Abstract

Background

Deficits in gait and balance are common among neurological inpatients. Currently, assessment of these patients is mainly subjective. New assessment options using wearables may provide complementary and more objective information.

Methods

In this prospective cross-sectional feasibility study performed over a four-month period, all patients referred to a normal neurology ward of a university hospital and aged between 40 and 89 years were asked to participate. Gait and balance deficits were assessed with wearables at the ankles and the lower back. Frailty, sarcopenia, Parkinsonism, depression, quality of life, fall history, fear of falling, physical activity, and cognition were evaluated with questionnaires and surveys.

Results

Eighty-two percent (n = 384) of all eligible patients participated. Of those, 39% (n = 151) had no gait and balance deficit, 21% (n = 79) had gait deficits, 11% (n = 44) had balance deficits and 29% (n = 110) had gait and balance deficits. Parkinson’s disease, stroke, epilepsy, pain syndromes, and multiple sclerosis were the most common diseases. The assessment was well accepted.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that the use of wearables for the assessment of gait and balance features in a clinical setting is feasible. Moreover, preliminary results confirm previous epidemiological data about gait and balance deficits among neurological inpatients. Evaluation of neurological inpatients with novel wearable technology opens new opportunities for the assessment of predictive, progression and treatment response markers.

Keywords: Accelerometer, Inertial sensor, Postural control, Neurological diseases

Background

Gait and balance deficits occur in many neurological diseases. The evaluation of these deficits at the wards of hospitals is often based on qualitative parameters collected by the treating physicians and allied health professionals or on semi-quantitative scoring tools. For example, in Parkinson’s disease (PD), the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) is regularly used to rate motor symptoms including gait and postural stability [1]. While such scales, questionnaires and surveys have been subject to multiple validation studies, they have limitations regarding inter-rater variability and subjectivity [2–5].

With the recent and ongoing development of wearables (mainly in the sport and fitness sectors), this technology has reached a sophisticated level making it interesting for medical purposes [6–16]. A particularly relevant field is the complementary assessment of inpatients at neurological wards, as wearables are specifically capable of assessing gait and balance deficits which are common in neurological patients [15, 17].

Only a small number of studies have investigated feasibility and acceptability of wearables in an inpatient setting, with limitations such as small sample sizes [18] and the investigation of only one disease [19]. This study aims to investigate the feasibility and usefulness of wearables during clinical evaluation in a large sample of neurological inpatients.

Methods

Participants

All inpatients referred to the three normal wards of the Neurology Center at the University Hospital of Tübingen between 09/2014 and 04/2015 (16-week assessment periods for each ward) were asked to take part in the study if they were between 40 to 89 years of age (this selection criterion was chosen due to feasibility issues) and were able to walk with or without walking aid. Exclusion criteria were the inability to give informed consent, a fall frequency of more than one fall per week (risk of falls during the assessment too high), and impaired cognition as defined by a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score below 10 points. Participants who had at least one fall during the last 2 years were defined as fallers. The ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Tübingen approved the study (No. 356/2014BO2) and all participants gave written informed consent prior to participation.

Quantitative gait and balance assessment

Participants were equipped with a wearable sensor system (Rehawatch®, Hasomed, Magdeburg, Germany) consisting of three sensor-units worn at both ankles and at the lower back (L4-L5) [20]. Each sensor-unit contains 3D accelerometers (±8 g), 3D gyroscopes (±2000°/s) and 3D magnetometers (±1.3Gs) resulting in nine degrees of freedom and the raw data was processed and analyzed using validated and company provided algorithms [21]. The assessment included the following tasks: Participants walked seven times a 20 m distance under single (slow, comfortable, and fast speed) and dual tasking conditions (checking boxes and subtracting serial 7 s during comfortable and fast walking) [22, 23]. Static balance during quiet standing at the center of stability was tested on flat ground with four different positions of the feet for 30 s each: open stance with feet placed in parallel position with 5–10 cm in between, closed stance (parallel position), semi-tandem stance, and tandem stance [24]. The task one difficulty level below the one successfully performed on flat ground was then performed for 30 s on a foam pad (Airex balance pad, 50x41x6 cm). Static balance at the limit of stability was tested with an adapted version of the Functional Reach Test [25] over a 15 s period. Overall mobility and transfer was tested with the Timed-Up-and-Go test (TUG) under comfortable and fast speed conditions [26–28]. Muscle strength was assessed with a hydraulic hand dynamometer (DanMic Global®, San Jose, USA) and muscle mass with bioimpedance (Akern Bia 101, SMT medical GmbH&Co. KG, Würzburg, Germany).

Assessments with scales and questionnaires

Fear of falling was assessed with the German version of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I) [29]. Self-concepts of health, activity, cognition, social support and risk factors for age-associated diseases were assessed [30]. Depression was evaluated with the German version of the Beck’s Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) [31, 32]. Health-related quality of life was assessed with the EQ-5D-5 L. This scale addresses mobility, autonomy, pain, fear, despondence, daily living activities and health [33]. The MMSE [34] and the Trail Making Test (TMT) [35] were used to assess cognition, and part III of the Movement Disorders Society-sponsored Unified Parkinson’s Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) [1] was used for the assessment of motor symptoms. Function of the sensory nerves was assessed at the medial malleoli of the lower extremities and the basal joint of each thumb with a Rydel Seiffer tuning fork.

Classification of impaired gait and balance

A gait deficit was defined as > 15% lower walking speed compared to mean age-corrected speed according to [36, 37]. Presence of a balance deficit was considered when tandem stance could be performed no longer than 10 s [38, 39].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with JMP 11.1.1 (SAS). Demographic data of the different groups were compared with Kruskal-Wallis-test (or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data). Post hoc testing was performed with Mann-Whitney-U test. P values below 0.05 were considered significant. Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was applied for post-hoc tests (p < 0.0083).

Results

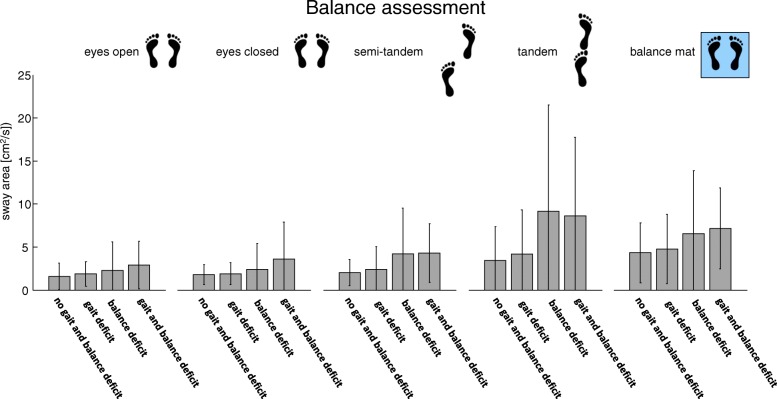

Of 468 inpatients eligible for the study (i.e., fulfilled all inclusion criteria and no exclusion criterion, and were not excluded due to logistic reasons), 384 (82%) participated. Of those, 60% were male. Mean age of the cohort was 62 years. The 10 most common diagnoses (69% of all investigated patients) were Parkinson’s disease (PD, n = 51), stroke (n = 50), epilepsy (n = 30), pain syndromes (n = 26), multiple sclerosis (MS, n = 23), CNS tumours (n = 19), polyneuropathy (n = 18), vertigo (n = 16), dementia (n = 16), and meningitis/encephalitis (n = 15). During the study, no severe adverse events occurred (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of the ten most common diagnoses within the 384 study participants

One hundred and 51 participants (39%) had no gait and balance deficit (control group), 79 (21%) had a gait deficit, 44 (11%) had a balance deficit and 110 (29%) had a gait and balance deficit. The highest proportion of patients with gait deficits (33%) was found in the meningitis/encephalitis cohort, the highest proportion of patients with balance deficits (17%) in the MS cohort, and the highest proportion of participants with gait and balance deficits (41%) in the PD cohort. Patients with pain syndromes had rarely gait and/or balance deficits.

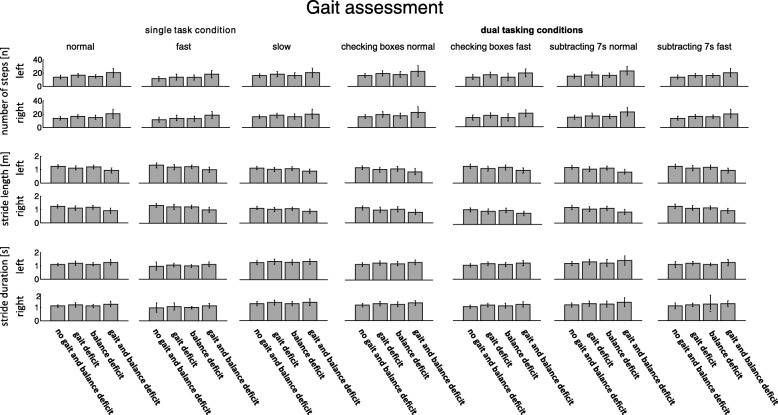

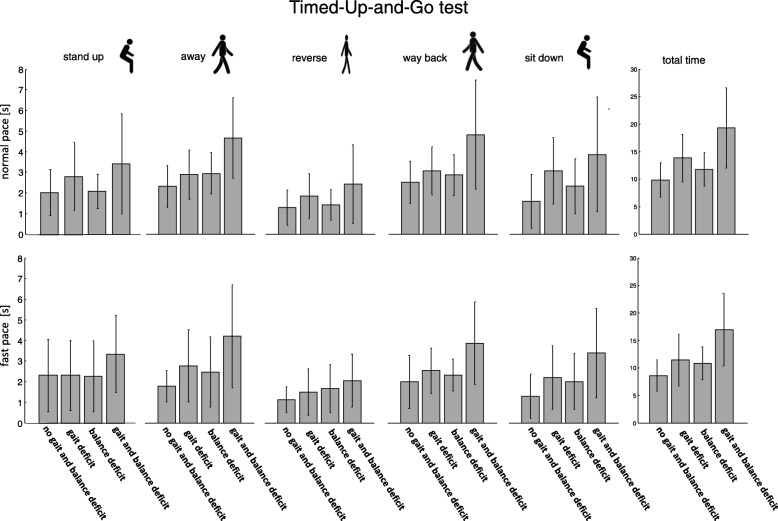

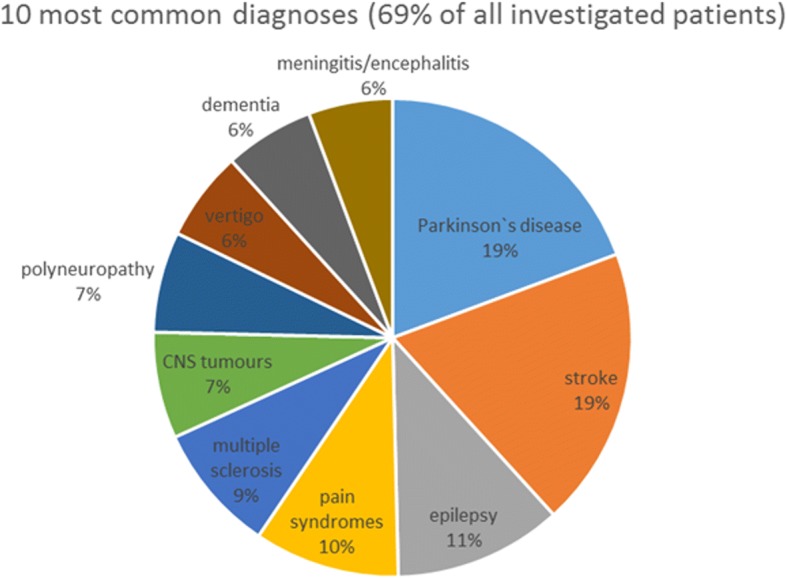

Patients complied well with the quantitative gait and balance assessment and descriptive results from the balance, gait and postural transitions are shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

Fig. 2.

During the balance assessment the participants with a balance or gait and balance deficit show the largest sway area compared to the controls and the patients with the gait deficit

Fig. 3.

During the gait assessments (single and dual task conditions) the participants with a gait or gait and balance deficit show the largest number of steps, the smallest stride length and the highest stride duration compared to the controls and the participants with a balance deficit

Fig. 4.

The TUG tests shows a similar pattern and the duration of the individual phases is increased for participants with a gait or gait and balance deficit compared to the controls and the participants with a balance deficit

MMSE and TMT performances were significantly worse in all cohorts with gait and/or balance deficits, compared to the control cohort. Moreover, the cohort with gait and balance deficits performed worse in the TMT compared to the group with gait deficits. TUG durations were slower in the cohort with gait and balance deficits than in both the gait deficit cohort and the balance deficit cohort, and fastest in the control cohort. The same pattern was observed with regard to fear of falling, with highest FES-I values (i.e. the highest fear of falling) in the gait and balance deficits cohort. BDI II values were higher in the cohort with gait and balance deficits, compared to the control cohort. The cohort with gait and balance deficits had lower grip force when compared to the cohort with gait deficits and the control cohort. A more detailed description of the inter-cohort comparisons is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and semiquantitative/quantitative study outcomes of the whole cohort, as well as of the subcohorts with and without gait and balance deficits

| Whole cohort (N = 384) | Controls (N = 151) | Gait deficits (N = 79) | Balance deficits (N = 44) | Gait and balance deficits (N = 110) | P-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | ||

| Age [years] | 64 | 40–90 | 57 | 40–86 | 60 | 40–89 | 70*# | 44–89 | 69.5*# | 41–90 | < 0.0001 |

| Gender [% female] | 42.4 | 43.0 | 36.7 | 43.2 | 45.5 | 0.67 | |||||

| Height [m] | 1.72 | 1.48–2.01 | 1.73 | 1.49–2.01 | 1.73 | 1.48–1.98 | 1.70 | 1.58–1.88 | 1.70 | 1.49–2.00 | 0.04 |

| Weight [kg] | 79 | 37–134 | 80 | 50–134 | 82 | 46–117 | 79 | 55–115 | 74 | 37–123 | 0.13 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 26.2 | 14.9–43.0 | 26.3 | 19.4–41.8 | 26.4 | 17.3–41.6 | 26.8 | 19.4–38.4 | 25.9 | 14.9–43.0 | 0.77 |

| Falls in the last 24 months [N] | 0 | 0–100 | 0 | 0–50 | 0 | 0–50 | 1* | 0–55 | 1*# | 0–100 | < 0.0001 |

| At least one fall in the last 24 months [%] | 46 | 29 | 42 | 62* | 65*# | < 0.0001 | |||||

| LACHS (0–15) | 3 | 0–10 | 2 | 0–8 | 3* | 0–6 | 3* | 1–9 | 4*# | 0–10 | < 0.0001 |

| MMSE (0–30) | 28 | 13–30 | 29 | 24–30 | 28* | 13–30 | 28* | 13–30 | 27* | 13–30 | < 0.0001 |

| TMT-A [s] | 49 | 13–300 | 38 | 13–300 | 48* | 23–300 | 55* | 26–300 | 72*# | 17.7–300 | < 0.0001 |

| TMT-B [s] | 149 | 34–300 | 101 | 34–300 | 129* | 38–300 | 174* | 60–300 | 300*# | 38.8–300 | < 0.0001 |

| ∆TMT [s] | 85 | −30-280 | 60 | −30-280 | 78* | 0–253 | 98 | 0–257 | 149* | 0–270 | < 0.0001 |

| Timed up and go convenient speed [s] | 12 | 6–92 | 10 | 6–25 | 12* | 8–28 | 11* | 8–18 | 16*#+ | 8–92 | < 0.0001 |

| Timed up and go fast speed [s] | 9 | 5–47 | 7 | 5–15 | 10* | 6–22 | 11* | 6–15 | 14*#+ | 7–47 | < 0.0001 |

| BDI II (0–63) | 10 | 0–51 | 8 | 0–51 | 10 | 0–28 | 10 | 0–38 | 12* | 0–51 | 0.0004 |

| FES-I (0–64) | 20 | 0–64 | 18 | 0–63 | 21* | 0–44 | 20* | 14–48 | 27*#+ | 14–64 | < 0.0001 |

| EQ5D VAS (0–100) | 60 | 1–100 | 70 | 20–100 | 55 | 10–95 | 50* | 5–90 | 50*# | 1–95 | < 0.0001 |

| Functional Reach [cm] | 23 | 3–82 | 27 | 8–45 | 23* | 3–82 | 20* | 5–35 | 18*# | 5–34 | < 0.0001 |

| Gait speed [m/s] | 1.10 | 0.27–2.33 | 1.34 | 0.95–2.33 | 0.99* | 0.56–1.67 | 1.15*# | 0.81–2.03 | 0.80*#+ | 0.27–1.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Grip force [kg] | 27 | 3–76 | 29 | 10–76 | 29 | 7–56 | 28 | 15–51 | 23*# | 3–51 | < 0.0001 |

Data is presented with median and range. P-values were calculated using the Kruskal-Wallis-test, with post hoc Mann-Whitney-U-Test and Chi2 test. For post hoc testing Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was applied. * p < 0.0083 for comparison with the control cohort group, #p < 0.0083 for comparison with the gait deficit cohort, +p < 0.0083 for comparison with the balance deficit cohort. BDI II Beck’s depression inventory II, BMI Body mass index, EQ5D VAS Visual analog scale of the EuroQol-5 dimension questionnaire, FES-I Falls efficacy scale international, LACHS Geriatric screening according to Lachs et al., MMSE Mini-mental state examination, TMT Trail making test (part A, B, and B-A = ∆TMT)

Discussion

In the presented study, we performed routine clinical gait and balance assessments complemented by an exhaustive evaluation of geriatric parameters in a neurological department at a university hospital. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first sensor-based cross-sectional study in a clinical environment of a university hospital, covering a wide range of neurological diseases. Our overall cohort represents a wide range and representative number of neurological diseases. A study with a similar setting but without sensor-unit-based assessments displayed a comparable composition of neurological diseases [17] with the five most common diagnoses completely overlapping.

Acceptance of sensor-unit-based assessments in our study was high. Only 18% of eligible patients refused to take part in the study. We did not experience any logistical issues during the assessments. The sensor system was easy and quick to apply and none of the patients felt restricted by the sensor system. Moreover, no serious adverse events, e.g. falls, occurred. These results bode well for the clinical uptake of wearable sensors into regular care.

Not surprisingly, frequencies of gait and balance deficits of neurological inpatients are higher compared to observations in the community and in outpatient clinics. However, these deficits are ubiquitously observed. In a community-based study investigating 467 participants, the prevalence of gait deficits was 14% in those between 67 and 74 years of age, 29% in those between 75 and 84 years and 49% in those 85 years and older [40]. In a cross-sectional investigation of 488 community residing adults aged between 60 and 97 years, 32% of the cohort presented with impaired gait and the prevalence increased with age. However, 38% of the subjects aged 80 years and older still had a normally preserved gait [41]. In outpatients clinics, gait deficits occur in 35% of patients, most of them having neurological causes [42].

It is of note that, in our study, the cohort with gait (but not balance) deficits was of similar age as the control cohort. This suggests that the slower gait speed of this group was not induced by an overall decline in performance due to aging, but rather due to the underlying disease processes. This could be an interesting observation in the light of ongoing studies investigating gait speed as a relevant outcome parameter for disease and disability. Moreover, groups with gait and/or balance deficits showed impaired cognitive performance compared to the control group, supporting the association between motor performance and cognition [43–45]. It is also of note that not only the balance deficit cohort but also the gait deficit cohort performed worse than the controls in the functional reach test. This finding supports the link between static balance and gait and reflects the various aspects of postural control which should be further investigated in future studies.

The current study has several limitations. First, only gait velocity was used to define gait deficits. Although reduced gait speed impacts patients’ mobility, there are several additional gait variables (e.g. gait variability, asymmetry) which are important features as they are associated with fall risk [46–49]. However, numerous more sophisticated algorithms are currently developed and validated allowing investigation of the multidimensional aspects of postural control (e.g., [20, 50, 51]) in more detail. Including dynamic, proactive, and reactive postural control parameters will give a broader view of the multidimensional aspects of balance control and help understand different pathologies of the diseases. This aspect is currently the focus of a more detailed sensor-unit-based analysis of the dataset.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that the use of inertial sensors in a clinical setting by investigating patients in neurological wards of a university hospital over a time of 16 weeks is feasible. These results should motivate to further design inpatient assessments using wearable technology, and of collaborative projects using such datasets for further in-depth analyses.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants who took part in the study and the financial support by Land Schleswig-Holstein within the funding programme Open Access Publikationsfonds.

Funding

We acknowledge financial support by Land Schleswig-Holstein within the funding programme Open Access Publikationsfonds.

Availability of data and materials

Due to ethical restrictions imposed by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Tuebingen related to approved patient consent procedure and protecting patient privacy, all relevant data should be requested at Prof. Maetzler directly using the email address w.maetzler@neurologie.uni-kiel.de. The Ethical Committee decided how data of this particular study should be handled by the researchers, however, the Ethical Committee does not have access to the actual datas.

Abbreviations

- BDI-II

Beck’s Depression Inventory II

- EQ-5D-5 L

Instrument to assess health-related quality of life

- FES-I

Falls Efficacy Scale-International

- MDS-UPDRS

Movement Disorders Society-sponsored Unified Parkinson’s Rating Scale

- MMSE

Minimal Mental State Examination

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- TMT

Trail Making Test

- TUG

Timed-Up-and-Go test

Authors’ contributions

WM, FPB, and KB, conceived and planned the experiments. FPB, JS, KB, MAH, CA, YGW, and SP carried out the experiments. FPB, NMG, CS, CH, and WM contributed to the interpretation of the results and took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Tübingen approved the study and all participants gave written informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for publication

This submission is made in agreement with my colleagues who were fully involved in the study and preparation of the manuscript. Each of the authors has read and concurs with the content in the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Felix P. Bernhard, Email: Felix.Bernhard@uk-gm.de

Jennifer Sartor, Email: j.sartor@freenet.de.

Kristina Bettecken, Email: tina.bettecken@gmx.net.

Markus A. Hobert, Email: m.hobert@neurologie.uni-kiel.de

Carina Arnold, Email: Carina.Arnold@gmx.net.

Yvonne G. Weber, Email: yvonne.weber@uni-tuebingen.de

Sven Poli, Email: sven.poli@icloud.com.

Nils G. Margraf, Email: n.margraf@neurologie.uni-kiel.de

Christian Schlenstedt, Email: c.schlenstedt@neurologie.uni-kiel.de.

Clint Hansen, Phone: +49 431 500-23995, Email: C.Hansen@neurologie.uni-kiel.de.

Walter Maetzler, Email: w.maetzler@neurologie.uni-kiel.de.

References

- 1.Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, Stebbins GT, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;23:2129–2170. doi: 10.1002/mds.22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parry SW, Deary V, Finch T, Bamford C, Sabin N, McMeekin P, et al. The STRIDE (strategies to increase confidence, InDependence and energy) study: cognitive behavioural therapy-based intervention to reduce fear of falling in older fallers living in the community - study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:210. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canning C, Sherrington C, Lord S, Fung V, Close J, Latt M, et al. Exercise therapy for prevention of falls in people with Parkinson’s disease: a protocol for a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong TH, Nguyen HV, Chiu MT, Chow KY, Ong MEH, Lim GH, et al. The low fall as a surrogate marker of frailty predicts long-term mortality in older trauma patients. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veuas BJ, Wayne SJ, Romero LJ, Baumgartner RN, Garry P. Fear of falling and restriction of mobility in elderly fallers. Age Ageing. 1997;26:189–193. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starkstein SE, Merello M. The unified parkinson’s disease rating scale: validation study of the mentation, behavior, and mood section. Mov Disord. 2007;22:2156–61. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17721877. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Rampp A, Barth J, Schuelein S, Gassmann K-G, Klucken J, Eskofier BM. Inertial sensor-based stride parameter calculation from gait sequences in geriatric patients. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2015;62:1089–97. Available from: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6949634/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Schülein S, Barth J, Rampp A, Rupprecht R, Eskofier BM, Winkler J, et al. Instrumented gait analysis: a measure of gait improvement by a wheeled walker in hospitalized geriatric patients. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2017;14:18. Available from: http://jneuroengrehab.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12984-017-0228-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Klucken J, Barth J, Kugler P, Schlachetzki J, Henze T, Marxreiter F, et al. Unbiased and mobile gait analysis detects motor impairment in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56956. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Bianchi MT. Sleep devices: wearables and nearables, informational and interventional, consumer and clinical. Metabolism. 2018;84:99–108. 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Torous J, Firth J, Mueller N, Onnela JP, Baker JT. Methodology and reporting of mobile heath and smartphone application studies for schizophrenia. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25:146–154. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pevnick JM, Birkeland K, Zimmer R, Elad Y, Kedan I. Wearable technology for cardiology: an update and framework for the future. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2018;28:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haghi M, Thurow K, Stoll R. Wearable devices in medical internet of things: scientific research and commercially available devices. Healthc Inform Res. 2017;23:4–15. doi: 10.4258/hir.2017.23.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cahn A, Akirov A, Raz I. Digital health technology and diabetes management. J Diabetes. 2018;10:10–17. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vienne A, Barrois RP, Buffat S, Ricard D, Vidal P-P. Inertial sensors to assess gait quality in patients with neurological disorders: a systematic review of technical and analytical challenges. Front Psychol. 2017;8:817. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maetzler W, Klucken J, Horne M. A clinical view on the development of technology-based tools in managing Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31:1263–1271. doi: 10.1002/mds.26673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stolze H, Klebe S, Baecker C, Zechlin C, Friege L, Pohle S, et al. Prevalence of gait disorders in hospitalized neurological patients. Mov Disord. 2005;20:89–94. doi: 10.1002/mds.20266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora S, Venkataraman V, Zhan A, Donohue S, Biglan KM, Dorsey ER, et al. Detecting and monitoring the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease using smartphones: a pilot study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21:650–3. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1353802015000814. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Silva de Lima AL, Hahn T, Evers LJW, de Vries NM, Cohen E, Afek M, et al. Feasibility of large-scale deployment of multiple wearable sensors in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189161. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Pham MH, Elshehabi M, Haertner L, Din SD, Srulijes K, Heger T, et al. Validation of a step detection algorithm during straight walking and turning in patients with Parkinson’s disease and older adults using an inertial measurement unit at the lower back. Front Neurol. 2017;8:457. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donath L, Faude O, Lichtenstein E, Nüesch C, Mündermann A. Validity and reliability of a portable gait analysis system for measuring spatiotemporal gait characteristics: comparison to an instrumented treadmill. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2016;13:6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26790409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Hobert MA, Niebler R, Meyer SI, Brockmann K, Becker C, Huber H, et al. Poor Trail making test performance is directly associated with altered dual task prioritization in the elderly - baseline results from the TREND study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elshehabi M, Maier KS, Hasmann SE, Nussbaum S, Herbst H, Heger T, et al. Limited effect of dopaminergic medication on straight walking and turning in early to moderate Parkinson’s disease during single and dual tasking. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Maetzler W, Mancini M, Liepelt-Scarfone I, Müller K, Becker C, van Lummel RCRC, et al. Impaired trunk stability in individuals at high risk for Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasmann SE, Berg D, Hobert MA, Weiss D, Lindemann U, Streffer J, et al. Instrumented functional reach test differentiates individuals at high risk for Parkinson’s disease from controls. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:286. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “up & go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Uem JMT, Walgaard S, Ainsworth E, Hasmann SE, Heger T, Nussbaum S, et al. Quantitative timed-up-and-go parameters in relation to cognitive parameters and health-related quality of life in mild-to-moderate Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151997. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Weiss A, Herman T, Plotnik M, Brozgol M, Maidan I, Giladi N, et al. Can an accelerometer enhance the utility of the timed up & go test when evaluating patients with Parkinson’s disease? Med Eng Phys. 2010;32:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dias N, Kempen GIJM, Beyer N, Freiberger E, Yardley L. Die Deutsche Version der Falls Efficacy Scale-International Version. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;39:297. 10.1007/s00391-006-0400-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Lachs MS, Becker M, Siegal AP, Miller RL, Tinetti ME. Delusions and behavioral disturbances in cognitively impaired elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:768–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kühner C, Bürger C, Keller F, Hautzinger M. Reliabilität und Validität des revidierten Beck-Depressionsinventars (BDI-II) Nervenarzt. 2007;78:651–656. doi: 10.1007/s00115-006-2098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Beamesderfer A. Assessment of depression: the depression inventory. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7:151–169. doi: 10.1159/000395074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10109801. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown EC, Casey A, Fisch RI, Neuringer C. Trial making test as a screening device for the detection of brain damage. J Consult Psychol. 1958;22:469–74. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13611107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Bohannon RW, Williams AA. Normal walking speed: a descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2011;97:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305:50–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amadori K, Püllen R, Steiner T. Gangstörungen im Alter. Nervenarzt. 2014;85:761–772. doi: 10.1007/s00115-014-4084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odenheimer G, Funkenstein HH, Beckett L, Chown M, Pilgrim D, Evans D, et al. Comparison of neurologic changes in “successfully aging” persons vs the Total aging population. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:573–580. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540180051013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahlknecht P, Kiechl S, Bloem BR, Willeit J, Scherfler C, Gasperi A, et al. Prevalence and burden of gait disorders in elderly men and women aged 60–97 years: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69627. Available from: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Verghese J, LeValley A, Hall CB, Katz MJ, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB. Epidemiology of gait disorders in community-residing older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:255–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fitzpatrick AL, Buchanan CK, Nahin RL, Dekosky ST, Atkinson HH, Carlson MC, et al. Associations of gait speed and other measures of physical function with cognition in a healthy cohort of elderly persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1244–51. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18000144. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Parihar R, Mahoney JR, Verghese J. Relationship of gait and cognition in the elderly. Curr Transl Geriatr Exp Gerontol Rep. 2013;2:167–73. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s13670-013-0052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Hall CB, Derby CA, Kuslansky G, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2508–16. Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMoa022252. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1050–6. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0003999301632155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Johansson J, Nordström A, Nordström P. Greater fall risk in elderly women than in men is associated with increased gait variability during multitasking. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:535–40. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27006336. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Dadashi F, Mariani B, Rochat S, Büla CJ, Santos-Eggimann B, Aminian K. Gait and foot clearance parameters obtained using shoe-worn inertial sensors in a large-population sample of older adults. Sensors (Basel). 2013;14:443–57. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/14/1/443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Del Din S, Godfrey A, Rochester L. Validation of an accelerometer to quantify a comprehensive battery of gait characteristics in healthy older adults and Parkinson’s disease: toward clinical and at home use. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics. 2016;20:838–847. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2015.2419317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mancini M, Chiari L, Holmstrom L, Salarian A, Horak FB. Validity and reliability of an IMU-based method to detect APAs prior to gait initiation. Gait Posture. 2016;43:125–31. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26433913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Pham MH, Elshehabi M, Haertner L, Heger T, Hobert MA, Faber GS, et al. Algorithm for turning detection and analysis validated under home-like conditions in patients with Parkinson’s disease and older adults using a 6 degree-of-freedom inertial measurement unit at the lower back. Front Neurol. 2017;8:135. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fneur.2017.00135/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical restrictions imposed by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Tuebingen related to approved patient consent procedure and protecting patient privacy, all relevant data should be requested at Prof. Maetzler directly using the email address w.maetzler@neurologie.uni-kiel.de. The Ethical Committee decided how data of this particular study should be handled by the researchers, however, the Ethical Committee does not have access to the actual datas.