Abstract

In contrast to the large number of studies investigating the electrophysiological properties and synaptic connectivity of hippocampal pyramidal neurons, granule cells, and GABAergic interneurons, much less is known about Cajal-Retzius cells. In this review article, we discuss the possible reasons underlying this difference, and review experimental work performed on this cell type in the hippocampus, comparing it with results obtained in the neocortex. Our main emphasis is on data obtained with in vitro electrophysiology. In particular, we address the bidirectional connectivity between Cajal-Retzius cells and GABAergic interneurons, examine their synaptic properties and propose specific functions of Cajal-Retzius cell/GABAergic interneuron microcircuits. Lastly, we discuss the potential involvement of these microcircuits in critical physiological hippocampal functions such as postnatal neurogenesis or pathological scenarios such as temporal lobe epilepsy.

Keywords: GABA, glutamate, synapse, reelin, epilepsy, neurogenesis

1. Introduction

Modern textbooks and review articles describing the synaptic connectivity of the hippocampal network consider usually only three main neuronal populations: pyramidal and granule cells (both glutamatergic and excitatory in nature), and a large heterogeneous group of “inhibitory” GABAergic interneurons (Freund and Buzsaki, 1996; Spruston and McBain, 2007; Pelkey et al., 2017). Our most recent knowledge on the morphofunctional connectivity between these three cell ensembles is based on experiments performed on rodent hippocampal slices in vitro. In fact, in addition to seminal work performed with classic intracellular recordings (reviewed by Miles and Wong, 1991), the development of visually-guided patch-clamp measurements on preselected neurons (coupled to post-hoc anatomical recovery) has unleashed the power of high-resolution whole-cell recordings for the study of cell type-specific synaptic transmission and membrane excitability (Booker et al., 2014). However, an interesting point to consider is that most patch-clamp data have yielded snapshots of a still immature network, slowly transitioning to a more adult-like stage. In fact, although technical improvements in the slicing procedure now allow patch-clamp recordings even in tissue obtained from aging rodents (Moyer and Brown, 1998; Geiger et al., 2002), the last two weeks of the first postnatal month have long been (and still are) considered the golden period to obtain the best preparations for visually-guided electrophysiological measurements. Surprisingly, despite the wealth of studies focusing on the three aforementioned cellular populations (i.e., pyramidal, granule cells, and GABAergic interneurons), a fourth group of cortical neurons (Cajal-Retzius cells) has received much less attention from hippocampal electrophysiologists. Thus, for a long time, models of hippocampal synaptic integration and fast information processing have ignored the impact of this latter population. Prominent reviews article have described Cajal-Retzius cells as a “mystery” or even “mystic” neurons (Soriano and Del Río, 2005; Kirischuk et al., 2014).

Here, our purpose is to provide readers with an updated view on hippocampal layer-specific connectivity that incorporates recent physiological studies in vitro addressing the potential role of Cajal-Retzius cell/GABAergic interneuron microcircuits in the regulation of the developing postnatal hippocampus.

2. Hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cell and electrophysiology: a brief history of an initially difficult encounter

We will not address here a general historical perspective on the discovery of Cajal-Retzius cells and will redirect the readers to excellent reviews already available (Gil et al., 2014; Martínez-Cerdeño and Noctor, 2014). We will just mention that the realization that Cajal-Retzius cells are an individual and specific cell type was a long and difficult process, hampered both by technical and conceptual hurdles, as these cells show increasing levels of morphological complexity when studied and compared, as it happened, in different mammalian species (Meyer et al., 1999). However, despite these potential experimental confounds and variability, the combination of modern anatomical (Radnikow et al., 2002; Sava et al., 2010; Anstötz et al., 2016), immunohistochemical (Ogawa et al., 1995; del Río et al., 1995; Martínez-Galán et al., 2001; Stumm et al., 2002; Borrell and Marin, 2006; Anstötz et al., 2016, 2018) and genetic techniques (Soda et al., 2003; Bielle et al., 2005; Tissir et al., 2009; Chowdhury et al., 2010; Gil-Sanz et al., 2013; Anstötz et al., 2018) allows clear criteria for their unequivocal identification.

Electrophysiologists can easily recognize Cajal-Retzius cells in living neocortical slices prepared from young rodent pups, roughly up to the second postnatal week (Zhou and Hablitz, 1996; Kilb and Luhmann, 2000; Luhmann et al., 2000; Chan and Yeh, 2003; Kirmse et al., 2005 Cheng et al., 2006; Kirmse et al., 2006; Cosgrove and Maccaferri, 2012). In particular, these neurons occupy the marginal zone/layer I, and are oriented parallel to the pial surface. Structurally, they display a typical tadpole-like morphology, with a variable degree of dendritic complexity, and with the axon emerging from the opposite side of the main dendritic trunk. Several studies have used these simple, but very effective, criteria to record visually-identified neocortical Cajal-Retzius cells, thus allowing the study of their membrane properties/conductances (Zhou and Hablitz, 1996; Hestrin and Armstrong, 1996; Mienville and Barker, 1997; Kilb and Luhmann, 2000; Luhmann et al., 2000; Radnikow et al., 2002; Kirmse et al., 2005) and firing patterns (Zhou and Hablitz, 1996; Hestrin Armstrong, 1996; Luhmann et al., 2000; Radnikow et al., 2002; Kirmse et al., 2005). In addition, the discovery of an apparent absence of spontaneous glutamatergic synaptic events (Kilb and Luhmann, 2001; Soda et al., 2003; Kirsme and Kirischuk, 2006, Cosgrove and Maccaferri, 2012), suggested a critical role of GABAergic input for their integrative functions (Mienville, 1998; Kirmse et al., 2007; Dvorzhak et al., 2010).

Although Cajal-Retzius cells are abundant and easy to find in neocortical slices prepared at early developmental stages, they become extremely rare in tissue obtained after the second postnatal week, making electrophysiological studies of their roles and properties at more developed neocortical stages unpractical. Several hypotheses regarding their progressive disappearance have been proposed (Marin-Padilla, 1990; Parnavelas and Edmunds, 1983; Sarnat and Flores-Sarnat 2002; Derer and Derer, 1990). However, it seems now reasonably established that this phenomenon reflects a developmentally-driven apoptotic process (Derer and Derer 1990; del Río et al., 1995; Naqui et al., 1999; Tissir et al., 2009; Chowdhury et al., 2010; Anstötz et al., 2014, 2016; Ledonne et al., 2016).

As previously mentioned, most patch-clamp studies in the hippocampus are commonly performed on slices obtained from animals older than the second postnatal week. It is likely that most electrophysiologists ignored Cajal-Retzius cells in this region because they just assumed that these neurons would disappear, similarly to what was described in neocortical networks. Despite this being a “psychologically-plausible” explanation, we think that additional factors might have played a role. In fact, anatomical/immunohistochemical evidence for a prolonged persistence of Cajal-Retzius cells in the hippocampus (compared to the neocortex, see Del Río et al., 1996 and Supèr et al., 1998) was available, but not routinely taken into account by electrophysiological studies.

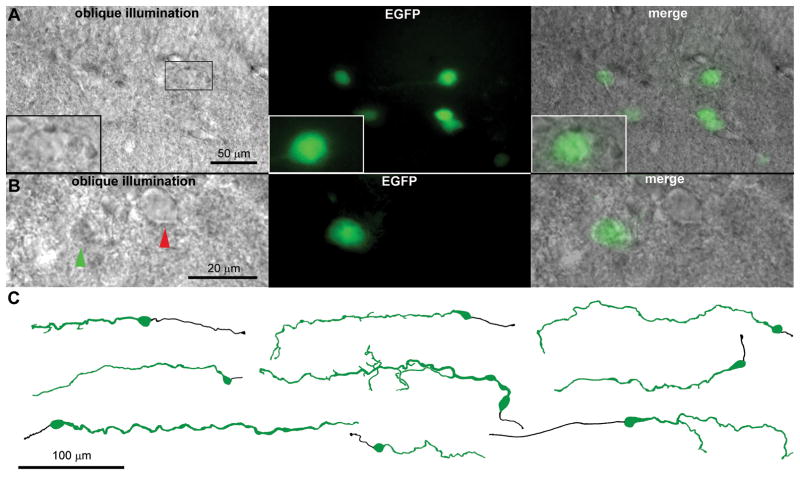

We suppose that the most important factor explaining this surprising lack of attention may be related to the conventional wisdom that guides electrophysiologists in the choice of their target neurons. Since the development of visually-guided patch-clamp in slices, efforts were directed to recognize healthy cells that would offer the best opportunities for stable membrane seals and prolonged recordings. The ideal targets for electrophysiological recording display a smooth and clean surface, with usually recognizable somatic emergences of their main dendritic processes (Edwards and Konnerth, 1992). Hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells visualized in a living slice appear different from other neurons, have a flat-looking appearance and a non-homogenous membrane surface (Figures 1A, B, and C). These are all considered predictors of difficulty in obtaining a high-resistance seal and/or stable recordings. In fact, it would seem almost inconceivable that no chance encounters between patch-clamp electrodes and Cajal-Retzius cells were ever reported by studies measuring the properties of hippocampal interneurons of the molecular layers (Atzori, 1996; Isa et al., 1996; Morin et al., 1996; Baraban et al., 1997; Ceranik et al., 1997; Morin et al., 1998; Chapman and Lacaille, 1999; McQuiston and Madison, 1999; Alkondon et al., 2000; Alkondon and Albuquerque, 2001; Price et al., 2005; Zsiros and Maccaferri, 2005; Zsiros et al., 2007; Elfant et al., 2008; Ascoli et al., 2009; Bell et al., 2011; Anderson et al., 2011; Armstrong et al., 2011; Markwardt et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2015; Hsu et al., 2016; Wyskiel and Andrade, 2016). We think that the combination of the previously discussed assumption regarding their disappearance with their peculiar and unhealthy-looking appearance is possibly the main motive explaining the long-lasting lack of electrophysiological data for this cell type in the hippocampus. In contrast, for reasons that we still don’t understand, neocortical Cajal-Retzius cells do not have this peculiar, unattractive look.

Figure 1.

Cajal-Retzius cells in a living hippocampal slice from CXCR4-EGFP transgenic mice. (A) Left panel: notice the apparent unhealthy aspect of a group of Cajal-Retzius cells visualized in the hippocampal fissure region between stratum lacunosum-moleculare and the outer molecular layer of the dentate gyrus. An individual neuron is shown at increased magnification, the boxes indicate the corresponding regions. Notice the flat, glial-like, appearance and the non-smooth/non-homogeneous membrane, which make it difficult to distinguish the soma from the background (oblique illumination). Middle panel: fluorescent image of the same slice for EGFP. Right panel: overlapping the two images allows the easy localization of Cajal-Retzius cells. P20 mouse. Unpublished observation. (B) Similar to (A) in a P7 animal. Notice the different appearance of a Cajal-Retzius cell (green arrowhead) compared to a nearby interneuron (red arrowhead). Unpublished observation. (C) Camera lucida tracing of several biocytin-filled EGFP-expressing neurons. Notice the tadpole-like appearance with the main dendrite (green) and the axon (black) emerging from opposite sides of the soma. Modified with with permission from Marchionni et al. (2010), © John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

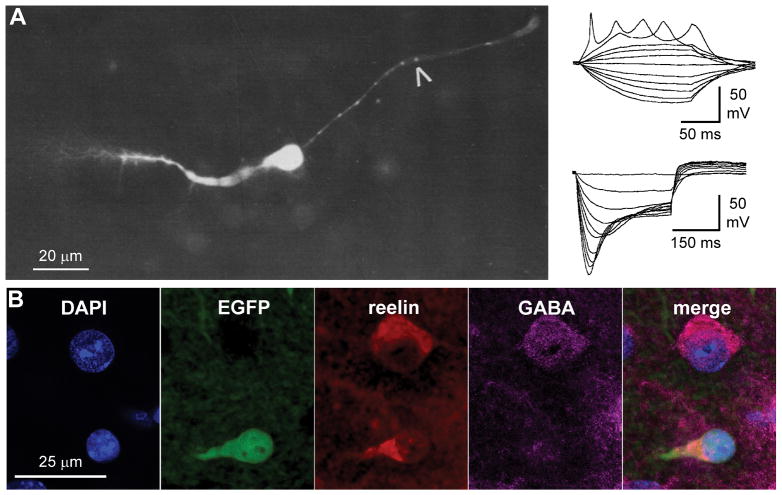

To our knowledge, the first electrophysiological recording of a Cajal-Retzius cell in the hippocampus was performed by von Haebler et al. (1993). In a study designed to “investigate the innervation pattern of CA3 pyramidal cells by mossy fibers during ontogenesis”, these authors discovered, serendipitously, that “small crystals of dextran-amines injected into the cell-sparse stratum moleculare of the dentate gyrus […] stained cells of bipolar appearance, with extensions running parallel to the stratum granulare and the hippocampal fissure” and decided to characterize the membrane properties and excitability of these newly (re)discovered neurons (von Haebler et al., 1993, Figure 2A). Both the typical morphological and electrophysiological properties reported in their study would indicate today that these neurons were indeed, Cajal-Retzius cells. However, the identification was not conclusive and several alternative possibilities, such as displaced granules or radial glia cells, were proposed. The next published patch-clamp studies of Cajal-Retzius cells came from the Frotscher group (Ceranik et al., 1999, 2000). These authors reported the morphology and basic electrophysiological properties of hippocampal neurons, which they termed “presumed” Cajal-Retzius cells, as the main criterion for their identification was their reelin expression and location in the molecular layers of cultured and acute slices (from young rat pups, P4–P10, Ceranik et al., 1999). Heterogeneity was found, as some cells showed properties that nowadays we would attribute to Cajal-Retzius cells, whereas others displayed features that would suggest they were GABAergic interneurons (Ceranik et al., 2000). These studies were extremely important for two main reasons. First, they established the typical electrophysiological features of hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells (a distinctively high membrane input resistance, a peculiar firing pattern and membrane inward rectification, von Haebler et al., 1993; Ceranik et al., 2000) as well as their long-range connectivity to extra-hippocampal regions (Ceranik et al., 1999). Second, these studies showed that the identification of Cajal-Retzius cells in living rodent hippocampal slices (from wildtype animals) is an extremely difficult and laborious process. Heineman’s group (van Haebeler et al., 1993) only included electrophysiological data from lucifer yellow-filled cells with tadpole-like morphology, and discarded the majority of the data obtained from neurons with different morphology or unsuccessfully stained. Ceranik et al. (1999, 2000), in addition to the layer-specific location of the recorded cells, evaluated the presence of reelin by single cell (RT)-PCR or immunocytochemistry, as Cajal-Retzius cells are a critical cellular source of this important glycoprotein (Ogawa et al., 1995; Del Río et al., 1997). However, as reelin is also produced by some of the GABAergic interneurons that can be found in the molecular layers (Pesold et al., 1998; Fuentealba et al., 2010; Krook-Magnuson et al., 2011; Anstötz et al., 2016, see Figure 2B), neurons in this study were carefully referred to as “presumed” Cajal-Retzius cells.

Figure 2.

Morphology, basic electrophysiological properties and immunohistochemistry of Cajal-Retzius cells in the hippocampus. (A) Left panel: lucifer yellow-filled image of a Cajal-Retzius cell recorded by von Haebler et al. (1993) and (right panel) responses to depolarizing (top inset) and hyperpolarizing (bottom inset) current injections. Notice the typical firing pattern and the anomalous rectification in response to hyperpolarization with a prominent voltage sag. Modified with permission from von Haebler et al., (1993), © Springer Nature. (B) Reelin is not a univocal marker of Cajal-Retzius cells. Fluorescence images showing an EGFP-labeled, reelin-positive, Cajal-Retzius cells and a nearby EGFP-negative, GABA immunoreactive, interneuron. DAPI counterstaining. Notice the difference in the shape of the EGFP-expressing cell body with the typical main dendrite (compare to panel A) and the more rounded soma of the GABAergic interneuron. Modified with permission from Anstötz et al., (2016), © Oxford University Press.

An important breakthrough came with the development of the GENSAT project (Gong et al., 2003) that made mice expressing tags driven by specific genetic elements inserted into a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) publicly available. These genetically engineered animals allowed a much easier visualization of hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells in living slices, thus bypassing the hurdles faced by previous studies in rats (Figures 1A and 1B). As Cajal-Retzius express the chemokine CXCR4 receptor (Stumm et al., 2002), Marchionni et al. (2010) took advantage of the CXCR4-EGFP transgenic mouse for their identification. Their general anatomical and electrophysiological characterization confirmed and expanded the previous findings of van Haebeler et al. (1993) and Ceranik et al. (1999, 2000), and revealed a homogenous cellular population with typical tadpole-like morphology and membrane properties, which were very distinct from what observed in interneurons of the same layers (compare Figure 1C with Figure 3A). These results strongly indicated that the apparent morpho-functional dichotomy found in the “presumed” Cajal-Retzius cell population reported by Ceranik et al. (2000) was most likely due to the inclusion in their sample of reelin-expressing GABAergic interneurons, (neurogliaform cells, see Fuentealba et al., 2010; Armstrong et al., 2011; Krook-Magnuson et al., 2011 and Figure 3A).

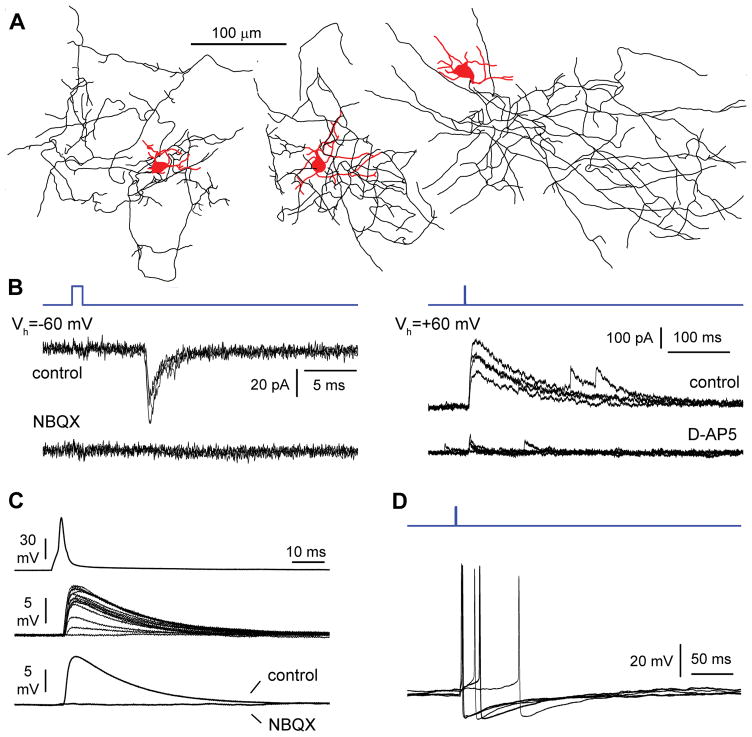

Figure 3.

Hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells are excitatory neurons that generate postsynaptic glutamatergic currents in interneurons of the molecular layers. (A) Anatomical reconstruction of physiologically-identified postsynaptic targets of optogenetically-activated Cajal-Retzius cells. Notice the multipolar dendritic arborization (red) and local axonal arborizations (black) typical of neurogliaform cells. Modifed with permission from Quattrocolo and Maccaferri (2014) under CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode). (B) A brief flash of blue light activates NBQX-sensitive AMPA-type glutamate receptor at hyperpolarized potentials (−60 mV, left panel), and D-AP5-sensitive NMDA-type glutamate receptors at depolarized potentials (+60 mV, right panel). Insets show traces in control and in the presence of the specific antagonists. Blue lines indicate the duration of the light flash. Modified with permission from Quattrocolo and Maccaferri (2014) under CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode). (C) Direct paired recording between a presynaptic Cajal-Retzius cells and a postsynaptic interneuron. Action potentials triggered by a short current injection in Cajal-Retzius cell (top traces), unitary excitatory postsynaptic potentials (middle traces) and average traces in control solution (control) and after the addition of NBQX (NBQX). Notice the complete abolishment of the excitatory postsynaptic potential by the drug. Modifed with permission from Anstötz et al., (2016), © Oxford University Press. (D) Strong optogenetic stimulation can trigger firing in interneurons. Several sweeps superimposed. Blue light indicates the duration of the flash. Modifed with permission from Quattrocolo and Maccaferri (2013) under CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

3. Are hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells GABAergic interneurons?

In order to understand the impact of a given neuronal type on a specific network, it is essential to know its anatomical connectivity and functional phenotype. The vast majority of cortical neurons in the adult brain fall into two major categories: excitatory or inhibitory neurons that use glutamate or GABA (but see Gulledge and Stuart, 2003) as major neurotransmitters, respectively. Although at early developmental stages GABA can act as an excitatory neurotransmitter (Cherubini et al., 1991), this view has been recently challenged (see both Bregestovski and Bernard, 2012 and Ben-Ari, 2012). Initial immunohistochemical evidence seemed to reveal the presence of GABA and GAD67 (an isoform of glutamate decarboxylase, which is the main synthetic enzyme for GABA, see review by Martin and Rimvall, 1993) in neocortical and hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells, respectively (Imamoto et al., 1994; Pesold et al., 1998), thus suggesting that Cajal-Retzius cells belonged to the general population of cortical GABAergic interneurons. However, identification of the immunoreactive cells in both studies was based on criteria such as layer location and reelin expression, which are not univocal for Cajal-Retzius cells. In fact, these results were not reproduced by following work (del Río et al., 1995; Soda et al., 2003; Hevner et al., 2003; Anstötz et al., 2016), and further experimental evidence tipped the balance in favor of a glutamatergic phenotype (because of glutamate immunoreactivity: del Río et al., 1995; Hevner et al., 2003, expression of VGLUT2 and specific transcription factors: Ina et al., 2007, Hevner et al., 2003).

Another major step providing critical knowledge and essential tools for the study of Cajal-Retzius cell functions was the discovery of their cell lineage and specific sites of origin during embryogenesis. Cajal-Retzius cells are originated by multiple sites at the border of the developing pallium (Meyer et al., 2002; Takiguchi-Hayashi et al., 2004; Bielle et al., 2005; Ruiz-Reig et al., 2017), and are redistributed by tangential migration. In particular, contact repulsion controls their dispersion and final distribution (Villar-Cerviño et al., 2013) so that different cortical territories are colonized primarily by Cajal-Retzius cells of a specific ontogenetic origin, which is important for the early regionalization of the cerebral cortical neuroepithelium (Griveau et al., 2010). A substantial fraction of the Cajal-Retzius cells that colonize the hippocampus is originated by the cortical hem (Yoshida et al., 2006; Tissir et al., 2009, Gu et al., 2011) and belongs to the Wnt3a lineage (Louvi et al., 2007). Therefore, the development of a Wnt3a-IRES-Cre mouse (Gil-Sanz et al., 2013) allowed electrophysiological experiments in mice (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014) expressing excitatory opsins in hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells and the direct determination of their functional effects on postsynaptic targets, such as neurogliaform interneurons (Figures 3A and 3B). Light activation of Cajal-Retzius cells triggered glutamatergic currents mediated both by AMPA- and NMDA-type receptors (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014). This result was later corroborated by paired recordings revealing large amplitude unitary glutamatergic postsynaptic potentials in interneurons of the hippocampal molecular layers (Figure 3C), finally confirming the excitatory nature of Cajal-Retzius cells (Anstötz et al., 2016). In fact, strong activation of this neuronal population is able to generate suprathreshold events in postsynaptic interneurons (Figure 3D) and trigger polysynaptic GABAergic currents onto pyramidal cells (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014). In conclusion, hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells are excitatory neurons, and the use of a single molecular marker such as reelin (in the absence of other criteria) for their identification should be avoided as it can lead to the erroneous interpretation of reelin-expressing GABAergic interneurons as Cajal-Retzius cells (as in Yu et al., 2014).

4. Synaptic GABAergic input to Cajal-Retzius cells in the neocortex and hippocampus

Virtually every neuron of the central nervous system receives both GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic inputs, which play critical and complementary roles for information processing. Surprisingly, when spontaneous postsynaptic currents were first recorded from neocortical Cajal-Retzius cells, all the observed events were blocked by GABAA receptor antagonists and no residual glutamatergic events were measured (Kilb and Luhmann, 2001; Soda et al., 2003; Kirmse and Kirischuk, 2006, Cosgrove and Maccaferri, 2012). Although direct pharmacological activation revealed that Cajal-Retzius cells express both functional AMPA- and NMDA-type glutamate receptors (Lu et al., 2001), extracellular field stimulation was able to evoke only postsynaptic potentials/currents mediated by NMDA receptors (Radnikow et al., 2002). This result is consistent with the possibility of neurotransmitter spillover (Arnth-Jensen et al., 2002), thus leaving the possibility of a conventional postsynaptic AMPA-/NMDA-type glutamate receptor-mediated potential unresolved.

Therefore, because of the apparent prominent role played by GABAergic transmission onto neocortical Cajal-Retzius cells, several studies investigated their presynaptic regulation (Kirmse and Kirischuk 2006; Kirmse et al., 2007; 2008) and functional impact on postsynaptic cellular excitability (Kolbaev et al., 2011a, 2011b; Cosgrove and Maccaferri, 2012). The presynaptic origin of GABAergic inputs to neocortical Cajal-Retzius cells includes both long-range fibers originating from subplate neurons (Myakhar et al., 2011), local neocortical interneurons such as Martinotti cells (Cosgrove and Maccaferri, 2012), and layer I unidentified interneurons (1 connection out of 80 paired recordings, see Soda et al., 2003).

Similarly to what was observed in the neocortex, hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells also receive spontaneous postsynaptic currents mediated exclusively by GABAA receptors (Marchionni et al., 2010; Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2013). Here, direct input originated by neurogliaform cells was revealed with paired recordings (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2013, Figure 4A and 4B). Unitary postsynaptic currents were mediated exclusively by GABAA receptors (in contrast to what observed in hippocampal pyramidal cells, see Price et al., 2005, 2008), and produced small-amplitude, kinetically-slow events (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2013). This result was consistent with the general idea that signaling from this class of interneurons is specialized and generates low-concentration GABA transients (Szabadics et al., 2007; Karayannis et al., 2010). However, it was also recognized that additional connections must be present, as spontaneous GABAergic events included also much larger-amplitude and kinetically-faster events. A convergence of electrophysiological, optogenetic and pharmacological evidence further indicated that somatostatin-expressing O-LM interneurons are a likely additional source of GABAergic input onto Cajal-Retzius cells (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2013, Figure 5). Thus, the connectivity motifs originally suggested in the neocortex are similar to what is observed in the hippocampus. In fact, Martinotti cells possess similar electrophysiological membrane properties, firing patterns, expression of molecular markers (somatostatin), and axonal targeting (marginal zone: layer I and molecular layers) to hippocampal O-LM cells (Paul et al., 2017). It also appears likely that the local layer I connection reported by Soda et al. (2003) was originated by a neurogliaform cell, as this interneuronal population is abundant in this layer (~30% of all neurons including Cajal-Retzius cells, according to Hestrin and Armstrong, 1996). Irrespective of its cellular origin, the impact of GABAergic input on the excitability of Cajal-Retzius cells appears complex. In general, the overall effects of GABAA receptor activation are primarily determined by the relationships between action potential threshold, the GABAA receptor-mediated current reversal potential (EGABAA) and the amplitude of the GABAA conductance (Kolbaev et al., 2011b). EGABAA in neonatal neocortical Cajal-Retzius cells in vitro has been estimated to be more depolarized that the action potential threshold (Mienville, 1998; Achilles et al., 2007; Kolbaev et al., 2011b), thus potentially supporting an excitatory synaptic signaling, which has been commonly described in immature neurons (Cherubini et al., 1991). This was directly shown for Cajal-Retzius cells in the neonatal neocortex by field stimulation of layer II/III, which produced gabazine-sensitive action potentials (recorded with non-invasive techniques: Cosgrove and Maccaferri, 2012). In the hippocampus, the role of synaptic GABAergic input was studied by Quattrocolo and Maccaferri (2013). Unexpectedly, both GABAA receptor–dependent excitation and inhibition were observed (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2013). This result was possibly explained by the existence of Cajal-Retzius cells in functionally different (resting vs. spontaneously-firing) states. Resting cells would generate suprathreshold GABAA receptor-mediated depolarizing postsynaptic potentials, whereas spontaneously active cells would be driven into a refractory state due to voltage-dependent sodium channels inactivation (Kolbaev et al., 2011b). Both outcomes are consistent with the reported persistent lack of expression of the KCC2 transporter in hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells (Pozas et al., 2008), which would maintain depolarizing GABAergic signaling and prevent a developmentally-driven excitatory/inhibitory switch (Rivera et al., 1999). Therefore, it is difficult to predict a simple and unique effect of GABAergic synaptic input on Cajal-Retzius cells in vivo, as it may be dependent on their level of activity. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that GABAergic excitation observed in reduced preparations in vitro may not translate into similar excitation in vivo (Kirmse et al., 2015; Valeeva et al., 2016, but see also commentaries by Ben-Ari, 2015, and Zilberter, 2015).

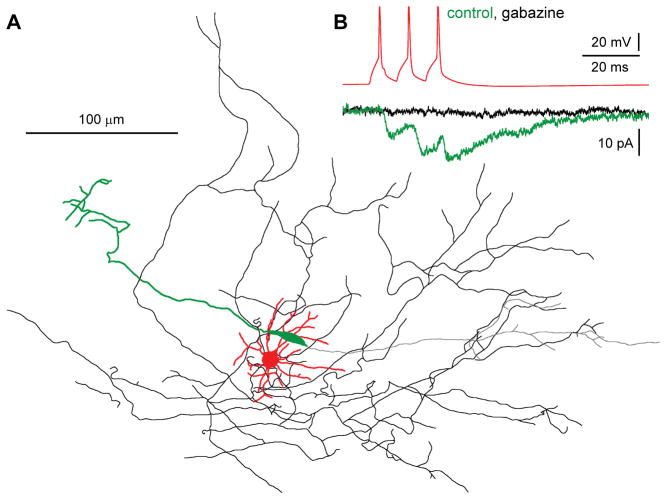

Figure 4.

Neurogliaform cells are a presynaptic source of GABAergic input to Cajal-Retzius cells. (A) Anatomical reconstruction of a synaptically connected presynaptic neurogliaform interneuron (dendrites, red and axon, black) and a Cajal-Retzius cell (dendrites, green and axon, gray). (B) Unitary postsynaptic current originated by a neurogliaform cell. Action potentials in the interneuron (top trace, red) generate a response in the postsynaptic Cajal-Retzius cell (bottom, green), which is completely abolished by the GABAA receptor antagonist gabazine (bottom, black). Both (A) and (B) Modifed with permission from Quattrocolo and Maccaferri (2013), under CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

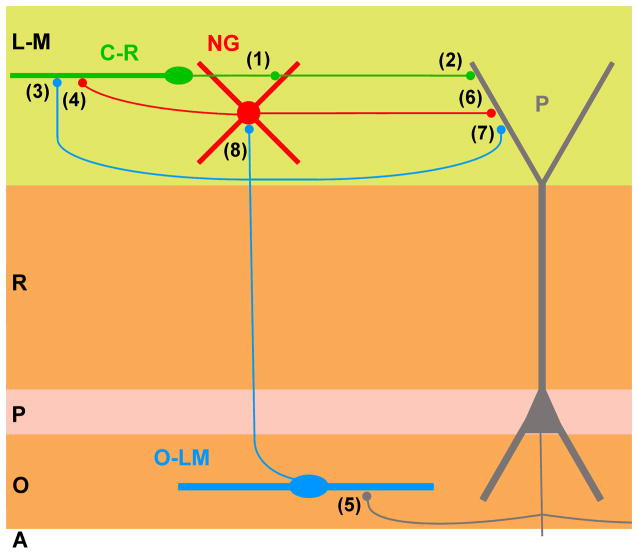

Figure 5.

Cartoon summarizing the connectivity of the Cajal-Retzius/GABAergic interneuron microcircuit of the CA1 hippocampus. Cajal-Retzius cell (green, C-R), neurogliaform cell (NG, red), O-LM interneuron (O-LM, blue), and pyramidal cell (gray, P). Notice the excitatory output synapse of Cajal-Retzius cells onto GABAergic interneurons and pyramidal cells (1 and 2, Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014, Anstötz et al., 2016), and the GABAergic input onto Cajal-Retzius cells from O-LM interneurons and neurogliaform cells (3 and 4: Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2013). Additional synapses between pyramidal cells and O-LM interneurons (5: Ali and Thomson, 1998), between neurogliaform and O-LM cells onto pyramidal cells (6: see Price et al., 2005, 7: Maccaferri et al., 2000) and between O-LM cells and neurogliaform interneurons (8: Elfant et al., 2008) are indicated. L-M, Stratum lacunosum-moleculare; R, stratum radiatum; P, stratum pyramidale; O, stratum oriens; A, alveus. Modifed with permission from Quattrocolo and Maccaferri (2014) under CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

5. Hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cell/GABAergic interneuron microcircuits

Although there is direct structural and functional evidence for monosynaptic connections between hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells and GABAergic interneurons (Marchionni et al., 2010; Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014; Anstötz et al., 2016), it remains more difficult to ascertain the connectivity of Cajal-Retzius cells with other excitatory neurons. Here we will examine this point in some detail and then we will propose our view on the network effect(s) of Cajal-Retzius cells in the hippocampal circuit. First, and rather surprisingly, Cajal-Retzius cells do not appear to be significantly synaptically connected to each other. In fact, while their optogenetic stimulation evokes excitatory postsynaptic currents both in GABAergic interneurons of the molecular layers and pyramidal cells with a latency of several milliseconds, under the same experimental conditions no significant synaptic-like events can be detected on Cajal-Retzius cells themselves (only light-evoked photocurrent, see: Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014). However, as these experiments were performed in voltage-clamp at hyperpolarized command potentials, they would have allowed only the observation of AMPA-type postsynaptic glutamate receptor-mediated events. Therefore, the possibility of reciprocal connectivity mediated exclusively by NMDA-type receptors cannot be excluded and still needs to be verified. This point is especially important as pure NMDA receptor-mediated events have been observed in the neocortex following extracellular stimulation of unidentified afferents (Radnikow et al., 2002).

Optogenetic stimulation of Cajal-Retzius cells can reliably generate events mediated by AMPA- and NMDA-type postsynaptic glutamate receptors on target interneurons (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014). In contrast, under the same experimental conditions, the probability of observing responses in pyramidal cells is much smaller (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014). While this could reflect a true connectivity bias favoring GABAergic interneurons, it needs to be considered that the distance between the synaptic connection in the distal apical dendrites of the pyramidal cell and the somatic recording electrode may generate false negative results. Another possibility that has been suggested is that while functional connections to GABAergic interneurons reflect classical synaptic communication, postsynaptic responses on pyramidal cells may be mediated by volume transmission (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014). Thus, although Cajal-Retzius cell firing activates glutamate receptors on pyramidal cells, the detailed mechanism(s) involved are not completely clear. Lastly, very little information is available regarding the potential connectivity between Cajal-Retzius and dentate gyrus granule cells, which remains virtually unexplored.

Despite the uncertainties mentioned above, the overall hypothesis that Cajal-Retzius cells may have a targeting bias for GABAergic interneurons has received some experimental support. First, the ultrastructural examination of synaptic terminals originated by Cajal-Retzius cell have revealed that connections are preferentially established on dendritic shafts vs. spines (Marchionni et al., 2010; Anstötz et al., 2016). Second, as mentioned above, it is much easier to observe functional responses to optogenetic stimulation in GABAergic interneurons than in pyramidal cells (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014). Third, intense optogenetic stimulation of Cajal-Retzius cells generates high-jitter, multiphasic GABAA receptor-mediated polysynaptic responses on pyramidal cells (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014).

Thus, Cajal-Retzius cells appear to be part of an unusual circuit that can be activated by a chain of excitatory synapses both in feedforward and feedback manner. In the first case, glutamatergic input to neurogliaform cells from the entorhinal cortex (Price et al., 2005) would excite disynaptically Cajal-Retzius cells. As neurogliaform cells have the potential to activate Cajal-Retzius cells (Quattrocolo and Macaferri., 2013) and, at the same time, Cajal-Retzius cells can reciprocally activate neurogliaform cells (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014; Anstötz et al., 2016), then we propose that under conditions of strong functional input from the entorhinal cortex, this loop may increase the overall duration of synaptic signaling, and possibly affect the excitability of the distal dendrites of pyramidal cells. In the second case, firing of pyramidal cells would activate O-LM cells (Ali and Thomson, 1998), which would reach Cajal-Retzius cells with their projections to stratum-lacunosum-moleculare (Maccaferri et al., 2010). A summary cartoon of these microcircuits is shown in Figure 5.

6. Functional role of Cajal-Retzius cell/GABAergic microcircuits in vivo

Although Cajal-Retzius cells have been the subject of many studies as an early source of the glycoprotein reelin (Ogawa et al., 1995; Del Río et al., 1997), which is critical for the correct development of neocortical and hippocampal architecture (Frotscher, 1998), much less is known regarding the role played by their fast synaptic signaling in the hippocampus in vivo. The layer specificity of their local axonal targeting and their long-range projections (Ceranik et al., 1999, Anstötz et al., 2016) suggests their potential involvement in the regulation of information processing between the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex, which is important for spatial representation (Moser et al., 2017). However, a direct approach with selective lesions/stimulation/inactivation of Cajal-Retzius cells is still missing.

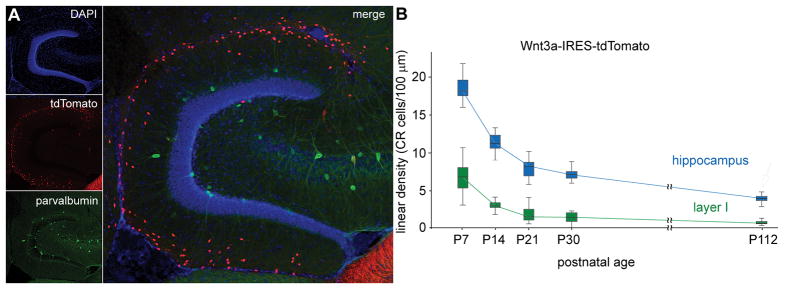

Other studies have shown that environmental enrichment, in addition to enhancing postnatal neurogenesis, promotes the postnatal survival of Cajal-Retzius cells (Anstötz et al., 2018). Thus, this correlative finding, taken together with the anatomical location of Cajal-Retzius cells close to the hippocampal neurogenic niche, has suggested the hypothesis that they may be involved in the regulation of the neurogenic process (Anstötz et al., 2018). In fact, it is interesting to note that, although these neurons decline in numbers with age, they still remain at higher densities in the hippocampus compared to the adjacent cortical areas, which are incapable of hosting postnatal neurogenesis (Figure 6). From a microcircuit point of view, this would fit very well with studies indicating that newborn granule cells are primarily innervated by neurogliaform interneurons (Markwardt et al., 2011), which are a GABAergic target of Cajal-Retzius cells (Quattrocolo and Maccaferri, 2014; Anstötz et al., 2018). Therefore, an interesting hypothesis that will need to be experimentally validated is that increased functional effects of Cajal-Retzius cells on neurogliaform cells may be required to drive enhanced GABAergic release, which is critical for the synaptic integration of newly generated neurons (Ge et al., 2006).

Figure 6.

Persistence of Cajal-Retzius cells in the hippocampus of mature animals. (A) Left panel, identification of Cajal-Retzius cells by tdTomato fluorescence in the Wnt3a-IRES-tdTomato reporter mouse. Left column: images of the hippocampal molecular layers with nuclear counterstain (DAPI, top inset), presence of tdTomato (tdTomato, middle inset), and, for comparison, parvalbumin immunoreactivity (parvalbumin, bottom inset), which reveals GABAergic interneurons. Right inset: all channels superimposed. Notice the large numerical difference between tdTomato-labeled Cajal-Retzius cells and parvalbumin-expressing interneurons. P36 mouse. Modified with permission from Anstötz et al., (2018), © Oxford University Press. (B) A direct comparison of the developmental time course of the density of tdTomato-labeled Cajal-Retzius cells in the molecular layers of the hippocampus (hippocampus) vs. layer I of the adjacent cortical areas (layer I). Notice that although densities do decrease in both regions, the values observed in the hippocampus of mature animals are comparable to what estimated in the cortex at much earlier developmental stages. Modifed with permission from Anstötz et al., (2018), © Oxford University Press.

Lastly, data from human pathology have suggested that Cajal-Retzius cell-driven microcircuits may be involved in the development of epilepsy. The postmortem examination of hippocampal tissue from patients suffering from temporal lobe epilepsy with Ammon’s horn sclerosis reported an abnormally large number of hippocampal CRs, which was further increased in subjects who had experienced complex febrile seizures at young ages (Blümcke et al., 1996; 1999). Although purely correlational, these findings suggest the possibility of a maldevelopmental disorder where CRs may be involved in some forms of temperature-initiated epileptogenesis (Blümcke et al., 2002), but no clear causal mechanisms linking temperatures in the febrile seizure range to CR activity were either described or proposed. Intriguingly, the expression of the temperature-sensitive channel TRPV1 in Cajal-Retzius cells has been suggested both by two reporter mice lines (Cavanaugh et al., 2011) and, more recently, by direct physiological techniques (Anstötz et al. in press). It would be interesting to measure the effect of temperature-driven activation of TRPV1 in Cajal-Retzius cells for the overall network excitability, but further studies are needed.

7. Conclusions

Despite the wealth of excellent review articles focused on reelin-related roles played by Cajal-Retzius cells, we hope that our brief and partial summary of their relationships with GABAergic interneurons in the developing hippocampus will convince electrophysiologists to keep these microcircuits into account when testing novel hypotheses and/or proposing new models of hippocampal function or dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Marco Martina for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke (Grant NS064135 to G.M.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achilles K, Okabe A, Ikeda M, Shimizu-Okabe C, Yamada J, Fukuda A, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W. Kinetic properties of Cl uptake mediated by Na+-dependent K+-2Cl cotransport in immature rat neocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8616–8627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5041-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali AB, Thomson AM. Facilitating pyramid to horizontal oriens-alveus interneurone inputs: dual intracellular recordings in slices of rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1998;507:185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.185bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Almeida LE, Randall WR, Albuquerque EX. Nicotine at concentrations found in cigarette smokers activates and desensitizes nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in CA1 interneurons of rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2726–2739. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 and alpha4beta2 subtypes differentially control GABAergic input to CA1 neurons in rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:3043–3055. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.6.3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson W, Galván E, Mauna J, Thiels E, Barrionuevo G. Properties and functional implications of I h in hippocampal area CA3 interneurons. Pflügers Arch. 2011;462:895–912. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstötz M, Cosgrove KE, Hack I, Mugnaini E, Maccaferri G, Lübke JH. Morphology, input-output relations and synaptic connectivity of Cajal-Retzius cells in layer 1 of the developing neocortex of CXCR4-EGFP mice. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219:2119–2139. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0627-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstötz M, Huang H, Marchionni I, Haumann I, Maccaferri G, Lübke JH. Developmental Profile, Morphology, and Synaptic Connectivity of Cajal-Retzius Cells in the Postnatal Mouse Hippocampus. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:855–872. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstötz M, Lee SK, Neblett TI, Rune GM, Maccaferri G. Experience-Dependent Regulation of Cajal-Retzius Cell Networks in the Developing and Adult Mouse Hippocampus. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:672–687. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstötz M, Lee SK, Maccaferri G. Expression of TRPV1 channels by Cajal-Retzius cells and layer-specific modulation of synaptic transmission by capsaicin in the mouse hippocampus. J Physiol. 2018 doi: 10.1113/JP275685. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnth-Jensen N, Jabaudon D, Scanziani M. Cooperation between independent hippocampal synapses is controlled by glutamate uptake. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:325–331. doi: 10.1038/nn825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli GA, Brown KM, Calixto E, Card JP, Galván EJ, Perez-Rosello T, Barrionuevo G. Quantitative morphometry of electrophysiologically identified CA3b interneurons reveals robust local geometry and distinct cell classes. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:677–695. doi: 10.1002/cne.22082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzori M. Pyramidal cells and stratum lacunosum-moleculare interneurons in the CA1 hippocampal region share a GABAergic spontaneous input. Hippocampus. 1996;6:72–78. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:1<72::AID-HIPO12>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraban SC, Bellingham MC, Berger AJ, Schwartzkroin PA. Osmolarity modulates K+ channel function on rat hippocampal interneurons but not CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 1997;498:679–689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KA, Shim H, Chen CK, McQuiston AR. Nicotinic excitatory postsynaptic potentials in hippocampal CA1 interneurons are predominantly mediated by nicotinic receptors that contain α4 and β2 subunits. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:1379–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Woodin MA, Sernagor E, Cancedda L, Vinay L, Rivera C, Legendre P, Luhmann HJ, Bordey A, Wenner P, Fukuda A, van den Pol AN, Gaiarsa JL, Cherubini E. Refuting the challenges of the developmental shift of polarity of GABA actions: GABA more exciting than ever! Front. Cell Neurosci. 2012;6:35. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2012.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y. Commentary: GABA depolarizes immature neurons and inhibits network activity in the neonatal neocortex in vivo. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:478. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielle F, Griveau A, Narboux-Nême N, Vigneau S, Sigrist M, Arber S, Wassef M, Pierani A. Multiple origins of Cajal-Retzius cells at the borders of the developing pallium. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1002–1012. doi: 10.1038/nn1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blümcke I, Beck H, Nitsch R, Eickhoff C, Scheffler B, Celio MR, Schramm J, Elger CE, Wolf HK, Wiestler OD. Preservation of calretinin-immunoreactive neurons in the hippocampus of epilepsy patients with Ammon’s horn sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:329–341. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199603000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blümcke I, Beck H, Suter B, Hoffmann D, Födisch HJ, Wolf HK, Schramm J, Elger CE, Wiestler OD. An increase of hippocampal calretinin-immunoreactive neurons correlates with early febrile seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Acta Neuropathol. 1999;97:31–39. doi: 10.1007/s004010050952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blümcke I, Thom M, Wiestler OD. Ammon’s horn sclerosis: a maldevelopmental disorder associated with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:199–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booker SA, Song J, Vida I. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from morphologically-and neurochemically-identified hippocampal interneurons. J Vis Exp. 2014;91:e51706. doi: 10.3791/51706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell V, Marín O. Meninges control tangential migration of hem-derived Cajal-Retzius cells via CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1284–1293. doi: 10.1038/nn1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregestovski P, Bernard C. Excitatory GABA: How a Correct Observation May Turn Out to be an Experimental Artifact. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:65. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceranik K, Bender R, Geiger JR, Monyer H, Jonas P, Frotscher M, Lübke J. A novel type of GABAergic interneuron connecting the input and the output regions of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5380–5394. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05380.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceranik K, Deng J, Heimrich B, Lübke J, Zhao S, Förster E, Frotscher M. Hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells project to the entorhinal cortex: retrograde tracing and intracellular labelling studies. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4278–4290. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceranik K, Zhao S, Frotscher M. Development of the entorhino-hippocampal projection: guidance by Cajal-Retzius cell axons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;911:43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CH, Yeh HH. Enhanced GABA(A) receptor-mediated activity following activation of NMDA receptors in Cajal-Retzius cells in the developing mouse neocortex. J Physiol. 2003;550:103–111. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CA, Lacaille JC. Intrinsic theta-frequency membrane potential oscillations in hippocampal CA1 interneurons of stratum lacunosum-moleculare. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1296–1307. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini E, Gaiarsa JL, Ben-Ari Y. GABA: an excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh DJ, Chesler AT, Jackson AC, Sigal YM, Yamanaka H, Grant R, O’Donnell D, Nicoll RA, Shah NM, Julius D, Basbaum AI. Trpv1 reporter mice reveal highly restricted brain distribution and functional expression in arteriolar smooth muscle cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5067–5077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6451-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury TG, Jimenez JC, Bomar JM, Cruz-Martin A, Cantle JP, Portera-Cailliau C. Fate of cajal-retzius neurons in the postnatal mouse neocortex. Front Neuroanat. 2010;4:10. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.010.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove KE, Maccaferri G. mGlu1α-dependent recruitment of excitatory GABAergic input to neocortical Cajal-Retzius cells. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:486–493. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Río JA, Martínez A, Fonseca M, Auladell C, Soriano E. Glutamate-like immunoreactivity and fate of Cajal-Retzius cells in the murine cortex as identified with calretinin antibody. Cereb Cortex. 1995;5:13–21. doi: 10.1093/cercor/5.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Río JA, Heimrich B, Supèr H, Borrell V, Frotscher M, Soriano E. Differential survival of Cajal-Retzius cells in organotypic cultures of hippocampus and neocortex. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6896–6907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06896.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Río JA, Heimrich B, Borrell V, Förster E, Drakew A, Alcántara S, Nakajima K, Miyata T, Ogawa M, Mikoshiba K, Derer P, Frotscher M, Soriano E. A role for Cajal-Retzius cells and reelin in the development of hippocampal connections. Nature. 1997;385:70–74. doi: 10.1038/385070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derer P, Derer M. Cajal–Retzius cell ontogenesis and death in mouse brain visualized with horseradish peroxidase and electron microscopy. Neuroscience. 1990;36:839–856. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorzhak A, Myakhar O, Unichenko P, Kirmse K, Kirischuk S. Estimation of ambient GABA levels in layer I of the mouse neonatal cortex in brain slices. J Physiol. 2010;588:2351–2360. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Konnerth A. Patch-clamping cells in sliced tissue preparations. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:208–222. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07015-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfant D, Pál BZ, Emptage N, Capogna M. Specific inhibitory synapses shift the balance from feedforward to feedback inhibition of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:104–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.06001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Buzsáki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frotscher M. Cajal-Retzius cells, Reelin, and the formation of layers. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;5:570–575. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba P, Klausberger T, Karayannis T, Suen WY, Huck J, Tomioka R, Rockland K, Capogna M, Studer M, Morales M, Somogyi P. Expression of COUP-TFII nuclear receptor in restricted GABAergic neuronal populations in the adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1595–1609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4199-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Moreno F, López-Mascaraque L, De Carlos JA. Origins and migratory routes of murine Cajal-Retzius cells. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:419–432. doi: 10.1002/cne.21128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Goh EL, Sailor KA, Kitabatake Y, Ming GL, Song H. GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature. 2006;439:589–593. doi: 10.1038/nature04404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger JR, Bischofberger J, Vida I, Fröbe U, Pfitzinger S, Weber HJ, Haverkampf K, Jonas P. Patch-clamp recording in brain slices with improved slicer technology. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil V, Nocentini S, Del Río JA. Historical first descriptions of Cajal-Retzius cells: from pioneer studies to current knowledge. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:32. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Sanz C, Franco SJ, Martinez-Garay I, Espinosa A, Harkins-Perry S, Müller U. Cajal-Retzius cells instruct neuronal migration by coincidence signaling between secreted and contact-dependent guidance cues. Neuron. 2013;79:461–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Zheng C, Doughty ML, Losos K, Didkovsky N, Schambra UB, Nowak NJ, Joyner A, Leblanc G, Hatten ME, Heintz N. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griveau A, Borello U, Causeret F, Tissir F, Boggetto N, Karaz S, Pierani A. A novel role for Dbx1-derived Cajal-Retzius cells in early regionalization of the cerebral cortical neuroepithelium. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Liu B, Wu X, Yan Y, Zhang Y, Wei Y, Pleasure SJ, Zhao C. Inducible genetic lineage tracing of cortical hem derived Cajal-Retzius cells reveals novel properties. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulledge AT, Stuart GJ. Excitatory actions of GABA in the cortex. Neuron. 2003;37:299–309. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hestrin S, Armstrong WE. Morphology and physiology of cortical neurons in layer I. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5290–5300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05290.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Neogi T, Englund C, Daza RA, Fink A. Cajal-Retzius cells in the mouse: transcription factors, neurotransmitters, and birthdays suggest a pallial origin. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1994;141:39–53. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T, Lee C, Tai M, Lien C. Differential Recruitment of Dentate Gyrus Interneuron Types by Commissural Versus Perforant Pathways. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:2715–2727. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoto K, Karasawa N, Isomura G, Nagatsu I. Cajal-Retzius neurons identified by GABA immunohistochemistry in layer I of the rat cerebral cortex. Neurosci Res. 1994;20:101–105. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(94)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ina A, Sugiyama M, Konno J, Yoshida S, Ohmomo H, Nogami H, Shutoh F, Hisano S. Cajal-Retzius cells and subplate neurons differentially express vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 during development of mouse cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:615–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isa T, Itazawa S, Iino M, Tsuzuki K, Ozawa S. Distribution of neurones expressing inwardly rectifying and Ca(2+)-permeable AMPA receptors in rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol. 1996;491:719–733. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karayannis T, Elfant D, Huerta-Ocampo I, Teki S, Scott RS, Rusakov DA, Jones MV, Capogna M. Slow GABA transient and receptor desensitization shape synaptic responses evoked by hippocampal neurogliaform cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9898–9909. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5883-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilb W, Luhmann H. Characterization of a hyperpolarization-activated inward current in Cajal-Retzius cells in rat neonatal neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1681–1691. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilb W, Luhmann HJ. Spontaneous GABAergic postsynaptic currents in Cajal-Retzius cells in neonatal rat cerebral cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1387–1390. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirischuk S, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W. Cajal-Retzius cells: update on structural and functional properties of these mystic neurons that bridged the 20th century. Neuroscience. 2014;275:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmse K, Grantyn R, Kirischuk S. Developmental downregulation of low-voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in Cajal-Retzius cells of the mouse visual cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:3269–3276. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmse K, Kirischuk S. Ambient GABA constrains the strength of GABAergic synapses at Cajal-Retzius cells in the developing visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4216–4227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0589-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmse K, Dvorzhak A, Henneberger C, Grantyn R, Kirischuk S. Cajal Retzius cells in the mouse neocortex receive two types of pre- and postsynaptically distinct GABAergic inputs. J Physiol. 2007;585:881–895. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmse K, Dvorzhak A, Grantyn R, Kirischuk S. Developmental downregulation of excitatory GABAergic transmission in neocortical layer I via presynaptic adenosine A(1) receptors. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:424–432. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmse K, Kummer M, Kovalchuk Y, Witte OW, Garaschuk O, Holthoff K. GABA depolarizes immature neurons and inhibits network activity in the neonatal neocortex in vivo. Nat Commun. 2015;16(6):7750. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbaev SN, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W. Activity-dependent scaling of GABAergic excitation by dynamic Cl− changes in Cajal-Retzius cells. Pflugers Arch. 2011a;461:557–565. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0935-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbaev SN, Achilles K, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W. Effect of depolarizing GABA(A)-mediated membrane responses on excitability of Cajal-Retzius cells in the immature rat neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 2011b;106:2034–2044. doi: 10.1152/jn.00699.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krook-Magnuson E, Luu L, Lee SH, Varga C, Soltesz I. Ivy and neurogliaform interneurons are a major target of μ-opioid receptor modulation. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14861–14870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2269-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledonne F, Orduz D, Mercier J, Vigier L, Grove EA, Tissir F, Angulo MC, Pierani A, Coppola E. Targeted Inactivation of Bax Reveals a Subtype-Specific Mechanism of Cajal-Retzius Neuron Death in the Postnatal Cerebral Cortex. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3133–3141. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi A, Yoshida M, Grove EA. The derivatives of the Wnt3a lineage in the central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2007;504:550–569. doi: 10.1002/cne.21461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SM, Zecevic N, Yeh HH. Distinct NMDA and AMPA receptor-mediated responses in mouse and human Cajal-Retzius cells. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2642–2646. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann HJ, Reiprich RA, Hanganu I, Kilb W. Cellular physiology of the neonatal rat cerebral cortex: intrinsic membrane properties, sodium and calcium currents. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:574–584. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001115)62:4<574::AID-JNR12>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Roberts JD, Szucs P, Cottingham CA, Somogyi P. Cell surface domain specific postsynaptic currents evoked by identified GABAergic neurones in rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol. 2000;524:91–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-3-00091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchionni I, Takács VT, Nunzi MG, Mugnaini E, Miller RJ, Maccaferri G. Distinctive properties of CXC chemokine receptor 4-expressing Cajal-Retzius cells versus GABAergic interneurons of the postnatal hippocampus. J Physiol. 2010;588:2859–2878. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.190868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Padilla M. Three-dimensional structural organization of layer I of the human cerebral cortex: a Golgi study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;299:89–105. doi: 10.1002/cne.902990107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwardt S, Dieni C, Wadiche J, Overstreet-Wadiche L. Ivy/neurogliaform interneurons coordinate activity in the neurogenic niche. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:407–409. doi: 10.1038/nn.2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DL, Rimvall K. Regulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid synthesis in the brain. J Neurochem. 1993;60:395–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cerdeño V, Noctor SC. Cajal, Retzius, and Cajal-Retzius cells. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:48. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Galán JR, López-Bendito G, Luján R, Shigemoto R, Fairén A, Valdeolmillos M. Cajal-Retzius cells in early postnatal mouse cortex selectively express functional metabotropic glutamate receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1147–1154. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuiston AR, Madison DV. Muscarinic receptor activity has multiple effects on the resting membrane potentials of CA1 hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5693–5702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Goffinet AM, Fairén A. What is a Cajal-Retzius cell? A reassessment of a classical cell type based on recent observations in the developing neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:765–775. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.8.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Perez-Garcia CG, Abraham H, Caput D. Expression of p73 and Reelin in the developing human cortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4973–4986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-04973.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mienville JM. Persistent depolarizing action of GABA in rat Cajal-Retzius cells. J Physiol. 1998;512:809–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.809bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mienville JM. Cajal-Retzius cell physiology: just in time to bridge the 20th century. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:776–782. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.8.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles R, Traub RD. Neuronal Networks of the Hippocampus. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Morin F, Beaulieu C, Lacaille JC. Membrane properties and synaptic currents evoked in CA1 interneuron subtypes in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1–16. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin F, Beaulieu C, Lacaille JC. Cell-specific alterations in synaptic properties of hippocampal CA1 interneurons after kainate treatment. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2836–2847. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser EI, Moser MB, McNaughton BL. Spatial representation in the hippocampal formation: a history. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1448–1464. doi: 10.1038/nn.4653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer JR, Jr, Brown TH. Methods for whole-cell recording from visually preselected neurons of perirhinal cortex in brain slices from young and aging rats. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;86:35–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myakhar O, Unichenko P, Kirischuk S. GABAergic projections from the subplate to Cajal-Retzius cells in the neocortex. Neuroreport. 2011;22:525–529. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834888a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naqui SZ, Harris BS, Thomaidou D, Parnavelas JG. The noradrenergic system influences the fate of Cajal-Retzius cells in the developing cerebral cortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;113:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, Yagyu K, Seike M, Ikenaka K, Yamamoto H, Mikoshiba K. The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:899–912. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnavelas JG, Edmunds SM. Further evidence that Retzius–Cajal cells transform to nonpyramidal neurons in the developing rat visual cortex. J Neurocytol. 1983;12:863–871. doi: 10.1007/BF01258156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A, Crow M, Raudales R, He M, Gillis J, Huang ZJ. Transcriptional Architecture of Synaptic Communication Delineates GABAergic Neuron Identity. Cell. 2017;171:522–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Chittajallu R, Craig MT, Tricoire L, Wester JC, McBain CJ. Hippocampal GABAergic Inhibitory Interneurons. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:1619–1747. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesold C, Impagnatiello F, Pisu MG, Uzunov DP, Costa E, Guidotti A, Caruncho HJ. Reelin is preferentially expressed in neurons synthesizing gamma-aminobutyric acid in cortex and hippocampus of adult rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3221–3226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Cauli B, Kovacs ER, Kulik A, Lambolez B, Shigemoto R, Capogna M. Neurogliaform Neurons Form a Novel Inhibitory Network in the Hippocampal CA1 Area. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6775–6786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1135-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Scott R, Rusakov DA, Capogna M. GABA(B) receptor modulation of feedforward inhibition through hippocampal neurogliaform cells. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6974–6982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4673-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozas E, Paco S, Soriano E, Aguado F. Cajal-Retzius cells fail to trigger the developmental expression of the Cl− extruding co-transporter KCC2. Brain Res. 2008;1239:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocolo G, Maccaferri G. Novel GABAergic circuits mediating excitation/inhibition of Cajal-Retzius cells in the developing hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5486–5498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5680-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrocolo G, Maccaferri G. Optogenetic activation of cajal-retzius cells reveals their glutamatergic output and a novel feedforward circuit in the developing mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2014;34:13018–13032. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1407-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radnikow G, Feldmeyer D, Lübke J. Axonal projection, input and output synapses, and synaptic physiology of Cajal-Retzius cells in the developing rat neocortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6908–6919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06908.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, Pirvola U, Saarma M, Kaila K. The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397:251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Reig N, Andrés B, Huilgol D, Grove EA, Tissir F, Tole S, Theil T, Herrera E, Fairén A. Lateral Thalamic Eminence: A Novel Origin for mGluR1/Lot Cells. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27:2841–2856. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L. Role of Cajal–Retzius and subplate neurons in cerebral cortical development. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2002;9:302–308. doi: 10.1053/spen.2002.32506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sava BA, Dávid CS, Teissier A, Pierani A, Staiger JF, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W. Electrophysiological and morphological properties of Cajal-Retzius cells with different ontogenetic origins. Neuroscience. 2010;167:724–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soda T, Nakashima R, Watanabe D, Nakajima K, Pastan I, Nakanishi S. Segregation and coactivation of developing neocortical layer 1 neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6272–6279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06272.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano E, Del Río JA. The cells of cajal-retzius: still a mystery one century after. Neuron. 2005;46:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N, McBain C. Structural and Functional Properties of Hippocampal Neurons. In: Andersen P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O’Keefe J, editors. The Hippocampus Book. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. pp. 133–201. [Google Scholar]

- Stumm RK, Rummel J, Junker V, Culmsee C, Pfeiffer M, Krieglstein J, Höllt V, Schulz S. A dual role for the SDF-1/CXCR4 chemokine receptor system in adult brain: isoform-selective regulation of SDF-1 expression modulates CXCR4-dependent neuronal plasticity and cerebral leukocyte recruitment after focal ischemia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5865–5878. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05865.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supèr H, Martínez A, Del Río JA, Soriano E. Involvement of distinct pioneer neurons in the formation of layer-specific connections in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4616–4626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04616.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadics J, Tamás G, Soltesz I. Different transmitter transients underlie presynaptic cell type specificity of GABAA,slow and GABAA,fast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14831–14836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707204104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiguchi-Hayashi K, Sekiguchi M, Ashigaki S, Takamatsu M, Hasegawa H, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Nakanishi S, Tanabe Y. Generation of reelin-positive marginal zone cells from the caudomedial wall of telencephalic vesicles. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2286–2295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4671-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissir F, Ravni A, Achouri Y, Riethmacher D, Meyer G, Goffinet AM. DeltaNp73 regulates neuronal survival in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16871–16876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903191106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar-Cerviño V, Molano-Mazón M, Catchpole T, Valdeolmillos M, Henkemeyer M, Martínez LM, Borrell V, Marín O. Contact repulsion controls the dispersion and final distribution of Cajal-Retzius cells. Neuron. 2013;77:457–471. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeeva G, Tressard T, Mukhtarov M, Baude A, Khazipov R. An Optogenetic Approach for Investigation of Excitatory and Inhibitory Network GABA Actions in Mice Expressing Channelrhodopsin-2 in GABAergic Neurons. J Neurosci. 2016;36:5961–5973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3482-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Haebler D, Stabel J, Draguhn A, Heinemann U. Properties of horizontal cells transiently appearing in the rat dentate gyrus during ontogenesis. Exp Brain Res. 1993;94:33–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00230468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyskiel DR, Andrade R. Serotonin excites hippocampal CA1 GABAergic interneurons at the stratum radiatum-stratum lacunosum moleculare border. Hippocampus. 2016;26:1107–1114. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Assimacopoulos S, Jones KR, Grove EA. Massive loss of Cajal-Retzius cells does not disrupt neocortical layer order. Development. 2006;133:537–545. doi: 10.1242/dev.02209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Fan W, Wu P, Deng J, Liu J, Niu Y, Li M, Deng J. Characterization of hippocampal Cajal-Retzius cells during development in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (Tg2576) Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:394–401. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.128243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Swietek B, Proddutur A, Santhakumar V. Dentate total molecular layer interneurons mediate cannabinoid-sensitive inhibition. Hippocampus. 2015;25:884–889. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Hablitz JJ. Postnatal development of membrane properties of layer I neurons in rat neocortex. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1131–1139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01131.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberter Y. Commentary: GABA Depolarizes Immature Neurons and Inhibits Network Activity in the Neonatal Neocortex In vivo. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:294. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsiros V, Maccaferri G. Electrical coupling between interneurons with different excitable properties in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare of the juvenile CA1 rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8686–8695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2810-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsiros V, Aradi I, Maccaferri G. Propagation of postsynaptic currents and potentials via gap junctions in GABAergic networks of the rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2007;578:527–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]