A detailed investigation into the intestinal lifestyle of Escherichia coli multilocus sequence type 131 revealed that these globally dominant multidrug-resistant pathogens use type 1 fimbriae to effectively colonize the mammalian gut and persist long term.

Keywords: E. coli ST131, intestinal colonization, type 1 fimbriae, fimH, multidrug resistance

Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies point to the gut as a key reservoir of multidrug resistant Escherichia coli multilocus sequence type 131 (ST131), a globally dominant pathogenic clone causing urinary tract and bloodstream infections. Here we report a detailed investigation of its intestinal lifestyle.

Methods

Clinical ST131 isolates and type 1 fimbriae null mutants were assessed for colonization of human intestinal epithelia and in mouse intestinal colonization models. Mouse gut tissue underwent histologic analysis for pathology and ST131 localization. Key findings were corroborated in mucus-producing human cell lines and intestinal biopsy specimens.

Results

ST131 strains adhered to and invaded human intestinal epithelial cells more than probiotic and commensal strains. The reference ST131 strain EC958 established persistent intestinal colonization in mice, and expression of type 1 fimbriae mediated higher colonization levels. Bacterial loads were highest in the distal parts of the mouse intestine and did not cause any obvious pathology. Further analysis revealed that EC958 could bind to both mucus and underlying human intestinal epithelia.

Conclusions

ST131 strains can efficiently colonize the mammalian gut and persist long term. Type 1 fimbriae enhance ST131 intestinal colonization, suggesting that mannosides, currently developed as therapeutics for bladder infections and Crohn’s disease, could also be used to limit intestinal ST131 reservoirs.

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC)–derived urinary tract and bloodstream infections are one of the most common bacterial infections in the world and constitute a significant burden on healthcare systems and the global economy [1]. Studies have shown that individuals with urinary tract infections carry the causative UPEC strain in their fecal microbiota [2]. With the recent global rise in antimicrobial resistance, the prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) E. coli, especially in the intestinal microbiota of healthy individuals, is also increasing [3, 4]. Many MDR E. coli belong to specific clonal groups, and E. coli belonging to multilocus sequence type 131 (ST131) represents a recently emerged pandemic clone [5, 6]. While most commonly reported as a cause of extraintestinal infections, an increasing incidence of ST131 isolates among fecal bacteria of healthy adults and children is now widely documented [4, 7, 8]. Also worrying is the recent emergence of ST131 intestinal pathogens [9].

There is considerable diversity within the ST131 lineage with 3 major sublineages denoted as clades A, B, and C [10]. Clade C strains are clinically predominant worldwide and associated with extensive resistance and virulence profiles [5, 10, 11]. Type 1 fimbriae are one of few extraintestinal virulence factors conserved across all ST131 strains [12, 13]. In fact, >90% of all E. coli, commensal or pathogenic, harbor type 1 fimbrial genes [14]. Type 1 fimbriae are hair-like projections present on the bacterial cell surface that aid in adhesion to various mucosal surfaces via interaction with mannosylated receptors [15]. Expression of type 1 fimbriae is phase variable, and many ST131 strains (including EC958, the representative clade C UPEC strain studied here) possess a unique mode of regulatory control of this organelle owing to insertional inactivation of the fimB regulator gene [16]. In ST131, type 1 fimbriae promote attachment to the bladder epithelium and intracellular colonization in a mouse urinary tract infection model [12, 17], as well as biofilm formation [18]. The role of type 1 fimbriae in mediating E. coli intestinal colonization is, however, less clear, with most studies investigating commensals or strains associated with Crohn’s disease [19–22].

The intestinal reservoir of MDR UPEC clones such as ST131 has long been overlooked as a target for interventional strategies, while the factors contributing to intestinal colonization and persistence remain unknown. In this study, we showed that ST131 can successfully colonize the mammalian intestine and demonstrated a role for type 1 fimbriae in promoting ST131 intestinal colonization and persistence.

METHODS

Ethics

Mouse experiments were approved by the Monash University Animal Ethics Committee (approval no. MARP/2013/117). Human intestinal biopsy work was approved by the University of East Anglia Faculty of Medicine and Health Ethics Committee (reference 2010/11–030; samples were registered at the Norwich Biorepository under NRES reference no. 08/h0304/85 + 5).

E. coli Culture Conditions

E. coli strains (Supplementary Table 1) were cultured at 37°C in lysogeny broth under aerated or static conditions with gentamicin (20 µg/mL) or chloramphenicol (30 µg/mL), as required. EC958ΔfimH was constructed by our modified λ-Red recombinase gene replacement system as previously described for EC958Δfim [12, 23] (primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2). The native fimH30 allele was reintroduced into EC958ΔfimH to generate the chromosomally complemented strain EC958fimHC. Mutants were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction and sequencing.

Epithelial Cell Adhesion and Invasion Assays

Intestinal epithelial cells Caco-2 (ATCC HTB-37; in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium [DMEM]), T84 (ATCC CCL-248; in DMEM and Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture), and LS174T (ATCC CL-188; in DMEM) were maintained in medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Invitrogen). Bacterial strains were enriched for maximal type 1 fimbriae production by 3 rounds of static subculture [12]. Adhesion and invasion assays were performed at a multiplicity of infection of 10, and bacterial colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter were enumerated as previously described [12].

Type 1 Fimbriae

Type 1 fimbriae production was tested by yeast cell agglutination [12] and anti-FimA Western blot analysis as previously described [24]; α-FimA antibody was generated against FimA peptide AGSVDQTVQLGQVRT, which is 100% conserved in all the strains used in this study. Rabbit α-GroEL antibody (Invitrogen) was used as a loading control for calculating relative band intensities (FimA/GroEL) in Image Lab, version 5.1 (BioRad).

Mouse Intestinal Colonization Models

Female C57BL/6 mice aged 6–7 weeks were pretreated with streptomycin (5 g/L) in drinking water for 3 days. Pretreatment ended 1 day prior to inoculation with varying doses of statically cultured EC958 WT or EC958Δfim (5 mice per group) by oral gavage. Dose range (low, 103 CFU; middle, 105 CFU; high, 107 and 109 CFU) was based on previous mouse E. coli intestinal colonization studies [21, 25, 26]. Mice were monitored daily for weight loss, and fresh fecal pellets were collected daily for up to 11 days after inoculation for CFU enumeration. On day 11, mice in the high-dose group were euthanized to determine intestinal tissue bacterial loads. A separate high-dose cohort was euthanized at 4 days after inoculation, and intestinal tissues were preserved in 4% (w/v) phosphate-buffered formaldehyde for histologic analysis. To determine whether EC958 can overcome colonization resistance, groups of 5 mice (none of which received streptomycin) were inoculated with a high dose of EC958 WT or EC958Δfim and monitored for 21 days. Fecal pellets for CFU enumeration were collected daily for 11 days after inoculation and on alternate days thereafter.

Histologic and Immunohistochemical Analyses

Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue specimens for morphological analysis. For immunohistochemical analysis, sections were incubated with rabbit α-O25 E. coli antibody (Abcam) at 4°C, treated with 3% H2O2 to quench endogenous peroxidase activity, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated α-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Invitrogen). A 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate (Invitrogen) was used for color development. Mucopolysaccharides were stained with 1% Alcian blue (pH 2.5; Australian Biostain), followed by Nuclear Fast Red (Australian Biostain) counterstain. Sections were dehydrated and mounted with Histomount (Invitrogen) for microscopy.

Infection of Human Intestinal Biopsy Specimens

Biopsy samples from the terminal ileum and transverse colon were obtained with informed consent during routine colonoscopy of adult patients at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital. Samples were taken from macroscopically normal areas, transported in In vitro organ culture (IVOC) medium and processed within the next hour. IVOC was performed as described previously [27]. Briefly, biopsy specimens were inoculated with statically cultured 107 CFU EC958, incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 7–8 hours, and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline to remove the mucous layer and nonadherent bacteria before processing for immunofluorescence staining and microscopy.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Cells and biopsy samples were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde or in Carnoy’s fixative. Samples were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked with 0.5% bovine serum albumin. Coverslips and tissues were sequentially incubated with primary antibodies (anti-MUC2 [Santa Cruz] and anti–E. coli [Abcam]) for 1 hour, followed by incubation in AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) for 30 minutes. Cell nuclei and filamentous actin were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Roche) and fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated phalloidin (Sigma) for 30 minutes, respectively. Cells and biopsy samples were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Labs) and analyzed using an Axio Imager M2 motorized fluorescence microscope (Zeiss).

Statistical Analysis

Cell infection assay data were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test. Bacterial loads in mouse intestinal tissues were analyzed by repeated measures 2-way analysis of variance. Two-tailed P values are reported for both tests. Longitudinal trends of mouse fecal log10 CFU were analyzed using generalized additive mixed models (GAMM; for correlated data) and generalized additive models (GAM) [28]. Since the overall trend over time was not linear and could not be readily described by fitting a power transformation, “additive” models that automatically fitted the best curve(s) were necessary. Furthermore, the fact that we have correlated longitudinal data measured on the same mice had to be taken into account. Model selection was performed using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). All modelling was performed in R [29], using the mgcv package [28], and plots were created using the lattice package [30]. Models tested and their Akaike information criteria are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

RESULTS

ST131 and Non-ST131 UPEC Strains Can Adhere to and Invade Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells

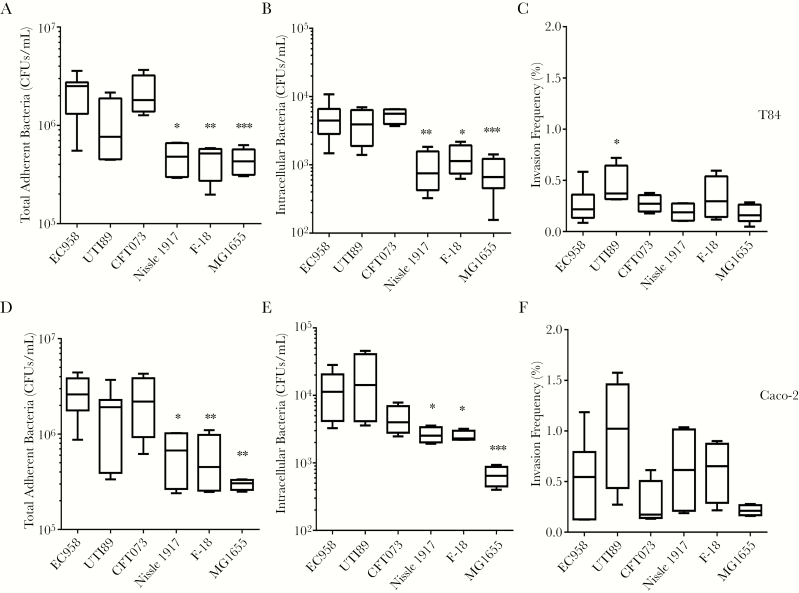

We compared the adhesion and invasion capacities of the reference clade C ST131 UPEC strain EC958 to that of reference non-ST131 UPEC strains UTI89 (ST95) and CFT073 (ST73), probiotic strain Nissle 1917, and commensal strains F-18 and MG1655, using the undifferentiated human intestinal cell lines T84 and Caco-2 (Figure 1). EC958 performed as well as the other UPEC strains in T84 and Caco-2 cell adhesion and invasion assays but had significantly higher adherent and intracellular CFUs as compared to the 3 nonpathogenic strains. Intestinal cell invasion mirrored adhesion patterns by all strains, with the exception of a slightly higher invasion frequency for UTI89 in T84 cells.

Figure 1.

Adhesion to and invasion of T84 and Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cells by uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) and commensal E. coli strains. T84 (A–C) and Caco-2 (D–F) monolayers were incubated with UPEC (strains EC958, UTI89, and CFT073), probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917, or commensal E. coli (strains F-18 and MG1655) for 1 hour (to determine the number of colony-forming units [CFU] of adherent bacteria) and then treated with gentamicin (to determine the number of CFUs of intracellular bacteria). Invasion frequencies are expressed as percentages of adherent bacteria invading the cells. Box plots summarize data from at least 4 experimental repeats. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001, by the Kruskal-Wallis test, compared with EC958.

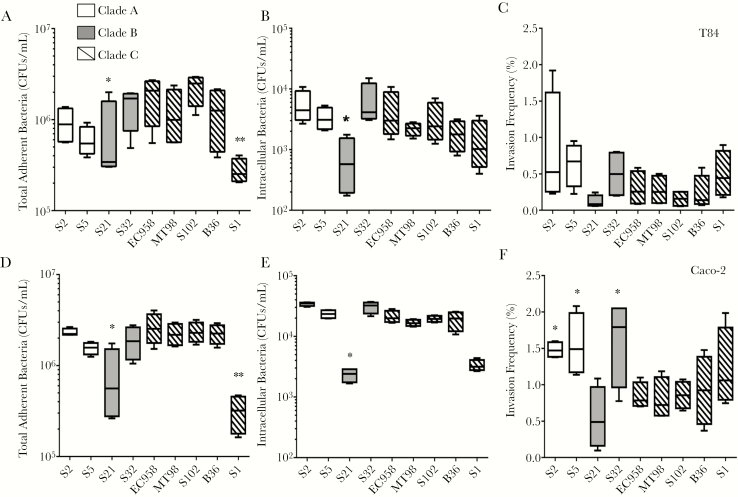

ST131 Strains From Different Clades Exhibit Similar Intestinal Cell Adhesion and Invasion Levels In Vitro

To determine whether intestinal cell adhesion and invasion levels by EC958 are representative of ST131 strains, we tested clinical isolates from clades A, B, and C as described above (Figure 2). There was no significant difference in the ability of most ST131 strains from the different clades to adhere to and invade into T84 and Caco-2 cells. Only S1 (clade C) and S21 (clade B) isolates had significantly lower adherent (and, for S21, intracellular) CFUs in both cell lines, but their invasion frequency was not different from that of other clade C isolates.

Figure 2.

Adhesion to and invasion of T84 and Caco-2 human intestinal epithelial cells by different ST131 strains. T84 (A–C) and Caco-2 (D–F) monolayers were incubated with ST131 strains from clades A, B, and C for 1 hour (to determine the number of colony-forming units [CFU] of adherent bacteria; A and D) and then treated with gentamicin \for 1 hour (to determine the number of CFUs of intracellular bacteria; B and E). Invasion frequencies are expressed as percentages of adherent bacteria invading the cells (C and F). Box plots summarize data from at least 4 experimental repeats. *P < .05 and **P < .01, by the Kruskal-Wallis test, compared with EC958.

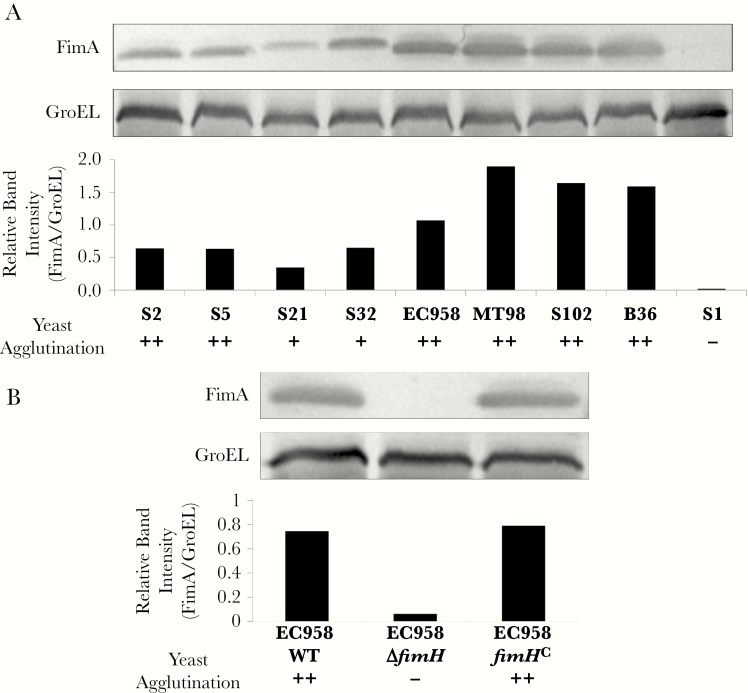

Type 1 Fimbriae Levels Vary Across ST131 Strains

To determine whether adherence and invasion into Caco-2 and T84 cells was correlated with production of type 1 fimbriae, all 9 ST131 strains were analyzed by anti-FimA Western blots and for functional production of type 1 fimbriae by the FimH-mediated yeast agglutination assay (Figure 3A). Production of type 1 fimbriae varied among ST131 strains, with highest levels observed for clade C strains and the lowest observed for S21 (clade B), whereas S1 made no detectable FimA and tested negative for yeast cell agglutination, suggesting a role for type 1 fimbriae in mediating intestinal cell adhesion and invasion.

Figure 3.

Type 1 fimbriae expression by ST131 strains. A, Western blot analysis of type 1 fimbriae expression in ST131 strains from clades A, B, and C. Whole-cell lysates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and probed with α-FimA antibody and standardized against GroEL expression in each strain. Relative band intensities (FimA/GroEL) were calculated using the Image Lab software. Strong (++), moderate (+), and negative (-) yeast agglutination reactions are indicated below the graph. B, Western blot analysis of type 1 fimbriae expression in the EC958 wild-type (WT) strain, the type 1 fimbriae null mutant (EC958ΔfimH), and its complemented derivate (EC958fimHC).

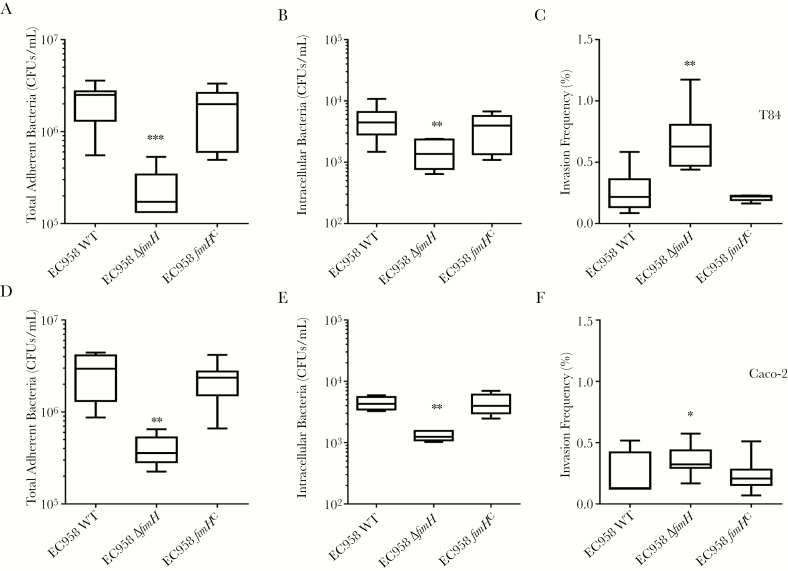

Type 1 Fimbriae Promote Intestinal Cell Adhesion and Invasion by EC958

To directly investigate the contribution of type 1 fimbriae in interactions between ST131 and intestinal cells, we constructed an EC958 type 1 fimbriae null mutant lacking the fimH adhesin gene (EC958ΔfimH) and a chromosomally complemented derivate carrying the WT fimH30 allele at its native locus (EC958fimHC). EC958ΔfimH and EC958fimHC were grown under type 1 fimbriae–enriching conditions (repeated static culture) similar to EC958 WT, confirming that EC958fimHC displayed WT type 1 fimbriae levels, while EC958ΔfimH had no detectable type 1 fimbriae expression (Figure 3B). EC958ΔfimH displayed significantly lower adhesion and invasion into T84 and Caco-2 cells as compared to EC958 WT, and this attenuation was restored in EC958fimHC (Figure 4). Interestingly, EC958ΔfimH displayed higher invasion rates in T84 and marginally in Caco-2 cells (P = .004 and P = .048, respectively). Thus, while an EC958ΔfimH mutant can still bind to and invade into human intestinal epithelial cells, production of type 1 fimbriae significantly enhances this phenotype. Furthermore, addition of mannose significantly reduced EC958 WT adhesion to EC958ΔfimH levels (Supplementary Figure 1), further confirming the role of type 1 fimbriae in promoting EC958–intestinal cell interactions.

Figure 4.

Role of type 1 fimbriae in EC958 adhesion and invasion of T84 and Caco-2 cells. T84 (A–C) and Caco-2 (D–F) monolayers were incubated with the EC958 wild-type (WT) strain, the type 1 fimbriae null mutant (EC958ΔfimH), or its complemented derivative (EC958fimHC) for 1 hour (to determine the number of colony-forming units [CFU] of adherent bacteria; A and D) and then treated with gentamicin for 1 hour (to determine the number of CFUs of intracellular bacteria; B and E). Invasion frequencies (C and F) are expressed as percentages of adherent bacteria invading the cells. Box plots summarize data from at least 4 experimental repeats. *P < .05 and **P < .01, by the Kruskal-Wallis test, compared with EC958 WT.

EC958 WT and the Type 1 Fimbriae Null Mutant Display Similar Patterns of Intestinal Passage in a Streptomycin-Pretreated Mouse Model

Since regulation of type 1 fimbriae expression in clade C ST131 strains is significantly different from that for other non-ST131 UPEC strains [12, 16], we used the representative EC958 strain and its corresponding type 1 fimbriae null mutant (EC958Δfim) [12] for in vivo colonization studies.

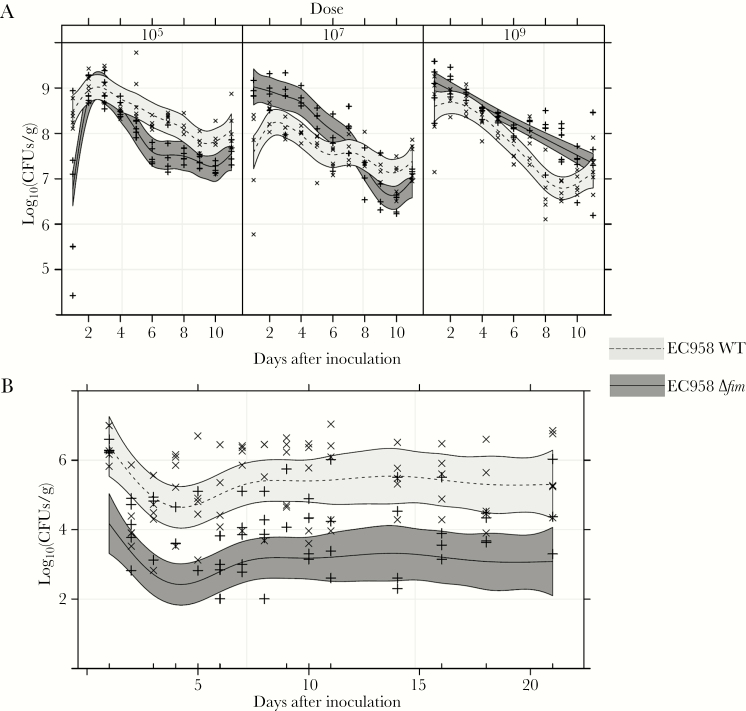

CFUs were measured daily for up to 11 days in fecal specimens from groups of 5 C57BL/6 mice treated with streptomycin prior to inoculation with varying doses of EC958 WT or EC958Δfim (Figure 5A). Longitudinal colonization (measured as log10 CFU per gram of feces) for each mouse cohort was analyzed using GAM, as no significant correlation was found between CFU measurements from the same mouse. Best-fit GAM models took account of the strain-dose combined effect and an additive component over time, which was found to be different for each strain-dose combination; thus, a different curve was fitted for each strain-dose (Figure 5A). Mice administered the low inoculation dose (103 CFU) were not colonized (data not shown). With middle (105 CFU) and high (107 and 109 CFU) doses, the number of EC958 WT and EC958Δfim CFUs in fecal specimens followed an overall curve resembling that originally described for the intestinal passage of invader E. coli strains by Freter et al [31]. Differences in fecal CFU counts between the 2 strains were statistically significant over the tested time course, but their magnitude was relatively small and the overall curve pattern for each strain was qualitatively variable depending on dose, with the WT present in higher numbers than the Δfim mutant at lower doses and with this being reversed in higher doses. Despite differences in EC958 WT and Δfim fecal loads at individual time points, by 11 days after inoculation group median CFUs remained high for both strains (>106 CFU/g feces) and ranged between 107 and 108 CFU/g feces.

Figure 5.

Colonization curves of the EC958 wild-type (WT) strain and the type 1 fimbriae null mutant in the mouse intestine. A, Longitudinal analysis of colony-forming unit (CFU) counts in fecal specimens recovered daily for 11 days after inoculation from C57BL/6 streptomycin-pretreated mice inoculated with EC958 WT or EC958Δfim at different doses. B, Longitudinal analysis of fecal CFU counts in mice without streptomycin pretreatment that were inoculated with 108 CFUs (high dose) of EC958 WT or EC958Δfim. Individual data points are shown for EC958 WT (x) and EC958Δfim (+). Curves in each panel represent generalized additive models for EC958 WT or EC958Δfim (as indicated), with 95% confidence intervals (shaded regions).

EC958 Can Colonize the Mouse Intestine in the Presence of Resident Microbiota, and Type 1 Fimbriae Contribute to Higher Colonization Levels

To determine whether EC958 can overcome the colonization resistance offered by the native intestinal microbiota, mice (none of which received streptomycin pretreatment) were inoculated with a high dose of EC958 WT or EC958Δfim and monitored for 21 days. The best-fit model in this case was a GAMM taking into account the correlated nature of the data (ie, a random intercept for each mouse, which creates such correlation), as well as the strain and an additive effect for time (Figure 5B). This indicated that the differences in fecal CFU counts observed for the 2 strains were statistically significant, and while both strains showed qualitatively the same pattern of colonization there was no curve overlap, with the Δfim null mutant clearly displaying colonization levels approximately 2 logs lower than those expressed by the WT. Although the strains displayed 100–1000-fold lower fecal CFU counts than those observed in the streptomycin-pretreated model, stable colonization was observed for both the WT and Δfim mutant for up to 21 days.

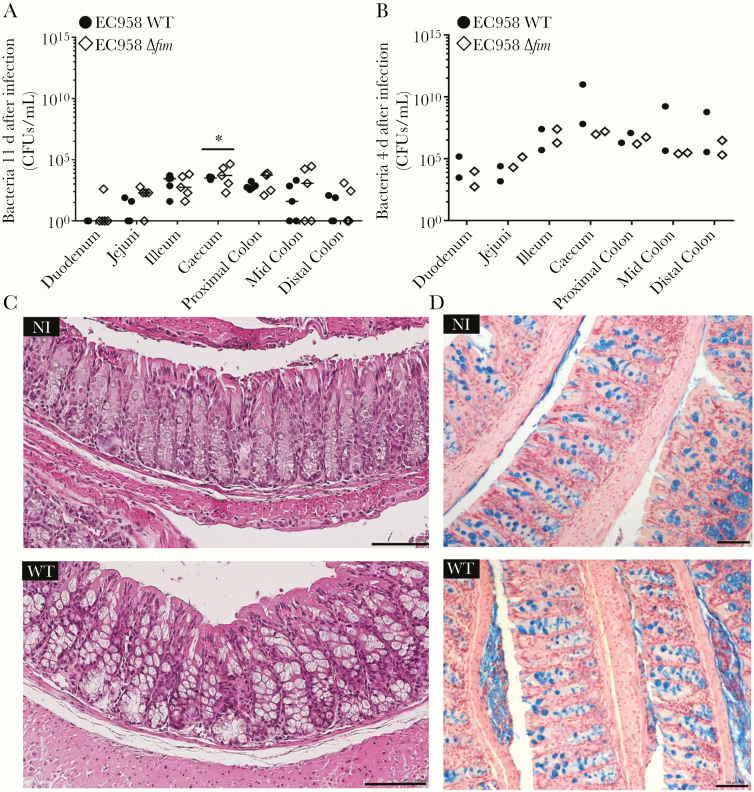

EC958 Burden Is Highest in the Distal Parts of the Mouse Intestine and Does Not Cause Any Obvious Pathology

Intestinal distribution of EC958 WT and EC958Δfim and associated tissue histopathology were investigated in high-dose mouse cohorts. Both strains displayed similar colonization patterns, with the highest bacterial loads detected in the cecum and colon, followed by the ileum (Figure 6A). No significant differences in tissue tropism between the WT and Δfim strains were observed except in the cecum, which had slightly higher numbers of EC958Δfim than WT (P < .05). No WT bacteria could be recovered from the duodenum.

Figure 6.

Bacterial loads in intestinal tissues and associated histologic findings. A and B, Streptomycin-pretreated mice were challenged with a high dose of either EC958 wild type (WT) or EC958Δfim and euthanized 11 days after inoculation (A) and 4 days after inoculation (B). Intestines were divided into different sections before homogenization for CFU enumeration at each site. Data points represent colony-forming unit (CFU) counts for individual mice from each strain set (as indicated) at different intestinal sites. Absence of data points from a group indicates that no bacteria were isolated from that mouse. Median values for each group are shown as horizontal bars. *P < .05, by repeated measures 2-way analysis of variance. C, Hematoxylin-eosin staining of non-infected (NI) and EC958 WT–infected mouse colonic tissue 4 days after inoculation. D, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining (targeting Escherichia coli O25 antigen) of NI and EC958 WT–infected mouse colonic tissue 4 days after inoculation. Mucopolysaccharides were stained with Alcian blue with Nuclear Fast Red counterstain. Scale bar, 100 µm.

To determine whether high bacterial loads of EC958 WT and EC958Δfim are detrimental to the host tissue, separate high-dose mouse cohorts were euthanized 4 days after inoculation, when tissue bacterial numbers were expected to be high and tissues from each cohort were used for CFU enumeration (n = 2) and histologic analysis (n = 3). Tissue bacterial loads ranged from 102 to 1011 CFU/g, with highest numbers present in the colon and cecum (Figure 6B). Tissue sections displayed no significant markers of histopathology by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 6C and Supplementary Figure 2). 3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining of tissue sections probed with an anti-O25 antibody (specific to ST131) did not detect any bacterial interaction with the intestinal epithelial surface in either EC958 WT (Figure 6D) or EC958Δfim tissues (data not shown), suggesting that bacteria most likely localized in the mucous layer of the mouse intestine.

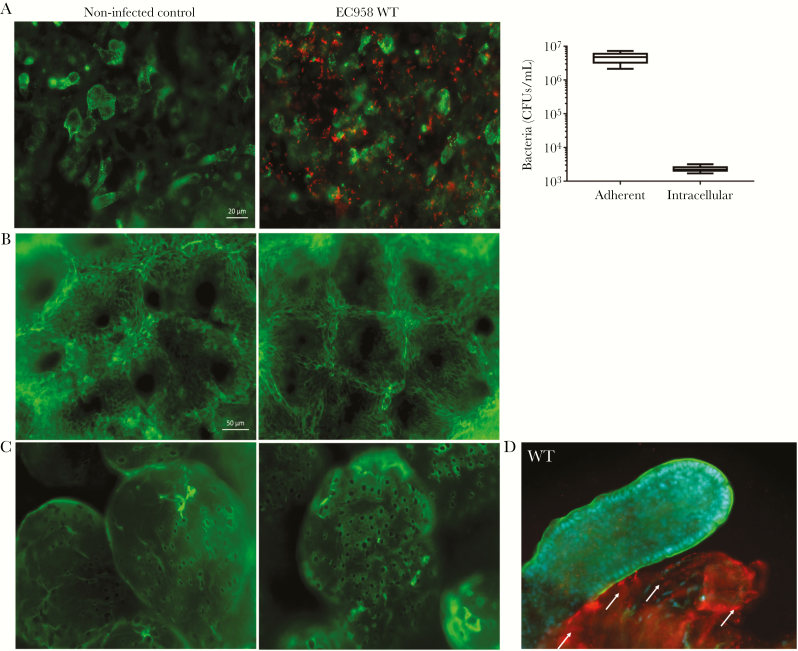

EC958 Adhesion to Human Mucus-Producing Intestinal Cells and Intestinal Biopsy Specimens

To determine the mucus-binding capacity of EC958, we studied its adhesion to and invasion of LS174T, a human colorectal mucin-producing cell line [32]. EC958-infected cell monolayers were processed for adherent and intracellular CFU quantification and were also stained for MUC2, the major secreted mucin in LS174T cells [32] (Figure 7A). A heterogeneous MUC2 expression profile was observed in confluent monolayers, with EC958 demonstrating high-level LS174T cell adherence irrespective of MUC2 production. Expression of type 1 fimbriae promoted adherence to LS174T cells, similar to the Caco-2 and T84 non–mucus-producing cell lines (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 7.

EC958 adhesion and invasion of mucus-producing LS174T human colorectal epithelial cells and human intestinal biopsy specimens. A, LS174T monolayers were incubated with EC958 wild-type (WT) for 1 hour (to determine the number of colony-forming units [CFU] of adherent bacteria) and then treated with gentamicin for 1 hour (to determine the number of CFUs of intracellular bacteria). Micrographs depict immunofluorescence staining of monolayers (n = 5 in duplicate); MUC2 is stained green, and red is stained EC958 WT. Scale bar, 20 µm. B and C, Immunofluorescence staining of human colonic (B) and ileal (C) biopsy specimens infected with EC958 WT for 7 hours with corresponding non-infected controls (n = 2 in duplicate). Tissue specimens were stained for actin (green) and EC958 (red). Scale bar, 50 µm. D, Human ileal biopsy specimens infected with EC958 for 8 hours (n = 2 in duplicate). Adherent EC958 (red) are present on exposed submucosal tissue (villus on right, indicated with white arrows) but not on intact epithelium (villus on left), which is indicated by an actin-rich (green) brush border. Cell nuclei are counterstained in blue.

Furthermore, adherence of EC958 to human intestinal mucosa was evaluated using IVOC of human intestinal biopsy specimens [27]. Tissue explants from the small intestine (terminal ileum) and transverse colon inoculated with EC958 for 7 hours showed good morphological tissue preservation but no bacterial adherence to the epithelium (Figure 7B and 7C). In explants infected with EC958 for 8 hours, extensive shedding of the epithelium was observed for both ileal (Figure 7D) and colonic (data not shown) samples. Adherent EC958 bacteria were detected on damaged areas where the basement membrane had been exposed but not on intact tissue.

DISCUSSION

The success of the pandemic E. coli ST131 clone as an extraintestinal pathogen has been widely documented. Recent studies suggest that host intestinal reservoirs are a major source of dissemination of this MDR uropathogen within the community [7, 33]. Here, we have examined the adhesion and invasion capacity of ST131 strains, including reference clade C strain EC958, showing that it is comparable to other reference UPEC strains and superior to commensal and probiotic E. coli strains known to be proficient gut colonizers [34].

Our analyses showed that the enhanced ability of EC958 to bind and invade intestinal epithelial cells was shared among isolates from all ST131 clades and that this was influenced by type 1 fimbriae. Interestingly, the lower level of adhesion observed for EC958ΔfimH was similar to that reported for 2 other ST131 strains in a previous study investigating Caco-2 binding in the absence of type 1 fimbriae [35]. Collectively, these data provide evidence that type 1 fimbriae are required for enhanced ST131 adhesion to the intestinal epithelium in vitro. Interestingly, type 1 fimbriae were also recently shown to mediate UPEC translocation through the intestinal epithelium [36].

Previous studies in the streptomycin-treated mouse model have shown that commensal E. coli upregulate type 1 fimbriae when bound to cecal mucus [19]. However, type 1 fimbriae were not essential for the establishment of long-term colonization [20, 21]. In our streptomycin pretreatment mouse model, both EC958 WT and EC958Δfim exhibited similar colonization levels by the end of the study period, despite statistically significant differences observed over time. Our findings are supported by results of an earlier study reporting similar intestinal colonization between the commensal F-18 strain and its type 1 fimbriae mutant [20]. It was also reported that discontinuation of streptomycin treatment after inoculation led to a drastic drop in bacterial numbers for both strains [20]. Additionally, another study reported that the TN03 ST131 strain could effectively outcompete commensal E. coli in the gut [26], using a streptomycin pretreatment model similar to that used in our study that did not continue antibiotic administration over the time course of colonization, leading to regeneration of the native microbiota. Moreover, we found that antibiotic pretreatment was not a prerequisite for establishing persistent intestinal colonization by EC958, thus suggesting that ST131 strains are able to overcome colonization resistance offered by the resident gut microbiota. Overall, longitudinal trends exhibited by EC958 in both of our mouse models indicate that colonization is fairly dynamic from day to day but persistent and that the strain is able to cope well with potential changes in the resident gut microbiota. Interestingly, we found that EC958Δfim achieved an approximately 100-fold lower colonization burden in the presence of complete gut microbiota, with some mice even clearing the mutant from the gut. These findings have clinical implications as they support the use of mannosides [17] for clearing antibiotic-resistant E. coli from the gut in circumstances such as before surgery or invasive diagnostic analyses or after return from a region of endemicity. Indeed, it was recently reported that a high-affinity mannoside can selectively deplete intestinal UPEC while simultaneously treating urinary tract infection in mice [37].

Despite colonizing the distal parts of the mouse intestine in high numbers over an extended period, EC958 did not cause gut pathology that is often associated with enteric E. coli pathogens [38]. This niche-specific colonization has been previously reported for Nissle 1917 and other pathogenic E. coli [25]. This is of importance as luminal localization may be an ideal niche for ST131 interactions with intestinal pathogens, potentially accounting for the recent emergence of E. coli ST131 strains exhibiting enteroinvasive phenotypes and antibiotic resistance [9, 39].

Since recent epidemiological reports suggest extensive ST131 carriage by healthy humans, we further investigated tissue tolerance to a high EC958 burden in the more physiologically relevant human intestinal IVOC model [27] and found that EC958 could not access the epithelium through the mucous layer. However, cytotoxicity was observed after extended incubation, which led to epithelial shedding and EC958 adherence to exposed parts of the submucosal tissue. These observations are of particular relevance for individuals with preexisting conditions that adversely affect epithelial barrier function, such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease [40, 41].

In summary, our study demonstrates that E. coli ST131 strains are proficient intestinal colonizers. We are the first to show that this clinically relevant lineage can effectively overcome host colonization resistance to establish persistence within the gut. We report that type 1 fimbriae enhance long-term colonization, a finding that supports the use of FimH inhibitors in lowering the ST131 intestinal burden in the community. However, colonization was not obliterated in the absence of type 1 fimbriae, suggesting the presence of additional factors that promote ST131 fitness in this niche. While ST131 colonization did not cause any obvious histopathology in our mouse model, the ability of these strains to bind to and invade exposed human epithelia, coupled with recent reports of ST131 intestinal pathogens [9, 39], warrant further investigation into ST131’s intestinal lifestyle, particularly in individuals with preexisting gut pathologies.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Dr Anu Chacko for providing technical assistance with in vitro infection assays and Dr Bernard Brett for providing human intestinal biopsy samples.

S. Sarkar, M. L. H., R. R., S. Schüller, and M. T. acquired data. S. Sarkar, M. L. H., D. L., S. Schüller, M. A. S., and M. T. created the study concept and design. S. Sarkar, D. V., R. R., S. Schüller, and M. T. analyzed and interpreted the data. S. Sarkar, M. L. H., D. V., S. Schüller, D. L., M. A. S., and M. T. wrote the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1069370; Senior Research Fellowship APP1106930 to M. A. S.), Queensland University of Technology (Vice Chancellor’s Senior Research Fellowship to M. T.), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (to S. Schüller), and the European Commission (Erasmus+ traineeship to R. R.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Foxman B. Epidemiology of urinary tract infections: incidence, morbidity, and economic costs. Dis Mon 2003; 49:53–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nielsen KL, Dynesen P, Larsen P, Frimodt-Møller N. Faecal Escherichia coli from patients with E. coli urinary tract infection and healthy controls who have never had a urinary tract infection. J Med Microbiol 2014; 63:582–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lo WU, Ho PL, Chow KH, Lai EL, Yeung F, Chiu SS. Fecal carriage of CTXM type extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing organisms by children and their household contacts. J Infect 2010; 60:286–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Gruson C, Bialek-Davenet S et al. 10-Fold increase (2006-11) in the rate of healthy subjects with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli faecal carriage in a Parisian check-up centre. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68:562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banerjee R, Johnson JR. A new clone sweeps clean: the enigmatic emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:4997–5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson JR, Urban C, Weissman SJ et al. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 (O25:H4) and blaCTX-M-15 among extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing E. coli from the United States, 2000 to 2009. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:2364–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Madigan T, Johnson JR, Clabots C et al. Extensive household outbreak of urinary tract infection and intestinal colonization due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli sequence type 131. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:e5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blanc V, Leflon-Guibout V, Blanco J et al. Prevalence of day-care centre children (France) with faecal CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli comprising O25b:H4 and O16:H5 ST131 strains. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69:1231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Imuta N, Ooka T, Seto K et al. Phylogenetic analysis of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) isolates from Japan reveals emergence of CTX-M-14-producing EAEC O25:H4 clones related to sequence type 131. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:2128–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Stanton-Cook M et al. Global dissemination of a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:5694–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ben Zakour NL, Alsheikh-Hussain AS, Ashcroft MM et al. Sequential acquisition of virulence and fluoroquinolone resistance has shaped the evolution of Escherichia coli ST131. MBio 2016; 7:e00347–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Totsika M, Beatson SA, Sarkar S et al. Insights into a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli pathogen of the globally disseminated ST131 lineage: genome analysis and virulence mechanisms. PLoS One 2011; 6:e26578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schembri MA, Zakour NL, Phan MD, Forde BM, Stanton-Cook M, Beatson SA. Molecular characterization of the multidrug resistant Escherichia coli ST131 clone. Pathogens 2015; 4:422–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ofek I, Doyle RJ.. Bacterial adhesion to cells and tissues. New York: Chapman and Hall, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krogfelt KA, Bergmans H, Klemm P. Direct evidence that the FimH protein is the mannose-specific adhesin of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Infect Immun 1990; 58:1995–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sarkar S, Roberts LW, Phan MD et al. Comprehensive analysis of type 1 fimbriae regulation in fimB-null strains from the multidrug resistant Escherichia coli ST131 clone. Mol Microbiol 2016; 101:1069–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Totsika M, Kostakioti M, Hannan TJ et al. A FimH inhibitor prevents acute bladder infection and treats chronic cystitis caused by multidrug-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli ST131. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:921–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sarkar S, Vagenas D, Schembri MA, Totsika M. Biofilm formation by multidrug resistant Escherichia coli ST131 is dependent on type 1 fimbriae and assay conditions. Pathog Dis 2016; 74:doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftw013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krogfelt KA, McCormick BA, Burghoff RL, Laux DC, Cohen PS. Expression of Escherichia coli F-18 type 1 fimbriae in the streptomycin-treated mouse large intestine. Infect Immun 1991; 59:1567–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCormick BA, Franklin DP, Laux DC, Cohen PS. Type 1 pili are not necessary for colonization of the streptomycin-treated mouse large intestine by type 1-piliated Escherichia coli F-18 and E. coli K-12. Infect Immun 1989; 57:3022–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCormick BA, Klemm P, Krogfelt KA et al. Escherichia coli F-18 phase locked ‘on’ for expression of type 1 fimbriae is a poor colonizer of the streptomycin-treated mouse large intestine. Microb Pathog 1993; 14:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dreux N, Denizot J, Martinez-Medina M et al. Point mutations in FimH adhesin of Crohn’s disease- associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli enhance intestinal inflammatory response. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9:e1003141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97:6640–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kakkanat A, Totsika M, Schaale K et al. The role of H4 flagella in Escherichia coli ST131 virulence. Sci Rep 2015; 5:16149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meador JP, Caldwell ME, Cohen PS, Conway T. Escherichia coli pathotypes occupy distinct niches in the mouse intestine. Infect Immun 2014; 82:1931–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vimont S, Boyd A, Bleibtreu A et al. The CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli clone O25b: H4-ST131 has high intestine colonization and urinary tract infection abilities. PLoS One 2012; 7:e46547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lewis SB, Cook V, Tighe R, Schüller S. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli colonization of human colonic epithelium in vitro and ex vivo. Infect Immun 2015; 83:942–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wood SN. Generalized additive models: an introduction with R. 1st ed Texts in statistical science series. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29. R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org. Accessed 3 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sarkar D. Lattice Multivariate data visualization with R. 1 ed New York: Springer-Verlag, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Freter R, Brickner H, Temme SJ. An understanding of colonization resistance of the mammalian large intestine requires mathematical analysis. Microecol Ther 1986; 16:147–55. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Göttke MU, Keller K, Belley A et al. Functional heterogeneity of colonic adenocarcinoma mucins for inhibition of Entamoeba histolytica adherence to target cells. J Eukaryot Microbiol 1998; 45:17S–23S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Bertrand X, Madec JY. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27:543–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Altenhoefer A, Oswald S, Sonnenborn U et al. The probiotic Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 interferes with invasion of human intestinal epithelial cells by different enteroinvasive bacterial pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2004; 40:223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peirano G, Mulvey GL, Armstrong GD, Pitout JD. Virulence potential and adherence properties of Escherichia coli that produce CTX-M and NDM β-lactamases. J Med Microbiol 2013; 62:525–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Poole NM, Green SI, Rajan A et al. Role for FimH in extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli invasion and translocation through the intestinal epithelium. Infect Immun 2017; 85:doi: 10.1128/IAI.00581-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Spaulding CN, Klein RD, Ruer S et al. Selective depletion of uropathogenic E. coli from the gut by a FimH antagonist. Nature 2017; 546:528–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Golan L, Gonen E, Yagel S, Rosenshine I, Shpigel NY. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli induce attaching and effacing lesions and hemorrhagic colitis in human and bovine intestinal xenograft models. Dis Model Mech 2011; 4:86–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O’Brien CL, Bringer MA, Holt KE et al. Comparative genomics of Crohn’s disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli. Gut 2017; 66:1382–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boltin D, Perets TT, Vilkin A, Niv Y. Mucin function in inflammatory bowel disease: an update. J Clin Gastroenterol 2013; 47:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Laukoetter MG, Nava P, Nusrat A. Role of the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14:401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.