Abstract

A thiol-thioester exchange system has been used to measure the propensities of diverse β-amino acid residues to participate in an α-helix-like conformation. These measurements depend on formation of a parallel coiled-coil tertiary structure when two peptide segments become linked by thioester formation. One peptide segment contains a “guest” site that accommodates diverse β residues and is distal to the coiled-coil interface. We find that helix propensity is influenced by side chain placement within the β residue [β3 (side chain adjacent to nitrogen) slightly favored relative to β2 (side chain adjacent to carbonyl)]. The previously recognized helix stabilization resulting from five-membered ring incorporation is quantified. These results are significant because so few quantitative thermodynamic measurements have been reported for α/β-peptide folding.

The α-helix is the most common regular secondary structure within globular proteins, and this situation has inspired many efforts to establish quantitative α-helix propensity scales for the 20 proteinogenic residues.1 Polypeptides containing mixtures of α- and β-amino acid residues, with up to 33% β residues evenly distributed along the backbone, can adopt α-helix-like conformations.2 These α-helix-mimetic α/β-peptides can engage binding sites on proteins that evolved to recognize α-helical ligands, leading to inhibition of specific protein-protein interactions or activation of cell-surface receptors.3 The presence of β residues blocks recognition by proteases and immune receptors, which raises the prospect of biomedical utility.4 Bioactive α/β-peptides have been generated via solid-phase synthesis to date, but prospects for accessing such peptides via biosynthetic machinery are steadily improving.5 In light of these developments, it would be valuable to establish a thermodynamic scale for the propensities of β residues to reside in an α-helix-like secondary structure; we report such a scale here.

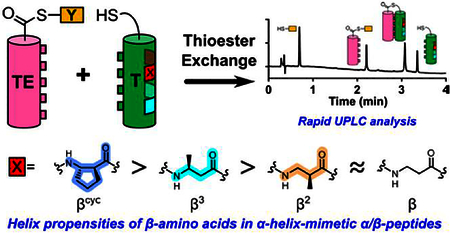

Among α residues, variations in α-helix propensity arise largely from variations in the side chain.6 There is a richer landscape of possibilities among β residues because side chains can be placed adjacent to nitrogen (β3 residues), adjacent to carbonyl (β2 residues), or at both positions (β2,3 residues). β2,3 residues can contain rings, with variable size and stereochemistry. To survey this range of β residue substitution patterns, we turned to a propensity assessment strategy based on thiol-thioester exchange (Figure 1).

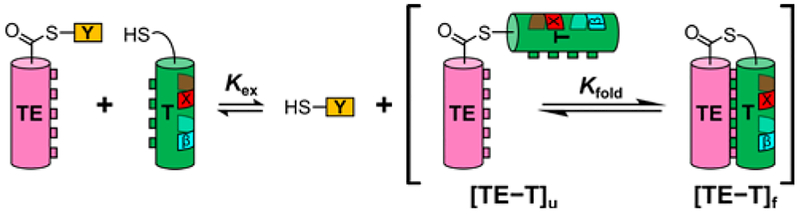

Figure 1.

Cartoon of thioester exchange experiment. X indicates position of guest residue, the helix propensity of which can be evaluated. “β” Indicates a β residue kept constant for all T peptides. [TE−T]u and [TE−T]f indicate folded and unfolded states of the coiled-coil-forming full-length thiodepsipeptide, respectively. Although the cylinders shown for the T and TE segments imply helicity, these segments undoubtedly explore both helical and non-helical conformations, particularly with are not directly associated, as in [TE−T]f.

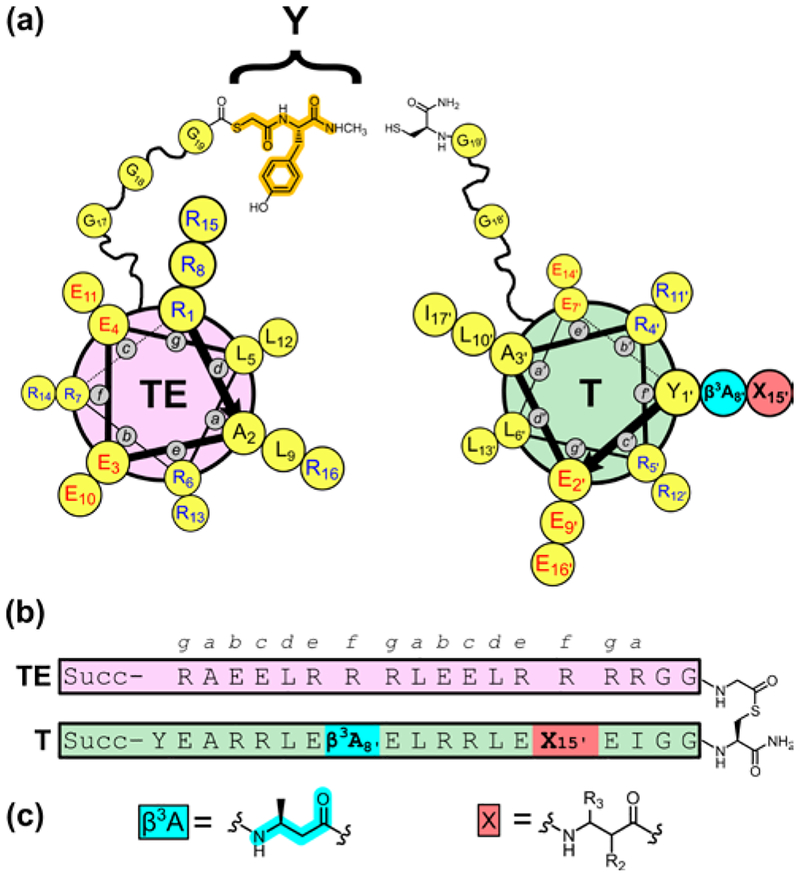

The experimental design is based on our recent strategy for measuring α-helix propensities of α residues via thioester exchange (Figure 2).7 Two helix-forming segments of 16–17 residues each are linked in parallel by a flexible segment that contains a thioester bond. One segment (TE) provides the acyl group, and the other (T) provides the thiol (Cys side chain) for the thioester bond.8 Each peptide sequence features a heptad repeat motif, with hydrophobic residues at positions a and d of each repeat to encourage intramolecular coiled coil formation. Adoption of an α-helix (or α-helix-like) conformation by each peptide segment is encouraged by the placement of Arg and Glu residues at many positions other than a and d to allow intrahelical salt bridges. Upon intramolecular parallel coiled coil formation, Arg residues at e and g positions of the TE segment make interhelical salt bridges with Glu residues at e and g positions of the T segment.

Figure 2.

(a) Helix-wheel diagram of thioester peptide TE, with fragment derived from small thiol Y highlighted in orange, and thiol α/β-peptide T. Guest β residue position X is highlighted in red. (b) Sequence of full-length thiodepsipeptide TE−T. Succ = succinyl. (c) Structures of β3hAla, at position 8’ in all T α/β-peptides, and general structure of β residues tested at position 15′.

When the small tyrosine-derived thiol Y is present in addition to the TE−T thiodepsipeptide, a thiol-thioester exchange reaction occurs. The equilibrium constant for the folding process (Kfold), i.e., for interconversion between the unfolded state of TE−T and the parallel coiled-coil tertiary structure, can be determined from the thiol-thioester equilibrium constant (Kex), which is measured via HPLC. ΔGfold, calculated from Kfold, provides the basis for a propensity scale. Control studies indicate that these ΔGfold values depend on intramolecular coiled-coil interactions between the T and TE segments, as required by our experimental design.9

Our previous study demonstrated that the identity of α residues at f positions in the T segment influences ΔGfold as expected based on established α-helix propensity scales, so long as the “guest” residue side chain is not ionized.7 The good correlation between our thermodynamic scale and α-helix propensity scales derived by other methods supports our design hypothesis that guest residues in f positions of the T segment do not contact the TE segment in the helix-loop-helix tertiary structure (folded state). These findings provide a foundation for using the TE−T system to measure β residue propensities to reside in an α-helix-like conformation. A first step toward that goal, involving the T variant containing β3-homoalanine (β3-hAla) at two f positions, indicated that a β3-hAla residue within an α-helix-like conformation is 0.6 kcal/mol less favorable than an Ala residue within an α-helix.7

The new studies employ the version of T containing β3-hAla at two f positions as the point of reference. We monitor changes in ΔGfold as the β residue is altered at just one position; the other f position remains β3-hAla. This design isolates the impact of altering β residue substitution at a single site within a constant α/β backbone. For the reference peptide, with β3-hAla at the “guest” position, ΔGfold =−0.87 kcal/mol.7 A critical test of our design hypothesis involves the derivative of this reference peptide with Leu13’→Asn, for which ΔGfold=+0.17 kcal/mol. This d position should participate in the coiled-coiled interface, and Leu→Asn should therefore substantially diminish ΔGfold if folding depends upon intramolecular coiled-coil formation, as intended. The large destabilization that we observe to result from the Leu13’→Asn modification supports our assumption that a coiled coil-like association is retained when β residues are placed at f positions in the T segment, and intramolecular interactions between T and TE segments involve helical conformations of both segments.

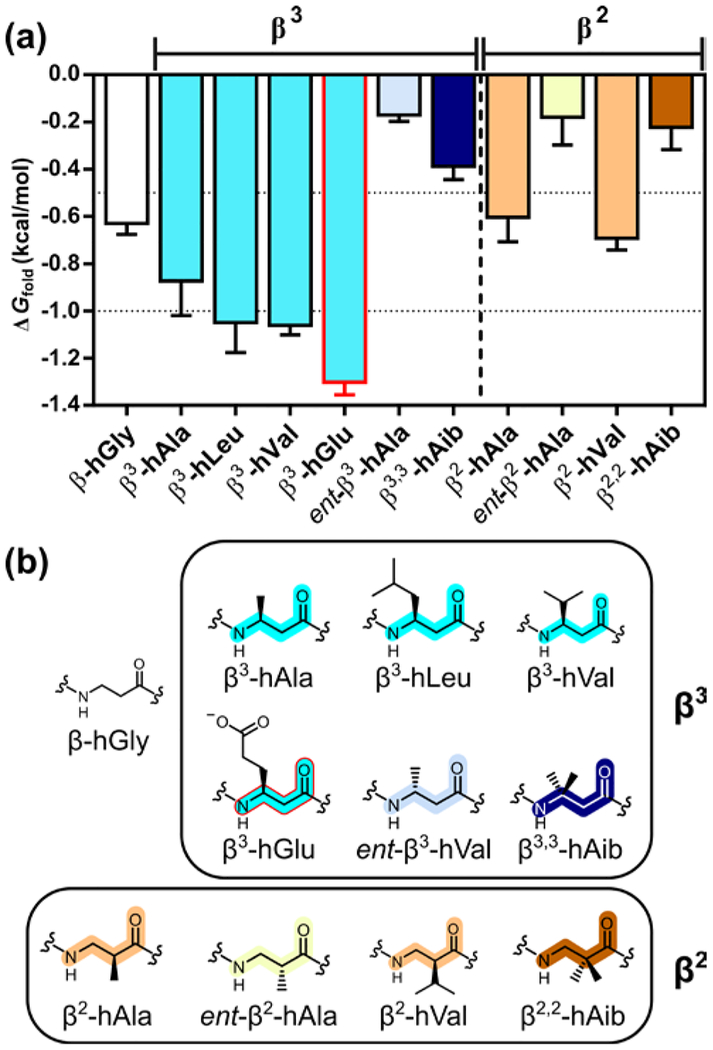

A first set of measurements evaluated variations in β3 residue side chain (Figure 3). Removal of the methyl side chain, to generate β-hGly, was slightly destabilizing (Table 1).7 Enlarging the side chain, by replacing β3-hAla with either β3-hLeu or β3-hVal, seemed to cause a slight enhancement in helical propensity. The thermodynamic similarity we observe for β3-hLeu and β3-hVal in an α-helix-like conformation (Table 1) contrasts with the trend in proteins, where Leu has a significantly higher α-helix propensity than does Val.1 In general, side chain branching adjacent to the backbone is unfavorable for an α-helix, but this trend is not retained for β residues in an α-helix-like conformation. β3-hGlu appears to display a significantly higher helix propensity relative to β3-hAla, behavior we attribute to favorable intrahelical Coulombic interactions of the anionic β3-hGlu side chain with spatially proximal cationic Arg side chains in the folded state (positions b and c).10 A similar effect was observed for Glu in the guest sites of the analogous α-helical system.7

Figure 3.

(a) Thioester exchange-derived ΔGfold values for α/β-peptides containing a β3- or β2-homoamino acid guest residue. (b) Structures of β3- and β2-homoamino acids.

Table 1.

ΔGfold Measured by Thioester Exchange for Thiol Peptides Containing β-Amino Acid Guest Residuesa

| β Residue Class | Guest residue | ΔGfold (kcal/mol)b |

|---|---|---|

| β3 | βhGly | −0.63 ± 0.05 |

| β3-hAla | −0.87 ± 0.15 | |

| β3-hAla(Asn)c | 0.17 ± 0.15 | |

| β3-hLeu | −1.05 ± 0.13 | |

| β3-hVal | −1.06 ± 0.04 | |

| β3-hGlu | −1.30 ± 0.05 | |

| ent-β3-hAla | −0.17 ± 0.03 | |

| β3,3-hAib | −0.39 ± 0.06 | |

| β2 | β2-hAla | −0.60 ± 0.10 |

| ent-β2-hAla | −0.18 ± 0.12 | |

| β2-hVal | −0.69 ± 0.05 | |

| β2,2-hAib | −0.22 ± 0.09 | |

| β2,3 | ACPC | −1.40 ± 0.08 |

| ACPC(Asn)c | −0.18 ± 0.06 | |

| β2,3-hAla | −0.50 ± 0.04 | |

| ent-ACPC | −0.11 ± 0.07 | |

| (2R,3S)-ACPC | −0.51 ± 0.02 | |

| ACHC | −0.97 ± 0.03 | |

| ATC | −1.30 ± 0.04 | |

| gAPC | −1.23 ± 0.07 | |

| spAPC | −1.81 ± 0.08 |

ΔGfold = −RT ln(Kfold). Guest residue position within T is defined in Figure 2. Conditions: 50 μM each TE and T, 50 mM phosphate, pH 7.0, 2 mM TCEP, room temperature.

Mean ± standard deviation of at least five experiments.

Leu→Asn substitution at coiled-coil interfacial residue 13′ of T.

All β3 residues mentioned so far are enantiospecifically derived from the corresponding L-α-amino acids (S configuration) with retention of configuration. Inversion of configuration (ent-β3-hAla) leads to a decline in helix propensity of ≈0.7 kcal/mol, which is qualitatively consistent with but smaller than the decline in α-helix propensity reported for D-Ala (R configuration) relative to L-Ala.1b,7 The Aib residue (gem-dimethyl substitution) has an α-helix propensity larger than that of Ala,1b,11 but β3,3-hAib mani-fests a significantly lower helix propensity relative to β3-hAla.

We evaluated β2 residues, in which the side chain position is shifted relative to β3 residues. The S configuration of β2-hAla is thermodynamically preferred relative to the R configuration in the guest position, which supports previous assumptions.12 The difference in helical propensity between the two configurations, ≈0.4 kcal/mol, is smaller than for the two configurations of β3-hAla.

Our results suggest a small decline in helix propensity for β2 residues relative to β3 isomers (β-hAla and β-hVal, Table 1). No significant difference could be detected between the helix propensities of β2 and β3 residues in the only previous quantitative com parison, which involved solvent-exposed helical sites within a tertiary structure. 12

Side chain branching adjacent to the backbone has little impact on the helix propensity of β2 residues (β2-hAla vs. β2-hVal), which parallels the trend among β3 residues. The lower helix propensity of β2,2-hAib relative to β2-hAla represents another parallel with the β3 series.

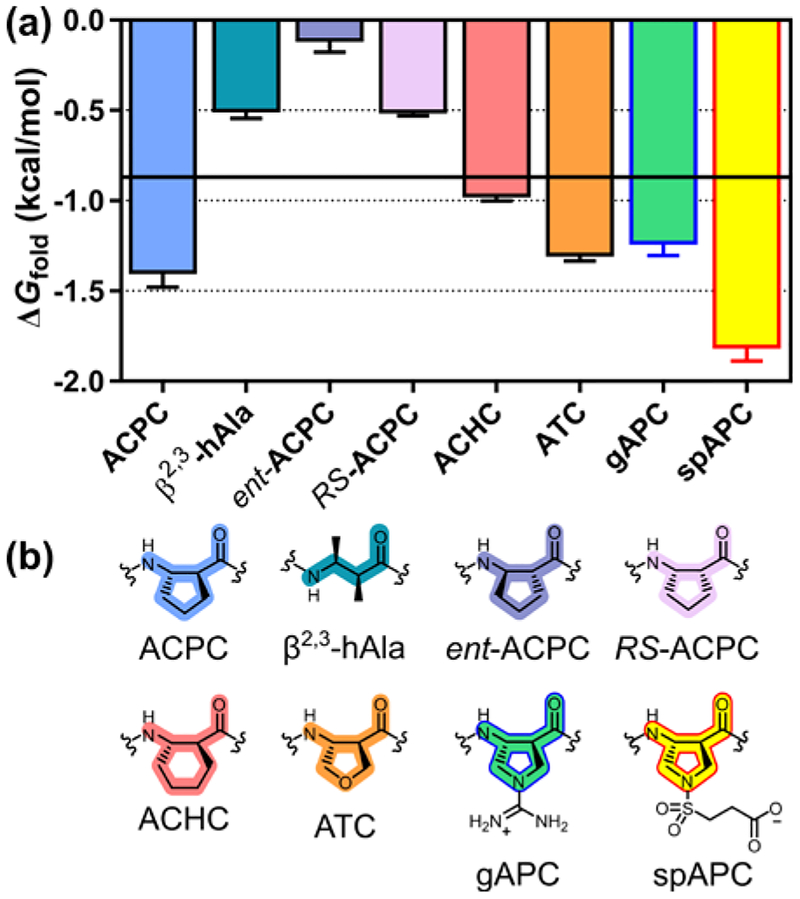

Previous comparisons have suggested that cyclic β residues with a five-membered ring constraint manifest enhanced helix propensity relative to β3 residues.2,13–15 (S,S)-Trans-2-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid (ACPC) exemplifies these helix-prone β-amino acids. We observe ≈0.5 kcal/mol enhancement in helix propensity for ACPC relative to β3-hAla (Figure 4). In a critical control experiment, we find that Leu13’→Asn leads to ≈1.2 kcal/mol destabilization with ACPC at the guest site, which suggests that intended coiled coil-like tertiary packing between the TE and T segments is maintained when a cyclic β residue is placed at the guest position. Since replacing Ala with β3-hAla leads to a 0.6 kcal/mol decline in helix stability,7 our findings indicate that replacing β3-hAla with (S,S)-ACPC largely restores helix stability to the pure α backbone level.

Figure 4.

(a) Thioester exchange-derived ΔGfold values for α/β-peptides containing a β2,3-disubstituted β-amino acid guest residue. Horizontal bar represents ΔGfold for β3-hAla. (b) Structures of β2,3-disubstituted β-amino acids.

The (S,S)-β2,3-dimethyl residue, an acyclic analogue of (S,S)-ACPC, has a helix propensity ≈0.9 kcal/mol less favorable than that of (S,S)-ACPC. This observation may reflect unfavorable gauche interactions between the methyl side chains in the helical conformation. (R,R)-ACPC displays a much lower helix propensity relative to (S,S)-ACPC (ΔΔG ≈1.3 kcal/mol), as expected for a peptide composed largely of L-α residues. cis-(2R,3S)-ACPC also has a low helix propensity, ≈0.9 kcal/mol less favorable relative to (S,S)-ACPC. Six-membered ring constraint, as in (S,S)-trans-2-aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid (ACHC), leads to a ≈0.4 kcal/mol decrease in helix propensity relative to the five-membered ring constraint in ACPC.

Several analogues of (S,S)-ACPC bearing polar functionality in the ring were evaluated. The neutral ATC residue16 (tetrahydrofuran ring) manifests a propensity similar to that of ACPC, as does an analogue bearing a positive charge (gAPC).17 In contrast, an analogue bearing a negative charge (spAPC)18 displays a substantially higher propensity. The high helix propensity observed for the anionic spAPC residue parallels high propensities observed for β3-hGlu as guest; we propose that favorable intrahelical Coulombic interactions with proximal cationic side chains (Arg) in the folded state explain this trend. The apparent lack of unfavorable Coulombic interactions with the cationic gAPC side chain might reflect the fact that the position of the charge is tightly constrained in this case.

Quantitative information on helix propensities for β-amino acid residues has been very limited to date,13 and there is no precedent for the range of substitution patterns that we have evaluated here. Circular dichroism signatures of the α/β-peptide helices described above are qualitatively consistent with the thioester exchange data.9

Atomic-resolution data demonstrate that various residue combinations with α:β proportions between 3:1 and 4:1 support adoption of α-helix-like secondary structure.2,3 Structural mimicry has been documented also at lower substitution levels, including single-site replacements.12,14,15 The backbone torsion angles of the β residues are relatively constant among these α/β-peptide helices, despite the variation in α:β proportion and distribution. We therefore expect that the trends in β residue propensity reported here will be generally applicable to α/β-peptides that adopt α-helix-like conformations; however, additional studies will be required to test this prediction. α-Helix-mimetic α/β-peptides display properties of considerable interest from a biomedical perspective,2–4 and the thermodynamic data presented here should support efforts to refine α/β-peptide candidates for specific applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation (CHE-1565810). The authors thank Dr. Young-Hee Shin for providing small thiol Y and Dr. Dale F. Kreitler for providing Fmoc-protected ATC.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Experimental details including amino acid synthesis data, peptide synthesis procedures, thioester exchange UPLC chromatograms. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Padmanabhan S; Marqusee S; Ridgeway T; Laue TM; Baldwin RL, Nature 1990, 344, 268; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) O’Neil KT; DeGrado WF, Science 1990, 250, 646; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Horovitz A; Matthews JM; Fersht AR, J. Mol. Biol 1992, 227, 560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson LM; Gellman SH, Methods Enzymol 2013, 523, 407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Checco JW; Gellman SH, Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 2016, 39, 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Gopalakrishnan R; Frolov AI; Knerr L; Drury WJ 3rd; Valeur E, J. Med. Chem 2016, 59, 9599; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Werner HM; Horne SW, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2015, 28, 75; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Olson KE; Kosloski-Bilek LM; Anderson KM; Diggs BJ; Clark BE; Gledhill JM; Shandler SJ; Mosely RL; Gendelman HE J. Neurosci 2015, 35, 16463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Maini R; Nguyen DT; Chen S; Dedkova LM; Chowdhury SR; Alcala-Torano R; Hecht M, Bioorg. Med. Chem 2013, 21, 1088; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fujino T; Goto Y; Suga H; Murakami H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 1962; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Czekster CM; Robertson WE; Walker AS; Söll D; Schepartz AJ Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Niquille DL; Hansen DA; Mori T; Fercher D; Kries H; Hilvert D, Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 282; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Morinaka BI; Lakis E; Verest M; Helf MJ; Scalvenzi T; Vagstad AL; Sims J; Sunagawa S; Gugger M; Piel J, Science 2018, 359, 779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fairman R; Anthony-Cahill SJ; DeGrado WF, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 5458. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher BF; Hong SH; Gellman SH, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 13292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinkruger JD; Woolfson DN; Gellman SH J. Am Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. See Supporting Information.

- 10.Marqusee S; Baldwin RL, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 8898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Filippis V; De Antoni F; Frigo M; de Laureto PP; Fontana A, Biochemistry 1998, 37, 1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavenor NA; Reinert ZE; Lengyel GA; Griffith BD; Horne WS, Chem. Commun 2016, 52, 3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price JL; Hadley EB; Steinkruger JD; Gellman SH, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49, 368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinert ZE; Horne WS, Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreitler DF; Mortenson DE; Forest KT; Gellman SH J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imamura Y; Umezawa N; Osawa S; Shimada N; Higo T; Yokoshima S; Fukuyama T; Iwatsubo T; Kato N; Tomita T; Higuchi TJ Med. Chem 2013, 56, 1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demizu Y; Oba M; Okitsu K; Yamashita H; Misawa T; Tanaka M; Kurihara M; Gellman SH, Org. Biomol. Chem 2015, 13, 5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HS; Syud FA; Wang X; Gellman SH, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 7721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.