Abstract

N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-esters are widely used to label proteins non-selectively on free amino groups. Such broad labeling can be disadvantageous because it can interfere with protein structure or function and because stoichiometry is poorly controlled. Here we describe a simple method to transform NHS-esters into site-specific protein labeling on N-terminal Cys residues. MESNA addition converts NHS-esters to chemoselective thioesters for N-Cys modification. This labeling strategy was applied to clarify mechanistic features of the ubiquitin E3 ligase WWP2 including its interaction with one of its substrate, the tumor suppressor PTEN, as well as its autoubiquitination molecularity. We propose that this convenient protein labeling strategy will allow for an expanded application of NHS-esters in biochemical investigation.

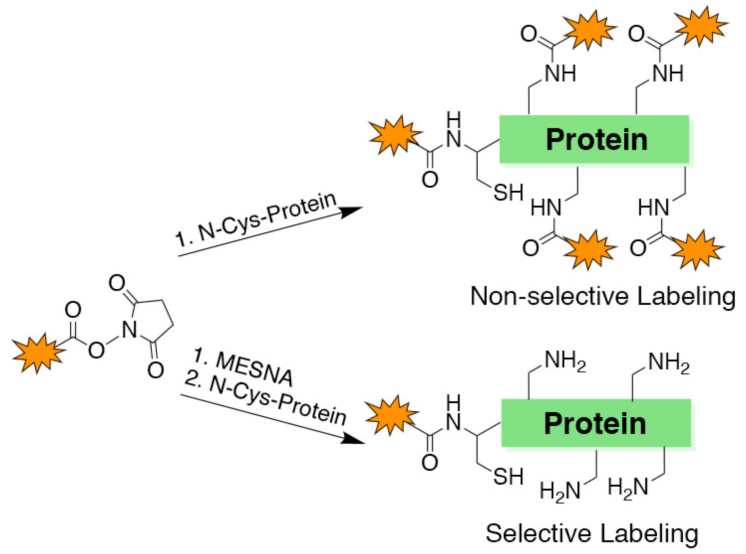

Protein labeling on lysine residues with fluorophores, affinity tags, crosslinkers, and immobilization reagents is commonly performed with N-hydroxy-succinimide (NHS) ester derivatives in the study of protein structure, function, and mechanism.1 There are more than 1000 commercially available NHS esters (Figure S1) that are used in protein science and some of the routine examples are NHS-biotin, NHS-fluorescein, and NHS-rhodamine. Biotin tagging for affinity chromatography experiments or for western blots and fluorescein and rhodamine labeling for fluorescence studies are common biochemical procedures. Despite their broad availability and widespread utilization, NHS ester modifying reactions on proteins are limited by their lack of site-specificity (Figure 1A).1,2 Although NHS esters are relatively selective for amino groups in proteins, most proteins have numerous Lys residues that can be heterogeneously modified by these reagents. Lys is one of the abundant amino acids in biological protein sequences3 and a typical 250 aa protein would be predicted to have around 20 Lys residues. Non-selective labeling of Lys sidechains in proteins can alter protein conformation and function and complicate biophysical analysis.

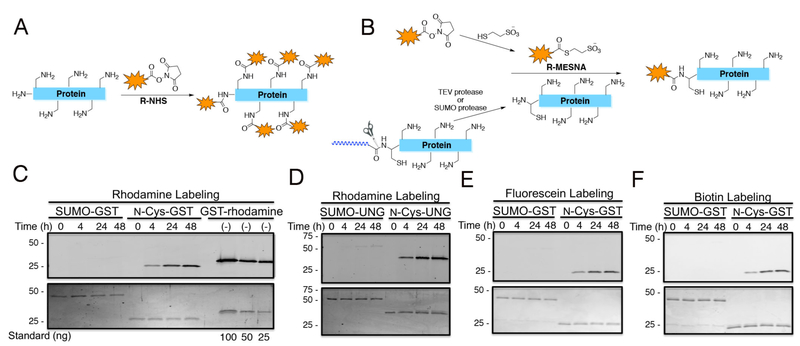

Figure 1.

Site-specific labeling of protein N-termini. (A) Scheme showing non-specific labeling of amino groups with NHS-containing reagents. (B) Scheme showing site-specific N-terminal labeling of proteins using our one-pot strategy. (C) Labeling GST with rhodamine. (D) Labeling UNG with rhodamine. (E) Labeling GST with fluorescein. (F) Labeling GST with biotin-PEG4. All labeling reagents originated from an R-NHS. Top gel corresponds to fluorescence imaging or biotin Western blotting. Bottom gel corresponds to the colloidal stained loading control.

The 'native chemical ligation' reaction has become a popular method for protein semisynthesis and involves the chemoselective reaction between an N-terminal Cys of one peptide and a C-terminal thioester of another.4,5 N-terminal Cys residues in proteins can be obtained using insertional mutagenesis and site-specific proteolysis by TEV or SUMO protease.6,7 N-terminal Cys ligations of recombinant proteins with synthetic peptide thioesters are now routine but less commonly performed with small molecule thioesters,8-10 including aroyl thioesters as found in fluorescein, which could have attenuated reactivity. Moreover, the chemical synthesis of small molecule thioesters is a significant obstacle to many biologists who might otherwise consider adapting native chemical ligation to N-terminally label a protein of interest.11,12 As NHS esters could in principle be efficiently transesterified with mercaptoethanesulfonate (MESNA), we hypothesized that pretreatment of commercial NHS esters with MESNA could then be used to specifically label recombinant proteins possessing N-Cys residues (Figure 1B).

We chose glutathione S-transferase (GST) and uracil DNA glycosylase (hUNG2) as two model proteins to investigate N-terminal labeling. N-Cys was furnished using SUMO protease cleavage of the corresponding N-terminal fusion proteins.13 To provide a guide to the efficiency of ligating rhodamine thioester, we prepared purified rhodamine benzylmercaptan from the corresponding NHS-ester and analyzed its reaction with GST. As expected, it was observed that GST was efficiently labeled with rhodamine benzylmercaptan in the presence of MESNA and the reaction plateaued after 48 h at room temperature at pH 7 (Figure S2A). In contrast, SUMO-GST which lacks an N-Cys showed <5% labeling under these conditions. By comparison, rhodamine NHS ester labeled both SUMO cleaved and SUMO fused GST with similar efficiently, consistent with its known reactivity as a non-selective Lys labeling agent (Figure S2B). We then developed a one pot strategy in which rhodamine-NHS was treated with MESNA and then the mixture, without further purification, was added to SUMO cleaved and SUMO-fusion forms of GST and hUNG2 (Figures 1C, 1D, and S2B). These experiments revealed robust fluorescent labeling of only the SUMO cleaved enzymes. Similar results were obtained with fluorescein-NHS and biotin-NHS labeling of GST, the latter visualized by western blot (Figures 1E and 1F). To quantify GST labeling, we employed GST that was stoichiometrically labeled with rhodamine as a standard prepared by expressed protein ligation5 which showed 82±7% conversion (Figure 1C). Taken together, these results suggest that MESNA-pretreated NHS-esters can be employed to label proteins site-specifically on N-Cys residues in proteins.

We then applied this labeling technology to clarify aspects of the ubiquitin ligase activity of WWP2, including its interactions with a tumor suppressor protein substrate PTEN and the molecularity of WWP2's autoubiquitination. WWP2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that can ubiquitinate itself and other proteins on Lys residues.14-16 WWP2 has a catalytic HECT domain that contains an active site Cys (C838) that forms a covalent ubiquitin thioester intermediate received from a ubiquitin-E2 thioester. The ubiquitin-E3 thioester species then delivers the ubiquitin to Lys residues in WWP2 and its protein substrates like PTEN.14-16 WWP2 includes a non-essential N-terminal C2 domain deleted here for ease of expression followed by four WW domains (WW1-WW4) and a C-terminal HECT domain. It has recently been shown that the ~30 aa linker that connects the WW2 and WW3 domains, the 2,3-linker, is a key autoinhibitory module that limits WWP2 ubiquitin ligase activity.17 A non-substrate engineered ubiquitin variant (Ubv) can bind tightly and specifically to its HECT domain allosteric site,18-20 displacing the 2,3-linker and relieving autoinhibition of WWP2.17,21

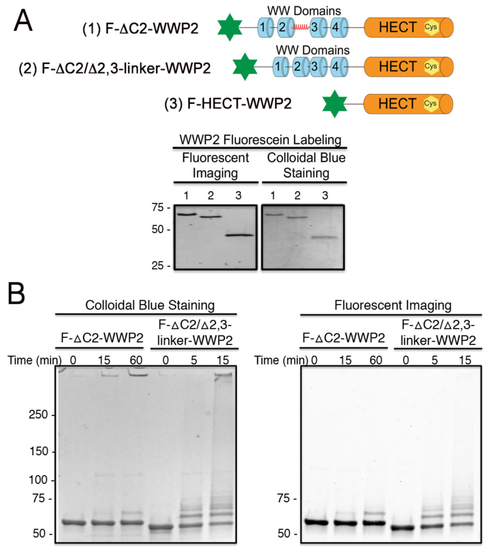

It has previously been demonstrated that tetraphosphorylated PTEN (4p-PTEN) is conformationally closed and is a weaker substrate of WWP2 than non-phosphorylated PTEN (n-PTEN), perhaps through 4p-PTEN's depressed affinity for WWP2.23-26 To quantitatively evaluate PTEN's solution phase interaction with WWP2 using fluorescence anisotropy, we used the aforementioned labeling strategy to install an N-terminal fluorescein onto several WWP2 protein forms. In particular, we prepared F-ΔC2-WWP2, F-ΔC2/Δ2,3-linker-WWP2, and F-HECT-WWP2 (Figure 2A). Fluorescent labeling of these WWP2 forms proceeded smoothly, and it was shown that uncleaved GST-WWP2 displayed minimal labeling under the reaction conditions, indicating that N-Cys containing WWP2 forms were specifically labeled N-terminally (Figure S2C). We showed that the standard enzymatic behaviors17 were preserved in the F-ΔC2-WWP2 and F-ΔC2/Δ2,3-linker-WWP2 forms, with 2,3-linker deletion sharply stimulating autoubiquitination (Figure 2B, note different times).

Figure 2.

N-terminal labeling of WWP2s with fluorescein for biochemical analysis. (A) Generation of F-ΔC2-WWP2, F-ΔC2/Δ2,3-linker-WWP2 and F-HECT-WWP2. (B) Enzyme assay showing that WWP2 autoinhibition is preserved after labeling. Enzyme assays were carried out with 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 50 μM ubiquitin, 1.5 μM E2 protein, 1 μM E3 and initiated with 50 nM E1 at 30°C. Both colloidal staining and fluorescence imaging (excitation 490 nm, emission 520 nm) are shown.

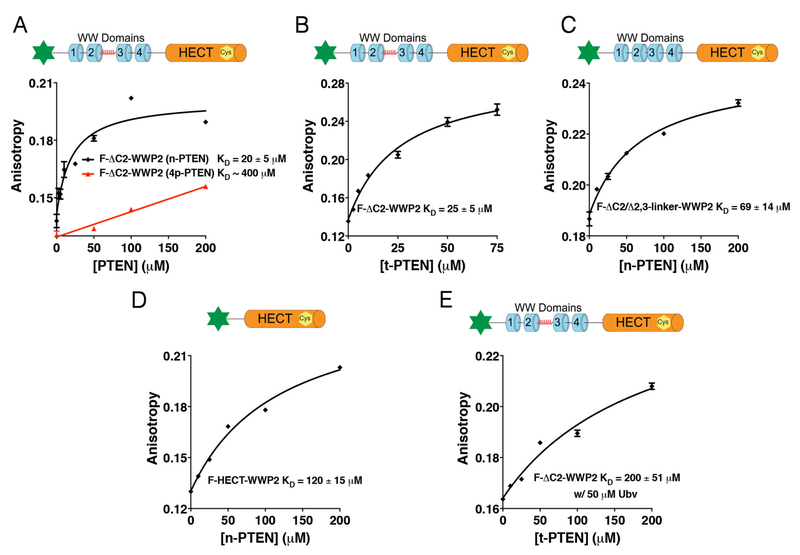

Fluorescence binding assays were initially performed with F-ΔC2-WWP2 and n-PTEN and C-terminally truncated (t-PTEN). These showed fairly similar affinities, KD of 20 μM and 25 μM for n-PTEN and t-PTEN, respectively (Figures 3A and 3B). These results show that the easier to prepare t-PTEN can be used as a surrogate for n-PTEN as the deleted 25 residues seem to make little direct contribution to WWP2 interaction. In contrast, the binding of F-ΔC2-WWP2 with 4p-PTEN was considerably weaker and was at the upper limit of detection, with KD ~400 μM (Figure 3A). This indicates that the conformationally closed form of PTEN23 cannot efficiently bind WWP2, readily accounting for 4p-PTEN's resistance to WWP2 catalyzed ubiquitination. To learn more about how WWP2 interacts with n-PTEN, we investigated n-PTEN's interactions with F-ΔC2/Δ2,3-linker-WWP2 and F-HECT-WWP2 using fluorescence binding assays. These experiments revealed that both of these WWP2 forms bound n-PTEN with decreased affinity with KD of 69 μM for F-ΔC2/Δ2,3-linker-WWP2 and 120 μM for F-HECT-WWP2 (Figures 3C and3D). The weak affinity of F-ΔC2/Δ2,3-linker-WWP2 for n-PTEN was unexpected since there is only a 30 amino acid deletion relative to F-ΔC2-WWP2 and the linker forms an alpha helix that makes intimate interactions with the HECT domain,17 suggesting it may not be available for PTEN interaction.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence anisotropy assay to determine binding constants of different WWP2s with PTENs. (A) Binding assay for F-ΔC-WWP2 with n-PTEN or 4p-PTEN. (B) Binding assay for F-ΔC-WWP2 with t-PTEN. (C) Binding assay for F-ΔC/Δ2,3-linker-WWP2 with n-PTEN. (D) Binding assay for F-HECT-WWP2 with n-PTEN. (E) Binding assay for F-ΔC-WWP2 with t-PTEN in the presence of 50 μM Ubv.

To further analyze n-PTEN/WWP2 interactions, we performed the fluorescence binding experiment of F-ΔC2-WWP2 with t-PTEN in the presence of allosteric ubiquitin ligand Ubv which can disrupt the intramolecular 2,3-linker/HECT domain interaction.17,21 We found that addition of Ubv to F-ΔC2-WWP2 with t-PTEN markedly weakened the F-ΔC2-WWP2/n-PTEN interaction (Figure 3E). These results suggest that direct binding of the 2,3-linker to PTEN does not account for the difference between F-ΔC2-WWP2 and F-ΔC2/Δ2,3-linker-WWP2 in their PTEN interactions. Rather, the Ubv inhibitory effects on WWP2/PTEN binding suggest that the more rigidly held WW1-WW4 cluster in F-ΔC2-WWP2 in the absence of Ubv is necessary for maximal affinity with PTEN. Consistent with this idea, the lack of the WW1-WW4 cluster in F-HECT-WWP2 is associated with diminished PTEN interaction. Overall, these results indicate that a fine balance of PTEN and WWP2 conformation and domain architecture are important for their interaction and PTEN's ubiquitination by WWP2.

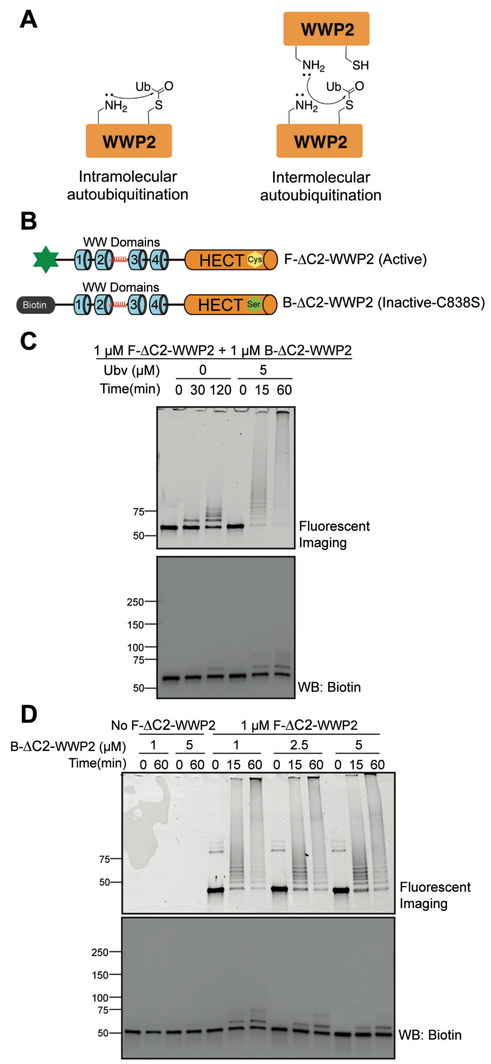

An unresolved aspect of WWP2's catalytic properties is whether WWP2 autoubiquitination occurs intramolecularly (in cis) or intermolecularly (in trans) (Figure 4A). We employed the N-terminal labeling approach to help address the molecular mechanism of autoubiquitination. In this strategy, we label catalytically inert C838S ΔC2-WWP2 with a biotin (B-ΔC2-WWP2) and utilize catalytically active F-ΔC2-WWP2 as described above (Figure 4B). We performed autoubiquitination reactions containing a mixture of the biotin-labeled inactive WWP2 and fluorescein-labeled active WWP2 forms and then evaluated the pattern of ubiquitin conjugate products based on the orthogonal tags. These experiments revealed detectable WWP2 autoubiquitination activity with both fluorescein imaging and biotin western blotting. Although the degree of reaction was modest as expected for both forms, the fluorescein labeled protein showed a greater extent of ubiquitination (Figure 4C). In the absence of F-ΔC2-WWP2, there was no detectable ubiquitination of the B-ΔC2-WWP2 indicating that the observed ubiquitination of the biotinylated WWP2 form does not come from residual catalytic activity of the Cys mutant form or non-specific effects of the E2 ligase present (Figure S3A).

Figure 4.

Molecularity of WWP2 autoubiquitination. (A) Scheme of intermolecular vs. intramolecular autoubiquitination. (B) WWP2s generation for this study (F-ΔC2-WWP2 and B-ΔC2-WWP2). (C) Enzyme assays revealing Ubv’s influence on the molecularity of WWP2 autoubiquition. (D) Enzyme assays revealing the influence of increasing concentrations of B-ΔC2-WWP2 on the molecularity of WWP2 autoubiquition in the presence of 5 μM Ubv. Sample volume was adjusted to load equal amounts of B-ΔC2-WWP2 to each lane for Western blot analysis.

We also examined the effect of the allosteric activator Ubv on intermolecular versus intramolecular WWP2 autoubiquitination.17,21 Ubv stimulated WWP2 ubiquitination in both fluorescein imaging and biotin blotting but the degree of enhancement was much greater with the fluorescein labeled WWP2 form (Figure 4C). These results suggest that Ubv primarily stimulates intramolecular autoubiquitination, perhaps by increasing the proximity of key Lys residues in WWP2 to the C838 ubiquitin thioester. We also examined the impact of increasing the concentration of B-ΔC2-WWP2 from 1 to 5 μM at fixed, 1 μM F-ΔC2-WWP2 in the presence of Ubv. These results showed that the rate of B-ΔC2-WWP2 ubiquitination increased proportionally but there was no apparent effect on the ubiquitination of F-ΔC2-WWP2 (Figure 4D). Our results indicate that WWP2 predominantly catalyzes its autoubiquitination via intramolecular ubiquitin transfer. As for the modest autoubiquitination of catalytically inert B-ΔC2-WWP2, our results are consistent with intermolecular ubiquitination being a second order process in this concentration range, since WWP2 is monomeric.

In summary, we have described a simple method for highly selective protein labeling using readily available NHS reagents and demonstrated the utility of this method for analyzing molecular mechanisms related to an E3 ubiquitin ligase, WWP2. As the uncleaved control proteins investigated have 30 to 45 internal Lys and 4 to 13 internal Cys and show <5% labeling, we estimate that the average individual internal Lys or Cys is getting labeled <0.2% under the reaction conditions. Such low levels of off-target labeling should be acceptable for most biochemical investigation. We believe that the labeling strategy could be extended beyond fluorescent tagging and affinity reagents to the incorporation of cross-linking groups and for immobilizing proteins on resins or surfaces for systems biology applications. We think that its ease of use will allow the facile adaptation of this labeling method by labs without sophistication in synthetic chemistry.

Regarding WWP2, we have uncovered unexpected features that govern how WWP2 binds to its protein substrate PTEN and how it undergoes autoubiquitination. Of note, reduced affinity of WWP2 for PTEN after loss or displacement of its 'inhibitory' 2,3-linker suggests that autoubiquitination and protein substrate ubiquitination are differentially sensitive to allosteric influences. These findings help explain prior work that WWP2 autoubiquitination relative to WWP2-mediated PTEN ubiquitination is much more susceptible to deletion of the WWP2's 2,3-linker.14 Our results also provide firm evidence that WWP2 undergoes predominantly intramolecular autoubiquitination rather than through an intermolecular mechanism that has been proposed for other ubiquitin ligases.27,28

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work has been supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH CA74305 and NIH GM120855).

Footnotes

Supporting Information.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental methods, Supplementary Figures S1-S5.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hermanson G Bioconjugate Techniques 3rd ed.; Academic Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Koniev O; Wagner A Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 5495–5551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Brooks DJ; Fresco JR; Lesk AM; Singh M Mol. Biol. Evol 2002, 19, 1645–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Dawson PE; Muir TW; Clark-Lewis I; Kent SB Science 1994, 266, 776–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Muir TW; Sondhi D; Cole PA Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1998, 95, 6705–6710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Kapust RB; Tozser J; Copeland TD; Waugh DS Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2002, 294, 949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Malakhov MP; Mattern MR; Malakhova OA; Drinker M; Weeks SD; Butt TR J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 2004, 5, 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Erlanson DA; Chytil M; Verdine GL Chem. Biol 1996, 3, 981–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rosen CB; Francis MB Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 7, 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Chen Z; Cole PA Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 28, 115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Tolbert TJ; Wong CH Angew. Chem 2002, 41, 2171–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Yi L; Sun H; Itzen A; Triola G; Waldmann H; Goody RS; Wu YW Angew. Chem 2011, 50, 8287–8290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Weiser BP; Stivers JT; Cole PA Biophys. J 2017, 113, 393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Buetow L; Huang DT Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2016, 17, 626–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Scheffner M; Kumar S Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Maddika S; Kavela S; Rani N; Palicharla VR; Pokorny JL; Sarkaria JN; Chen J Nat. Cell Biol 2011, 13, 728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chen Z; Jiang H; Xu W; Li X; Dempsey DR; Zhang X; Devreotes P; Wolberger C; Amzel LM; Gabelli SB; Cole PA Mol. cell 2017, 66, 345–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ogunjimi AA; Wiesner S; Briant DJ; Varelas X; Sicheri F; Forman-Kay J; Wrana JL J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 6308–6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kim HC; Steffen AM; Oldham ML; Chen J; Huibregtse JM EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Maspero E; Mari S; Valentini E; Musacchio A; Fish A; Pasqualato S; Polo S EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 342–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhang W; Wu KP; Sartori MA; Kamadurai HB; Ordureau A; Jiang C; Mercredi PY; Murchie R; Hu J; Persaud A; Mukherjee M; Li N; Doye A; Walker JR; Sheng Y; Hao Z; Li Y; Brown KR; Lemichez E; Chen J; Tong Y; Harper JW; Moffat J; Rotin D; Schulman BA; Sidhu SS Mol. cell 2016, 62, 121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Chen Z; Thomas SN; Bolduc DM; Jiang X; Zhang X; Wolberger C; Cole PA Biochemistry 2016, 55, 3658–3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bolduc D; Rahdar M; Tu-Sekine B; Sivakumaren SC; Raben D; Amzel LM; Devreotes P; Gabelli SB; Cole P eLife 2013, 2, e00691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rahdar M; Inoue T; Meyer T; Zhang J; Vazquez F; Devreotes PN Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2009, 106, 480–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Nguyen HN; Yang JM; Miyamoto T; Itoh K; Rho E; Zhang Q; Inoue T; Devreotes PN; Sesaki H; Iijima M Sci. Rep 2015, 5, 12600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Nguyen HN; Afkari Y; Senoo H; Sesaki H; Devreotes PN; Iijima M Oncogene 2014, 33, 5688–5696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Scaglione KM; Bansal PK; Deffenbaugh AE; Kiss A; Moore JM; Korolev S; Cocklin R; Goebl M; Kitagawa K; Skowyra D Mol. Cell. Biol 2007, 27, 5860–5870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Mouchantaf R; Azakir BA; McPherson PS; Millard SM; Wood SA; Angers A J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 38738–38747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.