Abstract

Xylanase is commonly added to pig diets rich in arabinoxylans to promote nutrient utilization and growth. However, high doses of xylanase could release high amounts of xylose in the upper gut, which could have negative nutritional and metabolic implications. However, the amount of xylose to elicit such adverse effects is not clear. Thus, two experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of dietary xylose on the growth performance and portal-drained viscera (PDV) fluxes of glucose (GLU), urea-N (BUN), insulin production, and O2 consumption in growing pigs. In Exp. 1, 64 pigs (21.4 ± 0.1 kg BW), housed as either two barrows or gilts per pen (eight pens per diet) were used to determine the effects of increasing levels of D-xylose (0, 5, 15, and 25%) in a corn–soybean meal–cornstarch-based diet on pig growth performance in a 28-d trial. Cornstarch was substituted for D-xylose (wt/wt) in the control diet. BW and feed intake were monitored weekly. D-xylose linearly reduced (P < 0.05) final BW, ADG, and G:F but not ADFI. However, final BW, ADG, and G:F of pigs fed 15% D-xylose did not differ from pigs fed 0% D-xylose. Thus, the results suggested that pigs could tolerate up to 15% dietary D-xylose. In Exp. 2, six gilts (22.8 ± 1.6 kg BW), fitted with permanent catheters in the portal vein, ileal vein, and carotid artery, were fed the 0% and 15% D-xylose diets at 4% of their BW once daily at 0900 h for 7 d in a cross-over design (six pigs per diet). On d 7, pigs were placed in indirect calorimeters to measure whole-animal O2 consumption and sample blood simultaneously for 6 h from the portal vein and carotid artery after feeding to assay GLU, O2, BUN, and insulin concentrations. Net portal nutrients and insulin production were calculated as porto-arterial concentration differences × portal blood flow (PBF) rate, whereas PDV O2 consumption was calculated as arterial-portal O2 differences × PBF. Diet had no effect on postprandial PBF, insulin production, and portal BUN flux and O2 consumption. Pigs fed 0% D-xylose had greater (P < 0.05) postprandial portal and arterial BUN concentrations, and portal GLU concentration and flux than pigs fed 15% D-xylose diet. In conclusion, feeding growing pigs a diet containing 15% D-xylose did not reduce pig performance or affect PDV energetic demand but reduced GLU fluxes.

Keywords: dietary D-xylose, performance, net portal flux, nutrients, pig

INTRODUCTION

Arabinoxylan is a major nonstarch polysaccharide (NSP) in cereal grains and coproducts (Bach Knudsen, 1997). Therefore, xylanase is typically used to target arabinoxylans to mitigate some of the negative effects of NSP to promote pig growth (Adeola and Cowieson, 2011). Xylanase elicits these beneficial effects by disrupting cell wall polysaccharide to release entrapped nutrients for digestion and degrading complex NSP structures into lower molecular weight components for effective hindgut fermentation to improve the overall energy supply to the pig (Bedford and Cowieson, 2012; Kiarie et al., 2013). However, hydrolysis of arabinoxylans by xylanase could release xylose and arabinose into the pig small intestine (Walsh et al., 2016).

Xylose is present in many feedstuffs and poorly utilized by monogastric animals. Indeed, previous studies in chickens (Wagh and Waibel, 1966; Schutte, 1990) and pigs (Schutte et al., 1991; Verstegen et al., 1997) reported that the ME values reduced when diets contained high concentrations of D-xylose. Further, feeding broiler chickens up to 40% xylose decreased protein and fat digestibility (Peng et al., 2004), whereas high doses of D-xylose severely depleted liver and muscle glycogen (Wagh and Waibel, 1966, 1967; Peng et al., 2004), suggesting energy deprivation. Our recent study in broilers showed that 5% or more D-xylose reduced growth performance and utilization of nutrients linked to changes in hepatic enzymes and transcription factors involved in energy metabolism (Regassa et al., 2017). However, the amount of dietary xylose that could elicit adverse effects in pigs is not clear. Such information would aid in formulating diets with more accurate nutrient specification when xylanase are added to ensure no adverse effects on pig performance. Therefore, an experiment was conducted to investigate the effects of increasing dietary D-xylose on growth performance, portal nutrient fluxes, insulin production, and oxygen (O2) consumption by the portal-drained viscera (PDV) and whole animal in growing pigs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Manitoba Animal Care Committee, and pigs were cared for in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines (CCAC, 2009).

Experimental Diets, Animals, and Design

Two experiments were conducted at the T. K. Cheung Centre for Animal Science Research and the Annex Building of the Department of Animal Science, University of Manitoba.

Experiment 1 was conducted to determine the effects of adding increasing amounts of D-xylose from 0% to 25% in a corn–soybean meal (SBM)–cornstarch-based diet on pig performance in a 28-d trial. Diets were formulated to meet or exceed the NRC (1998) nutrient specifications for growing pigs within the BW range of 20 to 50 kg (Table 1). The control diet contained corn and SBM as the main ingredients and 25% cornstarch. Three additional diets were formulated by substituting cornstarch with pure D-xylose (wt/wt) so that the levels of dietary D-xylose inclusion were 0, 5, 15, and 25%, respectively.

Table 1.

Composition of experimental diets (as fed basis)

| Ingredient (%) | Xylose level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 5% | 15% | 25% | |

| Corn | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 |

| Xylose | — | 5.0 | 15.0 | 25.0 |

| Cornstarch | 25.0 | 20.0 | 10.0 | — |

| Soybean meal, 44% CP | 31.0 | 31.0 | 31.0 | 31.0 |

| Vegetable oil | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Limestone | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Mono calcium phosphate | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Iodized salt | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Vitamin-mineral premix1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Calculated nutrient content2 | ||||

| DM, % | 91.0 | 91.0 | 91.0 | 91.0 |

| DE, kcal/kg | 3,564 | 3,551 | 3,526 | 3,500 |

| CP, % | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 17.0 |

| SID3 | ||||

| Lys, % | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Met, % | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Thr, % | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Trp, % | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| Analyzed chemical composition | ||||

| DM, % | 89.0 | 89.8 | 90.8 | 91.2 |

| GE, kcal/kg | 3,872 | 3,853 | 3,851 | 3,859 |

| CP , % | 16.3 | 16.6 | 17.4 | 16.6 |

1Premix supplied per kilogram of diet: vitamin A, 8,250 IU; vitamin D3, 825 IU; vitamin E, 40 IU; vitamin K, 4 mg; thiamine, 1 mg; riboflavin, 5 mg; niacin, 35 mg; pantothenic acid, 15 mg; vitamin B12, 25 µg; biotin, 200 µg; folic acid, 2 mg; Cu, 15 mg (copper sulfate); I, 0.21 mg as Ca(IO3)2; Fe, 100 mg (ferrous sulfate); Mn, 20 mg (manganese oxide); Se, 0.15 mg (sodium selenite); and Zn, 100 mg (zinc oxide).

2Nutritional composition was calculated based on ingredient composition values from NRC (1998). Digestible energy value of 3,743 kcal/kg was used for D-xylose assuming similar GE and digestibility as glucose (Verstegen et al., 1997).

3SID, standardized ileal digestible.

Sixty-four crossbred ([Yorkshire × Landrace] × Duroc) pigs (32 barrows and 32 gilts) with an average initial BW of 21.4 ± 0.1 kg were obtained from the University of Manitoba Glenlea Swine Research Unit for use in the present study. Pigs were housed in groups of two per pen (same sex) in a temperature-controlled room with the ambient temperature set at 21 ± 2 °C. Each pen (1.5 × 1.2 m) was equipped with a stainless steel feeder, a nipple drinker, plastic-covered expanded metal floors, and a metal wall partitioning that allowed visual contact with pigs in adjacent pens. Pens were assigned at random to the experimental diets such that each diet had eight replicate pens with an equal number of barrows and gilts. Pigs had free access to feed and drinking water throughout the 28-d trial. BW and feed disappearance were determined weekly to calculate ADG, ADFI, and feed efficiency (G:F).

Based on the results of Exp. 1, Exp. 2 was designed to gain more information on dietary xylose effect on nutrient absorption and energetic demand in pigs fed the 0% or 15% D-xylose used for Exp. 1. Six female ([Yorkshire × Landrace] × Duroc) pigs with an average initial BW of 22.8 ± 1.6 kg were surgically fitted with indwelling catheters in the carotid artery and portal and ileal veins as previously described (Agyekum et al., 2016). Pigs were individually housed in pens (1.5 × 1.2 m) with plastic-covered expanded metal sheet flooring equipped with a nipple drinker and a stainless steel feeder in a temperature-controlled room. Pens were partitioned with metal bars that allowed visual contact with pigs in adjacent pens. Pigs were trained to consume 4% of their BW within an hour once daily at 0900 h but had free access to fresh drinking water as described previously (Agyekum et al., 2012).

Pigs were fed one of the two diets for 7 d using a cross-over design to give six replicates per treatment. On the morning of d 7 of each period, pigs were placed in an indirect calorimeter for continuous blood sampling and whole-body O2 consumption measurement for 6 h as described previously (Agyekum et al., 2016) from the portal vein and the carotid artery at 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240 300, and 360 min after feeding. Blood samples were analyzed for concentrations of glucose (GLU), urea nitrogen (BUN), and O2 immediately using a Nova Stat profile M blood gas and electrolyte analyzer (Nova Biomedical Corporation, Waltham, MA). Packed cell volume was determined using the standard centrifugation method (Bull et al., 2000). Thereafter, plasma was recovered by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min.

Laboratory Analysis

Diet samples were analyzed for moisture (method 934.01; AOAC, 1990) to estimate DM, CP (method 968.06; AOAC, 1990) using a Leco NS 2000 Nitrogen Analyzer (Leco Corp., St. Joseph, MI), and GE using a Parr Isoperibol oxygen bomb calorimeter (Parr Instrument Co., Moline, IL). Plasma samples were kept frozen (−80 °C) until required for analysis. Insulin was analyzed using an ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Para-amino hippuric acid (PAH) concentration in plasma was assayed according to the procedure described by Marsilio et al. (1997) using HPLC (Agilent 1100 Series, column model Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 [5 mm, 4.6 × 250 mm]; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Calculation and Statistical Analysis

Blood O2 concentration was calculated as the sum of Hb-bound O2 (O2 saturation, % × 1.34 mL O2/g Hb × g Hb/mL blood) and dissolved O2 (0.023 mL/mL blood × pO2 mmHg/760 mmHg) (Huntington and Tyrrell, 1985). The portal blood flow (PBF) rate (mL/kg(0.75)/min) was calculated using the following formula PBF = Ci × IR / (PAHp (100−PCVp) / 100) − (PAHa (100 −PCVa) / 100) (Yen and Killefer, 1987),

where Ci is the concentration of the PAH infusion solution (mg/mL); IR is the infusion rate of PAH (mL/min), PAHp, and PAHa are PAH concentrations in portal vein and arterial plasma, respectively (mg/L); and PCVp and PCVa are packed cell volumes (%) of portal vein and arterial blood, respectively. Net nutrient fluxes and apparent insulin production were calculated from portal-arterial differences × blood flow rate, whereas PDV O2 consumption was calculated as arterial-portal O2 differences × blood flow rate.

Data were analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS (version 9.3; SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC) with pen and pig as the experimental unit for Exp. 1 and 2, respectively. The performance data were analyzed as repeated measures with sex as the random effect and dietary treatment as the fixed effect. Week was the repeated term in the model. In addition, orthogonal polynomial contrasts were performed to determine linear and quadratic effects of increasing level of the D-xylose in diets. In addition, treatment means were separated using the PDIFF option in SAS when significant treatment effects were observed.

Data for arterial and portal GLU, BUN, insulin, and O2 concentrations, nutrient fluxes, insulin production and O2 consumption were analyzed as repeated measures. Time was the repeated term in the model. In the statistical model, period within square and pig were considered as random effects, whereas diet, time, and diet × time were the fixed effects. Results were reported as least square means with respective SEM. Significance was defined as P < 0.05 and 0.05 ≤ P ≤ 0.10 as trends. Treatment means for Exp. 2 were separated using the PDIFF option in SAS for individual time points, when a significant diet effect was detected using SLICE/time.

RESULTS

Exp. 1

Feed intake was not affected by the addition of D-xylose to the diets (Table 2). Increasing D-xylose level in the diets linearly reduced (P < 0.05) ADG and G:F in weeks 1 and 4 resulting in a linear decrease (P < 0.05) in final BW and overall ADG and G:F. In addition, quadratic responses on final BW (P < 0.05) and overall ADG (P < 0.05) and G:F (P = 0.076) to dietary D-xylose were observed. However, final BW and overall ADG and G:F for pigs fed 5% and 15% D-xylose did not differ from that of pigs fed 0% D-xylose diet (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of increasing dietary D-xylose on growth performance of growing pigs

| D-xylose | SEM | P values1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5% | 15% | 25% | Trt | Linear | Quadratic | ||

| BW, kg | ||||||||

| Initial | 21.4 | 21.4 | 21.3 | 21.3 | 0.05 | 0.539 | 0.216 | 0.4778 |

| Final | 43.4a | 43.7a | 42.5a | 39.1b | 0.84 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.044 |

| ADFI, kg/d | ||||||||

| Week 1 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.05 | 0.575 | 0.566 | 0.196 |

| Week 2 | 1.06 | 1.10 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.635 | 0.270 | 0.791 |

| Week 3 | 1.71 | 1.84 | 1.62 | 1.81 | 0.12 | 0.574 | 0.877 | 0.778 |

| Week 4 | 1.82 | 1.92 | 1.90 | 1.74 | 0.14 | 0.717 | 0.670 | 0.361 |

| Overall | 1.35 | 1.43 | 1.33 | 1.32 | 0.08 | 0.711 | 0.549 | 0.555 |

| ADG, kg/d | ||||||||

| Week 1 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.129 | 0.023 | 0.612 |

| Week 2 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.06 | 0.203 | 0.109 | 0.167 |

| Week 3 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 0.06 | 0.059 | 0.324 | 0.022 |

| Week 4 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.139 | 0.024 | 0.815 |

| Overall | 0.79a | 0.80a | 0.76a | 0.63b | 0.03 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.040 |

| G:F | ||||||||

| Week 1 | 0.58a | 0.50ab | 0.46b | 0.40b | 0.04 | 0.035 | 0.004 | 0.830 |

| Week 2 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 0.10 | 0.781 | 0.735 | 0.466 |

| Week 3 | 0.51ab | 0.54a | 0.61a | 0.44b | 0.04 | 0.025 | 0.432 | 0.011 |

| Week 4 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.125 | 0.026 | 0.421 |

| Overall | 0.59a | 0.56a | 0.57a | 0.49b | 0.07 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.076 |

a,bWithin a row, means with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05). Values are least square means with SEM; n = 8.

1 P values: Trt = overall dietary treatment effect; linear = linear effect to dietary D-xylose; quadratic = quadratic effect to dietary D-xylose.

Exp. 2

Pigs remained healthy and readily consumed their daily feed allowance throughout the trial. However, one pig was removed from the experiment during period 2 due to catheter patency issues. Therefore, there were five and six observations for the 0% and 15% D-xylose diets, respectively.

The PBF was greater (P < 0.05) in pigs fed 0% D-xylose than in pigs fed 15% D-xylose at 60 min after feeding (Fig. 1). Further, there was a tendency (P = 0.065) for PBF to be greater in pigs fed 15% D-xylose than in the 0% D-xylose-fed pigs at the 180-min postprandial sampling point (Fig. 1). However, diet had no effect on the preprandial and mean 6-h postprandial PBF (Table 3). Further, PDV O2 consumption was greater (P < 0.05) in pigs fed 0% D-xylose than in pigs 15% D-xylose at 60- and 120-min post-feeding, whereas PDV O2 consumption was greater (P < 0.05) in pigs fed 15% D-xylose diet than in those fed 0% D-xylose at 180-min postprandial (Fig. 2). However, diet had no effect on the mean 6-h postprandial PDV and whole-body O2 consumption (Table 3). Similarly, diet had no effect on the mean 6-h postprandial portal and arterial blood PDV O2 concentrations (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Postprandial blood flow rate in growing pigs fed diets without or with 15% xylose. Values are least square means (n = 5 for 0% xylose and n = 6 for 15% xylose) with pooled SEM. P value: *P < 0.05; †0.05 ≤ P ≤ 0.10.

Table 3.

Portal blood flow (PBF), oxygen concentrations, and whole-body (WB) and portal-drained viscera (PDV) oxygen consumption in growing pigs fed diets without or with xylose

| Item | 0% xylose | 15% xylose | SEM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBF, mL/kg(0.75) BW/min | ||||

| Preprandial | 126 | 128 | 21.6 | 0.929 |

| Postprandial | 181 | 178 | 12.9 | 0.770 |

| Blood oxygen concentration, mL/L | ||||

| Portal | 11.3 | 11.8 | 0.30 | 0.233 |

| Arterial | 12.8 | 13.4 | 0.32 | 0.272 |

| Oxygen consumption, mL/kg/min | ||||

| WB | 5.94 | 6.48 | 0.37 | 0.556 |

| PDV | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.05 | 0.445 |

Values are least square means with pooled SEM: 0% xylose, n = 5 and 15% xylose, n = 6. Preprandial values are for one sampling time point before feeding.

Figure 2.

Postprandial portal vein-drain viscera oxygen consumption in growing pigs fed diets without or with 15% xylose. Values are least square means (n = 5 for 0% xylose and n = 6 for 15% xylose) with pooled SEM. P values: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Portal and arterial BUN concentrations were greater (P < 0.05) in pigs fed 0% D-xylose than in pigs fed 15% D-xylose at various sampling times, postprandial (Table 4). In addition, the mean 6-h portal and arterial BUN concentrations were greater (P < 0.05) in 0% D-xylose–fed pigs than in 15% D-xylose–fed pigs (Table 5). Further, portal BUN flux was greater (P < 0.05) in 0% D-xylose–fed pigs than in 15% D-xylose–fed pigs at 60-, 90-, and 300-min postprandial (Fig. 3). However, diet had no effect on the mean 6-h portal BUN flux (Table 5).

Table 4.

Postprandial portal and arterial blood and plasma concentrations of some metabolites, oxygen, and insulin in growing pigs fed diets without or with xylose

| Sampling time with respect to feeding, min | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Diet | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | 120 | 180 | 240 | 300 | 360 |

| Portal | ||||||||||

| Urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 0% xylose | 2.84 | 2.66 | 2.92a | 3.04a | 3.12a | 3.28a | 3.42a | 3.40a | 3.32a |

| 15% xylose | 2.65 | 2.57 | 2.63b | 2.73b | 2.83b | 3.00b | 3.07b | 2.90b | 3.02b | |

| SEM | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| P value | 0.060 | 0.379 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.009 | |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 0% xylose | 86.6 | 221.4a | 228.8a | 186.4a | 188.4 | 158.2 | 152.6 | 141.8 | 140.4 |

| 15% xylose | 91.7 | 150.2b | 159.7b | 160.7b | 160.8 | 154.8 | 147.0 | 136.3 | 136.8 | |

| SEM | 2.83 | 18.44 | 14.62 | 6.34 | 11.39 | 3.97 | 4.26 | 6.20 | 4.33 | |

| P value | 0.209 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.091 | 0.55 | 0.356 | 0.535 | 0.562 | |

| Oxygen, mL/L | 0% xylose | 13.0 | 12.8 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 10.6b | 11.0 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 11.4 |

| 15% xylose | 12.6 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 12.0a | 11.5 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.0 | |

| SEM | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.42 | |

| P value | 0.443 | 0.808 | 0.051 | 0.139 | 0.022 | 0.394 | 0.940 | 0.422 | 0.499 | |

| Insulin, ng/mL | 0% xylose | 2.62 | 6.51a | 6.39 | 5.00 | 5.15 | 3.83 | 4.28 | 2.24 | 1.52 |

| 15% xylose | 1.44 | 4.86b | 4.42 | 4.26 | 4.63 | 4.86 | 2.63 | 2.53 | 2.80 | |

| SEM | 0.71 | 0.39 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.84 | |

| P value | 0.242 | 0.004 | 0.100 | 0.481 | 0.382 | 0.113 | 0.068 | 0.779 | 0.236 | |

| Carotid | ||||||||||

| Urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 0% xylose | 2.72a | 2.70 | 2.76a | 2.64 | 2.92a | 3.18a | 3.26a | 3.14a | 3.24a |

| 15% xylose | 2.53b | 2.50 | 2.52b | 2.58b | 2.62b | 2.83b | 2.87b | 2.93b | 2.88b | |

| SEM | 0.06 | 1.12 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| P value | 0.029 | 0.228 | 0.013 | 0.512 | 0.005 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.023 | <0.001 | |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 0% xylose | 88.8 | 138.2 | 168.8a | 141.4 | 139.2 | 118.6 | 116.0 | 116.0 | 115.6 |

| 15% xylose | 91.8 | 118.7 | 123.7b | 126.7 | 129.7 | 126.5 | 121.3 | 120.2 | 116.7 | |

| SEM | 2.40 | 11.6 | 13.19 | 6.12 | 8.84 | 3.60 | 2.94 | 3.27 | 2.71 | |

| P value | 0.373 | 0.237 | 0.018 | 0.092 | 0.966 | 0.125 | 0.204 | 0.371 | 0.782 | |

| Oxygen, mL/L | 0% xylose | 14.2 | 14.6 | 13.4 | 12.8b | 13.1 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 12.0 | 12.3 |

| 15% xylose | 13.7 | 14.8 | 14.4 | 13.8a | 13.6 | 13.0 | 12.5 | 12.6 | 12.1 | |

| SEM | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.36 | |

| P value | 0.495 | 0.760 | 0.056 | 0.046 | 0.283 | 0.112 | 0.479 | 0.334 | 0.619 | |

| Insulin, ng/mL | 0% xylose | 2.47 | 4.98 | 4.72 | 3.76 | 3.2 | 1.40b | 2.01 | 2.58 | 2.02 |

| 15% xylose | 4.09 | 5.08 | 4.80 | 4.29 | 4.28 | 3.17b | 1.75 | 1.76 | 0.93 | |

| SEM | 1.06 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.77 | 1.14 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.64 | |

| P value | 0.281 | 0.944 | 0.957 | 0.627 | 0.504 | 0.033 | 0.769 | 0.441 | 0.233 | |

Means in a column within variables with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05). Values are least square means (n = 5 for 0% xylose and n = 6 for 15% xylose) with pooled SEM.

Table 5.

Mean portal and arterial blood and plasma concentrations, net flux of some metabolites, oxygen, and insulin in growing pigs over 6-h period following meals without or with xylose

| Item | Portal | Carotid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% xylose | 15% xylose | SEM | P value | 0% xylose | 15% xylose | SEM | P value | |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 3.14a | 2.84b | 0.04 | 0.001 | 2.98a | 2.72b | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| Net flux, mmol/kg BW(0.75)min | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.148 | — | — | — | — |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 176a | 150b | 4.45 | <0.001 | 130.6 | 122.9 | 3.95 | 0.204 |

| Net flux, mg/kg BW(0.75)/min | 20.7a | 12.4b | 1.20 | 0.001 | — | — | — | — |

| Insulin, ng/mL | 4.37 | 3.87 | 0.36 | 0.353 | 3.09 | 3.26 | 0.47 | 0.802 |

| Net production, ng/kg BW(0.75)min | 0.80 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.400 | — | — | — | — |

Means in a row within variables with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05). Values are least square means (n = 5 for 0% xylose and n = 6 for 15% xylose) with pooled SEM.

Figure 3.

Postprandial portal blood urea-nitrogen flux in growing pigs fed diets without or with 15% xylose. Values are least square means (n = 5 for 0% xylose and n = 6 for 15% xylose) with pooled SEM. P values: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

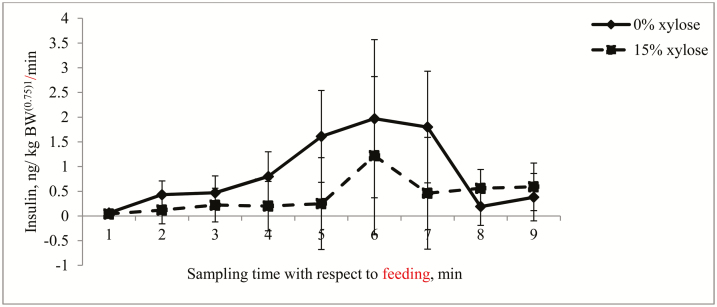

Portal GLU concentration was greater (P < 0.10) in 0% D-xylose–fed pigs than in pigs fed 15% D-xylose from 30- to 120-min postprandial (Table 4). However, carotid GLU concentrations were reduced (P < 0.05) by feeding 15% D-xylose at only 60- and 90-min postprandial. Moreover, the mean 6-h portal GLU concentration was greater (P < 0.05) in pigs fed 0% D-xylose than in those fed 15% D-xylose, whereas diet had no effect on the mean 6-h carotid GLU concentration (Table 5). Further, from 30- to 240-min postprandial, portal GLU flux was greater (P < 0.05) in 0% D-xylose–fed pigs than in pig 15% D-xylose–fed pigs (Fig. 4). Similarly, the mean 6-h portal GLU flux was greater (P < 0.05) in pigs fed 0% D-xylose than in those fed 15% D-xylose (Table 5). However, except at 30-min postprandial whereby portal insulin concentration decreased (P < 0.05) due to 15% D-xylose ingestion, diet had no effect on portal and carotid insulin concentrations (Table 4) and apparent insulin production (Fig. 5) at all other sampling times postprandial. In addition, diet had no effect on the mean 6-h portal and carotid insulin concentrations and apparent insulin production (Table 4).

Figure 4.

Postprandial portal glucose flux in growing pigs fed diets without or with 15% xylose. Values are least square means (n = 5 for 0% xylose and n = 6 for 15% xylose) with pooled SEM. P values: **P < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Postprandial apparent insulin production in growing pigs fed diets without or with 15% xylose. Values are least square means (n = 5 for 0% xylose and n = 6 for 15% xylose) with pooled SEM.

DISCUSSION

Xylose is a natural pentose sugar that is abundant in feedstuffs, including those used for pig feed (Schutte et al, 1991). Unlike GLU, xylose is poorly utilized by pigs and can adversely affect growth performance when pigs are fed diets containing high levels of xylose. Potential mechanisms by which high doses of dietary xylose influence growth and nutrient metabolism have been recently reported for obese mice (Lim et al., 2015) and broiler chickens (Regassa et al., 2017). The main objective of the present study was to investigate the potential effects of dietary xylose on portal nutrient fluxes and energetic demands of the PDV, and how these impact pig growth performance.

Effect of D-xylose on Growth Performance

Feed intake was not affected by increasing dietary D-xylose content in the present study. In chickens, Peng et al. (2004) reported that increasing dietary D-xylose content up to 40% linearly decreased feed consumption. Recently, we reported that up to 15% dietary D-xylose inclusion linearly decrease feed consumption in broiler chickens (Regassa et al., 2017). Wise et al. (1954) fed 2-wk-old pigs semi-synthetic diets containing either 18.7% or 37.4% D-xylose and observed depression in feed consumption. It is not clear why up to 25% dietary D-xylose did not depress feed consumption in the present study, although we used heavier or older pigs compared with the study by Wise et al. (1954). The differences in the composition of the basal diet between the study by Wise et al. (1954) and the current study (semi-synthetic vs. corn–SBM), and the differences in estimating nutrient requirements in the 1950s and now may partly explain the discrepancies in feed intake. Nonetheless, further studies are required to clarify if age or BW is a factor in pigs’ response to dietary D-xylose.

In this study, final BW, growth rate, and feed efficiency decreased when D-xylose content in the diets increased. These observations are in agreement with previous results in pigs (Wise et al., 1954) and chickens (Wagh and Waibel, 1966; Schutte, 1990; Schutte et al., 1992; Peng et al., 2004), who also reported decreased weight gain and feed efficiency due to increasing dietary D-xylose content. An explanation for the reduced weight gain and feed efficiency may be due to the lower ME content of D-xylose compared with GLU as reported by Schutte et al. (1991) and Verstegen et al. (1997). Although D-xylose is almost completely digested and absorbed by the small intestine, most of the absorbed dietary D-xylose is excreted via urine and thus, not retained for body growth (Wise et al., 1954). For instance, Schutte et al. (1991) reported that only 44.5% of ingested D-xylose contributed to ME when pigs were fed 100 g D-xylose/kg of diet. Similarly, Verstegen et al. (1997) reported that at 10% dietary D-xylose inclusion level between 38% and 64% of the energy from D-xylose contribute to the ME. Results from the preceding studies suggest that less than 50% of the energy in dietary xylose contributes to the total ME. In addition, our recent study in broiler chickens suggest that the decline in growth performance and nutrient utilization due to high dietary xylose could be linked to alterations in the expression of hepatic enzymes and transcription factors involved in GLU and lipid metabolism (Regassa et al., 2017). Nonetheless, the results show that final BW, ADG, feed efficiency of pigs fed 15% D-xylose diet was not different from pigs fed 5% or 0% D-xylose diet. Therefore, the results of this study suggested that up to 15% D-xylose could be included in growing pig diet without any detrimental effect on growth performance.

Effects of D-xylose on Energy Expenditure, Portal Nutrient Fluxes, and Insulin Production

The 15% D-xylose diet had no effect on whole-animal O2 consumption. Similarly, Yule and Fuller (1992) and Verstegen et al. (1997) did not find any significant effect of feeding pigs D-xylose diets on heat production and heat increment, respectively, compared to the control diet. Yule and Fuller (1992) suggested the lack of significant effect on heat increment, when the pigs were fed D-xylose, could be due to reduced physical activity in those pigs when D-xylose was being metabolized. This premise may partly explain why we did not find any effect of D-xylose on whole-animal O2 consumption in the present study. However, further studies are required to account for the contribution of physical activity to energy expenditure when pigs are fed the dietary treatments used in the present study.

Previous studies have shown that feeding chickens a diet containing 20% D-xylose increases caecel weight due to fermentation of D-xylose in this organ (Longstaff et al., 1988). Increased visceral organ mass has been reported to lead to an increase in energy expenditure and nutrient utilization in pigs (Yen, 1997; Yen et al., 2001) because of the high metabolic activity of these organs (Yen et al., 1989). Therefore, in this study, it was hypothesized that one mechanism by which high dietary xylose hampers growth rate is to increase the PDV O2 consumption (as an indicator of energy expenditure). However, the preprandial and postprandial PDV O2 consumption were not significantly different between the pigs fed 15% and 0% D-xylose diets. Therefore, the whole-animal and PDV O2 consumption data suggest that up to 15% dietary D-xylose could be utilized to the same extent as a diet containing 0% D-xylose without increasing energy demands for maintenance purposes at the expense of body growth.

It has been reported that the gut microflora use fermentable fiber as energy and N from urea for protein synthesis and thus feeding fermentable fiber will increase microbial growth and urea transfer from the blood to the gut for microbial use and thereby reduce urea excretion in urine (Levrat et al., 1993; Younes et al., 1995b). Some amount of ingested xylose is degraded by the microflora in the gut (Longstaff et al., 1988; Schutte et al., 1992). Therefore, the lower portal BUN concentration in the pigs fed 15% D-xylose compared with those fed 0% D-xylose observed in this study suggest that some of the D-xylose was fermented and that BUN was secreted into the gut for microbial use instead of excretion in the urine. Lower plasma urea concentrations have also been reported in rats (Younes et al., 1995a) and pigs (Malmlöf, 1987; Lenis et al., 1996; Zervas and Zijlstra, 2002) when fermentable fibers were fed. However, portal urea flux did not differ between the 15% and 0% D-xylose diets because arterial BUN was equally reduced when 15% D-xylose was fed. Similar observations have been reported by Malmlöf (1987) for wheat straw meal and Lenis et al. (1996) for purified NDF. The lack of effect of 15% D-xylose and fermentable fiber on portal urea flux in this study and that of others (Malmlöf, 1987; Lenis et al., 1996), respectively, suggest that fermentable carbohydrates may alter N excretion from urine to feces but this does not depend solely on urea circulation into gut. Therefore, it is possible that ammonia was also used as an N source and thus less ammonia was absorbed from the large intestine to be converted into urea in the pigs fed fermentable carbohydrates, as reported for starch infusion into the ileum on urea recycling in pigs by Mosenthin et al. (1992).

In this study, ingestion of the dietary D-xylose significantly reduced postprandial portal GLU concentration and net flux. Similarly, D-xylose ingestion reduced postprandial GLU concentrations in healthy humans (Bae et al., 2011). In this study, cornstarch was substituted for D-xylose in the D-xylose-containing diet. Therefore, the reduction in postprandial portal GLU concentrations and flux due to D-xylose ingestion can be explained by the lower starch content in the D-xylose diet leading to lower starch intake in those pigs. In rats, xylose has been reported to inhibit sucrase activity in a noncompetitive manner thereby leading to decreased postprandial blood GLU levels (Asano et al., 1996). Whether this could explain the decrease in portal GLU concentration and flux in the pigs fed 15% D-xylose remains unknown. Nonetheless, postprandial arterial GLU concentration was not significantly different between the dietary treatments suggesting that ingestion of 15% D-xylose may not reduce the systemic circulation of GLU for uptake by the peripheral tissues of economic importance (e.g., muscles). On the other hand, pancreatic insulin is released in response to increased postprandial GLU flux. Therefore, it was expected that reduced GLU flux due to dietary D-xylose observed in this study would reduce postprandial insulin levels and production. However, 15% dietary D-xylose ingestion did not significantly reduce postprandial insulin levels in this study. Our finding contradicts the results of Bae et al. (2011) showing that ingestion of D-xylose reduced postprandial insulin levels in healthy humans. The high within-treatment variability for the insulin concentration and apparent production observed in this study may explain the lack of dietary D-xylose effect on postprandial insulin concentrations and production.

In this study, 15% dietary D-xylose inclusion supported growth performance of the growing pigs similar to the 0% D-xylose diet. Furthermore, 15% dietary D-xylose did not affect the energy demand of the PDV but reduced net GLU flux in growing pigs due to lower starch content in the D-xylose diet. Xylose, arabinose, and GLU constitute the main sugars of NSP in cereal grains and their coproducts, whereas xylose is the most abundant sugar in cereal hemicellulose. For instance, the xylose content in corn, SBM, and corn distillers dried grains with solubles (DDGS) are 3.0, 1.9, and 7.7%, respectively (Bach Knudsen, 1997; Pedersen et al., 2014). Therefore, for a practical growing pig diet based on corn and SBM with 30% corn DDGS, a complete hydrolysis of the NSP will release about 4.1% of xylose. Thus, excessive xylose production due to high doses of supplemental xylanase should not have a detrimental effect on growing pig performance.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 2016 Midwest ASAS/ADAS Meeting, Des Moines, IA. The authors are grateful to Robert Stuski and Akin Akinola with care of animals. We also thank Dr Manuel Lachica of the Animal Nutrition Department, Estación Experimental del Zaidín, Granada, Spain, for the technical assistance with the portal-vein catheterized pig model.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adeola O. and Cowieson A. J.. 2011. Opportunities and challenges in using exogenous enzymes to improve non-ruminant animal production. J. Anim. Sci. 89:3189–3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum A. K., E. Kiarie M. C. Walsh, and Nyachoti C. M.. 2016. Postprandial portal fluxes of essential amino acids, volatile fatty acids, and urea-nitrogen in growing pigs fed a high-fiber diet supplemented with a multi-enzyme cocktail. J. Anim. Sci. 94:3771–3785. doi:10.2527/jas.2015-0077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum A. K., B. A. Slominski, and Nyachoti C. M.. 2012. Organ weight, intestinal morphology, and fasting whole-body oxygen consumption in growing pigs fed diets containing distillers dried grains with solubles alone or in combination with a multienzyme supplement. J. Anim. Sci. 90:3032–3040. doi:10.2527/jas.2011-4380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano T., Yoshimura Y., Kunugita K.. 1996. Sucrase inhibitory activity of D-xylose and effect on the elevation of blood glucose in rats. J. Japan. Soc. Nutr. Food. Sci. 49:157–162. doi:10.4327/jsnfs.49.157 [Google Scholar]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC).. 1990. Official methods of analysis. 15th ed Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem, Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Bach Knudsen K. E. 1997. Carbohydrate and lignin contents of plant materials used in animal feeding. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 67:319–338. doi:10.1016/S0377-8401(97)00009-6 [Google Scholar]

- Bae Y. J., Y. K. Bak B. Kim M. S. Kim J. H. Lee, and Sung M. K.. 2011. Coconut-derived D-xylose affects postprandial glucose and insulin responses in healthy individuals. Nutr. Res. Pract. 5:533–539. doi:10.4162/nrp.2011.5.6.533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford M. and Cowieson A.. 2012. Exogenous enzymes and their effects on intestinal microbiology. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 173: 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011. 12.018 [Google Scholar]

- Bull B. S., Koepke J. A., Simson E., and van Assendelft O. W.. 2000. Procedure for determining packed cell volume by the hematocrit method. 3rd ed NCCLS publication H7-A3, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- CCAC.. 2009. Guidelines on: the care and use of farm animals in research, teaching and testing. Canadian Council on Animal Care, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington G. B. and Tyrrell H. F.. 1985. Oxygen consumption by portal-drained viscera of cattle: comparison of analytical methods and relationship to whole body oxygen consumption. J. Dairy Sci. 68:2727–2731. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(85)81157-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiarie E., L. F. Romero, and Nyachoti C. M.. 2013. The role of added feed enzymes in promoting gut health in swine and poultry. Nutr. Res. Rev. 26:71–88. doi:10.1017/S0954422413000048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenis N. P., P. Bikker J. van der Meulen J. T. van Diepen J. G. Bakker, and Jongbloed A. W.. 1996. Effect of dietary neutral detergent fiber on ileal digestibility and portal flux of nitrogen and amino acids and on nitrogen utilization in growing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 74:2687–2699. doi:10.2527/1996.74112687x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levrat M.-A., Rémésy C., and Demigné C.. 1993. Influence of inulin on urea and ammonia nitrogen fluxes in the rat cecum: consequences on nitrogen excretion. J. Nutr. Biochem. 4:351–356. doi:10.1016/0955-2863(93)90081-7 [Google Scholar]

- Lim E., J. Y. Lim J. H. Shin P. R. Seok S. Jung S. H. Yoo, and Kim Y.. 2015. D-xylose suppresses adipogenesis and regulates lipid metabolism genes in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutr. Res. 35:626–636. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstaff M. A., A. Knox, and McNab J. M.. 1988. Digestibility of pentose sugars and uronic acids and their effect on chick weight gain and caecal size. Br. Poult. Sci. 29:379–393. doi:10.1080/00071668808417063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmlöf K. 1987. Porto-arterial plasma concentration differences of urea and ammonia-nitrogen in growing pigs given high- and low-fibre diets. Br. J. Nutr. 57:439–446. doi:10.1079/BJN19870051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsilio R., R. Dall’Amico G. Montini L. Murer M. Ros G. Zacchello, and Zacchello F.. 1997. Rapid determination of p-aminohippuric acid in serum and urine by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B. Biomed. Sci. Appl. 704:359–364. doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(97)00467-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosenthin R., W. C. Sauer H. Henkel F. Ahrens, and de Lange C. F.. 1992. Tracer studies of urea kinetics in growing pigs: II. The effect of starch infusion at the distal ileum on urea recycling and bacterial nitrogen excretion. J. Anim. Sci. 70:3467–3472. doi:10.2527/1992.70113467x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC.. 1998. Nutrient requirements of swine. 10th rev. ed Natl. Acad. Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen M. B., Dalsgaard S., Knudsen K. B., Yu S., and Lærke H. N.. 2014. Compositional profile and variation of distillers dried grains with solubles from various origins with focus on non-starch polysaccharides. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 197:130–141. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2014.07.011 [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y. L., Guo Y. M., and Yuan J. M.. 2004. Effects of feeding xylose on the growth of broilers and nutrient digestibility as well as absorption of xylose in the portal-drained viscera. Asian-Australian J. Anim. Sci. 17:1123–1130. doi:10.5713/ ajas.2004.1123 [Google Scholar]

- Regassa A., E. Kiarie J. S. Sands M. C. Walsh W. K. Kim, and Nyachoti C. M.. 2017. Nutritional and metabolic implications of replacing cornstarch with D-xylose in broiler chickens fed corn and soybean meal-based diet. Poult. Sci. 96:388–396. doi:10.3382/ps/pew235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte J. B. 1990. Nutritional implications and metabolizable energy value of D-xylose and L-arabinose in chicks. Poult. Sci. 69:1724–1730. doi:10.3382/ps.0691724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte J. B., J. de Jong R. Polziehn, and Verstegen M. W.. 1991. Nutritional implications of D-xylose in pigs. Br. J. Nutr. 66:83–93. doi:10.1079/BJN19910012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte J. B., J. de Jong E. J. van Weerden, and van Baak M. J.. 1992. Nutritional value of D-xylose and L-arabinose for broiler chicks. Br. Poult. Sci. 33:89–100. doi:10.1080/00071 669208417446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstegen M., Schutte J., Hel W., Polziehn R., Schrama J., and Sutton A.. 1997. Dietary xylose as an energy source for young pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 77:180–188. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0396.1997.tb00753.x [Google Scholar]

- Wagh P. V. and Waibel P. E.. 1966. Metabolizability and nutritional implications of L-arabinose and D-xylose for chicks. J. Nutr. 90:207–211. doi:10.1093/jn/90.2.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagh P. V. and Waibel P. E.. 1967. Metabolism of L-arabinose and D-xylose by chicks. J. Nutr. 92:491–496. doi:10.1093/jn/92.4.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M. C., Kiarie E., Romero L., and Arent S.. 2016. Xylanase solubilization of corn and wheat arabinoxylans in mixed growing pig diets subjected to upper gut in-vitro digestion and in ileal digesta. J. Anim. Sci. 94:111–111. doi:10.2527/msasas2016-235 [Google Scholar]

- Wise M., Barrick E., Wise G., and Osborne J.. 1954. Effects of substituting xylose for glucose in a purified diet for pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 13: 365–374. doi:10.2527/jas1954.132365x [Google Scholar]

- Yen J. 1997. Oxygen consumption and energy flux of porcine splanchnic tissues. In: Digestive physiology in pigs: proceedings of the VIIth International Symposium on Digestive Physiology in Pigs; May 26 to 28, 1997; Saint Malo, France. [Google Scholar]

- Yen J. T. and Killefer J.. 1987. A method for chronically quantifying net absorption of nutrients and gut metabolites into hepatic portal vein in conscious swine. J. Anim. Sci. 64:923–934. doi:10.2527/jas1987.643923x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen J. T., J. A. Nienaber D. A. Hill, and Pond W. G.. 1989. Oxygen consumption by portal vein-drained organs and by whole animal in conscious growing swine. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 190:393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen J., Nyachoti C., de Lange C., and Nienaber J.. 2001. Effect of diet composition on organ size and energy expenditure in growing pigs. In: Digestive Physiology of Pigs: Proceedings of the 8th Symposium; June 20 to 22, 2000; Uppsala, Sweden; p 98. [Google Scholar]

- Younes H., Demigné C., Behr S., and Rémésy C.. 1995a. Resistant starch exerts a lowering effect on plasma urea by enhancing urea N transfer into the large intestine. Nutr. Res. 15:1199–1210. doi:10.1016/0271-5317(95)00079-X [Google Scholar]

- Younes H., K. Garleb S. Behr C. Rémésy, and Demigné C.. 1995b. Fermentable fibers or oligosaccharides reduce urinary nitrogen excretion by increasing urea disposal in the rat cecum. J. Nutr. 125:1010–1016. doi:10.1093/jn/125.4.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule M. A. and Fuller M. F.. 1992. The utilization of orally administered d-xylose, l-arabinose and d-galacturonic acid in the pig. Inter. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 43:31–40. doi:10.3109/09637489209027530 [Google Scholar]

- Zervas S. and Zijlstra R. T.. 2002. Effects of dietary protein and fermentable fiber on nitrogen excretion patterns and plasma urea in grower pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 80:3247–3256. doi:10.2527/2002.80123247x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]