Abstract

Prion-like RNA binding proteins (RBPs) such as TDP43 and FUS are largely soluble in the nucleus but form solid pathological aggregates when mislocalized to the cytoplasm.What keeps these proteins soluble in the nucleus and promotes aggregation in the cytoplasm is still unknown. We report here that RNA critically regulates the phase behavior of prion-like RBPs. Low RNA/protein ratios promote phase separation into liquid droplets, whereas high ratios prevent droplet formation in vitro. Reduction of nuclear RNA levels or genetic ablation of RNA binding causes excessive phase separation and the formation of cytotoxic solid-like assemblies in cells. We propose that the nucleus is a buffered system in which high RNA concentrations keep RBPs soluble. Changes in RNA levels or RNA binding abilities of RBPs cause aberrant phase transitions.

The intracellular environment is organized into membraneless compartments that have been termed biomolecular condensates because they form by liquid-liquid phase separation (1, 2). These condensates often contain RNA binding proteins (RBPs) with distinctive domains, so-called prion-like domains which are structurally disordered and contain F1 polar amino acids (3) (Fig. 1A). Interactions between prion-like domains and additional interactions between RNAs and RNA binding domains drive the assembly of prion-like RBPs by phase separation (4, 5). However, several prion-like RBPs, such as FUS, TDP43, and hnRNPA1, can also undergo an aberrant transition from a liquidlike state into solid aggregates that has been linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (4–6). One important aspect of these diseases is that aggregate formation is strongly associated with the subcellular location of the proteins. Aggregates in patient neurons are usually found in the cytoplasm, whereas the nucleus is usually devoid of the aggregating proteins (7–10), although there are some noteworthy exceptions (11). Disease causing mutations frequently affect the nuclear partitioning of prion-like RBPs (12, 13), highlighting the importance of cytoplasmic localization. Protein mislocalization to the cytoplasm causes loss-of-function and gain-of-function phenotypes that are thought to underlie disease (14–17). Importantly, genetic relocalization of FUS to the nucleus in yeast strongly decreases FUS toxicity (18). This suggests that the localization of FUS to the nuclear environment suppresses its pathological behavior, which raises two important questions: What prevents prion-like RBPs from forming solid-like aggregates in the nucleus? And why do these RBPs form aggregates in the cytoplasm?

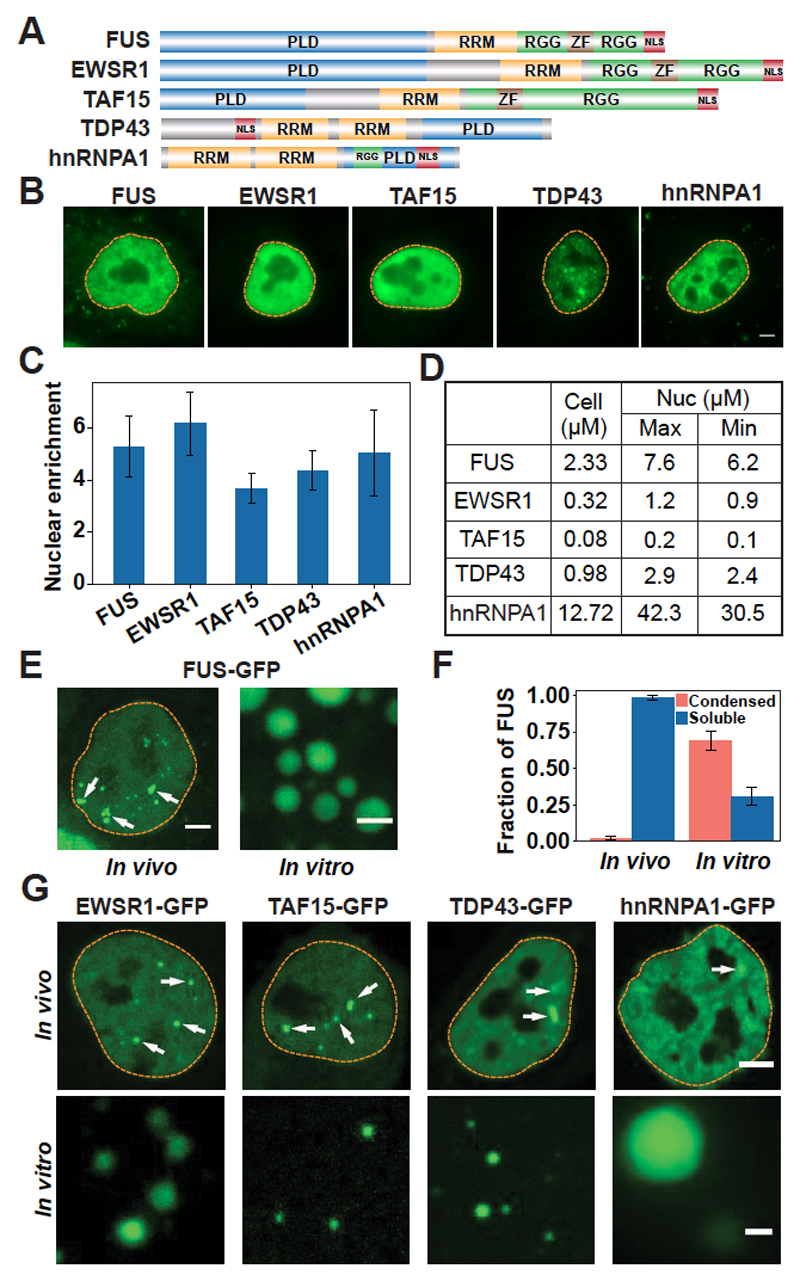

Fig. 1. Prion-like RBPs phase-separate at their physiological concentrations.

(A) Domain structure. PLD, prion-like domain; RRM, RNA recognition motif; RGG, arginine- and glycine-rich region; ZF, zinc finger; NLS, nuclear localization sequence. (B) Representative images of immunostained HeLa cells. Dashed lines indicate the nuclear boundary. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) Quantification of the nuclear enrichment of RBPs. Error bars represent SD. (D) Calculated cellular and nuclear (Nuc) concentrations of RBPs in HeLa cells. (E) Left, live HeLa cell nucleus expressing GFP-tagged FUS from a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC). Arrows point to paraspeckles. Right, FUS-GFP phase-separated in vitro at 7.5 μM. Scale bars, 2 μm. (F) Quantification of the fractions of FUS present in condensed and soluble states in vivo and in vitro. Error bars represent SD. (G) Top, HeLa cell nuclei expressing GFP-tagged RBPs from BACs. White arrows indicate condensates. Bottom, purified RBPs phase-separate at their respective nuclear concentrations. Scale bars, 2 μm.

To answer these questions, we investigated the phase behavior of several prion-like RBPs (Fig. 1A). First, we determined the nuclear concentrations of these proteins. The values ranged from 0.2 μM for TAF15 to 42.3 μM for hnRNPA1 (Fig. 1, B to D, and supplementary methods). Next, we purified these proteins as green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusions and added them to a physiological buffer. At a concentration similar to the nuclear concentration (7.6 μM), FUS phase separated into droplets (Fig. 1, E and F). This behavior contrasted with that in living cells, where only 1% of the nuclear FUS protein was contained in condensates (Fig. 1F), which are paraspeckles (19). The remaining 99% of nuclear FUS protein was diffusely localized. Similar observations were made for TDP43, EWSR1, TAF15, and hnRNPA1 (Fig. 1G, lower panels). These results suggest that although the protein concentration is high enough for phase separation in the nucleus, an additional nuclear factor prevents phase separation.

We hypothesized that nuclear RNA could regulate the phase behavior of prion-like RBPs. To test this idea, we performed an in vitro phase separation assay with FUS in the presence of total RNA (Fig. 2A). In agreement with previous work F2 (20–22), we found that small amounts of RNA promoted liquid droplet formation (Fig. 2B and fig. S1, A to D). RNA-containing droplets contained a higher FUS concentration than RNA free droplets, and they appeared slightly more viscous (fig. S2, A to C). However, upon further increase in the RNA/protein concentration ratio, the droplets became smaller and finally dissolved (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S3). The addition of RNase A resulted in droplet reappearance (Fig. 2D and figs. S4A, panels on the right, and S5), indicating that droplet solubilization depends on intact RNA. Similar results were obtained for EWSR1, TAF15, hnRNPA1, and TDP43 (Fig. 2C). Thus, we conclude that high RNA/protein ratios prevent phase separation and that low ratios promote phase separation.

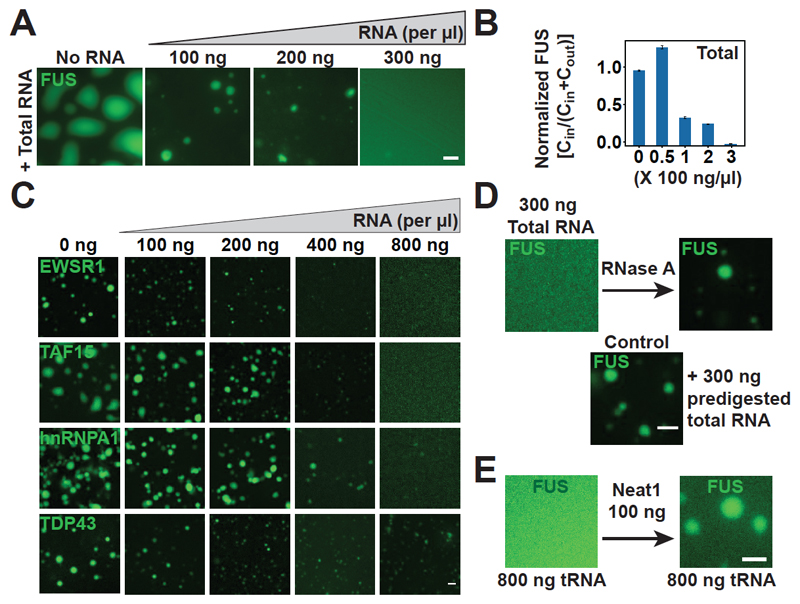

Fig. 2. RNA regulates the phase behavior of prion-like RBPs.

(A) Representative images of purified FUS-GFP (5 μM) in vitro in the presence of total RNA. (B) Quantification of the fraction of condensed FUS-GFP. Cin, fraction of total protein in the droplets; Cout, fraction of total protein in the soluble phase outside the droplets. The value of FUS enrichment in the droplet phase in the absence of RNA was normalized to 1. Error bars represent SD. (C) In vitro phase separation assay with EWSR1, TAF15, hnRNPA1, or TDP43 in the presence of total RNA. (D) Addition of RNase A to a sample of FUS-GFP (5 μM) solubilized with 300 ng/ml of total RNA. (E) Left, FUS-GFP (5 μM) solubilized with 800 ng/ml tRNA in vitro. Right, FUS phase separation triggered by the addition of 100 ng/μl Neat1 RNA in the presence of tRNA (800 ng/μl). Scale bars in (A), (C), (D), and (E), 2 μm.

We next tested whether different types of RNAs differ with respect to their abilities to dissolve FUS droplets. Individually, ribosomal RNA, tRNA, and a noncoding RNA that is known to bind to FUS (Neat1) were all able to solubilize FUS droplets, suggesting a general effect, but smaller RNAs were more potent than larger ones (fig. S4, A to D). Secondary structure was important for enriching FUS in droplets, consistent with results in previous work (20), but secondary structure (fig. S4, A to E) and binding affinity (fig. S6) affected droplet solubilization only slightly. We next asked whether the cellular RNA concentration is high enough to suppress phase separation of FUS. We estimated that the nuclear RNA concentration is ~10.6 times as high as that required for droplet dissolution in vitro (fig. S7 and supplementary methods). However, ~1% of nuclear FUS formed condensates (paraspeckles) (Fig. 1E) by binding to the noncoding RNA Neat1 (19). To test whether Neat1 could nucleate FUS droplets in the presence of a high background concentration of RNA, we added Neat1 RNA to a FUS sample that had been solubilized with tRNA. This led to a reappearance of FUS droplets (Fig. 2E and fig. S4F). We attribute this result to the ability of Neat1 to form large RNA assemblies (fig. S4C), which subsequently recruit FUS. This observation suggests that highly structured RNAs such as Neat1 act as scaffolds that promote the nucleation of condensates in the high–RNA concentration environment of the nucleus. A similar scenario may apply for stress granules in the cytoplasm, which contain large amounts of structured polyadenylated mRNA (fig. S8).

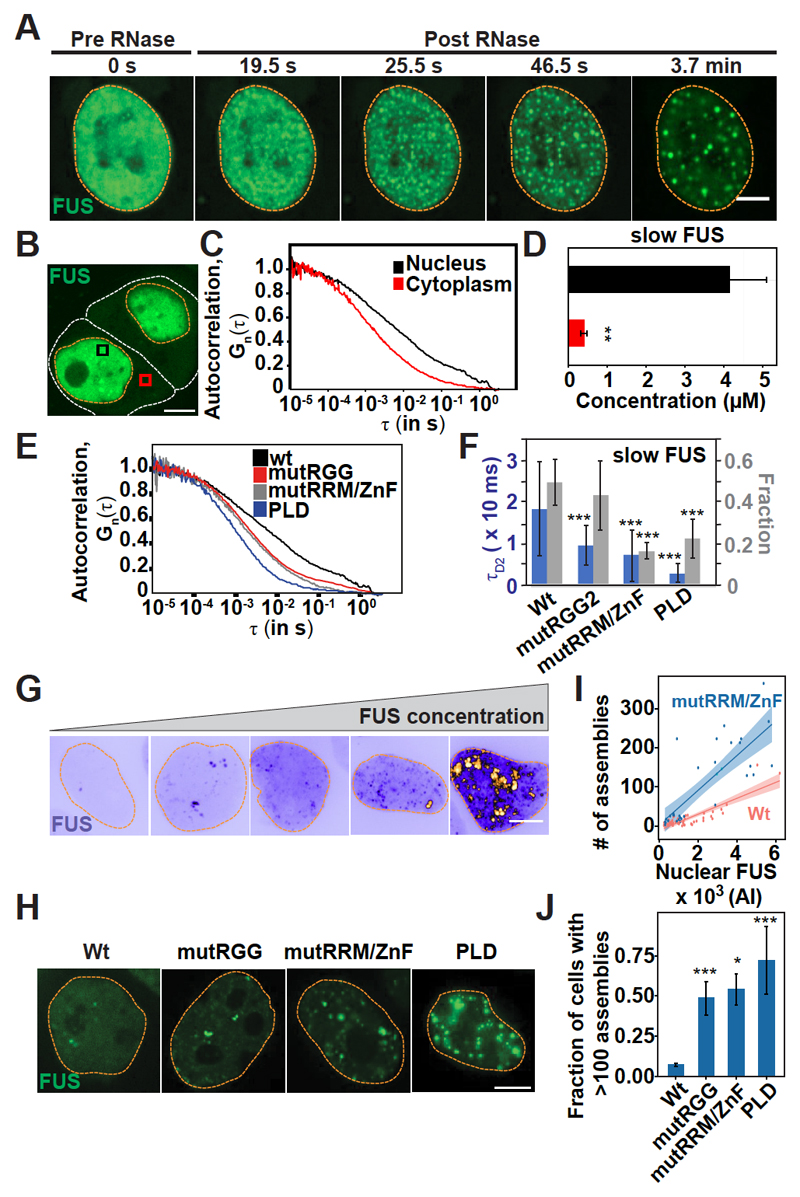

To test experimentally whether the high nuclear RNA concentration keeps FUS soluble, we microinjected ribonuclease A (RNase A) into the nuclei of HeLa cells. Immediately after RNase A injection, FUS-GFP condensed into many liquidlike droplets (Fig. 3A, fig. S9, and movie S1), and this effect was not due to a general loss of nuclear integrity (figs. S10 and S11). As an alternative approach to decrease the RNA/protein ratio, we injected purified FUS-GFP into the nucleus, which led to an immediate increase in the number and size of nuclear FUS assemblies (fig. S12). RNase A microinjection into the nucleus also triggered rapid phase separation of hnRNPA1, EWSR1, TDP43, and TAF15 (figs. S13 and S14). To investigate whether FUS forms complexes with RNA in living cells, we used fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS). We identified two populations of FUS, one slow moving and one fast moving (details are in supplementary methods). We estimate that the amount of slow FUS in the nucleus is 10 times as high as that in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3, B to D; fig. S15, A to E; and supplementary methods). The fraction of slow FUS in the nucleus was decreased by the mutation of RNA binding domains in FUS (generating variants FUS-mutRRM/ZnF and FUS-mutRGG2) and was further decreased by the removal of all RNA binding domains (generating variant FUSPLD) (Fig. 3, E and F, and figs. S15, F to I; S16; and S17). These results indicate that a large fraction of nuclear FUS is complexed with RNA. To further investigate the solubilizing role of RNA, we performed genetic experiments with transfected FUS-GFP–encoding plasmids. We observed that the number of nuclear FUS assemblies was directly proportional to the nuclear FUS concentration (Fig. 3G). We further found that FUS variants with a weaker capacity to bind RNA generally formed a higher number of assemblies (Fig. 3, H to J, and figs. S16 and S17). Thus, reduced RNA binding directly affects the solubility and decreases the saturation concentration at which FUS phase-separates.

Fig. 3. RNA keeps prion-like RBPs in a soluble state in the nucleus.

(A) Montage of a HeLa cell expressing FUS-GFP after microinjection with RNase A. Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) HeLa cells expressing FUS-GFP. White lines indicate cell outlines, orange lines indicate nuclear outlines, and boxes indicate regions of FCS measurements. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) Autocorrelation curves obtained from FCS of FUS-GFP. τ is the autocorrelation time and Gn (τ) is the autocorrelation function, which is normalized to the amplitude of 1 at τ = 10 ms. (D) Quantification of the amount of slow FUS (methods are described in supplementary materials). Error bars represent SD. **P < 0.01. (E) Autocorrelation curves obtained from FCS of FUS-GFP variants in the nucleus. wt, wild type; mutRGG, mutations in the first RGG; mutRRM/ZnF, mutations in the RRM and zinc finger (ZnF); PLD, lacks all the RNA binding domains. (F) Quantification of slow FUS in the nucleus, obtained from two-component fits of the curves in (E) (methods are described in supplementary materials). Error bars represent SD. tD2, decay time for slow FUS. (G) HeLa cells showing variable FUS-GFP expression. Scale bar, 5 μm. (H) HeLa cells expressing different FUS-GFP variants with mutations in RNA binding domains (fig. S16). Scale bar, 5 μm. (I) Number of nuclear FUS-GFP assemblies per cell (n > 30) as a function of mean protein intensity (AI). Shading represents the confidence interval of the fitted linear regression model, which is plotted as a solid line. (J) Number of cells with more than 100 nuclear assemblies. n > 100 cells. Error bars represent SD. In (F) and (J), *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.01 in comparison with the wild type.

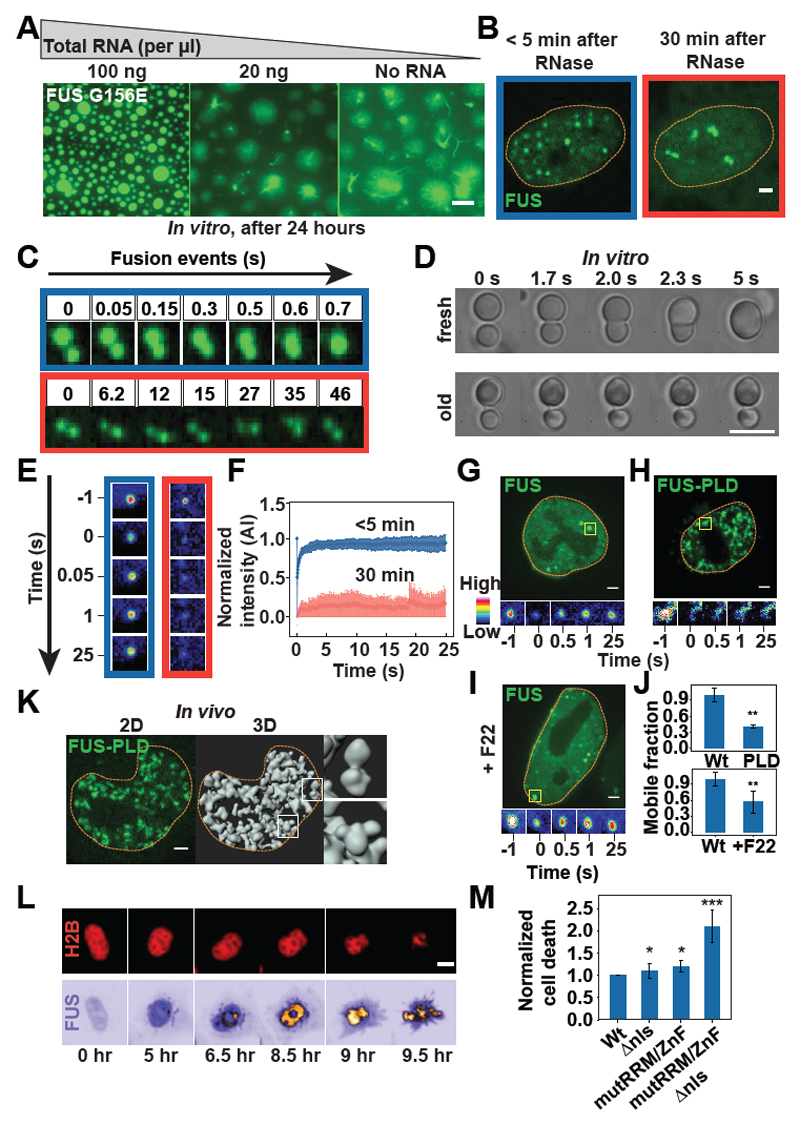

We showed previously that FUS in vitro initially forms liquid-like assemblies, but these mature into more solid-like gels and fibrils over time (5). These solid-like states are reminiscent of pathological aggregates in ALS (8, 9). Thus, we next tested whether the addition of RNA prevents the formation of fibrils in vitro. The addition of RNA kept the droplets in a soluble state, and fibers were not seen (Fig. 4A). We next investigated whether RNA also changes the material properties of FUS assemblies in vivo. We set up an in vivo aging assay in which we microinjected RNase A into HeLa cells and then monitored the dynamics of the liquid-like drops. After about 30 min, the FUS drops no longer fused (Fig. 4, B and C, and movie S2) but stuck together in large clusters, similar to phenotypes seen previously in vitro (Fig. 4D and movie S3). A change in the material properties was also evident from photobleaching experiments (Fig. 4, E and F, and fig. S18, A and B). Similar results were obtained for TDP43, but the transition was much faster (fig. S19 and movie S4). We next used a genetic approach to test how RNA binding affects the dynamics of FUS in vivo. Complete abrogation of RNA binding resulted in a marked decrease of mobile FUS (Fig. 4, G, H, and J, and fig. S18C) and the formation of sticky droplet clusters (Fig. 4K). Lastly, we used a chemical approach with the dye F22 to reduce RNA binding (23). In F22-treated cells, the fraction of RNA-bound FUS was strongly diminished (fig. S20 and supplementary methods), and this caused a strong reduction in the mobile fraction of FUS (Fig. 4, I and J, and fig. S18, E and F). Together, these findings show that RNA keeps condensates formed by prion-like RBPs in a dynamic state and prevents the formation of solid assemblies that can cause disease.

Fig. 4. RNA regulates aberrant liquid-to-solid phase transitions of prion-like RBPs.

(A) In vitro phase-separated Gly156→Glu (G156E) variant FUS–GFP in the absence or presence of total RNA after 24 hours. Scale bar, 2 μm. (B) FUS-GFP–expressing HeLa cell nucleus after RNase A microinjection. Scale bar, 1 μm. (C) Montage of FUS-GFP droplets formed after RNase A microinjection. The droplets fuse in the first 5 min (blue box) but dissociate after 30 min, resulting in “sticky droplets” (red box). (D) Montage of FUS-GFP droplets formed in vitro (7 μM). The fusion of freshly formed droplets is compared with 3-hour-old droplets. Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of nuclear FUS-GFP assemblies less than 5 min (blue box) or more than 30 min (red box) after RNase A microinjection. (F) FRAP of nuclear FUS-GFP assemblies in HeLa cells after RNA degradation as shown in (B) and (E) (n > 10 cells). (G to I) FRAP of nuclear assemblies in HeLa cells expressing full-length FUS [(G) and (I)] or FUS-PLD (H). The cell in (I) was also treated with F22. Scale bars, 1 mm. (J) Mobile fraction of photobleached assemblies in (G) to (I) (n > 15 cells). Error bars represent SD. (K) Three-dimensional (3D) rendering of FUS-PLD nuclear assemblies.The insets show aberrant “sticky droplets.” Scale bar, 1 mm. (L) Time series to track the lifetime of FUS-GFP HeLa cells. H2B-mCherry was used to detect cell death. Scale bar, 5 mm. (M) Quantification of the fraction of cells undergoing cell death. Error bars represent SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 in comparison with the wild type.

To investigate how reduced RNA binding affects cell viability, we transiently transfected HeLa cells with wild-type and mutant FUS and monitored cell survival. Expressing a nuclear variant with reduced RNA binding (FUS-mutRRM/ZnF) affected the rate of cell death only slightly (Fig. 4, L and M, and fig. S16), presumably because the high nuclear RNA concentration compensated for the genetic defect. However, targeting the very same variant to the cytoplasm by removing the nuclear localization sequence (NLS; generating FUS-mutRRM/ZnF∆NLS) led to a strong increase in cell death, which was likely caused by the high propensity of this variant to form solid aggregates (figs. S21 to S23). Importantly, this increase was not observed for a cytosolic variant of FUS with normal RNA binding (FUS∆NLS). Thus, we conclude that excessive phase separation in the cytoplasm owing to low RNA levels induces a pathological state that leads to cell death.

One of the key questions in protein misfolding diseases caused by prion-like RBPs is why these proteins aggregate in the cytoplasm rather than the nucleus. In this study, we have shown that this pattern is due in part to different RNA concentrations in the cytoplasm and the nucleus. More specifically, the higher RNA concentration in the nucleus suppresses phase separation of prion-like RBPs, and the lower concentration in the cytoplasm stimulates phase separation. Therefore, by keeping the proteins in the nucleus, the cell ensures that they are in a soluble and nontoxic state, shuttling them out of the nucleus only upon stress. After the removal of stress, the proteins shuttle back into the nucleus, where they are again kept in a soluble and well-mixed state. The consequence is that any insult that prolongs the stress will tend to increase the propensity for aggregation because it prolongs the time that these proteins spend in the cytoplasm (fig. S24).

Our data also have important implications for the control of phase separation in cells. We find that paraspeckles are likely induced by locally concentrating Neat1 RNA, which has a strong affinity for FUS. Similar phenomena have been seen for nucleoli, which depend on local production of ribosomal RNA (24). Therefore, at least in the nucleus, local production of RNAs with high affinity for specific RBPs may provide the specificity to induce phase separation in a system buffered by nonspecifically interacting RNA. Thus, the phase behavior of FUS in the nucleus is likely controlled by many different types of specific and nonspecific RNAs. This situation does not apply to the cytoplasm. There, the RNA concentration is only slightly higher than the concentration required to suppress phase separation in vitro and there is no buffering of phase separation by RNA. This environment results in a much higher propensity of FUS to phase-separate. However, it also increases the tendency of FUS to form cytotoxic solid-like aggregates. Large amounts of RNA have been shown to suppress the toxicity of prion-like RBPs (25–28). Moreover, there are many cases of familial ALS in which mutated prion-like RBPs mislocalize to the cytoplasm and form cytotoxic aggregates. For example, mutations in FUS have been shown to increase its cytoplasmic concentration, thus causing the formation of aberrant solid-like aggregates (8, 9, 29–31). We predict that local changes in RNA levels or RNA binding abilities of proteins are frequent causes of age-related protein misfolding diseases.

One Sentence Summary.

RNA regulates the phase behavior and prevents pathological aggregation of RNA-binding proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of MPI-CBG for discussions; B. Borgonovo (chromatography facility); R. Wegner (protein expression and purification facility); A. Bogdanova for providing vectors; M. Leuschner and A. Ssykor for preparing BAC lines; J. Peychl, B. Nitzsche, and B. Schroth-Diez (light microscopy facility); C. Andree and C. Möbius (Technology Development Studio); J. Jarrells (DNA microarray facility); the FACS facility; and D. Dormann and E. Bogaert for providing reagents. Funding: We acknowledge funding from the Max Planck Society, the ERC (nos. 725836 and 643417), the BMBF (01ED1601A and 031A359A), and the JPND (CureALS). S.M. was supported by a fellowship of the Humboldt Foundation (3.5-INI/1155756 STP), L.M. by the Hans und Ilse Breuer Stiftung, and J.G.-B. by an EMBO fellowship (ALTF 406-2017).

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.M. and S.A. designed and coordinated the project. J.W. performed in vitro experiments with RBPs, D.K.P. performed FCS experiments, J.G.-B. performed the RNA immunoprecipitation, and T.F. performed the RNA binding assay. D.R., A.P., and S.R. generated plasmids. I.P. generated HeLa lines. L.M. and J.S. provided induced pluripotent stem cell–derived cell lines. M.B. analyzed the cell viability assay. M.J. performed optical tweezer experiments. Y.-T.C. provided the dye F22. S.M., A.A.H., and S.A. drafted the manuscript with input from P.T. All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation.

Competing interests: The dye F22 was covered by U.S. patent US 7790896 B2 awarded to Y.-T.C. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References

- 1.Banani SF, Lee HO, Hyman AA, Rosen MK. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:285–298. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin Y, Brangwynne CP. Science. 2017;357 doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4382. eaaf4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.March ZM, King OD, Shorter J. Brain Res. 2016;1647:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel A, et al. Cell. 2015;162:1066–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molliex A, et al. Cell. 2015;163:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mateju D, et al. EMBO J. 2017;36:1669–1687. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor JP, Brown RH, Jr, Cleveland DW. Nature. 2016;539:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nature20413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vance C, et al. Science. 2009;323:1208–1211. doi: 10.1126/science.1165942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwiatkowski TJ, Jr, et al. Science. 2009;323:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann M, et al. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumann M, et al. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:137–149. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0477-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng H, Gao K, Jankovic J. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:337–348. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dormann D, et al. EMBO J. 2010;29:2841–2857. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barmada SJ, et al. Neurosci J. 2010;30:639–649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4988-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaper DC, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:1539–1557. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scekic-Zahirovic J, et al. EMBO J. 2016;35:1077–1097. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma A, et al. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11634. 10465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Z, et al. PLOS Biol. 2011;9:e1000614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox AH, Nakagawa S, Hirose T, Bond CS. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;43:124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saha S, et al. Cell. 2016;166:1572–1584.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elbaum-Garfinkle S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:7189–7194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504822112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, et al. Mol Cell. 2015;60:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, et al. Chem Biol. 2006;13:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry J, Weber SC, Vaidya N, Haataja M, Brangwynne CP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E5237–E5245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509317112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitamura A, et al. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep26791. 19230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishiguro T, et al. Neuron. 2017;94:108–124.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Y-C, et al. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e64002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayala YM, et al. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3778–3785. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabatelli M, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4748–4755. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dini Modigliani S, Morlando M, Errichelli L, Sabatelli M, Bozzoni I. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5335. 4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shang Y, Huang EJ. Brain Res. 2016;1647:65–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]