Abstract

Objectives:

In this study, we investigated the co-administration of ondansetron with morphine, and whether it could prevent the development of physical dependence in patients taking opioids for the treatment of chronic pain.

Methods:

A total of 48 chronic back pain patients (N=48) participated in this double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Patients were titrated onto sustained-release oral morphine and randomized to take 8mg ondansetron or placebo three times daily concurrently with morphine during the 30-day titration. Following titration, patients underwent Naloxone induced opioid withdrawal. Opioid withdrawal signs and symptoms were then assessed by a blinded research assistant (objective opioid withdrawal score: OOWS) and by the research participant (subjective opioid withdrawal score: SOWS).

Results:

We observed clinically significant signs of naloxone-precipitated opioid withdrawal in all participants (ΔOOWS = 4.3 ± 2.4, p < 0.0001; ΔSOWS = 14.1 ± 11.7, p < 0.0001), however no significant differences in withdrawal scores were detected between treatment groups.

Conclusion:

We hypothesized that ondansetron would prevent the development of physical dependence in human subjects when co-administered with opioids, but found no difference in naloxone-precipitated opioid withdrawal scores between ondansetron and placebo treatment groups. These results suggest that further studies are needed to determine if 5HT3 receptor antagonists are useful in preventing opioid physical dependence.

Keywords: Ondansetron, 5HT3 antagonist, Opioid Withdrawal, Physical Dependence, Morphine, Naloxone, Opioids

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Opioid therapy is pervasive for the treatment of pain in the United States; 27.5 million Americans received a prescription for an opioid analgesic in 2010, an approximately 80% increase from 15.3 million in 2000 (Sites et al., 2014). Additionally, there has been a consistent increase in the number of adults receiving five or more opioid prescriptions per year (Sites et al., 2014). Such a rapidly rising incidence of opioid use increases the urgency of finding better ways of addressing the problems associated with narcotic opioid analgesics. Problems include misuse and overdose (CDC Grand Rounds, 2012; Manchikanti et al., 2012), decreased efficacy of the drugs due to hyperalgesia or analgesic tolerance (Chu et al., 2006) and the potential for physical dependency and addiction (Hser et al., 2015).

Physical dependency to opioids significantly contributes to the addictive potential of these medications (Chu et al., 2009). If opioid use is suddenly reduced or ceased, withdrawal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, insomnia, fever and other flu-like symptoms can arise. Opioid users often continue taking opioids to avoid withdrawal symptoms (O’Brien et al., 1998), signifying opioid withdrawal as a negative reinforcing factor for opioid misuse. Clonidine, methadone, and buprenorphine are current methods used to address opiate withdrawal after dependency has developed. These methods can be problematic due to limited efficacy, serious side effects, potential for misuse and difficulty in obtaining access to treatment (Boothby and Doering, 2007; Peterson et al., 2010; Washton and Resnick, 1981). Preventing the development of physical dependence rather than addressing opioid withdrawal after physical dependence has been established would be an entirely novel approach to facilitating the cessation of opioids and preventing opioid misuse.

Recent preliminary studies have identified a potential target for this novel approach. We previously used computation haplotype-based genetic mapping in a mouse model to show that the 5HT3 receptor is linked to physical dependency and withdrawal (Chu et al., 2009). 5HT3 receptor antagonists (5HT3-RAs) have several advantages over existing pharmaceutical treatments for opioid withdrawal: they are non-opioid, non-addicting, safe to administer outside of an inpatient clinical setting and low in side effects. Co-administration of ondansetron with morphine significantly reduced physical dependence as measured by naloxone-induced withdrawal behavior in mice when compared with the placebo group. We also showed that pre-treatment with 5HT3 receptor antagonists prior to morphine exposure significantly reduced objective measures of opioid withdrawal in healthy human volunteers in an acute opioid withdrawal model (Chu et al., 2009). In our present study, we investigated whether co-administration of ondansetron along with morphine could prevent the development of physical dependence in patients chronically taking opioids for the treatment of chronic pain.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

We used advertisements and referrals from ResearchMatch and the Stanford Pain Clinic to recruit patients for our study. Possible participants were excluded if they demonstrated (a) history of cardiac disease; (b) history of peripheral neuropathic pain, scleroderma, or other condition that would preclude cold water forearm immersion; (c) history of addiction or chronic pain conditions other than low back pain; (d) history of cardiac arrhythmia; (e) history of hepatic disease; (f) use of steroid or nerve-stimulating medications; (g) any condition precluding opioid use; or (h) pregnancy. Overall inclusion criteria included: (a) diagnosis of low back pain; (b) 18–50 years of age; (c) eligibility to escalate opioid therapy dose, as determined by the treating physician and study PI; and (d) low risk for addiction as determined by the PI, an individual with expertise in opioid addiction aided by use of the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) (Webster and Webster, 2005) at the patient intake exam. The participant sample included patients with and without existing opioid use. Following the first session, patients were titrated off their current opioid regimen if applicable and onto sustained-release oral morphine.

The Institutional Review Board (Stanford University) authorized the human experimental protocol on April 15, 2009 and the study was part of a larger study that was registered in the clinicaltrials.gov database (identifier NCT01549652). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

2.2. Randomization

All study sessions and data collection were conducted by a blinded research assistant (TR, EC, HO, HV) and supervised by an unblinded physician (LC) and study nurse (RO) who administered the study medication and monitored participants throughout the study. Participants were recruited by TR, EC, HO and HV and informed that they would be randomized into one of two treatment groups, either placebo or 8mg Ondansetron and were told that neither they nor the researchers knew which treatment group they would be in. Participants were told that their treatment capsules may or may not reduce the side effects of morphine such as tolerance, nausea and withdrawal symptoms. Participants were blinded and randomized at a 1:1 ratio using block randomization without stratification by LC and RO using the website http://www.randomization.com (Dallal, 2013). One block was used and split into three parts; the first block contained 46 participants, the second block 15 and the third block 15. Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes utilizing top and bottom carbon paper wrapped in aluminum foil were prepared by both RO and staff members outside of the study, and stored in a safe along with the randomization schedule. Placebo and Ondansetron were placed inside identical, grey, opaque capsules and packed into bottles by an offsite compounding pharmacy in Los Altos, California, who had access to the randomization list. Placebo in powder form was used, and ondansetron pills were placed inside the grey, opaque capsules surrounded by placebo powder.

2.3. Study Protocol

In this double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized study we used a previously described protocol for opioid-induced withdrawal (Compton et al., 2003; Compton et al., 2004). Each participant in this study attended two separate laboratory sessions, one of which included acute opioid withdrawal. During the first session, we obtained baseline data for study measures including Objective Opioid Withdrawal Score (OOWS), Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Score (SOWS), Profile of Mood States (POMS) and vital signs. Following this session, patients were titrated onto sustained-release oral morphine (Purdue Pharma, Stamford, CT, 2007) following a 40 day schedule of 10 days taper on, 20 days maintenance, and 10 days taper off. Patients were also randomized to take 8 mg of ondansetron (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, 2004) or placebo three times daily during the titration period.

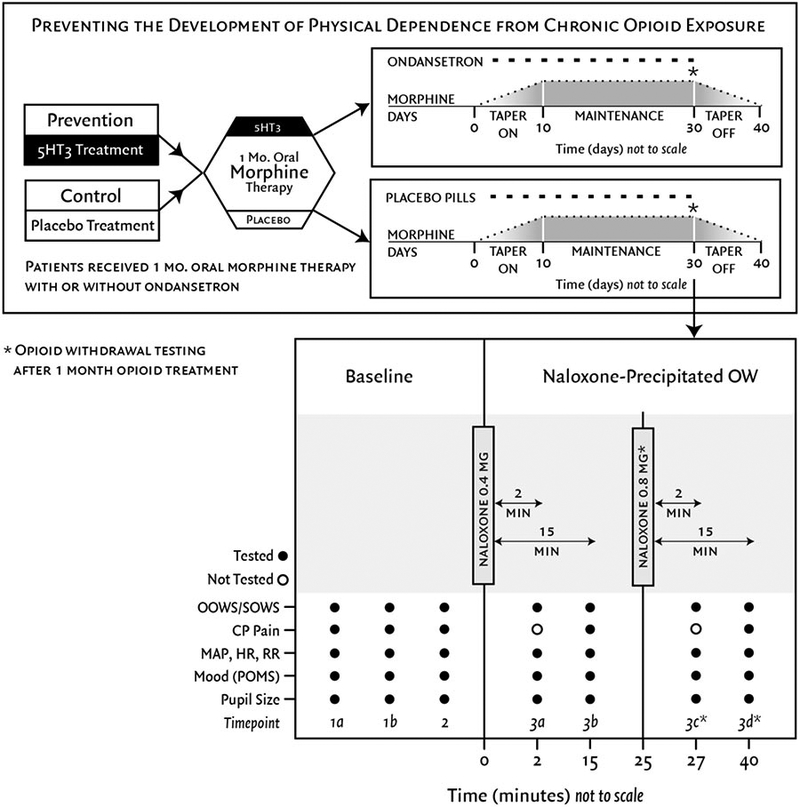

At the second study session, 30 days after the first session, participants received IV naloxone (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL, 2004) (0.4 mg/70 kg) to precipitate opioid withdrawal. The overall study timeline is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Study design.

Preventing the development of physical dependence from chronic opioid exposure. This randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study enrolled patients with chronic low back pain. Patients received one month of oral morphine therapy with or without concurrent ondansetron. After 30 days, patients underwent acute naloxone-precipitated withdrawal.

*A second naloxone dose (0.8mg/70kg) and subsequent measures at timepoints 3c and 3d only occurred for participants who had an OOWS score < 6 after the first withdrawal and consented to more naloxone.

OOWS=objective opioid withdrawal scale, SOWS=subjective opioid withdrawal scale, CP pain=cold pressor tolerance/threshold, MAP=mean arterial pressure, HR=heart rate, RR=respiratory rate, POMS=profile of mood states

2.4. Study Session Timeline

2.4.1. Session One.

Participants’ baseline measurements for OOWS, SOWS, and pain surveys were taken. After the session, participants received their first dose of morphine.

2.4.2. Titration.

Figure 2 illustrates the titration schedule for the ondansetron and placebo groups. Participants began with 30 mg/day and increased by 15 mg every two days or as dictated by side effects until (1) adequate analgesia was achieved; (2) side effects inhibited further titration or; (3) the maximum dose of 120 mg/day was reached. Research personnel contacted patients daily until a stable dose was achieved and all side effects were controlled. If participants experienced persistent nausea or constipation, their dose of opioid medication was reduced and they were given metoclopramide (Schwarz Pharma Mfg., Inc., Seymour, IN, 2004) for nausea or docusate sodium 100 mg soft gel capsules (Apothecon Pharmaceuticals Pvt. Ltd., Vadodara, Gujarat, India, 1993) for constipation and were instructed to increase water intake.

After the second study session was completed, participants were told to take their next dose of morphine as scheduled to avoid any further withdrawal symptoms. The taper off titration was closely monitored by a registered nurse and the PI and followed a course of reducing morphine medication by 15mg/day every two days or slower if necessary. Participants were told to speak to their primary physician if they wanted to continue morphine for pain relief or to try another medication. A letter describing their dose of morphine and tolerance was sent to their physician upon request. Participants were followed until no side effects of titration were noted.

2.4.3. Session Two.

Participants returned to Stanford University after 30 days and underwent naloxone-precipitated opioid withdrawal. Withdrawal was induced by an intravenous (IV) injection of 0.4 mg/70 kg of naloxone, per procedures to induce temporary opioid withdrawal after induction of acute opioid physical dependence (APD) described by Compton et al. (2003, 2004). If we did not observe significant withdrawal (OOWS < 6) and the participant consented, another larger dose of IV naloxone (0.8 mg/70 kg) was administered. Naloxone dosing was calculated with Robinson’s ideal bodyweight for participants with BMI > 40 (Robinson et al., 1983).

2.4.4. Data Collection.

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools hosted at Stanford University (Harris et al., 2009).

2.4.5. Objective and Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scales (OOWS and SOWS).

Previously validated ratings, OOWS and SOWS, were used to assess withdrawal symptoms (Handelsman et al., 1987). OOWS consists of 13 observable physical signs that are surveyed over a five-minute observation period and scored as present (score of 1) or absent (score of 0). OOWS measurements were assessed by the same, blinded research assistant during each study session.

The SOWS scale consists of 16 physical and emotional symptoms that are rated by the participant on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) to indicate the degree to which the participant is feeling that emotion or physical symptom. The total OOWS and SOWS scores are calculated by summing all scores for the signs or symptoms (OOWS 13; SOWS 16).

OOWS and SOWS were assessed five or seven times during the second study session: twice before pretreatment, 15 minutes after pretreatment, and 2 and 15 minutes after one or two naloxone administrations (Figure 2).

2.4.6. Other Surveys.

In addition to OOWS and SOWS, POMS (McNair et al., 1971) was also used as a secondary measure. POMS is a 65-question survey used to assess tension/anxiety, depression, anger, fatigue, vigor, confusion, and overall mood disturbance. POMS was administered twice during the first study session and at least five times during the second study session: at the beginning of the session (baseline), after IV insertion, and after naloxone-induced opioid withdrawal.

2.4.7. Subjective Pain and Disability Measures.

At the beginning of each session, participants rated their least, average, and most pain over the last two weeks on a visual analog scale (VAS; 0 = no pain to 10 = most pain you could imagine), as well as their hyperalgesia and relative sensitivity to pain. The Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1961), with a total score from 0 (not depressed) to 63 (more severe depression) and the Roland Morris Disability Index (Roland and Morris, 1983), a 24-question instrument assessing disability from lower back pain were also administered at the beginning of each session.

2.4.8. Physical Vital Signs.

During the study sessions, several vital signs were measured and recorded: heart rate and blood oxygen levels with a pulse-oximeter (Propaq® CS Monitor, WelchAllyn; pupil diameter with a pupilometer (PRL-200™, NeurOptics); and blood pressure and respiratory rate by the blinded research assistant. Vital signs were taken at the same five or seven time points as OOWS and SOWS.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS® software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Students’ t-tests for paired samples were used to compare differences between the primary outcome measure (OOWS) and secondary outcome measures (SOWS, POMS, Roland-Morris Disability Index and Beck Depression score) for treatment groups (placebo vs. ondansetron).

2.5.1. Sample Size Calculation.

Sample size analysis for our study was based on data from a preliminary study in which we investigated the effects of ondansetron pretreatment on changes in OOWS scores after naloxone-precipitated withdrawal compared to scores with placebo pretreatment (Chu et al., 2009). We computed differences in OOWS scores, from baseline in session one (time point 1a in Figure 2) prior to morphine titration to 15 minutes after naloxone was given in session two (time point 3b in Figure 2), for each patient in the morphine plus placebo or morphine plus ondansetron titration groups, along with the mean and standard deviation (Compton et al., 2004). We aimed for a 20% change in OOWS score from the start of the study to 15 minutes after naloxone precipitated withdrawal to show the treatment effect with a power of 80% and an alpha of 0.05, yielding a target of 23 patients per treatment group. A single baseline measurement (15 minutes post-naloxone administration) was used in analysis based on previous work by Compton et al. (2004) which showed a higher severity of withdrawal symptoms at 15 minutes after naloxone administration compared to 5 minutes.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

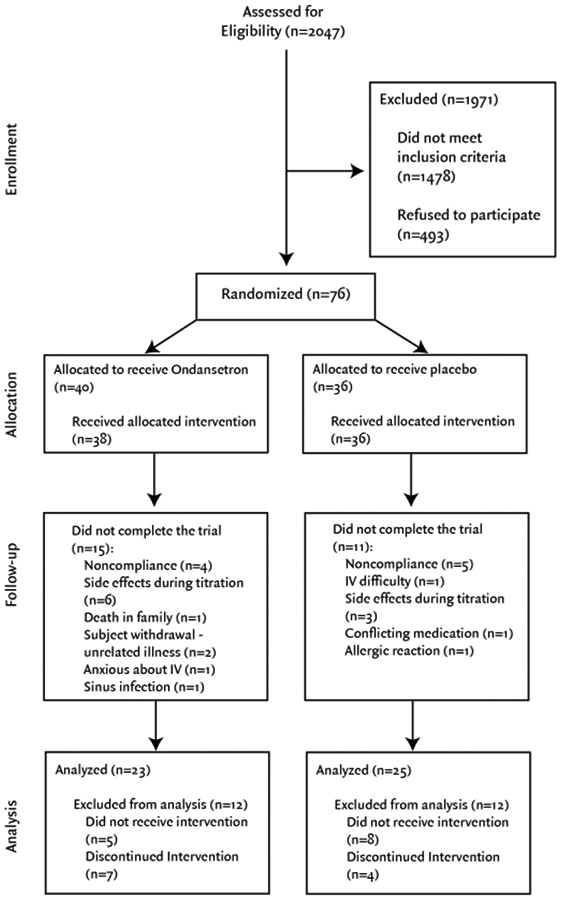

A CONSORT flow diagram of study enrollment and analysis is shown in Figure 1. A total of 2,047 patients were assessed for study eligibility, 1,478 did not meet inclusion criteria and 493 refused to participate (N=1,971 excluded). Of the 76 patients deemed eligible to participate in the study, 26 males and 22 females (n= 48) completed the study (Table 1). A total of ten patients dropped out because of titration side effects, 9 were dropped by study personnel because of titration non-compliance and 9 dropped out for other reasons (Table 2). A total of 23 participants were randomized to receive Ondansetron, while 25 were randomized to receive placebo. Mean opioid dose among pre-existing opioid users (n=7) was 20.4 ± 21.8 morphine equivalents mg/day at baseline. Baseline average pain measured by VAS score (1–10) was 5.2 ± 1.3. Baseline Roland-Morris Disability score (1–24) was 6.9 ± 4.2. Finally, baseline depression score (Beck Depression Inventory) was 4.0 ± 3.6. Participant recruitment began in April 2013 and the study was marked as completed in April of 2015, follow up occurred for each study participant for one year from their study completion date.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of participants. *

| Characteristic | Ondansetron (N=23) | Placebo (N=25) | Total (N=48) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (no.) | |||

| Male | 13 | 13 | 26 |

| Female | 10 | 12 | 22 |

| Age (yr) | 40.1 ± 11.8 | 38.6 ± 10.9 | 39.3 ± 11.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 83.5 ± 18.3 | 92.4 ± 21.7 | 88.1 ± 20.4 |

| Height (cm) | 172.8 ± 10.8 | 176.1 ± 12.5 | 174.5 ± 11.7 |

| Body Mass Index | 27.9 ± 5.3 | 29.8 ± 6.5 | 28.9 ± 5.9 |

| Race (no.) Caucasian | |||

| African-American | 16 | 17 | 33 |

| Asian | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Other | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Baseline Average Pain § | 5.0 ± 1.4 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 1.3 |

| Pre-existing Opioid Therapy (no.) | |||

| Opioid naïve in past 5 years | 12 | 9 | 21 |

| Some opioid exposure in past 5 years | 7 | 10 | 17 |

| Either chronic or intermittent opioid exposure in past 5 years | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chronic opioid use in past 5 years | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Current chronic opioid use | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Average Pre-existing Opioid Dose (morphine equivalents mg/day) | 0.6 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 15.3 | 3.4 ± 11.3 |

| Average Opioid Dose Among Preexisting Opioid Users (morphine equivalents mg/day) | 4.2 ± 1.4 | 32.5 ± 22.2 | 20.4 ± 21.8 |

| Baseline Beck Depression Inventory† | 4.4 ± 3.1 | 3.7 ± 4.1 | 4.0 ± 3.6 |

| Baseline Roland-Morris Disability Index‡ | 7.3 ± 4.1 | 6.4 ± 4.4 | 6.9 ± 4.2 |

Plus-minus values are means ± SD.

Intensity of pain was as reported by patients on a visual-analogue scale labeled “no pain” at 0 mm and “worst pain imaginable” at 100 mm.

Beck Depression Inventory is a single score between 0 to 63; higher scores indicate more severe depression.

Roland-Morris Disability Index yields a score between 0 and 24; higher scores indicate more pronounced disability.

Table 2.

OOWS, SOWS and POMS survey results.

| Ondansetron a (N= 23) | Placebo a (N= 25) | Group Effect b P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-withdrawal OOWS | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 0.1 |

| Withdrawal OOWS Δ OOWS | 5.7 ± 2.6 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 1 |

| (Withdrawal-Prewithdrawal) | 4.5 ± 2.5 | 4.2 ± 2.4 | 0.6 |

| P Value c | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| Pre-withdrawal SOWS | 1.7 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 2.0 | 0.6 |

| Withdrawal SOWS Δ SOWS | 18.0 ± 13.7 | 13.9 ± 10.2 | 0.2 |

| (Withdrawal-Prewithdrawal) | 16.4 ± 13.1 | 12.0 ± 10.0 | 0.2 |

| P Value c | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| Pre-withdrawal POMS | −0.9 ± 9.7 | −3.5 ± 12.1 | 0.4 |

| Withdrawal POMS Δ POMS | 35.2 ± 30.9 | 25.2 ± 29.2 | 0.3 |

| (Withdrawal-Prewithdrawal) | 36.1 ± 27.6 | 29.2 ± 26.3 | 0.4 |

| P Value c | <.0001 | <.0001 |

Analysis of results reported as mean ± SD.

Group effects for pre-withdrawal and withdrawal scores were not significant.

Differences in scores between pre-withdrawal and withdrawal were significant (p < 0.0001).

3.2. Primary Outcome Measures

3.2.1. Objective Opioid Withdrawal Scale.

Overall, all patients showed clinically significant signs of withdrawal as measured by OOWS scores (p < 0.0001). Change in OOWS scores before and after naloxone administration did not differ significantly between ondansetron and placebo groups (ΔOOWS ondansetron = 4.5 ± 2.5, ΔOOWS placebo = 4.2 ± 2.4, p = 0.6). There was also not a significant difference in pre-withdrawal (p = 0.1) or withdrawal (p = 1.0) OOWS scores between treatment groups (Table 2).

Eleven participants did not display sufficient signs of withdrawal (OOWS score <6) after the first dose of naloxone (0.4 mg/70kg). These eleven participants consented to receive a second dose of naloxone (0.8 mg/70kg), which then produced an OOWS score of >6 indicating sufficient withdrawal for study purposes. Replacing the first OOWS score with the second OOWS score after the second naloxone dose, where applicable, did not change study results.

3.3. Secondary Outcome Measures

3.3.1. Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale.

All patients demonstrated clinically significant signs of withdrawal when measured subjectively (SOWS, p < 0.0001). However, similar to OOWS, increases in SOWS scores before and after naloxone administration did not differ significantly between treatment groups (ΔSOWS ondansetron = 16.4 ± 13.1; ΔSOWS placebo = 12.0 ± 10.0; p = 0.2). In addition, pre-withdrawal (p = 0.6) and withdrawal (p = 0.2) SOWS scores did not differ between groups (Table 2).

3.3.2. Profile of Mood States.

All participants showed clinically significant changes in mood state after naloxone-precipitated withdrawal (ΔPOMS = 32.5 ± 26.9, p < 0.0001). Change in POMS score pre-withdrawal (p = 0.4) and post-withdrawal (p = 0.3) was not affected by the treatment group (p = 0.4). Change in mood state for patients receiving ondansetron was 36.1 ± 27.6, and for patients receiving placebo was 29.2 ± 26.3.

POMS scores were compared for participants between the beginning of session 1 and session 2 to determine a possible change in mood states after one month of morphine. There was no statistically significant change in mood states overall (ΔPOMStitration = −1.4 ± 12.6; p = 0.5). There was also no statistically significant difference between treatment groups for change in mood states after one month of morphine (p = 0.5; Table 2).

3.3.3. Subjective Pain and Disability Measures.

After a month of morphine, the average pain score was reduced by −2.9 ± 1.6 points. In addition, the Roland-Morris Disability Index also decreased on average (−3.2 ± 3.9) among patients in the study after one month of morphine. The Beck Depression score decreased slightly on average (−0.2 ± 2.9). There was no observed difference between treatment groups on reported pain. However, a slightly greater decrease in Roland-Morris Disability score in patients receiving ondansetron compared to placebo was observed (p = 0.02) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary outcome measures change from baseline to session 2.a

| Outcome | Ondansetron (N=23) | Placebo (N=25) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Least VAS Pain | −2.3 ± 1.9 | −2.3 ± 1.6 | 1 |

| Average VAS Pain | −2.9 ± 1.4 | −2.8 ± 1.9 | 0.84 |

| Worst VAS Pain | −3.5 ± 2.5 | −3.4 ± 2.7 | 0.89 |

| Roland-Morris | |||

| Disability Index | −4.6 ± 4.2 | −2.0 ± 3.1 | 0.02b |

| Beck Depression Inventory | −0.6 ± 2.6 | 0.2 ± 3.1 | 0.34 |

Mean score changes and standard deviations reported.

Only Roland-Morris Disability Index was found to be significant (alpha = 0.05).

3.4. Morphine Treatment

Data on pills consumed was determined by counting the remaining pills at the start of the withdrawal session, then dividing over the total number of days participants took the morphine pills. The average number of 15mg morphine pills used per day in the ondansetron group (N=23) was 4.1±2.2, the total number of opioid pills used was 106.4±53.5 and the average length of morphine treatment was 31.0±1.8 days. The average number of 15mg morphine pills used per day in the placebo group (N=25) was 5.7±2.1, the total number of opioid pills used was 151.0±51.4 and the average length of morphine treatment was 32.1±2.2 days.

4. Discussion

4.1. Major Findings

Preventing physical dependence and other maladaptive changes in patients receiving ongoing opioid therapy is an important clinical goal. Very few studies have attempted to measure prospectively the pharmacological modulation of prescription opioid tolerance, making this a unique undertaking. We hypothesized that the 5HT3 receptor antagonist ondansetron would be effective in preventing opioid physical dependence in chronic back pain patients receiving morphine for one month. Previous work suggested that the one-month timeframe would be appropriate as tolerance develops within this time frame using the selected morphine titration protocol (Chu et al., 2006). The specific hypothesis tested arose from findings suggesting that the 5HT3 receptor plays a role in the expression of opioid withdrawal and physical dependence (Chu et al., 2009).

On average, subjects in the ondansetron group took fewer total opioid pills than those in the placebo group (106.4 ± 53.5 vs. 151.0 ± 51.4), and had a lower average number of opioid pills used per day (4.1 ± 2.2 vs 5.7 ± 2.1). There was a statistically significant difference in the final morphine dose achieved for the ondansetron and placebo group (p = 0.01, alpha = 0.05), the total morphine used between the ondansetron and placebo group (p = 0.005, alpha = 0.05), and the total amount of ondansetron consumed versus the total amount of placebo consumed (89.65 ± 4.96 vs. 93.88 ± 6.36, p = 0.013, alpha = 0.05).

When withdrawal was induced with naloxone, patients in the Ondansetron group had greater ΔSOWS (16.4 ± 13.1 vs 12.0 ± 10.0), and greater ΔPOMS (36.1 ± 27.6 vs 29.2 ± 26.3), and very similar ΔOOWS (4.5 ± 2.5 vs 4.2 ± 2.4). In short, the two groups experienced similar naloxone-induced delta in objective withdrawal symptoms (as measured by the researchers), but greater subjective withdrawal symptoms were reported by the ondansetron group.

This may indicate a lowering of physical dependence, as patients taking ondansetron may have needed less opioid to manage their pain, or may have felt they needed less opioid to prevent withdrawal symptoms, during the study period. However, we hypothesized there would be a decrease in withdrawal signs and symptoms from baseline to the final withdrawal session, and the ondansetron group did not show a statistically significant difference in OOWS or SOWS scores between those two sessions. Data on the time course of morphine titration was not collected, only the final morphine dose for each participant; extending the study beyond 30 days and tracking how fast morphine doses were increased in ondansetron versus placebo groups may reveal differences. Further research into the effect of ondansetron on the total and average amounts of morphine, and the titration rate, should be explored.

The results of the present study stand in contrast to the results of earlier work showing a treatment effect of ondansetron on patients in a human acute physical dependence model as well as results from experiments in mice. Our post-hoc calculations show that we had 80% power to detect a treatment effect as low as a 34% reduction of the average post-naloxone withdrawal OOWS score measured in the placebo group, our primary outcome.

4.2. Possible Explanations of Results

The outcomes of the present investigation and the discrepancy between those findings and previous results may be attributed to several potential causes. First, we used a chronic physical dependence model in this study, as opposed to the acute physical dependence model in previous studies that showed a treatment effect of ondansetron (Chu et al., 2009). The previously employed technique involved the analysis of naloxone-induced withdrawal within a few hours of administering a single intravenous dose of morphine and ondansetron or placebo. In the present work, the subjects took morphine with or without ondansetron three times per day with the last dose the evening before the study day. There may be mechanistic differences when comparing the effects of long-term opioid use to those of acute exposure. A study by Pei et al. found that 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, including ondansetron, attenuated dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens and associated behavior stimulation caused by morphine in an acute setting in rats (Pei et al., 1993). A similar study by Hui et al. showed that giving ondansetron to rats either 7 days prior to, or on the 14th day, of a 3-week titration to morphine dependence in rats lead to decreased physical dependence (Hui et al., 1996). Thus, prevention of physical dependence to morphine in acute and chronic ondansetron dosing has been shown in rats, but the effects on the brain in humans is likely more complicated. It is possible that the substantial neuroplastic effects that occur with chronic opioid exposure are not manifest in subjects within hours of initial exposure (Dacher and Nugent, 2011). A review by Dacher and Nugent (2011) of chronic opiate effects on neuroplasticity points to the modulation of glutamatergic, GABAergic and structural plasticity of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the brain, which has been implicated in opiate addiction by many neuropharmacologic studies. Compared to acute opiate exposure, chronic opiate use may affect the levels of neurotransmitters and associated neural receptors in the brain, altering the effects of ondansetron on opioid withdrawal; this is an area which should be studied further. The protocol used in this set of studies should probably be considered more clinically relevant as it is chronic rather than acute exposure to opioids that results in dependence and other problematic maladaptations.

Second, ondansetron in this study was taken over the entire month of morphine titration and maintained at the same time as each morphine dose. Similar to morphine, subjects would not have been expected to have a high ondansetron blood plasma level at the time of naloxone administration; the T1/2 for ondansetron in humans is approximately 5 hours after oral administration (Lam et al., 2004) suggesting that most subjects had 25% or less peak ondansetron levels at the time of naloxone administration. We did not measure these levels directly. In the present study, our goal was focused on the prevention of dependence rather than the suppression of withdrawal symptoms in already dependent individuals. A related limitation of this study was the exclusion of subjects with a history or risk of opioid addiction who may have developed physical dependence more rapidly and thus may have benefitted more from ondansetron. Our earlier morphine-ondansetron co-administration observations in mice did suggest that we might see an effect in humans using an analogous protocol (Chu et al., 2009). It also seems unlikely that ondansetron simply lost pharmacological effect over the period of exposure. For example, a study by Chen et al. (2009) examined the role of prolonged ondansetron exposure in relieving mechanical allodynia after spinal cord injury and found that ondansetron exposure over seven days reduced mechanical allodynia over the duration of the treatment. While this exposure length is less than the exposure time in our present study and the outcome measures were different, the results do point to the likelihood that 5HT3 blockade was maintained.

Third, there were important differences between this study protocol and that of previous studies examining the effect of ondansetron on physical dependence to opioids (Chu et al., 2009). Our previous study administered ondansetron (8mg) and induced opioid withdrawal in an acute setting, within one study session (~3 hours) and with the same dose of IV morphine (10mg/70kg over 10 minutes) and naloxone for all participants. The current study included a greater variability in morphine dose dictated by each participant’s side effects and dose required for adequate analgesia, in a chronic opioid and ondansetron setting over 30 days. The greater variability in morphine dose was may have more closely mirrored opioid use in the general population, however likely contributed to more heterogeneous effects, and the overall decreased difference in the subjective and objective opioid withdrawal symptoms of the participants. In addition, our previous study recruited healthy male volunteers, and assessed the effects of ondansetron on OOWS and SOWS within subjects. This study recruited participants with preexisting opioid use and compared between ondansetron and placebo groups in a between-subjects test. The effect of ondansetron may have been diminished in participants with chronic opioid use. Furthermore, this study used naloxone-precipitated change in withdrawal signs and symptoms as a proxy for physical dependence, whereas other measures may be more sensitive to the effect of ondansetron, such as analyzing regional changes in neural activity using fMRI, as was done by Chu et al., (2015).

Fourth, we may have used an ineffective dose of ondansetron (8 mg). We chose to use an 8mg dose of ondansetron with each dose of morphine as this is a dose commonly used for chemotherapy-related nausea prophylaxis. However, previous studies identified as unusual dose-response relationship. A review by Tramèr, et al. (1997) showed that there was no dose response relationship between 1 mg and 8 mg for intravenous administration of ondansetron in preventing post-operative nausea and vomiting. However, additional antiemetic effect was seen when the oral dose was increased from 8 mg to 16 mg implying that a higher dose might have provided a greater effect in our model. Furthermore, an animal study investigating the blockade of cocaine sensitization and tolerance with ondansetron found an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve for the drug (King et al., 1997). Data from an earlier study investigating the effects of ondansetron on benzodiazepine withdrawal in rats also demonstrated a U-shaped dose-response relationship (Goudie and Leathley, 1990). Taken together, the results from previous studies analyzing the effects of ondansetron at increasing doses indicate its effect on opioid dependence may be heightened at doses higher than the 8mg per day that was used in this study. Additional studies using a range of ondansetron doses, from 8mg to 16mg per day, would help to address the possibility of a similar effect on physical dependence in humans exposed to opioids such as morphine. As the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) no longer recommends using opioids as a first line of treatment for chronic pain, it may be difficult to conduct future studies utilizing a method similar to that used here (CDC MMWR, 2016).

5. Conclusion

This human trial did reinforce earlier results reported using a one-month morphine titration protocol. Consistent with our previous work we showed that administration of chronic opioids for the treatment of moderate to severe low back pain does seem effective in reducing the average VAS pain score and the Roland-Morris Disability Index. This indicates that at least over the course of one month, moderate opioids may be effective. Data from the POMS questionnaire suggest that morphine treatment does not alter mood states such as anger, anxiety, confusion, depression, fatigue or vigor under the conditions we employed and that ondansetron does not seem to confer additional benefit.

Overall our results are discouraging concerning the use of ondansetron and other members of the 5HT3 class of receptor antagonists to prevent some of the problematic consequences of chronic opioid administration. From this investigation, we are unable to support the notion that ondansetron can prevent opioid dependence from developing in chronic pain patients taking opioids over a prolonged period. Importantly, we did not measure the effects of ondansetron on drug liking or other subjective effects of opioids also linked to addiction though animal models have provided mixed results suggesting such effects might exist (Higgins et al., 1992; Higgins and Sellers, 1994). Given the low cost and favorable safety profile of ondansetron, such studies might be considered.

Highlights.

We explored using ondansetron to prevent physical dependence to chronic morphine use.

After a month of morphine therapy with or without ondansetron, withdrawal was induced.

Objective and subjective withdrawal scores suggest no disparity between treatment groups.

Ondansetron does not prevent dependence in regular users of morphine for pain management.

Acknowledgements

We received support from the Stanford Center for Clinical Informatics (Stanford CTSA award number UL1 RR025744 from NIH/NCRR).

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by a grant awarded to Dr. Larry F. Chu from the National Institutes of Health (NIH, 1 R01 DA029078–01A1) and the Stanford University School of Medicine Department of Anesthesiology. Clinical trials registration NCT01549652, protocol ID 5HT3 19821.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J, 1961. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 4, 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby LA, Doering PL, 2007. Buprenorphine for treatment of opioid dependence. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm 64, 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012. CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses – a U.S. epidemic (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report). Updated January 13, 2012 Atlanta, GA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Otway MA, Weaver LC, 2009. Blockade of the 5-HT3 receptor for days causes sustained relief from mechanical allodynia following spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. Res 87, 418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu LF, Clark DJ, Angst MS, 2006. Opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia in chronic pain patients after one month of oral morphine therapy: A preliminary prospective study. J. Pain 7, 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu LF, Liang DY, Li X, Sahbaie P, D’arcy N, Liao G, Peltz G, Clark JD, 2009. From mouse to man: The 5-HT3 receptor modulates physical dependence on opioid narcotics. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 19, 193–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu LF, C. Lin JC, Clemenson A, Encisco E, Sun J, Hoang D, Alva H, Erlendson M, Clark JD, Younger JW, 2015. Acute opioid withdrawal is associated with increased neural activity in reward-processing centers in healthy men: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 153, 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton P, Athanasos P, Elashoff D, 2003. Withdrawal hyperalgesia after acute opioid physical dependence in nonaddicted humans: A preliminary study. J. Pain 4, 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton P, Miotto K, Elashoff D, 2004. Precipitated opioid withdrawal across acute physical dependence induction methods. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 77, 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacher M, Nugent FS, 2011. Opiates and plasticity. Neuropharmacology 61, 1088–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallal GE Randomization plan generator. http://www.randomization.com. March 29, 2013

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R, 2016. CDC guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 65, 1–49. 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. Updated March 18, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudie AJ, Leathley MJ, 1990. Effects of the 5-HT3 antagonist GR38032F (ondansetron) on benzodiazepine withdrawal in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol 185, 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelsman L, Cochrane KJ, Aronson MJ, Ness R, Rubinstein KJ, Kanof PD, 1987. Two new rating scales for opiate withdrawal. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 13, 293–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG, 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)- A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform 42, 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Joharchi N, Nguyen P, Sellers EM, 1992. Effect of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, MDL72222 and ondansetron on morphine place conditioning. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 106, 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins GA, Sellers EM, 1994. Antagonist-precipitated opioid withdrawal in rats: Evidence for dissociations between physical and motivational signs. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 48, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser Yi., Evans E, Grella C, Ling W, Anglin D, 2015. Long-Term course of opioid addiction. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 23, 76–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui SC, Sevilla EL, Ogle CW, 1996. Prevention by the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, ondansetron, of morphine-dependence and tolerance in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol 118, 1004–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King GR, Xiong Z, Ellinwood EH Jr., 1997. Blockade of cocaine sensitization and tolerance by the co-administration of ondansetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and cocaine. Pharmacotherapy (Berl.) 130, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YWF, Javors MA, Ait-Daoud N, Roache JD, Johnson BA, 2004. Relative bioavailability of an extemporaneous ondansetron 4-mg capsule formation versus solution. Pharmacother. 24, 477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti L, Helm S 2nd, Fellows B, Janata JW, Pampati V, Grider JS, Boswell MV, 2012. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician 15 (3 Suppl.), ES9–ES38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF, 1971. Manual for the profile of mood states (POMS). Educational and Industrial Testing Services; San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ, 1998. Conditioning factors in drug abuse, can they explain compulsion? J. Pharmacol 12, 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Q, Zetterstr6m T, Leslie RA, Grahame-Smith DG, 1993. 5-HT 3 receptor antagonists inhibit morphine-induced stimulation of mesolimbic dopamine release and function in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol 230, 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JA, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Reisinger HS, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Brown BS, Agar MH, 2010. Why don’t out-of-treatment individuals enter methadone treatment programmes? Int. J. Drug Policy 21, 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JD, Lupkiewicz SM, Palenik L, Lopez LM, Ariet M, 1983. Determination of ideal body weight for drug dose calculations. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm 40, 1016–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland M, Morris R, 1983. A study of the natural history of low back pain. Part 1: Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine 8, 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sites BD, Beach ML, Davis MA, 2014. Increases in the use of prescription opioid analgesics and the lack of improvement in disability metrics among users. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med 39, 6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramèr MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ, 1997. Efficacy, dose-response, and safety of ondansetron in prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Anesthesiology 87, 1277–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washton AM, Resnick RB, 1981. Clonidine in opiate withdrawal: A review and appraisal of clinical findings. Pharmacotherapy 1, 140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster LR, Webster RM, 2005. Predicting aberrant behavior in opioid-treated patients: Preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Took. Pain Med 6, 432–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]