Abstract

Background & Aims

Tachykinins are involved in physiological and pathophysiological mechanisms in the gastrointestinal tract. The major sources of tachykinins in the gut are intrinsic enteric neurons in the enteric nervous system and extrinsic nerve fibers from the dorsal root and vagal ganglia. Although tachykinins are important mediators in the enteric nervous system, how they contribute to neuroinflammation through effects on neurons and glia is not fully understood. Here, we tested the hypothesis that tachykinins contribute to enteric neuroinflammation through mechanisms that involve intercellular neuron-glia signaling.

Methods

We used immunohistochemistry and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, and studied cellular activity using transient-receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1)tm1(cre)Bbm/J::Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd and Sox10CreERT2::Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd mice or Fluo-4. We used the 2,4-di-nitrobenzene sulfonic acid (DNBS) model of colitis to study neuroinflammation, glial reactivity, and neurogenic contractility. We used Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice to selectively study glial transcriptional changes.

Results

Tachykinins are expressed predominantly by intrinsic neuronal varicosities whereas neurokinin-2 receptors (NK2Rs) are expressed predominantly by enteric neurons and TRPV1-positive neuronal varicosities. Stimulation of NK2Rs drives responses in neuronal varicosities that are propagated to enteric glia and neurons. Antagonizing NK2R signaling enhanced recovery from colitis and prevented the development of reactive gliosis, neuroinflammation, and enhanced neuronal contractions. Inflammation drove changes in enteric glial gene expression and function, and antagonizing NK2R signaling mitigated these changes. Neurokinin A–induced neurodegeneration requires glial connexin-43 hemichannel activity.

Conclusions

Our results show that tachykinins drive enteric neuroinflammation through a multicellular cascade involving enteric neurons, TRPV1-positive neuronal varicosities, and enteric glia. Therapies targeting components of this pathway could broadly benefit the treatment of dysmotility and pain after acute inflammation in the intestine.

Keywords: Enteric Nervous System, Neurokinins, Glia, Colitis

Abbreviations used in this paper: BzATP, 2’(3’)-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5’-triphosphate triethylammonium salt; Ca2+, calcium; Cx43, connexin-43; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium; DNBS, dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid; EFS, electrical field stimulation; ENS, enteric nervous system; FGID, functional gastrointestinal disorder; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; GI, gastrointestinal; HA, hemagglutinin; IPAN, intrinsic primarily afferent neuron; LMMP, longitudinal muscle–myenteric plexus; mRNA, messenger RNA; MSU, Michigan State University; NK1R, neurokinin-1 receptor; NK2R, neurokinin-2 receptor; NKA, neurokinin A; SP, substance P; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid-1

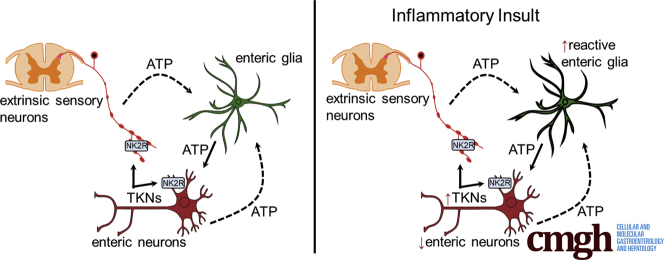

Graphical abstract

See editorial on page 354.

Summary.

Tachykinins are involved in the physiological regulation of gastrointestinal functions and contribute to gastrointestinal pathophysiology. The mechanisms mediating tachykinin signaling in the enteric nervous system are poorly understood. This study defines specific anatomic sites at which tachykinins activate signaling in neurons and glia and show that inhibition of such signaling promotes resolution of colitis and neuroinflammation.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are highly prevalent disorders characterized by dysmotility and visceral hypersensitivity.1 Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common FGID, affecting approximately 11% of the worldwide population.2 Broad abnormalities in the brain–gut axis contribute to the pain component of FGIDs,3 but it is clear that changes in gut motility are driven primarily by alterations to the enteric nervous system (ENS).4 The ENS is a complex network of enteric neurons and glia embedded within the gut wall that provides local control over reflexive gut functions such as fluid exchange across the mucosa, local blood flow, and patterns of motility.5 Inflammation can disrupt the control of these gastrointestinal (GI) reflexes by altering both the function and survival of enteric neurons that then contribute to the development of FGIDs.6 Despite having a clear involvement in the pathogenesis of inflammation, the mechanisms that drive and sustain ENS dysfunction remain unresolved.

Inflammation is a particularly potent driving force for the induction of neuroplasticity in the periphery and contributes to both altered motility and the sensitization of peripheral nociceptors in functional GI disorders.6, 7 Histamine, proteases, polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolites, and tachykinins now are recognized as some of the key inflammatory mediators that modify peripheral neurons in functional GI disorders.8, 9, 10 Tachykinins are particularly important because of the prominent roles that they play in both pain transmission and intestinal motility.11, 12

Tachykinins, including substance P (SP), neurokinin A (NKA), and neurokinin B, are important neuropeptide mediators that contribute to GI functions such as motility and secretion, and pathophysiological processes that contribute to gut inflammation and visceral pain.11, 12 Enteric neurons are the major source of tachykinins in the gut, followed by innervating nerve fibers from the dorsal root and vagal ganglia and, to a lesser extent, immune and enterochromaffin cells.13 There are at least 8 types of tachykinin-immunoreactive neurons in the ENS and the majority of these are intrinsic primarily afferent neurons (IPANs), oral and aboral projecting interneurons, and motor neurons projecting to the GI smooth muscle.13 The effects of SP, NKA, and neurokinin B are mediated preferentially through activation of neurokinin-1 receptors (NK1R), neurokinin-2 receptors (NK2R), and neurokinin-3 receptors, (NK3R) respectively.14 Physiologically, tachykinins function as co-neurotransmitters of excitatory neurons innervating the muscle,15 serve as transmitters of the ascending contractile component of peristaltic reflexes,16 are involved in neuroneuronal transmission between IPANs and interneurons,12 and have been proposed to be involved in the transmission of sensory information from the gut to the central nervous system.13 During inflammation, tachykinins induce secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in the mucosa,17 contribute to secretion associated with inflammation,18 and increased NKA contributes to visceral hypersensitivity in rats.19 In addition, tachykinin levels are increased in the colon and serum of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).20, 21

Given their important roles in gut physiology and disease, there is increasing interest in targeting tachykinin receptors for therapeutic benefit. Importantly, antagonists of NK2Rs reduce visceral pain associated with inflammation in rats.19 Recent success in clinical trials with the drug ibodutant, a NK2R antagonist, show that tachykinins acting through NK2Rs play an important role in the sustained pathophysiology of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.22 Although these findings are exciting, the mechanisms underlying the beneficial actions of NK2R antagonists in FGIDs still are poorly understood.

Here, we tested the hypothesis that the effects of tachykinins on neuroinflammation are mediated, in part, by signaling between enteric neurons, glia, and nociceptors in the ENS. We tested our hypothesis by studying the expression and function of tachykinin peptides and receptors with immunohistochemistry, molecular biology, and calcium (Ca2+) imaging. We found that SP and NKA are expressed predominantly by neuronal varicosities in close proximity to enteric glia, and NK2Rs are expressed predominantly by extrinsic and intrinsic neuronal varicosities surrounding enteric glia. Stimulation of NK2Rs with NKA produces robust activity in transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1)-positive varicosities, enteric glia, and enteric neurons throughout the myenteric plexus, and the glial response to NKA is critically dependent on the activation of both NK2Rs and connexin-43 (Cx43) hemichannels. We further tested our hypothesis by assessing the effects of NK2R antagonism in an in vivo model of colitis and found that NK2R antagonism protects against glial reactivity and enteric neurodegeneration associated with colitis. Collectively, our results show that the activation of NK2Rs is a critical mechanism that drives neuron-to-glia signaling and that reducing enteric neuroinflammation and glial reactivity likely contributes to the beneficial effects of NK2R antagonist drugs during inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Declaration of Animal Use Approval

All work involving animals was conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Michigan State University (MSU).

Animals

Male and female C57BL/6 mice between 8 and 10 weeks of age were used for experiments unless stated otherwise (Charles River Laboratories, Hollister, CA). All mice were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle in a temperature-controlled environment with access to food and water ad libitum. Transgenic mice expressing the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP5g in enteric glia (Sox10CreERT2::Polr2atm1[CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato]Tvrd) were bred in-house and were generated as previously described23 by crossing Sox10::CreERT2+/- mice (a gift from Dr Vassilis Pachnis, The Francis Crick Institute, London, England) with Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd mice [PC::G5-tdT (024477; RRID: IMSR_JAX:024477; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME)]. Transgenic mice expressing the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP5g in sensory neurons (TRPV1tm1[cre]Bbm/J::Polr2atm1[CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato]Tvrd) were bred in-house and were generated by crossing B6.129-Trpv1tm1[cre]Bbm/J mice [TRPV1Cre (017769; RRID: IMSR_JAX:017769; Jackson Laboratory)] with Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd mice. Mice with a tamoxifen-sensitive deletion of Cx43 in enteric glia (Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Cx43f/f) were also bred in-house and generated as previously described24 by crossing Sox10::CreERT2 mice with Gja1tm1Dlg mice [Cx43f/f (008039; RRID: IMSR_JAX:008039; Jackson Laboratory)]. Mice with a tamoxifen-sensitive targeted mutation of the ribosomal protein L22 (Rpl22) in enteric glia (Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice) also were bred in-house and generated by crossing Sox10::CreERT2 mice with Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice [RiboTag (011029; RRID: IMSR_JAX:011029; Jackson Laboratory)]. Double-transgenic mice were maintained as hemizygous for Cre (TRPV1Cre or Sox10::CreERT2+/-) and homozygous for the floxed allele (Polr2atm1[CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato]Tvrd or Cx43f/f). Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice were maintained as hemizygous for both Cre (Sox10::CreERT2+/-) and the floxed allele (Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J). CreERT2 activity was induced in Sox10CreERT2::Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd mice by intraperitoneal injections of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (0.1 mg/g) every 12 hours for 2 days, 7 days before conducting experiments. CreERT2 activity was induced in Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Cx43f/f and Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice by feeding the animals with chow containing tamoxifen citrate (400 mg/kg) for 2 weeks followed by 1 week of normal chow before use. Genotyping was performed by the Research Technology Support Facility Genomics Core at MSU and Transnetyx (Cordova, TN).

Whole-Mount Immunohistochemistry

Longitudinal muscle–myenteric plexus (LMMP) whole-mount preparations were microdissected from mouse colonic tissue preserved in Zamboni’s fixative. Processing of LMMPs via immunohistochemistry was conducted as described previously,25 with the primary and secondary antibodies listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Briefly, LMMP preparations underwent three 10-minute washes in 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in phosphate-buffered saline followed by a 45-minute incubation in blocking solution containing 4% normal goat or donkey serum, 0.4% Triton X-100, and 1% bovine serum in phosphate-buffered saline. Preparations were incubated with primary antibodies for 48 hours at 4°C and secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature before mounting. Antibody specificity was confirmed by preadsorption with the corresponding control peptides. Fluorescent labeling was visualized by confocal imaging through the Plan-Apochromat 60× oil immersion objective (1.42 numeric aperture) of an inverted Olympus Fluoview FV1000 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Table 1.

Primary Antibodies Used

| Antibody | Source | Dilution | Catalog number | Resource ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken anti-GFAP | Abcam | 1:1000 | AB4674 | AB_304558 |

| Rabbit anti-NK1R | Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel | 1:500 | ATR-001 | AB_11219139 |

| Rabbit anti-NK2R | Alomone Labs | 1:500 | ATR-002 | AB_2341078 |

| Biotinylated mouse anti-human HuC/D | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA | 1:200 | A21272 | AB_2535822 |

| Rabbit anti-HA–Tag (C29F4) | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA | 1:500 | 3724 | AB_1549585 |

| DsRed polyclonal | Clontech Laboratories | 1:1000 | 632496 | AB_10015246 |

| Rabbit anti-NKA | Abcam | 1:100 | AB48598 | AB_881037 |

| Guinea pig anti-SP | Abcam | 1:200 | AB106291 | AB_10864733 |

Table 2.

Secondary Antibodies Used

| Antibody | Source | Dilution | Catalog number | Resource ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor–594 donkey anti-guinea pig | Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA | 1:400 | 706-585-148 | AB_2340474 |

| Alexa Fluor–568 goat anti-rabbit | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA | 1:400 | A-11036 | AB_2534094 |

| Alexa Fluor–594–conjugated streptavidin | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:400 | 016-580-084 | AB_2337250 |

| Alexa Fluor–488 goat anti-chicken | Invitrogen | 1:400 | A-11039 | AB_2534096 |

| Dylight 405- conjugated streptavidin | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:400 | 016-470-084 | AB_2337248 |

| Alexa Fluor–488 donkey anti-guinea pig | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:400 | 706-545-148 | AB_2340472 |

| Alexa Fluor–488 donkey anti-rabbit | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:400 | 711-545-152 | AB_2313584 |

| Alexa Fluor–594 donkey anti-rabbit | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 1:400 | 711-585-152 | AB_2340621 |

Myenteric Whole-Mount Tissue Culture

LMMP whole-mount preparations were microdissected from mouse colons and incubated in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM/F-12) in 95% air, 5% CO2 at 37°C for 3 days. DMEM was changed daily. After 3 days, samples were fixed overnight in Zamboni’s fixative and processed for immunohistochemistry.

Ca2+ Imaging

LMMP whole-mount preparations were microdissected from mouse colons and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature in an enzyme mixture consisting of 150 U/mL collagenase type II and 1 U/mL dispase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Samples from C57BL/6 and Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Cx43f/f mice were loaded in the dark with 4 μmol/L Fluo-4 AM, 0.02% Pluronic F-127, and 200 μmol/L probenecid (Life Technologies) in DMEM/F-12 at 37°C.14 Images were acquired every 1–2 seconds through the 40× water immersion objective (LUMPlan N; numeric aperture, 0.8) of an upright Olympus BX51WI fixed-stage microscope (Olympus) using IQ3 software (Andor Technology Ltd, Belfast, UK), MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA), or NIS Elements (Nikon Instruments Inc, Melville, NY) software and a Neo sCMOS camera or a Zyla sCMOS camera (Andor Technology Ltd). We continually perfused whole mounts at 2–3 mL/min with buffer using a gravity flow perfusion system. Agonists were dissolved in buffer and bath applied for 30 seconds. Antagonists were dissolved in buffer and applied for either 20 minutes or 3 minutes before imaging.

Mouse Model of Colitis

Acute colitis was induced in male and female mice under isoflurane anesthesia by an enema of 0.1 mL of a solution containing 5 mg dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (DNBS) dissolved in 50% ethanol.26 Control animals were given enemas of saline. Subsets of mice received daily injections (intraperitoneally) of either 0.5 mg/kg GR 159897 (Tocris, Minneapolis, MN) in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide or 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide over 1, 3, 7, or 21 days beginning 24 hours before the induction of colitis. Mice were monitored closely and weight loss was recorded daily for the first week and once every other day for the following 2 weeks. Mice were killed at 24 hours, 48 hours, 7 days, or 3 weeks after induction of colitis. Macroscopic damage was recorded with an established scoring system.27

H&E Staining

Whole colonic tissue was collected 24 hours after induction of colitis. Tissue was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 72 hours. Sections (4-mm thick) were cut and rinsed in 50% ethanol for 24 hours. Tissue was processed and stained by the Investigative Histopathology Laboratory at MSU. For each section, the following parameters were scored: loss of mucosal architecture (0, 1, 2, or 3 from mild to severe); cell infiltration (0, none; 1, in muscularis mucosae; 2, in lamina propria/villi; or 3, in serosa); muscle thickening (0, <half of mucosal thickness; 1, half to a quarter of mucosal thickness; 2, mucosal thickness; or 3, full thickness); goblet cell depletion (0, absent; 1, present); and crypt abscess formation (0, absent; 1, present). The investigator performing histologic scoring was not blinded.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Colonic tissue was flash-frozen and total messenger RNA (mRNA) was isolated from 1 mg colon samples using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse-transcribed (High-Capacity Complementary DNA Reverse Transcript Kit; ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed using a TaqMan gene expression assay for mouse glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), TACR1, TACR2, and TAC1 genes (ThermoFisher). Amplification was performed by the MSU Research Technology Support Facility Genomics Core. Fold changes were calculated using the 2^(-delta delta CT) (2-∆∆CT)28 and normalized to levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Contractility Studies

Mouse colons were collected 7 days after the induction of colitis. Longitudinally-oriented muscle strips were mounted in organ baths, with one end attached to a force transducer (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA). Electrical field stimulation (EFS) was supplied by 2 platinum electrodes and a GRASS stimulator (S88; GRASS Telefactor, West Warwick, RI). Data were charted with LabChart 8 software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO) as described previously.29 Tissue segments were equilibrated for 20 minutes under 0.5-g initial tension. Neurogenic relaxations were studied in tissues precontracted with 5 μmol/L prostaglandin F2-α. Relaxations were induced when the contractile response to prostaglandin F2-α was stable for at least 5 minutes.

Glial Morphology Analysis

We assessed changes in glial morphology using the FIJI-Image J Simple Neurite Tracer plugin as described by Tavares et al.30 After immunostaining with GFAP, Z-stacks of confocal images were obtained using a 60× objective and 1-μm z-step interval. We analyzed a total of 16 enteric glia per treatment group. The total process length was determined by the sum of the length of individual paths reconstructed, process thickness was estimated from GFAP thickness provided by “Fill Out” analysis function, and morphology complexity was estimated from the number of intersections at each radial distance from the starting point provided by the Sholl analysis.

In Situ Model of Neuroinflammation

Enteric neuron death was driven as previously described.31 LMMP preparations were incubated with the P2X7R agonist 2’(3’)-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5’-triphosphate triethylammonium salt (BzATP) (300 μmol/L) or the NK2R agonist neurokinin-A (1 μmol/L) for 2 hours in 95% air, 5% CO2 at 37°C. LMMP preparations then were rinsed with fresh buffer, incubated for an additional 2 hours in buffer only, and fixed overnight in Zamboni’s fixative.

RiboTag Procedure

For RiboTag experiments, 8-week-old male and female Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice were used (n = 3 animals per experimental treatment). For immunoprecipitation, 200 μL of protein A/G magnetic beads (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, WA) were washed 3 times with 500 μL homogenization buffer before being coupled directly to 5 μL mouse monoclonal anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody (16B12, BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for 2 hours before they were added to homogenates.32 Homogenates were prepared as follows: colonic tissue from Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice was removed and placed in a bath containing DMEM/F-12 maintained at 4°C. Luminal contents were flushed, and a plastic rod (diameter, 3.2 mm) was inserted into the lumen. The LMMP was isolated from the underlying circular muscle by gently removing the mesenteric border and gently teasing away the LMMP using a cotton swab wet with cold DMEM/F-12.33 LMMP preparations then were flash-frozen before homogenization. Samples were homogenized using a rotor stator homogenizer in 1 mL ice-cold supplemented homogenization buffer adjusted for enteric use and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C.32, 34 Supernatants (800 μL) then were added directly to the antibody-coupled protein A/G magnetic beads and rotated overnight at 4°C. The following day, samples were placed in a magnet on ice and the pellet was washed 3 times with 800 μL high-salt buffer. After washing, 350 μL of Qiagen RLT buffer was added to the pellet, vortexed for 30s, and the supernatant was recovered and flash-frozen for RNA extraction.32 Total RNA was prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions using an RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen). RNA quality and sequencing were performed by LC Sciences (Houston, TX). Briefly, RNA quality was assessed by 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA peaks generated by the 2100 Bioanalyzer and the RNA 6000 Nano LabChip Kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). For sequencing, 1 ng mRNA was used to generate complementary DNA with the SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit for Sequencing (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA). Paired-end libraries were constructed from 1 ng complementary DNA using Nextera DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 4000 following the manufacturer’s specification. HISAT235 was used to map reads to mouse genomes assembled using StringTie.36 Low-quality bases and adapter-contaminated reads were removed using Cutadapt37 and LC Sciences in-house perl scripts. Sequence quality was confirmed using the web-based platform FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk). Transcript expression levels as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads were estimated using StringTie.36

Solutions

Live tissue was maintained in DMEM/F-12 nutrient mixture (Life Technologies) during collection and microdissection. Ca2+ imaging experiments were performed in modified Krebs buffer containing 121 mmol/L NaCl, 5.9 mmol/L KCl, 2.5 mmol/L CaCl2, 1.2 mmol/L MgCl2, 1.2 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 21.2 mmol/L NaHCO3, 1 mmol/L pyruvic acid, and 8 mmol/L glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Ribotag experiments were performed with homogenization buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mmol/L KCl, 12 mmol/L MgCl2, and 1% Nonidet P-40), supplemented homogenization buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mmol/L KCl, 12 mmol/L MgCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40, 100 μg/mL cycloheximide, 20 μL/mL Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (P8340; Sigma-Aldrich) 3 mg/mL heparin, 20 μL/mL SUPERase. In RNase inhibitor 20 U/μL (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol), and high-salt buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, 300 mmol/L KCl, 12 mmol/L MgCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40, 100 μg/mL cycloheximide, and 0.5 mmol/L 1,4-dithiothreitol).34

Chemicals and Reagents

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). GR 159897 (5-fluoro-3-[2-(4-methoxy-4-[([R]-phenylsulphinyl)methyl]-1-piperidinyl)ethyl]-1H-indole), MRS 2500 tetraammonium salt ([1R*,2S*]-4-[2-lodo-6-(methylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-[phosphonooxyl]bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-1-methanol dihydrogen phosphate ester tetraammonium salt), and CP 96345 ([2S,3S]-N-[2-methoxyphenyl]methyl-2-diphenylmethyl-1-azabicyclo[2.2.2]octan-2-amine) were purchased from Tocris. NKA was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The Cx43 mimetic peptide, 43Gap 26, was purchased from Anaspec (Fremont, CA). Di-nitro benzenesulfonic acid (2,4-dinitrobenzenesulfonic acid dihydrate) was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH).

Statistics

For Ca2+ imaging, traces represent the average change in fluorescence (ΔF/F) over time for individual cell responses. Integrated density was quantified using the measure function in ImageJ Software (version 1.48; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Neuron packing density was determined by counting the number of HuC/D-immunoreactive neurons per ganglionic area in 10 ganglia per LMMP preparation using the cell counter plug-in tool on ImageJ. For RNA sequencing, differential expression was determined in the R package Ballgown,38 with P < .005 considered statistically significant. All other results are presented as means ± SEM and statistically significant differences were determined using an analysis of variance or t test, as appropriate, with P < .05 considered statistically significant (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Nerve Processes in the Myenteric Plexus Contain Tachykinins

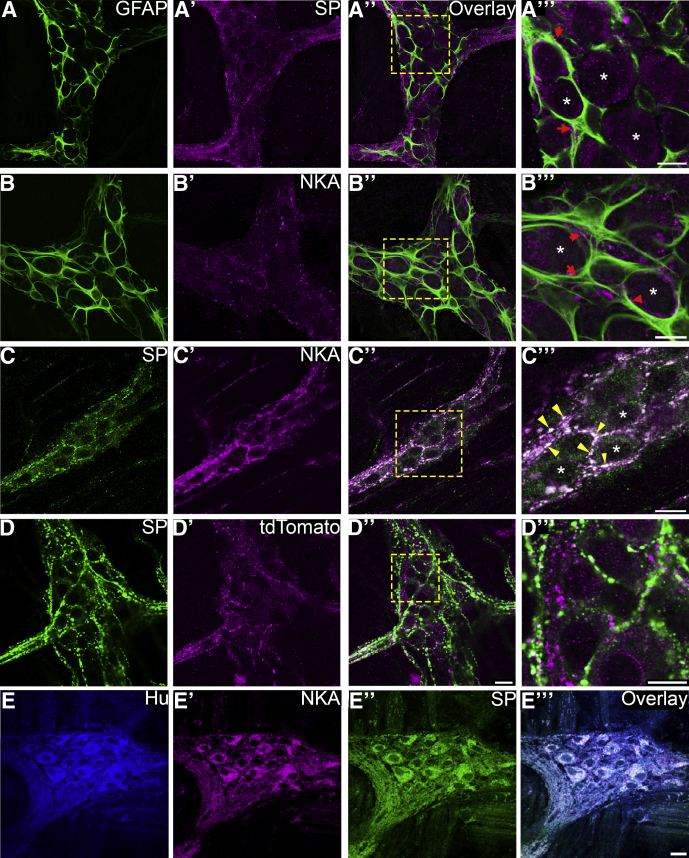

The ENS is the major source of intestinal tachykinins12, 13 and SP and NKA are the predominant tachykinins that exert control over motility, secretion, inflammation, and pain.11, 13 Although the cellular localization of SP is well characterized in the mouse ENS,39 the localization of NKA is less well defined. Dual-label immunohistochemistry on myenteric whole-mount tissue preparations shows that SP and NKA are localized to nerve varicosities in the myenteric plexus of the mouse colon (Figure 1). Varicosities containing SP (Figure 1A–A’’’) and NKA (Figure 1B–B’’’) are closely apposed to enteric glia in the myenteric plexus and dual-labeling with SP and NKA shows broad overlap between SP and NKA immunoreactivity (Figure 1C–C’’’), implying that these neurokinins are released by the same class of neurons. In addition, our results show that varicosities expressing SP are distinct from tdTomato-tagged TRPV1+ varicosities belonging to intrinsic and extrinsic sensory neurons in tissue samples from TRPV1tm1(cre)Bbm/J::Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd transgenic mice (Figure 1D–D’’). Varicosities expressing SP in the myenteric plexus of the mouse colon belong to enteric neurons and are intrinsic in origin.39, 40 To confirm varicosities expressing SP and NKA are of intrinsic origin, we cultured myenteric whole-mount tissue preparations for 3 days to remove extrinsic innervation. Under these conditions, we found that SP and NKA are still present in the myenteric plexus and observed robust expression in neuronal cell bodies (Figure 1E–E’’’). Together, these results show that NKA is localized to varicosities of myenteric neurons that also contain SP in the mouse colon and both NKA and SP are of intrinsic origin.

Figure 1.

Intrinsic varicosities surrounding enteric glia in the mouse myenteric plexus contain SP and NKA. Images are single optical sections (1 μm) through myenteric ganglia from the distal colons of mice. (A and B) Varicosities labeled with antibodies against SP (A’–A’’’, magenta) or NKA (B’–B’’’, magenta) surround GFAP-immunoreactive enteric glia (green, A and B). (C–C’’’) Immunoreactivities for SP (green) and (magenta) colocalize in the same population of varicosities. (D–D’’’) Varicosities labeled with antibodies against SP (green) do not colocalize with tdTomato-tagged TRPV1-positive varicosities (magenta). (A’’–D’’) Overlays of each combination are shown in A–D’’ and scale bar = 20 μm. Images are representative of labeling performed on tissue from a minimum of 3 mice. (A’’–D’’) Areas demarcated by the dashed boxes are enlarged in panels A’’’–D’’’. (A’’’–C’’’) Asterisks are placed within the nuclei of representative neurons. (A’’’–B’’’) Red arrowheads highlight varicosities closely associated with enteric glia. (C’’’) Yellow arrowheads highlight areas of colocalization. Scale bars in the enlarged images, (A’’’, B’’’, C’’’, D’’’) = 10 μm. (E–E’’’) LMMP tissue culture shows intrinsic expression of tachykinins in the myenteric plexus. Immunoreactivities for NKA (magenta, E’) and SP (green, E”) colocalize to neuronal cell bodies labeled with antibodies against HuC/D (blue, E). (E’’’) Scale bar = 20 μm and applies to E–E’’’.

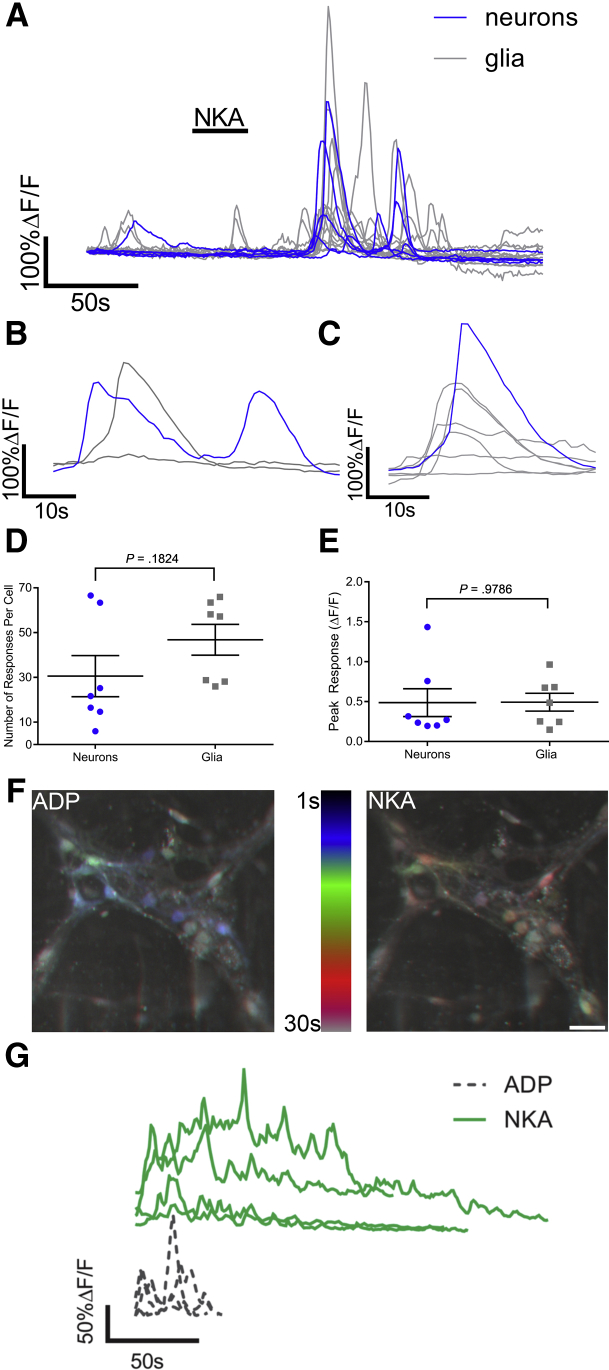

NKA Drives Neuron and Glial Ca2+ Responses

Neuronal SP release contributes to both central and peripheral neurogenic inflammation,12, 41 but the contribution of NKA to peripheral neurogenic inflammation is not understood. To understand how NKA release from enteric varicosities affects the activity of neurons and glia within the ENS, we used Ca2+ imaging in whole-mount preparations of myenteric plexus loaded with the Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-4AM. Challenging these samples with 1 μmol/L NKA, the preferred ligand for NK2Rs,14 drove Ca2+ responses in both enteric neurons and enteric glia (Figure 2A). However, the most striking effect was the stimulation of robust activity throughout the glial network that persisted for several minutes (Figure 2A and Supplementary Video 1). Analyzing the time course of neuron and glial responses showed that some enteric neurons responded before the surrounding glia (Figure 2B), whereas others responded directly after (Figure 2C). Individual neurons mounted numerous Ca2+ responses (average, 31 peaks; average magnitude, 0.48 ± 0.17 ΔF/F) (Figure 2D and E), whereas individual glial cells mounted numerous individual Ca2+ transients (average, 47 peaks; average magnitude, 0.49 ± 0.11 ΔF/F) (Figure 2D and E) that seemingly were stochastic. The seemingly random pattern of activity evoked by NKA is in stark contrast to glial responses to other neurotransmitters, such as purines, that drive uniform wave-like events through the glial network (Figure 2F and G).23, 42 This difference suggests that complex intercellular signaling mechanisms underlie the glial response to NKA.

Figure 2.

NKA drives Ca2+responses in both neurons and enteric glia. (A) Representative Ca2+ responses evoked by NKA in enteric neurons and glia. Gray traces show the responses of individual glial cells and blue traces show the responses of individual neurons. (B and C) Representative Ca2+ responses evoked by NKA in a single enteric neuron (blue traces) and the surrounding enteric glia (gray traces) showing examples of a (B) neuron response that proceeds glial responses and a (C) neuronal response that follows glial responses. (D) Number of responses and (E) peak response per neuron or glia when challenged with NKA (n = 7 cells from 2 mice; Student t test). (F) Temporal-code images of enteric glial responses to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) or NKA. Images are Z-projections of time series images from peak responses of enteric glia to ADP or NKA where cells that respond first are shown in blue (1 s after drug application) and cells that respond later are shown in red (30 s after drug application). Note that ADP responding cells respond faster, and at the same time compared with NKA responding cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. (G) Representative glial Ca2+ responses evoked by either ADP (dashed gray traces, bottom) or NKA (solid green traces, top).

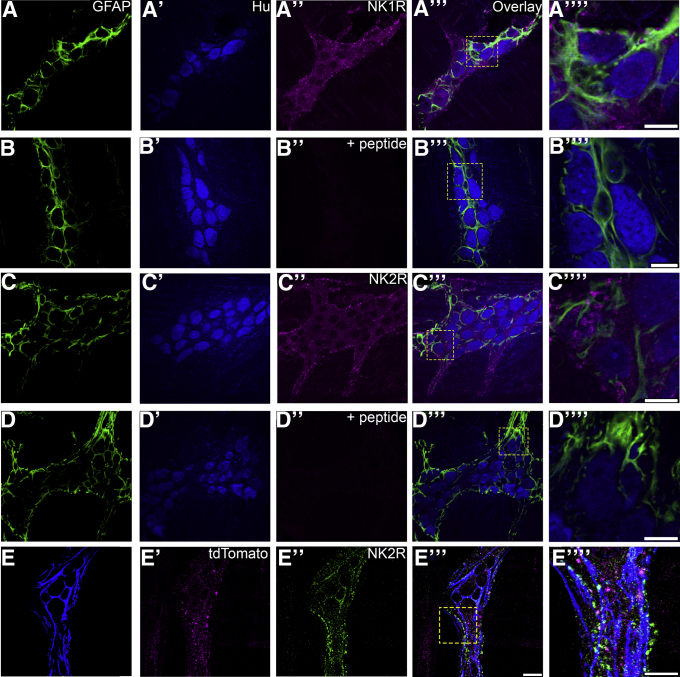

Given that NKA evokes responses in enteric glia and neurons, we tested if both enteric glia and neurons express the receptors required to detect NKA. To this end, we used triple-label immunohistochemistry with antibodies against GFAP and Hu to identify glia and neurons, respectively, in combination with antibodies against NK1Rs or NK2Rs (Figure 3). In agreement with previous studies, our results show that NK1Rs are localized predominantly to enteric neurons (Figure 3A–A’’’’).39 In addition, we found that NK2Rs are localized to enteric neuronal cell bodies and neuronal varicosities that surround enteric glia (Figure 3C–C’’’’). Surprisingly, NK2R immunoreactivity also colocalized with tdTomato-tagged TRPV1+ varicosities belonging to extrinsic and intrinsic sensory neurons in TRPV1tm1(cre)Bbm/J::Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd transgenic mice (Figure 3E–E’’’).

Figure 3.

NK1R expression is localized to enteric neuron cell bodies and varicosities whereas NK2R is expressed primarily by neuronal varicosities surrounding enteric glia. Images (confocal single optical planes, 1 μm) show triple-label immunohistochemistry for GFAP (green, A-D), Hu (blue, A’–D’), and either NK1R (magenta, A’’-B’’) or NK2R (magenta, C’’–D’’) in the distal colon myenteric plexus of mice. Preadsorption control is shown for NK1R (B–B’’’’) and NK2R (D–D’’’’). Images show triple-label immunohistochemistry for GFAP (green, E), tdTomato-tagged TRPV1-positive varicosities (blue, E’), and NK2R (magenta, E’’) in the distal colon myenteric plexus of mice. (A’’’–E’’’) Overlays of each combination. Areas demarked by the dashed boxes in A’’’–E’’’ are enlarged in panels A’’’’–E’’’’. (E’’’) Scale bar: 20 μm (applies to A–E’’’). Scale bars, 10 μm in the enlarged images (A’’’’, B’’’’, C’’’’, D’’’’, and E’’’’). Labeling is representative of experiments performed on a minimum of 3 mice.

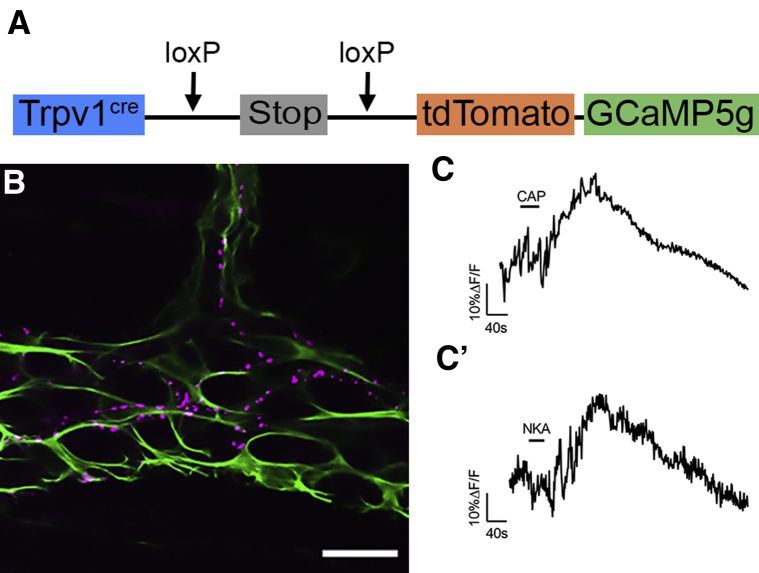

TRPV1-Positive Neuronal Varicosities Express Functional NK2Rs

Our immunohistochemical data described earlier suggest that NK2Rs are expressed by TRPV1-positive neuronal varicosities. TRPV1 is a well-known marker for extrinsic spinal afferent neurons in the intestine43, 44, 45 and also is expressed by intrinsic sensory enteric neurons.46 To test this hypothesis more directly, we generated mice that conditionally express the genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP5g in TRPV1-positive cells (TRPV1tm1[cre]Bbm/J::Polr2atm1[CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato]Tvrd mice) to specifically study the activity of this population of nerve fibers in the myenteric plexus (Figure 4A). Tachykinin-receptor activation primarily induces phospholipase C–mediated increases in intracellular Ca2+12,14 that are measured by changes in GCaMP fluorescence. Nerve fibers expressing tdTomato in this model traverse through the myenteric plexus and are closely apposed to enteric glia (Figure 4B). These nerve fibers showed robust responses to capsaicin (1 μmol/L), confirming that they do indeed express TRPV1 receptors (Figure 4C). Importantly, all TRPV1+ nerve fibers (n = 3–5 tissue preparations from 3 mice) responded to NKA (1 μmol/L) (Figure 4C’). Responses to NKA were on average 82% as large as responses to capsaicin in the same nerve fiber. Taken together with our earlier-described immunohistochemical and Ca2+ imaging data, these results show that NKA activates TRPV1+ nociceptors and drives glial and neuronal activity in the myenteric plexus.

Figure 4.

NKA drives Ca2+responses in TRPV1-positive neuronal varicosities. (A) Schematic of transgene containing the tdTomato-tagged genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator GCaMP5g driven by the TRPV1 promoter. (B) Confocal image of dual-label immunohistochemistry (single optical plane, 1 μm) for the tdTomato-tagged GCaMP5g (magenta) and enteric glia (GFAP, green) in the myenteric plexus of the TRPV1tm1(cre)Bbm/J::Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd mouse distal colon. Scale bar: 20 μm. (C–C’) Representative traces of average Ca2+ responses from TRPV1-positive neuronal fiber varicosities in response to (C) 1 μmol/L capsaicin (CAP) or (C’) 1 μmol/L NKA. Recordings were obtained from 3 to 5 tissue preparations from 3 mice.

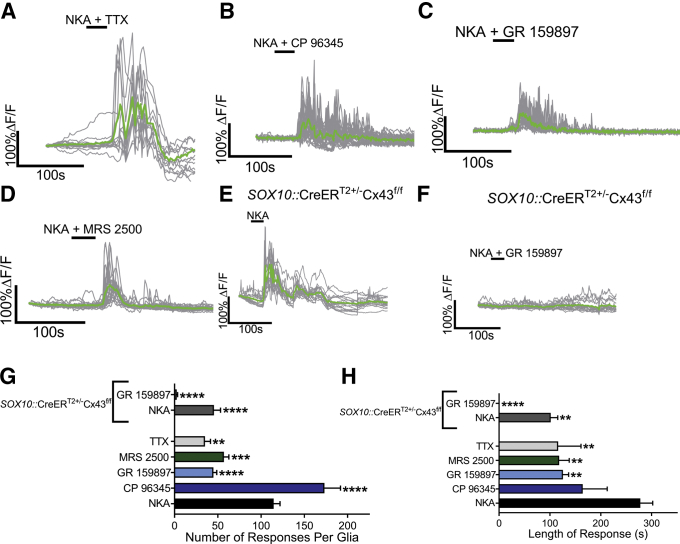

Intercellular Communication Between Nociceptors and Enteric Glia Driven by NKA Involves Neuronal Depolarization, Purines, and Glial Cx43 Activity

The expression of NK2Rs by TRPV1+ neuronal varicosities and the complex glial responses evoked by NKA suggest intercellular signaling between the 2 cell populations. We interrogated these mechanisms by using a number of selective drugs and mutant mice with targeted deletions in glia. In these experiments, we used Sox10CreERT2::Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd mice to selectively study glial Ca2+ responses23, 47 and avoid the confounding effects of other nearby cells. First, we used 1 μmol/L tetrodotoxin to test whether glial responses to NKA require reciprocal interactions with neurons that require neuronal depolarization. Although tetrodotoxin did not abolish the NKA-induced Ca2+ response (Figure 5A), it significantly reduced the number of responses per glia by 69% (P = .0038) (Figure 5G) and the duration of the response by 58% (P = .0054) (Figure 5H). Next, we tested the contribution of NK1Rs and NK2Rs by blocking their activity with the specific antagonists CP 96345 or GR 159897, respectively. NKA still reliably evoked glial Ca2+ responses in the presence of CP 96345 (10 μmol/L) (Figure 5B) that were similar in duration as NKA alone (164 vs 278 s) (Figure 5H). Interestingly, CP 96345 increased the number of responses per enteric glia compared with NKA alone by 51% (P = .0001) (Figure 5G). GR 159897 (1 μmol/L) alone reduced glial responses by 61% (P = .0001) (Figure 5G), but was not sufficient to completely abolish glial responses to NKA (Figure 5C). However, glial responses in the presence of GR 159897 were 55% shorter in duration (P = .0086) (Figure 5H).

Figure 5.

Glial Ca2+responses driven by NKA require the activation of NK2Rs and purinergic intercellular signaling mediated by Cx43. (A–D) Representative glial Ca2+ responses evoked by NKA in the presence of (A) tetrodotoxin, (B) the NK1R antagonist CP 96345, (C) the NK2R antagonist GR 159897, or (D) the P2Y1R antagonist MRS 2500. Gray traces show the responses of individual glial cells, and the averaged response of all glia within the ganglion is shown in the green trace. (E and F) Representative glial Ca2+ responses evoked by NKA in tissues from SOX10::CreERT2+/-Cx43f/f mice in the (E) absence or (F) presence of GR 159897. (G and H) Quantification of the effects of CP 96345, GR 159897, tetrodotoxin, MRS 2500, or ablation of glial Cx43 in SOX10::CreERT2+/-Cx43f/f mice on the (G) number and (H) length of response of glial Ca2+ responses induced by NKA (n = 15–33 glia from 3 to 5 mice; 1-way analysis of variance; **P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ****P < .0001). TTX, tetrodotoxin.

In prior work, we showed that intercellular neuron-to-glia communication involves the stimulation of glial P2Y1 receptors by purines released through neuronal channels.26, 31 To determine if purines contribute to glial Ca2+ responses evoked by NKA, we used MRS 2500 (10 μmol/L) to antagonize P2Y1Rs (Figure 5D). Although MRS 2500 did not abolish NKA-induced Ca2+ responses (Figure 5D), it significantly reduced the number of responses per glia by 50% (P = .0008) (Figure 5G) and the duration of glial responses by 57% (P = .0035) (Figure 5H).

Enteric glia use hemichannels composed of Cx43 for intercellular communication.42 To determine if intercellular signaling through Cx43 contributes to glial Ca2+ response evoked by NKA, we used a genetic model to selectively ablate glial Cx43 (SOX10::CreERT2+/-/Cx43f/f 22) and monitored glial activity evoked by NKA with Fluo-4AM. We still observed glial responses to NKA in samples from SOX10::CreERT2+/-/Cx43f/f mice (Figure 5E). However, similar to the effects described earlier with GR 159897, the number of responses per glia and duration of response were reduced by 60% (P = .0001) and 63% (P = .0027), respectively, in samples from SOX10::CreERT2+/-/Cx43f/f mice (Figure 5G and H). Applying GR 159897 to samples from SOX10::CreERT2+/-/Cx43f/f mice completely abolished glial responses to NKA (Figure 5F–H).

Together, these data show that the release of NKA from enteric neurons drives a multicellular signaling cascade through mechanisms that include the activation of NK2R+ neuronal varicosities and the subsequent recruitment of glial activity through the generation of extracellular purines and intercellular glial signaling involving Cx43 hemichannels.

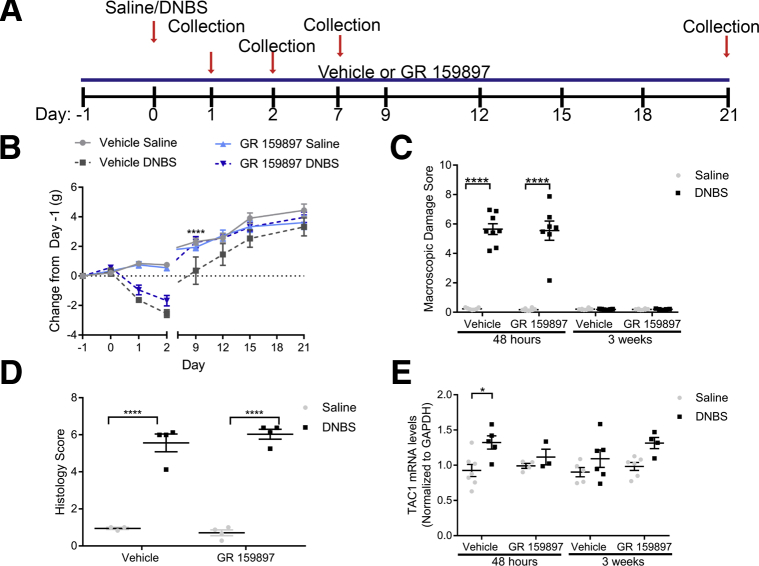

Contribution of NK2Rs to Inflammation During Colitis

Tachykinins are key mediators of neurogenic inflammation12, 41 and our data show that NKA drives the activation of glial mechanisms that contribute to neuroinflammation in the ENS.31 Therefore, we speculated that intercellular communication mediated by NKA could contribute to inflammatory processes in the intestine. We tested this hypothesis by assessing the effects of the NK2R antagonist GR 159897 (0.5 mg/kg intraperitoneally)48, 49 in the DNBS model of mouse colitis (Figure 6A). This is a well-characterized model that is widely used to study neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation in the ENS.50 Active inflammation in murine DNBS colitis peaks between days 2 and 3 and is completely resolved by 3 weeks.26 We found that blocking NK2Rs did not prevent body weight loss in mice at the peak of inflammation (Figure 6B), but mice treated with GR 159897 recovered from weight loss associated with inflammation within 9 days, whereas vehicle-treated mice did not recover until day 12, suggesting that GR 159897 accelerates the recovery from inflammation. Treatment with GR 159897 had no effect on the overall pattern of macroscopic damage to the colon in healthy or inflamed mice at peak inflammation or after recovery (Figure 6C), and no effect on histologic damage at the initiation of inflammation (Figure 6D). Interestingly, we observed that TAC1 mRNA levels are increased significantly by 43% in animals with active inflammation (P = .0368) (Figure 6E), which is consistent with changes observed in TAC1 mRNA levels in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.20 Given that TAC1 encodes NKA, the primary agonist of NK2Rs, this outcome strongly suggests that higher levels of NK2R agonists are present during active inflammation in the colon. Importantly, treatment with GR 159897 during active inflammation was sufficient to prevent the increase in TAC1 levels during colitis (Figure 6E). TAC1 mRNA levels had no statistical change at 3 weeks after induction of colitis (Figure 6E). Together, these results indicate that higher levels of NK2R agonists are present during active inflammation.

Figure 6.

Effects of the NK2R antagonist GR 159897 on colonic inflammation and TAC1 mRNA levels during acute colitis and recovery in mice. (A) Schematic representation of the timeline of treatments during colitis. (B) Weight loss pattern after induction of DNBS colitis in mice (n = 5–16 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; ∗∗∗P < .001; ****P < .0001). Note that inflamed mice treated with GR 159897 recover normal body weight sooner than inflamed mice treated with vehicle. (C) GR 159897 did not modify macroscopic damage to the colon at 48 hours or 3 weeks after induction of DNBS colitis in mice (n = 5–16 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; ****P < .0001). (D) GR 159897 did not modify histology scoring to the colon at 24 hours after induction of DNBS colitis in mice (n = 3–4 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; ****P < .0001). (E) TAC1 mRNA levels (normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]) in the distal colon myenteric plexus of healthy (vehicle) and inflamed (DNBS) mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 48 hours or 3 weeks after induction of DNBS colitis (n = 4–7 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; *P = .0368).

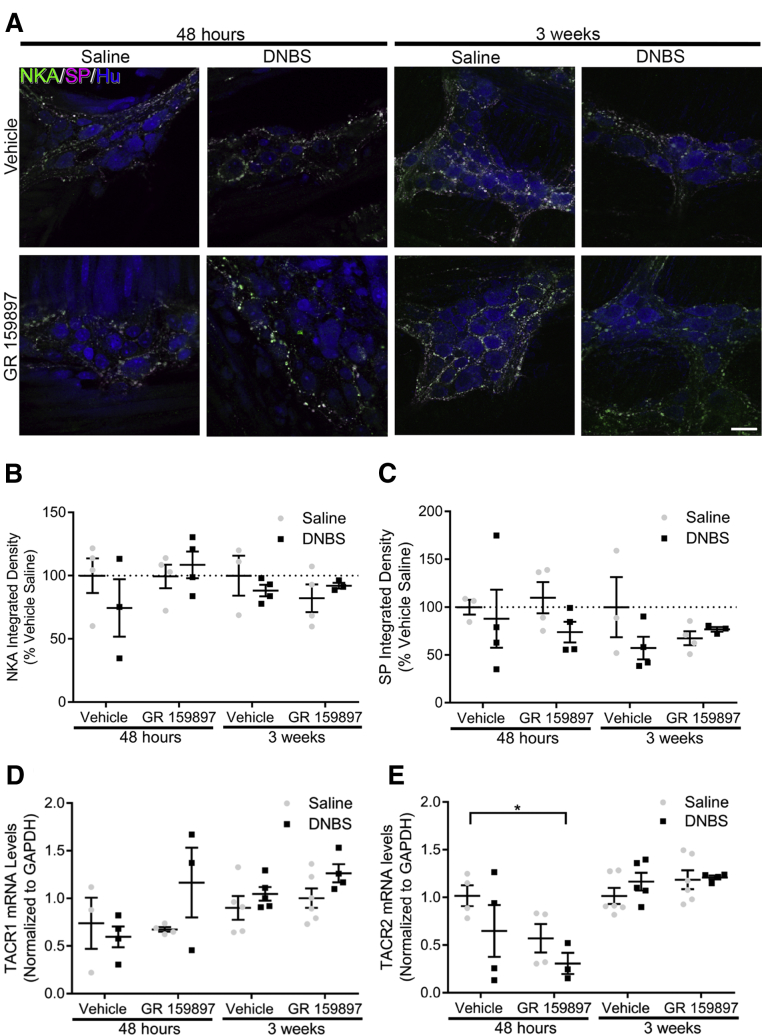

Tachykinin Peptide and Receptor Expression Are Not Altered Significantly During Inflammation

To test if SP or NKA levels are altered during active inflammation or recovery from inflammation, we performed triple-label immunohistochemistry (Figure 7A) and measured NKA and SP immunoreactivity (Figure 7B and C). Although we found increased TAC1 levels during acute inflammation in vehicle-treated mice (Figure 6E), NKA and SP immunoreactivity had no statistical change during active inflammation in vehicle-treated mice (P = .8167 and P = .9997, respectively). To determine if receptor expression is altered by inflammation, we measured changes in tachykinin-receptor mRNA levels (Figure 7D and E) in DNBS mice treated with either vehicle or GR 159897 at 48 hours and 3 weeks after induction of colitis. TACR1 mRNA levels were not altered significantly during inflammation and treatment with GR 159897 did not statistically alter TACR1 mRNA levels (P = .3822) (Figure 7D). In addition, TACR2 mRNA levels had no statistical change during acute inflammation in vehicle-treated mice (P = .5447) and were reduced significantly during inflammation in mice treated with GR 159897 (P = .0432) (Figure 7E). Together, these data suggest that neuroinflammation in the gut is associated with changes in tachykinin peptide expression, but is not associated with significant changes in tachykinin-receptor expression.

Figure 7.

The expression of tachykinins and their receptors is not altered during inflammation. (A) Representative single optical section (1 μm) images of triple-label immunohistochemistry for the pan-neuronal marker Hu (blue), NKA (green), and SP (magenta) in saline and DNBS mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 48 hours or 3 weeks after induction of colitis. Scale bar: 30 μm (applies to all images). Labeling is representative of experiments performed on a minimum of 3 mice. Quantification of (B) NKA and (C) SP integrated density in saline and DNBS mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 48 hours or 3 weeks after induction of colitis (n = 3–4 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons, normalized to group vehicle saline). Quantification of (D) TACR1 and (E) TACR2 mRNA expression from the distal colons of healthy or inflamed mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 48 hours or 3 weeks after induction of colitis (n = 3–6 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]; *P = .0344).

NK2R Antagonism Prevents Neurodegeneration and Reactive Gliosis in the ENS

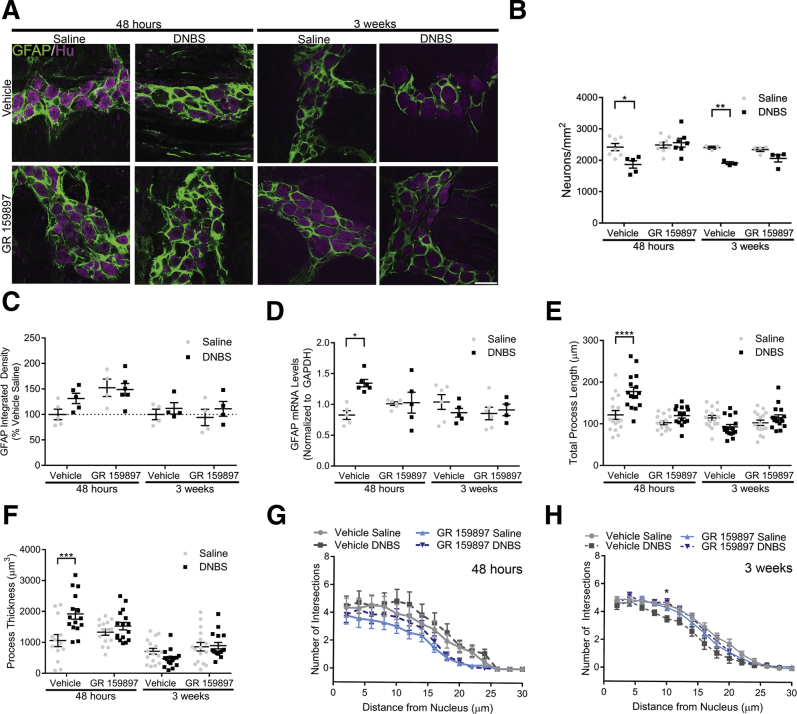

Our data show that intercellular communication driven by NKA activates glial mechanisms that are involved in neuroinflammation in the ENS.31 Therefore, we hypothesized that blocking NK2Rs during inflammation would protect against neuroinflammation. In agreement, we found that mice treated with GR 159897 were protected against neurodegeneration during and after recovery from colitis (Figure 8A and B). Likewise, inflamed mice treated with GR 159897 did not develop reactive gliosis (Figure 8A and D–H). This is important because enteric glia are responsible for driving neuron death during colitis.31 Reactive gliosis is a complex response that involves changes in GFAP expression51, 52 and glial morphology.30, 53 In agreement, we observed a significant 63% (P = .0114) increase in GFAP mRNA levels in mice during active inflammation and a significant 46% (P < .0001) and 81% (P = .0003) increase in glial process length and process thickness, respectively (Figure 8D–F). Importantly, all of these indicators of reactive gliosis were prevented by treatment with GR 159897 during active inflammation. Similarly, after recovery from inflammation, GFAP mRNA levels and glial process length and thickness were not significantly different from healthy controls (Figure 8D–F). Surprisingly, we did not observe significant changes in total GFAP immunoreactivity levels in healthy or inflamed animals or those treated with GR 159897 at either time point (Figure 8C). This may indicate that glial GFAP expression is affected mainly at the transcriptional level during the active phase of inflammation. Glial process branching had no statistical change in inflamed mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 (Figure 8G). After recovery from inflammation, glial process branching decreased by 6% at 10 μm from the nucleus in vehicle-treated mice (P = .0185) (Figure 8H). Collectively, these results show that the antagonism of NK2Rs with GR 159897 prevents key changes associated with neuroinflammation in the ENS such as neurodegeneration and reactive gliosis. In addition, we show that enteric glia become reactive during active inflammation and these changes are reversed after recovery from colitis.

Figure 8.

The NK2R antagonist GR 159897 limits neuropathy and reactive gliosis in the myenteric plexus during inflammation. (A) Representative confocal microscopy images of dual-label immunohistochemistry for GFAP (green) and the pan-neuronal marker Hu (magenta) in healthy (saline) and inflamed (DNBS) mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 48 hours or 3 weeks after induction of colitis. Scale bar: 30 μm (applies to all images). Labeling is representative of experiments performed on a minimum of 4 mice. (B) Quantification of myenteric neuron packing density in healthy and inflamed mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 48 hours or 3 weeks after induction of colitis (n = 3–8 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; *P = .02239; **P = .0097). (C and D) Quantification of (C) GFAP protein expression (integrated density, n = 4–6 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons, normalized to group vehicle saline) and (D) GFAP mRNA levels (n = 4–7 mice; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons, normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]; *P = .0114) in samples of myenteric plexus from the distal colons of healthy and inflamed mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 48 hours or 3 weeks after induction of colitis. (E and H) Quantification of glial morphology including (E) total process length, (F) process thickness, and Scholl analysis for process branching at (G) 48 hours or (H) 3 weeks after induction of colitis (n = 16 glia; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; *P = .0185; ***P = .0003; ****P < .0001).

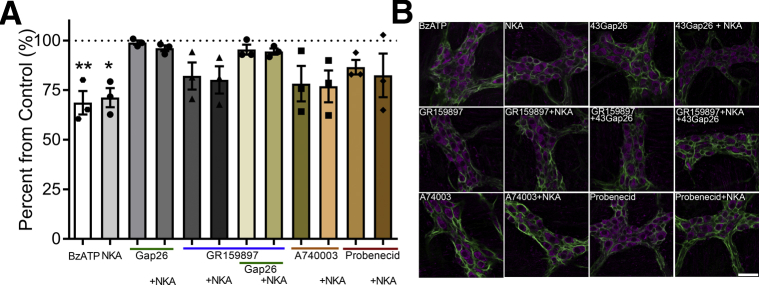

NKA Drives Enteric Neurodegeneration Through Mechanisms That Require Glial Cx43 Hemichannels

The protective effects of GR 159897 on reactive gliosis and neurodegeneration during colitis strongly suggest that NK2Rs contribute to neuroinflammation in the ENS through glial mechanisms. Especially when taken into consideration with our mechanistic studies showing that intercellular communication driven by NKA involves glial mechanisms that drive neuron death. To test this notion, we used an in situ model of neuroinflammation in whole-mount preparations of myenteric plexus to study the underlying intracellular mechanisms (Figure 9). Similar to our published data with purine-driven neurodegeneration in this model, we found that 1 μmol/L NKA was sufficient to drive myenteric neuron death to an equal extent as the P2X7R agonist BzATP (300 μmol/L) (29% reduction with NKA vs 31% reduction with BzATP) (Figure 9). P2X7R-driven enteric neuron death requires the activation of enteric glia and subsequent mechanisms that involve purine release through glial Cx43 hemichannels.31 Similarly, blocking glial Cx43 hemichannel activity with the mimetic peptide 43Gap26 (100 μmol/L) completely protected against NKA-driven neuron death (Figure 9). Antagonizing NK2Rs with GR 159897 (10 μmol/L) did not protect against neuron death driven by NKA (P = .2524), and the combination of GR 159897 and 43Gap26 completely protected against neuron loss. Enteric neurodegeneration during inflammation requires the activation of neuronal P2X7 receptors and neuronal adenosine triphosphate release through Panx1 channels.26, 31 Blocking these mechanisms with the P2X7-receptor antagonist A74003 (10 μmol/L) or the Panx1 inhibitor probenecid (2 mmol/L) protected against neuron death driven by NKA (by 77% and 82%, respectively). Together, these data show that NKA drives neurodegeneration through similar mechanisms as purine-driven neurodegeneration. These mechanisms include the activation of neuronal P2X7 receptors, neuronal Panx1 channels, and glial Cx43 hemichannels.

Figure 9.

NKA-driven enteric neurodegeneration requires the activation of NK2Rs and Cx43 hemichannels. (A) Quantification and (B) representative images of the mean packing density of HuC/D-immunoreactive neurons in myenteric ganglia after in situ activation of P2X7Rs with BzATP or activation of NK2Rs with NKA in the presence or absence of the Cx43 inhibitor 43Gap26, the NK2R antagonist GR 159897, the P2X7 antagonist A74003, or the pannexin-1 inhibitor probenecid (n = 3 mice; 1-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; *P = .0157; **P = .0073). Enteric neurons are labeled with HuC/D (magenta) and enteric glia are labeled with GFAP (green) in all panels. Scale bar: 20 μm (applies to all images).

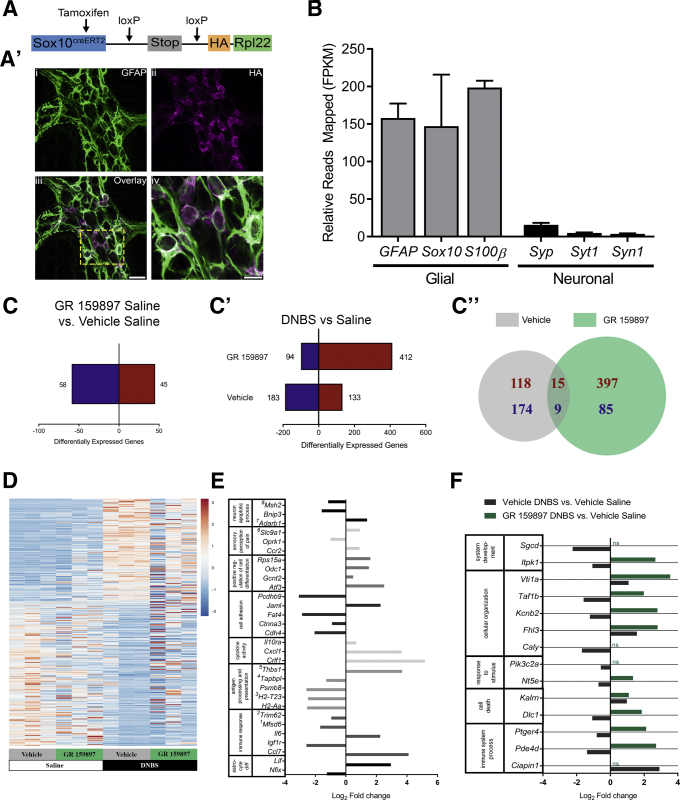

Glial Transcriptome Alterations Driven by Acute Inflammation

To understand the glial response to inflammation in more depth, we specifically isolated and sequenced glial ribosomal-associated mRNA (translating mRNA) from the myenteric plexus of healthy and inflamed animals (Figure 10). We accomplished this by crossing our glial Sox10::CreERT2+/- driver line with Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice (Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice) to generate mice with hemagglutinin-tagged ribosomes in Sox10-positive enteric glia (Figure 10A). Dual-label immunohistochemistry with antibodies against GFAP and HA on LMMP preparations from the distal colon of Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice confirmed HA-tagged ribosomes were localized predominantly to enteric glia (Figure 10A’). Although SOX10 protein is essential for the development of both enteric neurons and enteric glia,54 we found that Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J adult mice had low levels of relative mapped neuronal genes including Syp, Syt1, and Syn1 compared with relative mapped glial genes including GFAP, SOX10, and S100β (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10B). Together with our immunohistochemistry data, this confirms HA-tagged ribosomes are predominantly from enteric glia.

Figure 10.

Glial transcriptome alteration driven by acute inflammation. (A) Schematic of transgene containing the HA-tagged ribosomal protein L22 (Rpl22) driven by the tamoxifen inducible glial promoter (SOX10creERT2). (A’) Confocal image of dual-label immunohistochemistry (single optical plane, 1 μm) for the HA-tagged Rpl22 (magenta) and enteric glia (GFAP, green) in the myenteric plexus of the Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mouse distal colon. (A'iii) The area marked is enlarged in panel A'iv. (A'iii) Scale bar: 20 μm (applies to A'i–iii). (A'iv) Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) Mean fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values of sentinel glial and neuronal genes from vehicle saline samples showing increased relative expression of glial to neuronal transcripts (n = 3 mice; data shown represent biological replicates). (C) Total numbers of differentially expressed enteric glial genes in saline mice treated with the NK2R antagonist GR 159897 or vehicle (GR 159897 saline compared with vehicle saline; n = 3 mice; P < .005; data shown represent biological replicates). (C’) Total numbers and (C”) Venn diagram comparison of differentially expressed enteric glial genes 48 hours after induction of DNBS colitis in mice treated with the NK2R antagonist GR 159897 or vehicle compared with vehicle saline mice. (C–C”) Up-regulated genes are shown in red and down-regulated genes are shown in blue. (D) Heatmaps for all 316 differentially expressed genes in the vehicle DNBS vs vehicle saline comparison in order of fold-change (positive to negative) for all groups (n = 3 mice; P < .005; data shown represent biological replicates). Color scale is based on gene-based Z-scores of log2 FPKM values. (E) Selected differentially expressed genes classified by inflammation-related gene ontology (GO) terms from the distal colon of vehicle DNBS mice compared with vehicle saline mice (n = 3 mice; P < .005; data shown represent biological replicates). Superscripts denote actual categorization in similar, more specific GO terms, which were grouped together under a broader category of GO terms, as follows: 1adaptive immune response; 2innate immune response in mucosa; 3antigen processing and presentation of peptide antigen via major histocompatibility complex class I; 4negative regulation of antigen processing and presentation of peptide antigen via major histocompatibility complex class I; and 5negative regulation of peptide or polysaccharide antigen via major histocompatibility complex class II. (F) Selected differentially expressed genes classified by biological process GO categories, which are significantly differentially regulated between GR 159897 DNBS and vehicle DNBS mice (n = 3 mice; P < .005; data shown represent biological replicates). Relative changes shown are compared with vehicle saline.

We then used next-generation RNA sequencing to study changes in glial mRNA expression during inflammation, and how the glial transcriptome is altered by NK2R antagonism during health and disease (full data set available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE114780, study ID:GES114780). We used a significance level of P < .005 in this initial exploratory study to detect major glial changes. Our first goal was to determine if antagonizing NK2R signaling is sufficient to drive differential expression of enteric glial genes in healthy mice. We found that antagonizing NK2R signaling alone drove an up-regulation of 45 genes and a down-regulation of 58 genes in mice treated with GR 159897 compared with vehicle-treated mice (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10C and D). Next, we aimed to determine if inflammation drives differential expression of enteric glial genes. Our data show that DNBS-colitis drives an up-regulation of 133 genes and a down-regulation of 183 genes (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10C’ and D). To further elucidate glial inflammatory changes, we explored differential expression within gene ontology (GO) terms associated with inflammation (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10E). We found that DNBS colitis drives differential expression in several areas associated with inflammation, some of which (astrocyte differentiation, sensory perception of pain, neuron apoptotic process) could highlight specific changes previously noted in the DNBS inflammatory model. Next, we tested the effects of antagonizing NK2R signaling on enteric glial gene expression in inflammation. Compared with vehicle saline controls, DNBS mice treated with GR 159897 had 412 up-regulated and 94 down-regulated genes (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10C’ and D). Surprisingly, antagonizing NK2R signaling in inflammation differentially regulated a relatively larger number of genes, with only a small portion of these genes synonymously changed without NK2R antagonism in inflammation (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10C”, shared portion of Venn diagram). These differences can be accounted for to a small extent by differential regulation of the same gene, as there are a total of 37 differentially regulated genes between the 2 comparisons, regardless of direction of fold-change (data not shown). A larger portion of these differences can be accounted for by the baseline changes that NK2R antagonism has on glial gene expression (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10C). The remaining changes observed, particularly with the larger number of up-regulated genes with NK2R antagonism during inflammation (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10C’ and C”), may point to areas where NK2R signaling inhibits transcription or translation during inflammation. Finally, we focused our analysis more closely on glial genes that are expressed differentially both with inflammation and with NK2R antagonism in inflammation. To better appreciate what broad-scale changes might be occurring, we used biological process GO categories to detect general processes that may be affected and highlighted those that are involved in the regulation of inflammation (n = 3 mice) (Figure 10F). The GR 159897 DNBS fold-changes in these genes, consistent with the overall predominance of up-regulation in this group, are up-regulated compared with their vehicle DNBS counterparts. Overall, our data suggest that inflammation drives changes in the expression of enteric glial genes that have implications in inflammation-related functions. Importantly, antagonizing NK2R signaling has different overall impacts on glial cells, both in health and during inflammation.

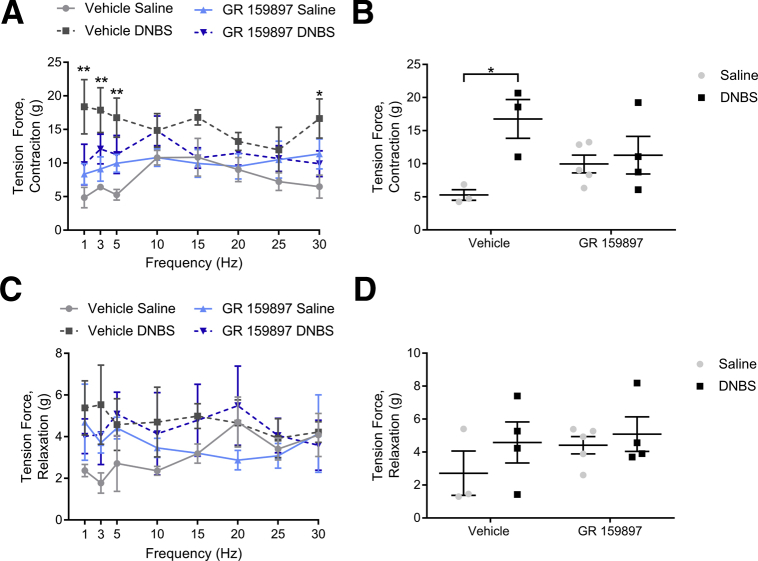

NK2R Antagonism Protects Against Changes in Muscle Contractility During Colitis

Acute inflammation drives persistent dysmotility in large part by changing the function7, 55 and survival26, 31 of enteric neurons. Given the beneficial actions of NK2R antagonism on motility in functional GI disorders9, 22 and our current data showing neuroprotective effects during inflammation, we hypothesized that antagonizing NK2Rs with GR 159897 would protect against increased neurogenic contractions during colitis.26 To test our hypothesis, we performed contractility studies from mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 7 days after induction of colitis. We found that inflammation significantly enhanced neurogenic contractions by 217% (P = .0261) and treatment with GR 159897 prevented this increase (Figure 11A and B). Inflammation had no statistically significant effect on neurogenic relaxations, and treatment with GR 159897 did not significantly alter neurogenic relaxations (Figure 11C and D). These results confirm the hypothesis that NK2R antagonism protects against functional changes associated with inflammation in the gut.

Figure 11.

NK2R antagonism prevents changes in neuromuscular transmission after colitis. (A–D) Neurogenic (A and B) contractions and (C and D) relaxations driven by EFS (20 V, 0.3 ms, 5 Hz) in colons from mice treated with vehicle or GR 159897 at 7 days after induction of colitis. (A and B) DNBS enhanced neurogenic contractions, (C and D) but did not significantly alter neurogenic relaxations. (A and B) Treatment with GR 159897 diminished the effects of DNBS colitis on neurogenic contractions (n = 3–4; 2-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons; *P < .05; **P < .01).

Discussion

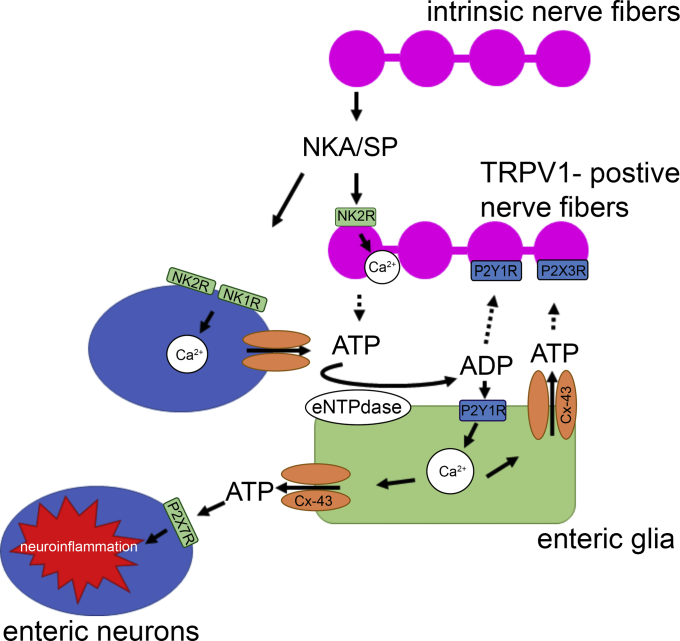

Tachykinins are a family of endogenous peptides that include SP and NKA. They are widely expressed in the GI tract and are involved in both physiological and pathologic processes.11, 12, 13, 14 Physiologically, they are involved in the modulation of motor activity,56, 57, 58 secretion,11, 12, 59 and immune responses.9, 58 In pathologic conditions, tachykinins are implicated in modulating inflammation60, 61, 62 and inflammation-induced changes in motility and secretion.20, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 The ENS and primary afferent neurons are the major sources of tachykinins in the gut and noxious stimulus can drive tachykinin release and neurogenic inflammation in the ENS.12, 13 However, how tachykinin signaling interacts with extrinsic and intrinsic sensory neurons, enteric neurons, and glia is not fully understood. Here, we tested the hypothesis that tachykinins are involved in signaling between extrinsic and intrinsic sensory neurons and glia. Our results show that the tachykinin NKA contributes to neuroinflammation in the ENS through a multicellular signaling cascade involving enteric neurons, TRPV1-positive sensory nerves, and enteric glia (Figure 12). Our data confirm earlier reports showing that intrinsic neuronal varicosities are the main source of tachykinins in the ENS, and expand upon these findings to show that NK2R are localized to sensory neurons and that their stimulation drives activity in enteric neurons and glia. Importantly, antagonizing NK2R signaling with GR 159897 prevents key aspects of neuroinflammation in the ENS such as reactive gliosis and neurodegeneration. Interestingly, the beneficial effects of antagonizing NK2R signaling are mediated primarily by their suppressive action on neuro–glia communication because NKA-driven neurodegeneration was Cx43-hemichannel dependent. Together, our data show that tachykinins are novel mediators of enteric neuron–glia communication, which could play an important role in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal dysfunction.

Figure 12.

Schematic model of the intercellular signaling mechanisms that underlie the effects of NKA on neuroinflammation in the ENS. NKA and SP released from intrinsic neuronal varicosities drive NK1R activation on enteric neurons and NK2R activation on nociceptive neurons and enteric neurons. Activation of NKRs drives adenosine triphosphate (ATP) release from enteric neurons that recruit activity in surrounding enteric glia by activating P2Y1Rs. Intracellular signaling pathways downstream of P2Y1R activation drive glial Ca2+ responses that contribute to Cx43 hemichannel opening and ATP release that further enhances glial responses, drives P2X7R-mediated neuroinflammation, and P2Y1R activation on nociceptive neurons. ADP, adenosine diphosphate. eNTPdase, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 2.

Our findings suggest that tachykinins are key mediators between sensory neurons, enteric neurons, and glia. We found that enteric neurons predominantly express NK1R, whereas NK2Rs are expressed on enteric neuronal cell bodies and varicosities and by TRPV1-positive neuronal varicosities. This is consistent with previous data showing that in the mouse distal colon NK1Rs are expressed predominantly by myenteric intrinsic primary afferent neurons, descending interneurons, and inhibitory motor neurons.12 In addition, we did not observe significant NK1R expression by enteric glia, which is consistent with previous data showing that enteric glia do not respond directly to the NK1R agonist SP.64 Importantly, we did not observe significant NK2R expression by glia in our immunohistochemical and transcriptome data. This is in agreement with a prior microarray transcriptome study.65 To this point, the localization of NK2Rs in the mouse distal colon has remained unclear. In the guinea pig ileum, NK2Rs are expressed primarily by smooth muscle cells, nerve varicosities, and epithelial cells,12, 14 but species differences preclude extrapolations to mice. Importantly, electrophysiological studies show that the activation of NK2R leads to phosphorylation of TRPV1 on nociceptive neurons.66 Our data show that the activation of NK2Rs with NKA induces Ca2+ responses in TRPV1-positive neuronal varicosities and in enteric neurons and glia. Interestingly, enteric glia can respond before or after enteric neuronal response, suggesting that TRPV1-positive neuronal varicosities interact directly with enteric glia. This is consistent with our immunohistochemical data showing that NK2R-immunoreactive neuronal varicosities are in close proximity to enteric glia.

The pattern of glial activity evoked by NKA is entirely different from what we31, 42 and others52, 53, 64 have observed with purinergic agonists. Purinergic agonists typically evoke a relatively uniform Ca2+ transient among enteric glia that peaks and concludes in a matter of seconds. In contrast, NKA evokes stochastic glial Ca2+ transients and drives activity that persists for several minutes. We studied the mechanisms underlying these unique glial responses and found that they require the activation of neuronal NK2Rs, glial P2Y1Rs, and Cx43. The participation of glial Cx43 is not entirely surprising given the key role of this protein in glial intercellular communication and specifically in the propagation of responses among enteric glia.31, 42 However, we were surprised that glial responses to NKA were not totally abolished in the presence of GR 159897 and were increased in the presence of the NK1R antagonist CP 96345. One explanation for this observation is that although NKA preferentially interacts with NK2Rs, it can potentially interact with both NK1 and NK2Rs that might affect agonist availability or feedback signaling from enteric neurons. In support, the inhibition of P2Y1Rs with MRS 2500 significantly attenuated the duration and number of glial responses to NKA. Together, these results indicate that glial responses to nociceptive neuronal NK2R activation are mediated through mechanisms that involve neuron-to-glia and glia-to-glia communication.

Tachykinins are an attractive class of candidate mediators of acute inflammatory responses in the ENS because they are released from hyperactive IPANs55 and their expression is altered during intestinal inflammation in animal models and humans.12, 14, 21, 61, 67 In support, our results show an up-regulation of TAC1 mRNA during acute colitis and a trending decrease in both NKA and SP immunoreactivity. Prior studies have indicated that NK2Rs contribute to gut inflammation in animal models because NK2R antagonism with SR 48698 prevented weight loss and reduced macroscopic damage during TNBS colitis in rats and guinea pigs.60 In this study, we did not observe a significant effect of GR 159897 on the initial inflammatory insult, but GR 159897 did enhance the recovery from inflammation as reflected by animal weight. However, we did not observe significant improvement in the colonic macroscopic damage score or in histologic scoring. The additional beneficial effects observed by treatment with SR 48698 could be driven by several factors including species differences in receptor expression or structural difference between the antagonists. Importantly, SR 48698 also acts on μ-opioid receptors,68 calcium channels,69 and other neurokinin receptors.70 Thus, the participation of these other systems on the anti-inflammatory benefits observed cannot be excluded. To our knowledge, GR 159897 has not been shown to interact with other systems.

Interestingly, treatment with GR 159897 also was sufficient to prevent the up-regulation of TAC1 mRNA during colitis. Surprisingly, we found that neither SP nor NKA immunoreactivity was significantly altered during inflammation and after recovery from inflammation. Although changes in mRNA levels do not necessarily correspond to changes in protein expression,71 these data suggest that changes in tachykinin levels could contribute to neuroinflammation. This is important because it suggests that the regulation of tachykinins depends on positive feedback loops driven by tachykinins acting on NK2Rs, and this could be an important mechanism in disease progression. We found that treatment with the NK2R antagonist GR 159897 significantly decreased NK2R mRNA levels. This suggests that antagonizing NK2Rs stimulates a down-regulation of NK2R expression.

Inflammation alters neuromuscular transmission and disrupts GI motility.72, 73 For example, DNBS colitis creates persistent changes such as enhanced EFS-elicited neurogenic contractions and attenuated EFS-elicited neurogenic relaxations that persist after resolution of colitis.26 In support, we found that DNBS colitis enhanced EFS-elicited neurogenic contractions, but we did not observe significant effects of DNBS colitis on neurogenic relaxations. This may be because the contractility studies were performed during the active phase of inflammation (7 days after DNBS), whereas the previous study performed contractility studies during the resolution of inflammation (21 days after DNBS). Importantly, we found that NK2R antagonism was sufficient to protect against the enhanced neurogenic contractions associated with DNBS. This is consistent with previous data showing that NK2R agonists mediate circular muscle contractions in the human colon and ileum.12, 74 Together, these data show that antagonizing NK2Rs could provide functional benefits in colitis-induced dysmotility.

It is now clear that enteric glia play an important role in immune responses during inflammation.24 Enteric glia both respond to, and secrete inflammatory mediators such as interleukin 1, interleukin 6,75 and purines.31 However, the mechanisms that trigger glial responses to gut inflammation are still unclear. Although our results show that sensory neurons are the primary site of activation for NK2Rs, we found that tachykinins could drive neuro-to-glia signaling and this communication plays a major role in the generation of gliosis during inflammation. GR 159897 had a major attenuating effect on reactive gliosis and prevented key changes in GFAP expression and morphologic modifications that are indicative of reactive glia. Although GR 159897 significantly increased GFAP mRNA levels during inflammation, we did not observe corresponding changes in GFAP immunoreactivity. This difference is not surprising given that changes in mRNA levels do not necessarily directly correspond to changes in protein expression.70 However, we performed additional studies in which we reconstructed individual glial cells to study glial morphology and confirmed that reactive gliosis was occurring. Our findings show that glial process length and thickness are increased significantly during inflammation and this observation is consistent with changes in reactive astrocytic processes that occur during injury or inflammation.30 In agreement with our GFAP expression analysis, we found that GR 159897 prevented the extension of glial processes during inflammation.

In addition, we found that inflammation drove changes in gene expression that have impacts on inflammatory processes, interactions with neurons and immune cells, and the control of gut functions. NK2R antagonism affects the glial expression of a subset of genes in health and has a major impact on glial gene changes during inflammation. Interestingly, very few of the differentially regulated glial genes observed in inflamed mice also were differentially regulated in inflamed mice treated with GR 159897, despite the latter having a relatively large overall number of differentially regulated genes. These data suggest that communication between sensory neurons and enteric glia during acute inflammation plays a major role in determining glial phenotype. Our data include a number of novel glial genes and pathways, and it will be important to study and validate these pathways in further work. Understanding the specific glial mechanisms regulated by cross-talk with sensory neurons may uncover novel pathways that could be targeted to improve the treatment of peripheral neuroinflammation, such as NK2R antagonism-based treatments.

Because this was an exploratory study, we initially used a significance level of P < .005 to study important glial changes. However, this was still a relatively preliminary view of the data and analyzing trends, distributions, and pathway associations will likely produce additional insight in future studies. Furthermore, although relative expression of typical neuronal genes was low in our samples, Sox10 is a neural crest gene and it is possible that a small component of our sample reflects neuronal genes. However, given the scarcity of neuronal HA expression and the low yield of the Ribotag procedure, it is unlikely that neuronal RNA significantly contributed to our data set. It also is important to note that the Ribotag procedure selects for ribosomal-bound mRNA, which implies a translational process more so than a transcriptional one, although still measuring mRNA. This is important because ribosomal-bound mRNA is presumably in the process of being translated into protein and likely reflects active processes. Further research, specifically with larger sample sizes, sex stratification, and a single gene scale, will be important to uncover more detailed changes in NK2R antagonism on glial-specific changes, and the interplay between mRNA and protein expression levels.

We recently showed that glial activation during colitis drives enteric neurodegeneration through mechanisms that involve glial Ca2+ responses and the potentiation of Cx43 hemichannel opening by nitric oxide.31 Similarly, our present data show that the NK2R agonist NKA drives enteric neuron loss in situ that is dependent on glial Cx43 hemichannel activity. This is important because it suggests that the activation of NK2Rs on sensory nerves drives neuron-to-glia communication that can trigger adenosine triphosphate release from glial Cx43 hemichannels, leading to P2X7-mediated enteric neurodegeneration.26 In support, we found that animals treated with GR 159897 were protected against neurodegeneration during colitis. Given that enteric glia are a major source of purines in the ENS,31 purines released from enteric glia could activate P2X3 and P2Y1 receptors on TRPV1-positive nociceptive neurons and contribute to visceral hypersensitivity in many gastrointestinal disorders76, 77 (Figure 12).

In conclusion, our results show that TRPV1-positive sensory neurons predominantly express NK2Rs in the ENS and that the stimulation of these receptors by NKA released from enteric neurons drives signaling in enteric glia and neurons. Antagonizing NK2R signaling from TRPV1-positive neurons prevented reactive gliosis, neurodegeneration, and protected against enhanced neurogenic contractions during colitis. NK2R antagonism prevented enteric neuroinflammation and glial reactivity by interfering with neuron-to-glia and glia-to-neuron signaling. Our findings show that neuron-to-glia communication is induced by tachykinin-receptor activation on TRPV1-positive nerve fibers, implying that interfering with neuron-to-glia activation could be an important therapeutic approach in the treatment of functional GI disorders and combining NK2R antagonists with current treatments may reduce visceral pain in GI disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gina Leinninger for assistance and equipment to perform quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction studies. The authors also thank Isola Brown and Aaron Chow for assistance with confocal imaging and Jonathon McClain for assistance with maintenance of mouse colonies and confocal imaging.

Footnotes

Author contributions Brian D. Gulbransen was responsible for the overall project conception and supervision, and edited the manuscript; Ninotchska M. Delvalle designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; Christine Dharshika characterized Sox10::CreERT2+/-/Rpl22tm1.1Psam/J mice and performed experiments for glial transcriptome analysis; Wilmarie Morales-Soto characterized TRPV1tm1(cre)Bbm/J::Polr2atm1(CAG-GCaMP5g,-tdTomato)Tvrd mice, performed calcium imaging experiments, and transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 immunohistochemistry experiments; David E. Fried performed contractility experiments; and Lukas Gaudette performed immunohistochemistry experiments for receptor expression.

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This project was supported by grant R01DK103723 from the National Institutes of Health (B.D.G.) and by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (Senior Research Award 327058 to B.D.G.).

Supplementary Material