Abstract

Background

Many general anesthetics were discovered empirically, but primary screens to find new sedative-hypnotics in drug libraries have not used animals, limiting the types of drugs discovered. We hypothesized that a sedative-hypnotic screening approach using zebrafish larvae responses to sensory stimuli would perform comparably to standard assays, and efficiently identify new active compounds.

Methods

We developed a binary outcome photomotor response assay for zebrafish larvae using a computerized system that tracked individual motions of up to 96 animals simultaneously. The assay was validated against tadpole loss-of-righting-reflexes, using sedative-hypnotics of widely varying potencies that affect various molecular targets. 374 representative compounds from a larger library were screened in zebrafish larvae for hypnotic activity at 10 μM. Molecular mechanisms of hits were explored in anesthetic-sensitive ion channels using electrophysiology, or in zebrafish using a specific reversal agent.

Results

Zebrafish larvae assays required far less drug, time and effort than tadpoles. In validation experiments, zebrafish and tadpole screening for hypnotic activity agreed 100% (n = 11; p =0.002) and potencies were very similar (Pearson correlation, r > 0.999). Two reversible and potent sedative-hypnotics were discovered in the library subset. CMLD003237 (EC50 ~ 11 μM) weakly modulated γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors and inhibited neuronal nicotinic receptors. CMLD006025 (EC50 ~ 13 μM), inhibited both n-methyl-D-aspartate and neuronal nicotinic receptors.

Conclusions

Photomotor response assays in zebrafish larvae are a mechanism-independent platform for high-throughput screening to identify novel sedative-hypnotics. The variety of chemotypes producing hypnosis is likely much larger than currently known.

Keywords: Adrenergic receptor, Anesthetic Mechanism, Drug Discovery, GABAA Receptors, General Anesthesia, Glutamate Receptor, Ion channel, Nicotinic Receptor, Photomotor response, Potency, Righting Reflexes

Introduction

General anesthesia is an essential tool in modern medicine and there is growing interest in developing new sedative-hypnotics with improved clinical utility1,2. Current and past clinical sedative-hypnotics represent a variety of anesthetic chemotypes (volatile ethers, barbiturates, phenylacetates, alkyl phenols, arylcyclohexylamines, imidazoles, and steroids), many identified by empiric observation, before 1980. Most new hypnotics in clinical development are modifications or reformulations of these drugs1.

Drug libraries may contain many more un-discovered sedative-hypnotics. Several screening strategies to identify hypnotics have been reported, most based on established molecular targets of anesthetics, particularly GABAA receptors. Direct target-based screening approaches detect modulation of specific GABAA receptor subtypes expressed in cells3–6. In silico screening approaches calculate binding energies between candidate ligands and pharmacophores derived from high-resolution structures of GABAA receptors or homologs7–9. Another drug screening strategy detected displacement of a fluorescent anesthetic from horse apoferritin binding sites formed among α-helical bundles, similar to those in GABAA receptors10,11. These indirect hypnotic discovery strategies have used secondary electrophysiological tests for GABAA receptor modulation.

However, not all clinical anesthetics modulate GABAA receptors12,13. Many sedative-hypnotics apparently act via other molecular targets14,15, and these would likely be missed by target-based screening strategies.

Stimulus-response tests in animals potentially represent a mechanism-independent screening approach for sedative-hypnotic drug activity. The most common such test in vertebrates is loss-of-righting-reflexes (LoRR), in which drug-exposed animals are placed supine and observed for return to the normal prone or four-leg standing position. Accurate pharmacodynamic measurements using LoRR tests require steady-state drug concentrations in an animal’s nervous system. In rodents, establishing steady-state drug concentrations in tissues is easy with inhaled agents delivered at defined partial pressures, but very difficult with intravenous agents. Conversely, steady-state concentrations of non-volatile drugs are easily established in water-breathing aquatic vertebrates immersed in drug solutions. Thus, Xenopus tadpoles are widely used for LoRR testing of intravenous sedative-hypnotics, but this approach is impractical for primary sedative-hypnotic screening in large numbers of drugs. In contrast, young zebrafish have proven useful for high-throughput bioassays of psycho-active drugs in libraries16,17, but have not been used to screen specifically for new sedative-hypnotics.

Here, we describe development of an approach to assess sedative-hypnotic drug effects in up to 96 zebrafish larvae simultaneously using computer-controlled stimuli and quantification of video-monitored motor responses. Automated zebrafish larva hypnosis assays based on photomotor responses perform nearly identically to manual Xenopus tadpole LoRR tests for both hypnotic drug screening and potency determinations, while requiring far less material, time, and effort. Applying this novel approach to a library of 374 organic small compounds identified two with reversible hypnotic activity. These newly-identified sedative-hypnotics were further characterized in Xenopus tadpoles and a panel of molecular targets thought to mediate general anesthetic actions. To explore translational potential, limited studies of intravenous administration in rats were also performed.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Xenopus tadpoles and frogs were purchased from Xenopus One (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and used with approval from the MGH IACUC. Adult female frogs were used as a source of oocytes for two-micro-electrode voltage clamp electrophysiology, while tadpoles were used in manual loss-of-righting reflexes experiments, as previously described18. Zebrafish (Danio rerio, Tubingen AB strain) were used with approval from the MGH IACUC according to established protocols19. Adult zebrafish were maintained in a specialized aquatic facility and mated to produce embryos and larvae as needed. Embryos and larvae were maintained in petri dishes (140 mm diameter) filled with E3 medium (in mM: 5.0 NaCl, 0.17 KCl, 0.33 CaCl2, 0.33 MgSO4, 2 HEPES at pH 7.4) in a 28.5°C incubator under a 14/10 hour light/dark cycle, until used in experiments. The density of embryos and larvae was less than 100 per dish. Experiments were performed on zebrafish larvae at up to 7 days post-fertilization (dpf). After either use in experiments or at 8 dpf, larvae were euthanized in 0.5% tricaine followed by addition of bleach (1:20 v:v). Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–400 gm) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA) and used with approval from the MGH IACUC in loss-of-righting reflexes tests following intravenous drug administration. Female rats were excluded from these studies, because their sensitivity to anesthetics varies with estrus cycle.

Anesthetics and test compounds

Etomidate was a gift from Professor Douglas Raines (MGH DACCPM, Boston, MA USA) and was prepared as a 2 mg/ml solution in 30% propylene glycol:water (v:v). Alphaxalone was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Ketamine was purchased from Mylan Pharmaceuticals (Canonsburgh, PA USA) as a 10 mg/ml aqueous solution with 0.1 mg/ml benzethonium chloride as a preservative. Dexmedetomidine was purchased from U.S. Pharmacopeia (Rockville, MD USA). Propofol, pentobarbital, atipamezole and alcohols were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO USA). A set of 11 potent GABAA receptor modulators (see Table 1) 8,9,20–22 were gifts from Prof. Erwin Sigel (Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, University of Bern, Switzerland). A chemical compound library “diversity” subset (374 compounds) was obtained from the Boston University Center for Molecular Discovery (directed by J.A.P.). Physical properties23,24 of these compounds are (mean ± sd; range): MW = 390 ± 101 (162 to 799); calculated LogP = 3.8 ± 1.6 (−0.13 to 12.9); polar surface area (Å2) = 66 ± 24 (16 to 160); H-bond donors = 0.87 ± 0.85 (0 to 5); and H-bond acceptors = 3.9 ± 1.5 (1 to 10). Library compounds were provided on 384-well plates as 0.2 micromoles dried film, and were reconstituted in 40 μL DMSO as 5 mM solutions. Examination under a dissecting microscope was used to confirm complete dissolution of each compound.

Table 1.

Potent GABAA Receptor Modulators Tested in Tadpoles and Zebrafish Larvae

| Compound # | Reference | Name of Compound in Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ramerstorfer et al.20 | CGS-9598 |

| 2 | Middendorp et al.8 | Compound 11 |

| 3 | Kopp et al.21 | Valerenic Acid Derirative-10 |

| 4 | Middendorp et al.8 | Compound 20 (Structure not shown) |

| 5 | Maldifassi et al.9 | Compound 31 |

| 6 | Maldifassi et al.9 | Compound 132 |

| 7* | PubChem Compound Database | PubChem CID: 43947938 |

| 8 | Middendorp et al.8 | Compound 67 |

| 9 | Baur et al.22 | 4-O-methylhonokiol |

| 10* | PubChem Compound Database | PubChem CID: 18593928 |

| 11* | PubChem Compound Database | PubChem CID: 3878620 |

Compounds 7, 10, and 11 have not been described in previous publications. Modulation of GABAA receptors by these compounds was confirmed by Constanza Maldifassi, PhD (Centro Interdisciplinario de Neurociencia de Universidad de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile; personal communication). Compound information and available commercial vendors can be found in PubChem Compound Database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Chemicals

Salts, buffers, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), acetylcholine (ACh), n-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), and glycine, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Loss of righting reflex assays in tadpoles and rats

General anesthetic potency was assessed in Xenopus tadpoles at room temperature (22 ºC) as previously described25. For each anesthetic concentration studied, 8 or 10 animals were studied, based on previous experience. Groups of 4 to 5 tadpoles per container were placed in aqueous solutions (20 ml per animal; Fig 1A) containing known sedative-hypnotics or experimental compounds and tested every five minutes for 30 minutes. Loss of righting reflexes (LoRR) was assessed by gently turning each animal supine using a polished glass rod. Absence of swimming and/or turning prone within 5 seconds was counted as LoRR. We recorded the LoRR count/total animals as a function of time after immersion in drug. In screening tests for hypnotic activity, tadpoles were exposed to 10 μM drug. Drugs were considered active if at least 50% of animals demonstrated LoRR after 30 min of exposure. Concentration-dependent tadpole LoRR results were analyzed based on results at 30 min. Individual binary results (1 for LoRR; 0 otherwise) were tabulated and analyzed by fitting logistic functions [Y = Max* 10ˆ(nH*log[drug])/(10ˆ(nH*log[drug]) + 10ˆ(nH*log[EC50]))] using non-linear least squares (Graphpad Prism 6.0). We report mean EC50 (95% confidence interval). After 30 minutes of drug exposure and final LoRR testing, animals were returned to clean water and observed for 24 hours in order to establish whether drug effects were reversible. In cases where animals did not survive for 24 hours after drug exposure, we repeated experiments in additional groups of animals to confirm whether toxic effects were consistently observed.

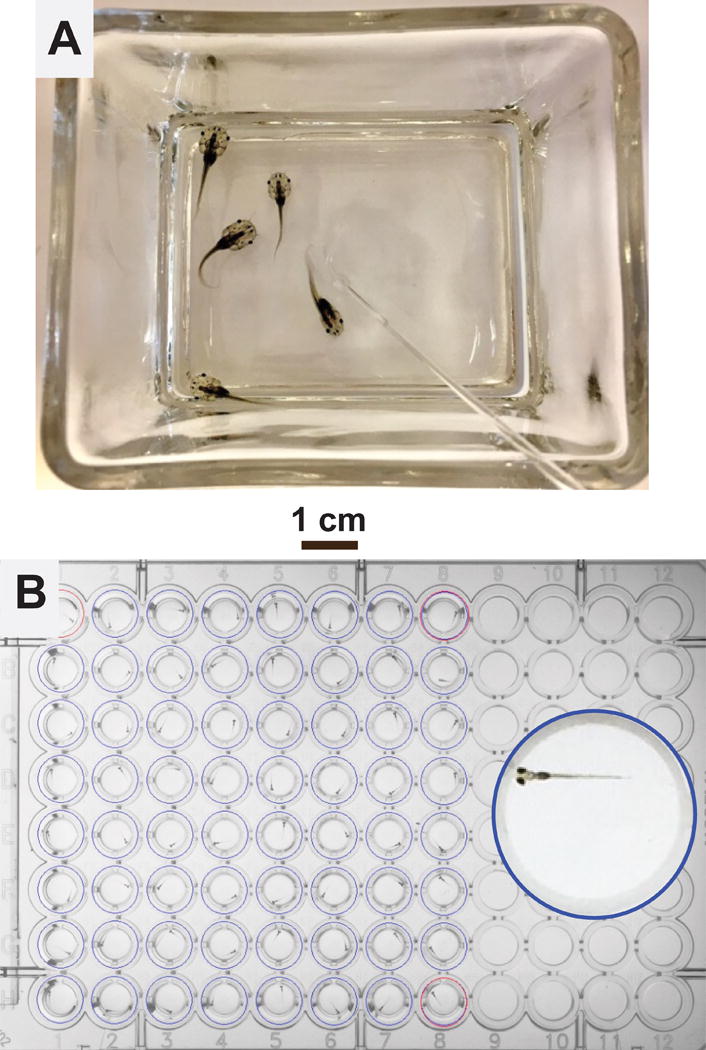

Figure 1. Tadpoles vs. Zebrafish Larvae.

A: A glass container holding 5 pre-limb bud stage Xenopus tadpoles in 100 mL water. The polished glass rod, visible in the lower right quadrant of the photograph, is used to manually turn the animals during loss-of-righting reflexes tests.

B: A 96-well plate loaded with 64 zebrafish larvae, 1 larva per well in 0.2 mL E3 buffer each. The inset shows a magnified view of one well containing a 7 dpf larva.

For two novel compounds that produced reversible sedation and hypnosis in both zebrafish larvae and tadpoles, limited initial tests of hypnotic efficacy were also performed in rats, using LoRR assays26. Rats were briefly (< 5 min) anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation in order to place a 24 gauge intravenous catheter in a tail vein. After recovery from isoflurane for at least 60 minutes in room air, rats were gently restrained. Before drug administration, intravenous cannulation was confirmed by gentle aspiration of blood and resistance-free injection of 0.25 ml normal saline. The desired dose of test drug in dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle (0.1–0.5 ml) was then injected in < 5 s, followed by a 1 ml normal saline flush. Immediately after drug delivery, rats were removed from restraint and turned supine. A rat was judged to have LoRR if it failed to right (i.e. turn itself back onto all four paws) within 5 s after being turned. Both the latency to LoRR after saline flush and the duration of LoRR, defined as the time from LoRR onset until the animal spontaneously returned to a four-paw upright stance, were measured with a stopwatch. Because our goal was to establish whether these drugs could induce hypnosis using limited available amounts of the test compounds, only one or two rats were studied at each dose.

Zebrafish Larvae Photomotor Response Assays

Using a 1000μl pipetter fitted with a cut and fire-polished tip, single zebrafish larvae (7dpf, sex indeterminate) were placed into wells of a standard 96-well plate containing 150μl E3 buffer. Known anesthetics and test compound stocks were prepared in DMSO, and then diluted in E3 buffer to 4 times the desired final concentration. A multi-pipette was used to load 50 μl of 4× solutions into wells, bringing the final volume to 200μl (Fig 1B). Final DMSO concentrations were no more than 0.2%.

Immediately after addition of drugs (< 5 min), the 96-well plate loaded with larvae was placed in a Zebrabox (Viewpoint Behavioral Systems, Montreal, Canada) and adapted at 28°C in the dark chamber for 15 min. During experiments, activity of individual larvae was recorded with an infrared video camera and analyzed using Zebralab v3.2 software (Viewpoint Behavioral Systems). Basal activity in the darkened chamber was recorded for 5-10 sec, followed by a 0.2s exposure to a 500 lux white light stimulus, and another 5-10 s in the dark. Each animal was tested in this manner up to 10 times at 3 min intervals. Zebralab software quantifies each animal’s motor activity by assessing changes in infrared image pixel intensity (on a scale of 1 to 256) of all pixels corresponding to the image area of its circular well, between sequential video sweeps (every 40 ms). An activity score is calculated by summing the absolute values of pixel intensity changes over the whole well. Activity integration is a Zebralab output that sums activity scores over multiple video sweeps during an experimentally defined epoch. For larval photomotor response (PMR) experiments, we used activity integration epochs of 0.2 to 1.0 s and normalized activity scores for 0.2 s epochs (e.g. the activity score for a 1 s epoch was reduced 5-fold).

To establish a binary PMR outcome, we calculated the mean and standard deviation for pre-stimulus basal activity (5 to 10 s per trial, up to 10 trials, normalized to 0.2 s epochs) for individual larvae. PMR for a single trial was scored as positive (1) if activity during any of the three 0.2 s epochs during and after the photic stimulus exceeded the upper 95% confidence interval (mean + 2 × sd) for basal activity. Otherwise, PMR was scored as negative (0). Cumulative PMR probabilities for each larva were calculated by pooling single trial PMR results from multiple sequential trials. For statistical analyses, results from all larvae in an exposure group were pooled. D’Agonstino & Pearson normality tests performed on cumulative PMR probabilities from studies using 8 or more animals per group indicated normally distributed results when not naturally skewed toward either 1.0 (in control conditions) or 0 (with high concentrations of hypnotics).

Screening for Hypnotic Drug Activity Using Larval Zebrafish Photomotor Responses

The hypnotic effects of compounds at 10 μM (in 0.2% DMSO) were tested in groups of 8 to 12 zebrafish larvae. Each plate included 6 to 10 test compounds, a negative control group in 0.2% DMSO, and a positive control group in 10 μM etomidate. Individual larva single trial PMR responses were tabulated for four trials, and averaged to calculate cumulative PMR probabilities. The PMR probabilities for all larvae in a drug-exposed group were combined to calculate mean and variance (SD or 95% confidence intervals) statistics. Drug-exposed group results were compared to those from the negative control (no drug) group using one-way ANOVA (GraphPad Prism 6.0) with Dunnett’s post-hoc test. Pairwise p values were calculated using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Compounds that inhibited PMR relative to control with p < 0.05 (adjusted using a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons) were studied further to establish hypnotic potency and reversibility.

To calculate the power of our drug screening approach, we performed an analysis as follows: Photomotor response experiments with no drug in 96 larvae tested four times each revealed mean cumulative PMR probability of 0.89 with standard deviation of 0.17 (see Results). With 8 larvae per group, and α = 0.005 (applying a Bonferroni correction for 10 comparisons to each control) in a two-tailed t-test, a power calculation (using G*Power v 3.08) indicated 0.95 probability (1 - β) of detecting a 0.45 absolute (50% relative) reduction in PMR probability (effect size = 2.6).

Concentration-Response Studies Using Larval Zebrafish Photomotor Responses

Larvae in groups of 8 to 12 were exposed to either control (no drug) or varying concentrations of drug. When drug stock drug solution (usually > 100 mM) was in DMSO, all control and final drug solutions included the same DMSO concentrations (≤0.1%). Cumulative PMR probability for each animal was established as described above from four trials. Results (mean with 95% confidence interval) for all animals in each exposure group were calculated and plotted against log[drug, M]. Concentration-dependent PMR inhibition was analyzed by fitting logistic functions to pooled PMR probability data using non-linear least squares (see above tadpole LoRR analysis). We report mean hypnotic EC50 (95% confidence interval).

Drug Effects on Spontaneous Activity of Zebrafish Larvae

Spontaneous activity data from pre-stimulus baseline periods was used to assess the sedative potency of tested drugs. Activity integration values for all 25 0.2 s pre-stimulus epochs per trial were pooled across all four trials and all animals in a drug exposure group. These data were used to calculate mean and variance (SD or 95% CI) statistics. Combined spontaneous activity data were normalized to the mean value for no-drug controls on the same plate. Spontaneous activity in drug-exposed larvae were compared to no-drug controls and drug-dependent inhibition of spontaneous activity was analyzed using logistic fits, as described above for PMR results.

Drug Effect Reversibility in Zebrafish Larvae

The reversibility of PMR inhibition was tested in zebrafish larvae exposed to the highest drug concentrations used in concentration-response studies. These larvae were carefully transferred to petri dishes containing fresh E3 medium and placed in an incubator used to maintain embryos and larvae. Larvae were repeatedly tested for motor reactivity to a gentle tap on the petri dish at 15 and 30 minutes after drug exposure, and again 24 hours later. In cases where drug-exposed zebrafish larvae did not survive for 24 hours, additional groups of animals were tested to establish whether toxic effects were reproducible.

Library Hit Validation

Active library compounds from zebrafish screening were validated using new freshly-supplied aliquots of the original stock from BU-CMD. Compound identity and purity was confirmed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) with a “passing” threshold of 90% purity as measured using evaporative light scattering detection (ELSD). Activity and potency of the fresh aliquots were confirmed in zebrafish PMR assays. Tadpole and rat LoRR assays were performed using freshly prepared compounds, generated using published methods, at >98% purity as determined by NMR and UPLC-MS analysis. CMLD003237 was prepared according to the published protocol, which produces the (+) enantiomer in 90% enantiomeric excess and >11:1 diastereomeric ratio27. CMLD003237 prepared for tadpole and rat studies was further purified by flash column chromatography to >20:1 diastereomeric ratio. CMLD006025 and its enantiomer CMLD011815 were prepared according to published protocols28–30.

Ion Channel Expression

DNA plasmids encoding human N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (NMDAR) subunits NR1B and NR2A were obtained from Prof. Steven Treistman (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA USA). Plasmids encoding the human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nnAChR) subunits α4 and β2 were obtained from Prof. James Patrick (Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA). Plasmids encoding human HCN1 channels were a gift from Prof. Peter Goldstein (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY USA). Human α1, β3, and γ2 GABAA receptor subunits were inserted into pCDNA3.1 expression vectors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Human glycine receptor α1 subunit cDNA was cloned from whole brain mRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using PCR and inserted into pCDNA3.1. Capped messenger RNAs (mRNAs) were transcribed in vitro using mMessage Machine kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For NMDA receptor studies, oocytes were injected with 15ng in 1:1 mRNA mixtures of NR1B:NR2A; for nnAChR studies, 15 ng of 1α4:1β2; for GABAA receptors, 5ng total of 1α:1β:5γ; for HCN1 channels, 15 ng HCN1; and for glycine receptors, 0.015 ng α1 subunit mRNA. Oocytes were incubated in ND96 solution (in mM: 96 NaCl, 4 KCl, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.0, and HEPES 5, pH 7.5) supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamicin at 18°C for 48-96 hours before electrophysiology.

Voltage-clamp electrophysiology

Two micro-electrode electrophysiology techniques for GABAARs, NMDARs and nnAChRs have been described previously31,32. Experiments were performed at 20 to 22 °C in ND96 buffer (Mg2+-free ND96 was used in NMDA receptor experiments). Positive modulation of α1β3γ2L GABAA receptors was assessed using receptor activation with EC5 GABA (3 μM). Positive modulation of glycine α1 receptors was assessed with EC5 glycine (1 μM). Inhibition of α4β2 neuronal nAChRs was tested using maximal activation conditions (1mM acetylcholine). Inhibition of NMDA receptors was tested using maximal activation (100μM NMDA plus 10μM glycine) in Mg2+-free ND96. Voltage-dependent HCN1 currents were stimulated using a previously described voItage-jump protocol, starting and ending at a holding level of −40 mV33. In all cases, oocytes were pre-exposed to drug for 30s before receptor activation. Voltage-clamped currents were low-pass filtered at 1 kHz, digitized at 100 Hz, recorded, and analyzed offline to evaluate baseline-corrected peaks. Peak currents were normalized to responses measured in the same cell without drug. All hypnotic compounds were tested at 2 × EC50 for loss-of-righting-reflexes (LoRR) in zebrafish or tadpoles. Drug effects on GABAA receptors were compared to those produced by 3.2 μM etomidate (2 × EC50) in the same cells. Drug effects on glycine receptors and HCN1 channels were compared to 4.5 μM propofol (2 × EC50). Drug effects in NMDA and nnACh receptors were compared to 120 μM ketamine (2 × EC50) in the same cells. The number of electrophysiological experiments needed to detect either a doubling of GABA or glycine receptor EC5 responses (an effect size of about 3) or 30% inhibition of maximal responses in other channels (also an effect size of about 3) was determined to be 4, based on power analysis (using G*Power v 3.08) for a two-tailed t-test with 1-β = 0.8 and α =0.025 (using a Bonferroni correction for 2 comparisons). Thus, at least four cells were used for each experimental condition in each receptor type. The number of cells in specific experiments is reported in figure legends. One way ANOVA was applied for statistical comparisons and Student’s t-tests were used to calculate pairwise p-values.

Atipamezole reversal tests

To test compounds for α2 adrenergic receptor agonist activity, we used the selective α2 adrenergic receptor antagonist atipamezole, at 10 nM and tested for reversal of hypnosis in groups of zebrafish larvae (n = 8 or 12 per group). The 10 nM atipamezole concentration was chosen based on concentration-response studies in combination with 2.5 × EC50 dexmedetomidine (1.0 μM) and control experiments with other sedative-hypnotics that confirmed specificity (see Results).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical methods used in drug screening and concentration-response analysis are described above. In comparing zebrafish PMR inhibition and tadpole LoRR results, the concordance of binary (significant inhibition or not) drug screening outcomes was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa with Fisher’s exact test for statistical significance. Multiple drug potencies (mean EC50s or log[EC50s]) in zebrafish vs. tadpoles were compared with Pearson correlations. Drug effects on ion channels were compared to positive and negative controls using ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons and pairwise p values were calculated using two-tailed paired Student’s t-tests. These analyses and non-linear least squares logistic fits were performed using Graphpad Prism 6. Results are reported as mean ± sd or 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Some graphs display unidirectional 95% confidence intervals, for clarity. In these cases, the confidence intervals are symmetrical around the mean. There were no missing data associated with statistical analyses. No outlier data were detected in our analyses.

Results

Development of a Photomotor Response Assay using Zebrafish Larvae

Our initial goal was to develop a high-throughput assay for hypnotic drug activity based on stimulus-response in zebrafish larvae, and to validate it against standard Xenopus tadpole LoRR tests. Based on prior published work with zebrafish larvae16,34,35, we tested both acoustic/vibration and photic stimuli in larvae ranging in age from 4 to 7 dpf. Motor responses to acoustic/vibration stimuli (taps delivered with a solenoid) were consistent under control conditions, but were not fully extinguished by 10 μM etomidate or 10 μM propofol (data not shown), both of which fully inhibit righting reflexes in pre-limb bud stage Xenopus tadpoles. Brief flashes of bright (500 lux) white light also elicited motor responses in dark-adapted zebrafish larvae (Fig 2A). The magnitude of activity after photic stimuli was smaller and less consistent than that after tap stimuli, but was fully extinguished by either etomidate or propofol at 10 μM. Experiments in larvae from 3 to 7 dpf indicated that PMRs were more consistent in older animals with more mature visual systems (data not shown). All subsequent experiments used 7 dpf larvae. We used a single animal per well in 96-well plates, to avoid activity triggered by contact with other moving animals.

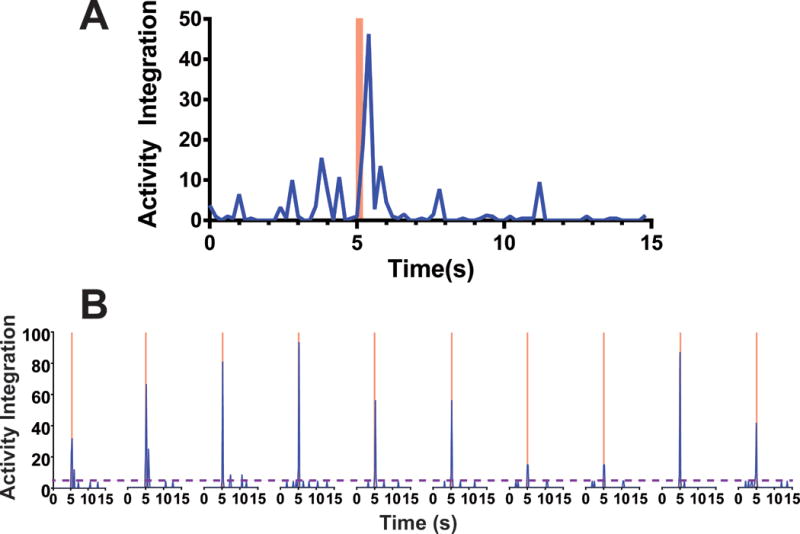

Figure 2. Photomotor Responses in 7 dpf Zebrafish Larvae.

Activity integration is a Zebralab experimental output totaling the number and intensity of pixel changes in a designated image area between sequential infrared video sweeps during a 0.2 s experimental epoch (each epoch includes 5 video sweeps lasting 0.04 s). A) Average activity integration for 8 larvae in E3 buffer with 0.2% DMSO (control conditions) is plotted at 0.2 s intervals during a single photomotor response trial. A 500 lux white light stimulus was activated at 5 s and discontinued at 5.2 s (pink bar). Note that activity dramatically increased during the photic stimulus and diminished within 1 s. B) Activity of a single larva during a series of 10 photomotor response trials, with 3 minute intervals between trials, is shown. Pink bars indicate photic stimuli. The purple dashed line indicates the upper 95% confidence interval for mean baseline activity during all ten pre-stimulus epochs (5 s each). Activity during and following photic stimuli was consistently above the 95% baseline threshold in all trials, while varying in magnitude from trial to trial.

To quantify hypnotic drug effects on the PMR, we first tried averaging the peak activity level during and after light stimulus for drug-exposed groups and normalizing to the non-drug control group. However, stimulated activity levels varied widely among animals and among repeated trials in single animals (e.g. Fig 2B). Baseline motor activity also varied among larvae and was inhibited by increasing sedative-hypnotic drug concentrations. To minimize these sources of variability and mimic tadpole LoRR tests, we established a rigorous binary outcome for each PMR trial. Each larva’s motor activity in three 0.2 s epochs both during and immediately after photic stimulus was compared to the upper 95% confidence interval for spontaneous activity in all 0.2 s epochs during pre-stimulus baseline periods (Fig 2B). By testing each animal in multiple trials, we calculated cumulative PMR probabilities. Drug effects on spontaneous motor activity, as a measure of sedation, were independently analyzed (see below).

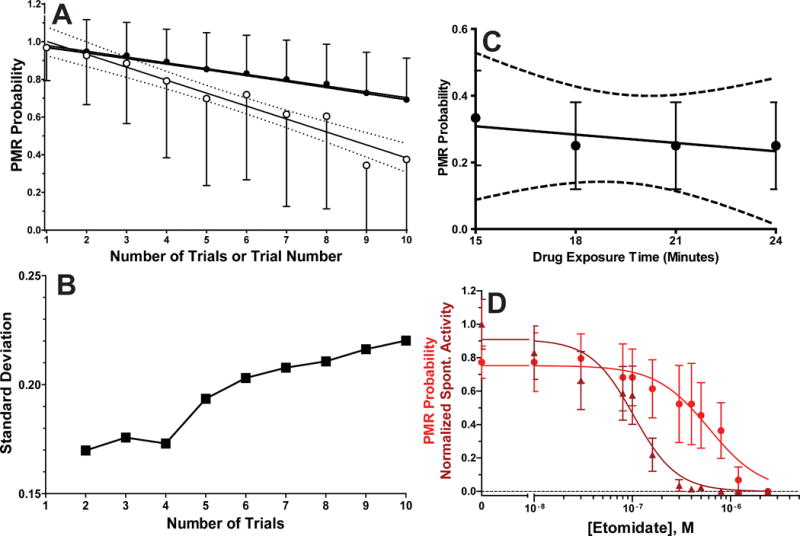

We tested the effect of repeating PMR trials up to 10 times using 96 zebrafish larvae, aiming to minimize outcome variance. Under control conditions, desensitization to the light stimulus was observed with repeated trials. This effect weakened as the inter-trial interval increased from 30 s to 3 min. However, intervals of 3 to 12 min all produced similar drops in PMR probability from over 90% in the first trial to less than 60% at the 10th trial (Fig 3A; open symbols). Cumulative PMR probability with increasing numbers of trials at 3 min intervals is also shown in Fig 3A (solid symbols). Linear regression analysis indicated a non-zero slope for cumulative PMR probability from four trials (slope = −0.0247 ± 0.0022; p = 0.0082) to 10 trials (slope = −0.0301 ± 0.0009; p < 0.0001). The cumulative PMR probability variance (standard deviation) remained stable for up to four trials, and then monotonically increased with each added trial as the effects of desensitization grew (Fig 3B). Cumulative PMR probability associated with four trials was only 7% lower than that from the initial control trial. Thus, we used four trials with a 3 minute interval in subsequent PMR experiments. With this approach, desensitization to repeated photic stimuli was absent in larvae exposed to hypnotic concentrations of etomidate (Fig 3C; slope = −0.008 ± 0.0195; p = 0.67; n = 12) or equi-hypnotic solutions of dexmedetomidine (slope = −0.002 ± 0.012; p = 0.85; n = 12), ketamine (slope = −0.002 ± 0.019; p = 0.88; n = 12), alphaxalone (slope = 0.013 ± 0.019; p = 0.48; n = 12), tricaine (slope = −0.002 ± 0.015; p = 0.86; n = 12) and butanol (slope = −0.002 ± 0.019; p = 0.88; n = 12). These results indicate both that all these sedative-hypnotics inhibit mechanisms underlying PMR desensitization to repeated stimuli and that a 15 minute drug exposure before PMR testing establishes steady-state drug concentrations in larval nervous tissues.

Figure 3. Photomotor Response Probability and Variance with Repeated Trials are Affected by Sedative-Hypnotic Drugs.

A) Photomotor responses (PMRs) were tested ten times with 3 minute intervals between trials in larvae (n = 96) in E3 buffer with 0.2% DMSO (no-drug control conditions). The single trial PMR probability (open circles; mean ± sd) monotonically decreases with each repetition (trial number) and cumulative PMR probability (solid circles; mean ± sd) decreases with the number of included trials, as larvae desensitize to the photic stimulus. Solid lines through the plotted points are linear regression fits, and dashed curves are 95% confidence intervals for the fitted lines. The single PMR trial slope (mean ± sd) = −0.069 ± 0.0062 and cumulative PMR trial slope = −0.0301 ± 0.0009. Both slopes are non-zero (p < 0.0001 by linear regression). A linear fit to cumulative PMR probabilities for only the first four trials gives slope (mean ± sd) = −0.025 ± 0.0022, which is also non-zero (p = 0.0082). B) Standard deviations from cumulative PMR probability data in panel A are plotted against trial number, showing that variance increases after more than 4 trials. C) Single PMR probability trial results (mean ± sd; n = 16) in a group of zebrafish larvae exposed to 1.5 μM etomidate and tested four times at 3 minute intervals are plotted against drug exposure time, which includes a 15 minute pre-test exposure period. The fitted (solid) line to data has a slope (mean ± sd) = −0.008 ± 0.020, which is not significantly different from zero (p = 0.67 by linear regression). The 95% confidence intervals for the fitted line are drawn as dashed lines. D) An example of experimental results showing etomidate-dependent inhibition of both spontaneous activity (dark red triangles) and cumulative PMR probability (red circles). Points represent mean with 95% confidence intervals for 10 animals per concentration, each tested in 4 PMR trials at 3 minute intervals. Lines through data represent logistic fits. Inhibition of spontaneous activity is characterized by EC50 = 0.10 μM (95% CI = 0.080 to 0.12 μM) and nH = 2.0 ± 0.37. Inhibition of PMR probability is characterized by EC50 = 0.6 μM (95% CI = 0.45 to 0.81 μM) and nH = 1.6 ± 0.40.

The optimized PMR assay provided two measures of concentration-dependent drug action in a single experiment: sedation measured from inhibition of spontaneous motor activity, and hypnosis from inhibition of the PMR. Fig 3D shows results and logistic analyses from combined data in groups of zebrafish larvae exposed to varying concentrations of etomidate. Sedation by etomidate requires 6-fold lower concentrations than hypnosis, while Hill slopes are comparable for both effects.

Validation of PMR Inhibition Against Tadpole Loss-of-Righting-Reflexes

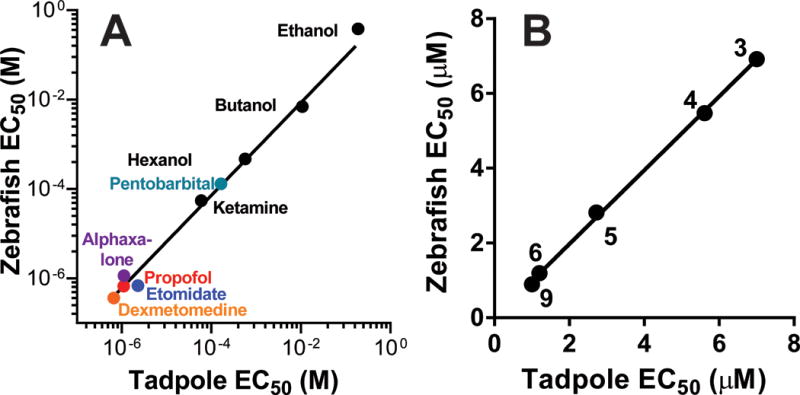

Our first validation of the zebrafish larva PMR assay used a set of 9 sedative-hypnotic compounds with previously published potencies in tadpole LoRR tests: ethanol36, butanol36, hexanol36, ketamine37, propofol38, etomidate39, pentobarbital40, dexmedetomidine41, and alphaxalone42. These hypnotics are characterized by LoRR EC50s ranging from low micromolar to high millimolar and effects at a variety of molecular targets14,43. PMR concentration-response experiments (n = 10 larvae per condition) showed that for all drugs except dexmedetomidine, EC50 for PMR inhibition in zebrafish larvae was within a factor of 3 of the published EC50 for tadpole LoRR (Fig 4A). The large discrepancy between the published LoRR EC50 for dexmedetomidine (mean ± sd = 7 ± 1.1 μM)41 and the PMR EC50 (mean = 0.4.μM) led us to re-test dexmedetomidine in Xenopus tadpoles, resulting in EC50 = 0.66 μM (95% CI = 0.28 to 1.56 μM; n = 10 per concentration). The Pearson correlation coefficient for drug potencies in zebrafish versus tadpoles (using our value for dexmedetomidine in tadpoles) was 0.999 (p < 0.0001), reflecting remarkably close agreement.

Figure 4. Correlation of Hypnotic Potencies in Tadpoles and Zebrafish.

A) Zebrafish photomotor responses were reversibly inhibited by known anesthetics with potencies closely correlated to published tadpole LoRR EC50s (log[EC50] Pearson correlation r=0.999, R2=0.998, p < 0.0001). Citations for tadpole EC50s are: ethanol36, butanol36, hexanol36, ketamine37, propofol38, etomidate39, pentobarbital40, and alphaxalone42. Dexmedetomidine EC50 in tadpoles was determined by the authors. B) In a set of 5 GABAA receptor modulators displaying potent hypnotic activity in tadpole screening tests (see Table 2), a very strong correlation is observed in comparison to potencies in zebrafish (EC50 Pearson correlation r=0.9995, R2=0.999, p < 0.0001). Table 1 provides citations for the specific compounds, indicated by label number.

To test the utility of zebrafish PMRs in screening new potent hypnotic compounds, we used a second group of 11 compounds that were all recently identified as potent modulators of GABAA receptors (Table 1), and that had been tested for hypnotic activity and potency using tadpole LoRR tests9. Results of previous tadpole LoRR tests at 10 μM identified 5 compounds with hypnotic activity and six without. Screening these 11 compounds for hypnotic activity using zebrafish PMR assays produced identical positive and negative screening results (Table 2). The concordance of the two approaches was 100% with Cohen’s Kappa = 1.000 (p = 0.0022 by Fisher’s exact test).

Table 2.

Zebrafish vs. Tadpole Screening for Hypnotic Activity in GABAA Receptor Modulators

| Zebrafish PMR |

Tadpole LoRR | |||

| Yes | No | Total | ||

| Yes | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| No | 0 | 6 | 6 | |

| Total | 5 | 6 | 11 | |

A set of 11 potent GABAA receptor modulators (see Table 1 for details and references) were scored as demonstrating or lacking hypnotic activity at 10 μM. Manual tadpole LoRR tests were scored as positive if 5 or more of 10 animals lost righting reflexes after 30 min of immersion in test solution. Zebrafish larvae PMR inhibition was performed on 8 animals per compound with 5 or 6 experimental drugs simultaneously tested against a negative control (E3 buffer with 0.2% DMSO) and a positive control (10 μM etomidate). The PMR outcomes were scored based on ANOVA comparisons to the negative control group (p < 0.05). Concordance between zebrafish larva PMRs and tadpole LoRRs for identifying hypnotics among this group of compounds was 100% (Cohen’s Kappa = 1.000; p = 0.0022 by Fisher’s exact test).

Potencies (EC50s) for the five hypnotic GABAA receptor modulators, in both tadpoles and zebrafish agreed remarkably closely (Fig 4B; Pearson correlation r = 0.999; p < 0.0001).

Discovery of new sedative-hypnotic compounds in a drug library screen

Our second major aim was to use zebrafish larvae PMR assays to screen for new sedative-hypnotic compounds in a drug library. We obtained a library of 2651 compounds from the Boston University Center for Medical Discovery (Boston, MA USA), including a “diversity set” of 374 compounds selected randomly to represent the variety of chemotypes in the larger collection. We screened the diversity set (DS), using 8 larvae per compound, comparing PMR results for up to 10 test compounds to a negative (no drug) control group on the same plate. We found two compounds that, at 10 μM, inhibited PMR probability in zebrafish larvae by more than 50%. Larvae exposed to the first of these compounds (DS68; CMLD003288) at 10 μM died within 24 hours of exposure. After confirmation of this toxicity in a second group of zebrafish larvae, we discontinued study of this compound. A second active compound (DS85; CMLD003237; methyl ((3S,4R,E)-4-nitro-1-phenylpent-1-en-3-yl)carbamate) induced fully reversible PMR inhibition in zebrafish larvae at 10 μM (Fig 5A). A third compound (DS151; CMLD006025; (1R,4S,4aS,9aS,11R)-11-hydroxy-3-isopropyl-11-methyl-4,4a,9,9a-tetrahydro-1H-1,4-ethanofluoren-10-one) produced only about 30% inhibition of PMR when screened at 10 μM (Fig 5B). However, the screening data revealed that this compound inhibited spontaneous motor activity by over 90% at 10 μM (Fig 5C). Re-testing CMLD006025 at 20 μM revealed an 85% reduction of control PMR probability (mean ± sd = 0.13 ± 0.21 vs 0.83 ± 0.13; p < 0.0001; n = 8 per group).

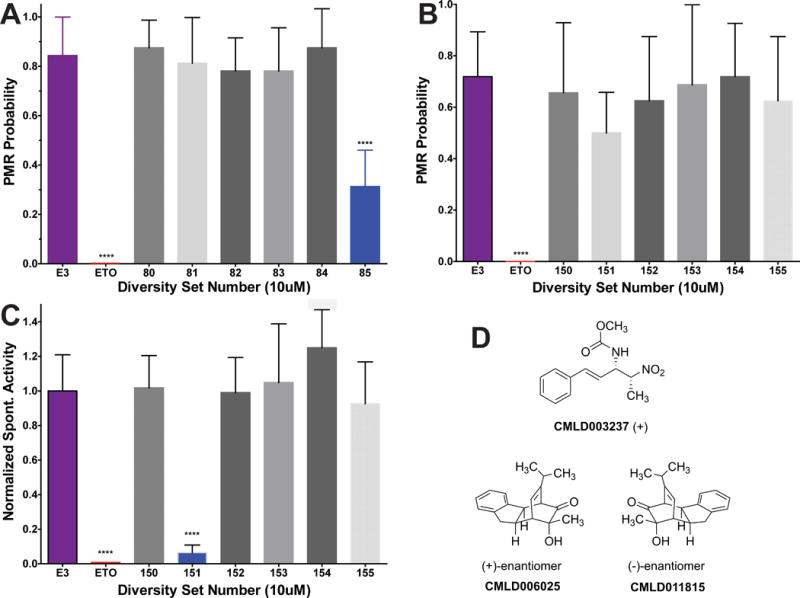

Figure 5. Discovery of Novel Sedative-Hypnotics Using Zebrafish Larvae Photomotor Responses.

A-C) Bars represent cumulative photomotor response (PMR) probability or normalized spontaneous activity from 4 trials at 3 min intervals (mean with symmetrical 95% CI; n =8). A) Screening PMR results from an experiment including negative (E3 with 0.2% DMSO) and positive (10 μM etomidate; ETO) control groups, and 6 groups of larvae exposed to test compounds at 10 μM. Diversity Set #85 (DS85; CMLD003237) inhibits larval photomotor responses by over 60% (p < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t-test). B) Screening PMR results for DS150 through DS155 are shown. Note that DS151 (CMLD006025) does not significantly inhibit PMR probability (p = 0.045 by unpaired Student’s t-test, above the p = 0.0024 significance threshold after Bonferroni correction for 7 comparisons). C) Spontaneous activity, normalized to that of the negative control group from the same experiment shown in panel B. DS151 (CMLD006025) inhibited spontaneous activity by over 90% (p < 0.0001 by Student’s t-test). D) Chemical structures of CMLD003237, CMLD006025, and CMLD011815, the (-)- enantiomer of CMLD006025, are shown. **** p < 0.0001.

Characterization of new sedative-hypnotics

Physical properties of CMLD003237 are MW = 264.1 daltons; calculated LogP = 2.5; polar surface area = 81.5 Å2; 1 H-bond donor; and 3 H-bond acceptors. Concentration-dependent studies of CMLD003237 in zebrafish larvae revealed EC50 = 8 μM for inhibition of spontaneous activity and EC50 = 11 μM for inhibition of PMR (Fig 6A). A second fresh sample of CMLD003237 was re-tested to confirm activity in zebrafish, and a newly synthesized batch was used to test hypnotic effects in Xenopus tadpoles. CMLD003237 at up to 30 μM reversibly inhibited tadpole righting reflexes, with an EC50 of 12 μM (Fig 6B), close to the value for PMR inhibition. Tadpole LoRR results also confirm that CMLD003237 inhibits responses to multiple sensory stimuli.

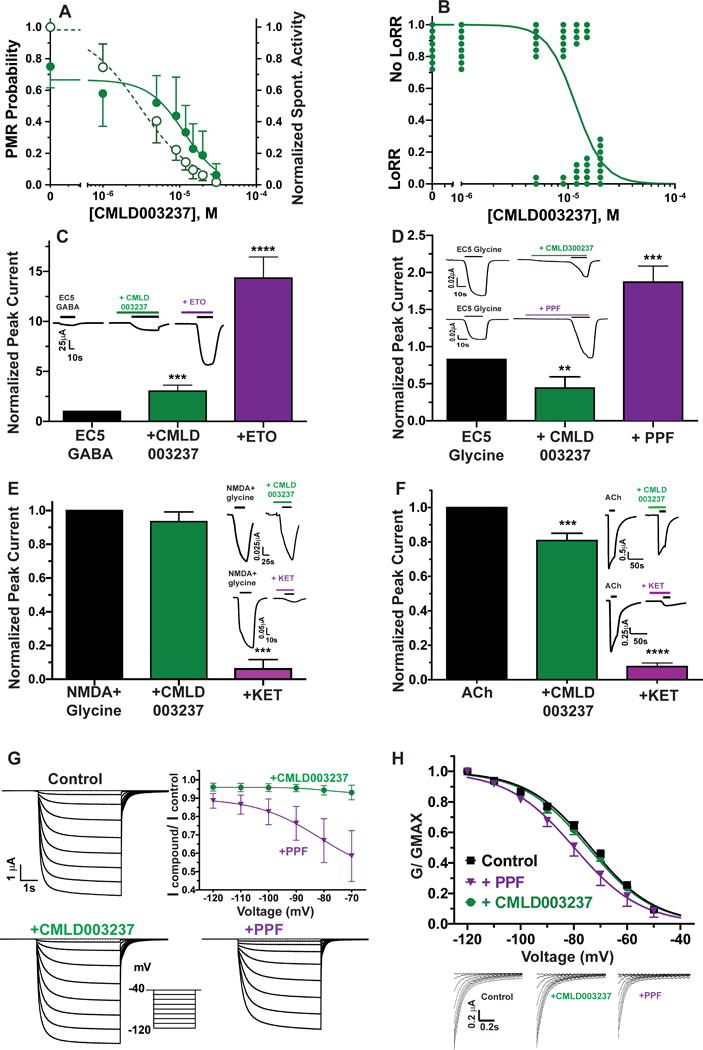

Figure 6. Characterization of CMLD003237 in zebrafish larvae, Xenopus tadpoles, and ion channels.

A) Points represent mean with 95% CI for zebrafish larvae (n ≥ 8 per group) photomotor response probability (solid circles) and normalized spontaneous activity (open circles). Lines are logistic fits. PMR inhibition EC50 = 11 μM (95% CI = 8.2 to 16 μM). Spontaneous activity inhibition EC50 = 8 μM (95% CI = 6.1 to 10.5 μM). B) Tadpole LoRR results (n = 8 per group) are shown as binary outcomes. The line is a logistic fit with EC50 = 12 μM (95% CI = 9.6 to 14.3 μM). C to F) Bars represent control-normalized ion channel currents (mean with symmetrical 95% CI) measured in Xenopus oocytes. Currents in the presence of CMLD003237 or comparison drugs, both at ≈ 2 × hypnotic EC50, were normalized to paired control currents in the same oocyte, and outcomes with drugs were compared to controls using one way ANOVA. Panel insets show examples of paired control vs. drug oocyte currents. C) Bars represent control-normalized EC5 GABA-induced currents through human α1β3γ2L GABAA receptors. CMLD003237 (22 μM) enhanced currents elicited with EC5 GABA (3 μM) about 3-fold (p = 0.0007; n = 5). An equi-hypnotic etomidate solution (ETO; 3.2 μM) enhanced EC5 currents about 14-fold (p < 0.0001; n = 5). The inset shows currents recorded under all three conditions in one oocyte. D) Bars represent control-normalized EC5 currents through human glycine receptor α1 receptors. CMLD003237 (22μM) inhibited currents elicited with EC5 glycine (1 μM) about 50% (p = 0.0013; n = 4). An equi-hypnotic propofol solution (PPF; 4.5 μM) enhanced EC5 glycine currents 1.9-fold (p = 0.0010; n = 4). E) Bars represent control-normalized peak currents through human NR1A/2B NMDA receptors. CMLD003237 (22 μM) does not affect control currents elicited with 100 μM NMDA + 10 μM glycine (p = 0.32; n =6), while an equi-hypnotic ketamine solution (120 μM) inhibits control currents by about 95% (p = 0.0002; n = 4). F) Bars represent control normalized peak currents through human α2β4 neuronal nicotinic ACh receptors. CMLD003237 (22 μM) inhibited control currents elicited with 1 mM ACh by about 20% (p < 0.0001; n = 9). Equi-hypnotic ketamine (120 μM) inhibited control currents by over 90% (p < 0.0001; n = 8). G) Plotted symbols represent control-normalized peak currents (mean with 95% CI) through human HCN1 receptors. Raw currents from a single oocyte studied under control conditions, with CMLD003237, and with propofol (PPF) are displayed along with an inset showing the voltage-jump activation protocol. CMLD003237 (22 μM; n = 8) inhibited control currents by less than 10% at all test voltages. Propofol (4.5 μM; n = 5) inhibited HCN1 currents by up to 40% in a voltage dependent manner (p < 0.0001 versus CMLD003237 at −70 mV). H) Current traces are tail currents recorded at −40 mV from panel G, normalized to the tail current amplitude following activation at −120 mV. Normalized tail current amplitudes (G/Gmax) are also plotted against activation voltage (n = 8 oocytes for CMLD003237 and 5 oocytes for propofol). Lines through these data represent nonlinear regression fits to Boltzmann equations. Fitted propofol control V50 [mean (95%CI) = −79.9 (−81.0 to 78.8)] differs from control [−73.6 (−72.9 to −74.3); p < 0.001 by F-test]. Fitted CMLD003237 V50 [−74.6 (−73.9 to −75.4)] did not differ from control (P= 0.142 by F-test). ETO: etomidate; KET: ketamine; ACh: acetylcholine chloride; PPF: propofol.

** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001.

To investigate possible molecular mechanisms underlying the sedative-hypnotic actions of CMLD003237, we tested effects of hypnotic concentrations (2 × PMR EC50 = 22 μM) on the activity of various neuronal receptors that are sensitive to potent sedative-hypnotic drugs and also likely mediators of their effects. CMLD003237 modulated α1β3γ2L GABAA receptors, enhancing EC5 GABA-elicited currents by a factor of 3.0 ± 0.50 (Fig 6C; mean ± sd; n =5; p < 0.0001 by one way ANOVA). For comparison, an equipotent concentration of etomidate (3.2 μM) produced much more gating enhancement in GABAA receptors (14 ± 1.7-fold; mean ± sd; [95% CI = 12.2 to 16.5]; n = 5; p < 0.0001 vs. both control and CMLD003237). CMLD003237 inhibited glycine α1 receptor currents by around 50%, in contrast to positive modulation by propofol (Fig 6D). CMLD003237 did not affect the activity of NR1B/NR2A NMDA receptors (Fig 6E) and inhibited human α4β2 neuronal nicotinic ACh receptors by around 20% (Fig 6F). CMLD003237 inhibited HCN1 currents less than 10% (Fig 6G), but produced no shift in voltage sensitivity (Fig 6H).

To determine whether CMLD003237 acted via α2 adrenergic receptors, we tested whether the selective inhibitor atipamezole reversed its hypnotic effects in zebrafish larvae. To establish valid conditions for these experiments, zebrafish were first exposed to dexmedetomidine at 2.5 × EC50 (1.0 μM; Fig 7A) combined with varying concentrations of atipamezole (0.3 nM to 300 nM). This experiment identified 10 nM as the lowest atipamezole concentration that fully reverses dexmedetomidine hypnosis. Furthermore, 10 nM atipamezole alone produces no change in zebrafish larvae PMR probability and no reversal of hypnosis induced with various anesthetics that act through other mechanisms (Fig 7B). Atipamezole produced no reversal of CMLD003237-induced hypnosis (Fig 7B).

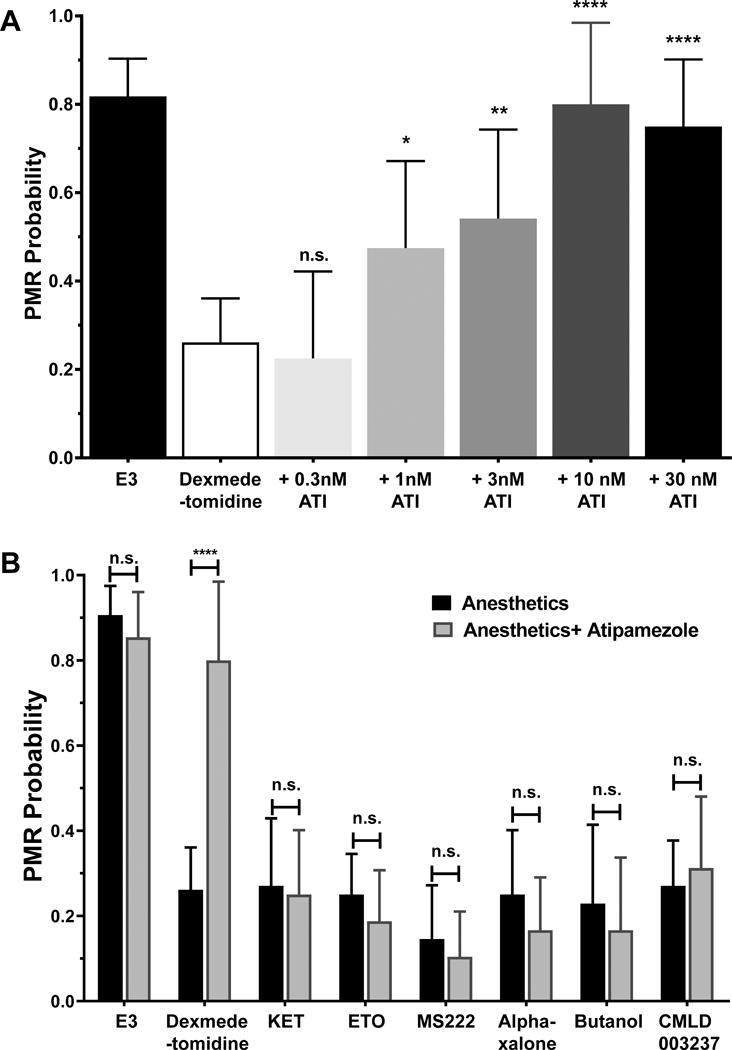

Figure 7. Atipamezole reversal of zebrafish photomotor responses is a specific test for α2 adrenergic receptor agonism.

A) Atipamezole reverses photomotor response (PMR) inhibition by 1.0 μM (2.5 × EC50) dexmedetomidine. Each bar represents mean and symmetrical 95% CI of cumulative PMR probability in groups of 12 zebrafish larvae, each tested in four trials. One way ANOVA was used to compare the dexmedetomidine group to those exposed to atipamezole. Atipamezole at 10 nM or higher concentrations fully reverses dexmedetomidine hypnosis (p < 0.0001 vs. dexmedetomidine alone). B) Atipamezole at 10 nM does not reverse photomotor response inhibition by other sedative-hypnotics. Each bar represents mean and 95% CI of PMR probability in groups of 8 zebrafish larvae, each tested in four trials. The black bars show the effect of each hypnotic drug at 2.5 × EC50 and the paired gray bar shows the effect of the same drug combined with 10 nM atipamezole. Atipamezole alone does not affect the control PMR probability (E3 buffer; p = 0.37), nor does it reverse the hypnotic effects of ketamine (KET; p = 0.84), etomidate (ETO; p = 0.38), tricaine (MS222; p = 0.58), alphaxalone (p = 0.36), butanol (p = 0.84), or CMLD003237 (p = 0.65). ATI = atipamezole; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; **** p < 0.0001.

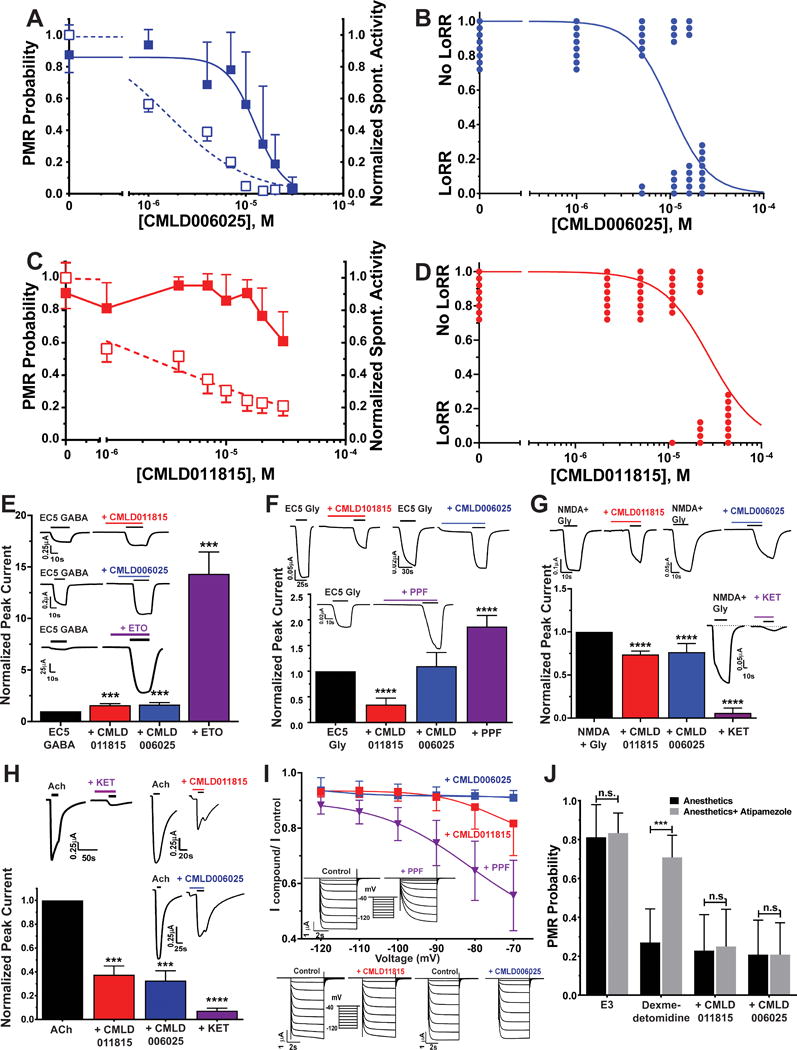

Properties of CMLD006025 are MW = 254.1 daltons; calculated LogP = 3.0; polar surface area = 37.3 Å2; 1 H-bond donor; and 2 H-bond acceptors. CMLD006025 was tested for its concentration-dependent inhibition of PMRs in zebrafish larvae (Fig 8A) and tadpole LoRRs (Fig 8B), resulting in similar EC50s of 13 μM and 10μM, respectively. Review of the BU-CMD library data revealed that CMLD006025 is a highly pure enantiomer and that its mirror image enantiomer was another library compound, CMLD011815. The PMR inhibitory potency of CMLD011815 (EC50 > 30 μM; Fig 8C), was lower than that of CMLD006025. LoRR tests in Xenopus tadpoles confirmed that CMLD006025 was more potent than CMLD011815 (Fig 8D).

Figure 8. Characterization of CMLD006025 and CMLD011815 in Zebrafish Larvae, Xenopus Tadpoles, and Molecular Targets.

A) CMLD006025 inhibition of zebrafish larvae photomotor response (PMR) and spontaneous activity. Points represent mean with symmetric 95% CI (n = 12 per group) and lines are logistic fits. PMR inhibition (solid squares): EC50 = 13 μM (95% CI = 9.9 to 16 μM). Spontaneous activity inhibition (open squares): EC50 = 1.6 μM (95% CI = 1.2 to 2.1 μM). B) Tadpole LoRR results in the presence of CML006025 (n = 8 per group), shown as binary outcomes. The line is a logistic fit with EC50 = 10.1 μM (95% CI = 7.2 to 14.1 μM). C) CMLD011815 weakly inhibits larval zebrafish PMRs at concentrations above 10 μM (solid squares; mean with 95% CI; n = 16 per group). A logistic fit to PMR data did not converge. CMLD011815 inhibition of normalized spontaneous activity is plotted as open squares (mean with 95% CI) with logistic fit EC50 = 2.3 μM (95% CI = 1.4 to 3.9 μM). D) Tadpole LoRR results in the presence of CML011815 (n = 8 per group), shown as binary outcomes. The logistic fit EC50 is 28 μM (95% CI = 18 to 49 μM). E to H) Bars represent control-normalized ion channel currents (mean with symmetric 95% CI) measured in Xenopus oocytes. Currents in the presence of drugs at ≈ 2 × hypnotic EC50 were normalized to paired control currents in the same oocyte, and outcomes with drugs were compared to controls using one way ANOVA. Panel insets show examples of paired control vs. drug oocyte currents. E) Bars represent control-normalized EC5 GABA-induced currents through human α1β3γ2L GABAA receptors. CMLD011815 and CMLD006025 (both at 26 μM) similarly enhanced currents elicited with EC5 GABA (3 μM) by about 60% (p < 0.001 vs. control; n = 5, for both drugs). An equi-hypnotic etomidate solution (ETO; 3.2 μM) enhanced EC5 currents about 14-fold (p < 0.0001; n = 5). F) Bars represent control-normalized currents through human glycine α1 receptors. CMLD011815 (26 μM) inhibited currents elicited with EC5 glycine (1 μM) by about 65% (p < 0.0001; n = 4). In contrast, CMLD006025 (26 μM) did not significantly alter current amplitude (p = 0.29; n = 4). An equi-hypnotic propofol solution (PPF; 4.5 μM) enhanced EC5 currents about 1.8-fold (p < 0.0001; n = 4). G) Bars represent control-normalized currents through human NR1A/2B NMDA receptors. CMLD011815 and CMLD006025 (both at 26 μM) similarly inhibited currents elicited with 100 μM NMDA + 10 μM glycine by about 25% (p < 0.0001; n = 4 for both drugs). An equi-hypnotic ketamine solution (KET; 120 μM) inhibited currents about 95% (p < 0.0001; n = 4). H) Bars represent control-normalized currents through human α4β2 neuronal nicotinic ACh receptors. CMLD011815 and CMLD006025 (both at 26 μM) similarly inhibited currents elicited with1 mM ACh by about 65% (p = 0.0001; n = 4 for both drugs). An equi-hypnotic ketamine solution (KET; 120 μM) inhibited currents over 90% (p < 0.0001; n = 4). I) Symbols represent control-normalized peak currents (mean with 95% CI) through human HCN1 receptors. Currents were inhibited less than 10% in the presence of 26 μM CMLD006025 (n = 9), while an equal concentration of CMLD011815 (n = 9) inhibited currents by about 18% with activation at −70 mV. An equi-hypnotic solution of propofol (PPF; 4.5 μM; n = 5) inhibited HCN1 currents by over 40%. Boltzmann nonlinear regression of G/V relationships (not shown) indicate V50 shifts with both propofol (P< 0.0001 by F-test; n = 5) and with CMLD011815 (P = 0.0015 by F-test), but not with CMLD006025 (both P = 0.11 by F-test). J) Bars represent zebrafish larvae PMR responses (mean with 95%CI; n = 12 per group) measured in the absence and presence of atipamezole (10 nM). Atipamezole reverses PMR inhibition by dexmedetomidine (1.0 μM; p = 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t-test), but not by equi-hypnotic concentrations of CMLD011815 (70 μM; p = 0.86) or CMLD006025 (33 μM; P > 0.999).

ETO = etomidate; PPF = propofol; KET = ketamine; *** P< 0.001; ****P< 0.0001.

We tested equal concentrations (26 μM) of CMLD006025 and CMLD011815 on various ion channels, seeking evidence of differential effects that might account for the stereoselective hypnotic actions in zebrafish and tadpoles. GABAA receptor EC5 currents were enhanced similarly by both compounds (Fig 8E; 1.5 to 1.7-fold; n = 8 each; both p <0.001 vs. control). Glycine α1 receptor EC5 currents were enhanced by propofol, unaffected by CMLD006025, and inhibited about 65% by CMLD011815, demonstrating stereoselective effects (Fig 8F). NMDA receptor currents were inhibited by ~25% in the presence of either CMLD006025 or CMLD011815 (Fig 8G). Neuronal nicotinic ACh receptors were also inhibited by ~65% in the presence of either compound, without stereoselectivity (Fig 8H). Human HCN1 receptors were inhibited more by CMLD0011815 than CMLD006025, but these effects were both much weaker than those of propofol (Fig 8I). Atipamezole did not reverse the hypnotic effects of either enantiomer at equipotent (2 × EC50) concentrations (Fig 8J).

The translational potential of CMLD003237 and CMLD006025 as intravenous sedative-hypnotics was explored in Sprague-Dawley rats. The dosages and number of animals tested was limited by the amount of compounds available. Three rats were each given a single intravenous bolus of CMLD003237 in DMSO, at increasing doses. The first rat received 9 mg/kg and displayed no loss of righting reflexes. A second rat that received 26 mg/kg lost righting reflexes 47 s after the injection and returned to an upright prone position after another 64 s. A third rat that received a 39 mg/kg intravenous bolus lost righting reflexes 25 s after injection and returned to an upright stance after another 5 min 30 s. However, while the hypnotic potencies of CMLD003237 and CMLD006025 were similar in aquatic animals (Figs 6, 8), CMLD006025 injected intravenously at 40 mg/kg did not impair righting reflexes in rats (n = 2).

Discussion

Major results

Goals for developing new sedative-hypnotics include facilitating efficiency in outpatient procedural settings and reducing anesthetic toxicities, particularly in vulnerable populations44. Improving current sedative-hypnotics through rational drug design or mechanism-based drug screening strategies may exclude potentially useful drugs that act through novel mechanisms. We have developed and validated a high-throughput stimulus-response screening approach for sedative-hypnotics in zebrafish larvae and used it in a small library of compounds to discover two drugs with reversible sedative-hypnotic activity in aquatic vertebrates, with one effective in rodents. Our novel approach represents a mechanism-independent primary anesthetic drug discovery strategy based on vertebrate animal stimulus-response assays.

Zebrafish Larvae Photomotor Responses vs. Tadpole Loss of Righting Reflexes

PMRs in zebrafish embryos or larvae have been used previously for neuromodulatory drug screening experiments16,45–47. Embryonic zebrafish responses to intense light stimuli are mediated by photosensors in the developing hindbrain, not the eyes48. Our approach differs from previous studies in using zebrafish larvae, which have more developed vision and neural circuits than embryos49, and in specifically measuring both sedation (unstimulated motor activity) and hypnosis (inhibition of stimulated motor responses). Importantly, development of vision in zebrafish requires exposure to both light and dark, and visual transduction in larvae shows diurnal variation49,50. A weakness of our PMR test is the possibility of identifying drugs that selectively inhibit visual transduction. To address this issue, we validated sedative-hypnotic effects of both known and novel drugs in Xenopus tadpole LoRR assays. We can also use zebrafish larvae responses to acoustic or tactile stimuli to validate hypnotic drug effects.

Our study demonstrated that zebrafish larvae are far more suitable for high-throughput drug screening than tadpoles. Tadpole LoRR assays use about 20 mL of water per animal, so a 10 μM drug solution for 10 tadpoles requires 2 μmoles. In comparison, 10 zebrafish larvae, each in 0.2 mL, require only 20 nmole of drug, 100-fold less than tadpoles. As a practical constraint, we were provided 0.2 μmoles of each drug we screened, ten-fold less than needed for screening at 10 μM in 10 tadpoles, but ten-fold more than needed for 10 zebrafish larvae. The zebrafish larvae PMR assay also required less glassware and benchtop space in comparison with tadpole LoRR tests. Time and effort required for drug potency assays were also lower for zebrafish than tadpoles. Manually pipetting buffer, animals, and drugs into a 96 well plate took about 30 minutes, similar to set-up time for multiple groups of tadpoles. Loading zebrafish larvae into 96-well plates can be further accelerated through automation51. Our computer-controlled PMR tests proceeded with multiple trials for up to 96 animals in parallel. With a 15 minute adaptation and equilibration period before four trials at 3 minute intervals, computerized data acquisition lasted under 30 min, and analysis of results took under 10 minutes after we developed approaches for processing Zebralab outputs for standardized screening and concentration-response experiments. In comparable tadpole experiments, each animal was manually tested and observed for LoRR for 5 s every 5 minutes for 30 minutes. This limited a single worker to testing no more than 20 animals at a time. Tadpole LoRR tests also involve a degree of judgment, which can introduce bias or error, and with multiple lightly anesthetized animals together in a single container, errors related to tracking movements of individual tadpoles inevitably occur. Tadpole results were manually recorded and manually entered for computational analysis, introducing additional potential for human error.

While all healthy tadpoles exhibit brisk righting reflexes in the absence of hypnotic drugs, flashing bright white light onto dark-adapted 7 dpf zebrafish larvae did not elicit motor responses 100% of the time. We also found that un-drugged larvae exhibited a diminishing PMR probability with repeated trials (Fig 3A). This desensitization to photic stimuli diminished in the presence of hypnotics (Fig 3C), introducing a potential source of bias into concentration-response analyses. We minimized this bias by limiting the number of repeated trials to four, resulting in a less than 10% drop in control PMR probability, with stable variance (Fig 3A, B). Importantly, the absence of desensitization in larvae exposed to hypnotic drugs (Fig 3C) indicates that a 15 minute pre-test drug exposure is sufficient to establish steady-state pharmacodynamic effects and thus, effect-site concentrations. Zebrafish larvae desensitization to repeated stimuli has also been used as a method for studying learning and memory35, another neural process inhibited by general anesthetics. In this study, the commercial system used to track activity imposed limitations on the time-resolution of video recordings and the types of data analyses we could perform. In future experiments, more refined behavioral analyses may be achievable using high-speed video recording and customizable video analysis tools for zebrafish behaviors, which are available in public databases52.

Our experiments comparing zebrafish larvae PMR tests and tadpole LoRRs indicate that both assays provide essentially the same information for drug screening (Table 2) and potency determination (Fig 4). Combined with its advantages in drug sample size and work time, these results support adoption of zebrafish larvae as a rapid and reliable platform for screening and initial characterization of sedative-hypnotic drugs.

Discovery of New Potent Sedative Hypnotics in a Drug Library

Our screen or 374 compounds from a larger library identified two compounds, CMLD003237 and CMLD006025, that reversibly and dose-dependently inhibit both zebrafish larvae PMRs and tadpole righting reflexes (Figs 6A & B, and 8A & B). If the frequency of sedative-hypnotics found in the diversity set (0.53%) is representative of all 2651 compounds in the library, then screening the remaining compounds should identify another dozen new sedative-hypnotics. A survey of CMLD003237 effects on six neuronal receptors (Figs 6, 7) suggests that both GABAA receptors (Fig 6C) and neuronal nicotinic ACh receptors (Fig 6F) could contribute to its hypnotic actions. However, inhibition of glycine receptors by CMLD003027 (Fig 6D) might antagonize its anesthetic actions in the spinal cord53. Comparing the hypnotic potencies in aquatic animals of CMLD006025 and its mirror-image enantiomer, CMLD011815, reveals stereoselectivity (Fig 8A-D). Weak modulation of GABAA receptors (Fig 8E), modest inhibition of NMDA receptors (Fig 8G), and inhibition of neuronal nAChRs (Fig 8H) could all contribute to hypnosis by both enantiomers. The relatively low hypnotic potency of CMLD011815 in animals may be due to its inhibition of glycine receptors, which CMLD006025 lacks (Fig 8F). An intriguing and important feature of both CMLD003237 and CMLD006025 is that both apparently act through mechanisms different from established potent sedative-hypnotics, such as etomidate, propofol, alphaxalone, and dexmedetomidine (Fig 2A), all of which selectively target GABAA receptors or α2 adrenergic receptors43. Additional molecular mechanisms other than those we tested in this initial study may also contribute to the hypnotic effects of these new sedative-hypnotics.

CMLD003237 and CMLD006025 display similar hypnotic potency in aquatic animals and comparable physical properties. However, exploratory translational experiments in rats receiving intravenous injections show that CMLD003237 produces reversible LoRR, while CMLD006025 at similar doses does not. It is not surprising that sedative-hypnotic efficacy in small aquatic animals equilibrated for 15 to 30 minutes in a drug solution does not reliably predict the effects of bolus intravenous dosing in mammals. Pharmacokinetic limitations such as blood solubility, protein binding, and transport across the blood-brain barrier influence the latter far more than the former. It is conceivable that one or more important targets for CMLD006025 differ in rats and the two aquatic species we tested, but this type of pharmacodynamic difference is far less likely than a pharmacokinetic difference. Thus, based on these results, we plan to further explore both the unusual hypnotic pharmacology and the translational potential of CMLD003237 and its structural variants. CMLD006025 presents more barriers than CMLD003237 to translational development, while its mechanism of hypnosis is of scientific interest.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Zebrafish represent an animal model with great potential for anesthetic drug discovery as well as basic and translational research on general anesthetics. Further screening of drug libraries using the approach we developed is likely to reveal many more potent sedative-hypnotics. Those that act through novel mechanisms will be of great scientific interest. Neuroscience techniques combining recordings from or stimulation of neuronal circuit activity54,55 with behavioral tracking, including photomotor responses,48 have been developed for zebrafish, and these approaches could reveal important details about anesthetic mechanisms in neural networks. Methods for site-directed genetic manipulation of zebrafish have also been developed56–58. Zebrafish with knockout or site-directed mutations in putative anesthetic target genes have the potential to provide new insights into anesthetic mechanisms and efficient screening strategies to find target-selective anesthetics. These approaches are being actively explored in our lab.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Cotten, MD, PhD and James Boghosian, BA (both of MGH Dept. of Anesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine, Boston, MA, USA) for expert help with rat experiments. We also thank Erwin Sigel, PhD (retired, previously of the Institute for Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland and Constanza Maldifassi, PhD (Centro Interdisciplinario de Neurociencia de Universidad de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile); for samples of, and information about, potent GABAA receptor modulators used in some experiments.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by grants from Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China and the Chinese Medical Association, Beijing, China (both to X.Y.). The Dept. of Anesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA supported this work through a Research Scholars award and an Innovation Grant (both to S.A.F.). Contributions to this research from the Boston University Center for Molecular Discovery (J.A.P., L.E.B., S.E.S, W.X, and R.T.) were supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD, USA (R24 GM111625).

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: Some of the work described in this manuscript was presented at the Association of University Anesthesiologists -International Anesthesia Research Society Annual Meeting, May, 2017, in Washington, D.C., USA.

Conflict of Interest: Massachusetts General Hospital and Boston University have filed a patent application for compounds related to the new hypnotics described here. Drs. Brown, Forman, Jounaidi, Porco, Schaus, and Yang are named as co-inventors. Other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Tanious MK, Beutler SS, Kaye AD, Urman RD. New Hypnotic Drug Development and Pharmacologic Considerations for Clinical Anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35:e95–e113. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitilian HV, Eckenhoff RG, Raines DE. Anesthetic drug development: Novel drugs and new approaches. Surg Neurol Int. 2012;4:S2–S10. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.109179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krasowski MD, Hopfinger AJ. The discovery of new anesthetics by targeting GABA(A) receptors. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2011;6:1187–201. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.627324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J, Chen T, Norris T, Knappenberger K, Huston J, Wood M, Bostwick R. A high-throughput functional assay for characterization of gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) channel modulators using cryopreserved transiently transfected cells. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2008;6:781–6. doi: 10.1089/adt.2008.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joesch C, Guevarra E, Parel SP, Bergner A, Zbinden P, Konrad D, Albrecht H. Use of FLIPR membrane potential dyes for validation of high-throughput screening with the FLIPR and microARCS technologies: identification of ion channel modulators acting on the GABA(A) receptor. J Biomol Screen. 2008;13:218–28. doi: 10.1177/1087057108315036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falk-Petersen CB, Sogaard R, Madsen KL, Klein AB, Frolund B, Wellendorph P. Development of a Robust Mammalian Cell-based Assay for Studying Recombinant alpha4 beta1/3 delta GABAA Receptor Subtypes. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;121:119–129. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heusser SA, Howard RJ, Borghese CM, Cullins MA, Broemstrup T, Lee US, Lindahl E, Carlsson J, Harris RA. Functional Validation of Virtual Screening for Novel Agents with General Anesthetic Action at Ligand-Gated Ion Channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84:670–678. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.087692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Middendorp SJ, Puthenkalam R, Baur R, Ernst M, Sigel E. Accelerated discovery of novel benzodiazepine ligands by experiment-guided virtual screening. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1854–9. doi: 10.1021/cb5001873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maldifassi MC, Baur R, Pierce D, Nourmahnad A, Forman SA, Sigel E. Novel positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors with anesthetic activity. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25943. doi: 10.1038/srep25943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lea WA, Xi J, Jadhav A, Lu L, Austin CP, Simeonov A, Eckenhoff RG. A high-throughput approach for identification of novel general anesthetics. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKinstry-Wu AR, Bu W, Rai G, Lea WA, Weiser BP, Liang DF, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Maloney DJ, Eckenhoff RG. Discovery of a novel general anesthetic chemotype using high-throughput screening. Anesthesiology. 2015;122:325–33. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hevers W, Hadley SH, Luddens H, Amin J. Ketamine, but not phencyclidine, selectively modulates cerebellar GABA(A) receptors containing alpha6 and delta subunits. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5383–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5443-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang DS, Penna A, Orser BA. Ketamine Increases the Function of gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptors in Hippocampal and Cortical Neurons. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:666–677. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alkire MT, Hudetz AG, Tononi G. Consciousness and anesthesia. Science. 2008;322:876–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1149213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franks NP. General anaesthesia: from molecular targets to neuronal pathways of sleep and arousal. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:370–86. doi: 10.1038/nrn2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokel D, Peterson RT. Using the zebrafish photomotor response for psychotropic drug screening. Methods Cell Biol. 2011;105:517–24. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fontana BD, Mezzomo NJ, Kalueff AV, Rosemberg DB. The developing utility of zebrafish models of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders: A critical review. Exp Neurol. 2018;299:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savechenkov PY, Zhang X, Chiara DC, Stewart DS, Ge R, Zhou X, Raines DE, Cohen JB, Forman SA, Miller KW, Bruzik KS. Allyl m-Trifluoromethyldiazirine Mephobarbital: An Unusually Potent Enantioselective and Photoreactive Barbiturate General Anesthetic. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6554–65. doi: 10.1021/jm300631e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) 5th. University of Oregon Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramerstorfer J, Furtmuller R, Sarto-Jackson I, Varagic Z, Sieghart W, Ernst M. The GABAA receptor alpha+beta- interface: a novel target for subtype selective drugs. J Neurosci. 31:870–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5012-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopp S, Baur R, Sigel E, Mohler H, Altmann KH. Highly potent modulation of GABA(A) receptors by valerenic acid derivatives. ChemMedChem. 2010;5:678–81. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baur R, Schuehly W, Sigel E. Moderate concentrations of 4-O-methylhonokiol potentiate GABAA receptor currents stronger than honokiol. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:3017–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovering F, Bikker J, Humblet C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6752–6. doi: 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown LE, Chih-Chien Cheng K, Wei WG, Yuan P, Dai P, Trilles R, Ni F, Yuan J, MacArthur R, Guha R, Johnson RL, Su XZ, Dominguez MM, Snyder JK, Beeler AB, Schaus SE, Inglese J, Porco JA., Jr Discovery of new antimalarial chemotypes through chemical methodology and library development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6775–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desai R, Savechenkov PY, Zolkowska D, Ge RL, Rogawski MA, Bruzik KS, Forman SA, Raines DE, Miller KW. Contrasting actions of a convulsant barbiturate and its anticonvulsant enantiomer on the alpha1 beta3 gamma2L GABAA receptor account for their in vivo effects. J Physiol. 2015;593:4943–61. doi: 10.1113/JP270971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pejo E, Santer P, Jeffrey S, Gallin H, Husain SS, Raines DE. Analogues of Etomidate: Modifications around Etomidate’s Chiral Carbon and the Impact on In Vitro and In Vivo Pharmacology. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:290–301. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bode CM, Ting A, Schaus SE. A general organic catalyst for asymmetric addition of stabilized nucleophiles to acyl imines. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:11499–11505. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong S, Cahill KJ, Kang MI, Colburn NH, Henrich CJ, Wilson JA, Beutler JA, Johnson RP, Porco JA. Microwave-based reaction screening: tandem retro-Diels-Alder/Diels-Alder cycloadditions of o-quinol dimers. J Org Chem. 2011;76:8944–54. doi: 10.1021/jo201658y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong S, Hamel E, Bai R, Covell DG, Beutler JA, Porco JA., Jr Enantioselective synthesis of (+)-chamaecypanone C: a novel microtubule inhibitor. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:1494–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong S, Zhu J, Porco JA., Jr Enantioselective synthesis of bicyclo[2.2.2]octenones using a copper-mediated oxidative dearomatization/[4 + 2] dimerization cascade. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2738–9. doi: 10.1021/ja711018z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce DW, Pejo E, Raines DE, Forman SA. Brief report: carboetomidate inhibits alpha4/beta2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at concentrations affecting animals. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:70–2. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318254273e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nourmahnad A, Stern AT, Hotta M, Stewart DS, Ziemba AM, Szabo A, Forman SA. Tryptophan and Cysteine Mutations in M1 Helices of α1β3γ2L γ-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptors Indicate Distinct Intersubunit Sites for Four Intravenous Anesthetics and One Orphan Site. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:1144–58. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tibbs GR, Rowley TJ, Sanford RL, Herold KF, Proekt A, Hemmings HC, Jr, Andersen OS, Goldstein PA, Flood PD. HCN1 channels as targets for anesthetic and nonanesthetic propofol analogs in the amelioration of mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;345:363–73. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.203620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du WJ, Du JL, Yu T. Establishment of an anesthesia model induced by etomidate in larval zebrafish. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2016;68:301–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts AC, Bill BR, Glanzman DL. Learning and memory in zebrafish larvae. Front Neural Circuits. 2013;7:126. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alifimoff JK, Firestone LL, Miller KW. Anaesthetic potencies of primary alkanols: implications for the molecular dimensions of the anaesthetic site. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;96:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tonner PH, Scholz J, Lamberz L, Schlamp N, Schulte am Esch J. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase decreases anesthetic requirements of intravenous anesthetics in Xenopus laevis. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1479–85. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tonner PH, Poppers DM, Miller KW. The general anesthetic potency of propofol and its dependence on hydrostatic pressure. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:926–931. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Husain SS, Stewart D, Desai R, Hamouda AK, Li SG, Kelly E, Dostalova Z, Zhou X, Cotten JF, Raines DE, Olsen RW, Cohen JB, Forman SA, Miller KW. p-Trifluoromethyldiazirinyl-etomidate: a potent photoreactive general anesthetic derivative of etomidate that is selective for ligand-gated cationic ion channels. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6432–44. doi: 10.1021/jm100498u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee-Son S, Waud BE, Waud DR. A comparison of the potencies of a series of barbiturates at the neuromuscular junction and on the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;195:251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tonner PH, Scholz J, Koch C, Schulte am Esch J. The anesthetic effect of dexmedetomidine does not adhere to the Meyer-Overton rule but is reversed by hydrostatic pressure. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:618–22. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199703000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bandyopadhyaya AK, Manion BD, Benz A, Taylor A, Rath NP, Evers AS, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S, Covey DF. Neurosteroid analogues. 15.A comparative study of the anesthetic and GABAergic actions of alphaxalone, Delta16-alphaxalone and their corresponding 17-carbonitrile analogues. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:6680–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solt K, Forman SA. Correlating the clinical actions and molecular mechanisms of general anesthetics. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2007;20:300–6. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32816678a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forman SA. Molecular Approaches to Improved General Anesthetics. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2010;28:761–71. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]