Summary

Aims

Fibromyalgia (FM), a chronic disorder defined by widespread pain, often accompanied by fatigue and sleep disturbance, affects up to one in 20 patients in primary care. Although most patients with FM are managed in primary care, diagnosis and treatment continue to present a challenge, and patients are often referred to specialists. Furthermore, the lack of a clear patient pathway often results in patients being passed from specialist to specialist, exhaustive investigations, prescription of multiple drugs to treat different symptoms, delays in diagnosis, increased disability and increased healthcare resource utilisation. We will discuss the current and evolving understanding of FM, and recommend improvements in the management and treatment of FM, highlighting the role of the primary care physician, and the place of the medical home in FM management.

Methods

We reviewed the epidemiology, pathophysiology and management of FM by searching PubMed and references from relevant articles, and selected articles on the basis of quality, relevance to the illness and importance in illustrating current management pathways and the potential for future improvements.

Results

The implementation of a framework for chronic pain management in primary care would limit unnecessary, time‐consuming, and costly tests, reduce diagnostic delay and improve patient outcomes.

Discussion

The patient‐centred medical home (PCMH), a management framework that has been successfully implemented in other chronic diseases, might improve the care of patients with FM in primary care, by bringing together a team of professionals with a range of skills and training.

Conclusion

Although there remain several barriers to overcome, implementation of a PCMH would allow patients with FM, like those with other chronic conditions, to be successfully managed in the primary care setting.

Review criteria

We reviewed the epidemiology, pathophysiology and management of fibromyalgia (FM) by searching English‐language publications in PubMed, and references from relevant articles, published before May 2015. The main search terms were fibromyalgia, epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, primary care, secondary care, treatment and patient‐centred medical home. We selected articles on the basis of quality, relevance to the illness and importance in illustrating current management pathways and the potential for future improvements.

Message for the clinic

The management pathway for FM currently is often lengthy and complex, involving repeated clinic visits, unnecessary referrals and costly tests. The medical home, a patient‐centred management framework which has been successfully implemented in other chronic diseases, might provide the key to reducing diagnosis time and improving patient outcomes. Effective approaches to helping practices adopt the medical home and tailor it to the needs of patients with FM will be important.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a common, potentially disabling, chronic disorder that is defined by widespread pain, often accompanied by fatigue and sleep disturbance, and associated with other symptoms including depression, cognitive dysfunction (e.g. forgetfulness, decreased concentration), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and headache 1, 2. In the general population, the estimated global prevalence of FM is 2.7% (4.2% female, 1.4% male) 2. In primary care, studies suggest that up to one in 20 patients has FM symptoms 3, and this number is increasing as growing recognition of FM by patients leads to an upsurge in presentation for diagnosis and treatment 4, 5. The cause of FM is not known, but research studies suggest genetic predisposition and possible triggering events 6.

Fibromyalgia continues to present a challenge for healthcare professionals (HCPs) 7. The extensive array of symptoms associated with, and gradual evolution of, FM make it difficult to diagnose in primary care settings 7, 8, and the condition is often under‐diagnosed 5. One study has shown that diagnosis of FM might take more than 2 years, with patients seeing an average of 3.7 different physicians during this time 8. Although the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has published diagnostic criteria for FM 9, 10, these are not widely used in clinical practice, and there remains a knowledge gap among some HCPs, particularly in the primary care setting 7, 8, 11, 12. In addition to diagnostic complexity, therapeutic management might be problematic 13, and there is a lack of prescribing consistency between physicians 14, 15. Many patients might not receive treatment, and for those who do, repeated therapy switching, polypharmacy and discontinuation are common 16. Some patients may also have unrealistic treatment expectations 17 and difficulty coping with their symptoms, which may contribute to struggles in managing their condition.

The aim of this review was to discuss the current and evolving understanding of FM, provide insights into the challenges around recognition and diagnosis, and recommend improvements in the management and treatment of FM. The review will highlight the role of the primary care physician, and the place of the medical home in FM management.

Methods

We reviewed the epidemiology, pathophysiology and management of FM by searching English‐language publications in PubMed, and references from relevant articles, published before May 2015. The main search terms were fibromyalgia, epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, primary care, secondary care, treatment and patient‐centred medical home. We selected articles on the basis of quality (robust data published in a peer‐reviewed journal that were able to support the conclusions drawn), relevance to the illness and importance in illustrating current management pathways and the potential for future improvements.

FM overview

Although the global prevalence of FM is estimated to be 2.7%, epidemiological studies have produced varying results across different countries and continents 2. Until recently, most studies were carried out using the 1990 ACR diagnostic criteria 1, which resulted in notable gender imbalance; using these criteria, the prevalence of FM was 3.4% in females, and 0.5% in males (a ratio of ~7 : 1) 18. This might be because the 1990 criteria required pain to be present on palpation of at least 11 of 18 tender points for a diagnosis of FM to be confirmed (Table 1) 1, and males have a higher pressure pain threshold than females 19, making them less likely to meet the 1990 FM criteria 5. A recent analysis using the updated 2010 criteria 9 that do not require a tender point assessment, has provided prevalence estimates of 7.7% in women and 4.9% in men 20, narrowing the gender gap and giving a female:male ratio of 1.6 : 1, which is more similar to that seen in other chronic pain conditions 6.

Table 1.

| 1990 | 2010 |

|---|---|

| History of widespread pain |

WPI ≥ 7 and SS ≥ 5 OR WPI 3–6 and SS ≥ 9 |

| Pain of ≥ 3 months’ duration | Symptoms have been present at a similar level for ≥ 3 months |

| Pain in 11 of 18 tender points on digital palpation | Patient does not have a disorder that would otherwise explain the pain |

| Definitions | |

Widespread pain

|

WPI score

|

Tender points (all bilateral)

|

SS score

|

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; FM, fibromyalgia; SS, symptom severity; WPI, Widespread Pain Index.

While many potential mechanisms for FM have been evaluated, recent evidence suggests that dysfunction in central nervous system pain processing mechanisms including central sensitisation or central augmentation of pain contribute to the development of chronic pain in patients with FM 21, 22. This results in the ‘volume control’ for pain being turned up 4, and patients experience allodynia (a heightened sensitivity to stimuli that are not normally painful), and hyperalgesia (an increased response to painful stimuli) 5, 22, 23. Patients with FM therefore experience pain for what patients without FM perceive as touch, and exhibit an increased sensitivity and/or a decreased threshold to a variety of inputs including heat, cold, auditory and electrical stimuli 21, 22. This theory of central sensitisation or central augmentation helps to explain both the heterogeneous clinical aspects of FM and several of the associated symptoms, because many of the same neurotransmitters that control pain and sensory sensitivity also control sleep, mood, memory and alertness 4, 21.

Fibromyalgia can develop at any age, including childhood, although the peak age is usually mid‐life 6, 24, and while the exact causes of FM are unclear, they are thought to involve both environmental (mental or physical trauma, prior medical illness) and genetic factors (first‐degree relatives of patients with FM have an eightfold increased likelihood of developing FM) 24, 25, 26. FM is a potentially disabling condition with a high burden of illness 14, 27. FM is also associated with a number of common comorbidities including cardiac disorders, psychiatric disorders, sleep disturbances, IBS, chronic fatigue syndrome, interstitial cystitis, headache/migraine, hypertension, obesity and disorders of lipid metabolism, which might add to the overall disability burden and amplify treatment costs 5, 28, 29.

Barriers to managing FM in primary care

Although our understanding of FM has increased considerably in recent years, the barriers to diagnosis and optimal treatment are many and varied. Globally, there are inconsistencies in the recognition of symptoms, and in the validity of FM as a diagnosis 13. Even where guidelines are available, physicians in different regions may have varying levels of awareness of these guidelines. This, in turn, results in wide variations in the time to diagnosis of FM between geographical regions (ranging from 2.6 to 5 years in the USA, Latin America and Europe) 5, 30.

In addition to diagnostic barriers, there are major inconsistencies between treatment practices. There is still some debate over the optimal choice and sequence of treatments for FM 31, and the approval status, availability and reimbursement of therapeutic agents varies between countries 32. Treatment guidelines currently make varying recommendations, possibly because of different criteria used to grade recommendations 33, and there might also be cultural differences regarding patient treatment expectations (e.g. ethnic variance in the level of pain perception) 30. Furthermore, prescribing practices might differ according to whether a patient is seen by a primary care physician or a specialist, on the HCP's familiarity with treatment guidelines, and on the availability of local resources for disease management.

Finally, the lack of a clear patient pathway and healthcare system for diagnosis and management of FM often results in patients being passed from physician to physician, receiving multiple drugs to treat different symptoms and suffering increased disability 12, 30, 34. Many primary care physicians still prefer to refer the patient to a specialist 7, particularly when patients have multiple comorbidities that are likely to require a considerable amount of time to investigate and manage. However, the majority of FM cases could be diagnosed and treated in primary care, and a patient‐centric multidisciplinary approach to FM in primary care would result in more rapid diagnosis, more effective management, improved outcomes for patients and better use of health resources 4, 35.

Unmet needs

Despite improvements in the understanding of the condition, FM remains under‐diagnosed and under‐treated. A large proportion of physicians, particularly in primary care, report unclear diagnostic criteria, a lack of confidence in using the ACR criteria for diagnosis, insufficient training/skill in diagnosing FM and a lack of knowledge of treatment options 7, 11, 13. Furthermore, both patients and physicians express dissatisfaction with the delays in reaching a diagnosis and obtaining effective treatment 12. Several surveys of patients with FM have reported dissatisfaction with FM medication and overall treatment 8, 16, 36. A survey of 800 patients reported that 35% believed that their chronic, widespread pain was not well managed by their current treatment, and 22% were not satisfied with the impact of their treatment on fatigue 8.

Diagnosis of FM

Fibromyalgia is a disease with unique clinical characteristics, making it suitable for diagnosis in the primary care setting. Prompt diagnosis of the disorder is an essential component of successful FM management 18. Studies have shown that a diagnosis of FM is associated with improved satisfaction with health, and a reduction in the utilisation of medical resources and the associated costs (in particular, a reduction in referrals and investigations), relative to patients with FM symptoms who remain undiagnosed 37, 38.

ACR criteria

The first ACR criteria for FM, published in 1990 (Table 1) 1, 39, were intended mainly for research classification, and were not intended to be used in clinical practice 6. Although commonly cited in the literature, the 1990 ACR criteria were not widely used by primary care physicians, possibly owing to their reliance on tender points and lack of consideration of other symptoms 3. Revised ACR diagnostic criteria, published in 2010 9, were not meant to replace the 1990 criteria, rather they were an alternative for clinical diagnosis. As the revised criteria do not require a tender point examination (Table 1) 9 and are simple to administer, they might prove to be more practical and user‐friendly for primary care physicians.

A further modification of the ACR criteria, in 2011, was intended to simplify them for practical use in epidemiological and clinical studies 10. The 2011 criteria include a 1‐page patient self‐report symptom survey to determine the locations of pain and the presence/severity of fatigue, sleep disturbances, memory difficulties, headaches, irritable bowel symptoms and mood problems (for further information, Clauw 6 and Wolfe et al. 10).

Diagnosis of FM in clinical practice

In clinical practice, FM should be considered in any patient reporting chronic multifocal or diffuse pain 6. FM is also commonly comorbid in patients with rheumatic diseases, including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and ankylosing spondylitis 40; in patients with other pain conditions 41; and in those with thyroid dysfunction 42. A suspicion of FM might develop during symptom progression, especially if the patient visits the clinic on multiple occasions reporting chronic pain in various body areas, tiredness and problems with sleeping 5. The presence of some comorbid disorders might also be a key factor in helping to diagnose FM, especially mood disorders, IBS, migraine, pelvic or genitourinary pain and temporomandibular disorder 5. However, the presence of comorbidities increases the complexity of the patient, and is likely to impact on the rapidity of diagnosis. These patients are likely to take more time at the physician's office and may require collaboration with specialists and other HCPs to produce an accurate diagnosis and optimal management plan 41, 43.

Importantly, FM is not a diagnosis of exclusion 5, to be brought out as a last resort after testing for other conditions. The physician can assess the patient's medical history to determine whether they meet the criteria for FM, and perform a physical examination (evaluation of joints for the presence of inflammation, a neurological examination and an assessment of tenderness or pain threshold by digital palpation) to assess for other potential contributing causes of the symptoms 5. Laboratory tests are usually not necessary to confirm a diagnosis of FM. Basic tests such as blood count and serum chemistries might be of use in guiding the assessment, and a thyroid function test can be used to assess hypothyroidism, which is common and treatable, but detailed serologic studies are not necessary unless an autoimmune or other condition is suspected based on the patient's history and examination 5, 6. If FM is suspected, patient screening can begin by asking the patient to complete self‐report measures such as a body pain diagram and assessment of symptoms 5. Once diagnosed, treatment for FM can be initiated immediately, even if a patient requires further tests to clarify some unusual signs or symptoms, or requires referral to a specialist for evaluation of comorbidities 5.

Treatment of FM

As the pathogenesis of FM has not been entirely elucidated, this has limited the development of disease‐modifying treatments 44. As such, current treatment options focus on symptom‐based management to improve function and quality of life. However, it is generally accepted that integration of pharmacological and non‐pharmacological treatments will give the best outcome for the patient 6.

Pharmacological treatments

Studies have shown that the majority of patients attempt to manage their symptoms themselves before presenting to a physician 8. This might account for the fact that the medications most commonly used by patients with FM include basic analgesics, such as acetaminophen and non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs 45, although there is limited evidence that they are effective in FM 46. More concerning, given the potential for misuse and addiction, a commonly prescribed treatment for FM (both before and after diagnosis) is short‐acting strong opioids 45, 47, despite clinical trial reports indicating that opioids do not reduce pain in FM 4, 46, 48.

In the USA, three drugs are currently approved for the treatment of FM 32: pregabalin (Pfizer Inc., New York, NY; approved 2007) 49, duloxetine (Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN; 2008) 50 and milnacipran (Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc., St. Louis, MO; 2009) 51. These medications work either to increase the activity of inhibitory neurotransmitters (to ‘turn down the pain volume’) or to reduce the activity of facilitatory neurotransmitters (which ‘turn up the pain volume’) 6. In contrast, there are currently no medications approved for the treatment of FM in Europe, even though pregabalin, duloxetine and milnacipran have all been approved in Europe for other indications 32. Table 2 summarises the FDA‐approved pharmacological treatment options for FM. Titration to the therapeutic dose is recommended to improve patient response. In some patients, starting at a lower dose and titrating more slowly may be necessary to lessen the risk of intolerability and discontinuation of treatment.

Table 2.

| Drug | FDA approval | Mechanism of action | Efficacy studies | Primary end‐points | Dosing | Adverse eventsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregabalin | 21 June 2007 | Non‐selective α2δ ligand |

|

Pain reduction, improvements in PGIC and FIQ | 300–450 mg/day; start at 75 mg bid (might increase to 150 mg bid within 1 week); max dose 225 mg bid | Dizziness, somnolence, dry mouth, oedema, blurred vision, weight gain, abnormal thinking |

| Duloxetine | 16 June 2008 | SNRI |

|

Pain reduction, improvements in PGIC and FIQ | 60 mg/day; start 30 mg/day for 1 week then increase to 60 mg/day | Nausea, dry mouth, somnolence, constipation, decreased appetite, hyperhidrosis |

| Milnacipran | 14 January 2009 | SNRI |

|

Composite end‐point that concurrently evaluated improvement in pain (VAS), physical function (SF‐36 PCS) and patient global assessment (PGIC) | 100 mg/day; start 12.5 mg/day, increasing incrementally to 50 mg bid in 1 week; maximum dose 100 mg bid | Nausea, constipation, hot flush, hyperhidrosis, vomiting, palpitations, increased heart rate, dry mouth, hypertension |

bid, twice daily; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; FIQ, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FM, fibromyalgia; PGIC, patient global impression of change; SF‐36 PCS, Short‐Form 36 Physical Component Summary; SNRI, serotonin‐norepinephrine re‐uptake inhibitor; VAS, visual analogue scale.

The most commonly reported adverse events are shown. For full details, please refer to the prescribing information for each drug.

Other medications such as amitriptyline, cyclobenzaprine, gabapentin and fluoxetine have demonstrated efficacy in randomised, controlled trials of FM and are commonly used to treat FM, although they are not approved for this indication by the FDA 52, 53, 54. The selection of pharmacological agent(s) for the management of FM should be tailored according to a number of factors, including the presence of additional symptoms (e.g. fatigue, sleep disturbances) alongside pain, the presence of comorbidities such as anxiety or rheumatic disease, and the tolerability profile of the therapeutic options 6. Patients with FM often require multiple medications to treat their symptoms and comorbidities, and guidance on possible medication combinations has been previously published 54. It is important to select combination therapies that are not associated with adverse drug–drug interactions.

Non‐pharmacological treatments

Non‐pharmacological treatments should be an integral component of a prescribed treatment plan for patients with FM 31. Patient education, exercise, some forms of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), and sleep hygiene are the most‐studied non‐pharmacological treatments and have demonstrated efficacy in patients with FM 4, 6.

Educational materials for patients are widely available on the Internet from many Web sites, including those run by the ACR (http://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Fibromyalgia), the American Chronic Pain Association (http://www.theacpa.org/condition/fibromyalgia), and a variety of FM support and advocacy groups, many of which also have local chapters where patients with FM and their families can share their experiences, discuss common concerns and reduce the feelings of isolation that are common in FM. The University of Michigan's FibroGuide® (https://fibroguide.med.umich.edu/) is a self‐management programme for patients with FM that incorporates effective management strategies into an easily available online format.

Among exercise interventions, aerobic exercise appears to be most beneficial, starting with low‐to‐moderate intensity activities (such as walking, swimming or cycling on a stationary bicycle) and upgrading the intensity over time to reach a goal of 30–60 min of exercise at least two to three times weekly 54. Continuation of the exercise regimen is important, because ongoing exercise has been associated with maintenance of improvements in FM. Referrals to CBT and sleep hygiene specialists should be made based on the facilities available in the local area and affordability for patients.

Complementary and alternative medicine might also be considered, but in general, there are few randomised, controlled trials of these treatments (e.g. yoga, tai chi, acupuncture, chiropractic, massage therapy, trigger‐point injections, forms of physical therapy, relaxation training, diet) in patients with FM 4, 6, 24, 31. The non‐pharmacological treatment options for FM are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

| Treatment | Regimen | Reported outcomes | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient education | Provide core information about diagnosis, treatment and prognosis; manage expectations | Can improve symptoms and functionality; might reduce disability levels |

|

|

| Exercise | Start low, go slow: build up to moderate activity over time | Can improve physical function, quality of life and reduce symptoms of pain and depression |

|

|

| CBT | Face‐to‐face counselling, online self‐help courses, books, CDs, FM Web sites | Provides knowledge about FM and coping strategies. Can provide sustained improvements in FM symptoms, and reduce impact on daily life |

|

|

| Sleep hygiene | Optimise sleep environment and prioritise relaxing sleep routine | Can improve pain scores and mental well‐being |

|

|

| CAM therapies | Various: examples include tai chi, yoga, massage, diet, balneotherapy and acupuncture | Can increase patient self‐sufficiency and improve pain/functioning |

|

|

CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; FM, fibromyalgia; HCP, healthcare professional.

Strategies to manage FM in primary care

The key to effective management of patients with FM in primary care is an integrated approach to treatment, a coordinated framework of clinical and non‐clinical support, multifaceted education and clarity of goals and expectations.

Physician education

In order for the majority of FM diagnosis and treatment to take place in primary care, non‐specialist physicians must have the necessary tools and training to recognise symptoms and feel confident in prescribing treatments. Unfortunately, although most primary care physicians receive some training in basic pain assessment and management, in many cases, it is too brief to be meaningful 11, 34. Additional training might be required, either via some form of e‐learning, or led by specialists or colleagues with experience in chronic pain, to disseminate information and translate knowledge into skills and actions 11, 34.

A lack of knowledge of current diagnostic criteria might be one reason leading to delays in diagnosing FM, but primary care physicians might also be limited by the consultation time available to make a diagnosis, particularly when patients have multiple symptoms that must be evaluated and discussed 8. As patients might initially present with one of the symptoms commonly associated with FM, such as mood symptoms or fatigue, the physician might need to be proactive in enquiring about pain symptoms 48. The development, validation and widespread implementation of tools to simplify symptom assessment could be one way to improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce delays in initiating treatment 11, 55.

Patient education

As with any chronic condition that requires ongoing management, patient education is critical in aiding patient understanding, acceptance and self‐management of their condition 4. The primary care physician is uniquely placed to form a strong therapeutic relationship with patients and provide critical ongoing support 48. The use of familiar terminology might help the patient better understand the clinical picture and provide reassurance 4. However, because time for patient education is likely to be limited during a consultation, the use of clinical support staff to provide supplementary information is key, along with details of useful educational sources (books, Web sites, advocacy groups, etc.) 4, 48.

In addition to educating patients about FM, it is also recommended that physicians partner with patients to decide on treatments, set goals and manage their expectations of symptom improvement and impact on daily life 4, 13, 34. Poor communication between patient and physician is likely to lead to frustration and over‐reliance on pharmacological interventions with limited benefit; whereas shared decision making and positive interactions might help patients engage with their treatment and actively manage their pain 48. Education around adherence might also be necessary, to encourage the continuation of treatment to allow time for symptomatic improvement 4.

Setting treatment goals

It is important for patients with FM to understand the limitations of current treatments for their condition, and to acknowledge that therapy might restore and maintain quality of life and considerably reduce pain, but will seldom remove pain completely 17, 48. As many aspects of daily life might be affected by FM, a key step is to identify which are most important to the patient and develop a treatment plan based on prioritising the areas that affect them most 4. While some patients might simply want a reduction in pain, others might prefer to focus on obtaining restorative sleep, or reducing fatigue levels to improve work or family relationships 17. These goals should be established early after diagnosis, to provide structure and guidance for future consultations and treatment decisions, but it is important that they be realistic, specific and easily tracked to provide a measure of treatment benefit 4.

Integrated multimodal treatment

A comprehensive treatment plan should include non‐pharmacological treatments, pharmacological therapies and active patient coping strategies. As FM is associated with a constellation of symptoms, no single treatment can be expected to target every one of them. The treatment approach must be flexible to incorporate changes as the condition progresses, and it is likely to require the collaboration of a number of HCPs, particularly for the treatment of some comorbidities 4. Patients can be encouraged to identify and maintain active coping strategies, in an attempt to reduce disability 34. Comorbidities, such as severe depression or marked psychosocial stressors, might necessitate referral to a mental health specialist, while medical comorbidities might require additional treatment from a range of specialists such as rheumatologists, gastroenterologists and sleep specialists. The primary care physician plays an important role in coordinating specialists and ancillary HCPs to provide continuity of care for the patient.

Tracking progress

Surveys of HCPs have reported that many primary care physicians report a lack of knowledge of treatment options and monitoring tools 11. This is a key limitation, because it is only by tracking symptom presence and severity that the impact of treatment can be evaluated. There are several scales and questionnaires available that have been developed to evaluate the different symptoms of FM, and these might be useful to provide an initial health status, and a marker from which progress can be tracked 4, 35. However, such tools need to be reliable, validated in patients with FM, rapid to administer and easy to interpret, to be globally accepted and used routinely in the clinic.

Using electronic records

The use of computers and technology is now ubiquitous throughout society, and health care is no exception. In recent years, HCPs have moved towards keeping electronic records, providing an opportunity to integrate FM management, improve outcomes and reduce costs and unnecessary testing 35. Electronic records can improve access to patient information across multiple specialties that might be involved in care decisions, provide information to guide prescribing decisions according to current recommendations, reduce medication errors and possibly aid in identifying undiagnosed patients 35. In a recent retrospective analysis, it was shown that a potential diagnosis of FM was associated with more frequent emergency room visits, outpatient visits, and hospitalisations and higher medication use. The authors concluded that all of these variables could be identified from electronic medical records, suggesting that routine data collection and input could have a direct application to FM diagnosis and care management 56.

For HCPs, identification of patients undergoing multiple exploratory tests might aid in focusing resources, to break the cycle of long‐term medical spending. Online or application‐based tools could also expedite administration and interpretation of monitoring scales, to rapidly gain a clear picture of symptom control and therapeutic outcome 35.

The medical home for management of FM

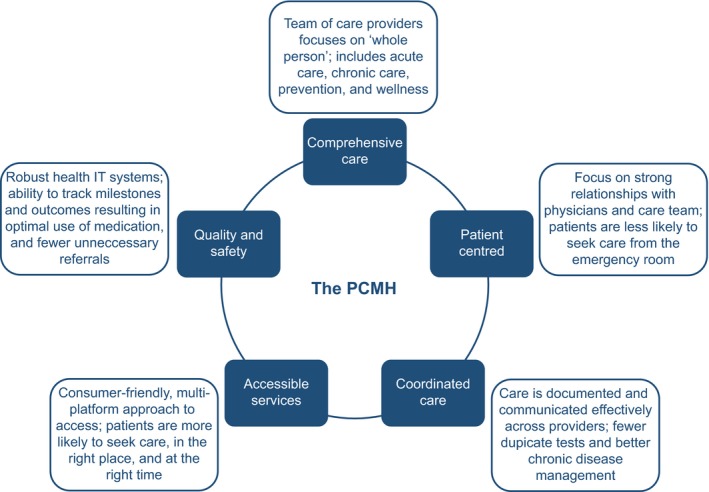

It is possible to transform primary care into a system in which medical practices can be improved to provide team‐based care and data‐driven integrated delivery, using the concept of the patient‐centred medical home (PCMH). In the PCMH, decision making is guided by evidence‐based medicine and decision‐support tools. Patients are active partners in their treatment and information technology is utilised to support education, communication, data collection and performance measurement 57, 58. The principles of the medical home were developed by key organisations, including the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. The aim of a PCMH was to provide comprehensive primary care for all ages and throughout all stages of life, by coordinating and integrating care (chronic, acute, preventative and end‐of‐life) across all elements of the healthcare system, to improve efficiency and effectiveness (Figure 1) 57, 58.

Figure 1.

The PCMH: framework and principles. IT, information technology; PCMH, patient‐centred medical home

While the PCMH may not be feasible in all practices (owing to an absence or scarcity of resources) or in all countries (due to the widely varying healthcare systems between nations), it can provide a vision for the future management of FM and other chronic conditions by demonstrating how integration and coordination of doctors, hospitals, pharmacies and community resources can improve patient experience and outcomes while potentially reducing waste and inefficiency 59, 60. The changing landscape of health management across the US and elsewhere 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 provides an opportunity for many HCPs and practices to implement a chronic care framework for FM management, similar to that already in use for diabetes 4. Results to date indicate that the PCMH is a viable mechanism to qualitatively improve diabetes management, while potentially reducing the costs of long‐term care 65, 66, 67, 68. The PCMH concept has also been successfully implemented in the field of mental health, resulting in reduced rates of hospitalisations, fewer specialty care visits and increased primary care consultations for patients with conditions such as post‐traumatic stress disorder 69, 70. However, of all the patients treated in primary care, those with chronic pain are most in need of practice reform 71. The first steps towards improving FM care have already been taken, with recent publications from the USA and the UK laying the groundwork for a focused and supported management pathway for patients with FM and chronic pain 4, 34, 48. It is hoped that by addressing the current challenges and suggesting potential areas for restructuring, proposals for PCMH implementation and FM management in primary care can be implemented rapidly and smoothly into current practices.

Implementing a medical home for FM

Personnel

One obvious factor affecting the adoption of any new primary care framework is practice size. Small practices, with just one or two physicians, are unlikely to have either the personnel or the systems to be able to fully implement the PCMH concept 72. However, the current trend in the USA is towards larger practice sizes, since they might enjoy economies of scale, whereby several physicians can share support staff 72, 73.

In the PCMH model, a typical primary care office is likely to require two to four support staff for each physician 74, 75. In an office with four to six full‐time employees, this is likely to mean two full‐time physicians and several part‐time support staff in various ratios. Support staff commonly includes registered nurses, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and medical assistants (see Appendix 1), as well as a pharmacist, who might be shared between several practices 74, 75. For FM, and other chronic pain conditions, registered nurses or health coaches are likely to be a key among these team members, enabling patients to understand their condition, and instructing them in the mechanisms and benefits of self‐management 76, 77, 78. Since patients with FM commonly have psychiatric comorbidities, behavioural health workers might also be a necessary adjunct to the team, alongside care coordinators, a largely clerical role, but pivotal to ensuring referrals are made and followed up 76, 77, 78.

The aim of the PCMH is to engage multiple HCPs in providing hands‐on management to assist patients in navigating the care system. This requires a team‐based approach, to spread the load, maximise efficiency and make the best use of each team member's professional skills 79. One of the key ingredients of a successful PCMH is effective leadership within the practice, both to facilitate the transition and to serve as the patient's primary care provider 62. Depending on state law, this leadership might come from a physician or from a nurse practitioner 78, 79, 80. In either case, the individual must be able to meld diverse personalities with widely differing levels of training into a cohesive team, all members of which are functioning at the highest level and contributing to the health of their patients 81, 82. Conversely, one potential obstacle to overcome might be a reluctance to delegate or re‐allocate tasks. Staff familiar with the PCMH or external facilitators might be needed during the transition period to ensure that authority and responsibility are shared by the entire team 76, 81, 82.

Ultimately, transitioning a primary care practice to a PCMH can have many benefits for the HCPs involved. Primary care physicians have reported increased job satisfaction, because they have an improved HCP–patient relationship, and are better able to focus on the more complex aspects of care 76. Medical assistants and nursing staff report improved job satisfaction from the increased responsibility and feeling more involved in patient care 76. Furthermore, PCMH reform can help to improve primary care attitudes towards patients with chronic pain, by providing incentives and increasing opportunities for specialised education and training 71.

Challenges

While the PCMH is an appealing proposition in terms of benefit to patients and HCPs, there are also several challenges associated with the concept, which need to be carefully considered prior to initiating practice reform. Significant time and expense may be needed to meet the required criteria and benchmarks 58, 59, 60, 83, which may tax the resources of small practices and solo practitioners. It may be necessary to hire additional staff to meet the management and administrative demands of PCMH operations, upgrade and maintain IT infrastructure, and establish the type of electronic records network necessary to fulfil PCMH technology and access requirements 58, 62. Geographical location may also be an issue, because a small rural practice without adequate local specialists, non‐physician HCPs or supportive community resources may be limited in its ability to meet collaborative care standards 83.

However, physicians should not be discouraged from implementing at least some aspects of the PCMH, and should seek advice from experienced healthcare advisors who will be able to assess the ability of each practice to meet the PCMH requirements or develop other viable options that may be better suited to the needs and capabilities of any given practice. Furthermore, financial support, training and technical aid may be available to assist in the transition process towards PCMH recognition 59, 64, 83.

Best practice

For a patient such as Susan, getting a diagnosis of FM often takes several years, many examinations and procedures, and multiple visits to various doctors. However, implementation of a medical home is an opportunity to reduce the timescale between presentation and diagnosis, and revise the scenario to limit unnecessary tests and referrals. FM is a clinical diagnosis that can be appropriately made by primary care physicians based on the clinical characteristics of the disorder. Faster symptom recognition and diagnosis might be possible, to enable earlier treatment initiation. The PCMH has been shown to improve outcomes in diabetes and mental health; thus, it should be viable to adapt the model for FM and chronic pain.

Given her symptoms, Susan is most likely to present to her primary care doctor several times over a few weeks or months. The primary care physician is therefore ideally placed to observe and record these seemingly disparate and generalised symptoms (pain, depression, fatigue, IBS), and to suspect that FM could be the underlying cause that links them together. In addition to more education in chronic pain, the development of FM‐ or pain‐specific tools that could be easily used during an office consultation would further assist the primary care physician in making the diagnosis of FM. Several such screening/diagnostic tools are currently under evaluation for use in primary care, including the Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Screen 55, 84 and the FibroDetect® tool 85. Both appear to have good sensitivity and specificity, and may facilitate the identification of patients with FM in the primary care setting, although further validation in diverse settings is required.

With the primary care physician as PCMH ‘team captain’, he/she makes the diagnosis and manages effective treatment, and other members of the team act on their roles in ongoing care. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners might carry out tests to evaluate the patient' symptoms and will liaise with the primary care physician to develop a management plan. A clinical pharmacist advises on treatment guidelines and local availability of medication, and allows for remote dispensing. Registered nurses and health coaches help patients to take control of their situation and coach them on self‐management techniques. Care coordinators and medical assistants ensure that required tests are carried out, that results are entered into an electronic health record system that allows access by all stakeholders, and that any referrals deemed necessary are coordinated with the relevant hospital or specialist.

Although patients with FM can be very challenging to diagnose and treat, there is good evidence to suggest that interventions meeting PCMH criteria are associated with an overall improvement in patient satisfaction and perceptions of care 63. By putting the patient at the centre of care, the PCMH allows patients to manage their own lives 86, and gives them strategies to help themselves 87, rather than viewing themselves as invalids reliant upon HCPs to ‘cure’ them. Currently, patients with FM are inclined to try to use specialists as primary care providers, whereas the PCMH would reduce this problem, introducing specialist consultations only when needed. However, to achieve this, appropriate self‐management tools are necessary, and the development of suitable Web sites and community resources will be a key element.

Conclusions

The management pathway for FM and chronic pain is currently often lengthy and complex, involving repeated clinic visits, unnecessary referrals and costly tests. The medical home, a patient‐centred management framework which has been successfully implemented in other chronic diseases, might provide the key to reducing diagnosis time and improving patient outcomes. The PCMH sets up a health delivery model within the practice via the provision of a primary care team incorporating professionals with a range of skills and training, all functioning at the highest level for maximum efficiency and working together for the benefit of the patient. A multifaceted approach to treatment, including patient education and non‐pharmacological and pharmacological therapies, is a key, but prioritising symptoms, tracking progress and managing patient expectations are equally important. Effective approaches to helping practices adopt the medical home and tailor it to the needs of the patient with chronic pain will be important. Although there remain several barriers to overcome, implementation of a PCMH for chronic pain would allow FM to be successfully managed in the primary care setting.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the article conception, critical revision of each draft and approval of the final version.

Funding and Acknowledgements

The funding for this article was provided by Daiichi Sankyo, Inc.; however, company personnel had no role in article design, manuscript preparation or publication decisions. The authors did not receive financial remuneration for the writing of this manuscript. The authors thank Sally‐Anne Mitchell, PhD (ApotheCom, Yardley, PA) for editorial assistance with this manuscript. This assistance was funded by Daiichi Sankyo, Inc.

Appendix 1. Healthcare provider definitions.

| Job title | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Behavioural health worker | Support staff worker who provides psychological therapeutic support to patients with behavioural health issues and psychological disorders; generally requires a qualification in psychology, social work, counselling or nursing |

| Care coordinator | Liaises between patients and other healthcare professionals; ensures patients understand their medical condition and treatment, locates community resources and coordinates patient care services and referrals |

| Dietician | An expert in human nutrition and the regulation of diet; advises people on what to eat to achieve health‐related goals |

| Health coach | An individual trained to assist patients by promoting coping behaviours, goal setting and overcoming negativity; generally requires a qualification in exercise science, nutrition, health care or wellness. Similar processes may also be performed by a psychotherapist |

| Healthcare professional (HCP) | Any individual trained to provide healthcare services; may include physicians, nurses, therapists and support workers |

| Medical assistant | A healthcare professional supporting physicians and other healthcare providers; they perform routine tasks and procedures such as measuring vital signs, collecting biological specimens, completing electronic medical records and scheduling appointments. Qualifications and requirements for certification vary between jurisdictions |

| Nurse practitioner | An advanced practice registered nurse who has been trained to diagnose and manage acute illness and chronic conditions. A nurse practitioner may serve as a primary care provider; in the USA, depending upon which state they work in, nurse practitioners may or may not be required to practice under the supervision of a physician |

| Pharmacist | Healthcare professional who understands the mechanisms and actions of drugs, side effects, drug interactions and monitoring requirements; they provide pharmaceutical information and oversee the dispensation of prescription medication as well as non‐prescription or over‐the‐counter drugs. A further education qualification is required |

| Physical therapist | Rehabilitation professional who manages patients with health conditions that limit their ability to move and perform functional activities |

| Physician assistant | A healthcare professional who is licenced to practice medicine as part of a team with physicians and other providers; may be known as a physician associate in the UK. A physician assistant may conduct physical exams, order tests, diagnose and treat illnesses and perform medical procedures under the supervision of another physician |

| Primary care physician | A physician who provides the first point of contact for a patient and continuing care of medical conditions; may be known as a general practitioner in English‐speaking countries outside of the USA |

| Primary care provider | A healthcare professional providing day‐to‐day health care in a primary care setting; may be a primary care physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant |

| Psychiatrist | A physician specialising in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders |

| Registered nurse | A nurse who has undergone training and met the requirements to obtain a nursing licence |

| Specialist | A physician or surgeon who has completed further medical education and training in a specific branch of medical practice |

Disclosures Dr Arnold reports grants and personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Forest, and Theravance; personal fees from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Purdue, Toray, Shire, Innovative Med Concepts, Ironwood, and Zynerba; and grants from Takeda, Tonix, Cerephex Corporation, and Eli Lilly and Company outside the submitted work. Dr Gebke reports personal fees from Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr Choy reports personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Pfizer, Tonix, and Eli Lilly, outside the submitted work.

References

- 1. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33: 160–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Queiroz LP. Worldwide epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2013; 17: 356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glennon P. Fibromyalgia syndrome: management in primary care. Rep Rheum Dis 2010; series 6: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, Dunegan LJ, Turk DC. A framework for fibromyalgia management for primary care providers. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87: 488–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, McCarberg BH. Improving the recognition and diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin Proc 2011; 86: 457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA 2014; 311: 1547–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hadker N, Garg S, Chandran AB et al. Primary care physicians’ perceptions of the challenges and barriers in the timely diagnosis, treatment and management of fibromyalgia. Pain Res Manag 2011; 16: 440–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choy E, Perrot S, Leon T et al. A patient survey of the impact of fibromyalgia and the journey to diagnosis. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 10: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res 2010; 62: 600–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2011; 38: 1113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gulec H, Sayar K, Yazici GM. The relationship between psychological factors and health care‐seeking behavior in fibromyalgia patients. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi 2007; 18: 22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Briones‐Vozmediano E, Vives‐Cases C, Ronda‐Perez E, Gil‐Gonzalez D. Patients’ and professionals’ views on managing fibromyalgia. Pain Res Manag 2013; 18: 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hayes SM, Myhal GC, Thornton JF et al. Fibromyalgia and the therapeutic relationship: where uncertainty meets attitude. Pain Res Manag 2010; 15: 385–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robinson RL, Kroenke K, Mease P et al. Burden of illness and treatment patterns for patients with fibromyalgia. Pain Med 2012; 13: 1366–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McNett M, Goldenberg D, Schaefer C et al. Treatment patterns among physician specialties in the management of fibromyalgia: results of a cross‐sectional study in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin 2011; 27: 673–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robinson RL, Kroenke K, Williams DA et al. Longitudinal observation of treatment patterns and outcomes for patients with fibromyalgia: 12‐month findings from the reflections study. Pain Med 2013; 14: 1400–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Brien EM, Staud RM, Hassinger AD et al. Patient‐centered perspective on treatment outcomes in chronic pain. Pain Med 2010; 11: 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldenberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA 2004; 292: 2388–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro‐Dasilva MC, Rahim‐Williams B, Riley JL III. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain 2009; 10: 447–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vincent A, Lahr BD, Wolfe F et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: a population‐based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, utilizing the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Arthritis Care Res 2013; 65: 786–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clauw DJ, Arnold LM, McCarberg BH. The science of fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin Proc 2011; 86: 907–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Phillips K, Clauw DJ. Central pain mechanisms in chronic pain states–maybe it is all in their head. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25: 141–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Staud R. Abnormal endogenous pain modulation is a shared characteristic of many chronic pain conditions. Expert Rev Neurother 2012; 12: 577–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crofford LJ. Fibromyalgia. Atlanta, GA: American College of Rheumatology, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mease P. Fibromyalgia syndrome: review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, outcome measures, and treatment. J Rheumatol Suppl 2005; 75: 6–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arnold LM, Hudson JI, Hess EV et al. Family study of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 944–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perrot S, Winkelmann A, Dukes E et al. Characteristics of patients with fibromyalgia in France and Germany. Int J Clin Pract 2010; 64: 1100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haviland MG, Banta JE, Przekop P. Fibromyalgia: prevalence, course, and co‐morbidities in hospitalized patients in the United States, 1999‐2007. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011; 29: S79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. White LA, Birnbaum HG, Kaltenboeck A et al. Employees with fibromyalgia: medical comorbidity, healthcare costs, and work loss. J Occup Environ Med 2008; 50: 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clark P, Paiva ES, Ginovker A, Salomon PA. A patient and physician survey of fibromyalgia across Latin America and Europe. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013; 14: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ablin J, Fitzcharles MA, Buskila D et al. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: recommendations of recent evidence‐based interdisciplinary guidelines with special emphasis on complementary and alternative therapies. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2013; 2013: 485272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Briley M. Drugs to treat fibromyalgia – the transatlantic difference. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2010; 11: 16–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hauser W, Thieme K, Turk DC. Guidelines on the management of fibromyalgia syndrome – a systematic review. Eur J Pain 2010; 14: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Price C, Lee J, Taylor AM, Baranowski AP. Initial assessment and management of pain: a pathway for care developed by the British Pain Society. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 816–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wells AF, Arnold LM, Curtis CE et al. Integrating health information technology and electronic health records into the management of fibromyalgia. Postgrad Med 2013; 125: 70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lauche R, Hauser W, Jung E et al. Patient‐related predictors of treatment satisfaction of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a cross‐sectional survey. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013; 31: S34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Annemans L, Wessely S, Spaepen E et al. Health economic consequences related to the diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hughes G, Martinez C, Myon E, Taieb C, Wessely S. The impact of a diagnosis of fibromyalgia on health care resource use by primary care patients in the UK: an observational study based on clinical practice. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Staud R. Chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia: two sides of the same coin? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2009; 11: 433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Haliloglu S, Carlioglu A, Akdeniz D, Karaaslan Y, Kosar A. Fibromyalgia in patients with other rheumatic diseases: prevalence and relationship with disease activity. Rheumatol Int 2014; 34: 1275–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Davis JA, Robinson RL, Le TK, Xie J. Incidence and impact of pain conditions and comorbid illnesses. J Pain Res 2011; 4: 331–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ahmad J, Tagoe CE. Fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain in autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin Rheumatol 2014; 33: 885–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ablin JN, Buskila D. “Real‐life” treatment of chronic pain: targets and goals. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015; 29: 111–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Podolecki T, Podolecki A, Hrycek A. Fibromyalgia: pathogenetic, diagnostic and therapeutic concerns. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2009; 119: 157–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bennett RM, Jones J, Turk DC, Russell IJ, Matallana L. An internet survey of 2,596 people with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mease PJ, Dundon K, Sarzi‐Puttini P. Pharmacotherapy of fibromyalgia. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25: 285–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sanchez RJ, Uribe C, Li H et al. Longitudinal evaluation of health care utilization and costs during the first three years after a new diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Curr Med Res Opin 2011; 27: 663–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee J, Ellis B, Price C, Baranowski AP. Chronic widespread pain, including fibromyalgia: a pathway for care developed by the British Pain Society. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lyrica (pregabalin) capsules, CV; Lyrica (pregabalin) oral solution, CV, [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cymbalta (duloxetine delayed‐release capsules) for oral use [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Lilly USA, LLC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Savella (milnacipran HCl) tablets [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Laboratories, Inc., 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Traynor LM, Thiessen CN, Traynor AP. Pharmacotherapy of fibromyalgia. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2011; 68: 1307–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smith HS, Bracken D, Smith JM. Pharmacotherapy for fibromyalgia. Frontiers Pharmacol 2011; 2: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Arnold LM. Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia. New therapies in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther 2006; 8: 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Martin SA, Coon CD, McLeod LD, Chandran A, Arnold LM. Evaluation of the fibromyalgia diagnostic screen in clinical practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2014; 20: 158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Masters ET, Mardekian J, Emir B et al. Electronic medical record data to identify variables associated with a fibromyalgia diagnosis: importance of health care resource utilization. J Pain Res 2015; 8: 131–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. California Heathcare Foundation . Chronic Disease Registries: A Product Review. Oakland, CA, Sacramento, CA: California Healthcare Foundation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58. American College of Physicians . Joint Principles of the Patient Centered Medical Home. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 59. National Committee for Quality Assurance website . The future of patient‐centered medical homes: foundation for a better health care system. http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Public Policy/2014 Comment Letters/The_Future_of_PCMH.pdf (accessed September 22, 2015).

- 60. Faber M, Voerman G, Erler A et al. Survey of 5 European countries suggests that more elements of patient‐centered medical homes could improve primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32: 797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nielson M, Gibson A, Buelt L, Grundy P, Grumbach K. The Patient‐Centered Medical Home's Impact on Cost and Quality. Annual Review of Evidence 2013‐2014. Washington, DC: Patient‐Centered Primary Care Collaborative, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tirodkar MA, Morton S, Whiting T et al. There's more than one way to build a medical home. Am J Manag Care 2014; 20: e582–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R et al. Improving patient care. The patient centered medical home. A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158: 169–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. National Committee for Quality Assurance . NCQA Patient Centered Medical Home. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bojadzievski T, Gabbay RA. Patient‐centered medical home and diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 1047–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang QC, Chawla R, Colombo CM, Snyder RL, Nigam S. Patient‐centered medical home impact on health plan members with diabetes. J Public Health Manag Pract 2014; 20: E12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ackroyd SA, Wexler DJ. Effectiveness of diabetes interventions in the patient‐centered medical home. Curr Diabetes Rep 2014; 14: 471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Taliani CA, Bricker PL, Adelman AM, Cronholm PF, Gabbay RA. Implementing effective care management in the patient‐centered medical home. Am J Manag Care 2013; 19: 957–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Randall I, Mohr DC, Maynard C. VHA patient‐centered medical home associated with lower rate of hospitalizations and specialty care among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Healthc Qual 2014. doi: 10.1111/jhq.12092. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Amiel JM, Pincus HA. The medical home model: new opportunities for psychiatric services in the United States. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2011; 24: 562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Evans L, Whitham JA, Trotter DR, Filtz KR. An evaluation of family medicine residents’ attitudes before and after a PCMH innovation for patients with chronic pain. Fam Med 2011; 43: 702–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Porter ME, Pabo EA, Lee TH. Redesigning primary care: a strategic vision to improve value by organizing around patients’ needs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32: 516–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Peikes DN, Reid RJ, Day TJ et al. Staffing patterns of primary care practices in the comprehensive primary care initiative. Ann Fam Med 2014; 12: 142–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hsu C, Coleman K, Ross TR et al. Spreading a patient‐centered medical home redesign: a case study. J Ambul Care Manag 2012; 35: 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Patel MS, Arron MJ, Sinsky TA et al. Estimating the staffing infrastructure for a patient‐centered medical home. Am J Manag Care 2013; 19: 509–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. O'Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, Bond A, Tirodkar MA. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient‐centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30: 183–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Moran KJ, Burson R. Understanding the patient‐centered medical home. Home Healthc Nurse 2014; 32: 476–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Henderson S, Princell CO, Martin SD. The patient‐centered medical home: this primary care model offers RNs new practice‐and reimbursement‐opportunities. Am J Nurs 2012; 112: 54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Berenson RA, Devers KJ, Burton RA. Will the Patient‐Centered Medical Home Transform the Delivery of Health Care? Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Schram AP. The patient‐centered medical home: transforming primary care. Nurse Pract 2012; 37: 33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Willard R, Bodenheimer T. The Building Blocks of High‐Performing Primary Care. Oakland, CA: California Healthcare Foundation, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Cronholm PF, Shea JA, Werner RM et al. The patient centered medical home: mental models and practice culture driving the transformation process. J Gen Intern Med 2013; 28: 1195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Scholle SH, Asche SE, Morton S et al. Support and strategies for change among small patient‐centered medical home practices. Ann Family Med 2013; 11(Suppl. 1): S6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Arnold LM, Stanford SB, Welge JA, Crofford LJ. Development and testing of the fibromyalgia diagnostic screen for primary care. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012; 21: 231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Baron R, Perrot S, Guillemin I et al. Improving the primary care physicians’ decision making for fibromyalgia in clinical practice: development and validation of the Fibromyalgia Detection (FibroDetect®) screening tool. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014; 12: 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Fox BP. A PCMH model that works. Reflections on the PBS Special. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/841916 (accessed June 4, 2015).

- 87. Serio CD, Hessing J, Reed B, Hess C, Reis J. The effect of online chronic disease personas on activation: within‐subjects and between‐groups analyses. JMIR Res Protoc 2015; 4: e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]