its psychiatric comorbidities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:741–749. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seo JG, Park SP. Significance of fatigue in patients with migraine. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;50:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SY, Park SP. The role of headache chronicity among predictors contributing to quality of life in patients with migraine: a hospital-based study. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:68. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YH, Yoon SJ, Kim A, Seo H, Ko S. Health performance and challenges in Korea: a review of the global burden of disease study 2013. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(Suppl 2):S114–S120. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.S2.S114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:27–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassard J, Teoh KRH, Visockaite G, Dewe P, Cox T. The financial burden of psychosocial workplace aggression: a systematic review of cost-of-illness studies. Work Stress. 2018;32:6–32. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2017.1380726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramirez JM, Andreu JM. Aggression, and some related psychological constructs (anger, hostility, and impulsivity); some comments from a research project. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:276–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, Everitt BJ. Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:321–352. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(02)00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lane SD, Kjome KL, Moeller FG. Neuropsychiatry of aggression. Neurol Clin. 2011;29:49–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis RE, Smitherman TA, Baskin SM. Personality traits, personality disorders, and migraine: a review. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(Suppl 1):S7–S10. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silberstein S, Lipton R, Breslau N. Migraine: association with personality characteristics and psychopathology. Cephalalgia. 1995;15:358–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-29821995.1505358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leichsenring F, Leibing E, Kruse J, New AS, Leweke F. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet. 2011;377:74–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61422-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen JJ, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. The general aggression model. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;19:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gvion Y, Levi-Belz Y. Serious suicide attempts: systematic review of psychological risk factors. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:56. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman LE, Gelaye B, Bain PA, Williams MA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of migraine and suicidal ideation. Clin J Pain. 2017;33:659–665. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Ashina S, Burstein R, Silberstein S, Reed ML, Serrano D, Stewart WF; American Migraine Prevalence Prevention Advisory Group Cutaneous allodynia in the migraine population. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:148–158. doi: 10.1002/ana.21211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo SG, Kwon SM. Validation study of the Korean version of the aggression questionnaire. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2002;21:487–501. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee HS, Chung CS, Song HJ, Park HS. The reliability and validity of the MIDAS (migraine disability assessment) questionnaire for Korean migraine sufferers. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 2000;18:287–291. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo JG, Park SP. Validation of the patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and PHQ-2 in patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:65. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0552-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seo JG, Park SP. Validation of the generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and GAD-2 in patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:97. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0583-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho YW, Lee JH, Son HK, Lee SH, Shin C, Johns MW. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep Breath. 2011;15:377–384. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho YW, Song ML, Morin CM. Validation of a Korean version of the insomnia severity index. J Clin Neurol. 2014;10:210–215. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2014.10.3.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoo SW, Kim YS, Noh JS, Oh KS, Kim CH, Namkoong K, Chae JH, Lee GC, Jeon SI, Min KJ, Oh DJ, Koo EJ, Park HJ, Choi YH, Kim SJ. Validity of Korean version of the MINI-international neuropsychiatric interview. Anxiety and Mood. 2006;2:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452–459. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bag B, Hacihasanoglu R, Tufekci FG. Examination of anxiety, hostility and psychiatric disorders in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:515–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perozzo P, Savi L, Castelli L, Valfrè W, Lo Giudice R, Gentile S, Rainero I, Pinessi L. Anger and emotional distress in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. J Headache Pain. 2005;6:392–399. doi: 10.1007/s10194-005-0240-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbate-Daga G, Fassino S, Lo Giudice R, Rainero I, Gramaglia C, Marech L, Amianto F, Gentile S, Pinessi L. Anger, depression and personality dimensions in patients with migraine without aura. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:122–128. doi: 10.1159/000097971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luerding R, Henkel K, Gaul C, Dresler T, Lindwurm A, Paelecke-Habermann Y, Leinisch E, Jürgens TP (2012) Aggressiveness in different presentations of cluster headache: results from a controlled multicentric study. 32:528–536 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Kayhan F, Ilik F. Prevalence of personality disorders in patients with chronic migraine. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;68:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang CP, Wang SJ. Sleep in patients with chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21:39. doi: 10.1007/s11916-017-0641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Fernández-Muñoz JJ, Palacios-Ceña M, Parás-Bravo P, Cigarán-Méndez M, Navarro-Pardo E. Sleep disturbances in tension-type headache and migraine. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2017;11:1756285617745444. doi: 10.1177/1756285617745444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:493–505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulte LH, Allers A, May A. Hypothalamus as a mediator of chronic migraine: evidence from high-resolution fMRI. Neurology. 2017;88:2011–2016. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serafini G, Pompili M, Innamorati M, Gentile G, Borro M, Lamis DA, Lala N, Negro A, Simmaco M, Girardi P, Martelletti P. Gene variants with suicidal risk in a sample of subjects with chronic migraine and affective temperamental dysregulation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:1389–1398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Part of the dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available on request to the corresponding author.