Abstract

Introduction:

Cardiac arrest etiology is often assigned according to the Utstein template, which differentiates medical (formerly “presumed cardiac”) from other causes. These categories are poorly defined, contain within them many clinically distinct etiologies, and are rarely based on diagnostic testing. Optimal clinical care and research require more rigorous characterization of arrest etiology.

Methods:

We developed a novel system to classify arrest etiology using a structured chart review of consecutive patients treated at a single center after in- or out-of-hospital cardiac arrest over four years. Two reviewers independently reviewed a random subset of 20% of cases to calculate interrater reliability. We used X2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests to compare baseline clinical characteristics and outcomes across etiologies.

Results:

We identified 14 principal arrest etiologies, and developed objective diagnostic criteria for each. Inter-rater reliability was high (kappa = 0.80). Median age of 986 included patients was 60 years, 43% were female and 71% arrested out-of-hospital. The most common etiology was respiratory failure (148 (15%)). A minority (255 (26%)) arrested due to cardiac causes. Only nine (1%) underwent a diagnostic workup that was unrevealing of etiology. Rates of awakening and survival to hospital discharge both differed across arrest etiologies, with survival ranging from 6% to 60% (both P <0.001), and rates of favorable outcome ranging from 0% to 40% (P <0.001). Timing and mechanism of death (e.g. multisystem organ failure or brain death) also differed significantly across etiologies.

Conclusions:

Arrest etiology was identifiable in the majority cases via systematic chart review. “Cardiac” etiologies may be less common than previously thought. Substantial clinical heterogeneity exists across etiologies, suggesting previous classification systems may be insufficient.

Keywords: Cardiac arrest, post-arrest, etiology, epidemiology, outcomes

Introduction

Cardiac arrest is defined by cessation of circulation, and can result from many different disease processes, injuries or circumstances. Much of the literature sorts cardiac arrest into medical and non-medical causes,[1] previously referred to as “presumed cardiac” and “noncardiac” causes.[2] These categories are poorly defined, contain within them many different etiologies, and are usually assigned based on prehospital data without the benefit of diagnostic testing. A default value of medical (or presumed cardiac) is typically assigned if no readily apparent cause of arrest is identified. Medical treatment of patients who are resuscitated from cardiac arrest should be adapted to the particular disease process or etiology that led to cardiac arrest. Different interventions may be beneficial for cardiac arrest from one medical etiology (e.g. anticoagulation for thromboembolic disease) and inert or harmful in another (e.g. sepsis or gastrointestinal bleeding). Similarly chances of awakening from coma, survival, functionally favorable recovery or other important patient-centered outcomes such as coma duration or hospital length of stay may differ substantially depending on the cause of arrest. From the perspective of clinical research, unmeasured heterogeneity may increase the chance of neutral results. For example, a trial of cardiac catheterization after arrest from “presumed cardiac” causes might maximize its effect size by enrollment of patients with acute coronary syndrome, where as enrolling patients with congenital heart disease might reduce the effect size. Titrating clinical care, public health efforts, and selection of appropriate subjects for clinical trials requires more rigorous characterization of cardiac arrest etiology.

To address this need for patients hospitalized after cardiac arrest, we sought to develop a method to define cardiac arrest etiology using available clinical information in a structured and reproducible manner that could be used by other investigators or sites, thus allowing between-center comparisons of similar patients. We hypothesized that most patients could be assigned to well-defined categories that were meaningful to clinicians who care for these patients and clinical researchers. We secondarily aimed to report the frequency of different etiologies among a large cohort of patients, and compare clinical characteristics and patient outcomes across etiologies.

Methods

Study design and setting

We used a modified Delphi process to develop a novel arrest etiology classification system (see below). After finalizing our classification rubric, we performed a structured chart review of consecutive patients treated at a single academic medical center after resuscitation from in- or out- of-hospital cardiac arrest from February 15, 2012 to February 15, 2016. This center is a tertiary care referral center with an organized Post-Cardiac Arrest Service involved in clinical care, resuscitation research and ongoing quality improvement, as has been previously described in detail.[3, 4] We defined “cardiac arrest” as a patient who received chest compressions or defibrillation from a medical provider or a rescue shock from an automated external defibrillator, and included patients with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) for at least 20 minutes. Our Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this study with a waiver of informed consent.

Classification system development

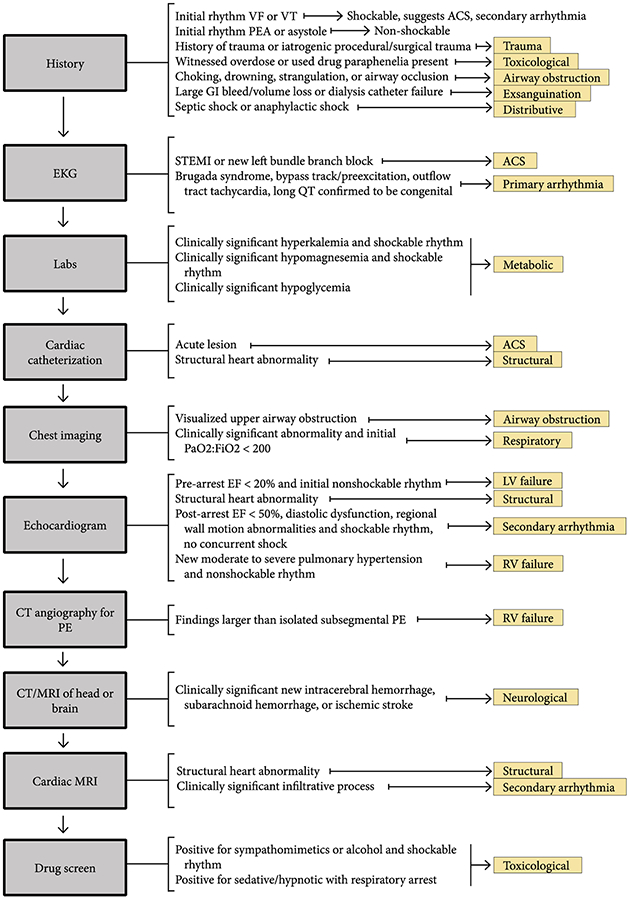

Our first step was to perform a literature review and 1 on 1 interview with sixteen content experts to develop an exhaustive list of potential arrest etiologies and potential working definitions of each. Participants included members of the Pittsburgh Post-Cardiac Arrest Service trained in emergency medicine and/or critical care medicine, interventional cardiologists, cardiac intensivists, neuro-intensivists and intensive care unit (ICU) nurses in the cardiac and neuroscience ICUs. Our initial list of potential arrest etiologies included 34 potential etiologies of cardiac arrest. We then used a modified Delphi process in which we asked participants to rank the importance of each category, propose revisions and group similar etiologies together when clinical heterogeneity was thought to be unimportant. We iteratively held a total of 6 meetings until consensus on a final list of arrest etiologies and broad definitions was reached. Finally, we developed precise criteria to rule in, rule out, or suggest each etiology, and a framework for structured chart review, both of which we presented at a final meeting for approval of the entire working group. Ultimately, this process resulted in 14 well-defined etiologies of cardiac arrest (Table 1, Figure 1) with associated objective diagnostic criteria (Supplemental Appendix 1) and a reproducible workflow for structured chart review (Figure 2). Arrest was only considered secondary to respiratory failure when primary pulmonary pathology (e.g. hypoxia or hypercarbia due to exacerbation of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or multifocal pneumonia) led to respiratory failure. In arrests where respiratory failure occurred secondary to an extrinsic cause (e.g. left ventricular failure causing pulmonary edema, pulmonary embolism, or opioid overdose), the inciting cause was considered the etiology of arrest (in those examples, left ventricular failure, right ventricular failure or toxicological etiology, respectively).

Table 1 –

Final cardiac arrest etiologies and their relative incidence among patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest, stratified by arrest location

| Cardiac arrest etiology | Overall cohort (n = 982) | Out-of-hospital arrests (n = 694) | In-hospital arrests (n =288) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute coronary syndrome | 135 (14) | 112 (16) | 23 (8) |

| Congenital arrhythmia | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Arrhythmia secondary to cardiomyopathy | 60 (6) | 44 (6) | 16 (6) |

| Structural heart disease | 7 (1) | 5 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Left ventricular failure | 12 (1) | 5 (1) | 7 (2) |

| Right ventricular failure | 36 (4) | 20 (3) | 16 (6) |

| Toxicological | 87 (9) | 78 (11) | 9 (3) |

| Upper airway obstruction | 54 (6) | 34 (5) | 20 (7) |

| Respiratory failure | 148 (15) | 85 (12) | 63 (22) |

| Neurological catastrophe | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Trauma | 24 (2) | 19 (2) | 5 (2) |

| Non-traumatic exsanguination | 25 (3) | 13 (2) | 12 (4) |

| Distributive shock | 33 (3) | 19 (3) | 14 (5) |

| Metabolic derangement | 46 (5) | 31 (4) | 15 (5) |

| Other identifiable etiology* | 42 (4) | 21 (3) | 21 (7) |

| Multiple likely etiologies# | |||

| Two likely etiologies | 116 (12) | 89 (13) | 27 (9) |

| Three likely etiologies | 36 (4) | 24 (3) | 12 (4) |

| Four or more possible etiologies | 17 (2) | 9 (1) | 8 (3) |

| Unknown etiology | |||

| Did not undergo diagnostic workup | 74 (7) | 57 (8) | 17 (6) |

| Extensive testing unrevealing | 9 (1) | 8 (1) | 1 (0) |

Other identifiable arrest etiologies were (number - etiology): 5 - Arrest during PCI, EP ablation or failure to terminate VT in EP lab; 5 - Long QT that could not be delineated as secondary to medications, metabolic disarray, congenital long QT or multifactorial; 3 - Peri-intubation; 3 - Smoke inhalation/CO burning; 3 - Hypothermia from exposure; 3 - Vasovagal; 2 - Seizure followed by cardiac arrest; 2 - Pacemaker failure; 2 - LVAD failure; 2 - Adverse reaction to chemotherapy infusion; 1 - Large bowel perforation; 1 - Electrocution; 1 - Autopsy: Physical stress of surgery complicating severe underlying heart disease; 1 - Autopsy: Ischemic bowel and cardiogenic shock due to severe CAD; 1 - Autopsy: suspected arrhythmia from severe LVH; 1 - Amiodarone toxicity; 1 - Aortic dissection leading to tamponade; 1 - Cyanide poisoning; 1 - Heart allograft rejection; 1 - Autopsy: Cardiomyopathy of pregnancy with acute MI; 1 - Severe hemolytic anemia; 1 - Spontaneous tension pneumothorax

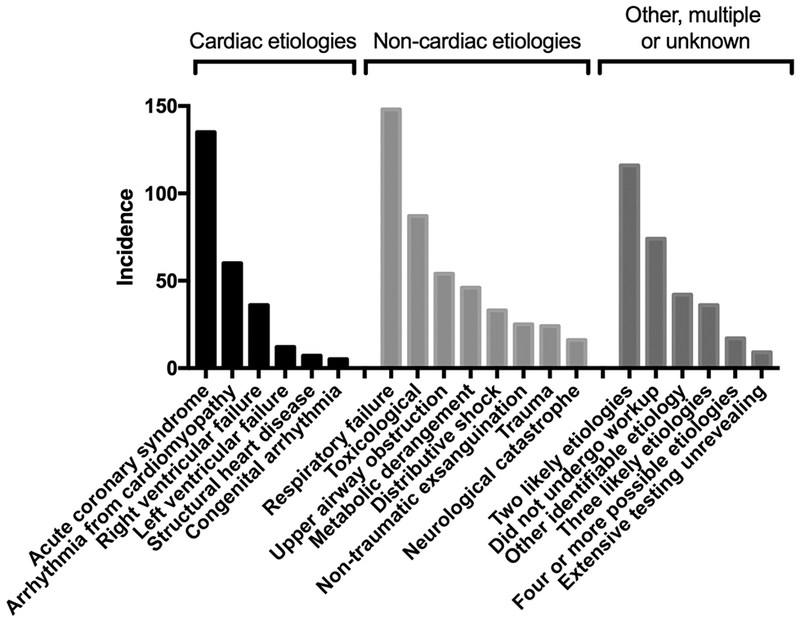

Figure 1:

Cardiac arrest etiologies, stratified by etiologies likely to be considered “presumed cardiac” under the classic Utstein template; non-cardiac etiologies; and other unclassified, multiple and unknown etiologies.

Figure 2:

Flowchart for determination of cardiac arrest etiology

Etiology measurement

We performed a structured chart review to extract results of: chest imaging (roentgenogram, computerized tomography (CT) and bronchoscopy); electrocardiograms; cardiac catheterization; echocardiography; cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); CT angiography for pulmonary embolism; CT or MRI of the brain; electrophysiology studies; vascular duplex ultrasound; urine drug screens; serum glucose, troponin, magnesium, and potassium levels; and attending physician impression as documented in daily progress notes during the index admission. We collected data for each patient in a standardized template built in REDCap. If multiple providers from different specialties provided differing accounts of the pre-arrest history, these details were not used in the categorization of etiology. We classified patients as having a given arrest etiology if they met rule-in criteria for only that single etiology. Patients who had findings suggestive of multiple etiologies were categorized as unknown.

Clinical covariates and outcomes

We used our prospective registry to abstract patient demographics including age, gender, arrest location, initial arrest rhythm and Pittsburgh Cardiac Arrest Category (PCAC). PCAC is a validated 4-level ordinal scale modeling post-arrest illness severity that is strongly predictive of outcomes at hospital discharge.[5, 6] Outcomes were survival to hospital discharge, discharge disposition (home, acute rehabilitation, skilled nursing facility, long-term acute care facility, hospice or death) and time to awakening. We considered patients to have a favorable functional outcome at hospital discharge if they were discharged to home or acute rehabilitation. Among nonsurvivors, we also abstracted the mode of death, which we categorized as withdrawal based on perceived poor neurological prognosis; progression to brain death; rearrest, intractable shock or other non-survivable extra-cerebral organ failure; or, withdrawal based on non-neurological factors (e.g. preexisting advanced directives or advanced pre-arrest comorbidities).

Statistical methods

We used descriptive statistics to summarize baseline population characteristics and outcomes. We used Chi2 tests to compare categorical variables across arrest etiologies and Kruskal-Wallis tests to compare continuous variables across etiologies, and report Bonferroni-corrected P values to correct for account comparisons. Next, we compared clinical characteristics and outcomes restricted to arrest etiologies that would be considered medical (or presumed cardiac) under the Utstein template to test for heterogeneity across these etiologies. Two reviewers independently abstracted data and assigned arrest etiology on a random subset of 20% of cases and we calculated inter-rater reliability within this subset. Cases of disagreement were reclassified as having multiple possible etiologies. We used Stata Version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for all analyses.

Results

Cohort characteristics

Overall, there were 1006 patients who presented during the 4-year study period. Of these, 24 patients were determined on chart review not to have suffered a true cardiac arrest or did not have ROSC, and were therefore excluded, leaving 982 patients in our final cohort. Median age was 60 years [interquartile range (IQR) 49 – 71] and 418 (43%) were female (Table 2). Only 291 patients (30%) had an initial shockable rhythm, with 397 (40%) pulseless electrical activity, 217 (22%) asystole, and the remaining 77 (8%) unknown. Most subjects 694 (71%) arrested out of hospital. When graded on initial illness severity, 210 (21%) were PCAC I (awake in the first 6 hours after ROSC), 154 (16%) were PCAC II (light coma without severe cardiopulmonary dysfunction), 93 (7%) were PCAC III (light coma with severe cardiopulmonary dysfunction), 444 (45%) were PCAC IV (deep coma with loss of some brainstem reflexes) and in 81 (8%) PCAC could not be determined because of uncorrectable confounders or delayed presentation.

Table 2:

Overall cohort clinical characteristics and outcomes

| Characteristic | Overall cohort (n = 982) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 60 [49 – 71] |

| Female sex | 418 (43) |

| Arrest out-of-hospital | 694 (71) |

| PCAC | |

| I | 210 (21) |

| II | 154 (16) |

| III | 93 (9) |

| IV | 444 (45) |

| Unknown | 81 (8) |

| Arrest rhythm | |

| VT/VF | 291 (30) |

| PEA | 397 (40) |

| Asystole | 217(22) |

| Unknown | 77 (8) |

| Survival to discharge | 380 (39) |

| Responsive at discharge* | 335 (88) |

| Ever responsive | 390 (40) |

| Good outcome | 236 (24) |

| Days to awakening | 1 [0 – 3] |

| Discharge disposition* | |

| Home | 147 (39) |

| Acute rehab | 89 (23) |

| SNF | 85(22) |

| LTAC | 35 (9) |

| Hospice | 17 (4) |

| Other | 7 (2) |

| Mode of death# | |

| Unstable | 212 (35) |

| Brain death | 40 (8) |

| WLST - non-neurological reasons | 72 (12) |

| WLST - neurological prognosis | 268 (45) |

| Length of stay, days | |

| Survivors | 14 [8 – 22] |

| Non-survivors | 2 [1 – 4] |

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] for continuous variables and raw number with corresponding percentages for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: PCAC - Pittsburgh Cardiac Arrest Category; VT/VF - Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation; PEA - Pulseless electrical activity; SNF - Skilled nursing facility; LTAC - Long-term acute care facility; WLST - Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy

Data are presented as the proportion of survivors to discharge. # Data are presented as the proportion of non-survivors

Of the 771 patients that were initially comatose, 204 (26%) awakened from coma to follow verbal commands. Survival to hospital discharge was 39%, and 236 (24% overall, 62% of survivors) were discharged with functionally favorable outcomes. Among non-survivors, 268 (45%) had life-sustaining therapy withdrawn for perceived poor neurological prognosis, 50 (8%) progressed to brain death, 72 (12%) had withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy for non-neurological reasons, and 212 (35%) succumbed to multisystem organ failure, intractable shock or rearrest.

Arrest etiologies

The most common single etiology of arrest was respiratory failure (148 (15%)), with an additional 54 (6%) of arrests due to focal upper airway obstruction (Table 1). A minority of subjects (255 (26%)) had an arrest etiology attribute to cardiac causes, of which most (135/255 (53%); 12% of overall patients) were acute coronary syndrome. Only nine subjects (1%) underwent a diagnostic workup for arrest etiology that was unrevealing, while 74 (7%) did not undergo a diagnostic workup (Table 1). Of these 83 subjects with unknown arrest etiologies, most (58%) rearrested, progressed to brain death or had limitations of care because of pre-existing advanced directives within 24 hours of admission. The incidence of unknown arrest etiologies did not differ by arrest location (P=0.11). There were 169 subjects (17%) that met diagnostic criteria for more than one arrest etiology (Table 1, Supplemental Appendix 2). Among those meeting criteria for two arrest etiologies, the most common combinations were acute coronary syndrome with arrhythmia secondary to cardiomyopathy, and respiratory failure with other well-defined etiology, each accounting for 9% of these 116 cases (Supplemental Appendix 2). Inter-rater reliability was high (kappa = 0.80). In cases of disagreement, most (65%) occurred when one adjudicator judged there to be two potential arrest etiologies while the other adjudicator felt only one of these etiologies was likely.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes across etiologies

Nearly all baseline clinical characteristics and outcomes differed significantly across arrest etiologies (Table 3). Among etiologies with at least 10 subjects, rates of awakening from coma and survival to hospital discharge both ranged from 6% to 60% (both P <0.001), and rates of favorable outcome at discharge ranged from 0% to 40% (P <0.001). Nearly one third of decedents with a toxicological or neurological etiology of arrest progressed to brain death, while only 2% of patients with respiratory failure and no patients with acute coronary syndrome progressed to brain death (P <0.001). By contrast, the majority of decedents who arrested secondary to left ventricular failure, exsanguination, or other well-defined etiologies of arrest not included in other categories succumbed to rearrest, intractable shock or multisystem organ failure (P <0.001).

Table 3:

Comparisons of baseline characteristics and outcomes across arrest etiologies. Etiologies likely to be classified as “medical” under the Utstein template are denoted with gray shading.

| Characteristic | Arrest etiology | P value+ | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 n = 135 | 2 n = 5 | 3 n = 60 | 4 n = 7 | 5 n = 12 | 6 n = 36 | 7 n = 87 | 8 n = 54 | 9 n = 148 | 10 n = 16 | 11 n = 24 | 12 n = 25 | 13 n = 33 | 14 n = 46 | 15 n = 42 | 16 n = 166 | 17 n = 83 | ||

| Age, years | 61 [53–69] | 31 [19–41] | 63 [53–71] | 22 [19–42] | 58 [45–77] | 60 [49–65] | 37 [28–50] | 54 [40–68] | 63 [53–73] | 56 [47–64] | 59 [34–67] | 60 [53–69] | 62 [55–70] | 61.5 [49–74] | 60 [36–67] | 64 [54–74] | 67 [55–80] | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 50 (37) | 2 (40) | 18 (30) | 5 (71) | 5 (42) | 23 (64) | 35(40) | 12 (22) | 71 (48) | 11 (69) | 10 (42) | 11 (44) | 24(73) | 23 (50) | 18(43) | 68(40) | 32 (39) | <0.001 |

| Arrest out-of-hospital | 112 (83) | 5(100) | 44(73) | 5 (71) | 5 (42) | 20 (56) | 78(90) | 34 (63) | 85 (57) | 16(100) | 19 (79) | 13 (52) | 19 (58) | 31 (67) | 21 (50) | 122(72) | 65 (78) | <0.001 |

| PCAC | <0.001 | |||||||||||||||||

| I | 55(41) | 1 (20) | 21 (35) | 2 (29) | 4 (33) | 12 (33) | 9 (10) | 2 (4) | 31 (21) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 5 (20) | 12 (36) | 11 (24) | 12 (29) | 24 (14) | 7 (8) | |

| II | 28(21) | 4 (80) | 13 (22) | 2 (29) | 0 (0) | 5 (14) | 12 (14) | 15(28) | 20 (14) | 1 (6) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 9 (20) | 5 (12) | 25(15) | 10 (12) | |

| III | 11 (8) | 0 (0) | 8 (13) | 2 (29) | 2 (17) | 4 (11) | 3 (3) | 2 (4) | 18 (12) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 4 (10) | 26(15) | 5 (6) | |

| IV | 34 (25) | 0 (0) | 15 (25) | 1 (14) | 4 (33) | 14 (39) | 54 (62) | 31 (57) | 68(46) | 10 (63) | 16 (67) | 8 (32) | 13 (39) | 18 (39) | 17 (40) | 87 (51) | 54 (65) | |

| Unknown | 7 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (17) | 1 (3) | 9 (10) | 4 (7) | 11 (7) | 4 (25) | 4 (17) | 7 (28) | 5 (15) | 6 (13) | 4 (10) | 7 (4) | 7 (8) | |

| Arrest rhythm | <0.001 | |||||||||||||||||

| VT/VF | 106 (79) | 5(100) | 52 (87) | 2 (29) | 3 (25) | 1 (3) | 6 (7) | 3 (6) | 6 (4) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (16) | 2 (6) | 22 (48) | 15 (36) | 43 (25) | 20 (24) | |

| PEA | 9 (7) | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 3 (43) | 6 (50) | 28 (78) | 42 (48) | 24 (44) | 85 (57) | 8 (50) | 14 (58) | 19 (76) | 23 (70) | 13 (28) | 12 (29) | 72(43) | 36(43) | |

| Asystole | 17(13) | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | 1 (14) | 3 (25) | 6 (17) | 28 (32) | 19 (35) | 43 (29) | 4 (25) | 6 (25) | 1 (4) | 6 (18) | 7 (15) | 11(26) | 41 (24) | 20 (24) | |

| Unknown | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 11(13) | 8 (15) | 14 (9) | 3 (19) | 4 (17) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 4 (9) | 4 (10) | 13 (8) | 7 (8) | |

| Survival to discharge | 81 (60) | 5(100) | 32(53) | 6 (86) | 5 (42) | 17 (47) | 32 (37) | 18 (33) | 53 (36) | 1 (6) | 7 (29) | 6 (24) | 9 (27) | 23 (50) | 21 (50) | 48 (28) | 16 (19) | <0.001 |

| Responsive at discharge* | 75(93) | 5(100) | 30 (94) | 5 (83) | 5(100) | 17(100) | 25(78) | 13 (72) | 46 (87) | 1 (100) | 6 (86) | 6(100) | 9(100) | 23(100) | 20 (95) | 35(73) | 15 (94) | 0.02 |

| Ever responsive | 81 (60) | 5(100) | 35 (58) | 5 (71) | 5 (42) | 19(53) | 26 (30) | 16 (30) | 59 (40) | 1 (6) | 7 (29) | 9 (36) | 12 (38) | 26 (57) | 22 (52) | 45 (27) | 17 (20) | <0.001 |

| Good outcome | 54 (40) | 5(100) | 20 (33) | 5 (71) | 2 (17) | 10(28) | 22(25) | 12 (22) | 22(15) | 0 (0) | 6 (25) | 4 (16) | 6 (18) | 13 (28) | 16 (38) | 29 (17) | 10 (12) | <0.001 |

| Days to awakening | 1 [0–2] | 3 [2–3] | 1 [0–3] | 1 [1–1] | 2 [1–2] | 1 [0–2] | 2 [1–6] | 2 [1–5] | 1 [0–3] | 2 [2–2] | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–3] | 0.5 [0–1] | 1.5 [1–3] | 1 [0–3] | 1 [0–3] | 1 [1–2] | 0.31 |

| Discharge disposition* | 0.10 | |||||||||||||||||

| Home | 43 (53) | 3 (60) | 13 (41) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 7 (41) | 10 (31) | 7 (39) | 13 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 3 (50) | 3 (33) | 9 (39) | 11 (52) | 18 (38) | 3 (19) | |

| Acute rehab | 11(14) | 2 (40) | 7 (22) | 2 (33) | 2 (40) | 3 (18) | 12 (38) | 5 (28) | 9 (17) | 0 (0) | 5 (71) | 1 (17) | 3 (33) | 4 (17) | 5 (24) | 11(23) | 7 (44) | |

| SNF | 20 (25) | 0 (0) | 7 (22) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | 4 (24) | 4 (13) | 1 (6) | 17 (32) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 1 (11) | 9 (39) | 3 (14) | 9 (19) | 5 (31) | |

| LTAC | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) | 2 (6) | 2 (11) | 10 (19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | 1 (11) | 1 (4) | 2 (10) | 8 (17) | 1 (6) | |

| Hospice | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (3) | 2 (11) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Mode of death# | <0.001 | |||||||||||||||||

| Unstable | 21 (39) | -- | 13 (46) | 0 (0) | 5 (71) | 9 (47) | 10 (18) | 5 (14) | 28 (29) | 0 (0) | 3 (18) | 11 (58) | 17 (71) | 8 (35) | 11 (52) | 42 (35) | 29(43) | |

| Brain death | 0 (0) | -- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 16 (29) | 3 (8) | 2 (2) | 5 (33) | 3 (18) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (14) | 7 (6) | 8 (12) | |

| WLST - non-neurological reasons | 4 (7) | -- | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 1 (5) | 3 (5) | 5 (14) | 19 (20) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 2 (11) | 4 (17) | 3 (13) | 1 (5) | 15 (12) | 11(16) | |

| WLST - neurological prognosis | 29 (54) | -- | 13 (46) | 1 (100) | 1 (14) | 7 (37) | 26 (47) | 23 (64) | 46 (48) | 10 (67) | 10 (59) | 6 (32) | 2 (8) | 12 (52) | 6 (29) | 57 (47) | 19 (28) | |

| Length of stay, days | ||||||||||||||||||

| Survivors | 10 [6–16] | 12 [7–18] | 14 [8–18] | 15 [9–21] | 22 [18–28] | 15 [11–21] | 18 [8–27] | 12.5 [6–19] | 16 [11–24] | 44 [44–44] | 14 [8–41] | 16 [12–16] | 14 [7–25] | 16 [10–20] | 10 [4–15] | 15 [8–25] | 19 [9–29] | 0.04 |

| Non-survivors | 3 [1–6] | -- | 4 [1–5] | 3 [3–3] | 2 [1–4] | 1 [0–2] | 2 [1–4] | 3 [1–5] | 3 [1–5] | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–3] | 1 [0–5] | 1 [0–3] | 4 [1–5] | 2 [1–4] | 2 [1–4] | 1 [0–2] | <0.001 |

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] for continuous variables and raw number with corresponding percentages for categorical variables.

Etiology abbreviations: 1 - Acute coronary syndrome; 2 - Intrinsic arrhythmia; 3 - Arrhythmia secondary to cardiomyopathy; 4 - Structural heart disease; 5 - Left ventricular failure; 6 - Right ventricular failure; 7 - Toxicological; 8 - Upper airway obstruction; 9 - Respiratory failure; 10 - Neurological catastrophe; 11 - Trauma; 12 - Non-traumatic exsanguination; 13 - Distributive shock; 14 - Metabolic derangement; 15 - Other identifiable etiology; 16 - Multiple likely etiologies; 17 - Unknown

Abbreviatioηs: PCAC - Pittsburgh Cardiac Arrest Category; VT/VF - Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation; PEA -Pulseless electrical activity; SNF - Skilled nursing facility; LTAC - Long-term acute care facility; WLST - Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy

Data are presented as the proportion of survivors to discharge. # Data are presented as the proportion of non-survivors

P values are Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons.

Among the 338 patients with etiologies likely to have been classified as medical under the Utstein template (acute coronary syndrome, intrinsic arrhythmia, arrhythmia secondary to cardiomyopathy, structural heart disease, left ventricular failure, right ventricular failure and unknown), 236 (70%) were initially comatose, and of these rates of awakening from coma differed significantly across etiologies (range 13% to 100%, P <0.001). Of these 338 subjects, survival to discharge differed (range 16% to 60%, P<0.001), as did functionally favorable survival (range 9% to 100%, P<0.001). Clinical outcomes also differed across etiologies when restricted to the subset of patients with non-medical (not “presumed cardiac”) etiologies under the Utstein template. Survival to discharge ranged from 6% to 50% (P =0.01) while functionally favorable survival ranged from 0% to 28% (P = 0.01).

Discussion

We present a novel system to classify cardiac arrest etiology in the cohort of patients surviving to hospital care after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Using our rubric, most patients had a well-defined etiology of arrest. Our system includes seven etiologies that historically have been grouped together as medical (or presumed cardiac) etiologies, as well as seven other etiologies deemed to be clinically important. We observed a 10-fold difference in the rates of awakening and survival to discharge across etiologies, and even greater differences in incidence of rearrest and brain death. The National Academies of Medicine has highlighted post-arrest care and personalized medicine as research priorities.[7] Our classification method builds towards these priorities by capturing an important source of between patient heterogeneity that has frequently been overlooked. We believe this methodology has immediate relevance to clinical practice, epidemiological research and the design and conduct of resuscitation trials.

The Utstein style of reporting has largely defined standard terminology and reporting in resuscitation. This influential consensus recommendation initially dichotomized arrest etiology as “presumed cardiac” or “non-cardiac,” specifying that cases in which the arrest etiology is not readily apparent classified as presumed cardiac.[2] In subsequent updates, “presumed cardiac” etiologies were reclassified as “medical,” while “non-cardiac” etiologies were further stratified as trauma, drowning, overdose, electrocution and asphyxial.[1] The template is optimized for performance in the prehospital setting, where many diagnostic modalities are unavailable and a minority of patients achieves ROSC. As such, under this system most cases are classified as medical (or presumed cardiac) arrests.[8–10] At the same time, the incidence of cardiac arrest acute coronary syndrome and structural heart disease continues to decrease, while arrests due to opioid overdose and IHCA are increasing.[7, 11] Classifying OHCAs without an extrinsic cause obvious to prehospital providers as “medical” does not capture an between-patient heterogeneity in terms of post-arrest pathophysiology, treatment responsiveness and outcomes.

Other strategies have been previously used to more precisely define the underlying etiology of cardiac arrest. In non-survivors of OHCA, autopsy may elucidate the cause of arrest in a substantial proportion of subjects.[9] For those surviving to hospital arrival after OHCA with no obvious cause of arrest, systematic coronary angiography and CT identifies more than half of arrest etiologies.[10] These methods have limitations as well. Autopsy studies cannot be used to inform research or care of those successfully resuscitated, and routine use of coronary angiography may have a lower diagnostic yield in populations where acute coronary syndrome is less common, such as the cohort we present.

Our classification system may be a useful framework to guide clinicians’ initial diagnostic workup and early resuscitative interventions, thereby improving the quality of post-arrest care. Most of the tests used to determine arrest etiology can be rapidly obtained at most medical centers within hours of hospital arrival. A rapid, directed diagnostic workup to define arrest etiology may be useful insofar as many causes of arrest benefit from time sensitive interventions like coronary revascularization,[12] thrombolysis,[13] surgical intervention, antidotes, or rapid correction of other inciting causes.[14] Equally importantly, among survivors to hospital discharge, accurate identification of arrest etiology can guide efforts in secondary prevention such as implantable defibrillator placement,[15] initiation of new medications,[16] post-acute psychiatric care and addiction counseling,[17] or other etiology-specific post-acute care. It can also serve to inform clinicians and families about the anticipated clinical course and outcomes in this population, both in terms of prospects for survival and favorable recovery at discharge as well as potentially unavoidable mechanisms of in-hospital mortality such as early rearrest or progression to brain death.

Our findings have potential epidemiological and public health significance as well. We note that in our cohort, etiologies historically grouped as medical (or presumed cardiac) represent a minority of overall cases, with only 14% due to acute coronary syndrome and 7% due to various arrhythmias. This may be due in part to our inclusion of IHCA patients and the fact that our cohort is restricted to those surviving to hospital care. As these patient populations grow, they are priorities for future research.[7] The distribution of etiologies we identified likely also reflects the changing demographics of cardiac arrest. Over time, the incidence of shockable rhythms has fallen with improved secondary prevention,[7] the population of the United States has aged and become more chronically ill,[18] and new medical conditions like opioid dependence and overdose are becoming more prevalent.[19] Important secular trends in the epidemiology of cardiac arrest etiology can only be measured by a granular classification system.

The inability of prior classification systems to measure clinically significant heterogeneity may in part explain the preponderance of neutral results from cardiac arrest trials.[20] Many postarrest interventions that may be lifesaving after a particular cause of cardiac arrest (e.g. coronary angiography for acute coronary syndrome) may be inert in other populations (e.g. coronary angiography for a congenital arrhythmia). Inclusion and randomization of patients in whom an intervention is inert reduces a study’s effect size and may result in inadequate power. Worse, lifesaving interventions for one group (e.g. thrombolysis after massive pulmonary embolism) may be frankly harmful in others (e.g. thrombolysis after arrest from hemorrhage). Reasonable investigators may speculate that distinct patterns of injury, clinical phenotypes or individual patient need resulting from specific arrest etiologies may benefit from different depths or durations of hypothermia (various comparisons have been equivalent at population levels [21, 22]), pharmacological neuroprotective strategies (all phase III trials to date have been neutral [23]), or other general aspects of post-arrest critical care.

Our work has several important limitations. First, to date our methodology lacks external validation. As a high volume cardiac arrest receiving center with organized systems of care, the population we included not be generalizable to other settings due to survival bias, selection bias on the part of the referring physicians and indication bias with respect to patients who are transferred by nature of their need for specialized care. This may have enriched our population for specific arrest etiologies while decreasing the apparent incidence of others. Outside the center effect, the incidence of each etiology reflects regional data that may not translate to other parts of the world. For example, the incidence of toxicological arrests, most of which were attributed to accidental opioid overdose, would not be expected to reflect the incidence in countries where opioid dependence and recreational drug overdose are rare. Additionally, determination of a final arrest etiology is dependent on clinician-driven diagnostic testing. Although most of these tests are standard of care (electrocardiography, chest roentgenography, blood chemistries, etc), some tests such as cardiac MRI or genetic testing may only be available or preferentially obtained in a tertiary care setting. Together, these factors may alter the frequency of given etiologies within our system or increase the frequency of unknown etiologies in systems with fewer resources. By contrast, were diagnostic tests to be acquired systematically in all patients regardless of clinical suspicion (e.g. routine cardiac catheterization or chest CT), the proportion of patients with unknown arrest etiology would be expected to decline.

In conclusion, we present a novel classification system for arrest etiology in patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest with clinical, epidemiological and research significance. Arrest etiology was identifiable in the large majority of cases through systematic chart review and clinician-directed diagnostic testing. A minority of patients, even those arresting out-of-hospital, arrested due to etiologies historically described as medical (or presumed cardiac), and even within this subgroup we found significant heterogeneity in clinical characteristics and outcomes. Previous classification systems likely underestimate the diversity of cardiac arrest etiology, supporting the need for validated classification schema to inform post-arrest care and future study designs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

REDCap infrastructure development is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through Grant Number UL1-TR-001857. Dr. Elmer’s research time is supported by NIH grants 5K12HL109068 and 1K23NS097629.

References

- 1.Perkins GD, Jacobs IG, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, Bhanji F, Biarent D, Bossaert LL, Brett SJ, Chamberlain D, de Caen AR, Deakin CD, Finn JC, Grasner JT, Hazinski MF, Iwami T, Koster RW, Lim SH, Huei-Ming Ma M, McNally BF, Morley PT, Morrison LJ, Monsieurs KG, Montgomery W, Nichol G, Okada K, Eng Hock Ong M, Travers AH, Nolan JP, Utstein C, (2015) Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update of the Utstein Resuscitation Registry Templates for Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa, Resuscitation Council of Asia); and the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Circulation 132: 1286–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Abramson NS, Allen M, Baskett PJ, Becker L, Bossaert L, Delooz HH, Dick WF, Eisenberg MS, et al. , (1991) Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the Utstein Style. A statement for health professionals from a task force of the American Heart Association, the European Resuscitation Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Australian Resuscitation Council. Circulation 84: 960–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rittenberger JC, Guyette FX, Tisherman SA, DeVita MA, Alvarez RJ, Callaway CW, (2008) Outcomes of a hospital-wide plan to improve care of comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 79: 198–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elmer J, Rittenberger JC, Coppler PJ, Guyette FX, Doshi AA, Callaway CW, Pittsburgh Post-Cardiac Arrest S, (2016) Long-term survival benefit from treatment at a specialty center after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 108: 48–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coppler PJ, Elmer J, Calderon L, Sabedra A, Doshi AA, Callaway CW, Rittenberger JC, Dezfulian C, the Post Cardiac Arrest S, (2015) Validation of the Pittsburgh Cardiac Arrest Category illness severity score. Resuscitation [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Rittenberger JC, Tisherman SA, Holm MB, Guyette FX, Callaway CW, (2011) An early, novel illness severity score to predict outcome after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 82: 1399–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keller SP, Halperin HR, (2015) Cardiac arrest: the changing incidence of ventricular fibrillation. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 17: 392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daya MR, Schmicker RH, Zive DM, Rea TD, Nichol G, Buick JE, Brooks S, Christenson J, MacPhee R, Craig A, Rittenberger JC, Davis DP, May S, Wigginton J, Wang H, Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium I, (2015) Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival improving over time: Results from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC). Resuscitation 91: 108–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braggion-Santos MF, Volpe GJ, Pazin-Filho A, Maciel BC, Marin-Neto JA, Schmidt A, (2015) Sudden cardiac death in Brazil: a community-based autopsy series (2006–2010). Arq Bras Cardiol 104: 120–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chelly J, Mongardon N, Dumas F, Varenne O, Spaulding C, Vignaux O, Carli P, Charpentier J, Pene F, Chiche JD, Mira JP, Cariou A, (2012) Benefit of an early and systematic imaging procedure after cardiac arrest: insights from the PROCAT (Parisian Region Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest) registry. Resuscitation 83: 1444–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmer J, Lynch MJ, Kristan J, Morgan P, Gerstel SJ, Callaway CW, Rittenberger JC, Pittsburgh Post-Cardiac Arrest S, (2015) Recreational drug overdose-related cardiac arrests: break on through to the other side. Resuscitation 89: 177–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, Chambers CE, Ellis SG, Guyton RA, Hollenberg SM, Khot UN, Lange RA, Mauri L, Mehran R, Moussa ID, Mukherjee D, Ting HH, O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Jr., Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Diercks DB, Fang JC, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, (2016) 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI Focused Update on Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: An Update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation 133: 1135–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, Agnelli G, Galie N, Pruszczyk P, Bengel F, Brady AJ, Ferreira D, Janssens U, Klepetko W, Mayer E, Remy-Jardin M, Bassand JP, Guidelines ESCCfP, (2008) Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 29: 2276–2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truhlar A, Deakin CD, Soar J, Khalifa GE, Alfonzo A, Bierens JJ, Brattebo G, Brugger H, Dunning J, Hunyadi-Anticevic S, Koster RW, Lockey DJ, Lott C, Paal P, Perkins GD, Sandroni C, Thies KC, Zideman DA, Nolan JP, Cardiac arrest in special circumstances section C, (2015) European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015: Section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation 95: 148–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santini M, Lavalle C, Ricci RP, (2007) Primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death: who should get an ICD? Heart 93: 1478–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, Jimenez D, Bounameaux H, Huisman M, King CS, Morris TA, Sood N, Stevens SM, Vintch JR, Wells P, Woller SC, Moores L, (2016) Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 149: 315–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, Sivilotti ML, Hutson JR, Mamdani MM, Koren G, Juurlink DN, Canadian Drug S, Effectiveness Research N, (2016) Repetition of intentional drug overdose: a population-based study. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 54: 585–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Disease Control and Prevention - Division of Population Health - National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2013) The State of Aging and Health in America 2013. In: Editor (ed)Λ(eds) Book The State of Aging and Health in America 2013. City, pp.

- 19.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM, (2016) Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths--United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64: 13781382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callaway CW, (2017) Targeted Temperature Management After Cardiac Arrest: Finding the Right Dose for Critical Care Interventions. Jama 318: 334–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkegaard H, Soreide E, de Haas I, Pettila V, Taccone FS, Arus U, Storm C, Hassager C, Nielsen JF, Sorensen CA, Ilkjaer S, Jeppesen AN, Grejs AM, Duez CHV, Hjort J, Larsen AI, Toome V, Tiainen M, Hastbacka J, Laitio T, Skrifvars MB, (2017) Targeted Temperature Management for 48 vs 24 Hours and Neurologic Outcome After Out-ofHospital Cardiac Arrest: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 318: 341–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Gasche Y, Hassager C, Horn J, Hovdenes J, Kjaergaard J, Kuiper M, Pellis T, Stammet P, Wanscher M, Wise MP, Aneman A, Al-Subaie N, Boesgaard S, Bro-Jeppesen J, Brunetti I, Bugge JF, Hingston CD, Juffermans NP, Koopmans M, Kober L, Langorgen J, Lilja G, Moller JE, Rundgren M, Rylander C, Smid O, Werer C, Winkel P, Friberg H, Investigators TTMT, (2013) Targeted temperature management at 33 degrees C versus 36 degrees C after cardiac arrest. The New England journal of medicine 369: 2197–2206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taccone FS, Crippa IA, Dell’Anna AM, Scolletta S, (2015) Neuroprotective strategies and neuroprognostication after cardiac arrest. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 29: 451–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.