Abstract

In recent years, iron-based nanoparticles (FeNPs) have been successfully used in environmental remediation and water treatment. This study examined ecotoxicity of two FeNPs produced by green tea extract (smGT, GTFe) and their ability to degrade malachite green (MG). Their physicochemical properties were assessed using transmission electron microscopy, X-ray powder diffraction, dynamic light scattering, and transmission Mössbauer spectroscopy. Using a battery of ecotoxicological bioassays, we determined toxicity for nine different organisms, including bacteria, cyanobacterium, algae, plants, and crustaceans. GTFe, amorphous complex of Fe(II, III) ions and polyphenols from green tea extract, proved low capacity to degrade MG and was toxic to all tested organisms. Superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs (smGT) derived from GTFe, showed no toxic effect on most of the tested organisms up to a concentration of 1g/L, except for algae and cyanobacterium and removed 93 % MG at concentration 125 mg Fe/L after 60 minutes. The procedure described in this paper generates new superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs from existing and toxic GTFe, which are nontoxic and has degradative potential for organic compounds. These findings suggest low ecotoxicological risks and suitability of this green-synthesized FeNPs for environmental remediation purposes.

Keywords: Iron nanoparticles, Green tea, Ecotoxicity, Remediation, Malachite green

For Table of Contents Use Only

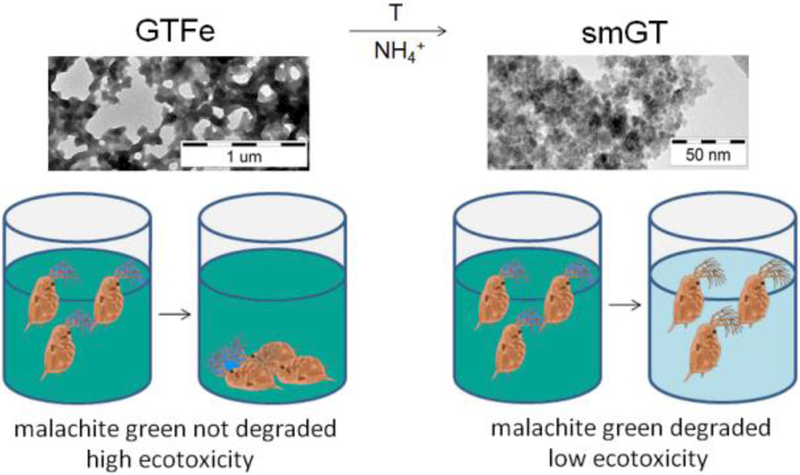

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, iron-based nanoparticles (FeNPs) have been attracting a great deal of attention because of their special properties such as enhanced surface area and reactivity compared to otherwise identical but larger particles thus enabling their multidisciplinary applications.1–3 The traditional synthesis method of FeNPs entails the reduction of ferric or ferrous salts with sodium borohydride (NaBH4)4 where hazardous waste is produced, leading to environmental and medical issues. The synthesis of such materials using environmentally friendly and biocompatible reagents could decrease the toxicity of the resulting materials and the environmental impact of the by-products.5 In this regard, an alternative approach based on incorporation of green chemistry principles has been used. This relatively new, cost-effective, and environment-friendly approach can be performed at ambient temperature and pressure, free of hazardous agents and toxic by-products.2 The main advantage of this method is the use of biorenewable natural products that, in some cases, are considered wastes, e.g., fruit peels or tree leaves. Furthermore, these components act as both dispersive and capping agent which delays the agglomeration process and enhances the stability of FeNPs and prolongs their reactivity.6 Recently, FeNPs have been synthesized using various plant extracts such as Terminalia chebula7, sorghum bran8, orange peels9, Eucalyptus globules10, Camellia sinensis11, and many others12, 13. FeNPs can be used for a wide range of different applications, including catalysis, biomedicine, magnetic bioseparation, electronics, environmental remediation, and water treatment.2, 14, 15 FeNPs can help eliminate various aqueous contaminants including dyes3, 6, 8, heavy metals9, 11, chlorinated compounds16–18 and pharmaceuticals19.

Despite intensive development in nanotechnology, the adverse effects of nanomaterials are still relatively unknown; some FeNPs used in remediation come into direct contact with the environment. However, their ecotoxicological properties are hardly understood and even the ecotoxicity of green synthesized iron oxides NPs have scarcely been investigated. Therefore, in this study, we have synthesized two green tea FeNPs, characterized them using TEM, DLS, XRD, and Mössbauer spectroscopy, and determined their toxicity to different trophic levels of organisms using a battery of ecotoxicological bioassays. The practicability of their use for remediation purposes was investigated using malachite green (MG) as a model organic contaminant.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

MATERIALS AND CHEMICALS

Iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, p.a.) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie (Steinheim, Germany). Ammonium hydroxide solution (p.a., 25 %) was obtained from P-LAB, Czech Republic. Tea extract was prepared from green tea leaves purchased from a local market. Malachite green was obtained from LACHEMA, Czech Republic. All chemicals were used without further purification.

PREPARATION

Procedure of the synthesis Fe-polyphenols complex

The synthesis of iron-based nanoparticles using green tea extract (GTFe) was performed according to the protocol described by Nadagouda et al. (2010)20, with a minor modification of maintaining the reaction under a nitrogen atmosphere. Briefly, tea extract was prepared by adding 4.0 g of tea powder to 200 mL hot water (just after boiling). The extract was allowed to cool down to room temperature under magnetic stirring and vacuum–filtered. Separately, a solution of 2.5M Fe(NO3)3·9H2O was prepared, and both solutions were then bubbled with nitrogen gas for 1 h. Subsequently, green tea synthesized Fe-based nanoparticles were prepared by injecting 20 mL 2.5 M Fe(NO3)3·9H2O to green tea extract under a nitrogen atmosphere. The reaction continued for 24 hours, and the product was stored at 4 °C.

Preparation of magnetic nanoparticles from Fe-polyphenol complex

The prepared solution containing GTFe complex was used for the preparation of magnetic nanoparticles. 100 mL of GTFe solution was supplemented with 100 mL of deionized water, and 20 mL of 25% ammonia solution was added. The reaction mixture was placed into a water bath incubated at 80 °C. The reaction was performed at 80 °C while being mechanically stirred (300 rpm) for 20 min. The ensuing green tea extract-stabilized superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (smGT) were washed three times with deionized water.

CHARACTERIZATION

Material characterization

Both morphological and size characteristics were analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). TEM images were obtained using electron microscope JEOL JEM–2010 operating at 160 kV with a point–to–point resolution of 1.9 Å. For all measurements, a drop of a very dilute dispersion was placed on the copper grid with holey carbon film and subsequently allowed to dry under vacuum at room temperature.

Thermogravimetric analysis was performed by a thermal analyzer STA 449 C Jupiter (Netzsch Instrument). Hydrodynamic diameter (DH) and zeta potential values (ζp) of cMNPs were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) method using the instrument Malvern Zetasizer Nano (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK). The iron content in the solution was determined by a protocol of the ferrozine assay described by Viollier.21

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns of Fe-based samples were recorded on PANalytical X´Pert PRO MPD diffractometer in Bragg-Brentano geometry, equipped with an iron-filtered CoKα radiation source (λ = 0.179 nm) at 40 kV/30 mA, an X´Celerator detector, programmable divergence and diffracted beam anti-scatter slits. Generally, 200 μL of suspension was dropped on a zero-background single-crystal Si slide, allowed to dry under vacuum at room temperature (RT) and scanned in continuous mode (resolution of 0.017° 2 Theta, scan speed of 0.008° 2 Theta per second, 2 Theta range from 20° to 105°) under ambient conditions. The commercially available standards SRM640 (Si) and SRM660 (LaB6) from NIST were used for the evaluation of line positions and instrumental line broadening, respectively. The acquired patterns were processed using X´Pert HighScore Plus software (PANalytical, The Netherlands), in combination with PDF-4+ and ICSD databases.

Transmission 57Fe Mössbauer spectra of the studied samples were recorded in a constant acceleration mode employing a Mössbauer spectrometer based on virtual instrumentation technique22, 23 and equipped with a 50 mCi 57Co(Rh) source of γ-rays radiation. The measured 57Fe Mössbauer spectra were evaluated using the MossWinn software program; prior to fitting, the signal-to-noise ratio was enhanced with the statistical procedure developed by Prochazka et al.24 and, at the same time, with the mathematical routines incorporated in the Mosswinn software package. The isomer shift values were referred to α-Fe foil at room temperature. The nature of Fe phase in the solid smGT sample was determined by a zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer experiment at room temperature and by a low-temperature (5 K) measurement in the external magnetic field (5 T) with a parallel orientation to γ-rays in the Spectromag cryomagnetic system (Oxford Instruments). The valence state of Fe presented in the GTFe sample at different pH values (adjusted to pH = 3 and pH = 7 by 10 M NaOH solution) was identified by zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy measurements at a temperature of 100 K. For these experiments, the reaction was stopped by transferring 200 μL of the sample into pre-frozen (liquid nitrogen) Mössbauer cuvettes. The samples were then immediately stored at – 80 °C to protect them against possible oxidation.

ECOTOXICOLOGICAL BIOASSAYS

Bacterial growth

The Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli (strain CCM 3954) and the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis (CCM 1999), both provided by the Czech Collection of Microorganisms, Brno, Czech Republic, were continuously cultivated in a liquid Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB) medium under 37 °C as described previously.25 For experiments, bacteria were diluted to final control concentration approximately 103 CFU/ml in a minimal Davis medium (MD). MD medium was prepared according to Lyon et al., (2006)26 while the concentration of potassium phosphate was reduced by 90 %27, although previous research has shown that other NPs precipitate out of suspension in media containing high phosphate concentrations.28 The antibacterial effect was first evaluated after both 10 min and then after 3 h of bacterial exposure to GTFe and smGT in MD medium. Tryptone Soya Agar plates were inoculated by 100 µL of each sample or its serial dilution in two replicates and cultivated overnight at 37 °C. After that, the number of colony-forming units (CFU) was counted, and the culturability of bacteria was determined.

Flash test

Freeze-dried Gram-negative marine luminescent bacteria Vibrio fischeri NRRL B-11177 was purchased from the Institute of Microbiology, The Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czech Republic. Bacteria were reconstituted according to ISO 11348–329 in ice-cold 2% NaCl and kept on ice. Prior to testing (30 min before experiment), aliquots of bacterial suspension were diluted in 2% NaCl and tempered in a 15°C water bath. Assays were performed in white 96-well plates.30 Inhibition of natural bioluminescence was determined by Luminoscan Ascent luminometer (Thermo) equipped with computer-controlled injectors. Bacteria suspension was injected into the well with NPs solution, and immediate luminescence (2 s) was compared with the signal after 30 s to calculate luminescence inhibition.

Acute toxicity test with algae and cyanobacterium

The growth assays with the unicellular green alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata and cyanobacterium Synechococcus nidulans (both cultures were obtained from Algal Culture Collection CCALA, Třeboň, Czech Republic) were performed according to ISO 869231 in transparent 96-well microplates with a sample volume of 250 µL per well with three replicates for each concentration and control. The initial concentration was 50,000 cells per mL and 200,000 cells per mL in 50% ZBB medium for alga and cyanobacterium, respectively. ZBB growth medium, i.e., a 1 : 1 mixture of ZEHNDER medium32 (Z) and Bold’s Basal medium33 (BB) diluted to 50 % with distilled water, was used as a testing medium, in which both cyanobacteria and algae reach sufficient and comparable growth rate.34 Alga and cyanobacterium were exposed to the FeNPs for 72 h at 24 ± 1 °C under continuous illumination (90 µmol m−2 s−1) by fluorescent lamps (Phillips, TLD 36 W/33) and the growth rate was evaluated after 24, 48 and 72 h by in vivo fluorescence measurements with a microplate fluorescence reader GENios (Tecan, Switzerland). Inhibition of growth in different concentrations of FeNPs was used as the end point when determining the EC50 and EC20.

Seed germination test

The phytotoxicity of FeNPs was evaluated by the seed germination technique. Seeds of Sinapis alba were placed in Petri dishes (10 seeds per dish) with a disc of filter paper on the bottom and 5 mL of the exposure solutions and control in ISO 6341 media in 5 replicates per concentration. The seed germination, root elongation and dry root weight (biomass was dried at 105 °C for 5 h to reach the constant weight) were determined after 72 h incubation at 24 ± 1 °C in the dark and EC50, EC20, and the germination index (GI) were counted. The GI combines information about seed germination and root growth and therefore reflects the toxicity more completely35 and was calculated according to the standard method.36

Lemna minor bioassay

Duckweed (L. minor) toxicity tests were designed according to the international standard method ISO 2007937. The testing was performed in 250 mL flasks with darkened bottoms containing 100 mL of the testing medium (Steinberg medium) in triplicate for each concentration and control, with the initial number of 10 fronds per flask. After 7 days exposition at 24 ± 1 °C under continuous illumination by cool white fluorescent lamps (Phillips, TLD 36 W/33) with the intensity of 100 µmol m−2 s−1 were counted the frond numbers as the endpoints to the growth inhibition when determining EC50 and EC20 values.

Daphnia magna bioassay

D. magna bioassay was performed according to the international standard method ISO 634138. Ten randomly selected neonates of D. magna from continuous laboratory breeding, less than 24 h old, were transferred into separate polystyrene plates containing 10 mL of the standard exposure solution ISO 6341 in four replicates per concentration and control with no food present. The temperature was maintained at 20 ± 2 °C during the exposure in the dark. Daphnids were inspected after 24 and 48 h of exposure. The toxicity of FeNPs was expressed in terms of the effective concentrations (EC50 and EC20) required to cause the immobilization of 50 % and 20 % of individuals after 24 and 48 h of interaction, respectively.

Ostracodtoxkit

For a subchronic direct contact toxicity tests for freshwater sediments were used commercially available OSTRACODTOXKIT F microbiotests (MicroBioTests Inc., Belgium) with the benthic ostracod crustacean Heterocypris incongruens according to ISO 1437139. All experiments were performed in duplicates. At the end of the exposure period, the mortality using EC50 and EC20 and growth inhibition were determined. The length measurement was carried out using of an SZX7 stereo microscope (Olympus). The growth inhibition test was determined only for concentrations with less than 30% mortality. These experiments were also conducted for ´aged NPs´, where tested NPs added to the reference sediment were left to age in the dark at 24 ± 1 °C for 7 days before testing.

Statistical data analysis

All toxicity tests were conducted at least in triplicate. The statistical analysis was performed using the software GraphPad™ Prism (GraphPad Software). Concentrations of NPs suspensions that caused 50% and 20% inhibition of measured parameters (EC50 and EC20, respectively) were derived from the four-parametric logistic curve using nonlinear regression analysis along with the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The growth inhibition of H. incongruens, i.e., the statistically significant difference between control and tested concentrations of NPs, was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett´s multiple comparisons test. Differences were statistically significant when p < 0.05.

DEGRADATION OF MALACHITE GREEN

The degradation experiments were carried out using 10 mL of various concentrations of FeNPs added to 10 mL of aqueous solution containing 50 mg/L of MG without pH adjustment. Parallel blank experiments were carried out under the same conditions with just smGT and GTFe in MilliQ water at final concentrations 500, 250, 125, 62.5 and 31.25 mg Fe/L. Mixed solutions were stirred on a rotary shaker (200 rpm at room temperature) for 10, 30 and 60 minutes. Then the mixtures and blanks were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was measured for the residual concentration of MG. The absorbance was measured using DR2800 Spectrophotometer at the wavelength of MG absorption maximum (λ = 617 nm). The residual concentrations were determined using calibration curve for MG after deducting the blank value. These experiments were carried out in duplicate.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CHARACTERIZATION OF FeNPs

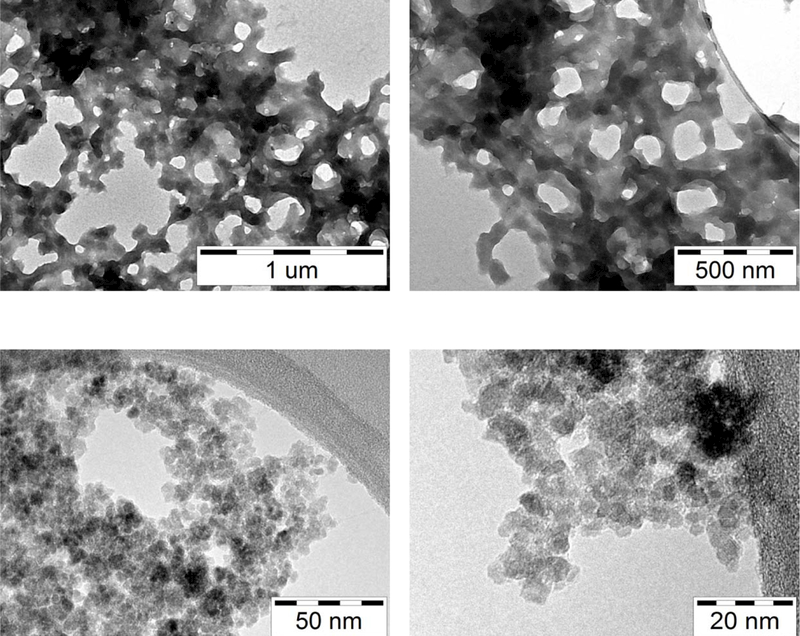

Morphology and size of GTFe and smGT nanoparticles were analyzed by TEM technique (see Figure 1). The recorded TEM micrographs show that GTFe sample (taken at the 24th hour) is formed by an extended network of Fe-polyphenols complex (see Figure 1a,b) whereas nanoparticles prepared from this complex (smGT) are less than 5 nm sized (see Figure 1c,d).

Figure 1:

TEM imagines of (a, b) iron-polyphenols complex GTFe and (c, d) smGT nanoparticles.

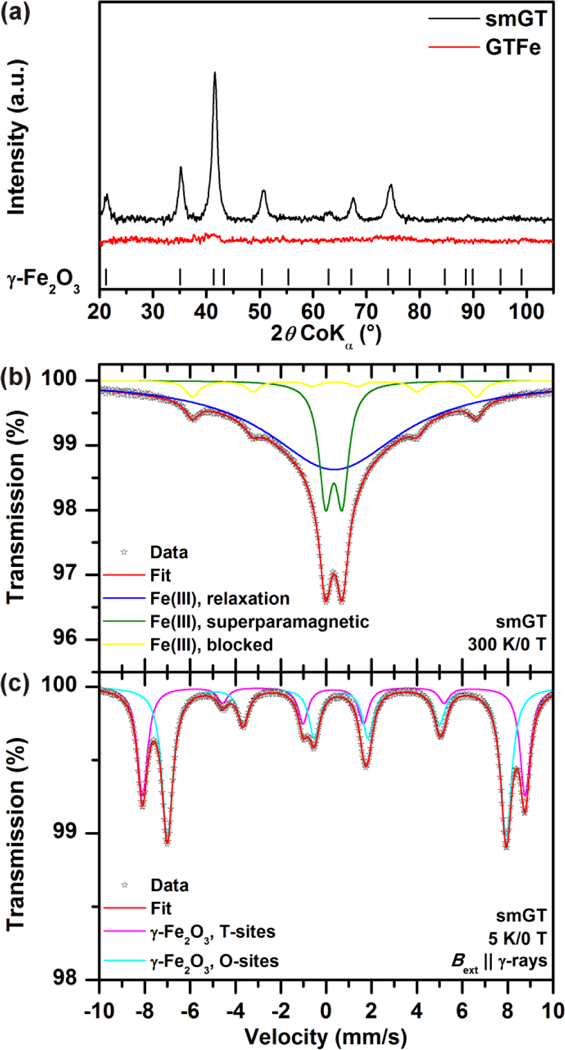

XRD patterns of GTFe and smGT are shown in Figure 2a. The pattern of GTFe sample lacks distinction of diffraction lines, suggesting that the GTFe complex is amorphous in nature, which was also described before by Markova et al. (2014)40. The smGT nanoparticles are identified from the pattern as nanocrystalline γ-Fe2O3 with a mean X-ray coherence length (MCL) equal to 13 nm and lattice parameter a = 0.8356 nm, which is in agreement with reported values for γ-Fe2O3 in PDF-4+ database (JCPDS card No. 01–078-6916).

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns of GTFe complex and smGT nanoparticles. (b, c) 57Fe Mössbauer spectra of the smGT sample recorded at room temperature and at a temperature of 5 K and in an external magnetic field of 5 T.

In order to precisely identify the nature of iron oxide in the smGT sample, 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy was employed. The room-temperature 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of the smGT sample can be well fitted with three spectral components, i.e., a singlet, doublet, and sextet (see Figure 2b); the values of the Mössbauer hyperfine parameters derived for all the subspectra are listed in Table S1. The values of the isomer shift (δ) of all the three spectral components are identical implying that they can be ascribed to one particular phase of iron oxide; the δ-values lie in the interval typical for Fe(III) in S = 5/2.41 The coexistence of singlet, doublet, and sextet reflect the particle size distribution in the smGT sample.42 In particular, the doublet can be attributed to the smallest nanoparticles, the superspins of which show superparamagnetic fluctuations among the directions favored by the particle’s magnetic anisotropy. For such a size fraction of nanoparticles, the relaxation time determining the period of superspin’s reversal is shorter than the characteristic measuring time (τm) of the Mössbauer technique (~10–8 s). The singlet then corresponds to the sizes of the nanoparticles with the relaxation time in the order of τm, indicating onset of superparamagnetic fluctuations at room temperature. For the largest nanoparticles or nanoparticle’s aggregates (due to possible magnetic interparticle interactions), the relaxation time exceeds τm, locking thus their superspins in the particular direction of the particle’s magnetic anisotropy. In other words, such nanoparticles or their aggregates are said to be magnetically blocked, which is manifested by the emergence of the sextet component with a non-zero hyperfine magnetic field (Bhf). Considering the spectral area of individual spectral components, most of the nanoparticles are in a superparamagnetic regime at room temperature from the viewpoint of the Mössbauer spectroscopy technique. Upon lowering the temperature to 5 K and placing the sample to an external magnetic field of 5 T oriented in a parallel direction to the propagation of γ-rays, the superspins of all the iron(III) oxide nanoparticles present in the system get magnetically blocked and the 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum is split into two spectral components (see Figure 2c and Table S1). The two-sextet pattern of in-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum and respective values of the Mössbauer hyperfine parameters are characteristic of γ-Fe2O3;42 the sextet with the higher value of effective hyperfine magnetic field (Beff) and lower value of δ belong to the tetrahedral cation sites in the γ-Fe2O3 crystal structure while the sextet with a lower Beff and higher δ corresponds to the octahedral cation sites in the γ-Fe2O3 crystal structure. Note that the ratio of the spectral area of the octahedral-to-tetrahedral sextet is, within the experimental error of the Mössbauer technique, very close to 1.66:1 which is expected for stoichiometric γ-Fe2O3.42 As no other spectral components were detected in the low-temperature in-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of the smGT sample, the system is thus composed of nanoparticles of solely γ-Fe2O3 nature, in a perfect agreement with the analysis of the XRD pattern. However, the intensities of the second and the fifth resonant lines for both sextets did not vanish as expected for a perfectly collinear ferrimagnetic structure of γ-Fe2O3.42 Such a behavior is typical for nanocrystalline γ-Fe2O3 with sizes below 15 nm when the spin canting phenomenon emerges as a result of finite-size and surface effects and magnetic interparticle interactions.43

The hydrodynamic diameter (see Table S2) revealed the nanoparticulate character of both GT extract and GTFe complex. The hydrodynamic diameter of 299 ± 46 nm of GT sample indicates that polyphenols form nanosized formations in a water environment. After the formation of a complex between Fe and polyphenols, the hydrodynamic diameter decreased to 215 ± 25 nm. Moreover, the negative zeta potential of GT (- 21.3 ± 3.2 mV) increases to 10.7 ± 1.5 mV after polyphenols form the complex with Fe ions. This significant change of zeta potential can be attributed to the interaction of hydroxyl groups (which gives a negative charge to GT polyphenols) with iron ions. The hydrodynamic diameter of smGT nanoparticles is 300 ± 32 nm, and its zeta potential is - 35.7 ± 0.4 mV, which suggests the loading of polyphenols on the nanoparticles surface.

ECOTOXICOLOGICAL BIOASSAYS

The results of ecotoxicological bioassays expressed as EC50 and EC20 values showing the effects of smGT and GTFe to nine representative organisms are summarized in Table S3. smGT shows low toxicity for almost all tested organisms with EC50 higher than 1 g Fe/L except algae (P. subcapitata), cyanobacterium (S. nidulans), and sediment crustacean (H. incongruens) with EC50 values 32.3, 42.9 and 454.0 mg Fe/L, respectively. This reaction is probably caused by polyphenolic substances as such, as already published by Zhu et al., (2010)44, who found that pyrogallic acid (2.97 mg/L) and gallic acid (2.65 mg/L) caused significant reductions of photosystem (PSII) and the whole electron transport chain activities of cyanobacterium M. aeruginosa. Algae and cyanobacterium were the most sensitive test organisms also for the second tested substance, GTFe, which exhibits higher toxicity than smGT in all cases. EC50 values for S. nidulans and P. subcapitata followed by L. minor were detected 5.0, 5.4, and 9.4 mg Fe/L, respectively. The lowest toxicity was observed for H. incongruens (229.8 mg Fe/L) followed by representatives of all three bacteria.

Gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis was more sensitive to GTFe exposition than Gram-negative bacterium E. coli. Elevations in toxic effect, expressed as EC50 values, have been observed for both bacteria when extending the exposure time to 3 hours from 182.6 to 155.9 and from 84.3 to 77.6 mg Fe/L for E. coli and B. subtilis, respectively. This is in agreement with some previously published reports that showed that Gram-positive B. subtilis was more susceptible to NPs than Gram-negative E. coli45, although B. subtilis is generally considered to be less sensitive to the effects of nanomaterials due to its cell wall structure and ability to form spores. GTFe exhibits relatively high toxicity for V. fisheri (57.0 mg Fe/L), which proved that the bioluminescence endpoint is more sensitive than the growth of bacterial populations.

D. magna was more responsive to GTFe exposition than H. incongruens, sediment crustacean, with EC50 values 18.7 and 18.0 mg Fe/L for 24 h and 48 h exposition, respectively, probably due to the direct effect of GTFe on pH of media, where artificial sediments have a higher buffer capacity. Both tested FeNPs exhibited toxicity for H. incongruens with EC50 values 454.0 and 229.8 mg Fe/L for smGT and GTFe, respectively. There was no statistically significant growth inhibition observed in both cases. Experiments with the ´aged NPs´, i.e., smGT and GTFe left for 7 days in testing conditions before organisms were added, showed reduced toxicity and the shift of the EC50 values to more than 1 g Fe/L and 348.4 mg Fe/L for smGT and GTFe, respectively.

In our study, H. incongruens was the least sensitive test organism, but mortality was observed for both GTFe and smGT. One explanation of FeNPs toxicity is the indirect effect through food depletion.46 This study shows that the 72-h EC50 values for P. subcapitata were one to two orders of magnitude lower than for ostracods. Bosnir et al., (2013)47 showed that sensitivity of P. subcapitata and Scenedesmus subcapitatus to iron is comparable. Therefore, we assume that Scenedesmus sp. used as feeding organism in Ostracodtoxkit was also affected by high concentrations of FeNPs, which exceeded the toxicity values for P. subcapitata by two orders for reported ostracods EC50 values.47 Another hypothesis to explain mortality is FeNPs absorption onto algal cell surface and adhesion of NPs aggregates to the exoskeleton of crustaceans, which may cause physical effects, loss of mobility48, and hinder the search for food when covered by a layer of settled FeNPs (Figure S1).

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one publication dealing with the toxicity of FeNPs on the ostracod H. incongruens as a freshwater organism and sediment dweller, which is considered an important food source for fish larvae.49 They studied the ecotoxicological effect of nano-sized zero-valent iron (nZVI) used for DDT degradation in soil; the mortality of ostracods expressed as LC50 was 77 mg/L and 13 mg/L for nZVI and Fe(II) (as FeSO4), respectively. Therefore, they presume, that the negative effect of nZVI on ostracod mortality is indirect, due to its oxidation and release of Fe(II) ions by the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Duckweed (L. minor), a free-floating freshwater monocot, was the third most sensitive tested organism with EC50 of 9.4 mg Fe/L for GTFe, after alga and cyanobacteria. In contrast, smGT showed no adverse effect up to highest tested concentration. nZVI showed 50% growth inhibition 271.4 and 398.3 mg/L as a frond number and dry weight, respectively.50 Superparamagnetic Fe3O4 NPs in a concentration of 400 mg/L showed 39% inhibitory response for a specific growth rate of Lemna gibba based on frond number.51

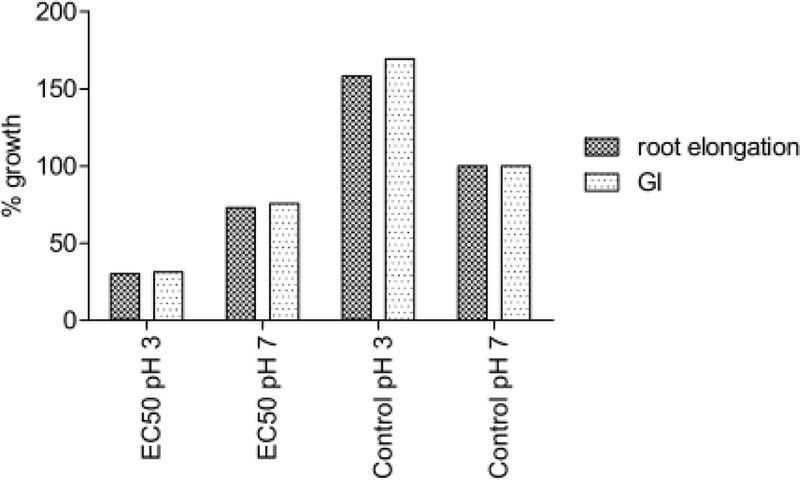

smGT did not affect S. alba seed germination and root elongation at all tested concentrations. GI in a concentration of 1 g Fe/L was 103.4 ± 28.9 %. GTFe showed toxicity for all tested endpoints with EC50 values 48.5, 51.8 and 45.9 mg Fe/L for root length, dry root weight and GI, respectively. Complete inhibition of germination was observed at 333.3 – 1000 mg Fe/L.

The phytotoxicity effect described by GI comprises both development stages: germination and seedling elongation when root elongation and dry weight are used to assess the exposure effect. The root elongation can be an indicator of the presence of non-acute toxicological effects, for example as an avoidance mechanism to a stress factor. For instance, in a study of Barrena et al.,35 the values of root weight were significantly higher than the elongation for Fe3O4 NPs, whereas Au NPs root growth was mainly due to elongation. Therefore in some cases, the root elongation can be more sensitive than GI when the toxicity directly affects the root development. The root and shoot growth were more sensitive indicators than the germination percentage as corroborated by the work of El-Temsah and Joner (2012)15, who studied the inhibitory effect of nZVI. For this reason, it is recommended to present both the root length and the GI results.36

Fe3O4 NPs in a concentration of 320 mg/L did not exhibit any statistically significant toxicity in germination test with cucumber (Cucumis sativus) seeds. Tomato (Lycopersicom esculentum) seeds were inhibited to 61 ± 3 % and 66 ± 4 % of control GI and root elongation, respectively. Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) showed 11 ± 4% decrease in root elongation compared to control.36 Inhibitory effects on root growth of flax (Linum usitatissimum), ryegrass (Lolium perenne) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) could be seen at 250 mg/L nZVI and a complete inhibition of germination was observed at 1 – 2 g/L nZVI.15 Barrena et al., (2009)35 concluded that the toxic effects observed in NPs could be due to the presence of solvents used for the preparation and stabilization of NPs suspension and this effect might be higher than the toxicity of NPs themselves. Fe3O4 NPs increased the oxidative stress in ryegrass more than bulk Fe3O4 and the contribution of the coating agent to this effect can be assumed.52

EFFECT OF pH ON THE TOXICITY OF GTFe

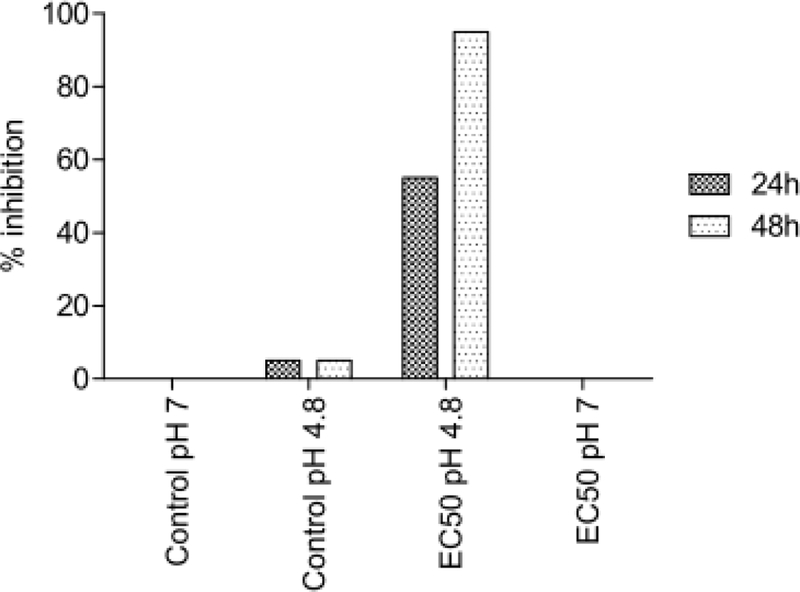

All ecotoxicological bioassays were conducted without pH adjustment. Meanwhile smGT in a concentration 1 g Fe/L showed pH around 8, GTFe showed high acidity in all six tested media (see Table S4) and for most of the tested organisms were EC50 values obtained in pH below 3 except for the most sensitive tested organisms S. nidulans, P. subcapitata (pH 6) and D. magna (pH 4.8).

The assumption that GTFe´s acidity is responsible for its increased toxicity was not confirmed. The experiments with D. magna and S. alba showed that pH adjustment of the media to the EC50 concentration value of GTFe solution alone did not cause significant inhibition (see Figure 3 and 4). On the other hand, adjustment of GTFe pH to neutral caused substantial aggregation that could be discerned by naked-eye visible change of structure from dark dispersion to rusty clumps and its toxicity decreased.

Figure 3:

pH influence to S. alba growth.

Figure 4:

pH influence to D. magna inhibition.

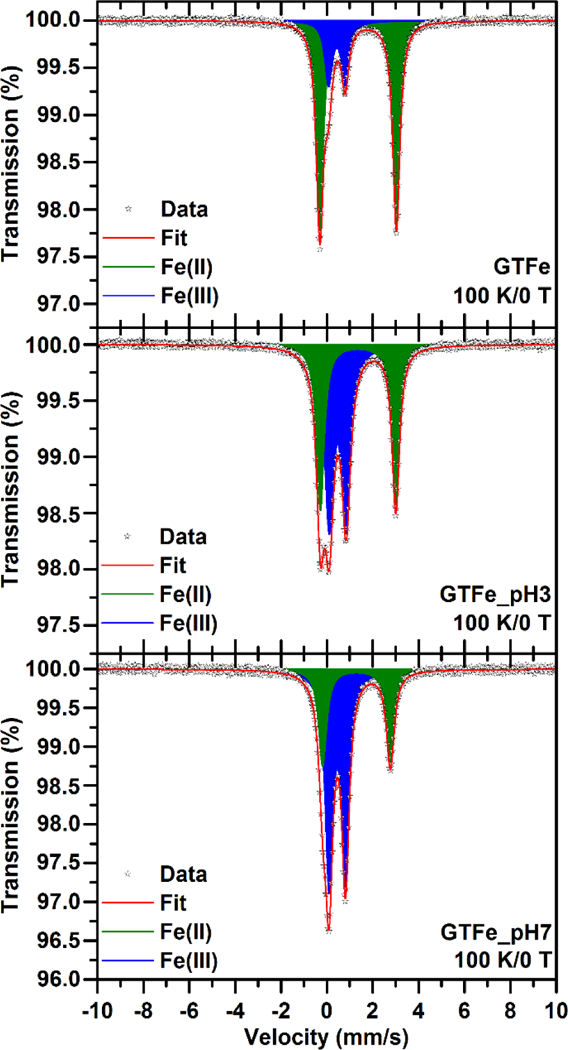

The buffering capacity of used media can influence Fe(II) and Fe(III) composition of the sample during ecotoxicological experiments. The pH of the GTFe solution was found to be extremely acidic, i.e., pH 2.1, which is caused by the presence of NO33- anions in the sample (originating from dissociation of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O). The pH of tested media (the growth media for tested organisms) ranged between 5.3 and 8.1 (Table S4). Therefore, Fe(II) and Fe(III) contents of GTFe complex were investigated in the original sample (GTFe) and at pH 3 (GTFe_pH3) and pH 7 (GTFe_pH7). The samples were incubated at the conditions mentioned above for 1 hour and then stored at 193 K. The low-temperature 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy revealed that pH of the GTFe solution substantially influences the Fe(II): Fe(III) ratio (see Figure 5). Whereas the spectral percentage contents of Fe(II) and Fe(III) in the original sample (pH = 2.1) were found to be 77 and 23%, respectively (see Table S5), the adjustment of pH to 3 led to partial oxidation of Fe(II) resulted in the spectral percentage contents of Fe(II) and Fe(III) to be 45 and 55%, respectively (see Table S5). Another addition of NaOH to adjust pH of the GTFe solution to 7 resulted in the further oxidation of Fe(II); the spectral percentage contents of Fe(II) and Fe(III) were determined to be 32 and 68%, respectively (see Table S5). This pH-dependent oxidation of Fe(II) in GTFe can also be affected by the composition of the growth media used and by incubation time. Nevertheless, these factors have not been studied (due to their complexity); however, it should be mentioned that the interaction between media or even real environments and GTFe complex can result in partial or even total oxidation of Fe(II) to Fe(III) which can be caused not only by pH.

Figure 5:

57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of the GTFe (top), GTFe_pH3 (middle), and GTFe_pH7 (bottom) sample, recorded at a temperature of 100 K.

DEGRADATION OF MALACHITE GREEN

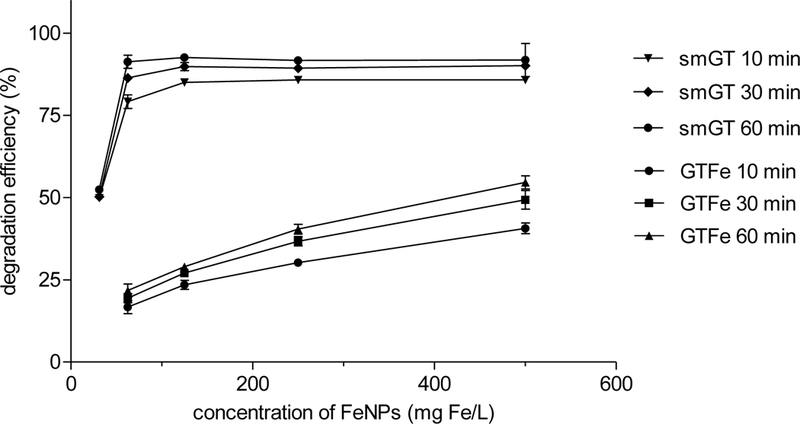

To evaluate the reactivity of the smGT and GTFe, the degradation of MG in aqueous solution with an initial concentration of 25 mg/L is shown in Figure 6, where the highest MG removal efficiency of 92.6 % using 125 mg Fe/L smGT and 54.6 % using 500 mg Fe/L GTFe after 60 minutes was observed. Before the treatment, MG shows maximum absorption at 617 nm, which was significantly reduced when the different concentration of FeNPs was added to the solution. These changes indicate that MG was significantly degraded by smGT and GTFe as it was proved earlier in the case of GTFe by Weng et al., (2013) and Abbassi et al., (2013).53, 54

Figure 6:

Malachite green degradation efficiency of smGT and GTFe.

GTFe showed lower MG degradation efficiency than smGT. In the highest tested concentration of GTFe (500 mg Fe/L), only 54.6% removal efficiency after 60 minutes was achieved. This is similar to the efficiency of smGT in a concentration of only 31.25 mg Fe/L, which was 52.4 % (see Figure 6).

No pH adjustment was performed during the decolorization experiments. The pH of the 25 mg/L MG solution was 4.7 and the pH of the smGT itself was about 9, slightly higher than in the admixture with MG except for the lowest tested concentration where pH dropped to 7.3 in 60 minutes (see Figure S2). GTFe caused pH around 3 in the lowest tested concentration and slowly decreased to 2.3 in the highest tested concentration, without significant effect of time exposure to MG.

The conductivity was concentration dependent for GTFe and increased from 0.7 to 4.4 mS for 61.5 to 500 mg Fe/L GTFe, respectively. smGT showed low conductivity, in the lowest tested concentration comparable with MG itself (0.3 mS), and with increasing concentration rose up to 0.15 mS (see Figure S3). This is in agreement with the nature of the tested FeNPs. Meanwhile, smGT are nanoparticles that were removed from the solution by centrifugation of the tested samples, whereas GTFe is a complex of Fe ions and green tea polyphenols which remains in solution and increases its conductivity.

The effect of the smGT dosage indicates enhanced removal efficiency of MG with increasing smGT concentration; 49.9% removal efficiency was achieved after 10 minutes when smGT was 31.25 mg Fe/L and increased to maximal efficiency in a concentration 125 mg Fe/L and then remained relatively constant up to highest tested concentration 500 mg Fe/L. The removal efficiency of MG also improved as contact time increased from 85 % to 92.6 % for 125 mg Fe/L in 10 and 60 minutes, respectively. This is a significant improvement in comparison with the previous reports of Weng et al.,53 where 100% removal efficiency was achieved with 1.12 g/L of GTFe, and Abbassi et al.,54 where the optimal removal efficiency of 95.16 % was obtained with initial MG concentration of 162.6 mg/L, and 3.6 g/L of clay supported FeNPs.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we have prepared and characterized the ecotoxicological properties of two green synthesized FeNPs using green tea polyphenols. The results showed that the ecotoxicity of GTFe is approximately one to two orders of magnitude higher than the newly developed smGT. Superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs prepared from GTFe showed no negative effect on almost all tested organisms, except for algae and cyanobacteria, and simultaneously enhanced the catalytic properties of GTFe complex. Consequently, there is a great potential for this FeNPs to be used for environmental remediation which was confirmed with dye degradation experiments. Further studies are needed to confirm smGT applicability to the degradation of other types of pollutants and its use in natural conditions, but the low ecotoxicity of this novel compound promises broad applicability to water treatment technologies.

Supplementary Material

SYNOPSIS.

Newly green-synthetized iron nanoparticles showed superior properties compared to its parent complex indicating its enhanced potential for environmental remediation applications.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: This research was supported by the RECETOX Research Infrastructure (LM2015051 and CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_013/0001761). The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under Project No. LO1305, the support by the Operational Programme Research, Development and Education – European Regional Development Fund, Project No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000754 of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, the assistance provided by the Research Infrastructure NanoEnviCz supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic under Project No. LM2015073.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors have read and reviewed the paper and have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Disclaimer: The research presented was not performed or funded by EPA and was not subject to EPA’s quality system requirements. The views expressed in this [article/presentation/poster] are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views or the policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iravani S, Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Green Chemistry 2011, 13 (10), 2638–2650. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seabra AB; Haddad P; Duran N, Biogenic synthesis of nanostructured iron compounds: applications and perspectives. Iet Nanobiotechnology 2013, 7 (3), 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alagiri M; Hamid SBA, Green synthesis of alpha-Fe2O3 nanoparticles for photocatalytic application. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Electronics 2014, 25 (8), 3572–3577. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang CB; Zhang WX, Synthesizing nanoscale iron particles for rapid and complete dechlorination of TCE and PCBs. Environmental Science & Technology 1997, 31 (7), 2154–2156. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kharissova OV; Rasika Dias HV; Kharisov BI; Olvera Perez B; Jimenez Perez VM, The greener synthesis of nanoparticles. Trends in Biotechnology 2013, 31 (4), 240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoag GE; Collins JB; Holcomb JL; Hoag JR; Nadagouda MN; Varma RS, Degradation of bromothymol blue by ‘greener’ nano-scale zero-valent iron synthesized using tea polyphenols. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2009, 19 (45), 8671–8677. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar KM; Mandal BK; Kumar KS; Reddy PS; Sreedhar B, Biobased green method to synthesise palladium and iron nanoparticles using Terminalia chebula aqueous extract. Spectrochimica Acta Part a-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2013, 102, 128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Njagi EC; Huang H; Stafford L; Genuino H; Galindo HM; Collins JB; Hoag GE; Suib SL, Biosynthesis of Iron and Silver Nanoparticles at Room Temperature Using Aqueous Sorghum Bran Extracts. Langmuir 2011, 27 (1), 264–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Tellez G; Balderas-Hernandez P; Barrera-Diaz CE; Vilchis-Nestor AR; Roa-Morales G; Bilyeu B , Green Method to Form Iron Oxide Nanorods in Orange Peels for Chromium(VI) Reduction. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2013, 13 (3), 2354–2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madhavi V; Prasad TNVKV; Reddy AVB; Reddy BR; Madhavi G, Application of phytogenic zerovalent iron nanoparticles in the adsorption of hexavalent chromium. Spectrochimica Acta Part a-Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2013, 116, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chrysochoou M; Johnston CP; Dahal G, A comparative evaluation of hexavalent chromium treatment in contaminated soil by calcium polysulfide and green-tea nanoscale zero-valent iron. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2012, 201, 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machado S; Pinto SL; Grosso JP; Nouws HPA; Albergaria JT; Delerue-Matos C, Green production of zero-valent iron nanoparticles using tree leaf extracts. Science of the Total Environment 2013, 445, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z; Fang C; Megharaj M, Characterization of Iron-Polyphenol Nanoparticles Synthesized by Three Plant Extracts and Their Fenton Oxidation of Azo Dye. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2014, 2 (4), 1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes RJ; van der Gast CJ; Riba O; Lehtovirta LE; Prosser JI; Dobson PJ; Thompson IP, The impact of zero-valent iron nanoparticles on a river water bacterial community. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, 184 (1–3), 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Temsah YS; Joner EJ, Impact of Fe and Ag nanoparticles on seed germination and differences in bioavailability during exposure in aqueous suspension and soil. Environmental Toxicology 2012, 27 (1), 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuang Y; Wang Q; Chen Z; Megharaj M; Naidu R, Heterogeneous Fenton-like oxidation of monochlorobenzene using green synthesis of iron nanoparticles. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2013, 410, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang T; Lin J; Chen Z; Megharaj M; Naidu R, Green synthesized iron nanoparticles by green tea and eucalyptus leaves extracts used for removal of nitrate in aqueous solution. Journal of Cleaner Production 2014, 83, 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smuleac V; Varma R; Sikdar S; Bhattacharyya D, Green synthesis of Fe and Fe/Pd bimetallic nanoparticles in membranes for reductive degradation of chlorinated organics. Journal of Membrane Science 2011, 379 (1–2), 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machado S; Stawinski W; Slonina P; Pinto AR; Grosso JP; Nouws HPA; Albergaria JT; Delerue-Matos C, Application of green zero-valent iron nanoparticles to the remediation of soils contaminated with ibuprofen. Science of the Total Environment 2013, 461, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nadagouda MN; Castle AB; Murdock RC; Hussain SM; Varma RS, In vitro biocompatibility of nanoscale zerovalent iron particles (NZVI) synthesized using tea polyphenols. Green Chemistry 2010, 12 (1), 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viollier E; Inglett PW; Hunter K; Roychoudhury AN; Van Cappellen P, The ferrozine method revisited: Fe(II)/Fe(III) determination in natural waters. Applied Geochemistry 2000, 15 (6), 785–790. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pechousek J; Jancik D; Frydrych J; Navarik J; Novak P In Setup of Mossbauer Spectrometers at RCPTM, 10th International Conference on Mossbauer Spectroscopy in Materials Science (MSMS), Olomouc, CZECH REPUBLIC, 2012, June 11–15, pp 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pechousek J; Prochazka R; Jancik D; Frydrych J; Mashlan M In Universal LabVIEW-powered Mossbauer spectrometer based on USB, PCI or PXI devices, International Conference on the Applications of the Mossbauer Effect, Vienna Univ Technol, Vienna, AUSTRIA, 2010, July 19–24, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prochazka R; Tucek P; Tucek J; Marek J; Mashlan M; Pechousek J, Statistical analysis and digital processing of the Mossbauer spectra. Measurement Science and Technology 2010, 21 (2). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikula P; Kalhotka L; Jancula D; Zezulka S; Korinkova R; Cerny J; Marsalek B; Toman P, Evaluation of antibacterial properties of novel phthalocyanines against Escherichia coli - Comparison of analytical methods. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B-Biology 2014, 138, 230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyon DY; Adams LK; Falkner JC; Alvarez PJJ, Antibacterial activity of fullerene water suspensions: Effects of preparation method and particle size. Environmental Science & Technology 2006, 40 (14), 4360–4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atlas RM, Handbook of Microbiological Media, Fourth Edition. CRC Press: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyon DY; Fortner JD; Sayes CM; Colvin VL; Hughes JB, Bacterial cell association and antimicrobial activity of a C-60 water suspension. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2005, 24 (11), 2757–2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ISO 11348–3 Water quality - Determination of the inhibitory effect of water samples on the light emission of Vibrio fischeri (Luminescent bacteria test) - Part 3: Method using freeze-dried bacteria. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blaha L; Hilscherova K; Cap T; Klanova J; Machat J; Zeman J; Holoubek I, KINETIC BACTERIAL BIOLUMINESCENCE ASSAY FOR CONTACT SEDIMENT TOXICITY TESTING: RELATIONSHIPS WITH THE MATRIX COMPOSITION AND CONTAMINATION. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2010, 29 (3), 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ISO 8692 Water quality - Fresh water algal inhibition test with Scenedesmus subspicatus and Selenastrum capricornutum. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staub R, Ernahrungsphysiologisch - autokologische Untersuchungen an der planktonische Blaulage Oscillatoria rubescens DC.(Study of nutrition physiology and autecology of planktic blue-green alga Oscillatoria rubescens DC.). Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Hydrologie: 1961; Vol. 23, pp 82–198. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bold HC, The morphology of Chlamydomonas chlamydogama, sp. nov. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club: 1949; Vol. 72, pp 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gregor J; Jancula D; Marsalek B, Growth assays with mixed cultures of cyanobacteria and algae assessed by in vivo fluorescence: One step closer to real ecosystems? Chemosphere 2008, 70 (10), 1873–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrena R; Casals E; Colon J; Font X; Sanchez A; Puntes V, Evaluation of the ecotoxicity of model nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2009, 75 (7), 850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Recillas S; Garcia A; Gonzalez E; Casals E; Puntes V; Sanchez A; Font X, Use of CeO2, TiO2 and Fe3O4 nanoparticles for the removal of lead from water Toxicity of nanoparticles and derived compounds. Desalination 2011, 277 (1–3), 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- 37.ISO 20079 Water quality - Determination of the toxic effect of water constituents and waste water on duckweed (Lemna minor) - Duckweed growth inhibition test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.ISO 6341 Water quality - Determination of the inhibition of the mobility of Daphnia magna Straus (Cladocera, Crustacea) - Acute toxicity test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.ISO 14371 Water quality - Determination of fresh water sediment toxicity to Heterocypris incongruens (Crustacea, Ostracoda). International Organization for Standardization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markova Z; Novak P; Kaslik J; Plachtova P; Brazdova M; Jancula D; Siskova KM; Machala L; Marsalek B; Zboril R; Varma R, Iron(II,III)-Polyphenol Complex Nanoparticles Derived from Green Tea with Remarkable Ecotoxicological Impact. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2014, 2 (7), 1674–1680. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutlich P; Bill E; Trautwein AX, Mossbauer Spectroscopy and Transition Metal Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications. Mossbauer Spectroscopy and Transition Metal Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications 2011, 1–568. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tucek J; Zboril R; Petridis D, Maghemite nanoparticles by view of Mossbauer spectroscopy. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 2006, 6 (4), 926–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dormann JL; Fiorani D; Tronc E, Magnetic relaxation in fine-particle systems. Advances in Chemical Physics , Vol 98 1997, 98, 283–494. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu JY; Liu BY; Wang J; Gao YN; Wu ZB, Study on the mechanism of allelopathic influence on cyanobacteria and chlorophytes by submerged macrophyte (Myriophyllum spicatum) and its secretion. Aquatic Toxicology 2010, 98 (2), 196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams LK; Lyon DY; Alvarez PJJ, Comparative eco-toxicity of nanoscale TiO2, SiO2, and ZnO water suspensions. Water Research 2006, 40 (19), 3527–3532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manzo S; Rocco A; Carotenuto R; Picione FD; Miglietta ML; Rametta G; Di Francia G, Investigation of ZnO nanoparticles’ ecotoxicological effects towards different soil organisms. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2011, 18 (5), 756–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bosnir J; Puntaric D; Cvetkovic Z; Pollak L; Barusic L; Klaric I; Miskulin M; Puntaric I; Puntaric E; Milosevic M, Effects of Magnesium, Chromium, Iron and Zinc from Food Supplements on Selected Aquatic Organisms. Collegium Antropologicum 2013, 37 (3), 965–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baun A; Hartmann NB; Grieger K; Kusk KO, Ecotoxicity of engineered nanoparticles to aquatic invertebrates: a brief review and recommendations for future toxicity testing. Ecotoxicology 2008, 17 (5), 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Temsah YS; Joner EJ, Effects of nano-sized zero-valent iron (nZVI) on DDT degradation in soil and its toxicity to collembola and ostracods. Chemosphere 2013, 92 (1), 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marsalek B; Jancula D; Marsalkova E; Mashlan M; Safarova K; Tucek J; Zboril R, Multimodal Action and Selective Toxicity of Zerovalent Iron Nanoparticles against Cyanobacteria. Environmental Science & Technology 2012, 46 (4), 2316–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barhoumi L; Oukarroum A; Ben Taher L; Smiri LS; Abdelmelek H; Dewez D, Effects of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles on Photosynthesis and Growth of the Aquatic Plant Lemna gibba. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 2015, 68 (3), 510–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miralles P; Church TL; Harris AT, Toxicity, Uptake, and Translocation of Engineered Nanomaterials in Vascular plants. Environmental Science & Technology 2012, 46 (17), 9224–9239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weng X; Huang L; Chen Z; Megharaj M; Naidu R, Synthesis of iron-based nanoparticles by green tea extract and their degradation of malachite. Industrial Crops and Products 2013, 51, 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abbassi R; Yadav AK; Kumar N; Huang S; Jaffe PR, Modeling and optimization of dye removal using “green” clay supported iron nano-particles. Ecological Engineering 2013, 61, 366–370. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.