Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a leading cause of death globally among infectious diseases that has killed more numbers of people than any other infectious diseases. Animal models have become the lynchpin for mimicking human infectious diseases. Research on TB could be facilitated by animal challenge models such as the guinea pig, mice, rabbit and non-human primates. No single model presents all aspects of disease pathogenesis due to considerable differences in disease resistance/susceptibility between these models. Availability of a wide range of animal strains, Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains, route of infection and doses affect the disease progression and intervention outcome. Different animal models have contributed significantly to the drug and vaccine development, identification of biomarkers, understanding of TB immunopathogenesis and host genetic influence on infection. In this review, the commonly used animal models in TB research are discussed along with their advantages and limitations.

Keywords: Animal models, drug development, granuloma, latent model, susceptibility, tuberculosis, vaccine

Introduction

Data from the World Health Organization suggest that about one-third of the global population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and almost 10.4 million active tuberculosis (TB) cases were reported in 20171. To meet the specific targets set in ‘End TB Strategy’2, there is the need for improved strategies for disease prevention and treatment. Control strategies require the urgent development of vaccines and therapeutics which can be applied both prophylactically and post-exposure as a preventive intervention. Preventive strategies have relied upon Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, which is one of the most widely injected vaccines in humankind, administered predominantly in neonates3. Although delamanid and bedaquiline are newly approved drugs after a gap of 40 years for the treatment of multidrug-resistant TB4; new molecules are still needed to end TB by 2030.

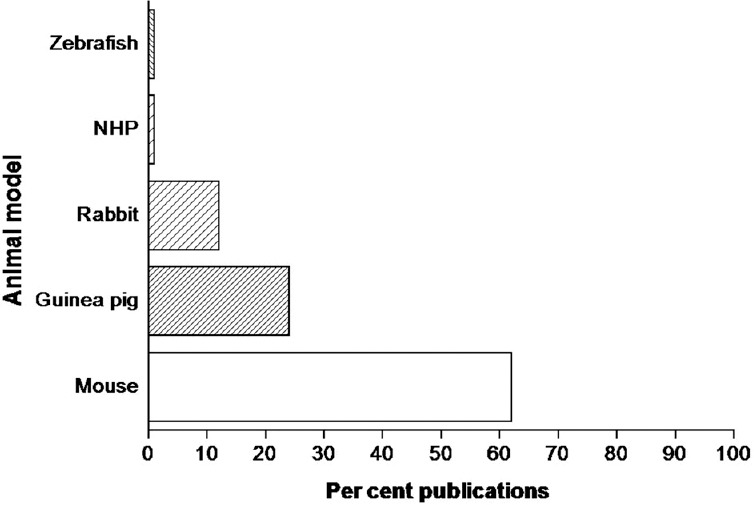

Different pre-clinical models (mice, rat, rabbits, guinea pigs, nonhuman primates, etc.) have been employed for evaluating new therapies and vaccines for controlling TB and have been the lynchpin for TB studies5,6. Robert Koch used guinea pig to reveal the tubercle bacillus as the presumed cause of TB7. Analysis of the proportion of different pre-clinical animal models used in TB research is shown in the Figure8.

Figure.

Histogram showing proportion of different pre-clinical animal models used in TB research. Search terms either mouse or guinea pig or rabbit or non-human primate (NHP) or Zebrafish with tuberculosis were used for searches on PubMed on March 12, 2018. The results are converted into percentage based on the number of publications retrieved for animal models as done by Fonseca et al8.

The success of animal models in TB research is credited to advancement in techniques of animal infection by the aerosol route and manifestation of innate and adaptive immune response to control the growth of bacilli followed by the disease development and thus has provided an invaluable contribution in improving our understanding. To further accelerate the research on TB, we need to generate an in-depth understanding of human TB and translate those findings to identify the animal model systems that may speed up ‘bench to bed’ translation by the evaluation of vaccine and therapeutic interventions and predict TB relapse.

This review deals with the commonly used preclinical models in TB research besides discussing less popular in vivo animal models and the limitations of these models with respect to disease pathogenesis and immunology and perspectives associated with them.

Preclinical animal models utilized in TB research

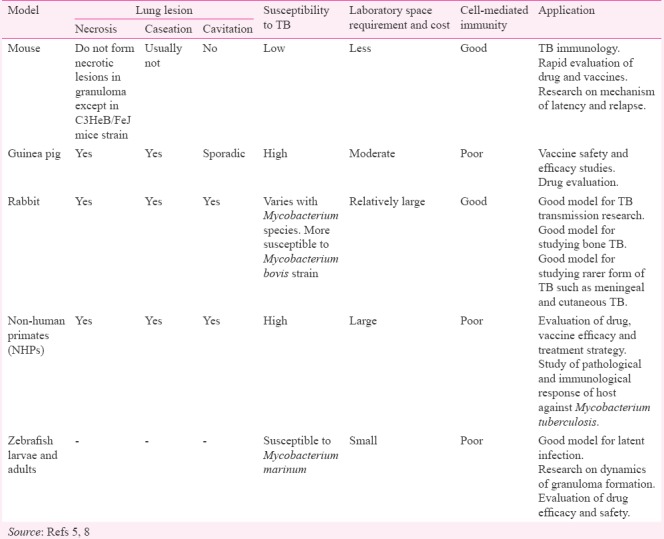

The contribution of different preclinical animal models in TB research is significant and these animal models have been the cornerstone in enhancing our understanding regarding the disease5,9. Pre-clinical models have provided detailed information into the disease mechanism and are used for pre-clinical testing of different drug and vaccine candidates. The overlaps between human and animal physiology provide a valuable framework to understand the human systems. Animal models of pulmonary TB, particularly mice and guinea pigs are being extensively used to study host response, immunopathology, evaluation of new treatment regimens and the protective effect of new vaccine candidates throughout the world10. Although each model has advantages and disadvantages, their contributions are substantial in studying the diseases which are otherwise difficult to study directly in humans Table.

Table.

Characteristics and utilization of tuberculosis (TB) animal models

Mouse

The mouse is a preferred animal model for numerous practical reasons, such as simple handling, low cost, less space requirement, the presence of immunological tools and availability of both inbred, outbred and transgenic strains11. Despite having similar immune responses as human following M. tuberculosis infection, there is a difference in disease pathology that weighs down the use of mouse model for the study12. Standardization of low-dose aerosol infection technique in mouse model appeared to be a hallmark in the screening of new vaccines and drug candidates13. The present drug regimen successfully demonstrated the treatment potential in mice experiments before moving to clinical trial14. However, the absence of pathological hallmarks after infection with M. tuberculosis such as caseating granulomas including lung cavitations in the mouse strain is a potential limitation15. Bacilli reside primarily intracellularly in the lungs of popular mouse models such as BALB/c and C57BL/6, and the host lung develops inflammatory, but non-necrotic lesion16. It is in contrast to human TB and other animal models, where the disease is progressive with necrotic lesions in which majority of bacteria are extracellular within the lesion17. Therefore, it has been put forward that sterilizing activity of new TB drug/regimen observed in the mouse model may not be observed in other animal models or clinical trials18. Despite these limitations, the mouse model has been instrumental in testing and predicting drug combinations with the treatment potential for TB19,20.

Mouse strains depending upon the genotype vary in susceptibility to infection to virulent M. tuberculosis which may translate into treatment outcomes21. C57BL/6 mice are more resistant than BALB/c mice in terms of survival time post-infection with the decline in colony forming unit (cfu) counts after the onset of adaptive immunity22. A study in C3HeB/FeJ mice following M. tuberculosis infection has demonstrated necrotic granulomas which are more similar to that in humans23. The research indicates that the caseating lesions impact drug efficacy between BALB/c and C3HeB/FeJ mice and requires further study24,25,26. Husain et al27 reported cerebral TB model in BALB/c mice using aerosol infection with clinical strain.

Mice have been the most extensively used animal for vaccine discovery for numerous reasons. Mouse models being economical are the most widely used and characterized and since they are used as a study model for various other diseases have propelled availability of well-characterized immunological reagents for research28. The C57B1/6 is the most commonly used mouse strain for vaccine research, and novel vaccine candidates should reduce the bacillary load in mouse lung by at least 0.7 log10 cfu as observed in BCG-vaccinated mice when compared to unvaccinated control28,29. The lung pathology in C3HeB/FeJ mice model following infection with M. tuberculosis was similar as observed in human, which prompted its use as an in vivo model for the evaluation of new vaccine candidates30.

The lack of similarity in immunological responses between the mouse model and humans has prompted to develop the humanized mice for TB research. Development of humanized mice involves the use of human haematopoietic stem cells for reconstitution of immunodeficient mouse31. Granulomatous lesions in humanized mice following M. tuberculosis infections are similar to the one observed in human TB disease. However, researchers have also observed impaired bacterial control and abnormal T-cell responses in certain cases following M. tuberculosis infection32. The recent study has demonstrated that humanized mice have a good potential for the study of HIV/TB33. However, further research is required to standardize the humanized mice model for TB research.

Guinea pig

Guinea pigs contributed substantially as the preclinical model in the early years of TB drug development because of their high susceptibility to infection with M. tuberculosis5,9. Guinea pig after low-dose experimental infection with M. tuberculosis displays many of the aspects of human infection and forms necrotic primary granulomas34. Several novel drug regimens have shown synergism in guinea pigs, and the results of phase 3 trials will provide evidence at predicting the accuracy of the sterilizing activity observed in guinea pig models35,36.

The guinea pig model has been used previously to detect sample positivity until the advent of culture medium and development of rapid diagnostic tests28. The similarity in TB features between the guinea pig and humans has led to further evaluate drug and vaccine candidates which have performed well in the initial screening in mice37. Further, the large size of guinea pigs helps the researchers to perform more analyses in the same animal. The wide range of vaccine types including glycolipid antigens can be evaluated because of the presence of CD1b that responds to glycolipid antigens38. The demonstration of efficacy in this model is currently the gold standard to progress toward clinical trials. Latent TB model has also been used in the guinea pigs, after short-term chemotherapy from week four post-challenge39,40.

Even though the guinea pigs are the relatively economic model and more similar to human in terms of lung pathology following M. tuberculosis infection, some characteristics features of human TB are not displayed6. Guinea pigs are noticeably more expensive than mice and require the daily supply of vitamin C in the diet5. In addition, guinea pigs maintenance is difficult and restricted availability of immunological reagents limits their use. However, guinea pigs may be useful as a model to study the persistent TB infection and to confirm the sterilizing activity of anti-TB compound observed in earlier animal models.

Rabbit

Rabbits occupy an important niche within the animal models for TB research and display the varying level of resistance to M. tuberculosis infection as observed in human depending upon rabbit genotype. Rabbits similar to non-human primate (NHP) model of pulmonary TB, capture most disease pathologies including the formation of cavitary disease seen in human TB. Rabbit spinal TB models are the best model to evaluate drug/regimen efficacy for bone TB41. Rabbits are less susceptible than the guinea pigs for M. tuberculosis infection and susceptibility varies with the strain. Rabbits are highly susceptible to Mycobacterium bovis. Infection with M. tuberculosis H37Rv and Erdman is mostly cleared though Erdman strain establishes a chronic disease with coalescing or caseous lesions in 53 per cent of rabbits42. However, aerosol infection of M. tuberculosis strain HN878 resulted in granuloma formation and cavity production and recapitulates many of the human features of TB43.

Cavitary lesions in case of TB disease are associated with induction of bacterial phenotypic antibiotic resistance after treatment. Researchers using the rabbit model showed that anti-vascular endothelial growth factors treatment normalized TB granuloma vasculature and decreased hypoxia in TB granulomas, thereby improving the efficacy of treatment regimen44. Rabbit model is well suited for demonstrating drug penetration, distribution, and cellular accumulation into well-structured TB lesion within the lung45. Although rabbit has been used scantly for evaluating combination therapy, yet a few researchers have used positron emission tomography (PET)-computed tomography (CT) in the rabbit model to demonstrate infection dynamics and response to chemotherapy46.

Rabbits are the good model for TB transmission research. However, rabbits are not a very popular model for TB research because of their increased size and advance biocontainment requirement. There is a lack of relevant immunological reagents and clinical symptoms are not obvious in the rabbit. Further, rabbits also shed M. tuberculosis in the urine, leading to biocontainment concern. Moreover, inter-current infections with Pasteurella organisms and Bordetella bronchiseptica affect the outcome of an intervention.

Non-human primates

NHPs share a close evolutionary relationship with humans and develop TB disease with a clinical spectrum overlapping to that of humans. NHPs also are preferred model for the simian immunodeficiency virus and can be used to study HIV/TB co-infection47. Although the use of NHPs is associated with multiple challenges such as low availability and great expense in housing and experimentation, the model has been widely used for the evaluation of TB drug and vaccine efficacy48,49.

Cynomolgus macaques are good as model for latent TB because of relative resistance to M. tuberculosis while rhesus macaques are more susceptible50. Studies in NHPs using computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET-CT) allowed a better understanding of the progression of infection to disease51. Biochemical reagents for immunological studies are widely available because of considerable cross-reactivity with human, further facilitating the use of this model system to study TB.

NHPs have also contributed to the evaluation of drug molecules/regimen for the treatment efficacy against TB disease. The pharmacokinetic profiles are similar in NHPs and human enabling simple allometric-based dose calculations52. Evaluation of metronidazole in latent NHP model demonstrated beneficial effect although it did not appear to increase the activity of rifabutin and isoniazid in active disease53. Overall, NHPs may be used to generate information on microbial persistence and to facilitate the development of new molecules.

The difference in inherent susceptibility between macaque species affect the efficacy of BCG vaccination and therefore, is an important factor in determining whether protection may be observed with new vaccine candidates28. Challenge dose and route in NHPs model affect the study outcome. In one study, variable BCG efficacy was observed in rhesus monkey following pulmonary or intradermal vaccination with pulmonary BCG administration protected against M. tuberculosis challenge whereas standard intradermal vaccination failed54. Further, ultra low dose aerosol infection of rhesus and cynomolgus macaques resulted in a more progressive disease in rhesus macaques, while cynomolgus macaques showed reduced disease burden55. Thus, there is need to harmonize the methodology for evaluation of drug/vaccine candidates.

Zebrafish

A natural host-pathogen pair, i.e., zebrafish-Mycobacterium marinum has demonstrated its utility as the model in recent years in TB research. Zebrafish have become alternative to other routine experimental animal models for studying the TB disease pathogenesis, drug and vaccine development. The immune system of zebrafish has similar primary components such as humans despite anatomical differences between them56,57. There is 85 per cent similarity between M. tuberculosis and M. marinum genome58. M. marinum causes a systemic disease in zebrafish with granuloma formation, which is structurally similar to human TB granuloma59. M. marinum infection in zebrafish model highlights the disease phases including latency and reactivation as observed in human TB60.

In a laboratory setting, the zebrafish-M. marinum models are a good choice for TB research for several reasons: (i) Both zebrafish embryos and adults can be easily infected with M. marinum using multiple techniques61; (ii) Embryo optical transparency has helped scientists to use advanced imaging techniques for study purpose. Zebrafish model can be subjected to genetic manipulations easily which allows the researchers for deep mechanistic molecular studies; (iii) Zebrafish requires relatively lesser laboratory space and produces numerous offspring, thereby enabling large-scale screening studies, including drug screens and teratogenicity studies57; (iv) The treatment duration and emergence of drug-resistant bacteria are the two major and correlated issues in TB drug development. The zebrafish larvae can serve as a suitable model for large-scale screening and early-stage drug development62,63. For example, studies in zebrafish model revealed the role of the efflux pump in acquiring a tolerance against antibiotics by M. tuberculosis bacteria, and it was further demonstrated that efflux pump inhibitor such as verapamil reversed the phenomenon and enhanced treatment success64; (v) Host immunity against mycobacteria is mediated by cytokines and their respective receptors. Leukotriene A4 hydrolase locus, present in both humans and zebrafish larvae, regulates the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators and thus affects inflammatory cytokines expression65. Studies in zebrafish model can explicate the control mechanisms of the host immune responses and provide the platform for developing new drugs/host-directed therapies65,66, and (vi) The adult zebrafish is a promising model for early vaccine development and devising different vaccination strategies. A DNA-based vaccine consisting of Ag85, ESAT-6 and CFP-10 mycobacterial antigens demonstrated similar results in zebrafish model as observed earlier in other TB models67. However, like other models, zebrafish is not an exception and have some limitations. There are anatomical and physiological differences between zebrafish and humans, which limit the use of this model. Zebrafish requires specific housing facilities such as other animal models and is more sensitive to different diseases, which further restricts its use.

Conclusion

Despite the availability of a number of the animal models, none of the models recapitulates all aspects of human TB. Further, to establish the efficacy of newly developed drug/regimen; data across the two species are required for further development. It has led to increased advocacy for the use of human-based models to complement and reduce the use of experimental in vivo research. Despite all these limitations, animal models have helped in our understanding of TB and have allowed researchers to elucidate complex pathways involving host-pathogen interaction, drug and vaccine discovery in a well-defined, reproducible and cost-efficient way. Development of advanced imaging technologies for animal models will help in the rapid assessment of therapies and experimental vaccines, thereby saving time and money before moving to costly clinical trials.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2017. Geneva: WHO; 2017. [accessed on March 7, 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO End TB Strategy. Global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015. Geneva: WHO; 2014. [accessed on March 7, 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/post2015_strategy/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luca S, Mihaescu T. History of BCG vaccine. Maedica (Buchar) 2013;8:53–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Migliori GB, Pontali E, Sotgiu G, Centis R, D’Ambrosio L, Tiberi S, et al. Combined use of delamanid and bedaquiline to treat multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: A systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2) doi: 10.3390/ijms18020341. pii: E341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta UD, Katoch VM. Animal models of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2005;85:277–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta UD, Katoch VM. Animal models of tuberculosis for vaccine development. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cambau E, Drancourt M. Steps towards the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Robert Koch, 1882. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:196–201. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonseca KL, Rodrigues PNS, Olsson IAS, Saraiva M. Experimental study of tuberculosis: From animal models to complex cell systems and organoids. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006421. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dharmadhikari AS, Nardell EA. What animal models teach humans about tuberculosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:503–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0154TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orme IM, Ordway DJ. Mouse and guinea pig models of tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(4):TBTB2. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.TBTB2-0002-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandamme TF. Use of rodents as models of human diseases. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2014;6:2–9. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.124301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apt A, Kramnik I. Man and mouse TB: Contradictions and solutions. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;89:195–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orme IM. A mouse model of the recrudescence of latent tuberculosis in the elderly. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:716–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerantzas CA, Jacobs WR., Jr Origins of combination therapy for tuberculosis: Lessons for future antimicrobial development and application. MBio. 2017;8(2) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01586-16. pii: e01586-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ordonez AA, Tasneen R, Pokkali S, Xu Z, Converse PJ, Klunk MH, et al. Mouse model of pulmonary cavitary tuberculosis and expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Dis Model Mech. 2016;9:779–88. doi: 10.1242/dmm.025643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoff DR, Ryan GJ, Driver ER, Ssemakulu CC, De Groote MA, Basaraba RJ, et al. Location of intra- and extracellular M. tuberculosis populations in lungs of mice and guinea pigs during disease progression and after drug treatment. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramnik I, Beamer G. Mouse models of human TB pathology: Roles in the analysis of necrosis and the development of host-directed therapies. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:221–37. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dooley KE, Phillips PP, Nahid P, Hoelscher M. Challenges in the clinical assessment of novel tuberculosis drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;102:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta A, Sharma D, Meena J, Pandya S, Sachan M, Kumar S, et al. Preparation and preclinical evaluation of inhalable particles containing rapamycin and anti-tuberculosis agents for induction of autophagy. Pharm Res. 2016;33:1899–912. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar R, Sahu SK, Kumar M, Jana K, Gupta P, Gupta UD, et al. MicroRNA 17-5p regulates autophagy in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages by targeting mcl-1 and STAT3. Cell Microbiol. 2016;18:679–91. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medina E, North RJ. Resistance ranking of some common inbred mouse strains to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and relationship to major histocompatibility complex haplotype and nramp1 genotype. Immunology. 1998;93:270–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franzblau SG, DeGroote MA, Cho SH, Andries K, Nuermberger E, Orme IM, et al. Comprehensive analysis of methods used for the evaluation of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2012;92:453–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irwin SM, Driver E, Lyon E, Schrupp C, Ryan G, Gonzalez-Juarrero M, et al. Presence of multiple lesion types with vastly different microenvironments in C3HeB/FeJ mice following aerosol infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:591–602. doi: 10.1242/dmm.019570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenthal IM, Tasneen R, Peloquin CA, Zhang M, Almeida D, Mdluli KE, et al. Dose-ranging comparison of rifampin and rifapentine in two pathologically distinct murine models of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4331–40. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00912-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irwin SM, Gruppo V, Brooks E, Gilliland J, Scherman M, Reichlen MJ, et al. Limited activity of clofazimine as a single drug in a mouse model of tuberculosis exhibiting caseous necrotic granulomas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4026–34. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02565-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanoix JP, Lenaerts AJ, Nuermberger EL. Heterogeneous disease progression and treatment response in a C3HeB/FeJ mouse model of tuberculosis. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8:603–10. doi: 10.1242/dmm.019513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Husain AA, Gupta UD, Gupta P, Nayak AR, Chandak NH, Daginawla HF, et al. Modelling of cerebral tuberculosis in BALB/c mice using clinical strain from patients with CNS tuberculosis infection. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145:833–9. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1930_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cardona PJ, Williams A. Experimental animal modelling for TB vaccine development. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;56:268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar G, Sharma N, Gupta P, Joshi B, Gupta UD, Cevc G, et al. Improved protection against tuberculosis after boosting the BCG-primed mice with subunit ag 85a delivered through intact skin with deformable vesicles. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016;82:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith CM, Proulx MK, Olive AJ, Laddy D, Mishra BB, Moss C, et al. Tuberculosis susceptibility and vaccine protection are independently controlled by host genotype. MBio. 2016;7(5) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01516-16. pii: e01516-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez L, Strbo N, Podack ER. Humanized mice: Novel model for studying mechanisms of human immune-based therapies. Immunol Res. 2013;57:326–34. doi: 10.1007/s12026-013-8471-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heuts F, Gavier-Widén D, Carow B, Juarez J, Wigzell H, Rottenberg ME, et al. CD4+ cell-dependent granuloma formation in humanized mice infected with mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6482–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219985110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nusbaum RJ, Calderon VE, Huante MB, Sutjita P, Vijayakumar S, Lancaster KL, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis in humanized mice infected with HIV-1. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21522. doi: 10.1038/srep21522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakamoto K. The pathology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Vet Pathol. 2012;49:423–39. doi: 10.1177/0300985811429313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dutta NK, Alsultan A, Gniadek TJ, Belchis DA, Pinn ML, Mdluli KE, et al. Potent rifamycin-sparing regimen cures guinea pig tuberculosis as rapidly as the standard regimen. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3910–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00761-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta NK, Illei PB, Peloquin CA, Pinn ML, Mdluli KE, Nuermberger EL, et al. Rifapentine is not more active than rifampin against chronic tuberculosis in guinea pigs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3726–31. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00500-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenaerts AJ, Hoff D, Aly S, Ehlers S, Andries K, Cantarero L, et al. Location of persisting mycobacteria in a guinea pig model of tuberculosis revealed by r207910. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3338–45. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00276-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dascher CC, Hiromatsu K, Xiong X, Morehouse C, Watts G, Liu G, et al. Immunization with a mycobacterial lipid vaccine improves pulmonary pathology in the guinea pig model of tuberculosis. Int Immunol. 2003;15:915–25. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guirado E, Gil O, Cáceres N, Singh M, Vilaplana C, Cardona PJ, et al. Induction of a specific strong polyantigenic cellular immune response after short-term chemotherapy controls bacillary reactivation in murine and guinea pig experimental models of tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1229–37. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00094-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cardona PJ. RUTI: A new chance to shorten the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2006;86:273–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu P, Jiang H, Li S, Lin Z, Jiang J. Determination of anti-tuberculosis drug concentration and distribution from sustained release microspheres in the vertebrae of a spinal tuberculosis rabbit model. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:200–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.23236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manabe YC, Dannenberg AM, Jr, Tyagi SK, Hatem CL, Yoder M, Woolwine SC. Different strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cause various spectrums of disease in the rabbit model of tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6004–11. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.6004-6011.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaplan GTL. Pulmonary tuberculosis in the rabbit. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Datta M, Via LE, Kamoun WS, Liu C, Chen W, Seano G, et al. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment normalizes tuberculosis granuloma vasculature and improves small molecule delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:1827–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424563112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kjellsson MC, Via LE, Goh A, Weiner D, Low KM, Kern S, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of the penetration of antituberculosis agents in rabbit pulmonary lesions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:446–57. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05208-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Via LE, Schimel D, Weiner DM, Dartois V, Dayao E, Cai Y, et al. Infection dynamics and response to chemotherapy in a rabbit model of tuberculosis using [(1)(8)F]2-fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4391–402. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00531-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin PL, Pawar S, Myers A, Pegu A, Fuhrman C, Reinhart TA, et al. Early events in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in cynomolgus macaques. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3790–803. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00064-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Via LE, Lin PL, Ray SM, Carrillo J, Allen SS, Eum SY, et al. Tuberculous granulomas are hypoxic in guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2333–40. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01515-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaushal D, Mehra S, Didier PJ, Lackner AA. The non-human primate model of tuberculosis. J Med Primatol. 2012;41:191–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2012.00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin PL, Rodgers M, Smith L, Bigbee M, Myers A, Bigbee C, et al. Quantitative comparison of active and latent tuberculosis in the cynomolgus macaque model. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4631–42. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00592-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White AG, Maiello P, Coleman MT, Tomko JA, Frye LJ, Scanga CA, et al. Analysis of 18FDG PET/CT imaging as a tool for studying Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and treatment in non-human primates. J Vis Exp. 2017;127 doi: 10.3791/56375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McLeay SC, Morrish GA, Kirkpatrick CM, Green B. The relationship between drug clearance and body size: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature published from 2000 to 2007. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51:319–30. doi: 10.2165/11598930-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin PL, Dartois V, Johnston PJ, Janssen C, Via L, Goodwin MB, et al. Metronidazole prevents reactivation of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14188–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121497109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verreck FAW, Tchilian EZ, Vervenne RAW, Sombroek CC, Kondova I, Eissen OA, et al. Variable BCG efficacy in rhesus populations: Pulmonary BCG provides protection where standard intra-dermal vaccination fails. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2017;104:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharpe S, White A, Gleeson F, McIntyre A, Smyth D, Clark S, et al. Ultra low dose aerosol challenge with Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to divergent outcomes in rhesus and cynomolgus macaques. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2016;96:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Traver D, Herbomel P, Patton EE, Murphey RD, Yoder JA, Litman GW, et al. The zebrafish as a model organism to study development of the immune system. Adv Immunol. 2003;81:253–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Renshaw SA, Trede NS. A model 450 million years in the making: Zebrafish and vertebrate immunity. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5:38–47. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stinear TP, Seemann T, Harrison PF, Jenkin GA, Davies JK, Johnson PD, et al. Insights from the complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium marinum on the evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 2008;18:729–41. doi: 10.1101/gr.075069.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swaim LE, Connolly LE, Volkman HE, Humbert O, Born DE, Ramakrishnan L, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection of adult zebrafish causes caseating granulomatous tuberculosis and is moderated by adaptive immunity. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6108–17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00887-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Myllymäki H, Bäuerlein CA, Rämet M. The zebrafish breathes new life into the study of tuberculosis. Front Immunol. 2016;7:196. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benard EL, van der Sar AM, Ellett F, Lieschke GJ, Spaink HP, Meijer AH, et al. Infection of zebrafish embryos with intracellular bacterial pathogens. J Vis Exp. 2012;61 doi: 10.3791/3781. pii: 3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takaki K, Davis JM, Winglee K, Ramakrishnan L. Evaluation of the pathogenesis and treatment of Mycobacterium marinum infection in zebrafish. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1114–24. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaufman CK, White RM, Zon L. Chemical genetic screening in the zebrafish embryo. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1422–32. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adams KN, Szumowski JD, Ramakrishnan L. Verapamil, and its metabolite norverapamil, inhibit macrophage-induced, bacterial efflux pump-mediated tolerance to multiple anti-tubercular drugs. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:456–66. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tobin DM, Roca FJ, Oh SF, McFarland R, Vickery TW, Ray JP, et al. Host genotype-specific therapies can optimize the inflammatory response to mycobacterial infections. Cell. 2012;148:434–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roca FJ, Ramakrishnan L. TNF dually mediates resistance and susceptibility to mycobacteria via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell. 2013;153:521–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oksanen KE, Halfpenny NJ, Sherwood E, Harjula SK, Hammarén MM, Ahava MJ, et al. An adult zebrafish model for preclinical tuberculosis vaccine development. Vaccine. 2013;31:5202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]