Abstract

Influenza A virus (IAV) and Streptococcus pyogenes (the group A Streptococcus; GAS) are important contributors to viral-bacterial superinfections, which result from incompletely defined mechanisms. We identified changes in gene expression following IAV infection of A549 cells. Changes included an increase in transcripts encoding proteins with fibronectin-type III (FnIII) domains, such as fibronectin (Fn), tenascin N (TNN), and tenascin C (TNC). We tested the idea that increased expression of TNC may affect the outcome of an IAV-GAS superinfection. To do so, we created a GAS strain that lacked the Fn-binding protein PrtF.2. We found that the wild-type GAS strain, but not the mutant, co-localized with TNC and bound to purified TNC. In addition, adherence of the wild-type strain to IAV-infected A549 cells was greater compared to the prtF.2 mutant. The wild-type strain was also more abundant in the lungs of mice 24 hours after superinfection compared to the mutant strain. Finally, all mice infected with IAV and the prtF.2 mutant strain survived superinfection compared to only 42% infected with IAV and the parental GAS strain, indicating that PrtF.2 contributes to virulence in a murine model of IAV-GAS superinfection.

Introduction

Influenza A virus (IAV) is a highly contagious seasonal virus, which causes significant morbidity and mortality. While most IAV infections result in mild to moderate respiratory disease, secondary bacterial infections, or superinfections, substantially exacerbate the illness and increase mortality1. Superinfections associated with IAV are primarily caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pyogenes (the Group A Streptococcus; GAS)2. Periodic IAV pandemics can affect up to 20% of the population and during past pandemics superinfections greatly increased IAV-associated mortality3,4. An analysis of lung biopsies from the 1918 influenza pandemic showed that S. pneumoniae and GAS were the most frequently observed bacteria in the lung and together contributed to approximately 90% of all IAV related deaths5. During the 2009 H1N1 IAV pandemic, S. pneumoniae and S. aureus were the most frequent causes of bacterial superinfection6–9; however, 27% of all deaths due to IAV-bacterial superinfections during this pandemic were associated with GAS, even though GAS is a relatively uncommon cause of pneumonia. Thus IAV-GAS superinfections are relatively uncommon, however the mortality is significant6–10. Studies done during the 1957 pandemic showed that bacteria were attached to lung tissues in areas where the epithelial cell layer had been destroyed by prior viral infection5,11. These and several additional studies (summarized by McCullers)2 indicate that IAV infection enhances bacterial adherence, which increases the severity of disease.

GAS binding to fibronectin (Fn) is among the many ways GAS can adhere to host cells and tissues. IAV infections increase the abundance and accessibility of Fn in several ways. First, IAV infections are thrombotic resulting in increased production in the lungs of Fn and fibrinogen (Fg)12–15, both of which are well characterized GAS ligands. Second, IAV neuraminidase removes sialic acid from the surfaces of host cells thereby increasing the accessibility of potential receptors for adherence, including Fn16,17. Third, IAV neuraminidase activates TGF-β through the cleavage of sialic acids on the secreted TGF-β protein18. This results in a signaling cascade, which induces Fn expression and enhances bacterial adherence (including the adherence of GAS)19–25. Moreover, treating IAV-infected A549 cells with inhibitors of TGF-β signaling decreased Fn expression and the adherence of GAS25.

A variety of GAS proteins bind to Fn and many isolates encode multiple Fn-binding proteins26–33. Mutants created in GAS that lack specific Fn-binding surface proteins are less virulent in animal models of infection, which is consistent with their role in colonization and pathogenesis27,32,33. At least 11 Fn-binding proteins have been identified in various clinical isolates of GAS including Protein F2 (PrtF.2)28,29,31–38. The prtF.2 gene is present in the chromosomes of 36–80% of clinical isolates39–41 and the protein contributes to GAS attachment to, and entry into, epithelial cells35,41. PrtF.2 has 47% amino acid sequence identity with a similar protein named Protein F1 (encoded by prtF.1). Clinical isolates that have the prtF.2 gene, such as strain MGAS315, typically lack prtF.142. The carboxyl termini of both proteins have two separate high affinity Fn-binding domains35,42.

Fn is a dimeric protein composed of two identical monomers. Among each monomer there are three different types of repeating domains. The repeating domains include 12 fibronectin-type I (FnI) domains, 2 fibronectin-type II (FnII) domains, and 15–17 fibronectin-type III (FnIII) domains43. Each FnI domain is approximately 40 amino acid residues in length and is involved in homotypic Fn interactions, as well as the binding of fibrin and collagen. Each FnII domain is approximately 60 amino acids residues in length and binds collagen while each FnIII domain is approximately 90 amino acids residues in length and binds Fn, heparin, and integrins44. All three Fn-domains are present in a variety of functionally diverse proteins among both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

Tenascin C (TNC) is a large hexameric extracellular matrix (ECM) protein which is often co-expressed with Fn in response to tissue damage or inflammation45. Similar to Fn, over half of each TNC monomer is composed of FnIII domains; however unlike Fn, TNC does not have FnI or FnII domains. Group D streptococci bind to TNC, but the streptococcal binding protein is unknown46. Frick et al. reported that the surface-localized GAS adhesion protein known as protein H, which was originally identified as an immunoglobulin-binding protein, binds to FnIII domains present in both TNC and Fn47. These studies indicate that at least some isolates of Streptococci may adhere to cells and tissues by binding to host proteins containing FnIII domains such as TNC.

In this study, we found that the abundance of transcripts encoding proteins with FnIII-domains, including TNC, was greater in IAV-infected A549 cells compared to controls. We created a mutant strain that lacked the Fn-binding protein PrtF.2, and found that the parental strain, but not the mutant, bound to purified TNC. Finally, we showed the mutant strain was attenuated for virulence in a murine model of IAV superinfection compared to the wild-type strain.

Results

IAV infection of A549 cells increases TNC expression

Viral infection modulates host cells in a variety of ways, some of which lead to an increased susceptibility to bacterial infection11,48–53. To identify host cell changes in response to infection with IAV HK68 (H3N2), we compared gene expression between IAV-infected A549 cells and non-infected cells. Two independent experiments were completed. First, we infected A549 cells with 5 × 102 TCID50 (low dose) IAV for 24 hours. Compared to uninfected cells, 403 genes of known function were differentially expressed ≥2-fold (Tables 1 and S1). Second we infected A549 cells with either 5 × 102 TCID50 (low dose) or 105 TCID50 (high dose) IAV for 24 hours. Compared to the controls, 441 and 978 genes of known function were differentially expressed ≥2-fold, respectively (Tables 1 and S1). Many of the changes in gene expression were consistent with results obtained in previous studies. For example, IAV infection was previously found to trigger the production of IFN-α/β and IFN-inducible genes54. Similarly, in our experiments the expression of interferon-inducible genes including ifit1 (237-fold increase), ifit3 (146-fold increase), ifi44 (131-fold increase), and ifi-15K (98-fold increase) was increased in IAV-infected cells compared to controls. The expression of antiviral cytokines including il29 (86-fold increase) and il28a (42-fold increase), as well as chemokines ccl5 (4-fold increase), cxcl10 (62-fold increase), and ccl20 (30-fold increase) was also increased in IAV-infected A549 cells compared to controls. The results indicated that infection of A549 cells with HK68 resulted in a cellular response similar to that observed by other labs using H3N2 IAV strains other than HK6855–57.

Table 1.

Summary of differentially expressed genes (≥2 fold) in response to infection with HK68 IAV in A549 cell lines at 24 hours post infection.

| EXPERIMENT 1 | EXPERIMENT 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 × 102 TCID50 IAV | 363 (+) | 401 (+) |

| 40 (−) | 40 (−) | |

| 105 TCID50 IAV | 942 (+) | |

| 35 (−) |

The number of transcripts which were increased (+) or decreased (−) in IAV-infected A549 cells compared to uninfected A549 cells.

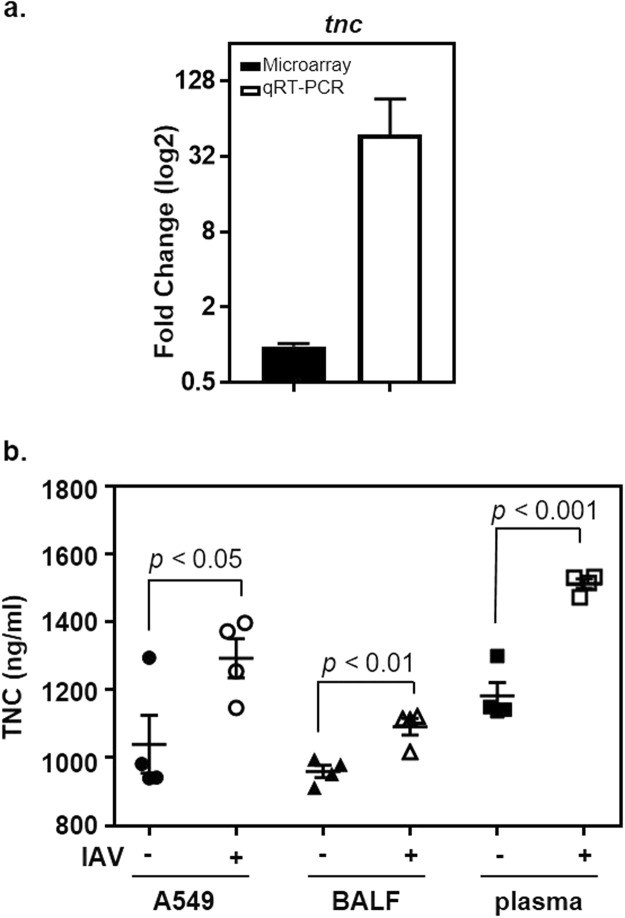

We were particularly interested in the increased abundance of transcripts encoding proteins with FnIII-domains since a prior study47 showed FnIII-domains can facilitate the adherence of at least one strain of Streptococci. Our initial screen showed that expression of the genes tnn (432-fold increase), fank1 (6.5-fold increase), and fndc6 (21-fold increase) were among the most differentially expressed genes encoding FnIII domains. We confirmed the changes by using qRT-PCR (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

IAV infection of A549 cells increased expression of genes encoding FnIII domains. qRT-PCR (open bars) was used to measure transcripts of select genes that were differentially expressed in response to IAV infection (X-axis), as determined by using DNA microarrays (closed bars). The y-axis shows the fold-increase in transcripts associated with IAV-infected cells compared to uninfected controls. Transcripts encoding tenascin N (tnn), fibronectin type III and ankyrin repeat domains 1 (fank1), and fibronectin type III domain containing 6 (fndc6) were measured. The means and sem are indicated.

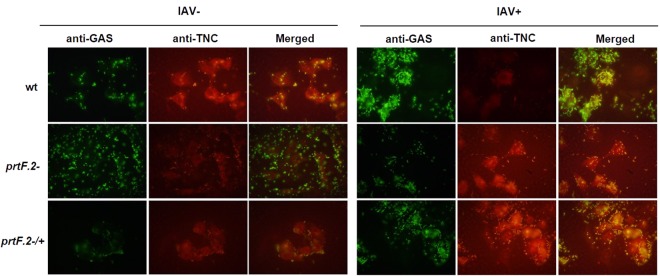

The tenascin family was of particular interest because the proteins have FnIII domains but lack FnI and FnII domains. Results with qRT-PCR showed that tnn transcripts (also known as tnw58) were approximately 13-fold more abundant in IAV-infected cells compared to controls (Fig. 1). While our screening revealed only a slight increase in the expression of the related gene tnc, it was of interest to measure its expression by qRT-PCR because previous reports indicated TNC was a ligand for Streptococcal adherence46,47. Results obtained with qRT-PCR showed that the expression of tnc was approximately 48-fold greater in IAV infected cells compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 2a), which was an increase even greater than that observed with tnn. Although it is unclear why there was a discrepancy in results obtained with arrays and qRT-PCR, qRT-PCR typically has greater specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility59–63. Based on these results, we chose to explore the potential role of TNC in affecting the outcome of IAV-GAS superinfections.

Figure 2.

Increased expression of TNC following IAV infection of A549 cells. (a) The abundance of tnc transcripts was measured with qRT-PCR (open bars) 24 hours after IAV infection (IAV+) of A549 cells and compared to uninfected A549 cells (IAV−). The closed bar shows the results obtained with DNA microarrays. The y-axis shows the fold-increase in transcripts associated with IAV-infected cells compared to uninfected controls. (b) The abundance of TNC was measured in A549 cells 24 hours after IAV infection (IAV+) and compared to uninfected A549 cells (IAV−). Additionally, TNC was similarly measured in BALF and plasma collected from mice 8 days after being inoculated with IAV (IAV+; n = 4 mice) or allantoic fluid (IAV−; n = 4 mice). The mean and sem are indicated. A student’s t-test was used to measure statistical significance.

To determine if the increase in tnc transcripts following IAV infection correlated with increased protein levels, we infected A549 cells with IAV, or not, for 24 hours and measured TNC using an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Fig. 2b). The mean TNC level in uninfected A549 cells (IAV−) was 1,040 ± 171 ng/ml; in contrast, the level was significantly higher (p < 0.05; 1,293 ± 115 ng/ml) after IAV infection (IAV+; Fig. 2b). We also measured TNC in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and plasma obtained from mice 8 days after they were inoculated with either IAV or allantoic fluid as a control. The amount of TNC in BALF was greater in IAV-infected mice (1,092 ± 50 ng/ml) compared to the uninfected controls (960 ± 36 ng/ml; p < 0.01). Similarly, the amount of TNC in plasma was greater in IAV-infected mice (1,512 ± 28 ng/ml) compared to uninfected controls (1,182 ± 79 ng/ml; p < 0.001). Thus, while the magnitude of the increase in TNC abundance following IAV infection did not directly correlate with that of the corresponding transcripts for reasons that are not known, we did observe statistically significant increases in TNC in IAV infected A549 cells, as well as IAV infected mice, compared to uninfected controls.

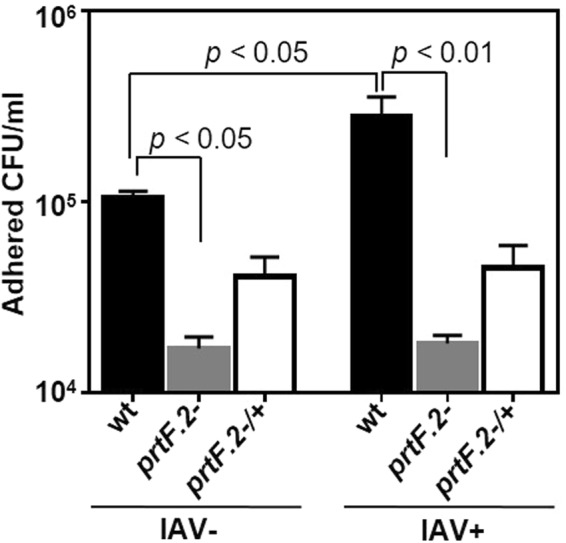

IAV infection of A549 cells increases the adherence of MGAS315

The increased expression of proteins with FnIII domains in IAV-infected A549 cells suggested a potential means for enhanced GAS adherence following viral infection. Multiple Fn-binding proteins have been characterized in GAS; however, PrtF.2 is the predominant Fn-binding protein in strain MGAS31564. We inactivated the prtF.2 gene and measured the effect on adherence to IAV-infected A549 cells and uninfected controls. We also complemented the mutant by transforming it with a shuttle plasmid that expressed the prtF.2 open reading frame from a well characterized GAS promoter (ProfA)39,65–67. A549 monolayers were infected with IAV, or not, for 24 hours and the MGAS315 wild-type strain, the prtF.2 mutant strain (prtF.2−), or the prtF.2 complemented mutant strain (prtF.2−/+) was added and incubated for 1 hour to allow the bacteria to bind to the monolayers. After extensive washing, attached and internalized bacteria were quantified by dilution plating. Among uninfected A549 cells (IAV−), an average of 1.1 × 105 CFU/ml were recovered following the addition of wild-type GAS compared to 0.17 × 105 CFU/ml following the addition of the prtF.2 mutant strain (p < 0.05; Fig. 3). The results were consistent with previous work showing that PrtF.2 contributes to GAS adherence to epithelial cells35,41. Among IAV-infected (IAV+) A549 cells, 2.8 × 105 CFU/ml were recovered following the addition of wild-type GAS compared to 0.18 × 105 CFUs following the addition of the prtF.2 mutant strain (p < 0.01; Fig. 3). Complementation of the mutant strain partially increased adherence, although not to the level of the parental strain and increased adherence to IAV infected cells was not observed for reasons that are not known (Fig. 3). The results indicated that the adherence of wild-type GAS was greater than that of the prtF.2 mutant in the absence of IAV infection (6.5-fold increase), and that the difference was even more pronounced among IAV-infected cells (15.6-fold increase). As previously reported, adherence of GAS to IAV-infected A549 cells was also greater compared to adherence to cells not infected with IAV (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3)13,68. Together, the results confirmed that GAS adherence was partially dependent on PrtF.2 and that a preceding IAV infection increased adherence, some of which was dependent on PrtF.2.

Figure 3.

Inactivation of prtF.2 decreased the adherence of GAS to IAV-infected A549 cells. The number of wild-type (wt), prtF.2 mutant (prtF.2−), or the complemented prtF.2 mutant (prtF.2−/+) bacteria adhered to A549 cells following 24 hours of IAV infection (IAV+) or not (IAV−) was determined by dilution plating. The means and sem are reported. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test was used to measure the significance of the differences among the strains.

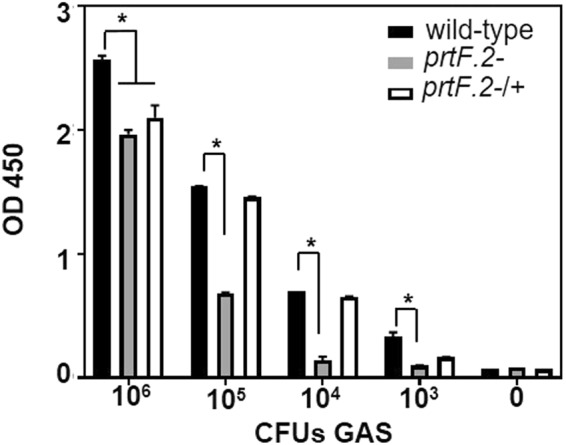

PrtF.2 is required for GAS adherence to immobilized TNC

Proteins with FnI-domains, such as Fn, bind PrtF.235,41. To determine if PrtF.2 can also bind proteins composed mainly of FnIII-domains, we investigated the binding of PrtF.2 to TNC. Purified TNC was immobilized to microtiter plates prior to adding serial dilutions of either the wild-type MGAS315 strain, the prtF.2 mutant (prtF.2−), or the complemented mutant strain (prtF.2−/+). After extensive washing, adherent bacteria were detected by ELISA with an antibody specific to GAS. Wild-type GAS bound to TNC-coated plates, but not to control wells (Fig. 4), and much of the binding was dependent on PrtF.2 (Fig. 4). The binding of the prtF.2 mutant was significantly lower than the wild-type at all concentrations of GAS tested (p > 0.001). Complementation of the prtF.2 mutant increased GAS binding to TNC-coated plates compared to the mutant strain, although binding was not restored to levels observed with the parental strain. The results indicated that GAS bound to purified, immobilized TNC and binding was largely, but not solely, dependent on PrtF.2 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Inactivation of prtF.2 decreased GAS binding to immobilized TNC. The wild-type (wt), prtF.2 mutant (prtF.2−), or the complemented prtF.2 mutant strain (prtF.2−/+) was incubated with immobilized TNC. After extensive washing, bound bacteria were detected with ELISA using antibody specific to GAS. The data are reported as the means and sem. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test was used to measure the significance (*p < 0.001) of differences among the strains.

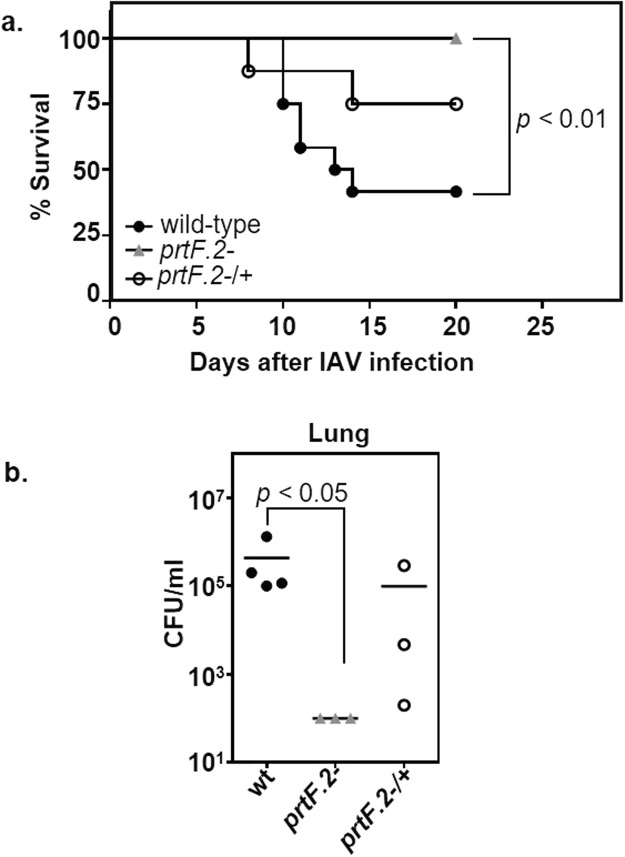

GAS co-localizes with TNC expressed by A549 cells

To determine if GAS co-localized with TNC expressed by A549 cells, we first infected A549 cells with IAV, or not, for 24 hours and then added the wild-type MGAS315, the prtF.2 mutant (prtF.2−), or the complemented mutant (prtF.2−/+) strain for 1 hour. The monolayers were extensively washed and adherent GAS and A459 cells were detected using indirect immunofluorescence with antibodies specific to either GAS or TNC, respectively. The Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) was used to quantify the degree of co-localization between fluorophores69. The coefficient describes how well the red and green pixels are related by a linear equation with 1 being a perfect relationship and 0 being no co-localization relationship between the two fluorophores. Among A549 cells infected with wild-type GAS, the degree of co-localization among TNC and GAS was greater in cells infected with IAV (PCC = 0.82) compared to uninfected control cells (PCC = 0.74; Fig. 5). Interestingly, co-localization was also observed with IAV-infected (IAV+) cells incubated with the prtF.2 mutant strain (PCC = 0.71) but less so with uninfected cells (PCC = 0.572) (Fig. 5). The results indicated that GAS proteins in addition to PrtF.2 can mediate co-localization of GAS to TNC. As observed in previous experiments, complementation of the prtF.2 mutant partially restored the phenotype associated with the parental strain (PCC = 0.81 and 0.67 among IAV infected and uninfected cells, respectively).

Figure 5.

Inactivation of prtF.2 decreased co-localization of GAS to TNC expressed by A549 cells. The co-localization of adhered MGAS315 wild-type (wt), prtF.2 mutant (prtF.2−), or the complemented prtF.2 mutant strain (prtF.2−/+) to TNC expressed by A549 cells infected with IAV (IAV+) or not (IAV−) was determined. Cells were fixed and indirect immunofluorescence was used to detect GAS (green) or TNC (red), with antibodies specific to each protein. Coverslips were imaged with an Olympus BX 60 fluorescent scope (60X magnification) with a Nikon DS camera. Co-localization of GAS and TNC was detected in the merged images.

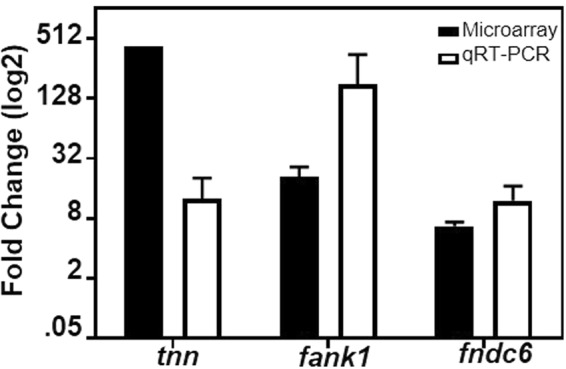

The prtF.2 mutant is less virulent in a murine model of IAV-GAS superinfection

Our results suggested that PrtF.2 was important in GAS interactions with IAV-infected host cells ex vivo; however, it was difficult to ascertain the overall significance of PrtF.2 to the outcome of an IAV-GAS superinfection. This was due, in part, to the finding that the prtF.2 mutant adhered substantially (>104 CFU/ml) to both IAV-infected cells and controls (Fig. 3) and co-localized with TNC expressed by A549 cells infected with IAV (Fig. 4). Therefore, we compared the virulence of the prtF.2 mutant strain to the isogenic parental strain using an established murine model of IAV-GAS superinfection70–72. Groups of mice were first inoculated with a sub-lethal dose of IAV (0.1 LD50). When the mice had recovered from the IAV infection (7 days after IAV inoculation), mice were inoculated with a sub-lethal dose (0.1 LD50) of either wild-type GAS, the prtF.2 mutant (prtF.2−), or the complemented mutant strain (prtF.2−/+). Only 42% of mice superinfected with IAV and the wild-type strain survived (Fig. 6a). In contrast, 100% of the mice infected with IAV and the prtF.2 mutant strain survived, which indicated that PrtF.2 contributes to the virulence of GAS in an IAV superinfection (p < 0.01). 75% of mice superinfected with the complemented prtF.2 mutant strain survived, again indicating that complementation partially restored the parental phenotype.

Figure 6.

Inactivation of prtF.2 decreased the mortality of IAV-GAS superinfected mice and decreased the abundance of GAS in the lower respiratory tract. (a) Mice were infected on day 0 with IAV and on day 7 with wild-type GAS (●; n = 12 mice), the prtF.2 mutant (▲; n = 8 mice), or the complemented prtF.2 mutant strain (○; n = 9 mice). The mortality is indicated as the percentage of mice surviving the IAV-GAS superinfection. A Kaplan Meier survival analysis was used to measure the significance of differences in mortality among the groups. (b) The number of viable bacteria in the lungs of mice infected on day 0 with IAV and on day 7 with GAS was determined 24 hours after inoculation with GAS by dilution plating. Groups of mice were superinfected with wild-type GAS (●; n = 4 mice), the prtF.2 mutant (▲; n = 3 mice), or the complemented prtF.2 mutant strain (○; n = 3 mice). The mean values are indicated. A non-parametric one-way ANOVA with Kruskal Wallis test was used to measure the significance of differences among the strains.

Finally, we also quantified the number of viable GAS in the lungs of superinfected mice 24 hours after GAS inoculation (8 days after IAV inoculation) using groups of 3 to 4 mice, which was previously shown to be a sufficient number to obtain statistically significant results71. A sizeable number of wild-type GAS were recovered from the IAV superinfected mice (4.3 × 105 CFU/ml; Fig. 6b). In contrast, less than 100 CFU/ml (the limit of detection) were recovered from the lungs of mice inoculated with IAV and the prtF.2 mutant strain (p < 0.05). An average of 0.98 × 105 CFU/ml were recovered from the lungs of mice inoculated with IAV and the complemented strain. The results support the idea that PrtF.2 contributes to the ability of GAS to colonize and increase mortality in a host previously infected with IAV.

Discussion

IAV infections create permissive conditions for subsequent bacterial superinfections, which significantly increase the mortality associated with both IAV epidemics and pandemics73. To investigate the host responses to IAV infection that may contribute to this phenomenon, we screened IAV-infected A549 cells for changes in gene expression likely to promote GAS colonization. The most pronounced changes included increased expression of genes encoding proteins with FnIII domains such as tnn, tnc, fank1, and fndc6. Here, we focused on tnc and showed that TNC expressed by A549 cells co-localized with adherent GAS. Furthermore, GAS expressing PrtF.2 bound more efficiently to immobilized TNC compared to an isogenic prtF.2 mutant and inactivation of prtF.2 significantly decreased the virulence of GAS, as determined using a murine model of IAV superinfection. Together, the results suggest that the increased production of TNC in response to IAV may enhance GAS colonization and the severity of infection and that the surface localized protein PrtF.2 contributes to the process.

Elevated TNC expression occurs during inflammation, often in conjunction with Fn production74. This is prominent in the inflamed bronchi of patients with interstitial lung disease or pneumonia75–79. Increased TNC expression also occurs in response to tissue damage, such as that associated with IAV infection80–82. TNC and Fn are both damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which can potentiate tissue damage by increasing the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines83. Thus, increased TNC expression in response to IAV infection is likely to both enhance bacterial colonization and increase immune-mediated tissue damage, thereby exacerbating disease2,49.

A number of studies using RNAseq, microarrays, and quantitative proteomics identified changes in gene or protein expression following IAV infection (reviewed in84). Often these studies focused on changes among genes associated with the immune response and not those likely to directly affect host-cell interactions with bacteria56,57,85–89. However, a study by Lietzen et al. characterized changes in protein abundance among primary human macrophages following IAV infection using H3N2 strains (A/Udorn/1972 and A/Beijing/353/89)90 and showed that IAV infection is associated with a robust increase in the expression of various DAMPs, including Fn90. The results, and ours, are consistent with several other reports of increased Fn expression following IAV infection12,16–18,25,91.

In addition to Fn and TNC, transcripts encoding other GAS ligands were more abundant after IAV infection (Table S1). These included alpha-2-macroglobulin (30-fold increase), which is a plasma protein that inhibits a variety of mammalian proteases. Alpha-2-macroglobulin binds to a GAS surface-localized protein known as GRAB (protein G-related alpha-2-macroglobulin-binding protein)92,93, thereby inhibiting proteolytic degradation of various GAS adhesins and other surface-localized proteins92,93. In addition, transcripts encoding proteins with various collagen domains were more abundant following IAV infection of A549 cells compared to uninfected controls. GAS encodes several different collagen-binding proteins and binding to host collagen types I and IV is an important mechanism of adherence94,95. IAV infection also increased (218-fold) the expression of bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 (BST2/tetherin). BST2 blocks the release of IAV from host cells by binding, or tethering, nascent virions to the membranes of infected cells96. Since GAS (and S. pneumonia)16,17,25,97 bind directly to IAV neuraminidase, progeny virus tethered to the host cell membrane can also promote GAS adherence2,25. Thus, while we focused on TNC interactions with PrtF.2, the results indicated that additional proteins that are also likely to facilitate GAS adherence were more abundant following IAV infection.

Several studies have reported an increase in bacterial adherence to IAV-infected cells compared to uninfected cells. In particular, the increased abundance of Fg and Fn following IAV infection clearly enhances GAS adherence in a manner thought to be largely mediated by the surface localized M protein13,68,98–100. Similar to many bacterial pathogens, GAS adheres to host cells and tissues by utilizing a variety of receptors and adhesins. Many GAS ligands are ECM proteins including Fn, Fg, collagen, and laminin101. Our results contribute to this model and show that another ECM protein, TNC, also facilitates GAS adherence, in part, by binding to PrtF.2.

Our results build on a theme whereby the host response to IAV infection, including the production of a variety of ECM proteins, creates an environment rich in host ligands for GAS adherence. In addition, the increase in soluble ECM proteins can also increase GAS virulence following the recruitment, or binding, of the proteins to the GAS cell surface. We recently showed that the binding of Fg and albumin, which are more abundant following IAV infection, to the surface GAS increased the mortality of mice in an IAV-GAS superinfection71. Thus, the host response to IAV infection is likely to result in increased GAS colonization and persistence through bacterial interactions with multiple host proteins that are elevated in response to viral infection.

Our profile of the transcriptome response of A549 cells to IAV infection showed an increase in the expression of transcripts encoding several proteins known, or suspected, to be ligands for GAS adherence. We focused on the significance of the host ECM protein TNC and the GAS surface-localized protein PrtF.2. Our results highlight the manner in which an increase in the production of ECM proteins, such as TNC, in response to IAV infection is likely to promote bacterial colonization and contribute to the mortality associated with IAV superinfection.

Materials and Methods

E. coli and GAS culture conditions

S. pyogenes strain MGAS315, serotype M3 (ATCC) was grown statically with Todd-Hewitt broth (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (THY) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Routinely, GAS was grown from frozen stocks overnight with THY agar plates at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Colonies were inoculated into pre-warmed THY medium and grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600 = 0.5). When appropriate, the prtF.2 mutant, or complemented mutant strains, were grown with THY containing erythromycin (2.5 μg/ml) or kanamycin (500 μg/ml), respectively. Escherichia coli strain DH5α (Gibco; Gaithersburg, MD) was grown with Luria Bertani (LB) medium. When appropriate, erythromycin (200 μg/ml) was added to LB broth.

GAS mutagenesis

The prtF.2 gene was insertionally inactivated, essentially as previously described102. The prtF.2 gene was amplified using the primers PrtF2_F1 (5′-GCTTGAATTCAAACGACAGTTCCGGCTGAT-3′) and PrtF2_R1 (5′-GCTTAAGCTTTCAGGTCATCCACTGCTAC-3′). The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and HindIII resulting in a 350 bp internal fragment that was gel purified and cloned into the vector pVA981-2, which replicates episomally in E. coli but not in S. pyogenes103. Following transformation of E. coli strain DH5α (Gibco-BRL, USA), the recombinant plasmid, designated pVA981-2::prtF.2, was isolated and electroporated into strain MGAS315. Transformants were selected with THY agar plates containing erythromycin (2.5 μg/ml) and insertional inactivation of prtF.2 was verified with PCR. The ORF downstream of prtF.2 is transcribed in the opposite direction compared to prtF.2 and the ORFs are separated by 264 bp of non-coding DNA. The prtF.2 mutant strain was complemented with the shuttle plasmid pAH1, which was derived from the streptococcal expression plasmid pMNN2365. To do so, the ropB ORF in pMNN23 was excised with BamH1 and Pst1. In its place, a DNA fragment consisting of the prtF.2 ORF was cloned. The resulting shuttle plasmid consisted of the prtF.2 ORF cloned adjacent, and downstream, of the rofA promoter. The native, or chromosomal rofA promoter controls the expression of the surface localized fibronectin protein Protein F or PrtF104. The recombinant plasmid construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing. pAH1 was purified and electroporated into the MGAS315 prtF.2 mutant strain. Transformants were selected with THY agar plates containing kanamycin. The growth curves of the MGAS315 wild-type, prtF.2 mutant, and the complemented mutant strains were identical (Supplementary Fig. 1).

IAV virus strain

Influenza virus (A/Hong Kong/1/68-H3N2; HK68) was created using the PR8 reverse genetic system as described105 and propagated at 35 °C for 72 hours in the allantoic cavities of 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs72,105. As described previously72, virus were sequenced and titers were determined by TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose) using MDCK (Madin-Darby Canine Kidney Epithelial Cells).

Total RNA isolation

Monolayers of human adenocarcinomic alveolar epithelial (A549) cells (6 × 105 cells/ml) were infected with IAV at 5 × 102 TCID50, or 105 TCID50 IAV. After one hour, the inoculum was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with media containing 1 µg/ml TPEC trypsin for 24 hours at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Total RNA was extracted from control A549 cells and IAV-infected A549 cells at 24 hours post-IAV infection using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNA was purified with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA purity and quantity was evaluated with Agilent chips (Agilent RNA 600 Nano kit).

Microarray data analysis

Three independent microarray experiments were done with Codelink Whole Human Genome Bioarrays from Applied Microarrays (Tempe, AZ), as previously described106. Briefly, semi-confluent A549 monolayers were infected with 5 × 102 TCID50, (low dose), 105 TCID50 IAV (high dose), or mock infected (no virus) for 24 hours and RNA was extracted. To identify differently expressed genes, we normalized data (test/reference) of IAV-infected cells (test) and control treated A549 cells (reference). Differentially expressed genes at the cut-off of fold change ≥2 are listed in Table S1.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase - PCR

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (qRT- PCR) was done using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI 7300 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). The comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method was used to quantitate transcript abundance. The ΔΔCt value was calculated by difference in normalized Ct value (ΔCt) from infected (IAV+) samples to the ΔCt from non-infected (IAV−) samples. The ΔΔCt value was transformed into 2ΔΔCt value as the estimated gene expression fold change value. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh) was used as an internal control. qRT- PCR was done in duplicate with 5 independently isolated RNA samples.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were completed as described previously107. 96-well plates were coated with 5 μg/mL TNC diluted with 0.1 M sodium carbonate (pH 9.8). Plates were blocked with 1% BSA, washed using PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), and serial dilutions of GAS cells (wild-type MGAS315, the prtF.2 mutant, or the complemented mutant strain) were added and incubated for 2 hours at 37 °C. Plates were washed again with PBS-T, and anti-GAS antibody (ThermoFisher; 1:1000 dilution) added and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing with PBS-T, HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (1:10,000 dilution) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at room temp. After washing, One-Step-TMB Turbo substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was added and the OD measured at 450 nm using a Biotek EL808 plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT). End-point titers are presented as the reciprocal serum dilution corresponding with the last well demonstrating an OD450 of 0.1 in the titration curve.

To quantify TNC expression in A549 cell-culture supernatants, mouse BALF and plasma, an ELISA was used according to the manufactures instructions (Abcam; Cambridge, United Kingdom). Briefly, A549 cells were infected with 5 × 102 TCID50 IAV or mock infected (no virus) for 24 hours and whole-cell lysates were collected. For animal fluids, mice were infected with 0.1 LD50 IAV or allantoic fluid for 8 days and fluids were collected. 100 µl of purified TNC or 100 µl (diluted 1:10 or 1:100) of each sample was added to anti-TNC pre-coated microtiter plates and incubated for 90 minutes at 37 °C. Biotinylated-TNC antibodies (diluted 1:100) were then added for 60 minutes at 37 °C; plates were washed 3 times with PBS-T and avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (diluted 1:100) was added. Plates were again washed thoroughly and 90 µl TMB substrate was added and color allowed to develop for 20 minutes. OD was measured at 450 nm using a Biotek EL808 plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT).

GAS attachment to A549 cells

A549 cell monolayers (6 × 105 cells/ml) were washed thoroughly with PBS and infected with 5 × 102 TCID50 IAV. After 1 hour the viral inoculum was removed, the cells were washed, and media containing TPEC trypsin (1 µg/ml) added and the cells incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After 24 hours, cells were again washed and GAS diluted with culture media to a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 (6 × 107 CFU’s) added. Monolayers were centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 minutes to facilitate contact between GAS and the A549 cells and incubated for 60 minutes at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Monolayers were then washed to remove non-adherent bacteria. The number of adherent and intracellular bacteria was enumerated after detachment of cells with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA for 1–2 minutes at 37 °C with 5% CO2 followed by serial dilution plating with THY agar plates. The results from 3 independent experiments, each done in duplicate, are shown.

Microscopy

A549 cell monolayers (6 × 105 cells/ml) were infected with 5 × 102 TCID50 IAV for 24 hours and then fixed with 100% ethanol for 20 minutes at −20 °C. Coverslips were incubated with primary antibodies against TNC (ThermoFisher; dilution 1:1000), Fn (Abcam; Cambridge, United Kingdom; dilution 1:1000), or GAS (ThermoFisher; dilution 1:5000), followed by incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to DyLight fluors (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; West Grove, PA; dilution 1:10,000). Coverslips were mounted onto glass slides and imaged with an Olympus BX 60 fluorescent scope (60X magnification) with a Nikon DS camera. The integrated density was calculated from the fluorescent intensity and area of the A549 cells which was determined with ImageJ v1.48 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The integrated density of the background (shape similar in size to A549 cells) was measured and subtracted from cell measurements. A total of 17–25 fields of view were imaged from 3 independent experiments each done with duplicate coverslips.

Murine model of infection

All experiments were conducted in conformity with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Experiments completed under animal protocol number 11-07015-18E were approved by the local animal care committee (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) of the University of South Dakota. Female (6 to 8-week-old) BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and housed in groups of four with 24-hour access to food and water. The IAV-GAS superinfection model was previously described70. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and inoculated intranasally with 100 µl of a sub-lethal dose [0.1 LD50 (104.75 TCID50)] of IAV at day 0. Seven days later anesthetized mice were inoculated intranasally with 100 µl of a sub-lethal dose [0.03 LD50 (106 CFU)] of GAS. Experiments were completed using 8–12 mice per group. BALF and plasma were collected from mice as described previously71.

GAS quantification in the lungs of mice

To enumerate viable GAS present in the lungs of mice, groups of 4 mice were euthanized 24 hours after inoculation with MGAS315 and lungs collected. GAS were enumerated by dilution plating on blood agar (TSA with 5% sheep blood) plates as previously described70.

Statistics and image production

All quantification and statistical analyses of data was performed with GraphPad Prism 6 software. Statistical analyses included a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test, Kaplan Meier survival analysis, or a Student’s t-test, as appropriate.

Data availability

Datasets (Raw and processed data) generated and analyzed during the current study are available from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE112215.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance of Kuta Suso and Abby Simon. This work was supported by 1R15AI094437-01A1 and P20GM103443.

Author Contributions

M.S.C., V.C.H. and A.L.H. conceived the experimental ideas and directed their completion. K.E. completed the microarray experiments. H.F., D.M., L.A., L.F. completed the experiments. A.L.H. wrote the majority of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-29714-x.

References

- 1.Metersky ML, Masterton RG, Lode H, File TM, Jr, Babinchak T. Epidemiology, microbiology, and treatment considerations for bacterial pneumonia complicating influenza. International journal of infectious diseases: IJID: official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2012;16:e321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCullers JA. The co-pathogenesis of influenza viruses with bacteria in the lung. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2014;12:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson WW, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. Jama. 2003;289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCullers JA, Huber VC. Correlates of vaccine protection from influenza and its complications. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2012;8:34–44. doi: 10.4161/hv.8.1.18214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morens DM, Fauci AS. The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007;195:1018–1028. doi: 10.1086/511989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacterial coinfections in lung tissue specimens from fatal cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) - United States, May-August 2009. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report58, 1071–1074 (2009). [PubMed]

- 7.Surveillance for pediatric deaths associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection - United States, April-August 2009. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report58, 941–947 (2009). [PubMed]

- 8.Jain S, et al. Hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, April–June 2009. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:1935–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Louie JK, et al. Factors associated with death or hospitalization due to pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in California. Jama. 2009;302:1896–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jean C, et al. Invasive group A streptococcal infection concurrent with 2009 H1N1 influenza. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;50:e59–62. doi: 10.1086/652291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memoli MJ, Morens DM, Taubenberger JK. Pandemic and seasonal influenza: therapeutic challenges. Drug discovery today. 2008;13:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller TT, et al. Effects on coagulation and fibrinolysis induced by influenza in mice with a reduced capacity to generate activated protein C and a deficiency in plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. Circulation research. 2006;99:1261–1269. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250834.29108.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanford BA, Davison VE, Ramsay MA. Fibrinogen-mediated adherence of group A Streptococcus to influenza A virus-infected cell cultures. Infection and immunity. 1982;38:513–520. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.513-520.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beachey EH, Courtney HS. Bacterial adherence: the attachment of group A streptococci to mucosal surfaces. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1987;9(Suppl 5):S475–481. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.Supplement_5.S475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson WA, Courtney HS, Ofek I. Interactions of fibronectin with streptococci: the role of fibronectin as a receptor for Streptococcus pyogenes. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1987;9(Suppl 4):S351–359. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.Supplement_4.S351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCullers JA, Bartmess KC. Role of neuraminidase in lethal synergism between influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2003;187:1000–1009. doi: 10.1086/368163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peltola VT, McCullers JA. Respiratory viruses predisposing to bacterial infections: role of neuraminidase. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2004;23:S87–97. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000108197.81270.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultz-Cherry S, Hinshaw VS. Influenza virus neuraminidase activates latent transforming growth factor beta. Journal of virology. 1996;70:8624–8629. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8624-8629.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean DC, Newby RF, Bourgeois S. Regulation of fibronectin biosynthesis by dexamethasone, transforming growth factor beta, and cAMP in human cell lines. The Journal of cell biology. 1988;106:2159–2170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.6.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts CJ, et al. Transforming growth factor beta stimulates the expression of fibronectin and of both subunits of the human fibronectin receptor by cultured human lung fibroblasts. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1988;263:4586–4592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ignotz RA, Heino J, Massague J. Regulation of cell adhesion receptors by transforming growth factor-beta. Regulation of vitronectin receptor and LFA-1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1989;264:389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wrana JL, Overall CM, Sodek J. Regulation of the expression of a secreted acidic protein rich in cysteine (SPARC) in human fibroblasts by transforming growth factor beta. Comparison of transcriptional and post-transcriptional control with fibronectin and type I collagen. European journal of biochemistry. 1991;197:519–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Young SL. TGF-beta regulates expression of tenascin alternative-splicing isoforms in fetal rat lung. The American journal of physiology. 1995;268:L173–180. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.2.L173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estany S, et al. Lung fibrotic tenascin-C upregulation is associated with other extracellular matrix proteins and induced by TGFbeta1. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2014;14:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li N, et al. Influenza viral neuraminidase primes bacterial coinfection through TGF-beta-mediated expression of host cell receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:238–243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414422112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Courtney HS, Dale JB, Hasty DI. Differential effects of the streptococcal fibronectin-binding protein, FBP54, on adhesion of group A streptococci to human buccal cells and HEp-2 tissue culture cells. Infection and immunity. 1996;64:2415–2419. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2415-2419.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Courtney HS, et al. Serum opacity factor is a major fibronectin-binding protein and a virulence determinant of M type 2 Streptococcus pyogenes. Molecular microbiology. 1999;32:89–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanski E, Caparon M. Protein F, a fibronectin-binding protein, is an adhesin of the group A streptococcus Streptococcus pyogenes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:6172–6176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeng A, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of a group A Streptococcus operon encoding serum opacity factor and a novel fibronectin-binding protein, SfbX. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185:1208–1217. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1208-1217.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rakonjac JV, Robbins JC, Fischetti VA. DNA sequence of the serum opacity factor of group A streptococci: identification of a fibronectin-binding repeat domain. Infection and immunity. 1995;63:622–631. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.622-631.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocha CL, Fischetti VA. Identification and characterization of a novel fibronectin-binding protein on the surface of group A streptococci. Infection and immunity. 1999;67:2720–2728. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2720-2728.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terao Y, et al. Fba, a novel fibronectin-binding protein from Streptococcus pyogenes, promotes bacterial entry into epithelial cells, and the fba gene is positively transcribed under the Mga regulator. Molecular microbiology. 2001;42:75–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terao Y, Kawabata S, Nakata M, Nakagawa I, Hamada S. Molecular characterization of a novel fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes strains isolated from toxic shock-like syndrome patients. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:47428–47435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pancholi V, Fischetti VA. A major surface protein on group A streptococci is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase with multiple binding activity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1992;176:415–426. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanski E, Jaffe J, Ozeri V. Proteins F1 and F2 of Streptococcus pyogenes. Properties of fibronectin binding. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1996;408:141–150. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0415-9_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cue D, Lam H, Cleary PP. Genetic dissection of the Streptococcus pyogenes M1 protein: regions involved in fibronectin binding and intracellular invasion. Microbial pathogenesis. 2001;31:231–242. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fisher M, et al. Shr is a broad-spectrum surface receptor that contributes to adherence and virulence in group A streptococcus. Infection and immunity. 2008;76:5006–5015. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00300-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caswell CC, Oliver-Kozup H, Han R, Lukomska E, Lukomski S. Scl1, the multifunctional adhesin of group A Streptococcus, selectively binds cellular fibronectin and laminin, and mediates pathogen internalization by human cells. FEMS microbiology letters. 2010;303:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreikemeyer B, Beckert S, Braun-Kiewnick A, Podbielski A. Group A streptococcal RofA-type global regulators exhibit a strain-specific genomic presence and regulation pattern. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2002;148:1501–1511. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-5-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodfellow AM, et al. Distribution and antigenicity of fibronectin binding proteins (SfbI and SfbII) of Streptococcus pyogenes clinical isolates from the northern territory, Australia. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2000;38:389–392. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.389-392.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kreikemeyer B, Oehmcke S, Nakata M, Hoffrogge R, Podbielski A. Streptococcus pyogenes fibronectin-binding protein F2: expression profile, binding characteristics, and impact on eukaryotic cell interactions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:15850–15859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaffe J, Natanson-Yaron S, Caparon MG, Hanski E. Protein F2, a novel fibronectin-binding protein from Streptococcus pyogenes, possesses two binding domains. Molecular microbiology. 1996;21:373–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6331356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potts JR, Campbell ID. Fibronectin structure and assembly. Current opinion in cell biology. 1994;6:648–655. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campbell ID, Spitzfaden C. Building proteins with fibronectin type III modules. Structure (London, England: 1993) 1994;2:333–337. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung CY, Zardi L, Erickson HP. Binding of tenascin-C to soluble fibronectin and matrix fibrils. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:29012–29017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.29012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vollmer T, Hinse D, Kleesiek K, Dreier J. Interactions between endocarditis-derived Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus isolates and human endothelial cells. BMC microbiology. 2010;10:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frick IM, Crossin KL, Edelman GM, Bjorck L. Protein H–a bacterial surface protein with affinity for both immunoglobulin and fibronectin type III domains. The EMBO journal. 1995;14:1674–1679. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plotkowski MC, Puchelle E, Beck G, Jacquot J, Hannoun C. Adherence of type I Streptococcus pneumoniae to tracheal epithelium of mice infected with influenza A/PR8 virus. The American review of respiratory disease. 1986;134:1040–1044. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2006;19:571–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brundage JF. Interactions between influenza and bacterial respiratory pathogens: implications for pandemic preparedness. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2006;6:303–312. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70466-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diavatopoulos DA, et al. Influenza A virus facilitates Streptococcus pneumoniae transmission and disease. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2010;24:1789–1798. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-146779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCullers JA. Preventing and treating secondary bacterial infections with antiviral agents. Antiviral therapy. 2011;16:123–135. doi: 10.3851/IMP1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCullers JA, et al. Influenza enhances susceptibility to natural acquisition of and disease due to Streptococcus pneumoniae in ferrets. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;202:1287–1295. doi: 10.1086/656333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schoggins JW, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Current opinion in virology. 2011;1:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ivan FX, et al. Differential pulmonary transcriptomic profiles in murine lungs infected with low and highly virulent influenza H3N2 viruses reveal dysregulation of TREM1 signaling, cytokines, and chemokines. Functional & integrative genomics. 2012;12:105–117. doi: 10.1007/s10142-011-0247-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Josset L, Zeng H, Kelly SM, Tumpey TM, Katze MG. Transcriptomic characterization of the novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus: specific host response and responses intermediate between avian (H5N1 and H7N7) and human (H3N2) viruses and implications for treatment options. mBio. 2014;5:e01102–01113. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01102-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeng H, et al. A(H7N9) virus results in early induction of proinflammatory cytokine responses in both human lung epithelial and endothelial cells and shows increased human adaptation compared with avian H5N1 virus. Journal of virology. 2015;89:4655–4667. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03095-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chiovaro F, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Chiquet M. Transcriptional regulation of tenascin genes. Cell adhesion & migration. 2015;9:34–47. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1008333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shi L, et al. Cross-platform comparability of microarray technology: intra-platform consistency and appropriate data analysis procedures are essential. BMC bioinformatics. 2005;6(Suppl 2):S12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-S2-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mackay IM, Arden KE, Nitsche A. Real-time PCR in virology. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:1292–1305. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.6.1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong ML, Medrano JF. Real-time PCR for mRNA quantitation. BioTechniques. 2005;39:75–85. doi: 10.2144/05391RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arya M, et al. Basic principles of real-time quantitative PCR. Expert review of molecular diagnostics. 2005;5:209–219. doi: 10.1586/14737159.5.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilhelm J, Pingoud A. Real-time polymerase chain reaction. Chembiochem: a European journal of chemical biology. 2003;4:1120–1128. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Margarit I, et al. Capturing host-pathogen interactions by protein microarrays: identification of novel streptococcal proteins binding to human fibronectin, fibrinogen, and C4BP. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2009;23:3100–3112. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Neely MN, Lyon WR, Runft DL, Caparon M. Role of RopB in growth phase expression of the SpeB cysteine protease of Streptococcus pyogenes. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185:5166–5174. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.17.5166-5174.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Granok AB, Parsonage D, Ross RP, Caparon MG. The RofA binding site in Streptococcus pyogenes is utilized in multiple transcriptional pathways. Journal of bacteriology. 2000;182:1529–1540. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.6.1529-1540.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beckert S, Kreikemeyer B, Podbielski A. Group A streptococcal rofA gene is involved in the control of several virulence genes and eukaryotic cell attachment and internalization. Infection and immunity. 2001;69:534–537. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.534-537.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sanford BA, Shelokov A, Ramsay MA. Bacterial adherence to virus-infected cells: a cell culture model of bacterial superinfection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1978;137:176–181. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McDonald JH, Dunn KW. Statistical tests for measures of colocalization in biological microscopy. Journal of microscopy. 2013;252:295–302. doi: 10.1111/jmi.12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chaussee MS, et al. Inactivated and live, attenuated influenza vaccines protect mice against influenza: Streptococcus pyogenes super-infections. Vaccine. 2011;29:3773–3781. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Herrera, A. L. et al. Binding host proteins to the M protein contributes to the mortality associated with influenza-Streptococcus pyogenes superinfections. Microbiology (Reading, England), 10.1099/mic.0.000532 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Klonoski JM, et al. Vaccination against the M protein of Streptococcus pyogenes prevents death after influenza virus: S. pyogenes super-infection. Vaccine. 2014;32:5241–5249. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008;198:962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kusubata M, et al. Spatiotemporal changes of fibronectin, tenascin-C, fibulin-1, and fibulin-2 in the skin during the development of chronic contact dermatitis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1999;113:906–912. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaarteenaho-Wiik R, et al. Tenascin immunoreactivity as a prognostic marker in usual interstitial pneumonia. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1996;154:511–518. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hisatomi K, et al. Elevated levels of tenascin-C in patients with cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 2009;48:1501–1507. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mochizuki M, Yokoyama T, Sakai T. [Tenascin expression in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia] Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai zasshi. 1994;32:752–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Paakko P, Kaarteenaho-Wiik R, Pollanen R, Soini Y. Tenascin mRNA expression at the foci of recent injury in usual interstitial pneumonia. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2000;161:967–972. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9809115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaarteenaho-Wiik R, Mertaniemi P, Sajanti E, Soini Y, Paakko P. Tenascin is increased in epithelial lining fluid in fibrotic lung disorders. Lung. 1998;176:371–380. doi: 10.1007/PL00007619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Latijnhouwers M, et al. Human epidermal keratinocytes are a source of tenascin-C during wound healing. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1997;108:776–783. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12292170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Latijnhouwers, M. A. et al. Tenascin expression during wound healing in human skin. The Journal of pathology178, 30–35, https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1096-9896(199601)178:1<30::aid-path442>3.0.co; 2–7 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Hakkinen L, Hildebrand HC, Berndt A, Kosmehl H, Larjava H. Immunolocalization of tenascin-C, alpha9 integrin subunit, and alphavbeta6 integrin during wound healing in human oral mucosa. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry: official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2000;48:985–998. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Midwood K, et al. Tenascin-C is an endogenous activator of Toll-like receptor 4 that is essential for maintaining inflammation in arthritic joint disease. Nature medicine. 2009;15:774–780. doi: 10.1038/nm.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Powell, J. D. & Waters, K. M. Influenza-Omics and the Host Response: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland)6, 10.3390/pathogens6020025 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Chakrabarti AK, et al. Host gene expression profiling in influenza A virus-infected lung epithelial (A549) cells: a comparative analysis between highly pathogenic and modified H5N1 viruses. Virology journal. 2010;7:219. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gerlach RL, Camp JV, Chu YK, Jonsson CB. Early host responses of seasonal and pandemic influenza A viruses in primary well-differentiated human lung epithelial cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e78912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee SM, et al. Systems-level comparison of host responses induced by pandemic and seasonal influenza A H1N1 viruses in primary human type I-like alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Respiratory research. 2010;11:147. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ramirez-Martinez G, et al. Seasonal and pandemic influenza H1N1 viruses induce differential expression of SOCS-1 and RIG-I genes and cytokine/chemokine production in macrophages. Cytokine. 2013;62:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang XX, et al. Gene expression profiles comparison between 2009 pandemic and seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses in A549 cells. Biomedical and environmental sciences: BES. 2010;23:259–266. doi: 10.1016/S0895-3988(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lietzen N, et al. Quantitative subcellular proteome and secretome profiling of influenza A virus-infected human primary macrophages. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1001340. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shen S, et al. Ion-Current-Based Temporal Proteomic Profiling of Influenza-A-Virus-Infected Mouse Lungs Revealed Underlying Mechanisms of Altered Integrity of the Lung Microvascular Barrier. Journal of proteome research. 2016;15:540–553. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Godehardt AW, Hammerschmidt S, Frank R, Chhatwal GS. Binding of alpha2-macroglobulin to GRAB (Protein G-related alpha2-macroglobulin-binding protein), an important virulence factor of group A streptococci, is mediated by two charged motifs in the DeltaA region. The Biochemical journal. 2004;381:877–885. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rasmussen M, Muller HP, Bjorck L. Protein GRAB of streptococcus pyogenes regulates proteolysis at the bacterial surface by binding alpha2-macroglobulin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:15336–15344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dinkla K, et al. Rheumatic fever-associated Streptococcus pyogenes isolates aggregate collagen. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;111:1905–1912. doi: 10.1172/JCI17247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kostrzynska M, Schalen C, Wadstrom T. Specific binding of collagen type IV to Streptococcus pyogenes. FEMS microbiology letters. 1989;50:229–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Watanabe R, Leser GP, Lamb RA. Influenza virus is not restricted by tetherin whereas influenza VLP production is restricted by tetherin. Virology. 2011;417:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Peltola VT, Murti KG, McCullers JA. Influenza virus neuraminidase contributes to secondary bacterial pneumonia. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2005;192:249–257. doi: 10.1086/430954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sanford BA, Davison VE, Ramsay MA. Staphylococcus aureus adherence to influenza A virus-infected and control cell cultures: evidence for multiple adhesins. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 1986;181:104–111. doi: 10.3181/00379727-181-42230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sanford BA, Ramsay MA. Bacterial adherence to the upper respiratory tract of ferrets infected with influenza A virus. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 1987;185:120–128. doi: 10.3181/00379727-185-42525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sanford BA, Smith N, Shelokov A, Ramsay MA. Adherence of group B streptococci and human erythrocytes to influenza A virus-infected MDCK cells. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 1979;160:226–232. doi: 10.3181/00379727-160-40424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ryan, P. A. & Juncosa, B. In Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations (eds Ferretti, J. J., Stevens, D. L. & Fischetti, V. A.) (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (c) The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center., 2016). [PubMed]

- 102.Zutkis AA, Anbalagan S, Chaussee MS, Dmitriev AV. Inactivation of the Rgg2 transcriptional regulator ablates the virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes. PloS one. 2014;9:e114784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Malke H, Mechold U, Gase K, Gerlach D. Inactivation of the streptokinase gene prevents Streptococcus equisimilis H46A from acquiring cell-associated plasmin activity in the presence of plasminogen. FEMS microbiology letters. 1994;116:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fogg GC, Gibson CM, Caparon MG. The identification of rofA, a positive-acting regulatory component of prtF expression: use of an m gamma delta-based shuttle mutagenesis strategy in Streptococcus pyogenes. Molecular microbiology. 1994;11:671–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Huber VC, Thomas PG, McCullers JA. A multi-valent vaccine approach that elicits broad immunity within an influenza subtype. Vaccine. 2009;27:1192–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Eyster KM. DNA Microarray Analysis of Estrogen-Responsive Genes. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2016;1366:115–129. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3127-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hall MA, et al. Intranasal immunization with multivalent group A streptococcal vaccines protects mice against intranasal challenge infections. Infection and immunity. 2004;72:2507–2512. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2507-2512.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Datasets (Raw and processed data) generated and analyzed during the current study are available from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE112215.