Abstract

Objective

To compare the characteristics, quality and treatment effects of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) by individual patient data (IPD) availability, in trials eligible for 18 IPD meta-analyses (MA).

Design

Trial characteristics, risk of bias (RoB) and hazard ratio (HR) for overall survival were extracted from IPD-MA publications and/or RCTs publications. Data for the RoB assessment were extracted for a subset of 73 RCTs. Two investigators blinded to whether IPD was available or not evaluated the RoB for these trials. Treatment effects were compared using ratios of global HRs (RHRs) of IPD-unavailable trials and IPD-available trials. RHR were pooled using a fixed-effect model.

Data sources

We examined the IPD availability for each trial eligible for each IPD-MA; when the IPD was not available for a trial, we used information from published sources.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

We selected all published IPD-MAs conducted at Gustave Roussy and the RCTs eligible for each.

Results

349 RCTs (73 018 patients) from 18 MAs were eligible: 60 RCTs (5890 patients) had unavailable IPD and 289 RCTs (67 128 patients) had available IPD. The main reason for IPD unavailability was data loss by investigators. IPD-unavailable trials were smaller (p<0.001), more often monocentric (p<0.001) and non-international (p=0.0004) than IPD-available trials. Geographical areas differed (p=0.054) between IPD-unavailable IPD-available trials. RoB was higher in IPD-unavailable RCTs for random sequence generation (p=0.007) and allocation concealment (p=0.006). The HR and 95% confidence interval (CI) for overall survival were extractable from publications in 23/60 IPD-unavailable trials included in 10 different MAs. Treatment effects were significantly greater for IPD-unavailable trials compared with IPD-available trials (RHR=0.86 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.98)).

Conclusions

IPD-unavailable RCTs were significantly different from IPD-available RCTs in terms of trial characteristics and were at greater RoB. IPD-unavailable RCTs had a significantly greater treatment effect.

Keywords: meta-analysis, individual patient data, randomized clinical trials, risk of bias, quality, missing data

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First work exploring potential bias in an individual patient data meta-analyses (IPD-MA) due to missing IPD from eligible trials.

We examined 18 IPD-MA that included 349 eligible trials (72 818 patients).

This set was limited to IPD-MAs conduced in oncology by our team.

Introduction

Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses (MA) of RCTs based on systematic review provide the highest level of evidence for assessing intervention effectiveness. There are two types of MAs: aggregated data MA and individual patient data MAs (IPD-MAs). The first and more common type is based on aggregated data (ie, data from people enrolled in a trial have been statistically combined) extracted from public sources (eg, journal publications). IPD-MA is based on original data from each patient included in each RCT. In collaborative work, the trial data sets are typically provided to a coordinating group by trial investigators.1–3

IPD-MAs of RCTs have many advantages compared with aggregated data MAs. First, they limit selective reporting when they include unpublished RCTs, excluded patients and unpublished or misreported outcomes.4 5 Moreover, access by the MA coordinators to the IPD allows checking of data quality and integrity and correction and completion of the data in collaboration with investigators.6 7 Finally, by standardising coding across RCTs and accessing data on covariates, IPD-MAs allow investigators to study new research questions, such as potential interactions between patient characteristics and the treatment effect.2 3 5

Because they necessitate additional collection, verification, correction and standardisation of data, and interactions with the investigators involved in the MA, IPD-MAs require more resources than aggregated data MAs. Furthermore, not all eligible RCTs may have IPD available, which can introduce a selection bias if IPD-unavailable RCTs differ from IPD-available RCTs, either in treatment effect or factors possibly related to the treatment effect.8 To compensate for the lack of IPD, MA researchers may elect to extract aggregated data from the publications of IPD-unavailable trials, although we do not at Gustave Roussy. For substitution of IPD by aggregated data to be justifiable, however, meta-analysable data must be available in publications and the extracted aggregated data must be from unbiased trials. Then, their quality should be evaluable.

Our objective was to examine the IPD-MAs conducted by the Gustave Roussy Meta-analysis Unit, which has served as the coordinating group, to estimate the proportions of eligible RCTs in each MA that were IPD unavailable and IPD available, to compare the trial characteristics and risk of bias (RoB) (trial ‘quality’) of IPD-unavailable with IPD-available RCTs and to compare, across the MAs, summary treatment effects based on the pooling of published aggregated data from IPD-unavailable RCTs and summary treatment effects from the IPD-MA publications.

Methods

Eligible meta-analysis and RCT selection

Gustave Roussy Meta-analysis Unit has coordinated and published 18 IPD-MAs based on RCTs since 19909–29; all aimed to estimate the effect of a treatment combination on overall survival in cancer patients (see online supplementary etable 1). Every MA we have published was eligible for our study. RCT selection for each MA was based on systematic review and has been previously described.9–29

bmjopen-2017-020499supp001.docx (59KB, docx)

Standard procedures6 were used to check the RCT data sets sent to us for the IPD-MA, in collaboration with the investigators (online supplement). If we had major doubts about a trial methodological quality based on its protocol and our re-analyses of its IPD (see online supplementary etable 2) (eg, allocation concealment, missing data), we had the option of excluding it from the IPD-MA (‘excluded IPD-available RCTs’). For each MA we conducted, we described all eligible RCTs, regardless of whether they were IPD-available, IPD-unavailable or excluded IPD-available RCTs (see online supplementary etable 1). All the publications of 18 IPD-MAs included only IPD-available RCTs for treatment evaluation, however.

Data collection

For every eligible RCT, we collected the following data from the available publications: number of randomised patients, date of first patient randomised, date of publication, countries involved, type of publication (eg, conference abstract), nature of funding, whether the RCT was multicentre or not and whether it was international or not. This information was extracted from RCT publications for IPD-unavailable RCTs and from IPD-MA publications for RCTs with IPD supplemented by the RCT publications and/or our archives if necessary.

To assess the RoB in IPD-unavailable RCTs and compare it with the risk in IPD-available RCTs, we first selected RCTs reported in English as full-text articles30 and excluded conference abstracts and unpublished RCTs because methodological information was insufficient most of the time.31 32 Second, IPD-available RCT publication(s) were selected to match with IPD-unavailable RCT publication on MA to which they belonged and the period when the RCT was performed based on the date of randomisation of the first patient (before 1997/1997 and after). If more than two IPD-available RCTs by IPD-unavailable RCT were available in the strata defined by the two above criteria, we used the Excel ALEA function to randomly select publication of two IPD-available RCTs by IPD-unavailable RCT publication. The number of IPD-available RCT publications selected was limited because of time constraints. Two investigators blinded to whether IPD was available or not extracted data from the selected publications for both IPD-unavailable and the sample of IPD-available RCTs to evaluate RoB using the Cochrane tool.8 Five dimensions were studied and graded as low risk, high risk or unclear: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of personnel and participants, blinding of outcome assessment and incomplete outcome data. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third investigator.

For IPD-unavailable RCTs, we extracted the HR of treatment effect on overall survival and its 95% CI from each RCT publication. If the hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were not reported, we calculated them using one of two validated methods depending on available information.33 34 For IPD-available RCTs, we extracted the global HR on overall survival and its 95% CI from the MA publication, using the most recent when there was an updated IPD-MA.

Statistical analysis

We examined the statistical significance of the association between IPD availability and RCT characteristics and reported RoB dimensions using a χ2 test or a Fisher exact test for categorical variables, and a Student’s t-test or a Wilcoxon test for continuous variables.

To be comparable to our IPD-available MAs, we calculated global HRs of IPD-unavailable RCTs using the natural logarithm (ln) of the HR and its variance, based on published data, for each MA using a fixed effect model.5 35 We calculated the ratio of the global HR of IPD-unavailable RCTs to the global HR of IPD-available RCTs (ie, the ratio of HR (RHR)36) for each MA. We also calculated a global RHR across MAs and its 95% CI was calculated using a fixed effect model. An RHR less than 1 indicates that IPD-unavailable RCTs present a larger treatment effect estimate than IPD-available RCTs. The heterogeneity of the RHR was assessed with a χ2 test and the I2 statistic. A random effect model was used in cases of statistically significant heterogeneity (p<0.10). Since RCTs with high RoB are excluded from our published MA (ie, ‘excluded IPD-available RCTs’, noted above) and therefore not included in the global treatment effect of the IPD-available RCTs, a sensitivity analysis of the comparison of treatment effect across IPD-unavailable and IPD-available RCTs was performed without the IPD-unavailable RCTs considered at high RoB for at least one dimension of the RoB tool.

Analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and R software.37

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in this study.

Results

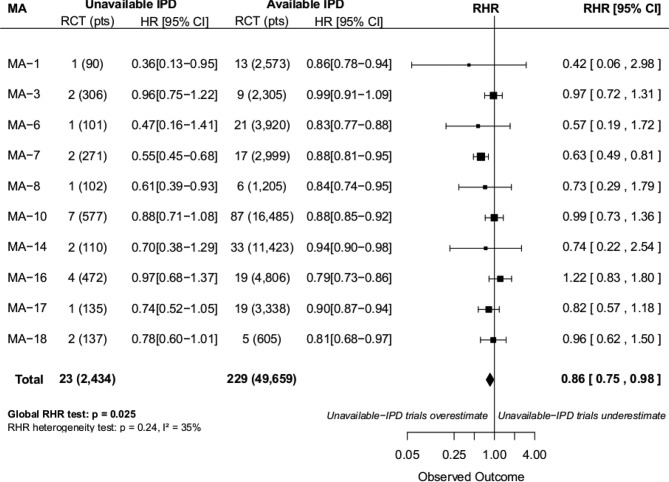

Three hundred and forty-nine RCTs (73 018 patients included between 1965 and 2010) were eligible for at least one of the 18 MAs. IPD from 60 RCTs (5890 patients) were unavailable for our published IPD-MAs (figure 1): 32 (53%) because the data were lost by the investigators, 19 (32%) because the investigators could not be contacted, 2 (3%) because the investigators refused to share the RCT data and 7 (12% and 638 patients) for an unknown reason. Of the 289 IPD-available RCTs, 18 RCTs (ie, excluded IPD-available RCTs) were excluded from the published MAs after IPD checking due to major doubts on quality using tools different from the Cochrane RoB tool (figure 1). Reasons for their exclusions are presented in online supplementary etable 2. The main reason was suspicion of biased randomisation (10/18 (56%) excluded RCTs). In the end, 271 RCTs were included in the 18 MAs (figure 1). The 18 excluded IPD-available RCTs have been included only in the analysis of the next paragraph.

Figure 1.

Flow chart. IPD, individual patient data; MA, systematic review and meta-analysis; OS, overall survival; RCT, randomised controlled trial. *Other MAs are MAs without one IPD-unavailable trial. **Corresponding MAs are MAs including at least one IPD-unavailable trial with extractable HR for OS.

Comparison of trial and report characteristics of IPD-available and IPD-unavailable RCTs

Table 1 compares the trial characteristics of the 60 IPD-unavailable RCTs and the 289 IPD-available RCTs. IPD-unavailable RCTs were significantly smaller, more often single centre and non-international. They were also published more often as conference abstracts only and in languages other than English. Although funding of the trial was less often reported in IPD-unavailable trials (p<0.001), it was reported less than 50% of the time for both IPD-available and IPD-unavailable RCTs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomised trials eligible in one or more of the considered meta-analyses according to the availability of individual patient data (IPD)

| Characteristics of trials | IPD-unavailable (n=60) |

IPD-available (n=289) |

P values |

| Number of patients, No (%) | |||

| <50 | 11 (18) | 25 (9) | <0.001* |

| 50–99 | 24 (40) | 63 (22) | |

| 100–149 | 16 (27) | 45 (16) | |

| 150–199 | 4 (7) | 32 (11) | |

| 200–249 | 4 (7) | 30 (10) | |

| 250–349 | 1 (2) | 43 (15) | |

| ≥350 patients | 0 (0) | 51 (18) | |

| Date first patient randomised, No (%) | |||

| Before 1980 | 11 (18) | 32 (11) | 0.29* |

| 1980–1984 | 4 (7) | 53 (18) | |

| 1985–1989 | 4 (7) | 62 (21) | |

| 1990–1994 | 8 (13) | 59 (20) | |

| 1995–1999 | 11 (18) | 53 (18) | |

| 2000–2009 | 9 (15) | 27 (9) | |

| Missing | 13 (22) | 3 (1) | |

| Date of publication, No (%) | |||

| Before 1985 | 9 (15) | 18 (6) | 0.24* |

| 1985–1989 | 10 (17) | 37 (13) | |

| 1990–1994 | 6 (10) | 52 (18) | |

| 1995–1999 | 8 (13) | 51 (18) | |

| 2000–2005 | 17 (28) | 61 (21) | |

| 2005–2014 | 8 (13) | 56 (19) | |

| Unpublished | 2 (3) | 14 (5) | |

| Number of centres, No (%) | |||

| One or two centres | 42 (70) | 116 (40) | <0.001† |

| More than two centres | 14 (23) | 170 (59) | |

| Missing | 4 (7) | 3 (1) | |

| International trial, No (%) | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 53 (18) | <0.001† |

| No | 58 (97) | 236 (82) | |

| Missing | 2 (3) | ||

| Authors’ location, No (%) | |||

| Europe | 25 (42) | 139 (48) | 0.054‡ |

| North America | 13 (22) | 72 (25) | |

| Asia | 21 (35) | 51 (18) | |

| Central or South America | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | |

| Oceania | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | |

| Africa | 1 (2) | 3 (1) | |

| Transcontinental | 0 (0) | 13 (5) | |

| Type of publication, No (%) | |||

| Full-text article | 38 (63) | 250 (87) | <0.001† |

| Conference abstract | 20 (33) | 26 (9) | |

| Unpublished | 2 (3) | 13 (5) | |

| Language of publication (if trial published), No (%) | |||

| English | 47 (81) | 268 (97) | <0.001‡ |

| Non-English | 11 (19)§ | 8 (3)¶ | |

| Reporting of funding, No (%) | |||

| No | 50 (83) | 147 (51) | <0.001‡ |

| Yes | 10 (17) | 142 (49) | |

| Nature of funding (if funding reported), No (%) | |||

| Independent from industry | 9 (90) | 98 (69) | 0.28‡ |

| Related to industry | 1 (10) | 44 (31) |

Some trials were included in more than one MA, but they were counted only once in the table.

The available IPD group includes the 18 trials excluded from the meta-analyses for quality reasons. IPD: Individual patient data.

*Wilcoxon test on the continuous variable.

†Χ2 test.

‡Fisher exact test. Missing values are not taken into account.

§Eight trials published in Chinese, two in German, one in Korean.

¶Four trials published in Japanese, one in Chinese, one in Thai, one in French and one in Italian.

Comparison of reported quality of IPD-available and IPD-unavailable RCTs

We found that 27 IPD-unavailable RCTs from 11 MA were published as full-text article in English, and 232 IPD-available RCTs (figure 1). Twelve strata were created based on meta-analysis and time period. They were used to match the 27 IPD-unavailable RCTs with 151 IPD-available RCTs. Because of insufficient RCTs in the IPD-available group in three meta-analyses, the matching was performed in a 1:1 ratio for eight IPD-unavailable RCTs. For 17 others, a random selection of IPD-available RCTs was performed to obtain a 1:2 ratio. For the last two IPD-unavailable RCTs, only four IPD-available RCTs were available. At the end, 46 IPD-available trials were matched. RCTs with a low RoB for random sequence generation and allocation concealment were less frequent, and RCTs with unclear risk were more frequent, in the IPD-unavailable RCTs compared with the IPD-available RCTs (table 2).

Table 2.

Quality of randomised trials by IPD availability, as obtained from English language full-length publications

| Dimensions of the Cochrane risk of bias tool | RCTs in MA | P values | |

| IPD-unavailable (n=27) |

IPD-available* (n=46) |

||

| Random sequence generation, No (%) | |||

| Low risk | 9 (33) | 32 (70) | 0.007† |

| High risk | 1 (4)‡ | 0 (0) | |

| Unclear | 17 (63) | 14 (30) | |

| Allocation concealment, No (%) | |||

| Low risk | 2 (7) | 17 (37) | 0.006§ |

| High risk | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Unclear | 25 (93) | 29 (63) | |

| Blinding of personnel and participants, No (%) | |||

| Low risk¶ | 27 (100) | 46 (100) | – |

| Blinding of outcome assessment, No (%) | |||

| Low risk¶ | 27 (100) | 46 (100) | – |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), No (%) | |||

| Low risk | 7 (26) | 18 (39) | 0.21§ |

| High risk | 11 (41) | 10 (22) | |

| Unclear | 9 (33) | 18 (39) | |

*Sample paired with unavailable IPD trials on the first inclusion period and the meta-analysis which included them, with a 2:1 ratio.

†Chi square test.

‡Classified at high risk because of a randomization by pairs. Indeed one patient in two was randomized, the other was “assigned the alternate treatment of the prior pair-mate”.

§Fisher exact test.

¶Outcome examined was overall survival.

IPD, individual patient data; RCT, randomised clinical trial.

Blinding of personnel and participants and blinding of outcome assessment were at low RoB in all cases, because outcome assessed was overall survival, an objective outcome little impacted by lack of blinding. There was no statistically significant difference between IPD-unavailable and IPD-available RCTs in terms of incomplete or missing outcome data,.

Availability of treatment effect estimate for survival in IPD-unavailable RCTs publications

Only 23/60 IPD-unavailable RCTs (38%), which included 2 434/5 890 patients (41%), had an extractable HR (ie, treatment effect estimate) (see online supplementary etable 3). Extraction was not possible in 37 other trials because of missing or incomplete HR information. RCTs without an extractable HR were more often published as abstracts and less often published in English than RCTs with extractable HR. None of the 20 abstracts had extractable HR (see online supplementary etable 4).

Comparison of treatment effect across IPD-available and IPD-unavailable RCTs

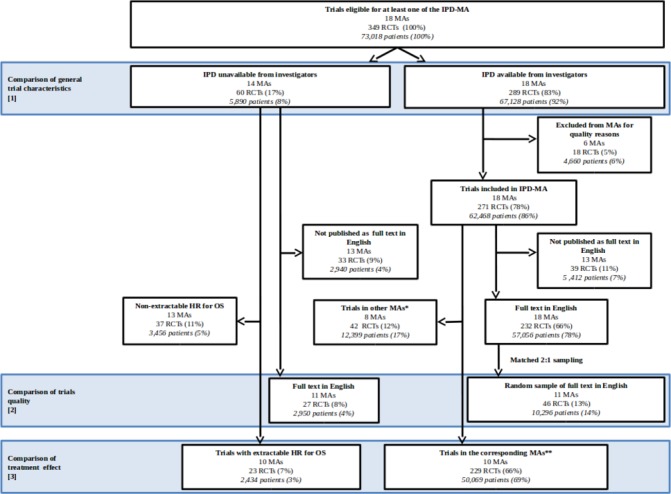

The 23 IPD-unavailable RCTs with an available treatment effect measure were included in 10 different MAs. In 9/10 MAs, the RHR was less than 1 (IPD-unavailable RCTs are associated with a greater treatment effect estimate than IPD-available RCTs). Across all MAs, IPD-unavailable RCTs observed a 14% greater treatment effect than what was observed in IPD-MAs (global RHR=0.86; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.98, p=0.025). There was no significant heterogeneity (p=0.24) among meta-analysis results (figure 2). After exclusion of the 11 IPD-unavailable RCTs considered at high RoB (the sensitivity analysis), the global RHR was 1.01 (0.84–1.21).

Figure 2.

Forest plot for ratio of HR (HR in individual patient data (IPD)-unavailable trials reported to HR in IPD meta-analyses (MAs)). Note that for 5 out of 18 MAs (MA-2, MA-11, MA-12, MA-13 and MA-15), data from all trials were available; for three other, it was not possible to extract an HR from the publications of the unavailable trials (MA-4, MA-5 and MA-9). Analysis on the MA with available IPD did not include trials excluded for quality reasons. For the available IPD MA, results are based on the corresponding publication and 13 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with IPD were excluded for quality reasons. The MAs and the status of the corresponding RCTs are described in online supplementary etable 1. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; pts, patients; RHR, ratio of HR.

Discussion

In the 18 IPD-MAs coordinated by Gustave Roussy, IPD from 60/349 (17%) eligible trials and 5890/66 928 (8%) eligible patients were not made available to us. Combining IPD with aggregate data could lead to biased estimates of a treatment effect if the trials with aggregate data only (IPD-unavailable) are different from IPD-available trials. Regrettably, based on reported information, IPD-unavailable trials are different in both their characteristics and RoB. IPD-unavailable RCTs were smaller, more often single centre and non-international. They were also published more often as conference abstracts only and in languages other than English. We found that the RoB in IPD-unavailable RCTs was greater than the RoB in IPD-available RCTs.

In our study, 37/60 (62%) of IPD-unavailable RCTs did not contribute to the summary effect estimate because we could not obtain an HR. Thus, we do not know whether the results from these trials are higher, lower or the same as the estimate we obtained for the 23 trials with HR data. We are surprised that overall survival could not be assessed for so many trials, given that it is one of the most important cancer trial endpoints.38 39

For the other 23/60 RCTs, we inferred from the RHR that IPD-unavailable RCTs are associated with a larger treatment effect estimate than IPD-available RCTs, that is, a relative increase of 14% of treatment effect on overall survival was observed in the IPD-unavailable trials, even though our MAs were in the field of oncology in which treatment effect are often small. When, in a sensitivity analysis, we removed 11/23 trials assessed at high RoB from the analysis, RHRs for IPD-unavailable RCTs compared with IPD-available RCTs implied no discernible difference between the two effect estimates.

In another study of 31 IPD-MAs,40 not including any of ours, the median proportion of IPD-available RCTs across MAs was 91% (range 60%–100%) compared with 85% (range 71%–100%) in our study. In our study, IPD-availability is lower in RCTs published as conference abstract only than in those published as full-text article (table 1). Then, IPD-availability rate may depend on whether the ‘grey literature’ (ie, meeting abstracts and communications) has been searched or not. According to Ahmed et al,40 only 9/31 meta-analyses mentioned grey literature compared with 100% in our MAs. This may explain our lower rate of available data.

Should we combine IPD-unavailable information (aggregated HRs from individual trials) with IPD-available information? Although some data are better than no data, including aggregated data in the MAs would not have solved entirely the problem of missing data. Only 23/60 (38%) of the IPD-unavailable trials provided a meta-analysable treatment effect estimate. Other treatment effect estimates other than HR, such as comparison of survival rates or comparison of median survival times, were not considered since they are less appropriate for survival endpoints.4 8 In addition, IPD-unavailable trials had different characteristics and a higher RoB. This is not to say that IPD-available trials are never at a RoB. Many trials in our sample, including IPD-available trials, did not report sufficient information to evaluate the RoB properly, as shown previously by others.41 What we do not know is whether lack of clarity in the report reflects poorer methodological quality of the trial.42 43 By checking IPD and exchanging with investigators, it was possible to confirm or complete the published information for the IPD available trials. Not combining IPD-unavailable information with IPD-available information is open to selection bias. In our experience, when an IPD-MA and an aggregated MA were performed at the same time, there were more trials and patients included in the IPD-MA, and then the selection bias may be lower for IPD-MA than for the corresponding aggregated MA.44–47

Our study has several strengths. First, it is the first study, to our knowledge, to study the characteristics of IPD-unavailable RCTs compared with IPD-available RCTs and their treatment effects. Second, the standardised methods used both in selecting the RCTs to be included in the MA and in the methods of our MA assure minimisation of bias and meta-bias. Third, we examined 18 MAs and 349 eligible RCTs, a large sample that contributes robustness to our results. Last, our results are consistent from one MA to the other.

The main limitation of this study is that we included only MAs with overall survival data, performed by our group, in oncology. But based on our collaboration with other groups performing IPD-MAs10 15 16 48 and our participation in the development of the guidelines for IPD-MAs,2 6 we think our IPD-MA methods correspond to those used by other teams. Then, our results would be applicable to other topics where overall survival is the main outcome, such as cardiovascular disease. Other studies are needed to confirm applicability, however. Another limitation is the lack of evaluation of the impact of the exclusion of 18 IPD available RCTs on treatment effect due to the loss of the data of 7 of them. But results similar to the IPD-unavailable RCTs, in particular those with high RoB, are expected since the main reason for exclusion was the high RoB for randomisation. Lastly, the small number of recent trials in our sample could affect reporting of trials characteristic, RoB and treatment effects. However, unavailable IPD are still observed in current MAs our group is performing, and the proportion of unavailable IPD has not varied with the date of randomisation of the first patient in each RCT.

Our results indicate that IPD-unavailable RCTs compared with IPD-available RCTs report a higher treatment effect.

There are multiple reasons that may explain the difference in the observed treatment effect between aggregated IPD-unavailable data and IPD-available data RCTs.

IPD-unavailable RCTs were significantly smaller than IPD-available RCTs and if they were included in an MA, they could contribute to a biased treatment effect estimate. Indeed, it has been previously observed on aggregated data MAs that small studies tended to show a larger effect size than bigger studies49 50; the reason for this overestimation remains unclear.

As we saw in our sensitivity analysis, IPD-unavailable RCTs could be at higher RoB than IPD-available RCTs, and omission of trials at high RoB means eliminating the overestimation of treatment effect.

We saw that characteristics of IPD-unavailable RCTs compared with excluded IPD-available RCTs (online supplementary etable 2) share common traits: they tend to be non-international single-centre RCTs, mainly Asian, and are frequently not published in English.

It has been previously observed that trials with higher RoB or lower methodological quality tend to report greater effect sizes.51 52

Since IPD-available data sets are checked, completed and/or corrected if needed by the coordinating group in collaboration with the investigators, and IPD-unavailable aggregated data are used as published, the two sources of data are different. For example, follow-up was updated for IPD-available but not IPD-unavailable RCTs, affecting our MAs, and the shorter follow-up in IPD-unavailable trials may also explain in part the higher treatment effect observed.

We cannot exclude the possibility that at least some of IPD-unavailable information is fabricated or fraudulent since the data set is not shared.

When aggregated IPD-unavailable information is excluded from the MA, the treatment effect is conservatively estimated and the treatment effect is closer to no effect.

It is important to include all eligible RCTs in any MA. It is particularly important in cases such as ours, when the IPD-available RCTs appear to be different from the IPD-unavailable RCTs, in their characteristics, RoB, and HRs for survival. Because 60/349 (17%) of all RCTs eligible for our 18 MAs were IPD-unavailable trials, data sharing appears of utmost importance to improve reliability of MA results. Several initiatives from profit and non-profit organisation to share trial IPD or to promote it are ongoing; some of them already allowing facilitated access to trial databases.53–55 In spite of the urgent need for efficient sharing data system providing access to trial data from around the world, it will take some time before user-friendly systems that respect the rights of all stakeholders54 55 are in place. Access to the IPD from older trials may never be available.

Even if IPD becomes widely available, we recommend at least the following, relevant to our findings:

Mandatory systematic review (involving a comprehensive search for eligible trials) before meta-analysis;

A comprehensive search for published trial results should include multiple bibliographic databases and reports in all languages;

Central registration of all trials is essential for an appropriately comprehensive search of all trials (published and unpublished) eligible for a systematic review;

Systematic reviews should include evaluation of individual trial RoB, since biased trials can lead to a biased meta-analysis and use tools adapted to the type of data (ie, aggregated data or IPD). Assessment of a trial RoB can be facilitated by making trial protocols public;

Systematic reviewers should consider the potential impact of unpublished trials and selective reporting of trial information, and obtain the needed unpublished information if possible;

Meta-analysts should describe the eligible trials they found that have unavailable data (number of trials, number of patients, reasons for unavailability, precise reference). For IPD-MA, the amount of unavailable IPD and among them, proportion of summary data available and their impact on the results should be discussed.2 If the authors did not submit the data suggested, reviewers and editors should request them.1 2

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials reporting guidelines for trials56 should be endorsed by all journals and adhered to by all authors to ensure that meta-analysable data are provided in all full56 and abstract31 publications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the trial investigators who are listed in the meta-analysis publications and their patients for their contribution to the meta-analyses, basis of the current work. We are grateful to Kay Dickersin for her valuable comments on the manuscript. We thank the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, a French charity, for its financial support of the meta-analysis platform where we performed the 18 meta-analyses analysed in this work.

Footnotes

Contributors: FF participated in the conception of the work; in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; and in the writing of the article. CP and BL participated in the acquisition and interpretation of data, and in the writing of the article. JPP participated in the conception of the work; in the analysis and interpretation of data; and in the writing of the article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data are available by emailing Jean-Pierre Pignon.

References

- 1. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA 2015;313:1657–65. 10.1001/jama.2015.3656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tierney JF, Vale C, Riley R, et al. Individual Participant Data (IPD) Meta-analyses of Randomised Controlled Trials: Guidance on Their Use. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001855 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Michiels S, Piedbois P, Burdett S, et al. Meta-analysis when only the median survival times are known: a comparison with individual patient data results. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21:119–25. 10.1017/S0266462305050154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pignon JP, Hill C. Meta-analyses of randomised clinical trials in oncology. Lancet Oncol 2001;2:475–82. 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00453-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stewart LA, Clarke MJ. Practical methodology of meta-analyses (overviews) using updated individual patient data. Cochrane Working Group. Stat Med 1995;14:2057–79. 10.1002/sim.4780141902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burdett S, Stewart LA. A comparison of the results of checked versus unchecked individual patient data meta-analyses. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2002;18:619–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Higgins JPT, Freen S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pignon JP, Bourhis J, Domenge C, et al. Chemotherapy added to locoregional treatment for head and neck squamous-cell carcinoma: three meta-analyses of updated individual data. MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy on Head and Neck Cancer. Lancet 2000;355:949–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pignon JP, le Maître A, Maillard E, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol 2009;92:4–14. 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blanchard P, Bourhis J, Lacas B, et al. Taxane-cisplatin-fluorouracil as induction chemotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancers: an individual patient data meta-analysis of the meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer group. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2854–60. 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baujat B, Audry H, Bourhis J, et al. Chemotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an individual patient data meta-analysis of eight randomized trials and 1753 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;64:47–56. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blanchard P, Lee A, Marguet S, et al. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an update of the MAC-NPC meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:645–55. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70126-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bourhis J, Overgaard J, Audry H, et al. Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy in head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2006;368:843–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69121-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thirion P, Michiels S, Pignon JP, et al. Modulation of fluorouracil by leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: an updated meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3766–75. 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ 1995;311:899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arriagada R, Auperin A, Burdett S, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without postoperative radiotherapy, in operable non-small-cell lung cancer: two meta-analyses of individual patient data. Lancet 2010;375:1267–77. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60059-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aupérin A, Le Péchoux C, Pignon JP, et al. Concomitant radio-chemotherapy based on platin compounds in patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a meta-analysis of individual data from 1764 patients. Ann Oncol 2006;17:473–83. 10.1093/annonc/mdj117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rolland E, Le Chevalier T, Auperin A, et al. A1-04: Sequential radio-chemotherapy (RT-CT) versus radiotherapy alone (RT) and concomitant RT-CT versus RT alone in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Two meta-analyses using individual patient data (IPD) from randomised clinical trials (RCTs). J Thorac Oncol 2007;2(Suppl 4):S309–10. 10.1097/01.JTO.0000283093.09465.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Le Pechoux C, Burdett S, Auperin A, et al. IPD) meta-analyses (MA) of chemotherapy (CT) in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Thorac Oncol 2008;3(Suppl 1):S20. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aupérin A, Le Péchoux C, Rolland E, et al. Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2181–90. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aupérin A, Le Péchoux C, Rolland E, et al. Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2181–90. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fizazi K, Le Maitre A, Hudes G, et al. Addition of estramustine to chemotherapy and survival of patients with castration-refractory prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:994–1000. 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70284-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bourhis J, Blanchard P, Maillard E, et al. Effect of amifostine on survival among patients treated with radiotherapy: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2590–7. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mauguen A, Le Péchoux C, Saunders MI, et al. Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy in lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2788–97. 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. De Ruysscher D, Lueza B, Le Péchoux C, et al. Impact of thoracic radiotherapy timing in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: usefulness of the individual patient data meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 2016;27:1818–28. 10.1093/annonc/mdw263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aupérin A, Arriagada R, Pignon JP, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. Prophylactic cranial irradiation overview collaborative group. N Engl J Med 1999;341:476–84. 10.1056/NEJM199908123410703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pignon JP, Arriagada R, Ihde DC, et al. A meta-analysis of thoracic radiotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1618–24. 10.1056/NEJM199212033272302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lacas B, Bourhis J, Overgaard J, et al. Role of radiotherapy fractionation in head and neck cancers (MARCH): an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1221–37. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30458-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hopewell S, Clarke M, Moher D, et al. CONSORT for reporting randomized controlled trials in journal and conference abstracts: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2008;5:e20 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ghimire S, Kyung E, Lee H, et al. Oncology trial abstracts showed suboptimal improvement in reporting: a comparative before-and-after evaluation using CONSORT for Abstract guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:658–66. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998;17:2815–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJ, et al. Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: reconstructing the data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:9 10.1186/1471-2288-12-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, et al. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1985;27:335–71. 10.1016/S0033-0620(85)80003-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mhaskar R, Djulbegovic B, Magazin A, et al. Published methodological quality of randomized controlled trials does not reflect the actual quality assessed in protocols. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:602–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. R Core team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2015. http://www.r-project.org/.

- 38. Gandhi GY, Murad MH, Fujiyoshi A, et al. Patient-important outcomes in registered diabetes trials. JAMA 2008;299:2543–9. 10.1001/jama.299.21.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saad ED, Buyse M. Overall survival: patient outcome, therapeutic objective, clinical trial end point, or public health measure? J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1750–4. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.6359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ahmed I, Sutton AJ, Riley RD. Assessment of publication bias, selection bias, and unavailable data in meta-analyses using individual participant data: a database survey. BMJ 2012;344:d7762 10.1136/bmj.d7762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Savović J, Jones HE, Altman DG, et al. Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:429 10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hill CL, LaValley MP, Felson DT. Discrepancy between published report and actual conduct of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:783–6. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00440-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vale CL, Tierney JF, Burdett S. Can trial quality be reliably assessed from published reports of cancer trials: evaluation of risk of bias assessments in systematic reviews. BMJ 2013;346:f1798 10.1136/bmj.f1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pignon JP, Arriagada R. Role of thoracic radiotherapy in limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: quantitative review based on the literature versus meta-analysis based on individual data. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:1819–20. 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.11.1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Burdett S, Stewart L, Auperin A, et al. Chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: an update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:924–5. 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pignon JP, Burdett S. Comment on "Survival improvement in resectable non-small cell lung cancer with (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy: results of a meta-analysis of the literature" by T. Berghmans, M. Paesmans, A.P. Meert, C. Mascaux, P. Lothaire, J.J. Lafitte, et al. [Lung Cancer 49 (2005) 13-23.]. Lung Cancer 2006;51:261–2. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Blanchard P, Ribassin-Majed L, Lee A, et al. Comment on "Chemoradiotherapy regimens for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a Bayesian network meta-analysis", published in Eur J Cancer 51 (2015), 1570-1579. Eur J Cancer 2016;56:183–5. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Piedbois P, Rougier P, Buyse M, et al. Efficacy of intravenous continuous infusion of fluorouracil compared with bolus administration in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:301 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chalmers TC. Problems induced by meta-analyses. Stat Med 1991;10:971–80. 10.1002/sim.4780100618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dechartres A, Trinquart L, Boutron I, et al. Influence of trial sample size on treatment effect estimates: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2013;346:f2304 10.1136/bmj.f2304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 1998;352:609–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chalmers TC, Celano P, Sacks HS, et al. Bias in treatment assignment in controlled clinical trials. N Engl J Med 1983;309:1358–61. 10.1056/NEJM198312013092204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Krumholz HM, Waldstreicher J. The Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project--a mechanism for data sharing. N Engl J Med 2016;375:403–5. 10.1056/NEJMp1607342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lo B. Sharing clinical trial data: maximizing benefits, minimizing risk. JAMA 2015;313:793–4. 10.1001/jama.2015.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Taichman DB, Backus J, Baethge C, et al. Sharing clinical trial data--a proposal from the international committee of medical journal editors. N Engl J Med 2016;374:384–6. 10.1056/NEJMe1515172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. Academia and clinic annals of internal medicine CONSORT 2010 statement : updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials of to. Ann Intern Med 1996;2010:727–32. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020499supp001.docx (59KB, docx)