Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the effect of a campus-wide social norms marketing intervention on alcohol-use perceptions, consumption, and blackouts at a large, urban, public university.

Participants:

4,172 college students (1,208 freshmen, 1,159 sophomores, 953 juniors, 852 seniors) who completed surveys in Spring 2015 for the Spit for Science Study, a longitudinal study of students’ substance use and emotional health.

Methods:

Participants were emailed an online survey that queried campaign readership, perception of peer alcohol use, alcohol consumption, frequency of consumption and frequency of blackouts. Associations between variables were evaluated using path analysis.

Results:

We found that campaign readership was associated with more accurate perceptions of peer alcohol use, which, in turn, was associated with self-reported lower number of drinks per sitting and experiencing fewer blackouts.

Conclusions:

This evaluation supports the use of social norms marketing as a population-level intervention to correct alcohol use misperceptions and reduce blackouts.

Keywords: social norms, alcohol use, college students, intervention, blackout

Background

Excessive alcohol consumption and negative consequences are persistent issues on college campuses.1, 2 A large body of research documents that college students misperceive and overestimate how much alcohol their fellow students use.3–5 This is problematic because misperceptions/overestimations of peer drinking norms are an important risk factor for subsequent heavy alcohol use and harm.5

In 1996, Haines and Spears demonstrated that a social norms marketing (SNM) intervention gradually resulted in more accurate alcohol use perceptions, lower consumption and fewer negative consequences among undergraduate students on a residential campus.6 Following this landmark study, SNM has become one of the most common types of interventions for alcohol problems on campuses. The basic idea of the SNM intervention is to communicate the truth about peer norms in terms of what the majority of students actually do concerning alcohol consumption. Widely disseminated messages communicating accurate norms will gradually correct students’ misperceptions/overestimations of peer drinking norms, which in turn will reduce students’ alcohol consumption and related harm.6, 7 Many researchers have attempted to replicate Haines and Spears’ findings; some supported the effectiveness of social norms marketing, 8–11 while others did not.12–15 A recent meta-analysis indicated that overall no substantive meaningful benefits were associated with social norms interventions for prevention of alcohol misuse among college students; however, there was substantial heterogeneity across studies.16 Mixed results may be due to variation in fidelity to the intervention, level of SNM saturation, or confounding factors like competing messages from a high density of alcohol outlets. Evaluation is also complicated because many students either don’t drink alcohol or drink moderately; therefore, there is no need to alter their behavior. In addition, campus populations are always in flux, with students who are exposed to the campaign leaving college and new students enter without message exposure.

Because misperceptions are such a compelling risk factor for alcohol use and misuse, better quality evaluations of SNM interventions are still needed. Bauerle and Keller provided a logic model for implementing and evaluating a SNM intervention.17 First, the existence of misperception needs to be identified. Then a SNM campaign with fidelity to the SN approach needs to be created, pilot tested, and disseminated in such a way to reach market saturation levels. Evidence demonstrating a successful intervention would require measurement of campaign exposure, reduced misperception and then finally, demonstrate healthier behavior with reduced harm. To our knowledge, this sequence of events in SNM (Alcohol use misperception ➔ SNM campaign exposure ➔ misperception corrected ➔ decrease consumption ➔ reduced harm) has not yet been evaluated simultaneously within the same model.

Intervention: The Stall Seat Journal Social Norms Marketing Campaign

For over a decade, a SNM campaign called the Stall Seat Journal (SSJ) has been conducted at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), a large urban public university with a 32,000-student population. SSJs are printed posters that contain messages and recourses aimed at promoting student health. During the academic year, monthly SSJs were posted in over 1200 campus bathrooms in residential and common space buildings across campus. Over the past decade, process research consistently showed over 90% of the students had seen the SSJ campaign and over half were high readers which meant they read over half or all of the posters multiple times. Attempting fidelity to the SNM approach, social norms messages communicated in SSJs are based on data collected every other year (e.g., 2012, 2014) from a random sample of 5,000 VCU students who were invited by email to complete the American College Health Association’s National College Health Assessment II (ACHA-NCHA II). While health content in the posters is varied to maintain interest, alcohol-related social norms and alcohol harm reduction strategies are the primary focus of the program. Alcohol-related SSJ SNM posters used in 2014–2015 can be viewed at https://issuu.com/vcustudentaffairs/docs/2014–2015_stall_seat_journal.

Study Aim and Hypothesis

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the SSJ as a SNM intervention to correct misperceptions on peer alcohol use and reduce alcohol consumption and related consequences. It was hypothesized that higher readership of the SSJ would be associated with lower (more accurate) perceptions of peer alcohol use, which, in turn, would be associated with lower alcohol consumption (i.e., lower frequency and quantity of alcohol use). Lower alcohol consumption would, in turn, be associated with lower risk for experiencing alcohol-related blackouts. We focused on alcohol-related blackout because it is prevalent among college drinkers and is associated with negative outcomes and other drinking-related harms (e.g., sexual victimization, injury, trouble with police) above and beyond the risks associated with heavy drinking.18, 19

Methods

Data and Procedures

Data were drawn from the Spit for Science (S4S) study, 20 an on-going longitudinal study of how genetic and environmental factors affect substance use and related mental health outcomes across college years and beyond (see www.spit4science.vcu.edu). Each fall semester between 2011 and 2014, all incoming freshmen age 18 or older in the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) were invited to participate in S4S and about 70% of freshmen voluntarily enrolled in the study. Participants subsequently complete a follow-up survey in the spring of each year while at VCU and beyond graduation. The self-report surveys assess a wide range of behavioral and emotional outcomes and social environmental factors, including students’ alcohol use behaviors. In Spring 2015, the SSJ SNM campaign practitioners developed two questions assessing SSJ readership and perception of peer alcohol use and partnered with investigators of the S4S study to add them to the S4S survey. This partnership provided a great opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of SSJ as a SNM campaign in influencing VCU students’ drinking behaviors.

Participants for the current analysis included 4,172 students (1,208 freshmen, 1,159 sophomores, 953 juniors, 852 seniors) who completed the S4S Spring 2015 online survey. Age of the participants ranged from 18 to 34 years (M = 20.29, SD = 1.20). 67.2% of the participants were female. 45.5% of the participating students self-identified as European American, 20.8% were African American, 6.3% were Hispanic, 18.7% were Asian, and 8.7% were of other racial backgrounds (e.g., American Indian, Native Hawaiian, more than one race). Females were slightly over-represented in the current sample but the racial/ethnic compositions of the current sample was similar to those for the university overall (see Table 1). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Virginia Commonwealth University. All participants provided consent to participate in the study.

Table 1:

Sex and Racial/Ethnic Composition of the Current Sample and the Overall VCU Student Population

| Current Sample | VCU Spring 2015 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 32.8% | 43% |

| Female | 67.2% | 57% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 45.5% | 50% |

| Black/African American | 20.8% | 17% | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6.3% | 8% | |

| Asian | 18.7% | 13% | |

| Other | 8.7% | 12% | |

Measures

SSJ Readership

SSJ readership was assessed using a single question asking participants: “What best describes your reading of the Stall Seat Journal?” Response options were 1 (Never seen it), 2 (Seen it, don’t read it), 3 (Skimmed the headlines), 4 (Read less than half), 5 (Read more than half), 6 (Read it all), and 7 (Read it all multiple times).

Perception of Peer alcohol use

Participants responded to the one question: “How many drinks of alcohol do you think the typical VCU student had the last time they socialized?” Responses included 1 (0 drinks), 2 (1–4 drinks), 3 (5–6 drinks), 4 (7–9 drinks), and 5 (10 or more drinks).

Frequency of alcohol use

Students answered one question from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) 21 that asked how often they had a drink containing alcohol in the past year. Responses ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (4 or more times a week). Students who indicated they had never had a drink of alcohol (n = 436, 10.6% of the whole sample) were coded as never drunk in the past year.

Quantity of alcohol use

Students answered one question from the AUDIT 21 that asked how many drinks containing alcohol they had on a typical day when they were drinking. Responses ranged from 1 (1 or 2 drinks) to 5 (10 or more drinks). Students who indicated that they had never had a drink of alcohol were assigned a score of 0.

Alcohol-related blackout

Participants completed a 14-item scale adapted from ACHA-NCHA II 22 assessing their experiences of negative consequences (e.g., blacked out, physically injured, got in trouble with the police, etc.) when drinking alcohol in the past year. For this study, we focused on their report of experiences of alcohol-related blackouts. Responses were coded as 1 (yes) or 0 (No). Students who indicated that they had never had a drink of alcohol were assigned a score of 0.

Students’ alcohol use disorder symptoms were also assessed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM-5). 23 Correlation analyses indicated that participants’ number of alcohol use disorder symptoms was correlated with their frequency of alcohol use (r = .34), quantity of alcohol use (r = .35), and alcohol-related blackout (r = .39), providing evidence of convergent validity for our measures of these constructs.

Analysis

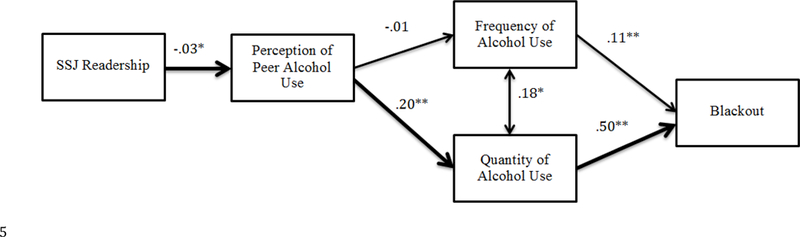

We conducted preliminary analyses to examine descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between the key study variables using SPSS version 23. To examine the associations between SSJ readership, perceptions of peer alcohol use, and college students’ alcohol use outcomes, we conducted path analysis using Mplus version 7. In the path model (see Figure 1), SSJ readership was specified as an exogenous variable predicting perception of peer alcohol use, which, in turn, was specified to be associated with students’ frequency and quantity of alcohol use. Frequency and quantity of alcohol use were specified as being correlated with each other and associated with alcohol-related blackouts. Sex, cohort, and race/ethnicity were included as covariates for the alcohol use outcomes in the model.

Figure 1:

Path Model Predicting Alcohol Use Outcomes From Stall Seat Journal Readership through Perceptions of Peer Alcohol Use. Note. Standardized path coefficients are presented. Statistically significant indirect pathways through which SSJ readership affects alcohol use outcomes are bolded. *p < .05. ** p < .01.

Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and correlations between key variables. The mean of SSJ readership was 4.85 on a seven-point scale, indicating that on average students read about half of the SSJ. Compared to females, males reported lower levels of SSJ readership, higher perception of peer alcohol use, higher frequency and quantity of alcohol use, and higher likelihood of experiencing blackout. In terms of cohort differences, seniors drank most frequently, and juniors had the highest rates of blackout (28.2%). Significant racial/ethnic differences indicated that Asian students read less of the SSJ than other racial/ethnic backgrounds. European American students drank most frequently. European American and Hispanic students also drank in higher quantity than African American and Asian students. These differences justify including sex, cohort, and race/ethnicity as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Table 2:

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between Key Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | -- | |||||||

| 2. Cohort | 2.44(3) | -- | ||||||

| 3. Ethnicity | 63.92(8)** | 25.33(24) | -- | |||||

| 4. SSJ readership | -.06** | 2.83(3) | 12.58(4)** | -- | ||||

| 5. Perception of peer alcohol use | .06** | 3.88(3)** | 10.50(4)** | -.05** | -- | |||

| 6. Frequency of alcohol use | .07** | 47.75(3)** | 66.87(4)** | .06** | .06** | -- | ||

| 7. Quantity of alcohol use | .18** | 3.07(3)* | 27.77(4)** | .05** | .20** | .64** | -- | |

| 8. Blackout | .05** | 7.91(3)* | 81.39(4)** | .05** | .04* | .42** | .42** | -- |

| Mean | -- | -- | -- | 4.85 | 2.35 | 2.59 | 1.75 | .26a |

| SD | -- | -- | -- | 1.75 | .72 | 1.08 | 1.24 | -- |

Note.

p < .01

p <.05

Pearson correlation coefficients are presented for continuous and binary variables. Chi-square statistics or F statistics from ANOVA are presented for cohort and ethnicity in relation to other variables.

indicates percentage of students who reported having experienced blackout.

Results from the path model evaluating the effect of SSJ readership on alcohol use outcomes through perceptions of peer alcohol use are presented in Figure 1. Consistent with our hypotheses, controlling for sex, cohort, and ethnicity, SSJ readership was negatively associated with perceptions of quantity of consumption, which, in turn, was positively associated with quantity of alcohol use. There was an indirect effect of SSJ readership on self-reported quantity of alcohol use via perception of peer alcohol use (SSJ ➔ perception ➔ quantity of drinking) (B = −.004, SE - .002, p = .056), suggesting that higher SSJ readership reduces students’ quantity of drinking in part by correcting their perceptions regarding alcohol use behaviors of other students. Contrary to our hypothesis, perception of quantity of consumption was not significantly associated with frequency of alcohol consumption. The indirect effect of SSJ readership on frequency of alcohol use via perception of peer alcohol use (SSJ ➔ perception ➔ frequency of drinking) was also not significant. Consistent with the hypothesis, higher frequency and quantity of alcohol use were associated with higher risk for experiencing alcohol-related blackouts. The indirect effect of SSJ readership on blackout via perception of peer alcohol use and quantity of alcohol use (SSJ ➔ perception ➔ quantity of drinking ➔ blackout) was also trending significant (B = −.002, SE = .001, p = .056), suggesting that higher SSJ readership lowers students’ risk of experiencing blackouts indirectly by correcting students’ misperceptions about peer alcohol use and reducing their quantity of drinking.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the effectiveness of a university-wide social norms intervention (the Stall Seat Journal) on alcohol-use perceptions, consumption, and blackouts at a large, urban, public university. We found that campaign readership was associated with lower perceptions of peer alcohol use, which, in turn, was associated with lower number of self-reported drinks per sitting and lower risk of experiencing alcohol-induced blackout. Our study supports the use of social norms marketing as a population-level intervention to correct alcohol use misperceptions, specifically, misperceptions regarding the number of drinks per sitting by peers. This, in turn, reduces quantity of alcohol consumption per sitting and blackouts among college students. Research on emergency room visits related to blackouts suggests that on a campus of 40,000 students, blackouts can cost approximately a half-million dollars per year.24 Even a small reduction in blackouts can result in huge financial savings and benefits to individuals.

We did not find a significant association between students’ perception of peer alcohol use and their self-reported frequency of alcohol use. One possible explanation for this is that the SSJ messages and norms tend to focus more often on quantity rather than frequency of consumption. This is due to the fact that most alcohol-related harms on campus are associated with intoxication related to high quantity of alcohol use at one time. As a result, SSJ messages over the years have focused more on normalizing 0–4 drinks per sitting or keeping blood alcohol content (BAC) below 0.08 and less on the statistic that most students drink 0–5 times per month. This finding has important implications; essentially, we saw a significant association pertaining to the norms that we messaged around in the SSJ, and no association around the norms we didn’t include in the SSJ campaign.

This analysis used a unique study population. S4S freshmen through seniors involved in the project entered in the fall of their freshmen year and no transfer students were included at least reducing some noise in the data. In analyzing the data, we found that perception of peer alcohol use was lowest among seniors. This supports the idea that misperception correction may require persistent exposure to SNM messages over time because seniors theoretically have had the longest period of exposure to these normative messages, which also supports the notion that perception shift is a dose-response relationship. It is interesting to note that both the S4S data on readership in this continuously exposed population and the random cross-sectional sample of NCHA participant’s shows very similar readership. Readership is not the same as market saturation with messages but is an important component for reaching saturation.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. First, the S4S study population was large and participants were ethnically diverse. The sample generally represents the campus population as a whole. Finally, all participants had been consistently enrolled on one campus where the intervention occurred. This was a crucial component of the evaluation process.

Limitations of this study include self-report and response bias, as well as the potential for differences between participants and non-participants, although the response rate was high. In addition, single item measures were used to assess the various constructs, which may have limited reliability and validity. However, we note that many of these questions came from well-validated scales (e.g., AUDIT). Prior research has provided support for the use of single-item measures to assess a variety of psychosocial outcomes, including alcohol-related behaviors. 25–28 Furthermore, although the study population was diverse, it was limited to one campus in one region of the country.

Conclusion

Our results indicated that the SSJ SNM print media campaign is effective for correcting misperceptions of peer alcohol use and reducing alcohol consumption and related blackouts among college students at VCU. Findings provide support for the social norms marketing approach to prevent of alcohol problems on college campus. Continued efforts to disseminate empirically driven accurate social norms messages campus-wide are important and useful to reduce misperceptions about peer drinking norms and related alcohol use problems among college students.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Spit for Science: The VCU Student Survey has been supported by Virginia Commonwealth University, P20 AA107828, R37AA011408, K02AA018755, and P50 AA022537 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. We would like to thank the VCU students for making this study a success, as well as the many VCU faculty, students, and staff who contributed to the design and implementation of the project. We are grateful to Kenneth S. Kendler for his support of this Spit for Science project. We thank the National Social Norms Center for support that funded the creation and distribution of the Stall Seat Journal Campaign.

References

- 1.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Fact Sheet on College Drinking. 2012. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFactSheet.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2017.

- 2.Turner JC, Bauerle J, Shu J. Estimated blood alcohol concentration correlation with self-reported negative consequences among college students using alcohol. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2004; 65: 741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dale TM, Prentice DA. Changing norms to change behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016; 67: 339–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkins HW. The emergence and evolution of the social norms approach to substance abuse prevention In The Social Norms Approach to Preventing School and College Age Substance Abuse: A Handbook for Educators, Counselors, and Clinicians, ed. Perkins HW, pp. 3–17. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkins HW. Misperception is reality: The “reign of error” about peer risk behavior norms among youth and young adults In The Complexity of Social Norms, Computational Social Sciences, ed.M Xenitidou B Edmonds, pp. 11–35. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haines M, Spear SF. Changing the perception of the norm: a strategy to decrease binge drinking among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 1996; 45:134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins H Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2002; Supplement (14): 164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glider P, Midyett SJ, Mills-Nova B, Johannessen K, Collins C. Challenging the collegiate rite of passage: A campus-wide social marketing media campaign to reduce binge drinking. J. Drug Educ. 2001; 31: 207–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomberg L, Schneider SK, DeJong W. Evaluation of a social norms marketing campaign to reduce high-risk drinking at the University of Mississippi. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2001; 27: 375–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2003; 64: 331–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeJong W, Schneider SK, Towvim LG, Murthpy MJ, Doer EE, Simonsen S, Mason K, Scribner, RA. A randomized trial of social norms marketing campaigns to reduce college student drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2006; 67: 868–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Werch CB, Pappas DM, Carlson JM, DiClemente CC, Chally PS, Sinder JA. Results of a social norm intervention to prevent binge drinking among first year residential college students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2000; 9: 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clapp JD, Lange JE, Russell C, Shillington A, Voas RB. A failed norms social marketing campaign. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2003; 64: 409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeJong W, Schneider SK, Towvim LG, Murthpy MJ, Doer EE, et al. A multisite randomized trial of social norms marketing campaigns to reduce college student drinking: a replication failure. Subst. Abuse. 2009; 30:127–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreira MT, Smith LA, Foxcroft D. Social norms interventions to reduce alcohol misuse in university or college students. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010; 3:CD006748. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foxcroft D, Moreira M, Almeida Santimano N, Smith L. Social norms information for alcohol misuse in university and college students. The Cochrane Library. 2015; 1:1–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller A, Bauerle JA. Using a logic model to relate the strategic to the tactical in program planning and evaluation: An illustration based on social norms interventions. Am. J of Health Promotion. 2009; 24: 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrill J, Treloar H, Fernandez A, Monnig M, Jackson K, Barnett N. Latent growth classes of alcohol-related blackouts over the first 2 years of college. Psychl Addict Behav. 2016; 30: 827–837. doi: 10.1037/adb0000214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilhite ER, Fromme K. Alcohol-induced blackouts and other negative outcomes during the transition out of college. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs. 2015; 76: 516–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dick DM, Nasim A, Edwards AC, et al. Spit for Science: Launching a longitudinal study of genetic and environmental influences on substance use and emotional health at a large US university. Front Genet. 2014; 5:47. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babor TF, De La Fuente J, Saunders J, Grant M. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College Health Association. American College Health Association – National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Data Report (Fall 2008 – 2010). Linthicum, MD. http://www.acha-ncha.org/reports_ACHA NCHAII.html. Accessed July 24, 2017.

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mundt MP, Zakletskaia LI, Prevention for college students who suffer alcohol-induced blackouts could deter high-cost emergency department visits. Health Affairs. 2012; 31: 863–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barry A, Chaney B, Stellefson M, Dodd V. Validating the ability of a single-item assessing drunkenness to detect hazardous drinking. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013; 39: 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergkvist L Appropriate use of single-item measures is here to stay. Marketing Letters. 2015; 26: 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yohannes A, Dodd M, Morris J, Webb K. Reliability and validity of a single item measure of quality of life scale for adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011; 9, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cappelleri J, Bushmakin A, McDermott A, Sadosky A, Petrie C, Martin S. Psychometric properties of a single-item scale to assess sleep quality among individuals with fibromyalgia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009; 7, 54. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]