Abstract

Key points

Essential hypertension is associated with hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system and hypoperfusion of the brainstem area controlling arterial pressure.

Sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries may regulate blood perfusion to the brainstem.

We examined the autonomic innervation of these arteries in pre‐hypertensive (PHSH) and hypertensive spontaneously hypertensive (SH) rats relative to age‐matched Wistar rats.

Our main findings were: (1) an unexpected decrease in noradrenergic sympathetic innervation in PHSH and SH compared to Wistar rats despite elevated sympathetic drive in PHSH rats; (2) a dramatic deficit in cholinergic and peptidergic parasympathetic innervation in PHSH and SH compared to Wistar rats; and (3) denervation of sympathetic fibres did not alter vertebrobasilar artery morphology or arterial pressure.

Our results support a compromised vasodilatory capacity in PHSH and SH rats compared to Wistar rats, which may explain their hypoperfused brainstem.

Abstract

Neurogenic hypertension may result from brainstem hypoperfusion. We previously found remodelling (decreased lumen, increased wall thickness) in vertebrobasilar arteries of juvenile, pre‐hypertensive spontaneously hypertensive (PHSH) and adult spontaneously hypertensive (SH) rats compared to age‐matched normotensive rats. We tested the hypothesis that there would be a greater density of sympathetic to parasympathetic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries in SH versus Wistar rats irrespective of the stage of development and that sympathetic denervation (ablation of the superior cervical ganglia bilaterally) would reverse the remodelling and lower blood pressure. Contrary to our hypothesis, immunohistochemistry revealed a decrease in the innervation density of noradrenergic sympathetic fibres in adult SH rats (P < 0.01) compared to Wistar rats. Unexpectedly, there was a 65% deficit in parasympathetic fibres, as assessed by both vesicular acetylcholine transporter (α‐VAChT) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (α‐VIP) immunofluorescence (P < 0.002) in PHSH rats compared to age‐matched Wistar rats. Although the neural activity of the internal cervical sympathetic branch, which innervates the vertebrobasilar arteries, was higher in PHSH relative to Wistar rats, its denervation had no effect on the vertebrobasilar artery morphology or persistent effect on arterial pressure in SH rats. Our neuroanatomic and functional data do not support a role for sympathetic nerves in remodelling of the vertebrobasilar artery wall in PHSH or SH rats. The remodelling of vertebrobasilar arteries and the elevated activity in the internal cervical sympathetic nerve coupled with their reduced parasympathetic innervation suggests a compromised vasodilatory capacity in PHSH and SH rats that could explain their brainstem hypoperfusion.

Keywords: hypertension, vertebral/basilar arteries, cerebrovascular resistance, sympathetic innervation, parasympathetic innervation, rat

Key points

Essential hypertension is associated with hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system and hypoperfusion of the brainstem area controlling arterial pressure.

Sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries may regulate blood perfusion to the brainstem.

We examined the autonomic innervation of these arteries in pre‐hypertensive (PHSH) and hypertensive spontaneously hypertensive (SH) rats relative to age‐matched Wistar rats.

Our main findings were: (1) an unexpected decrease in noradrenergic sympathetic innervation in PHSH and SH compared to Wistar rats despite elevated sympathetic drive in PHSH rats; (2) a dramatic deficit in cholinergic and peptidergic parasympathetic innervation in PHSH and SH compared to Wistar rats; and (3) denervation of sympathetic fibres did not alter vertebrobasilar artery morphology or arterial pressure.

Our results support a compromised vasodilatory capacity in PHSH and SH rats compared to Wistar rats, which may explain their hypoperfused brainstem.

Introduction

We proposed previously that blood flow into the posterior cerebral circulation (vertebrobasilar arteries), which feeds the medulla oblongata and pons, is a contributing determinant of the set point of sympathetic activity and arterial pressure in both animals (Paton et al. 2009; Cates et al. 2011, 2012a; McBryde et al. 2017) and humans (Cates et al. 2012b; Warnert et al. 2016). A reduction in vertebrobasilar artery blood flow resulting from stenosis or remodelling/hypertrophy can trigger a Cushing response (Cushing, 1901; Rodbard & Stone, 1955; Schmidt et al. 2005, 2018) resulting in neurogenically mediated hypertension. Moreover, in the spontaneously hypertensive (SH) rat the brainstem is hypoxic and when blood pressure is reduced to normal levels becomes severely hypoxic (Marina et al. 2015). A MRI study reports that human hypertension is associated with hypoperfusion of the brain (Muller et al. 2012) and neuroendoscopy data from humans has shown a clear temporal and quantitative relationship between a rise in intracranial pressure and a subsequent rise in arterial blood pressure to maintain cerebral perfusion within normal limits (Kalmar et al. 2005). These studies led us to the ‘selfish brain hypothesis’ of neurogenic hypertension in which a Cushing mechanism operates to preserve cerebral blood flow at the expense of systemic (essential) hypertension (Paton et al. 2009; Cates et al. 2012a).

In support of the selfish brain hypothesis, we have shown that the vertebrobasilar arteries are both remodelled, with thicker media and narrowed lumen, and have higher vascular resistance in pre‐hypertensive spontaneously hypertensive (PHSH) rats (PHSHRs) compared to age‐matched normotensive control rats (Cates et al. 2011). In humans, we recently reported hypoplastic vertebrobasilar arteries in hypertensive patients including those with white coat and borderline hypertension suggesting that the remodelling of vertebrobasilar arteries occurs before hypertension develops and most probably is congenital (Warnert et al. 2016); thus, the remodelling cannot be secondary to the high blood pressure per se. This is supported by the finding that hydralazine treatment of prenatal and postnatal SH rats (SHRs) does not prevent renal artery wall thickening despite a normalisation of blood pressure during treatment (Smeda et al. 1988). If these early developmental morphological changes are not caused by a high blood pressure stimulus, then what does cause the remodelling?

Sympathetic activity, at least to thoracic viscera, is raised in the early postnatal period in the PHSH rat (Simms et al. 2009). However, it remains unknown whether the sympathetic innervation to the posterior cerebral vasculature is altered in the PHSH rat. Sympathectomy of small mesenteric arteries and resistance vessels has been shown to prevent hyperplastic changes in neonatal SHRs (Lee et al. 1987) and sympathetic innervation was found necessary to increase proliferation of arterial smooth muscle in the ear artery of rabbits (Bevan, 1975) but halted irreversibly when sympathetic nerves were denervated (Bevan & Tsuru, 1981). Treatment of PHSH rats with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor reduced the hypertrophy of renal, splanchnic and cerebral arterial vascular beds (Ibayashi et al. 1986; Harrap et al. 1990; Harrap, 1991) and produced a life‐long ameliorating effect on the development of hypertension (Ibayashi et al. 1986). Thus, the sympathetic nervous system, which can elevate angiotensin II activity, appears to contribute to arterial remodelling seen in SHR from early postnatal life. However, the role of the sympathetic nervous system in driving vascular changes within the vertebrobasilar arteries in the PHSH rat remains unknown.

The aim of this study tested the hypotheses that: (i) there is an age‐dependent increase in the density of the noradrenergic sympathetic innervation of the vertebrobasilar arteries in the developing SH rats relative to age‐matched normotensive controls, and (ii) reducing sympathetic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries in the SH rat regresses their vascular remodelling. Our findings are inconsistent with this hypothesis but support the notion that in PHSH and SH rats the vertebrobasilar circulation is compromised in a way that may limit vasodilatory capacity.

Methods

Ethical approval

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and associated guidelines under project licence PPL 30/3121 and were approved by the Local Ethical Committees on Animal Experimentation at the University of Bristol. The authors confirm that the animal care and experiments conform to the guidelines of The Journal of Physiology (Grundy, 2015).

Subjects

Spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar rats were obtained from Harlan (Loughborough, UK), or were bred from Harlan stock in the animal care facility at the University of Bristol. The animals were maintained in standard environmental conditions (23 ± 2°C; 12 h/12 h dark/light cycle) with water and chow ad libitum.

Neural innervation of the vertebrobasilar arteries

Experiments were performed on juvenile PHSH (4–5 weeks) and adult (12 weeks to 1+ years, to allow ageing data) male SH rats, and normotensive aged‐matched Wistar rats. Twenty‐two PHSH and 34 SH rats were compared to 60 Wistar rats (28 juveniles and 32 adults).

Fixation, isolation and staining of nerves

Rats were killed with Euthatal (pentobarbital sodium 60 mg/kg i.p.) and upon loss of tail reflex perfused transcardially with 100 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Dulbecco A (Oxoid, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rugby, UK)) followed by 200–300 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Merck, Nottingham, UK) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) (from 0.5 M stock: 13.68 g NaH2PO4 (MW: 137.99) and 56.86 g Na2HPO4 (MW: 141.96) per litre ddH2O) pH adjusted to pH 7.3 using 0.8 ml NaOH (10 N) at a flow rate of 35 ml/min. Post‐perfusion, 5–20 ml of blue ink (QUINK, Parker, Lichfield, UK) was injected through the heart to help visualise the posterior cerebral circulation prior to dissection of the meninges. All traces of the ink washed away in the subsequent staining procedures. The ventral meninges containing the vertebrobasilar arteries and vasculature of the circle of Willis was peeled carefully off the brain and post‐fixed further in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight. Standard immunohistochemical (IHC) double labelling ensued on free floating meninges. Dopamine‐β‐hydroxylase (DBH) and vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) plus vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) were used to differentiate between sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres, respectively. We acknowledge that these markers are not unique nor exclusive for these fibre types but they are presently the best immunological markers commonly used to identify autonomic nerves in the cerebrovascular system (Dauphin & Mackenzie, 1995; Edvinsson et al. 2001; Edvinsson & Krause, 2002). We also emphasise immunofluorescence will not necessarily label all fibres present. α‐DBH (Millipore, Watford, UK) is specifically labelling noradrenergic fibres of the sympathetic system, whereas α‐VAChT (Millipore, Watford, UK) and α‐VIP (Novus Biologicals, Oxon, UK) stain the cholinergic and the non‐cholinergic, peptidergic component of parasympathetic fibres, respectively. α‐Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS, Santa Cruz, Insight Biotechnology, Wembley, UK) was also visualised having putative parasympathetic and/or sensory roles. Sensory effector nerves were identified using α‐calcitonin gene related peptide (α‐CGRP, Millipore, Watford, UK). Double staining was performed in four combinations: (1) DBH and VAChT, (2) VIP and VAChT, (3) nNOS and VAChT, and (4) nNOS and CGRP. The first marker in each of the combinations above was visualised using secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor‐594 (AF‐594, red fluorophore) whereas the second marker was conjugated to Alexa Fluor‐488 (AF‐488, green fluorophore); see Table 1 for details of all antibodies employed. All Alexa Fluor‐antibodies were sourced from Invitrogen/Molecular Probes (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rugby, UK). The only exceptions were the goat‐anti‐guinea pig antibody used for secondary labelling of VAChT (Jackson IR, Stratec Scientific, Ely, UK or AbCam, Cambridge, UK) and Streptavidin used as an amplification step for nNOS. Prior to imaging the sections were mounted, dried and cover‐slipped with Vectashield (Vector Labs, Peterborough, UK).

Table 1.

Primary and secondary antibodies employed

| Type | Abbreviated name | Antibody recognising | Host | Clone | Concentration | Supplier | Catalogue no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1° Ab | α‐DBH | Dopamine‐β‐hydroxylase | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:1000 | Millipore | MAB308 |

| 1° Ab | α‐VAChT | Vesicular acetylcholine transporter | Guinea pig | Polyclonal | 1:500 | Millipore | AB1588 |

| 1° Ab | α‐VIP | Vasoactive intestinal peptide | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:200–1:400 | Novus Biologicals (discontinued) | NBP1‐78338 |

| 1° Ab | α‐nNOS | Neuronal nitric oxide synthase | Mouse | Monoclonal | 1:50 | Santa Cruz | SC‐5302 |

| 1° Ab | α‐CGRP | Calcitonin gene related peptide | Rabbit | Polyclonal | 1:100 | Millipore | PC205 |

| Type | Ab recognising | Host | Conjugate | IF‐colour | Concentration | Supplier | Catalogue no. |

| 2° Ab | α‐Mouse | Goat | AF‐594 | Red | 1:500 |

|

|

| 2° Ab | α‐Mouse | Goat | AF‐488 | Green | 1:500 |

|

|

| 2° Ab | α‐Guinea pig | Goat | DyLight‐488 | Green | 1:500 |

|

|

| 2° Ab | α‐Guinea pig | Donkey | Biotinylated | — | 1:500 |

|

|

| 2° Ab | α‐Rabbit | Goat | AF‐594 | Red | 1:500 |

|

|

| 2° Ab | α‐Rabbit | Goat | AF‐488 | Green | 1:500 |

|

|

| Streptavidin | AF‐488 | Green | 1:500 | Invitrogen | S32354 |

Fluorescence microscopy, fibre density measurements and percentage overlap analysis

For quantitative assessment of fibre densities, images were sampled with a 20× objective using a Leica DM5000 light microscope fitted with a Leica DFC300FX digital camera and Leica Acquisition Software (LAS). Imaging was performed to capture as large an area in focus/most fibres visible as possible. We positioned three regions of interest (ROI) windows on the in‐focus areas. Focus was set on the channel (red or green) with the brightest fluorescent labelling. Images of both fluorophores were captured at the same focus. It was our experience that the majority of fibres in the adventitia got captured with the light microscope if the area was flat without folds or on the edge of the artery as this curved away and, hence, these areas were avoided. Three regions along the vertebrobasilar arteries were imaged for analysis (Fig. 1): (1) vertebral arteries (VA) caudal to the vertebrobasilar artery junction; (2) the posterior aspect of the basilar artery (BAp) just rostral to the vertebrobasilar junction; and (3) the anterior aspect of the basilar artery (BAa) caudal to the junction with superior cerebellar arteries. Fibre densities were counted manually for each region by placing these three ROIs covering 0.15 mm × 0.15 mm semi‐randomly on representative areas of the arteries that were in focus. Manual counting was chosen over automatic image analysis, as ridge detection used by Fiji (an open source image processing package based on ImageJ) (Schindelin et al. 2012) for fibre detection cannot account for multiple fibres in bundles and does not allow detection of VAChT fibres due to their punctate appearance. All analyses were performed using these criteria and by the same skilled operator. Fibre densities were calculated as the mean (±SEM ) number of fibres/mm2 in each region at a single focal depth. As the main focus of this paper has been to reveal changes in the autonomic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries in the SH compared to the Wistar rat, the figures focus on the inter‐strain difference, and are displayed according to age. However, age‐related differences within each strain were also examined and are described. The densities for the individual areas for each strain and age are displayed in Figs. 2, 5, 7, 9 and 11. For clarity, the average across the three areas is reported in Results and only pronounced variations from the mean will be further described in the text. The experimenter was ‘blind’ to the animal strain and age at the time of counting. The image quality of the figures has been enhanced for publication using standard Fiji manipulations (background subtraction, brightness and contrast).

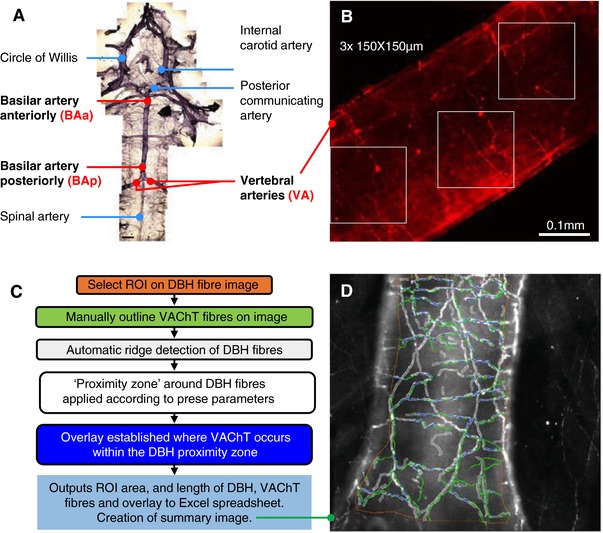

Figure 1. Vertebrobasilar artery peel and analysis of its autonomic innervation.

A, vertebrobasilar arteries in natural light (phase contrast) image. Areas analysed following IHC are indicated in yellow: vertebral arteries (VA), basilar artery anteriorly (BAa) and posteriorly (BAp). Scale bar 1 mm. B, representative red and green channel images (in example: α‐DBH‐594 stained vertebral artery from adult Wistar rat), showing placement of the 3 ‘masks’ (measuring 150 μm × 150 μm) used to demark areas for fibre counting. Areas were positioned semi‐randomly on the vessel that was in focus. The number of fibres in each region was counted, summated and the average fibre densities per square millimetre was calculated. Subsequently the same areas were used for the green channel to assess AF‐488 fibre densities. C, workflow diagram of MIA plugin for Fiji used to analyse % overlap between DBH and VAChT fibres; D, output image showing operator defined ROI (orange), outline of automatically detected DBH fibres with proximity zones applied (white) and operator drawn VAChT fibres (green). Overlays (blue) are defined as where VAChT fibres occur within DBH proximity zones. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

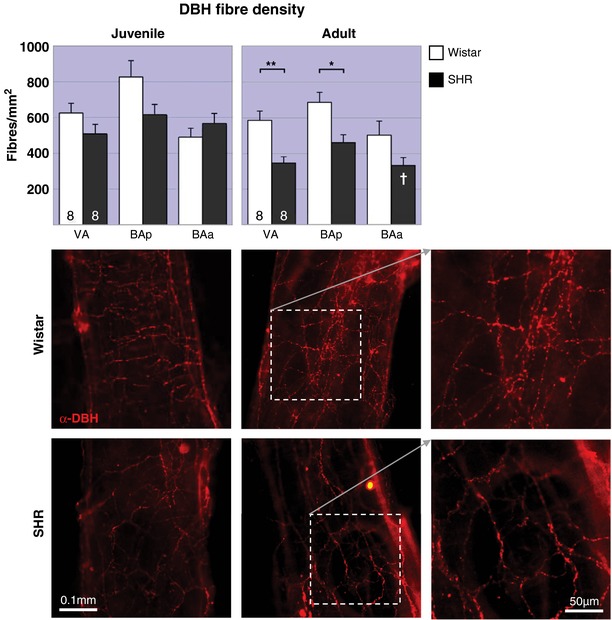

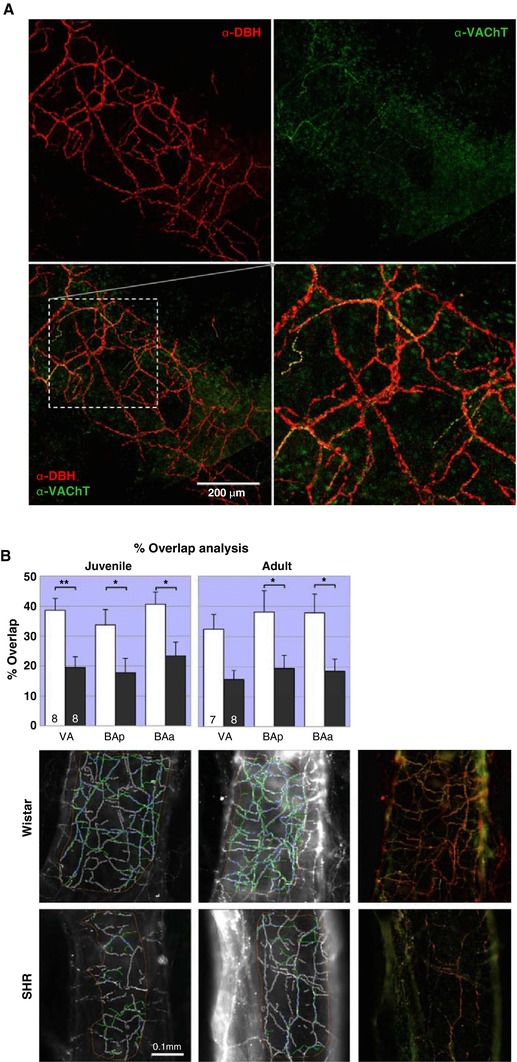

Figure 2. DBH immunofluorescence staining of vertebrobasilar arteries is decreased in adult hypertensive rats.

No change (juveniles, top) or decreased (adult, bottom) sympathetic fibre densities in vertebrobasilar arteries of SHRs (▪) compared to age‐matched Wistar rats (▫). In juvenile rats two‐way RM‐ANOVA found a significant (P < 0.05) interaction of strain × region and a highly significant difference in innervation by region (P < 0.001), but no effect of strain. In adult rats, the effects of both strain and region are highly significant (P < 0.01). The post hoc test reveals the effect is only significant for areas VA and BAp. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. Within strain comparisons found no significant difference in fibre densities in Wistar rats across age, but a significant decrease in the SHRs (P < 0.01). The post hoc test reveals the effect is significant for area BAa (indicated as a white † on the adult panel). † P < 0.05. Both strains had a significant effect of region (P < 0.001 in Wistar and P < 0.01 in SH rats). Representative images of area BAp labelled with α‐DBH‐594 for each group. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

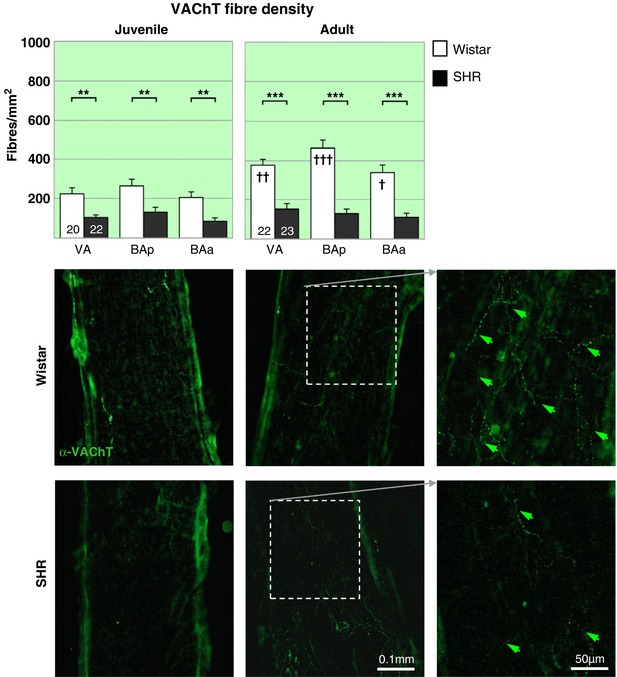

Figure 5. Parasympathetic cholinergic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries is reduced in the hypertensive rat.

A dramatic deficit in cholinergic parasympathetic labelling (α‐VAChT) is evident in both PHSH (top) and SH rats (▪) compared to age‐matched Wistar rats (▫) across the 3 regions. Notably the decrease is prior to the onset of hypertension. The two‐way RM‐ANOVA reveals a highly significant effect of strain (P < 0.001) and a significant effect of region (P < 0.05) for both age groups. Post hoc analyses found the effects significant (P < 0.001) in all regions. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Within strain comparisons found significant difference in fibre densities in the Wistar rats across age (P < 0.001) and with respect to region (P < 0.001), post hoc differences across regions are indicated by † on the adult panel. † P < 0.05, †† P < 0.01, ††† P < 0.001. No differences could be found between the two groups of SH rats. Representative fluorescence microscopy images of area BAp for each group labelled with the cholinergic parasympathetic marker α‐VAChT‐488, including excerpts of adult innervation at higher magnification (far right). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

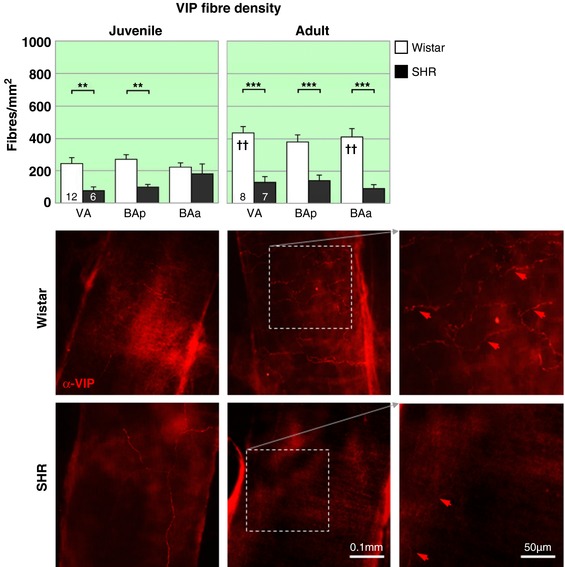

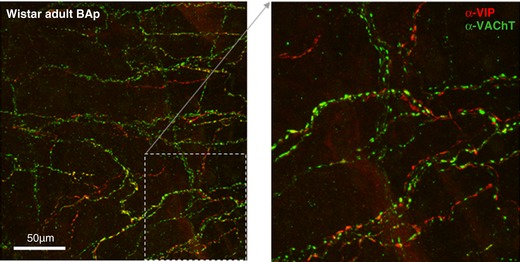

Figure 7. Parasympathetic vasoactive intestinal peptidergic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries is reduced in the hypertensive rat.

The peptidergic VIP parasympathetic labelling is similar to that seen for VAChT. A deficit is evident in both juvenile (top) and adult SHRs (▪) compared to age‐matched Wistar rats (▫). Notably the decrease is prior to the onset of hypertension. The effect of strain, but not region, is significant in juveniles and adults. Regional differences are indicated on the figure. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Within strain comparisons found significant difference in fibre densities in the Wistar rats across age (P < 0.001) but not with respect to region. Post hoc differences in age for each region are indicated by † on the adult panel. †† P < 0.01. In SHRs there was no effect of age or region, but a significant interaction (P < 0.05) between the two groups. VIP fibre densities are significantly higher in Wistar adult rats than juveniles, but no such change is observed in SHRs. Representative fluorescence microscopy images of area BAp for each group labelled with the peptidergic parasympathetic marker α‐VIP‐594, excerpts of adult innervation at higher magnification (far right). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

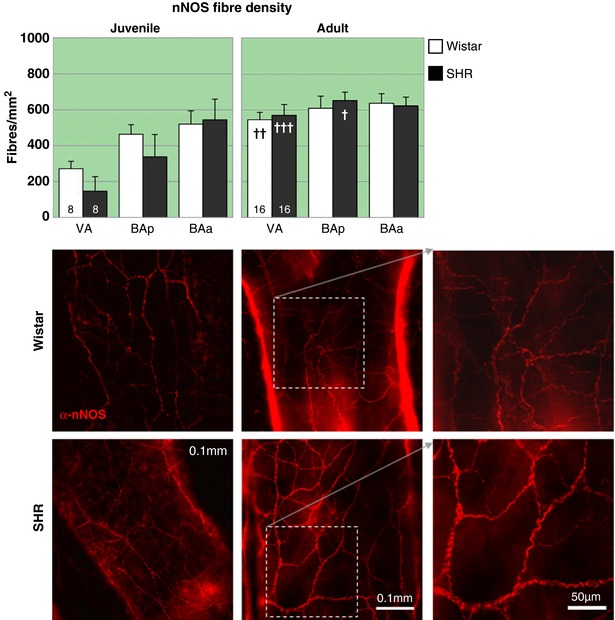

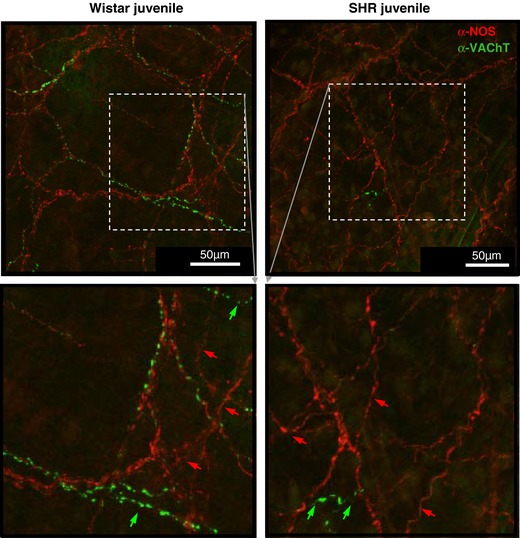

Figure 9. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase immnunopositive fibre labelling is similar between normo‐ and hypertensive rats.

Representative fluorescence microscopy images of BAp for each group labelled with the parasympathetic and sensory effector nerve marker α‐nNOS‐594. There are no strain related deficits in nNOS labelling at any age. In the juvenile rats there is a position (P < 0.01) related dip in innervation with the effect being strongest at positions distal to the circle of Willis, possibly reflecting that the innervation is still developing. There are significant age‐related differences in the amount of nNOS fibres in both strains. In Wistar rats they are significant for VA and in SHRs for VA and BAp (see text for details). † P < 0.05, †† P < 0.01, ††† P < 0.001. Representative fluorescence microscopy images of area BAp for each group labelled with the parasympathetic and sensory effector nerve marker α‐nNOS‐594. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

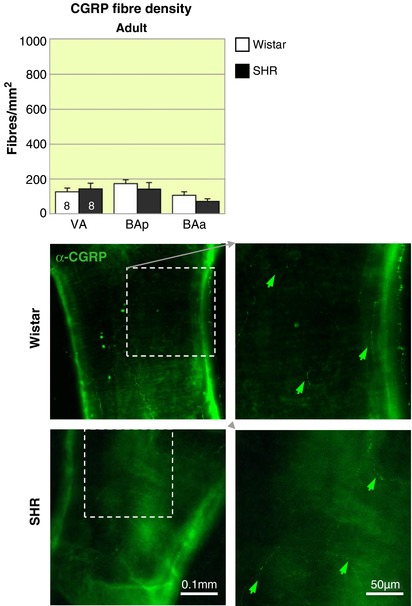

Figure 11. Calcitonin gene related peptide immunofluorescence is similar between Wistar and SH rats.

Representative fluorescence microscopy images of area BAp for adult Wistar rats and SHRs labelled with α‐CGRP‐488 (green arrows). There are no differences in CGRP labelling in Wistar and SHR adult rats. The highest density of CGRP in the regions examined occurs in BAp. The effect of region is significant (P < 0.05). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

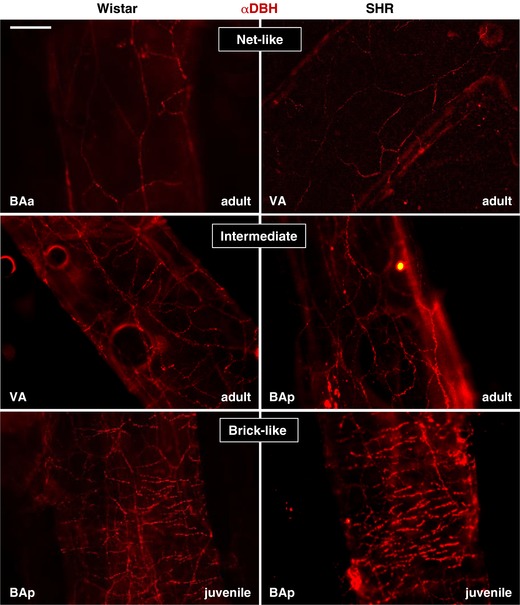

Three different patterns of DBH innervation could broadly be distinguished from the images used for the analysis in Fig. 2: ‘net‐like’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘brick‐like’ (see Fig. 3 for examples). These qualitative differences in innervation patterns were noted according to their location on the vessel and their distribution between rat strains of the two age groups assessed. Note, though ‘net‐like’ fibres tended to have the lowest fibre densities and ‘brick‐like’ the highest, images with equal densities could be categorised to two patterns (overlap was especially common between the ‘intermediate’ and the ‘brick‐like’).

Figure 3. Distinct DBH patterns of innervation based on the location of the vertebrobasilar artery.

Examples of net‐like, intermediate and brick‐like innervation patterns of DBH‐labelled fibres in Wistar (left) and SH rats (right). The location along the vessel and the age of the animal is indicated. Scale bar 100 μm. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

For qualitative descriptions, judgement of co‐localisation, and for illustration purposes some images were acquired on a spectral confocal microscope (SP5‐II confocal laser scanning microscope attached to a Leica DMI 6000 inverted epifluorescence microscope). Images were sampled as z‐stacks equivalent to the total depth of one arterial wall.

To support the argument that reduced vasodilatory capacity is present in SHR compared to Wistar (Chang et al. 2012) rats we compared the percentage of juxtapositioned DBH and VAChT fibres along the total length of DBH fibres; this is referred to as ‘% overlap analysis’. It was beyond study limitations to repeat such analysis for other fibre type combinations. The % overlap analysis was performed with the aid of the ‘Modular Image Analysis (MIA)’ Fiji plugin (Schindelin et al. 2012; Rueden et al. 2017; Cross, 2018) developed by Stephen Cross (Wolfson Imaging Facility, University of Bristol). The plugin semi‐automates detection, length calculation and overlap of DBH and VAChT fibres within a user‐defined ‘proximity zone’ of the DBH fibres (for summary of workflow see Fig. 1 C). DBH fibre detection was automated using the ‘Ridge Detection’ Fiji plugin (Steger, 1998; Wagner, 2017), while the punctate labelling of VAChT fibres necessitated manual selection. Analysis was confined to a hand‐drawn region of interest, with fibres outside this region being discarded. Ridge detection can be tuned for optimal signal‐to‐noise detection using three parameters: upper threshold, sigma and minimum length of fibre. The settings employed by these analyses were, respectively, 0.3–0.5 μm (adjusted according to image quality), 4.0 and 20 μm. Another variable parameter controlling the width of the DBH fibre radius (i.e. ‘the proximity zone’) was iterations in pixels; we employed 1 μm either side of the ridge detected. Hence the ‘proximity zone’ around the DBH fibres was approximately 2 μm across. Results are output to a spreadsheet and an image; an example is shown in Fig. 1 D. The % overlap was calculated as the length of overlay divided by the total length of DBH fibres and expressed as a percentage.

Quantifying sympathetic activity in the multiple sympathetic outflows in situ

Experiments were performed in male PHSH and age‐matched Wistar rats (n = 8 each) using the working heart–brainstem preparation as described previously (Paton, 1996). Briefly, animals were deeply anaesthetised with isoflurane, transected caudal to the diaphragm, exsanguinated and submerged in a cooled Ringer solution (composition in mM): NaCl, 125; NaHCO3, 24; KCl, 3; CaCl2, 2.5; MgSO4, 1.25; KH2PO4, 1.25; dextrose, 10. They were decerebrated at the precollicular level rendering them insentient. Preparations were transferred to a recording chamber and the descending aorta cannulated and perfused retrogradely with Ringer solution containing an oncotic agent (1.25% polyethylene glycol; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and neuromuscular blocker (vecuronium bromide, 3–4 μg/ml), and continuously gassed with 5% CO2 and 95% O2 using a peristaltic pump (Watson‐Marlow 502s, Falmouth, Cornwall, UK). The perfusate was warmed to 31°C, filtered using a nylon mesh (pore size: 25 μm, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and recycled.

Respiratory and sympathetic motor nerves were isolated and recorded using bipolar glass suction electrodes. Phrenic nerve activity (PN) was recorded from its central end intra‐thoracically and the internal (iCSN) and external (eCSN) branches of the cervical and lumbar (lSN) post‐ganglionic sympathetic nerves isolated and recorded. Signals were amplified, band‐pass filtered (AM‐Systems, Sequim, WA, USA; 0.1–5 kHz) and acquired with an A/D converter (CED 1401, Cambridge Electronic Design, CED, Cambridge, UK) to a computer using Spike 2 software (CED). All nerve recording analysis was performed off‐line on rectified and smoothed (50 ms) signals using Spike 2 software with custom‐written scripts. The patterns of respiratory and sympathetic activities were analysed using phrenic‐triggered averages of iCSN and eCSN (generated from 1–2 min epochs of recording), which were divided into three parts: inspiration (coincident with inspiratory PN discharge), post‐inspiration (post‐I; first half of expiratory phase) and second half of expiration (E2). The peak activity of each nerve was set to 100% and the activities observed during the different phases of respiratory cycle were the average values obtained, normalised by the peak of activity. The noise level, which was considered as 0%, was determined 10–20 min after ceasing arterial perfusion at the end of each experiment and subtracted.

In vivo superior cervical ganglionectomy and measuring basilar artery innervation and morphology

A total of 41 male SH rats (12–13 weeks old, Harlan, UK) were employed. Anaesthesia was induced using isoflurane and maintained using a mix of 0.5 ml ketamine (Vetalar, 100 mg/ml), 0.3 ml medetomidine (Dormitor, 1 mg/ml) and 0.2 ml saline injected in a volume of 0.05 ml/100 g (i.m.). Animal temperature was monitored via a rectal probe and maintained on a thermostatically controlled heat pad. Animals were assigned to either septic bilateral superior cervical ganglia resection (SCGx) or sham surgery (SCGsham, as SCGx but leaving SCGs intact) as described by Savastano et al. (2010). The surgical wound was closed with wound clips. Animals were reversed from anaesthesia by subcutaneous injection of atipamezole (Antisedan 5 mg/ml, administered as 0.05 mg/300 g rat). Post‐operative analgesia included administration of meloxicam (Metacam 5 mg/ml, given as 0.3 mg/kg for the first 48 h, s.c.). Procedural success of SCGx was indicated by bilateral eyelid ptosis that persisted until the end of the study.

Animals were kept for 14 days prior to tissue collection. The animals were deeply anaesthetised (pentobarbital, 200 mg/kg) and decapitated at C2. The brain was then gently removed and post‐fixed for 48 h in 10% paraformaldehyde as described previously (Cates et al. 2011).

In some animals, the medulla oblongata was subsequently isolated and embedded into wax for sectioning (10 μm‐thick coronal sections). Sections were collected from the point of vertebral artery convergence (posterior basilar artery) and at 100 μm intervals to its rostral end. After de‐waxing, sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

In other animals, the entire vertebrobasilar arteries were peeled away from the brain and underwent immunocytochemical staining for α‐DBH and α‐VAChT as previously described. Arteries stained with fluorescent probes were imaged on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope with a 20×/0.7 oil/glycerol immersion lens. Images were collected as z‐stacks in a depth containing a complete layer of the adventitia. Fibre densities for the basilar and each vertebral artery were determined using the method previously described and the data expressed as percentage reduction from sham operated animals.

Coronal sections were imaged under a microscope (Zeiss Axioskop2) to make lumen and vessel diameter, and wall thickness assessments. We controlled for distortion of the artery profile by measuring the circumferences (external and lumen) in the image analysis program Fiji using the poly‐selection tool, which measures the circumference of the vessel (regardless of shape) based on the perimeter (P) using the equation: P = 2πr. From this the wall thickness was computed according to Furuyama (1962) and Nordborg et al. (1985).

In vivo blood pressure measurement

A blood pressure sensing device (DSI PA‐C40, AD Instruments, Bella Vista, Australia) was implanted 10 days prior to SCGx/sham surgery. Using similar anaesthetic procedures to those described above, a mid‐line abdominal incision allowed access to the descending aorta at a level rostral to the aortic bifurcation into iliac arteries. During temporary occlusion of blood flow, the aorta was punctured with an 18G needle and the transmitter catheter inserted and advanced towards the heart with its tip caudal to the renal arteries. The catheter was secured with surgical glue (3M Vetbond) and a cellulose patch, and the transmitter was sutured to the abdominal muscle. The wound was closed and repaired with sutures. Analgesia was provided as above.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism versions 6 or 7. For the fibre density study and % overlap assessment, two‐way repeated measures (RM)‐ANOVAs were used to assess the effect of strain or age across the three regions in strain × region or age × region comparisons (reported in text as F and P values) followed by post hoc Sidak's multiple comparison tests (P values only). The outcomes of the post hoc strain and age comparisons are indicated with asterisk or ‘dagger’ (adult panel) for each region on the figures for the strain and age comparisons, respectively. Regional differences were sometimes explored with one‐way RM‐ANOVAs followed by Tukey's multiple comparison tests. Noradrenergic sympathetic innervation change by age was examined with linear regression, testing slope difference from zero and difference in slopes between strains. For changes in the sympathetic activity, data were expressed as means ± SEM and compared using Student's unpaired t test. Blood pressure differences between SCGx and SCGsham were examined using two‐way ANOVA with post hoc Sidak's multiple comparison tests. Statistics for percentage change (from SCGsham) in innervation density following SCGx were performed as t tests for each region. All differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

DBH immunofluorescent innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries in Wistar and SH rats

Fibre densities reported herein reflect the mean across the three regions measured (VA, BAp, BAa). There was no evidence of increased noradrenergic sympathetic fibre density in either rat strain at both age points in all regions studied (VA, BAp and BAa, Fig. 2). Intra‐strain comparisons (post hoc outcomes indicated by dagger symbols in Fig. 2) revealed that Wistar rats displayed no significant difference in noradrenergic sympathetic fibre density with respect to age (647 ± 47 vs. 591 ± 39 fibres/mm2 in juveniles and adults, respectively), but did with respect to region (F 2,28 = 10.4; P = 0.0004) with the highest fibre densities observed in BAp and the lowest in BAa at both ages. The average DBH fibre density in juvenile PHSH rats was 563 ± 32 fibres/mm2; this was reduced by 33% in the adult SH rat to 380 ± 26 fibres/mm2 (F 1,14 = 9.46; P = 0.008) and was significant at the BAa (P < 0.01); DBH innervation density to VA and BAp was comparable across ages.

Comparing the two juvenile rat strains (Fig. 2, top left), DBH fibre density in the PHSH rat was reduced between 19 and 26% posteriorly (VA and BAp) and increased 15% in BAa compared to aged‐matched normotensive rats resulting in a significant interaction (F 2,28 = 4.82; P = 0.016) and effect of position (F 2,28 = 9.322; P = 0.0008) but no significant effect of strain. In the adult rats the differences in DBH fibre densities are even greater. Reductions in SH rats range from 33 to 41% across regions (Fig. 2, top middle) compared to Wistar rats, resulting in significant effects of both strain (F 1,14 = 14.22, P = 0.008) and position (F 2,28 = 6.33, P = 0.005); post hoc analysis found the strain differences were confined to the posterior regions: VA (P < 0.01) and BAp (P < 0.05), but not in BAa.

Sympathetic fibre densities plotted as a function of age for Wistar rats and PHSHRs/SHRs indicated a progressive deterioration in DBH immunopositive fibres with age in SHRs only (P < 0.05 in VA and BAp, and P < 0.001 in BAa). Over the ∼450 days examined, we saw a trend towards a significant difference in slope between Wistar and SH rats for VA (P = 0.08) and BAa (P = 0.06) but not BAp (P = 0.4), data not illustrated.

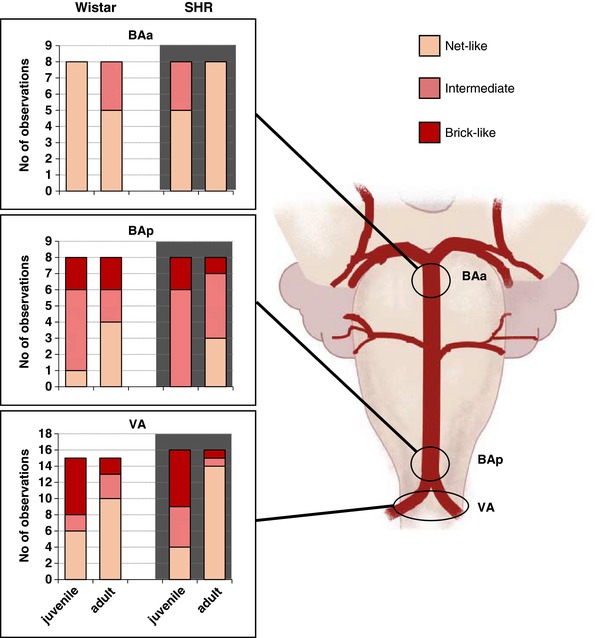

Innervation patterns by DBH immunofluorescent fibres

Three distinguishable patterns of DBH innervation were found (Fig. 3). Their occurrence with respect to location is illustrated in Fig. 4 and described qualitatively here. Please note that these patterns were consistent across all animals.

‘Net‐like’ pattern of fibres running mostly longitudinally or diagonally with the artery was predominantly found on BAa and is generally more prevalent in adults than juveniles.

‘Intermediate’ pattern of innervation – mixture of radially and longitudinally running fibres. This pattern of innervation was predominant in BAp, high in VA, and typically occurred more in juveniles than adults of both strains.

‘Brick‐like’ pattern of fibres, with the majority running radially around arteries, perpendicular to direction of blood flow. This form of innervation was only found in VA and BAp, and was more common in juveniles of both strains. Similar in description to Cohen et al. (1992).

Figure 4. Innervation densities across the vertebrobasilar arteries for juvenile and adult Wistar and SH rats.

Distribution of innervation densities of DBH‐labelled fibres in the 3 regions examined according to age and strain. Note the denser innervation is observed more posteriorly (BAp and VA) and it is more prominent in juveniles than adults. Note, the y‐axis in VA is double that for BAa and BAp as observations have been collected from 2 VAs in each rat. However, the scale is set to allow direct comparisons of proportions. The biggest change in sympathetic innervation density between juveniles and adult is seen in the VA from SHRs. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

‘Parasympathetic’ innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries in Wistar and SH rats

Putative parasympathetic fibres were of smaller fibre diameter compared to DBH immunofluorescent fibres making their visualisation more technically challenging. Because of their multiple neurochemical phenotypes, three approaches were used to assess parasympathetic fibre densities: VAChT (Fig. 5), VIP (Fig. 7) and nNOS (Fig. 9). Note that nNOS is also found in sensory afferent fibres, so co‐staining with VAChT or CGRP was performed to identify either cholinergic parasympathetic or sensory components of nNOS axons (Fig. 11) with the caveat that there may be sensory fibres that do not contain CGRP.

VAChT positive innervation

The majority of VAChT fibres run in close apposition with DBH fibres as illustrated by confocal microscopy (Fig. 6). In Wistar rats, VAChT fibre density (Fig. 5) was approximately half of that measured for DBH axons. VAChT fibre density increased dramatically (73%) from juveniles (227 ± 18 fibres/mm2) to adult Wistar rats (392 ± 22 fibres/mm2; F 1,40 = 15.02; P = 0.0004). Innervation density increased in all arterial regions with the biggest increase in VA and BAp (both significant at P < 0.01, see Fig. 5). As with the DBH staining, the highest VAChT fibre densities were in BAp and the lowest in BAa (overall effect of region: F 2,80 = 8.78; P = 0.0004).

Figure 6. Juxtapositioning of sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres targeting the vertebrobasilar arteries and calculation of % overlap.

A, innervation on vertebral artery illustrating how sympathetic (α‐DBH‐594) and cholinergic parasympathetic (α‐VAChT‐488) fibres tend to run in parallel. The higher ratio of sympathetic to cholinergic parasympathetic innervation is also obvious. Adult male SHR, confocal z‐stack (depth: 25 μm). B, the proportion of DBH fibres with VAChT overlap in SH rats is approximately 20% – half that of Wistar rats (40%). Two‐way RM‐ANOVA revealed a significant effect of strain (P < 0.01) for both juveniles and adults, but no effect of region. In juvenile rats post hoc analyses found the effects strongest in VA (P < 0.01). BAp and BAa were significant (P < 0.05) both in juveniles and adults. * P < 0.05 ** P < 0.01. The within strain comparisons found no differences across ages or regions. Representative images of the Fiji‐MIA analysis output from area BAp for each strain and age are shown with examples of the original images of adult fibre juxtapositions (far left). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

PHSH rats had a VAChT fibre density of 105 ± 11 fibres/mm2 reflecting a 54% reduction compared to aged‐matched Wistar rats (F 1,40 = 16.83; P = 0.0002, Fig. 5), which was exacerbated in adulthood (−67%; F 1,43 = 52.94; P < 0.0001, Fig. 5). Unlike Wistar rats, there was no change in VAChT fibre density with age in hypertensive rats (PHSHR, 105 ± 11 vs. SHR 129 ± 13 fibres/mm2) and no differences in innervation density according to region.

VIP positive innervation

VIP labelling (Fig. 7) closely mirrored VAChT innervation (Fig. 5). Overlap between VAChT and VIP markers was sparse suggesting separate fibre populations (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Juxtapositioning of cholinergic and peptidergic autonomic fibres innervating the vertebrobasilar arteries.

Peptidergic and cholinergic markers sometimes, but far from always, co‐localise in the same fibres. Though the two fibre types tend to run in parallel, in the majority of fibres there is a clear separation of the two markers. Confocal image of α‐VIP‐594 and α‐VAChT‐488 immunofluorescence in the posterior basilar artery in an adult Wistar rat. Flattened confocal 100 μm z‐stack and an excerpt shown at higher power. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In Wistar rats, VIP fibre density increased by 66% during development (juvenile: 246 ± 18 vs. adult: 409 ± 26 fibres/mm2, F 1,18 = 17.39; P = 0.0006) reaching significance in VA and BAa regions (P values < 0.01). In contrast, there was a prominent deficit of VIP labelling in hypertensive rats and this did not change with age (PHSH: 119 ± 24 vs. SH: 114 ± 17 fibres/mm2).

VIP labelling was 51% lower in PHSH rats than in age‐matched Wistar rats (F 1,16 = 14.6; P = 0.0015) and was specific to VA and BAp regions only (P < 0.01). In adult SH rats, all vertebrobasilar artery regions had lower VIP fibre density compared to age‐matched Wistar rats (72%, F 1,13 = 36.14; P < 0.0001). The regional differences in innervation observed with DBH and VAChT were not evident with VIP staining.

nNOS positive innervation

To determine whether nNOS immunopositive fibres were also cholinergic, double staining with VAChT was performed. Although hampered by the fact that the two markers could occupy different segments of the fibres, co‐staining and confocal imaging revealed that the majority of VAChT positive fibres were co‐immunopositive for nNOS (Fig. 10). However, many more nNOS positive fibres without VAChT fibres were also found.

Figure 10. Parasympathetic cholinergic and neuronal nitric oxide synthase fibres: same or distinct axons?

Though the majority of VAChT appear to co‐localise with nNOS positive fibres the two markers seem to occupy different compartments of the fibres, so it difficult to assess if co‐localisation in the fibres is true or if the markers intertwine. Fibres that are only nNOS (red arrows) or only VAChT positive (green arrows) can also be found. The images confirm/reflect the deficit in the cholinergic marker but equal and more labelling of nNOS across the two strains. Confocal images from juvenile Wistar and SHR double labelled with α‐nNOS‐594 and α‐VAChT‐488 immunofluorescence in the posterior basilar artery. Confocal image of flattened z‐stacks through one side of flattened vessel containing the full depth of the adventitia. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The nNOS fibre density (Fig. 9) for juvenile Wistar rats averaged 418 ± 39 fibres/mm2 with lower densities more posteriorly (VA: 271 ± 42 fibres/mm2) and higher densities anteriorly (BAa: 520 ± 75 fibres/mm2). A one‐way RM‐ANOVA (F = 6.7, P < 0.05) found VA to be significantly lower than BAp (P < 0.05) and trending to be different for BAa (P = 0.06). In PSHRs a similar distribution pattern with a lower (18%) mean density was found (average 343 ± 69 fibres/mm2) relative to age‐matched Wistar rats, one‐way RM‐ANOVA (F = 9.5; P < 0.01) with VA smaller than both BAp and BAa (P < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively).

There was no difference between the juvenile rat strains, but the difference in fibre densities at the different locations leads to a significant effect of region (F 2,28 = 15.8, P < 0.0001). In the adult rats, fibre densities are higher and even across all regions relative to their respective juvenile counterparts, and it is also similar between rat strains (mean densities: Wistar rats 597 ± 31 and SHRs 615 ± 30 fibres/mm2, n.s.). The increased fibre density with age is significant for both Wistar (F 1,22 = 6.7; P = 0.02) and SH rats (F 1,22 = 9.3; P = 0.006) and is significant for VA (P < 0.01) in Wistar rats and both VA (P < 0.0001) and BAp (P < 0.05) in SH rats.

CGRP

Labelling with the sensory marker CGRP revealed a small and equivalent distribution of sensory fibres in the vertebrobasilar arteries of adult Wistar and SH rats. Hence there was no evidence for a compensational sprouting of nNOS fibres from sensory fibres in SH rats.

Percentage overlap: VAChT to DBH juxtaposition

In juvenile Wistar rats approximately 40% of DBH fibres are juxtapositioned with VAChT (Fig. 6 B). In PHSH rats this proportion is halved (20%). This was consistent across all three regions studied. There was a significant effect of strain (F 1,14 = 12.3; P = 0.004), but no effect of region. The greatest difference in overlap was on VA (P < 0.01), but also BAp and BAa were significant (P < 0.05). An almost identical picture is present for adult rats showing an effect of strain (F 1,13 = 10.4; P = 0.007), but no effect of region. In the post hoc tests only BAp and BAa reached significance (P values < 0.05). Comparisons between different ages for each strain revealed no significant differences for both age and region.

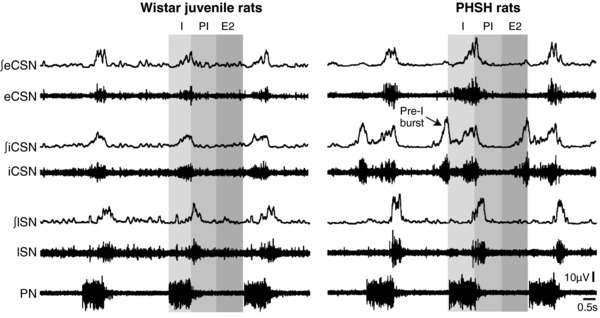

Activity level and pattern recorded from cervical sympathetic branches in situ

We next compared the activity of the internal cervical sympathetic branch (iCSN) known to innervate the basilar artery (Sato et al. 1980; Arbab et al. 1986, 1988; Hesp et al. 2012) between rat strains. In addition, we compared this activity to both the external cervical sympathetic branch (eCSN; which does not innervate cerebral vessels) and the lumbar chain (lSN). As before (Simms et al. 2009), we analysed differences in their respiratory modulation by averaging the percentage of integrated sympathetic activity during the respiratory phases of inspiration, post‐I and E2. Similar to our findings with thoracic sympathetic activity (Simms et al. 2009), the lSN activity peaked during post‐I. In both rat strains, iCSN and eCSN had a higher inspiratory (Wistar: P < 0.05; PHSH: P < 0.05) and lower post‐I modulated sympathetic discharge (Wistar: P < 0.05; n = 8; PHSH: P < 0.05; n = 8) than lSN (Fig. 12). Comparisons between rat strains indicated that PHSH rats showed a higher peak of sympathetic activity during inspiration in both iCSN (PHSH vs. Wistar rats: 22 ± 3.1 vs. 11 ± 1 μV; n = 8, P = 0.0015) and eCSN outflows (PHSH vs. Wistar rats: 17 ± 2.1 vs. 9.7 ± 2.5 μV; n = 8, P = 0.03), and during post‐I in lSN (PHSH vs. Wistar: 24 ± 2 vs. 8.6 ± 0.9 μV; n = 8, P < 0.0001; Fig. 12). Moreover, in PHSH rats, an additional burst of activity during pre‐inspiration was also seen in the iCSN but never in eCSN or lSN outflows (Fig. 12). Thus, in hypertensive rats, the iCSN has both higher activity and a unique pattern compared to other sympathetic outflows and to the same outflow in normotensive rats.

Figure 12. Elevated activity of the sympathetic fibres innervating the vertebrobasilar arteries of hypertensive compared to normotensive rats.

Traces of integrated (∫) and absolute activity of the external cervical sympathethic nerve (eCSN), internal cervical sympathetic nerve (iCSN), lumbar sympathetic nerve (lSN) and phrenic nerve (PN) in juvenile Wistar and PHSH rats. The arrow is indicating the extra component of activity in the iCSN firing (pre‐I burst) occurring prior to the inspiratory activity in PN.

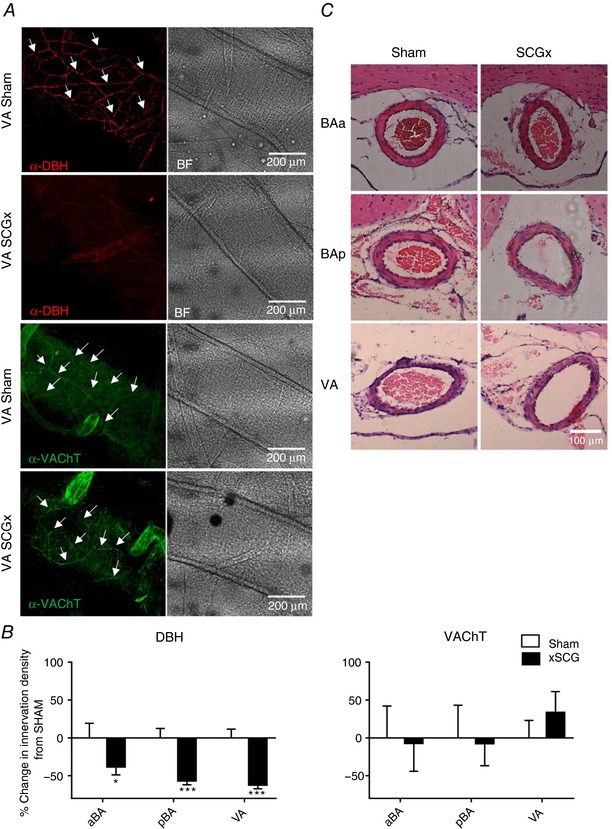

Superior cervical ganglionectomy (SCGx) and vertebrobasilar artery remodelling

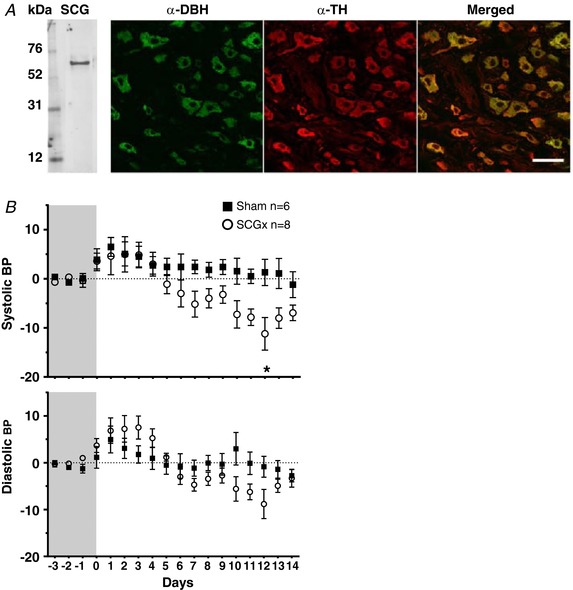

The SCG was verified using tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 13 A). Although there was no increase in the sympathetic innervation density of the vertebrobasilar arteries in hypertensive versus normotensive rats, the elevated activity levels in the internal cervical sympathetic branch in PHSH rats, which contain much of the innervation to these cerebral arteries, could contribute to their remodelling. Thus, we performed bilateral SCGx to reduce the bulk of the innervation of the vertebrobasilar arteries in adult rats. Allowing for 3 days’ recovery from surgery, there was no difference in food or water intake, and no persistent reduction in systolic or diastolic blood pressure (Fig. 13 B), heart rate or ventilatory frequency between SCGx and SCGsham rats up to post‐operative day 14, when animals were culled (not all data shown). There was a significant reduction in DBH immunostaining in SCGx SH rats compared to the SCGsham group (Fig. 14 A). The highest reduction happened posteriorly: 62% for the VA (P < 0.01) and 57% (P < 0.001) on the BAp, whereas a reduction of 38% was seen on the BAa (P < 0.01), Fig. 14 B. There was no significant difference in VAChT immunopositive fibres on any parts of the vertebrobasilar arteries between SCGx and SCGsham groups, Fig. 14 B. The diameters of the BAa, BAp and VA left and right were 247 ± 5, 230 ± 4, 224 ± 8 and 238 ± 7 μm, respectively. However, there was no difference in the lumen diameter, wall thickness and lumen diameter:wall thickness ratio between SCGsham and SCGx SH rats (Fig. 14 C).

Figure 13. Identification of excised tissues as superior cervical ganglion and development in blood pressure following excision.

A, the excised tissue was positive for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) protein as shown by western blotting. Co‐localisation study of α‐DBH and α‐TH showed that cell bodies within the tissue are positive for both tyrosine hydroxylase as well as dopamine‐β‐hydroxylase. All DBH fluorescence is localised to TH fluorescence suggesting that they mark the same structures. Scale bar: 50 μm. B, the blood pressure measurements (in mmHg) were obtained using DSI telemetry. After recording 3 days of baseline, animals underwent either sham or SCGx treatment and blood pressure was recorded continually for 14 days. The traces are presented as difference from the baseline. The systolic and diastolic blood pressure traces of ganglionectomised and sham operated animals are presented as changes from baseline. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 14. Bilateral superior cervical ganglionectomy in SHR attenuates sympathetic fibre innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries but is without effect on their remodelling.

A, representative images of vertebrobasilar arteries showing immunofluorescence staining α‐DBH‐AF594 and α‐VAChT‐AF488 after SCGx or sham operation in SHR and corresponding bright field (BF) images. The arrowheads indicate exemplar sympathetic fibres stained with DBH antibody. B, the reduction in DBH staining is clearly evident after ganglionectomy. Percentage change in sympathetic (DBH positive) and parasympathetic (VAChT positive) fibre densities in SCGx compared to sham animals according to area. Significant differences to normalised sham values are indicated on the graph: * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001. C, coronal images of the basilar and vertebral arteries in SCGx and sham operated SHR. There is no evidence of remodelling in the 14 days since ganglionectomy in SCGx in comparison to sham operated rats. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Discussion

The present study examined the differences in the autonomic innervation of the posterior cerebral arteries of juvenile and adult normotensive and hypertensive rats and whether the noradrenergic sympathetic innervation was responsible for the remodelling led to our previously observed increases in cerebrovascular resistance in the SH rats. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find any evidence for an increase in noradrenergic sympathetic innervation density in the vertebrobasilar arteries in SH compared to age‐matched Wistar rats. However, our data demonstrate for the first time that there are substantial reductions in fibres with presumed parasympathetic function in hypertensive rats that may reduce their capacity for vasodilatation. Our data also purport that the sympathetic innervation from the superior cervical ganglion plays no part in the remodelling of the vertebrobasilar arteries or their parasympathetic innervation in the SH rats.

Limitations and assumptions

Fibre counts were performed manually, and absolute numbers may be questionable as it was not always possible to clearly distinguish exact fibre numbers when bundles were encountered. However, we remain confident that the relative changes we report (rat strain, age, artery region) remain robust. Our fibre counts were based on images analysed using light microscopy over three areas within each segment of the vertebrobasilar artery measured, which provides a snap shot at a single focal depth. Given the size of the axons we believe this is reasonable but acknowledge that confocal imaging may improve fibre resolution and hence accuracy of the absolute densities of fibre types, especially those with small diameters and weaker labelling (e.g. VAChT and CGRP containing fibres may have been missed as their labelling lay on the limit of what was detectable with light microscopic resolution). None of these limitations, however, affect the qualitative traits of our data, as all errors were similar across groups.

Identifying autonomic fibres is confounded by their various guises. It is possible that the sympathetic fibre population could have been expanded using other established markers such as neuropeptide Y (NPY) (however, with the caveat that this marker may also be found in the parasympathetic system). Equally, there is not a single antibody that will, unequivocally, stain all parasympathetic fibres. Because of the overlap in phenotypes within parasympathetic fibres, using a combination of distinct markers does not allow one to sum the total number of fibres. Further, nNOS is present in sensory as well as autonomic fibres. Thus, the present study does not claim to provide an unequivocal fibre density for each population of autonomic nerves innervating the vertebrobasilar arteries, but rather the subgroups of fibres identifiable using conventional immunocytochemical markers. However, using multiple probes targeting the different types of parasympathetic nerves provides more information than a single marker and highlights the different ‘subpopulations’ of this innervation, which may participate differentially in regulating blood flow.

Equally, the semi‐automated workflow employing Fiji (minimising any bias involved in manual counting) comes with certain caveats. DBH fibres are automatically selected by ridge detection. VAChT fibres had to be operator traced. However, the tracing of green fibres was done ‘blind’ as the the operator was unaware of the position of the DBH fibres. We argue that any imprecision in tracing by the operator should be equal across all groups. If multiple strands ran in parallel they were all traced. Hence there is a tendency in this analysis to underestimate DBH fibres as: (1) only one length was counted in bundles containing multiple fibres, (2) the full width of very wide bundles was not accounted for by the 2 μm width setting, and (3) some fibres were not picked out as a result of sensitivity settings, i.e. an inability of the programme to distinguish noise from signal. Equally there is a tendency to proportionally overestimate VAChT fibres: (1) multiple fibres in bundles were traced to ensure full cover of the foot print, and (2) any sign of fibres, even very weak ones, not containing strong punctate fluorescence, were traced (these are particularly present in SHRs). Hence these caveats would work against the observed differences between SH and Wistar rats. Thus, we are confident that any improvement to the analysis would only serve to make the differences found between the two rat strains even bigger.

Sympathetic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries in hypertension

We found no difference in the noradrenergic sympathetic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries between rat strains in the juvenile age group, but an age‐dependent reduction in adult SHRs, particularly in the posterior regions (VA and BAp). For the juvenile age group our results contrast to Dhítal et al. (1988) who, using the glycoxylic acid staining method, found significant increases in sympathetic innervation of basilar arteries in PHSH relative to Wistar rats at ages of 4, 6 and 8 weeks, but not at 12 weeks old. Unfortunately, animals >12 weeks old were not examined by this research group, so any age‐related decline in sympathetic innervation, as we found, could not be known. Age‐dependent decreases in sympathetic innervation have been described previously for normotensive Wistar rats: peak innervation on the BA was obtained at 1–4 months with a 10% decrease at 8 months and 50% at 27 months (Mione et al. 1988).

Previous studies did not utilise α‐DBH‐fibre counts but made comparisons between adult SH and WKY rats using glyoxylic catecholamine fluorescence or noradrenaline content of arteries that included the basilar, and reported increased sympathetic innervation of cerebral arteries of SHR (Lee & Saito, 1984; Mangiarua & Lee, 1990); this was thought to act functionally to restrict these arteries thereby controlling blood flow and preventing stroke. This increased innervation is in stark contrast to our data, where we found a reduction in DBH‐stained fibres in adult (i.e. >12 weeks old) SH versus Wistar rats. This warrants further discussion. We note that Lee & Saito (1984) reported sparse catecholaminergic innervation of the BA–VA junction in adult WKY rats. Our data from Wistar rats (both ages) exhibited dense immunopositive DBH staining of vertebrobasilar arteries. This raises the question of an inter‐strain difference (WKY vs. Wistar; see Rapp, 1987; Kurtz et al. 1989; St Lezin et al. 1992), which could explain the discrepancy with our data, as clearly they would be comparing from a very low level of innervation in WKY relative to SHR. We cannot rule out genetic variation between the SHR rats used here with these previous studies (see Okuda et al. 2002). Differences in the methods used to visualise sympathetic fibres may also play a role. Indirect immunofluorescence appears to stain a larger proportion of nerve fibres compared to DBH immunofluorescence (Schröder & Vollrath, 1985), which would affect comparisons with the data from Lee & Saito (1984) and Mangiarua & Lee (1990). Given our data of differences in innervation (fibre density and pattern) rostro‐caudally along the basilar–vertebral arteries and lack of regional specificity in previous studies, not to mention different techniques used, makes direct comparison of these data with other studies challenging.

Our results also revealed regional differences in the noradrenergic sympathetic innervation from VA and BAp to BAa. These differences were both quantitatively (as fibre densities) and qualitatively different (as in the way the fibres were arranged). Changes in pattern appeared to be more prominent across age than strain and biggest in the VA. Similar patterns of innervation across both anterior (circle of Willis) and posterior cerebral arteries has previously been described by Cohen et al. (1992), but only in adult rats, and no regional differences were reported in the posterior cerebral arteries. At present we have no explanation for the functional significance of the observed differences in regional patterns but speculate they may be related to the need for precise regulation of blood flow to the brainstem.

Sympathetic nerve activity to vertebrobasilar arteries

The functional significance of any nervous innervation is difficult to interpret without knowing the activity levels within the fibres. Thus, we recorded the internal branch of the cervical sympathetic nerve from PHSH and age‐matched Wistar rats (we were unable to record this in adult rats free of anaesthesia), which is known to innervate the anterior basilar artery (Arbab et al. 1986, 1988) and, based on our superior cervical ganglion denervation data, provides some of the innervation to the posterior basilar artery and the vertebral arteries (Fig. 12). Sympathetic activity was respiratory‐modulated, and all respiratory phases of this modulation were higher in the PHSH rat relative to age‐matched Wistar rats. In PHSH rats, we found a novel activity signature from iCSN – a discharge coincident with the pre‐inspiratory phase; the significance of this remains to be determined but it further boosts the overall hyperexcitability of this innervation. This hyperactivity was present in the PHSH rat before both the onset of hypertension and the deficit in sympathetic innervation; whether it persists in adulthood is unknown but based on other sympathetic outflows recorded previously from SHR (Menuet et al. 2017), we would predict it would. One possibility is that this excessive sympathetic activity leads to the demise of the DBH immunopositive innervation as has been found to occur to noradrenergic nerves innervating cardiac tissue in heart failure (Igawa et al. 2000), a condition where sympathetic activity is also raised; this may be a compensatory mechanism preventing noradrenaline‐induced hyperplasia of the vertebrobasilar arteries as can occur in the aorta (Dao et al. 2001).

Vasodilatory role of the sympathetic innervation to vertebrobasilar arteries

It has been argued that in the rat the sympathetic nerves in the basilar artery are not involved in vasoconstriction but vasodilatation (Chang et al. 2012); the latter artery is known to be less sensitive to noradrenaline than non‐cerebral arteries (Lee, 2002). Curiously, sympathetic activation in normotensive rats dilated the basilar artery by stimulation of β2 adrenergic receptors; the latter were proposed to be located on nitrergic nerves thereby triggering NO release (Chang et al. 2012). Based on our observation of decreased sympathetic innervation of the basilar artery in the adult SHR, this may compromise the vasodilatatory capacity of the sympathetic nerves, which was indeed found by Chang et al. (2012). Certainly, the confocal imaging shows that sympathetic nerves run in close proximity to parasympathetic fibres providing the anatomical substrate for crosstalk between sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres and the vasodilatory mechanism as reported by Chang et al. (2012). A reduced vasodilatory capacity of the sympathetic control of the basilar artery in the adult SHR is further supported by our finding of a reduced cholinergic and peptidergic parasympathetic innervation versus aged‐matched Wistar rats. Parasympathetic markers for both cholinergic (VAChT) and peptidergic (VIP) fibres revealed a striking deficit in fibre densities in the PHSH rat. This was suggested in an earlier electron microscopy study but conventional confirmation of parasympathetic nerves using established immuno‐markers was not made (Lee & Saito, 1984). Further, analysis of the percentage of DBH fibres that were juxtapositioned with VAChT (% overlap analysis) demonstrated a 50% reduction in overlap between SHR versus Wistar rats in both age groups, which was independent of the position along the artery. We accept that an analysis of the co‐positioning between DBH to peptidergic and nitrergic parasympathetic fibres would have allowed a more substantiated statement on the limitation of vasodilatory capacity in the SHR but this awaits a future study.

Parasympathetic innervation and vasodilatory role

Although the fibre densities obtained for VIP and VAChT are almost identical, our confocal imaging revealed that in the majority of cases they are not co‐expressed in the same fibres and is consistent with previous observations (Yu et al. 1998) and differences in their origins (Suzuki et al. 1988). If they are indeed separate fibres, then based on our data (see Figs 5 and 7), the total parasympathetic innervation density of VIP + VAChT in normotensive animals is comparable with the sympathetic innervation density (Fig. 2). However, although acetylcholine is a major vasodilator in many peripheral arteries, it does not appear to have major vasodilatory function in the rat basilar artery, but has a modulatory role on NO release from nitrergic nerves, as Chang et al. (2012) discussed above. However, VIP induces vasodilatation via NO mechanisms involving: (i) endothelial cells (Gaw et al. 1991; Gonzalez et al. 1997), (ii) nitrergic nerves (Seebeck et al. 2002), and (iii) a direct action on smooth muscle cells (SMCs) (Grant et al. 2005). Hence, we propose that the deficit in VIP innervation we found in SHR would reduce vertebrobasilar artery vasodilatory capacity. In this context, a limited vasodilatory capacity has been demonstrated in basilar arteries in SHR (Chang et al. 2012) and pial arteries from stroke‐prone SHRs (Coyle & Heistad, 1986) compared to normotensive rats (WKY). Thus, we propose that in hypertension parasympathetic dysfunction is a major problem regarding cerebral blood flow regulation and, as we proposed recently, strategies to circumnavigate this dilatory deficit would be clinically important, especially in conditions of hypertension and stroke (Roloff et al. 2016).

Any attempt to target the autonomic nerves to increase vasodilatory capacity would hinge on an understanding of their origins and pathway trajectories. The sources of sympathetic and parasympathetic input to the vertebrobasilar arteries are somewhat distinct from innervation to the anterior cerebral arteries/circle of Willis (Roloff et al. 2016, for review). Whereas the anterior cerebral circulation receives sympathetic input from the superior cervical ganglion and parasympathetic input from pterygopalatine ganglion, cavernous sinus ganglia, carotid mini‐ganglion and otic ganglia, the vertebrobasilar arteries receive sympathetic input from stellate and superior cervical ganglia whereas the parasympathetic input is derived mainly from the otic ganglia. This division of innervation would potentially enable functional targeting of the separate components of the autonomic system and distinct portions of the cerebral arterial system.

Role of sympathetic nerves in remodelling of vertebrobasilar arteries

We found no change in the relative size of the vertebrobasilar arteries after removing the superior cervical ganglia bilaterally in PHSHR despite the substantial reduction of DBH immunopositive fibres in these vessels. Note that there was no evidence of any change in VAChT immunopositive fibres suggesting that their vitality is independent on this sympathetic input. We conclude that the remodelling of these cerebral arteries in the PHSHR is therefore not due to this innervation but acknowledge that we cannot rule out a role for the innervation that remained, which is likely from the stellate ganglia (Arbab et al. 1988). How these arteries remodel in the SHR remains an open question but mechanisms including that of renin–angiotensin II (Harrap et al. 1990) and immune systems (Waki et al. 2007), which are functionally coupled (Zubcevic et al. 2011; Fisher & Paton, 2012), are possible.

To briefly comment on our nNOS immunostaining, designating nNOS to a functional class of nerve fibres is problematic as it is present in cholinergic and peptidergic parasympathetic and sensory nerve fibres. Unlike VAChT and VIP immunopositive fibres, we found no age‐related deficit in nNOS‐containing fibres on vertebrobasilar arteries of adult SH or normotensive rats. We also examined the number of CGRP fibres in adult rats (where the biggest deficit in the parasympathetic markers were seen) to ensure the high nNOS fibre density in the SHRs was not due to compensatory sprouting in the sensory system. We found no evidence of an increase in sensory fibre innervation in the adult SHR. Also we found no evidence of decreased CGRP functionality in the posterior cerebral arteries of adult SHR, as reported for dorsal root ganglia or mesenteric arteries (Supowit et al. 2001; Hashikawa‐Hobara et al. 2012).

Conclusions and clinical relevance

We believe hypertension in the SHR is associated with a reduced ability to vasodilate hindbrain arteries. This is due to (i) a dramatic, age‐independent attenuation of the parasympathetic modulators VAChR and VIP in SH compared to Wistar rats. There is no change in nNOS, hence no compensation, pointing to a net reduction in vasodilatory capacity. (ii) This is compounded by a reduction of noradrenergic sympathetic innervation of vertebrobasilar arteries in adult versus pre‐hypertensive SHR where these fibres are most likely to be vasodilatory in function as found in a previous study (Chang et al. 2012). These results may explain both the reduced cerebral blood flow and vasodilatory response to increases in metabolic demand in humans with hypertension (Warnert et al. 2016). Such deficits may increase resistance through this vascular bed and would certainly compromise brainstem blood flow and tissue oxygenation as we found in the SHR brainstem (Marina et al. 2015). They may also cause brainstem hypoperfusion during night‐time blood pressure dipping or in patients taking blood pressure lowering medication; the latter may increase susceptibility to non‐haemorrhagic stroke. Thus, future research should examine if harnessing parasympathetic system functionality might restore brain perfusion and alleviate hypoperfusion‐related pathologies such as hypertension, stroke and vascular dementia (Roloff et al. 2016).

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

E.v.L.R., D.W. and D.J.A.M. contributed to the conception or design of the work, acquisition or analysis or interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. S.K. and J.F.R.P. contributed to the conception or design of the work, and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed. Experiments were all performed at the University of Bristol.

Funding

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (RG/12/6/29670), D.W. by the Wellcome Trust (096578/2/11/2) and D.J.A.M. by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (2013/10484‐5).

Other

Parts of the data in this paper have previously been presented at Phys Soc 2012 (Edinburgh), ISH 2012 (Sydney), EB 2014 (San Diego) and ISH 2016 (Seoul).

Acknowledgements

Confocal microscopy and image analysis: the Wolfson Bioimaging Facility, Bristol and the MRC. Special thanks to Dominic Alibhab and Stephen Cross for development of Image J image analysis tools and macros. Sectioning and staining of SCGx brains: Debbie Martin, Debi Ford and Carol Berry in the Histology Services Facility, Biomedical Faculty, University of Bristol.

Biographies

Eva Roloff is a Research Associate specialising in systems physiology and neuroscience. She holds a Masters in Biology from Copenhagen, Denmark (1995) and a PhD from Aberdeen, UK (2003).

Dawid Walas specialises in systems physiology and vascular biology with an interest in Next Generation Sequencing technologies. He holds a Masters in Molecular and Cellular Biology from the University of Glasgow, UK (2011) and a PhD in Integrative Physiology from the University of Bristol, UK (2016). He currently holds a position as a Lead Senior Scientist at Merck KGaA employing Next Generation Sequencing for biosafety testing.

E. v. L. Roloff and D. Walas are equal first authors.

Edited by: Harold Schultz & Julie Chan

References

- Arbab MAR, Wiklund L, Delgado T & Svendgaard NA (1988). Stellate ganglion innervation of the vertebro‐basilar arterial system demonstrated in the rat with anterograde and retrograde WGA‐HRP tracing. Brain Res 445, 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbab MAR, Wiklund L & Svendgaard NA (1986). Origin and distribution of cerebral vascular innervation from superior cervical, trigeminal and spinal ganglia investigated with retrograde and anterograde WGA‐HRP tracing in the rat. Neuroscience 19, 695–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan RD (1975). Effect of sympathetic denervation on smooth muscle cell proliferation in the growing rabbit ear artery. Circ Res 37, 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan RD & Tsuru H (1981). Functional and structural changes in the rabbit ear artery after sympathetic denervation. Circ Res 49, 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates MJ, Dickinson CJ, Hart EC & Paton JF (2012a). Neurogenic hypertension and elevated vertebrobasilar arterial resistance: is there a causative link? Curr Hypertens Rep 14, 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates MJ, Paton JFR, Smeeton NC & Wolfe CDA (2012b). Hypertension before and after posterior circulation infarction: analysis of data from the South London Stroke Register. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 21, 612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates MJ, Steed PW, Abdala APL, Langton PD & Paton JFR (2011). Elevated vertebrobasilar artery resistance in neonatal spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Appl Physiol (1985) 111, 149–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H‐H, Lee Y‐C, Chen M‐F, Kuo J‐S & Lee TJF (2012). Sympathetic activation increases basilar arterial blood flow in normotensive but not hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302, H1123–H1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Z, Bonvento G, Lacombe P, Seylaz J, MacKenzie ET & Hamel E (1992). Cerebrovascular nerve fibers immunoreactive for tryptophan‐5‐hydroxylase in the rat: distribution, putative origin and comparison with sympathetic noradrenergic nerves. Brain Res 598, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle P & Heistad DD (1986). Blood flow through cerebral collateral vessels in hypertensive and normotensive rats. Hypertension 8, II67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross S (2018). “Modular Image Analysis v0.4.8”, April 18 edn. Zenodo, Zenodo.org., 10.5281/zenodo.1219383 [DOI]

- Cushing H (1901). Concerning a definitive regulatory mechanism of the vaso‐motor centre which controls blood pressure during cerebral compression. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 12, 290–292. [Google Scholar]

- Dao HH, Lemay J, de Champlain J, deBlois D & Moreau P (2001). Norepinephrine‐induced aortic hyperplasia and extracellular matrix deposition are endothelin‐dependent. J Hypertens 19, 1965–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin F & Mackenzie ET (1995). Cholinergic and vasoactive intestinal polypeptidergic innervation of the cerebral arteries. Pharmacol Ther 67, 385–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhítal KK, Gerli R, Lincoln J, Milner P, Tanganelli P, Weber G, Fruschelli C & Burnstock G (1988). Increased density of perivascular nerves to the major cerebral vessels of the spontaneously hypertensive rat: differential changes in noradrenaline and neuropeptide Y during development. Brain Res 444, 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvinsson L, Elsås T, Suzuki N, Shimizu T & Lee TJ (2001). Origin and co‐localization of nitric oxide synthase, CGRP, PACAP, and VIP in the cerebral circulation of the rat. Microsc Res Tech 53, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvinsson L & Krause D (2002). Catecholamines In Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2nd edn, ed. Edvinsson L. & Krause D, pp. 191–211. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JP & Paton JFR (2012). The sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: implications for hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 26, 463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuyama M (1962). Histometrical investigations of arteries in reference to arterial hypertension. Tohoku J Exp Med 76, 388–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaw AJ, Aberdeen J, Humphrey PPA, Wadsworth RM & Burnstock G (1991). Relaxation of sheep cerebral arteries by vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and neurogenic stimulation: inhibition by l‐NG‐monomethyl arginine in endothelium‐denuded vessels. Br J Pharmacol 102, 567–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C, Barroso C, Martin C, Gulbenkian S & Estrada C (1997). Neuronal nitric oxide synthase activation by vasoactive intestinal peptide in bovine cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 17, 977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, Lutz EM, McPhaden AR & Wadsworth RM (2005). Location and function of VPAC1, VPAC2 and NPR‐C receptors in VIP‐induced vasodilation of porcine basilar arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26, 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy D (2015). Principles and standards for reporting animal experiments in The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology . J Physiol 593, 2547–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrap SB (1991). Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, regional vascular hemodynamics, and the development and prevention of experimental genetic hypertension. Am J Hypertens 4, 212S–216S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrap SB, Van der Merwe WM, Griffin SA, Macpherson F & Lever AF (1990). Brief angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor treatment in young spontaneously hypertensive rats reduces blood pressure long‐term. Hypertension 16, 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashikawa‐Hobara N, Hashikawa N, Zamami Y, Takatori S & Kawasaki H (2012). The mechanism of calcitonin gene‐related peptide‐containing nerve innervation. J Pharmacol Sci 119, 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesp ZC, Zhu Z, Morris TA, Walker RG & Isaacson LG (2012). Sympathetic reinnervation of peripheral targets following bilateral axotomy of the adult superior cervical ganglion. Brain Res 1473, 44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibayashi S, Ogata J, Sadoshima S, Fujii K, Yao H & Fujishima M (1986). The effect of long‐term antihypertensive treatment on medial hypertrophy of cerebral arteries in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke 17, 515–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igawa A, Nozawa T, Yoshida N, Fujii N, Inoue M, Tazawa S, Asanoi H & Inoue H (2000). Heterogeneous cardiac sympathetic innervation in heart failure after myocardial infarction of rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278, H1134–H1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]