Abstract

In developed countries, dogs and cats frequently suffer from obesity. Recently, gut microbiota composition in humans has been related to obesity and metabolic diseases. This study aimed to evaluate changes in body composition, and gut microbiota composition in obese Beagle dogs after a 17-wk BW loss program. A total of six neutered adult Beagle dogs with an average initial BW of 16.34 ± 1.52 kg and BCS of 7.8 ± 0.1 points (9-point scale) were restrictedly fed with a hypocaloric, low-fat and high-fiber dry-type diet. Body composition was assessed with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan, before (T0) and after (T1) BW loss program. Individual stool samples were collected at T0 and T1 for the 16S rRNA analyses of gut microbiota. Taxonomic analysis was done with amplicon-based metagenomic results, and functional analysis of the metabolic potential of the microbial community was done with shotgun metagenomic results. All dogs reached their ideal BW at T1, with an average weekly proportion of BW loss of −1.07 ± 0.03% of starting BW. Body fat (T0, 7.02 ± 0.76 kg) was reduced by half (P < 0.001), while bone (T0, 0.56 ± 0.06 kg) and muscle mass (T0, 8.89 ± 0.80 kg) remained stable (P > 0.05). The most abundant identified phylum was Firmicutes (T0, 74.27 ± 0.08%; T1, 69.38 ± 0.07%), followed by Bacteroidetes (T0, 12.68 ± 0.08%; T1, 16.68 ± 0.05%), Fusobacteria (T0, 7.45 ± 0.02%; T1, 10.18 ± 0.03%), Actinobacteria (T0, 4.53 ± 0.02%; T1, 3.34 ± 0.01%), and Proteobacteria (T0, 1.06 ± 0.01%; T1, 1.40 ± 0.00%). At genus level, the presence of Clostridium, Lactobacillus, and Dorea, at T1 decreased (P = 0.028), while Allobaculum increased (P = 0.046). Although the microbiota communities at T0 and T1 showed a low separation level when compared (Anosim’s R value = 0.39), they were significantly biodiverse (P = 0.01). Those differences on microbiota composition could be explained by 13 genus (α = 0.05, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score > 2.0). Additionally, differences between both communities could also be explained by the expression of 18 enzymes and 27 pathways (α = 0.05, LDA score > 2.0). In conclusion, restricted feeding of a low-fat and high-fiber dry-type diet successfully modifies gut microbiota in obese dogs, increasing biodiversity with a different representation of microbial genus and metabolic pathways.

Keywords: obesity, dog, lean, metagenomics, Allobaculum, shotgun

INTRODUCTION

In industrialized countries, obesity is the most frequent malnutrition disease in dogs and cats, with and estimated prevalence in dogs between 22% and 40% (German, 2006; Lund et al., 2006; Bland et al., 2010). In companion animals, dogs are considered obese when they are 15% to 20% above the dog’s ideal BW (IBW) (Bland et al., 2010). Around 97% of dog obesity cases are related to what is considered as “owner attitudes” which determined the dog’s diet, exercise, and treats intake (German, 2006; Bland et al., 2010). In humans, obesity has been recently associated with gut microbiota composition and its related metabolic disease (Turnbaugh et al., 2009; Tehrani et al., 2012). Alterations and disruption of gut microbiota have also been observed in obese dogs and cats (Handl et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015; Kieler et al., 2016; Fischer et al., 2017). Although its mechanism is still unknown, it has been proposed that microbiota could influence metabolic pathways related to food energy extraction, intestinal inflammation, and satiety which all favor fat storage and could lead to the development of obesity (Turnbaugh et al., 2006; Tehrani et al., 2012). Studies on gut microbiota in obese subjects have mainly focused on mice and humans, and there is a lack of information on the effect of a BW loss program on microbiota profile in dogs. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of a 17-wk BW loss program in obese Beagle dogs on BW, body composition, and gut microbiota profile in feces through 16S rRNA gene sequences and its functional capabilities.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was carried out at the Veterinary Faculty of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB, Barcelona, Spain), during fall and winter 2014–2015. The experimental procedure received the prior approval from the Animal Protocol Review Committee of UAB, following the European Union Guidelines for the ethical care and handling of animals under experimental conditions with Register Number 787.

Animals and Management

Six neutered adult Beagle dogs (males = 3; females = 3) aged between 4 and 10 yr were enrolled into this study, and after an 8-wk-adaptation period average initial weight was 16.34 ± 1.52 kg and BCS assessed according to a validated 9-point body condition scoring system (Laflamme et al., 1994) was on average 7.8 ± 0.1 points. Dogs were considered healthy, except for obesity, based on physical examination, complete blood count, and serum biochemistry analysis. They had not been receiving medications that could affect gut microbiota such as antibiotics for at least 3 wks before starting the study. All dogs were kept indoors, housed by pairs in a 3.00 m × 8.00 m pen. Dogs had, at least once a day, access to a 25 m2 yard for exercise and interaction with other dogs. The animals were fed individually once a day with a commercial diet. Intake was recorded daily by weight difference after 30 min from the time they were fed. Drinking water was provided ad libitum throughout the study.

Diets and Feeding Regime

Dogs were fed ad libitum with a maintenance commercial extruded (dry-type) diet (control diet [Advance Medium Adult chicken and rice from Affinity Petcare, Spain]) during the 8-wk-adaptation period to determine a baseline. The control diet was formulated to contain 27.8% of CP, 15.4% of fat, 29.4% of starch, 2% of crude fiber, 6.2% of ash on a DM basis, and 3,909 kcal of in vivo measured ME as fed. After the adaptation period, animals were enrolled in a BW loss program.

The BW loss program lasted 17 wks and dogs were fed with a hypocaloric, low-fat, high- protein, low-carbohydrate and high-fiber dry-type diet (obesity diet) formulated to meet or exceed the maintenance nutrient requirement based upon the European Pet Food Industry Federation (FEDIAF) Guidelines to contain 33.7% of CP, 8.3% of fat, 20.8% of starch, 10.65% of crude fiber, 8.2% of ash on a DM basis, and 2,870 kcal of in vivo measured ME as fed. Obesity diet was based on animal proteins (poultry and pork), barley, vegetal proteins (corn and potato), vegetal fibers (pea, oat, cellulose), animal fat, palatability enhancers (hydrolyzed animal proteins), minerals, and vitamins. In addition, the obesity diet contained 0.5% fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and 3% sugar beet pulp. Dogs were weighed weekly, and a fixed amount of the obesity diet was individually offered once a day. The amount fed was reassessed weekly and adjusted, if necessary, by 5% reduction of the amount offered, to obtain a weekly BW loss rate between 1% and 2% of starting BW (Diez et al., 2002). Dogs were removed from the BW loss program when they reached their IBW (calculated as lean mass × 1.25) or at the end of the 17 wks, whichever came first, and then they were fed to maintain BW.

A sample of each diet used in the study was analyzed (Table 1). Dry matter was determined at 103 °C for 4 h according to AOAC 930.15 method and ash content was measured gravimetrically by igniting samples in a muffle furnace at 600 °C for 4 h according to AOAC 942.05 method. The Dumas method AOAC 968.06 with a Leco analyzer (Leco Corporation, St. Joseph, MI) was used for nitrogen (N) determination and CP was calculated as percentage of N × 6.25. Crude fiber was determined on an ash-free basis by AOCS Ba 6a-05 method using the Ankom200 Fiber Analyzer incubator (AnkomTechnology, Macedon, NY). Soluble and insoluble fiber was determined using AOAC 991.19 and 993.42 methods, respectively. Total dietary fiber was calculated as the sum of soluble and insoluble fiber. Fat was analyzed by the Soxhlet method AOAC 954.02 Hydrotherm (C. Gerhardt Gmbh & Co. Kg, Germany) automatic acid hydrolysis system. Percentage of starch was calculated as 100 − (%DM + % fat + % CP + % ash + % crude fiber).

Table 1.

Food composition

| Parameter | Control diet | Obesity diet |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture, % | 8.27 | 8.06 |

| CP, % in DM | 27.35 | 30.94 |

| Fat, % in DM | 15.26 | 8.37 |

| Starch, % in DM | 29.35 | 19.05 |

| Ash, % in DM | 6.97 | 7.66 |

| Crude fiber, % in DM | 1.89 | 9.81 |

| Soluble fiber, % in DM | 1.60 | 2.60 |

| Insoluble fiber, % in DM | 7.40 | 22.20 |

| Total dietary fiber, % in DM | 9.00 | 24.8 |

Sampling Collection

Percentage of body fat, bone mass, and lean mass was assessed with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan (Lunar BX-1L; General Electric, Healthcare, Belgium) of the dogs at the Affinity Petcare Nutrition Center the day before starting the BW loss program (T0) and at the end of the study (T1). Blood samples were taken at T0 and T1 from the cephalic vein into plastic EDTA tube (Deltalab, Barcelona, Spain) and Serum Separator tubes (Deltalab) between 09:00 h and 10:00 h after a 24-h fast. Serum was obtained by centrifugation for 15 min at 1,500 × g. Blood and plasma aliquots were sent refrigerated (4 °C) to a reference laboratory (Vetlab, Idexx Laboratories, Barcelona, Spain) for a complete blood count and serum biochemistry analysis. Individual stool samples at both time points were collected immediately after spontaneous defecation, immediately frozen at −80 °C without any additives or pretreatment, and sent to Genostar Bioinformatics Software & Services (Montbonnot St Martin, France) for the DNA analyses.

Extraction and Analysis of rRNA

Aliquots of 180 to 220 mg of stool samples were prepared in 2 ml lysing matrix B tubes (MPbio; 116911500; Santa Ana, CA). After addition of the lysis buffer the samples have been vortexed for 5 min on a Turbomix system (Scientific Industries; Bohemia, NY) followed by a bead beating step on a fastprep24 device (MPbio; 4 time 45seconds at speed 4.0). The QIAmp Fast-DNA stool kit (Qiagen 51604; Hilden, Germany) was then applied according to the manufacturers recommendations. DNA eluates were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (1%).

The taxonomic analysis was done with amplicon-based metagenomics. Briefly, DNA sequences on specific regions of the 16s rRNA were sequenced by a MiSeq sequencer Illumina (Illumina Inc.; San Diego, CA). Following amplification and sequencing, each sample was represented by a series of reads. The paired-end reads were assembled and thereafter, trimmed and filtered basing on the default parameters (percentage of consecutive high-quality base calls (p) = 75%, maximum number of consecutive low-quality base calls (r) = 3, maximum number of ambiguous bases (N) = 0, and minimum Phred quality score (q) = 3) (Navas-Molina et al., 2013), and clustered. Each operational taxonomic units (OTU) was assigned to a taxonomy through GreenGenes database (DeSantis et al., 2006; McDonald et al., 2012) with Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier. An in-house pipeline of Genostar (Montbonnot St Martin, France) adapted from Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME; Caporaso et al., 2010) was used to analyze metagenomics data.

The functional analysis of the metabolic potential of the microbial community was done with shotgun metagenomic study of the bacterial DNA sequences. Briefly, the DNA sequences were prepared with the kit Nextera XT and sequenced by a MiSeq sequencer Illumina (Illumina Inc.). Following the sequencing, the paired-end reads were analyzed by in-house pipeline of Genostar. Using HTQC shotgun, metagenomic results were trimmed and filtered depending on the read size (L = 80) and on the quality score of the sequences (Q = 20) (Yang et al., 2013). Coding genes for enzyme classification and metabolic pathways were analyzed using HUMAnN2 (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/humann2/manual), a pipeline for efficiently and accurately profiling the presence or absence and abundance of microbial pathways in a community from metagenomics sequencing data.

Statistical Methods

Statistics were performed with SPSS v.19.0.0 of IBM software (Chicago, IL) or QIIME software (Caporaso et al., 2010) unless otherwise indicated. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, and significance was declared at P <0.05 unless otherwise indicated. Body weight and body composition, complete blood count, and serum biochemistry analysis differences between T0 and after T1 were analyzed using a nonparametric Wilcoxon rank–sum test. Bacterial diversity was calculated based on the Shannon–Weaver diversity index (Atlas and Bartha, 1998; Ledder et al., 2007), Chao index (Hughes et al., 2001), and Equitability (Duan et al., 2009) at species level. Rarefaction curves were used to estimate diversity and complete the sampling method. Bacterial diversity data were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Biodiversity differences between T0 and T1 were compared using nonparametric analysis of similarity statistical (ANOSIM) test (Navas-Molina et al., 2013). To determine which OTU and functions most likely explained differences between T0 and T1 a linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) (https://bitbucket.org/biobakery/biobakery/wiki/lefse) was used, and significant differences were tested by nonparametric Wilcoxon rank–sum test.

RESULTS

BW Loss

All dogs reached their IBW at the end of the 17-wk period. Throughout the BW loss program dogs reduced their energy intake by −28.22 ± 4.89 kcal/kg IBW (P = 0.007), with an initial average feed intake of 32.33 ± 2.90 g/kg IBW and a final average intake of 23.19 ± 22.84 g/kg IBW (P = 0.006). Therefore, the total average BW loss at the end of the study was −9.14 ± 1.60 g/kg IBW, which corresponds to 18% of initial BW, with an average weekly proportion of BW loss of 1.07 ± 0.03% of previous BW. Moreover, during the study, body fat was reduced by half (T0, 7.02 ± 0.76 kg; T1, 3.07 ± 0.37 kg; P < 0.001), while bone (T0, 0.56 ± 0.06 kg; T1, 0.46 ± 0.04) and muscle mass (T0, 8.89 ± 0.80 kg; T1, 9.59 ± 0.98) remained stable (P > 0.05).

Blood and Serum Biochemistry Analysis

All parameters of the complete blood count and serum biochemistry analysis were within the normal range at T0 and T1. Nevertheless, the following parameters revealed significant differences between both time points. Albumin (−0.33 ± 0.11 d/dL; P = 0.009), alkaline phosphatase (−15.5 ± 4.2 UI/L; P = 0.005), cholesterol (−35.6 ± 7.02 mg/dL; P = 0.004), creatinine (−0.03 ± 0.03 UI/L; P = 0.102), fructosamine (−20.8 ± 7.04 µmol/L; P = 0.032), glucose (−4.83 ± 2.27 mg/dL; P = 0.003), insulin (−9.87 ± 1.67 µIU/mL; P = 0.002), lymphocytes (−494.7 ± 189.8 × 109/L; P = 0.025), paraoxonase type 1 (−0.41 ± 0.25 IU/mL; P = 0.002), prothrombin time (−0.48 ± 0.07 s; P < 0.001), segmental neutrophils (−1885.7 ± 475.7 109/L; P = 0.002), mean corpuscular volume (−4.24 ± 0.43 µm3; P < 0.001) were lower at T1 than T0; while, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (12.4 ± 5.0 pg; P = 0.029), was higher at T1 than T0.

Phylogenetic Analysis

An average of 628,000 reads was obtained for each sample, and after cleaning and filtering, 25% of the reads were removed. Median read length ranged from 563 to 589 bp. Between 91.51% and 96.14% of the reads showed >97% sequence similarity to existing 16S rRNA gene sequences. A total of 10 phylogenetic linages were identified with a similar pattern at both times, being Firmicutes the most abundant (T0, 74.27 ± 0.08%; T1, 69.38 ± 0.07%), followed by Bacteroidetes (T0, 12.68 ± 0.08%; T1, 16.68 ± 0.05%), Fusobacteria (T0, 7.45 ± 0.02%; T1, 10.18 ± 0.03%), Actinobacteria (T0, 4.53 ± 0.02%; T1, 3.34 ± 0.01%), and Proteobacteria (T0, 1.06 ± 0.01%; T1, 1.40 ± 0.00%). Firmicutes phylum included Clostridia, Bacilli, and Erysipelotrichi classes, whose proportion differed between both sampling times. At T1, proportion of Clostridia (T0, 59.35 ± 0.06%; T1, 33.20 ± 0.09%) and Bacilli (T0, 7.86 ± 0.02%; T1, 2.59 ± 0.01%) decreased, while Erysipelotrichi (T0, 7.05 ± 0.02%; T1, 32.53 ± 0.011%) increased.

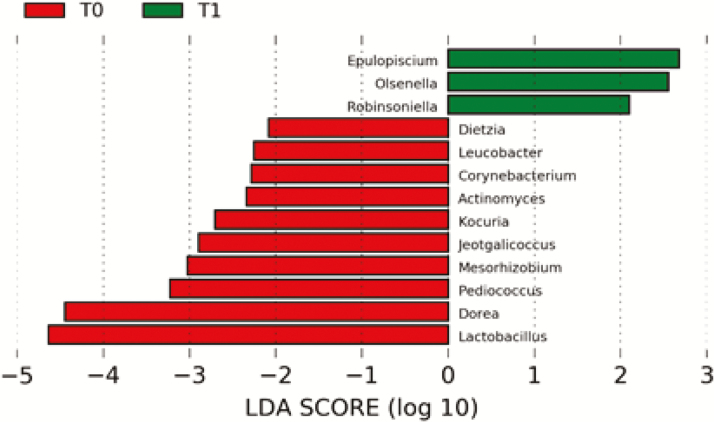

At genus level, a total of 151 and 107 OTU for T0 and T1, respectively, were identified. The most abundant genus at T0 were Clostridium (Clostridiaceae family) and Blautia (Lachnospiraceae family), both from Clostridia class. On the other hand, the most abundant genus at T1 were Allobaculum (Erysipelotrichidae family). Proportion of most abundant bacteria (>0.5% relative abundance) identified sequences at genus level is shown in Table 2. From these genus, despite variations on bacteria proportion at both sampling times, only significant differences were detected for four genera. At T1, Clostridium, Lactobacillus, and Dorea genus decreased (P = 0.028), while genus Allobaculum increased (P = 0.046). At genus level, we detected 13 OTU that most likely explained differences between both time points (Fig. 1). Of these, 10 OTU were significantly over represented at T0, and three OTU were over represented at T1 (α = 0.05, LDA score >2.0).

Table 2.

Bacteria genus distribution of the total 16S rRNA identified sequences of microbiota in dog feces before (T0) and after (T1) a 17-wk BW loss program

| Phylum | Genus | T0, % | T1, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | Unclassified Actinobacteria | 4.48 ± 1.58 | 3.33 ± 0.73 |

| Bacteroidetes | Unclassified Bacteroidales | 3.24 ± 1.80 | 7.96 ± 3.45 |

| Bacteroides | 5.39 ± 3.01 | 5.47 ± 2.03 | |

| Prevotella | 3.93 ± 3.40 | 3.12 ± 1.43 | |

| Firmicutes | Unclassified Bacilli | 1.46 ± 0.75 | 1.87 ± 0.93 |

| Lactobacillus | 5.96 ± 2.68 | 0.33 ± 2.00* | |

| Clostridium | 22.07 ± 4.80 | 10.44 ± 3.42* | |

| Unclassified Lachnospiraceae | 5.55 ± 0.87 | 3.95 ± 0.99 | |

| Blautia | 15.14 ± 2.40 | 9.37 ± 3.91 | |

| Dorea | 5.89 ± 1.44 | 2.29 ± 0.56* | |

| Unclassified Peptostreptococcaceae | 1.76 ± 0.65 | 1.12 ± 0.40 | |

| Faecalibacterium | 5.80 ± 1.96 | 2.97 ± 1.24 | |

| Unclassified Erysipelotrichaceae | 1.44 ± 0.54 | 1.22 ± 0.25 | |

| Allobaculum | 4.53 ± 2.01 | 30.13 ± 1.10* | |

| Fusobacteria | Cetobacterium | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.52 ± 1.47 |

| Fusobacterium | 7.30 ± 1.80 | 8.47 ± 2.28 | |

| Proteobacteria | Sutterella | 0.48 ± 0.27 | 1.08 ± 0.36 |

Values are shown as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 1.

Taxonomic distribution of genus bacterial groups differentially present before (T0, red) and after (T1, green) 17-week BW loss program dog feces using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (α = 0.05, LDA score > 2.0).

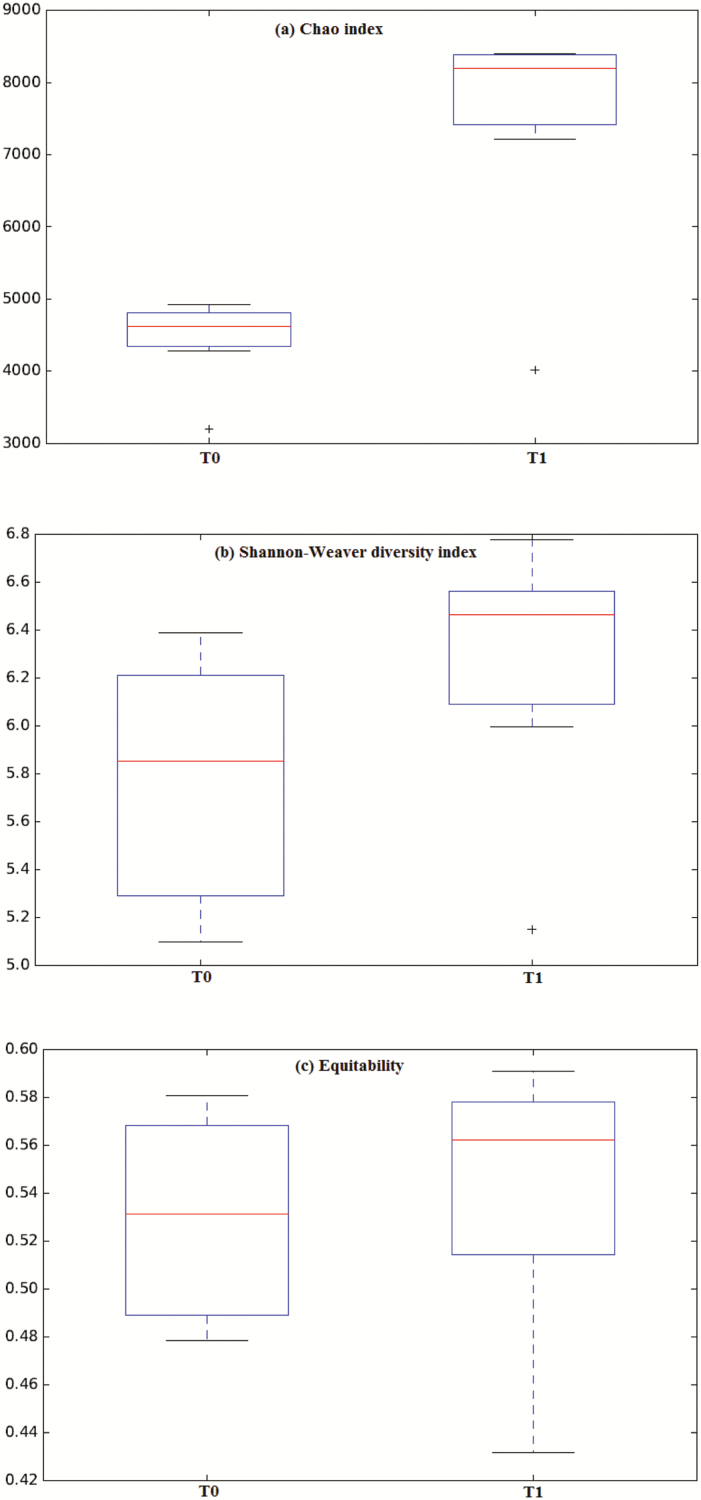

At species level, a total of 215 and 157 OTU for T0 and T1, respectively, were identified. Most abundant species at T0 were Clostridium hiranonis (21.83 ± 0.05%) and Blautia producta (9.81 ± 0.02), and at T1 were unclassified Allobaculum (30.13 ± 0.11%) and C. hiranonis (9.22 ± 0.03). Moreover, estimated total number of species were greater at T1 (Chao index; P = 0.014; Fig. 2a) despite a similar species biodiversity (Shannon–Weaver diversity index, P = 0.186; Fig. 2b) and proportion (equitability, P = 0.778; Fig. 2c) being maintained during the study. Globally, differences on microbiota biodiversity at T0 and T1 were significant (P = 0.01), although the two microbiota communities profile showed a low separation level between them (Anosim’s R value = 0.39).

Fig. 2.

Boxplot representation for Chao index (a), Shannon–Weaver diversity index (b) and equitability (c) of bacterial groups in dog feces samples before (T0) and after (T1) 17-wk BW loss program. Boxes are the interquartile range, line is the median, whiskers are the range, and “+” are extreme values.

Functional Analysis

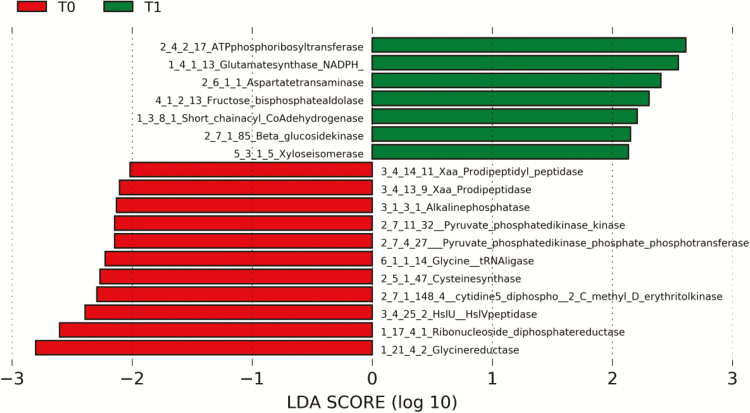

From all the coding genes identified with enzyme classification (EC) enrichments at both time points, we observed 18 EC that most likely could explain differences between T0 and T1 (α = 0.05, LDA score > 2.0; Fig 3). Of these, 11 EC were significantly over expressed at T0 (Fig 3; red) and seven at T1 (Fig 3; green). At T0, we observed an overexpression of four hydrolases (EC category 3), mainly hydrolases that act on peptide bonds (EC 3.4), four transferases (EC category 2), mainly transferring phosphorus-containing groups (EC 2.7), two oxidoreductases (EC category 1), and one ligase (EC category 6). At T1, we observed an overexpression of three transferases, two oxidoreductases, one lyase (EC category 4) and one isomerase (EC category 5).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of coding genes with enzyme classification (EC) enrichments differentially present before (T0, red) and after (T1, green) 17-wk BW loss program dog feces using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (α = 0.05, LDA score > 2.0). Each row represents the expression of a single EC number and name.

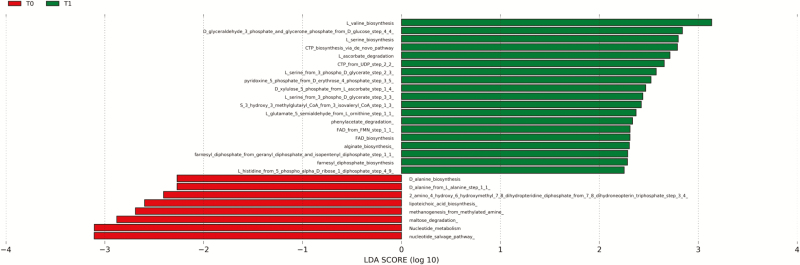

Moreover, from the identified pathways, we detected 27 pathways that most likely explained differences between T0 and T1 (Fig. 4). Of these, eight pathways were significantly over represented at T0, and 19 pathways were over represented at T1 (α = 0.05, LDA score > 2.0; Fig 4). Pathways over represented were mainly related to protein metabolism.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of coding genes regarding pathways differentially present before (T0, red) and after (T1, green) 17-wk BW loss program dog feces using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (α = 0.05, LDA score > 2.0).

DISCUSSION

The results reported should be interpreted carefully and its extrapolation to companion dogs considering the protocol design. We used experimental Beagles housed in the same facilities with controlled conditions of management and feeding which are different to the ones for companion animals, which increases similarity among the enrolled dogs. Moreover, feeding behavior of these dogs are also likely very different from a companion dog.

Body Changes After a BW Loss Program

The reduction of body fat without affecting lean and bone mass could be due to the slow rate of weekly BW loss and the high content of CP in the diet as has been suggested by Diez et al. (2002). We achieved a greater body fat reduction in a few days compared to what was observed by German et al. (2010), even though we had a similar starting body fat proportion, diet composition, and proportion of total BW loss. This could be explained by the fact that we included more homogenous animals while German et al. (2010) enrolled pet dogs from different breeds and sizes, neutered and intact, with a greater average starting BW (32.75 kg BW).

The decrease in serum cholesterol concentration in dogs after following the BW loss program was in agreement with Diez et al. (2004), although they did not detect differences in serum albumin, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, glucose, insulin, lymphocytes, prothrombin time, segmental neutrophils, and mean corpuscular volume. Moreover, Park et al. (2015) have also reported higher cholesterol values in obese dogs than in lean dogs and no differences in triglycerides blood content.

Microbiota Differences

Gut microbiota is the result of the interaction between the host, the diet, the environment, and the microbiota by itself. The BW loss program proposed in this study, as it is done in the veterinary practice, included the modification of the composition of the diet (control vs. obesity diet), the feed regimen (ad libitum vs. restricted intake), and the host health status (obese vs. lean). Consequently, differences in the microbiota communities between T0 and T1 could not be assigned to only one of these factors.

Throughout the gastrointestinal tract, different gut microbiota communities in companion animals have been described (Ritchie et al., 2008; Suchodolski et al., 2008) including feces (Handl et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015); however, as we observed in feces samples from our experiment, Firmicutes was the predominant phylum in all locations (Ritchie et al., 2008; Suchodolski et al., 2008). Most frequent phylums detected also agreed with previous studies in dogs (Suchodolski et al., 2008; Handl et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015), but abundance order slightly varied. Our results showed that Bacteroidetes was the second most abundant phylum in dog feces, which agreed with human gut microbiota profile (The Human Microbiome Project Consortium, 2012), but disagreed with dog gut microbiota previously described (Suchodolski et al., 2008; Handl et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015).

Feeding Regimen, Diet Composition and Weight Loss Effect

Although our experimental design could not separate the effect of weight loss with diet composition and feeding regimen, some studies reported interesting results on diet composition and feeding regimen effect on gastrointestinal microbiota that could partially explain our results. For example, in beagle dogs, Handl et al. (2013) reported that a restriction of feeding intake during 6 mo in lean beagle dogs resulted in a greater relative abundance of Firmicutes and a lower relative abundance of Bacteroidetes than obese dogs fed the same diet ad libitum. On the other hand, Ravussin et al. (2012) reported a greater proportion of Allobaculum in mice with restricted feed intake than in mice with ad libitum feed intake. Moreover, Handl et al. (2013) indicated a significant influence of feeding regime for Clostridia class and Clostridium.

Regarding diet composition, an increase of total dietary fiber (from 1.39% to 4.49% DM) in dog diets has been shown to increase Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, and to decrease Fusobacteria and Actinobacteria proportions (Middelbos et al., 2010). On the other hand, Hildebrandt et al. (2009) reported that high-fat diet increased Firmicutes and Proteobacteria and decreased Bacteroidetes in mice gut microbiota, while Ravussin et al. (2012) indicated an increase in Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes and a reduction in Allobacculum in mice gut microbiota. Although dogs fed with a high-protein low-carbohydrate diet showed a greater abundance of Firmicutes and C. hiranonis than dogs with a low-protein high-carbohydrate diet (Li et al., 2017), we observed a decrease in the genera Clostridium and in C. hiranonis in the dogs that were fed with obesity diet. These differences could be due to the already high-protein content in our control diet, and to several other factors besides the diet when comparing with Li et al. (2017) study.

In both sampling times (T0 and T1), Firmicutes was the main phylum despite modifying diet composition, feeding regime. and health status. Handl et al. (2013) have also reported Firmicutes as the main phylum in obese and lean pet dogs, while Park et al. (2015) indicated that Proteobacteria was the predominant phylum in obese dogs, and Firmicutes in lean dogs. Moreover, the increase of Fusobacteria observed in dog feces at T1 agreed with Handl et al. (2013) and Park et al. (2015), who also reported a greater proportion of that phylum in lean than in obese dogs.

Park et al. (2015) identified a similar OTU number at genus and species level for obese dogs, but they reported a greater OTU number for lean dogs than we did for T1. On the other hand, Handl et al. (2013) reported a similar number of OTU at genus level for lean pet dogs, but a lower OTU number for obese pet dogs than we did for T0. These differences could be related to the different diet composition, and because, in our study, dogs were the same animals at T0 and T1 diminishing the variation related to the animal. Handl et al. (2013) reported a significant influence of the animals in Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes abundance. Most abundant genus at T0 (Clostidium and Blautia) were in agreement with Handl et al. (2013). They also reported Ruminococcus and Enterococcus as two of the most abundant genus, while we obtained a relatively low abundance for those two genus (<0.1%). The greater proportion of Clostridiaceae, and Lactobacillus at T0 than at T1 suggested a colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by a microbiota which could be favorable to obesity. Clostridiaceae are able to degrade complex indigestible carbohydrates producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), and Lactobacillus possess growth-promoting effects, which offer new energy sources to the host (Handl et al., 2013). Moreover, SCFA can activate several pathways that involve cholesterol, lipid, and glucose metabolism (Baothman et al., 2016). The switch of Allobaculum that we observed at T1 agreed with Ravussin et al. (2012) who also reported an enrichment of the gut microbiota with Allobaculum in mice that followed a weight reduction program, indicating that it is a bacterial genera potentially beneficial for the host.

Handl et al. (2013) did not find differences in the Shannon–Weaver diversity index at genus level between obese and lean pet dogs, which agrees with our results comparing T0 and T1. However, differences revealed with the Anosim’s test between microbiota profile at T0 and T1 were in agreement with Park et al. (2015), who indicated differences in the microbiota communities between obese and lean dogs.

Microbiota Functional Analysis

There is a lack of information in the scientific literature about enzyme and pathway overexpression in dog microbiota. Mice fed with a high-fat, high-simple-sugar diet (typical western diet) showed an enrichment of pathways of simple sugars (Turnbaugh et al., 2008). Moreover, obese mice have shown a greater expression of enzymes involved in the breaking down of indigestible polysaccharides (Turnbaugh et al., 2006). The anaerobic fermentation of dietary fiber, protein, and peptides in the colon produces SCFA (Baothman et al., 2016) facilitating the gut absorption and favoring deposit of adipose tissue or microbial growth (Tehrani et al., 2012). Although we observed an overexpression of hydrolases at T0, they were involved in protein degradation and not in carbohydrates as we expected. That could be due to the richer protein content in the dog diet compared to the human diet. Moreover, the increase of protein metabolism pathways at T1 could be related to the maintenance of the lean mass throughout the BW loss program.

In conclusion, our results support our hypothesis that gut microbiota is the interaction of the diet, the host, the environment, and the microbiota by itself. A weight loss program in obese dogs based on a low energy and high-fiber diet fed in restricted quantity successfully modifies their fecal microbiota. At the end of the study, dogs presented a microbiota composition with a greater biodiversity, more presence of Allobaculum, and lower proportion of Clostridium. Moreover, functional microbiota analysis at the end of the study showed a lower expression of hydrolases related to protein metabolism; however, further investigation is needed to elucidate the biological effect.

LITERATURE CITED

- Atlas R., and Bartha R.. 1998. Microbial ecology: fundamentals and applications. Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Baothman O. A., Zamzami M. A., Taher I., Abubaker J., and Abu-Farha M.. 2016. The role of gut microbiota in the development of obesity and diabetes. Lipids Health Dis. 15:108. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0278-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland I. M., Guthrie-Jones A., Taylor R. D., and Hill J.. 2010. Dog obesity: veterinary practices’ and owners’ opinions on cause and management. Prev. Vet. Med. 94:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., Costello E. K., Fierer N., Peña A. G., Goodrich J. K., Gordon J. I., et al. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis T. Z., Hugenholtz P., Larsen N., Rojas M., Brodie E. L., Keller K., Huber T., Dalevi D., Hu P., and Andersen G. L.. 2006. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez M., Michaux C., Jeusette I., Baldwin P., Istasse L., and Biourge V.. 2004. Evolution of blood parameters during weight loss in experimental obese beagle dogs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 88:166–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2003.00474.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez M., Nguyen P., Jeusette I., Devois C., Istasse L., and Biourge V.. 2002. Weight loss in obese dogs: evaluation of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet. J. Nutr. 132 (6 Suppl 2):1685S–1687S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.6.1685S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L., Moreno-Andrade I., Huang C. L., Xia S., and Hermanowicz S. W.. 2009. Effects of short solids retention time on microbial community in a membrane bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 100:3489–3496. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.02.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M. M., Kessler A. M., Kieffer D. A., Knotts T. A., Kim K., Wei A., Ramsey J. J., and Fascetti A. J.. 2017. Effects of obesity, energy restriction and neutering on the faecal microbiota of cats. Br. J. Nutr. 118:513–524. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517002379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German A. J. 2006. The growing problem of obesity in dogs and cats. J. Nutr. 136:1940–1946. doi: 136/7/1940S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German A. J., Holden S. L., Bissot T., Morris P. J., and Biourge V.. 2010. A high protein high fibre diet improves weight loss in obese dogs. Vet. J. 183:294–297. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handl S., German A. J., Holden S. L., Dowd S. E., Steiner J. M., Heilmann R. M., Grant R. W., Swanson K. S., and Suchodolski J. S.. 2013. Faecal microbiota in lean and obese dogs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 84:332–343. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt M. A., Hoffmann C., Sherrill-Mix S. A., Keilbaugh S. A., Hamady M., Chen Y. Y., Knight R., Ahima R. S., Bushman F., and Wu G. D.. 2009. High-fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology 137:1716–24.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. B., Hellmann J. J., Ricketts T. H., and Bohannan B. J.. 2001. Counting the uncountable: statistical approaches to estimating microbial diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4399–4406. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4399-4406.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieler I. N., Mølbak L., Hansen L. L., Hermann-Bank M. L., and Bjornvad C. R.. 2016. Overweight and the feline gut microbiome - a pilot study. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 100:478–484. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme D. P., Kuhlman G., Lawler D. F., Kealy R. D., and Schmidt D. A.. 1994. Obesity management in dogs. Vet. Clin. Nutr. 1:59–65. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ledder R. G., Gilbert P., Huws S. A., Aarons L., Ashley M. P., Hull P. S., and McBain A. J.. 2007. Molecular analysis of the subgingival microbiota in health and disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:516–523. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01419-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Lauber C. L., Czarnecki-Maulden G., Pan Y., and Hannah S. S.. 2017. Effects of the dietary protein and carbohydrate ratio on gut microbiomes in dogs of different body conditions. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 8:e01703–e01716. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01703-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E. M., Armstrong P. J., Kirk C. A., and Klausner J. S.. 2006. Prevalence and risk factors for obesity in adult dogs from private US veterinary practices. Int. J. Appl. Res. Vet. Med. 4:177–186. http://www.jarvm.com/articles/Vol4Iss2/Lund.pdf [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D., Price M. N., Goodrich J., Nawrocki E. P., DeSantis T. Z., Probst A., Andersen G. L., Knight R., and Hugenholtz P.. 2012. An improved greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. Isme J. 6:610–618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelbos I. S., Vester Boler B. M., Qu A., White B. A., Swanson K. S., and Fahey G. C. Jr. 2010. Phylogenetic characterization of fecal microbial communities of dogs fed diets with or without supplemental dietary fiber using 454 pyrosequencing. Plos One 5:e9768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Molina J. A., Peralta-Sánchez J. M., González A., McMurdie P. J., Vázquez-Baeza Y., Xu Z., Ursell L. K., Lauber C., Zhou H., Song S. J., et al. 2013. Advancing our understanding of the human microbiome using QIIME. Methods Enzymol. 531:371–444. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407863-5.00019-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. J., Lee S. E., Kim H. B., Isaacson R. E., Seo K. W., and Song K. H.. 2015. Association of obesity with serum leptin, adiponectin, and serotonin and gut microflora in beagle dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 29:43–50. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravussin Y., Koren O., Spor A., LeDuc C., Gutman R., Stombaugh J., Knight R., Ley R. E., and Leibel R. L.. 2012. Responses of gut microbiota to diet composition and weight loss in lean and obese mice. Obesity 20:738–747. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie L. E., Steiner J. M., and Suchodolski J. S.. 2008. Assessment of microbial diversity along the feline intestinal tract using 16S rRNA gene analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 66:590–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00609.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchodolski J. S., Camacho J., and Steiner J. M.. 2008. Analysis of bacterial diversity in the canine duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon by comparative 16S rRNA gene analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 66:567–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00521.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani A. B., Nezami B. G., Gewirtz A., and Srinivasan S.. 2012. Obesity and its associated disease: a role for microbiota?Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 24:305–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01895.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Human Microbiome Project Consortium 2012. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Bäckhed F., Fulton L., and Gordon J. I.. 2008. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 3:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Hamady M., Yatsunenko T., Cantarel B. L., Duncan A., Ley R. E., Sogin M. L., Jones W. J., Roe B. A., Affourtit J. P., et al. 2009. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Ley R. E., Mahowald M. A., Magrini V., Mardis E. R., and Gordon J. I.. 2006. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Liu D., Liu F., Wu J., Zou J., Xiao X., Zhao F., and Zhu B.. 2013. HTQC: a fast quality control toolkit for Illumina sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 14:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]