SUMMARY

Aim:

Tumor hypoxia and presence of tumor stem cells are related to therapeutic resistance and tumorigenicity in glioblastomas. The aim of the present study was therefore to identify microRNAs deregulated in acute hypoxia and to identify possible associated changes in stem cell markers.

Materials & methods:

Glioblastoma spheroid cultures were grown in either 2 or 21% oxygen. Subsequently, miRNA profiling was performed and expression of ten stem cell markers was examined.

Results:

MiRNA-210 was significantly upregulated in hypoxia in patient-derived spheroids. The stem cell markers displayed a complex regulatory pattern.

Conclusion:

MiRNA-210 appears to be upregulated in hypoxia in immature glioblastoma cells. This miRNA may represent a therapeutic target although it is not clear from the results whether this miRNA may be related to specific cancer stem cell functions.

KEYWORDS : cancer stem cell, glioblastoma, hypoxia, microRNA, profiling, spheroids

Therapeutic resistance remains an essential challenge in the development of new therapeutic strategies against glioblastomas. Both presences of tumor hypoxia [1] and tumor stem cells [2–7] are related to this problem. Additionally, microRNAs (miRNAs) have recently attracted increased attention since novel research has revealed a link between miRNAs and chemoresistance [8]. miRNAs are small, noncoding single-stranded RNA molecules of approximately 22 nucleotides in lengths. They serve as post-transcriptional gene regulators by affecting either the translation or the stability of mRNAs [9]. Knowledge of the interplay between miRNAs and tumor stem cell biology is limited, especially under hypoxia. However, it is highly relevant since both hypoxia [1], miRNAs [8], and tumor stem cells [2–7] appear to be involved in the therapeutic resistance of glioblastomas.

In 2007 it was demonstrated that hypoxia influences the miRNA expression of cells in a variety of cancer types [10]. Since then several studies have been performed within this field [11–14] and through these, miR-210 has emerged as the predominant miRNA regulated by hypoxia [10,13,15]. Yet, studies of hypoxia-regulated miRNAs in glioblastomas are limited. As demonstrated in other cancers, a study from 2011 describes a hypoxia-induced upregulation of, among others, miR-210 in the hypermutated glioma cell line U87 [16]. This has recently been confirmed in two other studies [17,18]. Based on the previous studies, we hypothesized that glioma stem cell-containing spheroid cultures express high levels of unique miRNAs when cultured under hypoxic conditions similar to the hypoxic conditions seen in glioblastomas. In particular, we expected a hypoxia-induced upregulation of miR-210.

Recent studies have revealed that long-term hypoxia may reprogram nonstem cells toward a stem cell-like phenotype in addition to promoting the self-renewal and maintenance of this undifferentiated phenotype [19–21]. On this basis, we hypothesized that stem cell markers were upregulated already by acute hypoxia along with specific deregulation of miRNAs.

Among the most prominent known mediators of the cellular response to hypoxia are the hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs): HIF1α and HIF2α. Regarding stem cells, especially the latter seems to be of great importance [19,21]. It requires prolonged hypoxia to be induced and consequently mediates the late or chronic hypoxic response. HIF1α, on the other hand, is induced shortly after exposure to hypoxia and thus mediates the acute hypoxic response [19,21–23]. Having a high HIF1α level in glioma spheroids in acute hypoxia in the present study, this model was used to study the acute regulation of miRNAs and stem cell markers.

In summary, the overall aim of this study was to identify deregulated miRNAs in acute hypoxia and to identify possible associated early changes in the expression of stem cell markers. The results showed a hypoxia-induced upregulation of miR-210, but no systematic alterations in the expression of stem cell markers was found.

Materials & methods

• Cell lines

In this study the cell lines U87, T98G, T78, T86, and T87 were used. U87 and T98G are commercially available (ECACC, UK) and will be referred to as CCL cultures. T78, T86, and T87 are glioblastoma short-term cultures with tumor stem cell properties established in serum-free medium in our laboratory as previously described [24]. These cultures showed repeated spheroid formation in vitro in serum-free medium, differentiation into cells expressing glial and neuronal markers in serum-containing medium as well as formation of infiltrative tumors in NOD-SCID mice upon orthotopic implantation. In the following they will be referred to as GSS cultures. These cultures were established from tissue obtained after informed consent from patients operated at the Department of Neurosurgery at Odense University Hospital.

• Cell culturing

Cells were cultured in a serum-free medium according to a previously described protocol [20,25]. Spheroids were cultured at 36°C humidified air containing 5% CO2 and 95% atmospheric air. When the diameter reached 100–200 µm, they were either placed for 24 h at hypoxia (36°C humidified air containing 5% CO2, 2% O2 and 93% N2) or grown for another 24 h under normoxic conditions as described above.

• Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed using a Dako Autostainer Universal Staining System (Dako, Denmark). All reagents were obtained from Dako A/S, Denmark, and used as described by manufacturer's protocol. For more details see previous publications [20,26–27]. Applied antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 1 [28–39]. Omission of primary antibodies served as negative controls as well as controls for nonspecific staining induced by the detection systems alone. The reactions were evaluated by measuring the staining intensities of the spheroids using the VIS software (Visiopharm).

• miRNA profiling

miRNA profiling was performed by microarrays at the Human Microarray Centre, Odense University Hospital using their spotting technology [40,41] and an Exiqon LNA probe set recognizing 1294 human miRNAs (www.mirbase.org). Each miRNA was spotted in triplicate. RNA was purified from RNAlater using Qiagen RNeasy columns according to manufacturer's protocol.

Data analysis was performed using Genepix software for feature extraction. Data were normalized using loess for within slide normalization and quantile method for between slide normalization. This was done using limma software package in R environment (http://www.bioconductor.org). A variance filter was applied to remove 50% of the miRNA genes with lowest variance and differentially expressed miRNA was identified by Significance analysis of Microarray using MeV (Multi-Experiment Viewer (www.tm4.org/mev).

• qRT-PCR

miRNA purification was carried out using the mirVanaTM miRNA Isolation Kit from Ambion, USA. The assay was carried out according to manufacturer's protocol for RNA isolation. The kit provided all employed solutions except phenol/chloroform and 100% ethanol.

qRT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicates with RNU6B serving as endogenous control. cDNA synthesis was carried out using the TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Data were analyzed using SDS 2.1 software (Applied Biosystems, USA).

Results

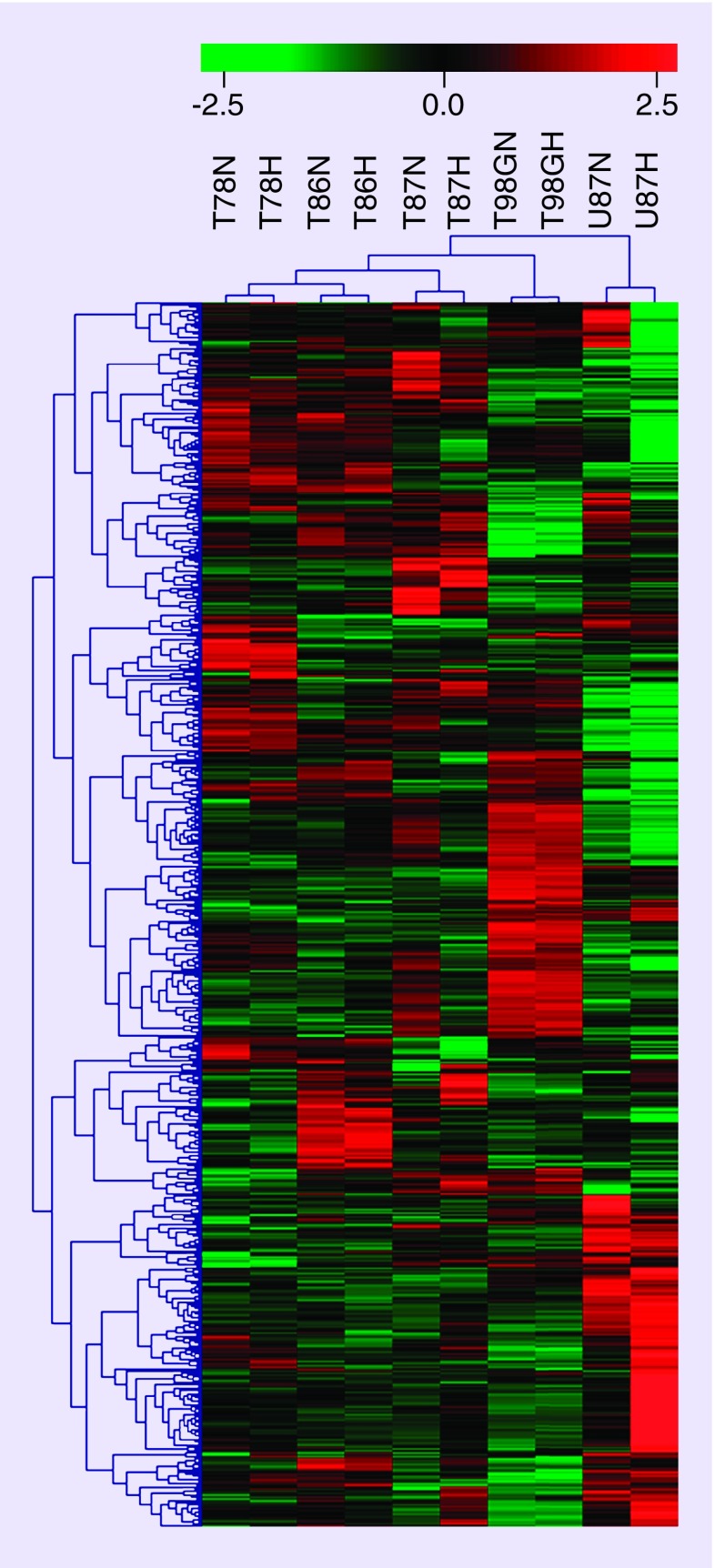

• MiRNA profiling revealed a strong variation in expression of miRNAs between cell lines

As the heatmap (Figure 1) illustrates, variations between cell lines exceed variations between hypoxic and normoxic samples within each cell line. It also illustrates that the miRNA profiles of the three GSS cultures (T78, T86, and T87) are more similar than either of them is to the profiles of the two CCL cultures (T98G and U87). Moreover, T98G and U87 have different miRNA profiles when compared with each other.

Figure 1. . miRNA profiling, recognizing 1294 human miRNAs, revealed different profiles for the individual cell lines by hierarchical cluster analysis.

The five cell lines are listed in the top. N and H denote normoxia and hypoxia, respectively. Each horizontal row represents a different miRNA. Red and green scale represents high and low expression, respectively. All microarray data forming the basis of this heatmap are available in the NCBI GEOdatabase.

For color images please see online at http://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/full/10.2217/cns.14.48

In particular, six miRNAs (miR-9, miR-27a, miR-27b, SNORD14B, miR-625*, and miR-93) were found to have a significantly different expression in CCL cultures compared with GSS cultures (Table 1). Regardless of oxygen conditions, miR-9 showed a higher expression in GSS cultures compared with CCL cultures. Also miR-93 had a higher expression in GSS cultures, though only under hypoxic conditions. MiR-27a, miR-27b, SNORD14B and miR-625* were all found to be significantly higher expressed in CCL cultures compared with GSS cultures. The higher expression of miR-27b was observed regardless of oxygen conditions, while the higher expression of miR-27a and SNORD14B were only detected in normoxia. The higher expression of miR-625* were, on the other hand, only significant in hypoxia.

Table 1. . Comparison of miRNA expression in CCL (T98G and U87) and GSS cultures (T78, T86 and T87).

| miRNA | FC, normoxia | FC, hypoxia |

|---|---|---|

| miR-9 | 0.097** | 0.094** |

| miR-27a | 5.29** | 8.91 |

| miR-27b | 3.35** | 4.98** |

| SNORD14B | 2.40** | 1.88 |

| miR-625* | 1.55 | 1.91** |

| miR-93 | 0.22 | 0.28** |

**Denotes significant change. FC > 1: highest expression in CCL cultures compared with GSS cultures; FC < 1: highest expression in GSS cultures. miR-625* is complementary to miR-625.

FC: Fold change; SNORD14B: Small nucleolar RNA C/D Box 14B.

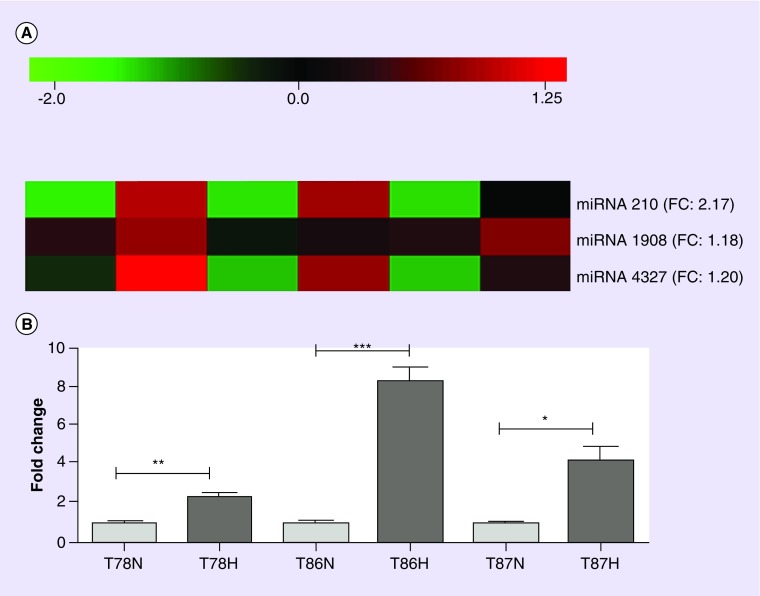

• A hypoxia-induced upregulation of miR-210 was identified in GSS cultures

MiRNA profiling also identified a few hypoxia-induced alterations. By performing an unpaired significance analysis of Microarray test including only GSS cultures, miR-210, miR-1908, and miR-4327 were found to be significantly upregulated in hypoxia compared with normoxia (Figure 2A). For miR-210 only, the fold change was above 2. The hypoxia-induced upregulation of miR-210 was subsequently confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 2B). The biggest upregulation was found in T86 with a fold change at 8.12 (p < 0.001). In T87 the fold change was 4.17 (p < 0.05), and in T78 it was 2.38 (p < 0.01).

Figure 2. . Microarray-based comparison of hypoxic versus normoxic spheroid cultures.

(A) The heatmap illustrates three miRNAs (miR210, miR1908, and miR4327) being significantly higher expressed in hypoxia compared with normoxia in the glioma stem cell-containing spheroids cultures T78, T86, and T87. (B) miR-210 was upregulated with a fold change over 2 and was therefore validated by a TaqMan® qRT-PCR assay, which also showed a significant upregulation for all three cell lines. The assay was performed in triplicate with RNU6B as an internal control. Data are shown as means + SEM; n = 2–3, and statistical significance *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 was investigated using an unpaired students t-test. N and H denote normoxia and hypoxia, respectively. Red and green scale in the heatmap represents high and low expression, respectively.

For color images please see online at http://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/full/10.2217/cns.14.48

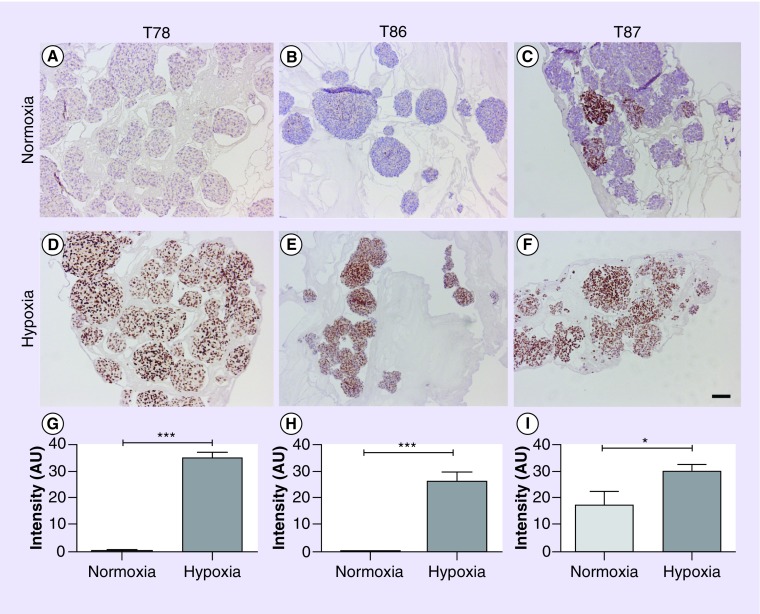

• HIF1α was upregulated after 24 h of hypoxia

Expression of HIF1α and HIF2α was investigated by immunohistochemistry. It showed a hypoxia-induced HIF1α upregulation. The transcription factor was significantly upregulated in T78, T86, and U87 (all with p < 0.001) and T87 (p < 0.05) (Figure 3). In T98G it was upregulated, but without significance (data not shown). Only T87 did express HIF2α at a detectable level (data not shown). However, the hypoxia-induced upregulation was not significant.

Figure 3. . Expression of HIF1α and HIF2α was investigated by immunohistochemistry.

A significant hypoxia-induced upregulation of HIF1α was identified by immunohistochemical staining of the glioma stem cell-containing spheroid cultures T78 (A, D & G), T86 (B, E & H) and T87 (C, F & I). (A–C) Spheroids were grown in normoxia or (D–F) hypoxia for 24h. Scale bar 100 µm. (G–I) Data are shown as means + SEM; n = 30. Statistical significance *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 was investigated using a t-test.

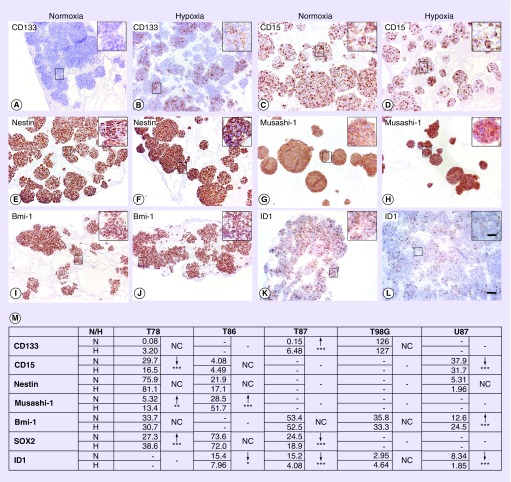

• No systematic hypoxia-induced alterations in the expression of stem cell markers was identified

The expression of 10 stem cell markers (CD133, CD15, nestin, Musashi-1, Bmi-1, Oct-4, SOX2, ID1, ALDH1, and Podoplanin) was investigated by immunohistochemical staining. In general, the expression patterns varied widely between cell lines, with no systematic acute hypoxia-induced upregulation of stem cell markers (Figure 4). CD133 was significantly upregulated in T87 (p < 0.001), while its expression was stable regardless of oxygen tension in T86, T98G, and U87 (Figure 4A & B). In T78 and U87 a significantly hypoxia-induced downregulation of CD15 was seen (p < 0.001) (Figure 4C & D). No clear pattern was found for nestin (Figure 4E & F). Musashi-1 was only expressed at a detectable level in T78 and T86, though with a significant upregulation in response to hypoxia (T78 with p < 0.01 and T86 with p < 0.001) (Figure 4G & H). Bmi-1 was significantly upregulated by hypoxia in U87 (p < 0.001) but in T78, T87, and T98G it showed a stable expression regardless of oxygen supply (Figure 4I & J). The expression of SOX2 was generally higher in GSS cultures compared with CCL cultures, but no clear tendency in hypoxia was seen (data not shown). Finally, ID1 showed a tendency of hypoxia-induced downregulation (U87 and T87 with p < 0.001 and T86 with p < 0.05) (Figure 4K & L). Oct-4, ALDH1 and Podoplanin are left out from the table since they were not present in a detectable level in any cell line.

Figure 4. . Hypoxia-induced alterations in the immunohistochemical expression of the cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD15, nestin, Musashi-1, Bmi-1, and ID1 in the glioma stem cell-containing spheroid cultures.

CD133 was significantly upregulated in T87 (A, B) while CD15 was significantly downregulated in T78 (C, D). No significant alterations were seen for nestin (E, F). Musashi-1 was significantly upregulated in T86 (G, H). In GSS cultures no hypoxia-induced alteration was seen for Bmi-1 (I, J), while ID1 was significantly downregulated in T87 (K, L). Scale bar 100 µm; 30 µm in inserts. Quantitative measurements and statistical comparison of hypoxia-induced alterations (M). Arrows indicate up- and down-regulation, while asterisks give the statistical significance *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 investigated using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. Lines means that the given marker wasn’t detectable and NC means that no significant hypoxia-induced change was observed. The values are given in arbitrary units.

Discussion

In the present study hypoxic glioma spheroids with a high expression of HIF1α showed upregulation of miR-210. Using an immunohistochemical panel of 10 stem cell markers we found no systematic upregulation although the levels of individual markers were changed in hypoxia.

The hypoxia-induced upregulation of HIF1α after 24 h of hypoxia is in line with previous findings. HIF1α has previously been nominated as the main mediator of the acute hypoxic response being induced after only 2 h and still being present after at least 48 h of hypoxia [23]. Regarding HIF2α, only T87 expressed HIF2α at a detectable level but there was no significant hypoxia-induced upregulation after 24 h. This low or absent expression is again in line with previous observations showing that HIF2α is induced by prolonged hypoxia and consequently mediates the late or chronic response to hypoxia [19,21–22]. Based on these important observations we therefore hypothesized 24 h of hypoxia exposure of our spheroids to be a suitable three-dimensional model to study the regulation of miRNAs and stem cell markers in acute hypoxia.

MiRNA profiling revealed a hypoxia-induced increase in the expression of miR-210 in GSS cultures, which was subsequently confirmed in a TaqMan qRT-PCR assay. This finding verifies a central hypothesis of our study and to our knowledge we are the first to report a hypoxia-induced increase in the expression of miR-210 in GSS-cultures. The qRT-PCR assay found notable variations in the level of upregulation between the three cultures. In T86 the upregulation was most pronounced with a fold change at 8.04 while the fold changes in T87 and T78 was lower: 4.03 and 2.11, respectively. This demonstrates that differences in the response to hypoxia exist among glioblastomas and suggests that therapies designed to exploit tumor hypoxia may have varying effects in tumors with different hypoxic stress responses. MiR-210 has previously been reported to be upregulated in other hypoxic tumors and cell lines and is described as the predominant miRNA regulated by hypoxia [10,13,15–16]. Mainly, studies have been carried out in colon and breast cancer cells [10–12], but also in neuroblastoma cell lines [14] and nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells lines [13], miR-210 has been reported to be upregulated in response to hypoxia. Most importantly, miR-210 is involved in angiogenesis, proliferation, and differentiation [42] and additionally, its upregulation has been suggested to link hypoxia to immune escape [43]. However, in order to clarify the exact role of miR-210 in glioblastoma malignancy as well as its target genes, functional experiments including different cell lines will be needed. Since recent research in colon and breast cancer cell lines has revealed that miR-210 over-expression in hypoxia is induced in a HIF1α dependent pathway [10,11] the present study adds to other studies in suggesting HIF1α and miR-210 to be master regulators in hypoxia.

MiRNA profiling also suggested miR-1908 and miR-4327 to be upregulated by hypoxia, but only with fold changes close to 1. Mir-1908 has previously been identified as an endogenous promoter of metastatic invasion, and colonization in metastatic melanoma cell lines [44]. Moreover, it has been described to be involved in the regulation of the MAPK pathway in chordomas [45] and it is furthermore linked to diverse immune response pathways [46]. To our knowledge, no results exits on gliomas and no publications concerning the expression and/or function of miR-4327 are available at present.

Unfortunately it was not possible to demonstrate a significant hypoxia-induced upregulation of any miRNAs in the CCL cultures. A high level of mutations acquired by these cell lines might explain this.

Comparing the miRNA profiling results between CCL and GSS cultures six miRNAs were found to be differentially regulated. In both hypoxia and normoxia, miR-9 was upregulated in GSS cultures compared with CCL cultures. Since the GSS cultures applied in this study possess stem cell characteristics such as neurosphere formation, self-renewal, and formation of invasive patient-like tumors in nude mice this might suggest that miR-9 is related to tumor stem cell functions. This is supported by a recent study, where miR-9 was found to be highly upregulated in glioblastoma stem cells [47].

Besides miR-9, miR-93 also had a higher expression in GSS cultures compared with CCL cultures, though only under hypoxic conditions. MiR-93 has previously been described to be higher expressed in glioma cells compared with normal brain cells [48]. Various functions have been suggested for miR-93 in cancer. It has been demonstrated that miR-93 promotes immune escape by inhibiting the activity of NK cells in the immune system [48]. In addition, a study carried out on glioma cell lines has shown that miR-93 promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis by targeting integrin-β8 [49]. Moreover, it has been suggested as a promising biomarker for lung cancer [50], triple-negative breast cancer [51], and gastric cancer [52].

MiR-27a, miR-27b, SNORD14B, and miR-625* were all found to be significantly higher expressed in CCL cultures compared with GSS cultures. Among these, only studies of miR-27a and miR-27b have previously been reported. Two studies have reported miR-27b to be upregulated in response to hypoxia in colon cancer cells [10,12] and in addition, Kulshreshtha et al. have reported miR-27a to be upregulated by hypoxia in these cells. However, hypoxia-induced upregulation was not found in our CLL cultures.

The remarkable overall variations in the expression of miRNAs between the individual cell lines may arise from the fact that glioblastomas are very heterogeneous tumors and consist of different molecular subtypes [53]. Though big variations were seen between all cell lines, the miRNA profiles of the three GSS cultures were more similar than either of them was to the profiles of the two CCL cultures. The clustering of the three GSS cultures is probably the result of different culturing conditions compared with the CCL cultures. Our GSS cultures were established and grown in a serum-free medium for only a few passages (T78 and T87 for 9 passages and T86 for 16 passages). Such cultures have earlier been shown to maintain both the phenotype and the genotype of the primary tumor even after several passages [25]. In specific, our GSS cultures have after several passages repeatedly been shown to generate spheroids expressing stem cell markers. Additionally, they have been shown to be tumorigenic when injected into immunosuppressed mice. The CCL cultures, on the other hand, have been passed countless times and have through these passages been cultured in a serum-containing medium. Consequently, they might have acquired several characteristics not present in the primary tumor [54].

We found no systematic hypoxia-induced upregulation of stem cell markers as earlier found in long-term hypoxia [19–21]. However, we found significant upregulations of Musashi-1 in two of five cell lines and significant upregulations of CD133, Bmi-1, and SOX2 in one cell line each. Significant downregulation of ID1 was seen in three of five cell lines while CD15 was significantly downregulated in two cell lines. In one cell line SOX2 was significantly downregulated. We did not see any significant alterations of nestin in any cell line.

As seen in Figure 4 the staining for SOX2 was ambiguous since both significant up- (T78) and down-regulation (T87) was seen in response to hypoxia. Previous research has demonstrated a hypoxia-induced SOX2 upregulation [20,55] and hence this was expected in the present study as well. Additionally, upregulation of CD133 and Bmi-1 in response to hypoxia has previously been observed [20]. To our knowledge, no other reports of hypoxia-induced downregulation of CD15 or ID1 are available at present. On the contrary, ID1 has recently been reported to be upregulated in hypoxic nonmalignant mammary epithelial cells [56]. Therefore, additional research is needed to clarify the expression patterns of these markers.

Since hypoxia has previously been demonstrated to promote the self-renewal of cancer stem cells and maintain the undifferentiated phenotype [1,20] a clearer tendency of hypoxia-induced upregulation of stem cell markers was expected. However, this hypothesis was based on previous research that has demonstrated a long-term hypoxia-induced upregulation of diverse stem cell markers [19–21,55]. Besides, only a few of the stem cell markers applied in this study (CD133 [1,20,55], SOX2 [20,55,57], Bmi-1 [20], nestin [20], Oct-4 [57,58], and ID1 [56]) have been used in the studies of hypoxia, whereas other markers (CD15 and Musashi-1) are still new in this context.

All together, the study presented here has not given any clear-cut picture of the regulation of the expression of stem cell markers in glioblastoma cell lines in acute hypoxia. The acute hypoxia-induced changes of the cellular differentiation might be very complex resulting in up- or down-regulation of specific markers dependent on at which level these markers play a role in the differentiation hierarchy. Explaining regulatory differences between cell lines it is important to stress that glioblastomas are very heterogeneous tumors. Therefore the different patterns might be a result of complex mechanisms being dependent on, e.g., mutational status and molecular subtype [53] including the glioma CpG island methylator phenotype (G-CIMP) [59].

Conclusion & future perspective

Our study showed for the first time a hypoxia-induced upregulation of miR-210 in glioma stem cell-containing spheroid cultures and thereby we add to other studies in suggesting HIF1α and miR-210 to be master regulators of hypoxia. Moreover, our study demonstrated that variations in the response to hypoxia exist among glioblastomas in the expression of both miRNAs and stem cell markers. Considering this variation, together with the potential importance of the interplay between hypoxia, miRNAs, and tumor stem cells in therapeutic resistance, this study suggests that individualized therapies might be necessary in the fight against glioblastomas.

In the future, the setup used in the present study can be extended in order to study the regulation of miRNAs as well as stem cell markers in glioma stem cell-containing spheroids exposed to long-term hypoxia. Moreover, in order to clarify the exact role of miR-210 in glioblastoma malignancy as well as its target genes, functional experiments including glioma stem cell-spheroid cultures from different patients will be needed. Interrogation of the key mechanisms in both acute and long-term hypoxia will be highly relevant since both of these microenviromental challenges are supposed to be frequently occurring in glioblastomas.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.

Big variations in the expression of miRNAs and stem cell markers are observed between cell lines.

MiR-210 is significantly upregulated (>twofold) in acute hypoxia compared with normoxia in glioma stem cell-containing spheroid cultures.

The hypoxia inducible factor HIF1α is highly expressed in glioma stem cell-containing spheroid cultures in acute hypoxia.

In glioma stem cell-containing spheroid cultures HIF2α is hardly detectable in acute hypoxia.

No systematic acute hypoxia-induced upregulation of stem cell markers is seen, indicating that the acute hypoxia-induced changes in the differentiation might be very complex resulting in up- or down-regulation of specific markers dependent on at which level these markers play a role in the differentiation hierarchy.

CD133, Musashi-1 and Bmi-1 tend to be upregulated in acute hypoxia.

CD15 and ID1 shows a tendency of a hypoxia-induced downregulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The excellent laboratory work of Tanja Dreehsen Højgaard and Helle Wohlleben is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was supported by the Region of Southern Denmark, The Research Council for Health and Disease (FSS), The grant of Else and Åge Grønbæk-Olsen, The Foundation of Merchant M. Kristian Kjær and wife Margrethe Kjær born la Cour-Holmen, the grant of FMR. Dir. Leo Nielsen and wife Karen Margrethe Nielsen for medicalbasic research, The Beckett Foundation, The Foundationof Fam. Hede Nielsen, The Foundation of Dir. JacobMadsen and wife Olga Madsen and The Foundation ofengineer Bent Bøgh and wife Inge Bøgh. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

References

- 1.Soeda A, Park M, Lee D, et al. Hypoxia promotes expansion of the CD133-positive glioma stem cells through activation of HIF-1alpha. Oncogene. 2009;28(45):3949–3959. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao S, Wu Q, Mclendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dirks PB. Brain tumor stem cells: bringing order to the chaos of brain cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(17):2916–2924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.6792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang MK, Hur BI, Ko MH, Kim CH, Cha SH, Kang SK. Potential identity of multi-potential cancer stem-like subpopulation after radiation of cultured brain glioma. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang MK, Kang SK. Tumorigenesis of chemotherapeutic drug-resistant cancer stem-like cells in brain glioma. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16(5):837–847. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, et al. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol. Cancer. 2006;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ropolo M, Daga A, Griffero F, et al. Comparative analysis of DNA repair in stem and nonstem glioma cell cultures. Mol. Cancer Res. 2009;7(3):383–392. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren Y, Zhou X, Mei M, et al. MicroRNA-21 inhibitor sensitizes human glioblastoma cells U251 (PTEN-mutant) and LN229 (PTEN-wild type) to taxol. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNA functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulshreshtha R, Ferracin M, Wojcik SE, et al. A microRNA signature of hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27(5):1859–1867. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01395-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camps C, Buffa FM, Colella S, et al. hsa-miR-210 Is induced by hypoxia and is an independent prognostic factor in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1340–1348. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guimbellot JS, Erickson SW, Mehta T, et al. Correlation of microRNA levels during hypoxia with predicted target mRNAs through genome-wide microarray analysis. BMC Med. Genomics. 2009;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hua Z, Lv Q, Ye W, et al. MiRNA-directed regulation of VEGF and other angiogenic factors under hypoxia. PLoS ONE. 2006;1:e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamagata T, Yoshizawa J, Ohashi S, Yanaga K, Ohki T. Expression patterns of microRNAs are altered in hypoxic human neuroblastoma cells. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2010;26(12):1179–1184. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mccormick R, Buffa FM, Ragoussis J, Harris AL. The role of hypoxia regulated microRNAs in cancer. Curr. Top Microbiol. Immunol. 2010;345:47–70. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lages E, Guttin A, El Atifi M, et al. MicroRNA and target protein patterns reveal physiopathological features of glioma subtypes. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e20600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal R, Pandey P, Jha P, Dwivedi V, Sarkar C, Kulshreshtha R. Hypoxic signature of microRNAs in glioblastoma: insights from small RNA deep sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:686. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang W, Wei J, Guo T, Shen Y, Liu F. Knockdown of miR-210 decreases hypoxic glioma stem cells stemness and radioresistance. Exp. Cell Res. 2014;326(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heddleston JM, Li Z, Mclendon RE, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. The hypoxic microenvironment maintains glioblastoma stem cells and promotes reprogramming towards a cancer stem cell phenotype. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 2009;8(20):3274–3284. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.20.9701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolenda J, Jensen SS, Aaberg-Jessen C, et al. Effects of hypoxia on expression of a panel of stem cell and chemoresistance markers in glioblastoma-derived spheroids. J. Neurooncol. 2011;103(1):43–58. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Bao S, Wu Q, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(6):501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmquist-Mengelbier L, Fredlund E, Lofstedt T, et al. Recruitment of HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha to common target genes is differentially regulated in neuroblastoma: HIF-2alpha promotes an aggressive phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(5):413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang X, Ding L, Bennewith KL, et al. Hypoxia-inducible mir-210 regulates normoxic gene expression involved in tumor initiation. Mol. Cell. 2009;35(6):856–867. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen SS, Aaberg-Jessen C, Andersen C, Schroder HD, Kristensen BW. Glioma spheroids obtained via ultrasonic aspiration are viable and express stem cell markers: a new tissue resource for glioma research. Neurosurgery. 2013;73(5):868–886. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000118. discussion 886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J, Kotliarova S, Kotliarov Y, et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(5):391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aaberg-Jessen C, Norregaard A, Christensen K, Pedersen CB, Andersen C, Kristensen BW. Invasion of primary glioma- and cell line-derived spheroids implanted into corticostriatal slice cultures. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013;6(4):546–560. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen K, Aaberg-Jessen C, Andersen C, Goplen D, Bjerkvig R, Kristensen BW. Immunohistochemical expression of stem cell, endothelial cell, and chemosensitivity markers in primary glioma spheroids cultured in serum-containing and serum-free medium. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(5):933–947. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000368393.45935.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Genbacev O, Krtolica A, Kaelin W, Fisher SJ. Human cytotrophoblast expression of the von Hippel-Lindau protein is downregulated during uterine invasion in situ and upregulated by hypoxia in vitro . Dev. Biol. 2001;233(2):526–536. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbertson RJ, Rich JN. Making a tumour's bed: glioblastoma stem cells and the vascular niche. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7(10):733–736. doi: 10.1038/nrc2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibahara J, Kashima T, Kikuchi Y, Kunita A, Fukayama M. Podoplanin is expressed in subsets of tumors of the central nervous system. Virchows Arch. 2006;448(4):493–499. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loveless W, Feizi T, Valeri M, Day R, Bay S. A monoclonal antibody, MIN/3/60, that recognizes the sulpho-Lewis(x) and sulpho-Lewis(a) sequences detects a sub-population of epithelial glycans in the crypts of human colonic epithelium. Hybridoma. 2001;20(4):223–229. doi: 10.1089/027245701753179794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry J, Ho M, Viero S, Zheng K, Jacobs R, Thorner PS. The intermediate filament nestin is highly expressed in normal human podocytes and podocytes in glomerular disease. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2007;10(5):369–382. doi: 10.2350/06-11-0193.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li YF, Xiao B, Tu SF, Wang YY, Zhang XL. Cultivation and identification of colon cancer stem cell-derived spheres from the Colo205 cell line. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2012;45(3):197–204. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madsen C, Schroder HD. Ki-67 immunoreactivity in meningiomas – determination of the proliferative potential of meningiomas using the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. Clin. Neuropathol. 1997;16(3):137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones TD, Maclennan GT, Bonnin JM, Varsegi MF, Blair JE, Cheng L. Screening for intratubular germ cell neoplasia of the testis using OCT4 immunohistochemistry. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006;30(11):1427–1431. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213288.50660.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dahlstrand J, Collins VP, Lendahl U. Expression of the class VI intermediate filament nestin in human central nervous system tumors. Cancer Res. 1992;52(19):5334–5341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hao F, Pysz MA, Curry KJ, et al. Protein kinase Calpha signaling regulates inhibitor of DNA binding 1 in the intestinal epithelium. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(20):18104–18117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.208488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ju Y, Yang J, Liu R, et al. Antigenically dominant proteins within the human liver mitochondrial proteome identified by monoclonal antibodies. Sci. China Life Sci. 2011;54(1):16–24. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-4115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura Y, Kanemura Y, Yamada T, et al. D2–40 antibody immunoreactivity in developing human brain, brain tumors and cultured neural cells. Mod. Pathol. 2006;19(7):974–985. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomassen M, Skov V, Eiriksdottir F, et al. Spotting and validation of a genome wide oligonucleotide chip with duplicate measurement of each gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;344(4):1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomassen M, Tan Q, Eiriksdottir F, Bak M, Cold S, Kruse TA. Prediction of metastasis from low-malignant breast cancer by gene expression profiling. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120(5):1070–1075. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devlin C, Greco S, Martelli F, Ivan M. miR-210: more than a silent player in hypoxia. IUBMB Life. 2011;63(2):94–100. doi: 10.1002/iub.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noman MZ, Buart S, Romero P, et al. Hypoxia-inducible miR-210 regulates the susceptibility of tumor cells to lysis by cytotoxic T cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72(18):4629–4641. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pencheva N, Tran H, Buss C, et al. Convergent multi-miRNA targeting of ApoE drives LRP1/LRP8-dependent melanoma metastasis and angiogenesis. Cell. 2012;151(5):1068–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Long C, Jiang L, Wei F, et al. Integrated miRNA-mRNA analysis revealing the potential roles of miRNAs in chordomas. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e66676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kohno T, Tsuge M, Murakami E, et al. Human microRNA hsa-miR-1231 suppresses hepatitis B virus replication by targeting core mRNA. J. Viral Hepat. 2014;21(9):e89–97. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schraivogel D, Weinmann L, Beier D, et al. CAMTA1 is a novel tumour suppressor regulated by miR-9/9* in glioblastoma stem cells. EMBO J. 2011;30(20):4309–4322. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Codo P, Weller M, Meister G, et al. MicroRNA-mediated down-regulation of NKG2D ligands contributes to glioma immune escape. Oncotarget. 2014;5(17):7651–7662. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fang L, Deng Z, Shatseva T, et al. MicroRNA miR-93 promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis by targeting integrin-beta8. Oncogene. 2011;30(7):806–821. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du L, Zhao Z, Ma X, et al. miR-93-directed downregulation of DAB2 defines a novel oncogenic pathway in lung cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33(34):4307–4315. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu J, Xu J, Wu Y, et al. Identification of microRNA-93 as a functional dysregulated miRNA in triple-negative breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2611-8. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang R, Wang W, Li F, Zhang H, Liu J. MicroRNA-106b˜25 expressions in tumor tissues and plasma of patients with gastric cancers. Med. Oncol. 2014;31(10):243. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(1):98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lund-Johansen M, Engebraaten O, Bjerkvig R, Laerum OD. Invasive glioma cells in tissue culture. Anticancer Res. 1990;10(5A):1135–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bar EE, Lin A, Mahairaki V, Matsui W, Eberhart CG. Hypoxia increases the expression of stem-cell markers and promotes clonogenicity in glioblastoma neurospheres. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177(3):1491–1502. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaapil M, Helczynska K, Villadsen R, et al. Hypoxic conditions induce a cancer-like phenotype in human breast epithelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e46543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mathieu J, Zhang Z, Zhou W, et al. HIF induces human embryonic stem cell markers in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71(13):4640–4652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Z, Rich JN. Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors in cancer stem cell maintenance. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010;345:21–30. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiestler B, Capper D, Hovestadt V, et al. Assessing CpG island methylator phenotype, 1p/19q codeletion, and MGMT promoter methylation from epigenome-wide data in the biomarker cohort of the NOA-04 trial. Neuro Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou138. pii: nou138. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.