Abstract

Objective

School attendance prevents HIV and HSV-2 in adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) but the mechanisms to explain this relationship remain unclear. Our study assesses the extent to which characteristics of sex partners, partner age and number, mediate the relationship between attendance and risk of infection in AGYW in South Africa.

Design

We use longitudinal data from the HPTN 068 randomized controlled trial in rural South Africa where girls were enrolled in early adolescence and followed in the main trial for over three years. We examined older partners and number of partners as possible mediators.

Methods

We use the parametric g-formula to estimate 4-year risk differences for the effect of school attendance on cumulative incidence of HIV/HSV-2 overall and the controlled direct effect (CDE) for mediation. We examined mediation separately and jointly for the mediators of interest.

Results

We found that young women with high attendance in school had a lower cumulative incidence of HIV compared to those with low attendance (risk difference=-1.6%). Partner age difference (CDE=-1.2%) and number of partners (CDE=-0.4%) mediated a large portion of this effect. In fact, when we accounted for the mediators jointly, the effect of schooling on HIV was almost removed showing full mediation (CDE= −0.3%). The same patterns were observed for the relationship between school attendance and cumulative incidence of HSV-2 infection.

Conclusion

Increasing school attendance reduces risk of acquiring HIV and HSV-2. Our results indicate the importance of school attendance in reducing partner number and partner age difference in this relationship.

Keywords: South Africa, Adolescent girls and young women, HIV, HSV-2, Education, Mediation

Introduction

Young South African women have an extremely high burden of HIV and HSV-2. The prevalence of HIV in adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) aged 15-26 years is16% [1] and the prevalence of HSV-2 is 29%.[2] Most interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in AGYW have focused on modifying sexual risk behaviors and have had limited success.[3–5] However, there is now a large body of evidence showing that attending school and staying in school protect against HIV and HSV-2 infection.[6–10] Our analysis from South Africa showed that low school attendance and school dropout were associated with over twice the risk of both incident HIV and incident HSV-2.[11] Yet, the mechanisms underlying the relationship between attending school and STIs are not understood.

HIV and HSV-2 are most commonly transmitted sexually. Therefore, for schooling to affect acquisition of HIV and HSV-2, schooling must influence behavioral factors that can affect likelihood of transmission such as exposure to infection through a sexual partner.[12] Researchers have hypothesized that the effect of education on HIV risk, including both educational attainment and school attendance, may be a result of changes in social networks, self-efficacy, socioeconomic status or sexual risk behaviors. However, there is limited empirical evidence investigating pathways between education and HIV or HSV-2 infection.[3] Due to associations between school attendance and both partner age difference and partner number and theories on the importance of sexual networks in individual acquisition of HIV, we chose to examine the mediating effect of characteristics of sex partners in the association between school attendance and HIV risk reduction.[7,13–16]

Our hypothesis is based on the idea that the structure of partnership networks is important in influencing young women’s HIV risk. [17,18] Social control theory and the routine/time use perspective state that behavior (in this case sexual behavior) can be limited by social forces and that activities that involve structured, supervised time will limit adolescent deviant or risky behavior.[19–24] We theorized that the supervised, structured environment of school would lead to fewer partners as AGYW are occupied, and to younger partners (who are less likely to have HIV), as students spend more time socializing with individuals in their peer group. Our previous study from South Africa showed the girls who attend school have partners closer in age to themselves and fewer partners.[16] Therefore, it is possible that AGYW in school are less likely to become infected with HIV and HSV-2 because school attendance shapes their sexual network by influencing the types of partners they choose. No studies have directly examined if sex partners mediate the relationship between school attendance and HIV acquisition.

Given that attending school is one of the few factors that is strongly preventative against HIV and HSV-2 infection for adolescent girls, understanding the pathways through which school reduces risk is important to improve our prevention response. Our study explores if partner age difference or number of partners mediate the relationships between school attendance and incident HIV and HSV-2 infection among AGYW.

Methods

Study population

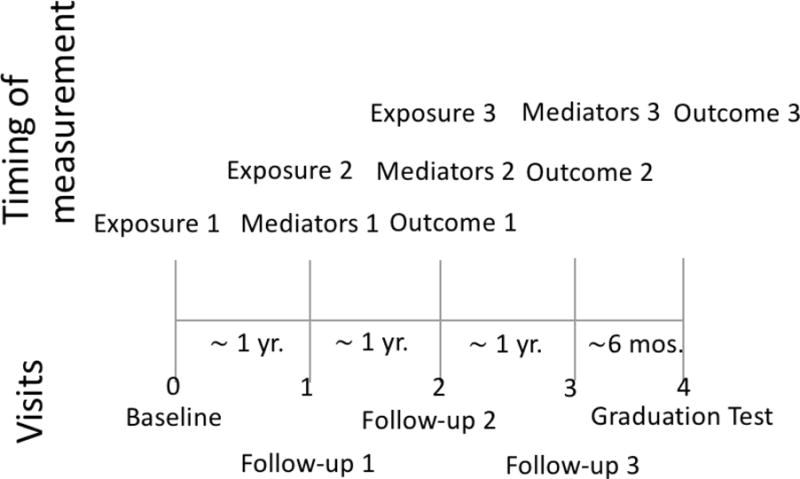

We used data from the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 068 study, a phase III randomized trial to determine whether providing cash transfers, conditional on school attendance, reduced risk of HIV acquisition in young women.[25,26] Details of the behavioral questionnaire and laboratory data are available in the parent publication of the trial.[26] The study included young women living in 28 villages within the MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit (Agincourt) in rural Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. The study enrolled 2,533 young women ages 13-20 in high school grades 8, 9, 10 or 11. Young women who were pregnant or married at enrollment or had no parent/guardian in the household were excluded. To assess incident HIV infection and mediation, we only included young women who had at least two follow-up visits and were HIV negative at enrollment and the first follow-up visit (Figure 1). We did so to ensure that school attendance was measured before the potential mediators and the mediators were measured before the outcome. For incident HSV-2 infection, we further excluded prevalent cases of HSV-2 at enrollment or first follow-up.

Figure 1.

Timing and measurement of exposure, outcome and mediators in a participant with all possible visits

Young women were seen annually from baseline until study completion or expected graduation from high school. Each annual study visit included an Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) with the young woman and HIV and HSV-2 testing for those who were negative at the previous visit. Up to four assessments of the young women were conducted between 2011 and 2015; at baseline and roughly every 12 months thereafter. Young women were in different grades at enrollment and could have had fewer than four visits if they were expected to graduate before the end of the study period. An additional HIV and HSV-2 test was conducted for some girls around the time of expected graduation from high school or when the study was completed to capture more person time in the study if eligibility was met (termed the graduation test). This test was typically around 6 months after the previous annual visit.

Exposure, outcome and mediator ascertainment

The exposure of school attendance was constructed using school attendance registers collected directly from high schools. School attendance was defined as the average percentage of days attended in the months of February, May and August between surveys, as these months were most representative of normal attendance due to absence of holidays or exams. School attendance was dichotomized as high (≥80% of school days) versus low (<80% of school days) attendance as per the original cash transfer study.[26]

The mediator of “having an older partner” was defined as having had at least one sexual or nonsexual partner five or more years older at each follow-up visit. Partners with whom there was no reported sexual relationship were included to account for potential misreporting about sexual behaviors. The mediator of “number of sexual partners” was defined as having zero, one or >1 sex partners in the last 12 months at each visit. The outcomes of incident HIV and HSV-2 infection were defined as new cases after the first follow-up visit, as described by testing procedures in the main paper.[26] We include incident cases from the second visit onward to ensure that all infections occurred after the mediator and exposure ascertainment.

Statistical analysis

We used the potential outcomes framework to define the total effect as the risk difference comparing the 4-year cumulative incidence of HIV or HSV-2 had all young women had high attendance to the 4-year cumulative incidence of HIV or HSV-2 had all young women had low attendance. Likewise, the controlled direct effect (CDE) was defined as the risk difference (high versus low attendance) that would have been observed if attendance was prevented from affecting each of the mediators.[27,28] Specifically, our study explored if partner age difference or number of partners were mediators in the relationship between school attendance and incident HIV/HSV-2 infection by estimating the CDE of attendance while intervening to fix (i.e. control for) the mediators.[29–31] In our study, the CDE can be interpreted as the effect of school attendance on HIV and HSV-2 that occurs through mechanisms other than by reducing partner age and number. We chose to estimate the CDE for mediation rather than the natural direct or indirect effect because it does not require as many assumptions including the assumption that there is no mediator-outcome confounder that is affected by the exposure, which we cannot assume in this analysis.[32] Additionally, we examined the CDE under several different scenarios or ‘interventions” including: 1) prevent young women from having any sexual partners and older sexual or nonsexual partners; 2) Set women to have 1 sexual partner and prevent women from having any older sexual or nonsexual partners; 3) Reduce the number of women with an older partner by 50%; 4) Set young women to have fewer partners (those with >=2 have 1 partner and those with 1 have 0 partners); and 5) Set young women to have fewer partners and reduced the number of women with an older partner by 50%

We estimated total and controlled direct effects using the parametric g-formula, a generalization of standardization that allows us to account for time-varying confounding and accommodate interactions between school attendance and the mediators.[27,31,32] Details on using the parametric g-formula for mediation analysis have been described previously.[27,33–37] Briefly, we created a simulated version of our dataset with no confounding in which we set variables to mimic interventions (see technical appendix for more detail) on school attendance and each mediator.

Confounders were selected using a directed acyclic graph (DAG) for the relationship between school attendance and HIV, and for the relationship between school attendance and HSV-2. We included the exposure-outcome confounders of time, age at baseline, intervention assignment at baseline, socioeconomic status (SES) at baseline (defined using quartiles of household assets), time varying orphan status, time varying alcohol use, time-varying children’s depression inventory score[38,39] and time-varying revised children’s manifest anxiety score.[40] In addition, we included HSV-2 status in the model for the outcome of HIV. We also included the mediator-outcome confounders of depression, anxiety and alcohol use in all models (all time-varying). An interaction term between the mediators partner age difference and partner number was also included in the model but we were unable to include an interaction term between exposure and mediators due to sparse data (see technical appendix). We examined SES defined using both household assets and parental educational attainment but ultimately chose assets because results were similar and assets had less missing data.

Risk of HIV and HSV-2 for each exposure pattern (the combination of interventions on exposure and mediators) was estimated using the complement of the Kaplan Meir estimator extended to account for time-varying exposures.[33] We compared risk of HIV and HSV-2 at the end of the study period (4 years to account for the extra graduation test) under each exposure plan using risk differences and risk ratios. 95% confidence intervals were computed using the standard errors from 200 nonparametric bootstrap resamples. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 2,086 young women who were HIV-negative at baseline and first follow-up, and had at least two follow-up visits following baseline, were included in our HIV cohort. For the HSV-2 cohort, we further excluded prevalent cases of HSV-2 at baseline and those who were missing HSV-2 status for a total of 1,963 young women with 4,192 visits over the study period. In the observed data, there were 74 incident HIV infections and 117 incident HSV-2 infections from follow-up visit two to the end of the study period. Of the 4,450 visits with school attendance data, girls who were HIV-negative at baseline had high attendance during 95.2% of visits (N=4,234). At baseline in the observed data, 5.1% (N=105) had a partner five or more years older, 78.9% had zero partners (N=1,626) and 16.7% (N=344) had one partner in the last 12 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of young women aged 13 to 20 without prevalent HIV infection and at least three follow-up visits in Agincourt, South Africa from March 2011 to December 2012 (N=2,086)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Young women’s age at baseline (year) | |

| Age 13-14 | 717 (34.4) |

| Age 15-16 | 913 (43.8) |

| Age 17-18 | 384 (18.4) |

| Age 18-20 | 72 (3.5) |

| Household wealth | |

| Low | 540 (25.9) |

| Middle to Low | 566 (27.2) |

| Middle | 489 (23.5) |

| High | 488 (23.4) |

| CCT randomization arm | 1091 (52.3) |

| Partner 5 or more years older | 105 (5.1) |

| Ever pregnant or had a child | 150 (7.3) |

| Prevalent HSV-2 infection | 73 (3.5) |

| Any alcohol use | 173 (8.3) |

| Double or single orphan | 1314 (30.2) |

| Children’s depression inventory score >=7 | 369 (17.7) |

| Revised children’s manifest anxiety score >=7 | 570 (27.3) |

| Partner number | |

| 0 | 1626 (78.9) |

| 1 | 344 (16.7) |

| >=2 | 92 (4.5) |

Missing data in observed: age 0; SES 3; age difference 5, pregnant 23; HSV-2 status 2; alcohol 3; orphan 98; depression 0; anxiety 0; partner number N=24;

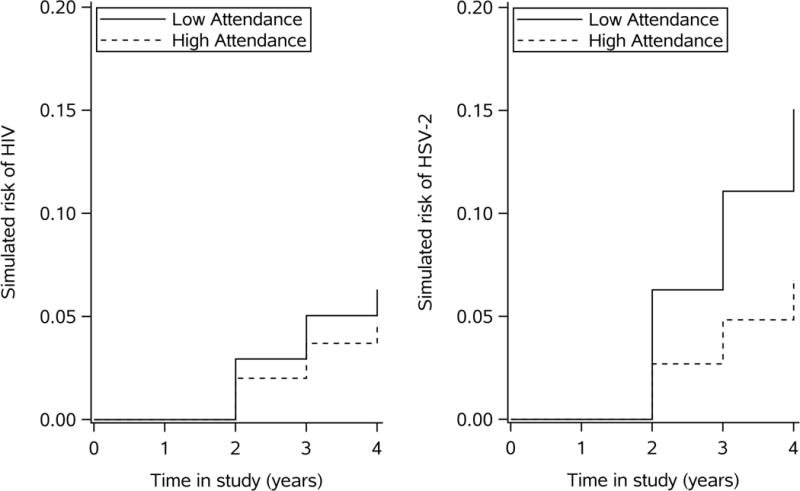

The risk of HIV at four years of follow-up time would be 6.3% had all young women had low school attendance and 4.7% if all young women had high attendance over the entire study period (Figure 2; Table 2). Cumulative incidence of HIV and HSV-2 estimated under no intervention on exposure or mediators (the “natural course”) was similar to the cumulative incidence of the outcomes in the observed data (HIV 4.9%; HSV-2 8.1%; Appendix Figure 1).Table 2 shows the total effect of school attendance compared to the controlled direct effect of attendance when young women also do not have an older partner, when they have one partner and zero partners. The estimated risk difference at four years for the effect of high versus low school attendance on HIV was −1.6% (95 % CI: −2.3%, −1.0%). The risk difference of −1.6% represents the total effect of school attendance on HIV operating through all pathways including partner age and number. When we removed the effect of attendance on partner age by setting all girls to have a younger partner, the risk difference for the effect of school attendance on HIV was −1.2% (95 % CI: −1.8%, −0.7%). When we removed the effect of school attendance on partner number by setting young women have 0 partners, the risk difference for the effect of school attendance on HIV was −0.4% (95% CI: −0.9%, 0.1%). When we set the number of partners to 1 partner (even those with 0 partners), the risk difference at four years was −0.8% (95% CI −1.6%, −0.1%).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of HIV and HSV-2 by time since study enrollment and attendance in a Monte Carlo sample of 10,000, accounting for confounding*

*Confounders included: baseline age, time of survey, visit number, baseline intervention arm, baseline SES, depression, anxiety, alcohol use, baseline orphan status; HSV-2 was also included for the HIV outcome

Table 2.

Controlled direct effect (CDE) of school attendance on incident HIV and HSV-2 by different levels of the mediators partner number and partner age difference

| HIV | HSV-2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Risk (%) | RD % (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | Risk (%) | RD %(95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | |

| Total effect | ||||||

| High attendance | 4.7 | −1.6 (−2.3, −1.0) | 0.74 (0.66,0.83) | 6.7 | −8.3 (−9.1, −7.5) | 0.45 (0.41, 0.49) |

| Low attendance | 6.3 | 0 | 1.0 | 15.1 | 0 | 1 |

| CDE No older partners | ||||||

| High attendance | 4.6 | −1.2 (−1.8, −0.7) | 0.79 (0.70, 0.88) | 6.3 | −6.2 (−7.1, −5.4) | 0.51 (0.46, 0.55) |

| Low attendance | 5.8 | 0 | 1 | 12.6 | 0 | 1 |

| CDE No sexual partners | ||||||

| High attendance | 3.2 | −0.4 (−0.9, 0.1) | 0.89 (0.77, 1.03) | 5.8 | −6.9 (−7.8, −6.1) | 0.46 (0.41, 0.50) |

| Low attendance | 3.6 | 0 | 1 | 12.8 | 0 | 1 |

| CDE One sexual partner | ||||||

| High attendance | 7.0 | −0.8 (−1.6, −0.1) | 0.89 (0.81, 0.98) | 8.2 | −7.6 (−8.5, −6.7) | 0.52 (0.48,0.56) |

| Low attendance | 7.8 | 0 | 1 | 15.8 | 0 | 1 |

RD: Risk Difference, RR: Risk Ratio, CI: Confidence Interval

The risk of HSV-2 at four years was 15.1% had all young women had low attendance and 6.7% if all young women had high attendance over the entire study period (Figure 2. Table 2). The estimated risk difference for the total effect of high versus low school attendance on HSV-2 was higher than HIV at −8.3% (95 % CI: −9.1%, −7.5%) (Table 2). When we removed the effect of attendance on partner age, the risk difference at four years was −6.2% (95 % CI: −7.1%, −5.4%) When all young women had 0 partners, the risk difference was −6.9% (95% CI: −7.8%, −6.1%). When we set the number of partners to one, the risk difference at four years was −7.6% (95% CI: −8.5%, −6.7%).

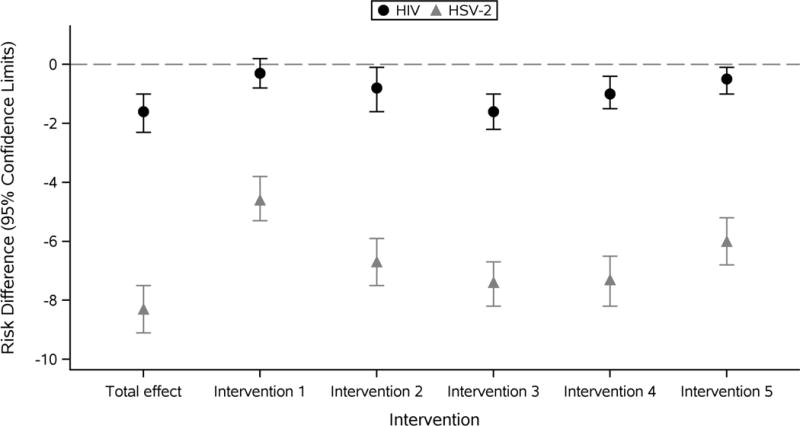

Figure 3 shows the effect of school attendance on HIV and HSV-2 under 5 potential scenarios where we have jointly removed the effect of school attendance on both partner age difference and partner number. For incident HIV, the risk difference for the CDE of school attendance was attenuated from the total effect in all scenarios. Under intervention 1, the risk difference was almost zero (RD −0.3%; 95% CI: −0.8%, 0.2%). Even under intervention 5 where we do not completely set behaviors, the effect of school attendance on HIV acquisition was almost removed (RD −0.5%; 95% CI: −1.0%, −0.1%). For incident HSV-2 infection, the risk difference for the effect of school attendance on HSV-2 was again attenuated from the total effect in all scenarios, though the effect was never completely removed. The risk difference for the effect of school attendance on HSV-2 was closest to the null under intervention 1 when we intervened to set all young women to have younger partners and zero partners (RD −4.6%; 95% CI −5.3%, −3.8%).

Figure 3.

Controlled direct effect of school attendance on incident HIV and HSV-2 with various interventions on the mediators partner age difference and partner number*

*Intervention 1: Prevent young women from having any sexual partners and older sexual or nonsexual partners; Intervention 2: Set women to have 1 sexual partner and prevent women from having any older sexual or nonsexual partners; Intervention 3: Reduce the number of women with an older partner by 50%; Intervention 4: Set young women to have fewer partners (those with >=2 have 1 partner and those with 1 have 0 partners); Intervention 5: Set young women to have fewer partners and reduced the number of women with an older partner by 50%

Discussion

In this cohort of AGYW in rural South Africa, we found that partner age and partner number mediated the relationship between school attendance and HIV and HSV-2 acquisition. School attendance was associated with risk of both incident HIV and HSV-2. The effect of school attendance on incident infection was nearly removed when also intervening on the number of older partners and partner number, suggesting that a large proportion of protective effect of school attendance on HIV acquisition in this cohort is the result of sexual partner characteristics. In fact, the effect of school attendance on HIV, although primarily driven by partner number, is null after accounting for partner selection.

Our results are compatible with the theory that young women who attend more school are at lower risk of HIV and HSV-2 infection because of their sexual network structure.[7,16] Previous studies have reported a lower prevalence of HIV and HSV-2 in young men and women attending school and associations between school attendance, partner age difference and number of partners.[7,16,41] We found that school attendance was associated with a reduced risk of HIV and HSV-2 and we add to the literature by formally assessing mediation to illustrate that partner age difference and partner number are mediators of these relationships. While it may be impossible to do things like “prevent older partners” explicitly, these results are important because they show illustratively that school attendance naturally prevents HIV and HSV-2 by providing periods of structure and supervision in young adults’ lives which reduce opportunities for sexual activity and promote safer networks.[3,16,19]

The results for mediation of the effect of school attendance on HIV differed slightly from the results for HSV-2. Partner selection can almost entirely explain the relationship between school attendance and HIV. However, removing the effect of school attendance on partner age and partner number removed only some of the effect of school attendance on HSV-2. These results indicate that there are likely other mechanisms that are additional mediators of the relationship between school attendance and HSV-2. For example, because HSV-2 is more transmissible than HIV, condom use to reduce efficiency of transmission per contact might be an important determinant of infection that is linked to schooling.[42,43] It is also possible, given the higher prevalence of HSV-2 in general, that younger men are more likely to have HSV-2 making network patterns different than HIV.[44]

It should be noted that information on sexual behaviors was self-reported and there may have been some misreporting in the study despite the use of ACASI to minimize reporting bias.[25] Misreporting about sexual behaviors is apparent in the remaining risk of HIV/HSV-2 infection after we fix all young women to have zero partners (we would expect that girls wouldn’t get infected if they don’t have sex). We do show that even if young women had one partner overall or if they had 50% fewer older partners and fewer partners overall, the effect of school attendance on incidence of infection would still be much smaller. A sensitivity analysis was done setting all HIV cases in girls with 0 partners to have 1 partner and to have 2 partners (Appendix table 2 and table 3) and we found similar results. However, the total effect and the mediation by partner number were larger, and mediation by partner age difference was not as pronounced. It is likely that girls who misreport sexual activity would also misreport partner age as they may not have included the ages of any partners on the survey. Moreover, when we assumed that girls who were HIV positive and had 0 partners also had older partners, we found again similar results and mediation by partner age difference (Appendix table 3).

In addition, the assumption of no unmeasured confounding is a strong assumption that is impossible to assess in the data.[31] It is possible that there are confounders we did not measure or include in our models. However, we did explore measured confounding by examining the effect of adding and removing different variables to our models. We also used the controlled direct effect instead of the indirect and natural direct effects for mediation to avoid the assumption of no mediator-outcome confounders affect by prior exposure. Second, the parametric g-formula assumes that the parametric models used to predict our variables are correctly specified. This assumption is not testable but covariate distributions and cumulative incidence functions in the predicted natural course were a close fit to the observed data, suggesting that the models were adequately specified.[33] Lastly, one benefit of using causal inference methods for mediation is to include exposure-mediator interactions; however, we were unable to do so in our analysis due to sparse data (see technical appendix). Therefore, our analysis assumes the effects of exposure and mediators are multiplicative.

It should be noted that the data are from a randomized controlled trial where all young women were already enrolled in school at study enrollment. Previous analyses of the data have shown potential selection bias where young women in the study may have been more likely to attend school than the underlying population and a Hawthorne effect where young women in the trial were less likely to drop out of school due to trial participation.[45] However, we would expect the relationship between schooling and HIV/HSV-2 to remain similar.

We found that school attendance was associated with both incident HIV and HSV-2 infection and are the first to show that partner age difference and number of partners mediate the relationships between school attendance and incident HIV and HSV-2 infection. These findings are significant as education has been one of the factors that is most consistently associated with preventing HIV in AGYW and we provide a better understanding about how that relationship operates.[3,8,46,47] Our study shows illustratively that school attendance naturally reduces the risk HIV and HSV-2 acquisition among AGYW by providing periods of structure and supervision in young adults’ lives which encourage younger and fewer partners. Changes in these partnership factors will ultimately reduce opportunities for sexual activity and promote safer networks where girls are not exposed to infection. Interventions to prevent infections in young women should focus on keeping girls in school and creating other environments like school that constructively occupy time and provide a safe space where young women can associate with their peers. Alternatively, given the importance of partner age and number to adolescent HIV acquisition, efforts to provide biomedical interventions like PrEP, to girls who are sexually active, out of school or who have older partners may help to prevent new infections. Schooling is one of the strong preventative interventions for HIV and HSV-2 among AGYW. Evidence that this effect operates through partner selection should encourage interventions to keep girls in school and the development of interventions that emulate this supervised and structured environment, potentially changing sexual networks and norms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the HPTN 068 study team and all trial participants. The MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit and Agincourt Health and Socio-Demographic Surveillance System have been supported by the University of the Witwatersrand, the Medical Research Council, South Africa, and the Wellcome Trust, UK (grants 058893/Z/99/A; 069683/Z/02/Z; 085477/Z/08/Z; 085477/B/08/Z). AP, JKE, AEA, KBR, WCM and CTH contributed to the conception, design of the analysis and review of the writing. The remaining authors were involved in data acquisition, data collection, study management and design of the original parent study. Additionally, JKE and JPH contributed to the analysis of data.

Financial Support: This study was funded by T32 5T32AI007001, R01 MH110186 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and by Award Numbers UM1 AI068619 (HPTN Leadership and Operations Center), UM1AI068617 (HPTN Statistical and Data Management Center), and UM1AI068613 (HPTN Laboratory Center) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by NIMH R01 (R01MH087118) and the Carolina Population Center and its NIH Center grant (P2C HD050924). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Meetings where data were presented: Planning to submit to AIDS 2018 conference in Amsterdam July 23-27

Declaration of Interests: We declare no competing interests.

List of supplementary digital content:

Web Appendix: Technical details (word doc)

References

- 1.Gómez-Olivé FX, Angotti N, Houle B, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Kabudula C, Menken J, et al. Prevalence of HIV among those 15 and older in rural South Africa. AIDS Care. 2013;25:1122–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.750710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jewkes R, Wood K, Duvvury N. “I woke up after i joined Stepping Stones”: Meanings of an HIV behavioural intervention in rural South African young people’s lives. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:1074–1084. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jukes M, Simmons S, Bundy D. Education and vulnerability: the role of schools in protecting young women and girls from HIV in southern Africa. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 4):S41–S56. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000341776.71253.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettifor A, Bekker L-G, Hosek S, DiClemente R, Rosenberg M, Bull SS, et al. Preventing HIV among young people: research priorities for the future. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 2):S155–60. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829871fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardee K, Gay J, Croce-Galis M, Afari-Dwamena NA. What HIV programs work for adolescent girls? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(Suppl 2):S176–85. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavin L, Galavotti C, Dube H, McNaghten AD, Murwirwa M, Khan R, et al. Factors associated with HIV infection in adolescent females in Zimbabwe. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:596.e11–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hargreaves JR, Morison LA, Kim JC, Bonell CP, Porter JDH, Watts C, et al. The association between school attendance, HIV infection and sexual behaviour among young people in rural South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:113–119. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pettifor AE, Levandowski BA, Macphail C, Padian NS, Cohen MS, Rees HV. Keep them in school: The importance of education as a protective factor against HIV infection among young South African women. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:1266–1273. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baird S, Chirwa E, McIntosh C, Ozler B. The short-term impacts of a schooling conditional cash transfer program on the sexual behavior of young women. Health Econ. 2010;19(Suppl):55–68. doi: 10.1002/hec.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birdthistle I, Floyd S, Nyagadza A, Mudziwapasi N, Gregson S, Glynn JR. Is education the link between orphanhood and HIV/HSV-2 risk among female adolescents in urban Zimbabwe? Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1810–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoner M, Pettifor A, Edwards J, Aiello A, Julien A, Selin A, et al. The effect of school attendance and school dropout on incident HIV and HSV-2 among young women in rural South Africa enrolled in HPTN 068 Title. 2017 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boerma JT, Weir SS. Integrating demographic and epidemiological approaches to research on HIV/AIDS: the proximate-determinants framework. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl):S61–S67. doi: 10.1086/425282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zambuko O, Mturi AJ. Sexual risk behaviour among the youth in the era of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 2005;37:569–584. doi: 10.1017/S0021932004007084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuilkowski SS, Jukes MCH. The impact of education on sexual behavior in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of the evidence. AIDS Care. 2012;24:562–76. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison A, Cleland J, Frohlich J. Young People’s Sexual Partnerships in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Patterns, Contextual Influences, and HIV Risk. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39:295–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stoner MCD, Edwards JK, Miller WC, Aiello AE, Halpern CT, Julien A, et al. Effect of Schooling on Age-Disparate Relationships and Number of Sexual Partners Among Young Women in Rural South Africa Enrolled in HPTN 068. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76:e107–e114. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kretzschmar M, Morris M. Measures of concurrency in networks and the spread of infectious disease. Math Biosci. 1996;133:165–195. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(95)00093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris M. Concurrent partnerships and syphilis persistence: new thoughts on an old puzzle. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:504–7. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Adolescents’ time use: Effects on substance use, delinquency and sexual activity. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36:697–710. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osgood DW, Wilson JK, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Routine Activities and Individual Deviant Behavior. Am Sociol Rev. 1996;61:635. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawdon JE. Daily routines and crime: Using routine activities as measures of Hirschi’s involvement. Youth Soc. 1999;30:395–415. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirschi T. A Control Theory of Delinquency. 1969 http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc6&NEWS=N&AN=2007-05262-005.

- 23.Burkett SR, White M. Hellfire and Delinquency: Another Look. J Sci Study Relig. 1974;13:455–462. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen LE, Felson M. Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach. Am Sociol Rev. 1979;44:588. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Selin A, Gómez-Olivé FX, Rosenberg M, Wagner RG, et al. HPTN 068: A Randomized Control Trial of a Conditional Cash Transfer to Reduce HIV Infection in Young Women in South Africa-Study Design and Baseline Results. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:1863–1882. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1270-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Hughes JP, Selin A, Wang J, Gómez-Olivé FX, et al. The effect of a conditional cash transfer on HIV incidence in young women in rural South Africa (HPTN 068): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Heal. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30253-4. Published Online First: 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin S-H, Young J, Logan R, Tchetgen EJT, VanderWeele TJ. Parametric mediational g-formula approach to mediation analysis with time-varying exposures, mediators, and confounders. Epidemiology. 2016;28:1. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westreich D, Cole SR, Young JG, Palella F, Tien PC, Kingsley L, et al. The parametric g-formula to estimate the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on incident AIDS or death. Stat Med. 2012;31:2000–2009. doi: 10.1002/sim.5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VanderWeele TJ. Causal mediation analysis with survival data. Epidemiology. 2012;22:582–585. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821db37e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.VanderWeele TJ. Marginal structural models for the estimation of direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 2009;20:18–26. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818f69ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mumford SL, Schisterman EF, Siega-Riz AM, Gaskins AJ, Wactawski-Wende J, Vanderweele TJ. Effect of dietary fiber intake on lipoprotein cholesterol levels independent of estradiol in healthy premenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:145–156. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naimi AI, Kaufman JS, MacLehose RF. Mediation misgivings: Ambiguous clinical and public health interpretations of natural direct and indirect effects. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1656–1661. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edwards JK, McGrath LJ, Buckley JP, Schubauer-Berigan MK, Cole SR, Richardson DB. Occupational radon exposure and lung cancer mortality: estimating intervention effects using the parametric g-formula. Epidemiology. 2014;25:829–834. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naimi A, Cole S, Hudgens M, Richardson D. Estimating the effect of cumulative occupational asbestos exposure on time to lung cancer mortality: using structural nested failure-time models to account for healthy-worker survivor bias. Epidemiology. 2014;25:246–54. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danaei G, Pan A, Hu FB, Hernán MA. Hypothetical midlife interventions in women and risk of type 2 diabetes. Epidemiology. 2013;24:122–8. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318276c98a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lajous M, Willett WC, Robins J, Young JG, Rimm E, Mozaffarian D, et al. Changes in fish consumption in midlife and the risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:382–391. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanderweele TJ, Tchetgen Tchetgen E. Mediation Analysis with Time-Varying Exposures and Mediators. Harvard Univerisity Biostat Work Pap Ser. 2014;168:1–22. doi: 10.1111/rssb.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kovacs M. The children’s depression inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cluver L, Gardner F, Operario D. Psychological distress amongst AIDS-orphaned children in urban South Africa. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boyes ME, Cluver LD. Performance of the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale in a sample of children and adolescents from poor urban communities in Cape Town. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2013;29:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, Özler B. Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wald A, Langenberg AGM, Link K, Izu AE, Ashley R, Warren T, et al. Effect of Condoms on Reducing the Transmission of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 From Men to Women. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285:3100–3106. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wald A, Krantz E, Selke S, Lairson E, Morrow RA, Zeh J. Knowledge of partners’ genital herpes protects against herpes simplex virus type 2 acquisition. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:42–52. doi: 10.1086/504717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, Puren A, et al. Impact of Stepping Stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a506–a506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenberg M, Pettifor A, Twine R, Hughes J, Gómez-Olivé FX, Wagner RG, et al. Selection and Hawthorne effects in an HIV prevention trial among young South African women. International Aids Society (IAS); Durban, South Africa: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.H K, G J, C-G M, A-D NA, Na HKGJC-GMA-D What HIV programs work for adolescent girls? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66(Suppl 2):S176–S185. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Acevedo-Polakovich I. Youth Go: An Out-of-School Time Program Friendly Approach to Gathering Youth Perspectives. Press. 2017 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.