Short abstract

Objective

This study was performed to evaluate the 1-year survival rate and functional outcomes of 20 patients who underwent intersphincteric resection (ISR) for low rectal cancer.

Methods

Twenty patients who underwent ISR for low rectal cancer were followed up for 1 year. Complications, functional outcomes objectified by the Wexner score, and oncological outcomes were assessed.

Results

The short-term survival rate was 100%. The median Wexner score was ≤10 in all patients at 12 months after surgery. Signs of local recurrence were absent, and antigen levels remained within the reference ranges 1 year postoperatively.

Conclusions

ISR is a feasible alternative in highly selected patients who primarily refuse a colostomy bag and present with type II or III tumors. In the present study, patient-reported continence was satisfactory, and the absence of a colostomy bag increased patients’ quality of life. The oncological outcomes were satisfactory at 1 year postoperatively.

Keywords: Intersphincteric resection, low rectal cancer, short-term survival, functional outcome, oncological outcome, Wexner score

Introduction

Intersphincteric resection (ISR) has been performed since 1994, when Schiessel et al. 1 presented the first functional results and theorized the associated oncological results. This intervention can eliminate the need for a permanent colostomy bag, although a temporary protective ileostomy bag may still be required. ISR is feasible for patients with type II (juxta-anal) or type III (intra-anal) low rectal cancer (<6 cm from the anal verge), for which partial ISR or total ISR is performed, respectively. 2 The indications for ISR have been theorized in numerous publications and include, among others, a normal preoperative sphincter tonus and no tumor invasion at the level of the external anal sphincter and levator ani muscle. 3 Digestive tract restoration is achieved by performing hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis, which is protected by an ileostomy in some cases. When performed in compliance with current oncologic principles, simultaneous ISR and total mesorectal excision produces results comparable with those of classic intervention for low rectal cancer. 4 Therefore, ISR appears to be an alternative approach with reduced emotional impact due to the presence of normal defecation and satisfactory oncologic results. However, patients’ postoperative quality of life has not yet been sufficiently assessed from the perspective of fecal continence, with authors reporting varying results. 5 The objective of the present study was to evaluate the functional results of ISR and assess the short-term survival and oncological outcomes.

Materials and methods

Methods

This prospective study involved patients admitted to the First Surgical Clinic of the Tîrgu-MureEmergency County Hospital with a diagnosis of low rectal cancer from 2015 to 2016. The main inclusion criterion was patient refusal to undergo temporary colostomy or ileostomy, which was registered by written informed consent. Other inclusion criteria were tumor location, tumor type (II or III), and the preoperative Wexner score. Patients with juxta-anal tumors (type II) or intra-anal tumors (type III) located <6 cm from the anal verge underwent partial ISR and total ISR, respectively. Both the Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Tîrgu-Mureș, and the Ethics Committee of the Tîrgu-Mureș Emergency County Hospital approved the study. All patients provided written informed consent.

Preoperative preparation and staging

All patients underwent rectal palpation, colonoscopy, and tumor biopsy with a malignant histopathology report. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data were available for 14 of 20 patients and showed confinement of the tumor to the rectal wall (stage T2 tumors). The remaining 6 patients presented with computed tomography (CT) scans that showed similar local tumor spread. Following oncologic committee approval, all patients underwent long-term pelvic neoadjuvant radiotherapy with a total dose of 50 Gy over 5 weeks according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines Version 2. Preoperative chemotherapy was not administered to any patients.

Every patient was staged prior to neoadjuvant therapy and surgery by means of endoscopy, MRI, and CT. Of the 20 patients in this study, 4 had type III inferior rectal tumors (intra-anal) the remaining 16 had type II inferior rectal tumors (juxta-anal). None of the patients had distant metastatic disease at the time of surgery (tumor-node-metastasis stage of ≤T3bN1M0 according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th Edition). Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) levels were determined, and elevated values (CEA > 10 ng/mL and CA 19-9 > 800 U/mL) were recorded in all patients.

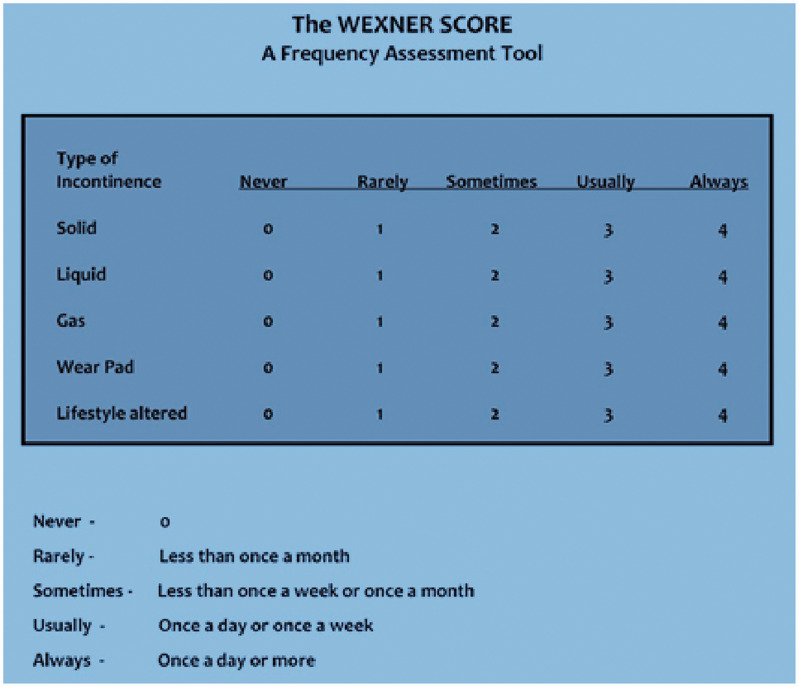

Preoperative sphincter function

We calculated the preoperative Wexner score (Figure 1) for all patients (0 points = perfect continence; 20 points = total incontinence). 6 Manometric evaluation of sphincter function was not performed. We consider the Wexner score system to be the easiest to use, and it has the best correlation between the patient’s subjective perception of continence and the clinical assessment made by the surgeon.7–11

Figure 1.

Wexner scoring system.

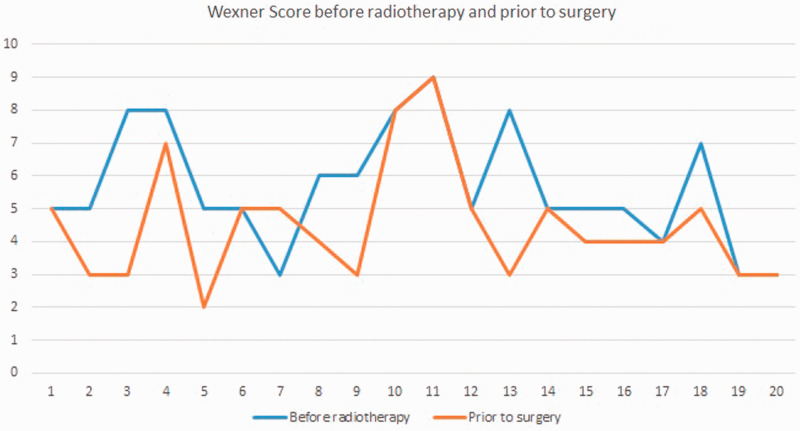

The median pre-radiotherapy Wexner score was 5.65, and the median preoperative (post-neoadjuvant radiotherapy) score was 4.5. Patients with a preoperative Wexner score (post-radiotherapy) of ≥10 were not included in the study, and ISR was not performed in those patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Wexner scores before and after radiotherapy.

Surgery

All surgical procedures were performed by the same surgeon, who performed 16 (80%) partial ISR procedures and 4 (20%) total ISR procedures for type II and III rectal tumors, respectively, following the technique described below. A partial laparoscopic approach was used in three patients, and full laparoscopic surgery was performed in one patient. Restoration of bowel continuity was achieved by performing hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis with absorbable suture in all patients; no protective ileostomy or colostomy was used. We did not construct a colonic J pouch in any patient.

ISR was performed as follows. In all cases, the abdominal portion of the surgery began with the primary vascular approach of the inferior mesenteric artery, followed by left colon mobilization and ligation of the inferior mesenteric vein, and total mesorectal excision. The intersphincteric groove was entered from the abdomen whenever possible to assess tumor invasion. The perineal portion began with digital and instrumental dilatation, followed by exposure of the anal canal using four to six traction threads [in the absence of a Lone Star Retractor (CooperSurgical, Trumbull, CT, USA]. After exposure, a circumferential incision was made on the anal mucosa distal to the dentate line (for total ISR) or at the level the dentate line (for partial ISR). A minimum distance of 1 cm distally was maintained in all cases. The perineal phase continued with intersphincteric circumferential cranial preparation to meet the dissection plane from the abdomen. Following completion of the dissection, the rectum was delivered through the anus with transection of the sigmoid colon at the appropriate level. The final part of the surgery consisted of a hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis.

Results

The study population comprised 20 patients [15 (75%) male, 5 (25%) female; median age, 66 years]. All patients were from an urban background. None of the patients had an oncological history. The median hospital stay was 8 days; that for laparoscopic surgery was 5 days. Bowel movement resumed on day 1 or 2 following surgery. The severity of pain during the hospital stay, as assessed by the quantity of analgesics the patients received, was low.

No perioperative complications or hospital mortality occurred. A minor complication was noted in three (15%) patients approximately 10 days following surgery (mucosal–submucosal necrosis at the level of the pulled-through colonic segment); 12 all three patients were treated in an ambulatory setting without the need for anesthesia. This complication was probably due to mucosal ischemia. No wound infection/dehiscence or intra-abdominal abscesses occurred. No patient developed anastomotic leakage or required a second surgery.

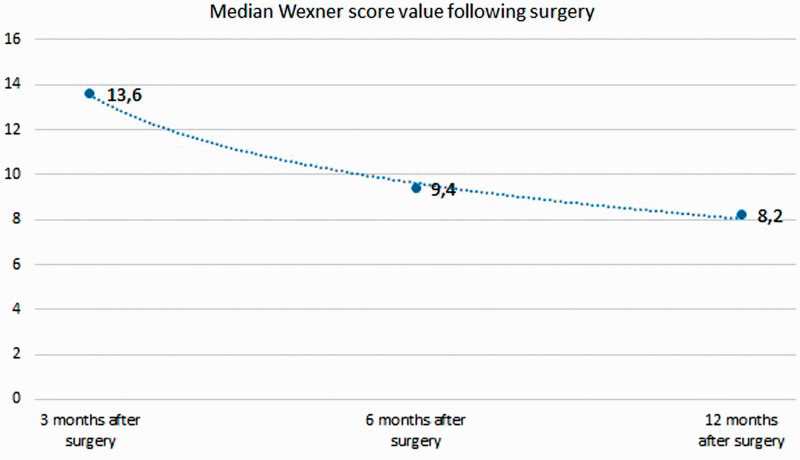

Follow-up examinations were performed at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery and included a clinical assessment, Wexner score calculation, antigen level measurements, MRI, and ultrasound with or without thoracic radiography. Data on the functional results were obtained from each patient via the Wexner score during the medical appointments.

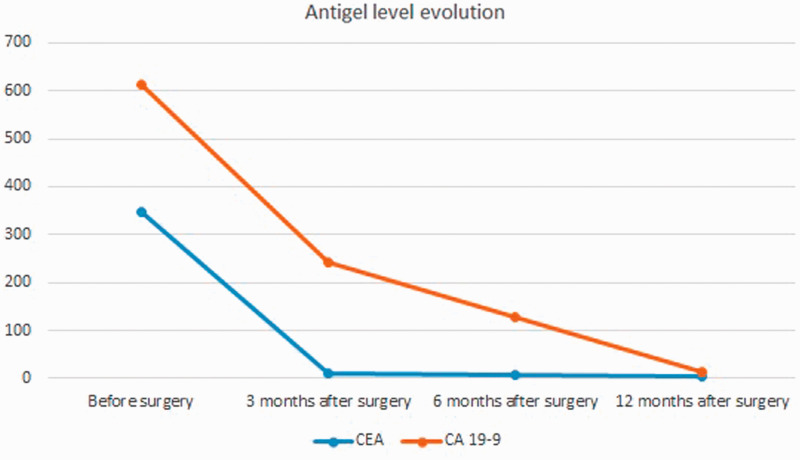

At 3 months postoperatively, no patients showed signs of local tumor recurrence on imaging. The CEA and CA 19-9 levels were elevated in 13 patients (6 patients had an elevated CA 19-9 level) (Figure 3). The median Wexner score at this time was 13.6. Subjectively, the patients reported relatively unsatisfactory continence, especially patients with flatulence.

Figure 3.

Preoperative and postoperative antigen levels.

At 6 months postoperatively, most patients had normal CEA and CA 19-9 levels; only three patients had elevated CEA and CA 19-9 levels (Figure 3). Imaging studies indicated the absence of local relapse and metastatic disease. The median Wexner score at this time was 9.4. Subjectively, the patients reported satisfactory continence with a few episodes per week of gas incontinence in particular (Figure 3).

At 12 months postoperatively, all patients had normal CEA and CA 19-9 levels (Figure 3). The imaging results (1-year MRI) and general abdominal ultrasound indicated the absence of local relapse and metastatic disease. The median Wexner score was 8.2, and all patients declared that they were satisfied with the choice of surgery and the level of continence, under the terms of major surgery (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Median Wexner scores.

Discussion

The main objective of the present study was to evaluate the short-term functional results of ISR in a small group of patients who underwent operations by the same surgeon.

The absence of perioperative and postoperative mortality and the low morbidity rate in the present study are consistent with the findings of other studies from similar-volume medical centers, including studies involving the laparoscopic approach.4,13–16 The rate of complications, predominantly wound infection and postoperative pain, was worse in patients who underwent abdominoperineal resection than in those who underwent ISR; this is also consistent with the findings of other studies. 17

Considering the preoperative and postoperative serum CEA and CA 19-9 levels and the absence of local relapse and metastasis during the first year after surgery, we may conclude that the oncologic result of ISR is not compromised.2,17–20 The fact that all patients in our study were smokers explains the elevated CEA and CA 19-9 levels found in some of them. The normal values found at 12 months after surgery may indicate a good oncological outcome, but further determination of antigen levels is necessary to verify this.

All patients reported the acceptance of imperfect continence while lacking a colostomy bag, a finding also reported by other authors.4,5,13,14,21

The complications we observed have also been reported previously. 22 We consider these complications a small price to pay for the absence of a colostomy bag. Mucosal–submucosal necrosis at the level of the pulled-through colonic segment can be addressed in an ambulatory setting without the need for local anesthesia. Depending on the size of the necrotic debris, the necrotic mucosa can simply be removed using forceps. Removal of this mucosa is not followed by bleeding or fistula formation, and patients experience no disturbance in continence. The healing process at the level of the “new anal verge” may also play a role in continence because of fibroblastic proliferation.

Many studies have assessed the effects of neoadjuvant therapy (chemotherapy or radiotherapy) in the context of fecal continence.23–26 We recorded improved Wexner scores in some patients after radiotherapy; this is probably due to the downsizing effect of neoadjuvant therapy. Because of the low number of patients in this study, however, we cannot elaborate further on this aspect, although all patients underwent preoperative radiotherapy.

Considering the absence of preoperative chemotherapy in our study and the absence of a consensus regarding the ideal protocol for preoperative and postoperative oncologic treatment, no pertinent opinion regarding these treatments can be expressed based on the present study findings.22,27–29

Limitations of the study

One limitation of this study is the low number of patients. Our center is not a colorectal surgery center; thus, the number of eligible patients is low. Our study focused predominantly on using the Wexner scoring system to evaluate sphincter function. Although other scoring systems (Rothenberger scoring system, Vaizey scoring system, and Fecal Incontinence Severity Index) could provide a better assessment of the functional outcome, we believe that the Wexner scoring system is the easiest to use. The short-term follow-up is another limitation of the study, and the results are therefore preliminary. Follow-up of these patients is ongoing.

Conclusions

ISR appears to be a feasible option for highly selected patients with low rectal cancer who refuse a colostomy bag, including a temporary one. Oncologic results are not compromised when performing this procedure compared with classic procedures. From the patients’ point of view, the functional outcomes following ISR were satisfactory in this study. Complications found in our small study group were mild and infrequent compared with complications reported in patients undergoing abdominoperineal resection.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Schiessel R, Karner‐Hanusch J, Herbst F, et al. Intersphincteric resection for low rectal tumours. Br J Surg 1994; 81: 1376–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rullier E, Denost Q, Vendrely V, et al. Low rectal cancer: classification and standardization of surgery . Dis Colon Rectum 2013; 56: 560–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scala D Niglio A Pace U Ruffolo F Rega D andDelrio P.. Laparoscopic intersphincteric resection: indications and results. Updates Surg 2016; 68: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin ST Heneghan HM, andWinter DC.. Systematic review of outcomes after intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klose J, Tarantino I, Kulu Y, et al. Sphincter-preserving surgery for low rectal cancer: do we overshoot the mark? J Gastrointest Surg 2017; 21: 885–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solh W andWexner SD.. Scoring systems. In: Davila GW Ghoniem GM andWexner SD (eds) Pelvic floor dysfunction. London: Springer, 2006. DOI 10.1007/1-84628-010-9_60 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seong M-K, Jung S-I, Kim T, et al. Comparative analysis of summary scoring systems in measuring fecal incontinence. J Korean Surg Soc 2011; 81: 326–331. 10.4174/jkss.2011.81.5.326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bols EM, Hendriks EJ, Berghmans BC, et al. A critical evaluation of the Vaizey score, Wexner score and the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale for clinical use in patients with faecal incontinence. Pelvic Physiotherapy In Faecal Incontinence 2011; 169: 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodrigues BDS, Reis IGN, de Oliveira Coelho FM, et al. Fecal incontinence and quality of life assessment through questionnaires. J Coloproctol (Rio. J.) 2017; 37: 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.De la Portilla F, Calero-Lillo A, Jiménez-Rodríguez RM, et al. Validation of a new scoring system: Rapid assessment faecal incontinence score. World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7: 203–207. 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i9.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nevler A. The epidemiology of anal incontinence and symptom severity scoring. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2014; 2: 79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molnar C andButiurca VO.. Muco-submucosal necrosis-early novel complication following intersphincteric resections. Austin J Pathol Lab Med 2017; 4: 1017. ISSN:2471-0156 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takawa M, Akasu T, Kumamoto K, et al. 2072 Short-and long-term results of intersphincteric resection for very low rectal cancer without neoadjuvant therapy. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51: S352. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pai VD, De Souza A, Patil P, et al. Intersphincteric resection and hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis for low rectal cancer: Short-term outcomes in the Indian setting. Indian J Gastroenterol 2015; 34: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi P, Huang SH, Lin HM, et al. Laparoscopic transabdominal approach partial intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: surgical feasibility and intermediate-term outcome. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 944–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bittorf B, Stadelmaier U, Göhl J, et al. Functional outcome after intersphincteric resection of the rectum with coloanal anastomosis in low rectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2004; 30: 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dindo D Demartines N, andClavien PA.. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamlou R, Parc Y, Simon T, et al. Long-term results of intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2007; 246: 916–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Köhler A, Athanasiadis S, Ommer A, et al. Long-term results of low anterior resection with intersphincteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the lower one-third of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada K, Ogata S, Saiki Y, et al. Long-term results of intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 1065–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bretagnol F, Rullier E, Laurent C, et al. Comparison of functional results and quality of life between intersphincteric resection and conventional coloanal anastomosis for low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 832–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westerduin E, Musters GD, van Geloven AA, et al. Low Hartmann’s procedure or intersphincteric proctectomy for distal rectal cancer: a retrospective comparative cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017; 32: 1583–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cammà C, Giunta M, Fiorica F, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy for resectable rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2000; 284: 1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Group CCC. Adjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer: a systematic overview of 8507 patients from 22 randomised trials. Lancet 2001; 358: 1291–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1731–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 1926–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulu Y Ulrich A andBüchler MW.. Resectable rectal cancer: which patient does not need preoperative radiotherapy? Dig Dis 2012; 30(Suppl. 2): 118–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuhashi N, Takahashi T, Tanahashi T, et al. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic intersphincteric resection for a lower rectal tumor. Oncol Lett 2017; 14: 4142–4150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujimoto Y, Akiyoshi T, Kuroyanagi H, et al. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic intersphincteric resection for very low rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 14: 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]