Key Points

SNP rs311103 is associated with human erythroid-specific Xga/CD99 blood group phenotypes.

The erythroid GATA1 factor binds to the polymorphic rs311103 genomic region differentially, which affects transcriptional activity.

Abstract

The Xga and CD99 antigens of the human Xg blood group system show a unique and sex-specific phenotypic relationship. The phenotypic relationship is believed to result from transcriptional coregulation of the XG and CD99 genes, which span the pseudoautosomal boundary of the X and Y chromosomes. However, the molecular genetic background responsible for these blood groups has remained undetermined. During the present investigation, we initially conducted a pilot study aimed at individuals with different Xga/CD99 phenotypes; this used targeted next-generation sequencing of the genomic areas relevant to XG and CD99. This was followed by a large-scale association study that demonstrated a definite association between a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs311103 and the Xga/CD99 blood groups. The G and C genotypes of SNP rs311103 were associated with the Xg(a+)/CD99H and Xg(a−)/CD99L phenotypes, respectively. The rs311103 genomic region with the G genotype was found to have stronger transcription-enhancing activity by reporter assay, and this occurred specifically with erythroid-lineage cells. Such activity was absent when the same region with the C genotype was investigated. In silico analysis of the polymorphic rs311103 genomic regions revealed that a binding motif for members of the GATA transcription factor family was present in the rs311103[G] region. Follow-up investigations showed that the erythroid GATA1 factor is able to bind specifically to the rs311103[G] region and markedly stimulates the transcriptional activity of the rs311103[G] segment. The present findings identify the genetic basis of the erythroid-specific Xga/CD99 blood group phenotypes and reveal the molecular background of their formation.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

The Xg blood group system, the 12th of the 36 human blood group systems to be acknowledged, contains 2 antigens: Xga and CD99. Xga, first identified early in 1962,1 is an X chromosome–linked blood group antigen. In 1981, Goodfellow and Tippett identified the Xga-related CD99 blood group antigen, and the Xga and CD99 antigens were found to show a unique and sex-specific phenotypic relationship on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs).2 The Xg(a+) and Xg(a−) blood groups are common polymorphic phenotypes among individuals; furthermore, CD99 expression shows erythroid-specific quantitative traits that have been classified into the CD99-high (CD99H) and CD99-low (CD99L) phenotypes. This CD99H and CD99L phenotypic variation is directly related to the Xga blood group.2,3 Among females and males, the Xg(a+) phenotype is associated with the CD99H phenotype. On the other hand, Xg(a−) females show an association with the CD99L phenotype; however, Xg(a−) males, in addition to having the CD99L phenotype as 1 possibility, may also have the CD99H phenotype (Figure 1A).

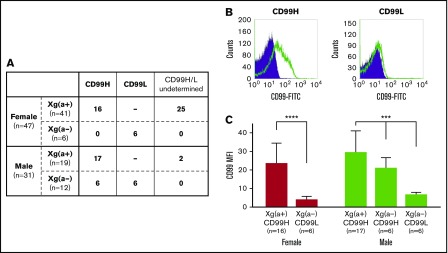

Figure 1.

The Xga and CD99 blood group phenotypes. (A) The Xga and CD99 blood group phenotypes of the 78 Taiwanese enrolled in this study. A total of 41 of the 47 females and 19 of the 31 males were found to have the Xg(a+) phenotype, and the remaining 6 females and 12 males were found to have the Xg(a−) phenotype. (B) Determination of the CD99H and CD99L blood group phenotypes using flow cytometry. The left and right panels were obtained from the flow cytometry analyses of RBCs derived from 1 Xg(a+) female and 1 Xg(a−) female, respectively. The open and shaded areas represent the results obtained from RBCs incubated with monoclonal antibody 12E7 and FITC-conjugated second antibody and with FITC-conjugated second antibody only, respectively. (C) Quantitative comparison of CD99 expression levels across the individual groups of the various Xga/CD99 blood groups in females and males. The geometric mean of the fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD99 for each sample was obtained from the flow cytometry analysis by subtracting the MFI of the RBCs incubated with the second antibody only from the MFI of the RBCs incubated with the 12E7 mAb, followed by the second antibody. The means of CD99 MFI in each of the individual groups according to their Xga/CD99 phenotypes in females and males are presented; the error bars indicate the standard error of the mean of each group. Statistical analyses among the different phenotypic groups of females and males were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test (****P < .0001) and the Kruskal-Wallis test (***P < .001), respectively. The results showed that the CD99 expression levels of the Xg(a+)/CD99H groups were significantly higher than those of the Xg(a−)/CD99L groups, and the CD99 expression level of the Xg(a−)/CD99H male group was found to be intermediate between the levels of the Xg(a+)/CD99H males and Xg(a−)/CD99L males.

A series of studies were conducted from the 1980s onwards with the aim of revealing the genetic and molecular basis for the intriguing phenotypic relationship between the Xga and CD99 blood groups. The Xga and CD99 antigens are glycoproteins4 and are found to be expressed separately on the membrane of RBCs.5 Notably, it has been found that the reticulocytes from Xg(a+)/CD99H individuals have a higher level of the XG and CD99 (MIC2) transcripts than the reticulocytes from Xg(a−)/CD99L individuals.3,6 Based on these findings, it has been proposed that the Xga/CD99 blood groups and their phenotypic relationship are brought about by the transcriptional coregulation of XG and CD99 expression (reviewed in Tippett and Ellis6 and Daniels7). XG and CD99 are homologous genes, and each consists of 10 exons.8,9 They are situated side by side at the tips of the X and Y chromosomes and span the pseudoautosomal boundary (Figure 2). CD99 is located in pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1),10 whereas XG spans the pseudoautosomal boundary with exons 1-3 being located within PAR1 and exons 4-10 being X specific.11 As a result, an incomplete XG is present on the Y chromosome. Neither gene is subject to X inactivation.12-14 After the genomic organization of XG and CD99 was recognized, a genetic element, the XG Regulator, was proposed to coregulate the expression of XG and CD99 and, thus, determine the Xga/CD99 blood groups.6,15

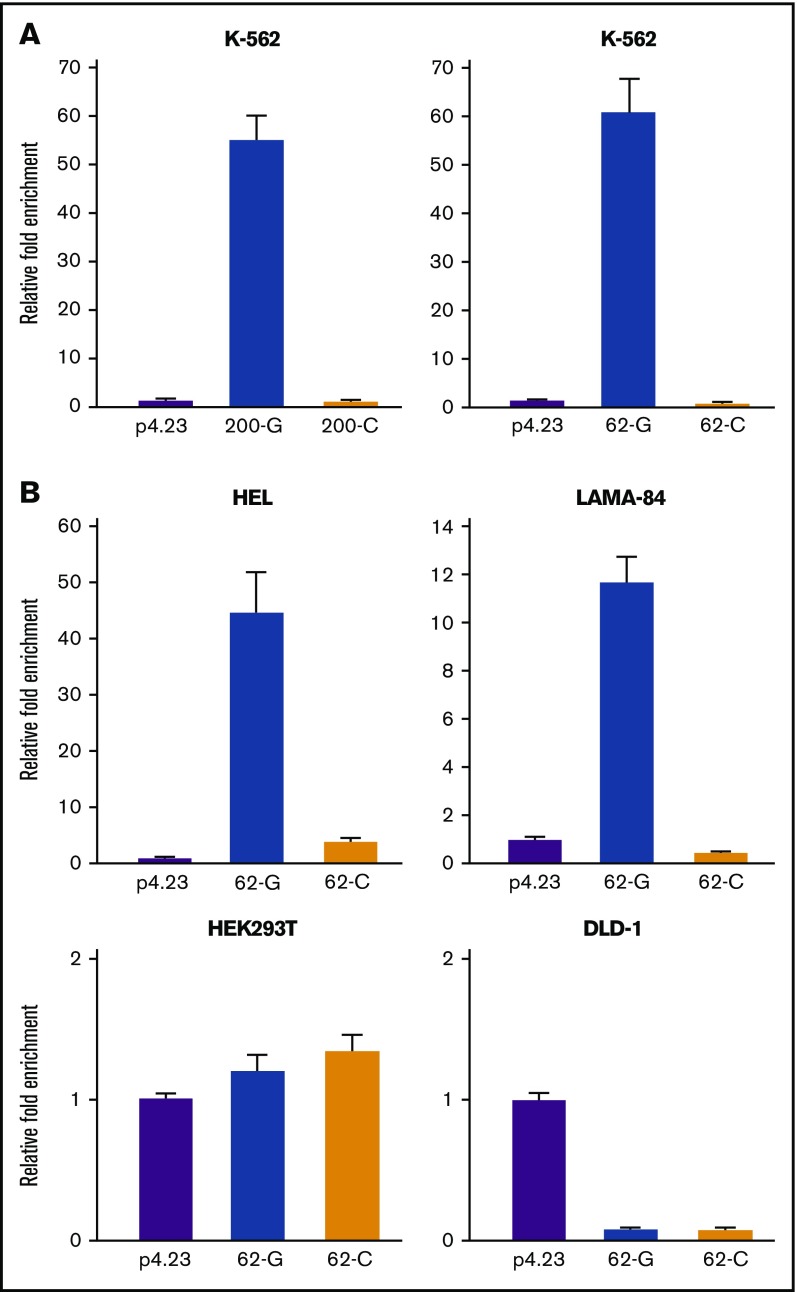

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the genomic organizations of XG and CD99 on the X and Y chromosomes and the location of SNP rs311103. The genomic organizations of the RefSeq transcripts of XG (accession NM_175569) and CD99 (NM_002414) in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database are represented schematically (based on assembly GRCh37). The blue rectangles represent the exon regions. The red dashed lines indicate the pseudoautosomal boundary (PBD). The genomic DNA sequences of the X chromosome 2240-2810-kb regions of 8 females and 8 males with different Xga/CD99 blood group phenotypes were determined in our pilot study.

In the present investigation, through a pilot investigation that involved large-scale DNA sequence analysis of the relevant XG and CD99 genomic areas using targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS), together with a follow-up association study, we have demonstrated that the Xga/CD99 blood groups are associated with a nucleotide polymorphism that affects the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs311103. During the review process for this manuscript, a study reported that SNP rs311103 is responsible for the Xg(a+)/Xg(a−) phenotypes.16

Methods

Sample preparation and Xga blood group typing

Peripheral blood samples were collected from 78 healthy nonrelated Taiwanese (47 females and 31 males). The Xga blood group of each sample was determined by the antiglobulin test using human monoclonal anti-Xga reagent HIRO-123 (a gift from Tokyo Metropolitan Blood Center, Japanese Red Cross Society). Genomic DNA was purified from the peripheral blood cells of each sample using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN). This human study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Flow cytometry analysis to allow CD99 blood group determination

After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline, the RBCs were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-CD99 antibody (clone 12E7)17 (Abcam) at a final concentration of 20 μg/mL for 1 hour at 4°C. The bound monoclonal antibodies were detected by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Leinco Technologies). Finally, the cells were subjected to flow cytometry to measure their fluorescence.

Targeted NGS

The X-chromosome 2240-2810K regions of genomic DNA samples were enriched using a SureSelectXT Custom kit (Agilent Technologies). The sequences were then determined using a NextSeq 500 system (Illumina).

Sanger resequencing

Five DNA segments encompassing a 4.7-kb region (X chromosome 2 663 675-2 668 362-bp region) were amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and the sequences were determined using the Sanger method. The PCR primer pairs used are listed in supplemental Table 1.

Reporter assay

The PCR primer pair XGFa and XGRb (supplemental Table 1) was used to amplify the 2 666 284-2 666 483-bp region of the X chromosome. The PCR-amplified DNA fragments were inserted into the BamHI and SalI sites of the pGL4.23 reporter vector (Promega). The created reporter constructs, denoted 200-G and 200-C, carry a 200-bp genomic DNA segment in which the rs311103 site bears the G or C nucleotide, respectively. The primer pair XGFc and XGRf was used to amplify the X-chromosome 2 666 352-2 666 413-bp region using PCR. The amplified fragments were inserted into the KpnI and SacI sites of the pGL4.23 vector, and the created reporter constructs, denoted 62-G and 62-C, carry a 62-bp genomic DNA segment in which the rs311103 site bears the G or C nucleotide, respectively.

Transfection of the reporter vectors and the β-galactosidase–expressing plasmid pCH110 (Amersham), which served as an internal control, into the host cells and the analysis of the reporter assays were performed as described previously.18

Ectopic expression of transcription factor

The expression vectors for the GATA1-GATA6 and LEF1 transcription factors were purchased from Origen Technologies. Cotransfection of the expression vector, reporter construct, and internal control vector into the host cells in the reporter assays was performed as described previously.19

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Oligonucleotides with sequences GGTTTGCAAAGATAAATGCCTT (sense for rs311103[G]), AAGGCATTTATCTTTGCAAACC (antisense for rs311103[G]), GGTTTGCAAACATAAATGCCTT (sense for rs311103[C]), and AAGGCATTTATGTTTGCAAACC (antisense for rs311103[C]) were synthesized. Annealing of the complementary oligonucleotides yielded 22-bp rs311103[G] and rs311103[C] DNA fragments. HEK293T cells were transfected with the expression vectors for GATA1 and GATA2 or the empty pCMV6-entry vector and cultured for 48 hr. Nuclear extracts of the transfected HEK293T cells and the native K-562 cells were prepared using a Nuclear Extract kit (Active Motif). The subsequent electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) experiments were performed as described previously.19

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was performed using the Pierce Magnetic ChIP assay kit (Thermo Scientific), following the manufacturer’s protocols. A total of 4 × 106 HEL cells was used in the ChIP analysis, and rabbit monoclonal anti-GATA1 antibody (clone EPR17362), rabbit polyclonal anti-GATA2 (Abcam) antibody, or normal rabbit IgG was used to immunoprecipitate the chromatin DNAs that had been cross-linked with the transcription factors. Real-time PCR was performed using a QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit and the primer pair SF and SR (supplemental Table 1).

Cell culture

Cells were cultured as described in supplemental Methods.

Results

The Xga and CD99 blood group phenotypes of the 78 enrolled Taiwanese subjects

Peripheral blood samples from 78 Taiwanese subjects (47 females and 31 males) were collected in the present investigation, and their Xga blood groups were determined (Figure 1A). Flow cytometry analysis was used to quantitatively compare the expression levels of the RBC CD99 antigen (Figure 1B) among the subjects. In total, 16 samples from the 41 Xg(a+) females, 17 samples from the 19 Xg(a+) males, together with the samples from the 6 Xg(a−) females and 12 Xg(a−) males were subjected to the flow cytometry analysis. All of the 33 Xg(a+) samples analyzed were found to have the CD99H phenotype, whereas the 6 Xg(a−) females were found to have the CD99L phenotype. Six of the 12 Xg(a−) males had the CD99L phenotype, whereas the remaining 6 Xg(a−) males were shown to have the CD99H phenotype (Figure 1A). The RBC CD99 antigen expression levels of each individual were compiled based on the different Xga/CD99 phenotypes present in females and males (Figure 1C).

Targeted NGS was able to identify candidate SNPs that showed an association with the Xga/CD99 blood groups

Next, we conducted a pilot investigation that involved targeted NGS of the 2240-2810K regions of the X chromosome (Figure 2), which encompasses the region from 370 kb upstream of CD99 to 75 kb downstream of XG. This was carried out on the genomic DNAs from 16 individuals; these subjects consisted of 4 females and 4 males with the Xg(a+)/CD99H phenotype and 4 females and 4 males with the Xg(a−)/CD99L phenotype. Comparison of the 570-kb genomic sequences of these 16 individuals revealed 3536 SNPs (data not shown); among these SNPs, rs311103 and rs311104 were found to be associated with the Xga/CD99 phenotypic polymorphisms of the 16 individuals.

The genomic areas encompassing rs311103, rs311104, and an additional 15 contiguous SNPs from the 16 individuals who had been enrolled in the pilot study were amplified by PCR, and the sequences were determined using the Sanger method. This verified the DNA sequences of the 4.7-kb genomic regions (2 663 675-2 668 362 bp) of the 16 individuals, with the exception of an ∼270-bp region (around 2 667 140-2 667 410 bp) that contains a highly repeated region of C and T nucleotides. The Sanger resequencing confirmed the genotypes of rs311103, rs311104, and the 15 contiguous SNPs of these 16 individuals (supplemental Table 2). Comparison of the 4.7-kb DNA sequences did not identify any other common nucleotide polymorphisms among the 16 individuals. This further analysis confirmed the association between SNPs rs311103 and rs311104 and the Xga/CD99 phenotypic polymorphisms among the 16 individuals enrolled in the pilot study.

A larger-scale association study demonstrated a definite association between SNP rs311103 and Xga/CD99 blood groups

Subsequent to the above analysis, we completed the genotyping of the 17 SNPs (rs311103, rs311104, and the 15 contiguous SNPs) of the remaining 62 samples using Sanger sequencing. The results obtained from this larger-scale association study (summarized in supplemental Table 3) demonstrated that there was a definite association between genotypic polymorphism at rs311103 and the phenotypic polymorphisms of the Xga/CD99 blood groups (Figure 3A), but there was no such association for rs311104 or the other 15 contiguous SNPs.

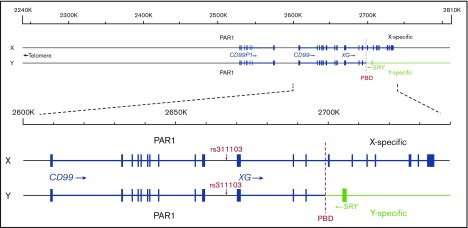

Figure 3.

Association between SNP rs311103 and Xga/CD99 blood groups. (A) Association of SNP rs311103 with the Xga/CD99 blood groups. The G and C polymorphic nucleotides of SNP rs311103 are identified by blue and yellow squares, respectively. In total, 16 of the 41 Xg(a+) female samples and 17 of the 19 Xg(a+) male samples were subjected to CD99 blood group typing, and the 33 Xg(a+) samples were found to have the CD99H phenotype. (B) Association P values of the 17 SNPs. The χ2 test was used to analyze the association P values of the 17 SNPs from the enrolled 78 individuals. The y-axis shows −log10 P values, and the x-axis shows the X-chromosome positions. The red horizontal line corresponds to a P value of 5.0 × 10‒7. SNP no. 8 is rs311103. (C) Quantitative comparison of RBC CD99 antigen expression levels across the individual groups with different genotypes at SNP rs311103. A total of 51 of the 78 individuals enrolled in the present study were subjected to quantitative analysis to determine their RBC CD99 antigen expression levels using flow cytometry. The means of the CD99 mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs; refer to the legend of Figure 1C) in each of the individual groups according to their genotypes at rs311103 are presented; the error bars indicate the standard error of the mean of each group. Statistical analyses among the different groups were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test (****P < .0001).

An overview of the association status of the 17 SNPs from the 78 individuals is shown in Figure 3B, and rs311103 shows a significant association with the Xga/CD99 blood group phenotypes (P = 4.88 × 10‒11). The genotypes of the 17 SNPs observed in the 78 individuals was examined for the observed vs expected heterozygosity using the Fisher exact test; the results, with P values for the 17 SNPs ranging from .31 to 1, verify that the observed genotypes of the 17 SNPs do not depart from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.20,21 In addition, the haplotypes of the 17 SNPs present in the 78 individuals were reconstructed, and the most likely haplotype pair was assigned for each individual using the PHASE program.22 In total, 19 haplotypes for the 17 SNPs were identified among the 78 individuals (supplemental Figure 1), indicating the presence of a relatively high recombination rate across this region. It is known that PAR1 has a cross-over rate much greater than the genome-wide average.23,24 Within these highly diverse haplotype pair combinations, the genotypes at rs311103 are consistently associated with the phenotypic polymorphisms of the Xga/CD99 blood groups across the 78 individuals. Specifically, a comparison of the RBC CD99 antigen expression levels in the individual groups according to their rs311103 genotypes showed a significant correlation between a higher level of CD99 expression and the copy number of the rs311103[G] allele (Figure 3C). These findings further support the correlation between the polymorphism in terms of rs311103 genotypes and the Xga/CD99 blood group phenotypes.

The polymorphic rs311103 genomic regions exhibit different levels of transcription-enhancing activity specifically in erythroid-lineage cells

To investigate the molecular connection between rs311103 nucleotide polymorphism and the differential transcription levels of allelic XG and CD99, we used a reporter assay to examine the transcriptional activity of the genomic regions spanning rs311103.

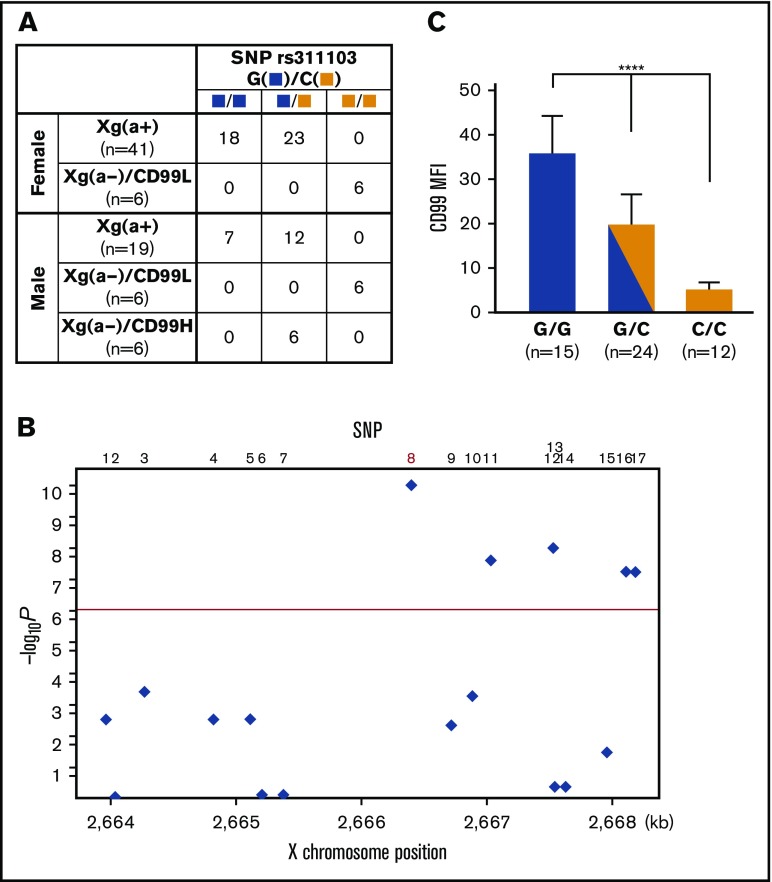

When the 200-G reporter construct, which bears a 200-bp genomic segment that encompasses rs311103[G], was introduced into K-562 erythroleukemia cells, a dramatically higher level of transcriptional activity was observed; this transcriptional activity was completely absent when a similar construct, 200-C, which had only a single G-to-C change within rs311103, was examined (Figure 4A). The reporter assays of the 62-G and 62-C constructs, which carry a 62-bp genomic region that encompassed rs311103[G] and rs311103[C], respectively, produced similar results using K-562 cells. In addition, when the erythroleukemia cell lines HEL and LAMA-84 were used as hosts for the same reporter assays, the 62-bp rs311103[G] segment also showed a high level of transcriptional activity (Figure 4B). In contrast, a similar induction of transcriptional activity by this 62-bp rs311103[G] segment was not observed in the nonerythroid lineage cell lines HEK293T and DLD-1. These findings strongly suggest that the rs311103[G] genomic region possesses a high transcription-enhancing activity with an erythroid lineage-specific characteristic.

Figure 4.

Erythroid lineage–specific character of the transcriptional activity of rs311103[G] genomic region. (A) Transcriptional activity levels of the reporter constructs bearing different genotypes at SNP rs311103 in K-562 cells. The reporter constructs 200-G and 200-C carry the 200-bp genomic regions, which encompass rs311103; the rs311103 sites of these constructs bear the G and C nucleotides, respectively. Similarly, the 62-G and 62-C reporter constructs carry the 62-bp genomic regions that encompass rs311103[G] and rs311103[C], respectively. The relative luminescence measurements obtained from each experiment were normalized against the level of β-galactosidase activity in the same cells. The results are presented as fold changes in the mean of luminescence units obtained from triplicate experiments relative to that obtained from the empty pGL4.23 reporter vector (p4.23); the error bars indicate the standard deviations. (B) The erythroid lineage–specific character of the transcriptional activity of rs311103[G] genomic region. The 62-G and 62-C reporter constructs and the empty pGL4.23 vector were transfected into human erythroleukemia cell lines HEL and LAMA-84 and into human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T and human colon cancer cell line DLD-1.

Erythroid GATA factors induce the transcriptional activity of the rs311103[G] region

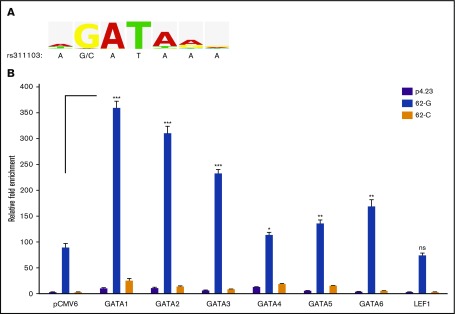

The polymorphic rs311103 genomic regions were analyzed using TRANSFAC (geneXplain) to identify potential transcription factor binding motifs. Putative binding motifs for the GATA binding protein family (Figure 5A) and for lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF1) (data not shown) were identified within the rs311103[G] region but not within rs311103[C] region. To explore any relevant effect, LEF1 and the 6 known members of the GATA family (GATA1-GATA6) were ectopically expressed in K-562 cells that had been transfected with the 62-G or 62-C reporter construct. The results showed that expression of each of the 6 GATA members, but not of the LEF1 factor, was able to significantly elevate the transcriptional activity of the rs311103[G] segment (Figure 5B). Specifically, the hematopoietic GATA factors, GATA1-GATA3, were found to give rise to a much greater induction of the transcription-enhancing activity than the other 3 GATA factors; this effect was most noticeable for GATA1.

Figure 5.

Effects of the erythroid GATA factors on the transcriptional activity of rs311103[G] genomic region. (A) Consensus sequence for the GATA transcription factor family. The sequence logo, derived from the V$GATA_Q6 matrix report in TRANSFAC, graphically displays the nucleotide frequencies in the binding motif of the GATA transcription factor family. The genomic sequence spanning SNP rs311103 is shown below. The V$GATA_Q6 matrix was constructed based on 105 sequence entries for the genomic binding sites of various GATA1-GATA6 factors from human, mouse, rat, and chicken, and the constructed binding motif of the matrix consisted of a consensus sequence, WGATAR, for the GATA family. The G nucleotide at the second position of this consensus occurred at a high frequency of 98% (103 sequence entries), whereas none of the 105 sequence entries had the C nucleotide at that position. (B) Effects of the GATA family, GATA1-GATA6, and LEF1 transcription factors on the transcriptional activities of 62-G and 62-C reporter constructs. The expression vectors for GATA1-GATA6 and LEF1 and the empty pCMV6 vector were cotransfected with the 62-G or 62-C reporter constructs or the empty pGL4.23 vector (p4.23) into the host K-562 cells. Relative luminescence measurements obtained from each experiment were normalized against β-galactosidase activity. The results are presented as the fold change in the mean of luminescence units obtained from triplicate experiments relative to that obtained from the cells transfected with empty pCMV6 and pGL4.23 vectors; the error bars indicate the standard deviations. Statistical analyses between the 62-G reporter result obtained from the pCMV6 control group and each of the 62-G reporter results obtained from the GATA1-GATA6 and LEF1 expression groups were performed using the unpaired t test with the Welch correction. ***P <.001, **P <.01, *P < .05. ns, nonsignificant.

The expression levels of the GATA1-GATA6 transcripts and the LEF1 transcript in the erythroleukemia cell lines and the nonerythroid lineage cell lines that were used for these experiments were quantitatively analyzed (supplemental Figure 2). GATA1 and GATA2 are known to be crucial factors for the development of erythroid-lineage cells; thus, considerable amounts of the GATA1 and GATA2 transcripts and proteins were found to be present in the erythroleukemia cell lines K-562, HEL, and LAMA-84, as would be expected. This contrasts with the situation within the nonerythroid cell lines HEK293T and DLD-1, in which the expression levels of the GATA1 and GATA2 transcripts were found to be very low. The expression levels of the other transcription factors (ie, GATA3-GATA6 and LEF1) in the erythroleukemia cell lines were also very low or virtually undetectable. These findings suggest that the high transcriptional activity of the rs311103[G] segment that was specifically found in erythroid-lineage cells is likely to be substantially due to the presence of high levels of these 2 erythroid GATA factors (GATA1 and GATA2) in these cells.

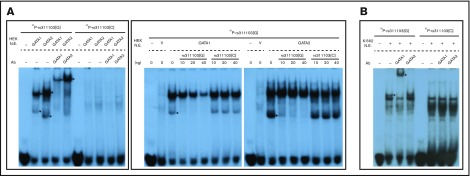

GATA1 binds specifically to the rs311103[G] region

Next, EMSA was carried out to examine the binding of the GATA1 and GATA2 factors to the polymorphic rs311103 genomic segments. As shown in Figure 6A (left panel), there was specific binding of GATA1 and GATA2 to the rs311103[G] DNA fragment, but such binding was virtually absent when the rs311103[C] fragment was used. Competition experiments using unlabeled rs311103[G] and rs311103[C] fragments further demonstrated that a G-to-C nucleotide change at rs311103 position virtually abolishes the affinity of GATA1 and GATA2 for the genomic region in question (Figure 6A, right panel).

Figure 6.

The specific binding of the erythroid GATA1 factor to the rs311103[G] DNA fragment. (A) Nuclear extracts were prepared from HEK293T cells (HEK N.E.) transfected with expression vectors for GATA1 or GATA2 or with the empty pCMV6 vector (V). These were then incubated with 1 ng of 32P-labeled 22-bp rs311103[G] or rs311103[C] DNA fragment with and without the addition of antibody (Ab) against GATA1 or GATA2 (left panel). The shifted and supershifted bands are indicated with asterisks (right panel). Unlabeled rs311103[G] or rs311103[C] DNA fragments (10, 20, or 40 ng) were added to compete with the 32P-labeled rs311103[G] fragment (right panel). (B) Binding of endogenous GATA1 factor to the rs311103[G] DNA fragment. Nuclear extracts prepared from native K-562 cells (K-562 N.E.) were used.

When nuclear extracts prepared from native K-562 cells were used, specific binding of the endogenous GATA1 factor in K-562 cells to the rs311103[G] fragment was found (Figure 6B). However, binding of the endogenous GATA2 factor, which is also present in K-562 cells in large amounts, to rs311103[G] was not observed.

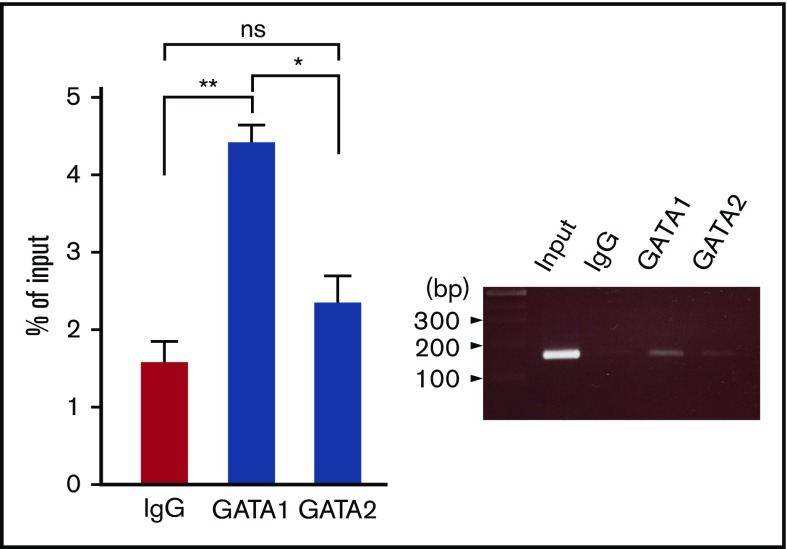

The in vivo binding status of GATA1 and GATA2 to the rs311103 regions was assessed using ChIP analysis. The results demonstrated that there was an association of GATA1 with the rs311103 genomic region in HEL erythroleukemia cells; however, under the same circumstances, the association of GATA2 to the rs311103 region was not significant (Figure 7). The ChIP results agree well with the results obtained from the EMSA experiments and show that endogenous GATA1, but not endogenous GATA2, is able to bind to the rs311103 segment.

Figure 7.

Association of the GATA1 factor with the SNP rs311103 genomic region in vivo. The association status of the endogenous GATA1 and GATA2 transcription factors with the rs311103 genomic region in HEL erythroleukemia cells was examined using ChIP analysis. The amount of the genomic segment spanning rs311103 present in the chromatin DNA immunoprecipitated with anti-GATA1 antibody, anti-GATA2 antibody, or normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and the input DNA samples were quantitatively compared using real-time PCR (left panel). The results were obtained from 3 independent experiments and are presented as percentages of the amount of the rs311103 segments in the input DNA sample; the error bars indicate the standard deviations. The statistical differences between GATA1 and IgG and between GATA2 and IgG were analyzed using the unpaired t test. A gel image of a 2.0% agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of the PCR products is shown (right panel). **P < .01, *P < .05.

Examination of the ChIP sequencing data from primary human erythroblasts in the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements databank using the UCSC Genome Browser manifested significant binding of the GATA1 factor to the rs311103 region (supplemental Figure 3A). This further substantiates the proposal that there is substantial binding of GATA1 to the SNP region in erythroid-lineage cells. The ChIP sequencing data also show binding of GATA1 to the XG and CD99 promoter regions in primary human erythroblast cells (supplemental Figure 3B).

Discussion

During the present study, a pilot investigation was carried out that used targeted NGS, and this was followed by an association study that was able to demonstrate a definite association between SNP rs311103 and the Xga/CD99 blood groups. Our results indicate that the rs311103[G] and rs311103[C] alleles on the X chromosome are responsible for the Xg(a+)/CD99H and Xg(a−)/CD99L phenotypes, respectively, and the rs311103[G] allele on the Y chromosome is responsible for the Xg(a−)/CD99H phenotype in males. The SNP rs311103 is located between XG and CD99 and is situated at a position 3.7 kb upstream and 57 kb downstream of the transcription start sites of XG and CD99, respectively (Figure 2). It is located in the PAR1 region of the X and Y chromosomes; this agrees with the previous proposition that the postulated XG Regulator element should be situated within the PAR area.6,15 The frequencies of the XG(a+) gene have been calculated using Xga phenotype frequencies in various populations.7,25-27 These findings were compared with the rs311103[G] frequencies available from the HapMap databank; the latter results were found to parallel well with the calculated XG(a+) frequencies (supplemental Table 4).

It has been pointed out that the Xga/CD99 blood groups are erythroid specific. The present investigation reveals that the rs311103[G] genomic region, but not the rs311103[C] region, brings about a high level of transcriptional enhancement that is specific to erythroid-lineage cells. In addition, our results show how GATA factors are important to the induction of the transcriptional activity of the rs311103[G] region. The high frequency of the G nucleotide at the second position of the GATA-binding consensus WGATAR (Figure 5A) points to how critical this G nucleotide is to the binding of GATA transcription factors. This situation also provides an explanation for the dramatic contrast in transcriptional activity between the rs311103[G] and rs311103[C] genomic segments in erythroid-lineage cells. Via the transcription-activation function of the erythroid GATA factors, the rs311103 G/C variation present in the human population results in significant differences in the transcription-enhancer activity of the rs311103 genomic regions in erythroid lineage between individuals, consequently leading to the different Xga/CD99 blood group phenotypes.

Among human blood groups, cis-regulatory SNPs have been identified that are associated with the P1/P2 phenotypes of the P1PK blood group system.18 Recently, the transcription factors involved in differential binding to this polymorphic SNP region have been proposed to control the differential activation of P1-A4GALT and P2-A4GALT expression in P1 and P2 red cells.19,28 The present investigation provides another example of a human blood group quantitative trait that involves a SNP cis-linked to the genes responsible for the phenotype. In addition, disruption of a GATA1 motif by a genetic variant (rs2814778) has been identified in the FY (ACKR1) gene promoter region of Africans with the Duffy-negative phenotype.29 This disruption abolishes the expression of the Duffy blood group antigens on RBCs; as a consequence, this confers resistance to invasion by Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium knowlesi malarial parasites.30,31 The present study, the Duffy-negative phenotype findings, and various forms of congenital anemia32-35 show the profound effect that disruption of a canonical GATA1-binding motif can have on the expression of the target genes in RBCs. In this context, it is of interest to note that other common genetic variants associated with RBC traits do frequently alter GATA1 regulatory elements; in these cases, they do not act by critically disrupting the canonical core-binding motif, but rather change the sequences flanking the core-binding motif. These changes subtly alter the binding/activity of GATA1 and various cofactors, which can result in mild changes in the expression level of the target genes.36,37

The expression of the Xga antigen appears to be restricted to a limited number of cell types, such as RBCs, and the expression levels of this antigen are relatively low. The expression of the Xga antigen in Ewing’s sarcoma has been shown to contribute to the tumor invasiveness and to be of prognostic value.38 In contrast to Xga, CD99 is abundantly expressed in a wide range of tissues and has drawn considerable attention in recent years.39-41 CD99 has been recognized to be 1 of the critical molecules involved in the leukocyte transendothelial migration signaling pathway; thus, it plays an important role in the recruitment of leukocytes into inflamed areas.39,42,43 Particularly, subsets of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells with high or low CD99 expression levels have been identified; these subsets have different levels of transendothelial migration activity and show variation in the numbers of blood cells of several downstream lineages produced after differentiation.44 In addition, CD99 has been demonstrated to act as a surface marker for the stem and progenitor cells during acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome and to be a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of both.40,45 In view of the crucial cellular and pathological roles played by CD99, it will be of interest in the future to explore whether the rs311103 common genetic variation investigated here leads to different levels of CD99 expression in other cell types, just like in RBCs. Of particular interest would be cells in which members of the GATA family are involved in development; 1 possible outcome of this research would be the identification of different physiopathological conditions in individual groups carrying the different SNP genotypes.

Among the 6 members of the GATA family, it has been established that GATA2 is critical to the generation and functioning of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, including early erythroid precursor cells. Furthermore, GATA1 is essential to the development of the erythroid lineage and the regulation of RBC differentiation.46,47 Specifically, the 2 erythroid-related GATA factors are 2 out of 6 GATA factors that are able to induce the greatest amount of transcriptional activity via the rs311103[G] segment (Figure 5B). Nonetheless, the EMSA results using K-562 nuclear extracts, as well as the ChIP analysis, suggest that GATA1, but not GATA2, is involved in the differential transcriptional activity of the rs311103[G] and rs311103[C] segments. Further studies are required to verify this. In addition, as the genetic basis for the Xga/CD99 blood groups, the rs311103 region must be involved in the coregulation of XG and CD99 expression in erythroid-lineage cells. Furthermore, the rs311103[G] region needs to have the ability to interact over a long distance to influence the CD99 promoter and affect the transcription of CD99. It should be noted that the recognition and binding between a specific protein factor and its DNA binding motif, followed by subsequent transcription, is a highly complex event and often involves many other protein factors. Indeed, various transcription factors and cofactors have been shown to associate with the GATA1 and GATA2 factors and to be involved in the regulation of the activation/repression functions of GATA1/GATA2 with respect to erythroid gene expression.46-49 Some of these factors have been identified as being capable of mediating long-range interactions between the enhancers and the promoters of erythroid genes.50-52 Further studies are needed to delineate the molecular details associated with the allelic variation in expression of the XG and CD99 genes with respect to the rs311103[G] and rs311103[C] alleles. It will be of particular interest to further explore the functions of specific erythroid GATA factors and any other factors that are found to be associated with them. This will involve investigating the details of the regulation system, especially the involvement of these factors in the long-range interaction between the rs311103[G] genomic region and the CD99 promoter and in the coregulation of XG and CD99 expression.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grants MOST 104-2320-B-002-031 and MOST 104-2321-B-002-073 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

Authorship

Contribution: C.-C.Y. designed and performed the research, collected the data, analyzed the data, and interpreted the data; C.-J.C. and Y.-C.T. performed the research and interpreted the data; C.-C.C. analyzed the data; B.-S.L., J.-T.H., S.-T.H., Y.-S.C., and Y.-J.T. performed the research; S.-W.L. and M.L. contributed the analytical tools; and L.-C.Y. designed the research, collected the data, analyzed the data, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lung-Chih Yu, Institute of Biochemical Sciences, College of Life Science, National Taiwan University, No. 1, Roosevelt Rd Sec. 4, Taipei 106, Taiwan; e-mail: yulc@ntu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Mann JD, Cahan A, Gelb AG, et al. A sex-linked blood group. Lancet. 1962;1(7219):8-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodfellow PN, Tippett P. A human quantitative polymorphism related to Xg blood groups. Nature. 1981;289(5796):404-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fouchet C, Gane P, Cartron J-P, Lopez C. Quantitative analysis of XG blood group and CD99 antigens on human red cells. Immunogenetics. 2000;51(8-9):688-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herron R, Smith GA. Identification and immunochemical characterization of the human erythrocyte membrane glycoproteins that carry the Xga antigen. Biochem J. 1989;262(1):369-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouchet C, Gane P, Huet M, et al. A study of the coregulation and tissue specificity of XG and MIC2 gene expression in eukaryotic cells. Blood. 2000;95(5):1819-1826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tippett P, Ellis NA. The Xg blood group system: a review. Transfus Med Rev. 1998;12(4):233-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels G. Human Blood Groups. 3rd ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis NA, Tippett P, Petty A, et al. PBDX is the XG blood group gene. Nat Genet. 1994;8(3):285-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darling SM, Banting GS, Pym B, Wolfe J, Goodfellow PN. Cloning an expressed gene shared by the human sex chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(1):135-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tippett P, Shaw M-A, Green CA, Daniels GL. The 12E7 red cell quantitative polymorphism: control by the Y-borne locus, Yg. Ann Hum Genet. 1986;50(Pt 4):339-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weller PA, Critcher R, Goodfellow PN, German J, Ellis NA. The human Y chromosome homologue of XG: transcription of a naturally truncated gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4(5):859-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawler SD, Sanger R. Xg blood-groups and clonal-origin theory of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet. 1970;1(7647):584-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fialkow PJ, Lisker R, Giblett ER, Zavala C. Xg locus: failure to detect inactivation in females with chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1970;226(5243):367-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodfellow P, Pym B, Mohandas T, Shapiro LJ. The cell surface antigen locus, MIC2X, escapes X-inactivation. Am J Hum Genet. 1984;36(4):777-782. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodfellow PJ, Pritchard C, Tippett P, Goodfellow PN. Recombination between the X and Y chromosomes: implications for the relationship between MIC2, XG and YG. Ann Hum Genet. 1987;51(Pt 2):161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Möller M, Lee YQ, Vidovic K, et al. Disruption of a GATA1-binding motif upstream of XG/PBDX abolishes Xga expression and reveals the Xg blood group system. Blood. 2018;132(3):334-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy R, Dilley J, Fox RI, Warnke R. A human thymus-leukemia antigen defined by hybridoma monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76(12):6552-6556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Y-J, Wu W-Y, Yang C-M, et al. A systematic study of SNPs in the A4GALT gene suggests a molecular genetic basis for the P1/P2 blood groups. Transfusion. 2014;54(12):3222-3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh C-C, Chang C-J, Twu Y-C, et al. The differential expression of the blood group P1 -A4GALT and P2-A4GALT alleles is stimulated by the transcription factor early growth response 1. Transfusion. 2018;58(4):1054-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayo O. A century of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2008;11(3):249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Shete S.. Testing departure from Hardy-Weinberg proportions. Methods Mol Biol 2017;1668:83-115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Stephens M, Donnelly P. A comparison of bayesian methods for haplotype reconstruction from population genotype data. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(5):1162-1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flaquer A, Rappold GA, Wienker TF, Fischer C. The human pseudoautosomal regions: a review for genetic epidemiologists. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(7):771-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hinch AG, Altemose N, Noor N, Donnelly P, Myers SR. Recombination in the human pseudoautosomal region PAR1. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(7):e1004503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewey WJ, Mann JD. Xg blood group frequencies in some further populations. J Med Genet. 1967;4(1):12-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanger R, Tippett P, Gavin J. The X-linked blood group system Xg. Tests on unrelated people and families of northern European ancestry. J Med Genet. 1971;8(4):427-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakajima H, Murata S, Senõ T. Three additional examples of anti-Xga and Xg blood groups among the Japanese. Transfusion. 1979;19(4):480-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westman JS, Stenfelt L, Vidovic K, et al. Allele-selective RUNX1 binding regulates P1 blood group status by transcriptional control of A4GALT. Blood. 2018;131(14):1611-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tournamille C, Colin Y, Cartron JP, Le Van Kim C. Disruption of a GATA motif in the Duffy gene promoter abolishes erythroid gene expression in Duffy-negative individuals. Nat Genet. 1995;10(2):224-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller LH, Mason SJ, Dvorak JA, McGinniss MH, Rothman IK. Erythrocyte receptors for (Plasmodium knowlesi) malaria: Duffy blood group determinants. Science. 1975;189(4202):561-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH. The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(6):302-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manco L, Ribeiro ML, Máximo V, et al. A new PKLR gene mutation in the R-type promoter region affects the gene transcription causing pyruvate kinase deficiency. Br J Haematol. 2000;110(4):993-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solis C, Aizencang GI, Astrin KH, Bishop DF, Desnick RJ. Uroporphyrinogen III synthase erythroid promoter mutations in adjacent GATA1 and CP2 elements cause congenital erythropoietic porphyria. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(6):753-762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaneko K, Furuyama K, Fujiwara T, et al. Identification of a novel erythroid-specific enhancer for the ALAS2 gene and its loss-of-function mutation which is associated with congenital sideroblastic anemia. Haematologica. 2014;99(2):252-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campagna DR, de Bie CI, Schmitz-Abe K, et al. X-linked sideroblastic anemia due to ALAS2 intron 1 enhancer element GATA-binding site mutations. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(3):315-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sankaran VG, Ludwig LS, Sicinska E, et al. Cyclin D3 coordinates the cell cycle during differentiation to regulate erythrocyte size and number. Genes Dev. 2012;26(18):2075-2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulirsch JC, Nandakumar SK, Wang L, et al. Systematic functional dissection of common genetic variation affecting red blood cell traits. Cell. 2016;165(6):1530-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meynet O, Scotlandi K, Pradelli E, et al. Xg expression in Ewing’s sarcoma is of prognostic value and contributes to tumor invasiveness. Cancer Res. 2010;70(9):3730-3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hickey MJ. CD99: An endothelial passport for leukocytes. J Exp Med. 2015;212(7):977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kingwell K. Cancer: CD99 marks malignant myeloid stem cells. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(3):166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pasello M, Manara MC, Scotlandi K. CD99 at the crossroads of physiology and pathology. J Cell Commun Signal. 2018;12(1):55-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bixel G, Kloep S, Butz S, Petri B, Engelhardt B, Vestweber D. Mouse CD99 participates in T-cell recruitment into inflamed skin. Blood. 2004;104(10):3205-3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson RL, Buck J, Levin LR, et al. Endothelial CD99 signals through soluble adenylyl cyclase and PKA to regulate leukocyte transendothelial migration. J Exp Med. 2015;212(7):1021-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Imbert A-M, Belaaloui G, Bardin F, Tonnelle C, Lopez M, Chabannon C. CD99 expressed on human mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells is involved in transendothelial migration. Blood. 2006;108(8):2578-2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chung SS, Eng WS, Hu W, et al. CD99 is a therapeutic target on disease stem cells in myeloid malignancies. Sci Transl Med 2017;9(374):eaaj2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Hewitt KJ, Johnson KD, Gao X, Keles S, Bresnick EH. The hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell cistrome: GATA factor-dependent cis-regulotory mechanisms. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2016;118:45-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeVilbiss AW, Tanimura N, McIver SC, Katsumura KR, Johnson KD, Bresnick EH. Navigating transcriptional coregulatory ensembles to establish genetic networks: a GATA factor perspective. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2016;118:205-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodriguez P, Bonte E, Krijgsveld J, et al. GATA-1 forms distinct activating and repressive complexes in erythroid cells. EMBO J. 2005;24(13):2354-2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakabayashi A, Ulirsch JC, Ludwig LS, et al. Insight into GATA1 transcriptional activity through interrogation of cis elements disrupted in human erythroid disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(16):4434-4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li L, Freudenberg J, Cui K, et al. Ldb1-nucleated transcription complexes function as primary mediators of global erythroid gene activation. Blood. 2013;121(22):4575-4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Love PE, Warzecha C, Li L. Ldb1 complexes: the new master regulators of erythroid gene transcription. Trends Genet. 2014;30(1):1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krivega I, Dale RK, Dean A. Role of LDB1 in the transition from chromatin looping to transcription activation. Genes Dev. 2014;28(12):1278-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.