Abstract

Although it is well appreciated that practicing a motor task updates the associated internal model, it is still unknown how the cortical oscillations linked with the motor action change with practice. The present study investigates the short-term changes (e.g., fast motor learning) in the α- and β-event-related desynchronizations (ERD) associated with the production of a motor action. To this end, we used magnetoencephalography to identify changes in the α- and β-ERD in healthy adults after participants practiced a novel isometric ankle plantarflexion target-matching task. After practicing, the participants matched the targets faster and had improved accuracy, faster force production, and a reduced amount of variability in the force output when trying to match the target. Parallel with the behavioral results, the strength of the β-ERD across the motor-planning and execution stages was reduced after practice in the sensorimotor and occipital cortexes. No pre/postpractice changes were found in the α-ERD during motor planning or execution. Together, these outcomes suggest that fast motor learning is associated with a decrease in β-ERD power. The decreased strength likely reflects a more refined motor plan, a reduction in neural resources needed to perform the task, and/or an enhancement of the processes that are involved in the visuomotor transformations that occur before the onset of the motor action. These results may augment the development of neurologically based practice strategies and/or lead to new practice strategies that increase motor learning.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We aimed to determine the effects of practice on the movement-related cortical oscillatory activity. Following practice, we found that the performance of the ankle plantarflexion target-matching task improved and the power of the β-oscillations decreased in the sensorimotor and occipital cortexes. These novel findings capture the β-oscillatory activity changes in the sensorimotor and occipital cortexes that are coupled with behavioral changes to demonstrate the effects of motor learning.

Keywords: β-ERD, learning, lower extremity, magnetoencephalography, motor control

INTRODUCTION

It is well recognized that the brain maintains and updates a real-time internal representation of how the musculoskeletal system performs under various task constraints (Huang et al. 2011; Hwang and Shadmehr 2005; Kluzik et al. 2008; Milner and Franklin 2005; Smith and Shadmehr 2005; Thoroughman and Shadmehr 1999). This internal model is used to make feedforward predictions about the ideal muscle synergies that are necessary to accurately perform a motor task, but these models are rarely perfect and are generally adaptively updated as one becomes more proficient at a motor task (Shadmehr 2004; Wolpert 2007). Improving the internal model is thought to be based on sensory feedback and knowledge about the success of the final motor performance (Doyon and Benali 2005; Willingham 1998). This process occurs in three distinct stages as follows: 1) a fast motor-learning stage where there are rapid improvements in the task performance after a single practice session, 2) a slow motor-learning stage where there are incremental improvements across multiple practice sessions, and 3) an offline learning stage where the motor memories are consolidated and skill stabilization occurs (Dayan and Cohen 2011; Doyon and Benali 2005; Doyon and Ungerleider 2002; Fischer et al. 2005; Korman et al. 2003; Muellbacher et al. 2002; Robertson et al. 2004; Walker et al. 2002). Although it is accepted that the internal model is updated through these various processing stages, it is not well established how these changes are reflected in the cortical activity of the sensorimotor network.

A few functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) investigations have examined the changes that occur in the internal model of healthy adults after practicing a novel motor task (Arima et al. 2011; Floyer-Lea and Matthews 2005; Grafton et al. 2002; Honda et al. 1998; Sacco et al. 2006, 2009; Sakai et al. 1999; Shadmehr and Holcomb, 1997; Zhang et al. 2011). These studies have shown that the strength of activation in the primary motor area, supplementary motor area (SMA), prefrontal cortex, parietal cortex, and the cerebellum can change after practice. The short-term changes (e.g., fast motor learning) seen in these cortical areas appear to be associated with improved spatial processing, sensorimotor transformations, online error corrections, and improved resource allocation (Doyon and Ungerleider 2002; Hikosaka et al. 2002; Kelly and Garavan 2005; Petersen et al. 1998; Tamás Kincses et al. 2008). Although these studies have provided critical insight on the areas of the brain that are altered by practicing a motor task, the role that these areas play in the planning and execution of the motor action, and the associated neural dynamics, are not well identified.

Outcomes from electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and invasive electrocorticography experiments have shown that cortical oscillatory activity decreases in the β-frequency range (15–30 Hz) before the onset of movement and that this is sustained throughout the majority of the movement (Alegre et al. 2002; Cassim et al. 2000; Crone et al. 1998; Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015; Jurkiewicz et al. 2006; Kaiser et al. 2001; Kilner et al. 2004; Kurz et al. 2014b, 2015, 2017; Miller et al. 2010; Pfurtscheller and Berghold 1989; Pfurtscheller et al. 2003; Tzagarakis et al. 2010; Wilson et al. 2014, 2016, 2010; 2011). The decrease in the amount of power, commonly termed β-desynchronization, is thought to reflect task-related changes in the activity level of local populations of neurons. The consensus is that this β-event-related desynchronization (ERD) is related to the formulation of a motor plan because it begins well before the onset of movement and is influenced by the certainty of the movement pattern to be performed (Alegre et al. 2002; Grent-’t-Jong et al. 2014; Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson, 2015; Kaiser et al. 2001; Pollok et al. 2014; Tzagarakis et al. 2010, 2015). Typical β-ERD responses involve widespread bilateral activity across the sensorimotor cortical areas, with the strongest maxima contralateral to the effector producing the motor action and following the basic homuncular topology of the pre/postcentral gyri. Additional areas of concurrent β-ERD activity often include the premotor area, SMA, parietal cortexes, and midcingulate (Jurkiewicz et al. 2006; Kurz et al. 2016; Tzagarakis et al. 2010; 2015; Wilson et al. 2014). Despite the recognition that β-oscillations play a prominent role in the production of motor actions, we still have an incomplete understanding of how these oscillations are altered after practicing a motor action.

In summary, cortical β-oscillations are known to play a key role in motor planning and execution but whether these responses are modulated by practice and learning remains largely unknown. Moreover, it is unclear how these cortical oscillations may change across the respective stages of learning (e.g., fast learning, slow learning, and memory consolidation). The objective of the current investigation was to use high-density MEG to begin to address these knowledge gaps by quantifying how β-cortical oscillations during the motor-planning and execution stages are altered after a short-term practice session (e.g., fast motor-learning stage) involving an ankle plantarflexion motor task.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Nebraska Medical Center reviewed and approved the protocol for this investigation. Fifteen healthy right-hand-dominant adults [mean age = 23.3 ± 3.3 (SD) yr, 6 female] with no neurological or musculoskeletal impairments participated in this investigation. All of the participants provided written informed consent to participate in the investigation.

MEG data acquisition and experimental paradigm.

Neuromagnetic responses were sampled continuously at 1 kHz with an acquisition bandwidth of 0.1–330 Hz using an Elekta MEG system (Helsinki, Finland) with 306 magnetic sensors, including 204 planar gradiometers and 102 magnetometers. All recordings were conducted in a one-layer magnetically shielded room with active shielding engaged for advanced environmental noise compensation. During data acquisition, the participants were monitored via real-time audio-video feeds from inside the shielded room.

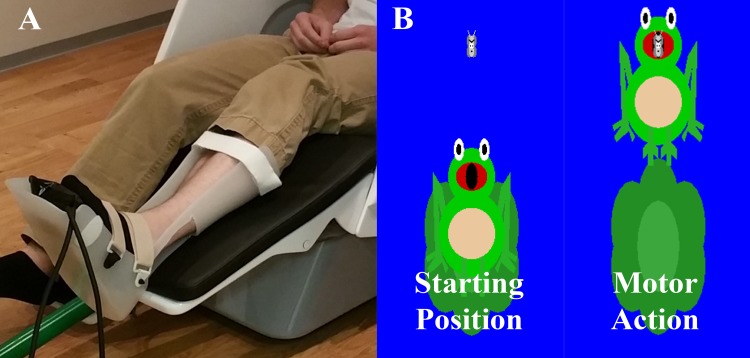

The participants were seated upright in a magnetically silent chair during the experiment. A custom-built magnetically silent force transducer was developed for this investigation to measure isometric ankle plantarflexion forces (Fig. 1A). This device consisted of a 20 × 10 cm airbladder that was inflated to 317 kPa and integrated within an ankle foot orthosis. Changes in the pressure of the airbag, because of participants’ generating an isometric ankle plantarflexion force, were quantified by an air pressure sensor (Phidgets, Calgary, Alberta, Canada) and were converted into units of force offline.

Fig. 1.

A: participant seated in the magnetoencephalography (MEG) chair with the custom pneumatic ankle force system on the left leg. The device consists of an airbag that is encased in a ridged ankle-foot orthotic. B: visual feedback displayed to the participant. Ankle plantarflexion forces generated by the participant animated the vertical position of a frog’s position on the screen. A successful trial occurred when the participant generated a plantarflexion force that positioned the frog’s mouth at the bug’s position and held it there for 300 ms.

The experimental paradigm involved the participant generating an isometric ankle plantarflexion force with the left leg that matched target forces that varied between 15 and 30% of the participant’s maximum isometric ankle plantarflexion force. The step size between the respective targets was one unit of force. The target force was visually displayed as a moth, and the force generated by the participant was shown as a frog that was animated vertically based on the isometric force generated (Fig. 1B). The participants were instructed to match the presented targets as fast and as accurately as possible. The distinct target forces were presented in a random order, and a successful match occurred when the bug that represented the target force was inside of the frog’s mouth for 0.3 s. The stimuli were shown on a back-projection screen that was ~1 meter in front of the participant and at eye level. Each trial was 10 s in length. The participants started each trial at rest while fixated at the center of the screen for 5 s. After this rest period, the target would appear, prompting the participant to try and produce the matching force value. The target was available to be matched for up to 5 s. Once the target was matched or 5 s elapsed, feedback was given to indicate the end of the trial, and the participant returned to rest and fixated on the center of the screen while waiting for the next target to appear. Participants performed three blocks of the ankle plantarflexion target-matching task, with each block containing 100 trials and ~3 min between each block. The first and third blocks were performed while recording MEG data, while the second block acted as an extended practice block, where the participant was provided additional information about the accuracy of their target-matching performance via an interactive biofeedback program. This program showed the participant the amount of error in their motor action by displaying the distance between the bug and the frog and provided auditory and visual rewards when the participant matched the target faster and had improved accuracy.

MEG coregistration.

Four coils were affixed to the head of the participant and were used for continuous head localization during the MEG experiment. Before the experiment, the location of these coils, three fiducial points, and the scalp surface were digitized to determine their three-dimensional position (Fastrak 3SF0002; Polhemus Navigator Sciences, Colchester, VT). Once the participant was positioned for the MEG recording, an electric current with a unique frequency label (e.g., 322 Hz) was fed to each of the four coils. This induced a measurable magnetic field and allowed for each coil to be localized in reference to the sensors throughout the recording session. Because the coil locations were also known in head coordinates, all MEG measurements could be transformed into a common coordinate system. With this coordinate system (including the scalp surface points), each participant’s MEG data were coregistered to a template structural MRI (MPRAGE) using three external landmarks (i.e., fiducials) and the digitized scalp surface points before source space analyses. The neuroanatomical MRI data were aligned parallel to the anterior and posterior commissures, and all data were transformed to standardized space using BESA MRI (version 2.0; BESA, Gräfelfing, Germany).

MEG preprocessing, time-frequency transformation, and statistics.

Using the MaxFilter software (Elekta), each MEG data set was individually corrected for head motion that may have occurred during task performance and subjected to noise reduction using the signal space separation method with a temporal extension (Taulu and Simola 2006). Artifact rejection was based on a fixed-threshold method supplemented with visual inspection. The continuous magnetic time series was divided into epochs of 10.0 s in duration (−5.0 to +5.0 s), with the onset of the isometric force defined as 0.0 s and the baseline defined as −2.0 to −1.4 s. Artifact-free epochs for each sensor were transformed into the time-frequency domain using complex demodulation (resolution: 2.0 Hz, 0.025 s) and averaged over the respective trials. These sensor-level data were normalized by dividing the power value of each time-frequency bin by the respective bin’s baseline power, which was calculated as the mean power during the baseline (−2.0 to −1.4 s). This time window was selected for the baseline based on our inspection of the sensor level absolute power data, which showed that this time window was quiet and temporally distant from the perimovement oscillatory activity. The specific time-frequency windows used for imaging were determined by statistical analysis of the sensor-level spectrograms across the entire array of gradiometers. Briefly, each data point in the spectrogram was initially evaluated using a mass univariate approach based on the general linear model. To reduce the risk of false-positive results while maintaining reasonable sensitivity, a two-stage procedure was followed to control for type 1 error. In the first stage, one-sample t-tests were conducted on each data point, and the output spectrogram of t-values was thresholded at P < 0.05 to define time-frequency bins containing potentially significant oscillatory deviations across all participants and conditions. In stage two, time-frequency bins that survived the threshold were clustered with temporally and/or spectrally neighboring bins that were also above the (P < 0.05) threshold, and a cluster value was derived by summing all of the t-values of all data points in the cluster. Nonparametric permutation testing was then used to derive a distribution of cluster-values, and the significance level of the observed clusters (from stage one) was tested directly using this distribution (Ernst 2004; Maris and Oostenveld 2007). For each comparison, at least 10,000 permutations were computed to build a distribution of cluster values.

MEG source imaging.

A minimum-variance vector beamforming algorithm was employed to calculate the source power across the entire brain volume (Gross et al. 2001). The single images were derived from the cross-spectral densities of all combinations of MEG sensors and the solution of the forward problem for each location on a grid specified by input voxel space. Following convention, the source power in these images was normalized per subject using a separately averaged prestimulus noise period of equal duration (−2.0 to −1.4 s) and bandwidth (α: 8–14 Hz, β; 24–32 Hz) to the target periods identified through statistical analyses (see above; Hillebrand and Barnes 2005; Hillebrand et al. 2005; Van Veen et al. 1997). Thus, the normalized power per voxel was computed over the entire brain volume per participant at 4.0 × 4.0 × 4.0 mm resolution. MEG preprocessing and imaging used the Brain Electrical Source Analysis (BESA) software (BESA version 6.0; Grafelfing, Germany).

Time series analysis was subsequently performed on the peak voxels extracted from the group-averaged beamformer images (see results). The virtual sensors were created by applying the sensor weighting matrix derived through the forward computation to the preprocessed signal vector, which resulted in a time series with the same temporal resolution as the original MEG recording (Cheyne et al. 2006; Heinrichs-Graham et al. 2016; Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2016). Once the virtual sensors were extracted, they were transformed into the time-frequency domain, and the two orientations for each peak voxel per individual were combined using a vector-summing algorithm. The power of these time courses, relative to baseline, was averaged across the window of interest for each individual to assess the temporal evolution of the key oscillatory responses. The postmovement β-responses were not examined because we had no hypotheses about these and because there were significant pre/postpractice differences in the time that the participants took to match the target, which would have confounded the analyses.

Motor behavioral data.

The output of the force transducer was simultaneously collected at 1 kHz along with the MEG data and was used to quantify the participant’s motor performance. The formulation of the motor plan was assumed to be represented by the participant’s reaction time, which was calculated based on the time from when the target was presented to when force production was initiated. The amount of error in the feedforward execution of the motor plan was behaviorally quantified based on the percent overshoot of the target. The time to match the target was used to quantify the online corrections that were made after the initial motor plan was executed. The online corrections were calculated based on the time difference between the reaction time and the time to reach the target. The coefficient of variation in the force produced while attempting to match the target was also used to evaluate the online corrections that the participants made while trying to match the target. A lower coefficient of variation signified fewer corrections in the force production when attempting to match the target.

Paired-sample t-tests at a 0.05 α-level were used to determine if there were differences in the behavioral performance of the participants between the pre- and postpractice blocks. Cohen’s d values were also calculated to evaluate the effect size of the practice-induced changes seen in the behavioral variables. The calculated effect sizes were interpreted as follows: 0.2 small, 0.5 medium, and >0.8 large (Cohen 1988). Last, Pearson’s correlations were performed to assess the relationship between the percent change in the averaged time series data and the respective motor performance variables.

RESULTS

Motor behavioral results.

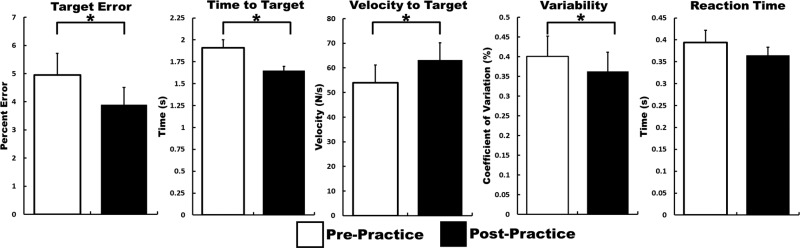

Overall, our results showed that the participants improved their ability to predict the ankle forces that would accurately match the prescribed targets (Fig. 2). After practicing, the participants matched the targets faster (P = 0.003; d = 0.86), had less errors in their force production (P = 0.02; d = 0.39), had a faster velocity of the force production toward the target (P = 0.007; d = 0.34), and had a lower coefficient of variation when attempting to match the target (P = 0.011; d = 0.20). There were no differences in the reaction time after practicing (P = 0.19).

Fig. 2.

Changes in behavioral measurements. White, prepractice block; black, postpractice block. *Significant change from pre-/postpractice at P < 0.05.

Sensor-level results.

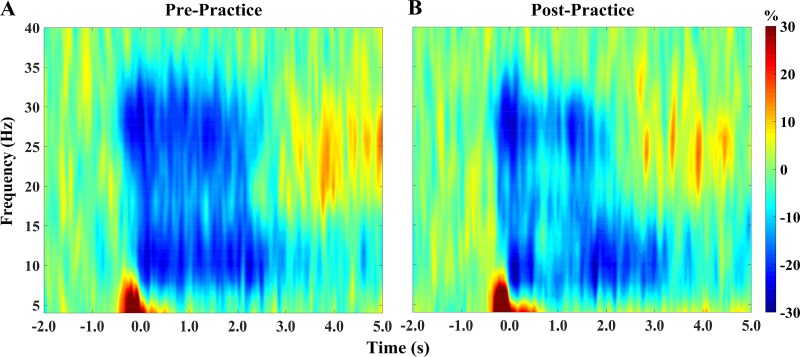

When collapsing the data across the respective blocks (pre- and postpractice), there were significant α (8- to 14-Hz)- and β (24- to 32-Hz)-ERDs that were present in a large number of sensors near the frontoparietal region (P < 0.0001, corrected). These responses in the α-band started near movement onset (0.0 s) and were sustained for ~0.6 s afterward (Fig. 3). The responses in the β-band started ~0.3 s before movement onset and were sustained for ~0.6 s afterward (Fig. 3). For illustrative purposes, we show the pre- and postpractice time frequency plots in Fig. 3 but note that sensor-based statistics were computed by collapsing the data across the pre- and postpractice blocks. Qualitative inspection of these figures shows that the strength of the α- and β-ERDs appeared to become weaker after practice.

Fig. 3.

Group averaged time-frequency spectrograms for prepractice (A) and postpractice (B) blocks. Frequency (Hz) is shown on the y-axis, and time (s) is denoted on the x-axis, with 0 s defined as movement onset. The event-related spectral changes during the ankle plantarflexion target-matching task are expressed as percent difference from baseline (−2.0 to −1.4 s). The magnetoencephalography (MEG) gradiometer with the greatest response amplitude was located near the medial primary sensorimotor cortexes, contralateral to the ankle used during the task. There was a strong desynchronization in the α (8- to 14-Hz)- and β (24- to 32-Hz)-bands in both the pre- and postpractice blocks. As can be discerned, the strength of the α- and β-desynchronization became notably weaker in the postpractice MEG session. The color scale bar for both plots is shown to the far right.

α-Oscillations.

The α (8- to 14-Hz)-ERD identified in the sensor-level analysis within the 0.0- to 0.6-s time window was imaged using a beamformer. This analysis combined the MEG data acquired across the respective blocks and used a baseline period of −2.0 to −1.4 s. The resulting images were grand-averaged and revealed that the α-ERD response was generated by parietal and occipital cortexes (Fig. 4). The local maximums seen in these cortical areas were subsequently used as seeds for extracting virtual sensor time courses (i.e., voxel time courses) from the pre- and postpractice block images. Peaks were found in the left parietal cortex and bilaterally in the occipital. Because the target-matching task was not designed to interrogate hemispheric effects, the two occipital peaks were averaged to create a single time series. Separate paired-samples t-tests were conducted to determine if the average virtual sensor activity during the motor execution stage (0 to 0.6 s) changed after practice in the parietal and occipital cortexes. We did not examine the α-responses after 0.6 s because there were significant changes in the time to match the target following practice, which would have biased any analyses.

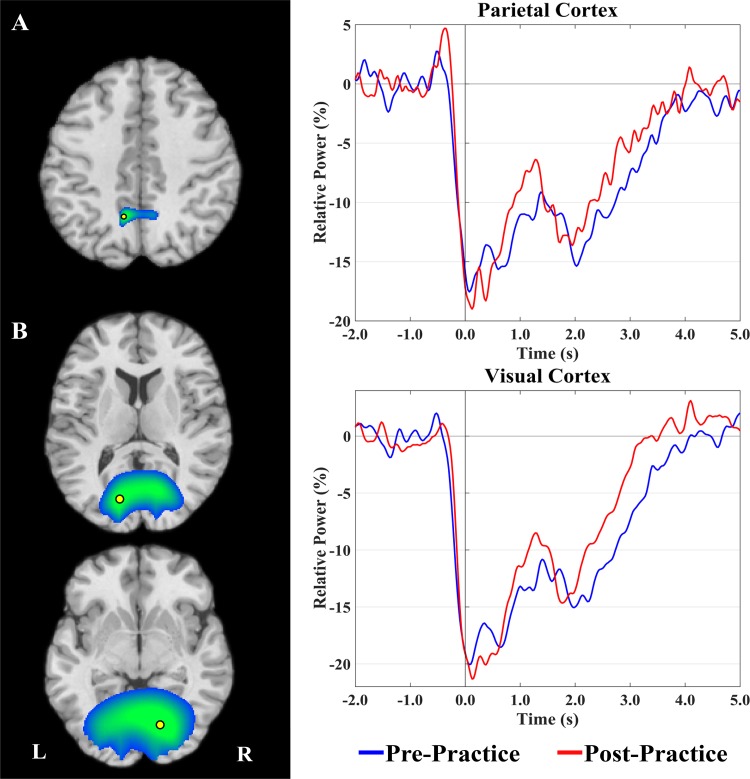

Fig. 4.

Grand averaged beamformer images of α-activity (8–14 Hz) from −0.0 to 0.6 s revealed two main clusters in the parietal (A) and occipital (B) cortexes. Time-series data were extracted from the peak voxel in these clusters (yellow markers) and are plotted with power changes relative to the baseline shown in a percent scale on the y-axis and time on the x-axis in seconds. Bilateral peaks were found in the occipital cortex and were averaged to create a single time series. There were no pre/postpractice differences in the α-event-related desynchronization (ERD) during motor execution (0–0.6 s) in the parietal and occipital cortexes. Note that we did not examine the postmovement α-responses because we had no hypotheses about these and because there were significant behavioral differences between pre- and postpractice that would have biased any analyses. L, left; R, right.

For the left parietal cortex, there was no significant difference in the α-ERD response, indicating that it was not affected by practice (P = 0.31; Fig. 4A). The results for the occipital cortexes were similar, since there were no differences in the α-ERD after practice (P = 0.33; Fig. 4B). Hence, the α-ERD in the left parietal and bilateral occipital cortexes were not affected by practice.

β-Oscillations.

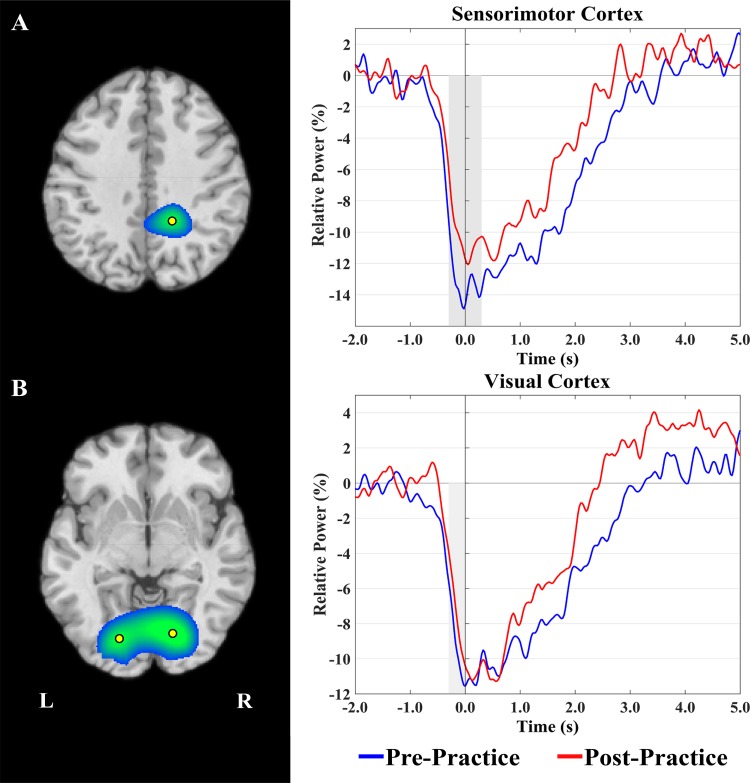

The β (24- to 32-Hz)-ERD identified in the sensor-level analysis between −0.3 and 0.3 s was imaged using a beamformer. As with the α-response, this analysis combined the data acquired across the respective blocks and used a baseline period of −2.0 to −1.4 s. The resulting images indicated that the β-ERD was more centered on the leg region of the sensorimotor cortexes, with additional clusters seen in the occipital cortexes (Fig. 5). The local maximums of these responses were next used as seeds for extracting virtual sensors from the pre- and postpractice data blocks separately. Peaks were found in the leg region of the sensorimotor strip and bilaterally in the occipital cortexes. As with the α-data, the two occipital peaks were averaged to create a single time series since the paradigm was not designed to interrogate hemispheric effects. Because the β-response extended across movement onset (i.e., 0.0 s), we conducted separate repeated-measures ANOVAs (pre/postpractice block × time window) to determine if the average neural activity during the motor-planning (−0.3 to 0 s) and execution stages (0 to 0.3 s) changed after practice in the right sensorimotor and bilateral occipital cortexes. Note that we did not examine the postmovement β-responses (>0.6 s) because there were significant behavioral differences between pre- and postpractice that would have biased any analyses.

Fig. 5.

Grand averaged beamformer images of β-activity (24–32 Hz) from −0.3 to 0.3 s revealed two main clusters in the sensorimotor (A) and occipital (B) cortexes. Time-series data were extracted from the peak voxel in these clusters (yellow markers) and are plotted as in Fig. 4. Bilateral peaks were found in the occipital cortex and were averaged to create a single time series. There was significantly weaker β-event-related desynchronization (ERD) in the sensorimotor cortex during the motor-planning (−0.3 to 0 s) and execution (0–0.3 s) stages after practice. There was also significantly weaker β-ERD in the visual cortex during the motor-planning stage (−0.3 to 0 s) after practice. No differences were detected during the motor execution window (0–0.3 s) in the visual cortex. Significant power differences are denoted by the gray shading. Note that we did not examine the postmovement β-responses because we had no hypotheses about these and because there were significant behavioral differences between pre- and postpractice that would have biased any analyses. L, left; R, right.

For the right sensorimotor cortexes, there was no main effect of time window (P = 0.13), which suggests that the strength of the β-ERD was roughly equivalent across the motor-planning and execution stages. However, there was a significant pre/postpractice main effect (P = 0.03), revealing that the β-ERD was significantly weaker overall after practice (Fig. 5A). The interaction term was not significant (P = 0.25).

For the occipital cortexes, there was a significant main effect of time window (P < 0.01), indicating the power of the β-ERD in the occipital cortexes was weaker during motor planning compared with the motor execution stage. There was no pre/postpractice main effect (P = 0.14). However, the interaction term was significant (P = 0.05), and our follow-up post hoc analyses showed that the β-ERD was significantly weaker in the occipital cortexes during the motor-planning stage after practice (P = 0.05; Fig. 5B).

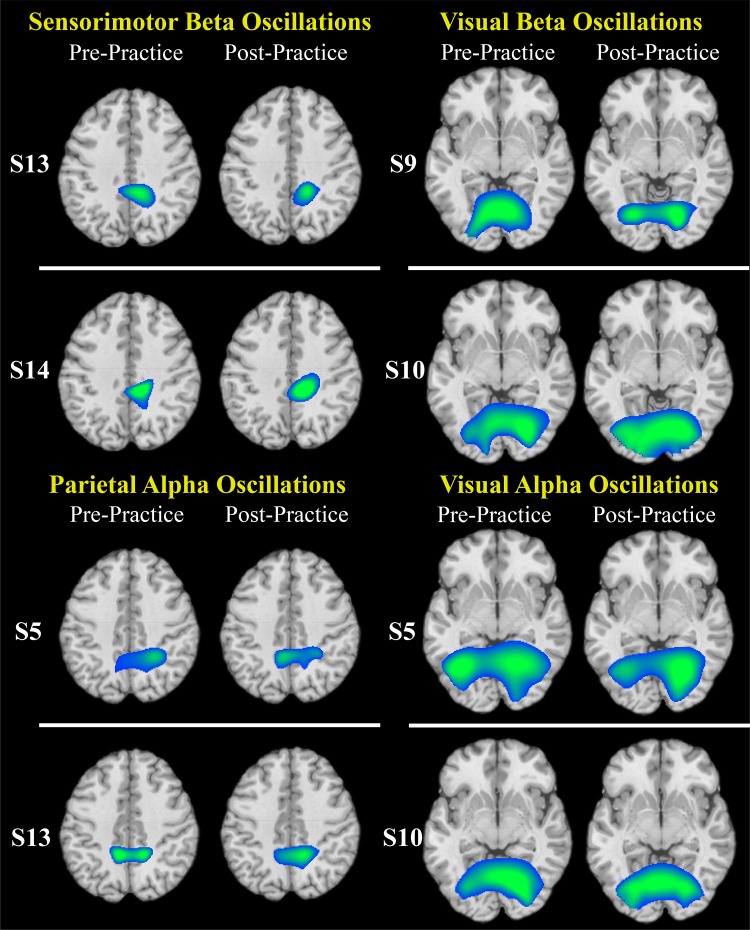

Exemplary images (Fig. 6) are included to demonstrate that the grand average images reflect the activity seen in the individual subjects pre- and postpractice.

Fig. 6.

Exemplary individual images of the respective oscillatory activity. Rows, separate subjects; columns, pre- and postpractice images.

Correlational results.

Although the improvements in the motor performance variables paralleled the changes in the β-cortical oscillations, the amount of change seen in the β-ERDs was not significantly correlated with the respective motor behavioral outcome variables (P values >0.05).

DISCUSSION

There is currently a substantial knowledge gap in our understanding of how the cortical oscillations are altered after practicing a novel motor task. The current study used high-density MEG to begin to fill this knowledge gap by quantifying changes in the cortical oscillations after a short-term practice (e.g., fast motor learning) session of a goal-directed, isometric, target-matching ankle plantarflexion task. At the onset of this investigation, we were primarily driven to identify the potential differences in β-cortical oscillations, since these oscillations are widely known to be involved in the planning and execution of motor actions (Grent-’t-Jong et al. 2014; Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2015; Kurz et al. 2014a, 2016; Pollok et al. 2014; Tzagarakis et al. 2010, 2015). However, the data-driven approach employed in this investigation revealed that there were notable differences in both α- and β-oscillatory activity during the planning and execution of isometric force. Thus, we examined both using our beamforming approach, but in the end our results showed that only the β-cortical oscillations changed after practicing the motor task.

The strength of the β-ERD in the leg region of the sensorimotor cortexes across the motor-planning and execution stages became significantly weaker after practicing the motor task. These results concur with previous fMRI, EEG, and PET investigations that have shown that activation changes primarily reside in the sensorimotor network after practicing a novel motor task (Classen et al. 1998; Galea and Celnik 2009; Galea et al. 2011; Hadipour-Niktarash et al. 2007; Hatfield et al. 2004; Haufler et al. 2000; Hillman et al. 2000; Kranczioch et al. 2008; Orban de Xivry et al. 2011; Reis et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2011). Another common finding is that the size of the activation in the motor cortex decreases after practice (Floyer-Lea and Matthews 2004; Karni et al. 1995; Kelly and Garavan 2005; Petersen et al. 1998; Poldrack 2000). Such reductions in sensorimotor activation, which have been demonstrated over a single practice session (Karni et al. 1995), suggest that less cognitive and/or neural resources are required to successfully preform the task (Kelly and Garavan 2005; Petersen et al. 1998; Poldrack 2000). Potentially, the weaker β-cortical oscillations seen in this investigation might also represent a consolidation of the cortical resources that are necessary for performing the ankle plantarflexion target-matching task.

Practice was also associated with a reduction in the strength of the β-ERD within the occipital cortexes during the motor-planning stage after practice. Prior studies have implied that the occipital cortexes contribute to the visuomotor transformations that are necessary for planning a motor action that will match the prescribed target location (Krigolson et al. 2015; Kurz et al. 2017; Messier and Kalaska 1997; Shadmehr and Mussa-Ivaldi 1994). Hence, we suspect that the weaker β-ERD seen in our study after practice might reflect an improvement in the cortical resources that are needed to compute the transformations that are necessary between the visual representation of the target and the ankle plantarflexion force. Alternatively, the weaker β-ERD could suggest that the weighting of the visual feedback was reduced after practice. This logic is based on previous work that has suggested the weightings of the visual and proprioceptive feedback change as learning occurs and that the change in the balance between these two sensory modalities is dependent on the task constraints (Sober and Sabes 2003, 2005).

Our analysis also identified an α-ERD in parietal and occipital cortexes that was present across the motor-planning and execution stages. The location and timing of these neural oscillations are aligned with the breadth of literature that suggests that activity within these cortical areas is associated with the visuomotor transformations that are necessary for producing and correcting a motor action (Beurze et al. 2007; Buneo and Andersen 2006; Della-Maggiore et al. 2004; Gallivan et al. 2011, 2013; Kurz et al. 2016; Valyear and Frey 2015). Nevertheless, the results of the current experiment imply that motor-related α-oscillations do not appreciably change after short-term practice. These results are somewhat perplexing since prior MEG and EEG studies have noted that α-oscillations in sensors near the sensorimotor cortexes became weaker after practicing a motor sequence with the fingers (Leocani et al. 1997; Pollok et al. 2014). We speculate that these discrepancies might reside in the differences between implicit and explicit learning. The finger motor action sequence learned in these previous studies were acquired implicitly, whereas the ankle motor action learned in this investigation was acquired explicitly. However, although this explanation is conceivable, it needs to be experimentally challenged before it can be fully supported.

Our understanding of the brain networks that serve the planning and execution of motor actions is largely based on experiments with the upper extremities. In fact, there is a vast knowledge gap surrounding the neural regions that are involved in the production of leg motor actions. Studying leg motor actions has historically been more difficult because of the increased probability of head movements, the greater chance of artifacts resulting from the movement of the large leg mass within the MRI scanner’s magnetic field, and the challenge of building magnetically silent devices that can be used to concurrently measure the biomechanics of the leg motor actions while in a supine position (Barry et al. 2010; Seto et al. 2001). Outcomes from the few investigations that have been conducted have shown that the production of self-paced toe, ankle, and knee motor actions arises from the same cortical and subcortical structures seen in the prior upper extremity experiments but emanate from different neural populations following the homuncular map within each structure (Ciccarelli et al. 2005; de Almeida et al. 2015; Dobkin et al. 2004; Johannsen et al. 2001; Kapreli et al. 2006; Luft et al. 2002). However, beyond this anatomical information, we still have limited understanding of how these cortical areas are involved in the planning and production of leg motor actions. The results from this study align with the few MEG studies that have been conducted on the leg motor actions (Arpin et al. 2017; Kurz et al. 2014a, 2016, 2017). In addition, our investigation has extended the outcomes from these few studies by showing that the strength of β-cortical oscillations within the sensorimotor and occipital cortexes becomes weaker after practicing an isometric ankle plantarflexion target matching task. These results further emphasize that the β-cortical oscillations seen during the motor-planning and execution stages play a prominent role in the control of the leg motor actions.

Although the changes in the β-cortical oscillations appeared to parallel the changes in the motor performance variables, these indexes were not directly correlated. We assume that our inability to find a correlation may reflect power limitations because of our moderate sample size and/or the contribution of other brain areas. For example, prior fMRI studies have shown practice-related changes in the cerebellum and basal ganglia and suggested that these reflect an improved mapping of sensorimotor coordinates and more automatic motor actions, respectively (Ashby et al. 2010; Doyon et al. 2002, 2009; Vahdat et al. 2015). Corollary changes in the activity of the spinal cord interneurons have also been seen after practice and have been suggested to reflect an optimization of muscle synergies and motor memories (Vahdat et al. 2015). It is possible that these subcortical and spinal regions start to play a more dominant role in motor control throughout the ongoing practice session, whereas the connectivity between the cortex and spinal cord decreases and cerebellar-striatal networks start to take over for the cerebellar-cortical networks (Doyon et al. 2002, 2009, Doyon and Benali, 2005; Vahdat et al. 2015). However, this is speculative, and further research is necessary. Nevertheless, the continued interaction of all these networks is likely critical for motor learning to occur (Dayan and Cohen 2011; Doyon and Ungerleider 2002; Hikosaka et al. 2002).

Conclusions

Fast motor learning results in a reduced amount of power in the β-ERD seen in the sensorimotor and visual cortexes. These changes likely reflect the reduction in neuronal resources needed to perform a motor action. Alternatively, the changes in the visual cortexes during the planning phase may reflect a reduction of the weighting of visual information. The β-ERD changes were concurrent with improvements in task performance, which indicate these cortical changes reflect fast motor learning.

GRANTS

This work was partially supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R01-HD-086245) and the National Science Foundation (NSF 1539067).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.E.G., T.W.W., and M.J.K. conceived and designed research; J.E.G. and D.J.A. performed experiments; J.E.G., D.J.A., and E.H.-G. analyzed data; J.E.G., D.J.A., E.H.-G., and M.J.K. interpreted results of experiments; J.E.G. prepared figures; J.E.G. and M.J.K. drafted manuscript; J.E.G., T.W.W., and M.J.K. edited and revised manuscript; J.E.G., T.W.W., and M.J.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Alegre M, Labarga A, Gurtubay IG, Iriarte J, Malanda A, Artieda J. Beta electroencephalograph changes during passive movements: sensory afferences contribute to beta event-related desynchronization in humans. Neurosci Lett 331: 29–32, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00825-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arima T, Yanagi Y, Niddam DM, Ohata N, Arendt-Nielsen L, Minagi S, Sessle BJ, Svensson P. Corticomotor plasticity induced by tongue-task training in humans: a longitudinal fMRI study. Exp Brain Res 212: 199–212, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpin DJ, Heinrichs-Graham E, Gehringer JE, Zabad R, Wilson TW, Kurz MJ. Altered sensorimotor cortical oscillations in individuals with multiple sclerosis suggests a faulty internal model. Hum Brain Mapp 38: 4009–4018, 2017. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby FG, Turner BO, Horvitz JC. Cortical and basal ganglia contributions to habit learning and automaticity. Trends Cogn Sci 14: 208–215, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RL, Williams JM, Klassen LM, Gallivan JP, Culham JC, Menon RS. Evaluation of preprocessing steps to compensate for magnetic field distortions due to body movements in BOLD fMRI. Magn Reson Imaging 28: 235–244, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurze SM, de Lange FP, Toni I, Medendorp WP. Integration of target and effector information in the human brain during reach planning. J Neurophysiol 97: 188–199, 2007. doi: 10.1152/jn.00456.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buneo CA, Andersen RA. The posterior parietal cortex: sensorimotor interface for the planning and online control of visually guided movements. Neuropsychologia 44: 2594–2606, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassim F, Szurhaj W, Sediri H, Devos D, Bourriez J, Poirot I, Derambure P, Defebvre L, Guieu J. Brief and sustained movements: differences in event-related (de)synchronization (ERD/ERS) patterns. Clin Neurophysiol 111: 2032–2039, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(00)00455-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheyne D, Bakhtazad L, Gaetz W. Spatiotemporal mapping of cortical activity accompanying voluntary movements using an event-related beamforming approach. Hum Brain Mapp 27: 213–229, 2006. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli O, Toosy AT, Marsden JF, Wheeler-Kingshott CM, Sahyoun C, Matthews PM, Miller DH, Thompson AJ. Identifying brain regions for integrative sensorimotor processing with ankle movements. Exp Brain Res 166: 31–42, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen J, Liepert J, Wise SP, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Rapid plasticity of human cortical movement representation induced by practice. J Neurophysiol 79: 1117–1123, 1998. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Crone NE, Miglioretti DL, Gordon B, Sieracki JM, Wilson MT, Uematsu S, Lesser RP. Functional mapping of human sensorimotor cortex with electrocorticographic spectral analysis. I. Alpha and beta event-related desynchronization. Brain 121: 2271–2299, 1998. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.12.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan E, Cohen LG. Neuroplasticity subserving motor skill learning. Neuron 72: 443–454, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida PM, Vieira AI, Canário NI, Castelo-Branco M, de Castro Caldas AL. Brain activity during lower-limb movement with manual facilitation: an fMRI study. Neurol Res Int 2015: 701452, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/701452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della-Maggiore V, Malfait N, Ostry DJ, Paus T. Stimulation of the posterior parietal cortex interferes with arm trajectory adjustments during the learning of new dynamics. J Neurosci 24: 9971–9976, 2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2833-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin BH, Firestine A, West M, Saremi K, Woods R. Ankle dorsiflexion as an fMRI paradigm to assay motor control for walking during rehabilitation. Neuroimage 23: 370–381, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon J, Bellec P, Amsel R, Penhune V, Monchi O, Carrier J, Lehéricy S, Benali H. Contributions of the basal ganglia and functionally related brain structures to motor learning. Behav Brain Res 199: 61–75, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon J, Benali H. Reorganization and plasticity in the adult brain during learning of motor skills. 2005 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, July 31–August 4, 2005. doi: 10.1109/ijcnn.2005.1556102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon J, Song AW, Karni A, Lalonde F, Adams MM, Ungerleider LG. Experience-dependent changes in cerebellar contributions to motor sequence learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 1017–1022, 2002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022615199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon J, Ungerleider LG. Functional anatomy of motor skill learning. In: Neuropsychology of Memory, edited by Squire LR, Schacter DL. New York: Guilford, 2002, p. 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst MD. Permutation methods: a basis for exact inference. Stat Sci 19: 676–685, 2004. doi: 10.1214/088342304000000396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Nitschke MF, Melchert UH, Erdmann C, Born J. Motor memory consolidation in sleep shapes more effective neuronal representations. J Neurosci 25: 11248–11255, 2005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1743-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyer-Lea A, Matthews PM. Changing brain networks for visuomotor control with increased movement automaticity. J Neurophysiol 92: 2405–2412, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.01092.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyer-Lea A, Matthews PM. Distinguishable brain activation networks for short- and long-term motor skill learning. J Neurophysiol 94: 512–518, 2005. doi: 10.1152/jn.00717.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea JM, Celnik P. Brain polarization enhances the formation and retention of motor memories. J Neurophysiol 102: 294–301, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.00184.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea JM, Vazquez A, Pasricha N, de Xivry JJ, Celnik P. Dissociating the roles of the cerebellum and motor cortex during adaptive learning: the motor cortex retains what the cerebellum learns. Cereb Cortex 21: 1761–1770, 2011. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan JP, McLean DA, Flanagan JR, Culham JC. Where one hand meets the other: limb-specific and action-dependent movement plans decoded from preparatory signals in single human frontoparietal brain areas. J Neurosci 33: 1991–2008, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0541-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan JP, McLean DA, Valyear KF, Pettypiece CE, Culham JC. Decoding action intentions from preparatory brain activity in human parieto-frontal networks. J Neurosci 31: 9599–9610, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0080-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafton ST, Hazeltine E, Ivry RB. Motor sequence learning with the nondominant left hand. A PET functional imaging study. Exp Brain Res 146: 369–378, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1181-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grent-’t-Jong T, Oostenveld R, Jensen O, Medendorp WP, Praamstra P. Competitive interactions in sensorimotor cortex: oscillations express separation between alternative movement targets. J Neurophysiol 112: 224–232, 2014. doi: 10.1152/jn.00127.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Kujala J, Hamalainen M, Timmermann L, Schnitzler A, Salmelin R. Dynamic imaging of coherent sources: studying neural interactions in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 694–699, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadipour-Niktarash A, Lee CK, Desmond JE, Shadmehr R. Impairment of retention but not acquisition of a visuomotor skill through time-dependent disruption of primary motor cortex. J Neurosci 27: 13413–13419, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2570-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield BD, Haufler AJ, Hung TM, Spalding TW. Electroencephalographic studies of skilled psychomotor performance. J Clin Neurophysiol 21: 144–156, 2004. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haufler AJ, Spalding TW, Santa Maria DL, Hatfield BD. Neuro-cognitive activity during a self-paced visuospatial task: comparative EEG profiles in marksmen and novice shooters. Biol Psychol 53: 131–160, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0511(00)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E, Arpin DJ, Wilson TW. Cue-related temporal factors modulate movement-related beta oscillatory activity in the human motor circuit. J Cogn Neurosci 28: 1039–1051, 2016. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. Coding complexity in the human motor circuit. Hum Brain Mapp 36: 5155–5167, 2015. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. Is an absolute level of cortical beta suppression required for proper movement? Magnetoencephalographic evidence from healthy aging. Neuroimage 134: 514–521, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O, Nakamura K, Sakai K, Nakahara H. Central mechanisms of motor skill learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol 12: 217–222, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand A, Barnes GR. Beamformer analysis of MEG data. In: International Review of Neurobiology. New York: Elsevier, 2005, p. 149–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand A, Singh KD, Holliday IE, Furlong PL, Barnes GR. A new approach to neuroimaging with magnetoencephalography. Hum Brain Mapp 25: 199–211, 2005. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman CH, Apparies RJ, Janelle CM, Hatfield BD. An electrocortical comparison of executed and rejected shots in skilled marksmen. Biol Psychol 52: 71–83, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0511(99)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda M, Deiber MP, Ibanez V, Pascual-Leone A, Zhuang P, Hallett M. Dynamic cortical involvement in implicit and explicit motor sequence learning. A PET study. Brain 12: 2159–2173, 1998. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.11.2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang VS, Haith A, Mazzoni P, Krakauer JW. Rethinking motor learning and savings in adaptation paradigms: model-free memory for successful actions combines with internal models. Neuron 70: 787–801, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang EJ, Shadmehr R. Internal models of limb dynamics and the encoding of limb state. J Neural Eng 2: S266–S278, 2005. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/2/3/S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen P, Christensen LO, Sinkjaer T, Nielsen JB. Cerebral functional anatomy of voluntary contractions of ankle muscles in man. J Physiol 535: 397–406, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkiewicz MT, Gaetz WC, Bostan AC, Cheyne D. Post-movement beta rebound is generated in motor cortex: evidence from neuromagnetic recordings. Neuroimage 32: 1281–1289, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser J, Birbaumer N, Lutzenberger W. Event-related beta desynchronization indicates timing of response selection in a delayed-response paradigm in humans. Neurosci Lett 312: 149–152, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapreli E, Athanasopoulos S, Papathanasiou M, Van Hecke P, Strimpakos N, Gouliamos A, Peeters R, Sunaert S. Lateralization of brain activity during lower limb joints movement. An fMRI study. Neuroimage 32: 1709–1721, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni A, Meyer G, Jezzard P, Adams MM, Turner R, Ungerleider LG. Functional MRI evidence for adult motor cortex plasticity during motor skill learning. Nature 377: 155–158, 1995. doi: 10.1038/377155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AM, Garavan H. Human functional neuroimaging of brain changes associated with practice. Cereb Cortex 15: 1089–1102, 2005. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilner JM, Vargas C, Duval S, Blakemore SJ, Sirigu A. Motor activation prior to observation of a predicted movement. Nat Neurosci 7: 1299–1301, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nn1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluzik J, Diedrichsen J, Shadmehr R, Bastian AJ. Reach adaptation: what determines whether we learn an internal model of the tool or adapt the model of our arm? J Neurophysiol 100: 1455–1464, 2008. doi: 10.1152/jn.90334.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korman M, Raz N, Flash T, Karni A. Multiple shifts in the representation of a motor sequence during the acquisition of skilled performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 12492–12497, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2035019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranczioch C, Athanassiou S, Shen S, Gao G, Sterr A. Short-term learning of a visually guided power-grip task is associated with dynamic changes in EEG oscillatory activity. Clin Neurophysiol 119: 1419–1430, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krigolson OE, Cheng D, Binsted G. The role of visual processing in motor learning and control: insights from electroencephalography. Vision Res 110: 277–285, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz MJ, Becker KM, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. Neurophysiological abnormalities in the sensorimotor cortices during the motor planning and movement execution stages of children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 56: 1072–1077, 2014a. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz MJ, Heinrichs-Graham E, Arpin DJ, Becker KM, Wilson TW. Aberrant synchrony in the somatosensory cortices predicts motor performance errors in children with cerebral palsy. J Neurophysiol 111: 573–579, 2014b. doi: 10.1152/jn.00553.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz MJ, Heinrichs-Graham E, Becker KM, Wilson TW. The magnitude of the somatosensory cortical activity is related to the mobility and strength impairments seen in children with cerebral palsy. J Neurophysiol 113: 3143–3150, 2015. doi: 10.1152/jn.00602.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz MJ, Proskovec AL, Gehringer JE, Becker KM, Arpin DJ, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. Developmental trajectory of beta cortical oscillatory activity during a knee motor task. Brain Topogr 29: 824–833, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s10548-016-0500-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz MJ, Proskovec AL, Gehringer JE, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. Children with cerebral palsy have altered oscillatory activity in the motor and visual cortices during a knee motor task. Neuroimage Clin 15: 298–305, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leocani L, Toro C, Manganotti P, Zhuang P, Hallett M. Event-related coherence and event-related desynchronization/synchronization in the 10 Hz and 20 Hz EEG during self-paced movements. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 104: 199–206, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0168-5597(96)96051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft AR, Smith GV, Forrester L, Whitall J, Macko RF, Hauser TK, Goldberg AP, Hanley DF. Comparing brain activation associated with isolated upper and lower limb movement across corresponding joints. Hum Brain Mapp 17: 131–140, 2002. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris E, Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J Neurosci Methods 164: 177–190, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier J, Kalaska JF. Differential effect of task conditions on errors of direction and extent of reaching movements. Exp Brain Res 115: 469–478, 1997. doi: 10.1007/PL00005716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KJ, Schalk G, Fetz EE, den Nijs M, Ojemann JG, Rao RP. Cortical activity during motor execution, motor imagery, and imagery-based online feedback. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 4430–4435, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913697107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner TE, Franklin DW. Impedance control and internal model use during the initial stage of adaptation to novel dynamics in humans. J Physiol 567: 651–664, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muellbacher W, Ziemann U, Wissel J, Dang N, Kofler M, Facchini S, Boroojerdi B, Poewe W, Hallett M. Early consolidation in human primary motor cortex. Nature 415: 640–644, 2002. doi: 10.1038/nature712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orban de Xivry JJ, Criscimagna-Hemminger SE, Shadmehr R. Contributions of the motor cortex to adaptive control of reaching depend on the perturbation schedule. Cereb Cortex 21: 1475–1484, 2011. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen SE, van Mier H, Fiez JA, Raichle ME. The effects of practice on the functional anatomy of task performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 853–860, 1998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfurtscheller G, Berghold A. Patterns of cortical activation during planning of voluntary movement. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 72: 250–258, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(89)90250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfurtscheller G, Graimann B, Huggins JE, Levine SP, Schuh LA. Spatiotemporal patterns of beta desynchronization and gamma synchronization in corticographic data during self-paced movement. Clin Neurophysiol 114: 1226–1236, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(03)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA. Imaging brain plasticity: conceptual and methodological issues—a theoretical review. Neuroimage 12: 1–13, 2000. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollok B, Latz D, Krause V, Butz M, Schnitzler A. Changes of motor-cortical oscillations associated with motor learning. Neuroscience 275: 47–53, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis J, Schambra HM, Cohen LG, Buch ER, Fritsch B, Zarahn E, Celnik PA, Krakauer JW. Noninvasive cortical stimulation enhances motor skill acquisition over multiple days through an effect on consolidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 1590–1595, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805413106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson EM, Pascual-Leone A, Miall RC. Current concepts in procedural consolidation. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 576–582, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nrn1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco K, Cauda F, Cerliani L, Mate D, Duca S, Geminiani GC. Motor imagery of walking following training in locomotor attention. The effect of “the tango lesson”. Neuroimage 32: 1441–1449, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco K, Cauda F, D’Agata F, Mate D, Duca S, Geminiani G. Reorganization and enhanced functional connectivity of motor areas in repetitive ankle movements after training in locomotor attention. Brain Res 1297: 124–134, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Hikosaka O, Miyauchi S, Sasaki Y, Fujimaki N, Pütz B. Presupplementary motor area activation during sequence learning reflects visuo-motor association. J Neurosci 19: RC1, 1999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-j0002.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto E, Sela G, McIlroy WE, Black SE, Staines WR, Bronskill MJ, McIntosh AR, Graham SJ. Quantifying head motion associated with motor tasks used in fMRI. Neuroimage 14: 284–297, 2001. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R. Generalization as a behavioral window to the neural mechanisms of learning internal models. Hum Mov Sci 23: 543–568, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Holcomb HH. Neural correlates of motor memory consolidation. Science 277: 821–825, 1997. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Mussa-Ivaldi FA. Adaptive representation of dynamics during learning of a motor task. J Neurosci 14: 3208–3224, 1994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03208.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Shadmehr R. Intact ability to learn internal models of arm dynamics in Huntington’s disease but not cerebellar degeneration. J Neurophysiol 93: 2809–2821, 2005. doi: 10.1152/jn.00943.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sober SJ, Sabes PN. Multisensory integration during motor planning. J Neurosci 23: 6982–6992, 2003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-06982.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sober SJ, Sabes PN. Flexible strategies for sensory integration during motor planning. Nat Neurosci 8: 490–497, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nn1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamás Kincses Z, Johansen-Berg H, Tomassini V, Bosnell R, Matthews PM, Beckmann CF. Model-free characterization of brain functional networks for motor sequence learning using fMRI. Neuroimage 39: 1950–1958, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulu S, Simola J. Spatiotemporal signal space separation method for rejecting nearby interference in MEG measurements. Phys Med Biol 51: 1759–1768, 2006. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/7/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoroughman KA, Shadmehr R. Electromyographic correlates of learning an internal model of reaching movements. J Neurosci 19: 8573–8588, 1999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08573.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzagarakis C, Ince NF, Leuthold AC, Pellizzer G. Beta-band activity during motor planning reflects response uncertainty. J Neurosci 30: 11270–11277, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6026-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzagarakis C, West S, Pellizzer G. Brain oscillatory activity during motor preparation: effect of directional uncertainty on beta, but not alpha, frequency band. Front Neurosci 9: 246, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahdat S, Lungu O, Cohen-Adad J, Marchand-Pauvert V, Benali H, Doyon J. Simultaneous brain-cervical cord fMRI reveals intrinsic spinal cord plasticity during motor sequence learning. PLoS Biol 13: e1002186, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valyear KF, Frey SH. Human posterior parietal cortex mediates hand-specific planning. Neuroimage 114: 226–238, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Veen BD, van Drongelen W, Yuchtman M, Suzuki A. Localization of brain electrical activity via linearly constrained minimum variance spatial filtering. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 44: 867–880, 1997. doi: 10.1109/10.623056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP, Brakefield T, Morgan A, Hobson JA, Stickgold R. Practice with sleep makes perfect: sleep-dependent motor skill learning. Neuron 35: 205–211, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingham DB. A neuropsychological theory of motor skill learning. Psychol Rev 105: 558–584, 1998. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.105.3.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TW, Heinrichs-Graham E, Becker KM. Circadian modulation of motor-related beta oscillatory responses. Neuroimage 102: 531–539, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TW, Heinrichs-Graham E, Proskovec AL, McDermott TJ. Neuroimaging with magnetoencephalography: a dynamic view of brain pathophysiology. Transl Res 175: 17–36, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TW, Slason E, Asherin R, Kronberg E, Reite ML, Teale PD, Rojas DC. An extended motor network generates beta and gamma oscillatory perturbations during development. Brain Cogn 73: 75–84, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TW, Slason E, Asherin R, Kronberg E, Teale PD, Reite ML, Rojas DC. Abnormal gamma and beta MEG activity during finger movements in early-onset psychosis. Dev Neuropsychol 36: 596–613, 2011. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2011.555573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert DM. Probabilistic models in human sensorimotor control. Hum Mov Sci 26: 511–524, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Xu L, Wang S, Xie B, Guo J, Long Z, Yao L. Behavioral improvements and brain functional alterations by motor imagery training. Brain Res 1407: 38–46, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]