Abstract

The objective of this article is to examine the individual and relational characteristics of adolescent girls with a history of physical DV, as well as to utilize partner-specific, temporal data to explore links between these factors and recent or ongoing DV experiences. Participants were 109 high school girls (ages 14–17) identified as having a history of DV through a school-based screening procedure. Details regarding the timing of DV and links with specific dating partners were gathered using Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview methodology. At study entry, 30% endorsed clinical levels of depression symptoms and 89% reported delinquent behaviors. Forty-four percent reported vaginal intercourse in their lifetime and of those, 35% reported not using a condom at last sex. During the 90 days prior to study entry, 69% of youth reported having a romantic relationship and 58% of those youth reported physical/sexual violence. Data revealed that more physical/sexual violence was associated with longer relationship length, Wald χ2(2) = 1,142.63, p < .001. Furthermore, depressive symptoms, not delinquency, contributed significantly to recent DV experiences, even when relationship length was controlled. Our findings suggest that prevention programs for this population should teach participants how to quickly recognize unhealthy relationship characteristics, as violence severity increases with relationship length. Programs for adolescent girls should also address depressive symptoms, which are linked to DV severity when other risks are taken into account. Finally, the TLFB calendar method appears useful for gathering the temporal and partner-specific data needed to understand the complexity of dating relationships and violence experiences in this population.

Keywords: adolescents, dating violence, depression, prevention, girls

Adolescents may experience dating violence (DV) through forms of psychological (disparaging and/or controlling behaviors), physical (physically attacking one’s partner), and/or sexual abuse (forced sexual contact toward one’s romantic partner; Wolfe et al., 2001). Over the past 15 years, mounting research has documented the high rates of DV and its associated negative outcomes. For instance, Silverman, Raj, Mucci, and Hathaway (2001) showed that approximately 20% of adolescent girls in their sample experienced physical and/or sexual abuse by their dating partner. In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that 9% of adolescents were victimized by physical DV within the 12 months before data collection (CDC, 2014). To date, many community- and school-based studies have focused on identifying the correlates and predictors of DV to inform the development of primary prevention programs. Although studies have consistently reported both similar and higher rates of nonsexual DV for females compared with males, girls are more likely to fall victim to physical injury and experience psychological consequences from DV exposure (Archer, 2000, 2002). Hence, the present study focuses on the characteristics of adolescent girls who were exposed to physical DV as victims, perpetrators, or both. Existing population-based studies, where a subset of participants has experienced DV in the past year or over their lifetime, have largely focused on individual factors (i.e., DV attitudes, depression, and delinquency) and to a lesser extent on relational factors (i.e., relationship length, breakup, sexual activity, condom self-efficacy, and sexual knowledge) that may relate to DV involvement. However no studies to date have used temporal assessment strategies, such as calendar methods, to examine how recent or ongoing DV experiences relate to both individual and relational factors in the affected group. In addition, it is investigated whether the characteristics reported by adolescent girls with a history of DV differ based on the type of violence experienced (e.g., psychological vs. physical/sexual violence). Understanding these associations may provide implications for prevention and intervention programs to more effectively reach adolescent girls actively involved in abusive relationships.

Individual Characteristics

The association between DV and acceptance of DV among adolescents and young adults is well documented. Specifically, perpetrators and victims of DV are likely to justify the use of violence depending on the circumstance such as if one is challenged to a fight and/or humiliated by one’s romantic partner (Brendgen, Vitaro, Tremblay, & Wanner, 2002; Foo & Margolin, 1995; Lichter & McCloskey, 2004; Miller, Gorman-Smith, Sullivan, Orpinas, & Simon, 2009; Orpinas, Hsieh, Song, Holland, & Nahapetyan, 2013; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2008). From a social-cognitive perspective (Bandura, 1978, 2001), aggression is a behavior learned from the benefits and consequences gained after its enactment. Within the context of romantic relationships, adolescents with a history of DV may continue their involvement in an aggressive relationship if acting out with such behaviors previously led to optimal outcomes for the perpetrator (e.g., the victim giving in to the perpetrator’s demands). The victim may also learn that engagement in DV is an acceptable means of dealing with conflicts. Under this logic, adolescent girls in the present study are expected to endorse positive attitudes about the use of violence in romantic relationships. However, because attitudes can change based on experience, it is examined whether the presence and type of recent or ongoing DV is related to concurrent levels of DV acceptance.

Another aspect to consider is the role of depression among adolescents with a history of DV. Past studies suggest that levels of depressive symptoms are generally higher among adolescents who perpetrated and/or were victimized by dating aggression (Ackard & Neumark-Sztainer, 2002; Champion, Collins, Reyes, & Rivera, 2009; Chase, Treboux, & O’Leary, 2002; Exner-Cortens, Eckenrode, & Rothman, 2013; Rich, Gidycz, Warkentin, Loh, & Weiland, 2005). Social-cognitive models of depression generally suggest that negative interpersonal experiences and individuals’ interpretations of these experiences can lead to depressive symptoms (Cicchetti & Schneider-Rosen, 1984; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999; Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). DV involvement is likely a stressful experience for adolescents and can understandably lead to negative interpretations about the self and/or relationships. Such interpretations can also contribute to feelings of depression. Sussex and Corcoran (2005) indicated that teen mothers in violent dating relationships reported higher levels of depression that were sustained even after relationship violence has ceased. Moreover, depression can serve as a precipitant to DV exposure. For instance, a 5-year longitudinal study in high schools found that girls with more days in depressive episodes were more likely to suffer later psychological and physical abuse victimization by boyfriends over the follow-up period (Rao, Hammen, & Daley, 1999). Although the contribution of prior DV experiences was not accounted for, the authors note that depression was likely both a contributor and an outcome of the relationship problems. In a prospective study of adolescent females, depressive symptomatology yielded an 86% greater likelihood of physical abuse victimization by an intimate partner 5 years later (Lehrer, Buka, Gortmaker, & Shrier, 2006). These findings remained significant when childhood physical and sexual abuse as well as prior DV experiences were controlled. Elevated depression among adolescent girls has also been found to predict violence perpetration toward their dating partners (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997; McCloskey & Lichter, 2003). Thus, adolescent girls’ depression appears to be an important individual-level risk factor for DV perpetration, as well as both a risk and consequence of DV victimization. Because depression is episodic in nature, the presence and type of DV may relate to concurrent levels of depressive symptoms.

It is also possible for adolescents with a history of DV to have a history of deviant behaviors. Deviant behaviors can best be described as behaviors that can cause psychological and/or physical harm to adolescents’ well-being (Vézina et al., 2011). According to problem-behavior theory (PBT), deviant behaviors may covary across domains and, therefore, should be regarded as a constellation of risk behaviors as opposed to being investigated as specific conduct problems perpetrated in a particular context (Jessor, 1991). From this perspective, it may be argued that DV perpetration, when not enacted as self-defense, is a type of aggressive delinquency that ought to be examined along with other forms of deviant behaviors (i.e., delinquent acts involving aggression). Past studies suggest that adolescents who perpetrate and/or are victimized by physical DV are likely to engage in various forms of aggressive delinquent behaviors ranging from carrying a weapon to perpetrating physical violence toward a peer (Brendgen et al., 2002; Chiodo et al., 2012; Ozer, Tschann, Pasch, & Flores, 2004; Simons, Lin, & Gordon, 1998; Vézina et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2008). In addition, Williams and colleagues (2008) indicated that adolescents who possess attitudes that are accepting of aggression may follow a “delinquency trajectory,” whereby aggressive behaviors in romantic relationships are ongoing and co-occur with aggressive behaviors in other contexts. Therefore, adolescent girls previously involved in an aggressive relationship are expected to report that they have engaged in aggressive forms of delinquency as well. It is also examined whether the type of DV experienced in a recent or ongoing relationship is related to active delinquent behaviors.

Relational Characteristics

Findings from the CDC (2008) reveal that female victims of intimate partner violence have a threefold increased risk of HIV or sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Previous studies of intimate partner violence among adults have found a significant association between violence victimization and exposure to sexual risk behavior (Alleyne, Coleman-Cowger, Crown, Gibbons, & Vines, 2011; Eby, Campbell, Sullivan, & Davidson, 1995; Wingood & DiClemente, 2000). Emerging research has also revealed a significant relation between DV and sexual risk behaviors in adolescence (see Teitelman, Dichter, Cederbaum, & Campbell, 2007, for a review). Among adolescent girls, DV contributes to several HIV sexual risk behaviors including unprotected sex, having multiple partners, and alcohol use prior to sexual encounters (Roberts, Auinger, & Klein, 2005; Silverman et al., 2001; Wingood, DiClemente, McCree, Harrington, & Davies, 2001). A number of investigators have found physical DV to be associated with the failure to use a condom during the most recent sex (Wingood et al., 2001), as well as inconsistent condom use (Roberts et al., 2005). In one investigation, verbal abuse was found associated with decreased condom use (Silverman et al., 2001). Silverman and colleagues also found physical DV victimization to be associated with an increased risk of pregnancy and younger age of first intercourse. The link between DV exposure and sexual risk behavior has important health implications for adolescents, particularly females; one in four sexually active adolescent females have an STI, such as chlamydia or human papillomavirus (HPV; Forhan et al., 2009). The disproportionately high rates of STIs among adolescent girls are important because the presence of these infections is known to facilitate HIV transmission. Despite the public health significance of these associations, relatedly little is known about the sexual knowledge and attitudes of DV-exposed girls. Studies of other high-risk groups of adolescents have found relatively low levels of HIV knowledge coupled with low self-efficacy to negotiate condom use with their dating partner (J. L. Brown et al., 2014; Wingood et al., 2001). Thus, a goal of the current study is to characterize rates of sexual activity, unprotected sex, HIV knowledge, and self-efficacy for condom use among this selected sample of DV-exposed girls, and to determine whether sex-related attitudes, knowledge, and behavior relate to DV experiences.

Like sexual behavior, relationship structure is another important characteristic of dating partnerships that may be different for DV-exposed girls and link with recent or ongoing DV experiences. Given the typical short length of adolescent romantic relationships (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003; Connolly & McIsaac, 2009), it is critical to understand the influence of change in dating partner on adolescent DV. If the relationship is violent, a longer partnership may lead to a continuation of DV, and may even increase the likelihood of more severe violence due to an increased opportunity for such behaviors to take place. Also, the amplified intensity and intimacy that emerges in a long-term partnership could lead to more violence. In accordance with systems theory, violence can become a normative pattern among couples who remain together after the first occurrence of such behaviors (Giles-Sims, 1983). However, a relationship breakup may disrupt such a pattern, which in turn can lead to change in the behaviors enacted within the relationship (Whitchurch & Constantine, 1993). Stability in physical DV (perpetration and victimization) has been shown among adolescent (Fritz & Smith Slep, 2009; Giordano, Soto, Manning, & Longmore, 2010; O’Leary & Slep, 2003) and young adult couples (Capaldi, Shortt, & Crosby, 2003) who remain with the same romantic partner over time. Capaldi and colleagues also showed an increase in perpetrating physical aggression among young men who stayed with the same romantic partner across a 2-year interval. Therefore, relationship stability is expected to serve as an important relational characteristic among adolescent girls previously exposed to DV. Because more time with a dating partner creates increased opportunities for coercive relationships to become physically violent, it is also expected that physical violence will be associated with more days in that relationship.

One factor that has greatly reduced researchers’ ability to examine the actual length of violent dating relationships has been the reliance on survey methods that aggregate the frequency of violence experienced over a particular time frame (often past year or lifetime). For example, the most widely used instrument for the estimation of the prevalence and incidence of DV is the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI; Wolfe et al., 2003). The CADRI measures victimization and perpetration behaviors in conflict situations during the past year. Adolescents must aggregate their experiences both over time and across partners to generate an estimate of frequency. As a result, neither the timing of abuse experiences nor the presence of abuse in one versus multiple relationships can be discerned. Details regarding the timing of violent experiences (on what days and when) could provide valuable information about factors that might be related to the occurrence of DV (Fals-Stewart, Birchler, & Kelley, 2003). Thus, in the current study, we asked participants to report DV experiences for each of up to three dating partners in the past 90 days. Then, an adapted Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview was administered to document the exact timing of each individual dating relationships, including breakups and concurrency. This approach will allow us to combine partner-specific DV information with temporal data from the TLFB to establish which relationships were actively violent.

Present Study

The present study builds on the current literature by examining the individual (acceptance of DV, depression, and delinquency) and relational (length, breakups, sexual activity, condom self-efficacy, and sexual knowledge) characteristics of adolescent girls with a history of physical DV perpetration and/or victimization. We aim to fill a gap in the existing literature by utilizing partner-specific, temporal data to explore links between these factors and recent or ongoing DV experiences (i.e., past 90 days). The noted above characteristics will be examined for perpetration and victimization combined as mutual violence is common among adolescents (Ackard & Neumark-Sztainer, 2002; Cano, Avery-Leaf, Cascardi, & O’Leary, 1998; Connolly, Friedlander, Pepler, Craig, & Laporte, 2010; Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; O’Leary & Slep, 2003). Furthermore, there is reason to believe that the experience of verbal abuse and controlling behaviors (i.e., psychological abuse) when unaccompanied by physical or sexual violence may be qualitatively different than concurrent psychological, physical, and sexual abuse (Jouriles, Garrido, Rosenfield, & McDonald, 2009; Silverman et al., 2001). Indeed, these forms of DV are associated with their own set of negative psychosocial outcomes (Holt & Espelage, 2005; Lawrence, Yoon, Langer, & Ro, 2009; Silverman et al., 2001). We, therefore, examined relationships with psychological and physical/sexual abuse separately. Finally, analyses were compared across race and socioeconomic status (SES), given that some studies have found minority adolescents and adolescents from lower SES backgrounds more likely to be involved in an aggressive relationship (Aldarondo & Sugarman, 1996; Caetano, Field, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2005; Holt & Espelage, 2005; O’Keefe, 1998).

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected as part of a randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate the efficacy of an intervention to reduce DV and sexual risk behaviors among adolescents with histories of physical DV perpetration and/or victimization (Project Date Skills to Manage Aggression in Relationships for Teens (SMART)). Although the participants were followed over time, only the baseline data were used for the current study.

Female high school students (n = 655) were approached during their health and physical education classes. Teens were given a presentation regarding the study and were provided with parental consent forms that gave permission to complete a screening questionnaire at school. Confidential drop boxes were placed in the high schools for students to return completed consent forms. Students were compensated US$5 for returning the consent forms, regardless of their parent’s decision regarding participation. Participants who returned parental consent forms indicating permission to be screened were assessed for lifetime physical abuse perpetration and victimization utilizing items from the CADRI (Wolfe et al., 2001) to determine eligibility. Youth who screened positive for a history of physical DV perpetration and/or victimization were contacted by phone and offered the opportunity to enroll in the study. Parental consent for participation in the full study, separate from the screening consent, was obtained once the teen expressed interest in participating. Once informed consent was obtained, participants completed a survey, administered using audio computer-assisted structured interviews (ACASI) on laptop computers. The teen assessment also included a TLFB interview with a trained research assistant to track DV and sexual behavior. Teens received US$20 for completing the assessment.

The self-report surveys administered did not gather adequate information to establish whether or not any participant was at imminent risk of life-threatening DV; however, all families were aware that if any teen spontaneously shared information during the assessment interviews or group sessions, which indicated that the teen was at imminent risk of life-threatening DV (e.g., threat made on their life), that information would be immediately shared with the teen’s parent or guardian. This procedure was explained in full to families prior to obtaining their consent to participate. Furthermore, this study was approved by the affiliated hospital institutional review board.

The participants include female high school students (ages 14–17) enrolled in five public high schools in the urban areas surrounding Providence, Rhode Island. The average age of participants at baseline was 15.75 years (SD = 0.94 years). During the 3-year recruitment period, 358 girls were screened for a history of physical DV perpetration or victimization. Of those, 144 were found eligible to participate in the study based on their history of physical DV perpetration and/or victimization and 109 ultimately participated. Self-reported ethnicity and race among the sample was 50% Hispanic, 35% African American, 22% White, 8% American Indian, and 3% Asian; participants were able to endorse multiple options for race and ethnicity. Regarding family structure, 96% reported having a mother figure at home and 62% reported having a father figure at home. Participants reported on their eligibility for free or reduced-price school lunch, which was examined as a measure of SES; 81% reported that they currently qualified for free or reduced-price lunch (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Unadjusted Descriptive Statistics.

| n (%)/M (SD) | Scale Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 9 (8%) | |

| Asian | 3 (3%) | |

| Black | 38 (35%) | |

| White | 24 (22%) | |

| Other race | 50 (46%) | |

| Ethnicity (% Hispanic) | 54 (50%) | |

| Age | 15.75 (0.94) | 15–18 |

| Free or reduced-price lunch | 88 (81%) | |

| Mother figure at home | 105 (96%) | |

| Father figure at home | 67 (62%) | |

| Had vaginal sex | 48 (44%) | |

| Used condom at last sex | 31 (65%) | |

| Acceptance of couple violence | 1.46 (0.50) | |

| Partner-related condom self-efficacy | 1.87 (0.85) | 1–4 |

| HIV knowledge | 12.03 (3.53) | 1–5 |

| Beck Depression Inventory–II | 16.75 (11.33) | 1–4 |

| Delinquency | 96 (89%) | |

Measures

The screening survey gathered data on lifetime experiences. The Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II) assessed the past 2 weeks; all other measures assessed solely the past 90 days.

Screening

CADRI

The CADRI (Wolfe et al., 2001) is a 35-item measure completed by teens in reference to actual conflict or disagreement with a current or recent dating partner. It assesses abuse perpetration and victimization. Each question is asked twice, first in relation to perpetration, then in relation to victimization. The CADRI has strong internal consistency (total α = .83) and 2-week test–retest reliability, r = .68, p < .01 (Wolfe et al., 2001), as well as acceptable partner agreement (r = .64, p < .01) on the basis of 35 couples (Wolfe et al., 2003). At screening, the CADRI was utilized to assess lifetime physical DV perpetration and victimization.

Individual characteristics

Acceptance of Couple Violence (ACV) Questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed to assess beliefs and attitudes about couple violence among adolescents and has been validated in longitudinal studies of adolescent DV behavior (Foshee, Fothergill, & Stuart, 1992). Participants rated how much they agree with a series of statements about DV on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater ACV. A mean ACV score for acceptance of general DV was computed for each participant by averaging across the 11 items. Internal consistency for this measure was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .90).

The BDI-II

The BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 27-item self-report instrument intended to assess the existence and severity of symptoms of depression during the past 2 weeks, according to the American Psychiatric Association’s (1994)Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). The BDI-II has shown excellent internal consistency (α= .93 for the college students) and validity. In the present study, scores on each BDI item were summed to create a total score.

Shortened Peer Delinquency Scale (SPDS)

The SPDS (Moffitt & Silva, 1988) is a self-report questionnaire that includes 16 items covering a range of deviant acts (e.g., running away, stealing). Participants were asked to rate the frequency of their engagement in each deviant act in the past 3 months on a scale of 0 (never), 1 (once or twice), or 2 (three or more times). Internal consistency is good (α = .86; Moffitt & Silva, 1988). In the present study, we computed a count for number of aggressive delinquent behaviors endorsed by each participant from the following five items: getting in a physical fight, beating someone up, bringing a knife or razor to school, bringing a gun to school, and bringing a bat or stick to school to use as a weapon.

Relationship characteristics

For all surveys gathering information on romantic partners, the term partner was defined broadly as “a boyfriend/girlfriend, sexual partner, or someone you are going out with. You could be committed to this person (dating only them) or you could be in an open relationship where you are dating other people.”

Recent/ongoing DV

Psychological, physical, and sexual DV perpetration and victimization questions from the CADRI (Wolfe et al., 2001) were administered. Participants were asked to answer each question for each of up to three separate partners (identified by their initials) over the past 90 days. The partner-specific DV data were then used to categorize participant’s romantic relationships based on the type of violence: nonviolent (no perpetration or victimization items were endorsed), psychologically violent (emotional violence and controlling behaviors were reported but not physical or sexual violence), and physically/sexually violent (relationships involved physical and/or sexual violence).

Timeline Followback–Dating Violence (TLFB-DV)

The TLFB-DV is a semistructured calendar-based interview method for assessing recent relationship violence. The interview was adapted for this project based on the TLFB–Spousal Violence version developed by Fals-Stewart and colleagues (2003). The TLFB-DV was administered by a trained research staff member. Participants were asked to retrospectively describe their recent DV and sex history over the past 90 days. Fals-Stewart et al. (2003) reported excellent test–retest reliability (intraclass correlations = .91–1.0) and evidence for both concurrent and discriminant validity.

For the current study, the TLFB was used to measure the number of days each participant was engaged in a romantic relationship during the 90 days prior to the baseline assessment. Each partner was identified by initials so that the exact number of days with that partner could be summed. In addition, specific dates for breakups with a specific partner, initiation of a relationship with a new partner, concurrent relationships with multiple partners, and reinitiation of a relationship with a previous partner were gathered. Using these dates, we derived the length of each participant’s relationship with each partner and the duration and number of breakups in each relationship during the 90-day TLFB window.

The Adolescent Risk Behavior Assessment (ARBA)

The ARBA (Donenberg, Emerson, Bryant, Wilson, & Weber-Shifrin, 2001) is a reliable and valid computer-assisted survey assessing self-reported behaviors associated with HIV infection. The measure was adapted to assess dating and sexual behaviors for up to three separate partners in the past 3 months (using partner initials to link these data with our other partner-specific measures, the CADRI and TLFB). Sexual risk questions ask about type of sexual behavior (i.e., anal, oral, vaginal), frequency of sex, age of sexual debut, number of partners, and condom use. A romantic relationship breakup question developed for this study asks about the presence of a breakup with each partner.

HIV Knowledge

This scale was developed to assess adolescents’ knowledge about HIV and AIDS using 23 true/false items (L. K. Brown, DiClemente, & Beausoleil, 1992). A total HIV knowledge score was computed for each participant by summing the number of correct items. Higher scores indicate greater HIV knowledge. Internal consistency for the HIV Knowledge Scale in this sample was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .71).

Partner-Related Condom Self-Efficacy

This 13-item measure was derived from a longer scale of condom self-efficacy attitudes and has been used in previous HIV prevention projects to assess self-confidence in condom use (e.g., could you use a condom if your partner did not want to; L. K. Brown, Lourie, Zlotnick, & Cohn, 2000; Lescano, Brown, Miller, & Puster, 2007). Participants rated how sure they were that they could use a condom in each situation on a scale from 1 (very sure) to 4 (couldn’t do it). A mean condom self-efficacy score was computed for each participant by averaging across the 13 items. Internal consistency for this scale in the present sample was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .93).

Analysis Plan

Bivariate relations between individual and relational characteristics with DV in the past 90 days were analyzed first, then differences in individual and relational characteristics by DV level were examined using ANOVA and chi-square analyses. We then utilized generalized linear models (GLMs) in SPSS 22.0 to examine the collective relationship between these variables to acute DV level in our selected sample of DV-exposed girls.

Results

Individual Characteristics

Acceptance of DV

Interestingly, accepting attitudes regarding DV were low. Participants tended to strongly disagree or disagree with most examples of DV on the ACV scale (M = 1.46, SD = 0.50). Acceptance of DV did not differ by DV type (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationship Characteristics.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Dating violence | |

| None | 10 (12) |

| Psychological | 31 (36) |

| Physical/sexual | 46 (53) |

| Relationship length | |

| <30 days | 23 (34) |

| 30–59 days | 11 (16) |

| 60–89 days | 10 (15) |

| 90+ days | 24 (35) |

| No. of relationships with breakups/re-partnerships | 8 (12) |

| No. of participants with concurrent partnerships | 8 (7) |

Note. n = 87 relationships among 109 participants; n = 68 had valid relationship length data, and n = 36 were observed to begin during the 90-day study period.

Depression

A sizable percentage of participants (29%) had BDI-II depressive symptom scores in the moderate to severe range (≥20). Depression did not differ by DV type.

Delinquency

Rates of delinquent behaviors involving aggression were as follows: 17% had a physical fight with a peer and 12% have carried a weapon. Delinquency did not differ by DV type.

Relational Characteristics

DV

At study entry, 67% (n = 73) of participants enrolled in the study due to their lifetime history of DV were involved in a romantic relationship in the past 3 months. Those participants reported on 87 romantic relationships during the study period. The majority of relationships were classified as physically violent (53%), with 36% classified as psychologically violent and 12% having no reported emotional, controlling, physical, or sexual DV in the past 90 days (see Table 3). For each form of DV, perpetration and victimization experiences were correlated (Pearson rs = .20–.67, all ps < .10), suggesting mutual aggression.

Table 3.

Differences in Individual and Relational Characteristics by Type of DV.

| No DV | Psychological DV | Physical/Sexual DV | F(df)/χ2 (df) | Tukey’s HSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| n (%)/M (SD) | n (%)/M (SD) | n (%)/M (SD) | |||

| Acceptance of couple violence | 1.38 (0.42) | 1.35 (0.45) | 1.45 (0.44) | 0.48 | |

| Beck Depression Inventory–II | 14.14 (10.43) | 12.85 (7.69) | 18.73 (11.51) | 2.71 | |

| Delinquency | 0.14 (0.38) | 0.31 (0.74) | 0.57 (0.77) | 1.57 | |

| Ever had vaginal sex | 5 (71%) | 13 (52%) | 18 (50%) | 1.09 (2) | |

| Used condom at last sex | 4 (80%) | 11 (73%) | 10 (53%) | 2.19 (2) | |

| HIV knowledge | 14.57 (2.07) | 10.00 (4.19) | 13.05 (2.77) | 8.65*** | 1 > 2**, 2 < 3** |

| Partner-related condom self- efficacy | 1.85 (1.04) | 2.08 (0.94) | 1.73 (0.80) | 1.25 |

Note. DV = dating violence; HSD = honest significant difference.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behavior

One study goal was to characterize rates of sexual activity, unprotected sex, HIV knowledge, and self-efficacy for condom use within our sample of DV-exposed girls. During the past 3 months, 44% of the participants reported having had vaginal sex in their lifetime, and of those, 35% reported not using a condom at last sex. The average participant rated her self-efficacy for condom use in sexual situations as between “very sure” and “sure” (M = 1.87, SD = 0.85). HIV knowledge was low, with participants getting only half of the questions correct, on average (M = 12.03, SD = 3.53). Sexual activity, unprotected sex, and self-efficacy for condom use did not differ by the type of DV. However, HIV knowledge did differ by DV type: Participants in relationships characterized by psychological violence had the lowest rates of HIV knowledge (M = 10.00), followed by participants in physically and/or sexually violent relationships (M = 13.57), whereas participants in nonviolent relationships had the highest levels of HIV knowledge (M = 14.05). Post hoc Tukey tests showed that participants whose relationships were psychologically violent had significantly lower HIV knowledge scores than participants whose relationships were nonviolent (p < .01) or physically/sexually violent (p < .01).

Relationship length and concurrency

The TLFB method was used to calculate relationship length in days for each participant, as well as to record breakups and the presence of concurrent partners. Among participants reporting active dating in the past 90 days, 12% of the participants reported breaking up with and subsequently repartnering with their current partner at least once within the 90-day study period, (M = 0.26 breakups per participant, SD = 0.94). Seven percent of the participants reported two or more concurrent partners during the past 3 months. Among these 10 concurrent relationships, three were nonviolent, one psychologically violent, and five were physically/sexually violent. However, concurrent partnerships did not differ from independent relationships based on the type of DV, χ2(2) = 5.87, p > .05.

GLMs

Depression and delinquency

We examined the relationship between depressive symptoms and delinquency with DV. Given the link between relationship length and DV, we controlled for relationship length in this analysis. We also controlled for the inclusion of multiple relationships per participant with a dummy variable indicating whether or not a participant had multiple relationships included in the analysis. We employed GLM analysis using a multinomial distribution with cumulative logistic link function. The model form provided a good fit to the data, Pearson χ2(63) = 71.58, value/df = 1.14, and the omnibus test of the model coefficients was marginally significant, likelihood ratio χ2(5) = 9.95, p < .10. Parameter estimates indicated that BDI depression score was positively associated with DV, β = .09, Wald χ2(1) = 4.14, p < .05. The odds ratio (OR) for BDI score was 1.10, 95% CI = [1.00, 1.20]. Delinquency was not positively associated with DV, β = .68, Wald χ2(1) = 1.25, p > .05; OR = 1.98 [0.60, 6.58].

Sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behavior

To examine links between sex-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors with DV, we conducted GLM analyses, again controlling for multiple relationships and relationship length, using a Poisson distribution with log link function for dichotomous variables (condom use at last sex and lifetime history of sexual activity) and a normal distribution with identity link for continuous variables (condom use self-efficacy and HIV knowledge). DV was not significantly associated with condom use at last sex, lifetime history of sexual activity, or condom use self-efficacy for relationships that began in the 90-day study window, all ps > .05. DV was significantly associated with HIV knowledge, β = .40, Wald χ2(2) = 24.16, p < .05.

Relationship length and concurrency

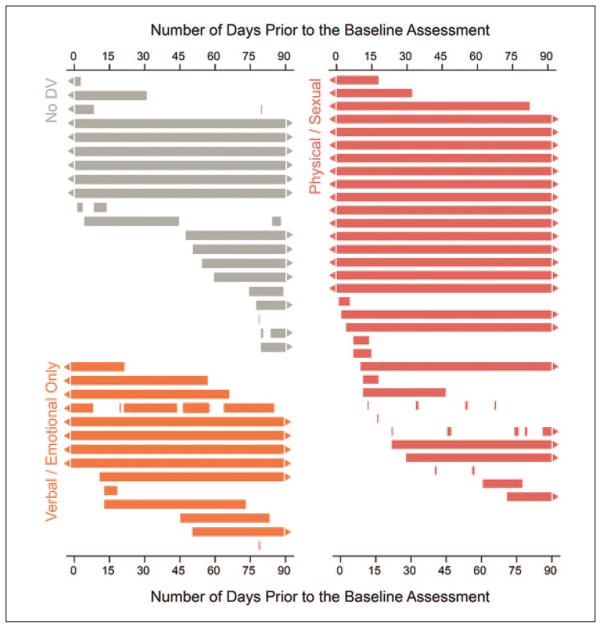

Figure 1 graphically depicts the length of romantic relationship reported by participants during the past 90 days. These relationships are clustered by DV type. As observed in Figure 1, some of the relationships described by our participants preceded the 90-day assessment period (depicted by arrows). For these relationships, we did not have a precise count of the number of days the couple was together. Thus, we were left with 35 relationships that were fully observed within the assessment time frame (i.e., relationships were initiated during the 90-day assessment window; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of days in a romantic relationship by DV type (perpetration and/or victimization).

Note. DV = dating violence.

We used GLMs in SPSS 22.0 to compare differences in relationship length based on DV type (N = 35). We used a GLM for continuous outcomes with a normal distribution and identity link, controlling for the inclusion of multiple relationships per participant with a dummy variable indicating whether or not a participant had multiple relationships included in the analysis. Among relationships that began during the 90-day study period, more physical/sexual violence was associated with longer relationship length, Wald χ2(2) = 1,142.63, p < .001.

Race, Ethnicity, and SES

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3. Results on the primary variables of interest were compared for (a) participants who identified their race as White and students who did not, (b) participants who identified their race as Black and students who did not, (c) participants who identified their ethnicity as Hispanic versus those who did not, and (d) students who did and did not qualify for free or reduced-price school lunch as a measure of SES. Participants’ relationships did not differ in terms of length or DV type based on their race, ethnicity, or SES. There were no individual differences between White and non-White participants or between students who did and did not qualify for reduced lunch. Black students were more likely than non-Black students to have dated in the past 90 days, Pearson χ2(1) = 4.57, p < .05. Hispanic participants reported more HIV knowledge than non-Hispanic students, t(106) = −2.19, p < .05, and were more likely to have dated in the 3 months prior to the study, Pearson χ2(1) = 8.07, p < .01.

Discussion

These data indicate that a selected group of adolescent girls who report a lifetime history of abusive dating relationships present with a broad range of serious behavioral health concerns including clinically meaningful levels of depressive symptoms, serious delinquent behaviors involving aggression, and continued involvement in violent dating relationships. Furthermore, the majority of our sample who reported dating relationships at the time of assessment were involved in violent relationships. This was despite the fact that the majority of our sample rated their acceptance of DV as relatively low. These findings highlight the disconnect between attitudes and behaviors that is often observed in behavioral research. Even more important is the recognition that interventions targeting attitudes alone are unlikely to be adequate for promoting behavior change in this population.

Although 44% of participants reported being sexually active and just above one third did not use a condom at last sex, these rates are comparable with national averages, which estimate that 46% of high school students are currently sexually active and 40% did not use a condom at last sex (Martinez, Copen, & Abma, 2011). Similarly, participant reports of sexual activity and unprotected sex did not differ based on the type of recent or ongoing DV experienced, and multivariate models adjusting for relationship length were not significant. These findings are surprising given research showing that female victims of physical DV are 2.8 times more likely to fear the perceived consequences of negotiating condom use than nonabused girls (Wingood et al., 2001). One possible explanation for our findings is that all participants had prior experience with physical DV and, thus, the dynamics of their non-violent relationships may mirror those of violent ones. Furthermore, given our sample size incidents of sexual coercion that would involve unprotected sex were infrequent.

Interestingly, participants rated themselves as having a high degree of self-efficacy regarding condom use with no differences based on recent or ongoing DV experiences; however, they also lacked knowledge regarding HIV. The combination of high self-efficacy with a lack of understanding regarding HIV and its transmission may put DV-exposed girls at particular risk of HIV and other STIs. In addition, participants with recent DV experiences had even less knowledge about HIV than those in nonviolent relationships. Unlike attitudes and behaviors, knowledge about HIV is most likely acquired through school-based health classes or through conversations with a physician regarding contraception or pregnancy. Individuals with acute DV experiences may have more difficulty accessing this type of information due to the impact of their stressful relationship on recall of factual information. Given these findings, combining efforts to strengthen the knowledge, attitudes, and skills involved in safe sex behavior along with the relevant risk factors for DV may become a best practice in the future.

Another interesting finding relates to the significant association between depression and DV, over and above aggressive delinquency and the length of time in a violent relationship. Depression has been one of the most frequently cited risk factors for DV among adolescent girls (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013) and predicts continued DV and other future health risks. Depressive symptoms are in many ways an ideal target for DV prevention efforts because evidence-based approaches are available for symptom reduction that are well established from years of adolescent mental health research. Cognitive-behavioral approaches target the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that underlie depressive symptoms. Future studies should examine whether depression treatment alone can have a positive impact on DV, as well as whether depressive symptom reduction, in conjunction with traditional DV prevention content, is an effective secondary prevention strategy for affected young women.

As predicted, rates of delinquent acts involving aggression such as carrying a weapon and engaging in fights exceeded expected rates, as less than 10% of adolescent girls present with conduct disorder symptoms (Sholevar & Sholevar, 1995) and even fewer (2%–3%) present with serious delinquency. These findings are consistent with research linking delinquency with non-physical forms of DV such as cyber dating abuse. For example, Zweig and colleagues (Zweig, Lachman, Yahner, & Dank, 2014) found significant associations between adolescent cyber dating abuse and committing a greater number of delinquent behaviors (Zweig et al., 2014). Although aggressive delinquency was not significantly associated with the type of recent or ongoing DV in our sample, the elevated rates among those with a history of physical DV suggests that it may be beneficial to target both issues in preventive intervention programs for this population. A future study that captures additional details regarding delinquency severity could determine whether increased severity of delinquency is associated with increased severity of DV.

Although some studies have identified differences in rates of DV and associations with individual risk factors based on race, ethnicity, and SES, we did not observe these differences in our sample. As with incidents of forced sex, we were underpowered to fully explore these factors. Future research into the contribution of sociodemographic variables is warranted.

One innovative aspect of this study was the use of a TLFB calendar method to obtain relationship data from participants. This method of exploring DV was found to be essential for characterizing the duration of romantic partnerships in our study. The methodology allows researchers to capture the presence, frequency, and duration of each dating partnerships, as well as the frequency of breakups and repartnering with the same or different partner. We found that when relationship length was measured, longer relationships were associated with more physical/sexual DV. Indeed most research on the length of violent relationships suggests a positive link between relationship length and the likelihood of physical violence (Giordano et al., 2010). These findings are important for a number of reasons. First, Ackard, Neumark-Sztainer, and Hannan (2003) found that 50% of girls and boys reporting both physical and sexual DV reported staying in relationships out of fear of physical harm. It is possible that violent relationships are of longer duration due to this fear of breakup. It is also possible that longer relationships simply provide more opportunities for violence to develop (Giles-Sims, 1983). In our sample, the small number of participants who initiated a breakup, got back together with that same partner soon after. This suggests that it may be difficult for this population of DV-exposed girls to fully disengage from romantic relationships that are troublesome.

There are several important limitations to this study. The cross-sectional nature of the survey data makes it difficult to draw conclusions regarding causal relationships. However details from the TLFB interview allowed us to examine some temporal features of the data. In addition, our selected sample of DV-exposed adolescent girls was relatively small. Only a subset of those participants were involved in dating relationships over the assessment period (past 90 days), which further limited the number of observed relationships and, thus, the power to test our hypotheses. However, a strength of the study was the ethnic/racial heterogeneity of our sample as well as the representation of economically disadvantaged youth. Future studies would benefit from an examination of both DV frequency and type to better understand structure and impact of these behaviors.

This study is the first to focus on the individual and relationship characteristics, as well as recent DV experiences, of adolescent girls with histories of physical DV. Given that our study participants are at elevated risk of future violence due to their DV histories, the current study serves as a crucial first step in identifying important targets for intervention. Specifically, our data suggest that interventions for DV-exposed girls should address depressive symptoms as a primary treatment target. Given that aggressive delinquency and sexual risk behavior are related ongoing risks in this population, interventions should further address the underlying mechanisms that link these problem behaviors with DV. Finally, our findings inform assessment practices in research of DV behaviors. Future studies should capitalize on the TLFB method for gathering DV data. The rich information provided may elevate our understanding of relationship processes that confer risk or protection beyond individual factors.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by NIMH Grant K23 MH086328 to Rhode Island Hospital (P.I. Christie J. Rizzo, PhD).

Biographies

Christie J. Rizzo, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Applied Psychology at Northeastern University, Bouvé College of Health Sciences. Her research interests include dating violence and sexual risk prevention for high-risk youth.

Meredith C. Joppa, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at Rowan University. Her research interests include HIV prevention, dating violence prevention, and romantic attachment in adolescence and early adulthood.

David Barker, PhD, is a staff psychologist at Rhode Island Hospital and an assistant professor (research) at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. His research is focused on the social context of health behaviors in pediatric populations and applied statistical modeling in pediatric psychology.

Caron Zlotnick, PhD, is director of behavioral medicine research, Women & Infants Hospital and professor at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. Her research focuses on interpersonal violence and interventions for financially disadvantaged women with depression or posttraumatic stress disorder.

Justine Warren, BA, is a research assistant in the Department of Child & Family Psychiatry at Rhode Island Hospital.

Hans Saint-Eloi Cadely, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of Rhode Island. His primary research area addresses adolescent romantic relationships, change in dating aggression from adolescence to young adulthood, and factors that can contribute to adolescent dating aggression.

Larry K. Brown, MD, is director of research in the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Rhode Island Hospital and professor at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University. He is a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist with a particular interest in HIV and risk behaviors among adolescents and young adults.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Date violence and date rape among adolescents: Associations with disordered eating behaviors and psychological health. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:455–473. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan P. Dating violence among a nationally representative sample of adolescent girls and boys: Associations with behavioral and mental health. Journal of Gender Specific Medicine. 2003;6(3):39–48. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldarondo E, Sugarman DB. Risk marker analysis of the cessation and persistence of wife assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1010–1019. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleyne B, Coleman-Cowger VH, Crown L, Gibbons MA, Vines LN. The effects of dating violence, substance use and risky sexual behavior among a diverse sample of Illinois youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. 4th ed., text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2002;7:313–351. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(01)00061-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory of aggression. Journal of Communication. 1978;28(3):12–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology. 2001;3:265–299. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, Wanner B. Parent and peer effects on delinquency-related violence and dating violence: A test of two mediational models. Social Development. 2002;11:225–244. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Young AM, Sales JM, DiClemente RJ, Rose ES, Wingood GM. Impact of abuse history on adolescent African-American women’s current HIV/STD-associated behaviors and psychosocial mediators of HIV/STD Risk. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma. 2014;23:151–167. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2014.873511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, DiClemente RJ, Beausoleil N. Comparison of HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, intentions and behaviors among sexually active and abstinent young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;13:140–145. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90081-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Lourie KJ, Zlotnick C, Cohn J. The impact of sexual abuse on the sexual risk taking behavior of adolescents in intensive psychiatric treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1413–1415. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field CA, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. The 5-year course of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:1039–1057. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A, Avery-Leaf S, Cascardi M, O’Leary D. Dating violence in two high school samples: Discriminating variables. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 1998;18:431–446. doi: 10.1023/A:1022653609263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00101.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49(1):1–27. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2003.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, Udry RJ. National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence—United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(5):113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding teen dating violence. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/teendating-violence-factsheet-a.pdf.

- Champion JD, Collins JL, Reyes S, Rivera RL. Attitudes and beliefs concerning sexual relationships among minority adolescent women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30:436–442. doi: 10.1080/01612840902770475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase KA, Treboux D, O’Leary DK. Characteristics of high-risk adolescents’ dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17(1):33–49. doi: 10.1177/0886260502017001003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo D, Crooks CV, Wolfe DA, McIsaac C, Hughes R, Jaffe PG. Longitudinal prediction and concurrent functioning of adolescent girls demonstrating various profiles of dating violence and victimization. Prevention Science. 2012;13:350–359. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Schneider-Rosen K. Toward a transactional model of childhood depression. In: Cicchetti C, Schneider-Rosen K, editors. New Directions for Child Development: Childhood depression. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1984. pp. 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Friedlander L, Pepler D, Craig W, Laporte L. The ecology of adolescent dating aggression: Socio-demographic risk factors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2010;19:469–491. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.495028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, McIsaac C. Adolescents’ explanations for romantic dissolutions: A developmental perspective. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:1209–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg G, Emerson E, Bryant F, Wilson H, Weber-Shifrin E. Understanding AIDS-risk behavior among adolescents in psychiatric care: Links to psychopathology and peer relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:642–653. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby K, Campbell J, Sullivan C, Davidson W. Health effects of experiences of sexual violence for women with abusive partners. Health Care for Women International. 1995;16:536–576. doi: 10.1080/07399339509516210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, Kelley ML. The Timeline Followback Spousal Violence Interview to assess physical aggression between intimate partners: Reliability and validity. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:131–142. doi: 10.1023/A:1023587603865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foo L, Margolin G. A multivariate investigation of dating aggression. Journal of Family Violence. 1995;10:351–377. doi: 10.1007/BF02110711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu F, Datta SD, McQuillan GM, Markowitz L. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1505–1512. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Fothergill K, Stuart J. Unpublished technical report. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina; 1992. Results from the teenage dating abuse study conducted in Githens Middle School and Southern High School. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz PA, Smith Slep AM. Stability of physical and psychological adolescent dating aggression cross time and partners. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:303–314. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Sims J. Wife-battering: A systems theory approach. New York, NY: Guilford; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Soto DA, Manning WD, Longmore MA. The characteristics of romantic relationships associated with teen dating violence. Social Science Research. 2010;39:863–874. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt MK, Espelage DL. Social support as a moderator between dating violence victimization and depression/anxiety among African American and Caucasian adolescents. School Psychology Review. 2005;34:309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(91)90007-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Garrido E, Rosenfield D, McDonald R. Experiences of psychological and physical aggression in adolescent romantic relationships: Links to psychological distress. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Yoon J, Langer A, Ro E. Is psychological aggression as detrimental as physical aggression? The independent effects of psychological aggression on depression and anxiety symptoms. Violence and Victims. 2009;24(1):20–35. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer J, Buka S, Gortmaker S, Shrier L. Depressive symptomatology as a predictor of exposure to intimate partner violence among US female adolescents and young adults. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:270–276. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescano C, Brown L, Miller P, Puster K. Unsafe sex: Do feelings matter? Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2007;33:51–62. doi: 10.1300/J005v33n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter EL, McCloskey LA. The effects of childhood exposure to marital violence on adolescent gender-role beliefs and dating violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:344–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00151.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez G, Copen CE, Abma JC. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing, 2006–2010. National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2011;23(31) Retrieved May 4, 2016 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_031.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Lichter EL. The contribution of marital violence to adolescent aggression across different relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:390–412. doi: 10.1177/0886260503251179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Gorman-Smith D, Sullivan T, Orpinas P, Simon TR. Parent and peer predictors of physical dating violence perpetration in early adolescence: Tests of moderation and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:538–550. doi: 10.1080/15374410902976270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Self-reported delinquency: Results from an instrument for New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 1988;21:227–240. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M. Factors mediating the link between witnessing interparental violence and dating violence. Journal of Family Violence. 1998;13(1):39–57. doi: 10.1023/A:1022860700118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Slep AM. A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:314–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCC3203_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orpinas P, Hsieh HL, Song X, Holland K, Nahapetyan L. Trajectories of physical dating violence from middle to high school: Association with relationship quality and acceptability of aggression. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2013;42:551–565. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9881-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Tschann JM, Pasch LA, Flores A. Violence perpetration across peer and partner relationships: Co-occurrence and longitudinal patterns among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j/jado-health.2002.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao U, Hammen C, Daley S. Continuity of depression during the transition to adulthood: A 5-year longitudinal study of young women. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:908–915. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich CL, Gidycz CA, Warkentin JB, Loh C, Weiland P. Child and adolescent abuse and subsequent victimization: A prospective study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:1373–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.003. doi:10/1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts TA, Auinger P, Klein JD. Intimate partner abuse and the reproductive health of sexually active female adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36:380–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph K, Hammen C. Age and gender determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development. 1999;70:660–677. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholevar GP, Sholevar EH. Overview. In: Sholevar GP, editor. Conduct disorders in children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons R, Lin K, Gordon L. Socialization in the family of origin and male dating violence: A prospective study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:467–478. doi: 10.2307/353862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Rutter M. The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1984;55:17–29. doi: 10.2307/1129832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussex B, Corcoran K. The impact of domestic violence on depression in teen mothers: Is the fear or threat of violence sufficient? Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2005;5:109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Dichter ME, Cederbaum JA, Campbell JC. Intimate partner violence, condom use and HIV risk for adolescent girls: Gaps in the literature and future directions for research and intervention. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children & Youth. 2007;8(2):65–93. doi: 10.1300/J499v08n02_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vézina J, Hébert M, Poulin F, Lavoie F, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Risky lifestyle as a mediator of the relationship between deviant peer affiliation and dating violence victimization among adolescent girls. Journal of Youth Adolescence. 2011;40:814–824. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitchurch GG, Constantine LL. Systems theory. In: Boss PG, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, editors. Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 325–353. [Google Scholar]

- Williams TS, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W, Laporte L. Risk models of dating aggression across different adolescent relationships: A developmental psychopathology approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:622–632. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27:539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, McCree DH, Harrington K, Davies SL. Dating violence and the sexual health of black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E72–E75. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman A. Development and validation of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:277–293. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.13.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman A, Grasley C, Reitzel-Jaffe D. Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: A controlled outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:279–291. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig JM, Lachman P, Yahner J, Dank M. Correlates of cyber dating abuse among teens. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(8):1306–1321. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]