Abstract

Membrane-bound proteinase 3 (PR3m) is the main target antigen of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA) in granulomatosis with polyangiitis, a systemic small-vessel vasculitis. Binding of ANCA to PR3m triggers neutrophil activation with the secretion of enzymatically active PR3 and related neutrophil serine proteases, thereby contributing to vascular damage. PR3 and related proteases are activated from pro-forms by the lysosomal cysteine protease cathepsin C (CatC) during neutrophil maturation. We hypothesized that pharmacological inhibition of CatC provides an effective measure to reduce PR3m and therefore has implications as a novel therapeutic approach in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. We first studied neutrophilic PR3 from 24 patients with Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome (PLS), a genetic form of CatC deficiency. PLS neutrophil lysates showed a largely reduced but still detectable (0.5–4%) PR3 activity when compared with healthy control cells. Despite extremely low levels of cellular PR3, the amount of constitutive PR3m expressed on the surface of quiescent neutrophils and the typical bimodal membrane distribution pattern were similar to what was observed in healthy neutrophils. However, following cell activation, there was no significant increase in the total amount of PR3m on PLS neutrophils, whereas the total amount of PR3m on healthy neutrophils was significantly increased. We then explored the effect of pharmacological CatC inhibition on PR3 stability in normal neutrophils using a potent cell-permeable CatC inhibitor and a CD34+ hematopoietic stem cell model. Human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells were treated with the inhibitor during neutrophil differentiation over 10 days. We observed strong reductions in PR3m, cellular PR3 protein, and proteolytic PR3 activity, whereas neutrophil differentiation was not compromised.

Keywords: protease, protease inhibitor, neutrophil, aminopeptidase, antigen, autoimmune disease, genetic disease, proteinase 3, cathepsin C, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome

Introduction

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA)3 is a systemic small-vessel vasculitis most commonly affecting the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys (1, 2). The main target autoantigen in GPA is the neutrophil serine protease (NSP) proteinase 3 (PR3) (EC 3.4.21.76) (3, 4). GPA patients develop anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies to PR3 (PR3-ANCA) that bind to membrane-bound PR3 (PR3m) on the neutrophil surface (5, 6). The membrane exposure of PR3 is mediated by a hydrophobic patch at the protease surface, which is not conserved in other related NSPs, such as human neutrophil elastase (HNE), cathepsin G (CG) and neutrophil serine protease 4 NSP-4 (7–9). PR3m on purified neutrophils shows a bimodal pattern that is typical for 97% of all individuals. This bimodal PR3m is caused by subset-restricted epigenetically regulated expression of the neutrophil-specific PR3 receptor CD177 (10). As a consequence, two distinct neutrophil subsets exist, namely CD177(neg)/PR3m(low) and CD177(pos)/PR3m(high) cells. Binding of PR3-ANCA to PR3m on cytokine-primed neutrophils induces cell activation, resulting in the liberation of microvesicles bearing the PR3 autoantigen at their surface (11, 12), the production of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and the release of granular proteins and reactive oxygen species (13, 14). Secreted active proteases, including PR3 and related NSPs, exert proteolytic activity on endothelial cells, thereby contributing to vascular necrosis (5, 15). Secreted NETs also trap PR3 and related NSPs and are directly implicated in ANCA induction as well as endothelial damage (16). PR3m disseminated at the membrane of released microvesicles following immune activation of neutrophils is suspected to promote systemic inflammation like that observed in GPA (11, 12). There is no treatment for GPA that is based on disease-specific mechanisms, and the current protocols involve combined administration of steroids with either cyclophosphamide or rituximab (17, 18). These standard treatments are associated with toxicity, highlighting the need to develop novel, more specific therapeutic strategies (19).

Cathepsin C (CatC) (EC 3.4.14.1), also known as dipeptidyl peptidase I, is a lysosomal amino peptidase belonging to the papain superfamily of cysteine peptidases (20, 21). CatC catalyzes the cleavage of two residues from the N termini of peptides and proteins. CatC, which is ubiquitously expressed in mammals, is considered to be a major intracellular processing enzyme. High concentrations of CatC are detected in immune defense cells, including neutrophils, mast cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages. CatC is the physiological activator of several immune cell-associated serine proteases, such as NSPs (22, 23). NSPs are synthesized as inactive zymogens containing a dipropeptide in the myeloblast/promyelocyte stage in the bone marrow (8, 24). The pro-forms mature in this very early developmental stage, induced by CatC, through the cleavage of the N-terminal dipropeptide. The cleavage of the dipropeptide by CatC results in a reorientation and remodeling of three surface loops within the activation domain of the protein and renders the S1 pocket of the active site accessible to substrates (25). After processing, the active proteases are stored in cytoplasmic granules.

CatC is synthesized as a 60-kDa single chain pro-form containing an exclusion domain, a propeptide, a heavy chain, and a light chain (26). Pro-CatC which is a dimer, can be efficiently activated by proteolysis with CatL and -S in vitro (26). The initial cleavages liberate the propeptide from the catalytic region. Subsequently, a further cleavage occurs between the heavy chain and the light chain, which form a papain-like structure (26, 27). X-ray images of mature CatC structures revealed that the exclusion domain, the heavy chain, and the light chain are held together by noncovalent interactions (20). Mature CatC is a tetramer formed by four identical monomers with their active site clefts fully solvent-exposed. The presence of the exclusion domain blocks the active site beyond the S2 pocket, and it is responsible for the diaminopeptidase activity of CatC (20, 28).

Loss-of-function mutations in the CatC gene (CTSC) result in Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome (PLS) (OMIM: 245000) (29, 30), a rare autosomal recessive disease affecting 1–4 persons per million (31, 32). PLS involves an aggressive prepubertal periodontitis, leading to complete tooth loss in adolescence and palmoplantar keratoderma. More than 75 mutations have been identified in PLS, with missense and nonsense mutations being the most frequent, but small deletions, insertions, and splice site mutations have also been reported (33). The presumptive diagnosis of PLS can be made by clinical signs and symptoms, but confirmation requires CTSC sequencing. Analysis of urinary CatC in suspected patients can also be used as an early, simple, and easy diagnostic test (34). Roberts et al. (35) demonstrated a variety of neutrophil defects in PLS patients, arising downstream of the failure to activate NSPs by CatC. These functional defects included failure to produce NETs, reduced chemotaxis, and exaggerated cytokine and reactive oxygen species release. Pham et al. (23) also studied neutrophils from PLS patients and observed that the loss of CatC activity was associated with strong reduction in the proteolytic activity of NSPs. In addition, only very low protein amounts of PR3 and related NSPs were detected in PLS neutrophils (36–38). Thus, it is conceivable that mimicking the genetic situation in PLS neutrophils by pharmacological CatC inhibition in bone marrow precursor cells would provide an attractive therapeutic strategy in GPA to eliminate major PR3-related disease mechanisms, including the PR3-ANCA autoantigen itself. However, the effect of CatC inactivation on PR3 that is presented on the neutrophil surface where it becomes accessible to anti-PR3 antibodies is not known.

In this work, we investigated the consequences of CatC inactivation on membrane exposure of PR3. First, we quantified the residual proteolytic activity of CatC and PR3 in white blood cell (WBC) lysates or isolated neutrophils from PLS patients. Second, we studied the membrane exposure of PR3 on PLS neutrophils. Finally, we used a potent synthetic cell-permeable nitrile inhibitor to evaluate the effect of pharmacological CatC inhibition on membrane PR3 exposure in normal neutrophils generated from human CD34+ progenitor cells.

Results

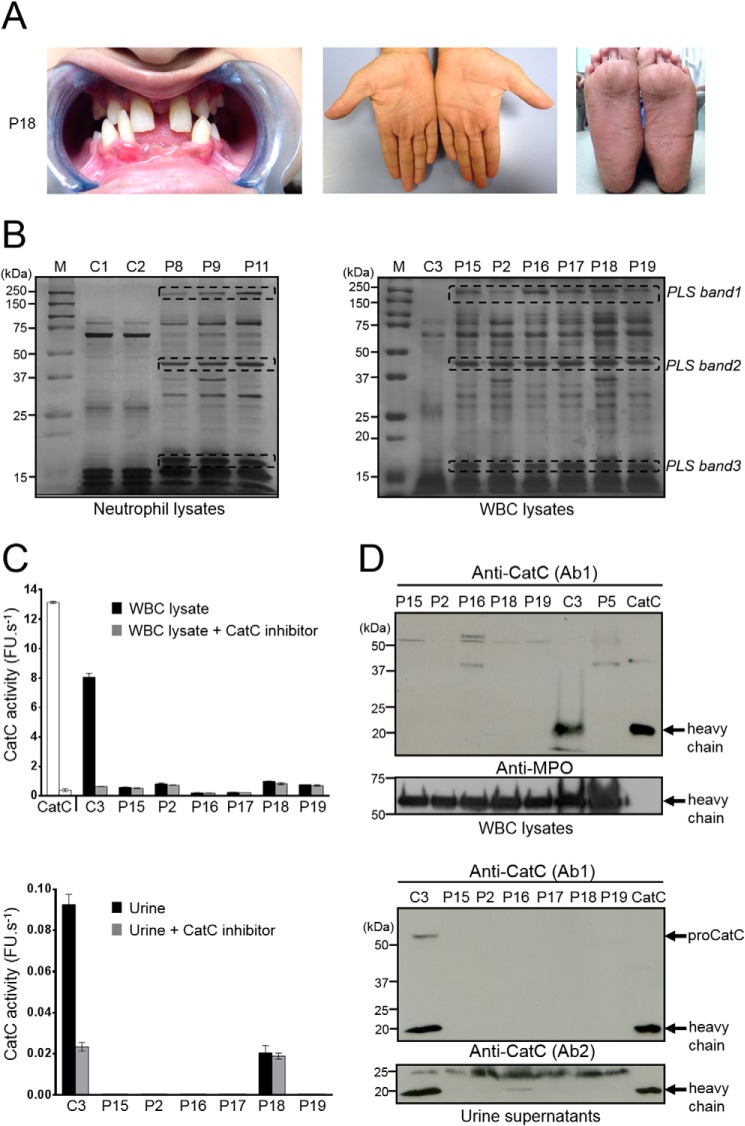

CatC in blood cells from PLS patients

Blood samples were collected from 15 PLS patients from European, Asian, and African countries. PLS diagnosis was firmly established by genetic testing. These patients carried either premature stop codon, missense, nonsense, or frameshift mutations in their CTSC (Table 1). Blood from nine additional patients with clinically suspected PLS was obtained. These patients showed typical symptoms of early-onset periodontitis and hyperkeratosis (Fig. 1A). WBC lysates from these patients and from healthy controls differed by their protein profile, as observed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

Patient information

Patients 10 and 11 are siblings, patients 13 and 14 are siblings, patients 16 and 17 are siblings, patients 22 and 23 are siblings, and patients 2 and 15 are cousins. F, female; M, male.

| Patient number | Age | Gender | Ethnicity (country of origin) | CatC mutation | CatC activity | PR3 activity (% of healthy controls) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| years | % | |||||

| 1 | 18 | M | Indian (India) | c.912C>A (p.Y304X)a nonsense | NDb | 4.3c |

| 2 | 8 | F | Egyptian (Egypte) | c.711G>A (p.W237X)d nonsense | ND | 3.9c |

| 3 | 8 | F | Turkish (France) | c.628C>T (p.Arg210X)e | ND | 1.8c |

| c.1286G>A (p.Trp429X) | ||||||

| Compound heterozygous nonsense | ||||||

| 4 | 44 | F | Italian (Italy) | c.1141delC (p.L381fsX393)f frameshift | ND | 1.8c |

| 5 | 20 | M | Saudi Arabian (Saudi Arabia) | c.815G>C (p.R272P)g missense | ND | 2.1c |

| 6 | 27 | M | Saudi Arabian (Saudi Arabia) | c.815G>C (p.R272P)g missense | ND | Not tested |

| 7 | 5 | M | Pakistani (UK) | c.815G>C (p.R272P)h missense | ND | 0.75i |

| 8 | 4 | M | Pakistani (UK) | c.815G>C (p.R272P)h missense | ND | 1.8i |

| 9 | 16 | M | Pakistani (UK) | c.815G>C (p.R272P)h missense | ND | 0.63i |

| 10 | 11 | M | Pakistani (UK) | c.815G>C (p.R272P)h missense | ND | 0.50i |

| 11 | 16 | F | Pakistani (UK) | c.815G>C (p.R272P)h missense | ND | 0.58i |

| 12 | 14 | M | British caucasian (UK) | c.415G>A (p.G139R)h | ND | 0.50i |

| c.1280A>C (p.N427T) | ||||||

| Compound heterozygous missense | ||||||

| 13 | 17 | F | Moroccan (France) | c.757G>A (p.A253I)j missense | ND | 1.7c |

| 14 | 11 | M | Moroccan (France) | c.757G>A (p.A253I)j missense | ND | 2.0c |

| 15 | 13 | F | Egyptian (Egypt) | Not identified | ND | 1.1c |

| 16 | 7 | M | Nubiank (Egypt) | c.1015C>T (p.R339C)j missense | ND | 0.8c |

| 17 | 3 | F | Nubian (Egypt) | c.1015C>T (p.R339C) suspected | ND | 0.9c |

| 18 | 12 | M | Egyptian (Egypt) | Not identified | ND | 1.3c |

| 19 | 8 | M | Egyptian (Egypt) | A splice site mutation in intron 3 IVS3-1G→Aj | ND | 1.5c |

| 20 | 17 | M | Egyptian (Egypt) | Not identified | ND | 2.1c |

| 21 | 13 | M | Egyptian (Egypt) | Not identified | ND | 2.5c |

| 22 | 16 | M | Eritrean (Germany) | c.755A>T (p.Q252L)l missense | ND | 1.7c |

| 23 | 18 | M | Eritrean (Germany) | c.755A>T (p.Q252L)l missense | ND | 3.5c |

| 24 | 23 | M | Moroccan (Germany) | c.854C>T (p.P285L)m missense | ND | 4.1c |

a Ragunatha et al. (56).

b Not detected.

c WBC lysates.

d Soliman et al. (57).

e Martinho et al. (58).

f Bullón et al. (59).

g Hamon et al. (34).

h Identified by Professor N. S Thakker, Academic Unit of Medical Genetics, University of Manchester (Manchester, UK).

i Purified neutrophil lysates.

j CatC mutations identified in this work. The mutations carried by patients 13 and 14 were determined as in Hamon et al. (34).

k The Nubian ethnicity people are also North African (residing in upper Egypt at the borders with Sudan), but they have characteristic features of dark skin and African facial features.

l Schacher et al. (60).

m Noack et al. (61).

Figure 1.

CatC in biological samples of PLS patients. A, characteristic dental and palmoplantar features of PLS (patient 18, P18). Photos show early loss of teeth and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. B, neutrophil and WBC lysates from PLS patients and from healthy controls, lysed in 50 mm HEPES buffer, 750 mm NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4, during 5 min at room temperature and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12%)/silver staining under reducing conditions (10 μg/lane) strongly differ by their protein profile. Lane M shows protein molecular weight size markers. PLS bands 1, 2, and 3 correspond to proteins that are not cleaved by NSPs in PLS WBC lysates but are hydrolyzed in WBC lysates from healthy controls. Similar results were found in three independent experiments. C, measurement of CatC activity in WBC lysates (10 μg of protein) (top) and concentrated urines (bottom) in the presence or not of a selective CatC inhibitor. The residual proteolytic activity was not inhibited by the CatC inhibitor, which demonstrates the absence of CatC activity in PLS samples. Bars, mean ± S.D. (error bars) of experiments performed in triplicates. D, Western blot analysis of WBC lysates (10 μg of protein) and concentrated urines of PLS samples and controls using anti-CatC antibodies shows the absence of the CatC heavy chain in all PLS samples. The urines were collected and analyzed as in Hamon et al. (34). Similar results were found in three independent experiments. C, control; P, PLS patient; FU, fluorescence units.

CatC activity was assayed in peripheral WBC lysates or in purified neutrophils of PLS patients and controls using a CatC-selective FRET substrate in the presence or absence of the selective nitrile CatC inhibitor (L)-Thi-(L)-Phe-CN. We did not detect any CatC activity in samples from genetically and clinically diagnosed PLS patients (Table 1, Fig. 1C, and Fig. S1), nor any CatC protein in cell lysates using a specific anti-CatC antibody (Ab) (Fig. 1D), whereas strong CatC activity was observed in control cells and was completely abrogated by the specific CatC inhibitor. Also, no CatC activity and no CatC antigen were detected in the urine of all seven PLS patients, unlike healthy controls, as described previously (34) (Fig. 1, C and D), which confirms the total CatC deficiency in these PLS patients. We then used these PLS samples to investigate the putative presence and activity of PR3, a neutrophilic serine protease thought to be matured by CatC.

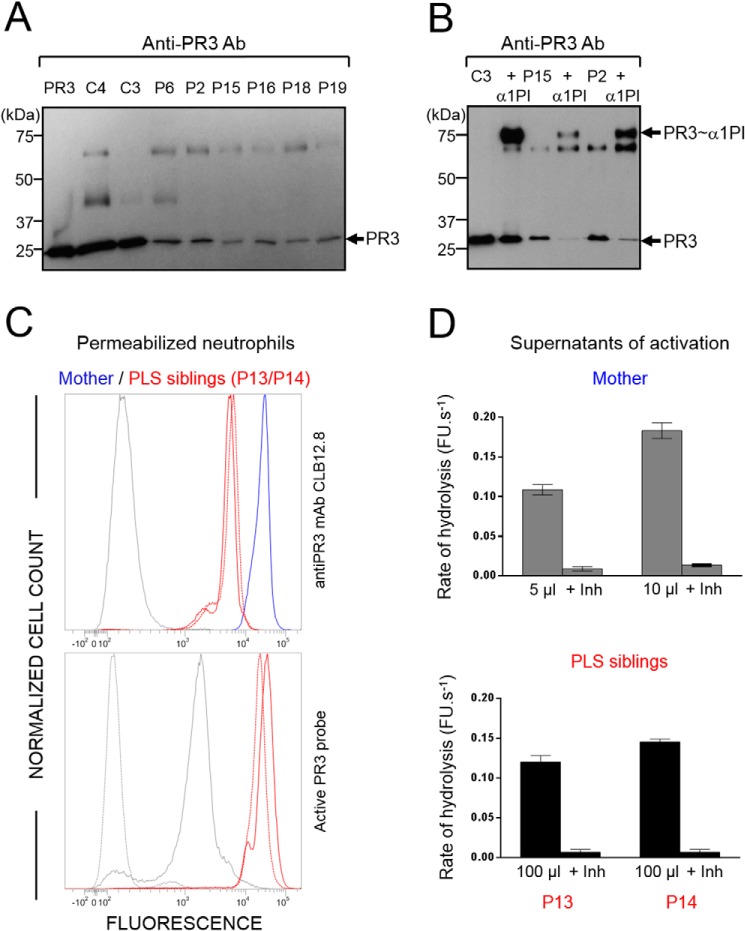

Proteolytically active PR3 in blood cells from PLS patients

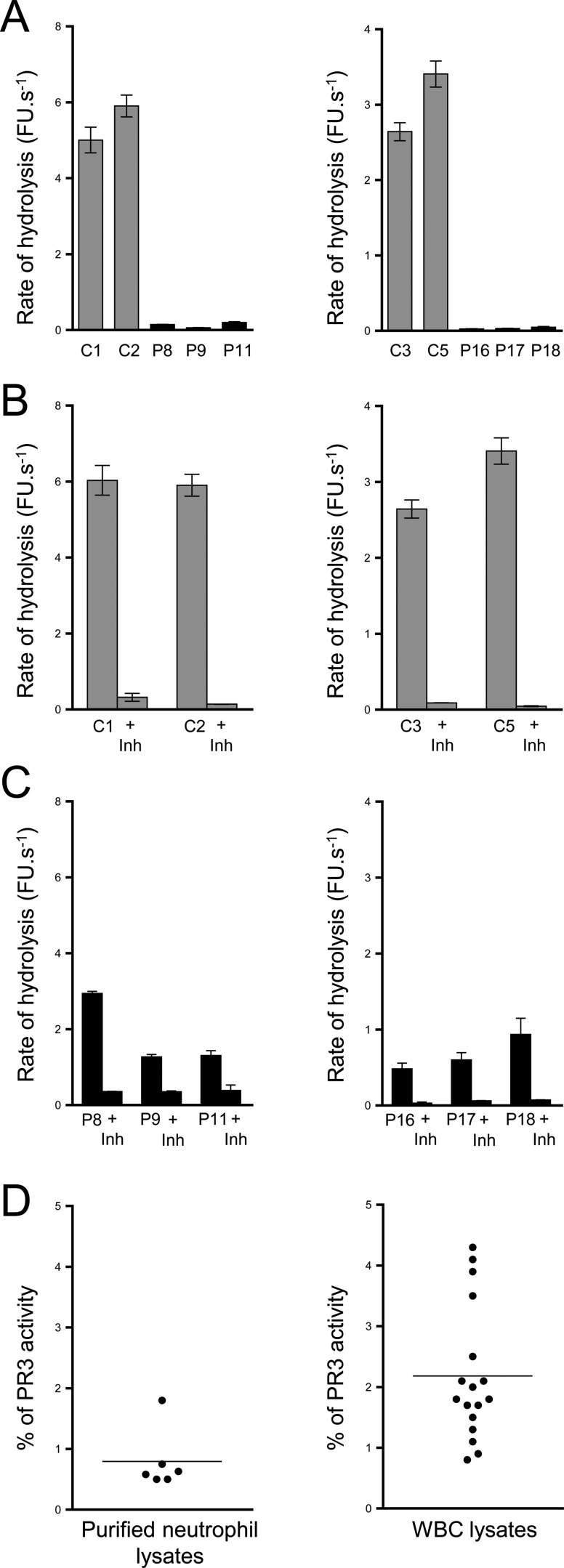

Western blot analysis of WBC or neutrophil lysates from PLS patients showed that low amounts of the PR3 antigen were present in all PLS samples (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2A). We showed that this PR3 antigen was enzymatically active by incubating PLS samples with purified exogenous α1-proteinase inhibitor (α1PI) (39) and observing the appearance of an irreversible ∼75-kDa PR3–inhibitor complex, the formation of which requires the presence of a proteolytically active PR3 (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2). We confirmed the presence of proteolytically active PR3 in permeabilized PLS neutrophils using an activity-based biotinylated probe (Bt-PEG66-PYDAP(O-C6H4-4-Cl)2) selective for PR3 that revealed the formation of irreversible complexes once reacted with a fluorescent streptavidin derivative (Fig. 2C). We also measured PR3 activity in supernatants of PLS and control cells activated with the A23187 calcium ionophore using the PR3-selective substrate ABZ-VAD(nor)VADYQ-EDDnp (Fig. 2D). Enzymatic activity in PLS cell supernatants was about one-twentieth of that in control cells and was almost totally abrogated by the PR3-specific inhibitor Bt-PYDAP(O-C6H4-4-Cl)2 (Fig. 3, A, B, and C). From these results, we estimated that blood cells of PLS patients contained 0.5–4% of the PR3 activity present in healthy control cells (Fig. 3D and Table 1). Marginal, but still detectable, activity of CG was also observed in some PLS samples using the appropriate selective FRET substrate (Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

Active PR3 in PLS blood samples. A, Western blotting of WBC lysates (10 μg of protein) from PLS patients and healthy controls using anti-PR3 antibodies: low amounts of PR3 are present in PLS samples. PR3 antigen was 3–10% of the healthy controls as determined by quantifying protein bands from Western blotting films. B, Western blotting of WBC lysates (10 μg of protein) from PLS patients and a healthy control incubated with α1PI (5 μm) in 50 mm HEPES buffer, 750 mm NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4, for 3 h at 37 °C. The de novo formation of irreversible α1PI–PR3 complexes of about 75 kDa reveals that PR3 is proteolytically active despite the absence of active CatC. C, top, flow cytometry analysis of the expression of PR3 in permeabilized PLS neutrophils. Using anti-PR3 antibodies, a lesser fluorescence is observed in permeabilized neutrophils from two PLS siblings (P13 and P14) (red) as compared with their mother used here as a control (blue). The gray peak corresponds to the isotype control. Bottom, the use of PR3 activity probe Biotin-PEG66-PYDAP(O-C6H4-4-Cl)2 as in Guarino et al. (50) shows that the residual PLS PR3 is enzymatically active. The gray peak indicates the fluorescence of permeabilized neutrophils incubated with streptavidin-Alexa Fluor® 488. The dotted gray peak corresponds to the (auto)fluorescence of permeabilized neutrophils. D, PR3 activity in supernatants of calcium ionophore A23187 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Quentin Fallavier, France)–activated WBC in the presence or absence of the specific PR3 inhibitor Ac-PYDAP(O-C6H4-4-Cl)2. PR3 activity in PLS cell supernatants is about one-twentieth of that in control cells and is almost totally inhibited in the presence of the selective PR3 inhibitor. Bars, mean ± S.D. (error bars) of experiments performed in duplicates. Similar results were found in three independent experiments. C, control; Inh, inhibitor; P, PLS patient; FU, fluorescence units.

Figure 3.

PR3 activity in PLS blood samples. PR3 activities in purified neutrophil (A, left) or in WBC lysates (A, right). PR3 activities were measured with the selective substrate ABZ-VAD(nor)VADYQ-EDDnp. Samples were also incubated with the selective PR3 inhibitor Ac-PYDAP(O-C6H4-4-Cl)2 to distinguish PR3 activity and nonspecific signal (B and C). Low levels of active PR3 were found in PLS cell lysates (5 μg) compared with control cell lysates (0.25 μg). D, percentage of PR3 activity in neutrophils and whole-blood samples. We calculated the percentage of PR3 activity in purified neutrophils and in WBC of PLS patients (n = 23) compared with healthy controls cells (n = 11). We estimated that PLS cells contained 0.5–4% of PR3 activities compared with healthy cells. Bars, mean ± S.D. (error bars) of experiments performed in triplicates. Similar results were found in three independent experiments. C, control; Inh, inhibitor; P, PLS patient; FU, fluorescence units.

Because PR3 may be constitutively present at the surface of quiescent neutrophils and its membrane exposure depends on the activation status, we studied the fate of PR3 at the surface of PLS neutrophils.

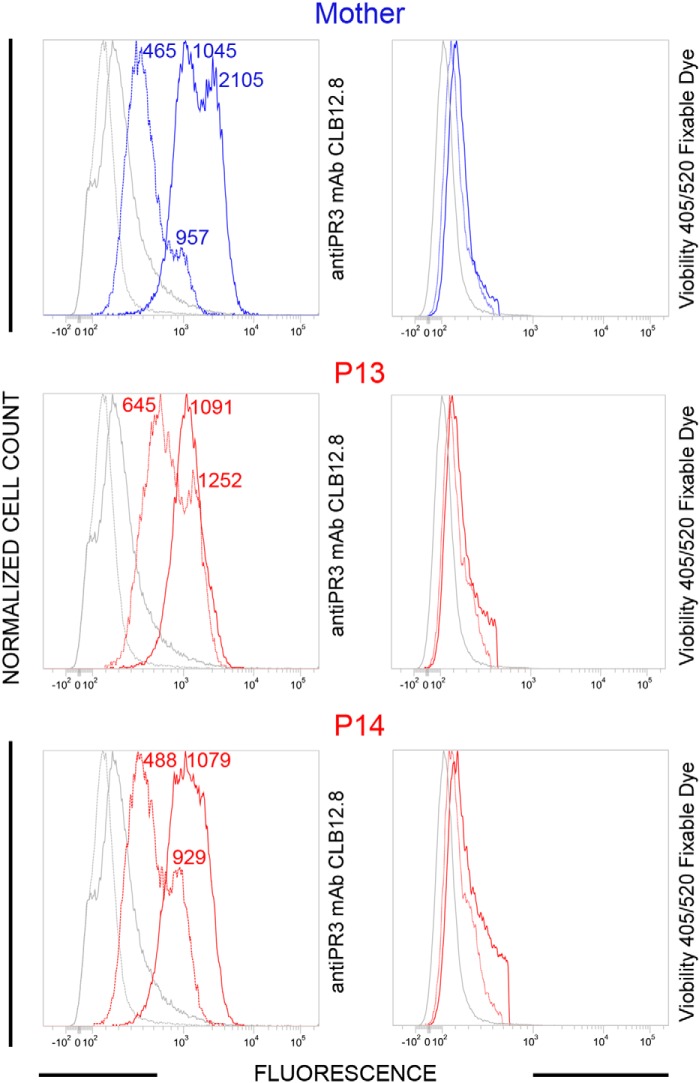

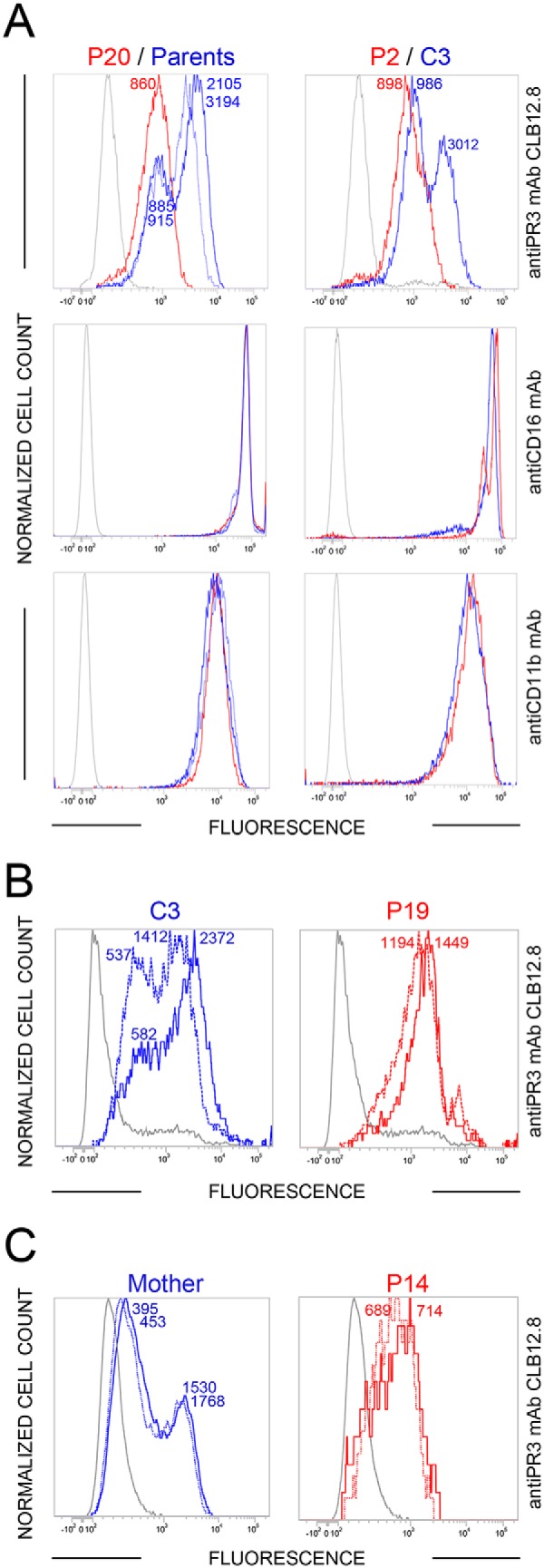

PR3 at the membrane surface of PLS neutrophils

Neutrophils from two local PLS patients (P13 and P14) and from their healthy mother were analyzed by flow cytometry using anti-PR3 monoclonal antibodies CLB12.8. Analyses were performed 30 min after blood collection (quiescent neutrophils) and after cells were activated by a calcium ionophore (A23187). Constitutive PR3m was present in significant amounts on quiescent PLS and control neutrophils with the typical bimodal pattern. After cell activation with a calcium ionophore (A23187), we observed a significant increase of the total PR3 amount at the surface of control cells but not at the surface of PLS cells. The bimodal pattern of the latter, however, had totally disappeared to give rise to a single homogeneous PR3 population, whereas it remained bimodally at the surface of control cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Flow cytometry analysis of the membrane exposure of PR3 on quiescent and chemically activated PLS neutrophils. WBC from PLS siblings (local patients P13 and P14) and their mother were activated using A23187, 30 min after blood collection. Both viable quiescent PLS cells (red dotted line) and control cells (blue dotted line) express PR3 on their surface. After chemical activation (continuous lines), membrane PR3 was largely increased on control cells, whereas PR3 on PLS neutrophils did not increase significantly but obeyed a monomodal distribution after activation. We used Viobility 405/520 fixable dye to discriminate between live and apoptotic/dead cells. Flow cytometry revealed 81 ± 5% viable neutrophils in all samples. No statistically significant difference between quiescent and activated neutrophils was observed (t test). P, PLS patient. Numbers indicate mean fluorescence intensity values.

We then used PLS blood samples from various foreign countries that were available only after a 24–72-h transit following their collection. Blood samples from either the parents or healthy individuals of the patient's country of origin were collected and shipped at the same time to serve as controls. A single PR3m-presenting neutrophil population was observed in all 12 PLS samples that we had received (Fig. 5A and Fig. S4), whereas the bimodal pattern remained in controls. Further, the total PR3 exposure was by far larger at the surface of controls than that of PLS patients. After the shipping period, most probably WBC were spontaneously activated before they were analyzed. Treating foreign PLS neutrophils with the calcium ionophore resulted in no significant increase of the total amount of PR3 at the cell surface, indicating that the cells were already activated (Fig. 5B and Fig. S5). The same result was obtained using local PLS cells after they were gently shaken for 48 h at room temperature and then treated with the calcium ionophore (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Flow cytometry analysis of the membrane exposure of PR3 on transported PLS (P) and control (C) neutrophils before and after activation. A and B, the unimodal distribution of PR3 at the surface of PLS cells (continuous red line, n = 14 PLS patients) (A) and the absence of further significant PR3 exposure following A23187 treatment (continuous line) (B) indicate that the cells were spontaneously activated or at least primed before they were analyzed (n = 4 PLS patients). C, the same result was obtained using a local PLS sample (P14) stored for 48 h at room temperature before (dotted line) and after (continuous line) ionophore treatment. Cell surface markers CD11b and CD16 were used as quantitative controls. It is noteworthy that the flow cytometry analyses of samples collected from the same individuals 9 months apart are almost fully superimposable (Fig. 5 (B and C) versus Fig. 4 and Fig. S5).

We conclude from these experiments that the absence of CatC in PLS patients does not significantly affect the constitutive PR3m at the surface of quiescent neutrophils but largely impairs the PR3 antigen exposure on the neutrophil surface of activated cells, most probably because of the lack of PR3 within the intracellular granules, which are mobilized after cell activation. Next, we assessed whether an early treatment of neutrophil precursor cells by a CatC inhibitor could reproduce what we observed in PLS samples in terms of PR3m expression, cellular PR3 amount, and PR3 proteolytic activity.

Membrane surface expression of PR3 on neutrophils generated from human CD34+ progenitor cells in the presence of a CatC inhibitor

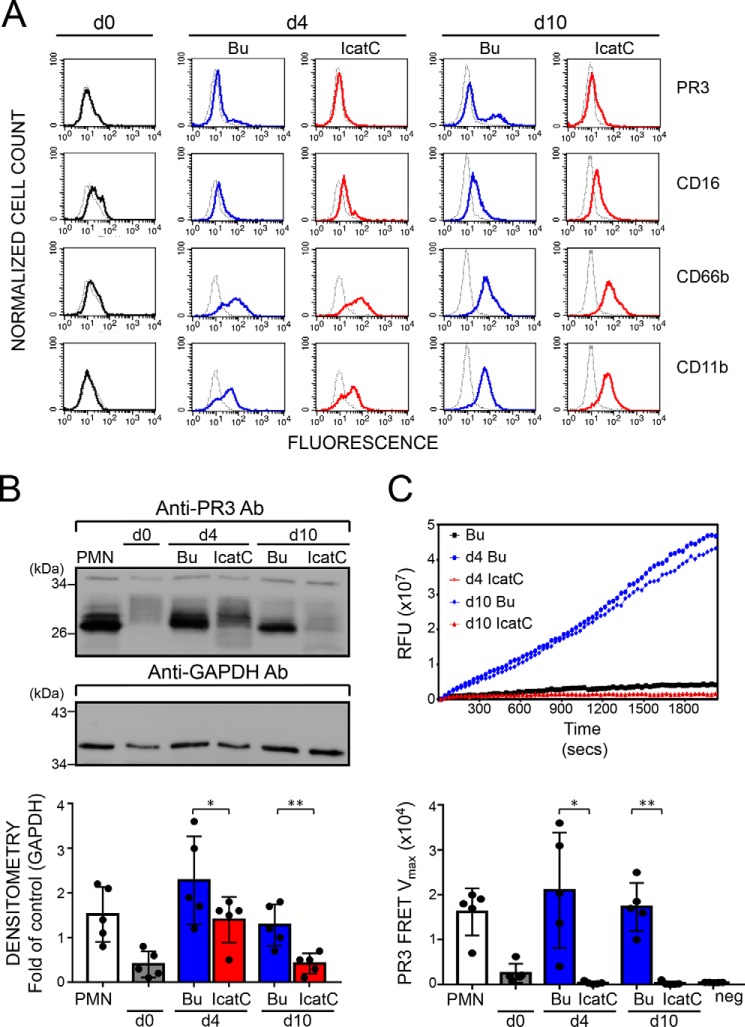

We differentiated human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) isolated from umbilical cord blood into neutrophils in the presence or absence of a potent cell-permeable cyclopropyl nitrile CatC inhibitor (IcatC) (36). Neutrophil differentiation was assessed by looking at the expression of the neutrophil surface markers CD16, CD66b, and CD11b by flow cytometry for 10 days (Fig. 6A). At day 10, a typical bimodal PR3m expression pattern was observed at the surface of control cells with a PR3m-positive neutrophil subset of 30–40%. The differentiation of IcatC-treated cells into neutrophils was not affected after 10 days, but PR3 exposure was greatly reduced, and no bimodal PR3m distribution was observed (Fig. 6A). The mean fluorescence intensity values for PR3m was reduced by 83 ± 5% (mean of five independent analyses) by IcatC at day 10 (p < 0.01) so that only marginal amounts of PR3 remained at the surface. The analysis by immunoblotting of cell lysates of differentiated neutrophils confirmed the strong reduction of the amount of PR3 antigen after treatment with the CatC inhibitor (Fig. 6B). Further, PR3 in cell lysates (n = 5) was totally inactive, as no hydrolysis of the sensitive and selective ABZ-ABZ-VAD(nor)VADYQ-EDDnp FRET substrate could be detected (Fig. 6C). Thus, inhibition of CatC in progenitor cells reduces both cellular and membrane PR3. This PR3 reduction was even stronger than that observed in neutrophils from PLS patients with genetic CatC deficiency.

Figure 6.

Effect of pharmacological CatC inhibition on PR3 expression and proteolytic activity in neutrophil-differentiated CD34+ HSC. CD34+ HSC were differentiated over 10 days into neutrophils in the presence of DMSO buffer control (Bu, blue) or a 1 μm concentration of the CatC inhibitor (IcatC, red). A, flow cytometry indicates that differentiating cells acquired the typical neutrophil surface markers CD16, CD66b, and CD11b, together with a bimodal membrane PR3 phenotype. Color lines, staining with the specific antibodies; dotted lines, the corresponding isotype control. A representative of five independent differentiation experiments is shown. B, PR3 protein was assessed in cell lysates (7.0 μg/lane) by immunoblotting at the indicated time points using a specific anti-PR3 antibody. PR3 protein was strongly induced during CD34+ HSC differentiation, and this effect was significantly reduced with IcatC. A representative Western blot and the densitometric analysis from five independent differentiation experiments are shown. Bars, mean ± S.D. (error bars) of each condition; asterisks, p value of t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). C, proteolytic PR3 activity was assessed in cell lysates (2.5 μg of protein) at the indicated time points, using the PR3-specific FRET substrate ABZ-VAD(nor)VADYQ-EDDnp. Representative PR3 substrate conversion curves from one of five independent differentiation experiments are depicted together with the corresponding statistics for the mean Vmax values ± S.D. (n = 5 independent differentiation experiments). The data show a complete loss of proteolytic PR3 activity with CatC inhibition. Isolated normal blood neutrophils (PMN) served as a positive control, and an endothelial cell line served as a negative control (neg ctrl). Asterisks, p value of t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Discussion

Neutrophils are key actors in the pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis (6). Induction of ANCA production would result from neutrophil activation leading to the formation of NETs. These trap secreted PR3, which is then presented to dendritic cells, triggering the production of PR3-ANCA by B-cells (6, 14). The important role of PR3 as the main target antigen in GPA and related vasculitis is explained by the fact that PR3 is the only NSP constitutively presented on the surface of circulating blood neutrophils and that it remains partly bound to the neutrophil surface following cell activation. Interaction of circulating PR3-ANCA with PR3m initiates the activation of circulating neutrophils and thus triggers necrotizing inflammation (6). Because neutrophils from PLS patients that lack CatC activity do not produce NETs (35, 38) and contain only marginal levels of NSPs (23, 37), it is reasonable to assume that blocking NETosis and/or eliminating PR3 by interfering with CatC activity pharmacologically would ultimately reduce vascular inflammation. Thus, in vivo inhibition of CatC by a synthetic cell-permeable inhibitor that mimics the conditions observed in PLS patients could have therapeutic potential by reducing PR3-ANCA production, neutrophil activation, endothelial cell necrosis, and inflammation. We have compared here the effects of genetic and pharmacological CatC inactivation on the fate of soluble PR3 and PR3m.

We used 24 PLS white blood cell lysates, 20 with established missense, frameshift, or nonsense mutations, to investigate the fate of cellular and membrane PR3. None contained CatC activity or immunoreactive CatC protein, irrespective of the underlying CatC mutations. This may be surprising for those with a missense mutation, but our observation corroborates a previous report from the literature (38) and gives support to the conclusion that missense mutations in the CTSC gene abrogate the constitutive secretion of CatC and trigger its degradation in intra- or extracellular compartments. Because of the altered NSP activity in PLS lysates, SDS-PAGE analysis showed a characteristic protein profile that differed significantly from that of healthy controls. This finding may represent a useful diagnostic fingerprint for PLS as we previously showed for a misdiagnosed PLS patient (34) whose cell lysate did not present the typical cleavage pattern. We used here this analysis as an additional control to document the CatC deficiency in all patients. This easy-to-manage analysis may be clinically helpful when genetic testing and mutation analysis are not easily available.

The loss of CatC activity in PLS patients was associated with a severe reduction in the activity and the amounts of NSPs (23, 36–38). We also found that PR3 activity in PLS WBC lysates was strongly lowered to 1–4% of that in control lysates but was still detectable. We employed several approaches to ensure that the measured proteolytic activity was indeed due to PR3. We used a highly sensitive and specific PR3 substrate, a specific PR3 inhibitor that totally abrogated the enzymatic activity, and finally, a selective PR3 activity–based probe to detect active PR3 in PLS neutrophils. The results clearly confirmed the presence of a residual PR3 activity in PLS neutrophils, suggesting that CatC is the main, but not the sole, protease involved in the activation of pro-NSPs. This observation is consistent with data from Roberts et al. (35), who demonstrated the presence of low amounts of LL37, a product of PR3 cleavage of human cathelicidin 18, in stimulated neutrophil supernatants from PLS patients.

We then investigated whether or not the unprocessed pro-PR3 was still present in PLS cell lysates. For this purpose, we exploited the property of α1PI to form irreversible complexes with proteolytically active PR3 but not with its pro-form. Following incubation of PLS cell lysates with α1PI, almost all immunoreactive PR3 formed irreversible complexes with the inhibitor, suggesting that only residual mature PR3 was present in cell lysates. Having ensured that the absence of the pro-PR3 was not due to the cell lysis procedure, we conclude that most of pro-PR3 was degraded very early in PLS neutrophil precursors. Our data support the idea that a small amount of pro-PR3 can be processed early into an active protease by one or several aminopeptidase(s) other than CatC. These enzymes remain, however, to be identified.

Mature NSPs are normally stored within intracellular granules after zymogen processing following a conformational change. However, several reports describe the sorting of zymogens and of catalytically inactive proteases to intracellular storage granules (38). This holds true for pro-PR3 with a noncleavable propeptide (Ala-Glu-Pro) (40) that is sorted to granules of HMC-1 cells.4 This is also the case for trypsinogen that can also be directed toward storage granules (41). Thus, the zymogen-enzyme conformational change is not critical for granular sorting. Unprocessed HNE zymogens, however, are easily processed into low-molecular weight fragments during differentiation before disappearing completely as we previously showed using isolated human bone marrow cells from healthy donors pulse-chased in the presence of IcatC (36). Sorensen et al. (38) showed the disappearance of multiple granule proteins, not only of NSPs. CatC inhibition could activate this process at least in promyelocytes. Furthermore, Bullon et al. (42) recently reported that PLS fibroblasts accumulated autophagosomes, which results in an autophagic dysfunction. This observation could well explain the elimination of several proteins in PLS neutrophils, including NSP zymogens and mutated CatC.

Human PR3 is expressed constitutively in a bimodal manner with two populations of neutrophils presenting either high (PR3m(high)) or low (PR3m(low)) amounts of the protease on their surface (43, 44). The level of PR3m on resting neutrophils and the percentage of PR3m-expressing neutrophils is stable over time for a given individual (5, 44). Despite the low PR3 level in PLS cell lysates, we observed that PR3m was present at the surface of resting PLS neutrophils, showing a typical bimodal distribution similar to control neutrophils. This observation suggests that the expression of constitutive PR3m on resting neutrophils is independent of intracellular PR3 levels and remains stable even when CatC is inactive. Activating cells from PLS patients with the calcium ionophore A23187 resulted in a PR3 increase on the neutrophil surface, but this increase is limited by the low intracellular PR3 content and thus far smaller than that observed in control cells. Thus, the genetic inactivation of CatC results in a dramatic decrease of PR3 within intracellular granules but does not interfere with the constitutive expression of PR3 at the surface of quiescent PLS neutrophils. This suggests a different intracellular storage site and a different intracellular pathway for constitutive and induced PR3m. The direct plasma membrane insertion, distinct from the CD177 association, represents the second possible way to present PR3 on neutrophil surface, as reported previously (7, 45, 46). This probably irreversible insertion would be forced by the millimolar concentration of soluble PR3 in healthy neutrophil granules (47). This could explain the rather low amount of induced PR3m detected on activated PLS neutrophils. Unexpectedly, and in contrast to control cells, no bimodal PR3m expression pattern was observed in activated PLS cells. This observation was made in both spontaneously activated cells after shipping and with a pharmacological compound. We have no obvious explanation for this finding at the moment.

We showed previously that a two-step amplification/differentiation protocol of human CD34+ HSC obtained from umbilical cord blood results in differentiated neutrophils (48). We used this model system to investigate the production and the fate of PR3 in the presence of a CatC nitrile inhibitor, IcatC (27). A subset of PR3m-positive cells was detectable by flow cytometry at day 10, whereas a second cell subset remained negative, consistent with a bimodal expression typically seen with blood neutrophils. Differentiation of CD34+ HSC into neutrophils in the presence of the CatC inhibitor IcatC did not alter the expression of the neutrophil surface markers CD16b, CD66b, and CD11b but resulted in strong reduction of intracellular and membrane PR3. No PR3 activity was detected by FRET analysis in cell lysates, suggesting that residual PR3 antigen was pro-PR3. Pharmacological CatC inhibition using IcatC eliminated PR3 from normal neutrophils more effectively than mutated CatC in PLS neutrophils. It is conceivable that additional aminopeptidases exist in blood neutrophils that were absent in CD34+ HCS-derived neutrophils or that the potent IcatC inhibitor inhibited CatC together with an additional protease(s) involved in the activation of pro-PR3. Our current observations in PLS cells and our recent work reporting the complete disappearance of HNE in bone marrow cells from healthy donors pulse-chased in presence of the IcatC support the latter hypothesis (36). We recently observed that the inhibition by a cell-permeable inhibitor of CatS, a pro-CatC maturating protease (27), prevents the conversion of pro-CatC almost totally in an HL-60 cell line without altering PR3 activity. In contrast, supplementing the CatS inhibitor with IcatC completely blocked PR3 maturation.5 Thus, the human genome would contain at least one unknown cysteine protease that is inhibited by IcatC and is involved in the maturation of pro-PR3. However, whether this protease is also expressed in healthy neutrophilic precursors remains to be confirmed.

To conclude, we showed here that CatC is the major but not the unique pro-PR3–processing protease in neutrophils because low amounts of proteolytically active PR3 are still present in neutrophils of CatC-deficient individuals. Despite the extremely low levels of cellular PR3, the amount of constitutive PR3m exposed on the surface of quiescent neutrophils from PLS patients is similar to that observed in healthy neutrophils. Activated PLS neutrophils also expose tiny amounts of induced PR3 on their surface, proportional to the very low concentration in intracellular granules. Treating CD34+ HSC with the CatC inhibitor IcatC resulted in an almost total absence of intracellular PR3 and PR3m in stem cell–derived neutrophils without compromising neutrophil differentiation. The elimination of the PR3-ANCA target antigen supports the notion that pharmacological CatC inhibition provides an alternative therapeutic strategy for reducing neutrophil-mediated vascular inflammation in autoimmune vasculitis. We previously showed that a prolonged IcatC administration in the macaque resulted in an almost complete elimination of PR3 and NE (36). Unlike humans, however, macaques do not display constitutive PR3 at the surface of their neutrophils and therefore cannot be used as a relevant model of GPA. Only clinical studies in GPA patients will answer the question of whether or not a CatC inhibitor may function as a PR3-ANCA antigen suppressor.

Experimental procedures

Blood collection

Blood samples were collected from 24 PLS patients from European countries (Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, France, and Hungary), from Asian countries (India and Saudi Arabia), and from Egypt. The 13 healthy volunteers were from France, India, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. 2–15-ml peripheral blood samples from healthy control donors and patients with PLS were collected into EDTA K2 preservative tubes by peripheral venipuncture. Samples were taken after informed consent was obtained, and the study was conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki principles. Red blood cell lysis took place with 0.1 mm EDTA, 10 mm KHCO3, 150 mm NH4Cl, and white cells pelleted with centrifugation for 5 min at 400 × g.

Blood neutrophil purification

Neutrophils were isolated by Percoll density centrifugation, employing two discontinuous gradients of 1.079 and 1.098, and purified by erythrocyte lysis (0.83% NH4Cl containing 1% KHCO3, 0.04% EDTA, and 0.25% BSA) described previously (35). Cells were then resuspended in gPBS (PBS, 1 mm glucose) and cations (1 mm MgCl2, 1.5 mm CaCl2). Cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion (typically 98%), and cell purity was determined by cytospin.

Differentiation of CD34+ HSC from umbilical cord blood into neutrophils

Umbilical cord blood samples were taken giving informed consent. Mononuclear cells were obtained from anti-coagulated cord blood by centrifugation over a LSM1077 (PAA, Pasching, Austria) gradient at 800 × g for 20 min. Cells were washed and stained using the CD34+ progenitor isolation kit (Miltenyi, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) and sorted according to the manufacturer's instructions. CD34+ cells were cultivated in stem span serum-free medium (Cell Systems, St. Katharinen, Germany) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, 100 ng/ml stem cell factor, 20 ng/ml thrombopoietin, and 50 ng/ml FLT3-L (Peprotech, London, UK) for expansion. Neutrophil differentiation was performed in RPMI with 10% FCS, 10 ng/ml G-CSF (Peprotech), and either DMSO control or 1 μm IcatC. Medium was changed every other day. We PR3-phenotyped the neonatal neutrophils obtained from the freshly harvested umbilical cords by flow cytometry before the CD34+ HSC isolation. We selected only cord blood where the neonatal neutrophils showed a clear bimodal membrane PR3 pattern.

Measurement of protease activities in cell lysates

WBC, purified blood neutrophils, CD34+, or neutrophil-differentiated CD34+ HSC was lysed in 50 mm HEPES buffer, 750 mm NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4. Soluble fractions were separated from cell debris by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Soluble fractions were concentrated by ultrafiltration (Vivaspin (filtration threshold 10 kDa)) in some experiments. Proteins were assayed with a bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Villebon sur Yvette, France).

The CatC activity in cell lysates was measured spectrofluorometrically (Spectra Max Gemini EM) at 420 nm with or without the nitrile inhibitor (L)-Thi-(L)-Phe-CN (27) (1 μm final, 20 min incubation at 37 °C) using Thi-Ala(Mca)-Ser-Gly-Tyr(3-NO2)-NH2 (49) (20 μm final) as selective FRET substrate in 50 mm sodium acetate, 30 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 2 mm DTT, pH 5.5, at 37 °C. Mature human CatC was used as control (Unizyme Laboratories, Hørsholm, Denmark).

The PR3 activity in cell lysates was measured at 420 nm with or without the PR3 inhibitor Ac-PYDAP(O-C6H6-4-Cl)2 (50) (0.5 μm final, 20 min incubation at 37 °C) using ABZ-VAD(nor)VADYQ-EDDnp (51) (20 μm final; Genecust, Dudelange, Luxembourg) as a substrate in 50 mm HEPES buffer, 750 mm NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4, at 37 °C. The CG activity was measured at 420 nm in 50 mm HEPES buffer, 100 mm NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4, at 37 °C, in the presence or not of Bt-AAFP(O-C6H6)2 (MP Biomedicals, Illkirch, France) using ABZ-TPFSGQ-EDDnp (52) (20 μm final; Genecust) as a substrate.

Western blotting

The pellet of purified blood neutrophils and WBC were directly lysed in SDS sample buffer (25 mm Tris (pH 7), 10% glycerol, 1% SDS, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol). The pellet of CD34+ HSC or neutrophil-differentiated CD34+ HSC was lysed in sample buffer (20 mm Tris (pH 8.8), 138 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitor mix). The total protein concentration was determined by a bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or Bradford (Bio-Rad) assay.

The proteins were separated on 10% or 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing and denaturing conditions (7–50 μg of protein/lane). They were transferred to a nitrocellulose (Hybond)-enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) membrane at 4 °C. Free sites on the membranes were blocked by incubation with 5% nonfat dried milk in PBS, 0.1% Tween for 90 min at room temperature. They were washed twice with PBS, 0.1% Tween and incubated overnight with a primary antibody (murine anti-human CatC Ab directed against the heavy chain of CatC (Ab1, sc-747590) (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany (34)), goat anti-human CatC (Ab2, EB11824) directed against the propeptide (1:1000; Everest Biotech, Oxfordshire, UK (34)), rabbit anti-PR3 Ab (ab133613) (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) (27)), or rabbit anti-myeloperoxidase heavy chain (1:500; sc-16128-R, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by a specific secondary antibody (a sheep anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:10,000; A5906, Sigma-Aldrich) or a goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:10000; A9169, Sigma-Aldrich)). Membranes were washed (three times for 10 min each) with PBS, 0.1% Tween, and the detection was performed by the ECL system.

Flow cytometry

WBC from PLS patients or healthy controls were resuspended in PBS, and a blocking step was performed with 5% BSA, 2.5 mm EDTA in PBS for 15 min at 4 °C, or WBC were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, and nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% BSA. Flow cytometry analyses were performed using a MACSQuant analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) and VenturiOne software (Applied Cytometry, Sheffield, UK). These analyses were performed using the following Abs: V450-conjugated CD14 (MϕP9, 1:200), PE-conjugated CD3 (HIT3a, 1:200), PE-CyTM-conjugated CD11b (M1/70, 1:100), APC-conjugated CD16 (3G8, 1:200), APC-H7–conjugated CD45 (2D1, 1:200) (BD Biosciences, Le Pont de Claix, France), PerCP-Vio700–conjugated CD15 (VIMC6, 1:100) (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany), FITC-conjugated IgG1 (679.1Mc7, 1:20) (Dako, Hamburg, Germany), FITC-conjugated CD16 (DJ130c, 1:20) (Dako, Hamburg, Germany), FITC-conjugated CD18 (7E4, 1:20) (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany), FITC-conjugated CD66b (80H3, 1:20) (Beckman Coulter). The PR3 was labeled with the primary mouse monoclonal antibody CLB12.8 (1:50) (Sanquin, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and the secondary antibody FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (sc-2010, 1:100) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or the secondary antibody FITC-conjugated IgG1 Fab2 (DAK-GQ1, 5 μg/ml) (Dako, Hamburg, Germany). Dead cells were stained with Viobility 405/520 fixable dye (1:200) (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). The gating strategies used are described in Fig. S6. The compensation was performed using VenturiOne software.

Genetic analysis

Extraction of genomic DNA (salting out procedure)

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from the patients and both parents (if available) after informed consent had been given according to National Research Center (NRC) guidelines. Genomic DNAs were prepared as described previously (53) with some additional modifications (54).

PCR amplification of CTSC gene exons

For analysis of CTSC mutations, eight different specific amplifications using CTSC gene-specific primers were carried out on the genomic DNA according to Toomes et al. (30), except for the newly developed primer pairs for exons 1 and the 5′ half of exon 7 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primers used

| Exon number | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| Forward primers | |

| 1 | 5′-TCTTCACCTCTTTTCTCAGC-3′ |

| 2 | 5′-GACTGTGCTCAAACTGGGTAG-3′ |

| 3 | 5′-GGGGCACATTTACTGTGAATG-3′ |

| 4 | 5′-GTACCACTTTCCACTTAGGCA-3′ |

| 5 | 5′-CCTAGCTAGTCTGGTAGCTG-3′ |

| 6 | 5′-CTCTGTGAGGCTTCAGATGTC-3′ |

| 7a | 5′-CGGCTTCCTGGTAATTCTTC-3′ |

| 7b | 5′-CAATGAAGCCCTGATCAAGC-3′ |

| Reverse primers | |

| 1 | 5′-GGTCCCCGAATCCAGTCAAG-3′ |

| 2 | 5′-CTACTAATCAGAAGAGGTTTCAG-3′ |

| 3 | 5′-CGTATGTCTCATTTGTAGCAAC-3′ |

| 4 | 5′-GGAGGATGGTATTCAGCATTC-3′ |

| 5 | 5′-GTATCCCCGAAATCCATCACA-3′ |

| 6 | 5′-CAACAGCCAGCTGCACACACAG-3′ |

| 7a | 5′-GTAGTGGAGGAAGTCATCATATAC-3′ |

| 7b | 5′-CTTCTGAGATTGCTGCTGAAAG-3′ |

PCR was performed in a final volume of 25 μl containing ∼100 ng of genomic DNA, MgCl2 (1.5 mm), dNTP mixture (0.2 mm), Taq DNA polymerase (2 units/μl), and a 10 μm concentration of each primer (MWG-BIOtech, Ebersberg, Germany).

The amplification conditions were as follows: 2 min at 95 °C for one cycle, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at the annealing temperature of the primers (53 °C for exons 7a and 7b, 54.5 °C for exon 2, 55.2 °C for exons 1 and 6, 56.6 °C for exon 3, 57.2 °C for exon 4, and 58 °C for exon 5) and 1 min at 72 °C in a thermal cycler (Agilent Technologies SureCycler 8800) (55). Five-microliter aliquots of the PCR products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Mutation analysis

PCR products were purified using the QIA Quick PCR purification kit (Qiagene) followed by bidirectional sequenced using the ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator version 3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems), and the sequencing reaction products were separated on an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Alignment of sequenced results used NCBI genomic sequence NG_008365.1 and reference cDNA sequence NM_000348.3 for result interpretation.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Author contributions

B. K. supervised the work. B. K., R. K., and S. M.-A. participated in the research design. S. S., M. R. A., C. E.-G., J. H., H. N. S., U. J., K. N'G., and S. D.-C. conducted the experiments. B. K., R. K., I. L. C., S. M.-A., D. E. J., and F. Gauthier performed data analyses. A. L., C. L., B. S., P. E., N. N., M. S., C. C., M.-C. V.-M., A. A. F. A., S. R., M. I. M., F. Giampieri, M. B., H. C., G. L., J.-L. S., C. G., and J. P. contributed samples or other essential material (chemical compounds, PLS bloods/urines). B. K. and R. K. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and revision processes of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Lise Vanderlynden (INSERM U-1100) for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the “Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche,” the “Région Centre-Val de Loire” (Project BPCO-Lyse). This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement 668036 (RELENT). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the authors.

This article contains Figs. S1–S6.

U. Specks, personal communication.

S. Seren, S. Dallet-Choisy, F. Gauthier, S. Marchand-Adam, and B. Korkmaz, unpublished results.

- GPA

- granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- α1PI

- α-1-proteinase inhibitor

- Ab

- antibody

- ABZ

- ortho-aminobenzoic acid

- ANCA

- anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies

- Bt

- biotin

- CatC

- CatL, and CatS, cathepsin C, L, and S, respectively

- CG

- cathepsin G

- ECL

- enhanced chemiluminescence

- EDDnp

- N-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)ethylenediamine

- HNE

- human neutrophil elastase

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell(s)

- NSP

- neutrophil serine protease

- PLS

- Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome

- PR3

- proteinase 3

- PR3m

- membrane-bound PR3

- WBC

- white blood cell(s)

- NET

- neutrophil extracellular trap

- IcatC

- CatC inhibitor

- PE

- phycoerythrin

- APC

- allophycocyanin.

References

- 1. Millet A., Pederzoli-Ribeil M., Guillevin L., Witko-Sarsat V., and Mouthon L. (2013) Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides: is it time to split up the group? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 1273–1279 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pagnoux C. (2016) Updates in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Eur. J. Rheumatol. 3, 122–133 10.5152/eurjrheum.2015.0043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jenne D. E., Tschopp J., Lüdemann J., Utecht B., and Gross W. L. (1990) Wegener's autoantigen decoded. Nature 346, 520 10.1038/346520a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thieblemont N., Wright H. L., Edwards S. W., and Witko-Sarsat V. (2016) Human neutrophils in auto-immunity. Semin. Immunol. 28, 159–173 10.1016/j.smim.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kettritz R. (2016) Neutral serine proteases of neutrophils. Immunol. Rev. 273, 232–248 10.1111/imr.12441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schönermarck U., Csernok E., and Gross W. L. (2015) Pathogenesis of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: challenges and solutions 2014. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 30, i46–i52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Korkmaz B., Kuhl A., Bayat B., Santoso S., and Jenne D. E. (2008) A hydrophobic patch on proteinase 3, the target of autoantibodies in Wegener granulomatosis, mediates membrane binding via NB1 receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35976–35982 10.1074/jbc.M806754200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korkmaz B., Horwitz M. S., Jenne D. E., and Gauthier F. (2010) Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, and cathepsin G as therapeutic targets in human diseases. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 726–759 10.1124/pr.110.002733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Korkmaz B., Moreau T., and Gauthier F. (2008) Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3 and cathepsin G: physicochemical properties, activity and physiopathological functions. Biochimie 90, 227–242 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eulenberg-Gustavus C., Bähring S., Maass P. G., Luft F. C., and Kettritz R. (2017) Gene silencing and a novel monoallelic expression pattern in distinct CD177 neutrophil subsets. J. Exp. Med. 214, 2089–2101 10.1084/jem.20161093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hong Y., Eleftheriou D., Hussain A. A., Price-Kuehne F. E., Savage C. O., Jayne D., Little M. A., Salama A. D., Klein N. J., and Brogan P. A. (2012) Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies stimulate release of neutrophil microparticles. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 49–62 10.1681/ASN.2011030298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin K. R., Kantari-Mimoun C., Yin M., Pederzoli-Ribeil M., Angelot-Delettre F., Ceroi A., Grauffel C., Benhamou M., Reuter N., Saas P., Frachet P., Boulanger C. M., and Witko-Sarsat V. (2016) Proteinase 3 is a phosphatidylserine-binding protein that affects the production and function of microvesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 10476–10489 10.1074/jbc.M115.698639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kettritz R. (2012) How anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies activate neutrophils. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 169, 220–228 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04615.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kessenbrock K., Krumbholz M., Schönermarck U., Back W., Gross W. L., Werb Z., Gröne H. J., Brinkmann V., and Jenne D. E. (2009) Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat. Med. 15, 623–625 10.1038/nm.1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jerke U., Hernandez D. P., Beaudette P., Korkmaz B., Dittmar G., and Kettritz R. (2015) Neutrophil serine proteases exert proteolytic activity on endothelial cells. Kidney Int. 88, 764–775 10.1038/ki.2015.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schreiber A., Rousselle A., Becker J. U., von Mässenhausen A., Linkermann A., and Kettritz R. (2017) Necroptosis controls NET generation and mediates complement activation, endothelial damage, and autoimmune vasculitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E9618–E9625 10.1073/pnas.1708247114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kallenberg C. G. (2015) Pathogenesis and treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitides. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 33, S11–S14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yates M., and Watts R. (2017) ANCA-associated vasculitis. Clin. Med. 17, 60–64 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-1-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chaigne B., and Guillevin L. (2016) New therapeutic approaches for ANCA-associated vasculitides. Presse Med. 45, e171–e178 10.1016/j.lpm.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Turk D., Janjić V., Stern I., Podobnik M., Lamba D., Dahl S. W., Lauritzen C., Pedersen J., Turk V., and Turk B. (2001) Structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C): exclusion domain added to an endopeptidase framework creates the machine for activation of granular serine proteases. EMBO J. 20, 6570–6582 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Korkmaz B., Caughey G. H., Chapple I., Gauthier F., Hirschfeld J., Jenne D. E., Kettritz R., Lalmanach G., Lamort A., Lauritzen C., Legowska M., Lesner A., Marchand-Adam S., McKaig J. S., Moss C., et al. (2018) Therapeutic targeting of cathepsin C: from pathophysiology to treatment. Pharmacol. Ther. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adkison A. M., Raptis S. Z., Kelley D. G., and Pham C. T. (2002) Dipeptidyl peptidase I activates neutrophil-derived serine proteases and regulates the development of acute experimental arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 363–371 10.1172/JCI0213462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pham C. T., Ivanovich J. L., Raptis S. Z., Zehnbauer B., and Ley T. J. (2004) Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: correlating the molecular, cellular, and clinical consequences of cathepsin C/dipeptidyl peptidase I deficiency in humans. J. Immunol. 173, 7277–7281 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Korkmaz B., Lesner A., Guarino C., Wysocka M., Kellenberger C., Watier H., Specks U., Gauthier F., and Jenne D. E. (2016) Inhibitors and antibody fragments as potential anti-inflammatory therapeutics targeting neutrophil proteinase 3 in human disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 68, 603–630 10.1124/pr.115.012104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jenne D. E., and Kuhl A. (2006) Production and applications of recombinant proteinase 3, Wegener's autoantigen: problems and perspectives. Clin. Nephrol. 66, 153–159 10.5414/CNP66153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dahl S. W., Halkier T., Lauritzen C., Dolenc I., Pedersen J., Turk V., and Turk B. (2001) Human recombinant pro-dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C) can be activated by cathepsins L and S but not by autocatalytic processing. Biochemistry 40, 1671–1678 10.1021/bi001693z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamon Y., Legowska M., Hervé V., Dallet-Choisy S., Marchand-Adam S., Vanderlynden L., Demonte M., Williams R., Scott C. J., Si-Tahar M., Heuzé-Vourc'h N., Lalmanach G., Jenne D. E., Lesner A., Gauthier F., and Korkmaz B. (2016) Neutrophilic cathepsin C is maturated by a multistep proteolytic process and secreted by activated cells during inflammatory lung diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 8486–8499 10.1074/jbc.M115.707109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mølgaard A., Arnau J., Lauritzen C., Larsen S., Petersen G., and Pedersen J. (2007) The crystal structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C) in complex with the inhibitor Gly-Phe-CHN2. Biochem. J. 401, 645–650 10.1042/BJ20061389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hart T. C., Hart P. S., Bowden D. W., Michalec M. D., Callison S. A., Walker S. J., Zhang Y., and Firatli E. (1999) Mutations of the cathepsin C gene are responsible for Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 36, 881–887 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Toomes C., James J., Wood A. J., Wu C. L., McCormick D., Lench N., Hewitt C., Moynihan L., Roberts E., Woods C. G., Markham A., Wong M., Widmer R., Ghaffar K. A., Pemberton M., et al. (1999) Loss-of-function mutations in the cathepsin C gene result in periodontal disease and palmoplantar keratosis. Nat. Genet. 23, 421–424 10.1038/70525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gorlin R. J., Sedano H., and Anderson V. E. (1964) The syndrome of palmar-plantar hyperkeratosis and premature periodontal destruction of the teeth: a clinical and genetic analysis of the Papillon-Lef'evre syndrome. J. Pediatr. 65, 895–908 10.1016/S0022-3476(64)80014-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hart T. C., and Shapira L. (1994) Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. Periodontol. 2000 6, 88–100 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nagy N., Vályi P., Csoma Z., Sulák A., Tripolszki K., Farkas K., Paschali E., Papp F., Tóth L., Fábos B., Kemény L., Nagy K., and Széll M. (2014) CTSC and Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: detection of recurrent mutations in Hungarian patients, a review of published variants and database update. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2, 217–228 10.1002/mgg3.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamon Y., Legowska M., Fergelot P., Dallet-Choisy S., Newell L., Vanderlynden L., Kord Valeshabad A., Acrich K., Kord H., Charalampos T., Morice-Picard F., Surplice I., Zoidakis J., David K., Vlahou A., et al. (2016) Analysis of urinary cathepsin C for diagnosing Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. FEBS J. 283, 498–509 10.1111/febs.13605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roberts H., White P., Dias I., McKaig S., Veeramachaneni R., Thakker N., Grant M., and Chapple I. (2016) Characterization of neutrophil function in Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. J. Leukoc. Biol. 100, 433–444 10.1189/jlb.5A1015-489R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guarino C., Hamon Y., Croix C., Lamort A. S., Dallet-Choisy S., Marchand-Adam S., Lesner A., Baranek T., Viaud-Massuard M. C., Lauritzen C., Pedersen J., Heuzé-Vourc'h N., Si-Tahar M., Fsinodotratlinodot E., Jenne D. E., et al. (2017) Prolonged pharmacological inhibition of cathepsin C results in elimination of neutrophil serine proteases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 131, 52–67 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Perera N. C., Wiesmüller K. H., Larsen M. T., Schacher B., Eickholz P., Borregaard N., and Jenne D. E. (2013) NSP4 is stored in azurophil granules and released by activated neutrophils as active endoprotease with restricted specificity. J. Immunol. 191, 2700–2707 10.4049/jimmunol.1301293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sørensen O. E., Clemmensen S. N., Dahl S. L., Østergaard O., Heegaard N. H., Glenthøj A., Nielsen F. C., and Borregaard N. (2014) Papillon-Lefevre syndrome patient reveals species-dependent requirements for neutrophil defenses. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 4539–4548 10.1172/JCI76009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Korkmaz B., Poutrain P., Hazouard E., de Monte M., Attucci S., and Gauthier F. L. (2005) Competition between elastase and related proteases from human neutrophil for binding to α1-protease inhibitor. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 32, 553–559 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0374OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hinkofer L. C., Seidel S. A., Korkmaz B., Silva F., Hummel A. M., Braun D., Jenne D. E., and Specks U. (2013) A monoclonal antibody (MCPR3–7) interfering with the activity of proteinase 3 by an allosteric mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 26635–26648 10.1074/jbc.M113.495770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Greene L. J., Hirs C. H., and Palade G. E. (1963) On the protein composition of bovine pancreatic zymogen granules. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 2054–2070 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bullon P., Castejon-Vega B., Roman-Malo L., Jimenez-Guerrero M. P., Cotan D., Forbes-Hernandez T. Y., Varela-Lopez A., Perez-Pulido A. J., Giampieri F., Quiles J. L., Battino M., Sanchez-Alcazar J. A., and Cordero M. D. (2018) Autophagic dysfunction in patients with Papillon-Lefevre syndrome is restored by recombinant cathepsin C treatment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Halbwachs-Mecarelli L., Bessou G., Lesavre P., Lopez S., and Witko-Sarsat V. (1995) Bimodal distribution of proteinase 3 (PR3) surface expression reflects a constitutive heterogeneity in the polymorphonuclear neutrophil pool. FEBS Lett. 374, 29–33 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01073-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schreiber A., Busjahn A., Luft F. C., and Kettritz R. (2003) Membrane expression of proteinase 3 is genetically determined. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 68–75 10.1097/01.ASN.0000040751.83734.D1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goldmann W. H., Niles J. L., and Arnaout M. A. (1999) Interaction of purified human proteinase 3 (PR3) with reconstituted lipid bilayers. Eur. J. Biochem. 261, 155–162 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kantari C., Millet A., Gabillet J., Hajjar E., Broemstrup T., Pluta P., Reuter N., and Witko-Sarsat V. (2011) Molecular analysis of the membrane insertion domain of proteinase 3, the Wegener's autoantigen, in RBL cells: implication for its pathogenic activity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90, 941–950 10.1189/jlb.1210695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Campbell E. J., Campbell M. A., and Owen C. A. (2000) Bioactive proteinase 3 on the cell surface of human neutrophils: quantification, catalytic activity, and susceptibility to inhibition. J. Immunol. 165, 3366–3374 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schreiber A., Otto B., Ju X., Zenke M., Goebel U., Luft F. C., and Kettritz R. (2005) Membrane proteinase 3 expression in patients with Wegener's granulomatosis and in human hematopoietic stem cell-derived neutrophils. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 2216–2224 10.1681/ASN.2004070609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Łȩgowska M., Hamon Y., Wojtysiak A., Grzywa R., Sieńczyk M., Burster T., Korkmaz B., and Lesner A. (2016) Development of the first internally-quenched fluorescent substrates of human cathepsin C: the application in the enzyme detection in biological samples. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 612, 91–102 10.1016/j.abb.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guarino C., Legowska M., Epinette C., Kellenberger C., Dallet-Choisy S., Sieńczyk M., Gabant G., Cadene M., Zoidakis J., Vlahou A., Wysocka M., Marchand-Adam S., Jenne D. E., Lesner A., Gauthier F., and Korkmaz B. (2014) New selective peptidyl di(chlorophenyl) phosphonate esters for visualizing and blocking neutrophil proteinase 3 in human diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 31777–31791 10.1074/jbc.M114.591339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Korkmaz B., Hajjar E., Kalupov T., Reuter N., Brillard-Bourdet M., Moreau T., Juliano L., and Gauthier F. (2007) Influence of charge distribution at the active site surface on the substrate specificity of human neutrophil protease 3 and elastase: a kinetic and molecular modeling analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1989–1997 10.1074/jbc.M608700200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Attucci S., Korkmaz B., Juliano L., Hazouard E., Girardin C., Brillard-Bourdet M., Réhault S., Anthonioz P., and Gauthier F. (2002) Measurement of free and membrane-bound cathepsin G in human neutrophils using new sensitive fluorogenic substrates. Biochem. J. 366, 965–970 10.1042/bj20020321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Miller S. A., Dykes D. D., and Polesky H. F. (1988) A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 1215 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Essawi M., Gad Y. Z., el-Rouby O., Temtamy S. A., Sabour Y. A., and el-Awady M. K. (1997) Molecular analysis of androgen resistance syndromes in Egyptian patients. Dis. Markers 13, 99–105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Selvaraju V., Markandaya M., Prasad P. V., Sathyan P., Sethuraman G., Srivastava S. C., Thakker N., and Kumar A. (2003) Mutation analysis of the cathepsin C gene in Indian families with Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. BMC Med. Genet. 4, 5 10.1186/1471-2350-4-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ragunatha S., Ramesh M., Anupama P., Kapoor M., and Bhat M. (2015) Papillon-Lefevre syndrome with homozygous nonsense mutation of cathepsin C gene presenting with late-onset periodontitis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 32, 292–294 10.1111/pde.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Soliman H., Eldeen G. H., and Mustafa I. M. (2015) A novel nonsense mutation in cathepsin C gene in an Egyptian patient presenting with Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 16, 387–392 10.1016/j.ejmhg.2015.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Martinho S., Levade T., Fergelot P., and Stephan J. L. (2017) [Papillon-Lefevre syndrome: a new case]. Arch. Pediatr. 24, 360–362 10.1016/j.arcped.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bullón P., Morillo J. M., Thakker N., Veeramachaneni R., Quiles J. L., Ramírez-Tortosa M. C., Jaramillo R., and Battino M. (2014) Confirmation of oxidative stress and fatty acid disturbances in two further Papillon-Lefevre syndrome families with identification of a new mutation. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 28, 1049–1056 10.1111/jdv.12265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schacher B., Baron F., Ludwig B., Valesky E., Noack B., and Eickholz P. (2006) Periodontal therapy in siblings with Papillon-Lefevre syndrome and tinea capitis: a report of two cases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 33, 829–836 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00992.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Noack B., Görgens H., Schacher B., Puklo M., Eickholz P., Hoffmann T., and Schackert H. K. (2008) Functional cathepsin C mutations cause different Papillon-Lefevre syndrome phenotypes. J. Clin. Periodontol. 35, 311–316 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.