Abstract

For HIV-1 serodiscordant couples, HIV-1 exposure and risk of transmission is heightened during pregnancy attempts, but safer conception strategies can reduce risk. As safer conception programs are scaled up, understanding couples’ preferences and experiences can be useful for programmatic recommendations. We followed 1013 high-risk, heterosexual HIV-1 serodiscordant couples from Kenya and Uganda for two years in an open-label delivery study of integrated pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and antiretroviral therapy (ART), the Partners Demonstration Project. We used descriptive statistics to describe the cohort and multivariate logistic regression to characterize women who reported use of a safer conception strategy by their first annual visit. 66% (569/859) of women in the study were HIV-infected and 73% (627/859) desired children in the future. At the first annual visit, 59% of women recognized PrEP, 58% ART, 50% timed condomless sex, 23% self-insemination, and fewer than 10% recognized male circumcision, STI treatment, artificial insemination, and sperm washing as safer conception strategies. Among those recognizing these strategies and desiring pregnancy, 37% reported using PrEP, 14% ART, and 30% timed condomless sex. Women who reported discussing their fertility desires with their male partners were more likely to report having used at least one strategy for safer conception (adjusted odds ratio=1.91, 95% confidence interval:1.26–2.89). Recognition of use of safer conception strategies among women who expressed fertility desires was low, with ARV-based strategies and self-insemination the more commonly recognized and used strategies. Programs supporting HIV-1 serodiscordant couples can provide opportunities for couples to talk about their fertility desires and foster communication around safer conception practices.

Keywords: safer conception, HIV-1 serodiscordant couples, family planning, PrEP, ART

Introduction

HIV-1 serodiscordant couples—couples in which one partner is HIV-1 infected and the other is not—are a key population for HIV-1 prevention interventions due to substantial HIV-1 exposure and high risk of transmission to the uninfected partner.1 In sub-Saharan Africa, HIV-1 serodiscordant couples are a sizable population; clinical and mathematical modelling studies have estimated that 45–75% of HIV-1 infected individuals have an HIV-1 uninfected partner (Dunkle et al., 2004; Piot, Bartos, Larson, Zewdie, & Mane, 2008).

Globally, 20–50% of HIV-1 serodiscordant couples report desiring additional children and pregnancy desire is often given as a reason for engaging in condomless sex despite known HIV-1 risk (Mujugira et al., 2013; Ngure et al., 2012). Studies have also reported that among HIV-1 serodiscordant couples who became pregnant, HIV status had not diminished desires to have children (Mujugira et al., 2013; et al., 2014; Pintye et al., 2015). HIV-1 serodiscordant couples face a complex set of decisions about whether to satisfy their fertility desires. For couples who desire children, the sexual and perinatal transmission risks associated with conception and pregnancy can be substantially reduced by planning pregnancies and utilizing safer conception strategies (Ciaranello & Matthews, 2015; Cohan et al., 2012; Mmeje et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2013).

Counseling on serodiscordancy, repeated HIV-1 testing for the uninfected partner, and antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation and sustained use lies at the foundation of HIV-1 prevention services for HIV-1 serodiscordant couples. Counseling can be further tailored to accommodate a couple’s fertility goals, which can include delaying, avoiding, or achieving pregnancy. Fertility goals often change throughout a lifetime (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2005) and counseling should reflect that flexibility. When couples desire pregnancy, safer conception strategies encompass a variety of options: antiretroviral-based strategies (including ART use by the HIV-1 infected partner and pre-exposure prophylaxis [PrEP] use by the HIV-1 uninfected partner), timing condomless sex to periods with peak fertility, STI treatment, basic fertility screening (e.g. considering medical history for episodes of amenorrhea or adverse pregnancy outcomes), medically-assisted reproduction (including sperm-washing and artificial-insemination), and male circumcision and vaginal self-insemination when the woman is the HIV-1 infected partner (Ciaranello & Matthews, 2015; Cohan et al., 2012; Liao et al., 2015; Weber et al., 2013).

To scale up effective safer conception programs for HIV-1 serodiscordant couples during pregnancy attempts, recommendations and priorities must encompass user preferences and experiences. In a large cohort of HIV-1 serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda, we assessed couples’ knowledge of, attitudes towards, and experiences using safer conception strategies.

Methods

The Partners Demonstration Project was an open-label delivery study of PrEP and ART as an integrated prevention strategy among 1013 high-risk heterosexual HIV-1-serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda (Baeten et al., 2015). Enrollment occurred between November 2012 and August 2014; participants were followed for 2 years. In this study, all HIV-1 uninfected partners were offered PrEP and HIV-1 infected partners were referred for ART initiation according to national guidelines (initially CD4 count <350ul/mL, but guidelines were revised in both countries in 2014 to include all HIV-infected individuals in a serodiscordant relationship regardless of clinical indications) (Uganda Ministry of Health, 2013; Kenya Ministry of Health, 2014). PrEP discontinuation was encouraged when HIV-1 infected partners had sustained ART use for at least 6 months. Discontinuation of PrEP was encouraged because simultaneous use of PrEP and ART in a HIV-1 serodiscordant couple may not be cost-effective (Letchumanan, Coyte, & Loutfy, 2015; Ying et al., 2015), given the efficiency of ART at reducing HIV-1 transmission by six months (Cohen et al., 2011; Ping et al., 2013).

At the time of study enrollment, HIV-1 infected partners were not using ART, and HIV-1 uninfected partners had normal renal function and were not pregnant. HIV-1 infected women could be pregnant at enrollment. Couples selected for enrollment were defined as high risk using an externally validated scoring tool that encompasses demographic, clinical, and medical characteristics (Kahle et al., 2013). The primary study results estimate that the integrated PrEP and ART strategy reduced HIV-1 transmission by 96% (95% CI 60–100%) (Baeten et al., 2015).

Data collection

All participants attended quarterly study visits. For HIV-1 uninfected partners, visit procedures included HIV counseling and testing, PrEP provision, PrEP adherence counseling, and creatinine testing at 6-month intervals. For HIV-1 infected partners, visit procedures included encouragement to initiate ART based on national guidelines, and CD4 and viral load testing at 6-month intervals. For all women, pregnancy testing was conducted when clinically indicated.

At all visits, we collected demographic, medical, and sexual behaviour data, including participant fertility desires and intentions via interviewer-administered questionnaires in the participant’s preferred language. Couples were encouraged to attend visits together and study staff provided safer conception counseling, including discussion of HIV-1 transmission risk during pregnancy and pregnancy attempts and methods to mitigate risk when either partner indicated fertility desires. Study staff received training on safer conception strategies, but there was no standardized protocol or tools for providing safer conception counseling. Training included description of all possible safer conception methods, with a focus on methods that were most accessible to study participant including PrEP, ART and timed condomless sex. Menstrual cycle monitoring was included in the training to ensure that providers could discuss the timing of condomless sex to peak fertility days with participants. Each site had referral information for fertility clinics in the country that would provide sperm washing and other fertility services to discordant couples.

At the 1-year visit, we asked additional questions about safer conception of each participant, including: participant knowledge, willingness to use, and experiences with strategies. Participants were not prompted with each possible strategy but asked to list strategies familiar to them to assess knowledge and recognition of the utility of each strategy for safer conception. We only assessed willingness to use and experiences with a specific strategy among those who indicated knowledge of that method. For the logistic regression analysis, we focused specifically women’s responses at the 1-year visit to the question: “What things have you done to reduce risk when trying to conceive a baby?”, which incorporates recognition of the strategy as well as use of the strategy. The question was not bound to a time frame.

Statistical methods

We used descriptive methods to summarize the study population and knowledge, attitudes, and experiences with individual safer conception strategies. Logistic regression was used to identify demographic, medical, and behavioural characteristics of women who reported using at least one safer conception method at their first annual visit. We decided a priori to adjust our final model for the HIV status and the age of the female partner. In addition, the final model included any variables that were associated with having used at least 1 safer conception strategy (at a p-value of <0.1).

The protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Division at the University of Washington and ethics committees for all study sites. Participants provided written informed consent

Results

Of the 1013 couples enrolled in the Partners Demonstration Project, 859 (85%) were included in our final analysis; 154 were excluded due to missing outcome data, primarily related to the female partner missing the first annual study visit. In most couples, the female partner was HIV-infected (66%). The median age for men and women was 32 years (interquartile range [IQR] 27–40) and 27 years (IQR 23–32), respectively. At enrollment, 672 (78%) women had at least one living child, 239 (28%) were using highly effective contraception, and 108 (20%) of the HIV-1 infected women were pregnant (Table 1). Among HIV-1 infected and uninfected women, respectively, 448 (79%) and 170 (59%) desired additional biological children. Among all HIV-1 infected partners, the median CD4 count was 436 cells/mm3 (IQR 296–662) and median viral load was 4.6 log10 copies/mL (IQR 3.7–4.9) at baseline.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics at baseline (N = 1,718)

| Female partner HIV- uninfected |

Female partner HIV-infected | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All N = 1,718 |

Women N=290 |

Men N=290 |

Women N=569 |

Men N=569 |

|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age | |||||

| <24 years | 420 (24.5) | 72 (24.8) | 17 (5.9) | 235 (41.3) | 96 (16.9) |

| 25–29 years | 442 (25.7) | 78 (26.9) | 47 (16.2) | 160 (28.1) | 157 (27.6) |

| 30–34 years | 333 (19.4) | 61 (21.0) | 63 (21.7) | 85 (14.9) | 124 (21.8) |

| 35+ years | 523 (30.4) | 79 (27.2) | 163 (56.2) | 89 (15.6) | 192 (33.7) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 1647 (95.9) | 284 (97.9) | 283 (97.6) | 537 (94.4) | 543 (95.4) |

| Single | 71 (4.1) | 6 (2.1) | 7 (2.4) | 32 (5.6) | 26 (4.6) |

| Self-earned income | |||||

| None | 340 (19.8) | 96 (33.1) | 4 (1.4) | 219 (38.5) | 21 (3.7) |

| Yes | 1378 (80.2) | 194 (66.9) | 286 (98.6) | 350 (61.5) | 548 (96.3) |

| Living children | |||||

| 0 | 390 (22.7) | 29 (10.0) | 31 (10.7) | 158 (27.8) | 172 (30.2) |

| 1 | 408 (23.8) | 59 (20.3) | 50 (17.2) | 174 (30.6) | 125 (22.0) |

| 2+ | 920 (53.6) | 202 (69.7) | 209 (72.1) | 237 (41.7) | 272 (47.8) |

| Living children with study partner | |||||

| 0 | 918 (53.4) | 103 (35.5) | 101 (34.8) | 357 (62.7) | 357 (62.7) |

| 1 | 336 (19.6) | 62 (21.4) | 65 (22.4) | 105 (18.5) | 104 (18.3) |

| 2+ | 464 (27.0) | 125 (43.1) | 124 (42.8) | 107 (18.8) | 108 (19.0) |

| Sex acts with study partner in month prior | |||||

| None | 76 (4.4) | 19 (6.6) | 17 (5.9) | 22 (3.9) | 18 (3.2) |

| 1–3 | 728 (42.4) | 135 (46.6) | 143 (49.3) | 227 (39.9) | 223 (39.2) |

| 4–6 | 415 (24.2) | 65 (22.4) | 67 (23.1) | 143 (25.1) | 140 (24.6) |

| 7+ | 499 (29.1) | 71 (24.5) | 63 (21.7) | 177 (31.1) | 188 (33.0) |

| Condom use with study partner in prior month | |||||

| 100% | 576 (33.5) | 116 (40.0) | 116 (40.0) | 172 (30.2) | 172 (30.2) |

| 50–99% | 228 (13.3) | 32 (11.0) | 32 (11.0) | 82 (14.4) | 82 (14.4) |

| <50% | 844 (49.1) | 125 (43.1) | 125 (43.1) | 297 (52.2) | 297 (52.2) |

| No sex | 70 (4.1) | 17 (5.9) | 17 (5.9) | 18 (3.2) | 18 (3.2) |

| Contraceptive usage | |||||

| None | 427 (50.2) | 159 (56.0) | --- | 268 (47.3) | --- |

| Condoms only | 77 (9.1) | 25 (8.8) | --- | 52 (9.2) | --- |

| Highly effective method* | 239 (28.1) | 100 (35.2) | --- | 139 (24.5) | --- |

| Currently pregnant | 108 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) | --- | 108 (19.0) | --- |

| WHO staging | |||||

| Stage 1 | 591 (68.8) | --- | 175 (60.3) | 416 (73.1) | --- |

| Stage 2 | 268 (31.2) | --- | 115 (39.7) | 153 (26.9) | --- |

| CD4 count | |||||

| <250 | 187 (17.9) | --- | 85 (29.4) | 102 (18.0) | --- |

| 250–499 | 318 (30.5) | --- | 97 (33.6) | 221 (38.9) | --- |

| 500–999 | 352 (33.7) | --- | 107 (37.0) | 245 (43.1) | --- |

| 1,000+ | 187 (17.9) | --- | 85 (29.4) | 102 (18.0) | --- |

| Viral load (copies/ulu) | |||||

| <50 | 43 (5.08) | --- | 10 (3.5) | 33 (5.9) | --- |

| 50–9,999 | 197 (23.3) | --- | 42 (14.6) | 155 (27.8) | --- |

| 10,000–99,999 | 387 (45.7) | --- | 122 (42.4) | 265 (47.5) | --- |

| 100,000+ | 219 (25.9) | --- | 114 (39.6) | 105 (18.8) | --- |

| Perceived risk of HIV transmission to partner | |||||

| High | 250 (22.5) | --- | 57 (19.7) | 193 (33.9) | --- |

| Medium | 360 (32.5) | --- | 140 (48.3) | 220 (38.7) | --- |

| Low | 118 (10.6) | --- | 42 (14.5) | 76 (13.4) | --- |

| None | 131 (11.8) | --- | 51 (17.6) | 80 (14.1) | --- |

| Unsure | 250 (22.5) | --- | 57 (19.7) | 193 (33.9) | --- |

| Fertility desires | |||||

| None | 461 (26.9) | 118 (40.8) | 109 (37.6) | 121 (21.3) | 113 (19.9) |

| Currently trying or Pregnant | 324 (18.9) | 20 (6.9) | 21 (7.2) | 146 (25.7) | 137 (24.1) |

| Within 3 years | 546 (31.8) | 87 (30.1) | 91 (31.4) | 172 (30.2) | 196 (34.5) |

| In >3 years or unsure | 386 (22.5) | 64 (22.1) | 69 (23.8) | 130 (22.8) | 123 (21.6) |

| Discussed fertility desires with partner | |||||

| No | 367 (21.4) | 70 (24.2) | 51 (17.6) | 131 (23.1) | 115 (20.2) |

| Yes | 1349 (78.6) | 219 (75.8) | 239 (82.4) | 437 (76.9) | 454 (79.8) |

Highly effective contraceptive methods include birth control pills, IUDs, and hormonal injections.

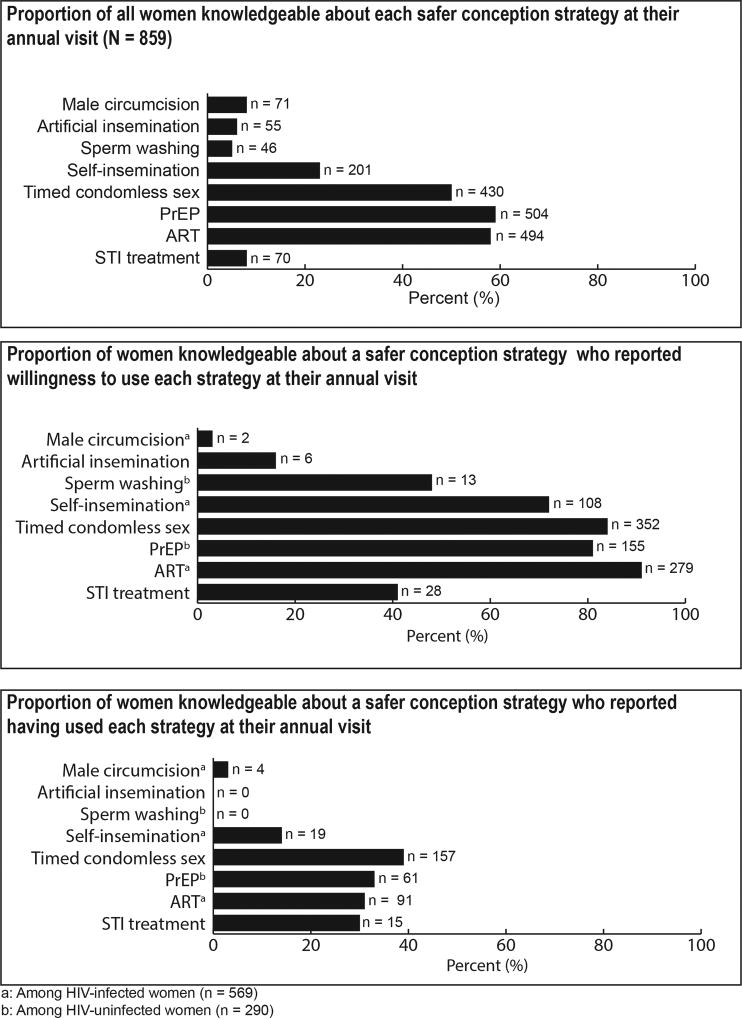

At 1-year post enrollment, 84% of women could identify at least one safer conception method when asked, “What things can couples do to reduce risk when trying to conceive a baby”. Women were most knowledgeable about ARV-based strategies (PrEP [59%], ART [58%]), timed condomless sex (50%), and self-insemination (23%) (Figure 1). Less than 10% of women cited male circumcision (8%), artificial insemination (6%), STI treatment (8%), or sperm washing (5%) as safer conception methods. Knowledge of methods were similar between women with immediate fertility desires during the study vs those who did not (PrEP [61% vs. 56%], ART [59% vs. 56%], timed condomless sex [52% vs. 48%], self-insemination [28% vs. 20%], male circumcision [9% vs. 8%], artificial insemination [6% vs. 7%], STI treatment [9% vs. 8%], and sperm washing [4% vs. 6%]). Women who were knowledgeable about a method aligning with their HIV-status often expressed willingness to use that method (ART [91%], timed condomless sex [84%], PrEP [81%], and self-insemination [72%]). However, less than half of the women described male circumcision (3%)—2% among women whose current partner was uncircumcised at baseline—artificial insemination (16%), STI treatment (41%) and sperm washing (48%) as safer conception strategies they would be willing to try or suggest to their partner.

Figure 1.

Knowledge, willingness, and experience with safer conception strategies

In 378 (44%) couples, at least one member reported a current pregnancy or that they had immediate fertility desires and were attempting to conceive during quarterly study visits. Among those with immediate fertility desires or reported pregnancy, 215 (57%) couples had at least one member who reported using a method for safer conception at any time prior to their first annual visit, including 176 (48%) women and 44 (58%) men. Reports of using safer conception strategies were mostly similar between partners (80%), but 20% of couples had one partner report use of a safer conception method while the other partner reported no usage. Among the 366 women who reported immediate fertility desires during the study, the most common methods used were: timed condomless sex (reported by 110 [30%] women), ART (reported by 97 [14%] HIV-1 infected women), PrEP (reported by 37 [39%] HIV uninfected women), and STI treatment (reported by 7 [2%] women). One HIV-infected male participant reported having used sperm washing and two HIV-uninfected men reported having used artificial insemination. No women reported experience with sperm washing or artificial insemination.

Factors significantly associated with women reporting the use of at least one safer conception method were: discussing fertility desires with their male partners (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13–2.86), not earning income (aOR = 2.19, 95% CI 1.50–3.20), having no living children (aOR = 2.18, 95% CI 1.42–3.54), and having (or their partner having) WHO stage 2 disease (aOR = 2.29, 95% CI 1.57–3.34).

Discussion

Over 40% of women participating in the Partners Demonstration Project reported being pregnant or currently trying to conceive during their first year in the trial, yet less than half of those women reported using a safer conception strategy, including among those with a pregnancy and/or immediate fertility desires. Importantly, our results capture women’s perceptions of their use of safer conception strategies, which encompasses their fertility intention and their perception of using a strategy for prevention during pregnancy attempts. In the primary analysis from this cohort, PrEP use and ART use were very high13 and may not have been recognized as providing protection from HIV-1 transmission during pregnancy attempts specifically, as it was providing general HIV-1 protection, regardless of pregnancy intention. Timed-condomless sex and ARV-based strategies were the most commonly reported safer conception strategies. Women were more likely to report use of a safer conception strategy at their annual visit if they also reported discussing fertility desires with their partner, had intentions to conceive a child, were the HIV-uninfected partner, did not earn income or have children, or were (or their partner was) HIV-infected with a WHO stage of 2.

ART and STI treatment are already recommended for HIV-1 serodiscordant couples regardless of fertility intentions. Since pregnancy attempts necessitate condomless sex, this is an ideal period for time-limited use of PrEP, either in conjunction with additional strategies or as the primary prevention strategy to substitute for condom use and when their partner recently initiated or ART has a known detectable HIV-1 viral load. Studies have shown that concurrent use of PrEP and ART may not be cost-effective (Letchumanan et al., 2015; Ping et al., 2013). However, concurrent usage may be appropriate when HIV-uninfected individuals prefer self-controlled prevention (Hoffman et al., 2015). Among HIV-uninfected partners who recognized use of PrEP as a safer conception strategy, acceptability was >80% for both men and women. This acceptability may be higher than in the general population, as these participants had enrolled in a study that encouraged use of ART and PrEP among known high-risk HIV serodiscordant couples.

In the Partners Demonstration Project, participants were asked about their fertility desires during quarterly visits. Asking about fertility desires routinely at medical appointments is easily integrated into existing workflows and provides an opening for discussion of safer conception methods. Importantly, it also normalizes the idea that couples and individuals affected by HIV have a right to satisfy their fertility desires, including having biological children. Women wanting to delay or avoid pregnancy often do not use effective contraception and fertility desires can change rapidly. Clinician counseling about fertility desires is one way to improve uptake of effective, reversible contraception when pregnancy is not immediately desired and promote women and men’s empowerment to plan pregnancy and family building. Initiating clinician counseling could be accomplished with a simple question about fertility desires, as was done in this study, or could be part of a more in-depth assessment. Studies have shown that major barriers to safer conception counseling include: clinicians not routinely initiating discussions with patients around fertility desires, a reluctance to provide safer conception knowledge to patients perceived as not being prepared for conception, and gaps in knowledge of safer conception strategies (Rahangdale, Richardson, Carda-Auten, Adams, & Grodensky, 2014; West et al., 2015). A more recent study in Uganda showed that even when those barriers are removed, a lack of training on how to counsel patients about safer conception can be a barrier (Matthews et al., 2015). Thus, clinician training would be a key aspect of successful programs (Brown et al., 2016).

Women who were HIV-uninfected reported having used safer conception methods at similar rates to women who were HIV-infected. This difference may not hold true outside of the study. These women knew they were in an HIV-1 serodiscordant partnership, joined a study that sought to reduce HIV transmission, and received care from providers who knew the HIV-1 status of both partners. Regardless of HIV-serostatus, women and men in high-prevalence areas should receive information about safer conception and our data are promising in demonstrating that HIV-uninfected women do act on the information they are given.

Strengths of the study include the outcome being a self-recognized usage of a safer conception strategy, as participants were not prompted with a list of safer conception methods when asked about knowledge, acceptability, or usage. Therefore, we can be more confident in the reliability of self-report by women about safer conceptions methods. Future research may use pharmacy or medical records to identify women who do not self-identify as using safer conception strategies and reduce bias due to self-report. However, we do not have baseline data for the safer conception questions, so we cannot draw any conclusions about changes in knowledge or acceptability of safer conception strategies or know if the safer conception strategies used occurred during or before the study. Additionally, due to the pragmatic nature of the study, a demonstration project, the experiences of participants may vary and do reflect the local and national HIV services (e.g. HIV-infected partners were referred to local clinics for ART). The population enrolled in this study may be more engaged in their medical care and may be more likely to seek out knowledge and opportunities to receive safer conception counseling.

Communication with providers and within couples is important for the successful uptake of safer conception strategies among HIV-1 serodiscordant couples. Clinicians were trained on safer conception as a concept and on specific strategies, but there was no algorithm to guide clinician recommendations or safer conception counselling and providers may have prioritized different messages within and between sites. The disconnect between actual use of PrEP and ART and reporting use of these methods as safer conception strategies, highlights an opportunity for their promotion as safer conception strategies. Fertility desires can change rapidly and repeated discussions about fertility desires and HIV-risk reduction during pregnancy attempts are important to have with all women of childbearing age in areas with high HIV prevalence. ART or PrEP as safer conception strategies along with self-insemination and timed condomless sex were the most known and acceptable options and are also less expensive and more widely available than medically-assisted methods, such as sperm washing and artificial insemination (Zafer et al., 2016). Programs seeking to support these couples to attain fertility goals can provide opportunities for individuals and couples to talk about their fertility desires, normalize these desires and feelings, and foster communication within couples about safer conception practices.

Table 2.

Correlates of women reporting having used at least one safer conception strategy at the 1-year visit (N =859)

| Unadjusted | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) | OR (95% CI) |

p- value |

OR (95% CI) |

p-value | |

| Female partner’s HIV-status | |||||

| HIV-infected | 175/569 (30.8) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | --- |

| HIV-uninfected | 99/290 (34.1) | 1.17 (0.86–1.58) | 0.3 | 1.26 (0.87–1.80) | 0.220 |

| Male partner’s age | |||||

| <24 years | 44/113 (38.9) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | --- |

| 25–29 years | 60/204 (29.4) | 0.65 (0.40–1.06) | 0.08 | 0.66 (0.35–1.25) | 0.205 |

| 30–34 years | 69/187 (36.9) | 0.92 (0.57–1.48) | 0.7 | 1.61 (0.82–3.15) | 0.165 |

| 35+ years | 101/355 (28.5) | 0.62 (0.40–0.97) | 0.04 | 1.19 (0.60–2.34) | 0.619 |

| Female partner’s age | |||||

| <24 years | 118/307 (38.4) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | --- |

| 25–29 years | 75/238 (31.5) | 0.74 (0.52–1.05) | 0.09 | 0.93 (0.56–1.54) | 0.767 |

| 30–34 years | 43/146 (29.5) | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) | 0.06 | 0.95 (0.51–1.74) | 0.863 |

| 35+ years | 38/168 (22.6) | 0.47 (0.31–0.72) | <0.01 | 0.71 (0.36–1.39) | 0.321 |

| Self-earned income | |||||

| Yes | 148/544 (27.2) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | --- |

| No | 126/315 (40.0) | 1.78 (1.33–2.39) | <0.01 | 2.19 (1.50–3.20) | <0.001 |

| Living children | |||||

| Yes (1+) | 190/672 (28.3) | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | |

| None | 84/187 (44.9) | 2.07 (1.48–2.89) | <0.01 | 2.18 (1.34–3.54) | 0.001 |

| Living children with study partner* | |||||

| Yes (1+) | 108/399 (27.1) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | ||

| None | 166/460 (36.1) | 1.52 (1.13–2.04) | <0.01 | ||

| Unprotected sex with study partner in month prior | |||||

| None | 72/273 (26.4) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| Yes (1+) | 202/586 (34.5) | 1.66 (1.22–2.26) | <0.01 | 1.27 (0.87–1.85) | 0.208 |

| Contraceptive usage | |||||

| Highly effective method | 52/239 (21.8) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| None | 222/620 (35.8) | 2.01 (1.42–2.84) | <0.01 | 1.28 (0.83–1.96) | 0.265 |

| WHO staging | |||||

| Stage 1 | 163/591 (27.6) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| Stage 2 | 111/268 (41.4) | 1.86 (1.37–2.51) | <0.01 | 2.29 (1.57–3.34) | <0.001 |

| CD4 count | |||||

| <250 | 54/187 (28.9) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | ||

| 250–499 | 100/318 (31.5) | 1.13 (0.76–1.68) | 0.5 | ||

| 500+ | 119/352 (33.8) | 1.26 (0.86–1.85) | 0.2 | ||

| Viral load (copies/ul) | |||||

| <50 | 10/43 (23.3) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | ||

| 50–9,999 | 70/197 (35.5) | 1.82 (0.85–3.91) | 0.1 | ||

| 10,000–99,999 | 139/387 (35.9) | 1.85 (0.88–3.87) | 0.1 | ||

| 100,000+ | 54/219 (24.7) | 1.08 (0.50–2.34) | 0.8 | ||

| Perceived risk of HIV transmission | |||||

| None | 74/250 (29.6) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | ||

| Low-Medium | 110/360 (30.6) | 0.95 (0.63–1.46) | 0.9 | ||

| High | 50/118 (42.4) | 1.28 (0.73–2.25) | 0.87 | ||

| Unsure | 40/131 (30.5) | 1.12 (0.64–1.96) | 0.4 | ||

| Fertility desires during the first year | |||||

| None | 24/177 (15.1) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | --- |

| Currently trying/pregnant | 176/366 (48.0) | 5.91 (3.67–9.51) | <0.01 | 7.14 (3.90–13.06) | <0.001 |

| In the future | 74/316 (23.4) | 1.95 (1.18–3.22) | <0.01 | 1.60 (0.91–2.83) | 0.101 |

| Discussed fertility desires with partner | |||||

| No | 39/201 (19.4) | 1.00 (ref.) | --- | 1.00 (ref.) | --- |

| Yes | 235/656 (35.8) | 2.31 (1.58–3.41) | <0.01 | 1.80 (1.13–2.86) | 0.013 |

Excluded from multivariate model due to collinearity with the more general living children variable

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development under Grants K99HD076679 and R00HD076679; the National Institute of Mental Health of the US National Institutes of Health under Grant R01 MH095507; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation under Grant OPP105605; and the US Agency for International Development under cooperative agreement AID-OAA-A-12-00023.

We thank the couples who participated in this study for their motivation and dedication, and the referral partners, community advisory groups, institutions, and communities that supported this work.

Partners Demonstration Project Team

Coordinating Center (University of Washington) and collaborating investigators (Harvard Medical School, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts General Hospital): Jared Baeten (protocol chair), Connie Celum (protocol co-chair), Renee Heffron (project director), Deborah Donnell (statistician), Ruanne Barnabas, Jessica Haberer, Harald Haugen, Craig Hendrix, Lara Kidoguchi, Mark Marzinke, Susan Morrison, Jennifer Morton, Norma Ware, Monique Wyatt.

Project sites:

Kabwohe, Uganda (Kabwohe Clinical Research Centre): Stephen Asiimwe, Edna Tindimwebwa

Kampala, Uganda (Makerere University): Elly Katabira, Nulu Bulya

Kisumu, Kenya (Kenya Medical Research Institute): Elizabeth Bukusi, Josephine Odoyo

Thika, Kenya (Kenya Medical Research Institute, University of Washington): Nelly Rwamba Mugo, Kenneth Ngure

Data Management was provided by DF/Net Research, Inc. (Seattle, WA). PrEP medication was donated by Gilead Sciences.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion number 313, September 2005. The importance of preconception care in the continuum of women's health care. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005;106(3):665. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200509000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten J, Heffron R, Kidoguchi L, Mugo N, Katabira E, Bukusi E, Celum C. Near elimination of HIV transmission in a demonstration project of PrEP and ART. Presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, USA. 2015. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Njoroge B, Akama E, Breitnauer B, Leddy A, Darbes L, Mmeje O. A novel safer conception counseling toolkit for the prevention of HIV: A mixed-methods evaluation in Kisumu, Kenya. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2016;28(6):524–538. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.6.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciaranello A, Matthews L. Safer Conception Strategies for HIV-Serodiscordant Couples: How Safe Is Safe Enough? The Journal of infectious diseases. 2015;212(10):1525–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohan D, Weber S, Goldschmidt R. Safer conception options for HIV-serodiscordant couples. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;206(1):e21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.014. author reply e21–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Chen Y, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour M, Kumarasamy N Team, H. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle K, Stephenson R, Karita E, Chomba E, Kayitenkore K, Vwalika C, Allen S. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. The Lancet. 2004;371(9631):2183–2191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman R, Jaycocks A, Vardavas R, Wagner G, Lake J, Mindry D, Landovitz R. Benefits of PrEP as an Adjunctive Method of HIV Prevention During Attempted Conception Between HIV-uninfected Women and HIV-infected Male Partners. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2015;212(10):1534–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle E, Hughes J, Lingappa J, John-Stewart G, Celum C, Nakku-Joloba E the Teams, P. An empiric risk scoring tool for identifying high-risk heterosexual HIV-1-serodiscordant couples for targeted HIV-1 prevention. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2013;62(3):339–47. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e622d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health. National AIDS and STI Control Programme: Guidelines on Use of Antiretrovial Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection. 2014 Retrieved from: https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/tx_kenya_2014.pdf.

- Liao C, Wahab M, Anderson J, Coleman JS. Reclaiming fertility awareness methods to inform timed intercourse for HIV serodiscordant couples attempting to conceive. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(1):19447. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letchumanan M, Coyte P, Loutfy M. An economic evaluation of conception strategies for heterosexual serodiscordant couples where the male partner is HIV-positive. Antiviral therapy. 2015;20(6):613–21. doi: 10.3851/imp2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews LT, Bajunirwe F, Kastner J, Sanyu N, Akatukwasa C, Ng C, Bangsberg DR. “I Always Worry about What Might Happen Ahead”: Implementing Safer Conception Services in the Current Environment of Reproductive Counseling for HIV-Affected Men and Women in Uganda. BioMed Research International, 2016. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4195762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mmeje O, Cohen C, Cohan D. Evaluating Safer Conception Options for HIV-Serodiscordant Couples (HIV-Infected Female/HIV-Uninfected Male): A Closer Look at Vaginal Insemination. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/587651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujugira A, Heffron R, Celum C, Mugo N, Nakku-Joloba E, Baeten J Team, P. Fertility intentions and interest in early antiretroviral therapy among East African HIV-1-infected individuals in serodiscordant partnerships. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2013;63(1):e33–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318288bb32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngure K, Baeten J, Mugo N, Curran K, Vusha S, Heffron R, Shell-Duncan B. My intention was a child but I was very afraid: fertility intentions and HIV risk perceptions among HIV-serodiscordant couples experiencing pregnancy in Kenya. AIDS care. 2014;26(10):1283–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.911808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngure K, Mugo N, Celum C, Baeten J, Morris M, Olungah O, Shell-Duncan B. A qualitative study of barriers to consistent condom use among HIV-1 serodiscordant couples in Kenya. AIDS care. 2012;24(4):509–16. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.613911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping L-H, Jabara C, Rodrigo A, Hudelson S, Piwowar-Manning E, Wang L, Swanstrom R. HIV-1 transmission during early antiretroviral therapy: evaluation of two HIV-1 transmission events in the HPTN 052 prevention study. PloS one. 2013;8(9):e71557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintye J, Ngure K, Curran K, Vusha S, Mugo N, Celum C, Heffron R. Fertility Decision-Making Among Kenyan HIV-Serodiscordant Couples Who Recently Conceived: Implications for Safer Conception Planning. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2015;29(9):510–6. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piot P, Bartos M, Larson H, Zewdie D, Mane P. Coming to terms with complexity: a call to action for HIV prevention. Lancet (London, England) 2008;372(9641):845–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahangdale L, Richardson A, Carda-Auten J, Adams R, Grodensky C. Provider Attitudes toward Discussing Fertility Intentions with HIV-Infected Women and Serodiscordant Couples in the USA. Journal of AIDS & clinical research. 2014;5(6):1000307. doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Bassett J, Sanne I, Phofa R, Yende N, Rie A. Implementation of a safer conception service for HIV-affected couples in South Africa. AIDS (London, England) 2014;28(Suppl 3):S277–85. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Ministry of Health. Addendum to the National Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines. 2013 Retrieved from: https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/tx_uganda_add_to_art_2013.pdf.

- Weber S, Waldura J, Cohan D. Safer conception options for HIV serodifferent couples in the United States: the experience of the National Perinatal HIV Hotline and Clinicians’ Network. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2013;63(4):e140–1. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182948ed1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West N, Schwartz S, Phofa R, Yende N, Bassett J, Sanne I, Rie A. “I don’t know if this is right … but this is what I'm offering”: healthcare provider knowledge, practice, and attitudes towards safer conception for HIV-affected couples in the context of Southern African guidelines. AIDS care. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1093596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying R, Sharma M, Heffron R, Celum C, Baeten J, Katabira E, Barnabas R. Cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis targeted to high-risk serodiscordant couples as a bridge to sustained ART use in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2015;18(4 Suppl 3):20013. doi: 10.7448/ias.18.4.20013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafer M, Horvath H, Mmeje O, van der Poel S, Semprini AE, Rutherford G, Brown J. Effectiveness of semen washing to prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission and assist pregnancy in HIV-discordant couples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertility and sterility. 2016;105(3):645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]