SUMMARY

Since the 1980s, Australia’s mass-media campaigns promoting skin cancer awareness, namely skin cancer-preventative behaviors and early detection, have targeted the general community as well as high-risk groups, including outdoor workers, schoolchildren and youths. During that time, campaigns have evolved in tone and method of delivery. Their messages are today accompanied by policies, supportive environments such as shade and access to quality sun-protection products governed by national standards. Early detection of skin cancer has been the other aim of these campaigns, and recent downturns in incidence rates, especially in the young, and the shift to mostly thin melanomas at diagnosis in Australia, may partly reflect some campaign success. However, sustained efforts are required for long-lasting skin cancer control.

KEYWORDS: Australia, awareness, campaigns, early detection, prevention, skin cancer

Practice points.

Australia has the highest reported rates of skin cancer in the world, and skin cancer is the most costly of all cancers to the Australian health system.

The most common types of skin cancer (i.e., basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma) are caused by ultraviolet radiation, mostly from sun exposure, but also from indoor tanning devices.

Reduction in ultraviolet radiation exposure is the most direct and effective way to reduce the incidence and mortality rates of skin cancer in the general population (i.e., primary prevention).

For more than 30 years, Australia has provided leadership and innovation in raising skin cancer awareness with regards to both prevention and early detection through mass-media campaigns.

These campaigns have evolved with respect to the tone and content of their messages and with respect to their target audiences in order to reach both the general community and hard-to-reach groups.

Media delivery methods have also evolved in order to keep pace with current media trends, today including social media and smartphone apps.

Early detection and treatment are the other important components of skin cancer control, particularly with regards to reducing morbidity and mortality in the short term.

Specifically educating clinicians and the public about the appearance and behavior of early skin cancer, especially melanoma, is an important aspect of awareness.

Australia has the highest reported skin cancer rates in the world [1], and thus the treatment of skin cancers represents a major public health burden. The two most common types of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, with estimated national incidence rates in 2002 of approximately 880 and 390 per 100,000 per year, respectively [2], but with relatively low mortality. The third most common skin cancer is cutaneous melanoma, with annual incidence estimates in Australia of approximately 62 per 100,000 in men and 40 per 100,000 in women in 2012, resulting in approximately 12,500 new cases [3]. In 2010, melanoma mortality rates were approximately nine and four per 100,000 in men and women, respectively, resulting in 1452 deaths [3]. Of these three types, melanoma is the most serious because it causes death if diagnosed late and it affects all age groups, including adolescents. Indeed, melanoma is currently the most common cancer in young adults (aged 15–29 years) in Australia [4]. The cost to the Australian health system of skin cancer treatment is thus substantial, being more costly than any other cancer [5].

Ultraviolet radiation (UVR), mostly from sun exposure (but also from indoor tanning devices since the 1970s), causes all three main types of skin cancer [6]. Reduction in UVR exposure is therefore the most direct and effective way to reduce incidence and mortality rates in the general population. Achieving long-lasting reduction through primary prevention is challenging, however, and requires sustained public health efforts in order to uphold sun protection as a matter of importance and shift community attitudes and behaviors away from the active pursuit of suntanned skin. Early detection and early treatment are the other important components of skin cancer control, particularly with regards to reducing morbidity and mortality in the short term. Therefore, alongside skin cancer-preventative behavior, the specific education of clinicians and the public about the appearance and behavior of early skin cancer, especially melanoma, is the other most important aspect of skin cancer awareness.

Regarding primary prevention as the first aspect, Australia has a long history of mass-media campaigns aimed at increasing the public’s knowledge about the link between sun exposure and skin cancer. These campaigns have helped to create a community that today is generally aware about the seriousness of skin cancer and the need for the active avoidance of sun exposure in order to prevent it. Skin cancer awareness campaigns in Australia have been conducted predominantly under the umbrella term ‘SunSmart’, which is licensed to each state and territory Cancer Council. The Australian government has also participated in the conduct of such awareness campaigns. The primary aim of this article is to review the evolution of Australian campaigns since the 1970s. These have been tabulated comprehensively (Supplementary Table 1), and the most relevant have been highlighted for review. In addition, we also briefly evaluate recent trends in sun exposure and skin cancer incidence, which partly reflect the effectiveness of these campaigns, alongside other sustainable educational, organizational and environmental strategies in Australia.

Programs & sponsorship

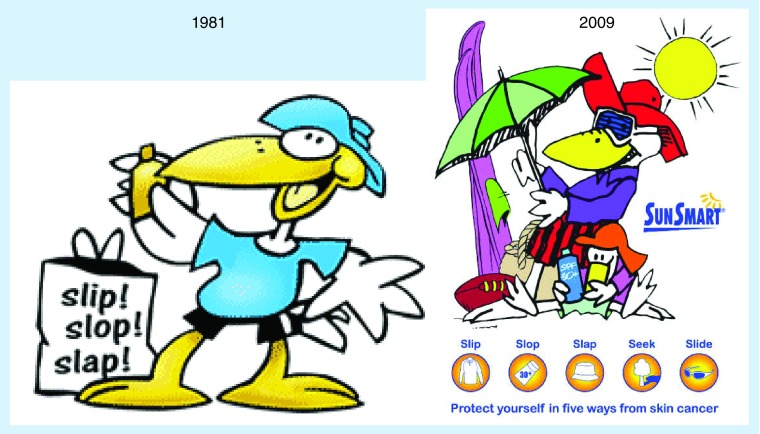

Although it was apparent that overexposure to UVR was a major risk factor for melanoma as early asthe late 1950s [7,8], melanoma rates had nearly doubled between then and the early 1980s in Australia [9,10]. Tanning was considered highly socially desirable and contributed further to the excess sun exposure that was experienced through the famous Australian outdoor lifestyle. Recognizing that Australians needed to change their attitudes regarding sun exposure and tanning in order to arrest the skin cancer ‘epidemic’, the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria, a not-for-profit agency, ran the first skin cancer prevention television advertisements in 1977 and 1978. In 1981, following on from an original campaign undertaken by the Queensland Cancer Fund, namely ‘Slip it on, Slap it on, Shove it on,’ the Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria launched what was to become one of the most popular health campaigns in Australia’s history: ‘Slip! Slop! Slap!’ (‘slip’ on protective clothing, ‘slop’ on sunscreen and ‘slap’ on a hat; Supplementary Table 1 & Appendix A). This seminal campaign is regarded as the cornerstone of Australia’s early efforts to prevent skin cancer.

• SunSmart

In 1988, building on the widespread uptake of the ‘Slip! Slop! Slap!’ campaign and with financial assistance from the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, the ‘SunSmart’ program was established in Victoria as an official coordinated skin cancer control program for Australia (Supplementary Table 1) [11]. Based on social–cognitive theories of behavior change, the SunSmart campaign has since sought to raise awareness both of skin cancer and of the crucial link with UVR exposure from either sunlight or artificial tanning devices [11]. It has aimed to strengthen people’s capacity for successful sun protection in various community and social settings where UVR exposure is encountered, so that protective behavior changes are initiated. By integrating research and evaluation into campaign planning and implementation, SunSmart’s messages aimed to be innovative and engaging, challenging social and cultural norms (Supplementary Table 1) [11].

• State & territory Cancer Councils

Cancer Council Australia is a national, not-for-profit agency that promotes cancer control policies in Australia [12] and includes eight entities that operate in individual states (Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia) and territories (Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory). Currently, the SunSmart campaign brand is operated by these respective Australian state and territory Cancer Councils who employ the same theoretical framework, but tailor their SunSmart campaigns to meet their own communities’ needs. For example, while standard SunSmart policy and procedure guidelines for reducing UVR exposure in the workplace have been developed [13], state and territory Cancer Councils assist regional organizations in their practical implementation and adapt them as appropriate to meet local legislative requirements. Today’s funding arrangements differ by state and territory in Australia, with some receiving funding assistance from relevant state and territory governments.

• Federal & state governments

As part of the Australian government’s ‘Strengthening Cancer Care’ initiative in 2005, AUD$5.5 million was committed over 2 years in order to fund a national campaign to educate Australians about the importance of sun protection for the prevention of skin cancer (Supplementary Table 1) [14].

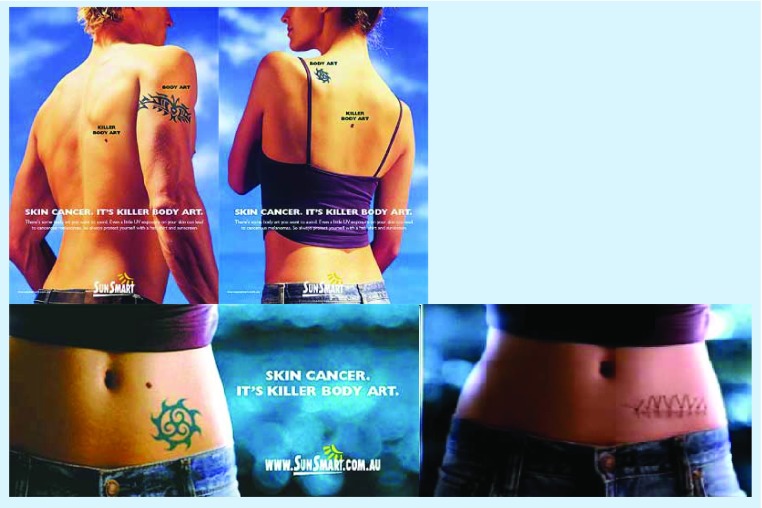

In order to create their skin cancer awareness campaigns, with regards to prevention, the Australian government first reviewed the successes and failures of previous campaigns in Australia, including the conduct of focus groups, so as to explore people’s responses to three specific campaigns: ‘Slip! Slop! Slap!’; ‘Tattoo – Killer Body Art’ and ‘How to Remove a Skin Cancer’ (Appendix). Advice from state and territory Cancer Council representatives with campaign expertise was sought and a cross-section of community groups was surveyed in order to identify the optimal target audience for the planned campaigns. In addition, the Australian government drew on the results of the first national survey of sun protection behaviors and attitudes – the National Sun Survey [15,16], conducted in 2003–2004 with government cofunding – in planning the national campaign strategy.

It emerged from the focus groups that television advertising was the most effective way to deliver health messages in Australia. Developmental research also suggested that the theme should be ‘prevention’ and the primary target audience should be teenagers (13–17-year olds) and young adults (18–24-year olds), as they continued to be the least likely age groups to modify their behaviors and attitudes towards sun exposure, although the campaign would be designed to raise awareness across all age groups. The secondary target group was to be the parents of children aged up to 17 years in order to emphasize the importance of parental influence on children’s sun-protective behaviors and attitudes. The Australian government-funded campaigns were first launched in the summer of 2006–2007 and were disseminated each summer thereafter until 2009–2010 (Supplementary Table 1).

• Other sponsorship

Individual people whose lives have been affected substantially by skin cancer have also been drivers of skin cancer awareness campaigns in Australia. One of the best known is Clare Oliver, a young woman from Melbourne, who was 26 years of age when she died of melanoma. She attributed her fatal disease to her regular use of artificial tanning devices and spent the last weeks of her life raising awareness against their dangers. Her television interviews, such as her ‘dying-for-a-tan’ interview [17], captured community attention and became the basis of the ‘Clare Oliver Campaign’, initiated and funded by Cancer Council Australia and SunSmart in collaboration with the Clare Oliver Foundation [18]. Footage from Clare Oliver’s news interviews was used in order to develop a television advertisement campaign called ‘No tan is worth dying for’ so as to continue her fight to raise awareness against the dangers of tanning beds. Other melanoma survivors kept her legacy alive, sponsoring subsequent campaigns, such as the SUNBEDban.com campaign [19], advocating the prohibition of sunbeds in Australia, as well as raising money to support melanoma research.

Evolution of prevention campaign messages & target groups

• 1980s to early 1990s

The tone of skin cancer prevention campaigns that started in the early 1980s was light-hearted. The original ‘Slip! Slop! Slap!’ television commercial featured Sid, an animated seagull, and a catchy jingle to encourage Australians to practice sun protection. Sid and his family also encouraged people to ‘Pick up a spade and plant some shade’ so as to create a sun-safe general environment (Supplementary Table 1). These messages were meant to be light and positive about sun protection, while still encouraging enjoyment of an outdoor lifestyle. In keeping with this approach and to combat the attitude that sun-protective clothing was unfashionable, some of the other campaigns that have been run in Australia included the ‘You can leave your hat on’ campaign and, similarly, the ‘Right Side’ campaign to promote seeking shade and covering up by staying on the right side of the ‘sun protection line’ (Supplementary Table 1).

• Late 1990s to early 2000s

By the mid-1990s, skin cancer awareness was growing, but compliance with sun-protection advice remained suboptimal. The tone of campaigns thus began to change, becoming more serious and depicting the gravity of skin cancer. The ‘How to remove a skin cancer’ (1996–1998) campaign was the first graphic advertisement showing close-ups of the surgical excision of skin cancer, while the ‘Time Bomb’ campaign (2000–2001) promoted skin cancer awareness by telling Australians that getting sun burnt, even mildly, is similar to putting a ‘time bomb’ under the skin, depicting it ‘exploding’ into cancer on different parts of the body. The ‘Tattoo – Killer Body Art’ (2003–2005) campaign highlighted the unattractive scars left after melanoma surgery, showing the opposite effect of seeking an ‘attractive, healthy’ tan. Teenagers were another focus in this decade, with fun campaigns such as the ‘Whoops forgot to be SunSmart’ man, showing a fictitious character with melting skin who forgot to be ‘SunSmart’, and ‘A safe suntan? Pigs might fly!’ campaign that was played on radio stations.

• Mid-2000s to early 2010s

In summer 2006–2007, when the Australian government launched their multimedia skin cancer awareness campaign, a themed message was ‘Protect Yourself in Five Ways’, aimed at educating Australians on the importance of protecting themselves in multiple ways from the sun (shirt, sunscreen, hat, shade and sunglasses) in order to prevent skin cancer (and eye damage). Television commercials remained grim, showing a wide surgical excision of a melanoma in a young woman and the surgeon’s reminder that skin cancer can kill. Printed advertisements also included graphic images, with slogans such as ‘Not everyone with melanoma dies, some just go through hell’ (raising awareness of the possible death after diagnosis and the treatment of melanoma) and ‘Don’t let your time in the sun catch up with you’ (raising awareness of the harm of cumulative sunlight exposure). All national print media campaigns highlighted melanoma as the most common form of life-threatening cancer in young Australians aged 15–24 years.

Clare Oliver’s personal campaign also took place in the mid-2000s. This was followed by the ‘Dark Side of Tanning’ campaign [20], first released in summer 2007–2008 and was still aired in 2013 (Supplementary Table 1), which has continued the fight against the perception of a safe or healthy tan: ‘There’s nothing healthy about a tan’. Another campaign that personalized the ‘beware of skin cancer’ message was the ‘Wes Bonny Testimonial’ video released in the summer of 2010–2011 and shown on television and in movie theaters [21]. The testimonial recounted the true story of young Wes Bonny who had enjoyed the outdoor Australian lifestyle, visiting the beach and playing sports with his friends, but perhaps not always with full sun protection. He died of melanoma at 26 years of age. The campaign tagline of ‘You know what to do. Do it!’ aimed to emphasize the importance of putting knowledge about sun protection into action in order to prevent the tragic loss of young life from skin cancer (Supplementary Table 1).

Over the last two decades, while many campaigns have been designed to appeal to the general public in order to change and improve their sun protection behaviors and attitudes, others have been targeted at certain groups who may be less likely to heed advice about skin cancer risks or who are at above-average risk of developing skin cancer. For example, the ‘Tattoo – Killer Body Art’ and ‘Every Fashion has its Accessories’ campaigns were designed to appeal to young women with regards to their pro-tanning attitudes, and the Farmers’ campaign (‘Protect your farm’s most important asset. You!’) targeted farmers and rural outdoor workers who receive high occupational sun exposure. A recent campaign (3AW) in Victoria was aimed at men because they are less likely to protect themselves or to visit a physician than women and because men’s incidence rates have continued to rise, with them having a higher likelihood of fatal melanoma than women (Supplementary Table 1).

• Evolution of campaign delivery methods

With growing community access to the internet over the last decade, delivery of media campaigns via television advertisements, radio announcements and print media (e.g., posters and billboards, among other methods) has expanded to include delivery on websites by many agencies, including SunSmart [22] and state and territory governments. For example, the Queensland government’s ‘sun safety’ internet page [23] provides very detailed information on sun protection, including explaining the ultraviolet factor protection ratings of clothing, as well as tips on how to choose and apply sunscreen. It also provides advice regarding achieving optimal sun protection for people of different ages and in different environments (i.e., built-up or natural). In addition, so as to more effectively reach adolescents and young adult groups who may be less influenced by traditional media campaigns, delivery by social media is increasing, with campaigns that are conducted on Facebook [24] and via Twitter [25]. Smartphone apps have been designed and are widely used in order to increase UVR awareness, such as those available through the Queensland government: Queensland Health [26] and SunSmart [27]. Moreover, skin cancer awareness efforts with regards to daily sun protection are included in weather reports (e.g., ultraviolet index alerts issued by the Bureau of Meteorology) and in outdoor public recreational areas, where, for example, under the Sun Sound campaign, a catchy jingle is broadcast at intervals in order to remind people to protect themselves (Supplementary Table 1) [28].

In order to help facilitate the sustainability of skin cancer awareness campaigns, state and territory Cancer Councils have encouraged educational, organizational and environmental strategies, such as policies, standards, access to sun protection products and outdoor shade designs. Uptake and propagation ranges from childcare centers and primary- and secondary-school settings to occupational settings (e.g., local government authorities and private workplaces) to sport and leisure organizations. The National SunSmart Schools Program [29], developed by Cancer Council Victoria in 1994 and launched around Australia in 1998, is one such program that employs sun protection policies and procedures aimed at reducing the amount of UVR exposure received in a vulnerable period of life [30]. The SunSmart School Program [31] is a policy-based program requiring schools to have a comprehensive SunSmart policy covering the expectations of students, staff and the wider school community. It covers personal protection as well as the environmental adaption of the school’s ground so as to support shade. In order to support schools, the program also provides a number of free curriculum resources, such as ready-made whiteboard lessons and supportive awareness tools to help teach SunSmart messages during school hours. For the workplace, state and territory Cancer Councils provide professional services and resources in order to assist employers and employees to reduce their sun exposure [13]. For example, a project in Western Australia aims to reduce work-related sun damage and workers’ compensation costs by highlighting to employers the risks of such claims and providing the scope for implementing policies and procedures to protect workers from overexposure [32,33]. Ongoing face-to-face educational workshops have helped professional organizations in general to develop and implement sun-protection plans, and since 2002, outdoor workers have been able to receive a tax deduction on sun-protective wear, including protective clothing, hats, sunglasses and sunscreens. State and territory Cancer Councils also market affordable and accessible sun protection merchandise, such as protective clothing for outdoor sporting and leisure activities, particularly full body Lycra swimwear for children. There is also the novel fashion initiative supported by Cancer Council Queensland, whereby fashion design students, as part of their undergraduate curriculum, are taught to incorporate sun-safe elements into their designs, combining elements of environmental adaptations for the body with fashion concepts of modesty [34]. This work in personal protection is supported by advocacy and participation in the development of government standards covering a range of issues, from sunscreen testing to UVR protection factor ratings on clothing.

• Early detection

While mass-media campaigns have focused on prevention messages, national, state and territory Cancer Councils have long invested in print resources in order to educate the public about the early detection of skin cancer so as to increase the chance of curative treatment. A forerunner of these early detection campaigns was the Queensland Melanoma Project [35], which emphasized (mostly to clinicians) that melanoma could be cured by surgery if recognized at an early biological stage. The project called for professional and public education to achieve control of melanoma, and this is the tradition that has been carried on by Cancer Councils as well as professional training bodies. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Cancer Councils often conducted ‘skin spot clinics’ in public places such as beaches, setting up mini-diagnostic clinics and referring patients to their general practitioner for appropriate follow-up. More recently, a range of educational programs was also conducted, such as Cancer Council New South Wales’s ‘Strip, Search, and Save’ program (later adapted by Cancer Council Queensland [36]) to encourage men and women over 50 years of age to perform full-body skin examinations for lesions suspicious of being skin cancers, especially melanomas, and to seek treatment. State and territory Cancer Councils today employ an array of website resources in order to educate the community on skin cancer facts and figures (e.g., incidence and mortality rates and risk factors) in order to supplement information about skin self-examination. In the ‘How to spot the difference’ program, the detailed appearance of benign lesions and skin cancers are transmitted by printed cards and charts or via a PowerPoint presentation on Cancer Council websites in order to inform people about the distinguishing features of malignant skin lesions. In addition, Cancer Council websites provide links to medical professional bodies in order to assist people with finding doctors (without recommending individual doctors’ names) who are qualified to diagnose and treat skin cancers in their region of residence. The patient-support group Melanoma Patients Australia [37] also provides information on early detection and treatment of melanoma on their website.

General evaluation of campaign outcomes

Recent trends in skin cancer in Australia and surveys of community sun exposure (tanning and sunburn rates), as well as relevant policy measures, can all serve as broad indicators in the evaluation of campaign successes.

• Trends in skin cancer incidence

Skin cancer incidence rates have been gradually plateauing after decades of increase [2,38], and from approximately the mid-1990s, melanoma incidence rates have been decreasing in the youngest cohorts of 15–24-year olds [39,40].

• Sun exposure & protection surveys

Beginning in 1987, Cancer Council Victoria (then Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria) began monitoring community responses to campaign messages by conducting household surveys of tanning behavior, sunburn prevalence and sun-protection behaviors [41]. Three national surveys of Australian adolescents and adults conducted in the context of campaign activity from 2003–2011 supported a favorable change in attitudes toward tanning, with the proportion of adolescents and adults preferring a tan decreasing from 60 and 39% in 2003–2004 to 45 and 27% in 2010–2011, respectively, as well as a decline in the prevalence of sunburns by 4 and 5%, respectively, although no significant increases in the adoption of sun-protection behaviors were observed [42]. In Queensland, recent surveys in 2009 and 2010 of adults over 18 years of age showed that approximately 13% of men and 8% of women still reported getting sunburnt on the previous weekend, and that sunburn rates were highest by far in young men [43].

• Trends in skin surveillance

With regards to early detection of melanoma, there have been trends towards decreased thickness of incident primary melanomas in Australia, reflecting increasing rates of early detection [38,44]. In addition, the incidence rates of very early noninvasive melanoma have been climbing for a decade [38], while mortality rates have held steady. Taken together, these further suggest high rates of early detection of curable disease due to increasing skin cancer awareness.

• Sunbed regulation

In response to Clare Oliver’s seminal campaigns to raise awareness of the dangers of indoor tanning beds and artificial UVR, as well as subsequent private and public campaigns, use of tanning devices is now subject to regulation throughout Australia, and six of the eight Australian state and territory governments have announced an impending ban on solaria [45], with a total ban of tanning devices forecast in the next few years [46].

• Cost–effectiveness

It has been estimated that SunSmart has been responsible for preventing 103,000 skin cancers (9000 melanomas and 94,000 keratinocyte cancers) and 1000 deaths due to skin cancer in Victoria from 1988 to 2003 [47]. There has been estimated financial gain of AUD$2.60 for every dollar that historically has been invested in the SunSmart program. Investment in a national skin cancer prevention program is therefore beneficial for the Australian population and its health system. Over the next 20 years, investment in an upgraded, ongoing national SunSmart program could result in 20,000 fewer melanoma cases and 49,000 fewer keratinocyte cancers in Australia and save more than AUD$270 million in healthcare costs [47].

Conclusion

For more than 30 years, Australia has provided leadership and innovation in its skin cancer awareness campaigns. Broad indicators suggest that both primary prevention and early detection campaigns, alongside supporting policies, environmental changes and the availability of high-quality sun-protection products, have been beneficial in helping to slow, and in the young even reverse, the trends of increasing incidence and morbidity that characterized the second half of the 20th century in Australia. Future skin cancer prevention and control programs face the challenges of maintaining continued investment by governments and other bodies and of resolving conflicting issues that arise and threaten the acceptance of sun-protective behaviors.

Future perspective

Despite evidence that Australians have a heightened awareness of skin cancer and the need for preventative behaviors, the proportion putting their knowledge into action in recent years has not been optimal [42]. This may be partly attributed to other emerging health concerns, leading to health advice that conflicts with advice about sun avoidance. These concerns include the postulated benefits of vitamin D (normally gained through mild sun exposure) [48] and, to combat rising rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, the need for physical activity (which is mostly outdoors) [49]. Future campaigns therefore need to deliver clear messages that carefully balance advice about sun protection without compromising evidence-based advice for general good health [49]. In addition, bringing about long-lasting change in the behaviors and attitudes of adolescents will continue to be a challenge for future campaigns. Increasing engagement of this age group with the use of relevant social media campaigns will be important both because of adolescents’ vulnerability to the harmful long-term effects of excessive sun exposure and ultimately skin cancer [30] and because influencing adolescents’ behaviors into adult life is central to achieving durable change in the present culture of sun exposure. Ongoing evaluation programs built into future campaigns, including monitoring of protective behaviors and of skin cancer-related outcomes across all age groups, remains essential.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank L Baldwin, Head of Programs at Cancer Council Queensland, and J Makin, from Cancer Council Victoria, for reviewing the manuscript and providing very helpful comments. The authors also thank the following people for their contributions that ensured the accuracy of the enclosed Supplementary Table 1: H Jenkins (Cancer Council Australia), L Imbriano (Cancer Council Northern Territory), I Brozek (Cancer Council New South Wales), V Rocks (Cancer Council New South Wales), M Strickland (Cancer Council Western Australia), J Rayner (Cancer Council South Australia) and D Wild (Cancer Council Australian Capital Territory).

Appendix

Figure 1A. . Sid the Seagull.

Reproduced with permission from Cancer Council Victoria.

Figure 1B. . ‘Tattoo – Killer Body Art’.

Figure 1C. . ‘How to remove a skin cancer’.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

MR Iannacone was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Program Grant (no. 552429). AC Green has received financial support in the past from L’Oreal Recherche for a research project. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest

- 1.Lomas A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012;166(5):1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staples M, Marks R, Giles G. Trends in the incidence of non-melanocytic skin cancer (NMSC) treated in Australia 1985–1995: are primary prevention programs starting to have an effect? Int. J. Cancer. 1998;78(2):144–148. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981005)78:2<144::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • One of first papers to report the stabilizing skin cancer incidence rates in younger adults in Australia.

- 3.Cancer in Australia: an overview, 2012. Cancer Series no. 74. Cat. No. CAN 70. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Australia: 2012. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Australiasian Association of Cancer Registries. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults in Australia. Cancer Series no. 62. Cat. No. CAN 59. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Australia: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fransen M, Karahalios A, Sharma N, English DR, Giles GG, Sinclair RD. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2012;197(10):565–568. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Ghissassi F, Baan R, Straif K, et al. A review of human carcinogens – part D: radiation. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(8):751–752. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holman CD, James IR, Gattey PH, Armstrong BK. An analysis of trends in mortality from malignant melanoma of the skin in Australia. Int. J. Cancer. 1980;26(6):703–709. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lancaster HO, Nelson J. Sunlight as a cause of melanoma; a clinical survey. Med. J. Aust. 1957;44(14):452–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little JH, Holt J, Davis N. Changing epidemiology of malignant melanoma in Queensland. Med. J. Aust. 1980;1(2):66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy WH, Martyn AL, Roberts G, Dobson AJ. Melanoma in New South Wales 1970–1976. Confirmation of increased incidence. Med. J. Aust. 1980;2(3):137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montague M, Borland R, Sinclair C. Slip! Slop! Slap! and SunSmart, 1980–2000: Skin cancer control and 20 years of population-based campaigning. Health Educ. Behav. 2001;28(3):290–305. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Comprehensive description of the development of Australian sun-protection programs up until 2000.

- 12.Cancer Council Australia. History. http://web.archive.org/web/20130602053853/http://www.cancer.org.au/about-us/history.html

- 13.Cancer Council Australia. Sun protection in the workplace. www.cancer.org.au/preventing-cancer/sun-protection/sun-protection-in-the-workplace.html

- 14.Australian Government Department of Health. National Skin Cancer Awareness Campaign. www.skincancer.gov.au

- 15.Bowles KA, Dobbinson S, Wakefield M. The Commonwealth Cancer Strategies Group and The Cancer Council Australia. Centre for Behavioural Research in cancer, The Cancer Council Victoria; Australia: 2005. Sun protection and sunburn incidence of Australian adults: summer 2003–2004. Prepared for. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobbinson S, Bowles KA, Fairthorne A, Sambell N, Wakefield M. The Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing and The Cancer Council Australia. Centre for Behavioural Research in cancer, The Cancer Council Victoria; Australia: 2005. Sun Protection and Sunburn Incidence of Australian Adolescents: Summer 2003–2004. Prepared for. [Google Scholar]

- 17.http://sixtyminutes.ninemsn.com.au/stories/lizhayes/291312/dying-for-a-tan 60 Minutes. Dying for a tan.

- 18.Clare Oliver Melanoma Fund. www.clareolivermelanomafund.org

- 19.SunbedBan.comhttp://sunbedban.com

- 20.The dark side of tanning. www.darksideoftanning.com.au

- 21.Cancer Institute New South Wales. Wes Bonny testimonial. www.cancerinstitute.org.au/prevention-and-early-detection/public-education-campaigns/skin-cancer-prevention/wes-bonny-testimonial

- 22.SunSmart. www.sunsmart.com.au

- 23.Queensland Government. Sun safety. www.sunsafety.qld.gov.au/index.aspx

- 24.SunSmart Facebook page. www.facebook.com/SunSmartAus

- 25.SunSmart Twitter page. https://twitter.com/SunSmartVIC

- 26 .SunEffects Booth – Predict your skin's future. http://www.sunsafety.qld.gov.au/foryouth/phone-app.aspx

- 27.SunSmart smartphone app. www.sunsmart.com.au/resources/sunsmart-app

- 28.Sun Sound. http://sunsound.com.au

- 29.Sinclair C, Foley P. Skin cancer prevention in Australia. Br. J. Dermatol. 2009;161(Suppl. 3):116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green AC, Wallingford SC, McBride P. Childhood exposure to ultraviolet radiation and harmful skin effects: epidemiological evidence. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011;107(3):349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cancer Council Australia. SunSmart schools and early childhood programs. www.cancer.org.au/preventing-cancer/sun-protection/sunsmart-schools

- 32.Cancer Council Western Australia. www.cancerwa.asn.au/resources/2011-12-05-ccupational-exposure-to-ultraviolet-radiation.pdf

- 33.Cancer Council Western Australia. Publications for community groups, workplaces, schools and childcare centers: workplace resources. www.cancerwa.asn.au/resources/publications/prevention/#workplace

- 34.Queensland University of Technology. Make sun safe clothing fashionable. www.qut.edu.au/about/news/news?news-id=37817

- 35.Davis NC, Herron JJ. Queensland melanoma project: organization and a plea for comparable surveys. Med. J. Aust. 1966;1(15):643–644. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1966.tb72673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Report describing the first clinical campaign and the forerunner of early melanoma detection efforts in Australia.

- 36.Cancer Council Queensland. www.cancerqld.org.au

- 37.Melanoma Patients Australia. www.melanomapatients.org.au

- 38.Coory M, Baade P, Aitken J, Smithers M, McLeod GR, Ring I. Trends for in situ and invasive melanoma in Queensland, Australia, 1982–2002. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(1):21–27. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-3637-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Paper showing the shift of melanoma incidence rates to in situ and thinner lesions in Queensland up until 2002 and the stabilization of mortality rates.

- 39.Baade PD, Green AC, Smithers BM, Aitken JF. Trends in melanoma incidence among children: possible influence of sun-protection programs. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2011;11(5):661–664. doi: 10.1586/era.11.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Commentary on the observed reduction of melanoma incidence rates among children.

- 40.Baade PD, Youlden DR, Valery PC, et al. Trends in incidence of childhood cancer in Australia, 1983–2006. Br. J. Cancer. 2010;102(3):620–626. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cancer Council Victoria. Publications – skin cancer prevention research and evaluation (by research area) www.cancervic.org.au/pub-research-area-skin-cancer.html

- 42.Volkov A, Dobbinson S, Wakefield M, Slevin T. Seven-year trends in sun protection and sunburn among Australian adolescents and adults. Aust. NZ J. Public Health. 2013;37(1):63–69. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Green AC, Marquart L, Clemens SL, Harper CM, O’Rourke PK. Frequency of sunburn in Queensland adults: still a burning issue. Med. J. Aust. 2013;198(8):431–434. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marrett LD, Nguyen HL, Armstrong BK. Trends in the incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma in New South Wales, 1983–1996. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;92(3):457–462. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cancer Council Australia. Position statement: solariums. http://wiki.cancer.org.au/prevention/Position_statement_-_Solariums

- 46.The Australian. Health Minister Lawrence Springborg bans commercial tanning beds in Queensland after cancer fears. www.theaustralian.com.au/news/health-minister-lawrence-springborg-bans-commercial-tanning-beds-in-queensland-after-cancer-fears/story-e6frg6n6-1226743115513

- 47.Shih ST, Carter R, Sinclair C, Mihalopoulos C, Vos T. Economic evaluation of skin cancer prevention in Australia. Prev. Med. 2009;49(5):449–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Economic evaluation of the cost–effectiveness of investment in a national skin cancer prevention program in Australia.

- 48.Janda M, Kimlin MG, Whiteman DC, Aitken JF, Neale RE. Sun protection messages, vitamin D and skin cancer: out of the frying pan and into the fire? Med. J. Aust. 2007;186(2):52–54. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jardine A, Bright M, Knight L, Perina H, Vardon P, Harper C. Does physical activity increase the risk of unsafe sun exposure? Health Promot. J. Austr. 2012;23(1):52–57. doi: 10.1071/he12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.