Abstract

Oligopeptide transporters (OPTs) encode integral membrane-localized proteins and have a broad range of substrate transport capabilities. Here, 28 BrrOPT genes were identified in the turnip. Phylogenetic analyses revealed two well-supported clades in the OPT family, containing 15 BrrOPTs and 13 BrrYSLs. The exon/intron structure of OPT clade are conserved but the yellow stripe-like (YSL) clade was different. The exon/intron of the YSL clade possesses structural differences, whereas the YSL class motifs structure are conserved. The OPT genes are distributed unevenly among the chromosomes of the turnip genome. Phylogenetic and chromosomal distribution analyses revealed that the expansion of the OPT gene family is mainly attributable to segmental duplication. For the expression profiles at different developmental stages, a comprehensive analysis provided insights into the possible functional divergence among members of the paralog OPT gene family. Different expression levels under a variety of ion deficiencies also indicated that the OPT family underwent functional divergence during long-term evolution. Furthermore, BrrOPT8.1, BrrYSL1.2, BrrYSL1.3, BrrYSL6 and BrrYSL9 responded to Fe(II) treatments and BrrYSL7 responded to calcium treatments, BrrYSL6 responded to multiple treatments in root, suggesting that turnip OPTs may be involved in mediating cross-talk among different ion deficiencies. Our data provide important information for further functional dissection of BrrOPTs, especially in transporting metal ions and nutrient deficiency stress adaptation.

Keywords: BrrOPTs, Segmental duplication, Functional differentiation, Turnip

1. Background

In plants, substrate transport has been identified, with functions related to the aspects of plant survival. Transporters have specific localizations within the cell and are specialized in carrying different compounds such as nitrate, phosphate, sucrose, amino acids, peptides, hormones or metals (Koh et al., 2002, Wintz et al., 2003). Oligopeptide transporters (OPTs) are a group of membrane-localized proteins that possess a broad range of substrate transport capabilities and are thought to contribute to many biological processes (Lubkowitz, 2011). The OPT proteins belong to a small gene family in plants, which includes 17 in Arabidopsis (Koh et al., 2002), 27 in rice (Vasconcelos et al., 2008), 20 in Populus, and 18 in Vitis (Cao et al., 2011). Structurally, OPT proteins are predicted to possess approximately 16 transmembrane strands (TMS). Through detailed bioinformatic analyses of these transporters (Gomolplitinant and Saier, 2011), suggested that the 16-TMS proteins might have arisen from a 2-TMS precursor-encoding genetic element that was subject to three sequential duplication events. Given that the transporters are predicted to function in peptide uptake, the expansion or fusion of the TMS might make excellent physiological sense in evolution. Meanwhile, phylogenetic analyses revealed that (Koh et al., 2002) plant OPT members were divided into two distant clades, including the yellow stripe-like (YSL) proteins and the OPTs, based on the first characterized transporters.

The OPT proteins likely do not have a common biological function and may be involved in four different processes: long-distance metal distribution (Stacey et al., 2008), nitrogen mobilization (Koh et al., 2002, Cagnac et al., 2004, Stacey et al., 2006, Pike et al., 2009), heavy metal sequestration (Cagnac et al., 2004, Vasconcelos et al., 2008, Pike et al., 2009), and glutathione transport (Cagnac et al., 2004, Zhang et al., 2004, Pike et al., 2009). These processes may play a role in plant growth and development (Lubkowitz, 2011). The YSL transporters are involved in metal homeostasis through the translocation of metal chelates (Curie et al., 2001, Roberts et al., 2004, DiDonato et al., 2004, Koike et al., 2004, Murata et al., 2006, Aoyama et al., 2009, Lee et al., 2009, Ishimaru et al., 2010). The expression profiles of some OPT homologs have been partially described in Arabidopsis (Koh et al., 2002), rice (Vasconcelos et al., 2008), Populus, and Vitis (Cao et al., 2011). Many studies have been performed on the function of OPT gene family. In Arabidopsis, AtOPT3 transported iron (Wintz et al., 2003), AtOPT3-2 plants also accumulate excess zinc, manganese, and copper in some tissues (Stacey et al., 2008). AtOPT4 exhibited characteristics consistent with a broad substrate transporter, was able to transport a diverse range of tetra- and pentapeptides but not GSH (suggesting that this protein has a broad range of substrates), and is specific for peptides yet (Koh et al., 2002, Osawa et al., 2006). Moreover, the AtOPT5 mutant system accumulates Pb at levels similar to wild-type (Lubkowitz, 2011), AtOPT6 also plays a role in mediating phytotoxicity caused by heavy metals, such as cadmium (Cagnac et al., 2004). In rice, OsYSL2 (Ishimaru et al., 2010) is essential for the long-distance transport of iron; also, OsOPT7 (Zheng et al., 2009) genes were reported to be involved in long-distance iron distribution. OsYSL18 in the OPT gene family is involved in the transportation of Fe(III)-chelates (Lubkowitz, 2011, Roberts et al., 2004, Aoyama et al., 2009). In maize, YSL1 encodes a membrane protein directly involved in Fe(III) uptake (Curie et al., 2001, Roberts et al., 2004).

Turnip (Brassica rapa var. rapa) belongs to Cruciferae and is highly appreciated by the Tibetans and is commonly called “Yuan Gen” and “Niu Ma” (Fernandes et al., 2007). It is widely distributed in the high-altitude Tibet region and is traditionally used as folk medicine and food in China, Tibet, and other places. It is one of the main economic and food crops. The plant is highly adapted to the extreme environments of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and possesses edible, feeding, and pharmaceutical values (Liang et al., 2006). However, Tibetan soil is iron deficient (Zhang et al., 2011), and studying iron transport is helpful for improving turnip output. OPTs are thought to contribute to many biological processes; thus, analyzing the mechanisms and functions of the OPTs response to nutrient deficiency is significant in turnips. To date, no comprehensive study on the OPT family of turnip has been conducted. In this study, we performed a genome-wide identification of OPT family genes in turnip. Detailed analyses, including phylogeny, gene structure, chromosomal location, divergence time, expression profiling, and relative expression level, were performed. Our results provided information for further functional investigations of these genes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Identification of the OPT gene family in turnip

To identify potential members of the OPT gene family in turnip, the coding DNA sequences (CDS) published for Arabidopsis and rice OPT gene sequences (Koh et al., 2002, Vasconcelos et al., 2008) were retrieved and used as queries in BLAST searches against the turnip Genome database (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/brassica/index.html?data=bras_tp%2Fdata&loc=A03%3A22821424..22821483&tracks=DNA%2CTranscripts%2CGenes&highlight=). Each protein domain and functional site was examined with ps_scan.pl (ftp://us.expasy.org/databases/PROSITE/tools/ps_scan). All OPT protein sequences containing the transmembrane transport domains (PF03169) were extracted as candidates. The above candidates were used to search against the GenBank non-redundant (Nr) protein database. WoLF PSORT (http://wolfpsort.org) (Horton et al., 2007) was used to predict protein subcellular localization. The TMHMM server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) was used to estimate the number of transmembrane helical domains. The isoelectric point (pI), molecular weight and grand average hydropathy (GRAVY) values were estimated using the ProtParam tool from ExPASy (Gasteiger et al., 2005) (http://us.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html).

2.2. Phylogenetic analyses of the OPT gene family

Full-length turnip OPTs protein sequences were aligned using the MAFFT 7.0 program, and a phylogenetic reconstruction was performed by MEGA7 software using the neighbor-joining method (Kumar et al., 2016). Bootstrap values were estimated (with 1000 replicates) to assess the relative support for each branch. The diagram of the intron/exon structures of BrrOPT was analyzed using the online Gene Structure Display Server (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) (Hu et al., 2015). Subsequently, the MEME program was used to search for conserved motifs in the turnip BrrOPT protein sequences (Bailey et al., 2006).

2.3. Chromosomal location and gene structure of the OPT genes

The chromosomal distribution of turnip genomic sequences was generated by circos software (http://www.circos.ca/software/download/circos/) (Cheng et al., 2016). According to the position information of the chromosome, segment duplication of the genome was obtained using MCscanX software. Then, the locations of BrrOPT genes were analyzed according to their detailed chromosomal position supplied in the Turnip Genome Database.

2.4. Inference of divergence time

The synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous (Ka) values of the paralogous genes were estimated by the codeml program PAML4 (Yang, 2007). Ks could be used as a proxy for time to estimate the dates of the segmental duplication events. The Ks value was calculated for each of the gene pairs and then used to calculate the approximate date of the duplication event (T = Ks/2λ), divergence rates λ = 1.5 × 10−8 for Brassicaceae (Cao et al., 2011).

2.5. Expression profiles of the turnip OPT genes

The transcriptome data of three developmental stages were obtained and reanalyzed from previous research (Li et al., 2015). The expression levels of BrrOPTs were calculated by fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads values in the early stage before cortex splitting (ES), cortex-splitting stage (CSS), and secondary root-thickening stage (RTS) in turnip. Two independent biological replicates were performed for each developmental stage (Li et al., 2015). Finally, the expression data were gene-wise normalized and hierarchically clustered based on Pearson coefficients with average linkage in the Genesis (version 1.7.6) program (Sturn et al., 2002).

2.6. Plant material and abiotic stress

Turnip seeds were cleaned and surface-sterilized in a solution of 2% sodium hypochlorite for 15 min, rinsed five times in sterilized water, and germinated in plastic trays lined with wet paper towels for 36 h in the dark at 23 °C. The seedlings were grown for 21 days in 1/2 Hoagland's nutrient solution under controlled conditions (28 °C day/25 °C night cycle, 200 mmol photons m−2 s−1 light intensity and 75%–80% relative humidity). Iron-deficiency treatments were performed using previously reported methods (Perea-Garcia et al., 2013). In brief, Fe(II)-EDTA was removed from the Hoagland's solution and 20 μM ferrozine was added. For severe Fe(III) treatment, Fe(II)-EDTA was replaced by Fe(III) (20 μM FeCl3), and the 1/2 MS was supplemented with 300 mM ferrozine. For potassium-, calcium-, and magnesium-deficiency treatments, the KH2PO4, CaCl2, and MgSO4 were removed from the Hoagland's solution, respectively. Plants were harvested during the treatments at 1 h, and seedlings grown into 1/2 Hoagland's solution were used as controls. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80 °C for RNA extraction.

2.7. RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from leaves and roots of turnip using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA quality was identified by a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). A total of 2 μg of total RNA per sample was reverse transcribed using oligo(dT) and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). All of the primers were designed by Primer-BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/index.cgi?LINK_ LOC= BlastHome), applying the following parameters: 150–200 bp of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product size, Nr database, 58 °C–62 °C primer melting temperatures (Tm), and organism (taxid: 3711) for B. rapa. All of the PCR reactions were performed under the following conditions: 40 cycles of 5 s at 94 °C, 15 s at 60 °C, and 34 s at 72 °C. The primers are shown in Table S1. Using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Rox, Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and a 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA), quantitative real-time PCR was conducted in triplicate with different cDNAs synthesized from three biological replicates of different tissues and treatments. For each analysis, a linear standard curve, the threshold cycle number versus log (designated transcript level), was constructed using a series dilution of a specific cDNA standard. The levels of the transcript in all unknown samples were determined according to the standard curve. B. rapa tubulin beta-2 chain-like (LOC103873913) was used as an internal standard, and T test statistical analysis was performed using the software IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Identification of the OPT gene family in turnip

OPTs have been found in fungi, bacteria, and plants (Pike et al., 2009). A number of OPT genes were identified in the genome information of several plants, including 17 in Arabidopsis (Koh et al., 2002), 27 in rice (Vasconcelos et al., 2008), 20 in Populus, and 18 in Vitis (Cao et al., 2011). However, no studies on OPT proteins in turnip have been reported. To obtain all OPTs in turnip, 17 and 27 well-annotated OPT CDS sequences from the Arabidopsis and rice genomes (Koh et al., 2002, Vasconcelos et al., 2008), respectively, were used to search these family members from turnip. We identified 28 OPT genes in the turnip genome, including 15 BrrOPT and 13 BrrYSL (Table 1). The OPT gene family of the turnip was named according to their phylogenies and sequence similarities with the corresponding individual ATOPTs.

Table 1.

Summary information on 28 OPT genes in turnip databases.

| Gene name | Arabidopsis thaliana | Identity (%) | Genomic position | Protein length | PI | GRAVYa | No.of TMHsb | PSORT predictionsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrrOPT1.1 | ATOPT1 | 91.4 | A02:7322765..7325842(−) | 753 | 8.65 | 0.359 | 12 | P: 12, Ch: 1 |

| BrrOPT1.2 | ATOPT1 | 22.9 | A03:5564455..5565195(−) | 192 | 9.37 | 0.401 | 5 | P: 4, V: 4, E.R.: 3, G: 2 |

| BrrOPT2 | ATOPT2 | 91.3 | A09:35159367..35162283(+) | 726 | 8.6 | 0.525 | 14 | P: 8, E.R.: 3, C: 2 |

| BrrOPT3 | ATOPT3 | 93.9 | Scaffold000219:26731..29793(−) | 735 | 8.96 | 0.394 | 14 | P: 12, V: 2 |

| BrrOPT4 | ATOPT4 | 70.2 | A02:26971082..26976620(+) | 729 | 8.98 | 0.432 | 16 | P: 13 |

| BrrOPT5.1 | ATOPT5 | 87.1 | A01:9378553..9381421(−) | 757 | 9.02 | 0.32 | 12 | P: 12, N: 1 |

| BrrOPT5.2 | ATOPT5 | 84.4 | A03:26241224..26235254(−) | 752 | 9.31 | 0.353 | 14 | P: 9, E.R.: 3, C: 2 |

| BrrOPT6 | ATOPT6 | 95 | A01:10053989..10056668(−) | 735 | 8.96 | 0.51 | 14 | P: 10, C: 2, V: 1 |

| BrrOPT7.1 | ATOPT7 | 90.8 | A08:9784927..9790063(+) | 765 | 6.11 | 0.44 | 14 | P: 8, E.R.: 4, C: 1 |

| BrrOPT7.2 | ATOPT7 | 77.2 | A02:17073694..17084509(+) | 778 | 6 | 0.412 | 14 | P: 11, E.R.: 2 |

| BrrOPT8.1 | ATOPT8 | 88 | A02:8148867..8151777(−) | 740 | 8.44 | 0.254 | 13 | P: 8, C: 3, E.R.: 3 |

| BrrOPT8.2 | ATOPT8 | 86.9 | A03:6108425..6111832(−) | 739 | 9.3 | 0.402 | 13 | P: 10, E.R.: 3 |

| BrrOPT8.3 | ATOPT8 | 40 | A03:6045453..6047824(−) | 373 | 9.41 | 0.254 | 5 | Ch: 4, N: 2.5, C: 2, P: 2, E.R.: 2 |

| BrrOPT9.1 | ATOPT9 | 89.5 | A10:5677018..5680222(+) | 730 | 9.01 | 0.254 | 14 | P: 12, E.R.: 2 |

| BrrOPT9.2 | ATOPT9 | 88.3 | A03:6113783..6117130(−) | 745 | 9.13 | 0.254 | 12 | P: 8, C: 3, E.R.: 3 |

| BrrYSL1.1 | ATYSL1 | 92.6 | A01:7632793..7635273(+) | 667 | 8.72 | 0.254 | 14 | P: 9, E.R.: 2, G: 2 |

| BrrYSL1.2 | ATYSL1 | 91.3 | A08:15044595..15047110(+) | 674 | 8.95 | 0.254 | 15 | P: 11, G: 2 |

| BrrYSL1.3 | ATYSL1 | 88 | A03:25407258..25409968(+) | 671 | 9.01 | 0.254 | 14 | P: 11, E.R.: 2 |

| BrrYSL2 | ATYSL2 | 89.5 | A06:16990061..16992816(+) | 666 | 9.04 | 0.254 | 14 | P: 9, G: 3, V: 2 |

| BrrYSL3 | ATYSL3 | 75.6 | A10:5722350..5726588(+) | 805 | 8.56 | 0.254 | 15 | P: 8, V: 2, E.R.: 2, G: 2 |

| BrrYSL4 | ATYSL4 | 15.7 | A04:9062121..9078294(+) | 3589 | 6.58 | 0.254 | 14 | P: 10, N: 2, E.R.: 2 |

| BrrYSL5.1 | ATYSL5 | 92.1 | A03:17733078..17735732(+) | 713 | 8.37 | 0.254 | 14 | P: 6, E.R.: 6, N: 1 |

| BrrYSL5.2 | ATYSL5 | 91.2 | A01:22898080..22900793(−) | 714 | 8.23 | 0.254 | 12 | E.R.: 7, P: 6 |

| BrrYSL5.3 | ATYSL5 | 31.5 | A03:17756401..17757853(+) | 237 | 7.59 | 0.254 | 5 | C: 5, P: 4, Ch: 2, M: 1, V: 1 |

| BrrYSL6 | ATYSL6 | 63.3 | A09:1167050..1172546(+) | 1005 | 8.15 | 0.254 | 12 | P: 5, E.R.: 5, Ch: 1, N: 1, M: 1 |

| BrrYSL7 | ATYSL7 | 88.7 | A07:16911429..16916207(+) | 690 | 9.06 | 0.254 | 14 | P: 8, C: 3, E.R.: 2 |

| BrrYSL8 | ATYSL8 | 90.2 | A08:3215843..3213198(−) | 718 | 7.05 | 0.254 | 14 | P: 9, E.R.: 2, G: 2 |

| BrrYSL9 | Scaffold000141:370026..371230(+) | 342 | 9.2 | 0.254 | 8 | P: 4, V: 4, C: 1, M: 1, E.R.: 1 |

GRAVY means Grand average of hydropathicity.

Number of transmembrane helices predicted with TMHMM Server.

PSORT predictions: P (plasma membrane), V (vacuolar membrane), C (cytosol), Ch (chloroplast), N (nuclear), E.R. (endoplasmic reticulum), M (mitochondrion) and G (Golgi apparatus).

In rice, nine OPT genes in the OPT clade (Vasconcelos et al., 2008) encoded 733 to 766 amino acids, with highly hydrophobic polypeptides (grand average hydrophobicities of 0.35–0.48), and pIs ranging from 6.0 to 9.2. In our study, most OPT genes in turnip encode highly hydrophobic polypeptides (average hydrophobicities of 0.254–0.525) ranging from 666 to 805 amino acids in length except for BrrOPT1.2 and BrrOPT8.3 with 192 and 373 amino acids, sharing a high level of similarity to the OPT clade of the rice. In terms of biochemical properties, most of the OPT proteins were slightly alkaline, and its (pIs) ranged from 6 (BrrOPT7.2) to 9.41 (BrrOPT8.3). The GRAVY and pI values of turnip OPT protein were similar to poplar and grape (Cao et al., 2011), showing that OPT protein is a more conservative and positively charged protein. The polypeptides were also predicted to contain 5–16 transmembrane helices (TMHs). Furthermore, we predicted the probable protein localization for each of the different candidate OPTs in turnip using the protein subcellular localization prediction software WoFL PSORT http://wolfpsort.org. The OPT gene family has a common biological function: transport metal ion, such as AtOPT3 transported iron (Vasconcelos et al., 2008, Wintz et al., 2003) and Fe(III)-chelate (Stacey et al., 2008), with its expression in roots could be induced by the lack of manganese and copper (Wintz et al., 2003), and OsOPT4 transported Fe(II)–NA (Vasconcelos et al., 2008). AtOPT3 localized to the plasma membrane (Zhai et al., 2014). In our study, the result showed that all candidate OPTs in turnip identified are most likely to be localized in the membranes of organelles such as plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, cytosol, or vacuolar membrane (Table 1). These information will help us to explore the function of the OPT gene family in turnip.

3.2. Phylogenetic analyses and gene structural analyses of the OPT genes in turnip

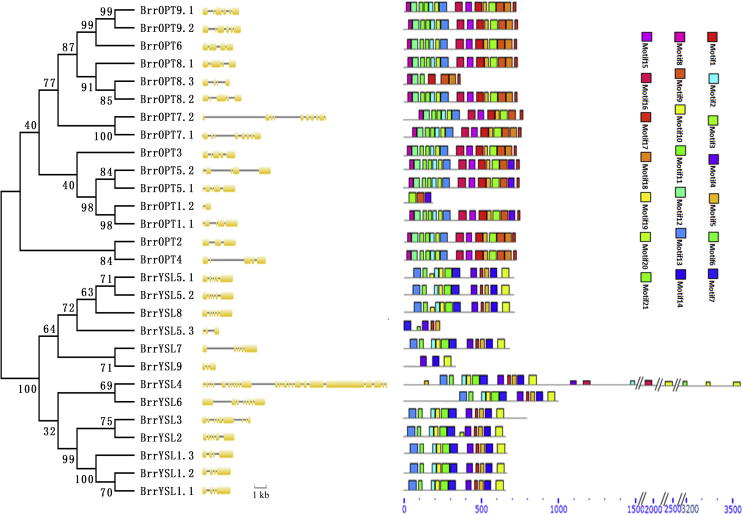

Previous studies showed that phylogenetic relationships among the OPT genes consist of two major clades: the OPT and YSL classes (Lubkowitz, 2011). In our study, the phylogenetic tree divided the BrrOPTs into two classes. Our finding was consistent with previous evolutionary analyses. In addition, by comparing the gene family “intron–exon” number, length, distribution and other genetic structure, we can understand the genetic structure of the diversity and complexity of the reasons for the formation (Shen et al., 2016). We found that in the OPT clade, 11 of 15 BrrOPTs contained 4–6 exons, similar to Arabidopsis, rice, Populus, and Vitis (4–7) (Cao et al., 2011). Furthermore, OPT genes in the same clades have similar coding sequences and a very similar exon–intron structure, strongly supporting their close evolutionary relationship (Fig. 1). The divergent gene structures in the different phylogenetic clades may represent gene family expansion from ancient paralogs or multiple origins of gene ancestry. Differences were found between clades. In the YSL clade, the number of exons was different, from 2 to 28, and these structural differences in the BrrYSL might allow BrrYSL genes to perform different functions. Gene structure diversification is a direct expression of gene family expansion (Koh et al., 2002, Lubkowitz, 2011). The structural diversity of OPT gene family members in turnip provides a mechanism for the evolution of duplicated gene, while exons loss or gain can be an important step in generating structural diversity and complexity (Cheng et al., 2016). In this study, only two exons in BrrOPT1.2 were found (Fig. 1), and the number of BrrOPT1.1 exons was five, which indicated that the loss of BrrOPT1.2 corresponding to exons might result in the functional difference. The number and structure of the exons was different so that the structure and function of genes compared with other sequences are different. BrrOPT7.1, BrrOPT7.2, and BrrYSL4, BrrYSL6 possess more exons; perhaps the exercise of its function is different than OPT family of other genes. The results showed that the numbers of OPT clade and YSL clade genes' exon/intron were special. BrrOPT1.2 and BrrYSL4 possess more exons and more complex structures, whereas BrrOPT1.2 and BrrYSL5.3 have very few exons because of their short gene length. But some of the duplicated genes (BrrOPT9.1/BrrOPT9.2, BrrYSL5.1/BrrYSL5.2, BrrYSL1.1/BrrYSL1.2) had the same number of exons and similar splicing positions, indicating that no significant change was found in the gene structure after repetitive events in the whole genome.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships among turnip 28 OPT proteins. The molecular phylogeny was constructed from a complete protein sequence alignment of OPTs from turnip using the neighbor-joining method with a bootstrapping analysis (1000 replicates). The numbers beside the branches indicate bootstrap values. The exon–intron structures of BrrOPTs were analyzed by the online tool Gene Structure Display Servers 2.0 and were shown in the middle panel. The conserved motifs were detected using the MEME online tool (http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/intro.html) and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) (Right panel).

In addition, distinct 21 motifs within the turnip OPT genes were identified using online MEME tools (Fig. 1). As expected, OPT genes were divided into two clades in phylogenetic analyses. Each class of the most closely related members have common motif compositions, suggesting functional similarities among the OPT proteins within the same class. In the OPT clade, most members of the OPT class possess 15 motifs except the short sequence genes (BrrOPT8.3, BrrOPT1.2).

Although the YSL clade' exon have structural differences, most members of YSL class have 11 common motifs. Five of the motifs (motif 2, motif 5, motif 6, motif 13, and motif 17) are shared by all OPT proteins except the short sequence genes (BrrOPT8.3, BrrOPT1.2, BrrYSL5.3, and BrrYSL9). The motifs suggest functional similarities among the OPT proteins within the same class. Meanwhile, the conserved gene structures revealed unique motifs among clades. Our analyses revealed that the sequence of BrrOPT8.3, BrrOPT1.2, BrrYSL5.3 and BrrYSL9 is shorter than the homologous sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana and a several motifs (motif 1, 2, 5, 11, 16, 17) were observed were lost (Fig. 1). The divergence in motif composition may cause potential functional divergence within different genes. But it whether this leads to loss of function is uncertain and needs further investigation molecular experimental verification.

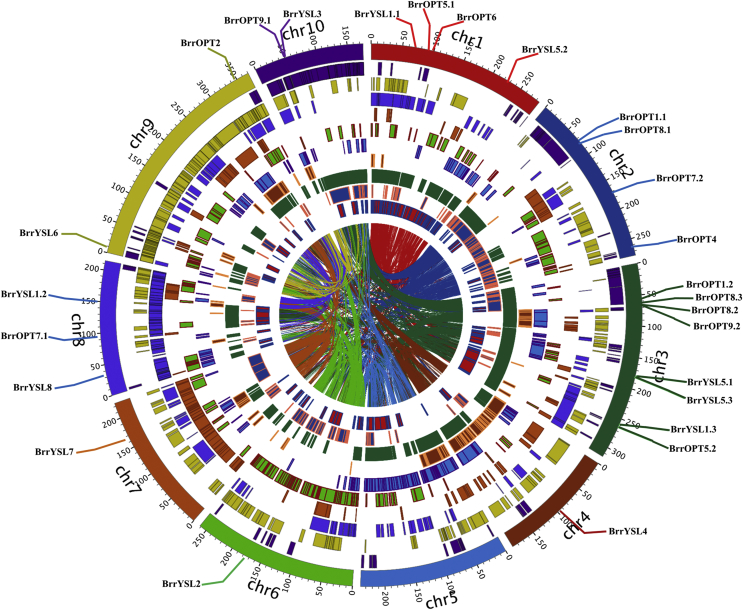

3.3. Chromosomal location of the OPT genes in the genome

To further investigate the relationship between the genetic divergence within the OPT family and gene duplication in turnip genomes, we analyzed the chromosomal location of each OPT gene in turnip. The results show that the OPT genes are distributed unevenly among the nine chromosomes of the turnip genome (Fig. 2). Eight OPT genes were found on chromosome chr3, four OPT genes were identified on each of chromosomes chr1 and chr2, three on chromosome chr8, two on each of chromosomes chr9 and chr10, and only one on each of chromosomes chr4, chr6, and chr7. No OPT gene was found on chr5. Moreover, two of the turnip OPT genes (BrrOPT3, BrrYSL9) are localized to unassembled genomic sequence scaffolds and thus could not be mapped to any particular chromosome. Gene duplication events are thought to have frequently occurred in organismal evolution (Kent et al., 2003, Mehan et al., 2004). Genome-wide duplication events, gene loss, and local rearrangements have created the present complexities of the genome (Shen et al., 2016). In addition, we found that the turnip underwent broad-scale gene duplication events, OPT genes located chromosome duplicate region (Fig. 2). Given the phylogenetic analyses and an entire genome analysis of gene duplications, we observed 10 pairs of segmental duplication (BrrOPT9.1/9.2, BrrOPT7.2/7.1, BrrOPT5.2/5.1, BrrOPT1.2/1.1, BrrYSL5.1/5.2, BrrYSL1.2/1.1, BrrOPT2/4, BrrYSL7/9, BrrYSL4/6, BrrYSL2/3) and one pair of tandem duplication (BrrOPT8.3/8.2). Previous studies have shown that tandem duplications is the major factor that led to the expansion of the OPT gene family. In Arabidopsis, AtOPT8/9 is one pair of tandem duplication (Koh et al., 2002). In rice (Vasconcelos et al., 2008), five pairs of tandem duplication exist, such as OsYSL7/8, OsYSL2/15, OsYSL9/16, OsYSL3/4, OsOPT2/3. Moreover, in Populus and Vitis (Cao et al., 2011), three pairs of tandem duplication (PtYSL1-PtYSL2, PtOPT8-PtOPT5 and VvOPT1-VvOPT2-VvOPT8) were found. However, in our study, these observations suggest that the tandem duplication and transposition events are not the major factors that led to the expansion of the OPT gene family in the turnip. Large-scale segmental duplication events may be the major factor that led to the expansion of the OPT gene family in turnip.

Fig. 2.

Chromosomal locations of the OPT genes in turnip. The chromosomal distribution of turnip genomic sequences was generated by circus software (http://www.circos.ca/software/download/circos/).

3.4. Inference of divergence time between turnip OPT gene

To analyze the divergence time of the duplicated gene, we used a divergence rate of 1.5 × 10−8 mutations per synonymous site per year (Yang et al., 1999), and the synonymous (Ks) and nonsynonymous (Ka) values were estimated for the 11 pairs of paralog genes. After that, we used the Ks of these 11 pairs of repetitive genes to calculate their replication times (T = Ks/2λ). The results showed that the 11 pairs of paralog genes in turnip was approximately between 5.55 and 47.24 million years ago (MYA), an average duplication time of approximately 19.1855 MYA (Table 2). Interestingly, the divergence time of two BrrOPT paralogs (BrrOPT2/4 and BrrYSL2/3) were estimated to have occurred recently. Schranz and Mitchell–Olds (Schranz et al., 2006) estimated the time of very early radiation of Brassicaceae at 34 MYA. At the same time, the Ka/Ks values of these 11 pairs of repeat genes were much smaller than 1, indicating that they were purified in the evolutionary process. By contrast, two pairs of BrrOPT genes, namely, BrrYSL7/9 (ω = 0.4645) and BrrOPT8.3/8.2 (ω = 0.3459), achieved significantly larger ω values than that of other pairs of genes, indicating that they might have a faster evolution rate.

Table 2.

Estimated divergence time between BrrOPT ortholog genes.

| Paralogous pairs | Ks | Ka | Ka/Ks | T (MYA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrrYSL5.1/BrrYSL5.2 | 0.4775 | 0.0207 | 0.0434 | 15.92 |

| BrrYSL7/BrrYSL9 | 0.6385 | 0.2966 | 0.4645 | 21.28 |

| BrrYSL4/BrrYSL6 | 0.5983 | 0.123 | 0.2056 | 19.94 |

| BrrYSL3/BrrYSL2 | 1.2282 | 0.1468 | 0.1195 | 40.94 |

| BrrYSL1.2/BrrYSL1.1 | 0.3454 | 0.0312 | 0.0903 | 11.51 |

| BrrOPT9.1/BrrOPT9.2 | 0.1848 | 0.0445 | 0.2408 | 6.16 |

| BrrOPT8.3/BrrOPT8.2 | 0.1665 | 0.0576 | 0.3459 | 5.55 |

| BrrOPT7.2/BrrOPT7.1 | 0.4177 | 0.1004 | 0.2404 | 13.92 |

| BrrOPT5.2/BrrOPT5.1 | 0.3939 | 0.079 | 0.2006 | 13.13 |

| BrrOPT1.2/BrrOPT1.1 | 0.4636 | 0.0164 | 0.0354 | 15.45 |

| BrrOPT2/BrrOPT4 | 1.4171 | 0.2826 | 0.1994 | 47.24 |

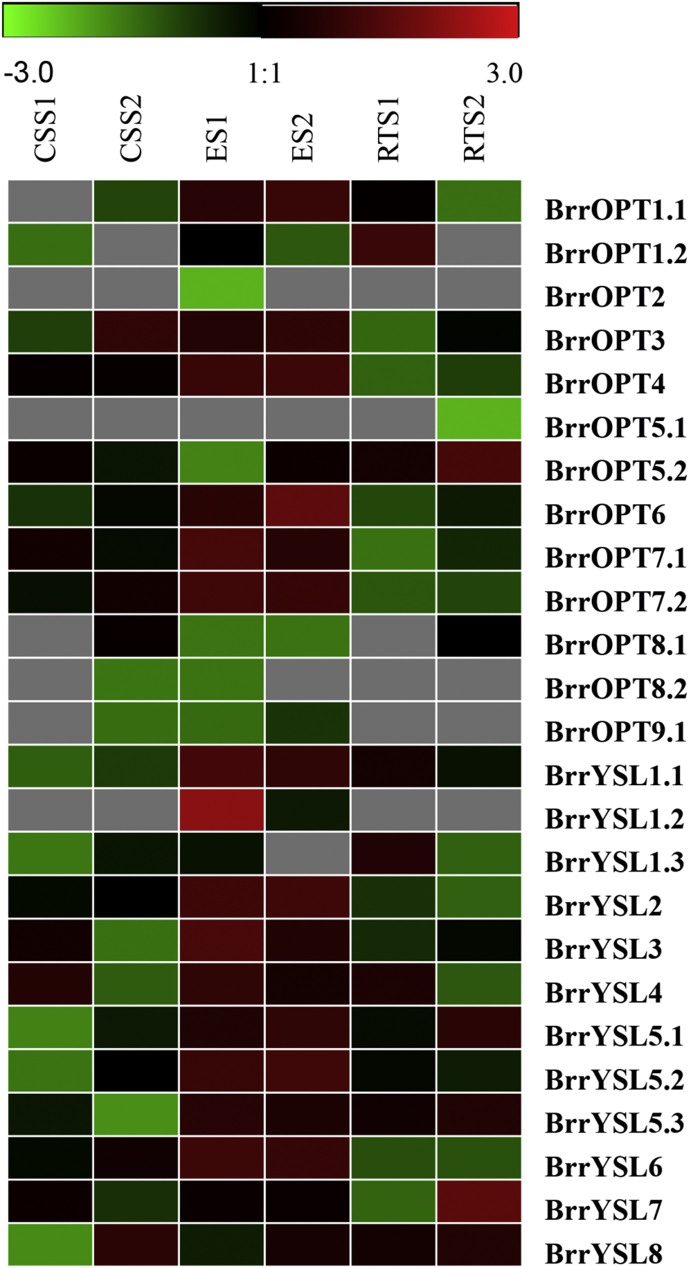

3.5. Expression profiles at different developmental stages of the OPT genes in turnip

The expression profiles can provide useful clues to gene functions (Jackson and Dyer, 2012). Here, we used the expression levels of BrrOPT genes were reanalyzed using publicly available RNA sequence data from three different developmental stages (Li et al., 2015). We selected three seedling stages of the turnip to investigate the different expressions of the OPT genes in the tuberous root development process. These three phases occurred at an early stage before ES, CSS, and secondary RTS. The samples were labeled as ES1, CSS1, RTS1 for the first biological replicate, and ES2, CSS2, RTS2 for the second biological replicate. The expression levels of most OPT genes in turnip peaked at an early stage before ES (Fig. 3), suggesting that most OPT genes are actively involved in cortical division. However, some OPTs do not seem to follow this trend. For example, BrrOPT5.2 and BrrYSL7 showed a particularly high level of expression in the secondary RTS, indicating that BrrOPT5.2 and BrrYSL7 are involved in the secondary RTS, indicating functional differentiation of the OPT gene family and exercising their respective functions. BrrOPT5.1 did not express during ES and CSS periods, suggesting that the gene may not participate in these two developmental activities of the root. Therefore, different OPTs genes may play different important roles during developmental stages in the turnip.

Fig. 3.

Expression profiles at different developmental stages of the OPT genes in turnip. Dynamic expression profiles using the FPKMs of the BrrOPT genes in different developmental stages. FPKM values (log2 ratio) were gene-wise normalized and hierarchically clustered using Genesis software. Genes highly or weakly expressed are colored red and green, respectively, and gray represents the FPKM value of 0. EMB; the early stage before ES, CSS, and secondary RTS.

Duplicated genes may possess different evolutionary fates and functions, which can be indicated by divergence in their expression patterns (Prince and Pickett, 2002). They might govern the expansion of the OPT gene family; thus, we investigated the expression profiles of the duplicated OPT gene pairs identified above in the turnip. Our results show that six of the 11 gene pairs (BrrYSL4/6, 3/2, 1.1/1.2, BrrOPT5.1/5.2, 1.1/1.2, 2/4) share different expression trends (Fig. 3). As one of paralogs gene pairs, BrrOPT1.1 was specifically expressed in the ES and its paralog BrrOPT1.2 was expressed abundantly in the RTS. BrrOPT5.1 was expressed abundantly in the RTS stages, but BrrOPT5.2 was not expressed in the RTS. The results reveal that the BrrOPT paralogs exhibit distinct expression patterns under different developmental stages, indicating that substantial neofunctionalization may have occurred during the subsequent evolution of the duplicated genes. Similar studies were also found showing that paralogs gene pair PtOTP5/8 in poplar and VvOPT1/2/8 in grapes displayed different expression levels at different developmental stages (Cao et al., 2011). Thus, the expression patterns of OPT genes at different developmental stages may indicate the functional divergence between paralogs in turnip.

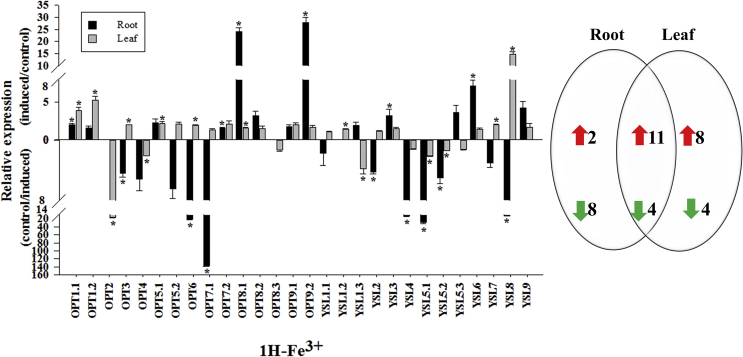

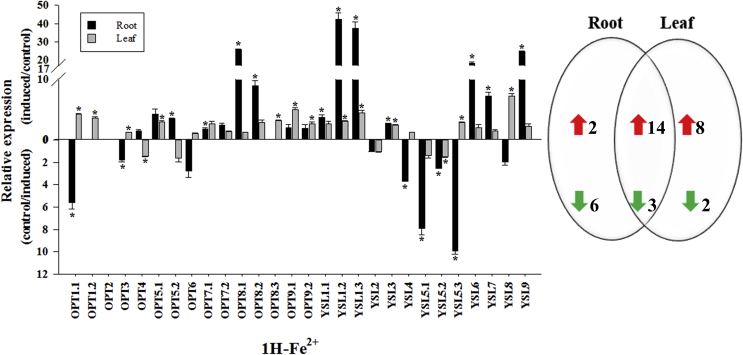

3.6. Gene relative expression analysis of OPT family with iron transportation

Plants not only need to absorb enough iron from the environment, but also the efficient operation of iron in the body and the rational distribution to organs to ensure the completion of its life cycle and improve the yield and quality (Hell and Stephan, 2003). OPT gene family plays an important role for Strategy II mechanism plants that use OPTs of the YSL clade for the long-distance transport of metals and iron-phytosiderophore chelates (Lubkowitz, 2006). In our study, after the Fe(II) was replaced by Fe(III) in the hydroponic culture solution for 1 h, the 11 genes' relative expression level of turnip in both roots and leaves significantly increased. In the OPT clade, BrrOPT8.1 and BrrOPT9.2 detected a higher level of transcription (approximately 20-fold or more) in roots, indicating that the two genes were affected by Fe(III), most likely related to the transport of Fe(III) in the roots and is the downstream protein of forward transport (Fig. 4). In previous studies, OsOPT7 (Zheng et al., 2009), AtOPT3 (Wintz et al., 2003, Stacey et al., 2006, Buckhout et al., 2009), and AtOPT2 (Wintz et al., 2003), these studies revealed the important role of the OPT clade in the long-distance transport of iron. Furthermore, in the YSL clade, BrrYSL8 was significantly increased in leaves, indicating that the gene was affected by Fe(III) and may be involved in the chelation of Fe(III) in the leaves. Also, AtYSL1 and OsYSL18 in the OPT gene family possess the function of transporting Fe(III)-chelates (Lubkowitz, 2011, Roberts et al., 2004, Aoyama et al., 2009). Moreover, after 1 h of Fe(II)-deficiency treatment, the relative expression of OPT family gene of 28 turnips in 16 roots was significantly up-regulated (Fig. 5), which was the maximum number of up-regulated genes, suggesting that many BrrOPT genes were involved in responding to Fe(II) deficient. After 1 h of Fe(II)-deficiency treatment, BrrOPT8.1, BrrYSL1.2, BrrYSL1.3, BrrYSL6 and BrrYSL9 transcript levels were detected to be greater (approximately 10-fold and above), indicating that they may play a very important role in transporting Fe(II). The importance of OPT gene family for iron transport is further demonstrated.

Fig. 4.

Gene relative expression analysis of OPT family with the Fe(II) was replaced by Fe(III). qPCR analyses were performed, and expression values were calculated using the 2−△△CT method. Data are mean values ± SE obtained from three replicates. Different letters within a column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05; Tukey's test).

Fig. 5.

Gene relative expression analysis of OPT family with Fe(II) deficient. Data are mean values ± SE obtained from three replicates. Different letters within a column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05; Tukey's test).

Also, we analyzed the expression of paralogs genes in the Fe(II)-deficiency treatment, five pairs (BrrOPT5.1/5.2, BrrOPT7.1/7.2, BrrOPT9.1/9.2, BrrYSL1.1/1.2 and BrrYSL5.1/5.2) were expressed consistently with each other, both up-regulated or down-regulated. However, in the Fe(II)-deficiency treatment, the paralog gene pairs have different expression trends. Two paralog gene pairs (such as BrrOPT7.1/7.2 and BrrYSL4/6) demonstrated divergent expression patterns in root, that is, one gene is induced, whereas the other is suppressed by the treatment. The results further reveal that the BrrOPT paralogs exhibit distinct expression patterns under different stress conditions and suggest the functional divergence of the duplicated genes of BrrOPTs.

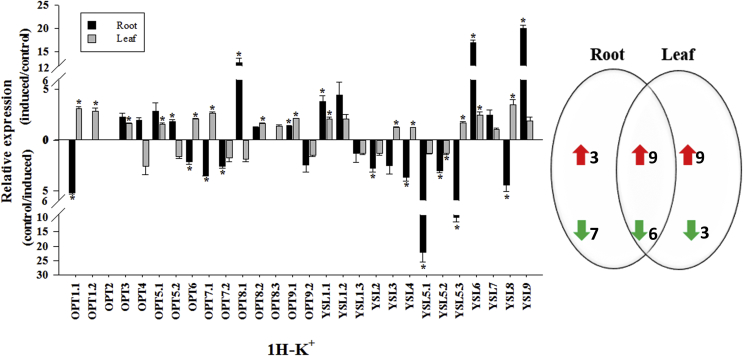

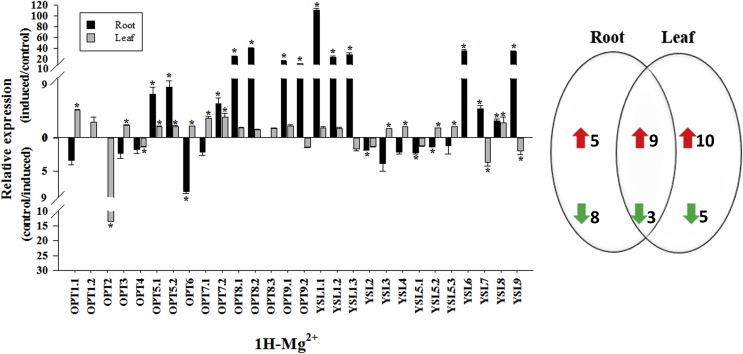

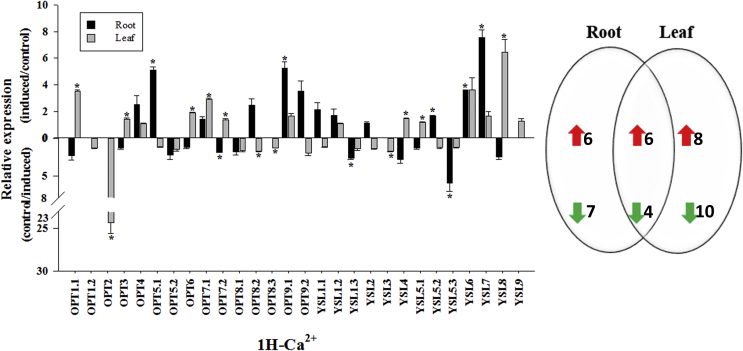

3.7. Gene relative expression analysis of OPT family with the potassium, magnesium, and calcium-deficiency treatments

During the growth and development of plants, all kinds of nutrient elements have corresponding physiological functions. When the plant lacks some elements, the morphological structure and physiological function of the plant reacts accordingly, which will cause blocked plant growth and development and development and decrease production (Gruber et al., 2013). In turnip, no report on the transport of potassium, magnesium, and calcium ions were found on the OPT gene family. Potassium plays an important role in many physiological and biochemical processes in plant growth and development, such as promoting photosynthesis and assimilation products transportation and enhancing plant stress resistance (Doyle et al., 1998, Hirsch et al., 1998). In our study, after 1 h of treatment with potassium deficiency, the relative expression of OPT family gene of 28 turnip in 12 roots was significantly up-regulated (Fig. 6). After potassium deficiency, BrrOPT8.1, BrrYSL5.3, and BrrYSL9 expression was induced 10-fold in roots, suggesting that these three genes are active in the absence potassium, which were probably related to transport potassium in roots. In leaves, the relative expression of 18 genes was significantly increased, indicating that these genes were affected by the potassium deficiency and may be involved in transport effect. Magnesium is the most abundant divalent cation in higher plant cells and plays an important role in plant growth and development. The chemical properties of magnesium are unique in the metal ions required for plant growth and development (Maguire, 2006). In our study, the relative expression of 14 genes increased in the root, and most of the up-regulated genes are extremely significant (Fig. 7). BrrOPT8.1, BrrOPT8.2, BrrOPT9.1, BrrOPT9.2, BrrYSL1.1, BrrYSL1.2, BrrYSL6, BrrYSL9 were positively correlated with magnesium transport. The relative expression of 19 genes in the leaves increased, but the level of up-regulation was low, indicating that magnesium deficiency was not sensitive in leaves. Calcium signal is an important regulator of plant growth and development (Hepler, 2005). When the plant is stimulated by the external environment, the calcium ion concentration in the cells will specifically change, causing a series of protective physiological responses (Yang and Poovaiah, 2003). After 1 h of calcium deficiency treatment (Fig. 8), the relative expression of BrrYSL7 of turnip in roots was significantly up-regulated, indicating that BrrYSL7 may play an important role in the transport of calcium. The nutrient elements deficiency led to the significantly regulated relative expression, indicating that OPT gene family was indispensable for potassium, magnesium, and calcium transportation.

Fig. 6.

Gene relative expression analysis of OPT family with potassium deficient. Data are mean values ± SE obtained from three replicates. Different letters within a column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05; Tukey's test).

Fig. 7.

Gene relative expression analysis of OPT family with magnesium deficient. Data are mean values ± SE obtained from three replicates. Different letters within a column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05; Tukey's test).

Fig. 8.

Gene relative expression analysis of OPT family with calcium deficient. Data are mean values ± SE obtained from three replicates. Different letters within a column indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05; Tukey's test).

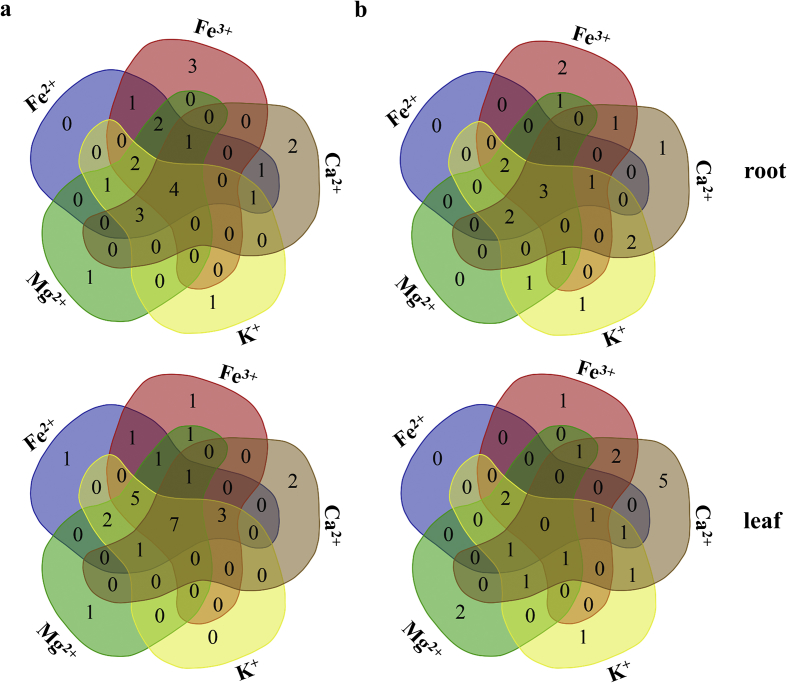

3.8. Turnip OPTs coordinated cross-talking of multiple stress responses

Plants directly assimilated minerals from the environment and thus are key for the acquisition of metals by all subsequent consumers. Plants utilize poorly understood mechanisms involving a large number of membrane transporters and metal binding proteins with overlapping substrate specificities and complex regulation (Wintz et al., 2003). OPTs genes are usually expressed by metal deficiency. To better understand the function and the integrated regulation, we analyzed the relative expression level in roots and leaves of 28 OPT turnip genes coding for unknown or potential metal transporters. In our study, OPTs were expressed differently in each treatment, BrrOPT5.1, OPT8.2, OPT9.1 and YSL6 were up-regulated in all of the five treatments in roots (Fig. 9), indicating that cross-talking may help turnip to regulate the stress expression under various types and suggesting that the functions of BrrOPT5.1, OPT8.2, OPT9.1, and YSL6 were extensive. Moreover, the relative expression levels of seven OPT genes are up-regulated together in the leaves (Fig. 9), OPT1.1, OPT3, OPT6, OPT7.1, OPT9.1, YSL1.2, and YSL8, indicating that they may participate in different ion transport. The specific transport roles of the above genes in abiotic stress need further study.

Fig. 9.

Localization of BrrOPTs cross-talk among different iron deficiencies. Venn diagram showing the overlap of BrrOPT genes up-regulation (a) and down-regulation (b) expression in response to the Fe(II) was replaced by Fe(III), Fe(II), potassium, magnesium, and calcium deficient treatments of root and leaf.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we identified 28 OPT genes in the turnip genome. Significant site-specific altered constraints and a higher evolutionary rate may have contributed to the functional divergence of BrrOPTs genes. Different expression levels of BrrOPTs genes under a variety of deficiency treatments also indicated that the turnip OPT gene family has functionally diverged during long-term evolution. Our analyses provide an important foundation for understanding the potential roles of BrrOPTs in regulating turnip responses to deficiency treatment. Further research on turnip OPTs' metal transport functions are needed to determine their effects on plant adaptations to adverse conditions and underlying mechanisms.

Author contributions

Designed the experiments: YPY YQY. Performed the experiments: YNP DNY XY QLW QC. Analyzed the data: YQY YNP. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: XY QLW QC. Wrote the paper: YNP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported financially by the Major Projects of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31590823) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31601999).

(Editor: Xuewen Wang)

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Editorial Office of Plant Diversity.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2018.03.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Aoyama T., Kobayashi T., Takahashi M., Nagasaka S., Usuda K., Kakei Y., Ishimaru Y., Nakanishi H., Mori S., Nishizawa N.K. OsYSL18 is a rice iron(III)–deoxymugineic acid transporter specifically expressed in reproductive organs and phloem of lamina joints. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;70:681–692. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9500-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T.L., Williams N., Misleh C., Li W.W. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W369–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckhout T.J., Yang T.J., Schmidt W. Early iron-deficiency-induced transcriptional changes in Arabidopsis roots as revealed by microarray analyses. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnac O., Bourbouloux A., Chakrabarty D., Zhang M.Y., Delrot S. AtOPT6 transports glutathione derivatives and is induced by primisulfuron. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1378–1387. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Huang J., Yang Y., Hu X. Analyses of the oligopeptide transporter gene family in poplar and grape. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:465. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F., Sun R., Hou X., Zheng H., Zhang F., Zhang Y., Liu B., Liang J., Zhuang M., Liu Y., Liu D., Wang X., Li P., Liu Y., Lin K., Bucher J., Zhang N., Wang Y., Wang H., Deng J., Liao Y., Wei K., Zhang X., Fu L., Hu Y., Liu J., Cai C., Zhang S., Zhang S., Li F., Zhang H., Zhang J., Guo N., Liu Z., Liu J., Sun C., Ma Y., Zhang H., Cui Y., Freeling M.R., Borm T., Bonnema G., Wu J., Wang X. Subgenome parallel selection is associated with morphotype diversification and convergent crop domestication in Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1218–1224. doi: 10.1038/ng.3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curie C., Panaviene Z., Loulergue C., Dellaporta S.L., Briat J.F., Walker E.L. Maize yellow stripe1 encodes a membrane protein directly involved in Fe(III) uptake. Nature. 2001;409:346–349. doi: 10.1038/35053080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato R.J., Jr., Roberts L.A., Sanderson T., Eisley R.B., Walker E.L. Arabidopsis Yellow Stripe-Like2 (YSL2): a metal-regulated gene encoding a plasma membrane transporter of nicotianamine-metal complexes. Plant J. 2004;39:403–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle D.A., Morais Cabral J., Pfuetzner R.A., Kuo A., Gulbis J.M., Cohen S.L., Chait B.T., MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes F., Valentao P., Sousa C., Pereira J., Seabra R., Andrade P. Chemical and antioxidative assessment of dietary turnip (Brassica rapa var. rapa L.) Food Chem. 2007;105:1003–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S.E., Wilkins M.R., Appel R.D., Bairoch A. Springer; 2005. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomolplitinant K.M., Saier M.H., Jr. Evolution of the oligopeptide transporter family. J. Membr. Biol. 2011;240:89–110. doi: 10.1007/s00232-011-9347-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber B.D., Giehl R.F., Friedel S., von Wiren N. Plasticity of the Arabidopsis root system under nutrient deficiencies. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:161–179. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.218453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell R., Stephan U.W. Iron uptake, trafficking and homeostasis in plants. Planta. 2003;216:541–551. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0920-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler P.K. Calcium: a central regulator of plant growth and development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2142–2155. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch R.E., Lewis B.D., Spalding E.P., Sussman M.R. A role for the AKT1 potassium channel in plant nutrition. Science. 1998;280:918–921. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P., Park K.J., Obayashi T., Fujita N., Harada H., Adams-Collier C.J., Nakai K. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W585–W587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Jin J., Guo A.Y., Zhang H., Luo J., Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Masuda H., Bashir K., Inoue H., Tsukamoto T., Takahashi M., Nakanishi H., Aoki N., Hirose T., Ohsugi R., Nishizawa N.K. Rice metal-nicotianamine transporter, OsYSL2, is required for the long-distance transport of iron and manganese. Plant J. 2010;62:379–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L.A., Dyer D.W. Protocol for gene expression profiling using DNA microarrays in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;903:343–357. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-937-2_24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W.J., Baertsch R., Hinrichs A., Miller W., Haussler D. Evolution's cauldron: duplication, deletion, and rearrangement in the mouse and human genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:11484–11489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932072100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh S., Wiles A.M., Sharp J.S., Naider F.R., Becker J.M., Stacey G. An oligopeptide transporter gene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:21–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike S., Inoue H., Mizuno D., Takahashi M., Nakanishi H., Mori S., Nishizawa N.K. OsYSL2 is a rice metal-nicotianamine transporter that is regulated by iron and expressed in the phloem. Plant J. 2004;39:415–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Chiecko J.C., Kim S.A., Walker E.L., Lee Y., Guerinot M.L., An G. Disruption of OsYSL15 leads to iron inefficiency in rice plants. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:786–800. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.135418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ding Q., Wang F., Zhang Y., Li H., Gao J. Integrative analysis of mRNA and miRNA expression profiles of the tuberous root development at seedling stages in turnips. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y.S., Kim H.K., Lefeber A.W., Erkelens C., Choi Y.H., Verpoorte R. Identification of phenylpropanoids in methyl jasmonate treated Brassica rapa leaves using two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1112:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.11.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubkowitz M. The OPT family functions in long-distance peptide and metal transport in plants. Genet. Eng. (N. Y.) 2006;27:35–55. doi: 10.1007/0-387-25856-6_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubkowitz M. The oligopeptide transporters: a small gene family with a diverse group of substrates and functions? Mol. Plant. 2011;4:407–415. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire M.E. Magnesium transporters: properties, regulation and structure. Front. Biosci. 2006;11:3149–3163. doi: 10.2741/2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehan M.R., Freimer N.B., Ophoff R.A. A genome-wide survey of segmental duplications that mediate common human genetic variation of chromosomal architecture. Hum Genomics. 2004;1:335–344. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-1-5-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y., Ma J.F., Yamaji N., Ueno D., Nomoto K., Iwashita T. A specific transporter for iron(III)-phytosiderophore in barley roots. Plant J. 2006;46:563–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa H., Stacey G., Gassmann W. ScOPT1 and AtOPT4 function as proton-coupled oligopeptide transporters with broad but distinct substrate specificities. Biochem. J. 2006;393:267–275. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea-Garcia A., Garcia-Molina A., Andres-Colas N., Vera-Sirera F., Perez-Amador M.A., Puig S., Penarrubia L. Arabidopsis copper transport protein COPT2 participates in the cross talk between iron deficiency responses and low-phosphate signaling. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:180–194. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.212407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike S., Patel A., Stacey G., Gassmann W. Arabidopsis OPT6 is an oligopeptide transporter with exceptionally broad substrate specificity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1923–1932. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince V.E., Pickett F.B. Splitting pairs: the diverging fates of duplicated genes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrg928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts L.A., Pierson A.J., Panaviene Z., Walker E.L. Yellow stripe1. Expanded roles for the maize iron-phytosiderophore transporter. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:112–120. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.037572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schranz M.E., Lysak M.A., Mitchell-Olds T. The ABC's of comparative genomics in the Brassicaceae: building blocks of crucifer genomes. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Liu M., Wang L., Li Z., Taylor D.C., Li Z., Zhang M. Identification, duplication, evolution and expression analyses of caleosins in Brassica plants and Arabidopsis subspecies. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2016;291:971–988. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey M.G., Osawa H., Patel A., Gassmann W., Stacey G. Expression analyses of Arabidopsis oligopeptide transporters during seed germination, vegetative growth and reproduction. Planta. 2006;223:291–305. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey M.G., Patel A., McClain W.E., Mathieu M., Remley M., Rogers E.E., Gassmann W., Blevins D.G., Stacey G. The Arabidopsis AtOPT3 protein functions in metal homeostasis and movement of iron to developing seeds. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:589–601. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.108183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturn A., Quackenbush J., Trajanoski Z. Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:207–208. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos M.W., Li G.W., Lubkowitz M.A., Grusak M.A. Characterization of the PT clade of oligopeptide transporters in rice. Plant Genome J. 2008;1:77. [Google Scholar]

- Wintz H., Fox T., Wu Y.Y., Feng V., Chen W., Chang H.S., Zhu T., Vulpe C. Expression profiles of Arabidopsis thaliana in mineral deficiencies reveal novel transporters involved in metal homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:47644–47653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309338200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T., Poovaiah B.W. Calcium/calmodulin-mediated signal network in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.-W., Lai K.-N., Tai P.-Y., Li W.-H. Rates of nucleotide substitution in angiosperm mitochondrial DNA sequences and dates of divergence between Brassica and other angiosperm lineages. J. Mol. Evol. 1999;48:597–604. doi: 10.1007/pl00006502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Z., Gayomba S.R., Jung H.I., Vimalakumari N.K., Pineros M., Craft E., Rutzke M.A., Danku J., Lahner B., Punshon T., Guerinot M.L., Salt D.E., Kochian L.V., Vatamaniuk O.K. OPT3 is a phloem-specific iron transporter that is essential for systemic iron signaling and redistribution of iron and cadmium in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2014;26:2249–2264. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.123737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Yang L., Wang W., Li Y., Li H. Environmental selenium in the Kaschin-Beck disease area, Tibetan Plateau, China. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2011;33:495–501. doi: 10.1007/s10653-010-9366-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.Y., Bourbouloux A., Cagnac O., Srikanth C.V., Rentsch D., Bachhawat A.K., Delrot S. A novel family of transporters mediating the transport of glutathione derivatives in plants. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:482–491. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.030940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Huang F., Narsai R., Wu J., Giraud E., He F., Cheng L., Wang F., Wu P., Whelan J., Shou H. Physiological and transcriptome analysis of iron and phosphorus interaction in rice seedlings. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:262–274. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.141051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.