Abstract

Background

Women may be more vulnerable than men to HIV-related cognitive dysfunction due to sociodemographic, lifestyle, mental health, and biological factors. However, studies to date have yielded inconsistent findings on the existence, magnitude and pattern of sex differences. We examined these issues using longitudinal data from two large, prospective, multisite, observational studies of U.S. women and men with and without HIV.

Setting

Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) and Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS).

Methods

HIV-infected (HIV+) and uninfected (HIV−) WIHS and MACS participants completed tests of psychomotor speed, executive function, and fine motor skills. Groups were matched on HIV status, sex, age, education, and black race. Generalized linear mixed models were used to examine group differences on continuous and categorical demographically-corrected T-scores. Results were adjusted for other confounding factors.

Results

The sample (n=1420) included 710 women (429 HIV+) and 710 men (429 HIV+) (67% NonHispanic-Black; 53% high school or less). For continuous T-scores, Sex by HIV Serostatus interactions were observed on the Trail Making Test (TMT) Parts A&B, Grooved Pegboard, and Symbol Digit Modalities Test. For these tests, HIV+ women scored lower than HIV+ men, with no sex differences in HIV− individuals. In analyses of categorical scores, particularly TMT Part A and Grooved Pegboard Non-Dominant, HIV+ women also had a higher odds of impairment compared to HIV+ men. Sex differences were constant over time.

Conclusions

Although sex differences are generally under-studied, HIV+ women versus men show cognitive disadvantages. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying these differences is critical for tailoring cognitive interventions.

Approximately 50% of HIV-infected (HIV+) individuals develop cognitive impairment.1, 2 Cognitive function in HIV+ men has been well characterized, as most HIV+ individuals living in the U.S. and participating in cohort studies are male.1–3 Women comprise approximately 25% of HIV cases4 in the U.S. and half of global cases.5 HIV+ women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS)6 show small but significant deficits in cognitive function, particularly in verbal learning and memory, and processing speed6, 7. Few studies have directly compared cognitive function of HIV+ women and men, even though cognitive profiles of HIV+ women cannot be assumed to be the same as HIV+ men.8 Including HIV-uninfected (HIV−) controls in such comparisons is important to determine the expected pattern of sex differences.

Women may be more vulnerable to HIV-associated cognitive impairment compared with men due to biological differences (e.g., hormonal, pharmacokinetic) as well as poverty, low literacy, low education, substance abuse, poor mental health, early life stressors, trauma, and barriers to health care. Some studies suggest greater cognitive vulnerabilities in HIV+ women compared to HIV+ men3, 9, 10 while others suggest no difference11 or show differences only in the pattern of impairment12.

We compared cognitive test performance in a matched subset of HIV+ and HIV− women from WIHS and HIV+ and HIV− men from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) who were comparable in age, education and black race. Given prior findings13–15, we predicted that HIV+ women would perform worse than HIV+ men.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Previous reports detail the WIHS and MACS recruitment, retention, and study procedures16–19. Both studies received institutional review board approval at each WIHS and MACS sites. All participants provided written informed consent before any research procedures.

Participants

The WIHS is a longitudinal study of the natural and treated history of HIV in women that was established in August 1994 at 6 clinical sites in Brooklyn, New York; Bronx/Manhattan, New York; Washington, DC; Los Angeles, California; San Francisco/Bay Area; and Chicago. WIHS participants in this cognitive analysis were enrolled from 1994–1996 (n=2,623) or 2001–2002 (n=1,143) for a total of 3,766 (2,791 HIV+ and 975 HIV− women). An identical number of HIV+ and HIV− male participants were drawn from 6972 individuals enrolled in the MACS, an ongoing longitudinal study of HIV+ and HIV− self-identified men who have sex with men (MSMs). The MACS was initiated in 1984 with study sites in Los Angeles, Chicago, Baltimore, and Pittsburgh. MACS has recruited three cohorts of participants18. From 1984–1985, 4954 men were enrolled, from 1987–1991 668 men were enrolled, and from 2001–2003 another 1350 were enrolled. Men included in this analysis were from that third enrollment, who more closely approximate the WIHS ethnic and educational composition. Men and women who completed the four tests that overlap in the WIHS and MACS — Trail Making Test A&B (TMTA and TMTB), the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), Stroop, and Grooved Pegboard (GP) — were eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Exclusion criteria included history of toxoplasmosis, brain lymphoma, cryptococcal meningitis (MACS) or cryptococcal infection (WIHS), progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, dementia, transient ischemic attack or stroke, use of antiseizure or anti-psychotic drugs, loss of consciousness (> 1 hour for MACS, > 30 minutes for WIHS), preference for Spanish as first language, and American Indian/Alaskan Native (WIHS only) due to lack of matching participants in the MACS.

Procedures

We examined performance on overlapping tests in WIHS and MACS, including TMTA & TMTB (time to complete), GP (time to complete), SDMT (number of boxes correctly completed within 90 sec), and Stroop (time to complete). All timed measures were right skewed and therefore log transformed. Similar to our previous publications,6, 20–22 demographically adjusted T-scores were created for each outcome. Impairment was examined with continuous T-scores and categorical (scoring in the impaired range, T<40). T-scores were derived for each individual outcome adjusting for sex, age, years of education, race (African American vs not), ethnicity (Hispanic vs not), and number of previous test administrations (second, third, or later). The T-scores attenuate the expected sex differences in HIV− individuals.

In the WIHS, an abbreviated cognitive battery, including TMTA, TMTB, and SDMT was implemented in 2004 at core visits at the six original WIHS sites to 1142 HIV+ women and 511 controls. Participants completed the tests every six months over a two-year period. In 2005–2006, the Stroop test was simultaneously administered to 1426 women as part of a cross-sectional WIHS study23. In 2009, a more comprehensive cognitive battery was administered once every two years to 1604 WIHS participants at the original 6 sites. That battery included four tests employed by the MACS, including the TMTA&B, SDMT, GP, and Stroop6. WIHS and MACS investigators worked together to maximize comparability of tests, and test administration and scoring procedures. At WIHS core visits, participants underwent physical and gynecological examinations, medical and psychosocial interviews, assessment of current medications and adherence, and a blood draw. This study used WIHS data collected from May 2009 to September 2016.

Neuropsychological testing in the MACS has been summarized18. From 1988 onward, the MACS semi-annual clinical assessment included the TMT and SDMT. From 1988–2005 approximately 80% of the men also participated in a more extensive neuropsychological examination that also included the GP and Stroop Tests. In 2005 all MACS participants completed the more extensive battery at least every two years.18 The MACS semiannual core visits include an interview covering physical health, medical treatments, and sexual and substance use behaviors, a physical examination, and blood draw. Cognitive batteries from October 2001 through May 2014 were included in the analysis.

Matching

Participants were matched at the first cognitive visit with valid TMTA&B, SDMT, Stroop, and GP data. Participants were matched on HIV serostatus, age (+/− 5 years), and education groups of high school or less, some college, and 4 years college (excluding those with post-college education). We matched on race (black versus non-black) with priority given to Hispanic, other race, and non-Hispanic White within the black, non-black classification. Analyses were limited to tests occurring in the five years after the initial matching visit and where the complete NP battery was administered.

Covariates

Time-varying covariates included HIV serostatus (for 7 seroconverters), age, alcohol use, recreational drug use, cigarette use, and depression; and for HIV+ participants also included medication use, log10-transformed HIV RNA, and CD4 (per 100 cell increase), CD4 nadir <200, ever had an AIDS diagnosis.. Because income level is captured differently in WIHS (household income) and MACS (individual income), having Medicaid health insurance was used as a surrogate income measure. For men, heavy alcohol use was classified as ≥ 15 drinks/week and for women, ≥ 8 drinks/week. Education was categorized by high school or less, some college, and college degree or more. Illicit drug use since the previous visit was captured for marijuana, cocaine or crack, heroin or other opiates, and other street/recreational drug use. Cigarette smoking was categorized as current, former or never. Depression was defined as Centers of Epidemiology Study-Depression (CES-D)24 scores ≥ 16. Additional adjustments were made for prior test exposure, with counts of ≥ 8 administrations collapsed into one category.

Statistical analysis

We examined differences in sociodemographic, clinical and behavioral characteristics by HIV status and Sex with Χ2 for categorical variables, ANOVA for continuous normally distributed variables (i.e., age, CD4 current, CD4 nadir), and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables that were not normally distributed (i.e., HIV RNA). A series of generalized linear mixed models (random intercept) were conducted to assess interactions between HIV status and Sex on cognitive outcomes. Primary predictors included HIV status, Sex, Time, and all possible two and three-way interactions. Higher order interactions were removed from the models when p>0.05. Of primary interest were the two way interaction between HIV status and Sex and the three-way interaction between HIV status, Sex, and Time. The models controlled for relevant socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics (see above). All models were conducted using the Proc Mixed Procedure in SAS, version 9.3.

Results

Participants included 710 (429 HIV+) women and 710 men (429 HIV+) 20 to 66 years-old, with 67% non-Hispanic African American and 20% Hispanic in each group (Table 1). The four groups were similar in HIV serostatus, years of education age, and black race. Significant HIV status × Sex differences were noted in depressive symptoms, Medicaid, smoking, and alcohol use as well as use of cannabis, crack/cocaine, opiate, and intravenous drug use (p’s<0.001). Although each group had a similar representation of African-Americans (67%), groups differed in other race/ethnicity categories (p<0.001). Among HIV+ groups, women had a higher current mean CD4 count and were more likely to be on HAART (p’s<0.05), but had a lower CD4 pre-HAART nadir compared to men (p=0.03). Table 2 shows average cognitive test performance by HIV Status and Sex at baseline.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics as a function of HIV status and sex at the matched visit, baseline.

| HIV+ | HIV− | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Characteristics | Overall sample n (%) |

Women (n=429) n (%) |

Men (n=429) n (%) |

Women (n=281) n (%) |

Men (n=281) n (%) |

Sex × HIV status |

| Socio-demographic | ||||||

| Race | <0.001 | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 160 (11) | 59 (14) | 41 (10) | 28 (10) | 32 (11) | |

| White, Hispanic | 134 (9) | 44 (10) | 34 (8) | 39 (14) | 17 (6) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 950 (67) | 287 (67) | 287 (67) | 188 (67) | 188 (67) | |

| Black, Hispanic | 42 (3) | 18 (4) | 7 (2) | 13 (5) | 4 (1) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 14 (1) | 7 (2) | - | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Other | 12 (1) | 1 (0) | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | |

| Other Hispanic | 108 (8) | 13 (3) | 56 (13) | 6 (2) | 33 (12) | |

| Education | 0.80 | |||||

| High school or less | 758 (53) | 227 (53) | 227 (53) | 152 (54) | 152 (54) | |

| Some college | 500 (35) | 148 (34) | 148 (34) | 102 (36) | 102 (36) | |

| 4 year degree or more | 162 (11) | 54 (13) | 54 (13) | 27 (10) | 27 (10) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 41.2 (8.1) | 43.1 (7.5) | 40.9 (7.6) | 40.5 (8.7) | 39.6 (8.7) | <0.001 |

| Income‖ | 811 (57) | 202 (47) | 291 (68) | 135 (48) | 183 (65) | <0.001 |

| Has Medicaid | 568 (40) | 251 (59) | 143 (33) | 124 (44) | 50 (18) | <0.001 |

| Behavioral characteristics at matched visit | ||||||

| Elevated depressive symptoms± | 404 (28) | 92 (21) | 163 (38) | 44 (16) | 105 (37) | <0.001 |

| Heavy alcohol use† | 149 (10) | 35 (8) | 32 (7) | 53 (19) | 29 (10) | <0.001 |

| Cannabis use | 399 (28) | 63 (15) | 147 (34) | 64 (23) | 125 (44) | <0.001 |

| Cocaine/crack use | 250 (18) | 6 (1) | 121 (28) | 15 (5) | 108 (38) | <0.001 |

| Opiate use | 83 (6) | - | 32 (7) | 4 (1) | 47 (17) | <0.001 |

| Other drug use | 118 (8) | 2 (0) | 58 (14) | 10 (4) | 48 (17) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | <0.001 | |||||

| Never | 381 (27) | 153 (36) | 96 (22) | 89 (32) | 43 (15) | |

| Former | 370 (26) | 135 (31) | 98 (23) | 80 (28) | 57 (20) | |

| Current | 661 (47) | 140 (33) | 230 (54) | 112 (40) | 179 (64) | |

| Intravenous drug use | 88 (6) | 1 (0) | 50 (12) | 3 (1) | 34 (12) | <0.001 |

| CD4n, mean (SD) | 539.6 (306.3) | 561.9 (314.1) | 516.8 (296.8) | <0.05 | ||

| Therapy since last visit | <0.001 | |||||

| None | 216 (25) | 80 (19) | 136 (32) | |||

| Monotherapy | 4 (0) | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | |||

| Combination | 26 (3) | 2 (0) | 24 (6) | |||

| HAART | 611 (71) | 344 (80) | 267 (62) | |||

| HIV RNA, Mean (SD) | 20639 (105425) | 9868.4 (41837) | 31513 (142686) | 0.23 | ||

| HIV RNA, Median (25, 75%ile) | 48.5 (40, 4925) | <48 (<48, 639) | 239 (<40, 12071) | |||

| CD4 pre-HAART nadir, mean (SD) | 347.9 (284.6) | 319.3 (207.0) | 375.8 (341.7) | <0.01 | ||

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) ≥16 cutoff

MACS <$20000 average annual household income; WIHS; WIHS <=$18000 average annual household income

Men and women’s heavy alcohol use was classified according to the CDC definition. For men, 15 ≥ drinks per week and for women, 8 ≥ drinks/week was classified as heavy alcohol use. http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/faqs.htm#heavyDrinking (page accessed 1/13/2016, Page last reviewed: November 16, 2015, Content source: Division of Population Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

HAART=Highly active antiretroviral therapy

Table 2.

Cognitive test performance (raw mean, standard deviation [SD]) and number of test exposures as a function of HIV status and sex at the baseline matched visit.

| HIV+ | HIV− | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Overall sample Mean (SD) |

Women (n=429) Mean (SD) |

Men (n=429) Mean (SD) |

Women (n=281) Mean (SD) |

Men (n=281) Mean (SD) |

|

| Test Performance | |||||

| TMT† | |||||

| Part A (sec) | 32.2 (13.5) | 34.7 (14.4) | 30.4 (12.4) | 32.3 (13.7) | 30.8 (12.7) |

| Part B (sec) | 80.2 (40.7) | 81.0 (42.3) | 82.1 (43.5) | 74.0 (34.1) | 82.2 (39.3) |

| Grooved Pegboard | |||||

| Dominant (sec) | 77.4 (21.3) | 81.5 (23.5) | 74.3 (17.5) | 78.5 (23.8) | 75.0 (19.4) |

| Non-Dominant (sec) | 87.5 (25.8) | 94.3 (28.2) | 82.6 (21.5) | 89.5 (28.9) | 82.3 (22.1) |

| Symbol Digit (# correct) | 46.9 (11.4) | 47.3 (11.1) | 45.5 (11.0) | 50.0 (11.9) | 45.6 (11.4) |

| Stroop Test | |||||

| Color (sec) | 66.0 (14.9) | 66.4 (15.4) | 67.6 (15.2) | 63.4 (13.3) | 65.5 (14.7) |

| Word (sec) | 50.7 (12.2) | 51.3 (11.7) | 51.0 (13.9) | 49.8 (10.0) | 50.4 (12.2) |

| Interference (sec) | 123.2 (29.8) | 123.7 (27.7) | 125.8 (31.6) | 118.7 (27.0) | 123.2 (32.2) |

| Count of test exposures | |||||

| TMT, Symbol Digit | 3.4 (3.0) | 2.3 (1.6) | 4.4 (3.6) | 2.2 (1.6) | 4.1 (3.3) |

| Grooved Pegboard | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.2 (0.5) | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.2 (0.5) | 1.1 (1.2) |

| Stroop Test | 1.0 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.2) |

TMT=Trail Making Test. Higher values indicate worse performance for TMT, Grooved Pegboard and Stroop. Lower values indicate worse performance on Symbol Digit

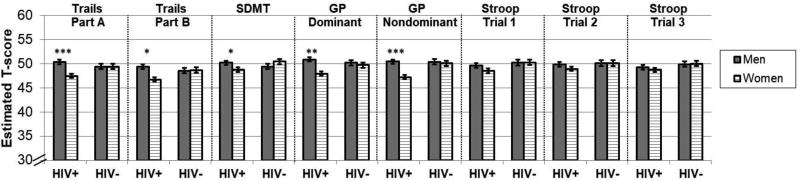

There were no significant three-way interactions between Sex, HIV, and Time interactions, so we examined HIV by Sex interactions on average performance across all time points. For continuous T-scores, the sex difference varied by HIV status on TMTA (p=0.002), TMTB (p=0.006), SDMT (p=0.02), and GP dominant (p=0.02) and nondominant hand (p=0.009)(Figure 1). As shown in the Figure, the T-score adjustment attenuated sex differences in HIV− individuals. A female disadvantage was seen among HIV+ individuals, but not HIV− individuals (p’s>0.19), on TMTA (B[unstandardized beta weight]=−2.92, SE[standard error]=0.63, p<0.0001), TMTB (B=−2.65, SE=0.64, p=0.01), SDMT (B=−1.42, SE=0.63, p=0.02), GP dominant (B=−2.23, SE=0.72, p=0.002), and GP nondominant hand (B=−3.17, SE=0.72, p<0.0001). For categorical T-scores, the sex difference varied by HIV status on the TMTA (p=0.003) and GP nondominant hand (p=0.007). Specifically, HIV+ women were more likely to score in the impaired range compared to HIV+ men on both TMTA (OR[odds ratio]=2.54, p=0.0006) and GP non-dominant hand (OR=5.12, p<0.0001), but no sex differences were observed in HIV− participants.

Figure 1.

Average cognitive test performance a function of HIV status and sex at the matched visit. SDMT=Symbol Digit; GP=Grooved pegboard. For all outcomes, lower values=worse performance. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

In subanalyses in HIV+ individuals only, significant sex differences persisted on continuous measures of TMTA, TMTB, SDMT, and GP dominant and nondominant hand, after controlling for HIV-related clinical characteristics (current CD4 count, CD4 nadir <200, ever had an AIDS diagnosis, viral load, and medication use)(p’s<0.05). On categorical measures, HIV+ women showed a higher odds of impairment compared with HIV+ men on TMTA (OR=2.27, p=0.015) and GP non-dominant hand (OR=7.93, p<0.001).

Discussion

Cognitive function was examined in a large sample women from the WIHS (n=710) and men (n=710) from the MACS - the two longest-running longitudinal studies of HIV disease progression in the U.S. We found evidence to support the hypothesis that HIV+ women compared to HIV+ men show cognitive vulnerabilities in aspects of psychomotor speed, attention, processing speed, and motor skills. To determine whether those differences were clinically significant, we also examined sex differences in the odds of scoring in the impaired range. We found that compared to HIV+ men, HIV+ women had a higher odds of scoring in the impaired range in psychomotor speed and attention (TMTA) and motor skills (Grooved Pegboard).

For comparison with previous studies of sex differences in HIV+ individuals alone (i.e., no controls), we note that HIV+ women in the current study performed worse than HIV+ men on four of five tests, including the TMTA, TMTB, SDMT, and GP but not the Stroop. Overall, those findings are in agreement with those from a study of 149 HAART-naïve HIV+ adults and 58 HIV− controls from Nigeria.9 Compared to HIV+ men, HIV+ women were more impaired in speed of processing, as well as verbal fluency, learning and memory, and global impairment. In that study, sex differences were influenced by women’s higher plasma levels of HIV and higher circulating levels of monocyte-driven inflammatory markers (sCD14, sCD163). In the current study, the majority of HIV participants were treated, and the sex differences remained after controlling for HIV RNA and CD4 counts, which did not differ by sex. Current findings are also in general agreement with findings from 436 HIV+ individuals (80% male) enrolled in CHARTER (CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research cohort). Compared to HIV+ men, HIV+ women showed a 76% increased risk of decline in a global estimate of cognitive function over a 35-month follow-up3. We found that the lower performance of HIV+ women compared to HIV+ men did not worsen over a 30-month follow-up.

Previous studies demonstrate some of the factors that may contribute to these findings of a female disadvantage across cognitive measures. We controlled for depression in this study, but other mental health factors that are not available in the MACS have been shown to negatively influence cognitive function in HIV+ women, including stress and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)21, 22, 25. Previous studies show that these psychological factors affected cognitive function in HIV+ women more than HIV− women21, 22. Although we controlled for recent substance use in this study, a more thorough examination of substance use is warranted. In the WIHS cocaine and heroin use had a greater influence on cognition in HIV+ women compared to HIV− women, an effect that was associated with alterations in prefrontal function. Recent work shows an interactive effect of sex and HIV on cognition among substance-dependent individuals, with HIV+ women showing poorer cognitive function compared to other groups26–28. Lastly, these effects may also reflect the influence of menopause29 and sexual dimorphism in immune function30, pathogenesis31, and/or antiretroviral pharmacokinetics32. These possibilities will be addressed in ongoing studies of WIHS and MACS. Overall, our results show that cognitive findings from HIV+ men cannot be uncritically generalized to HIV+ women and that instead sex should be considered in studies of the pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and treatment of cognitive dysfunction in HIV.

Limitations of this study include no comparison of sex differences in verbal learning and memory because different measures were used (RAVLT in MACS; HVLT in WIHS) and the magnitude of sex differences may differ between these tests given differences in test construction (e.g., ability to semantically cluster on HVLT but not RAVLT). Non-Hispanic Blacks comprised 67% of the total sample here compared to 40% of individuals living with HIV in the U.S.4 so results may not generalize to the broader population of HIV+ individuals. Given differences in definitions of certain covariates between the WIHS and MACS (i.e., income, education, substance use), we determined covariates that could be applied across studies. For strengths, our study has the largest sample size to date of HIV+ men and women and controls. We had a longitudinal design with a follow-up time of 2.45 years with an average of 2.6 assessments per participant. Continued follow-up of this cohort is needed to examine these sex differences with advancing age.

Acknowledgments

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) and the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). WIHS (Principal Investigators): UAB-MS WIHS (Michael Saag, Mirjam-Colette Kempf, and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-AI-103401; Atlanta WIHS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun and Gina Wingood), U01-AI-103408; Bronx WIHS (Kathryn Anastos), U01-AI-035004; Brooklyn WIHS (Howard Minkoff and Deborah Gustafson), U01-AI-031834; Chicago WIHS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-AI-034993; Metropolitan Washington WIHS (Mary Young and Seble Kassaye), U01-AI-034994; Miami WIHS (Margaret Fischl and Lisa Metsch), U01-AI-103397; UNC WIHS (Adaora Adimora), U01-AI-103390; Connie Wofsy Women’s HIV Study, Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt, Bradley Aouizerat, and Phyllis Tien), U01-AI-034989; WIHS Data Management and Analysis Center (Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Golub), U01-AI-042590; Southern California WIHS (Joel Milam), U01-HD-032632 (WIHS I – WIHS IV). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects is also provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. WIHS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA) and UL1-TR000454 (Atlanta CTSA).

Data in this manuscript were also collected by the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) with centers at Baltimore (U01-AI35042): The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health: Joseph B. Margolick (PI), Jay Bream, Todd Brown, Barbara Crain, Adrian Dobs, Richard Elion, Richard Elion, Michelle Estrella, Lisette Johnson-Hill, Sean Leng, Anne Monroe, Cynthia Munro, Michael W. Plankey, Wendy Post, Ned Sacktor, Jennifer Schrack, Chloe Thio; Chicago (U01-AI35039): Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and Cook County Bureau of Health Services: Steven M. Wolinsky (PI), John P. Phair, Sheila Badri, Dana Gabuzda, Frank J. Palella, Jr., Sudhir Penugonda, Susheel Reddy, Matthew Stephens, Linda Teplin; Los Angeles (U01-AI35040): University of California, UCLA Schools of Public Health and Medicine: Roger Detels (PI), Otoniel Martínez-Maza (Co-P I), Aaron Aronow, Peter Anton, Robert Bolan, Elizabeth Breen, Anthony Butch, Shehnaz Hussain, Beth Jamieson, Eric N. Miller, John Oishi, Harry Vinters, Dorothy Wiley, Mallory Witt, Otto Yang, Stephen Young, Zuo Feng Zhang; Pittsburgh (U01-AI35041): University of Pittsburgh, Graduate School of Public Health: Charles R. Rinaldo (PI), Lawrence A. Kingsley (Co-PI), James T. Becker, Phalguni Gupta, Kenneth Ho, Susan Koletar, Jeremy J. Martinson, John W. Mellors, Anthony J. Silvestre, Ronald D. Stall; Data Coordinating Center (UM1-AI35043): The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health: Lisa P. Jacobson (PI), Gypsyamber D’Souza (Co-PI), Alison, Abraham, Keri Althoff, Jennifer Deal, Priya Duggal, Sabina Haberlen, Alvaro Muoz, Derek Ng, Janet Schollenberger, Eric C. Seaberg, Sol Su, Pamela Surkan. Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: Robin E. Huebner; National Cancer Institute: Geraldina Dominguez. The MACS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects was also provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and the Office of Research on Women’s Health. MACS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR001079 (JHU ICTR) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Johns Hopkins ICTR, or NCATS. The MACS website is located at http://aidscohortstudy.org/.

Sources of Funding: Pauline Maki has received speaking honoraria from Mylan. Victor Valcour has received consulting honoraria from ViiV Healthcare and Merck, as well as honoraria for educational activities from the International AIDS Society.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: For the remaining authors none were declared.

References

- 1.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacktor N, Skolasky RL, Seaberg E, et al. Prevalence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Neurology. 2016;86:334–340. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Jr, Deutsch R, et al. Neurocognitive change in the era of HIV combination antiretroviral therapy: the longitudinal CHARTER study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:473–480. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevention H. Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data [Google Scholar]

- 5.Women U. [Accessed December 7];Facts and Figures: HIV and AIDS [online] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maki PM, Rubin LH, Valcour V, et al. Cognitive function in women with HIV: findings from the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Neurology. 2015;84:231–240. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin LH, Maki PM, Springer G, et al. Cognitive trajectories over 4 years among HIV-infected women with optimal viral suppression. Neurology. 2017 doi: 10.1212/WNL. 0000000000004491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maki PM, Martin-Thormeyer E. HIV, cognition and women. Neuropsychol Rev. 2009;19:204–214. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9093-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royal W, 3rd, Cherner M, Burdo TH, et al. Associations between Cognition, Gender and Monocyte Activation among HIV Infected Individuals in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson K, Fiscus S, Wilkins J, van der Horst C, Hall C. Viral Load and Neuropsychological Functioning in HIV Seropositive Individuals:A Preliminary Descriptive Study. J NeuroAIDS. 1996;1:7–15. doi: 10.1300/j128v01n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behrman-Lay AM, Paul RH, Heaps-Woodruff J, Baker LM, Usher C, Ances BM. Human immunodeficiency virus has similar effects on brain volumetrics and cognition in males and females. J Neurovirol. 2016;22:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0373-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Failde-Garrido JM, Alvarez MR, Simon-Lopez MA. Neuropsychological impairment and gender differences in HIV-1 infection. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2008;62:494–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiely KM, Butterworth P, Watson N, Wooden M. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test: Normative data from a large nationally representative sample of Australians. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;29:767–775. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruff RM, Parker SB. Gender- and age-specific changes in motor speed and eye-hand coordination in adults: normative values for the Finger Tapping and Grooved Pegboard Tests. Percept Mot Skills. 1993;76:1219–1230. doi: 10.2466/pms.1993.76.3c.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt SL, Oliveira RM, Rocha FR, Abreu-Villaca Y. Influences of handedness and gender on the grooved pegboard test. Brain Cogn. 2000;44:445–454. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1999.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Detels R, Jacobson L, Margolick J, et al. The multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, 1983 to. Public Health. 2012;126:196–198. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The Women's Interagency HIV Study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker JT, Kingsley LA, Molsberry S, et al. Cohort Profile: Recruitment cohorts in the neuropsychological substudy of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1506–1516. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR., Jr The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:310–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/126.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin LH, Sundermann EE, Cook JA, et al. Investigation of menopausal stage and symptoms on cognition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Menopause. 2014;21 doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin LH, Pyra M, Cook JA, et al. Post-traumatic stress is associated with verbal learning, memory, and psychomotor speed in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women. J Neurovirol. 2016;22:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0380-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin LH, Cook JA, Weber KM, et al. The association of perceived stress and verbal memory is greater in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected women. J Neurovirol. 2015;21:422–432. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0331-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crystal HA, Weedon J, Holman S, et al. Associations of cardiovascular variables and HAART with cognition in middle-aged HIV-infected and uninfected women. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:469–476. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0052-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin LH, Wu M, Sundermann EE, et al. Elevated stress is associated with prefrontal cortex dysfunction during a verbal memory task in women with HIV. J Neurovirol. 2016;22:840–851. doi: 10.1007/s13365-016-0446-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keutmann MK, Gonzalez R, Maki PM, Rubin LH, Vassileva J, Martin EM. Sex differences in HIV effects on visual memory among substance-dependent individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2017;39:574–586. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2016.1250869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin E, Gonzalez R, Vassileva J, Maki P. HIV+ men and women show different performance patterns on procedural learning tasks. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33:112–120. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.493150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin E, Gonzalez R, Vassileva J, Maki PM, Bechara A, Brand M. Sex and HIV serostatus differences in decision making under risk among substance-dependent individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2016;38:404–415. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2015.1119806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin LH, Sundermann EE, Cook JA, et al. Investigation of menopausal stage and symptoms on cognition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Menopause. 2014;21:997–1006. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meier A, Chang JJ, Chan ES, et al. Sex differences in the Toll-like receptor-mediated response of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to HIV-1. Nat Med. 2009;15:955–959. doi: 10.1038/nm.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Addo MM, Altfeld M. Sex-based differences in HIV type 1 pathogenesis. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014;209(Suppl 3):S86–92. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ofotokun I, Chuck SK, Hitti JE. Antiretroviral pharmacokinetic profile: a review of sex differences. Gend Med. 2007;4:106–119. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]