Abstract

Objective

A limited understanding exists of the relationship between disability and older persons’ living arrangements in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). We examine the associations between living arrangements, disability, and gender for individuals older than 50 years in rural South Africa.

Method

Using the Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) survey and Agincourt Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) data, we explore older persons’ self-reported disability by living arrangements and gender, paying particular attention to various multigenerational arrangements.

Results

Controlling for past disability status, a significant relationship between living arrangements and current disability remains, but is moderated by gender. Older persons in households where they may be more “productive” report higher levels of disability; there are fewer differences in women’s than men’s reported disability levels across living arrangement categories.

Discussion

This study underscores the need to examine living arrangements and disability through a gendered lens, with particular attention to heterogeneity among multigenerational living arrangements. Some living arrangements may take a greater toll on older persons than others. Important policy implications for South Africa and other LMICs emerge among vibrant debates about the role of social welfare programs in improving the health of older individuals.

Keywords: Aging, Health, Multigenerational households

There is significant evidence in gerontology and family sociology on the importance of household living arrangements for older adults’ lives (Chen & Short, 2008; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988; Samanta, Chen, & Vanneman, 2015). Descriptive studies on the patterns of older persons’ living arrangements are well established in sub-Saharan Africa (Bongaarts & Zimmer, 2002; Kautz, Bendavid, Bhattacharya, & Miller, 2010; Zimmer, 2009), and there is an emerging focus on aging and disability Nyirenda et al., 2015; Payne, Mkandawire, & Kohler, 2013; Phaswana-Mafuya, Peltzer, Ramlagan, Chirinda, & Kose, 2013). We define disability as the consequences of disease that impair body functions and structures, limit activity, and restrict participation, as based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (Von Korff et al., 2008). In South Africa, disability prevalence in the aging population is impacted both by the increasing prevalence of HIV among the population older than 50 years (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2013; Hontelez et al., 2011), and by an emerging noncommunicable disease (NCDs) epidemic. NCDs are increasingly contributing to morbidity and disability, as well as mortality among older South Africans (Kengne & Mayosi, 2014; World Health Organization, 2014).

In African settings, where the majority of older persons live in multigenerational households, there are critical questions about whether living arrangements might exacerbate or buffer disability among older persons, mainly depending on the availability of care to address older persons’ needs, and expectations that they provide care to others. It is unclear how gender, as operationalized through social roles, may act as a moderator between disability and living arrangements (Schatz & Seeley, 2015). With a projected fourfold increase in the number of older individuals in sub-Saharan Africa from 2006 to 2050 (UNAIDS Gap Report 2014), understanding these relationships is essential for targeting interventions that will reach the most vulnerable in lower and middle income countries (LMIC).

Traditions of aging in place coupled with inadequate alternatives to family-based care mean that multigenerational living arrangements continue to be the dominant residential arrangement for older persons in much of sub-Saharan Africa (Bongaarts & Zimmer, 2002; Zimmer, 2009). In rural South Africa in particular, older persons' living situations have been affected by the hollowing of the middle generation due to HIV as well as migration of young adults (Kautz et al., 2010; Zimmer, 2009), leading to many older persons living in multigenerational households with fostered and orphaned grandchildren (Hosegood & Timaes, 2005). Despite the multigenerational households being the norm for older Africans, most studies do not distinguish among different multigenerational arrangements (for an exception from Asia see, Samanta et al., 2015).

In this study, we disaggregate living arrangements as follows: (a) Single-generation (which encompasses alone and with spouse), (b) Two-generation (which encompasses: with/without spouse, and with adult children), (c) Linear-linked multigenerational (which includes only households with/without spouse, with married adult children and their children), (d) Complex-linked multigenerational (with/without spouse, and any adult children (not married), and any grandchildren), and (e) other (including any combination of related and unrelated persons not previously described). By discriminating amongst multigenerational arrangements, we draw attention to their heterogeneity. Specifically, we differentiate between Linear-linked arrangements in which we believe older persons are more likely to taken care of (which might be regarded as “dependent” on household resources and assistance), and Complex-linked, in which they are likely to receive less support and be asked to do more labor (which could be designated as their taking on a more “productive” role) (Schatz, Madhavan, Collinson, Gómez-Olivé, & Ralston, 2015).

Building on work by Samanta et al. (2015) from India, and our own previous work on older persons in South Africa (Schatz et al., 2015), we offer a nuanced classification of multigenerational households to examine gender differences in the relationship between living arrangements and disability; we also assess the possibility of endogeneity between disability and living arrangements over time. We aim to expand our understanding of the relationship between living arrangements and disability in a setting with weak public care-infrastructure and traditional gendered social roles.

Disability and Aging in Africa

Given limited data available from sub-Saharan Africa on disability, we review studies using a range of measures to highlight the burden of disability in the region. Together these studies offer a picture of a high burden of disability, links between poor health and disability, and increasing disability with age.

The incorporation of self-reported information on functional and daily activity limitation has improved the measurement of disability globally (Mitra, Posarac, & Vick, 2013). Despite Dewhurst and colleagues (2012) finding lower rates of disability within a community dwelling population of those older than 70 years in Tanzania (9%) than found in Europe (26%), higher levels of disability are found in other African populations. In rural Malawi, poor health was closely associated with functional limitations. Over a quarter of adults reported moderate or severely limited functioning between ages 45 to 65 years, and nearly half of those older than 65 years reported these limitations (Payne et al., 2013). In a nationally representative South African survey, over a third of persons older than 50 years reported moderate, severe, or extreme disability, and reports of disability increased steadily with age (Phaswana-Mafuya et al., 2013). As African populations age and survival rates increase, we expect to see disability prevalence increase at older ages across settings.

Disability prevalence is affected by a number of factors including gender, education, and socioeconomic status (SES), as well as factors related to living arrangements like martial status and availability of family caregivers. In the national and regional data from South Africa, a higher percentage of women than men reported disability across age groups (Nyirenda et al., 2015; Phaswana-Mafuya et al., 2013). Work from our study site similarly shows that women reported higher levels of disability and worse health status than their male peers (Gómez-Olivé, Thorogood, Clark, Kahn, & Tollman, 2010). Other key predictors of higher reported disability included having lower levels of education and SES (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2010). In some studies, marital status and living arrangements were key predictors of disability, e.g., living alone, or being divorced or widowed, predicted disability (Phaswana-Mafuya et al., 2013). Further, other studies have found that older persons’ children and grandchildren provided care in response to older persons’ needs (Nyirenda et al., 2015), suggesting that individuals who live alone or without potential caregivers are likely to be more vulnerable when and if disability intensifies.

Living Arrangements, Disability, and Gender in Africa: Theoretical Considerations

Older adults’ living arrangements and extended kin networks are shaped by a number of factors including support systems, social roles, norms, histories, and emotions (Hughes & Waite, 2002). Disability often moderates household members’ needs and ability to provide support to others in the household. Household members’ roles and expectations of them fluctuate related to the care and resources members provide or that they need, resulting in some members receiving more than they give, and others giving more than they receive. In many cases, the expectation is for a downward flow of resources to support children when they are young (Caldwell & Caldwell, 1993; Goody, 1982), but for an upward flow in old age. Disability and functionality among older persons along with availability of resources may influence the direction resources flow (Mitra et al., 2013).

The presence or absence of support or resources, and the need for the older person to provide care for others, may accommodate or exacerbate disability (Nyirenda et al., 2015; Samanta et al., 2015). The impact on older persons can be positive, but it is just as possible that excess claims on kinship obligations can be burdensome (Portes, 1998). As level of disability increases, older persons need more assistance with activities of daily living and are less able to contribute physical labor to the household (Kengne & Mayosi, 2014; Payne et al., 2013). In households where older persons carry out strenuous activities—farming, collecting water or firewood, care work for selves, and others—a disability may hinder their ability to complete these tasks. This type of arduous work may also increase disability by taking a physical toll (Samanta et al., 2015). Data from our research site provide evidence that older women in particular, but also older men, were a financial resource to their households (Case & Menendez, 2007). Specific mechanisms included pooling their pension funds, providing child care, caring for those who are sick, and other functions necessary to sustain households (Schatz & Ogunmefun, 2007). Older persons are making financial and caregiving contributions to households, their contributions may be more necessary in some living arrangements than others. Thus, older persons may be deemed “productive” in living arrangements where there are greater expectations and needs, and they are making greater contributions of emotional and physical labor for themselves and others (e.g., Single-generation and Complex-linked multigenerational). Older persons living in Two-generation and Linear-linked multigenerational arrangements may be viewed as “dependent,” as they are less likely to need to contribute financially, because of the presence of married (and potentially working) adult children (and sometimes their children) who can assist with activities of daily living and thus lessen older persons’ burdens (Schatz et al., 2015). Further, connections between disability and living arrangements are likely to be shaped by gendered expectations (Calasanti, 2004), making it essential to examine how gender moderates this relationship.

Important theoretical concerns related to power, vulnerability, and inequity underlie gender differences in both living arrangements and disability (Calasanti, 2004; Knodel & Ofstedal, 2003; Prus & Gee, 2003). Living arrangements often differ by gender; older women in sub-Saharan Africa are less likely than older men to live in a household with a spouse, and more likely to live with at least one adult child (Bongaarts & Zimmer, 2002). Further, gender undergirds social roles within families and households, roles that shift as individuals age (Calasanti, 2004; Knodel & Ofstedal, 2003). Differential gender access to social resources accumulate over a lifetime contributing to health disparities at older ages (Prus & Gee, 2003). Given gendered social roles, it is critical to consider whether women and men experience the same living arrangements in the same ways, and whether gender moderates the relationship between living arrangements and disability.

Disability may be exacerbated or diminished by household roles undertaken by older persons (Knodel & Ofstedal, 2003; Mudege & Ezeh, 2009). Household roles are often defined by gender; in many African contexts, older women shoulder more physical care work than men (Cliggett, 2005; Schatz & Seeley, 2015). In the context of HIV, older persons, particularly women, provide care work for fostered or orphaned grandchildren and those who are sick in their networks (Schatz & Seeley, 2015). Women’s additional caregiving responsibilities could become more challenging at advanced stages of disability or impinge on their health. On the other hand, the social connections built over time might result in women having a “gender advantage” over men in terms of their ability to call on assistance from others as disability increases (Mudege & Ezeh, 2009). Men are frequently expected to be breadwinners, even into older ages; men may also be asked to do physical care work, which can conflict with their notions of masculinity and appropriate behavior (Calasanti, 2004; Schatz & Seeley, 2015). Existing research on the connection between care work and disability is mixed. Nyirenda and colleagues (2015) found that older persons’ reporting caregiving activities also reported better ability to perform activities of daily living. A higher percentage of older women in Uganda reported simultaneously providing and receiving care; however, it is unclear if this was due to greater caregiving needs or the “gender advantage” of greater investment in kin networks (Mugisha, Schatz, Seeley, & Kowal, 2015).

The extant literature suggests mixed results in the relationship between living arrangements and disability among older adults in LMIC. We believe these mixed results may be in part due to a lack of differentiation among living arrangements. In order to advance this research, we focus on two main questions: (a) Are older persons’ living arrangements associated with disability status? (b) Does this relationship differ by gender (as a proxy for gendered social roles)? We hypothesize that older persons’ living in “productive” arrangements (as defined earlier) are likely to have higher levels of disability than those in “dependent” arrangements. We anticipate that the magnitude of the effects will differ by gender, with women reporting greater disability overall due to expectations of care provision to others. We project smaller gender differences in “dependent” than “productive” arrangements, as we assume that married adult children in the former would take care of parents equally.

Method

We test our hypotheses using census data from the Agincourt Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance Site (HDSS) and survey data from the World Health Organization Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). The HDSS has collected data annually from all households in the Agincourt subdistrict since 1992. As of 2010, the site covered 27 villages—approximately 15,600 households and 89,000 individuals. In 2006 and 2010, Agincourt conducted an abbreviated version of the SAGE as a census module to collect health and well-being data on persons older than 50 years living in the HDSS. In 2006, approximately 65% of the target population completed the module (N = 4,085; (For details of the sample, response rates, and data collection, see Gómez-Olivé et al., 2010). Approximately 60% of the target population—all persons older than 50 years in 2010—completed the second wave questionnaire with only 0.4% refusing. Others were either not found (35%), ineligible (4%), or dead (1.6%). The resulting 2010 SAGE sample contains 5,966 respondents. In addition to the 2010 sample, we analyze a subsample of respondents interviewed in both 2006 and 2010; the longitudinal SAGE subsample consisted of 2,645 individuals. Approximately 75% of all respondents in each data set (2010, 2006/2010) are female due to high male labor migration, even at older ages, and greater life expectancy for women than men (Kahn, Garenne, Collinson, & Tollman, 2007).

Variables

Using household relationship codes related to the household head, we generated the five living arrangement categories outlined in the introduction: Single-generation, Two-generation, Linear-linked multigenerational, Complex-linked multigenerational, and Other arrangements (Schatz et al., 2015). In the regression models, we report results with Linear-linked multigenerational arrangements as the reference category. We view Linear-linked as the “ideal” living arrangement for aging South Africans because in this arrangement adult children, who are married by definition of the category, are also more likely to be working, increasing the likelihood that there are individuals present to care for both children and aging individuals, as well as income beyond state-funded pensions (Schatz et al., 2015).

Our dependent variable from the 2010 SAGE survey is the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS-II) based on the ICF framework (Von Korff et al., 2008). WHODAS-II provides a valid measure of disability in LMICs (Von Korff et al., 2008). The WHODAS-II measure is constructed from self-reports on the ability to carry out “normal” daily tasks in six domains: cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities, and participation. Twelve questions assessing individuals’ difficulty performing activities in these domains during the past 30 days are converted to a 0–100 scale; a higher score indicates worse physical functioning (i.e., more severe disability). The 2006 WHODAS-II variable (used as a control) is dichotomized: those in the top two WHODAS-II score quintiles, the highest levels of disability, are classified as having “poor functionality” (Gómez-Olivé et al., 2010).

A number of individual and household characteristics are important controls for this analysis based on the literature we cite above, and other work on African aging, families, or health. Individual characteristics include age, sex, education level, and self-identified nationality. Education is categorized as no formal education or some education. In this population, the majority in this age group had little opportunity for education, making this the most meaningful distinction. All respondents are Black South Africans. A third of the Agincourt population is Mozambican by birth; the majority settled in the area in the 1980s. Work from the site shows health differences by South African/Mozambican self-identification (Hargreaves, Collinson, Kahn, Clark, & Tollman, 2004; Schatz, 2009). Thus, the only two self-identified nationalities are South African and Mozambican. In our models, “South African” captures self-identification as South African or Mozambican.

The primary household level control is socioeconomic status (SES). SES is determined by a household asset score derived from 34 variables collected in 2009. This score includes information about the type and size of dwelling, access to water and electricity, appliances and livestock owned, and transport available. The score is derived from principal component factor analysis and then divided into quintiles (Houle et al., 2013). Although household size is salient (see Table 1), we excluded it as a covariate due to the correlation between household size and number of generations.

Table 1.

Background Characteristics and Disability for Persons Aged More Than 50 in 2010, Agincourt HDSS and SAGEa

| Percent or mean (SD) (n = 5,809) | |

|---|---|

| WHODAS-II | 22 (18) |

| Female | 75 |

| Age | 66 (11) |

| No formal education | 63 |

| South African | 69 |

| Household size (SD) | 7 (4) |

| Socioeconomic status (quintiles) | |

| First (lowest) | 16 |

| Second | 20 |

| Third | 22 |

| Fourth | 19 |

| Fifth (highest) | 23 |

| N a | 5,809 |

Note: HDSS = Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance Site; SAGE = Study on global AGEing and adult health; WHODAS = World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

aThe sample for this table are all persons interviewed in 2010, accounting for missing data from education and socioeconomic status variables.

Analysis

We present descriptive statistics of our 2010 sample followed by the profile of individuals reporting disability by living arrangements and sex. Models (not shown) that include a sex and living arrangements interaction confirm a significant interaction between female and Complex-linked multigenerational arrangements. Due to sex differences in disability reporting and the interaction effect, we examine, separately for men and women, whether a relationship between living arrangements and disability exist in OLS regression models using 2010 cross-sectional data. We include individual and household control variables, and cluster by household. Finally, we assess and control for possible endogeneity between disability and living arrangements with an analysis of the longitudinal 2006/2010 subsample. Regressions, by sex, control for past disability, and key individual and household covariates. Previous research shows significant stability (over half) of older persons remaining in particular living arrangements over time, and of those who do not, a quarter is lost to follow-up (Madhavan, Schatz, & Collinson, 2016). Single-generation and Complex-linked arrangements are particularly stable suggesting that the potential extensive care burden for others in these households, and fewer people on whom to depend for care, could lead to cumulative effects of disability over time.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics and disability scores for person older than 50 years in the 2010 sample. Overall, the sample was mainly female (75%) with no formal education (63%) and South African (69%). The overall mean household size was about seven persons with a range of 1 to 33 household members. The sample’s average age was 66 years with a range of 50 to 106. The average WHODAS-II score is 22 with a standard deviation of 18; this is comparable to the average national score which was 20 in 2010 (Phaswana-Mafuya et al., 2011). In national SAGE studies from Ghana, Mexico, India, and Russia, the mean WHODAS-II scores are around 20; China’s average is closer to 10 (He, Muenchrath, & Kowal, 2012). In our sample, nationally, and internationally, women, on average, report greater disability than to men (He et al., 2012; Phaswana-Mafuya et al., 2013).

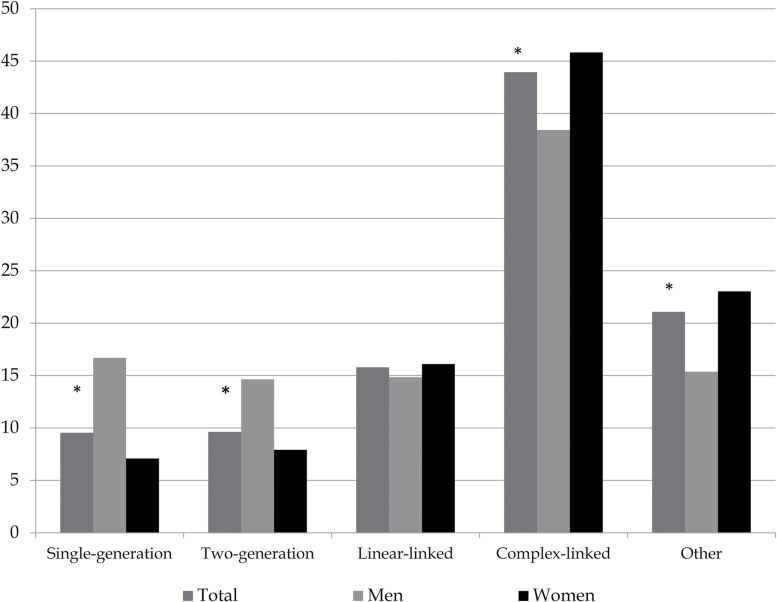

Figure 1 shows the distribution of living arrangements for the total sample and separately for men and women. Chi-square tests show statistically significant differences in the percent of men and women living in all arrangements except Linear-linked. Our data indicate more men than women live in Single-generation arrangements (16.7% vs 7.1%), a higher percentage of men than women reside in Two-generation arrangements (14.7% vs 7.9%), and about equivalent percentage of men and women live in Linear-linked multigenerational arrangements (14.9 vs 16.1). The highest percentage of men and women reside in Complex-linked arrangements, with a lower percentage of men (38.4%) than women (45.8%) living in this multigenerational arrangement. In addition, 15.4% of men and 23.0% of women resided in Other living arrangements. The mean household size is as follows: Single-generation 1.4, Two-generation 4.7, Linear-linked 10.4, and Complex-linked 8.4. A significant bivariate relationship exists between household size and disability for men and women, as household size increases the WHODAS-II score decreases, indicating less disability in larger households (not shown).

Figure 1.

Percent of older persons (more than 50 years) by living arrangement and sexab.*Note: HDSS = Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance Site; SAGE = Study on global AGEing and adult health.aAgincourt 2010 HDSS and SAGE respondents: Men N = 1,522; Women N = 4,444; Total N = 5,966. bStar indicates significant difference at .05 level between men and women in chi-square test.

Table 2 presents the percent of individuals reporting poor functionality by sex and living arrangements. Chi-square tests show that all differences between men and women within each of the living arrangement categories are statistically significant. Nearly half of women living in Single-generation (46.8%) arrangements reported poor functionality; however, due to limited numbers, this arrangement combines those who are living alone (i.e., widowed or divorced), with those who were living only with a spouse. About 6% of men and 2% of women lived with their spouse, for these individuals the mean level of disability was slightly higher for women than for men (20.96 vs 17.83; NS). Disability was higher for those living alone, and women (5%) fair much worse than men (11%) (30.22 vs 21.25; p < .001). In multigenerational arrangements, the percent reporting poor functionality (those in top two quintiles of WHODAS-II measure) is lower: 39.4% of women in Complex-linked and 35.1% of women in Linear-linked arrangements. About 35.8% of women living in Two-generation arrangements report poor functionality. Among men, there is more variation across categories of living arrangements, and lower percentages reporting poor functionality.

Table 2.

Percent Reporting Poor Functionality by Living Arrangement for Women and Men Separately Aged More Than 50 in 2010, Agincourt HDSS and SAGEabc

| Women (n = 4,444) | Men (n = 1,522) | χ 2 | Total (n = 5,966) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-generation | 46.8 | 36.1 | * | 42.0 |

| Two-generation | 35.8 | 26.5 | * | 32.2 |

| Linear-linked | 35.1 | 22.6 | *** | 32.1 |

| Complex-linked | 39.4 | 32.8 | ** | 37.9 |

| Other | 41.3 | 31.6 | ** | 39.5 |

Note: HDSS = Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance Site; SAGE = Study on global AGEing and adult health.

aStars designate significant differences between men and women in chi-squared test: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

bThe sample for this table includes all Agincourt 2010 HDSS and SAGE respondents.

cPoor functionality was determined if the respondents WHODAS-II score was in the top two quintiles.

Results for OLS regression of living arrangements (and individual and household controls) on 2010 WHODAS-II as a continuous variable, with separate regressions for women (Models 1 and 2) and men (Models 3 and 4), clustered by household are listed in Table 3. Models 1 and 3 include living arrangements and individual controls, Model 2 and 4 add in SES as a household level control. For women, as shown in Model 1, there are two living arrangements that are associated with reporting significantly higher disability, living in Single-generation or Other arrangements compared to Linear-linked multigenerational arrangements. Older age, having no education and being South African are associated with significantly higher reported disability among women. SES is not a significant factor in reported disability for older women when added in Model 2. SES slightly diminishes the Model 1 effects. However, the effect of women living in Single-generation and Other arrangements reporting higher levels of disability compared to those in Linear-linked arrangements remains significant at the .05 level.

Table 3.

Regression Models for Disability Status for Women and Men Separately Aged More Than 50 in 2010, Agincourt HDSS and SAGEab

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (n = 4,322) | Model 2 (n = 4,307) | Model 3 (n = 1,475) | Model 4 (n = 1,472) | |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Single-generation | 3.406** (−1.283) | 3.039* (−1.315) | 4.118** (−1.562) | 2.381 (−1.685) |

| Two-generation | 1.608 (−1.116) | 1.314 (−1.101) | 3.990* (−1.576) | 3.352* (−1.567) |

| Linear-linked multigenerational | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Complex-linked multigenerational | 1.032 (−0.718) | 0.985 (−0.724) | 3.928** (−1.254) | 3.644** (−1.261) |

| Other | 1.815* (−0.831) | 1.744* (−0.831) | 4.022* (−1.673) | 3.716* (−1.667) |

| Age | 0.533*** (−0.028) | 0.532*** (−0.028) | 0.326*** (−0.051) | 0.323*** (−0.051) |

| No formal education | 1.269* (−0.622) | 1.232* (−0.626) | 3.347*** (−0.998) | 2.906** (−1.002) |

| South African | 2.027** (−0.627) | 2.218*** (−0.660) | 2.240* (−1.099) | 3.449** (−1.168) |

| Socioeconomic status (quintiles) | ||||

| First (lowest) | REF | REF | ||

| Second | −0.588 (−0.898) | 1.505 (−1.699) | ||

| Third | −1.306 (−0.897) | −1.927 (−1.606) | ||

| Fourth | −1.066 (−0.931) | −2.03 (−1.75) | ||

| Fifth (highest) | −0.876 (−0.951) | −4.493** (−1.63) | ||

| Intercept | −15.744*** (−1.847) | −14.918*** (−1.962) | −9.778** (−3.613) | −7.895* (−3.761) |

| R2 | 0.115 | 0.116 | 0.056 | 0.068 |

Note: HDSS = Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance Site; SAGE = Study of global AGEing and adult health. The table displays unstandardized coefficients and robust standard errors in parentheses.

a*p < .05; **p < .01, ***p < .001, #p < .1.

bThe original sample of 5,966 was reduced due to missing data on several variables including education and socioeconomic status.

For men (Model 3), the living arrangements effects appear to be even stronger than those for women; compared to men in Linear-linked arrangements, men in all other living arrangements report higher disability. The differences in reported disability for men of being in a Single-generation (4.1 points higher) or in Complex-linked (3.9 points higher) compared to Linear-linked arrangement are highly significant (p < .01). Similar to the women in our sample, for the men, older age, having no education and being South African are associated with significantly higher reported disability. When adding in SES in Model 4, the effect of living in a Two-generation, Complex-linked multigenerational, and Other arrangements remains significant, while living in Single-generation compared to Linear-linked arrangements does not. Although SES mutes the effect, net controls, living in a Complex-linked multigenerational arrangement still increased men’s reporting of disability by 3.6 points. SES mutes the effects of having no formal education but increases the effect of being South African. Men in the highest SES group report significantly lower disability than those in the poorest SES quintile.

Finally, OLS regression results in Table 4 are for the longitudinal subsample with disability information from 2006 and 2010. This analysis tests for possible endogeneity between living arrangements and disability, including the same individual and household controls used in Table 3. The dependent variable (WHODAS-II), key household arrangement variables, and control variables are from the 2010 survey. Poor WHODAS-II in 2006 is included to assess whether disability in an earlier period is associated with individuals living in particular living arrangements in 2010.

Table 4.

Regression Models for 2010 Disability Status for Women and Men Separately Aged More Than 50 Longitudinal Subsample 2006/2010, Agincourt HDSS and SAGEa

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (n = 2,096) | Model 2 (n = 2,089) | Model 3 (n = 527) | Model 4 (n = 527) | |

| Living arrangements (2010) | ||||

| Single-generation | 4.042* (−1.837) | 4.043* (−1.882) | 2.785 (−2.71) | 1.406 (−2.854) |

| Two-generation | 1.984 (−1.828) | 1.565 (−1.744) | 7.142* (−3.142) | 6.936* (−3.103) |

| Linear-linked multigenerational | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Complex-linked multigenerational | 0.961 (−1.037) | 0.963 (−1.042) | 6.246** (−2.315) | 6.110** (−2.345) |

| Other | 2.103# (−1.187) | 2.037# (−1.187) | 5.478# (−2.986) | 5.263# (−3.025) |

| Poor WHODAS-II in 2006 | 5.860*** (−0.822) | 5.992*** (−0.825) | 8.632*** (−1.957) | 8.462*** (−1.953) |

| Age | 0.525*** (−0.045) | 0.529*** (−0.045) | 0.332*** (−0.087) | 0.314*** (−0.086) |

| No formal education | 0.768 (−0.914) | 0.896 (−0.921) | 1.313 (−1.709) | 0.667 (−1.723) |

| South African | 1.823* (−0.93) | 1.766# (−0.987) | 0.103 (−2.136) | 1.247 (−2.218) |

| Socioeconomic status (quintiles) | ||||

| First (lowest) | REF | REF | ||

| Second | −0.309 (−1.348) | 2.501 (−3.014) | ||

| Third | 0.18 (−1.354) | 1.891 (−2.899) | ||

| Fourth | −0.394 (−1.426) | 0.931 (−3.292) | ||

| Fifth (highest) | 0.319 (−1.405) | −4.784# (−2.808) | ||

| Intercept | −17.258*** (−2.97) | −17.625*** (−3.136) | −10.092 (−6.648) | −8.665 (−6.818) |

| R2 | 0.13 | 0.133 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

Note: HDSS = Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance Site; SAGE = Study on global AGEing and adult health; WHODAS = World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule. The table displays unstandardized coefficients and robust standard errors in parentheses.

a*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, #p < .1.

This subsample analysis shows that women living in Single-generation or Other arrangements versus Linear-linked multigenerational arrangements report higher levels of disability, even when controlling for past disability and key covariates. Men living in a Two-generation or Complex-linked multigenerational arrangements report higher levels of disability compared to men in Linear-linked multigenerational arrangements when controlling for earlier disability and key covariates. These effects hold in the models with the individual controls (Models 1 and 3), and with SES added (Models 2 and 4). Table 4 shows that while past disability was a significant predictor of current disability, an important and significant relationship between living arrangements and disability remains.

Discussion

South Africa and many LMICs are facing marked demographic shifts with growing numbers of older persons and a concomitant increase in aging-related health issues, including increasing disability prevalence. In such contexts, older persons co-reside with kin in living arrangements marked by a complex set of demands on time and resources. Thus, it is crucial to understand the relationship between living arrangements and disability, and how gender moderates this relationship. Following Samanta and colleagues (2015), we disaggregate living arrangements in a way that allows us to investigate the heterogeneity of multigenerational households. Our analysis highlights two important findings: (a) different living arrangements, including variation in multigenerational arrangements, may accommodate or exacerbate disability and (b) the effect is different for older men and women. Reflecting the heterogeneity of (multigenerational) living arrangements, we find that older persons residing in Two-generation and Linear-linked arrangements are less likely to report disability than their peers residing in Single-generation and Complex-linked arrangements. These differences are consistent with our earlier work, in which we argued that older persons in Two-generation and Linear-linked arrangements were more likely to be “dependent” on other members of their households, whereas those in Single-generation and Complex-linked arrangements were more likely to be “productive” household members (Schatz et al., 2015). Therefore, if an older person is in a dependent role and being “taken care of” financially and practically by others, s/he is less likely to report a disability. Conversely, an older person may be more likely to experience and report disability if s/he is taking on a productive role, with expectations of (a) financial contributions—which would divert resources away from his/her own health care—and (b) care work for children—which could include strenuous activities. In short, being part of a large, multigenerational arrangement does not guarantee care for older persons. This level of nuance is important as it tempers the idealized portrayal of the individuals resting and being taken care of by others in their old age.

Although effects are evident for both sexes, they are much stronger for men. The critical role of gender is not entirely surprising since women have greater expectations to provide physical care and men to provide financial care (Calasanti, 2004; Mudege & Ezeh, 2009; Schatz & Seeley, 2015). Gendered social roles are linked with care responsibilities and access to care, and these expectations and resources differ by living arrangements (Cliggett, 2005; Schatz & Seeley, 2015). Drawing on our categorization of living arrangements, older men in “productive” arrangements (Single-generation and Complex-linked) were more likely to report higher levels of disability than those in “dependent” arrangements. In arrangements where older men had fewer household members on whom to rely for assistance or financial help, they may be forced to assume responsibilities for which they feel ill-equipped to undertake (Mudege & Ezeh, 2009). This may be evidence of a women’s “gender advantage” in that their investment in care work and kin at earlier periods mean that there are fewer expectations on them to take on tasks that would exacerbate disabilities. Alternatively, it is possible that men who could still work, particularly through age 65, were likely to do so; these absent men may have been living in Two-generation and Linear-linked arrangements. Those men found at home Single-generation and Complex-linked arrangements and, therefore available to be interviewed, may have disabilities that kept them from working, consequently increasing reported disabilities in these arrangements. Given that women at older ages are less likely to work outside of the home, similar selection effects across living arrangements may not be as noticeable.

We might expect that older people who need intensive care to be found in households with working adults (Two-generation) and grandchildren to take care of them (e.g., Linear-linked). Conversely, those who are most capable may be selected into Complex-linked arrangements precisely because of their “productive” capacity or may be left in Single-generation arrangements because they did not need care. However, our results suggest the opposite—those in “dependent” roles are less likely to report disability than those in “productive” roles. This finding suggests that gendered role expectations may be taking a physical toll, particularly on older men. On the other hand, women’s experience across arrangements may be more uniform, simply reflecting less role conflict and more consistency with their long-term experience of providing care to others. Still, this stronger effect for men is intriguing; a selection factor may put men at a higher risk of living arrangements being associated with disability. In earlier work, we found that older persons’ living arrangements are generally stable over time, particularly for older persons originating in “productive” arrangements (Schatz et al., 2015). In the longitudinal analysis, we find few differences in outcomes when controlling for disability in 2006, yet we cannot fully dismiss the possibility that disability determines living arrangements rather than living arrangements impacting disability.

Limitations

Measuring complex concepts like disability and potential selection bias are what make examining the relationship between disability and living arrangements challenging. We use a well-regarded measure of disability, the WHODAS-II, but as a self-reported measure, that evenly weights a number of domains its breadth is both its strength and potential failure. It may be that other measures of disability, including objective measures (e.g., strength, timed walking test) capture particular aspects of disability that relate differently to living arrangements. We also must be cautious about not ascribing causation when we can only identify association. Although it is tempting to say that a particular living arrangement influences disability, even when controlling for disability at an earlier point in time, we must be restrained in our conclusions.

Selection and sampling issues reveal further limitations. We must identify and account for possible selection factors increasing the likelihood of persons with/without disabilities to live in particular arrangements or to be found home at all. In all likelihood, the relationship is bidirectional, with contribution from factors related to other household members’ resources and needs, which are likely to change over time. Small samples in particular categories affected our analyses. Having a much smaller sample of men than women limited the power of our analysis for men; we partially addressed this limitation by running separate regression models by sex. Further, we were not able to disaggregate Single-generation arrangements in the regression models between those living alone (widowed, divorced) and those living with a spouse, which hid important gender variation including particularly high reports of disability among women living alone.

Implications

The relationship between living arrangements and disability is an important emerging area of research in LMICs as the proportion of older persons increases (Nyirenda et al., 2015; Samanta et al., 2015). It is important to understand (a) the roles that older persons play as a resource to their households, providing physical labor and care work, (b) how these roles might increase disability by taking a physical toll, and (c) how social welfare programs may impact the roles that older people play in their households and thus connect to disability and living arrangements. Older South Africans have access to a generous noncontributory pension program that is not readily available in other LMICs (Niño-Zarazúa, Barrientos, Hickey, & Hulme, 2012). But disability itself may be a barrier to accessing the grant. Ralston and colleagues (2015) found, in a sample of adults older than 60 years, that nonpension receiving adults have worse physical functioning than their pension-receiving counterparts, citing disability as a possible barrier to government resources. Pension-receipt may increase the expectation of older persons to perform “productive” roles. Thus, household members may expect more from older persons, alternatively pension-receipt may increase the desirability of older persons as household members without a concordant supply of needed care, either of which may negatively impact disability. Interviewing older women and men in depth about their social roles within the household may provide a more detailed picture of what they perceive to be expected of them, how pensions affect these expectations, and how their roles affect disability.

Although there are good reasons for older persons to live with kin in multigenerational arrangements, heterogeneity across multigenerational arrangements exists, with some forms taking a greater toll on older persons than others. This is not necessarily surprising, as others have documented the multiple demands on older persons’ time and resources in South Africa. Understanding older persons roles in different living arrangements—not simply their structure, but also their meaning for older members—may be a key factor in understanding the relationship between living arrangements, disability, and gender. Overall, our work motivates the need for more research to understand older persons’ roles across living arrangements and their relationship with disability, particularly in the context of ongoing debates about the role of social welfare programs in improving the well-being of older persons in LMICs.

Funding

The Agincourt Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance System has been supported with funding for the MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit from the Wellcome Trust, UK (grants 058893/Z/99/A, 069683/Z/02/Z and 085477/Z/08/Z, and 085477/B/08/Z); the South African Medical Research Council, University of the Witwatersrand. The Division of Behavioral and Social Research at the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, USA, supported this research through an Interagency Agreement and a project Grant R01 AG034479, support for the WHO-SAGE study, and grant R24 AG032112 to the University of Colorado Boulder for The Partnership for Social Science AIDS Research in South Africa’s Era of ART Rollout. Additionally, the NICHD-funded University of Colorado Population Center (grant R21 HD51146) provided administrative and computing support. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH, NIA, NICHD, or WHO.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge the respondents, staff, and management of the Agincourt Health and socio-Demographic Surveillance System for their respective contributions to the production of the data used in this study. We would like to thank Jen-Hao Chen for comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

- Bongaarts J. & Zimmer Z (2002). Living arrangements of older adults in the developing world: An analysis of demographic and health survey household surveys. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57, S145–S157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.3.S145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calasanti T. (2004). Feminist gerontology and old men. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59, S305–S314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/59.6.S305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell J., & Caldwell P (1993). The nature and limits of the sub-Saharan African AIDS Epidemic: Evidence from geographic and other patterns. Population and Development Review, 19, 817–848. doi:10.2307/2938417 [Google Scholar]

- Case A. & Menendez A (2007). Does money empower the elderly? Evidence from the Agincourt demographic surveillance site, South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. Supplement, 69, 157–164. doi:10.1080/14034950701355445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. & Short S. E (2008). Household context and subjective well-being among the oldest old in China. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 1379–1403. doi:10.1177/0192513X07313602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliggett L. (2005). Grains from grass: Aging, gender, and famine in rural Africa. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dewhurst F. Dewhurst M. J. Gray W. K. Orega G. Howlett W. Chaote P. Dotchin C. Longdon A. R. Paddick S-M. & Walker R. W (2012). The Prevalence of Disability in Older People in Hai, Tanzania. Age and Ageing, 41(4), 517–23. doi:10.1093/ageing/afs054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Olivé F. X. Angotti N. Houle B. Klipstein-Grobusch K., Kabudula C., Menken J., … Clark S. J (2013). Prevalence of HIV among those 15 and older in rural South Africa. AIDS Care, 25, 1122–1128. doi:10.1080/09540121.2012.750710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Olivé F. X., Thorogood M., Clark B., Kahn K., & Tollman S (2010). Assessing health and well-being among older people in rural South Africa. Global Health Action, 3(Suppl. 2), 23–35. doi:10.3402/gha.v3i0.2126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goody E. N. (1982). Parenthood and social reproduction: Fostering and occupational roles in West Africa. New York, NY/Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves J. R. Collinson M. A. Kahn K. Clark S. J. & Tollman S. M (2004). Childhood mortality among former Mozambican refugees and their hosts in rural South Africa. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 1271–1278. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Muenchrath M. N., & Kowal P. R (2012). Shades of gray: A cross-country study of health and well-being of the older populations in SAGE countries, 2007–2010. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Hontelez J. A. Lurie M. N. Newell M. L. Bakker R., Tanser F., Bärnighausen T., … de Vlas S. J (2011). Ageing with HIV in South Africa. AIDS (London, England), 25, 1665–1667. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834982ea [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V., & Timaes I (2005). The impact of adult mortality on the living arrangements of older people in rural South Africa. Ageing and Society, 25, 431–444. doi:10.1017/S0144686X0500365X [Google Scholar]

- Houle B. Stein A. Kahn K. Madhavan S., Collinson M., Tollman S. M., & Clark S. J (2013). Household context and child mortality in rural South Africa: The effects of birth spacing, shared mortality, household composition and socio-economic status. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42, 1444–1454. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. S. Landis K. R. & Umberson D (1988). Social relationships and health. Science (New York, N.Y.), 241, 540–545. doi:10.1126/science.3399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. E. & Waite L. J (2002). Health in household context: living arrangements and health in late middle age. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 1–21. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1440422/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn K. Garenne M. L. Collinson M. A. & Tollman S. M (2007). Mortality trends in a new South Africa: hard to make a fresh start. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health Supplement, 69, 26–34. doi:10.1080/14034950701355668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz T., Bendavid E., Bhattacharya J., & Miller G (2010). AIDS and declining support for dependent elderly people in Africa: Retrospective analysis using demographic and health surveys. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 340, c2841. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kengne A. P. & Mayosi B. M (2014). Readiness of the primary care system for non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet. Global Health, 2, e247–e248. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70212-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J., & Ofstedal M. B (2003). Gender and aging in the developing world: Where are the men?Population and Development Review, 29, 677–698. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2003.00677.x [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan S., Schatz E., & Collinson M (2017). Social positioning of older persons in rural South Africa: Change or stability?Journal of Southern African Studies, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S., Posarac A., & Vick B (2013). Disability and poverty in developing countries: A multidimensional study. World Development, 41, 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.024 [Google Scholar]

- Mudege N. N. & Ezeh A. C (2009). Gender, aging, poverty and health: Survival strategies of older men and women in Nairobi slums. Journal of Aging Studies, 23, 245–257. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2007.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugisha J., Schatz E., Seeley J., & Kowal P (2015). Gender perspectives in care provision and care receipt among older people infected and affected by HIV in Uganda. African Journal of AIDS Research, 14, 159–167. doi:10.2989/16085906.2015.1040805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niño-Zarazúa M., Barrientos A., Hickey S., & Hulme D (2012). Social protection in sub-Saharan Africa: Getting the politics right. World Development, 40, 163–176. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.04.004 [Google Scholar]

- Nyirenda M. Evandrou M. Mutevedzi P. Hosegood V. Falkingham J. & Newell M. L (2015). Who cares? Implications of care-giving and -receiving by HIV-infected or -affected older people on functional disability and emotional wellbeing. Ageing and Society, 35, 169–202. doi:10.1017/S0144686X13000615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne C. F. Mkandawire J. & Kohler H. P (2013). Disability transitions and health expectancies among adults 45 years and older in Malawi: A cohort-based model. PLoS Medicine, 10, e1001435. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phaswana-Mafuya N. Peltzer K. Schneider M. Makiwane M. Zuma K. Ramlagan S. Tabane C. Davids A. Mbelle N. Matseke G. & Phaweni K (2011). Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE), South Africa 2007–2008. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Phaswana-Mafuya N., Peltzer K., Ramlagan S., Chirinda W., & Kose Z (2013). Social and health determinants of gender differences in disability amongst older adults in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid (Online), 18, 1–9. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v18i1.728 [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1–24. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1 [Google Scholar]

- Prus S. G. & Gee E (2003). Gender differences in the influence of economic, lifestyle, and psychosocial factors on later-life health. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 94, 306–309. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.17269/cjph.94.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston M. Schatz E. Menken J. Gómez-Olivé F. X. & Tollman S (2015). Who benefits–Or does not–From South Africa’s old age pension? Evidence from characteristics of rural pensioners and non-pensioners. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13, 85. doi:10.3390/ijerph13010085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta T. Chen F. & Vanneman R (2015). Living arrangements and health of older adults in India. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 937–947. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. J. (2009). Reframing vulnerability: Mozambican refugees’ access to state-funded pensions in rural South Africa. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 24, 241–258. doi:10.1007/s10823-008-9089-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. Madhavan S. Collinson M. Gómez-Olivé F. X. & Ralston M (2015). Dependent or productive? A new approach to understanding the social positioning of older South Africans through living arrangements. Research on Aging, 37, 581–605. doi:10.1177/0164027514545976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E., & Ogunmefun C (2007). Caring and contributing: the role of older women in multi-generational households in the HIV/AIDS era. World Development, 35, 1390–1403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.04.004 [Google Scholar]

- Schatz E. & Seeley J (2015). Gender, ageing and carework in East and Southern Africa: A review. Global Public Health, 10, 1185–1200. doi:10.1080/17441692.2015.1035664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M. Crane P. K. Alonso J. Vilagut G., Angermeyer M. C., Bruffaerts R., … Ormel J (2008). Modified WHODAS-II provides valid measure of global disability but filter items increased skewness. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61, 1132–1143. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2014). Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer Z. (2009). Household composition among elders in sub-Saharan Africa in the context of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 1086–1099. doi:10.1111/j.1741- 3737.2009.00654.x [Google Scholar]