Abstract

Losing a much-awaited pregnancy and an unborn child, time and again is known to be a painful experience in recurrent miscarriage or pregnancy loss (RPL). Literature on psychological consequences of RPL is abundant. Nonetheless, application of psychological intervention in RPL remains to be an overlooked area. Using a repeated measures design and standardized psychological measures, this case study assessed the outcomes of mindfulness-based therapy administered with routine fertility treatment in a couple with the history of recurrent miscarriages and secondary infertility. Data analysis was done using clinically significant change and analysis of graphic trends. Psychotherapy helped the couple initiate a meaningful discourse with the stress following miscarriage, uncertainty of pregnancy, and fertility-related emotional struggles by mindfully transforming stressors into less painful experiences. Control studies on applications of such therapies are needed to provide definitive answers to “what works, for whom, when, and how,” with distressed patients experiencing RPL.

KEYWORDS: Case study, counseling, couple, emotional distress, infertility, mindfulness, psychotherapy, recurrent miscarriages

INTRODUCTION

Recurrent miscarriage or pregnancy loss (RPL) is experienced by couples when two or more miscarriages occur before the pregnancies reach 20 weeks.[1] It is known to be a distressing condition as several cases have uncertain etiology.[1] The psychological consequence and implications of repeated miscarriages are well acknowledged.[1] Studies have emphasized on the abortogenic effects of high stress on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, particularly during early gestation.[2] Evidences on psychoneuroimmunological causes behind RPL suggests that emotional grief, guilt, and distress contributes to alterations in cortisol, NK cell activity, CD3+, CD8+, CD56+, T cells, Th1 and Th2 helper cells, uterine receptivity, and progesterone-induced blocking factor mechanisms, thus dwindling the fate of pregnancy.[1,3,4] Research substantiates that depression, state or trait anxiety, personal and social stress, grief, relational conflict, poor psychological adjustment, and marital distress are consequences of RPL.[5] In addition, 41% of women experience high stress and affective disturbances in RPL and these rates are comparable to a typical psychiatric population.[6,7] Evidence-based guidelines for RPL recommend couple-based psychological care for patients as psychological support is known to cause two-to-four-fold reduction in miscarriage and improved live birth rates.[8]

While there are some evidences in the literature on the benefits of psychotherapy in RPL,[5,9,10] no such research has been reported from the Indian context. This case report is the first of its kind which makes a new attempt to document the outcomes of structured psychological intervention administered on a couple experiencing RPL in the fertility clinic setup at a time when they were undergoing cycles of intrauterine insemination.

CASE REPORT

Background fertility history

The index couple was a 38-year-old male (with mild oligospermia) and 32-year-old female (with Poly Cystic Ovarian Disease) belonging to the upper middle class, residing in a nuclear urban family setup, diagnosed with secondary infertility with secondary infertility and RPL. The couple were married and trying to conceive since 8 years. The couple had an obstetric history of two spontaneous conceptions in 2009 and 2011, and one in vitro fertilization (IVF) conception in 2014, all of which were followed by reduced cardiac activity in the fetus and spontaneous miscarriages within 6 weeks of gestation. They were undergoing assisted reproductive treatments for the past 2 years and had a history of one abandoned IVF cycle (poor response) and one successful IVF (antagonist protocol) in 2013. Persistent genetic anomalies identified (factor V Leiden Mutation) were identified as a possible cause leading to RPL. At present, after their detailed investigations, the couple was keen for IUI. The fertility experts planned the couple for treatments with heparin and aspirin in view of RPL. In addition, owing to high stress in her, she was referred by infertility staff for the study. Ethical guidelines (such as institutional approval, written informed consent, privacy of records, confidentiality, the right to withdraw from the study, and finally the use of data strictly for research purpose and benefits of others with RPL) were maintained throughout the study. It was a part of preliminary work for a WHO-registered randomized controlled trial (RCT) on effectiveness of psychotherapy in infertility (REF/2014/05/006991).

Detailed psychological consultation

The couple were seen by a Licensed Clinical Psychologist who was a trained personnel (in basic aspects of infertility, ART and reproductive psychology), functioning as a full-time doctoral scholar at the study site. In intake interview with the wife, her symptoms were suggestive of adjustment disorder (with gradual onset for the past 1.5 years), characterized by mixed affective disturbances, high-infertility-related distress-related coping inabilities, sleep disturbances, labile mood, GI disturbances, tension headaches, palpitations, ruminations, worries, occasional crying spells, bodily preoccupation, and guilt that peaked during premenstrual and menstrual time. The husband's history revealed nonpervasive and subclinical depressive symptoms. His history was suggestive of mild-moderate fertility-related distress and maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance and disengagement. The couple's history was not suggestive of morbid grief, marital discord, or other psychological morbidity.

Psychological assessments

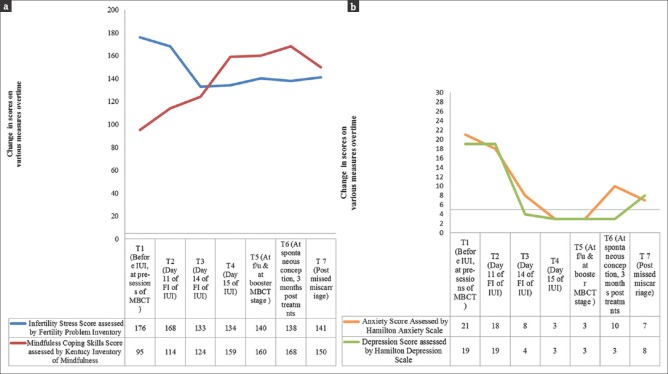

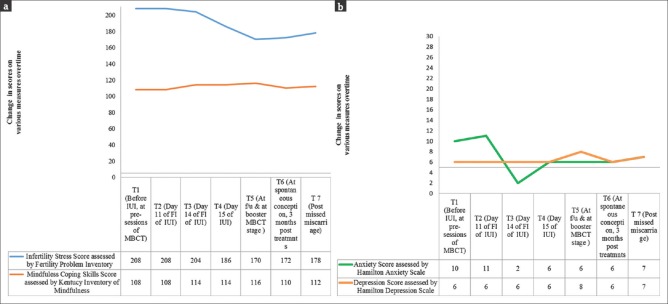

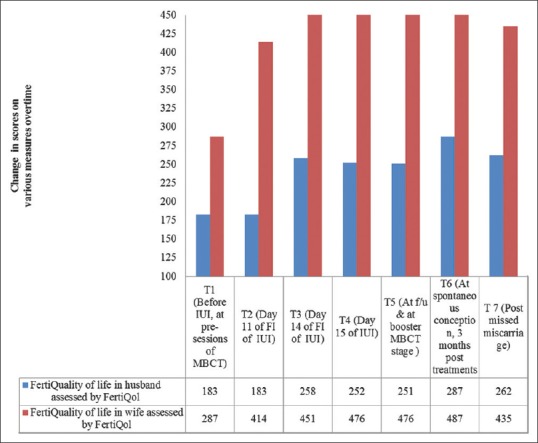

To evaluate the outcomes of psychotherapy, the couple was further assessed using a repeated measures design, using the scales those scores have been summarized in Figures 1–3.

Figure 1.

(a) The change in scores on infertility specific stress and mindfulness coping for the wife at different time points. (b) The change in scores on on anxiety and depression for the wife at different time points

Figure 3.

The change in scores on fertility quality of life scores for husband and wife at different time points

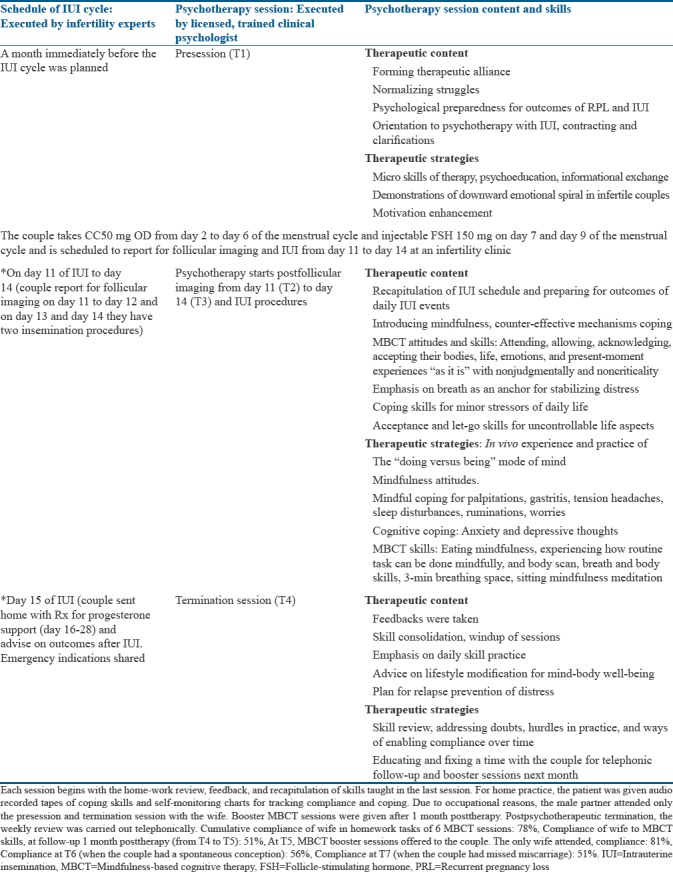

Psychotherapy module

Modified mindfulness-based cognitive was administered on the couple in 6-daily 90-min session structure with predesignated daily homework tasks, which they underwent along with routine-assisted conception treatments. The details of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) are summarized in Table 1. Change on the outcome measures was assessed before (T1) and after the intervention (T2, T3, and T4), at booster MBCT sessions done for 1 month followed by the last IUI (T5), at spontaneous conception (confirmed by transvaginal scan and blood tests) after 3 months IUI pregnancy (T6), and at missed miscarriage stage (T7).

Table 1.

Details of conduct of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with intrauterine insemination

Data analysis

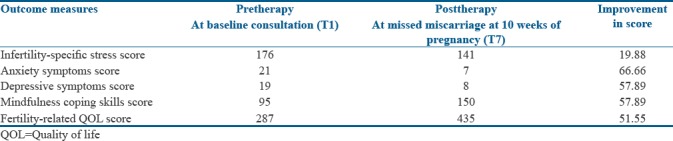

Visual analysis of graphic trends [Figures 1–3] and clinically significant therapeutic changes (50% and above from T1 to T7) for wife's scores were calculated [Table 2] for estimating effect size of psychotherapy using formula given by Blanchard and Schwartz, 1998 (prescore − postscore/prescore × 100).

Table 2.

Clinically significant change in wife on various psychological measures

RESULTS

Visual analysis of graphic trends in data was seen, at various time-points from pre-post MBCT. Outcomes in wife [Figure 1a and b] suggest minor fluctuations in infertility stress experienced by her. However, as coping skills gradually increased, she experienced a stable improvement. Anxiety and depression reduced and remained below the critical cutoff points in wife and husband. These scores remained low in stressful events and stressors (such as a failure of IUI cycle, conception stress, and miscarriage) faced by the couple in the months that followed therapy. Outcomes in husband [Figure 2a and b] suggest that although he attended only two sessions, his scores on stress, anxiety, and depression reduced. This suggests the dyadic benefits of therapy even if one partner opts for it. Couple's feedback revealed that each partner mutually experienced mind–body well-being posttherapy reflected in improved quality of life scores [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

(a) The change in scores on infertility specific stress and mindfulness coping for the husband at different time points. (b) The change in scores on anxiety and depression for the husband at different time points

DISCUSSION

Couples with RPL are known to experience fluctuating patterns of unresolved grief, series of losses, and associated emotional pain. Evidence from this study is in-line with other studies[9,10] which urge that brief psychotherapy may be useful in the patients with RPL, as it helps in meaning-based coping. A steady improvement in psychological symptoms in this study suggested a possible enhancement in the ability of the couple to recoil back to life after a miscarriage, readjust, and move toward meaningful resolution, growth, and fulfillment of other life goals. The strengths of modified MBCT module were its good internal validity, brevity, focus, and application of limited core MBCT skills to achieve the desired short-term mental health goals. In addition, this study was a collaborative team effort of infertility experts and mental health experts and combined evidence-based elements such as patients' psychoeducation, fertility education, lifestyle modification, knowledge of their medical status and planned treatment goals, and mind and body coping skills to psychologically preparing the patients for outcomes of RPL and subfertility. Finally, therapy helped in creating a sense of controllability and containment as the couple was able to cope with the positive, predictable aspects, and the unpredictable negative aspects of RPL. Even in the antenatal times and at miscarriage, a mindful approach was enabled in liberating patients from their past and future worries. Grounded in elements of positive psychological change, MBCT helped the couple create a realistic hope, meaning, courage, and optimism toward life in the long term, both in terms of fertility and otherwise. Limitations of this study are its short-term focus and brief follow-up period, biases due to reactivity, restricted external validity, and errors such as autocorrelation due to which it needs be improved in its design. In addition, marginal changes in infertility stress were observed and thus to facilitate long-term psychological adaptation continuous weekly therapy is needed. In closing, supplementary research with controlled trials and adequate sample size is required in this overlooked area to provide us with authoritative evidences to support the validity of present work. The broader implementation of this study is that it became a part of pilot work for a larger doctoral project that provided us a basis for designing RCT on effectiveness of psychotherapy in infertility.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Our deepest gratitude to the couple for their participation and Dr. BS Patel for his assistance in the drafting and editing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: A committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:1103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W, Newell-Price J, Jones GL, Ledger WL, Li TC. Relationship between psychological stress and recurrent miscarriage. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25:180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arck PC. Stress and pregnancy loss: Role of immune mediators, hormones and neurotransmitters. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2001;46:117–23. doi: 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2001.460201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faust Z, Laskarin G, Rukavina D, Szekeres-Bartho J. Progesterone-induced blocking factor inhibits degranulation of natural killer cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1999;42:71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carp HJ, editor. Recurrent Pregnancy Loss: Causes, Controversies, and Treatment. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Taylor and Francis group; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolte AM, Olsen LR, Mikkelsen EM, Christiansen OB, Nielsen HS. Depression and emotional stress is highly prevalent among women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:777–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig M, Tata P, Regan L. Psychiatric morbidity among patients with recurrent miscarriage. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;23:157–64. doi: 10.3109/01674820209074668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kutteh WH. Recurrent pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:xi–xiii. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakano Y, Akechi T, Furukawa TA, Sugiura-Ogasawara M. Cognitive behavior therapy for psychological distress in patients with recurrent miscarriage. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2013;6:37–43. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S44327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Séjourné N, Callahan S, Chabrol H. The utility of a psychological intervention for coping with spontaneous abortion. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2010;28:287–96. [Google Scholar]