Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Abstract

Purpose

Effective handovers (handoffs) are vital to patient safety. Medical educators investigated educational interventions to improve handovers in a 2011 systematic review. The number of publications on handover education has increased since then, so authors undertook this updated review.

Method

The authors considered studies involving educational interventions to improve handover amongst undergraduate or postgraduate health professionals in acute care settings. In September 2016, two authors independently conducted a standardized search of online databases and completed a data extraction and quality assessment of the articles included. They conducted a content analysis of and extracted key themes from the interventions described.

Results

Eighteen reports met the inclusion criteria. All but two were based in the United States. Interventions most commonly involved single-patient exercises based on simulation and role-play. Many studies mentioned multiprofessional education or practice, but interventions occurred largely in single-professional contexts. Analysis of interventions revealed three major themes: facilitating information management, reducing the potential for errors, and improving confidence. The majority of studies assessed Kirkpatrick’s outcomes of satisfaction and knowledge/skill improvement (Levels 1 and 2). The strength of conclusions was generally weak.

Conclusions

Despite increased interest in and publications on handover, the quality of published research remains poor. Inadequate reporting of interventions, especially as they relate to educational theory, pedagogy, curricula, and resource requirements, continues to impede replication. Weaknesses in methodologies, length of follow-up, and scope of outcomes evaluation (Kirkpatrick levels) persist. Future work to address these issues, and to consider the role of multiprofessional and multiple-patient handovers, is vital.

Handovers (sometimes known as handoffs) are defined as the transfer of both information about and responsibility for a patient or patients between health care professionals and settings.1,2 All health care professionals must learn and maintain excellent handover skills to ensure the effective communication of essential information about patients,3 to enable interprofessional collaboration,4 and to ensure patient safety.5,6

Background

Resident work hours restrictions put into place by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education7 have led to the unintended consequence of increasing the number of patient handovers8–11—and, in turn, increased attention to problems resulting from handovers amongst physicians and other health care professionals.

Poorly conducted handovers threaten patient safety and the quality and continuity of care.5,12–14 Research has linked handovers to inaccurate assessments and diagnoses, delayed and inappropriate treatment, and medical errors—all of which are associated with increased morbidity and mortality, longer hospital stays, and poor patient satisfaction.8,15,16 Research indicates that handovers may be significant factors in many malpractice claims9 and in a large percentage of sentinel events.9,15,17–19

A decade ago, the Joint Commission20 and the World Health Organization5 recognized the need to improve the quality of handovers. The two organizations issued mandates requiring health care organizations to standardize their approach to handovers and to incorporate handover education into the training of employees to improve consistency and reduce vulnerability to errors. More recently, the Association of American Medical Colleges highlighted the importance of handover education by including it as a core entrustable professional activity for entering residency.21

Ideally, all health care programs would incorporate handover education,9 especially because research shows that such training is effective when done well.1,22 Sadly, in many places handover education is nonexistent or inadequate.8,23–27 Theoretical and pedagogical frameworks are often lacking,2,13,25 and the teaching and assessment methods used—at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels—vary greatly,27 resulting in learners who are unable to apply theory to practice.15

Handover education frequently consists of only the provision of tools such as mnemonics and templates that provide structure, but in the absence of any education in their use.25 More recently, web-based, self-study resources have become available to optimize instructional time, resulting in decreased educational contact.27 Even when training involves more situated approaches such as simulation, it often inappropriately focuses on or overemphasizes the single-patient handover when multiple-patient handovers are likely more realistic in contemporary practice.27 In addition, despite the multiprofessional nature of patient care and the importance of effective communication within teams, interprofessional handover education is rare, and this paucity further hampers the authenticity of many of the current handover-focused learning encounters.6

Gordon and Findley1 conducted a systematic review on handover education in 2011. At that time, the published research on handover education generally lacked scientific rigor. The authors of the studies included in the 2011 review often described interventions inadequately and focused on self-reported changes to participants’ attitudes and confidence, rather than the development of knowledge and skills. Little evidence supported the transfer of skills into the workplace, and no interventions clearly demonstrated improvements in patient safety. Finally, there was a paucity of reporting of theory, pedagogy, or resource requirements.1

The published literature on handover education has increased substantially since Gordon and Findley’s1 review. The aim of this current work is to systematically review the latest evidence regarding handover education, to describe the features of the reported interventions, and to determine whether the interventions are effective and how they function.

Method

No single research paradigm underpins this review. We embraced both positivism (through alignment with the principles of systematic reviewing and synthesizing effectiveness outcomes) and constructivism (through consideration of underpinning theoretical frameworks that inform interventions and synthesis of content and outcomes). We have reported our findings in alignment with the STORIES (STructured apprOach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement.28

Data collection

We considered for inclusion in our review all interventional study designs; we excluded surveys, audits, commentaries, and review articles. Our target population comprised medical students, residents, attending physicians, nursing students, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, operating room technicians, and midwives either practicing in or training to work in acute (hospital-based) health care settings. We excluded studies involving allied health care practitioners whose roles do not include giving or receiving handovers in acute health care settings. We considered reports describing outcomes at all levels of Kirkpatrick’s29 adapted hierarchy.

We conducted our search in September 2016, seeking studies published in or after January 2010. We applied a standardized search strategy (Supplemental Digital Appendix 1, at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A545) to the following databases: Cochrane controlled trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL complete, PsychINFO, ERIC, Proquest health and medical complete, and PubMed. Additionally, we reviewed articles listed as references in included studies, and we contacted experts in the field of medical handovers. We included studies undertaken in any country and published in any language. We, like Gordon and Findley,1 defined an educational intervention as any structured educational activity. We excluded interventions without an educational component, including those that only introduced new handover systems or mnemonics. If only limited information on an intervention was available, we attempted to contact the authors for further details. We did not seek ethical approval for this review because it does not involve study participants.

Data analysis

Two of us (E.H. and M.G.) independently reviewed the titles our search uncovered, and, using a checklist (Supplemental Digital Appendix 2, at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A545), we independently screened potentially relevant abstracts. We assessed agreement using Cohen kappa statistic. We resolved any disagreements through discussion, involving a third author (J.N.S. or M.D.) only if needed. Next, two of us (again E.H. and M.G.) independently reviewed the full articles, determining which studies met our inclusion criteria.

Once we agreed on the studies to include in our review, the two of us used a data extraction form (Supplemental Digital Appendix 3, at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A545) and a quality assessment tool (Supplemental Digital Appendix 4, at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A545) to assess, respectively, the content and quality of the studies, based on guidance from the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration30 and the recommendations of Reed and colleagues.31

Data extraction.

Notably, we slightly modified the data extraction tool from Gordon and Findley’s1 review, which allowed us to rate the studies on the basis of 16 quality-based criteria (e.g., description of learner characteristics, statistical tests). We sought details about the educational intervention described in each study; specifics included recording pedagogical and theoretical underpinnings, format, teaching approaches, the number and types of participants, the length of follow-up, setting, and resources needed.

Quality assessment.

We incorporated a five-point scale (where 1 = weak; 5 = strong) to rate the strength of conclusions drawn from each study.30 The quality assessment tool we used31 allowed us to obtain more detailed information relating to potential sources of bias within the studies reviewed.

Neither the scale nor the quality assessment tools provide an assessment of overall methodological quality, but they do provide measures of how well the data presented support the study conclusions.

Additional analyses.

Additionally, we related study outcomes to Kirkpatrick’s29 adapted hierarchy (see Results) to assess the level of their effectiveness. Finally, two of us (E.H. and M.G.) independently undertook a content analysis of interventions, coding and categorizing the data into themes. We had no disagreements.

Results

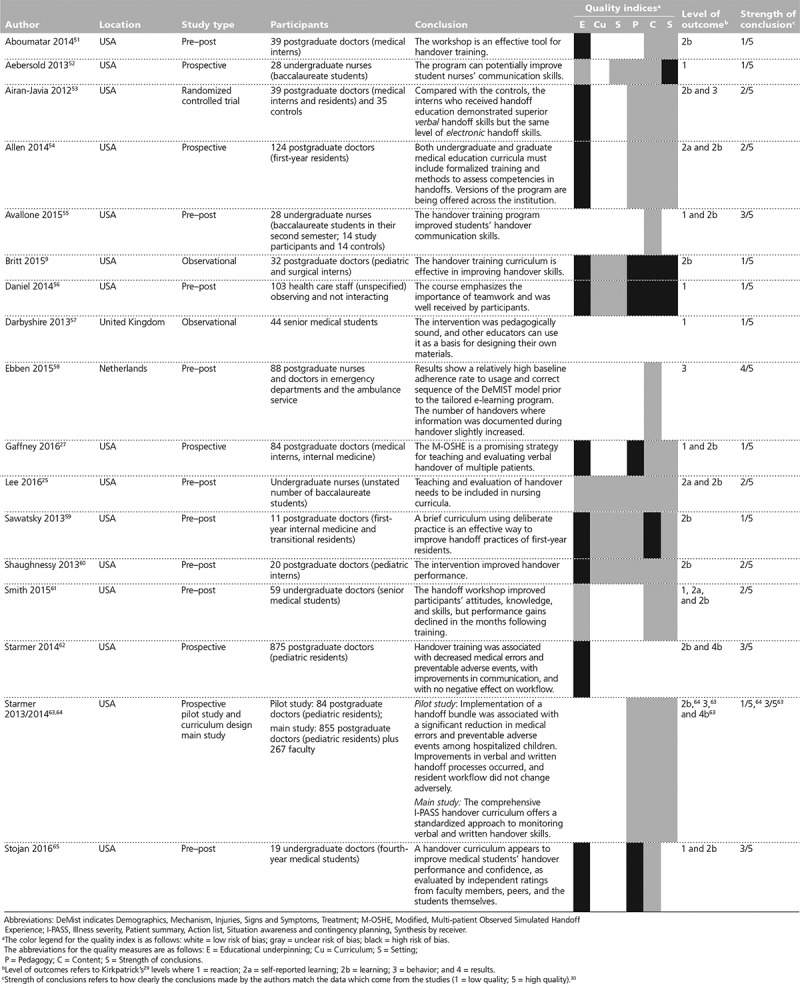

The initial search of electronic databases yielded 7,118 titles, and other sources (reference lists, experts) provided 2 more potential articles. We identified 2,719 of these as duplicates. From the 4,401 remaining articles, we identified 96 abstracts for further screening. Agreement between the authors on citation screening was 100%. Agreement on abstract screening was very high (Kappa = 0.891). Thirty-eight articles met the criteria for full-text screening. We excluded 10 of these,13,32–40 deeming them irrelevant—with no disagreement between the authors. We excluded another 10 reports41–50 because they included insufficient data to judge whether they should be included, and their authors did not respond to multiple attempts to contact them. Ultimately, 18 reports of intervention studies9,25,27,51–65 met our inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 provide a general overview of the 18 reports and the 17 interventions they describe (2 reports63,64 describe the same study). We achieved 100% agreement on the quality ratings after independent data extraction. Supplemental Digital Appendix 5, available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A546, provides a more detailed summary of our ratings of each study’s quality based on the criteria from the two assessment tools.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing inclusion and exclusion of articles for a literature review of studies (published between January 2011 and September 2016) on teaching handover.

We found significant methodological heterogeneity amongst the 18 studies (and the 17 educational interventions they describe). Study participants included medical students, residents, attending physicians, and nurses. The median number of participants in a study was 51.5 (the range was 11–1,206). The studies included 9 pre–post studies,25,51,55,56,58–61,65 6 prospective studies,27,52,54,62–64 1 randomized controlled trial,53 and 2 observational studies.9,57 Sixteen of the studies reported on interventions undertaken in the United States, and only 1 each reported on an intervention in the United Kingdom57 and the Netherlands.58

All educational interventions described in the studies included both (1) providing or sharing information and (2) opportunities for active practice (see Figure 2)—or, in the case of the two online formats,27,58 information provision and knowledge assessment. The order in which the different elements of the programs were presented to participants, and the number and nature of these, varied according to three formats:

Figure 2.

Instructional methods for teaching patient handover in health care, as extracted from studies published between January 2011 and September 2016.

practice handover, receive teaching on handover, practice handover again, and receive feedback;

receive teaching on handover, practice handover, and receive feedback; and

test preexisting knowledge, receive teaching on handover, practice handover, and receive feedback.

We found the study methodologies to be generally poor. Only 4 articles provided details about the educational theory underpinning the intervention,55,57,58,64 and 10 did not even mention an educational theory. Similarly, only 6 articles clearly explained the pedagogy used for the interventions,51,55,57,58,61,62 and 4 did not mention a pedagogy at all. We did find, however, that authors were likely to provide information about context, learners, and teaching approaches. Twelve studies described the setting and learner characteristics, and 13 described the curriculum in suitable detail, including the time and resources needed to implement the intervention and enable replication (see Appendix 1 and Appendix 2).

Our analysis of teaching approaches indicated that the principal teaching methods used were role-play and simulation. These techniques were usually included as part of a package of measures, including didactic sessions, feedback, discussions of video examples of handovers, and sharing of learners’ own experiences. Only two studies included online teaching materials.27,58

We identified three content themes: (1) facilitating information management, (2) reducing the potential for errors, and (3) improving provider confidence (see Figure 3). Facilitating information management was typically addressed by focusing on specific handover techniques, including the use of mnemonics and electronic tools that were aimed at helping providers manage the growing number of increasingly complex and frequent handovers. Reducing the potential for errors was addressed by identifying the components of effective and ineffective handovers (from experience, examples, observation, and feedback on performance); the goal was to help providers understand the positive and negative implications that their choices have on patient safety. Improving provider confidence was addressed by ensuring that participants felt comfortable challenging or requesting additional information from others—regardless of status or perceived hierarchies.

Figure 3.

Instructional content for teaching patient handover in health care as extracted from studies published between January 2011 and September 2016.

Seven studies27,52,55–57,61,65 reported outcomes at Level 1 (reaction) on Kirkpatrick’s29 adapted hierarchy. The overwhelming majority of articles (n = 13) reported outcomes at Level 2 (learning).9,25,27,51,53–55,59–62,64,65 Among these, 3 studies25,54,61 reported outcomes at Level 2a, measuring modifications of attitudes or perceptions; and 13 reported outcomes at Level 2b, measuring changes in knowledge or skills. Only 3 studies53,58,63 reported outcomes at Level 3 (behavioral change), showing the transfer of handover skills into the workplace; and 2 studies62,63 at Level 4b (results), indicating improved patient outcomes as a result of the educational intervention. Some studies reported outcomes at more than one level. Notably, all 4 of the studies that reported Level 3 and 4 outcomes focused on more practical content (in the form of information management) rather than error reduction or confidence boosting.

The strength of conclusions, which we estimated using the BEME scale,30 was poor for 13 of the studies; 8 of these 9,27,51,52,56,57,59,64 achieved of which achieved scores of 1, indicating that no clear conclusions could be drawn and/or that the results were insignificant. Most of these studies drew general conclusions not directly related to the described educational interventions. Five of the studies25,53,54,60,61 achieved scores of 2, indicating that the results were ambiguous but there appeared to be a trend. While the conclusions of these studies were supported by the results, the authors suggested overly broad implications (e.g., concluding that the intervention was a good option to enhance handover teaching upon finding positive learner feedback). Four of the studies achieved BEME scores of 3,55,62,63,65 indicating that the conclusions could probably be based on the results. In these studies, which were largely focused on Level 2 outcomes, the authors suggested that their teaching interventions could improve handover knowledge or attitudes in all settings, not just the study setting. Only 1 study58 achieved a BEME score of 4, indicating that the conclusions were likely true, supported by the results presented (with conclusions linked to the initial research question and supported by the evidence presented).

Discussion

Despite a marked increase in the number of publications on handover education since Gordon and Findley’s1 2011 review, their conclusions remain generally valid. The quality of studies on handover education remains poor. With some notable exceptions of studies with sample sizes of at least 80 participants,27,54,56,58,62–64 sample sizes remain relatively small, and descriptions of interventions that achieve higher levels of Kirkpatrick outcomes remain scarce. We can only speculate on the reasons for this lack of progress, but based on other systematic reviews in medical education, this stagnation seems common. Regrettably, the lack of progress means a paucity of evidence in key areas that educators must address. Specifically, development and advances in research and evidence are necessary to guide curriculum, teaching, and assessment. Importantly, one key development since 2011, uncovered in this synthesis, does have implications: skillful cross-hierarchal communication is clearly core to effective handover education. This finding aligns with wider work in nontechnical skills education.66

Although we intentionally included nurse practitioners, physician assistants, operating room technicians, and midwives in our inclusion criteria, we uncovered no studies that included them. Study authors often discussed multiprofessional education and practice, but handover skills were largely taught in a single-professional context. Published accounts of multiprofessional handover education remain extremely rare. Only one study58 included more than one professional group, and it focused on only two groups (doctors and nurses). Given the interprofessional nature of contemporary patient care, handover education must become truly multidisciplinary if medical educators want to increase good communication among staff and effect safer situations for patients.

As mentioned, we found the study methodologies to be generally poor. A majority of the reports did not mention an educational theory, and fewer than a fourth named a particular pedagogical approach—although most of the reports did include details about the setting, learners, and learning activities. To improve the methodological quality of handover interventions, future reports should not only report details of the intervention in a manner that supports replication by others but also, importantly, focus on the theoretical and pedagogical approaches they are following.66 Without specifics on the educational theory, pedagogy, context, learner characteristics, curriculum, and resource requirements, educators will struggle to produce a local intervention that reflects the best evidence.

As with the previous review,1 the majority of reported outcomes were at level 2 on Kirkpatrick’s29 hierarchy, though we did note some improvements. The results of 2 studies58,63 indicated that the knowledge and skills acquired by learners had transferred to the work environment; the findings of another 2 studies62,63 indicated that the health and well-being of patients had improved as a result of the educational intervention. For policy makers to invest in handover training, more educational programs must achieve and report outcomes at higher Kirkpatrick levels. Lower Kirkpatrick outcome levels do not in any way denote lower-quality studies, and, in fact, such outcomes can be very informative; however, such outcomes are not helpful if the study is executed poorly. Of course, study authors must interpret their outcomes according to the context of the strength of their methodology. The authors of 13 of the studies overstated their conclusions. Despite the conclusions as stated by some authors, the poor execution of a study results in poor evidence, which diminishes the helpfulness of the outcomes (at any Kirkpatrick29 level) for teachers and researchers.

The majority of studies used only brief interventions and focused on single-patient, as opposed to multiple-patient, handovers. The most common time frame for interventions was one hour, though durations varied from 45 minutes to one day. Time constraints placed on educational interventions (by work pressures and the requirements of other aspects of educational programs) have the potential to affect both the quality and effectiveness of handover education. The development of longitudinal or spiral (vertical) handover curricula to enhance retention would represent a contribution to the field.

Five studies focused on slightly longer-term retention of handover skills, knowledge, and/or confidence: after 2 weeks,53,59 15 weeks,55 7 months,60 and 8 to 12 months.65 Such work is clearly of great interest to policy makers and educators across the globe. Only two studies27,58 involved multiple-patient handovers, and only one62 attempted to address the issue of standardized training. Again, it is disappointing that despite a doubling of published evidence in just seven years, few published studies address these key issues.

The majority of the studies acquired no baseline data regarding participants’ handover skills or knowledge prior to the educational intervention. Consequently, we were unable to ascertain whether the educational program was effective at generating improvements. This lack of pre–post comparisons is an identified weakness of handover education programs.61 Possibly, pre–post studies are not vital in the tapestry of medical education evidence, but—given that the studies we examined do not provide information on pedagogy or theory—well-designed comparisons of skills, knowledge, and confidence before and after would be especially valuable. No interventions used simulation scenarios then debriefing, an approach generally rated highly by participants, that research has shown to improve performance.67 Many interventions involved scenarios and role-play instead. All of the interventions included not only information highlighting the importance of good communication but also the opportunity—in some format—to practice and gain feedback. Interestingly, only one study57 drew on participants’ own experiences of handover. Twelve studies included mnemonics,25,54–56,58–65 and participants received training in their use, a significant improvement over many studies previously reported in the literature. Clearly, learning not only a mnemonic, but also how to use it, is vital.

As noted, three key content themes emerged: managing complex information, reducing the potential for errors, and building confidence in handover skills. Gordon and Findley1 also identified the first two themes in 2011. The growth of electronic handover systems has been a focus for education: medical educators want to ensure the appropriate use of emergent technology.

The final theme, developing confidence, is unique to this review. Handover dynamics change depending on the context in which handovers occur. In circumstances and settings where power gradients are reduced, health care professions feel more empowered to raise questions. These settings are characterized by reduced stress and good teamwork. In contrast, settings with powerful, embedded hierarchies tend to engender higher levels of stress and less teamwork,68,69 which, in turn, affect the quality of handovers and, ultimately, patient safety. Providing multiprofessional handover education at all levels of undergraduate and postgraduate medical training may flatten entrenched hierarchies. Interprofessional education has already been identified as a vital nontechnical skill, important for ensuring patient safety and an essential component of any health care curricula,70 and as such, these findings have significant implications for those planning their own handover teaching.

This review has several limitations. Our findings are—as they would be for any review of the literature—bound by the databases that were available to us. We may have missed some relevant studies. We have focused this review on studies for health professionals working in acute hospital settings; thus, we did not evaluate studies on handover education in other settings. Some of the studies that we excluded (on the basis of the brevity of their educational interventions or the insufficiency of information provided) may have offered relevant insights, but these details were not available in the text, and the articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of note, this review focuses only on educational interventions designed to improve handovers—not on any that focus on other approaches to bring about improvements in patient care. The key terms used in the search strategy (e.g., “handover,” “signout”), which vary internationally, may have affected the number of articles we uncovered. Additionally, because of the limitations of the published literature, we could not complete our synthesis of the findings to the level we had initially planned. Sadly, the lack of multiprofessional studies in handover education precludes our ability to comment on the quality of handover teaching for teams—or even determine whether such teaching occurs. Finally, all of the studies included in the review reported positive results, so the potential for publication bias must be considered.

To advance the field, reports of handover interventions need to improve in quality, utility, and reporting (in all areas; theory, follow-up, etc.). Studies must report in greater detail the theory, pedagogical approach, teaching methods, and learning resources supporting the intervention. Studies investigating more authentic handover teaching, such as interventions that involve practicing multiple-patient handovers rather than single-patient handovers, are needed. Finally, studies with larger numbers of participants, longer-term follow-up, and an emphasis on multidisciplinary training would add value. These studies should be based on sound pedagogical principles and ideally demonstrate a positive effect on patient safety outcomes at all levels of Kirkpatrick’s29 hierarchy.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Annette Ramsden from University of Central Lancashire Library Services.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1 Characteristics and Quality Indices of 18 Studies of Handover Interventions, Published Between January 2011 and September 2016

Appendix 2 Included Studies’ Description of Intervention, Outcome Measure, and Key Result

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: Dr. Gordon has received travel grants from various companies to support attendance at scientific meetings. These companies have had no involvement in this or any other work completed by Dr Gordon.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A545 and http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A546.

References

- 1.Gordon M, Findley R. Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: A systematic review. Med Educ. 2011;45:1081–1089.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kicken W, Van der Klink M, Barach P, Boshuizen HP. Handover training: Does one size fit all? The merits of mass customisation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(suppl 1):i84–i88.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nursing and Midwifery Council United Kingdom. Standards for pre-registration nurse education. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/standards/nmc-standards-for-pre-registration-nursing-education.pdf. Published September 2010. Accessed March 3, 2018.

- 4.Acharya R, Tham KY, Tan E, et al. Deconstructing the general medical ward rounds through simulation—“simrounds”—A novel initiative for medical students designed to enhance clinical transitions and interprofessional collaboration. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013;42(9 suppl 1):S178. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Patient Safety Solutions. Communication during patient hand-overs. Patient safety solutions. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/solutions/patientsafety/PS-Solution3.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed March 3, 2018.

- 6.Doyle KE, Cruickshank M. Stereotyping stigma: Undergraduate health students’ perceptions at handover. J Nurs Educ. 2012;51:255–261.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Updated 2013. Accessed March 13, 2018.

- 8.Bump GM, Jacob J, Abisse SS, Bost JE, Elnicki DM. Implementing faculty evaluation of written sign-out. Teach Learn Med. 2012;24:231–237.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britt RC, Ramirez DE, Anderson-Montoya BL, Scerbo MW. Resident handoff training: Initial evaluation of a novel method. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37:75–80.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez ME, Manicone PE, Davies JL, et al. Assessing the impact of a web-based educational intervention on the patient handoff process among pediatric residents: A pre and post test evaluation. Int J Child Adolesc Health. 2011;4:175–181.. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antiel RM, Reed DA, Van Arendonk KJ, et al. Effects of duty hour restrictions on core competencies, education, quality of life, and burnout among general surgery interns. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:448–455.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keogh B. Review into the quality of care and treatment provided by 14 hospital trusts in England: Overview report. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/bruce-keogh-review/Documents/outcomes/keogh-review-final-report.pdf. Published July 2013. Accessed March 13, 2018.

- 13.Dekosky AS, Gangopadhyaya A, Chan B, Arora VM. Improving written sign-outs through education and structured audit: The UPDATED approach. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:335–336.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benham-Hutchins MM, Effken JA. Multi-professional patterns and methods of communication during patient handoffs. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79:252–267.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gore A, Leasure AR, Carithers C, et al. Integrating hand-off communication into undergraduate nursing clinical courses. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2015;5:70–76.. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeffcott SA, Evans SM, Cameron PA, Chin GS, Ibrahim JE. Improving measurement in clinical handover. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:272–277.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubosh NM, Carney D, Fisher J, Tibbles CD. Implementation of an emergency department sign-out checklist improves transfer of information at shift change. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:580–585.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: A systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775–1787.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Studdert DM, et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:533–540.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joint Commission. Improving America’s hospitals: The Joint Commission’s annual report on quality and safety. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2007_Annual_Report.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed March 13, 2018.

- 21.Englander R, Flynn T, Call S, et al. Core entrustable professional activities for entering residency. https://icollaborative.aamc.org/resource/887/. Published 2014. Accessed March 13, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Gordon M. Handover in paediatrics: Junior perceptions of current practise within the North West region. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(suppl 1):69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girdley D, Johnsen C, Kwekkeboom K. Facilitating a culture of safety and patient-centered care through use of a clinical assessment tool in undergraduate nursing education. J Nurs Educ. 2009;48:702–705.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Toole JK, Stevenson AT, Good BP, et al. ; Initiative for Innovation in Pediatric Education–Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings Accelerating Safe Signouts Study Group. Closing the gap: A needs assessment of medical students and handoff training. J Pediatr. 2013;162:887–888.e1.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J, Mast M, Humbert J, Bagnardi M, Richards S. Teaching handoff communication to nursing students: A teaching intervention and lessons learned. Nurse Educ. 2016;41:189–193.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyons MN, Standley TD, Gupta AK. Quality improvement of doctors’ shift-change handover in neuro-critical care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaffney S, Farnan JM, Hirsch K, McGinty M, Arora VM. The modified, multi-patient observed simulated handoff experience (M-OSHE): Assessment and feedback for entering residents on handoff performance. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:438–441.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon M, Gibbs T. STORIES statement: Publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC Med. 2014;12:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkpatrick DL. Craig RL, Bittel LR. Evaluation of training. In: Training and Development Handbook. 1967:New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 87–112.. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammick M, Dornan T, Steinert Y. Conducting a best evidence systematic review. Part 1: From idea to data coding. BEME guide no. 13. Med Teach. 2010;32:3–15.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed D, Price EG, Windish DM, et al. Challenges in systematic reviews of educational intervention studies. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(12 pt 2):1080–1089.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornell P, Gervis MT, Yates L, Vardaman JM. Improving shift report focus and consistency with the situation, background, assessment, recommendation protocol. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43:422–428.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emlet LL, Al-Khafaji A, Kim YH, Venkataraman R, Rogers PL, Angus DC. Trial of shift scheduling with standardized sign-out to improve continuity of care in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:3129–3134.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallagher D. Crew resource management … following up. Nurs Manage. 2016;47:50–54.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pukenas EW, Dodson G, Deal ER, Gratz I, Allen E, Burden AR. Simulation-based education with deliberate practice may improve intraoperative handoff skills: A pilot study. J Clin Anesth. 2014;26:530–538.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reyes JA, Greenberg L, Amdur R, Gehring J, Lesky LG. Effect of handoff skills training for students during the medicine clerkship: A quasi-randomized study. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21:163–173.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ronnebaum J, Carlson J. Does education in an evidence-based teamwork system improve communication with emergency handoffs for physical therapy students? A pilot study. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2015;6:71–76.. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rourke L, Boyington C. A workshop to introduce residents to effective handovers. Clin Teach. 2015;12:99–102.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Telem DA, Buch KE, Ellis S, Coakley B, Divino CM. Integration of a formalized handoff system into the surgical curriculum: Resident perspectives and early results. Arch Surg. 2011;146:89–93.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collins G. Using simulation to develop handover skills. Nurs Times. 2014;110:12–14.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beck EH, Ahn J. TF-7 emergency medicine resident transitions of care curriculum. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:S158–S159.. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Godfrey E, Hassan I, Carson-Stevens A, Saayman AG. Safer ICU trainee handover: A service improvement project. Crit Care. 2012;16(suppl 1):P518. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gresens AA, Britt RC, Anderson-Montoya BL, Ramierz DE, Scerbo M. Improving the quality and content of the surgical handoff: An innovative method. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:S118. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller AA, Ziegler O. Reinventing the hospital handoff for clinical education. J Physician Assist Educ. 2016;27:99–100.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moss S. A quality improvement project to develop nursing handover in the neonatal intensive and special care unit (nisc). J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:93. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mueller S, Patel R, O’Toole J, Schnipper J. Best practices in inpatient handoffs of care. Hosp Med Clin. 2016;5:518–528.. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parikh P, Pechman D, Gutierrez K, et al. The effect of structured handover on the efficiency of information transfer during trauma sign-out. J Surg Res. 2013;179:345. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perry K, Fant AL, Farmer B. Ed-pass: A novel approach to standardized ed hand-offs. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:S440. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramirez DW, Britt RC, Scerbo MW, et al. Assessing the efficacy of pediatric intern hand-off training. Acad Ped. 2013;13:e2–e3.. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang D, Sabri E, Krympotic K, Lobos A. Using SBAR (situation, background, assessment and recommendations) to improve resident communication. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:e83. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aboumatar H, Allison RD, Feldman L, Woods K, Thomas P, Wiener C. Focus on transitions of care: Description and evaluation of an educational intervention for internal medicine residents. Am J Med Qual. 2014;29:522–529.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aebersold M, Tschannen D, Sculli G. Improving nursing students’ communication skills using crew resource management strategies. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52:125–130.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Airan-Javia SL, Kogan JR, Smith M, et al. Effects of education on interns’ verbal and electronic handoff documentation skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:209–214.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allen C, Gould L, Ballantyne J, et al. Improving handover on the intensive care unit: A completed audit cycle. Anaesthesia. 2014;70:56.25267493 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Avallone MA, Weideman YL. Evaluation of a nursing handoff educational bundle to improve nursing student handoff communications: A pilot study. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2015;5:65–75.. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daniel L, N-Wilfong D. Empowering interprofessional teams to perform effective handoffs through online hybrid simulation education. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2014;37:225–229.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darbyshire D, Gordon M, Baker P. Teaching handover of care to medical students. Clin Teach. 2013;10:32–37.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ebben RH, van Grunsven PM, Moors ML, et al. A tailored e-learning program to improve handover in the chain of emergency care: A pre-test post-test study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2015;23:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sawatsky AP, Mikhael JR, Punatar AD, Nassar AA, Agrwal N. The effects of deliberate practice and feedback to teach standardized handoff communication on the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of first-year residents. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:279–284.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shaughnessy EE, Ginsbach K, Groeschl N, Bragg D, Weisgerber M. Brief educational intervention improves content of intern handovers. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:150–153.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith CJ, Peterson G, Beck GL. Handoff training for medical students: Attitudes, knowledge, and sustainability of skills. Educ Med J. 2015;7:e15–e26.. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. ; I-PASS Study Group. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1803–1812.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Starmer AJ, Sectish TC, Simon DW, et al. Rates of medical errors and preventable adverse events among hospitalized children following implementation of a resident handoff bundle. JAMA. 2013;310:2262–2270.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. ; I-PASS Study Education Executive Committee. Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: A multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014;89:876–884.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stojan J, Mullan P, Fitzgerald J, et al. Handover education improves skill and confidence. Clin Teach. 2016;13:422–426.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gordon M, Box H, Farrell M, et al. Non-technical skills learning in healthcare through simulation education: Integrating the SECTORS learning model and complexity theory. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2015;1:67–70.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dickinson D. Human patient simulation training. Pract Nurse. 2011;41:27–29.. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stephan WG, Stephan CW, Gudykunst WB. Anxiety in intergroup relations: A comparison of anxiety/uncertainty management theory and integrated threat theory. Int J Intercult Rel. 1999;23:613–628.. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flin R, O’Connor P, Crichton M. Safety at the Sharp End: A Guide to Non-technical Skills. 2008Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gordon M. Where is the risk of bias? Considering intervention reporting quality. Med Educ. 2017;51:874–875.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]