Abstract

Background

The use of social media (SM) as a surveillance tool of global illicit drug use is limited. To address this limitation, a systematic review of literature focused on the ability of SM to better recognize illicit drug use trends was addressed.

Methods

A search was conducted in databases: PubMed, CINAHL via Ebsco, PsychINFO via Ebsco, Medline via Ebsco, ERIC, Cochrane Library, Science Direct, ABI/INFORM Complete and Communication and Mass Media Complete. Included studies were original research published in peer-reviewed journals between January 2005 and June 2015 that primarily focused on collecting data from SM platforms to track trends in illicit drug use. Excluded were studies focused on purchasing prescription drugs from illicit online pharmacies.

Results

Selected studies used a range of SM tools/applications, including message boards, Twitter and blog/forums/platform discussions. Limitations included relevance, a lack of standardized surveillance systems and a lack of efficient algorithms to isolate relevant items.

Conclusion

Illicit drug use is a worldwide problem, and the rise of global social networking sites has led to the evolution of a readily accessible surveillance tool. Systematic approaches need to be developed to efficiently extract and analyze illicit drug content from social networks to supplement effective prevention programs.

Keywords: illicit drug prevention, social media surveillance, systematic review

Introduction

Illicit drug use is a foremost global public health issue facing individuals, families and society contributing to significant morbidity among youth and adults.1 In 2014, over a quarter of a billion adults worldwide used drugs, and of these individuals 29 million are estimated to suffer from a drug use disorder and 12 million inject drugs. It is estimated that 14% of drug users are living with human immunodeficiency virus. In 2014, there were >207 000 drug-related deaths worldwide. Global regional differences exist in consumption patterns of illicit drug use; for example, recent trends indicate cocaine use is greater in western and southern European countries whereas amphetamine use is higher in Northern and Eastern Europe.1,2,3

The prevalence of illicit drug use among US young adults was 21.5% and 22% among those transitioning into young adulthood (18–25 years).4 In the USA, the most commonly used drugs are tobacco, alcohol, cannabinoids, opioids, stimulants, club drugs, dissociative drugs (Phencyclidine, Salvia divinorum, etc.), hallucinogens, inhalants and prescription medications (pain relievers).5 Cannabis is rated as the most preferred used drug globally with overall use not falling and increasing in some populations.1 Adderall is also widely used by young adults.6 Among first-time illicit drug users, ~25% use non-medical prescription drugs, 6.3% use inhalants and 2% hallucinogens.5 Among young adults, there is also a high prevalence of polydrug use: i.e. a combination of prescription drugs and illicit drugs.7 The most commonly used substance is alcohol: 42% of young adults have indulged within the past 30 days.4 Prescription drugs are readily available in doctors’ offices and home medicine cabinets and can be bought anonymously without a prescription from drug dealers and through the internet. Emerging new recreational drugs among young adults include synthetic cathinones ‘bath salts,’ synthetic cannabinoids and Salvia divinorum.6,8,9

Globally, illicit drug use is highest among 18–25 year olds,1 an age range shared by most active users of internet/social media (SM).9,10 Social networking sites (SNSs) are websites where users can share user-created content in an online community.11 Users exchange ideas, personal news and photographs while also communicating with friends, family, strangers and with others who have similar interests.12,13 Twitter and Facebook are the most popular SNSs with over 1.2 billion monthly worldwide visitors.14,15,16 Young adults most often use SNS for communicating, entertainment, event planning, and to send and receive messages, meet people and obtain information.15,16,17 SNS provide a venue for both synchronous (e.g. Message Boards, Instant Messaging and Skype) and asynchronous (e.g. MediaWiki, Padlet and Popplet) communications that are low cost, private and hidden, which can make them difficult to monitor.18–20 Young people often discuss substance use on informal networks. Therefore, SNS could be a useful tool to monitor illicit drug use.14 Today SNS provide access to data enabling epidemiologists to detect credible public health threats such as geographic trends in disease outbreaks.21,22 Syndromic (symptom) surveillance collects and evaluates health data and clinical conditions that impact the public's health. Syndromic surveillance of social network sites is now used for tracking diseases such as the flu and drug safety monitoring. Common today is the use of SNS for tracking internet pharmacy pricing and illicit drug sales.23–27 Worldwide the demographics (age, gender, socio-economic status, geographic location, etc.) of those who use illicit drugs can fluctuate dynamically over time.1,4,28 Every year new types of drugs and drug combinations entice millions of young people to use drugs.7,8 Increasingly, epidemiological surveillance of websites such as blogs or Twitter messages are used as sources to collect global health data.29,30

US government surveillance systems have evolved to monitor illicit drug use. The purpose of existing government surveillance systems is to examine population trends in use regarding types of illicit drugs, overdose, deaths, and to identify health-risk behaviors, and gaps in prevention health practices.4,6,23,28,31–35 Traditional surveillance methods in the USA have relied on mandatory and voluntary reporting by physicians, the National Poisoning Data System and laboratories of governmental agencies.23,31,32 Healthcare providers and diagnostic laboratories report the data either by legal mandate or voluntary agreement.31 Other indirect methods of surveillance include vital statistic reports from hospital emergency departments (EDs), substance abuse treatment centers, poison centers, medical examiners and police departments.33,36 Current surveillance methods for illicit drug use also include national surveys such as the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).4,34 NSDUH provides both national and state data on the use of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs. BRFSS collects data on illicit drug use, health-risk behaviors and preventive health practices. The surveys are delivered to adults through random digit dialing and administered through state health departments in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4,37 The Monitoring The Future (MTF) study (sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)) and the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS; sponsored by the CDC) survey high school students using the US mail system and provided data on the availability of illicit drugs to youths. The MTF study found that 90% of study participants indicated that it was ‘fairly easy’ or ‘very easy’ to obtain illegal substances.35 These large population-based surveys, e.g. MTF, NSDUH are conducted annually with results reported 1–2 years after collecting the data. Furthermore, these cross-sectional surveys rely on participant self-report; as a result, they lack the ability to track immediate and emerging drug trends. These may include different routes of administration (e.g. marijuana vaporizers), new substances (e.g. synthetic cathinones ‘bath salts’) or unique drug combinations intended to entice more users.38

Established in 1972 in the USA, Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) was operated by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). DAWN collected data on substance use and abuse from non-federal hospital EDs’ from 37 metropolitan states.39 DAWN was discontinued in 2011, in the last year DAWN estimated that 2.5 million illicit drug ED visits occurred.39 The Research Abuse Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance (RADARS) is a monitoring system operated by the Center for Applied Research on Substance Use and Health Disparities (ARSH) and the National Drug Control Strategy (NDCS). RADARS collects quarterly and annual data from multiple police agencies, poison centers, pharmaceutical boards and health departments in 49 US states. Data collection includes field surveys, personal interviews, telephone and mail surveys, computer-assisted interviews and focus groups, as well as operations that involve tracing hard-to-find interviewees.40 The internet makes the sale of illegal drugs very easy and provides anonymity for both dealers and users.41 In 2014, RADARS started a web monitoring program that conducts surveillance via the Web Monitoring program.40 The Web Monitoring system tracks posts on the internet, which are then organized by trained team coders to review and code the data on illicit drug use.42 Such data may also be useful as early warnings of specific illicit drug outbreaks.

Despite recent efforts toward more sophisticated web-based monitoring (e.g. RADARS), many of the current surveillance methods have limitations, including difficulties linking data, reliance on retrospective cross-sectional surveys, delayed reporting, inadequate notification system and an inefficient detection of new or emerging illicit drug use.21,31,36,43 As a result, regional illicit drug use may remain unknown to healthcare professionals until overdoses or deaths are encountered in the emergency room. Table 1 provides a summary of the US national surveillance systems.

Table 1.

Summary of US surveillance methods

| Surveillance method | Administering agency or organization | Overview |

|---|---|---|

| BRFSS | CDC | Collects data on health-related behaviors (including drug use), chronic health conditions and preventive health practices Collects data in all 50 US states, the District of Columbia and 3 US territories |

| DAWN | SAMHSA, an agency in the USA Department of HHS. Discontinued in 2011 | Monitors drug-related visits to hospital EDs and drug-related deaths in the USA |

| MTF | Funded by investigator-initiated competing research grants from the NIDA, a part of the NIH and conducted at the Survey Research Center in the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan | Studies the behaviors, attitudes and values of secondary school students, college students and young adults in the USA |

| NSDUH | SAMHSA, an agency in the USA Department of HHS | Provides national and state-level data on the use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs (including non-medical use of prescription drugs) in the USA |

| RADARS | Center for ARSH and NDCS | Measures rates of abuse, misuse and diversion of prescription drugs in the USA |

| YRBS | CDC | Monitors six types of health-risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of death and disability among American youth and adults, including alcohol and other drug use |

This information was adapted from: https://nsduhweb.rti.org/respweb/homepage.cfm, http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/; http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/, http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm, http://www.radars.org/.

NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Objective

Current knowledge of the use of SM as a surveillance tool for illicit drug use remains very limited. To address this limitation, we examined studies that focused on how social media has been used to identify illicit drug use. We conducted a review of the SNS literature using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.44 Specifically, we examined studies that collected illicit drug data from internet web forums (e.g. Tweets, Twitter, Facebook and YouTube)45–51 and evaluated each study design, methods used, results, limitations and implications for an illicit drug surveillance system. Also, we provide recommendations for promising strategies for collecting, analyzing and interpreting SNS data to monitor illicit drug use. Our effort to systematically review studies examining communications about illicit drug use that occur in public dialogs on SNS may potentially uncover trends and patterns in illicit drug use that can inform the development of intervention and prevention programs designed to reduce illicit drug use among youth and adults.

Method

Data sources

A search for articles related to SM surveillance in illicit drug use was performed using the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL via Ebsco, PsychINFO via Ebsco, Medline via Ebsco, ERIC via Ebsco, Cochrane Library, Science Direct, ABI/INFORM Complete and Communication and Mass Media Complete via Ebsco. Boolean combinations of keywords used were variations of SM (social network, Facebook, Twitter, tweet), surveillance (infoveillance, infodemiology) and substance abuse (illicit/illegal drug use, drug overdose, substance dependence).52 Manual searches of letters to the editor and technical reports were also performed. We also conducted ancestry (i.e. obtaining documents that are cited in an eligible or relevant manuscript) and descendancy approaches (i.e. obtaining documents that cite an eligible or relevant manuscript) in the studies obtained.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the review, studies had to meet the following criteria: (i) original research published in peer-reviewed journals, (ii) primary focus on collecting data on young illicit drug users from SM platforms (Twitter, Facebook and WebForums) to analyze or track trends in illicit drug use and (iii) publication between January 2005 and June 2015. We began our search in January 2005 because the use of SM has dramatically increased since that time.53 Excluded were studies with a primary focus on purchasing prescription drugs from illicit online pharmacies. Gray literature such as dissertations and theses, review papers, reports, newspaper articles, abstracts, letters to the editor and commentaries were excluded.54

Data extraction and data synthesis

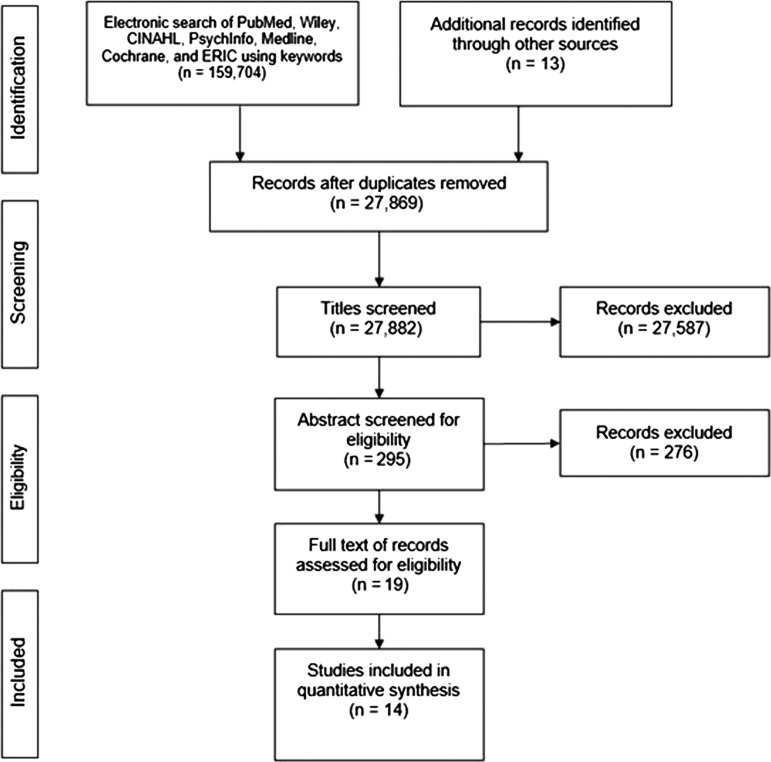

The initial search yielded 159 704 citations. After applying filters and removing duplicates, the articles were reduced to 27 869. Next, three members of the research team reviewed the papers’ titles and abstracts for relevance, duplication and the selection criteria. A total of 295 citations were considered relevant, but 276 did not meet the inclusion criteria; 19 articles were identified for full review. Each article was then independently reviewed, and five studies were removed from the pool because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The final 14 articles were subjected to full content analysis. The final articles were independently reviewed by three researchers. The researchers evaluated the studies and reached consensus on inclusion for the analysis. Interrater reliability between them for yes/no inclusion decision was 0.90, indicating strong agreement.55 Discrepancies in the selection of articles for review were discussed until consensus was reached (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A systematic review of the literature.

Results

Overview of major findings

The heterogeneity among the 14 studies examined precluded a meta-analytic integration. Instead, we provide a comprehensive summary of the 14 studies’ design, methodology, major findings and limitations.

Study design

The majority of studies were exploratory, providing descriptive analyses of SM content.56–68 Only one study used a qualitative study design,69 the others used content analysis of data from SM.

Social media platforms

Two studies analyzed web forums or message boards.61,62 Two analyzed data from YouTube.60,68 Morgan et al.60 analyzed more than one SNS, reviewing data from Myspace, YouTube and Facebook.60 Five studies analyzed data from Twitter.57,63–66 Other SNSs that were analyzed included Facebook and LiveJournal.58,67

Participants

The studies’ participants were from the general public, college students, young adults, adolescents, and Myspace and Twitter users. SM users ranged from school-aged children to young adults, with the majority reported between ages 17 and 24 years.56–60 One study reported the youngest participant was 11 years of age.69 Many participants were college students between 17 and 19 years old who followed musicians, with 43% African American.56

Illicit drugs used

A range of illicit drugs were discussed, but the most frequently reported were alcohol, marijuana, tobacco and prescription drugs. Two studies analyzed the illicit use of any prescription drug, and others focused on particular prescription drugs like opioids or Adderall.61,66

Methodology

The selected studies used a broad range of SM tools/applications, including message boards, web forums, Twitter, Facebook, Myspace and blog/forums/platform discussions. A detailed description of each study reviewed is provided in Table 1. Most of the reviewed studies followed a two-step process to track illicit drug trends.56–61,63,65–67,69 In the first step, data were collected from the SM chosen for study and prepared for analyses. In the second step, researchers used the data to analyze trends with the help of software or techniques like SPSS61 and STATA,58 Machine Learning Algorithms63,64 or Hadoop framework.67 In one study, Cameron et al.62 developed a software application called PREDOSE, which is a publicly available web forum to collect data and identify emerging trends in drug abuse. The software also helped mechanize the mining of semantic data from web forum content to enable illicit drug abuse research using SM.62

Major findings

All studies reported illicit drug surveillance from SMS sites (e.g. tweets, twitter, LiveJournal and Facebook profiles) was a positive pursuit. However, 57% of the studies (n = 8) lacked demographic filters and indicators due to privacy restrictions, presenting issues of sampling bias and limiting generalizability.56,57,61–64,67,68 Convenient small samples also limited generalizability.60,68,69 Hanson et al.65 noted their inability to observe actual behavior made it impossible to determine which public tweets corresponded with actual illicit drug use.65 Two studies did observe behavior by analyzing storytelling videos on YouTube.60,68 However, Moreno et al.59 questioned the validity of information on Myspace since the studies were examining alcohol reference, which may have been exaggerated.59

In the last decade, SM has been used to assess the motivations behind the posting of images and videos of substance use.60,67,68 Five of the 14 studies reviewed here used Twitter to track trends in substance use.57,63–66 Cavazos-Rehg et al.56 found that African Americans and Hispanics disproportionately follow @stillblazingtho.56 Cavazos-Rehg et al.57 investigated Twitter sources and found that offline and online social networks influenced health behaviors.57 Another SNS, Facebook, was found to have a potential impact on perceptions of peer alcohol use.58 A qualitative study of focus groups showed similar results; i.e. SNSs may influence adolescents’ positive attitude toward alcohol consumption.69 One of the studies suggested that the information in SM can be used by teachers and parents to track how youths interact relative to alcohol use.59

Limitations

Our review revealed several overarching limitations of illicit drug surveillance today: (i) information extracted is not always examined for relevance related to illicit drug use and is not always disseminated in the most efficient way, (ii) there is a lack of standardized system or updates and (iii) algorithms to isolate important data from streaming SM are not well developed.

Discussion

Main finding of this study

In spite of the limitations noted, the current review elicits data that supports the salient role of SNS in providing health professionals the public voice and influences that need to be addressed in programs to combat illicit drug use. The 14 studies selected investigated how SMS and, in particular SNS (e.g. Tweets, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube), have been used to identify illicit drug data acquisition. The research indicates clear implications for SM potential as a useful tool for tracking illicit drug use. If properly analyzed, these publicly available dialogs (e.g. tweets on Twitter) provide a unique and powerful way to understand substance use among young adults, who make up the largest group of users on SNS. For example, Twitter tweets extracted by Hanson et al.65 include contemporary keywords which identify risk/abusive behaviors e.g. pop, crush, steal, inhale and mimosa among others. Other publicly available tweets provide insight into substance use patterns and the influence of SM. For example, this tweet provides insight into marijuana use: ‘Those who don't understand the beauty of weed, purchasing weed, rolling and sharing of weed are outsiders and have no business in our world.’ Similarly, this tweet elucidates prescription drug use effect: ‘Adderall + Benadryl has put me in a weird awake/tired haze. Relatively certain that I'm saying things i wont [sic] remember in the morning.’56,65 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Review of studies tracking illicit drug trends through SM

| References | SM/user/drugs | Design | Method/analysis | Results | Limitations | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butler et al.61 | Message Boards that promoted discussion of psychoactive drugs/ NF/ Opioids, Prescription drugs | 6 month OCA of three message board posts. Systematic approach to analyze Internet chatter for monitoring potential abuse of opioid drugs | Harvested topics for keywords (e.g. Kadian) Searched with message board search engine. Coders determined if post was abuse-related. Data websites entered into Atlas.ti to identify unique individuals contributing | Captured 48 293 posts, 53% from unique contributors. 78.6% were abuse related and 62.0% encouraged abuse. 1813 posts (4%) contained at least one mention of OxyContin, 940 posts contained mention of Vicodin and 27 posts contained mention of Kadian | 50% of visitors to the message boards did not post. Message boards were not randomly sampled | Monitoring internet discussions may relate meaningfully to real-world diversion and abuse. Early warning system for possible trends |

| Cameron et al.62 | Web forums were cited as Site X, Site Y, Site Z/ NF/ (i) allows discussion of psychoactive drug use; (ii) contains information on illicit drug use | OCA of the use of the PREDOSE platform to analyze SM to find drug abuse practices | Created PREDOSE platform to collect data, automatically code, analyze and interpret the web data | Developed PREDOSE platform to facilitate web-based research on the illicit use of pharmaceutical opioids. Extracted 1066 502 posts of 35 974 users from three different sites | Lack of demographic indicators due to privacy restrictions from web-forum administrators. Practices in general. Geographical location of the users was not considered | PREDOSE Platform is capable of extracting entities, relationships, triples and sentiments from unstructured texts. Platform facilitates web-based research on the illicit use of pharmaceutical drugs |

| Cavazos-Rehg et al.56 | Followers of @stillblazingtho/ NF. Individuals 17–19 years old (54.05%), 42.55% African American, 12% Hispanic, 27.93% students, 21.47% musicians/ Marijuana | OCA of tweet engagement, sentiment, content and demographics of followers of a popular pro-marijuana Twitter handle | 2590 tweets from @stillblazingtho were collected for 8 months and analyzed for engagement, sentiment, content and demographics of its followers. Used crowdsourcing. Each tweet was coded by at least three coders | 82.06% of tweets were positive about marijuana, 17.64% neutral, and 0.31% negative. Of the positive, 58.72% were jokes or humorous. Of the neutral, 17.4% were inspirational or motivational quotes or messages. Most tweets were alike in their overarching positive sentiment toward marijuana use | Demographics were inferred based on usage/behavior, not reported. Only analyzed tweets from one twitter handle. Did not examine Twitter marijuana discourse in a general way | Demonstrates the use of Twitter to find and target a more appropriate audience in marijuana prevention |

| Cavazos-Rehg et al.57 | Twitter/ NF. Demographics were 82% ages 17–24, 41% male, 78% African Americans, 73% income <$20k, 62% single, 17% musicians and 15% students/Marijuana | OCA of Twitter. Examined sentiment and themes of marijuana-related chatter on Twitter sent by influential Twitter users | A total of 7 653 738 tweets were collected for 1 month in 2014 using Simply Measure—a SM analytics company. An inclusive list of marijuana-related terms from Urban Dictionary/Topsy. 7000 tweets analyzed | 77% of tweets were pro-marijuana, 5% against and 18% neutral or unknown. For pro-marijuana tweets 10 themes were identified. Most common theme, 77%, was intent to use or craving for marijuana, 17% frequent/heavy/regular use of marijuana | Tweets were from only 1 month period. Cannot verify degree to which tweets correspond with marijuana use. African American tweeters who sent pro-marijuana messages were overrepresented | Approximately 1 of every 2000 tweets was about marijuana implying that Twitter is a SM platform that facilitates chatter about marijuana. Tweets against marijuana use were comparatively low |

| Egan et al.58 | Facebook/male undergraduates between ages 18–23, mean = 19.8, 68% under 21, 62% single, 35% in a relationship/alcohol | OCA Facebook profiles from for references to alcohol use, including timing and content of alcohol references | 225 Facebook profiles were analyzed. Used codebook to find key terms in status updates and posts. Used Stata 9.0. to determine associations between alcohol, age, grade level and Facebook usage | Reference to alcohol in 85.33% of profiles. Number of references increased by year in college. Students who were of legal drinking age (21 years or older) had an average of 4.5 more references per profile than underage students (P = 0.003; confidence interval [CI] = 1.5, 7.5) | Sample was limited to one university and only limited to Facebook | Facebook has the potential to have an impact on perception of peer alcohol use, behavior related to alcohol use, Facebook could help screen users for high-risk alcohol behavior and target users with information to help with alcohol awareness |

| Hanson et al.65 | Twitter/users (n = 25), and 100 people in their social network, who had discussion about prescription drugs/ Prescription drugs | OCA of Twitter users selected who discussed topics indicative of prescription drug abuse | Twitter statuses mentioning prescription Drugs within social circles of 100 people were examined around each of these Twitter users using an algorithm | Mean number of the people in the social circle with tweets matching at one abuse category was 33.2. 3 389 771 mentions of prescription drug terms were observed | May have excluded misspellings of keywords. Can only observe discussion not behavior. May have underestimated the number of prescription drug abuse tweets | Twitter is used as a platform for discussion about prescription drug abuse within social circles. Strong correlation was found between the kinds of drugs mentioned by the index user and his or her network |

| Hanson et al.66 | Twitter/users Likely college students/ Adderall | OCA Messages pertaining the term ‘Adderall were monitored.’ Variations in volume during periods of exams on college campuses were observed | Tweets were examined for mention of side effects and other commonly abused substances. Tweets from same region were clustered together for regional comparison. ArcGIS 10 was used to create maps of rates for GPS Adderall tweeters | 213 633 tweets from 132 099 unique user accounts mentioned ‘Adderall.’ Most common substances mentioned with Adderall were alcohol (4.8%) and stimulants (4.7%). Most common side effects were sleep deprivation (5.0%) and loss of appetite (2.6%) | Not all tweets were about Adderall use. Only used public tweets. Only colleges and Universities of 10 000 or more students were examined | Geographical findings can provide practitioners with evidence necessary for prioritizing intervention resources to target priority populations. Side effects and reasoning behind the co-ingesting of drugs was commonly mentioned |

| Lange et al.68 | YouTube/NF/ Salvia Divinorum | OCA of YouTube. Examined effects of salvia use through the systematic observation of YouTube videos | Three coders conducted observations and developed an observation checklist, t-test to examine the difference in the mean duration of the effects by pipe type | Mean duration of the videos was 5.8 min with users taking an average of 1.71 hits while holding the smoke in their lungs on an average of 25.4 s | Videos were randomly selected for the study. Through videos only small amount of salvia users can be captured | Provides only some possible risk areas for Salvia Divinorum. Further research must be conducted to identify the risks more accurately |

| Moreno et al.69 | SNS Websites/ adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18/ alcohol | Examined adolescents’ interpretations of alcoholic references on SNSs. Eight focus groups were conducted | Focus groups were 45–90 min, moderated and followed semi structured format. Recorded and transcribed, coded, and analyzed | Three themes emerged: (i) References to alcohol use on SNS profiles represents real use of alcohol. (ii) References to alcohol use represent efforts to appear ‘cool.’ (iii) References to alcohol use on SNSs have risks associated with them | Convenience sampling. IRB limited how much demographic information could be gathered. Small sample size, therefore lack of generalizability | SNSs may influence adolescents’ attitudes toward alcohol use. Trends could reflect patterns that are seen in male alcohol use on college campuses, with alcohol consumption increasing throughout college |

| Moreno et al.59 | MySpace/users (n = 400) 17–20 years old representing urban, suburban and rural communities in one Washington county. 54.2% male and 70.7% white/alcohol | Theoretical content analysis of MySpace accounts of older adolescents displayed alcohol references on a social working website | Randomly selected public MySpace profiles were evaluated for alcohol references suggesting (i) explicit versus figurative alcohol use and (ii) alcohol-related motivations, associations and consequences | Of 400 profiles, 225 (56.3%) contained 341 references to alcohol. Profile owners who displayed alcohol references were mostly male (54.2%) and white (70.7%). The most commonly displayed motivation for alcohol use was peer pressure (4.7%) | Validity of information on MySpace is unknown. Display of references to alcohol use may represent alcohol use, consideration of alcohol use, boastful claims or nonsense. Only analyzed public profiles. Analyzed profiles from one website and one county | Information could be used by providers, teachers, as well as parents in considering new venues to interact with youth regarding alcohol use. Providing media literacy training to youth may help them to interpret alcohol messages received in media |

| Morgan et al.60 | MySpace, YouTube, and Facebook/Users (n = 314). Undergraduate college students. 157 men and 157 women. Ages ranged from 18 to 25/alcohol and marijuana | OCA. Examined young adults’ postings of public images and videos of themselves depicting alcohol and marijuana consumption | MySpace image search produced 14 145 results and the YouTube video search produced 26 000 results. Participants completed a series of questions assessing social networking use, alcohol and marijuana use | Images and videos showed known effects of alcohol. Alcohol consumption habits—68% reported that they currently consumed alcohol 0.33% of participants reported that they have smoked marijuana | Content analyses addressed a very small sample of such images and videos available for public access online | Need to examine SM users to assess frequency, content and motivations behind posting images and videos of substance use online. Also explore interventions that could help SM users be aware of privacy policies and the potential negative outcomes of posting publicly accessible of health-risk behaviors online |

| Myslin et al.63 | Twitter/NF/tobacco | OCA. Created a content and sentiment analysis of tobacco-related Twitter posts and built machine learning classifiers to detect relevant tobacco posts | Collected 7362 tobacco-related Twitter posts at 15-day intervals. For 6 months Classified using a triaxle scheme, Naïve Bayes Algorithms were used to identify the phrases most associated with tobacco-related tweets | Most prevalent genres were first and second hand experience and opinion. Most frequent themes were hookah, cessation and pleasure. Sentiment toward tobacco was overall more positive | Tweets were harvested from free 1% feed, not the full Twitter. Number of keywords for smoking was limited. Exclusively analyzing tobacco-related tweets using natural language processing rather than the social network aspect of Twitter | Content analysis allows for a general pulse or snapshot of tobacco-related discussion on Twitter. New insight can be gained into causes for positive and negative sentiment toward Tobacco, especially with respect to hookah and e-cigarettes |

| Prier et al.64 | Twitter/NF Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, KS, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Oregon and Pennsylvania/ tobacco | OCA of Twitter to model and discover public health topics and themes in tweets. Data were gathered from Twitter API for a 14 day period | Data were prepared by removing all non-Latin characters from messages and all the links are replaced with the term link. Used Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) unsupervised machine learning model, to generate a topic mode to analyze | Querying the comprehensive data set with these terms resulted in a subset of 1963 tweets. The subset was ~0.1% and contained topics related not only to tobacco use but also terms that are related | LDA process of removing irrelevant information is limited. Need human intervention to query terms and analysis of themes | LDA has potential to extract valuable topics from large data sets. Twitter has been identified as a potentially useful tool to better understand health-related topics such as tobacco. Twitter analysis enables public health researchers to better monitor and survey health status in order to solve community health problems. Research is needed to automate the extraction process |

| Yakushev et al.67 | LiveJournal/ NF/multiple illicit and prescription drugs. Opioids, Cannabinoid, Cocaine, Psycho stimulants | OCA of LiveJournal. Approach for mining and analysis of data from SM which is based on using MapReduce model and CLAVAIRE, distributed cloud computing platform to perform analysis | A three stage process was used. The first and second stages were data mining from SM. Data mining was performed by a crawler which is based on MapReduce model | Data were mined from SM using a crawler and stored into Hadoop cluster. The large volume of data was filtered and clustered into small data sets of useful information | Not all society groups are presented equally in SM and their main consumers are young people. Criticisms about trustworthiness and reliability of using data from SM | Several macro factors can be estimated based on official data sources but the level of interest in drugs is much easier to estimate using data from SM. But estimation of factors based on the data from SM as well as modeling with these factors is a potential future direction |

NF, No Filter for demographics and unrestricted membership; SM, Social Media; OCA, observational content analysis.

More timely and adequate findings on illicit drug use from SM could help health professionals design early and effective programs to address substance use/abuse. According to Butler et al.61, examining chatter on message boards could lead to a new surveillance model.61 Also, Cavazos-Rehg et al.57 concluded that Twitter has useful information that needs to be explored.57 Every day new SMS surveillance approaches are being developed, using different resources. For example, Chary et al.23 have proposed techniques to leverage SM to identify patterns of drug usage. Natural language processing can be used to discover statistical structures in the data. Further, Chary et al.23 suggest that machine learning can isolate items from streams of SM and discover the relationships between variables that change over time.23

What is already known on this topic

The research on SM surveillance suggests many promising directions for future investigations. In all of this research, it is vital to educate SM users about privacy policies and the potential negative consequences of posting illicit drug use behaviors online using publicly available media. First, sophisticated techniques are being developed in machine learning (triaxial classification scheme, latent Dirichlet allocation and Naïve Bayes) and cloud computing (Hadoop MapReduce Model) that allow researchers to track trends in substance use.63,64,67 The Naïve Bayes algorithm, a popular text classification technique, is relatively simple and computationally efficient.63 Second, the influences on illicit drug abuse chatter on the Internet remains largely unknown.61 Butler et al.61 identified the need for studies on Internet chatter to compare the use of pharmaceutical medications with abuse rates of these drugs found by hospital EDs and poison control centers. This approach would provide valuable information on the association between Internet chatter and levels of illicit drug use in the community.61 Facebook may be a useful tool to distribute information about alcohol prevention programs, counseling services or alcohol-free events to college students.58 Further, research could examine whether SNS can be used to reduce the adverse consequences of alcohol use.58 Finally, it would also be valuable to determine which SM platforms are used most for discussions of illicit drug use. This information could potentially lead to the development of a platform to capture discussions about drugs use asynchronously on multiple SM sites. Future research could then lead to a web-based SM monitoring system for tracking illegal drug use.

What this study adds

In order to address research limitations, this review provided a comprehensive evaluation of a number of current studies focused on SMS's role in surveillance of illicit drug use. The results of the current review indicated that there is a clear need to incorporate data mining methods (the process of finding patterns for data sets to predict outcome) into comprehensive surveillance systems to enhance communities’, law enforcements’ and healthcare agencies’ responses to drug use and emerging drugs. However, several methodological concerns are evident in the current literature. First, SM surveillance for prevention of illicit drug use is in its infancy of scientific-technological development. The current focus is primarily on collecting observational and descriptive data similar to other early efforts in health technical services such as, neuro-imaging and computed tomography scanners.70 Second, SM surveillance technology is advancing faster than current knowledge as relates to the relationship of human motivation and SM. This is not unexpected in light of the lack of training and experience health service professionals have with SM. Third, SM can potentially be a useful tool for tracking data relevant to epidemiological and clinical utility. This is a limited view since tracking is just one factor in its role of contributing to health service intervention and prevention in particularly as relates to illicit drug use. In addition, the internet is an important source of information, which can be gathered from many WorldWide Web forums (Twitter, Facebook and forums). Potential biases exist when relying on a particular social platform selected for surveillance. Specifically, users of the platform may not be representative of the population and questions will always exist regarding the intent, identity or accuracy of self-representation of the contributors to internet discussion on SM. Therefore, a need exists to identify which social platforms are used most by the public to share their illicit drug use. Also, the development of a dictionary of common words used by illicit drug users would facilitate the surveillance of internet platforms (Twitter, Facebook and forums).

Ethical issues in the surveillance of illicit drug use are a long-standing concern. In light of current innovative technological advances as seen on the internet (websites or SM) ethical issues about surveillance of illicit drug in SM is a new challenge for all professional health service practices. The benefits for health professionals are evident since the data retrieved could serve as public health warning and the need for interventions. There are many limitations related to the validity and reliability of information retrieved from surveillance systems. For example, several questions arise regarding the data extracted, (i) who retrieved and interpreted the information e.g. professional, epidemiologist, (ii) was the information extracted from an official or ‘public’ unofficial source (iii) with the high volume and real-time surveillance, the data may be obsolete by the time it reaches the health professionals and (iv) extraction methods are not well developed relative current standardized procedures.

The use of SM for illicit drug surveillance is a new concept. Although social networks are in public domain, there are also ethical issues related to privacy protection when using these sites for public health surveillance. Privacy laws can prevent free access to illicit drug use data, which would prevent formal analysis of data by structured institutions e.g. government agencies. Legal additions/revisions of privacy laws are required to address the ethical dimension of the surveillance method by SM. A cooperative effort by professional health services organization, governmental agencies such as SAMHSA and the Department of HHS, community health agencies, concerned citizen groups and ethical, legal and technological expertise is required to address these issues.

Limitations of this study

Findings in the current literature should be considered in the context of some limitations. The studies examined here were carried out only with publicly available data, which may not include some crucial data like geographical location, post, comment, tweet and other personal information like age, sex and race. This may limit the accuracy of the results obtained. Another limitation is that when a keyword-based approach was used to find the data, misspelled words were not considered, nor were synonyms for the keyword.60,61,65,66,68 Restricting the search to a few drugs without considering the most prevalent drugs is a major drawback.60,63,68 Another issue found was that when a selected model is applied to a small data set, there is always the risk of the model to over fit. For example, Butler et al.61 failed to address this critical issue, and, therefore, their results may be inconsistent with reality.

Conclusion

The rise of the internet and SNS has led to the evolution of readily accessible information on a global scale regarding illicit drug use. Current illicit drug surveillance methods have significant limitations including being slow and costly, unable to detect new or emerging illicit drugs trends and often dependent on retrospective data.4,28,34,37,71 The development and worldwide use of SM, particularly by young adults, suggests that people may prefer informal networks such as SM and message boards for discussing their drug use.14–17 Thus, worldwide social network data can identify patterns of emerging drug use, and data mining tools can complement current surveillance methods.23 National and International health and government organizations including the World Health Organization need to focus on the potential impact of SM for prevention and treatment of illicit drug use. Training of health service providers on the role of SM and its evolving technology should be a primary focus for national and global international organizations.

A vast trove of information with clear real-time updates and identification of new and emerging drugs seems to be untapped. Therefore, worldwide systematic approaches need to be developed to efficiently extract and analyze content from social networks. This important work would best be accomplished by a global multi-disciplinary collaboration to include health service providers, computer scientists, mathematicians, internet technical specialists, government/community services and public citizens.

Conflicts of interest

DMK declares that she has no conflict of interest. BB declares that he has no conflict of interest. MJL declares that she has no conflict of interest. BD declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article contains no studies performed by the authors using human participants or animals.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grant 1R21 AA023975-01.

References

- 1. World Health Organization Global Health Observatory (GDO) data 2016. http://www.who.int/gho/database/en/. (16 March 2016, date last accessed).

- 2. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime World Drug Report 2016. (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.16.XI.7).

- 3. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. European Drug Report 2016: Trends and Development. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings.http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresults2012/NSDUHresults2012.pdf. (12 March 2016, date last accessed).

- 5. National Institute on Drug Abuse Prescription Drugs and Cold Medicines.2015. http://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/prescription-drugs-cold-medicines. (9 March 2016, date last accessed).

- 6. National Institute on Drug Abuse DrugFacts:Marijuana 2015. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana. (12 March 2016, date last accessed).

- 7. Kelly BC, Wells BE, Pawson M et al. . Combinations of prescription drug misuse and illicit drugs among young adults. Addict Behav 2014;39(5):941–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Apa-Hall P, Schwartz-Bloom R, McConnell E. The current state of teenage drug abuse: trend toward prescription drugs. J School Nurs (Allen Press Publishing Services Inc.) 2008:S1–14 1. Available from: CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. [serial online]. June1 2. [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Institute of Drug Abuse Prescription Drug Abuse 2014. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/prescription-drugs/director. (21 April 2016, date last accessed).

- 10. National Drug Intelligence Center Information Bulletin: Drugs, Youth and the Internet http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs2/2161/index.htm#Outlook. (22 April 2016, date last accessed).

- 11. Kim W, Jeong O-R, Lee S-W. On social web sites. Inf Syst 2010;35(2):215–36. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cain J. Online social networking issues within academia and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ 2008;72(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cain J, Policastri A. Using Facebook as an informal learning environment. Am J Pharm Educ 2011;75(10):207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Han S, Min J, Lee H. Antecedents of social presence and gratification of social connection needs in SNS: a study of Twitter users and their mobile and non-mobile usage. Int J Inf Manage 2015;35(4):459–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quan-Haase A, Young AL. Uses and gratifications of social media: a comparison of Facebook and instant messaging. B Sci Technol Soc 2010;30(5):350–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ku Y-C, Chu T-H, Tseng C-H. Gratifications for using CMC technologies: a comparison among SNS, IM, and e-mail. Comput Hum Behav 2013;29(1):226–34. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pempek TA, Yermolayeva YA, Calvert SL. College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. J Appl Dev Psychol 2009;30(3):227–38. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stefanone MA, Lackaff D, Rosen D. Contingencies of self-worth and social-networking-site behavior. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2011;14(1–2):41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lakon CM, Valente TW. Social integration in friendship networks: the synergy of network structure and peer influence in relation to cigarette smoking among high risk adolescents. Soc Sci Med 2012;74(9):1407–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Best P, Manktelow R, Taylor B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: a systematic narrative review. Child Youth Serv Rev 2014;41:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Velasco E, Agheneza T, Denecke K et al. . Social media and internet-based data in global systems for public health surveillance: a systematic review. Milbank Q 2014;92(1):7–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karampelas V, Mantas J, Pallikarakis N et al. . Proposal for the development of an epidemic prediction and monitoring system based on information collected via online social networks. Stud Health Technol Inform 2014;202:318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chary M, Genes N, McKenzie A et al. . Leveraging social networks for toxicovigilance. J Med Toxicol 2013;9(2):184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naun CA, Olsen CS, Dean JM et al. . Can poison control data be used for pharmaceutical poisoning surveillance. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18(3):225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eysenbach G. Infodemiology and infoveillance: framework for an emerging set of public health informatics methods to analyze search, communication and publication behavior on the internet. J Med Internet Res 2009;11(1):e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Freifeld CC, Brownstein JS, Menone CM et al. . Digital drug safety surveillance: monitoring pharmaceutical products in Twitter. Drug Saf 2014;37(5):343–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dasgupta N, Freifeld C, Brownstein JS et al. . Crowdsourcing black market prices for prescription opioids. J Med Internet Res 2013;15(8):e178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. National Center for Health Statistics Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus14.pdf. (15 February 2016, date last accesed).

- 29. Grajales FJ 3rd, Sheps S, Ho K et al. . Social media: A review and tutorial of applications in medicine and health care. J Med Internet 2014;16(2):e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bernardo TM, Rajic A, Young I et al. . Scoping review on search queries and social media for disease surveillance: a chronology of innovation. J Med Internet Res 2013;15(7):e147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International Data Collection and Management https://www.rti.org/service-capability/surveys-and-data-collection. (21 April 2016, date last accessed).

- 32. Armstrong TM, Davies MS, Kitching G et al. . Comparative drug dose and drug combinations in patients that present to hospital due to self-poisoning. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2012;111(5):356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Institute of Drug Abuse DrugFacts: Drug-related Hospital Emergency Room visits 2011. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/drug-related-hospital-emergency-room-visits. (21 April 2016, date last accessed).

- 34. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Behaviorial Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/ 2015. (20 April 2016, date last accessed).

- 35. University of Michigan Monitoring the Future http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/ 2015. (21 April 2016, date last accessed).

- 36. Friedman LS. Real-time surveillance of illicit drug overdoses using poison center data. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47(6):573–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S et al. . Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system (YRBSS)--2013. MMWR Recomm Rep 2013;62(RR-1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mars SG, Fessel JN, Bourgois P et al. . Heroin-related overdose: the unexplored influences of markets, marketing and source-types in the United States. Soc Sci Med 2015;140:44–53. 10p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Emergency Department Data Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN). http://www.samhsa.gov/data/emergency-department-data-dawn. (25 April 2016, date last accessed). [PubMed]

- 40. Researched Abuse Diversion, and Addicted-Related Surveillance (RADARS) System http://www.radars.org. (12 April 2016, date last accessed).

- 41. Barratt MJ, Ferris JA, Winstock AR. Use of Silk Road, the online drug marketplace, in the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States. Addiction 2014;109(5):774–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. West NA, Severtson SG, Green JL et al. . Trends in abuse and misuse of prescription opioids among older adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;149:117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Milinovich GJ, Williams GM, Clements AC et al. . Internet-based surveillance systems for monitoring emerging infectious diseases. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14(2):160–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cook SH, Bauermeister JA, Gordon-Messer D et al. . Online network influences on emerging adults’ alcohol and drug use. J Youth Adolesc 2013;42(11):1674–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fujimoto K, Valente TW. Social network influences on adolescent substance use: disentangling structural equivalence from cohesion. Soc Sci Med 2012;74(12):1952–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huang GC, Soto D, Fujimoto K et al. . The interplay of friendship networks and social networking sites: Longitudinal analysis of selection and influence effects on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Am J Public Health 2014;104(8):e51–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Soussan C, Kjellgren A. Harm reduction and knowledge exchange-a qualitative analysis of drug-related Internet discussion forums. Harm Reduct J 2014;11:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oh HJ, Ozkaya E, LaRose R. How does online social networking enhance life satisfaction? The relationships among online supportive interaction, affect, perceived social support, sense of community, and life satisfaction. Comput Hum Behav 2014;30:69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Smith T, Lambert R. A systematic review investigating the use of Twitter and Facebook in university-based healthcare education. Health Educ J 2014;114(5):347–66. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bohnert AS, Bradshaw CP, Latkin CA. A social network perspective on heroin and cocaine use among adults: evidence of bidirectional influences. Addiction 2009;104(7):1210–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Goodwin GP, Johnson-Laird PN. The acquisition of Boolean concepts. Trends Cogn Sci 2013;17(3):128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Loader BD, Dutton WH. A decade in internet time. Inform Comm Soc 2012;15(5):609–15. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Alberani V, De Castro Pietrangeli P, Mazza AM. The use of grey literature in health sciences: a preliminary survey. Bull Med Libr Assoc 1990;78(4):358–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss M, Grucza R et al. . Characterizing the followers and tweets of a marijuana-focused Twitter handle. J Med Internet Res 2014;16(6):e157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss M, Fisher SL et al. . Twitter chatter about marijuana. J Adolesc Health 2015;56(2):139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Egan KG, Moreno MA. Alcohol references on undergraduate males’ Facebook profiles. Am J Mens Health 2011;5(5):413–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A et al. . A content analysis of displayed alcohol references on a social networking web site. J Adolesc Health 2010;47(2):168–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morgan EM, Snelson C, Elison-Bowers P. Image and video disclosure of substance use on social media websites. Comput Hum Behav 2010;26(6):1405–11. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Butler SF, Venuti SW, Benoit C et al. . Internet surveillance: content analysis and monitoring of product-specific internet prescription opioid abuse-related postings. Clin J Pain 2007;23(7):619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cameron D, Smith GA, Daniulaityte R et al. . PREDOSE: a semantic web platform for drug abuse epidemiology using social media. J Biomed Inform 2013;46(6):985–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Myslin M, Zhu SH, Chapman W et al. . Using Twitter to examine smoking behavior and perceptions of emerging tobacco products. J Med Internet Res 2013;15(8):e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Prier KW, Smith MS, Giraud-Carrier C et al. . Identifying health-related topics on Twitter: an exploration of tobacco-related weets as a test topic. Lect Notes Comp Sc 2011;6589:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hanson CL, Cannon B, Burton S et al. . An exploration of social circles and prescription drug abuse through Twitter. J Med Internet Res 2013;15(9):e189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hanson CL, Burton SH, Giraud-Carrier C et al. . Tweaking and tweeting: exploring Twitter for nonmedical use of a psychostimulant drug (Adderall) among college students. J Med Internet Res 2013;15(4):e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yakushev A, Mityagin S. Social networks mining for analysis and modeling drugs usage. Procedia Comput Sci 2014;29:2462–71. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lange JE, Daniel J, Homer K et al. . Salvia divinorum: effects and use among YouTube users. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010;108(1–2):138–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A et al. . Real use or ‘real cool’: adolescents speak out about displayed alcohol references on social networking websites. J Adolesc Health 2009;45(4):420–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Loudon I (ed).. Western Medicine: An Illustrated History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Shillington AM, Woodruff SI, Clapp JD et al. . Self-reported age of onset and telescoping for cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana across eight years of the national longitudinal survey of youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse 2012;21(4):333–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]